| This article has an unclear citation style. The references used may be made clearer with a different or consistent style of citation and footnoting. (December 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. Please help by spinning off or relocating any relevant information, and removing excessive detail that may be against Misplaced Pages's inclusion policy. (December 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In graph theory, the Weisfeiler Leman graph isomorphism test is a heuristic test for the existence of an isomorphism between two graphs G and H. It is a generalization of the color refinement algorithm and has been first described by Weisfeiler and Leman in 1968. The original formulation is based on graph canonization, a normal form for graphs, while there is also a combinatorial interpretation in the spirit of color refinement and a connection to logic.

There are several versions of the test (e.g. k-WL and k-FWL) referred to in the literature by various names, which easily leads to confusion. Additionally, Andrey Leman is spelled `Lehman' in several older articles.

Weisfeiler-Leman-based Graph Isomorphism heuristics

All variants of color refinement are one-sided heuristics that take as input two graphs G and H and output a certificate that they are different or 'I don't know'. This means that if the heuristic is able to tell G and H apart, then they are definitely different, but the other direction does not hold: for every variant of the WL-test (see below) there are non-isomorphic graphs where the difference is not detected. Those graphs are highly symmetric graphs such as regular graphs for 1-WL/color refinement.

1-dimensional Weisfeiler-Leman (1-WL)

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The 1-dimensional graph isomorphism test is essentially the same as the color refinement algorithm (the difference has to do with non-edges and is irrelevant for all practical purposes as it is trivial to see that graphs with a different number of nodes are non-isomorphic). The algorithm proceeds as follows:

Initialization All nodes are initialized with the same color 0

Refinement Two nodes u,v get a different color if a) they had a different color before or b) there is a color c such that u and v have a different number of c-colored neighbors

Termination The algorithm ends if the partition induced by two successive refinement steps is the same.

In order to use this algorithm as a graph isomorphism test, one runs the algorithm on two input graphs G and H in parallel, i.e. using the colors when splitting such that some color c (after one iteration) might mean `a node with exactly 5 neighbors of color 0'. In practice this is achieved by running color refinement on the disjoint union graph of G and H. One can then look at the histogram of colors of both graphs (counting the number of nodes after color refinement stabilized) and if they differ, this is a certificate that both graphs are not isomorphic.

The algorithm terminates after at most rounds where is the number of nodes of the input graph as it has to split one partition in every refinement step and this can happen at most until every node has its own color. Note that there are graphs for which one needs this number of iterations, although in practice the number of rounds until terminating tends to be very low (<10).

The refinement of the partition in each step is by processing for each node its label and the labels of its nearest neighbors. Therefore WLtest can be viewed as a message passing algorithm which also connects it to graph neural networks.

Higher-order Weisfeiler-Leman

This is the place where the aforementioned two variants of the WL algorithm appear. Both the k-dimensional Weisfeiler-Leman (k-WL) and the k-dimensional folklore Weisfeiler-Leman algorithm (k-FWL) are extensions of 1-WL from above operating on k-tuples instead of individual nodes. While their difference looks innocent on the first glance, it can be shown that k-WL and (k-1)-FWL (for k>2) distinguish the same pairs of graphs.

k-WL (k>1)

Input: a graph G = (V,E) # initialize for all repeat for all until (both colorings induce identical partitions of ) return

Here the neighborhood of a k-tuple is given by the set of all k-tuples reachable by exchanging the i-th position of : The atomic type of a tuple encodes the edge information between all pairs of nodes from . For example, a 2-tuple has only two possible atomic types, namely the two nodes may share an edge, or they do not. Note that if the graph has multiple (different) edge relations or additional node features, membership in those is also represented in .

The key idea of k-WL is to expand the neighborhood notion to k-tuples and then effectively run color refinement on the resulting graph.

k-FWL (k>1)

Input: a graph G = (V,E) # initialize ) for all repeat for all until (both colorings induce identical partitions of ) return

Here is the tuple where the i-th position is exchanged to be .

Note that there is one major difference between k-WL and k-FWL: k-FWL checks what happens if a single node w is placed at any position of the k-tuple (and then computes the multiset of these k-tuples) while k-WL looks at the multisets that you get when changing the i-th component only of the original k-tuple. It then uses all those multisets in the hash that computes the new color.

It can be shown (although only through the connection to logic) that k-FWL and (k+1)-WL are equivalent (for ). Since both algorithms scale exponentially in k (both iterate over all k-tuples), the use of k-FWL is much more efficient than using the equivalent (k+1)-WL.

