Tasmania can be broadly divided into two distinct regions, eastern and western, that exhibit major differences in climate, geology and vegetation. This divide, termed Tyler's Corridor (in recognition of Peter Tyler, a Tasmanian limnologist), runs from just south of the northwestern corner, and continues south, cutting roughly down the center of the island. The vegetation changes occur principally due to variations in soil types, which are a result of the geological composition, and the vast difference in climate across the state. Generally, the west has a higher mean rainfall but poor acidic soil while the east has a lower mean rainfall but slightly more fertile soil. This results in a larger proportion of rainforest, moorland and wet sclerophyll vegetation dominating in the west and predominantly dry sclerophyll in the east.

Geology and soil

Tasmania, despite its size, has a very complex and diverse geology. As a geologic simplification, the western half of the state is characterised as being a more ancient fold province and the east, a younger intruded fault province. Western Tasmania contains a vast variety of ancient, deeply folded metamorphosed and non-metamorphosed rocks, namely the Mesoproterozoic quartzite, schist and phyllite. Other more recent geologic signatures are scattered across the west, such as Ordovician limestone, Neoproterozoic dolomite basalt, Devonian granite (in the northwest) and Cambrian sediments. The extensive folding of these rocks (particularly the quartzite) formed jagged mountain ranges and deep river valleys. Exposed to lengthy periods of erosion, the Mesoproterozoic rocks were worn down to shallow, acidic and infertile soil due to their high silica content. The central (central highlands) and southeastern areas are composed of much younger sedimentary rocks that have been intruded by magma, which forms sills and dykes of dolorite. This area has also been impacted by volcanic activity (in the Tertiary period) that has deposited basaltic rock across the landscape. Contrasting with the generally quartzitic soil of the west, basalt is higher in nutrients and, depending on extent of weathering, fertility. The weathering of eastern dolorite intrusions produces clay based soils that (with enough water), like basalt, will allow higher levels of plant production than in the west.

Climate

Tasmania has an incredibly varied climate that is representative of its landforms and location. Tasmania lies between southern latitudes 40–50 degrees and experiences a temperate oceanic climate. Coastal regions rarely experience maximum temperatures below 10 °C, altitudes of 450 m may have maximum temperatures below 10 °C for two months of the year and altitudes of 1000 m or greater will have maximum temperatures below 10 °C for over 6 months of the year. The western region of Tasmania is impacted greatly by the Roaring Forties, strong westerly winds in the southern hemisphere, which cool the rising air mass and reduce air temperatures in this region. Due to the mountain ranges that are scattered predominantly along the west and centre of the east-west divide, the Föhn effect of descending air mass results in a warmer and drier east. The bias of strong winds to the west of the state results in a distinct precipitation gradient from west to east. Western mountain ranges can receive up to 3600 mm of rainfall per year, whereas the east may only accumulate 500 mm.

Vegetation variation

Tasmania has a wide range of vegetation types for its size, which is reflective of its varied geology, topography and climate. The wetter western environments have many similar plant groups to New Zealand and South America due to the persistence of ancient Gondwanan flora that the wet climate permits. The east generally has vegetation that is more characteristic of dry mainland Australia. Although not expressive of the vast mosaic of Tasmanian vegetation communities, the Tasmanian vegetation types can be broadly categorised into seven types: temperate rainforest, wet sclerophyll, alpine and sub-alpine, dry sclerophyll, coastal, moorland, sedgeland and cleared land.

The West

To the west, temperate rainforest, wet sclerophyll and moorland/sedgeland vegetation communities are broadly dominant. Tasmanian temperate rainforests are scattered from the north to south in the west of the state with the majority occurring in the northwest (the Tarkine). Species dominance changes with altitude, montane and lowland rainforest being dominated mostly by Nothofagus species, however the lowland rainforests can also be dominated by Atherosperma, Eucryphia, Phyllocladus and Anodopetalum in less fertile soils. Valleys with high rainfall and low soil fertility may be dominated by conifers Lagarostrobos and Phyllocladus, respectively. There are some corridors of rainforest that can penetrate into the eastern highlands, which is at a much lower altitude. Wet sclerophyll forests are similarly scattered from north to south of western Tasmania (and in some parts of eastern Tasmania, particularly the southeast), however occur in areas of greater fire disturbance. The peppermint Eucalyptus nitida usually dominates the western wet sclerophyll forests when on poor quartzite soils. Understory species consist of Acacia species, Olearia, Bedfordia and Pomaderris. Moorland and sedgeland communities cover a considerable area (17% of the state) with the majority in the southwest of the state. They are fire dependent communities that thrive on poorly drained quartzite soils in wet environments. Thus, the vegetation is composed of pyrogenic heaths (family Ericaceae) and sedges (family Cyperaceae). The dominant species in these communities are Gymnoschoenus sphaerocephalus (buttongrass) in muck peat and Lepidosperma filiforme on more skeletal soils. Moorland and sedgeland vegetation is characteristic of western Tasmania, however also occurs sparsely in areas of low rainfall and poorly drained soils towards the east of the state.

Buttongrass moorland Southwest Tasmania

Buttongrass moorland Southwest Tasmania

The East

To the east dry winds and greater sun exposure result in vegetation bearing smaller leaves and thick waxy cuticles. The dominant vegetation communities are dry sclerophyll forests and Acacia/ Collitris dry woodland. Dry sclerophyll is a huge community occupying over 25% of the state. It is much more open with only 20–25% light interception. Eucalyptus species form the canopy layer and are varied across dry sclerophyll forests depending on altitude, soil type, amount of water and aspect. Closer to the coast Eucalyptus globulus, Eucalyptus brookeriana and Eucalyptus regnans are dominant. When merging with wet Eucalypt forests or in areas with more moisture or shade, Eucalyptus obliqua and Eucalyptus viminalis are present.

