| Wagon Box Fight | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Red Cloud's War | |||||||

An illustration of the engagement | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Lakota Sioux | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Red Cloud Crazy Horse High Backbone | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

26 soldiers 6 civilians | 300–1,000 warriors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

7 killed 2 wounded |

~6 (2 to 60) killed 6 wounded | ||||||

The Wagon Box Fight was an engagement which occurred on August 2, 1867, in the vicinity of Fort Phil Kearny during Red Cloud's War. A party of twenty-six U.S. Army soldiers and six civilians were attacked by several hundred Lakota Sioux warriors. Although outnumbered, the soldiers were armed with newly supplied breech-loading Springfield Model 1866 rifles and lever-action Henry rifles, and had a defensive wall of wagon boxes to protect them. They held off the attackers for hours with few casualties, although they lost a large number of horses and mules driven off by the raiders.

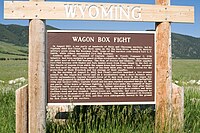

This was the last major engagement of the war, although Lakota and allied forces continued to raid European-American parties along the Bozeman Trail. The area has been designated as a Wyoming State Historic Site and is marked by a memorial and a historic plaque.

Background

In July 1867, after their annual Sun Dance at camps on the Tongue and Rosebud rivers, Oglala Lakota warriors under Red Cloud, other bands of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and a few Arapaho resolved to attack the soldiers at nearby Fort C. F. Smith and Fort Phil Kearny. These would be the first major military actions of 1867 against U.S. government forces in the area, following up the Native American successes in 1866, including the Fetterman Fight. Unable to agree where to attack first, the Sioux and Cheyenne force — variously estimated at between 300 and 1,000 men — split into two large bodies, moving against Fort C.F. Smith, and a similar number, mostly Sioux and possibly including Red Cloud, headed toward Fort Phil Kearny.

In addition to guarding emigrants on the Bozeman Trail, major tasks occupying the 350 soldiers and 100 civilians at Fort Phil Kearny included gathering wood and timber from a pine forest about five miles from the Fort and cutting hay for livestock in prairie areas. These jobs were performed by civilian contractors, usually armed with Spencer repeating rifles and accompanied and guarded by squads of soldiers. The hay cutters and wood gatherers had been a favorite target of the local Indian warriors since Fort Phil Kearny was established one year earlier. The Indians had conducted dozens of small raids, killing several dozen soldiers and civilians, and driving off hundreds of head of livestock for their own use.

The soldiers were on the defensive, suffering a lack of horses and trained cavalrymen, and limited by their muzzle-loading Springfield Model 1861 muskets, which were essentially obsolete by this time. But the soldiers had recently been issued breech-loading rifles that could fire about three times faster than muzzle-loaders and could be more easily re-loaded from a prone position.

The native population were poorly armed, probably possessing only about 200 firearms and fewer than two bullets per gun. Bows and arrows were their basic weapon. While the Indians used these effectively at short range in a fight against a mobile opponent, whether on horseback or on foot, they were ineffective weapons against a well entrenched or fortified enemy.

To protect against raids near the pine forest, the civilian contractors had constructed a corral. It consisted of 14 wooden bodies of wagons, which were removed from the chassis and placed on the ground in an oval 60–70 ft (18–21 m) long and 25–30 ft (7.6–9.1 m) wide. Both soldiers and civilians in the wood-cutting details lived in tents outside the corral of wagon boxes but could retreat to it for defense. On July 31, Captain James Powell and his command of 51 troops departed the walls of Fort Phil Kearny on a 30-day assignment to guard the wood cutters. Until then, the summer had been quiet, with few hostile encounters with the local Native Americans.

The fight

On the morning of August 2, Captain Powell's force was divided. Fourteen soldiers were detailed to escort the wood train to and from the fort; 13 soldiers guarded the wood-cutting camp, about one mile from the wagon box corral. The Indian plan of attack on the woodcutters and soldiers was tried-and-true, similar to the plan used the previous year to kill Fetterman's force, a total of 81 lost. A small group of Indians would entice the soldiers to chase them, leading the men into an ambush by a larger hidden force. Crazy Horse was among the members of the decoy team.

