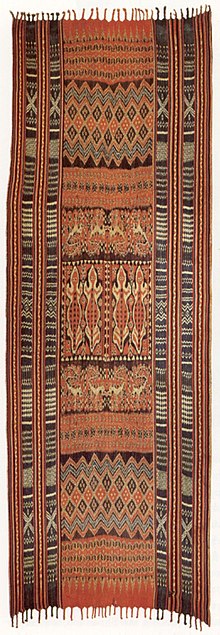

A typical Torajan ikat funeral shroud (porilonjong), Sulawesi, Indonesia A typical Torajan ikat funeral shroud (porilonjong), Sulawesi, Indonesia | |

| Material | cotton, silk, silk cotton |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Southeast Asia (Austronesian and Daic-speaking peoples) |

Ikat (literally "to bind" in Malayo-Polynesian languages) is a dyeing technique from Southeast Asia used to pattern textiles that employs resist dyeing on the yarns prior to dyeing and weaving the fabric. In Southeast Asia, where it is the most widespread, ikat weaving traditions can be divided into two general groups of related traditions. The first is found among Daic-speaking peoples (Laos, northern Vietnam, and Hainan). The second, larger group is found among the Austronesian peoples (Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Timor-Leste) and spread via the Austronesian expansion to as far as Madagascar. It is most prominently associated with the textile traditions of Indonesia in modern times, from where the term ikat originates. Similar unrelated dyeing and weaving techniques that developed independently are also present in other regions of the world, including India, Central Asia, Japan (where it is called kasuri), Africa, and the Americas.

In ikat, the resist is formed by binding individual yarns or bundles of yarns with a tight wrapping applied in the desired pattern. The yarns are then dyed. The bindings may then be altered to create a new pattern and the yarns dyed again with another colour. This process may be repeated multiple times to produce elaborate, multicolored patterns. When the dyeing is finished all the bindings are removed and the yarns are woven into cloth. In other resist-dyeing techniques such as tie-dye and batik the resist is applied to the woven cloth, whereas in ikat the resist is applied to the yarns before they are woven into cloth. Because the surface design is created in the yarns rather than on the finished cloth, in ikat both fabric faces are patterned. Ikat can be classified into three general types: warp ikat and weft ikat, in which the warp and weft yarns are dyed, respectively; and double ikat, where both the warp and weft yarns are dyed.

A characteristic of ikat textiles is an apparent "blurriness" to the design. The blurriness is a result of the extreme difficulty the weaver has lining up the dyed yarns so that the pattern comes out perfectly in the finished cloth. The blurriness can be reduced by using finer yarns or by the skill of the craftsperson. Ikat with little blurriness, multiple colours and complicated patterns are more difficult to create and therefore often more expensive. However, the blurriness that is so characteristic of ikat is often prized by textile collectors.

Etymology

Ikat is an Indonesian word, which depending on context, can be the nouns: cord, thread, knot, or bundle, also the finished ikat fabric, as well as the verbs "to tie" or "to bind"; the term ikatan is a noun for bond or tie. It has a direct etymological relation to cognates in various Indonesian languages from Sumatra, Borneo, Java, Bali, Sulawesi, Sumba, Flores and Timor. Thus, the name of the finished ikat woven fabric originates from the tali (threads, ropes) being ikat (tied, bound, knotted) before they are being put in celupan (dyed by way of dipping), then berjalin (woven, intertwined) resulting in a berjalin ikat- reduced to ikat.

The introduction of the term ikat into European language is attributed to Rouffaer. Ikat is now a generic English loanword used to describe the process and the cloth itself regardless of where the fabric was produced or how it is patterned.

In Indonesian, the plural of ikat remains ikat. While in English, a suffix plural 's' is commonly added, as in ikats. However, these terms are interchangeable and both are correct.

History

See also: Resist dyeing

Warp ikat traditions in Southeast Asia are believed to have originated in Neolithic weaving traditions (older than at least 6000 BP) somewhere in mainland Asia, and is associated with the Austronesian and Daic-speaking peoples. This is based on a 2012 comparative study on loom technologies, textile patterns, and linguistics. It was spread outwards along with the Austronesian expansion to maritime Southeast Asia, reaching as far as Madagascar by the 1st millennium BC.

Previously, ikat traditions were suggested by some authors to be originally acquired by Austronesians from contact with the Dong Son culture of Vietnam, but this was deemed unlikely in a 2012 study.

