You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (January 2023) Click for important translation instructions.

|

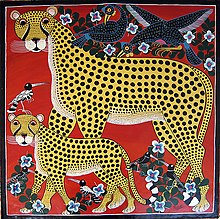

Tingatinga (also spelt Tinga-tinga or Tinga Tinga) is a painting style that originated in East Africa. Tingatinga is one of the most widely represented forms of tourist-oriented paintings in Tanzania, Kenya and neighbouring countries. The genre is named after its founder, Tanzanian painter Edward Tingatinga. Tinga Tinga also insipired kids animation tales, namely Tinga Tinga Tales.

According to Tingatinga, his paintings were mostly based on pictures and characters with Hindu mythological figures and sequences which he had come across as a domestic servant in a practising Hindu family in Dar es salaam.

This was the only employment Tingatinga had after he arrived from Mozambique at the age of 16 until he started painting, which he was taught by his employer.

Even the Sherani, the Devil (and other 'evil spirits') in his paintings, was given a black face after the Indian demon king Ravana.

Several copies of one white bungalow with a peacock and stylised flowers were also copied from Indian calendars. The bungalow was first drawn after the school building of St. Joseph's Convent in Dar es salaam.

Furthermore, Tingatinga did not hide the fact that he was signing all the paintings produced by his relatives and friends in the workshop in the backyard of his house.

Source: "Oriental Influences in Swahili, A Study in Language and Culture Contacts" by ABDULAZIZ Y. LODHI, ACTA UNIVERSITATIS GOTHOBURGENSIS

Tingatinga is traditionally made on masonite, using several layers of bicycle paint, which makes for brilliant and highly saturated colours. Many elements of the style are related to the requirements of the tourist-oriented market; for example, the paintings are usually small so they can be easily transported, and subjects are intended to appeal to Europeans and Americans (e.g. the big five and other wild fauna). In this sense, Tingatinga paintings can be considered a form of "airport painting". The drawings themselves can be described as both naïve and caricatural; humour and sarcasm are often explicit.

History

Tingatinga art originated in Tanzania in 1978. The art was named after Edward Tingatinga who started copying the art in 1968. He employed low-cost materials such as masonite and bicycle paint and attracted the attention of tourists for their colourful, both naïve and surrealistic style. When Tingatinga died in 1972, his style was so popular that it had started a wide movement of imitators and followers, sometimes informally referred to as the "Tingatinga school".

The first generation of artists from the Tingatinga school basically reproduced the works of the school's founder. In the 1990s new trends emerged within the Tingatinga style, in response to the transformations that the Tanzanian society was undergoing after independence. New subjects related to the new urban and multi-ethnic society of Dar es Salaam (e.g. crowded and busy streets and squares) were introduced, together with occasional technical novelties (such as the use of perspective). One of the most well-known second-generation Tingatinga painters is Edward Tingatinga's brother-in-law, Simon Mpata.

Because of his short artistic life, Tingatinga left only a relatively small number of paintings, which are sought-after by collectors. It is known that fakes were produced from all famous Tingatinga paintings like: The lion, Peacock on the Baobab Tree, Antelope, Leopard, Buffalo, or Monkey.

Influences

It is controversial whether Tingatinga's style is completely original or a derivative of traditional forms of East Africa. In his seminal paper Tingatinga and His Followers, Swedish critic Berit Sahlström claimed that Tingatinga was of Mozambican origin and thus suggested that his style might have connections with modern Mozambique. The claim that Tingatinga was of Mozambican descent is nevertheless rejected by most scholars and by the Tingatinga Society. Art trader Yves Goscinny suggested that Edward Tingatinga might have been influenced by Congolese paintings that were sold in Dar es Salaam at his time. The source of this claim could be some articles by Merete Teisen, where she also claims that Tingatinga decorated two house walls for payment before he started painting on masonite boards.

The claim by Merete Teisen about Tingatinga decorating house walls might also be interpreted as a clue to another origin of Tingatinga's paintings, namely the traditional hut wall decorations of Makua and Makonde people. These paintings were first witnessed by Karl Weule in 1906 and described in his book Negerleben in Ostafrika. Also ethnologist Jesper Kirknaes and Japanese painting curator Kenji Shiraishi, as well as modern travellers, have seen and documented these paintings in several locations in southern Tanzania, including Ngapa, a village where many relatives of Tingatinga's father still live today.

Jesper Kirknaes also documented those paintings being done in Dar es Salaam by Makua and Makonde migrants. Shiraishi is one of the scholars who most firmly supported the theory that Tingatinga's art is connected to traditional Makua wall paintings. Among other considerations, Shiraishi observed that it is unlikely that a style emerged and spread so quickly over most of East Africa without any connection to traditional art. He claimed that his studies provided evidence for this claim.

