This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Measurement of wow and flutter is carried out on audio tape machines, cassette recorders and players, and other analog recording and reproduction devices with rotary components (e.g. movie projectors, turntables (vinyl recording), etc.) This measurement quantifies the amount of 'frequency wobble' (caused by speed fluctuations) present in subjectively valid terms. Turntables tend to suffer mainly slow wow. In digital systems, which are locked to crystal oscillators, variations in clock timing are referred to as wander or jitter, depending on speed.

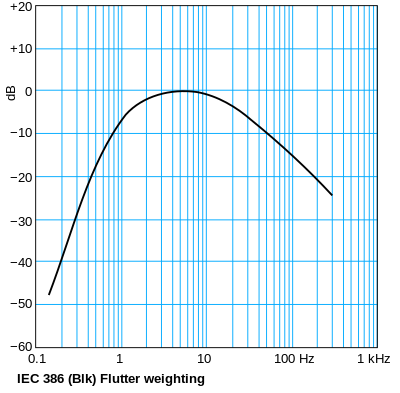

While the terms wow and flutter used to be used separately (for wobbles at a rate below and above 4 Hz respectively), they tend to be combined now that universal standards exist for measurement which take both into account simultaneously. Listeners find flutter most objectionable when the actual frequency of wobble is 4 Hz, and less audible above and below this rate. This fact forms the basis for the weighting curve shown here. The weighting curve is misleading, inasmuch as it presumes inaudibility of flutters above 200 Hz, when actually faster flutters are quite damaging to the sound. A flutter of 200 Hz at a level of -50db will create 0.3% intermodulation distortion, which would be considered unacceptable in a preamp or amplifier.

Measurement techniques

Measuring instruments use a frequency discriminator to translate the pitch variations of a recorded tone into a flutter waveform, which is then passed through the weighting filter, before being full-wave rectified to produce a slowly varying signal which drives a meter or recording device. The maximum meter indication should be read as the flutter value.

The following standards all specify the weighting filter shown above, together with a special slow-quasi-peak full-wave rectifier designed to register any brief speed excursions. As with many audio standards, these are identical derivatives of a common specification.

- IEC 386

- DIN45507

- BS4847

- CCIR 409-3

- AES6-2008

Measurement is usually made on a 3.15 kHz (or sometimes 3 kHz) tone, a frequency chosen because it is high enough to give good resolution, but low enough not to be affected by drop-outs and high-frequency losses. Ideally, flutter should be measured using a pre-recorded tone free from flutter. Record-replay flutter will then be around twice as high as pre-recorded, because worst case variations will add during recording and playback. When a recording is played back on the same machine it was made on, a very slow change from low to high flutter will often be observed, because any cyclic flutter caused by capstan rotation may go from adding to cancelling as the tape slips slightly out of synchronism. A good technique is to stop the tape from time to time and start it again. This will often result in different readings as the correlation between record and playback flutter shifts. On well maintained, precise machines, it may be difficult to procure a reference tape with higher tolerances. Therefore, a record-playback test using the stop-start technique, can be, for practical purposes, the best that can be accomplished.

Audible effects

Wow and flutter are particularly audible on music with oboe, string, guitar, flute, brass, or piano solo playing. While wow is perceived clearly as pitch variation, flutter can alter the sound of the music differently, making it sound ‘cracked’ or ‘ugly’. A recorded 1 kHz tone with a small amount of flutter (around 0.1%) can sound fine in a ‘dead’ listening room, but in a reverberant room constant fluctuations will often be clearly heard. These are the result of the current tone ‘beating’ with its echo, which since it originated slightly earlier, has a slightly different pitch. What is heard is quite pronounced amplitude variation, which the ear is very sensitive to. This probably explains why piano notes sound ‘cracked’. Because they start loud and then gradually tail off, piano notes leave an echo that can be as loud as the dying note that it beats with, resulting in a level that varies from complete cancellation to double-amplitude at a rate of a few Hz: instead of a smoothly dying note we hear a heavily modulated one. Oboe notes may be particularly affected because of their harmonic structure. Another way that flutter manifests is as a truncation of reverb tails. This may be due to the persistence of memory with regard to spatial location based on early reflections and comparison of Doppler effects over time. The auditory system may become distracted by pitch shifts in the reverberation of a signal that should be of fixed and solid pitch.

The term "flutter echo" is used in relation to a particular form of reverberation that flutters in amplitude. It has no direct connection with flutter as described here, though the mechanism of modulation through cancellation may have something in common with that described above.

Equipment performance

- Professional tape machines can achieve a weighted flutter figure of around 0.02%, which is considered inaudible.

- High end cassette decks struggle to manage around 0.08% weighted, which is still audible under some conditions.

- Digital music players such as CD, DAT, or MP3 use electronic clocks to govern the speed of replay. The circuits used to control these frequencies do permit a very small amount of flutter (usually termed jitter), but the level is far below that which the human ear can discern.

- The linear sound track on VCR video recorders has much higher wow and flutter than the VHS-HiFi high fidelity track which is contained within the video signal.

Absolute speed

Absolute speed error causes a change in pitch, and it is useful to know that a semitone in music represents a 6% frequency change. This is because Western music uses the ‘equal temperament scale' based on a constant geometric ratio between twelve notes; and the twelfth root of 2 is 1.05946. Anyone with a good musical ear can detect a pitch change of around 1%, though an error of up to 3% is likely to go unnoticed, except by those few with ‘absolute pitch’. Most ‘movie’ films shown on European television are sped up by 4.166% because they were shot at 24 frames per second, but are scanned at 25 frames per second to match the PAL standard of 25 frame/s 50 field/s. This causes a noticeable increase in pitch on voices, which often brings surprised comment from the actors themselves when they hear their performance on video. It can also frustrate attempts to play along with film music, which is closer to a semitone sharp than its intended pitch. Recently, digital pitch correction has been applied to some films, which corrects the pitch without altering lip-sync, by adding in extra cycles of sound. This has to be regarded as a form of distortion, as there is no way to change the pitch of a sound without also slowing it down that does not change the waveform itself.

Scrape flutter

High-frequency flutter, above 100 Hz, can sometimes result from tape vibrating as it passes over a head (or other non-rotating element in the tape path), as a result of rapidly interacting stretching in the tape and stick-slip at the head. This is termed 'scrape flutter'. It adds a roughness to the sound that is not typical of wow & flutter, and damping devices or heavy rollers are sometimes employed on professional tape machines to reduce or prevent it. Scrape flutter measurement requires special techniques, often using a 10 kHz tone.

See also

- Audio quality measurement

- Noise measurement

- Headroom

- Rumble measurement

- ITU-R 468 noise weighting

- A-weighting

- Weighting filter

- Equal-loudness contour

- Fletcher–Munson curves

- Flutter (electronics and communication)

- Wow (recording)