Medical intervention

| Treatments for PTSD | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

| [edit on Wikidata] | |

PTSD or post-traumatic stress disorder, is a psychiatric disorder characterised by intrusive thoughts and memories, dreams or flashbacks of the event; avoidance of people, places and activities that remind the individual of the event; ongoing negative beliefs about oneself or the world, mood changes and persistent feelings of anger, guilt or fear; alterations in arousal such as increased irritability, angry outbursts, being hypervigilant, or having difficulty with concentration and sleep.

Many people who have PTSD also experience feeling detached or distanced from their friends and family. It is not uncommon for people with PTSD to experience the disorder simultaneously with other psychiatric illnesses like anxiety disorder, depression and substance use disorder. Uncovering any comorbidities is an important part in moving forward with treatment and finding one that works best for each unique individual.

Exposure to trauma induces stress as a result of an individual directly or indirectly experiencing some type of threat to life, also referred to as a Potentially Traumatic Experience (PTE). PTEs can include—but are not limited to—sexual violence, physical abuse, death of a loved one, witnessing another person injured, exposure to natural disaster, being a victim of a serious crime, car accident, combat and interpersonal violence. PTEs can also include learning that a traumatic event occurred to another person or witnessing the traumatic event; an individual does not have to experience the event themselves to develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

PTEs are labeled as such because not everyone who experiences one or more of the events listed will develop PTSD. However, PTSD is estimated to develop in about 4% of individuals who experience some type of traumatic experience. The prevalence of PTSD will vary due to individual differences such as population characteristics, previous trauma exposure, trauma type, military service history and other personal differences. Approximately 8% of adults in the United States will experience PTSD at some point in their lives. Stress responses can be adaptive at the time of the traumatic event, but biological stress responses over time can lead to symptoms that impede daily functioning and general quality of life. This is when trauma exposure becomes PTSD.

PTSD is commonly treated with various types of psychotherapy and antidepressants. Everyone is very different in terms of how they respond to different treatments and medications. Because people experience different symptoms of PTSD, they will need the therapy they choose to target different things, and therefore act in different ways. People may need to try different combinations of treatments to find the one that works best for them. Regardless of what type of treatment someone chooses, it is important to go to a trained professional first who has experience with treating PTSD, and can help the patient through their recovery journey. The Anxiety and Depression Association of America recommends anyone experiencing symptoms longer than a few weeks that interfere with daily functioning to seek professional help.

Psychotherapy

Evidence-based, trauma-focused psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for PTSD. Psychotherapy is defined as a treatment where a therapist and patient build a therapeutic relationship and focus on the patient's thoughts, attitudes, affect, behavior, and social development to lessen the patient's psychopathologies and functional impairment.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Main article: Cognitive behavioral therapyCognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) focuses on the relationship between someone's thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. It helps people understand the discrete nature of their thoughts and feelings, and to be better able to control and relate to them. It began with the work of American psychologist Albert Ellis in the late 1950s, and was notably expanded on by American psychiatrist Aaron Beck.

CBT involves exposure to the trauma narrative in a controlled way to reduce avoidance behaviors related to the trauma. Education about the effects of trauma and stress management techniques are common aspects of CBT. There is evidence that CBT combined with exposure therapy can reduce PTSD symptoms, lead to a loss of PTSD diagnosis, and reduce depression symptoms.

Some common CBT techniques are:

- Cognitive restructuring: exchanging negative thoughts for positive ones.

- Exposure therapy

- Cognitive processing therapy: patients are encouraged to consider the factual basis of their thoughts.

- Stress inoculation training: patients are taught relaxation techniques such as breathing, progressive muscle relaxation skills, and communication coping skills.

- Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: a back and forth eye movement that helps patients process traumatic events.

- Acceptance and commitment therapy: focuses on accepting the traumatic event rather than challenging it.

CBT is strongly recommended for treatment of PTSD by the American Psychological Association. The most applicable techniques vary from person to person, with no current front-runner showing any particular advantage over the other.

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy

Main article: Trauma focused cognitive behavioral therapyTrauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) was developed by Anthony Mannarino, Judith Cohen, and Esther Deblinger in the mid-1990s to help children and adolescents with PTSD.

Individuals work through the memories of the trauma in a safe and structured environment, trying to correct negative cognitions and thoughts while also performing gradual exposure to triggers. This therapy is held over 8 to 25 sessions with the child/adolescent and their caregiver. The treatment helps correct distorted beliefs in the children while also helping parents and caregivers process their own distress and support the children.

Researchers are working to develop culturally-adapted versions of TF-CBT. Cultural adaptations may rely on targeting the unique experience of a group, such as chronic exposure to racial trauma, or culture-specific coping strategies, such as including racial socialization and community support. In recent years, psychologists have tested the effectiveness of culturally modified TF-CBT approaches with different communities, such as unaccompanied child migrants and women in war-torn countries. Research suggests that cultural adaptations to TF-CBT can improve intervention effectiveness.

TF-CBT has repeatedly demonstrated effectiveness and is currently recommended as a first-line treatment for PTSD by the American Psychological Association, Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health, and the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE). The Australian Psychological Society considers it a Level I (strongest evidence) treatment method.

Cognitive therapy for PTSD (Ehlers and Clark)

In 2000, husband-and-wife Anke Ehlers and David M Clark developed a cognitive model that explains what prevents people from recovering from traumatic experiences and thus why people develop PTSD. The model suggests that PTSD develops when individuals process the traumatic event in a way that makes them feel that there is serious current threat. This perception of a threat is followed by reexperiencing arousal symptoms and persistent negative emotions like anger and sadness. Differences in how the individual appraises the event ("I cannot trust anyone anymore" or "I should have prevented what happened") and the poor integration of the most intense moments of the trauma into memory contribute to the distorted way people with PTSD make sense of what happened to them.

Ehlers, Clark and others developed a cognitive therapy based on this model, the details of which were first published in 2005. It is a form of cognitive behavioural therapy that involves developing and believing a new, less threatening understanding of the trauma experiences. Patients gain an increased understanding of how they perceive themselves and the world around them, and how these beliefs motivate their behavior, before beginning the process of changing these thought patterns. Thus, three goals drive cognitive therapy for PTSD:

- Modify negative appraisals of the trauma

- Reduce reexperiencing symptoms by discussing trauma memories and learning how to differentiate between types of trauma triggers

- Reduce behaviors and thoughts that contribute to the maintenance of the "sense of current threat"

One specific practice is imagery rescripting where the therapist guides the patient to reimagine their traumatic memory in a way that gives them control so that they can create new outcomes. For example, adult patients with childhood trauma are encouraged to imagine their trauma from the point-of-view of an adult rescuing and protecting the vulnerable child.

Imagery rehearsal therapy helps people with nightmares by documenting their dreams and creating new endings to them. They then write down their dreams, monitor them, and regularly act out the improved dream scenarios.

"Cognitive therapy" of this kind should not be confused with the earlier established cognitive therapy of Aaron Beck.

Ehlers and Clark inspired cognitive therapy is strongly recommended for treatment of PTSD by the American Psychological Association.

Prolonged exposure therapy

Main article: Prolonged exposure therapyProlonged exposure therapy (PE) was developed by Edna Foa and Micheal J Kozak from 1986. It has been extensively tested in clinical trials. While, as the name suggests, it includes exposure therapy, it also includes other psychotherapy elements. Foa was chair of the PTSD work group of the DSM-IV.

Prolonged exposure therapy typically consists of 8 to 15 weekly, 90 minute sessions. Patients will first be exposed to a past traumatic memory (imaginal exposure), after which they immediately discuss the traumatic memory and then are exposed to, "safe, but trauma-related, situations that the client fears and avoids".

Slowed breathing techniques and psychoeducation are also touched on in these sessions.

