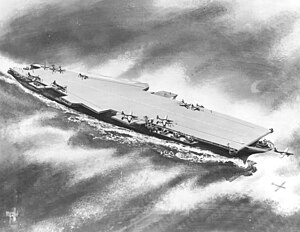

Artist's rendering of the proposed USS United States handling McDonnell FH-1 Phantom fighters and Lockheed P2V-3C Neptune twin-engine bombers Artist's rendering of the proposed USS United States handling McDonnell FH-1 Phantom fighters and Lockheed P2V-3C Neptune twin-engine bombers

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name | United States class |

| Builders | Newport News Shipbuilding |

| Preceded by | Midway class |

| Succeeded by | Forrestal class |

| Planned | 5 |

| Completed | 0 |

| History | |

| Name | United States |

| Namesake | United States |

| Ordered | 29 July 1948 |

| Builder | Newport News Drydock and Shipbuilding |

| Laid down | 18 April 1949 |

| Fate | Cancelled 23 April 1949 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Aircraft carrier |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 1,090 feet (332 m) overall, 1,030 feet (314 m) waterline, 1,088 feet (332 m) flight deck |

| Beam | 125 feet (38 m) waterline (molded), 190 feet (58 m) flight deck |

| Draft | 37 feet (11 m) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament | 8 × 5 in (127 mm) / 54 caliber guns in single mounts, 16 × 76 mm / 70 caliber guns in eight twin mounts, 20 × Oerlikon 20 mm cannons in ten twin mounts |

| Aircraft carried | 12 to 18 heavy bombers and 54 jet engined fighter aircraft |

USS United States (CVA-58) was to be the lead ship of a new design of aircraft carrier. On 29 July 1948, President Harry Truman approved construction of five "supercarriers", for which funds had been provided in the Naval Appropriations Act of 1949. The keel of the first of the five planned postwar carriers was laid down on 18 April 1949 at Newport News Drydock and Shipbuilding. The program was canceled in 1949, United States was not completed, and the other four planned carriers were never built.

Design

The chief proponent for the new large carrier was Admiral Marc Mitscher. He wanted a carrier that would be able to handle the most effective weapons of the day. Early design discussions centered around developing a carrier that would be able to support combat missions using the new jet aircraft. These were faster, larger and significantly heavier than the aircraft which the Essex- and Midway-class carriers were handling at the end of the Second World War. It was thought that the aircraft carried would have to have longer range to allow the carrier to operate farther away from the target. The deck would have to be able to handle the weight of the heavy jet aircraft landing on the deck. The implication was that the ship's strength deck would have to be the flight deck rather than the hangar deck, as had been the case for earlier U.S. carriers. Armoring the flight deck would mean the ship would have a greater tendency to roll in rough seas, as a greater part of the ship's weight would be high above the waterline.

Based on the size of the aircraft that the new ship was to carry, the design of the carrier was to be flush decked, meaning that the ship would have no island control structure. This would be done to create more space for large winged aircraft. The flush-deck design carried with it two major concerns. The first concern was over how smoke from the power plants would be diverted from the flight deck. This had been a major issue with the US Navy's first aircraft carrier, USS Langley, in the 1920s when carrier development was first underway. The second concern was the placement of early warning radar equipment to allow the ship to detect incoming attacks. One solution was for a command ship to be close by which would carry the commander of the task force and the early detection radar. The command ship would radio electronic information and orders from its command center over to the carrier. This command ship role was termed a 'pilotfish' and the USS Northampton (CLC-1) would be built in part to fulfill this role. A second solution was for the ship to carry aircraft that could fly the early warning radar. These would fly overhead and detect approaching aircraft. In truth, the ship as designed would not be able to safely operate by itself, but would need to operate in conjunction with traditional fleet carriers as a complementary bomber-carrier. In fact, the ship was being designed on the basis of the aircraft that it was thought it would carry, and these were based on projections of what aircraft would be in existence in the period 1952 to 1960.

Discussions included debate on the aircraft carrier's mission. One view was that it would carry a group of large bombers that would be secured to the flight deck, with no hangar for these aircraft, as they would be too large to move up and down in an elevator. Though they would be built to carry large nuclear weapons, the total amount of space used for munition storage would be reduced as multiple strikes would not be likely. A small hangar deck would be available for a limited fighter escort and a small magazine for a small number of heavy nuclear weapons. Another plan was that it could be built with conventional attack capability with a large hangar deck for a large air wing and a large magazine. The nuclear attack supporters won in the initial design stage, but the design was modified to carry more fighters. The flush-deck United States was designed to launch and recover the 100,000 pound (45 t) aircraft required to carry early-model nuclear weapons, which weighed as much as five tons. The ship would have no permanently raised island or command tower structure. It would be equipped with four aircraft elevators located at the deck edges to avoid decreasing the structural strength of the flight deck. Four catapults would be used to launch aircraft, with two at the bow and two others on the outer edge of the deck staggered back. The carrier was designed so that it could land aircraft at the rear while at the same time launching aircraft from the catapults at the bow and forward area simultaneously. The construction cost of the new ship was estimated at US$189 million (equivalent to US$1.92 billion in 2023).