Examples and Code for 1-WL

Code

# ALGORITHM WLpairs

# INPUT: two graphs G and H to be tested for isomorphism

# OUTPUT: Certificates for G and H and whether they agree

U = combineTwo(G, H)

glabels = initializeLabels(U) # dictionary where every node gets the same label 0

labels = {} # dictionary that will provide translation from a string of labels of a node and its neighbors to an integer

newLabel = 1

done = False

while not(done):

glabelsNew = {} # set up the dictionary of labels for the next step

for node in U:

label = str(glabels) + str( for x in neighbors of node].sort())

if not(label in labels): # a combination of labels from the node and its neighbors is encountered for the first time

labels = newLabel # assign the string of labels to a new number as an abbreviated label

newLabel += 1 # increase the counter for assigning new abbreviated labels

glabelsNew = labels

if (number of different labels in glabels) == (number of different labels in glabelsNew):

done = True

else:

glabels = glabelsNew.copy()

certificateG = certificate for G from the sorted labels of the G-part of U

certificateH = certificate for H from the sorted labels of the H-part of U

if certificateG == certificateH:

test = True

else:

test = False

Here is some actual Python code which includes the description of the first examples.

g5_00 = {0: {1, 2, 4}, 1: {0, 2}, 2: {0, 1, 3}, 3: {2, 4}, 4: {0, 3}}

g5_01 = {0: {3, 4}, 1: {2, 3, 4}, 2: {1, 3}, 3: {0, 1, 2}, 4: {0, 1}}

g5_02 = {0: {1, 2, 4}, 1: {0, 3}, 2: {0, 3}, 3: {1, 2, 4}, 4: {0, 3}}

def combineTwo(g1, g2):

g = {}

n = len(g1)

for node in g1:

s = set()

for neighbor in g1:

s.add(neighbor)

g = s.copy()

for node in g2:

s = set()

for neighbor in g2:

s.add(neighbor + n)

g = s.copy()

return g

g = combineTwo(g5_00, g5_02)

labels = {}

glabels = {}

for i in range(len(g)):

glabels = 0

glabelsCount = 1

newlabel = 1

done = False

while not (done):

glabelsNew = {}

glabelsCountNew = 0

for node in g:

label = str(glabels)

s2 =

for neighbor in g:

s2.append(glabels)

s2.sort()

for i in range(len(s2)):

label += "_" + str(s2)

if not (label in labels):

labels = newlabel

newlabel += 1

glabelsCountNew += 1

glabelsNew = labels

if glabelsCount == glabelsCountNew:

done = True

else:

glabelsCount = glabelsCountNew

glabels = glabelsNew.copy()

print(glabels)

g0labels =

for i in range(len(g0)):

g0labels.append(glabels)

g0labels.sort()

certificate0 = ""

for i in range(len(g0)):

certificate0 += str(g0labels) + "_"

g1labels =

for i in range(len(g1)):

g1labels.append(glabels)

g1labels.sort()

certificate1 = ""

for i in range(len(g1)):

certificate1 += str(g1labels) + "_"

if certificate0 == certificate1:

test = True

else:

test = False

print("Certificate 0:", certificate0)

print("Certificate 1:", certificate1)

print("Test yields:", test)

Examples

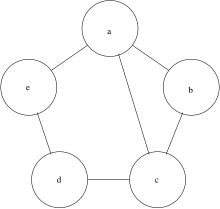

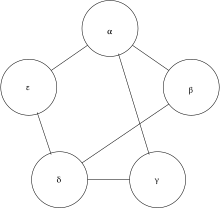

The first three examples are for graphs of order 5.

| Graph G0 | Graph G1 | Graph G2 |

|---|---|---|

WLpair takes 3 rounds on 'G0' and 'G1'. The test succeeds as the certificates agree.

WLpair takes 4 rounds on 'G0' and 'G2'. The test fails as the certificates disagree. Indeed 'G0' has a cycle of length 5, while 'G2' doesn't, thus 'G0' and 'G2' cannot be isomorphic.

WLpair takes 4 rounds on 'G1' and 'G2'. The test fails as the certificates disagree. From the previous two instances we already know .

| G0 vs. G1 | G0 vs. G2 | G1 vs. G2 |

|---|---|---|

Indeed G0 and G1 are isomorphic. Any isomorphism must respect the components and therefore the labels. This can be used for kernelization of the graph isomorphism problem. Note that not every map of vertices that respects the labels gives an isomorphism. Let and be maps given by resp. . While is not an isomorphism constitutes an isomorphism.

When applying WLpair to G0 and G2 we get for G0 the certificate 7_7_8_9_9. But the isomorphic G1 gets the certificate 7_7_8_8_9 when applying WLpair to G1 and G2. This illustrates the phenomenon about labels depending on the execution order of the WLtest on the nodes. Either one finds another relabeling method that keeps uniqueness of labels, which becomes rather technical, or one skips the relabeling altogether and keeps the label strings, which blows up the length of the certificate significantly, or one applies WLtest to the union of the two tested graphs, as we did in the variant WLpair. Note that although G1 and G2 can get distinct certificates when WLtest is executed on them separately, they do get the same certificate by WLpair.

