The Upper Backward Caste is a term used to describe the middle castes in Bihar, whose social and ritual status was not very low and which have traditionally been involved in the agricultural and animal husbandry related activities in the past. They have also been involved in low scale trade to some extent. The Koeri, Kurmi, Yadav, and Bania are categorised as the upper-backwards amongst the Other Backward Class group; while the various other caste groups which constitute the OBC, a group comprising 51% of the population of state of Bihar, have been classified as lower backwards. The upper-backwards, also called upper OBC, represent approximately 20.3% of the population of Bihar. These agricultural caste were the biggest beneficiaries of the land reform drive which was undertaken in the 1950s in the state and they strengthened their economic position by gaining a significant portion of excess land under the ceiling laws, which prohibited the ownership of land above a certain ceiling.

The term 'upper OBC' technically corresponds to the castes included in the Annexure-II of the Mungeri Lal commission's report on the backward classes of Bihar, while the lower OBC corresponds to the Extremely Backward Classes that were included in the Annexure-I of that particular report.

History

By the early 1900s, the peasant communities like Kushwaha, Kurmi, and Yadav who were numerically powerful in the Gangetic plains and had amassed rural wealth and power due to their knowledge of local agricultural practices, started laying claim on Kshatriya status. These peasant communities included some of the small landholders and powerful tenants who had toiled the alluvial soil of these plains for years. Their numbers also included some of the large landowners as well as tenant labourers together justifying their newly attained prosperity by mounting claims on the Kshatriya status, thus rejecting the notion of prevalent Shudra categorisation for themselves. Despite their attempt to seek a noble Kshatriya past by claiming themselves as belonging to the lineage of Rama and Krishna, the British authorities and the Brahmins continued to view them as Shudras. The antipathy of social elites was also seen during this period, when Kunwar Chheda Sinha published a book on anti-Kshatriya reform in 1907, which was widely circulated by Rajput Anglo-Oriental Press.

-

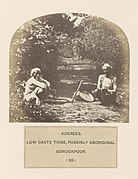

A 19th century image showing two Koeri men near Gorakhpur.

A 19th century image showing two Koeri men near Gorakhpur.

-

An "ethnographic" photograph from 1916 showing Kurmi farmers, both men and women, sowing a field

An "ethnographic" photograph from 1916 showing Kurmi farmers, both men and women, sowing a field

-

Another ethnographic print from 1868 showing a group of Ahirs, a Yadav subcaste near Delhi.

Another ethnographic print from 1868 showing a group of Ahirs, a Yadav subcaste near Delhi.

The concern for the cultural upliftment was felt by the acquired prosperity, which was to be attained through greater command on womenfolks. The Yadav peasants by the time prohibited the poor families among themselves to allow their women to go into the market to sell cow dung cakes, which was considered as a source of income for poor Yadav families. It was witnessed that the Kshatriya status seeking reformers among these peasant castes were divided into two categories on the basis of their attitude towards their womenfolk, while one group sought strict control over the women and even believed a fickle woman to be the cause of all sorrow of a household, women were apotheosized by others. This could be seen by the description of a Kurmi women by their caste reformers, who describe her to be a chaste women toiling the field alongside her husband. The chief concern of these Kshatriya status seeking reformers was ending the dominance of women in the economy of a peasant household, where they - unlike the upper-caste women - enjoyed the considerable economic power and independence by virtue of their role as agricultural labourer for their family. One of the Yadav reformers, Baijnath Prasad Yadav of Varanasi, thus argued to prohibit women from enjoying power in the financial affairs of a household, as according to him, their fickle greediness remains responsible behind its decay.

