| b | |

|---|---|

| notation | |

| base b and exponent n |

| Arithmetic operations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In mathematics, exponentiation is an operation involving two numbers: the base and the exponent or power. Exponentiation is written as b, where b is the base and n is the power; often said as "b to the power n". When n is a positive integer, exponentiation corresponds to repeated multiplication of the base: that is, b is the product of multiplying n bases: In particular, .

The exponent is usually shown as a superscript to the right of the base as b or in computer code as b^n, and may also be called "b raised to the nth power", "b to the power of n", "the nth power of b", or most briefly "b to the n".

The above definition of immediately implies several properties, in particular the multiplication rule:

That is, when multiplying a base raised to one power times the same base raised to another power, the powers add. Extending this rule to the power zero gives , and dividing both sides by gives . That is, the multiplication rule implies the definition A similar argument implies the definition for negative integer powers: That is, extending the multiplication rule gives . Dividing both sides by gives . This also implies the definition for fractional powers: For example, , meaning , which is the definition of square root: .

The definition of exponentiation can be extended in a natural way (preserving the multiplication rule) to define for any positive real base and any real number exponent . More involved definitions allow complex base and exponent, as well as certain types of matrices as base or exponent.

Exponentiation is used extensively in many fields, including economics, biology, chemistry, physics, and computer science, with applications such as compound interest, population growth, chemical reaction kinetics, wave behavior, and public-key cryptography.

Etymology

The term exponent originates from the Latin exponentem, the present participle of exponere, meaning "to put forth". The term power (Latin: potentia, potestas, dignitas) is a mistranslation of the ancient Greek δύναμις (dúnamis, here: "amplification") used by the Greek mathematician Euclid for the square of a line, following Hippocrates of Chios.

History

Antiquity

The Sand Reckoner

Main article: The Sand ReckonerIn The Sand Reckoner, Archimedes proved the law of exponents, 10 · 10 = 10, necessary to manipulate powers of 10. He then used powers of 10 to estimate the number of grains of sand that can be contained in the universe.

Islamic Golden Age

Māl and kaʿbah ("square" and "cube")

In the 9th century, the Persian mathematician Al-Khwarizmi used the terms مَال (māl, "possessions", "property") for a square—the Muslims, "like most mathematicians of those and earlier times, thought of a squared number as a depiction of an area, especially of land, hence property"—and كَعْبَة (Kaʿbah, "cube") for a cube, which later Islamic mathematicians represented in mathematical notation as the letters mīm (m) and kāf (k), respectively, by the 15th century, as seen in the work of Abu'l-Hasan ibn Ali al-Qalasadi.

15th–18th century

Introducing exponents

Nicolas Chuquet used a form of exponential notation in the 15th century, for example 12 to represent 12x. This was later used by Henricus Grammateus and Michael Stifel in the 16th century. In the late 16th century, Jost Bürgi would use Roman numerals for exponents in a way similar to that of Chuquet, for example iii4 for 4x.

"Exponent"; "square" and "cube"

The word exponent was coined in 1544 by Michael Stifel. In the 16th century, Robert Recorde used the terms square, cube, zenzizenzic (fourth power), sursolid (fifth), zenzicube (sixth), second sursolid (seventh), and zenzizenzizenzic (eighth). Biquadrate has been used to refer to the fourth power as well.

Modern exponential notation

In 1636, James Hume used in essence modern notation, when in L'algèbre de Viète he wrote A for A. Early in the 17th century, the first form of our modern exponential notation was introduced by René Descartes in his text titled La Géométrie; there, the notation is introduced in Book I.

I designate ... aa, or a in multiplying a by itself; and a in multiplying it once more again by a, and thus to infinity.

— René Descartes, La Géométrie

Some mathematicians (such as Descartes) used exponents only for powers greater than two, preferring to represent squares as repeated multiplication. Thus they would write polynomials, for example, as ax + bxx + cx + d.

"Indices"

Samuel Jeake introduced the term indices in 1696. The term involution was used synonymously with the term indices, but had declined in usage and should not be confused with its more common meaning.

Variable exponents, non-integer exponents

In 1748, Leonhard Euler introduced variable exponents, and, implicitly, non-integer exponents by writing:

Consider exponentials or powers in which the exponent itself is a variable. It is clear that quantities of this kind are not algebraic functions, since in those the exponents must be constant.

20th century

As calculation was mechanized, notation was adapted to numerical capacity by conventions in exponential notation. For example Konrad Zuse introduced floating point arithmetic in his 1938 computer Z1. One register contained representation of leading digits, and a second contained representation of the exponent of 10. Earlier Leonardo Torres Quevedo contributed Essays on Automation (1914) which had suggested the floating-point representation of numbers. The more flexible decimal floating-point representation was introduced in 1946 with a Bell Laboratories computer. Eventually educators and engineers adopted scientific notation of numbers, consistent with common reference to order of magnitude in a ratio scale.

Terminology

The expression b = b · b is called "the square of b" or "b squared", because the area of a square with side-length b is b. (It is true that it could also be called "b to the second power", but "the square of b" and "b squared" are more traditional)

Similarly, the expression b = b · b · b is called "the cube of b" or "b cubed", because the volume of a cube with side-length b is b.

When an exponent is a positive integer, that exponent indicates how many copies of the base are multiplied together. For example, 3 = 3 · 3 · 3 · 3 · 3 = 243. The base 3 appears 5 times in the multiplication, because the exponent is 5. Here, 243 is the 5th power of 3, or 3 raised to the 5th power.

The word "raised" is usually omitted, and sometimes "power" as well, so 3 can be simply read "3 to the 5th", or "3 to the 5".

Integer exponents

The exponentiation operation with integer exponents may be defined directly from elementary arithmetic operations.

Positive exponents

The definition of the exponentiation as an iterated multiplication can be formalized by using induction, and this definition can be used as soon as one has an associative multiplication:

The base case is

and the recurrence is

The associativity of multiplication implies that for any positive integers m and n,

and

Zero exponent

As mentioned earlier, a (nonzero) number raised to the 0 power is 1:

This value is also obtained by the empty product convention, which may be used in every algebraic structure with a multiplication that has an identity. This way the formula

also holds for .

The case of 0 is controversial. In contexts where only integer powers are considered, the value 1 is generally assigned to 0 but, otherwise, the choice of whether to assign it a value and what value to assign may depend on context. For more details, see Zero to the power of zero.

Negative exponents

Exponentiation with negative exponents is defined by the following identity, which holds for any integer n and nonzero b:

- .

Raising 0 to a negative exponent is undefined but, in some circumstances, it may be interpreted as infinity ().

This definition of exponentiation with negative exponents is the only one that allows extending the identity to negative exponents (consider the case ).

The same definition applies to invertible elements in a multiplicative monoid, that is, an algebraic structure, with an associative multiplication and a multiplicative identity denoted 1 (for example, the square matrices of a given dimension). In particular, in such a structure, the inverse of an invertible element x is standardly denoted

Identities and properties

"Laws of Indices" redirects here. For the horse, see Laws of Indices (horse).The following identities, often called exponent rules, hold for all integer exponents, provided that the base is non-zero:

Unlike addition and multiplication, exponentiation is not commutative: for example, , but reversing the operands gives the different value . Also unlike addition and multiplication, exponentiation is not associative: for example, (2) = 8 = 64, whereas 2 = 2 = 512. Without parentheses, the conventional order of operations for serial exponentiation in superscript notation is top-down (or right-associative), not bottom-up (or left-associative). That is,

which, in general, is different from

Powers of a sum

The powers of a sum can normally be computed from the powers of the summands by the binomial formula

However, this formula is true only if the summands commute (i.e. that ab = ba), which is implied if they belong to a structure that is commutative. Otherwise, if a and b are, say, square matrices of the same size, this formula cannot be used. It follows that in computer algebra, many algorithms involving integer exponents must be changed when the exponentiation bases do not commute. Some general purpose computer algebra systems use a different notation (sometimes ^^ instead of ^) for exponentiation with non-commuting bases, which is then called non-commutative exponentiation.