Elsewhere, particularly in India and Central Asia, very similar traditions have also developed that are also known as "ikat". These likely developed independently. Uyghurs call it atlas (IPA ) and use it only for woman's clothing. The historical record indicates that there were 27 types of atlas during Qing Chinese occupation. Now there are only four types of Uyghur atlas remaining: qara-atlas, a black ikat used for older women's clothing; khoja'e-atlas, a yellow, blue, or purple ikat used for married women; qizil-atlas, a red ikat used for girls; and Yarkent-atlas, a khan or royal atlas. Yarkent-atlas has more diverse styles; during the Yarkent Khanate (1514–1705), there were ten different styles of Yarkent-atlas.

Types

In warp ikat it is only the warp yarns that are dyed using the ikat technique. The weft yarns are dyed a solid colour. The ikat pattern is clearly visible in the warp yarns wound onto the loom even before the weft is woven in. Warp ikat is, amongst others, produced in Indonesia; more specifically in Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Sumatra by respectively the Dayaks, Torajans and Bataks.

In weft ikat it is the weaving of weft yarn that carries the dyed patterns. Therefore, the pattern only appears as the weaving proceeds. Weft ikats are much slower to weave than warp ikat because the weft yarns must be carefully adjusted after each passing of the shuttle to maintain the clarity of the design.

Double ikat is a technique in which both warp and the weft are resist-dyed prior to weaving. Obviously it is the most difficult to make and the most expensive. Double ikat is only produced in three countries: India, Japan and Indonesia. The double ikat made in Patan, Gujarat in India is the most complicated. Called "patola", it is made using fine silk yarns and many colours. It may be patterned with a small motif that is repeated many times across the length of a six-meter sari. Sometimes the Patan double ikat is pictorial with no repeats across its length. That is, each small design element in each colour was individually tied in the warp and weft yarns. It's an extraordinary achievement in the textile arts. These much sought after textiles were traded by the Dutch East Indies company for exclusive spice trading rights with the sultanates of Indonesia. The double ikat woven in the small Bali Aga village, Tenganan in east Bali in Indonesia reflects the influence of these prized textiles. Some of the Tenganan double ikat motifs are taken directly from the patola tradition. In India, double ikat is also woven in Puttapaka, Nalgonda district, and is called Puttapaka Saree. In Japan, double ikat is woven in the Okinawa islands where it is called tate-yoko gasuri.

Distribution

Ikat is a resist dyeing technique common to many world cultures. It is probably one of the oldest forms of textile decoration. However, it is most prevalent in Indonesia, India and Japan. In South America, Central and North America, ikat is still common in Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala and Mexico, respectively.

In the 19th century, the Silk Road desert oases of Bukhara, Samarkand, Hotan and Kashgar (in what is now Uzbekistan and Xinjiang in Central Asia) were famous for their fine silk Uzbek/Uyghur ikat.

India, Japan, Indonesia and many other Southeast Asian nations including Cambodia, Myanmar, Philippines and Thailand have weaving cultures with long histories of ikat resist dyeing.

Double ikat textiles are still found in India, Japan and Indonesia. In Indonesia, ikat textiles are produced throughout the islands from Sumatra in the west to Timor in the east and Kalimantan and Sulawesi in the north. Ikat is also found in Iran, where the Persian name is daraee. Daraee means wealth, and this fabric is often included in a bride's dowry during wedding ceremonies; the people who bought these fabrics were rich.

Production

Warp ikat

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Ikat created by dyeing the warps (warp ikat) is simpler to make than either weft ikat or double ikat. First the yarns--cotton, silk, wool or other fibres—are wound onto a tying frame. Then they are separated into bundles. As the binding process is very labor-intensive an effort is made to reduce the work to a minimum by folding the thread bundles like in paper dolls and binding a basic ikat motif (BIM) that will be repeated like in paper dolls when the threads are unfolded for weaving after the dyeing is completed. The thread bundles may be folded around a vertical and/or horizontal axis. The bundles may be covered with wax, as in batik. (However, in making batik, the crafts person applies the resist to the finished cloth rather than to the yarns to be woven.) The warp yarns are then wrapped tightly with thread or some other dye-resistant material with the desired pattern so as to prevent unwanted dye penetration. The procedure is repeated, according to the number of colours required to complete the design. Multiple coloration is common, requiring multiple rounds of tying and dyeing. After the dyeing is finished the bindings are removed and the threads are wound onto the loom as the warp (longitudinal yarns). The threads are adjusted to precisely align the motifs and thin bamboo strips are lashed to the threads to prevent them from tangling or slipping out of alignment during weaving.

