| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Rotations and reflections in two dimensions" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In Euclidean geometry, two-dimensional rotations and reflections are two kinds of Euclidean plane isometries which are related to one another.

Process

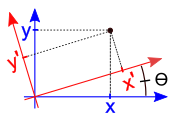

A rotation in the plane can be formed by composing a pair of reflections. First reflect a point P to its image P′ on the other side of line L1. Then reflect P′ to its image P′′ on the other side of line L2. If lines L1 and L2 make an angle θ with one another, then points P and P′′ will make an angle 2θ around point O, the intersection of L1 and L2. I.e., angle ∠ POP′′ will measure 2θ.

A pair of rotations about the same point O will be equivalent to another rotation about point O. On the other hand, the composition of a reflection and a rotation, or of a rotation and a reflection (composition is not commutative), will be equivalent to a reflection.

Mathematical expression

The statements above can be expressed more mathematically. Let a rotation about the origin O by an angle θ be denoted as Rot(θ). Let a reflection about a line L through the origin which makes an angle θ with the x-axis be denoted as Ref(θ). Let these rotations and reflections operate on all points on the plane, and let these points be represented by position vectors. Then a rotation can be represented as a matrix,

and likewise for a reflection,

With these definitions of coordinate rotation and reflection, the following four identities hold:

Proof

These equations can be proved through straightforward matrix multiplication and application of trigonometric identities, specifically the sum and difference identities.

The set of all reflections in lines through the origin and rotations about the origin, together with the operation of composition of reflections and rotations, forms a group. The group has an identity: Rot(0). Every rotation Rot(φ) has an inverse Rot(−φ). Every reflection Ref(θ) is its own inverse. Composition has closure and is associative, since matrix multiplication is associative.

Notice that both Ref(θ) and Rot(θ) have been represented with orthogonal matrices. These matrices all have a determinant whose absolute value is unity. Rotation matrices have a determinant of +1, and reflection matrices have a determinant of −1.

The set of all orthogonal two-dimensional matrices together with matrix multiplication form the orthogonal group: O(2).

The following table gives examples of rotation and reflection matrix :

| Type | angle θ | matrix |

|---|---|---|

| Rotation | 0° | |

| Rotation | 45° | |

| Rotation | 90° | |

| Rotation | 180° | |

| Reflection | 0° | |

| Reflection | 45° | |

| Reflection | 90° | |

| Reflection | -45° |

Rotation of axes

This section is an excerpt from Rotation of axes in two dimensions.

See also

- 2D computer graphics#Rotation

- Cartan–Dieudonné theorem

- Clockwise

- Dihedral group

- Euclidean plane isometry

- Euclidean symmetries

- Instant centre of rotation

- Orthogonal group

- Rotation group SO(3) – 3 dimensions

References

- Protter & Morrey (1970, p. 320)

- Anton (1987, p. 231)

- Burden & Faires (1993, p. 532)

- Anton (1987, p. 247)

- Beauregard & Fraleigh (1973, p. 266)

Sources

- Anton, Howard (1987), Elementary Linear Algebra (5th ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-84819-0

- Beauregard, Raymond A.; Fraleigh, John B. (1973), A First Course In Linear Algebra: with Optional Introduction to Groups, Rings, and Fields, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., ISBN 0-395-14017-X

- Burden, Richard L.; Faires, J. Douglas (1993), Numerical Analysis (5th ed.), Boston: Prindle, Weber and Schmidt, ISBN 0-534-93219-3

- Protter, Murray H.; Morrey, Charles B. Jr. (1970), College Calculus with Analytic Geometry (2nd ed.), Reading: Addison-Wesley, LCCN 76087042

45°

45°

to an x′y′-Cartesian coordinate system

to an x′y′-Cartesian coordinate system