The upper-backwards were also involved in electoral politics, much earlier, prior to independence of India in 1930s. This period marked the formation of one of the first organisations of the Other Backward Castes, which aimed for their greater role in politics, and at the same time pitched for various social reforms, aimed at helping the Dalits or the untouchables to get rid of the unjust feudal practices. The Triveni Sangh, which claims to have a million members, paved the way for upper-backwards for getting into the electoral politics, but failed due to Congress's superior organisational structure, although it achieved some success in form of many social reforms, away from the ballot. By this time, the influence of Vaishnava pantheons led these peasant castes to claim their origin from Vishnu and his Avatars, this is specifically true for the Koeris and the Kurmis who claimed descent from the twin sons of Rama and Sita. The Koeris thus started calling themselves as Kushwaha, a name derived from Kusha, one of the son of demigod Rama, an Avatar of Vishnu.

In the 1960s, a major political change took place which paved the way for a non-Congress government in Bihar for a brief period of time. Jagdeo Prasad, a Kushwaha leader who was a part of Socialist Party of Ram Manohar Lohia, which later merged with Praja Socialist Party to form Samyukta Socialist Party, broke away to found his own Shoshit Samaj Dal with the help of another leader B.P Mandal. Prasad was dissatisfied with the links of Samyukta Socialist Party with Bharatiya Jana Sangh. Besides, Prasad also not supported Mahamaya Prasad Sinha and forged many pro-Backward radical slogans.

In 1982, the second Backward Class Commission headed by B.P Mandal submitted its report to Indira Gandhi and recommendations regarding 27% reservation for Backward Class in government jobs and educational institutions were made, which she chose to delay in the favour of her vote base which included the upper-caste, Mahadalit, and the Muslims. This coalition has been described as 'coalition of extremes' by political scientist Paul Brass, on the basis of stark differences in the socio-economic conditions of these groups. On the question of reservation for Backward Castes, Charan Singh organised a mass rally in New Delhi. The Congress regime ignored these developments with the view that the upper-caste which included rural gentry and urban intelligentsia has again returned their support to it, which was lost in 1977 due to pro-Dalit stance taken by Indira.

According to Sanjay Kumar, Dalits were a socially very weak community to pose any serious challenge to the upper-caste, who controlled the bureaucracy as well as their economic life during the period of Congress rule in Bihar. It was due to the control of bureaucracy by the upper-caste that even after a number of massacres perpetrated by them on the Dalits, no action was taken. The 'coalition of extreme' was also not natural as the upper-caste used various tactics to win the votes of Dalits in their favour. The polling booths of the Dalit constituency were usually established at the upper-caste dominated strongholds and the latter rigged those booths to make the Dalits vote in the favour of their candidates.

While the Congress remained inconspicuous to give important position to the upper-backwards within its ranks, the socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia was in the favour of it. He coined the slogan to give 60% of political posts to the backwards and wanted a coalition of the upper-backwards with lower backwards, the Dalits and the Muslims. The period of 1980s represents the consolidation of the political ambitions of the upper-backwards, who dominated the Lok Dal. The party though headed in Bihar by a lower-backward caste leader Karpoori Thakur, consolidated the upper-backward castes. The latter were conspicuous to share power within the Party with the upper-caste, and the social structure of the Lok Dal even provided the Lohiaite upper-caste leaders to play a second fiddle within the party. Karpoori Thakur too played important role in the unification of all sections of backwards together through his quota politics. The period of 1990s witnessed de-alignment of upper-backwards, as under Lalu Prasad Yadav, the process of "Yadavisation" was set in, which led to dominance of Yadavs in the politics while the Koeri and Kurmi were neglected. This led the twin castes to align with the upper-castes to challenge the dominance of Yadavs. Nitish Kumar, a former ally of Lalu Prasad Yadav thus broke away to form Samata Party, which represented political ambition of the Koeri and Kurmi caste.

By the 1995 elections, the upper-caste were completely marginalised in the political space and were replaced by the upper-backwards, who by now were divided into two faction dominating both the ruling party as well as the opposition under Lalu Prasad and Nitish Kumar respectively. The upper-caste though lost in political space to upper-backwards, were still powerful economically, as at the social level, Yadavs were still serving as the milkman while the Koeri-Kurmi were farmers.