Combinatorial interpretation

See also: Exponentiation over setsFor nonnegative integers n and m, the value of n is the number of functions from a set of m elements to a set of n elements (see cardinal exponentiation). Such functions can be represented as m-tuples from an n-element set (or as m-letter words from an n-letter alphabet). Some examples for particular values of m and n are given in the following table:

| n | The n possible m-tuples of elements from the set {1, ..., n} |

|---|---|

| 0 = 0 | none |

| 1 = 1 | (1, 1, 1, 1) |

| 2 = 8 | (1, 1, 1), (1, 1, 2), (1, 2, 1), (1, 2, 2), (2, 1, 1), (2, 1, 2), (2, 2, 1), (2, 2, 2) |

| 3 = 9 | (1, 1), (1, 2), (1, 3), (2, 1), (2, 2), (2, 3), (3, 1), (3, 2), (3, 3) |

| 4 = 4 | (1), (2), (3), (4) |

| 5 = 1 | () |

Particular bases

Powers of ten

See also: Scientific notation Main article: Power of 10In the base ten (decimal) number system, integer powers of 10 are written as the digit 1 followed or preceded by a number of zeroes determined by the sign and magnitude of the exponent. For example, 10 = 1000 and 10 = 0.0001.

Exponentiation with base 10 is used in scientific notation to denote large or small numbers. For instance, 299792458 m/s (the speed of light in vacuum, in metres per second) can be written as 2.99792458×10 m/s and then approximated as 2.998×10 m/s.

SI prefixes based on powers of 10 are also used to describe small or large quantities. For example, the prefix kilo means 10 = 1000, so a kilometre is 1000 m.

Powers of two

Main article: Power of twoThe first negative powers of 2 have special names: is a half; is a quarter.

Powers of 2 appear in set theory, since a set with n members has a power set, the set of all of its subsets, which has 2 members.

Integer powers of 2 are important in computer science. The positive integer powers 2 give the number of possible values for an n-bit integer binary number; for example, a byte may take 2 = 256 different values. The binary number system expresses any number as a sum of powers of 2, and denotes it as a sequence of 0 and 1, separated by a binary point, where 1 indicates a power of 2 that appears in the sum; the exponent is determined by the place of this 1: the nonnegative exponents are the rank of the 1 on the left of the point (starting from 0), and the negative exponents are determined by the rank on the right of the point.

Powers of one

Every power of one equals: 1 = 1.

Powers of zero

For a positive exponent n > 0, the nth power of zero is zero: 0 = 0. For a negative\ exponent, is undefined.

The expression 0 is either defined as , or it is left undefined.

Powers of negative one

Since a negative number times another negative is positive, we have:

Because of this, powers of −1 are useful for expressing alternating sequences. For a similar discussion of powers of the complex number i, see § nth roots of a complex number.

Large exponents

The limit of a sequence of powers of a number greater than one diverges; in other words, the sequence grows without bound:

- b → ∞ as n → ∞ when b > 1

This can be read as "b to the power of n tends to +∞ as n tends to infinity when b is greater than one".

Powers of a number with absolute value less than one tend to zero:

- b → 0 as n → ∞ when |b| < 1

Any power of one is always one:

- b = 1 for all n for b = 1

Powers of a negative number alternate between positive and negative as n alternates between even and odd, and thus do not tend to any limit as n grows.

If the exponentiated number varies while tending to 1 as the exponent tends to infinity, then the limit is not necessarily one of those above. A particularly important case is

- (1 + 1/n) → e as n → ∞

See § Exponential function below.

Other limits, in particular those of expressions that take on an indeterminate form, are described in § Limits of powers below.

Power functions

Main article: Power law

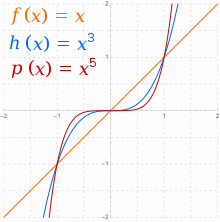

Real functions of the form , where , are sometimes called power functions. When is an integer and , two primary families exist: for even, and for odd. In general for , when is even will tend towards positive infinity with increasing , and also towards positive infinity with decreasing . All graphs from the family of even power functions have the general shape of , flattening more in the middle as increases. Functions with this kind of symmetry () are called even functions.

When is odd, 's asymptotic behavior reverses from positive to negative . For , will also tend towards positive infinity with increasing , but towards negative infinity with decreasing . All graphs from the family of odd power functions have the general shape of , flattening more in the middle as increases and losing all flatness there in the straight line for . Functions with this kind of symmetry () are called odd functions.

For , the opposite asymptotic behavior is true in each case.

Table of powers of decimal digits

| n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 512 | 1024 |

| 3 | 9 | 27 | 81 | 243 | 729 | 2187 | 6561 | 19683 | 59049 |

| 4 | 16 | 64 | 256 | 1024 | 4096 | 16384 | 65536 | 262144 | 1048576 |

| 5 | 25 | 125 | 625 | 3125 | 15625 | 78125 | 390625 | 1953125 | 9765625 |

| 6 | 36 | 216 | 1296 | 7776 | 46656 | 279936 | 1679616 | 10077696 | 60466176 |

| 7 | 49 | 343 | 2401 | 16807 | 117649 | 823543 | 5764801 | 40353607 | 282475249 |

| 8 | 64 | 512 | 4096 | 32768 | 262144 | 2097152 | 16777216 | 134217728 | 1073741824 |

| 9 | 81 | 729 | 6561 | 59049 | 531441 | 4782969 | 43046721 | 387420489 | 3486784401 |

| 10 | 100 | 1000 | 10000 | 100000 | 1000000 | 10000000 | 100000000 | 1000000000 | 10000000000 |

Rational exponents

If x is a nonnegative real number, and n is a positive integer, or denotes the unique nonnegative real nth root of x, that is, the unique nonnegative real number y such that

If x is a positive real number, and is a rational number, with p and q > 0 integers, then is defined as

The equality on the right may be derived by setting and writing

If r is a positive rational number, 0 = 0, by definition.

All these definitions are required for extending the identity to rational exponents.

On the other hand, there are problems with the extension of these definitions to bases that are not positive real numbers. For example, a negative real number has a real nth root, which is negative, if n is odd, and no real root if n is even. In the latter case, whichever complex nth root one chooses for the identity cannot be satisfied. For example,

See § Real exponents and § Non-integer powers of complex numbers for details on the way these problems may be handled.

Real exponents

For positive real numbers, exponentiation to real powers can be defined in two equivalent ways, either by extending the rational powers to reals by continuity (§ Limits of rational exponents, below), or in terms of the logarithm of the base and the exponential function (§ Powers via logarithms, below). The result is always a positive real number, and the identities and properties shown above for integer exponents remain true with these definitions for real exponents. The second definition is more commonly used, since it generalizes straightforwardly to complex exponents.

On the other hand, exponentiation to a real power of a negative real number is much more difficult to define consistently, as it may be non-real and have several values. One may choose one of these values, called the principal value, but there is no choice of the principal value for which the identity

is true; see § Failure of power and logarithm identities. Therefore, exponentiation with a basis that is not a positive real number is generally viewed as a multivalued function.

Limits of rational exponents

Since any irrational number can be expressed as the limit of a sequence of rational numbers, exponentiation of a positive real number b with an arbitrary real exponent x can be defined by continuity with the rule

where the limit is taken over rational values of r only. This limit exists for every positive b and every real x.

For example, if x = π, the non-terminating decimal representation π = 3.14159... and the monotonicity of the rational powers can be used to obtain intervals bounded by rational powers that are as small as desired, and must contain

So, the upper bounds and the lower bounds of the intervals form two sequences that have the same limit, denoted

This defines for every positive b and real x as a continuous function of b and x. See also Well-defined expression.