PE is theoretically grounded in emotional processing theory, which proposes "a hypothetical sequence of fear-reducing changes evoked by emotional engagement with the memory of a significant event, particularly a trauma." While PE has received substantial empirical support for its efficacy (albeit with high dropout rates), emotional processing theory has received mixed support.

PE is strongly recommended as a first-line treatment for PTSD by the American Psychological Association.

Cognitive processing therapy

Main article: Cognitive processing therapyCognitive processing therapy (CPT) was developed by Patricia Resick from 1988. Is an evidence-based treatment aimed at individuals diagnosed with PTSD. This therapy focuses on processing and working through the trauma, designed using techniques from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy discussed previously. CPT is founded on the principle that generally, individuals can gradually recover from traumatic events over time, but in those diagnosed with PTSD, this recovery pathway is impaired. During therapy sessions, clients write and recite written passages either related to why the individual thinks they were exposed to the traumatic event, or narratives outlining the event in explicit detail. CPT is typically completed over 12 one-hour weekly sessions with a practitioner.

The first phase of treatment is psychoeducation. During this part of therapy, individuals learn about the relationship between thoughts and emotions, and importantly, they look for "automatic thoughts" that are detrimental to their recovery. This initial phase ends as patients write their understanding of the causes of the traumatic event and its impacts.

The second phase is concerned with processing the trauma: outlining the traumatic experience and continuing to discuss the experience and feelings over the following sessions. During this stage, the therapist tries to identify and correct negative cognitions that may lead to continued PTSD symptoms.

The final phase assists the individual in strengthening beliefs, skills, and strategies to combat the symptoms of the trauma when they arise.

CPT is a strongly recommended treatment for PTSD by the American Psychological Association.

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing

Main article: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessingEye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) was developed by Francine Shapiro in 1988 as a method to diminish the impacts of traumatic memories. During treatment, patients are asked to focus on specific distressing memories while at the same time undergoing bilateral stimulation. This is usually performed through eye movements or other forms of stimulation to both sides of the body such as tones and tapping. The patient discusses their distressing thoughts as the therapist reinforces positive cognitions and utilizes strategies such as a body scan. These sessions are usually once or twice a week for about 6 to 12 weeks. By the end of these sessions, individuals usually demonstrate reduced emotional distress related to the traumatic event.

The methodology behind EMDR focuses on the Adaptive Information Processing model of PTSD in which the PTSD symptoms are caused by the impaired processing of the traumatic memory. The symptoms arise when the memories are triggered, bringing back the emotions and sensations of the trauma. Therapy with the incorporation of EMDR has been shown to aid patients in processing distressing memories and reducing their harmful effects.

A proposed neurophysiological basis behind EMDR is that it mimics REM sleep, which plays a vital role in memory consolidation. Imaging studies suggest that "eye movements in both REM sleep and wakefulness activate similar cortical areas". The bilateral stimulation facilitated by EMDR "shifts the brain into a memory processing mode", reintegrating the traumatic events with more positively reinforced cognitions. The information can then be integrated completely to lessen the symptoms of triggers. The restoration of the pathway can help with recovery from traumatic events.

A 2018 review reported EMDR for PTSD was supported by moderate quality evidence as of 2018. It is a conditionally recommended treatment for PTSD by the American Psychological Association. The Australian Psychological Society considers it a Level I (strongest evidence) treatment method. However, it has separately been classified as a purple hat therapy, and the US National Institute of Medicine found insufficient evidence to recommend it as of 2008.

Narrative exposure therapy

Main article: Narrative exposure therapyNarrative exposure therapy creates a written account of the traumatic experiences of a patient or group of patients, in a way that serves to recapture their self-respect and acknowledges their value. Under this name it is used mainly with refugees, in groups. It also forms an important part of cognitive processing therapy. Patients are asked to narrate their life-story while staying in the present moment. They receive an autobiography at the end from their therapist and this often serves as motivation to complete their narration.

It is conditionally recommended for treatment of PTSD by the American Psychological Association.

Brief eclectic psychotherapy

Main article: Eclectic psychotherapyBrief eclectic psychotherapy (BEP) for PTSD was developed by Berthold Gersons and Ingrid Carlier in 1994. It emphasizes the psychodynamic perspective of shame and guilt in addition to the principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy. In 16 sessions, patients create a detailed account of the primary trauma experience, explore the connected emotional reactions, and how to move forward. The first few sessions deal with the traumatic experience as well as reliving the event in the present using objects or core memories. Through this process, the client discusses upsetting feelings and emotions as the therapist helps them to process the event.

The individual also writes a letter to the person or group they feel holds responsibility for the trauma although it is not sent. The therapists then assist the individual in assessing the impacts of the trauma from beliefs to physical changes to help them learn and grow from the event instead of avoiding and fearing the impacts. Finally, the therapist helps to develop relapse prevention methods and looks forward to a better future.

It is a conditionally recommended treatment for PTSD by the American Psychological Association.

Dialectical behavioral therapy

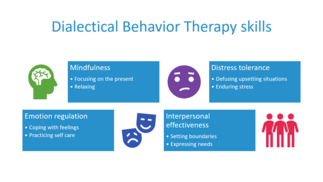

Dialectical behavioral therapy is a branch of cognitive behavioral therapy aimed at helping individuals to "accept the reality of their lives". Therapists use strategies such as behavioral therapy techniques and mindfulness to address thoughts and behaviors, and help individuals to regulate and change these. It is usually recommended and used in patients with borderline personality disorder and other personality disorders which are difficult to treat. The specific skills focused on are mindfulness, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, and emotional regulation. The main goal of DBT is to help clients manage their treatment and better understand their symptoms. The focus of DBT for PTSD is the future and adapting to the symptoms of the trauma.

The Australian Psychological Society considers dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) to be a Level II treatment method.

Emotion focused therapy

Main article: Emotionally focused therapyEmotion focused therapy (EFT) was developed by Leslie S. Greenberg and Sue Johnson in the 1980s. It advocates that emotional change is necessary for permanent or enduring change in clients' growth and well-being. EFT draws on knowledge about the effect of emotional expression and identifies the adaptive potential of emotions as critical in creating meaningful psychological change. A major premise of EFT is that emotion is fundamental to the construction of the self and is a key determinant of self-organization. At the most basic level of functioning, emotions are an adaptive form of information-processing and action readiness that orient people to their environment and promote their well-being. EFT suggests that the developing cortex added the ability for complex learning to the emotional brain in-wired emotional responses.

EFT has also been found to be effective in treating abuse, resolving interpersonal problems, and promoting forgiveness. EFT has a high effective rate in people who suffer from childhood abuse and trauma. There are studies of EFT being used for couple interventions for people who have a partner in the military with PTSD, which is EFT's unique approach to helping combat PTSD within service members. Studies have shown that PTSD can lead to decreased marital satisfaction, increased verbal and physical aggression, and heightened sexual dissatisfaction. It was also shown that negative social support intensifies PTSD. Couple interventions for PTSD have strong promise to not only treat PTSD in service members, but also to treat many of the other relational and family issues related to coping with deployment and deployment-related PTSD.

The Australian Psychological Society considers emotion focused therapy (EFT) to be a Level II treatment method.

Metacognitive therapy

Main article: Metacognitive therapyMetacognition is a branch of cognition that is responsible for thinking and other mental processes. Most people have some conscious awareness of their metacognition such as when they know of something but cannot recall it right now. This is also called the 'tip-of-the-tongue' effect. Metacognitions control the negative thoughts and ruminations prevalent in many psychiatric diseases such as PTSD.

Metacognitive therapy (MCT) was developed by Adrian Wells and is based on an information processing model by Wells and Gerald Matthews. This psychotherapy aims at changing metacognitive beliefs that focus on states of worry, rumination, and attention fixation. As per the metacognitive model, the symptoms are caused by worry, threat monitoring, and coping behaviors that are thought to be helpful but actually backfire. These three processes are called the cognitive attentional syndrome (CAS).