Some ikat traditions, such as Central Asia's, embrace a blurred aesthetic in the design. Other traditions favour a more precise and more difficult to achieve alignment of the ikat yarns. South American and Indonesian ikat are known for a high degree of warp alignment. Weavers carefully adjust the warp threads when they are placed on the loom so the patterns appear clearly. Thin strips of bamboo are then lashed to the warps to maintain the pattern alignment during weaving.

Patterns are visible in the warp threads even before the weft, a plain colored thread, is woven in. Some warp ikat traditions are designed with vertical-axis symmetry or have a "mirror-image" running along their long centre line. That is, whatever pattern or design is woven on the right is duplicated on the left in reverse order about a central warp thread group. Patterns can be created in the vertical, horizontal or diagonal.

Weft ikat

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Weft ikat (endek in Bali) uses resist-dyeing for the weft yarns. The movement of the weft yarns in the weaving process means precisely delineated patterns are more difficult to achieve. The weft yarn must be adjusted after each passing of the shuttle to preserve the clarity of the patterns.

Nevertheless, highly skilled artisans can produce precise weft ikat. Japanese weavers produce very accurate indigo and white weft ikat with small scale motifs in cotton. Weavers in Odisha, India have replicated fine patterns in weft ikat. In Thailand, weavers make silk sarongs depicting birds and complex geometrical designs in seven-colour weft ikat.

In some precise weft ikat traditions (Gujarat, India), two artisans weave the cloth: one passes the shuttle and the other adjusts the way the yarn lies in the shed.

As the weft is a continuous strand, aberrations or variations in the weaving tension are cumulative. Some weft ikat traditions incorporate this affect into their aesthetic. Patterns become transformed by the weaving process into irregular and erratic designs. Guatemalan ikat is well-noted for its beautiful "blurs."

Double ikat

Further information: Patola sari and kasuri

Double ikat is created by resist-dyeing both the warp and weft prior to weaving. Some sources use the term double ikat only when the warp and weft patterning overlap to form common, identical motifs. If they do not, the result is referred to as compound ikat.

This form of weaving requires the most skill for precise patterns to be woven and is considered the premiere form of ikat. The amount of labour and skill required also make it the most expensive, and many poor quality cloths flood the tourist markets. Indian and Indonesian examples typify highly precise double ikat. Especially prized are the double ikats woven in silk known in India as patola (singular: patolu). These are from Khambat, Gujarat. During the colonial era, Dutch merchants used patola as prestigious trade cloths during the peak of the spice trade.

In Indonesia, double ikat is only woven in the Bali Aga village of Tenganan. These cloths have high spiritual significance. In Tenganan they are still worn for specific ceremonies. Outside Tenganan, geringsing are treasured as they are purported to have magical powers.

The double ikat of Japan is woven in the Okinawa islands and is called tate-yoko gasuri.

Pochampally Saree, a variety from the small village of Andhra Pradesh in Nalgonda district, India, are silk saris woven in the double ikat.

The Puttapaka Saree is made in Puttapaka village, Samsthan Narayanpuram mandal in Nalgonda district, India. It is known for its unique style of silk saris. The symmetric design is over 200 years old. The ikat is warp-based. The Puttapaka Saree is a double ikat.

Before the weaving is done, a manual winding of yarn, called asu, needs to be performed. This process takes up to five hours per sari and is usually done by the womenfolk, who suffer physical strain through constantly moving their hands back and forth over 9000 times for each sari. In 1999 a young weaver, C. Mallesham, developed a machine which automated asu, thus developing a technological solution for a decades-old problem.

Ōshima

Ōshima ikat is a uniquely Japanese ikat. In Amami Ōshima, the warp and weft threads are both used as warp to weave stiff fabric, upon which the thread for the ikat weaving is spot-dyed. Then the mats are unravelled and the dyed thread is woven into Ōshima cloth.

The Ōshima process is duplicated in Java and Bali, and was reserved for ruling royalty, notably Klungkung and Ubud: most especially the dodot cloth semi-cummerbund of Javanese court attire.

Other countries

Cambodia

The Cambodian ikat is a weft ikat woven of silk on a multi-shaft loom with an uneven twill weave, which results in the weft threads showing more prominently on the front of the fabric than the back.

By the 19th century, Cambodian ikat was considered among the finest textiles of the world. When the King of Thailand came to the USA in 1856, he brought fine Cambodian ikat cloth as a gift for President Franklin Pierce. The most intricately patterned of the Cambodian fabrics are the sampot hol — skirts worn by the women — and the pidans — wall hangings used to decorate the pagoda or the home for special ceremonies.

