| Part of a series of articles about |

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

| Schrödinger equation |

| Background |

| Fundamentals |

| Experiments |

| Formulations |

| Equations |

| Interpretations |

| Advanced topics |

Scientists

|

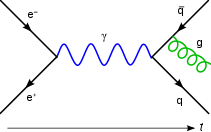

Zero-point energy (ZPE) is the lowest possible energy that a quantum mechanical system may have. Unlike in classical mechanics, quantum systems constantly fluctuate in their lowest energy state as described by the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. Therefore, even at absolute zero, atoms and molecules retain some vibrational motion. Apart from atoms and molecules, the empty space of the vacuum also has these properties. According to quantum field theory, the universe can be thought of not as isolated particles but continuous fluctuating fields: matter fields, whose quanta are fermions (i.e., leptons and quarks), and force fields, whose quanta are bosons (e.g., photons and gluons). All these fields have zero-point energy. These fluctuating zero-point fields lead to a kind of reintroduction of an aether in physics since some systems can detect the existence of this energy. However, this aether cannot be thought of as a physical medium if it is to be Lorentz invariant such that there is no contradiction with Einstein's theory of special relativity.

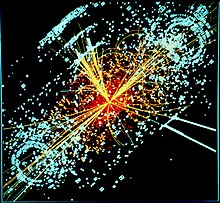

The notion of a zero-point energy is also important for cosmology, and physics currently lacks a full theoretical model for understanding zero-point energy in this context; in particular, the discrepancy between theorized and observed vacuum energy in the universe is a source of major contention. Yet according to Einstein's theory of general relativity, any such energy would gravitate, and the experimental evidence from the expansion of the universe, dark energy and the Casimir effect shows any such energy to be exceptionally weak. One proposal that attempts to address this issue is to say that the fermion field has a negative zero-point energy, while the boson field has positive zero-point energy and thus these energies somehow cancel out each other. This idea would be true if supersymmetry were an exact symmetry of nature; however, the Large Hadron Collider at CERN has so far found no evidence to support it. Moreover, it is known that if supersymmetry is valid at all, it is at most a broken symmetry, only true at very high energies, and no one has been able to show a theory where zero-point cancellations occur in the low-energy universe we observe today. This discrepancy is known as the cosmological constant problem and it is one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in physics. Many physicists believe that "the vacuum holds the key to a full understanding of nature".

Etymology and terminology

The term zero-point energy (ZPE) is a translation from the German Nullpunktsenergie. Sometimes used interchangeably with it are the terms zero-point radiation and ground state energy. The term zero-point field (ZPF) can be used when referring to a specific vacuum field, for instance the QED vacuum which specifically deals with quantum electrodynamics (e.g., electromagnetic interactions between photons, electrons and the vacuum) or the QCD vacuum which deals with quantum chromodynamics (e.g., color charge interactions between quarks, gluons and the vacuum). A vacuum can be viewed not as empty space but as the combination of all zero-point fields. In quantum field theory this combination of fields is called the vacuum state, its associated zero-point energy is called the vacuum energy and the average energy value is called the vacuum expectation value (VEV) also called its condensate.

Overview

In classical mechanics all particles can be thought of as having some energy made up of their potential energy and kinetic energy. Temperature, for example, arises from the intensity of random particle motion caused by kinetic energy (known as Brownian motion). As temperature is reduced to absolute zero, it might be thought that all motion ceases and particles come completely to rest. In fact, however, kinetic energy is retained by particles even at the lowest possible temperature. The random motion corresponding to this zero-point energy never vanishes; it is a consequence of the uncertainty principle of quantum mechanics.

The uncertainty principle states that no object can ever have precise values of position and velocity simultaneously. The total energy of a quantum mechanical object (potential and kinetic) is described by its Hamiltonian which also describes the system as a harmonic oscillator, or wave function, that fluctuates between various energy states (see wave-particle duality). All quantum mechanical systems undergo fluctuations even in their ground state, a consequence of their wave-like nature. The uncertainty principle requires every quantum mechanical system to have a fluctuating zero-point energy greater than the minimum of its classical potential well. This results in motion even at absolute zero. For example, liquid helium does not freeze under atmospheric pressure regardless of temperature due to its zero-point energy.