Exponential function

Main article: Exponential functionThe exponential function may be defined as where is Euler's number, but to avoid circular reasoning, this definition cannot be used here. Rather, we give an independent definition of the exponential function and of , relying only on positive integer powers (repeated multiplication). Then we sketch the proof that this agrees with the previous definition:

There are many equivalent ways to define the exponential function, one of them being

One has and the exponential identity (or multiplication rule) holds as well, since

and the second-order term does not affect the limit, yielding .

Euler's number can be defined as . It follows from the preceding equations that when x is an integer (this results from the repeated-multiplication definition of the exponentiation). If x is real, results from the definitions given in preceding sections, by using the exponential identity if x is rational, and the continuity of the exponential function otherwise.

The limit that defines the exponential function converges for every complex value of x, and therefore it can be used to extend the definition of , and thus from the real numbers to any complex argument z. This extended exponential function still satisfies the exponential identity, and is commonly used for defining exponentiation for complex base and exponent.

Powers via logarithms

The definition of e as the exponential function allows defining b for every positive real numbers b, in terms of exponential and logarithm function. Specifically, the fact that the natural logarithm ln(x) is the inverse of the exponential function e means that one has

for every b > 0. For preserving the identity one must have

So, can be used as an alternative definition of b for any positive real b. This agrees with the definition given above using rational exponents and continuity, with the advantage to extend straightforwardly to any complex exponent.

Complex exponents with a positive real base

If b is a positive real number, exponentiation with base b and complex exponent z is defined by means of the exponential function with complex argument (see the end of § Exponential function, above) as

where denotes the natural logarithm of b.

This satisfies the identity

In general, is not defined, since b is not a real number. If a meaning is given to the exponentiation of a complex number (see § Non-integer powers of complex numbers, below), one has, in general,

unless z is real or t is an integer.

allows expressing the polar form of in terms of the real and imaginary parts of z, namely

where the absolute value of the trigonometric factor is one. This results from

Non-integer powers of complex numbers

In the preceding sections, exponentiation with non-integer exponents has been defined for positive real bases only. For other bases, difficulties appear already with the apparently simple case of nth roots, that is, of exponents where n is a positive integer. Although the general theory of exponentiation with non-integer exponents applies to nth roots, this case deserves to be considered first, since it does not need to use complex logarithms, and is therefore easier to understand.

nth roots of a complex number

Every nonzero complex number z may be written in polar form as

where is the absolute value of z, and is its argument. The argument is defined up to an integer multiple of 2π; this means that, if is the argument of a complex number, then is also an argument of the same complex number for every integer .

The polar form of the product of two complex numbers is obtained by multiplying the absolute values and adding the arguments. It follows that the polar form of an nth root of a complex number can be obtained by taking the nth root of the absolute value and dividing its argument by n:

If is added to , the complex number is not changed, but this adds to the argument of the nth root, and provides a new nth root. This can be done n times, and provides the n nth roots of the complex number.

It is usual to choose one of the n nth root as the principal root. The common choice is to choose the nth root for which that is, the nth root that has the largest real part, and, if there are two, the one with positive imaginary part. This makes the principal nth root a continuous function in the whole complex plane, except for negative real values of the radicand. This function equals the usual nth root for positive real radicands. For negative real radicands, and odd exponents, the principal nth root is not real, although the usual nth root is real. Analytic continuation shows that the principal nth root is the unique complex differentiable function that extends the usual nth root to the complex plane without the nonpositive real numbers.

If the complex number is moved around zero by increasing its argument, after an increment of the complex number comes back to its initial position, and its nth roots are permuted circularly (they are multiplied by ). This shows that it is not possible to define a nth root function that is continuous in the whole complex plane.

Roots of unity

Main article: Root of unity

The nth roots of unity are the n complex numbers such that w = 1, where n is a positive integer. They arise in various areas of mathematics, such as in discrete Fourier transform or algebraic solutions of algebraic equations (Lagrange resolvent).

The n nth roots of unity are the n first powers of , that is The nth roots of unity that have this generating property are called primitive nth roots of unity; they have the form with k coprime with n. The unique primitive square root of unity is the primitive fourth roots of unity are and

The nth roots of unity allow expressing all nth roots of a complex number z as the n products of a given nth roots of z with a nth root of unity.

Geometrically, the nth roots of unity lie on the unit circle of the complex plane at the vertices of a regular n-gon with one vertex on the real number 1.

As the number is the primitive nth root of unity with the smallest positive argument, it is called the principal primitive nth root of unity, sometimes shortened as principal nth root of unity, although this terminology can be confused with the principal value of , which is 1.

Complex exponentiation

Defining exponentiation with complex bases leads to difficulties that are similar to those described in the preceding section, except that there are, in general, infinitely many possible values for . So, either a principal value is defined, which is not continuous for the values of z that are real and nonpositive, or is defined as a multivalued function.

In all cases, the complex logarithm is used to define complex exponentiation as

where is the variant of the complex logarithm that is used, which is a function or a multivalued function such that

for every z in its domain of definition.

Principal value

The principal value of the complex logarithm is the unique continuous function, commonly denoted such that, for every nonzero complex number z,

and the argument of z satisfies

The principal value of the complex logarithm is not defined for it is discontinuous at negative real values of z, and it is holomorphic (that is, complex differentiable) elsewhere. If z is real and positive, the principal value of the complex logarithm is the natural logarithm:

The principal value of is defined as where is the principal value of the logarithm.

The function is holomorphic except in the neighbourhood of the points where z is real and nonpositive.

If z is real and positive, the principal value of equals its usual value defined above. If where n is an integer, this principal value is the same as the one defined above.

Multivalued function

In some contexts, there is a problem with the discontinuity of the principal values of and at the negative real values of z. In this case, it is useful to consider these functions as multivalued functions.

If denotes one of the values of the multivalued logarithm (typically its principal value), the other values are where k is any integer. Similarly, if is one value of the exponentiation, then the other values are given by

where k is any integer.

Different values of k give different values of unless w is a rational number, that is, there is an integer d such that dw is an integer. This results from the periodicity of the exponential function, more specifically, that if and only if is an integer multiple of

If is a rational number with m and n coprime integers with then has exactly n values. In the case these values are the same as those described in § nth roots of a complex number. If w is an integer, there is only one value that agrees with that of § Integer exponents.

The multivalued exponentiation is holomorphic for in the sense that its graph consists of several sheets that define each a holomorphic function in the neighborhood of every point. If z varies continuously along a circle around 0, then, after a turn, the value of has changed of sheet.

Computation

The canonical form of can be computed from the canonical form of z and w. Although this can be described by a single formula, it is clearer to split the computation in several steps.

- Polar form of z. If is the canonical form of z (a and b being real), then its polar form is with and , where is the two-argument arctangent function.

- Logarithm of z. The principal value of this logarithm is where denotes the natural logarithm. The other values of the logarithm are obtained by adding for any integer k.

- Canonical form of If with c and d real, the values of are the principal value corresponding to

- Final result. Using the identities and one gets with for the principal value.

Examples

-

The polar form of i is and the values of are thus It follows that So, all values of are real, the principal one being

Similarly, the polar form of −2 is So, the above described method gives the values In this case, all the values have the same argument and different absolute values.

In both examples, all values of have the same argument. More generally, this is true if and only if the real part of w is an integer.

Failure of power and logarithm identities

Some identities for powers and logarithms for positive real numbers will fail for complex numbers, no matter how complex powers and complex logarithms are defined as single-valued functions. For example:

- The identity log(b) = x ⋅ log b holds whenever b is a positive real number and x is a real number. But for the principal branch of the complex logarithm one has

Regardless of which branch of the logarithm is used, a similar failure of the identity will exist. The best that can be said (if only using this result) is that:

This identity does not hold even when considering log as a multivalued function. The possible values of log(w) contain those of z ⋅ log w as a proper subset. Using Log(w) for the principal value of log(w) and m, n as any integers the possible values of both sides are:

- The identities (bc) = bc and (b/c) = b/c are valid when b and c are positive real numbers and x is a real number. But, for the principal values, one has and On the other hand, when x is an integer, the identities are valid for all nonzero complex numbers. If exponentiation is considered as a multivalued function then the possible values of (−1 ⋅ −1) are {1, −1}. The identity holds, but saying {1} = {(−1 ⋅ −1)} is incorrect.