Through MCT, patients first discover their own metacognitive beliefs, then are shown how these beliefs lead to unhelpful responses, and finally are taught how to respond to these beliefs in a productive way. MCT typically lasts for around 8-12 sessions and therapy includes experiments, attentional training technique, and detached mindfulness.

MCT has been used successfully to treat social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), health anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). MCT has been shown to treat PTSD better than Prolonged Exposure (PE). It has also shown clinically significant results for different causes of PTSD such as accident survivors, and assault and rape victims.

The Australian Psychological Society considers metacognitive therapy (MCT) to be a Level II treatment method.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction

Main article: Mindfulness-based stress reductionMindfulness-based stress reduction is an eight-week program that helps train people to help with their stress, anxiety, depression, and pain. It was developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn in the 1970s. The program uses a combination of mindfulness meditation, body awareness, yoga, and exploration of patterns of behavior, thinking, feeling, and action. One of the main concepts in mindfulness is accepting and not judging oneself or others while developing increased emotional regulation. People can participate in this type of therapy while in a structured program, or practice mindfulness meditation on their own.

The Australian Psychological Society considers mindfulness-based stress reduction to be a Level II treatment method.

Exposure therapy

Main article: Exposure therapyExposure therapy involves exposing the patient to PTSD-anxiety-triggering stimuli, with the aim of weakening the neural connections between triggers and trauma memories (aka desensitization).

Forms include:

- Flooding – exposing the patient directly to a triggering stimulus, while simultaneously making them not feel afraid.

- Systematic desensitization (aka "graduated exposure") – gradually exposing the patient to increasingly vivid experiences that are related to the trauma, but do not trigger post-traumatic stress.

Exposure may involve a real life trigger ("in vivo"), an imagined trigger ("imaginal"), or a triggered feeling generated in a physical but harmless way ("interoceptive").

Researchers began experimenting with virtual reality therapy in PTSD exposure therapy in 1997 with the advent of the "Virtual Vietnam" scenario. Virtual Vietnam was used as a graduated exposure therapy treatment for Vietnam veterans meeting the qualification criteria for PTSD. A 50-year-old Caucasian male was the first veteran studied. The preliminary results concluded improvement post-treatment across all measures of PTSD and maintenance of the gains at the six-month follow up. Subsequent open clinical trial of Virtual Vietnam using 16 veterans, showed a reduction in PTSD symptoms.

Exposure therapy remains a controversial form of therapy to treat PTSD. Those suffering with extreme re-experiencing and arousal symptoms may find exposure to be triggering. Confronting trauma too early after a traumatic event may be upsetting and only worsen symptoms for patients; severe negative reactions include self harm, panic disorder, dissociative disorder, and even suicidal thoughts. It is suggested exposure therapy, if used, should be resorted to only as second line of treatment—therapy ought to first focus on stabilizing and solving present symptoms before incorporating exposure.

Occupational therapy

Main article: Occupational therapyOccupational therapy (OT) assists individuals in meaningful daily activities. OT helps individuals in response to an impairment such as an illness, disability, or in the case of PTSD, a traumatic event.

Sleep disturbances such as insomnia, night terrors, and inconsistent REM sleep impact the lives of many with PTSD. Occupational therapists are equipped to address this meaningful area through sleep hygiene. Some examples of this technique are reducing screen time, developing nighttime routines, and creating a safe and quiet environment within the bedroom. Another meaningful area of occupational therapy is self-care. Occupational therapists provide education and adaptation/modification in self-care to maintain independence and prevent triggers that may cause flashbacks.

Occupational therapists help clients with PTSD engage in meaningful life roles in daily lives, leisure, and work activities through healthy habit formation and stable daily routines while managing PTSD triggers. Social engagement can be challenging for those with PTSD, and as such, occupational therapists work with their clients to help build a supportive social network of family and friends who can assist in reducing this stress. Occupational therapy interventions also include stress management and relaxation techniques such as deep breathing, mindfulness, meditation, progressive muscle relaxation, and biofeedback. The goal is to help clients adjust to the demands of daily life.

Occupational Therapy interventions are wide ranging, from group therapy to therapy tailored to the specific cause of PTSD. Other more unique OT interventions include, high intensity sports, role playing scenarios, and sensory modulation therapy. One specific study with promising results, analyzed a sports-oriented OT intervention using surfing to help veterans with PTSD return to civilian life.

Positive psychology

Main article: Positive psychologyPositive psychology coaching has been used as PTSD treatment, described as a strengths-focused method centered around reducing arousal states, meeting goals, and cultivating self-control. Past successful case studies of positive psychology interventions begin with journaling on strengths, completing a craft with fellow veterans, and group reflections answering positive psychology prompts.

Stress inoculation training

Main article: Stress exposure trainingStress inoculation training was developed to reduce anxiety in doctors during times of intense stress by Donald Meichenbaum in 1985. It is a combination of techniques including relaxation, negative thought suppression, and real-life exposure to feared situations used in PTSD treatment. The therapy is divided into four phases and is based on the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy. The first phase identifies the individual's specific reaction to stressors and how they manifest into symptoms. The second phase helps teach techniques to regulate these symptoms using relaxation methods. The third phase deals with specific coping strategies and positive cognitions to work through the stressors. Finally, the fourth phase exposes the client to imagined and real-life situations related to the traumatic event. This training helps to shape the response to future triggers to diminish impairment in daily life.

Biological interventions

Biological therapy, which can also be referred to as biomedical therapy or biological interventions are any form of treatment for mental disorders that attempts to alter physiological functioning, including drug therapies, electroconvulsive therapy, and psychosurgery.

Medication

Pharmacotherapy is used to treat PTSD. A second-line treatment refers to a treatment that is used after the initial treatment has been shown to be unsuccessful or has stopped working when treating a specific condition.

Antidepressants

Antidepressants are widely used in the treatment of PTSD. The most popular types are SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and SNRIs (serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors). SSRIs and SNRIs are recommended as the first-choice medication for people with PTSD by both the VA (US Department of Veteran Affairs) and APA (American Psychological Association). According to the APA Practice Guidelines, "SSRIs have proven efficacy for PTSD symptoms and related functional problems". Despite this, it has been estimated that around 40-60% of patients with PTSD do not respond to SSRIs.

The only two medications for PTSD that are approved by the FDA are sertraline (Zoloft) and paroxetine (Paxil), both antidepressants of the SSRI class. The APA clinical practice guideline also recommends the SSRI fluoxetine and the SNRI venlafaxine.

Many people who have PTSD take antidepressants and inhibitors to help cope with sleeping disorders, panic attacks, depression, and anxiety attacks. There is evidence that antidepressants and inhibitors, such as tricyclics, SSRI, and MAOI antidepressants have demonstrated efficacy in larger, longer-term controlled trials.

The efficacy of SSRIs in mild or moderate cases of depression have been disputed and may or may not be outweighed by side effects, especially in adolescent populations. There are only two FDA approved SSRI drugs for PTSD, paroxetine and sertraline. Neither are fully effective but paroxetine has a higher efficacy rate than sertraline. MAOI antidepressants block the actions of monoamine oxidase enzymes. Monoamine oxidase enzymes are responsible for breaking down neurotransmitters such as dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin in the brain. Low levels of these three neurotransmitters have been linked with depression and anxiety. By blocking these enzymes, scientists believe that it helps relieve symptoms of depression. MAOI antidepressants are often used as a last resort because they have a higher risk of drug interactions than standard antidepressants and can also interact with certain types of food such as aged cheeses and cured meats.