Given the equivalence of mass and energy expressed by Albert Einstein's E = mc, any point in space that contains energy can be thought of as having mass to create particles. Modern physics has developed quantum field theory (QFT) to understand the fundamental interactions between matter and forces; it treats every single point of space as a quantum harmonic oscillator. According to QFT the universe is made up of matter fields, whose quanta are fermions (i.e. leptons and quarks), and force fields, whose quanta are bosons (e.g. photons and gluons). All these fields have zero-point energy. Recent experiments support the idea that particles themselves can be thought of as excited states of the underlying quantum vacuum, and that all properties of matter are merely vacuum fluctuations arising from interactions of the zero-point field.

The idea that "empty" space can have an intrinsic energy associated with it, and that there is no such thing as a "true vacuum" is seemingly unintuitive. It is often argued that the entire universe is completely bathed in the zero-point radiation, and as such it can add only some constant amount to calculations. Physical measurements will therefore reveal only deviations from this value. For many practical calculations zero-point energy is dismissed by fiat in the mathematical model as a term that has no physical effect. Such treatment causes problems however, as in Einstein's theory of general relativity the absolute energy value of space is not an arbitrary constant and gives rise to the cosmological constant. For decades most physicists assumed that there was some undiscovered fundamental principle that will remove the infinite zero-point energy and make it completely vanish. If the vacuum has no intrinsic, absolute value of energy it will not gravitate. It was believed that as the universe expands from the aftermath of the Big Bang, the energy contained in any unit of empty space will decrease as the total energy spreads out to fill the volume of the universe; galaxies and all matter in the universe should begin to decelerate. This possibility was ruled out in 1998 by the discovery that the expansion of the universe is not slowing down but is in fact accelerating, meaning empty space does indeed have some intrinsic energy. The discovery of dark energy is best explained by zero-point energy, though it still remains a mystery as to why the value appears to be so small compared to the huge value obtained through theory – the cosmological constant problem.

Many physical effects attributed to zero-point energy have been experimentally verified, such as spontaneous emission, Casimir force, Lamb shift, magnetic moment of the electron and Delbrück scattering. These effects are usually called "radiative corrections". In more complex nonlinear theories (e.g. QCD) zero-point energy can give rise to a variety of complex phenomena such as multiple stable states, symmetry breaking, chaos and emergence. Active areas of research include the effects of virtual particles, quantum entanglement, the difference (if any) between inertial and gravitational mass, variation in the speed of light, a reason for the observed value of the cosmological constant and the nature of dark energy.

History

Early aether theories

Zero-point energy evolved from historical ideas about the vacuum. To Aristotle the vacuum was τὸ κενόν, "the empty"; i.e., space independent of body. He believed this concept violated basic physical principles and asserted that the elements of fire, air, earth, and water were not made of atoms, but were continuous. To the atomists the concept of emptiness had absolute character: it was the distinction between existence and nonexistence. Debate about the characteristics of the vacuum were largely confined to the realm of philosophy, it was not until much later on with the beginning of the renaissance, that Otto von Guericke invented the first vacuum pump and the first testable scientific ideas began to emerge. It was thought that a totally empty volume of space could be created by simply removing all gases. This was the first generally accepted concept of the vacuum.

Late in the 19th century, however, it became apparent that the evacuated region still contained thermal radiation. The existence of the aether as a substitute for a true void was the most prevalent theory of the time. According to the successful electromagnetic aether theory based upon Maxwell's electrodynamics, this all-encompassing aether was endowed with energy and hence very different from nothingness. The fact that electromagnetic and gravitational phenomena were transmitted in empty space was considered evidence that their associated aethers were part of the fabric of space itself. However Maxwell noted that for the most part these aethers were ad hoc:

To those who maintained the existence of a plenum as a philosophical principle, nature's abhorrence of a vacuum was a sufficient reason for imagining an all-surrounding aether ... Aethers were invented for the planets to swim in, to constitute electric atmospheres and magnetic effluvia, to convey sensations from one part of our bodies to another, and so on, till a space had been filled three or four times with aethers.

Moreever, the results of the Michelson–Morley experiment in 1887 were the first strong evidence that the then-prevalent aether theories were seriously flawed, and initiated a line of research that eventually led to special relativity, which ruled out the idea of a stationary aether altogether. To scientists of the period, it seemed that a true vacuum in space might be created by cooling and thus eliminating all radiation or energy. From this idea evolved the second concept of achieving a real vacuum: cool a region of space down to absolute zero temperature after evacuation. Absolute zero was technically impossible to achieve in the 19th century, so the debate remained unsolved.

Second quantum theory

In 1900, Max Planck derived the average energy ε of a single energy radiator, e.g., a vibrating atomic unit, as a function of absolute temperature: where h is the Planck constant, ν is the frequency, k is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature. The zero-point energy makes no contribution to Planck's original law, as its existence was unknown to Planck in 1900.