- The identity (e) = e holds for real numbers x and y, but assuming its truth for complex numbers leads to the following paradox, discovered in 1827 by Clausen:

For any integer n, we have:

- (taking the -th power of both sides)

- (using and expanding the exponent)

- (using )

- (dividing by e)

Irrationality and transcendence

Main article: Gelfond–Schneider theoremIf b is a positive real algebraic number, and x is a rational number, then b is an algebraic number. This results from the theory of algebraic extensions. This remains true if b is any algebraic number, in which case, all values of b (as a multivalued function) are algebraic. If x is irrational (that is, not rational), and both b and x are algebraic, Gelfond–Schneider theorem asserts that all values of b are transcendental (that is, not algebraic), except if b equals 0 or 1.

In other words, if x is irrational and then at least one of b, x and b is transcendental.

Integer powers in algebra

The definition of exponentiation with positive integer exponents as repeated multiplication may apply to any associative operation denoted as a multiplication. The definition of x requires further the existence of a multiplicative identity.

An algebraic structure consisting of a set together with an associative operation denoted multiplicatively, and a multiplicative identity denoted by 1 is a monoid. In such a monoid, exponentiation of an element x is defined inductively by

- for every nonnegative integer n.

If n is a negative integer, is defined only if x has a multiplicative inverse. In this case, the inverse of x is denoted x, and x is defined as

Exponentiation with integer exponents obeys the following laws, for x and y in the algebraic structure, and m and n integers:

These definitions are widely used in many areas of mathematics, notably for groups, rings, fields, square matrices (which form a ring). They apply also to functions from a set to itself, which form a monoid under function composition. This includes, as specific instances, geometric transformations, and endomorphisms of any mathematical structure.

When there are several operations that may be repeated, it is common to indicate the repeated operation by placing its symbol in the superscript, before the exponent. For example, if f is a real function whose valued can be multiplied, denotes the exponentiation with respect of multiplication, and may denote exponentiation with respect of function composition. That is,

and

Commonly, is denoted while is denoted

In a group

A multiplicative group is a set with as associative operation denoted as multiplication, that has an identity element, and such that every element has an inverse.

So, if G is a group, is defined for every and every integer n.

The set of all powers of an element of a group form a subgroup. A group (or subgroup) that consists of all powers of a specific element x is the cyclic group generated by x. If all the powers of x are distinct, the group is isomorphic to the additive group of the integers. Otherwise, the cyclic group is finite (it has a finite number of elements), and its number of elements is the order of x. If the order of x is n, then and the cyclic group generated by x consists of the n first powers of x (starting indifferently from the exponent 0 or 1).

Order of elements play a fundamental role in group theory. For example, the order of an element in a finite group is always a divisor of the number of elements of the group (the order of the group). The possible orders of group elements are important in the study of the structure of a group (see Sylow theorems), and in the classification of finite simple groups.

Superscript notation is also used for conjugation; that is, g = hgh, where g and h are elements of a group. This notation cannot be confused with exponentiation, since the superscript is not an integer. The motivation of this notation is that conjugation obeys some of the laws of exponentiation, namely and

In a ring

In a ring, it may occur that some nonzero elements satisfy for some integer n. Such an element is said to be nilpotent. In a commutative ring, the nilpotent elements form an ideal, called the nilradical of the ring.

If the nilradical is reduced to the zero ideal (that is, if implies for every positive integer n), the commutative ring is said to be reduced. Reduced rings are important in algebraic geometry, since the coordinate ring of an affine algebraic set is always a reduced ring.

More generally, given an ideal I in a commutative ring R, the set of the elements of R that have a power in I is an ideal, called the radical of I. The nilradical is the radical of the zero ideal. A radical ideal is an ideal that equals its own radical. In a polynomial ring over a field k, an ideal is radical if and only if it is the set of all polynomials that are zero on an affine algebraic set (this is a consequence of Hilbert's Nullstellensatz).

Matrices and linear operators

If A is a square matrix, then the product of A with itself n times is called the matrix power. Also is defined to be the identity matrix, and if A is invertible, then .

Matrix powers appear often in the context of discrete dynamical systems, where the matrix A expresses a transition from a state vector x of some system to the next state Ax of the system. This is the standard interpretation of a Markov chain, for example. Then is the state of the system after two time steps, and so forth: is the state of the system after n time steps. The matrix power is the transition matrix between the state now and the state at a time n steps in the future. So computing matrix powers is equivalent to solving the evolution of the dynamical system. In many cases, matrix powers can be expediently computed by using eigenvalues and eigenvectors.

Apart from matrices, more general linear operators can also be exponentiated. An example is the derivative operator of calculus, , which is a linear operator acting on functions to give a new function . The nth power of the differentiation operator is the nth derivative:

These examples are for discrete exponents of linear operators, but in many circumstances it is also desirable to define powers of such operators with continuous exponents. This is the starting point of the mathematical theory of semigroups. Just as computing matrix powers with discrete exponents solves discrete dynamical systems, so does computing matrix powers with continuous exponents solve systems with continuous dynamics. Examples include approaches to solving the heat equation, Schrödinger equation, wave equation, and other partial differential equations including a time evolution. The special case of exponentiating the derivative operator to a non-integer power is called the fractional derivative which, together with the fractional integral, is one of the basic operations of the fractional calculus.

Finite fields

Main article: Finite fieldA field is an algebraic structure in which multiplication, addition, subtraction, and division are defined and satisfy the properties that multiplication is associative and every nonzero element has a multiplicative inverse. This implies that exponentiation with integer exponents is well-defined, except for nonpositive powers of 0. Common examples are the field of complex numbers, the real numbers and the rational numbers, considered earlier in this article, which are all infinite.

A finite field is a field with a finite number of elements. This number of elements is either a prime number or a prime power; that is, it has the form where p is a prime number, and k is a positive integer. For every such q, there are fields with q elements. The fields with q elements are all isomorphic, which allows, in general, working as if there were only one field with q elements, denoted

One has

for every

A primitive element in is an element g such that the set of the q − 1 first powers of g (that is, ) equals the set of the nonzero elements of There are primitive elements in where is Euler's totient function.

In the freshman's dream identity

is true for the exponent p. As in It follows that the map

is linear over and is a field automorphism, called the Frobenius automorphism. If the field has k automorphisms, which are the k first powers (under composition) of F. In other words, the Galois group of is cyclic of order k, generated by the Frobenius automorphism.

The Diffie–Hellman key exchange is an application of exponentiation in finite fields that is widely used for secure communications. It uses the fact that exponentiation is computationally inexpensive, whereas the inverse operation, the discrete logarithm, is computationally expensive. More precisely, if g is a primitive element in then can be efficiently computed with exponentiation by squaring for any e, even if q is large, while there is no known computationally practical algorithm that allows retrieving e from if q is sufficiently large.

Powers of sets

The Cartesian product of two sets S and T is the set of the ordered pairs such that and This operation is not properly commutative nor associative, but has these properties up to canonical isomorphisms, that allow identifying, for example, and

This allows defining the nth power of a set S as the set of all n-tuples of elements of S.

When S is endowed with some structure, it is frequent that is naturally endowed with a similar structure. In this case, the term "direct product" is generally used instead of "Cartesian product", and exponentiation denotes product structure. For example (where denotes the real numbers) denotes the Cartesian product of n copies of as well as their direct product as vector space, topological spaces, rings, etc.