Unfortunately, Cambodian culture suffered massive disruption and destruction during the mid-20th century Indochina wars but most especially during the Khmer Rouge regime. Most weavers were killed and the whole art of Cambodian ikat was in danger of disappearing. Kikuo Morimoto is a prominent pioneer in re-introducing ikat to Cambodia. In 1995, he moved from Japan and located one or two elderly weavers and Khmer Rouge survivors who knew the art and have taught it to a new generation.

Thailand

In Thailand, the local weft ikat type of woven cloth is known as matmi (also spelled 'mudmee' or 'mudmi'). Traditional Mudmi cloth was woven for daily use among the nobility. Other uses included ceremonial costumes. Warp ikat in cotton is also produced by the Karen and Lawa tribal peoples in northern Thailand.

This type of cloth is the favourite silk item woven by Khmer people living in southern Isan, mainly in Surin, Sisaket and Buriram provinces.

Iran

In Iran, ikat, known by the name darayee, has been woven in different areas. In Yazd, there are some workshops that produce it. It is said that this kind of cloth historically used to be included in a bride's dowry. In popular culture, a quote states that people who bought this type of cloth were wealthy.

Latin America

Ikat patterns are common among the Andes peoples, and native people of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela. The Mapuche shawl or poncho of the Huaso cowboys of Chile is perhaps the item best known in the West. Wool and cabuya fibre are the most commonly used.

The Mexican rebozos can be made from silk, wool or cotton and are frequently ikat dyed. These shawls are seen as a part of the Mexican national identity and most women own at least one.

Latin American ikat (Jaspe, as it is known to Maya weavers) textiles are commonly woven on a back-strap loom. Pre-dyed warp threads are a common item in traditional markets- saving the weaver much mess, expense, time and labour. A Latin American innovation which may also be employed elsewhere is to employ a round stick around which warp threads are wrapped in groups, thus allowing more precise control of the desired design. The "corte" is the typical wrap-skirt used worn by Guatemalan women.

India

In India, Ikat art has been present for thousands of years. In some parts of India, ikat processed cloth such as saree and kurtis are very popular, along with bedsheets, door screens, and towels.

Uzbekistan

Ikat is a common weaving technique in Uzbek culture. The Uzbek ikat, locally referred to as abrbandi, is distinguished by its bold and flamboyant patterns. The history of the Uzbek ikat dates back to the 19th century, when it was mastered by the Uzbeks. Since then, it has become an integral part of their cultural identity and an important aspect of traditional clothing.

Accreditation

As of 2010, the government of the Republic of Indonesia announced it would pursue UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage accreditation for its ikat weaving, along with songket and gamelan, having successfully attained this UNESCO recognition for its wayang, batik and the kris.

See also

References

- ^ Buckley, Christopher D. (18 December 2012). "Investigating Cultural Evolution Using Phylogenetic Analysis: The Origins and Descent of the Southeast Asian Tradition of Warp Ikat Weaving". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e52064. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...752064B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052064. PMC 3525544. PMID 23272211.

- "ikat | translate Indonesian to English: Cambridge Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- "ikatan | translate Indonesian to English: Cambridge Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Umesh Charan Patnaik; Aswini Kumar Mishra (1997). Handloom industry in action. M.D. Publications. p. 38. ISBN 9788175330375.

Ghosh & Ghosh 2000 - Ocampo, Ambeth R. (19 October 2011). "History and design in Death Blankets". Inquirer. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- "Ikat History". textileasart.com. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- Ruth Barnes. "Ikat". fashion-history.lovetoknow.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016.

- Abdukerim Raxman; Reweydulla Hemdulla; Sherip Xushtar (1996). Uyghur Örp-Adetliri [Uyghur customs and traditions]. Ürümqi: Shinjang Yashlar Ösümler Neshriyati.

- Michael Möbius; Annette Ster (1998). Bali, Java, Lombok selbst entdecken [Discover Bali, Java, Lombik by yourself]. Regenbogen-Verlag. ISBN 3858620858.

- ^ Hauser-Schaublin, Brigitta; Nabhollz-kartaschoff, Marie-Louise; Ramseyer, Urs (1991). Balinese Textiles. London: British Museum Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-7141-2505-9. OCLC 246736925.

- ^ "History and Culture-Arts and Crafts – Ikat". aponline.gov.in. Government of Andhra Pradesh. Archived from the original on 19 January 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ^ Tomito, Jun; Kasuri, Noriko (1982). Japanese Ikat Weaving: The Techniques of Kasuri. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 7. ISBN 0-7100-9043-9.

- "Dress Codes: Revealing the Jewish Wardrobe". imj.org.il. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- Guy, John (2009). Woven cargoes : Indian Textiles in the East (1st publication 1998). London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 10, 24. ISBN 0500018634. OCLC 40595374.