In 2010 Hanne Thorup interviewed Tingatinga student Omari Amonde, who confirmed that Tingatinga used to paint on hut walls as a young boy (around 12 years old).

Further elaborating on the Makua painting hypothesis, Shiraishi also suggested a connection between hut walls, painting and traditional rock paintings, an art form that in Africa has continued past Stone Age to at least the 19th century. Based on this connection, Shiraishi concludes that Tingatinga art might be seen as the "longest artist trend ever".

The Tingatinga Cooperative Society

After Tingatinga's death, his direct six followers: Ajaba Abdallah Mtalia, Adeusi Mandu, January Linda, Casper Tedo, Simon Mpata, and Omari Amonde tried to organise themselves. Relatives of Tingatinga also joined this group, which would be later called the "Tingatinga (or Tinga Tinga) Partnership". Not all of Tingatinga's followers agreed to be in the partnership; some created a new group at Slipway. In 1990, the Tingatinga Partnership constituted itself into a society, renamed to Tingatinga Arts Cooperative Society (TACS).

The Tingatinga Arts Cooperative Society launched its own website in May 2018, www.TingaTingaArt.com

Tingatinga and George Lilanga

Although the internationally acclaimed Tanzanian artist George Lilanga was not a student of the Tingatinga school nor a member of the Tingatinga Society, he's known to have frequented Tingatinga artists, and some influence of Tingatinga is evident in his work, for what concerns painting (an art form that Lilanga approached in 1974). This influence has been recognised by Lilanga himself in an interview with Kenji Shiraishi, specifically in reference to the use of enamel paint and square hardboards. Besides using materials and techniques originally adopted by Tingatinga painters, Lilanga's art resembles Tingatinga also in its use of vibrant colours and its composition style, that shares the same horror vacui of Tingatinga art. It has been suggested that Lilanga (who was originally a sculptor) actually learnt to paint from Tingatinga painters such as Noel Kapanda and later Mchimbi Halfani, who collaborated with him. The collaboration between Lilanga and Kapanda lasted several years.

References

- "Exploring the Tingatinga Art Movement in Tanzania". Archived from the original on 17 July 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- "Tinga Tinga art". Tingatinga.org. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- The tingatinga school of painting. This is an informal term (i.e., those who paint after Tingatinga's example) and not to be confused with the Tingatinga Arts Cooperative Society, which is a specific organisation, although sometimes also referred to as a "school". "The tinga tinga school of painting". Archived from the original on 17 September 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Tingatinga first students Archived 7 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Are Tingatinga fakes a problem today?". Alexdrummerafrica.blog.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "Art in Tanzania 2010"

- K. Weule (1908), Negerleben in Ostafrika, Leipzig.

- Kenji Shiraishi, Commentary to Tingatinga II; article: Tinga TingaContemporary African Art and Mural; Tingatinga: Afurikan poppu-ato no sekai / Kenji Shiraishi and Fumiko Yamamoto. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1990)

- Hanne Thorup and Chitra Sundaram (2010), Tingatinga, Kitsch or Art, p. 22; article: Off the walls to Hard Board and Canvas; What inspired Tingatinga?

- Kenji Shirashi, Lilanga's Cosmos, Africa Hoy, p. 7

- Mwasanga, National Arts Council, Mture Publishers, Tingatinga, p 30

- Abdellahamani Hasani

- "Tingatinga Co-operative Society". Tingatinga.org. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- Lilanga, George (2007). Colors of Africa. p. 136. ISBN 978-88-89298-32-9.

- George Lilanga, Kamphausen

- See K. Shiraishi, Lilanga's Cosmos, Africa Hoy, p. 7. The book reports Lilanga's words as follows: It was entirely my own idea to incorporate this style. Nobody suggests I do it. In the Tingatinga style, I use enamel paint on the hardboard. This board is excellent for achieving vivid colour."

- Enrico Masceloni, Catalogue Raisonne, George Lilanga, p. XII

- Thorup, Tine; Sam, Cuong (2011). Tingatinga Kitch Or Quality Bicycle Enamel on Board & Canvas. p. 68. ISBN 978-87-992635-2-3.

- See also the Lilanga.org Archived 12 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine and Makonde Carvings Archived 14 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine websites

- K. Shiraishi, Tingatinga and Lilanga, The Museum of Art, Kochi, Japan 2004

- Art, Tinga Tinga. "Tinga Tinga Art | Handmade African Art, Decor, Gifts & Paintings". Tinga Tinga Art. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

Further reading

- Tingatinga. 1998. ISBN 978-9976-967-34-0.

- Kilonzo, Kiagho B. (2016). "The Authenticity of Today's Tingatinga Art". Sanaa Journal. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- Thorup, Tine; Sam, Cuong (2011). Tingatinga Kitch Or Quality Bicycle Enamel on Board & Canvas. ISBN 978-87-992635-2-3.