Sets as exponents

See also: Function (mathematics) § Set exponentiationA n-tuple of elements of S can be considered as a function from This generalizes to the following notation.

Given two sets S and T, the set of all functions from T to S is denoted . This exponential notation is justified by the following canonical isomorphisms (for the first one, see Currying):

where denotes the Cartesian product, and the disjoint union.

One can use sets as exponents for other operations on sets, typically for direct sums of abelian groups, vector spaces, or modules. For distinguishing direct sums from direct products, the exponent of a direct sum is placed between parentheses. For example, denotes the vector space of the infinite sequences of real numbers, and the vector space of those sequences that have a finite number of nonzero elements. The latter has a basis consisting of the sequences with exactly one nonzero element that equals 1, while the Hamel bases of the former cannot be explicitly described (because their existence involves Zorn's lemma).

In this context, 2 can represents the set So, denotes the power set of S, that is the set of the functions from S to which can be identified with the set of the subsets of S, by mapping each function to the inverse image of 1.

This fits in with the exponentiation of cardinal numbers, in the sense that |S| = |S|, where |X| is the cardinality of X.

In category theory

Main article: Cartesian closed categoryIn the category of sets, the morphisms between sets X and Y are the functions from X to Y. It results that the set of the functions from X to Y that is denoted in the preceding section can also be denoted The isomorphism can be rewritten

This means the functor "exponentiation to the power T " is a right adjoint to the functor "direct product with T ".

This generalizes to the definition of exponentiation in a category in which finite direct products exist: in such a category, the functor is, if it exists, a right adjoint to the functor A category is called a Cartesian closed category, if direct products exist, and the functor has a right adjoint for every T.

Repeated exponentiation

Main articles: Tetration and HyperoperationJust as exponentiation of natural numbers is motivated by repeated multiplication, it is possible to define an operation based on repeated exponentiation; this operation is sometimes called hyper-4 or tetration. Iterating tetration leads to another operation, and so on, a concept named hyperoperation. This sequence of operations is expressed by the Ackermann function and Knuth's up-arrow notation. Just as exponentiation grows faster than multiplication, which is faster-growing than addition, tetration is faster-growing than exponentiation. Evaluated at (3, 3), the functions addition, multiplication, exponentiation, and tetration yield 6, 9, 27, and 7625597484987 (=3 = 3 = 3) respectively.

Limits of powers

Zero to the power of zero gives a number of examples of limits that are of the indeterminate form 0. The limits in these examples exist, but have different values, showing that the two-variable function x has no limit at the point (0, 0). One may consider at what points this function does have a limit.

More precisely, consider the function defined on . Then D can be viewed as a subset of R (that is, the set of all pairs (x, y) with x, y belonging to the extended real number line R = , endowed with the product topology), which will contain the points at which the function f has a limit.

In fact, f has a limit at all accumulation points of D, except for (0, 0), (+∞, 0), (1, +∞) and (1, −∞). Accordingly, this allows one to define the powers x by continuity whenever 0 ≤ x ≤ +∞, −∞ ≤ y ≤ +∞, except for 0, (+∞), 1 and 1, which remain indeterminate forms.

Under this definition by continuity, we obtain:

- x = +∞ and x = 0, when 1 < x ≤ +∞.

- x = 0 and x = +∞, when 0 ≤ x < 1.

- 0 = 0 and (+∞) = +∞, when 0 < y ≤ +∞.

- 0 = +∞ and (+∞) = 0, when −∞ ≤ y < 0.

These powers are obtained by taking limits of x for positive values of x. This method does not permit a definition of x when x < 0, since pairs (x, y) with x < 0 are not accumulation points of D.

On the other hand, when n is an integer, the power x is already meaningful for all values of x, including negative ones. This may make the definition 0 = +∞ obtained above for negative n problematic when n is odd, since in this case x → +∞ as x tends to 0 through positive values, but not negative ones.

Efficient computation with integer exponents

Computing b using iterated multiplication requires n − 1 multiplication operations, but it can be computed more efficiently than that, as illustrated by the following example. To compute 2, apply Horner's rule to the exponent 100 written in binary:

- .

Then compute the following terms in order, reading Horner's rule from right to left.

| 2 = 4 |

| 2 (2) = 2 = 8 |

| (2) = 2 = 64 |

| (2) = 2 = 4096 |

| (2) = 2 = 16777216 |

| 2 (2) = 2 = 33554432 |

| (2) = 2 = 1125899906842624 |

| (2) = 2 = 1267650600228229401496703205376 |

This series of steps only requires 8 multiplications instead of 99.

In general, the number of multiplication operations required to compute b can be reduced to by using exponentiation by squaring, where denotes the number of 1s in the binary representation of n. For some exponents (100 is not among them), the number of multiplications can be further reduced by computing and using the minimal addition-chain exponentiation. Finding the minimal sequence of multiplications (the minimal-length addition chain for the exponent) for b is a difficult problem, for which no efficient algorithms are currently known (see Subset sum problem), but many reasonably efficient heuristic algorithms are available. However, in practical computations, exponentiation by squaring is efficient enough, and much more easy to implement.

Iterated functions

See also: Iterated functionFunction composition is a binary operation that is defined on functions such that the codomain of the function written on the right is included in the domain of the function written on the left. It is denoted and defined as

for every x in the domain of f.

If the domain of a function f equals its codomain, one may compose the function with itself an arbitrary number of time, and this defines the nth power of the function under composition, commonly called the nth iterate of the function. Thus denotes generally the nth iterate of f; for example, means

When a multiplication is defined on the codomain of the function, this defines a multiplication on functions, the pointwise multiplication, which induces another exponentiation. When using functional notation, the two kinds of exponentiation are generally distinguished by placing the exponent of the functional iteration before the parentheses enclosing the arguments of the function, and placing the exponent of pointwise multiplication after the parentheses. Thus and When functional notation is not used, disambiguation is often done by placing the composition symbol before the exponent; for example and For historical reasons, the exponent of a repeated multiplication is placed before the argument for some specific functions, typically the trigonometric functions. So, and both mean and not which, in any case, is rarely considered. Historically, several variants of these notations were used by different authors.

In this context, the exponent denotes always the inverse function, if it exists. So For the multiplicative inverse fractions are generally used as in

In programming languages

Programming languages generally express exponentiation either as an infix operator or as a function application, as they do not support superscripts. The most common operator symbol for exponentiation is the caret (^). The original version of ASCII included an uparrow symbol (↑), intended for exponentiation, but this was replaced by the caret in 1967, so the caret became usual in programming languages.

The notations include:

x ^ y: AWK, BASIC, J, MATLAB, Wolfram Language (Mathematica), R, Microsoft Excel, Analytica, TeX (and its derivatives), TI-BASIC, bc (for integer exponents), Haskell (for nonnegative integer exponents), Lua, and most computer algebra systems.x ** y. The Fortran character set did not include lowercase characters or punctuation symbols other than+-*/()&=.,'and so used**for exponentiation (the initial version useda xx binstead.). Many other languages followed suit: Ada, Z shell, KornShell, Bash, COBOL, CoffeeScript, Fortran, FoxPro, Gnuplot, Groovy, JavaScript, OCaml, ooRexx, F#, Perl, PHP, PL/I, Python, Rexx, Ruby, SAS, Seed7, Tcl, ABAP, Mercury, Haskell (for floating-point exponents), Turing, and VHDL.x ↑ y: Algol Reference language, Commodore BASIC, TRS-80 Level II/III BASIC.x ^^ y: Haskell (for fractional base, integer exponents), D.x⋆y: APL.

In most programming languages with an infix exponentiation operator, it is right-associative, that is, a^b^c is interpreted as a^(b^c). This is because (a^b)^c is equal to a^(b*c) and thus not as useful. In some languages, it is left-associative, notably in Algol, MATLAB, and the Microsoft Excel formula language.

