| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Wire spring relay" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

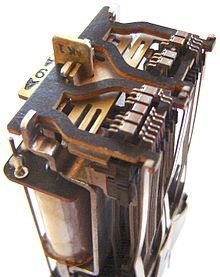

A wire spring relay is a type of relay, that has springs made from drawn wires of nickel silver, rather than cut from flat sheet metal as in the flat-spring relay. This class of relays provided manufacturing and operating advantages over previous designs. Wire spring relays entered mass production in the early 1950s.

Wire spring relays were the most suitable relays for logic and computing functions. They were used extensively in markers, which were special purpose computers used to route calls in crossbar switch central offices.

Wire spring relays were primarily manufactured by the Western Electric Company for use in electromechanical telephone exchanges in the Bell System. The design was licensed for use around the world, and was commonplace in Japan.

Manufacturing of wire spring relays greatly declined in the late 20th century due to the introduction of digital electronic switching systems that used them in very small numbers.

Description

A relay has two major parts, the electromagnet and the contacts. The electromagnet may have a resistance between 15 and 200 ohms, and is often designed to operate satisfactorily at a common telephony voltage, such as 24 or 48 volts.

The electromagnet can also be modified by the insertion of metallic slugs (lumps) to create a brief delay before pulling in the contacts (slow operate), or hold the contacts in place briefly after power is removed (slow release).

A wire spring relay typically has many individual contacts. Each contact is either a fixed contact, which does not move, or is a moving contact, and is made from a short piece of wire. The contact points are made from small blocks of precious metals, such as palladium, which are spot-welded to the wire springs. The majority of the wire spring relays manufactured in the 1960s had twelve fixed contacts. A normally open (make) contact, a normally closed (break) contact, or both can be provided for each fixed contact. A moving contact consists of two wires projecting out of the base of the relay, bent slightly inwards in order to exert pressure against the armature.

The moving contacts are held away from the fixed contacts by a phenolic paper pattern called a "card". By changing the depth of the cuts on this form, the contacts can be made to make or break earlier or later than others. This can be used to transfer electrical control or power from one source to another by having a "make" contact operate before the corresponding "break" contact does.

For the stored program control exchanges of the early 1970s, many relays were made with steel cores that remained magnetized after current ceased to flow in the winding. This magnetic latching feature, different from the use of slugs to delay relay operation, was used in the arrays of reed relays that switched connection paths in the early models of electronic switching systems. A miniature wire spring relay was also produced, starting in approximately 1974 as part of the 1A redesign of the 1ESS switch.

Use in logic

Wire spring relays could be interconnected to create the typical combinational circuits that were later used in silicon design.

The contacts of one or more relays can be used to drive the coil of another relay. To make an OR gate for example, the contacts of several input relays may be placed in parallel circuits and used to drive the electromagnet of a third relay. This, along with series circuits and more complicated schemes such as multiply wound electromagnets, allows the creation of AND gates, OR gates and Inverters (using the normally closed contact on a relay). Using these simple circuits in combination with De Morgan's Laws, any combinational function can be created using relays.

When output wires are fed back as inputs, the result is a feedback loop or sequential circuit that has the potential to consider its own history. Such circuits are often suitable as memories.

Use as memory

Memory circuits in the form of latches can also be created by having a relay contact complete the circuit of its own coil when operated. The relay will then latch and store the state to which it was driven. With this capability, relays were used to create special purpose computers for telephone switches in the 1930s. Starting in the 1950s, these designs were converted to wire spring relays, making them faster and more reliable. The majority of wire spring relays were used in 5XB switches.

Most wire spring relays have a permalloy core, and require continuous power to maintain state. Some have a steel core, making them magnetically latching relays, similar to the ferreed and remreed types of reed relay.

Reed relays are smaller and cheaper, thus better suited to data storage. They were used in conjunction with wire spring relays, for example to store digits for sending to other crossbar switching offices. In a multi-frequency sender (the part of a switch which sends routing information about outgoing calls over trunk lines), for example, wire spring relays direct the dialed digits one at a time from reed relay packs to frequency generators, under sequential control of logic implemented with wire spring relays. At the other end, similar relays steered the incoming digits from the tone decoder to a reed relay memory. In such uses, two-out-of-five codes and similar schemes checked for errors at both ends.

Use in carrier systems

Wire spring relays were also incorporated into the signaling channel units of carrier systems.

References

- Arthur C. Keller, A New General Purpose Relay for Telephone Switching Systems, Bell System Technical Journal, v.31(6), 1023 (November 1952)

- A.L. Quinlan, Automatic Contact Welding in Wire Spring Relay Manufacture, Bell System Technical Journal, v.33(4), 897 (July 1954)

- H. Harte, Reproducing Wire-Spring Relay Cards

- A. Feiner, The Ferreed, Bell System Technical Journal, v.43(1), 1 (January 1964)