The concept of zero-point energy was developed by Max Planck in Germany in 1911 as a corrective term added to a zero-grounded formula developed in his original quantum theory in 1900.

In 1912, Max Planck published the first journal article to describe the discontinuous emission of radiation, based on the discrete quanta of energy. In Planck's "second quantum theory" resonators absorbed energy continuously, but emitted energy in discrete energy quanta only when they reached the boundaries of finite cells in phase space, where their energies became integer multiples of hν. This theory led Planck to his new radiation law, but in this version energy resonators possessed a zero-point energy, the smallest average energy a resonator could take on. Planck's radiation equation contained a residual energy factor, one hν/2, as an additional term dependent on the frequency ν, which was greater than zero (where h is the Planck constant). It is therefore widely agreed that "Planck's equation marked the birth of the concept of zero-point energy." In a series of papers from 1911 to 1913, Planck found the average energy of an oscillator to be:

Soon, the idea of zero-point energy attracted the attention of Albert Einstein and his assistant Otto Stern. In 1913 they published a paper that attempted to prove the existence of zero-point energy by calculating the specific heat of hydrogen gas and compared it with the experimental data. However, after assuming they had succeeded, they retracted support for the idea shortly after publication because they found Planck's second theory may not apply to their example. In a letter to Paul Ehrenfest of the same year Einstein declared zero-point energy "dead as a doornail". Zero-point energy was also invoked by Peter Debye, who noted that zero-point energy of the atoms of a crystal lattice would cause a reduction in the intensity of the diffracted radiation in X-ray diffraction even as the temperature approached absolute zero. In 1916 Walther Nernst proposed that empty space was filled with zero-point electromagnetic radiation. With the development of general relativity Einstein found the energy density of the vacuum to contribute towards a cosmological constant in order to obtain static solutions to his field equations; the idea that empty space, or the vacuum, could have some intrinsic energy associated with it had returned, with Einstein stating in 1920:

There is a weighty argument to be adduced in favour of the aether hypothesis. To deny the aether is ultimately to assume that empty space has no physical qualities whatever. The fundamental facts of mechanics do not harmonize with this view ... according to the general theory of relativity space is endowed with physical qualities; in this sense, therefore, there exists an aether. According to the general theory of relativity space without aether is unthinkable; for in such space there not only would be no propagation of light, but also no possibility of existence for standards of space and time (measuring-rods and clocks), nor therefore any space-time intervals in the physical sense. But this aether may not be thought of as endowed with the quality characteristic of ponderable media, as consisting of parts which may be tracked through time. The idea of motion may not be applied to it.

Kurt Bennewitz [de] and Francis Simon (1923), who worked at Walther Nernst's laboratory in Berlin, studied the melting process of chemicals at low temperatures. Their calculations of the melting points of hydrogen, argon and mercury led them to conclude that the results provided evidence for a zero-point energy. Moreover, they suggested correctly, as was later verified by Simon (1934), that this quantity was responsible for the difficulty in solidifying helium even at absolute zero. In 1924 Robert Mulliken provided direct evidence for the zero-point energy of molecular vibrations by comparing the band spectrum of BO and BO: the isotopic difference in the transition frequencies between the ground vibrational states of two different electronic levels would vanish if there were no zero-point energy, in contrast to the observed spectra. Then just a year later in 1925, with the development of matrix mechanics in Werner Heisenberg's article "Quantum theoretical re-interpretation of kinematic and mechanical relations" the zero-point energy was derived from quantum mechanics.

In 1913 Niels Bohr had proposed what is now called the Bohr model of the atom, but despite this it remained a mystery as to why electrons do not fall into their nuclei. According to classical ideas, the fact that an accelerating charge loses energy by radiating implied that an electron should spiral into the nucleus and that atoms should not be stable. This problem of classical mechanics was nicely summarized by James Hopwood Jeans in 1915: "There would be a very real difficulty in supposing that the (force) law 1/r held down to the zero values of r. For the forces between two charges at zero distance would be infinite; we should have charges of opposite sign continually rushing together and, when once together, no force would tend to shrink into nothing or to diminish indefinitely in size." The resolution to this puzzle came in 1926 when Erwin Schrödinger introduced the Schrödinger equation. This equation explained the new, non-classical fact that an electron confined to be close to a nucleus would necessarily have a large kinetic energy so that the minimum total energy (kinetic plus potential) actually occurs at some positive separation rather than at zero separation; in other words, zero-point energy is essential for atomic stability.