Other programming languages use functional notation:

(expt x y): Common Lisp.pown x y: F# (for integer base, integer exponent).

Still others only provide exponentiation as part of standard libraries:

pow(x, y): C, C++ (inmathlibrary).Math.Pow(x, y): C#.math:pow(X, Y): Erlang.Math.pow(x, y): Java.::Pow(x, y): PowerShell.

In some statically typed languages that prioritize type safety such as Rust, exponentiation is performed via a multitude of methods:

x.pow(y)forxandyas integersx.powf(y)forxandyas floating point numbersx.powi(y)forxas a float andyas an integer

See also

- Double exponential function

- Exponential decay

- Exponential field

- Exponential growth

- Hyperoperation

- Tetration

- Pentation

- List of exponential topics

- Modular exponentiation

- Scientific notation

- Unicode subscripts and superscripts

- x = y

- Zero to the power of zero

Notes

- There are three common notations for multiplication: is most commonly used for explicit numbers and at a very elementary level; is most common when variables are used; is used for emphasizing that one talks of multiplication or when omitting the multiplication sign would be confusing.

- More generally, power associativity is sufficient for the definition.

References

- ^ Nykamp, Duane. "Basic rules for exponentiation". Math Insight. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Power". MathWorld. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- "Exponent | Etymology of exponent by etymonline".

- ^ Rotman, Joseph J. (2015). Advanced Modern Algebra, Part 1. Graduate Studies in Mathematics. Vol. 165 (3rd ed.). Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. p. 130, fn. 4. ISBN 978-1-4704-1554-9.

- Szabó, Árpád (1978). The Beginnings of Greek Mathematics. Synthese Historical Library. Vol. 17. Translated by A.M. Ungar. Dordrecht: D. Reidel. p. 37. ISBN 90-277-0819-3.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. "Etymology of some common mathematical terms". MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive. University of St Andrews.

- Ball, W. W. Rouse (1915). A Short Account of the History of Mathematics (6th ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 38.

- Archimedes. (2009). THE SAND-RECKONER. In T. Heath (Ed.), The Works of Archimedes: Edited in Modern Notation with Introductory Chapters (Cambridge Library Collection - Mathematics, pp. 229-232). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511695124.017.

- ^ Quinion, Michael. "Zenzizenzizenzic". World Wide Words. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. "Abu'l Hasan ibn Ali al Qalasadi". MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive. University of St Andrews.

- Cajori, Florian (1928). A History of Mathematical Notations. Vol. 1. The Open Court Company. p. 102.

- Cajori, Florian (1928). A History of Mathematical Notations. Vol. 1. London: Open Court Publishing Company. p. 344.

- "Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (E)". 2017-06-23.

- Stifel, Michael (1544). Arithmetica integra. Nuremberg: Johannes Petreius. p. 235v.

- Cajori, Florian (1928). A History of Mathematical Notations. Vol. 1. The Open Court Company. p. 204.

- Descartes, René (1637). "La Géométrie". Discourse de la méthode [...]. Leiden: Jan Maire. p. 299.

Et aa, ou a, pour multiplier a par soy mesme; Et a, pour le multiplier encore une fois par a, & ainsi a l'infini

(And aa, or a, in order to multiply a by itself; and a, in order to multiply it once more by a, and thus to infinity). - The most recent usage in this sense cited by the OED is from 1806 ("involution". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)).

- Euler, Leonhard (1748). Introductio in analysin infinitorum (in Latin). Vol. I. Lausanne: Marc-Michel Bousquet. pp. 69, 98–99.

Primum ergo considerandæ sunt quantitates exponentiales, seu Potestates, quarum Exponens ipse est quantitas variabilis. Perspicuum enim est hujusmodi quantitates ad Functiones algebraicas referri non posse, cum in his Exponentes non nisi constantes locum habeant.

- Janet Shiver & Terri Wiilard "Scientific notation: working with orders of magnitude from Visionlearning

- Hodge, Jonathan K.; Schlicker, Steven; Sundstorm, Ted (2014). Abstract Algebra: an inquiry based approach. CRC Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-4665-6706-1.

- Achatz, Thomas (2005). Technical Shop Mathematics (3rd ed.). Industrial Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8311-3086-2.

- Knobloch, Eberhard (1994). "The infinite in Leibniz's mathematics – The historiographical method of comprehension in context". In Kostas Gavroglu; Jean Christianidis; Efthymios Nicolaidis (eds.). Trends in the Historiography of Science. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science. Vol. 151. Springer Netherlands. p. 276. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-3596-4_20. ISBN 9789401735964.

A positive power of zero is infinitely small, a negative power of zero is infinite.

- Bronstein, Ilja Nikolaevič; Semendjajew, Konstantin Adolfovič (1987) . "2.4.1.1. Definition arithmetischer Ausdrücke" [Definition of arithmetic expressions]. Written at Leipzig, Germany. In Grosche, Günter; Ziegler, Viktor; Ziegler, Dorothea (eds.). Taschenbuch der Mathematik [Pocketbook of mathematics] (in German). Vol. 1. Translated by Ziegler, Viktor. Weiß, Jürgen (23 ed.). Thun, Switzerland / Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Verlag Harri Deutsch (and B. G. Teubner Verlagsgesellschaft, Leipzig). pp. 115–120, 802. ISBN 3-87144-492-8.

- Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel W.; Boisvert, Ronald F.; Clark, Charles W., eds. (2010). NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), U.S. Department of Commerce, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19225-5. MR 2723248.

- Zeidler, Eberhard ; Schwarz, Hans Rudolf; Hackbusch, Wolfgang; Luderer, Bernd ; Blath, Jochen; Schied, Alexander; Dempe, Stephan; Wanka, Gert; Hromkovič, Juraj; Gottwald, Siegfried (2013) . Zeidler, Eberhard (ed.). Springer-Handbuch der Mathematik I (in German). Vol. I (1 ed.). Berlin / Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Spektrum, Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. p. 590. ISBN 978-3-658-00284-8. (xii+635 pages)

- Hass, Joel R.; Heil, Christopher E.; Weir, Maurice D.; Thomas, George B. (2018). Thomas' Calculus (14 ed.). Pearson. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9780134439020.

- ^ Anton, Howard; Bivens, Irl; Davis, Stephen (2012). Calculus: Early Transcendentals (9th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 28. ISBN 9780470647691.

- Denlinger, Charles G. (2011). Elements of Real Analysis. Jones and Bartlett. pp. 278–283. ISBN 978-0-7637-7947-4.

- Tao, Terence (2016). "Limits of sequences". Analysis I. Texts and Readings in Mathematics. Vol. 37. pp. 126–154. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-1789-6_6. ISBN 978-981-10-1789-6.

- Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001). Introduction to Algorithms (second ed.). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03293-3. Online resource Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- Cull, Paul; Flahive, Mary; Robson, Robby (2005). Difference Equations: From Rabbits to Chaos (Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-23234-8. Defined on p. 351.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Principal root of unity". MathWorld.

- Steiner, J.; Clausen, T.; Abel, Niels Henrik (1827). "Aufgaben und Lehrsätze, erstere aufzulösen, letztere zu beweisen" [Problems and propositions, the former to solve, the later to prove]. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik. 2: 286–287.

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1970). Algèbre. Springer. I.2.

- Bloom, David M. (1979). Linear Algebra and Geometry. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-521-29324-2.

- Chapter 1, Elementary Linear Algebra, 8E, Howard Anton.

- Strang, Gilbert (1988). Linear algebra and its applications (3rd ed.). Brooks-Cole. Chapter 5.

- E. Hille, R. S. Phillips: Functional Analysis and Semi-Groups. American Mathematical Society, 1975.

- Nicolas Bourbaki, Topologie générale, V.4.2.

- Gordon, D. M. (1998). "A Survey of Fast Exponentiation Methods" (PDF). Journal of Algorithms. 27: 129–146. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.17.7076. doi:10.1006/jagm.1997.0913. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2024-01-11.