Alternative and complementary therapies

Alternative medicine is any product or practice that is not considered part of standard medical care. Standard medical care, also known as standard of care, best practice, or standard therapy, is any treatment that is widely accepted as proper and correct by medical professionals. Complementary medicine is a treatment that is used alongside standard medical care, but is not part of that category itself. One example of this is acupuncture, hypnosis, or meditation. Alternative medicine, on the other hand, is used instead of standard medical care. These treatments may include specialised diets or the use of vitamins or herbs. In the recent decade, alternative and complementary treatments have shown increasing promise in treating people with post traumatic stress disorder and have gained general popularity. In the United States, approximately 38% of adults and 12% of children use complementary or alternative medicines.

Relaxation techniques may be the earliest behavioral treatment for PTSD, and are often included as part of PTSD treatment. They can use relaxing movements such as successively tensing and relaxing muscles and works by reducing the fear associated with traumatic responses. Other relaxation techniques include meditation, deep breathing, massages, and yoga.

Yoga therapy treatment

Yoga has shown promise of reducing symptoms of PTSD when is it used alongside other treatments. Yoga promotes a mind and body connection that can help empower people to embrace their own general wellness. Yoga also increases affect awareness and can help people learn to regulate their emotions, which can be instrumental in helping people overcome symptoms of PTSD.

A randomised controlled trial including 209 participants, mainly veterans, showed a decrease in the severity of PTSD symptoms among the group that participated in a yoga program, as opposed to another group that participated in a wellness lifestyle program. After 16 weeks, the yoga group displayed a statistically significant decrease in PTSD symptoms compared to the other group. Some of these symptoms that were improved included sleep quality, emotional awareness, depression, anxiety, and others. The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale and the PTSD checklist were used to assess PTSD symptoms. A statistically significant difference between the two groups was not found again at a 7-month follow up, suggesting that this sort of therapy may be best used in addition to other types of treatments.

Other studies have shown similar, promising effects on symptoms of PTSD. Among these, there was a randomised controlled trial using 64 women with chronic, treatment resistant PTSD. A control was compared to a group that participated in yoga and another group that attended supportive women's health education classes. Statistically significant differences were found between all three of these groups, the yoga group seeing the most drastic reduction in symptoms of PTSD. This option is usually very accessible and easy for people to do in conjunction with other treatments.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is a practice using small needles to penetrate the skin in specific areas of the body to stimulate the nervous system. This technique has evolved from traditional Chinese medicine that utilizes over 2000 acupuncture points to change energy flow in the body.

Individuals with PTSD often have several comorbidities and acupuncture has been shown to assist in diminishing these symptoms. The evidence for this practice are based in the stimulation of the "autonomic nervous system, and the prefrontal as well as limbic brain structures, making it able to relieve the symptoms of PTSD". This stimulation leads to the production and regulation of hormones and neurotransmitters especially those related to pain management like endogenous opioids. Acupuncture is a safe practice that shows promise in the field of many health conditions and research supports the practice in reducing PTSD symptoms.

Group therapy

Group therapy can take on many forms. Group cognitive behavioral therapy and group exposure therapy are the most common types. The format of group cognitive behavioral therapy is based on participants connecting and sharing past experiences while developing trust. Since World War II, the method of having soldiers come together and converse amongst each other has been in practice. This type of therapy can be a good option for people because it is often more accessible and cheaper.

Studies have also shown various therapeutic benefits for group therapy. For example, group therapy allows people to work together and form meaningful relationships. It also helps people develop their communication skills. Another very important aspect is showing people who have PTSD that they are not alone. Oftentimes, group therapy can give people a community to support them when they feel detached from other people in their lives.

As with any form of treatment, there are concerns for group therapy and it will not be the best option for every individual. One concern is that people will compare their trauma and experiences to others in a group setting, instead of learning and helping each other.

Animal-assisted intervention

Animal-assisted intervention, previously referred to as animal-assisted therapy, is any therapy that includes animals in the treatment. This sort of treatment can be classified by the type of animal, the targeted population, and how the animal is incorporated into the therapeutic plan. The goal of animal-assisted intervention is to improve a patient's social, emotional, or cognitive functioning and literature reviews state that animals can be useful for educational and motivational effectiveness for participants.

The most commonly used types of animal-assisted intervention are canine-assisted therapy and equine-assisted therapy. Canine therapy, because it is much more easily accessible, is the most commonly used form of animal assisted therapy. Service dogs have shown a lot of promise in mitigating PTSD symptoms, specifically among the veteran population. The mechanism for this may be that dogs help instil a sense of confidence and safety in their owner. They can also act as a companion for individuals who may otherwise experience detachment or feeling isolated and alone.

Various studies, as well as lots of anecdotal evidence, have shown reduction in PTSD symptomatology with the use of service dogs and canine therapy. Physiologically, the presence of animals has been linked to the release of oxytocin and the reduction in anxious arousal symptoms, which is one of the most intrusive symptoms in many people with PTSD. The most promising findings indicate the efficacy of animal assisted therapy used with other types of therapy.

Equine therapy has also proved to be helpful for many populations with PTSD. There are both physical and psychological benefits to equine therapy and therapeutic horseback riding. The physical benefits may include improved posture and balance, decreased muscle tension, and reduction of pain. Psychological benefits include increased self efficacy, motivation, and courage, reduction in psychological stress, and enhanced psychological well-being. Equine therapy has been shown to be most effective when done over long periods of time.

While equine and canine therapies are the most common, other animals, like pigs, have also been used to help treat people with PTSD. There are many different ways to participate in this type of therapy. People should pick whatever works best for them and is accessible, if this options speaks to them.

Present centered therapy

Present centered therapy (PCT) was initially developed as a nonspecific comparison condition to test the effectiveness of trauma focused cognitive behavioral therapy in two large studies conducted by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. PCT focuses on adapting to life stressors and developing responses to those stressors, and can be done in a group format or with an individual. Sessions will range from 60 to 90 minutes. Session numbers range from 12 to 32 for group sessions and 10-12 for individuals.

The first two sessions in group or individual format include an overview of PCT and education about PTSD symptoms and responses to trauma. After these two preliminary sessions, the rest of the sessions are more free form, usually focusing on topics chosen by the patient/patients. Patients are also encouraged in this type of therapy to keep a journal and note issues/concerns that come up throughout their week.

Meditation

Many studies suggest that meditation can reduce the symptoms of PTSD, particularly in war veterans. These studies show that meditation reduces stress hormones by calming the sympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for the 'fight-or-flight' response to danger. Researchers found that practicing transcendental meditation can help reduce or even reverse symptoms of PTSD and associated depression. Specifically for this study, after 3 months of meditation, the group, on average, recovered from PTSD.

Somatic therapy

See also: Somatic experiencingDuring somatic therapy, a person works with a therapist to modify the trauma-related stress response produced by their body. In addition to helping with emotional regulation, somatic therapy can also reduce trauma-related pain, disability, insomnia, and other manifestations of stress.

Some common somatic therapy techniques are:

- Body awareness: Learning to notice and identify feelings of tension and calmness in the body.

- Grounding and centering: Using inherent self-awareness to connect with, manage, and mitigate feelings of distress as they arise.

- Titration: The therapist guides the patient through recounting a traumatic memory while describing any tension or physical sensations that occur in the process.

- Sequencing: The patient is asked to closely monitor the order in which sensations and tension leave the body, such as a tightening in the chest and a trembling as the tension dissipates.

- Pendulation: The therapist guides the patient from a relaxed state to one that feels similar to their traumatic experience, allowing the patient to release pent-up pain and emotion.

With these techniques, a person learns how to safely release built-up energy, pain, and emotions stemming from trauma. This allows a person to heal and move on from their PTSD triggers gradually. More research is needed before the American Psychological Association can list somatic therapy as a recommended treatment, but initial evidence has found it to be effective.

Multicultural perspectives

Trauma is ingrained in culture, and different cultures receive and treat trauma in different ways. Some cultures treat trauma with ancient practices such as praying or ritual.