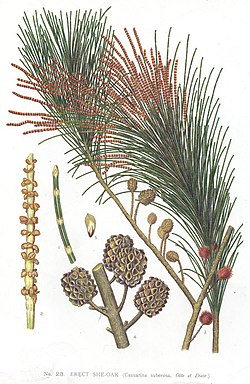

In contrast to the wet sclerophyll forests in the west of the state, dry sclerophyll lacks a tall understorey. The understorey is typically composed of a sparse scatter of low trees from the genera Exocarpus, Allocasuarina, Banksia and Bursaria. The shrub layer is very diverse and contains many species from families Asteraceae (daisy family), Fabaceae (pea family), Epacridaceae (heath family) and Myrtaceae.

Dry woodlands are formed by either genus Allocasuarina or Callitris in habitats where it is difficult for eucalypts to thrive. On the east coast Allocasuarina verticillata woodlands inhabit shallow and rocky soils in very dry climates. Understorey is usually composed of Dodenea and Bursaria, sometimes with a prostrate shrub layer of Astroloma, Acrotriche and Lissanthe. The Allocasuarina has reduced scale leaves and photosynthetic branchlets, among other adaptations such as drooping leaves that allow it to thrive in dry habitats and infertile soils. Callitris woodlands occur on the dolerite and basaltic soils of the east coast and are sensitive to fire, limiting distribution. Understorey is usually limited to a few shrubs such as Dodonaea and grasses.

Both the east and west have relatively similar coastal vegetation, however due to the larger swells of the west and the depositional process of the eastern shores, the west is much rockier and the east has more beaches. The west also has much more fire disturbance than the east. In the west, frontal dunes are vegetated with genera Disphyma, Carpobrotus and Acaena. Leptospermum species and Leucopogon australis are common on the upper strata and the lee faces of dunes support Banksia and Leucopogon parviflorus. The dunes in the east have more grass such as Spinifex hirsutus, Poa triodioides (syn. Festuca littoralis) and other Poa species. Behind these dunes, Banksia woodland merges with dry sclerophyll E. viminalis dominated woodland.

References

- Tyler, Peter (1992). "A lakeland from the dreamtime: the second founders' lecture". British Phycological Journal. 27 (4): 353–368. doi:10.1080/00071619200650301.

- Tyler, Peter (December 2007). "The distinctive limnological character of south west Tasmania". Australasian Plant Conservation. 16 (3): 27–28.

- ^ Rees, Andrew.B.H; Cwynar, Les.C (2010). "A test of Tyler's Line - response of chironomids to a pH gradient in Tasmania and their potential as a proxy to infer past changes in pH". Freshwater Biology. 55 (12): 2521–2540. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.2010.02482.x.

- ^ Reid, James.B; Hill, Robert.S; Brown, Michael.J; Hovenden, Mark.J (2005). Vegetation of Tasmania. Tasmania: Australian Biological Resources Study. p. 108.

- Marshak, Stephen (2011). Earth: Portrait of a Planet (Fourth ed.). USA: W W NORTON & Company. p. 283.

- ^ Seymour, D.B.; Green, G.R.; Calver, C.R. (2007). The Geology and Mineral Deposits of Tasmania: a summary (PDF). Tasmanian Geological Survey Bulletin. Vol. 72. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7246-4017-1.

- ^ Cotching, Bill (2009). Soil Health for Farming in Tasmania. Tasmania: Richmond Concepts & Print. p. 95.

- Langford, J (1965). "Weather and climate". Atlas of Tasmania. Tasmania: Lands and surveys. pp. 2–11.

- Sharples, J.J; Mills, G.A.; McRae, R.H.D.; Weber, R.O. (2009). "Fire danger anomalies associated with foehn-like winds in southeastern Australia". 18th World IMACS: 268.

- Hill, Robert.S (December 1990). "Sixty Million Years of Change in Tasmania's Climate and Vegetation". Tasforests: 89.

- Worth, J.R; Jordan, G.J; McKinnon, G.E; Vaillancourt, R.E (2009). "The major Australian cool temperate rainforest tree Nothofagus cunninghamii withstood Pleistocene glacial aridity within multiple regions: evidence from the chloroplast" (PDF). New Phytologist. 182 (2): 519–532. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02761.x. PMID 19210718.

- Jackson, W.D (1983). "Tasmanian Rainforest Ecology". Tasmania's Rainforest's: What Future. Hobart: Australian Conservation Foundation. pp. 9–39.

- Jarman, S.J; Kantvilas, G; Brown, M.J (1988). "Buttongrass Moorlands in Tasmania". Tasmanian Forest Research Council Research Report No.2.

- ^ Duncan, F; Brown, M.J (1985). "Dry Sclerophyll vegetation in Tasmania". Wildlife Division Technical Report 85/1- National Parks and Wildlife Services.

- Crowley, G.M (1986). Thesis: Ecology of Allocasuarina littoralis. James Cook University.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Parker, D.G (1999). "Structural patterns and changes in Callitris - Eucalyptus woodlands at Terrick Terrick State Park, Victoria". Victorian Grassy Ecosystems Reference Group.

- Colhoun, E.A (1989). "The Quaternary". The Geology and Mineral Resources of Tasmania. Brisbane: Geological Society of Australia. pp. 410–418.