Proposed operations

USS United States was designed with the primary mission of carrying long-range bomber aircraft that could carry a heavy enough load to undertake nuclear bombardment missions. It would also carry long range escort fighters that would fly along and protect its bombers. The ship could also take on other roles, such as providing air support for amphibious forces and to conduct sea control operations, but it was primarily to be a "bomber carrier". It was thought it would operate in a task force coupled with traditional attack carriers, which would provide the air cover for the task force. That mission was virtually certain to make the ship a target of inter-service rivalries over missions and funding. The United States Air Force viewed United States as a challenge to their monopoly on strategic nuclear weapons delivery.

Keel laying; cancellation

Looking to cut the military budget and accepting without question the Air Force argument on nuclear deterrence by means of large, long-range bombers, Secretary of Defense Louis A. Johnson announced the cancellation of United States on 23 April 1949, five days after the ship's keel was laid. Secretary of the Navy John Sullivan immediately resigned, and Congress held an inquiry into the manner and wisdom of Johnson's decision. In the subsequent "Revolt of the Admirals", the Navy was unable to advance its case that large carriers would be essential to national defense.

Soon afterward, Johnson and Francis P. Matthews, the man he advanced to be the new Secretary of the Navy, set about punishing those officers that let their opposition be known. Navy Admiral Louis Denfeld was forced to resign as Chief of Naval Operations, and a number of other admirals and lesser ranks were punished. The invasion of South Korea six months later resulted in an immediate need for a strong naval presence, and Matthews' position as Secretary of the Navy and Johnson's position as Secretary of Defense crumbled, both ultimately resigning.

Soon after she was canceled, the aircraft carrier's keel was dismantled. This freed up the drydock, allowing crews to immediately begin construction on the ocean liner SS United States (name coincidental).

The Navy soon found a means to carry nuclear weapons at sea, placed aboard the aircraft carrier USS Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1950. Thus the question of which service would have primary responsibility for strategic nuclear strikes was not answered with Johnson's cancellation of USS United States.

See also

References

- ^ Elward 2011, pp. 6–8

- ^ DANFS United States 2016

- ^ Naval Historical Center 2001

- ^ Pike 2000

- ^ Polmar 2008, pp. 47, 474

- Friedman 1983, p. 230.

- Cracknell 1972, p. 56: "The main armor carried on Enterprise is the heavy armored flight deck. This was to prove a significant factor in the catastrophic fire and explosions that occurred on Enterprise's flight deck in 1969. The US Navy learned its lesson the hard way during World War II when all its carriers had only armored hangar decks. All attack carriers built since the Midway class have had armored flight decks."

- ^ Friedman 1983, p. 244.

- Friedman 1983, pp. 241–243.

- Friedman 1984, p. 340.

- Friedman 1983, p. 241.

- Gustafson 1949, p. 115.

- Friedman 1983, p. 188.

- Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 30 November 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- Friedman 1983, p. 242.

- Lewis 1998, pp. 32–35.

- McFarland 1980, p. 61.

- Ujifusa, Steven (2013). A Man and His Ship: America's Greatest Naval Architect and His Quest to Build the S.S. United States. Simon & Schuster. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-1451645095.

Bibliography

- Cracknell, W. H. (1972). USS Enterprise (CVAN 65) Nuclear Attack Carrier. Warship Profile. Vol. 15. Profile Publications.

- Elward, Brad (2011). Nimitz-Class Aircraft Carriers. Osprey Publishing. pp. 6–8. ISBN 978-1-84908-971-5.

- Friedman, Norman (1983). U.S. Aircraft Carriers: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-739-5.

- Friedman, Norman (1984), U.S. Cruisers: an illustrated design history, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 0-87021-718-6, OCLC 10949320

- Gustafson, Phil (January 1949). "Why the Navy Wants Supercarriers". Popular Science. pp. 114–120.

- Lewis, Andrew L. (April 1998). The Revolt of the Admirals (Thesis). Air Command and Staff College, Maxwell Air Force Base – via Federation of American Scientists.

- McFarland, Keith (1980). "The 1949 Revolt of the Admirals" (PDF). Parameters: Journal of the U.S. Army War College Quarterly. XI (2). U.S. Army War College: 53–63. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- Naval Historical Center (8 September 2001). "USS United States (CVA-58)". Online Library of Selected Images: U.S. Navy Ships. U.S. Navy, Naval Historical Command. Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2021 – via HyperWar Foundation.

- Pike, John (3 January 2000). "CVA 58 United States". FAS Military Analysis Network. Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- Polmar, Norman (2008). Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events: Vol. II, 1946-2006. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 978-157488-665-8.

- "United States (frigate), 1797–1865". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. 22 February 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

Further reading

- Zichek, Jared A. (2009). The Incredible Attack Aircraft of the USS United States, 1948–1949. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7643-3229-6.