| |

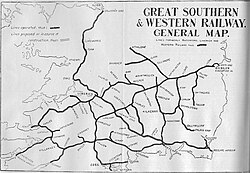

1920 map of the railway 1920 map of the railway | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Dates of operation | 1844–31 December 1924 |

| Successor | Great Southern Railways |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in) |

| Length | 1,148 miles 2 chains (1,847.6 km) (1919) |

| Track length | 1,554 miles 58 chains (2,502.1 km) (1919) |

The Great Southern and Western Railway (GS&WR) was an Irish gauge (1,600 mm (5 ft 3 in)) railway company in Ireland from 1844 until 1924. The GS&WR grew by building lines and making a series of takeovers, until in the late 19th and early 20th centuries it was the largest of Ireland's "Big Four" railway networks. At its peak the GS&WR had an 1,100-mile (1,800 km) network, of which 240 miles (390 km) were double track.

The core of the GS&WR was the Dublin Kingsbridge – Cork main line; Ireland's "Premier Line", and still one of her most important main line railways. The company's headquarters were at Kingsbridge station. At its greatest extent the GS&WR included, in addition to the Dublin – Cork main line, the Dublin – Waterford and Mallow – Waterford lines and numerous branch lines.

Origins

There had been earlier attempts to set up main line railways to the south of Ireland but the 1840s efforts of Peter Purcell, a wealthy landowner and mail coach operator, and his associates were ultimately to prove successful with the implementation of a bill passed on 6 August 1844 for the GS&WR. Purcell was actively assisted by engineer John Benjamin MacNeill who had done surveys for the London and Birmingham Railway and had connections in London. The GS&WR's vision to provide a single railway for most of the south of Ireland found favour with United Kingdom Prime Minister Robert Peel as having likely more profitably for wealthy investors and because a single company would be easier to control; these factors likely easing the passing of relevant legislation.

Network

Dublin – Cork Main Line

William Dargan, Ireland's foremost railway contractor, built much of the GS&WR's main line and a number of its other routes.

The directors chose to begin by construction of the 32.5 mi (52.3 km) stretch of the Dublin – Cork main line as far as Cherryville Junction just west of Kildare and the 23.5 mi (37.8 km) branch to Carlow with contracts shared between McCormack and Dargan. Work began in January 1845 with services commencing on 4 August 1846. Trains were scheduled to take about 2hr 35min for the 56 mi (90 km) stretch to Carlow and coach connections were arranged to Kilkenny, Clonmel, Waterford and the evening mail coach for Cork.

In July 1848 the main line reached Limerick Junction, where it met the Waterford and Limerick Railway and thus linked Dublin and Limerick by rail.

In October 1849 the main line reached the outskirts of Cork, where the GS&WR opened a temporary terminus at Blackpool. The final 1-mile (1.6 km) of line from Blackpool to the centre of Cork includes a 1,355-yard (1,239 m) tunnel and was not completed for another six years. Services through the tunnel began in December 1855, running to and from a second temporary terminus beside the River Lee. Finally the present Cork terminus in Glanmire Road opened in July 1856.

Expansion and competition

The Irish South Eastern Railway opened between the GS&WR station at Carlow and Bagenalstown in 1848 and reached Lavistown in 1850. From the outset the ISE was worked by the GS&WR. The Waterford and Kilkenny Railway had already reached Lavistown, and thus completion of the ISE enabled GS&WR services to reach Kilkenny. The W&KR reached Waterford in September 1854 but its relations with the GS&WR were poor, which impeded traffic between Dublin and Waterford by this route. In 1877 the W&KR took over the Central Ireland Railway and became the Waterford and Central Ireland Railway. The GS&WR took over the W&CIR in 1900, thus belatedly bringing the rail route between Dublin and Waterford under the control and operation of a single company.