- Larsen, Jack Lenor (1976). The Dyer's Art ikat, batik, plangi. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 129. ISBN 0442246854.

- Hauser-Schaublin, Nabhollz-kartaschoff & Ramseyer 1991.

- "Textiles". indiaheritage.org. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- "Asu machine to aid weavers of tie and dye sarees". 29 January 2013. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- Gittinger, Mattiebelle; Lefforts, H. Leedom (1992). Textiles and the Thai Experience in South-East Asia. Washington, DC: Textile Museum. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9780874050318.

- Green, Gill. "The Cambodia Weaving Tradition: Little Known Weaving and Loom Artifacts". Arts of Asia. 27 (5): 86–87.

- Gittinger & Lefforts 1992, p. 149. 167.

- Taguchi, Emily. "Cambodia: The Silk Grandmothers". pbs.org. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- Silk at Ban Sawai Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Chusak Sukaranandana. "หัตถกรรมวิจิตรของกลุ่มชาติพันธุ์ ไท-ลาว-เขมร ในประเทศไทย" [Woven cloth, an exquisite handicraft of Thai-Lao-Khmer ethnic groups in Thailand] (PDF). icmr.cru.in.th (in Thai). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2011.

- "دارایی، بافتهای از ابریشم و رنگ". donya-e-eqtesad.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018.

- ^ Waddington, Laverne (3 May 2010). "Backstrap weaving-cross knit looping tutorial and ikat". backstrapweaving.wordpress.com. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- "Central Asian Ikats from the Rau Collection". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- "The Origins and Cultural Significance of Ikat". Alesouk. 28 June 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- "Batik, Wayang, Keris: Jadi Warisan Budaya Dunia". Antara News Indonesia (in Indonesian). 5 February 2010. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

Further reading

- Gillow, John; Dawson, Barry (1995). Traditional Indonesian Textiles. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27820-2.

- Ghosh, G. K.; Ghosh, Shukla (2000). Ikat textiles of India. APH Publishing. ISBN 9788176481670.

- Gibbon, Kate Fitz; Hale, Andrew (1997). Ikat: Silks of Central Asia : the Guido Goldman Collection. Laurence King. ISBN 9781856691017.

- Rogers, Susan; Carey, Hana; Giglio, Patricia; Walters, Martha (2013). Transnational Ikat: An Asian Textile on the Move (Exhibit Catalog, Cantor Art Gallery).

External links

- "Ikat from the University of Washington Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture". washington.edu/burkemuseum. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010.

- Art of Ikat at Europeana. Retrieved February 2012

- "a weaving site that teaches you about ikat". allfiberarts.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2006.

- "Making ikat cloth". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- "The Extraordinary Ikat" – The newsletter of ArtXchange (Summer/Autumn 2003) from Internet Archive

- "South American Ikat". South America. Waddington. 5 March 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- "Ikat techniques adapted for surfwear". nma.gov.au. National Museum of Australia. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

| Clothing identified with Indonesian culture and still worn today | |

| Textiles and weaving | |

| Dyeing | |

| Clothing |

|

| Headgear | |

| Jewelry and ornaments |

|

| Armour | |

| Footwear |

|

| Uzbek clothing | |

|---|---|

| Headgear | |

| Clothing | |

| Footwear |

|

| Stitching and design | |

| Folk costumes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | |||||||||||||

| Asia |

| ||||||||||||

| Europe |

| ||||||||||||

| South America | |||||||||||||

| North America | |||||||||||||

| Oceania | |||||||||||||

| Dyeing | ||

|---|---|---|

| Techniques |  | |

| Types of dyes | ||

| Traditional textile dyes | ||

| History | ||

| Craft dyes | ||

| Reference | ||

| Islamic art | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture |

|  | |||||||||||

| Arts |

| ||||||||||||

| Arts of the book |

| ||||||||||||

| Decoration |

| ||||||||||||

| The garden | |||||||||||||

| Museums, collections |

| ||||||||||||

| Exhibitions | |||||||||||||

| Principles, influences | |||||||||||||

| Culture of Odisha | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dance |

| ||||||

| Music | |||||||

| Play, theatre and puppetry |

| ||||||

| Wedding | |||||||

| Festivals | |||||||

| Martial arts | |||||||

| Handlooms | |||||||

| Arts and Handicrafts |

| ||||||

| Architecture | |||||||

| Calendar (Panjika) | |||||||

| Weaving | ||

|---|---|---|

| Weaves |  | |

| Components | ||

| Tools and techniques | ||

| Types of looms | ||

| Weavers |

| |

| Employment practices | ||

| Mills | ||