- Peano, Giuseppe (1903). Formulaire mathématique (in French). Vol. IV. p. 229.

- Herschel, John Frederick William (1813) . "On a Remarkable Application of Cotes's Theorem". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 103 (Part 1). London: Royal Society of London, printed by W. Bulmer and Co., Cleveland-Row, St. James's, sold by G. and W. Nicol, Pall-Mall: 8–26 . doi:10.1098/rstl.1813.0005. JSTOR 107384. S2CID 118124706.

- Herschel, John Frederick William (1820). "Part III. Section I. Examples of the Direct Method of Differences". A Collection of Examples of the Applications of the Calculus of Finite Differences. Cambridge, UK: Printed by J. Smith, sold by J. Deighton & sons. pp. 1–13 . Archived from the original on 2020-08-04. Retrieved 2020-08-04. (NB. Inhere, Herschel refers to his 1813 work and mentions Hans Heinrich Bürmann's older work.)

- Cajori, Florian (1952) . A History of Mathematical Notations. Vol. 2 (3rd ed.). Chicago, USA: Open court publishing company. pp. 108, 176–179, 336, 346. ISBN 978-1-60206-714-1. Retrieved 2016-01-18.

- Richard Gillam (2003). Unicode Demystified: A Practical Programmer's Guide to the Encoding Standard. Addison-Wesley Professional. p. 33. ISBN 0201700522.

- Backus, John Warner; Beeber, R. J.; Best, Sheldon F.; Goldberg, Richard; Herrick, Harlan L.; Hughes, R. A.; Mitchell, L. B.; Nelson, Robert A.; Nutt, Roy; Sayre, David; Sheridan, Peter B.; Stern, Harold; Ziller, Irving (1956-10-15). Sayre, David (ed.). The FORTRAN Automatic Coding System for the IBM 704 EDPM: Programmer's Reference Manual (PDF). New York, USA: Applied Science Division and Programming Research Department, International Business Machines Corporation. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-07-04. Retrieved 2022-07-04. (2+51+1 pages)

- Brice Carnahan; James O. Wilkes (1968). Introduction to Digital Computing and FORTRAN IV with MTS Applications. pp. 2–2, 2–6.

- Backus, John Warner; Herrick, Harlan L.; Nelson, Robert A.; Ziller, Irving (1954-11-10). Backus, John Warner (ed.). Specifications for: The IBM Mathematical FORmula TRANSlating System, FORTRAN (PDF) (Preliminary report). New York, USA: Programming Research Group, Applied Science Division, International Business Machines Corporation. pp. 4, 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-03-29. Retrieved 2022-07-04. (29 pages)

- Daneliuk, Timothy "Tim" A. (1982-08-09). "BASCOM - A BASIC compiler for TRS-80 I and II". InfoWorld. Software Reviews. Vol. 4, no. 31. Popular Computing, Inc. pp. 41–42. Archived from the original on 2020-02-07. Retrieved 2020-02-06.

- "80 Contents". 80 Micro (45). 1001001, Inc.: 5. October 1983. ISSN 0744-7868. Retrieved 2020-02-06.

- Robert W. Sebesta (2010). Concepts of Programming Languages. Addison-Wesley. pp. 130, 324. ISBN 978-0136073475.

| Hyperoperations | |

|---|---|

| Primary | |

| Inverse for left argument | |

| Inverse for right argument | |

| Related articles | |

| Orders of magnitude of time | |

|---|---|

| by powers of ten | |

| Negative powers | |

| Positive powers | |

| Classes of natural numbers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

In particular,

In particular,  .

.

immediately implies several properties, in particular the multiplication rule:

immediately implies several properties, in particular the multiplication rule:

, and dividing both sides by

, and dividing both sides by  . That is, the multiplication rule implies the definition

. That is, the multiplication rule implies the definition  A similar argument implies the definition for negative integer powers:

A similar argument implies the definition for negative integer powers:  That is, extending the multiplication rule gives

That is, extending the multiplication rule gives  . Dividing both sides by

. Dividing both sides by  . This also implies the definition for fractional powers:

. This also implies the definition for fractional powers:  For example,

For example,  , meaning

, meaning  , which is the definition of square root:

, which is the definition of square root:  .

.

for any positive real base

for any positive real base  and any real number exponent

and any real number exponent  . More involved definitions allow

. More involved definitions allow

.

.

.

. ).

).

).

).

, but reversing the operands gives the different value

, but reversing the operands gives the different value  . Also unlike addition and multiplication, exponentiation is not

. Also unlike addition and multiplication, exponentiation is not

is a

is a  is a

is a  is undefined.

is undefined.

, or it is left undefined.

, or it is left undefined.

alternate between positive and negative as n alternates between even and odd, and thus do not tend to any limit as n grows.

alternate between positive and negative as n alternates between even and odd, and thus do not tend to any limit as n grows.

, where

, where  , are sometimes called power functions. When

, are sometimes called power functions. When  is an

is an  , two primary families exist: for

, two primary families exist: for  , when

, when  , flattening more in the middle as

, flattening more in the middle as  ) are called

) are called  's

's  , flattening more in the middle as

, flattening more in the middle as  . Functions with this kind of symmetry (

. Functions with this kind of symmetry ( ) are called

) are called  , the opposite asymptotic behavior is true in each case.

, the opposite asymptotic behavior is true in each case.

or

or  denotes the unique nonnegative real

denotes the unique nonnegative real

is a

is a  is defined as

is defined as

and writing

and writing

to rational exponents.

to rational exponents.

the identity

the identity  cannot be satisfied. For example,

cannot be satisfied. For example,

where

where  is

is  and of

and of  , relying only on positive integer powers (repeated multiplication). Then we sketch the proof that this agrees with the previous definition:

, relying only on positive integer powers (repeated multiplication). Then we sketch the proof that this agrees with the previous definition:

and the exponential identity (or multiplication rule)

and the exponential identity (or multiplication rule)  holds as well, since

holds as well, since

does not affect the limit, yielding

does not affect the limit, yielding  when x is an integer (this results from the repeated-multiplication definition of the exponentiation). If x is real,

when x is an integer (this results from the repeated-multiplication definition of the exponentiation). If x is real,  , and thus

, and thus  from the real numbers to any complex argument z. This extended exponential function still satisfies the exponential identity, and is commonly used for defining exponentiation for complex base and exponent.

from the real numbers to any complex argument z. This extended exponential function still satisfies the exponential identity, and is commonly used for defining exponentiation for complex base and exponent.

one must have

one must have

can be used as an alternative definition of b for any positive real b. This agrees with the definition given above using rational exponents and continuity, with the advantage to extend straightforwardly to any complex exponent.

can be used as an alternative definition of b for any positive real b. This agrees with the definition given above using rational exponents and continuity, with the advantage to extend straightforwardly to any complex exponent.

denotes the

denotes the

is not defined, since b is not a real number. If a meaning is given to the exponentiation of a complex number (see

is not defined, since b is not a real number. If a meaning is given to the exponentiation of a complex number (see

in terms of the

in terms of the

where n is a positive integer. Although the general theory of exponentiation with non-integer exponents applies to nth roots, this case deserves to be considered first, since it does not need to use

where n is a positive integer. Although the general theory of exponentiation with non-integer exponents applies to nth roots, this case deserves to be considered first, since it does not need to use

is the

is the  is its

is its  is also an argument of the same complex number for every integer

is also an argument of the same complex number for every integer  .

.

is added to

is added to  to the argument of the nth root, and provides a new nth root. This can be done n times, and provides the n nth roots of the complex number.

to the argument of the nth root, and provides a new nth root. This can be done n times, and provides the n nth roots of the complex number.

that is, the nth root that has the largest real part, and, if there are two, the one with positive imaginary part. This makes the principal nth root a

that is, the nth root that has the largest real part, and, if there are two, the one with positive imaginary part. This makes the principal nth root a  the complex number comes back to its initial position, and its nth roots are

the complex number comes back to its initial position, and its nth roots are  ). This shows that it is not possible to define a nth root function that is continuous in the whole complex plane.