The GS&WR competed with the Midland Great Western Railway for many years. Both ran services between Dublin and the west of Ireland: the GS&WR running southwest to Limerick, Cork and Waterford, and the MGWR running west to Galway, Westport, Ballina, and Sligo. The GS&WR also had designs on rail traffic to the west of Ireland. In 1859 the GS&WR opened a branch line from the Dublin – Cork main line to Athlone where it connected with the MGWR's Dublin – Galway main line. In the latter half of the 20th century Córas Iompair Éireann made this GS&WR branch part of its Dublin – Galway main line.

Waterford, Limerick and Western Railway

Main article: Waterford, Limerick and Western RailwayIn 1901 the GS&WR bought the Waterford, Limerick and Western Railway, which gave it both the Waterford – Limerick – Athenry – Claremorris – Collooney cross-country route and the North Kerry line and branches. The WLWR, recently dubbed the Western Rail Corridor, crossed MGWR territory. It complemented the radial MGWR lines from Dublin, enabling Limerick – Galway and Galway – Sligo traffic, and linked intermediate destinations in the west of Ireland. For a very short time the MGWR exercised running powers over the Athenry – Limerick section of this route.

North Wall extension

The line was opened in 1877 to resolve limitations with the GS&WR neither having rail access convenient to the cattle market at Cabra nor to the docks at North Wall where there was a requirement for goods, cattle and passenger services. The London and North Western Railway (LNWR) was supportive of the venture as was the rival Midland Great Western Railway (MGWR) who were to receive tolls for part of the route.

The branch opened on 2 September 1877 diverging from the main GS&WR line at Islandbridge Junction before tunneling under Phoenix Park to Cabra where cattle sidings and pens were constructed. After passing under the MGWR line to Broadstone and the MGWR's Liffey Branch to North Wall the route curved back to join the MGWR at Glasnevin Junction. Joint running rights were obtained over the MGWR route until Church Road junction in the North Wall complex, after which the route diverged to the GS&WR's new cattle pens and sidings. Link spurs were available at Newcomen Bridge to Amiens Street station and to the LNWR station at North Wall for passenger ships to Great Britain.

Drumcondra link line

1891 had seen the connection to the Dublin, Wicklow and Wexford Railway (DW&WR) following the opening of the Dublin loop line from Westland Row with additional traffic to the Liffey branch line. The GS&WR eventually moved on an opportunity to open an alternative route line from at what was to be known as Drumcondra junction which diverged just before the junction to the MGWR at Glasnevin. The route ran to the north of Croke Park then rejoined the MGWR just before Church Road junction in the North wall complex allowing the same access at North Wall for GS&WR services. Opening on 1 April 1901 it avoided the MGWR's Liffey branch tolls. A spur from the Drumcondra link line to the DW&WR at Amiens Street was finally realised on 1 December 1906.

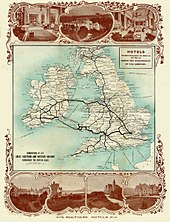

GS&WR hotels

In an effort to encourage tourism the Killarney Junction Railway, which was operated by the GS&WR, opened a hotel next to Killarney station. This was in 1854, which made it the first railway-owned hotel in Ireland and one of the first of its kind in the World. In the following years the GS&WR established further hotels in County Kerry at Caragh Lake, Kenmare, Parknasilla (about 3/4 of a mile to the southeast of Sneem) and Waterville. The company also owned small commercial hotels at Limerick Junction and near its stations in Dublin and Cork.

In 1925 the hotels became part of Great Southern Hotels, a subsidiary of Great Southern Railways. The Great Southern Hotels Group was dissolved in 2006, when its hotels were sold off separately to private investors.

GS&WR strike

In September 1911 the workers of the Great Southern and Western Railway went on strike nationally after two checkers at Kingsbridge goods station in Dublin were suspended for refusing to handle timber that had been delivered by "blackleg" lorry drivers during a strike by the timber merchant's workers. The British Army was brought in to guard tracks and trains, and Protestant strike-breakers from elsewhere in Ireland to do the work of the strikers. The strike was savagely broken in two months, with the railway's proprietor, William Goulding, sacking 10% of the workers for their participation in the strike. Goulding told his associates, "Now that we have the men defeated, we'll never have any more trouble."