The term "historical trauma" (HT) gained currency in the clinical and health science literature in the first two decades of the 21st century. It is defined as ongoing trauma experienced across generations by a group that shares an identity, affiliation, or circumstance. Native Americans, African Americans, Holocaust survivors, and Irish people are communities who may experience historical trauma.

In the case of Native Americans, many therapists use "a return to indigenous traditional practices" as a form of treatment for HT. This is very different from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or SSRIs that may be prescribed for someone with PTSD. The goal of this kind of treatment is not "adaptation" or cognitive restructuring of the individual to the prevailing cultural norm, "but rather spiritual transformations and accompanying shifts in collective identity, purpose, and meaning making."

HT is often overlooked because of a misconstrued view held by some mental health professionals that it is equivalent to PTSD. This can lead to a misunderstanding of HT, due to an exclusive focus on the individual, rather than historical causes and events.

Researchers at the Stress-response Syndromes Lab at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, use the historical contributions of the Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung to develop culturally sensitive treatments like symbolism and different myth stories to treat PTSD. Jung's psychology asserts that "the fundamental 'language' of the psyche is not words, but images...studying the trinity of myths, metaphors, and archetypes enhances clinical interventions and psychotherapy."

A combination of Western psychotherapy and Japanese culture is helpful when using psychotherapy as an effective treatment in Japan. "After the Kobe-Awaji earthquake in 1995...Japanese psychologists became acutely aware of the need to receive specialized training in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as crisis intervention." Psychotherapy is a recent practice used in Japan in which some practices of western psychotherapy are "modified to suit the Japanese client population" and forms to create a sense of cultural integration. The two main methods of treatment practices Japanese psychotherapists work with are nonverbal tasks and parallel therapy.

Art therapy

Art therapy may alleviate trauma-induced emotions, such as shame and anger. It is also likely to increase trauma survivors' sense of empowerment and has an established history of being used to treat veterans, with the American Art Therapy Association documenting its use as early as 1945. Art therapy in addition to psychotherapy offered more reduction in trauma symptoms than just psychotherapy alone.

Children's Accelerated Trauma Treatment

Children's Accelerated Trauma Treatment (CATT) is a holistic trauma-focused therapy that fuses cognitive behavioural theory with creative arts methods, whilst taking a human rights and child-centred approach to treatment.

CATT was initially created for children and adolescents at least 4 years old. However, CATT has since been used with individuals of all ages, including adults. Developed by Carlotta Raby in 1997 in London, CATT is based on empirical research and is UK NICE guidance and World Health Organisation (WHO) guidance compliant for PTSD and complex trauma treatments.

A 2021 Gaza study found CATT to be an effective treatment for symptoms of trauma in children and young people, including PTSD.

Digital interventions

Digital delivery is an expansion of telemedicine that focuses on symptom monitoring and clinical services. Modern technologies allow the usage of multiple engagements of interactions, such as smartphone usage for messaging, video calls, and completing self-report measures. There are two characteristics for providers in the digital delivery format: synchronous for real-time interaction (e.g., live video and telephone call) and asynchronous for interactions that involve a delay (e.g., messages and video recordings). Mobile technologies have improved access to self-help applications; some are assisted through artificial intelligence, such as chatbots or social robots. The integration of digital delivery has various forms to provide multiple modalities, such as platforms with both synchronous and asynchronous interactions (e.g., instant messaging with a provider).

Digital Interventions are found to improve the accessibility and clinical effectiveness of mental health interventions. The utilization of digital interventions is important because of barriers to seeking treatment, such as stigma, difficulties in scheduling, waitlist, and limited mental health resources. Digital interventions address these barriers by tailoring the intervention to the individuals' needs and the cost-efficiency of implementing the treatment. Engagement with digital interventions has shown promise in randomized controlled trials. There is some concern about how these digital intervention will translate from research settings to real world settings. Some recommendations for real-world data implementation include the amount of times a digital intervention has been accessed or opened, the total number of downloads in a specific period of time, the demographics of the users, and the number of modules completed by users.

Data suggest that it may be inefficient to use evidence-based practices for all users without understanding their symptom presentation. For PTSD, some considerations for digital intervention include which individual characteristics to use to guide treatment, how to use that data to inform the progress of treatment, and how to tailor evidence-based practices to each specific users' needs. One review examined the usage of digital interventions for PTSD symptoms in the general population and found emerging evidence supporting the effectiveness of digitally delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (iCBT) compared to other interventions (e.g., mindfulness, expressive writing, and cognitive tasks). The review also highlighted that it is important to explore the risks and potential adverse effects of completing a digital intervention.

Another review examined different randomized controlled trials (RCTs) exploring telehealth, Internet-based interventions, virtual reality exposure therapy, and mobile apps for PTSD. Internet-based interventions (IBIs) involve course-based computer programs that provide cognitive training, psychoeducation, and interactive exercises. The modules are designed to be completely weekly. In terms of IBIs, there were moderate effects when compared to passive control conditions and not for active controls; therefore, the benefits of using IBIs are unclear. Virtual Reality (VR) is computer generated, three-dimensional simulated environment. The common use for VR therapy is exposure therapy (VRET), allowing the therapist to control the pace of the exposure before having the individual confront real-world situations. VRET is different from standard VR experience because VRE is multisensory and increases the user's experiential engagement during treatment sessions. Virtual reality can help users feel more comfortable facing stressful situations in a virtual setting to learn new behaviors for real-life situations. A meta-analysis suggested that VRET is an effective treatment for PTSD and depression symptoms, with treatment benefits maintained for up to 6 months. However, these results were limited to male service members, which reduced the generalizability to women and other trauma populations. Mobile apps are software programs accessible on mobile devices and tablets. Mobile apps formats such as stand-alone or guided self-help had promising results for reducing PTSD symptoms; whereas depression symptoms were limited to small samples with no studies compared to evidence-based treatments for PTSD.

PTSD Coach

PTSD Coach is an application developed by the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) National Center for PTSD (NCPTSD) and the US Department of Defense Center for Telehealth Technology. PTSD Coach was designed for service members and veterans and as a public health resource for any individuals impacted by trauma. Many studies support the feasibility and effectiveness of PTSD Coach as a mobile health intervention for self-management care of PTSD symptoms. One study found that most users accessed the app to manage symptoms through the use of a coping tool (e.g., cognitive restructuring). It was found that PTSD Coach has been positively received by the general public, who found the app helpful in reducing momentary distress. The broad dissemination to the general public for PTSD Coach has continued to be supported with an average usage of three times across three separate days with a duration of 18 minutes of use. One study compared the mobile app version of PTSD Coach to the web-based version, PTSD Coach Online, and found lower attrition rates on the mobile app compared to the web-based version. The use of human support yielded better outcomes than self-management alone, as participants were guided through structured weekly sessions. Another study also highlighted that clinician support increases the effectiveness of PTSD Coach for mobile app engagement. Because of the increased access to smartphones, one study examined the global use of PTSD Coach in Australia, Canada, The Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, and Denmark. There is potential for PTSD Coach to address a global unmet need for care; however, there is still much work for disseminating PTSD Coach for areas where resources are nonexistent. For community trauma survivors, PTSD Coach was found to be a feasible intervention for learning about PTSD, self-management symptoms, and symptom monitoring. The examination of PTSD Coach for efficacy was not clear compared to the waitlist condition; however, the study condition using PTSD Coach had a significant reduction in symptoms, and the waitlist did not. Therefore, it is encouraged to continue to explore the efficacy of PTSD Coach for community trauma survivors.

Digital Attrition

Because digital interventions require active user engagement, it is important to understand what facilitates digital engagement versus digital intervention attrition. Many studies highlighted the impact of digital engagement on users in PTSD Coach. Some theories to highlight digital engagements are the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). TAM is technology acceptance through an individual's perspective of ease of use, usefulness, and subjective norms. UTAUT highlighted the behavioral intention of using digital interventions through a user's effort expectancy, performance expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, and habit. The importance of an effective digital intervention is to examine the user's experience and flow of engaging with technology to create a balance of challenges and content. There are other factors, such as Internet anxiety, that moderated the relationship between digital intervention usage with recommendations of providing information about data security to help users feel supported.