). This shows that it is not possible to define a nth root function that is continuous in the whole complex plane.

, that is

, that is  The nth roots of unity that have this generating property are called primitive nth roots of unity; they have the form

The nth roots of unity that have this generating property are called primitive nth roots of unity; they have the form  with k

with k  the primitive fourth roots of unity are

the primitive fourth roots of unity are  and

and

is the primitive nth root of unity with the smallest positive

is the primitive nth root of unity with the smallest positive  , which is 1.

, which is 1.

. So, either a

. So, either a

is the variant of the complex logarithm that is used, which is a function or a

is the variant of the complex logarithm that is used, which is a function or a

such that, for every nonzero complex number z,

such that, for every nonzero complex number z,

it is

it is

is defined as

is defined as

is holomorphic except in the neighbourhood of the points where z is real and nonpositive.

is holomorphic except in the neighbourhood of the points where z is real and nonpositive.

where n is an integer, this principal value is the same as the one defined above.

where n is an integer, this principal value is the same as the one defined above.

where k is any integer. Similarly, if

where k is any integer. Similarly, if

if and only if

if and only if  is an integer multiple of

is an integer multiple of

is a rational number with m and n

is a rational number with m and n  then

then  these values are the same as those described in

these values are the same as those described in  in the sense that its

in the sense that its  of

of  is the canonical form of z (a and b being real), then its polar form is

is the canonical form of z (a and b being real), then its polar form is  and

and  , where

, where  is the

is the  where

where  denotes the

denotes the  for any integer k.

for any integer k. If

If  with c and d real, the values of

with c and d real, the values of  are

are  the principal value corresponding to

the principal value corresponding to

and

and  one gets

one gets  with

with  for the principal value.

for the principal value.

and the values of

and the values of  are thus

are thus  It follows that

It follows that  So, all values of

So, all values of

So, the above described method gives the values

So, the above described method gives the values  In this case, all the values have the same argument

In this case, all the values have the same argument  and different absolute values.

and different absolute values.

and

and

On the other hand, when x is an integer, the identities are valid for all nonzero complex numbers.

If exponentiation is considered as a multivalued function then the possible values of (−1 ⋅ −1) are {1, −1}. The identity holds, but saying {1} = {(−1 ⋅ −1)} is incorrect.

On the other hand, when x is an integer, the identities are valid for all nonzero complex numbers.

If exponentiation is considered as a multivalued function then the possible values of (−1 ⋅ −1) are {1, −1}. The identity holds, but saying {1} = {(−1 ⋅ −1)} is incorrect.

(taking the

(taking the  -th power of both sides)

-th power of both sides) (using

(using  and expanding the exponent)

and expanding the exponent) (using

(using  (dividing by e)

(dividing by e) is a notation for

is a notation for  a true function, and

a true function, and  is a notation for

is a notation for  which is a multi-valued function. Thus the notation is ambiguous when x = e. Here, before expanding the exponent, the second line should be

which is a multi-valued function. Thus the notation is ambiguous when x = e. Here, before expanding the exponent, the second line should be

Therefore, when expanding the exponent, one has implicitly supposed that

Therefore, when expanding the exponent, one has implicitly supposed that  for complex values of z, which is wrong, as the complex logarithm is multivalued. In other words, the wrong identity (e) = e must be replaced by the identity

for complex values of z, which is wrong, as the complex logarithm is multivalued. In other words, the wrong identity (e) = e must be replaced by the identity

which is a true identity between multivalued functions.

which is a true identity between multivalued functions. then at least one of b, x and b is transcendental.

then at least one of b, x and b is transcendental.

for every nonnegative integer n.

for every nonnegative integer n. is defined only if x has a

is defined only if x has a

denotes the exponentiation with respect of multiplication, and

denotes the exponentiation with respect of multiplication, and  may denote exponentiation with respect of

may denote exponentiation with respect of

is denoted

is denoted  while

while  is denoted

is denoted

and every integer n.

and every integer n.

of the integers. Otherwise, the cyclic group is

of the integers. Otherwise, the cyclic group is  and the cyclic group generated by x consists of the n first powers of x (starting indifferently from the exponent 0 or 1).

and the cyclic group generated by x consists of the n first powers of x (starting indifferently from the exponent 0 or 1).

and

and

for some integer n. Such an element is said to be

for some integer n. Such an element is said to be  implies

implies  for every positive integer n), the commutative ring is said to be

for every positive integer n), the commutative ring is said to be  over a

over a  is defined to be the identity matrix, and if A is invertible, then

is defined to be the identity matrix, and if A is invertible, then  .

.

is the state of the system after two time steps, and so forth:

is the state of the system after two time steps, and so forth:  is the state of the system after n time steps. The matrix power

is the state of the system after n time steps. The matrix power  is the transition matrix between the state now and the state at a time n steps in the future. So computing matrix powers is equivalent to solving the evolution of the dynamical system. In many cases, matrix powers can be expediently computed by using

is the transition matrix between the state now and the state at a time n steps in the future. So computing matrix powers is equivalent to solving the evolution of the dynamical system. In many cases, matrix powers can be expediently computed by using  , which is a linear operator acting on functions

, which is a linear operator acting on functions  . The nth power of the differentiation operator is the nth derivative:

. The nth power of the differentiation operator is the nth derivative:

where p is a prime number, and k is a positive integer. For every such q, there are fields with q elements. The fields with q elements are all

where p is a prime number, and k is a positive integer. For every such q, there are fields with q elements. The fields with q elements are all

is an element g such that the set of the q − 1 first powers of g (that is,

is an element g such that the set of the q − 1 first powers of g (that is,  ) equals the set of the nonzero elements of

) equals the set of the nonzero elements of  primitive elements in

primitive elements in  where

where  is

is

in

in

can be efficiently computed with

can be efficiently computed with  such that

such that  and

and  This operation is not properly

This operation is not properly

and

and

of a set S as the set of all n-

of a set S as the set of all n- of elements of S.

of elements of S.

(where

(where  denotes the real numbers) denotes the Cartesian product of n copies of

denotes the real numbers) denotes the Cartesian product of n copies of  as well as their direct product as

as well as their direct product as  This generalizes to the following notation.

This generalizes to the following notation.

. This exponential notation is justified by the following canonical isomorphisms (for the first one, see

. This exponential notation is justified by the following canonical isomorphisms (for the first one, see

denotes the Cartesian product, and

denotes the Cartesian product, and  the

the  denotes the vector space of the

denotes the vector space of the  the vector space of those sequences that have a finite number of nonzero elements. The latter has a

the vector space of those sequences that have a finite number of nonzero elements. The latter has a  So,

So,  denotes the

denotes the  which can be identified with the set of the

which can be identified with the set of the  in the preceding section can also be denoted

in the preceding section can also be denoted  The isomorphism

The isomorphism  can be rewritten

can be rewritten

is, if it exists, a right adjoint to the functor

is, if it exists, a right adjoint to the functor  A category is called a Cartesian closed category, if direct products exist, and the functor

A category is called a Cartesian closed category, if direct products exist, and the functor  has a right adjoint for every T.

has a right adjoint for every T.

defined on

defined on  . Then D can be viewed as a subset of R (that is, the set of all pairs (x, y) with x, y belonging to the

. Then D can be viewed as a subset of R (that is, the set of all pairs (x, y) with x, y belonging to the  .

. by using

by using  denotes the number of 1s in the

denotes the number of 1s in the  and defined as

and defined as

means

means

and

and  When functional notation is not used, disambiguation is often done by placing the composition symbol before the exponent; for example