By the beginning of the 21st century, the Backwards came to centre stage of politics in Bihar. The two factions, one led by Janata Dal (United) and another led by Rashtriya Janata Dal are controlled by Koeri-Kurmi and the Yadav caste respectively, while the extremely backward castes and Forward Castes are distributed across these parties according to their preference. According to social historian Badri Narayan, the latter's voting pattern ensure the victory of one of these blocs.

Affirmative action

Since 1970s, the affirmative action or the reservation criteria is different in Bihar from rest of the India. The central government provides 27% reservation as monolithic entity to the OBC which includes all OBC groups, but Bihar on the basis of Karpoori Formula has segregated the 27% quota with 18% to Extremely Backward Castes and 3% to Backward women.

Present circumstances

According to a report of Institute Of Human Development Studies, among the upper-backwards, castes like Kushwahas and Kurmis earn Rs 18,811 and Rs 17,835 respectively as their average per capita income, which is slight lesser than those earned by upper-caste, who earn 20,655 as their average per capita income. In contrast, Yadavs’ income is one of the lowest among OBCs at Rs 12,314, which is slightly less than the rest of OBCs (Rs 12,617). According to this report, the economic benefits of the Mandal politics could be seen as affecting only few backward castes of agrarian background leading to their upward mobilisation. Yadavs, who are considered as politically most dominant caste in Bihar have failed to translate their upward mobilisation in other fields.

As per studies related to the composition of the legislative assembly of Bihar, the Upper-Backwards have always been overreprented as compared to the lower-backwards. This trend has been in place since 1960s. In most of the areas of Bihar, except few districts like Bhojpur and Aurangabad, they outnumber the upper-caste. Though caste based census hasn't been done in post independence India, the estimates from British era caste census testifies these facts regarding their population distribution.

Ashwani Kumar notes that the upper backward classes like Yadav, Koeri, and Kurmi have become the new class of capitalist landlords or kulaks who are equally ruthless than the feudal landlords if not more. Many Upper OBC commit atrocities and prey exclusively upon Dalit women who work on their fields.

References

- Kumar, Ashwani (2008). Community Warriors: State, Peasants and Caste Armies in Bihar. Anthem Press. ISBN 9781843317098.

- Carolyn Brown Heinz (3 June 2013). Peter Berger; Frank Heidemann (eds.). The Modern Anthropology of India: Ethnography, Themes and Theory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-06118-1.

The four dominant high caste groups (the forward castes)-Brahman, Bhumihar, Rajput, Kayastha-together constitute about 12 percent of the population. These are the old elite, from whose numbers came the major zamindars and land owning castes. The so-called Backward castes consisting of about half the population of Bihar, were further classified soon after independence into Upper Backward and Lower Backwards(Blair 1980). The upper backwards – Bania, Yadav, Kurmi and Koiri – constitute about 19 percent of the population, and now include most of the rising Kulak class of successful peasants who have acquired land, adopted improved agricultural technology, and become a powerful force in Bihar politics. This is true, above all, of the Yadavas. The lower backwards are shudra castes such as Barhi, Dhanuk, Kahar, Kumhar, Lohar, Mallah, Teli etc, about 32 percent of the population. The largest components of the scheduled castes(14 percent) are the Dusadh, Chamar, and Musahar, the Dalit groups who are in many parts of the statelocked in struggles for land and living wages and living wages with the rich peasants and landlords of the forward and upper backward castes

- George J. Kunnath (2017). Rebels From the Mud Houses: Dalits and the Making of the Maoist Revolution in Bihar. Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-351-41874-4. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- Backward Classes Commission (1981). Report of Backward Class Commission. Controller of Publications, 1981. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

Among the upper backward castes, the Yadavas and Kurmis had begun to organise themselves along the caste lines during the first decade of this century (Rao, 1979) . The All – India Yadav Mahasabha has its headquarters at Patna, and the Bihari Yadavas, along with their counterparts in ... The political fall out of the Yadava, Kurmi and Koeri movements were, however, limited in the beginning

- Ishwari Prasad (1986). Reservation, Action for Social Equality. Criterion Publications. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

Here we are concerned only with upper backwards which have four castes ; Yadav (11.0 per cent), Koeri (4.0 per cent), Kurmi (3.5 per cent) and Bania (0.6 per cent) .