Cannabinoids

Recent research has shown that cannabis is beneficial for PTSD Treatment according to the VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) in those who receive doses with higher levels in THC. According to Mallory Lofl, a volunteer assistant professor of psychiatry at the UC San Diego School of Medicine, one of the biggest takeaways from this study is that veterans with PTSD can use cannabis at self-managed doses, at least in the short term, and not experience a plethora of side effects or a worsening of symptoms. Currently, 37 states, four territories, and the District of Columbia allow the use of cannabis for medical purposes. Two studies that have been published recently showed two different mechanisms that allow cannabinoids to help with PTSD. One showcased cannabis's effect in the amygdala — a part of the brain associated with fear responses to threats — by reducing activity in that region. The second study suggests that cannabinoids could aid in blocking traumatic memories.

Psychedelic assisted psychotherapy

Psychedelic therapy is the use of psychedelic substances such as MDMA, psilocybin, LSD, and ayahuasca to treat mental illnesses. Most of these substances are controlled substances in most countries and are not legally prescribed. They are mostly used in clinical trials. The way of administering psychedelic drugs is different from most other medical drugs. Psychedelic drugs are usually given in a single sessions or a few sessions after which the patient wears eyeshades and listens to music so that they can focus on the psychedelic experience. The therapeutic team is available in case of any distress or anxiety.

Psychotherapy itself often does not cause complete recovery in PTSD patients. The investigation of psychedelic drugs as an alternative to antidepressants and psychotherapy is becoming popular and there are many clinical trials being run on this.

The advantage of using psychedelic drugs is that many of these drugs are not physically addictive, unlike drugs like nicotine. The disadvantages of using psychedelics include the risk of a "bad trip" causing the patient to feel unsafe and causing long-term negative impact on their mental state. Some patients have also reported flashbacks upon taking psychedelics thus decreasing their overall well-being by bringing back the memories causing PTSD.

MDMA

See also: MDMA-assisted psychotherapy and MDMA § ResearchIn 2018, the US Food and Drug and Drug Administration granted "Breakthrough Therapy" designation for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy trials. There is weak evidence MDMA might improve PTSD symptoms, with possible adverse effects including nausea and jaw clenching.

The use of MDMA for treating PTSD is currently undergoing clinical trials and not yet approved by the FDA. However, MDMA has potential to be a promising treatment for PTSD because it decreases fear, increases wellbeing, increases sociability, increases trust, and creates and alert state of consciousness. This helps patients them more easily process their memories and changes their views on life and purpose. Only 2-3 sessions of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy have shown positive results for reducing symptoms of PTSD. There is also evidence that treatments using classical psychedelics like psilocybin and LSD must only be considered after the patient has tried MDMA-assisted therapy. This is because MDMA only mildly alters the patient's emotional state and self-perception while classical psychedelics may alter them much more.

Psilocybin

Some studies have shown that mice overcome fear after being given psilocybin. This is because psilocybin stimulates the growth of neurons in the hippocampus which is the area of the brain responsible for memory and emotion. There has also been success in using psilocybin on human patients with PTSD.

Ketamine

Ketamine has been shown to rapidly decrease PTSD symptoms by altering memory processes such as increases in fear extinction. Ketamine therapy in combination with exposure therapy has promising effects for the treatment of PTSD. A systematic review of the literature found that ketamine therapy significantly reduced PTSD scores at the time of last follow-up while also significantly increasing the time to relapse versus control therapy.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines are not recommended for the treatment of PTSD due to a lack of evidence of benefit and risk of worsening PTSD symptoms. Benzodiazepines are a group of anti-anxiety medications that make people feel calm, relaxed, or sleepy. They are recommended for short-term treatment of severe anxiety, panic, or insomnia. Some authors believe that the use of benzodiazepines is contraindicated for acute stress, as this group of drugs can cause dissociation. Nevertheless, some people use benzodiazepines for short-term anxiety and insomnia. For those who already have PTSD, benzodiazepines may worsen and prolong the course of illness, by worsening psychotherapy outcomes, and causing or exacerbating aggression, depression (including suicidality), and substance use. The National Center for PTSD has claimed that if benzodiazepines are used by PTSD patients, patients may be unable to learn how to manage stress which makes it harder to recover. Effective treatments for PTSD, like talk therapy, help stop avoiding distressing situations and memories. Drawbacks include the risk of developing a benzodiazepine dependence, tolerance (i.e., short-term benefits wearing off with time), and withdrawal syndrome; additionally, individuals with PTSD (even those without a history of alcohol or drug misuse) are at an increased risk of abusing benzodiazepines.

Topiramate

Topiramate is an anti-epileptic section of medications used to modulate glutamate transmission and could result in PTSD symptom reduction. However, the side effects of topiramate are greater than SSRI antidepressants so it is generally not recommended since it is not uncommon for patients to experience side effects such as cognitive dulling. Cognitive dulling refers to a form of mental fatigue that leads to difficulty concentrating, decreased productivity, and a decline in emotional and mental health, according to Jennifer Bahrman, assistant professor in the Louis A. Faillace, MD, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

Prazosin

Prazosin, an alpha-adrenoceptor antagonist, is often prescribed, particularly for sleep-related symptoms. Early studies have shown evidence of efficacy, though a recent large trial did not show a statistically significant difference between prazosin and placebo.

Antipsychotic medications

Antipsychotic medications have also been prescribed to treat PTSD, though clinical trials have not yielded consistent evidence for their efficacy.

Stellate ganglion block

A promising invasive treatment for PTSD was proposed in 2008. The treatment is known as SGB (stellate ganglion block), which can also be referred to as CSB (cervical sympathetic blockade). The stellate ganglion is treated with an injection of local anesthetic (numbing medicine) to block the sympathetic nerves located on either side of the voice box in the neck.

The block targets these sympathetic nerves because they control a person's fight or flight response. The subjects of SGB have mixed reviews as patients saw improvements in depression and anxiety but not in pain. There is no relevant literature or evidence-based guidelines regarding the clinical effectiveness of SGB for the treatment of depression or anxiety. Overall, considering the limitations mentioned, the findings and recommendations summarized in this report need to be interpreted with caution. While SGB has helped certain symptoms of PTSD, it is a new treatment that should be looked at with caution and skepticism. It is not a cure for PTSD.

Nepicastat

Moreira-Rodrigues et al. demonstrated that mice lacking epinephrine exhibit reduced contextual memory after fear conditioning. In addition, in PTSD epinephrine enhances traumatic-contextual memory. Nepicastat is a drug that inhibits dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH), which is the enzyme that is responsible for the conversion of dopamine to norepinephrine. Studies have shown that nepicastat effectively reduces norepinephrine in both peripheral and central tissues in rats and dogs. Nepicastat also unregulated the transcription Npas4 and Bdnf genes in the hippocampus, potentially contributing to neuronal regulation and the attenuation of traumatic contextual memories. Although no DBH inhibitor has received marketing approval due to poor DBH selectivity, low potency and side effects, DBH gene silencing may be an alternative for patients with heightened sympathetic activity. Some studies, however have shown that nepicastat is well-tolerated in healthy adults and significant no differences in adverse events were observed. Given that nepicastat treatment has been proven to be effective in reducing signs in PTSD mice model with elevated catecholamine levels, it could be a promising treatment option for humans with PTSD characterized by increased catecholamine plasma levels.