The plan broke down when a number of fighters attacked an outlying camp of four woodcutters and four soldiers, killing three of the soldiers. The other soldier and the woodcutters escaped and warned the soldiers near the corral. The pursuing force halted at the woodcutter's camp to loot and seize the large number of horses and mules there, which gave the soldiers taking refuge in the corral time to prepare for the attack. There were 26 soldiers and six civilians in the corral.

The first assault on the wagon box corral came from mounted warriors from the southwest, but the raiders encountered heavy fire from the soldiers using the new breech-loaders. The attackers withdrew, regrouped, and launched several further attacks on foot. They killed Powell's second-in-command, Lt. Jenness, and two soldiers. The battle continued from about 7:30 a.m. until 1:30 pm. The defenders had plenty of ammunition, and were well-defended from arrows behind the thick sides of the wagon boxes.

The garrison at Fort Phil Kearny learned of the fight from its observation station on Pilot Hill. About 11:30 a.m., Major Benjamin Smith led 103 soldiers out of the fort to the wood camp to relieve the soldiers in the wagon boxes. Smith took with him 10 wagons, driven by armed civilians, and a mountain howitzer. He proceeded carefully and, when he neared the wagon box corral, began firing his cannon at long range. The attackers were forced to withdraw. Smith advanced without opposition to the corral, collected the soldiers, and returned quickly to Fort Kearny. Additional civilian survivors, who had hidden in the woods during the battle, made it back to the fort that night.

Aftermath

The Wagon Box Fight is prominent in the folklore and literature of the Wild West as an example of a small group of well-equipped professionals holding off a much larger but poorly equipped force. The new, faster-shooting rifles are cited as the principal reason for their success.

Estimates of casualties among the Sioux and Cheyenne warriors range from "an unlikely low of two to an absurd fifteen hundred." Captain Powell estimated that his men killed 60, a "wildly exaggerated" estimate in the opinion of historian Keenan. Historians Drury and Clavin said that the Government's figure of 60 dead was "probably inflated."

The Wagon Box Fight was the last major engagement of Red Cloud's War. Possibly the results of this battle, and the similar Hayfield Fight near Fort C.F. Smith a day earlier, discouraged the native warriors from attempting additional large-scale attacks against government forces. "This was the last large charge Crazy Horse ever led against whites occupying a strong defensive position. He had learned that Indians with bows and arrows could not overwhelm whites armed with breech-loaders inside a fortification." For the remainder of 1867, the Lakota and their allies concentrated on small-scale, hit-and-run raids against parties along the Bozeman Trail.

Wyoming has designated the area as a state historic site; a large plaque explains the details of the fight.

In popular culture

The fight is depicted in the 1951 Western film Tomahawk.

See also

References

- ^ Keenan, Jerry (1990). The Wagon Box Fight. Boulder, Colorado: Lightning Tree Press. p. 22. ISBN 1882810872.

- ^ Hyde, George E. (1937). Red Cloud's Folk. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 159. ISBN 0806115203.

- Olson, James C. (1975). Red Cloud and the Sioux Problem. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 9780803258174.

- Price, Catherine (1996). The Oglala People, 1841–1879: A Political History. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska. p. 64. ISBN 0803287585.

- Brown, Dee (1962). The Fetterman Massacre. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. p. 223. ISBN 1453274162.

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen E. (1996). Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors. New York: Anchor Books. ISBN 1497659256.

- Drury and Clavin, The Heart of Everything That Is. Simon & Schuster, 2014, page 205

External links

- Fort Phil Kearny State Historic Site Archived 2015-11-23 at the Wayback Machine

- "Wagon Box Fight", a detailed, first-hand account of the fight, on Rootsweb

- Wagon Box Fight Archived 2006-02-13 at the Wayback Machine, details and list of participants, Wyoming State Parks

- Narrative and photos, Wyoming Tales and Trails

- Hebard, Grace; Brininstool, E. A. (1922). The Bozeman Trail: Historical Accounts of the Blazing of the Overland Routes, Volume II. The Authur H. Clark Company.

- "2nd Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment (Mechanized) 'Manchu'". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

44°33′32″N 106°53′54″W / 44.55889°N 106.89833°W / 44.55889; -106.89833

| Native American battles in Wyoming | |

|---|---|

| Wars |

|

| Battles |

|

| Massacres |

|

| Timeline of pre-statehood Wyoming history | |