People

Peter Purcell, a wealthy landowner and mail coach operator, was the main mover of the GS&WR railway and became its first chairman:

|

Alternative titles include engineer, engineer-in-chief, chief civil engineer.

|

At different times in its history the GS&WR variously used the titles Locomotive Engineer, Locomotive Superintendent or Chief Mechanical Engineer to describe the same post.

|

Incidents

Lombardstown train crash

A year after the 1911 strike, on 5 August 1912 at 8.50pm, an excursion train from Killarney crashed in Lombardstown, near Mallow in Cork. The driver had been on duty from 3.50am. Of the 200 passengers on board, 96 were seriously injured, one of whom later died as a result.

Kiltimagh train crash

On 19 December 1916, in foggy conditions, the driver of a ballast train failed to see a red signal at Kiltimagh, County Mayo. The train, carrying many track workers, crashed into an empty cattle train, killing six people.

Aftermath

Great Southern Railways

An Act passed by the Dáil Éireann in 1924 merged the GS&WR with the Midland Great Western Railway, the Cork, Bandon and South Coast Railway and most other railways wholly within the Irish Free State to form the Great Southern Railway. In January 1925 the GSR merged with the Dublin and South Eastern Railway to form the Great Southern Railways. Cross-border railways were excluded from the mergers.

Córas Iompair Éireann

In 1945 further amalgamation with the Grand Canal Company and the Dublin United Tramway Company created Córas Iompair Éireann ("Irish State Transport Company"). CIÉ was nationalised in 1950, but was divided into separate rail and road companies in 1987. Since then, the railways have been operated by Iarnród Éireann ("Irish Rail").

GS&WR routes today

GS&WR routes remain some of the most heavily used in Ireland, linking Dublin with Limerick, Cork, and Waterford. The coats of arms of these cities still adorn the facade of Heuston Station.

See also

Notes

- It is called the Liffey branch because it diverged from the main line at Liffey Junction; it actually runs mostly alongside the Royal Canal and passes just to the south of Croke Park stadium.

- Glasnevin and Drumcondra junctions were remodelled in the 1930s to allow trains from the former MGWR lines access to Amien Street and Westland Row via the Drumcondra link line, while the line from Islandbridge lost access to the Liffey Branch.

References

- ^ The Railway Year Book for 1920. London: The Railway Publishing Company Limited. 1920. p. 147.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 15.

- ^ Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 106.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 11.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), pp. 14–15.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), pp. 15–16, 186.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), pp. 17.

- ^ Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 18.

- ^ Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 178.

- ^ Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 21.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 64.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), pp. 33, 62–63.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 62.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 68.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 24.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 107.

- ^ Murray & McNeill (1976), pp. 48–51.

- Shepherd (1994), pp. 36–41.

- Shepherd (1994), pp. 37, 107.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 26.

- ^ Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 182.

- "The Great Southern Railway Strike of 1911". theirishstory.com. 9 March 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), pp. 15, 196.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 196.

- Murray & McNeill (1976), p. 197.

- "Accident Returns: Extract for Accident at Lombardstown on 5th August 1912 :: The Railways Archive". www.railwaysarchive.co.uk.

- Comer, Michael. "The Kiltimagh Railway Disaster of 1916". West On Track. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- "Accident at Kiltimagh on 19th December 1916" (PDF). Railways Archive. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

Sources and further reading

- Ahrons, E. L. (1954). L. L. Asher (ed.). Locomotive and train working in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Vol. six. W Heffer & Sons Ltd.

- Murray, K.A.; McNeill, D.B. (1976). Great Southern & Western Railway. Dublin: Irish Railway Record Society. ISBN 0-904078-05-1.

- O'Mahony, John; Praeger, R. Lloyd (1902). The Sunny Side of Ireland – how to see it by The Great Southern and Western Railway. Dublin: Alex Thom & Co.

- Shepherd, Ernie (1994). The Midland Great Western Railway of Ireland. Leicester, England: Midland Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-85780-008-7.