Sotalol

It has been shown that reduction of sympathetic autonomic overshooting in PTSD patients may be achieved through inhibition of β-Adrenergic receptor activity. Propranolol, a peripheral and central β-Adrenergic antagonist is effective on preventing the onset and progression of PTSD symptoms in humans however its beneficial effects are undermined by unwanted side effects like gastrointestinal disturbances, bradycardia, fatigue, sleep disorders and memory deficits. Sotalol is a peripherally acting β-Adrenergic receptor antagonist which has been proven to decrease traumatic contextual memories, anxiety-like behaviours and plasma catecholamines in animals and it is thought to have less side effects than centrally acting propranolol. It has also been shown that Sotalol decreases Nr4a1 mRNA transcripts in the hippocampus which is important for contextual fear memory formation and consolidation. Sotalol is currently used in patients with ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias, despite unwanted pro-arrhythmic effects. Treatment of PTSD with sotalol may be a possibility if effective when using smaller doses.

Recommendations

A number of major health bodies have developed lists of treatment recommendations. These include:

- American Psychological Association

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs

- The UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- Australian Psychological Society

- Australia's National Health and Medical Research Council

See also

References

- "What Is PTSD?". www.psychiatry.org. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) | Anxiety and Depression Association of America, ADAA". adaa.org. Retrieved 2022-06-09.

- Assmann N, Fassbinder E, Schaich A, Lee CW, Boterhoven de Haan K, Rijkeboer M, et al. (August 2021). "Differential Effects of Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders on Treatment Outcome in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder from Childhood Trauma". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 10 (16): 3708. doi:10.3390/jcm10163708. PMC 8397108. PMID 34442005.

- ^ Lowery-Gionta EG, May MD, Taylor RM, Bergman EM, Etuma MT, Jeong IH, et al. (September 2019). "Modeling trauma to develop treatments for posttraumatic stress". Translational Issues in Psychological Science. 5 (3): 243–275. doi:10.1037/tps0000199.

- ^ Liu H, Petukhova MV, Sampson NA, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Andrade LH, et al. (March 2017). "Association of DSM-IV Posttraumatic Stress Disorder With Traumatic Experience Type and History in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys". JAMA Psychiatry. 74 (3): 270–281. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3783. hdl:10230/32386. PMC 5441566. PMID 28055082.

- ^ Forman-Hoffman V, Cook Middleton J, Feltner C, Gaynes BN, Palmieri Weber R, Bann C, et al. (2018-05-17). Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments for Adults With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review Update (Report). doi:10.23970/ahrqepccer207.

- "PTSD Facts & Treatment | Anxiety and Depression Association of America, ADAA". adaa.org. Retrieved 2022-06-09.

- Bisson JI, Cosgrove S, Lewis C, Robert NP (November 2015). "Post-traumatic stress disorder". BMJ. 351: h6161. doi:10.1136/bmj.h6161. PMC 4663500. PMID 26611143.

- U.S. Dep't of Veterans Affs. & Dep't of Def., VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder, ver. 3, p. 46, 2017.

- Brent DA, Kolko DJ (February 1998). "Psychotherapy: definitions, mechanisms of action, and relationship to etiological models". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 26 (1): 17–25. doi:10.1023/a:1022678622119. PMID 9566543. S2CID 27541174.

- "CBT for PTSD: How It Works, Examples & Effectiveness". Choosing Therapy. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

- ^ "Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Treatment of PTSD". American Psychological Association.

- ^ "Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Primer for Child Welfare Professionals - Child Welfare Information Gateway". www.childwelfare.gov. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- ^ Ennis N, Shorer S, Shoval-Zuckerman Y, Freedman S, Monson CM, Dekel R (April 2020). "Treating posttraumatic stress disorder across cultures: A systematic review of cultural adaptations of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapies". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 76 (4): 587–611. doi:10.1002/jclp.22909. PMID 31851380. S2CID 209409358.

- Klein EJ, Lopez WD (June 2022). "Trauma and Police Violence: Issues and Implications for Mental Health Professionals". Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 46 (2): 212–220. doi:10.1007/s11013-020-09707-0. PMID 33492564. S2CID 254786525.

- Metzger IW, Anderson RE, Are F, Ritchwood T (February 2021). "Healing Interpersonal and Racial Trauma: Integrating Racial Socialization Into Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for African American Youth". Child Maltreatment. 26 (1): 17–27. doi:10.1177/1077559520921457. PMC 8807349. PMID 32367729.

- Patel ZS, Casline EP, Vera C, Ramirez V, Jensen-Doss A (September 2022). "Unaccompanied migrant children in the United States: Implementation and effectiveness of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy". Psychological Trauma. Advance online publication (Suppl 2): S389–S399. doi:10.1037/tra0001361. PMID 36107712. S2CID 252281570.

- Zemestani M, Mohammed AF, Ismail AA, Vujanovic AA (July 2022). "A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial of a Novel, Culturally Adapted, Trauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention for War-Related PTSD in Iraqi Women". Behavior Therapy. 53 (4): 656–672. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2022.01.009. PMID 35697429. S2CID 246606057.

- Kleim B, Grey N, Wild J, Nussbeck FW, Stott R, Hackmann A, et al. (June 2013). "Cognitive change predicts symptom reduction with cognitive therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 81 (3): 383–393. doi:10.1037/a0031290. PMC 3665307. PMID 23276122.

- Forbes D, Creamer M, Bisson JI, Cohen JA, Crow BE, Foa EB, et al. (October 2010). "A guide to guidelines for the treatment of PTSD and related conditions". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 23 (5): 537–552. doi:10.1002/jts.20565. PMID 20839310.

- ^ Evidence-based Psychological Interventions in the Treatment of Mental Disorders. Australian Psychological Society. 2018.

- Ehlers A, Clark DM (April 2000). "A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 38 (4): 319–345. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0. PMID 10761279.

- Ehlers A, Wild J (2015). "Cognitive Therapy for PTSD: Updating Memories and Meanings of Trauma". In Schnyder U, Cloitre M (eds.). Evidence Based Treatments for Trauma-Related Psychological Disorders. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 161–187. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-07109-1_9. ISBN 978-3-319-07108-4.

- Ehlers A, Clark DM, Hackmann A, McManus F, Fennell M (April 2005). "Cognitive therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: development and evaluation". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 43 (4): 413–431. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2004.03.006. PMID 15701354.

- "What Is Imagery Rehearsal Therapy (IRT)?". Psych Central. 2021-05-21. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

- "Cognitive Therapy (CT)". American Psychological Association.

- ^ Sharpless BA, Barber JP (February 2011). "A Clinician's Guide to PTSD Treatments for Returning Veterans". Professional Psychology, Research and Practice. 42 (1): 8–15. doi:10.1037/a0022351. PMC 3070301. PMID 21475611.

- "Emotional processing theory". APA Dictionary of Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. n.d. Retrieved 2020-09-06.

- Foa EB (December 2011). "Prolonged exposure therapy: past, present, and future". Depression and Anxiety. 28 (12): 1043–1047. doi:10.1002/da.20907. PMID 22134957. S2CID 28115857.

- Rupp C, Doebler P, Ehring T, Vossbeck-Elsebusch AN (May 2017). "Emotional Processing Theory Put to Test: A Meta-Analysis on the Association Between Process and Outcome Measures in Exposure Therapy". Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 24 (3): 697–711. doi:10.1002/cpp.2039. PMID 27561691.

- Courtois CA, Sonis J, Brown LS, Cook J, Fairbank JA, Friedman M, et al. (2017). "Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

- ^ "Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT)".

- "Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD - PTSD". National Center for PTSD. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ "Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy".

- ^ Stickgold R (January 2002). "EMDR: a putative neurobiological mechanism of action". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 58 (1): 61–75. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.124.5340. doi:10.1002/jclp.1129. PMID 11748597.