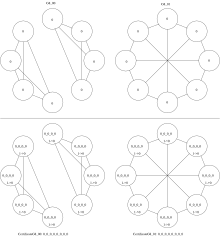

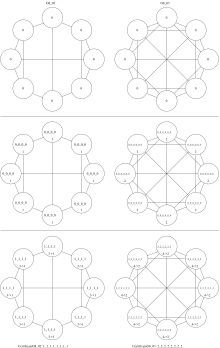

The next example is about regular graphs. WLtest cannot distinguish regular graphs of equal order, but WLpair can distinguish regular graphs of distinct degree even if they have the same order. In fact WLtest terminates after a single round as seen in these examples of order 8, which are all 3-regular except the last one which is 5-regular.

All four graphs are pairwise non-isomorphic. G8_00 has two connected components, while the others do not. G8_03 is 5-regular, while the others are 3-regular. G8_01 has no 3-cycle while G8_02 does have 3-cycles.

| WLtest applied to four regular graphs of order 8. | WLpair applied to G8_00 and G8_01 of same degree. | WLpair applied to G8_02 and G8_03 of distinct degree. |

|---|---|---|

Another example of two non-isomorphic graphs that WLpair cannot distinguish is given here.

Applications

The theory behind the Weisfeiler Leman test is applied in graph neural networks.

Weisfeiler Leman graph kernels

In machine learning of nonlinear data one uses kernels to represent the data in a high dimensional feature space after which linear techniques such as support vector machines can be applied. Data represented as graphs often behave nonlinear. Graph kernels are method to preprocess such graph based nonlinear data to simplify subsequent learning methods. Such graph kernels can be constructed by partially executing a Weisfeiler Leman test and processing the partition that has been constructed up to that point. These Weisfeiler Leman graph kernels have attracted considerable research in the decade after their publication. They are also implemented in dedicated libraries for graph kernels such as GraKeL.

Note that kernels for artificial neural network in the context of machine learning such as graph kernels are not to be confused with kernels applied in heuristic algorithms to reduce the computational cost for solving problems of high complexity such as instances of NP-hard problems in the field of complexity theory. As stated above the Weisfeiler Leman test can also be applied in the later context.

See also

References

- ^ Huang, Ningyuan; Villar, Soledad (2022), "A Short Tutorial on the Weisfeiler-Lehman Test and Its Variants", ICASSP 2021 - 2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 8533–8537, arXiv:2201.07083, doi:10.1109/ICASSP39728.2021.9413523, ISBN 978-1-7281-7605-5, S2CID 235780517

- Weisfeiler, B. Yu.; Leman, A. A. (1968). "A Reduction of a Graph to a Canonical Form and an Algebra Arising during This Reduction" (PDF). Nauchno-Technicheskaya Informatsia. 2 (9): 12–16. Retrieved 2023-10-28.

- Bieber, David (2019-05-10). "The Weisfeiler-Lehman Isomorphism Test". Retrieved 2023-10-28.

- Kiefer, Sandra (2020). Power and limits of the Weisfeiler-Leman algorithm (PhD thesis). RWTH Aachen University. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- Bronstein, Michael (2020-12-01). "Expressive Power Of Graph Neural Networks And The Weisfeiler-Lehman Test". Retrieved 2023-10-28.

- Shervashidze, Nino; Schweitzer, Pascal; Van Leeuwen, Erik Jan; Mehlhorn, Kurt; Borgwardt, Karsten M. (2011). "Weisfeiler-lehman graph kernels". Journal of Machine Learning Research. 12 (9): 2539−2561. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- "Weisfeiler Lehman Framework". 2019. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

This Weisfeiler Lehman framework operates on top of existing graph kernels and is inspired by the Weisfeiler-Lehman test of graph isomorphism .

rounds where

rounds where  is the number of nodes of the input graph as it has to split one partition in every refinement step and this can happen at most until every node has its own color. Note that there are graphs for which one needs this number of iterations, although in practice the number of rounds until terminating tends to be very low (<10).

is the number of nodes of the input graph as it has to split one partition in every refinement step and this can happen at most until every node has its own color. Note that there are graphs for which one needs this number of iterations, although in practice the number of rounds until terminating tends to be very low (<10).

for all

for all  repeat

repeat

for all

for all

until

until  (both colorings induce identical partitions of

(both colorings induce identical partitions of  )

return

)

return

of a k-tuple

of a k-tuple  is given by the set of all k-tuples reachable by exchanging the i-th position of

is given by the set of all k-tuples reachable by exchanging the i-th position of  The atomic type

The atomic type  of a tuple encodes the edge information between all pairs of nodes from

of a tuple encodes the edge information between all pairs of nodes from  ) for all

) for all  for all

for all

until

until  is the tuple

is the tuple  .

.

). Since both algorithms scale exponentially in k (both iterate over all k-tuples), the use of k-FWL is much more efficient than using the equivalent (k+1)-WL.

). Since both algorithms scale exponentially in k (both iterate over all k-tuples), the use of k-FWL is much more efficient than using the equivalent (k+1)-WL.

.

.

and

and  be maps given by

be maps given by  resp.

resp.  . While

. While  is not an isomorphism

is not an isomorphism  constitutes an isomorphism.

constitutes an isomorphism.