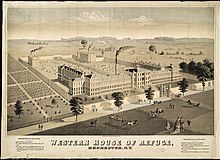

The prison as it appeared in 1870. The prison as it appeared in 1870. | |

| Other name | State Industrial School, Industry Residential Center |

|---|---|

| Established | 1849 |

| Mission | Juvenile detention |

| Owner | New York State Office of Children and Family Services |

| Location | Industry, New York, United States |

| Website | https://ocfs.ny.gov/programs/rehab/facilities/industry.php |

The Western House of Refuge was a prison for children in Rochester, New York founded in the mid-1800's that was the first state managed reformatory in the United States. In the 1880's, the prison was changed into a vocational school known as the State Industrial School. In the early 1900's, the school would move to Industry, New York, where it now operates as the Industry Residential Center run by the state Office of Children and Family Services.

Founding

In the 1840's, legislators in New York State sought to better address the issue of juvenile detention. At the time, children were "thrown in" with adults in the state's many jails and prisons. While the state had created the House of Refuge to address this problem in 1824, the Manhattan-based institution "did not serve" Western New York. In 1846, the legislature passed a bill creating a Western House of Refuge run by a superintendent overseen by a fifteen-member board. Upstate courts were required to send convicted child felons to the new institution; they were also given the discretion to incarcerate children who had committed minor offenses or were simply homeless. At the House, children were supposed to work eight-hour days on behalf of farms and local industries, while spending their non-working hours learning vocational and literacy skills.

In 1849, the House formally opened on a 42-acre plot of land just north of the growing city of Rochester. The prison population quickly grew from 50 to over 400. In 1880, the local press called the House, which was managed by social and political elites in Rochester, "one of the best managed institutions of its kind in the country."

Scandal

In 1882, the institution's management asked the state to pass a bill that would drastically expand the House's size. In a move that made front page headlines across New York, the head of the state Board of Charities opposed the legislation, calling the House "essentially a prison" that "doomed" boys and girls to a life of child labor. The Buffalo Evening News would later report that it was an open secret that the House's managers had "wholly abandoned education so that contractors may obtain labor from helpless children." When the expansion bill failed, the House to hire a team of investigators, who - while finding "serious defects" in the institution - blamed these defects on poor performing employees, who were subsequently terminated.

Unconvinced by the House's attempt to police itself, the New York State Assembly conducted an investigation in 1884. The legislators found that the institution was a "half prison" paired with a "money-making" operation that preyed on a population of children whose sole "crimes" were often nothing but homelessness or insolence. Five hundred boys as young as eight, who were allegedly being taught skills to "reform" them, were forced to spend most of their days as contract laborers, making shoes and garments for local businesses. After attending perfunctory night "classes," the children were caged in "exceedingly repulsive" cells that lacked toilets, were bathed once a week in two tubs shared by all other boys, and were subject to "excessive," "frequent," and "cruel" punishments that included beatings, forced starvation, solitary confinement, and transfers to adult prisons. The Assembly concluded that the House, which was instilling "evil" and "corruption" into the children it housed, needed "radical" change. The major recommendation was to transform the institution into a vocational school.

Reform

In the wake of the scandal, the state and local leaders worked to drastically overhaul the school and the juvenile detention system in New York as a whole. In the 1880's and 1890's, the state banned contract labor by juvenile inmates across the state, while the leaders of the House created a parole system, stopped accepting children who had not committed felonies, segregated children on the basis of age, and banned corporal punishment. The school was renamed as the "State Industrial School," with its focus shifting from profit-based contract labor to skills-based training in agricultural life and vocations like masonry.

In the early 1900's, the school was relocated from Rochester's urban area to its rural surroundings in Rush, New York. (What replaced it would be one of the country's first state-run vocational schools, which is now known as Edison Technology & Career High School). On a 1400-acre site, the state built 20 cottages designed to house 25 children each. Inmates would complete schoolwork at their cottages before performing farm chores centering around a nearby barn. In the 1930's, the School added counseling services and an industrial arts building, though it remained a prison, where inmates regularly attempted to secure their freedom through escape.

While priding themselves on a more "progressive" vision of incarceration, in the face of the labor shortages of World War II, the School's leaders returned to the old practice of hiring out children as farm labor. Children were imprisoned for things like "deserting home," being "ungovernable," and merely being seen as a "neglected child." They were forced to perform all their tasks, including the burial of their fellow inmates, in "paramilitary formation." Children who died at the School - sometimes in attempts to escape, sometimes as a result of "farming accidents" - were buried in the nearby woods with plastic headstones.

Today

What was once the Western House of Refuge is now known as the Industry Residential Center, a 120-acre prison for children enclosed by barbed wire. As one journalist put it, "there is nothing nurturing about the place. Everything about it is depressing." Children age 10 to 17 are sent to Industry from family court "for infractions ranging from assault to drug possession," and spend "less than a year in confinement."

Children spend as much as 20 hours a week working on things like growing vegetables and raising fish. While state rules ban the prison from selling the fruits of its children's labor, "friendly transactions" allow local chefs to obtain food grown by inmates in exchange for a "donation." Prison leaders say the children's labor is "not so much about growing food as building character"; inmates, on the other hand, say they do the work so they can "go home." In 2021, the Monroe County public defender called the prison's approach to COVID-19 among inmates "unconscionable" and "undoubtedly contributing to the trauma those children suffered by being incarcerated."

References

- ^ "New York State Agricultural and Industrial School. - Social Networks and Archival Context". snaccooperative.org. Retrieved 2022-09-06.

- "Helping Themselves". The Democrat & Chronicle (Rochester, NY). December 23, 1880. p. 2.

- Rochester Public Library (September 6, 2022). "The Western House of Refuge".

- ^ "Refuge Verdict; The Report of the Investigating Committee". The Democrat & Chronicle (Rochester, NY). April 16, 1884. p. 3.

- "The Western House of Refuge". Buffalo Weekly Courier. April 26, 1882. p. 1.

- "Untitled Editorial". The Buffalo Sunday Morning News. June 1, 1884. p. 1.

- "An Investigating Committee Criticises a House of Refuge". The New York Times. December 16, 1883. p. 1.

- ^ "NYCHS presents excerpts from Blake McKelvey's Rochester Penal History institutional origins". www.correctionhistory.org. Retrieved 2022-09-06.

- ^ Andreatta, David (July 13, 2014). "Neglected in Life, Abandoned in Death". The Democrat & Chronicle (Rochester, NY). p. 1.

- Murphy, Justin (February 26, 2014). "Teach a Boy to Fish . . ". The Democrat & Chronicle (Rochester, NY). p. 1.

- Fitzgerald, Michael (2021-05-27). "In New York Youth Lockups, Many Quarantines, Few Tests". The Imprint. Retrieved 2022-09-07.

Categories: