Bay mud consists of thick deposits of soft, unconsolidated silty clay, which is saturated with water; these soil layers are situated at the bottom of certain estuaries, which are normally in temperate regions that have experienced cyclical glacial cycles.

Example locations are Cape Cod Bay, Chongming Dongtan Reserve in Shanghai, China, Banc d'Arguinpreserve in Mauritania, The Bristol Channel in the United Kingdom, Mandø Island in the Wadden Sea in Denmark, Florida Bay, San Francisco Bay, Bay of Fundy, Casco Bay, Penobscot Bay, and Morro Bay.

Bay mud manifests low shear strength, high compressibility and low permeability, making it hazardous to build upon in seismically active regions like the San Francisco Bay Area. Typical bulk density of bay mud is approximately 1.3 grams per cubic centimetre.

Bay muds often have a high organic content, consisting of decayed organisms at lower depths, but may also contain living creatures when they occur at the upper soil layer and become exposed by low tides; then, they are called mudflats, an important ecological zone for shorebirds and many types of marine organisms. Great attention was not given to the incidence of deeper bay muds until the 1960s and 1970s when development encroachment on certain North American bays intensified, requiring geotechnical design of foundations.

Bay mud has its own official geological abbreviation: the designation for Quaternary older bay mud is Qobm and the acronym for Quaternary younger bay mud is Qybm. An alluvial layer is often found overlying the older bay mud.

In relation to shipping channels, it is often necessary to dredge bay bottoms and barge the excavated material to an alternate location. In this case, chemical analyses are usually performed on the bay mud to determine whether there are elevated levels of heavy metals, PCBs or other toxic substances known to accumulate in a benthic environment. It is not uncommon to dredge the same channel repeatedly (over a span of ten to thirty years) since further settling sediments are prone to redeposit on an open estuarine valley floor.

Depositional scenarios

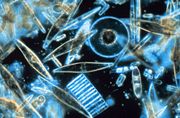

Bay muds originate from two generalized sources. First alluvial deposits of clays, silts and sand occur from streams tributary to a given bay. The extent of these unconsolidated interglacial deposits typically ranges throughout a given bay to the extent of the historical perimeter marshlands. Second, in periods of high glaciation, deposits of silts, sands and organic plus inorganic detritus (e.g. decomposition of estuarine diatoms) may form a separate distinct layer. Thus bay muds are important time records of glacial activity and streamflow throughout the Quaternary period.

Some depositional formation is quite recent, such as in the case of Florida Bay, where much of the bay mud has accumulated since 2000 BCE, and consists of primarily decayed organic material. In the case of Florida Bay these bay muds can accrete as much as 0.5 to 2.0 centimeters per annum, although the dynamic equilibrium of erosion, wave action redistribution and deposition complicate the net rate of layer growth. In the case of the Bristol Channel in the United Kingdom bay, mud formation has been occurring at least since the Eemian Stage (known as the Sangamonian Stage in North America), or about 130,000 years ago. In other cases such as with San Francisco Bay, deposition has been interrupted by sea-level changes, and strata of vastly different vintages are found. In the San Francisco Bay Area, these are called Young bay mud and Older bay mud by geologists. Human activities can also affect deposition; close to half of the Young Bay Mud in San Francisco Bay was placed in the period 1855–1865, as a result of placer mining in the Sierra Nevada foothills.

Geotechnical factors

Construction on bay mud sites is difficult because of the soil's low strength and high compressibility. Very lightweight buildings can be constructed on bay mud sites if there is a thick enough layer of non-bay-mud soil above the bay mud, but buildings which impose significant loads must be supported on deep foundations bearing on stiffer layers below the bay mud, or obtaining support from friction in the bay mud. Even with deep foundations, difficulties arise because the surrounding ground will likely settle over time, potentially damaging utility connections to the building and causing the entryway to sink below street level.

A number of notable buildings have been constructed over bay muds, typically employing special mitigation designs to withstand seismic risks and settlement issues. Complicating design issues, fill (beginning about 1850 CE) is sometimes found deposited on the surface level. For example, the Dakin Building in Brisbane, California, was designed in 1985 to sit on piles 150 feet deep, anchoring to the Franciscan formation, below the bay muds and through an upper fill layer. Furthermore, the structure's entrance ramp has been set on a giant hinge to allow the surrounding land to settle, while the building absolute height remains constant. The Crowne Plaza high-rise hotel in Burlingame, California was also designed to sit over bay muds, as was the Westin Hotel in Millbrae, California, and Trinity Church in Boston's Copley Square. Indeed, Boston's entire Back Bay district is named for the tidal bay that it now covers. Logan International Airport and the San Francisco International Airport are also constructed over bay mud.

Mudflats

Main article: MudflatWhen the mud layer is exposed at the tidal fringe, mudflats result affording a unique ecotone that affords numerous shorebird species a safe feeding and resting habitat. Because the muds function much like quicksand, heavier mammalian predators not only cannot gain traction for pursuit, but would actually become trapped in the sinking muds. The muds are also an important substrate for primary marsh productivity including eelgrass, cordgrass and pickleweed. Furthermore, they are home to a large variety of molluscs and estuarine arthropods. Richardson Bay, for example, exposes one third of its areal extent as mudflat at low tide, which hosts a productive eelgrass expanse and also a large shorebird community.

Mammals such as the Harbor seal may use mudflats to haul out of estuary waters; however, larger mammals such as humpback whales may become accidentally stranded at low tides. Note that normally humpback whales do not frequent estuaries containing mudflats, but at least one errant whale, publicized by the media as Humphrey the humpback whale, became stuck on a mudflat in San Francisco Bay at Sierra Point in Brisbane, California.

Worldwide occurrences

Bay muds occur in bays and estuaries throughout the temperate regions of the world. In North America, prominent instances are: (a) the Stellwagen Bank formed 16,000 to 9000 BCE by glaciation of Cape Cod Bay in Massachusetts, (b) Florida Bay, (c) in California Morro Bay and San Francisco Bay and (d) Knik & Turnagain Arms in Anchorage, Alaska. In the United Kingdom large bay mud occurrences are found at Morecambe Bay, Bridgwater Bay and Bristol Bay. Straddling Denmark, the Netherlands and Germany is the Wadden Sea, a major formation underlain by bay muds.

In Asia the Chongming Dongtan Nature Reserve in Shanghai, China, is an example of a large scale bay mud formation. The Atlantic coast of Africa holds the Banc d'Arguin, a World Heritage nature preserve in the country of Mauritania. Banc d'Arguin is a vast area underlain by bay mud.

Regulatory issues and actions

When building on top of bay mud layers or when dredging estuary bottoms, a variety of regulatory frameworks may arise. Normally in the United States, an Environmental Impact Report as well as a geotechnical investigation are conducted precedent to any major construction over bay mud. Combined, these reports have developed much of the data base extant on bay mud characteristics, frequently yielding original field data from soil borings. These data have demonstrated that in many locations the shallower bay muds contain concentrations of mercury, lead, chromium, petroleum hydrocarbons, PCBs, pesticides and other chemicals which exceed toxic limits: a geological record of human activities of the last century. These data are particularly important to consider when dredging of bay muds is contemplated as part of a development project. Such dredging can have impacts to receiving lands as soil contamination, but also water column impacts from sediment disturbance.

In the case of dredging within the United States, a permit is almost always required from the United States Army Corps of Engineers, after submission of extensive data on the project limits, chemical properties of the bay muds to be disturbed, a dredge disposal plan and often a complete Environmental Impact Statement pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act. Further review by the United States Coast Guard would normally be required. Within individual state jurisdictions, such as California, an Environmental Impact Report must be filed for dredging of any significance; furthermore, agency reviews by the California Coastal Commission and the Regional Water Quality Control Board would normally be mandated. All of these regulatory bodies serve an important role in deciding whether an area may be dredged or not. However, the most important body is the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). This guiding legislation is the reason for Environmental Impact Reports, costly mitigation measures and arduous review processes. One of CEQA's main goals is to promote interagency cooperation in the review process of a project. This is one of the main reasons why it is the overseer of all projects in California.

For buildings proposed over bay mud layers, typically the municipality involved will, in addition to the usual engineering and design review issues common to all building projects (which are more complicated because of the site conditions), require an Environmental Impact Report . This process would include reviews by that city's building department, as well as applicable regional and state agencies such as those cited above for dredging projects, except that Coast Guard agencies would not typically be concerned. In developing in California, proposed development over bay mud layers would also have to go through a planning commission and a city council in order to be allowed. This process would respect the EIR, CEQA, and all the other bodies discussed above. In the case of San Francisco the project would have to get approved by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.

The Millennium Tower, an example of a tall building built on bay mud, was completed in 2008 and subsequently experienced sinking. This has had a negative impact on the residents of this building. In response to this subsidence, San Francisco's city attorney filed a lawsuit against the developer, because the developer failed to inform the residents of the accelerated speed that the building was sinking at.

Sea level rise

Sea level rise will have a huge impact on the ecosystems surrounding and within bays all across the globe. Sea level rise in California will completely engulf bay mud that makes up San Francisco Bay. In order to deal with sea level rise the California Coastal Commission has adopted policy guidelines to help California.

See also

References

- Farzad Naeim, The Seismic Design Handbook, Kluwer Academic Publishers, (2003) ISBN 0-7923-7301-4

- Floyd Fusselman, Environmental Concerns: Learn the Acronyms, Trafford Publishing, Victoria, B.C. (2002) ISBN 1-55369-461-9

- R.B. Halley, E.J. Prager, R.P. Stumpf, K.K. Yates, and C.H. Holmes, sea level rise and the Future of Florida Bay in the Next Century, U.S. Geological Survey, (2001)

- R.Kirby and W.R.Parker, Settled mud deposits in Bridgewater Bay Bristol Channel, Report no. 107, Institute of Oceanographic Sciences, Surrey, UK (1980)

- Judges praise innovative ideas, San Francisco Examiner, Page F-6, January 12, 1992

- C.M.Hogan, Kay Wilson, Ballard George, Marc Papineau et al., Environmental Impact Report for the Crowne Plaza Hotel, prepared by Earth Metrics Inc and. published by the city of Burlingame, California, circulated by the State of California Clearinghouse, (1985)

- Fulton, William (2012). Guide to California Planning 4th edition. Point Arena, California: Solano Press Books. ISBN 978-1-938-166-02-0.

- Wheeler, Stephen (2013). Planning for Sustainability 2nd edition. New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. ISBN 978-0-415-80988-7.

- "About the Board". Board of Supervisors. City and County of San Francisco. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- Fuller, Thomas (3 November 2016). "San Francisco Files Lawsuit Against Sinking Millennium Tower". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- "Sea Level Rise Adopted Policy Guidance". California Coastal Commission. 12 August 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

External links

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service article on bay mud and environmental features for part of the San Francisco Bay perimeter.

- Student project: bay mud food web

| Soil classification | |

|---|---|

| World Reference Base for Soil Resources (1998–) |

|

| USDA soil taxonomy | |

| Other systems |

|

| Non-systematic soil types |

|