- ^ Christophe Jaffrelot; Sanjay Kumar, eds. (2012). Rise of the Plebeians,The Changing Face of the Indian Legislative Assemblies. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-136-51661-0. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- Anand Vardhan, ed. (24 October 2020). "Caste, land and quotas: A history of the plotting of social coalitions in Bihar till 2005". newslaundary. Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- Kunnath, George (2018). Rebels From the Mud Houses: Dalits and the Making of the Maoist Revolution ... New york: Taylor and Francis group. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-138-09955-5. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

However, the greatest beneficiaries of the abolition of the zamindars and the introduction of the various land-reform legislation in the 1950s were members of a substantial class of mediumsized owner cultivators, many of whom belonged to the upper layers of backward castes, mostly the yadav, kurmi, koeri. They gained additional land as a result of partitions, transfers and sales of surplus land by zamindars. It is estimated that during this period, 'control over at least 10 percent of land passed into the hands of the middle peasantry' from the landlords. (prasad1979:483).

- "(Monograph 01/2013) Subaltern Resurgence, A Reconnaissance of Panchayat Election in Bihar" (PDF). Asian Development Research Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

Even in the Panchayat Election of 1978 itself, that was held no less than twenty-three years ago, there was visible shift in the political centre of gravity. Karpoori Thakur, the then Chief Minister, had implemented the Mungeri Lall Commission Report, which entailed reservation in the state government jobs, for the lower backwards (Annexure I castes) and the upper backwards (Annexure II castes) in Bihar

- William R. Pinch (1996). Peasants and Monks in British India. University of California Press. pp. 115–116. ISBN 0-520-91630-1. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- William Pinch (1996). Peasants and Monks in British India. University of California Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 0-520-20061-6. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. London: C. Hurst & Co. pp. 197–199. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- Santosh Singh (2020). "Jagdev Prasad : The revolutionary who gave his life". JP to BJP: Bihar after Lalu and Nitish. SAGE Publishing India. ISBN 978-9353886660.

- ^ Sanjay Kumar (2018). Post-Mandal Politics in Bihar: Changing Electoral Patterns. SAGE Publishing India. pp. 51–53. ISBN 978-9352805860. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- Thakur, Baleshwar (2007). City, Society, and Planning: Society. University of Akron. Department of Geography & Planning, Association of American Geographers: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-8180694608. Retrieved 16 June 2020. While Samta with its leader Nitish is considered to be the party of Koeri-Kurmi, Bihar people's party led by Anand Mohan is perceived to be a party having sympathy and support of Rajputs.

- Sanjay Kumar (2018). Post-Mandal Politics in Bihar: Changing Electoral Patterns. SAGE Publishing India. p. 61. ISBN 978-9352805860. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- "How OBCs Moved from Fringes to Centre of Bihar Politics through Social and Political Movements Since 1930s". News18. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- "Nitish Kumar demands separate quota for EBCs in central government jobs". Times of India. 24 January 2018. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- "Following the Karpoori Thakur model, OBC sub-categorisation could be icing on BJP's cake". ThePrint. 4 October 2017. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- Christophe Jaffrelot; Kalaiyarasan A, eds. (4 November 2020). "Lower castes in Bihar have got political power, not economic progress". Indian Express. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Harry W., Blair (1980). ""Rising Kulaks and Backward Classes in Bihar: Social Change in the Late 1970s."". Economic and Political Weekly. 15 (2): 64–74. JSTOR 4368306.

- Kumar, Ashwani (2008). Community Warriors: State, Peasants and Caste Armies in Bihar. Anthem Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-84331-709-8.