- "Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) for PTSD - PTSD". National Center for PTSD. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- "Defusing PTS: Complementary and Alternative Medicine for Post-Traumatic Stress". www.moaa.org. 2017-06-07. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- Thyer BA, Pignotti MG (2015). "Chapter 4: Pseudoscience in Treating Adults Who Experienced Trauma". Science and Pseudoscience in Social Work Practice. Springer. pp. 106, 146. doi:10.1891/9780826177698.0004. ISBN 9780826177681.

- ^ "Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET)". American Psychological Association.

- Smid GE, Kleber RJ, de la Rie SM, Bos JB, Gersons BP, Boelen PA (2015). "Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy for Traumatic Grief (BEP-TG): toward integrated treatment of symptoms related to traumatic loss". European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 6: 27324. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v6.27324. PMC 4495623. PMID 26154434.

- "Information". Traumabehandeling. March 31, 2017.

- ^ "Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy (BEP)". American Psychological Association.

- ^ "APA Dictionary of Psychology". dictionary.apa.org. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- "Treating Borderline Personality Disorder | NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness". www.nami.org. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- Greenberg LS. "Emotion-focused therapy". APA PsycNet. American Psychological Association. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- ^ Greenberg LS (January 2010). "Emotion-Focused Therapy: A Clinical Synthesis". FOCUS. 8 (1): 32–42. doi:10.1176/foc.8.1.foc32.

- ^ Blow AJ, Curtis AF, Wittenborn AK, Gorman L (September 2015). "Relationship Problems and Military Related PTSD: The Case for Using Emotionally Focused Therapy for Couples". Contemporary Family Therapy. 37 (3): 261–270. doi:10.1007/s10591-015-9345-7. S2CID 142097337.

- ^ "Therapy". MCT Institute. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

- Wells A, Matthews G (November 1996). "Modelling cognition in emotional disorder: the S-REF model". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 34 (11–12): 881–888. doi:10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00050-2. PMID 8990539.

- Nordahl HM, Halvorsen JØ, Hjemdal O, Ternava MR, Wells A (January 2018). "Metacognitive therapy vs. eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for posttraumatic stress disorder: study protocol for a randomized superiority trial". Trials. 19 (1): 16. doi:10.1186/s13063-017-2404-7. PMC 5759867. PMID 29310718.

- Boyd JE, Lanius RA, McKinnon MC (January 2018). "Mindfulness-based treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the treatment literature and neurobiological evidence". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 43 (1): 7–25. doi:10.1503/jpn.170021. PMC 5747539. PMID 29252162.

- "What Is Exposure Therapy?".

- ""Virtual Vietnam" PTSD Therapy System (1997-1998)". Jarrell Pair. 2012-02-21. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

- Rizzo AA, Rothbaum BO, Graap K (2007). "Virtual reality applications for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder.". In Figley CR, Nash WP (eds.). Combat stress injury: Theory, research and management. New York: Routledge. pp. 420–425.

- InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). October 4, 2018 – via www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- Pacheco D (January 8, 2021). "How post-traumatic stress disorder affects sleep". Sleep Foundation.

- Rolle N (May 2020). "Sleep hygiene" (PDF). American Occupational Therapy Association.

- ^ "Role of occupational therapy with post-traumatic stress disorder" (PDF). American Occupational Therapy Association. 2015.

- "Occupational Therapy's Role with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder" (PDF). American Occupational Therapy Association. 2015.

- Rogers CM, Mallinson T, Peppers D (2014-07-01). "High-intensity sports for posttraumatic stress disorder and depression: feasibility study of ocean therapy with veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom". The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 68 (4): 395–404. doi:10.5014/ajot.2014.011221. PMID 25005502.

- Grant AM (September 2009). "Positive psychology coaching: putting the science of happiness to work for your clients, by R. Biswas-Diener and B. Dean". The Journal of Positive Psychology. 4 (5): 426–429. doi:10.1080/17439760902992498. ISSN 1743-9760. S2CID 147594898.

- "PsycNET". psycnet.apa.org.

- "APA PsycNet". psycnet.apa.org. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- "Stress Inoculation Training" (PDF). VA PTSD.

- "Biomedical Therapy". American Psychological Association. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- ^ "Pollock BG, Gerretsen P, Balakumar T, Semla TP (2017). "Chapter 64: Psychoactive Drug Therapy.". Hazzard's Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- "VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Disorder" (PDF). U.S. Dep't of Veterans Affs. & Dep't of Def. 2017. p. 51.

- "Second-line therapies". National Cancer Institute Dictionaries. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- "The Best Medications Used to Treat PTSD (Evidence-Based)". Goodrx.

- Giller EL, ed. (1990). Biological Assessment and Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.

- Alexander W (January 2012). "Pharmacotherapy for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder In Combat Veterans: Focus on Antidepressants and Atypical Antipsychotic Agents". P & T. 37 (1): 32–38. PMC 3278188. PMID 22346334.

- Davidson JR (1997). "Biological therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder: an overview". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 Suppl 9 (Suppl 9): 29–32. PMID 9329449.

- ^ Fookes C. "Monoamine oxidase inhibitors". Drugs.com. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- "Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 1980-01-01. Retrieved 2022-06-09.

- ^ "NCI Dictionaries - NCI". www.cancer.gov. 2015-05-15. Retrieved 2022-06-09.

- "Types of Complementary and Alternative Medicine". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 2019-11-19. Retrieved 2022-06-09.

- Niles BL, Mori DL, Polizzi C, Pless Kaiser A, Weinstein ES, Gershkovich M, et al. (September 2018). "A systematic review of randomized trials of mind-body interventions for PTSD". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 74 (9): 1485–1508. doi:10.1002/jclp.22634. PMC 6508087. PMID 29745422.

- "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)". HelpGuide.org. 2 November 2018. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

- ^ Davis LW, Schmid AA, Daggy JK, Yang Z, O'Connor CE, Schalk N, et al. (November 2020). "Symptoms improve after a yoga program designed for PTSD in a randomized controlled trial with veterans and civilians". Psychological Trauma. 12 (8): 904–912. doi:10.1037/tra0000564. hdl:1805/28115. PMID 32309986. S2CID 216030711. ProQuest 2392062761.

- ^ van der Kolk BA, Stone L, West J, Rhodes A, Emerson D, Suvak M, et al. (June 2014). "Yoga as an adjunctive treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 75 (6): e559–e565. doi:10.4088/JCP.13m08561. PMID 25004196. S2CID 2382770.

- "Acupuncture". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- ^ Ding N, Li L, Song K, Huang A, Zhang H (June 2020). "Efficacy and safety of acupuncture in treating post-traumatic stress disorder: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis". Medicine. 99 (26): e20700. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000020700. PMC 7328930. PMID 32590744.

- "How Acupuncture has helped some PTSD Sufferers – PTSD UK". Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- Kingsley G (2007). "Contemporary group treatment of combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder". The Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry. 35 (1): 51–69. doi:10.1521/jaap.2007.35.1.51. PMID 17480188. ProQuest 198124994.

- ^ Barrera TL, Mott JM, Hofstein RF, Teng EJ (February 2013). "A meta-analytic review of exposure in group cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder". Clinical Psychology Review. 33 (1): 24–32. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.005. PMID 23123568.

- Charry-Sánchez JD, Pradilla I, Talero-Gutiérrez C (August 2018). "Animal-assisted therapy in adults: A systematic review". Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 32: 169–180. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.06.011. PMID 30057046. S2CID 51864317.

- Marcus DA (April 2013). "The science behind animal-assisted therapy". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 17 (4): 322. doi:10.1007/s11916-013-0322-2. PMID 23430707. S2CID 10553496.

- "Therapy Animals Supporting Kids (TASK) Program Manual". American Humane. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

- ^ O'Haire ME, Rodriguez KE (February 2018). "Preliminary efficacy of service dogs as a complementary treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in military members and veterans". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 86 (2): 179–188. doi:10.1037/ccp0000267. PMC 5788288. PMID 29369663. ProQuest 1990860953.