Quantum field theory and beyond

In 1926, Pascual Jordan published the first attempt to quantize the electromagnetic field. In a joint paper with Max Born and Werner Heisenberg he considered the field inside a cavity as a superposition of quantum harmonic oscillators. In his calculation he found that in addition to the "thermal energy" of the oscillators there also had to exist an infinite zero-point energy term. He was able to obtain the same fluctuation formula that Einstein had obtained in 1909. However, Jordan did not think that his infinite zero-point energy term was "real", writing to Einstein that "it is just a quantity of the calculation having no direct physical meaning". Jordan found a way to get rid of the infinite term, publishing a joint work with Pauli in 1928, performing what has been called "the first infinite subtraction, or renormalisation, in quantum field theory".

Building on the work of Heisenberg and others, Paul Dirac's theory of emission and absorption (1927) was the first application of the quantum theory of radiation. Dirac's work was seen as crucially important to the emerging field of quantum mechanics; it dealt directly with the process in which "particles" are actually created: spontaneous emission. Dirac described the quantization of the electromagnetic field as an ensemble of harmonic oscillators with the introduction of the concept of creation and annihilation operators of particles. The theory showed that spontaneous emission depends upon the zero-point energy fluctuations of the electromagnetic field in order to get started. In a process in which a photon is annihilated (absorbed), the photon can be thought of as making a transition into the vacuum state. Similarly, when a photon is created (emitted), it is occasionally useful to imagine that the photon has made a transition out of the vacuum state. In the words of Dirac:

The light-quantum has the peculiarity that it apparently ceases to exist when it is in one of its stationary states, namely, the zero state, in which its momentum and therefore also its energy, are zero. When a light-quantum is absorbed it can be considered to jump into this zero state, and when one is emitted it can be considered to jump from the zero state to one in which it is physically in evidence, so that it appears to have been created. Since there is no limit to the number of light-quanta that may be created in this way, we must suppose that there are an infinite number of light quanta in the zero state ...

Contemporary physicists, when asked to give a physical explanation for spontaneous emission, generally invoke the zero-point energy of the electromagnetic field. This view was popularized by Victor Weisskopf who in 1935 wrote:

From quantum theory there follows the existence of so called zero-point oscillations; for example each oscillator in its lowest state is not completely at rest but always is moving about its equilibrium position. Therefore electromagnetic oscillations also can never cease completely. Thus the quantum nature of the electromagnetic field has as its consequence zero point oscillations of the field strength in the lowest energy state, in which there are no light quanta in space ... The zero point oscillations act on an electron in the same way as ordinary electrical oscillations do. They can change the eigenstate of the electron, but only in a transition to a state with the lowest energy, since empty space can only take away energy, and not give it up. In this way spontaneous radiation arises as a consequence of the existence of these unique field strengths corresponding to zero point oscillations. Thus spontaneous radiation is induced radiation of light quanta produced by zero point oscillations of empty space

This view was also later supported by Theodore Welton (1948), who argued that spontaneous emission "can be thought of as forced emission taking place under the action of the fluctuating field". This new theory, which Dirac coined quantum electrodynamics (QED), predicted a fluctuating zero-point or "vacuum" field existing even in the absence of sources.

Throughout the 1940s improvements in microwave technology made it possible to take more precise measurements of the shift of the levels of a hydrogen atom, now known as the Lamb shift, and measurement of the magnetic moment of the electron. Discrepancies between these experiments and Dirac's theory led to the idea of incorporating renormalisation into QED to deal with zero-point infinities. Renormalization was originally developed by Hans Kramers and also Victor Weisskopf (1936), and first successfully applied to calculate a finite value for the Lamb shift by Hans Bethe (1947). As per spontaneous emission, these effects can in part be understood with interactions with the zero-point field. But in light of renormalisation being able to remove some zero-point infinities from calculations, not all physicists were comfortable attributing zero-point energy any physical meaning, viewing it instead as a mathematical artifact that might one day be eliminated. In Wolfgang Pauli's 1945 Nobel lecture he made clear his opposition to the idea of zero-point energy stating "It is clear that this zero-point energy has no physical reality".

In 1948 Hendrik Casimir showed that one consequence of the zero-point field is an attractive force between two uncharged, perfectly conducting parallel plates, the so-called Casimir effect. At the time, Casimir was studying the properties of colloidal solutions. These are viscous materials, such as paint and mayonnaise, that contain micron-sized particles in a liquid matrix. The properties of such solutions are determined by Van der Waals forces – short-range, attractive forces that exist between neutral atoms and molecules. One of Casimir's colleagues, Theo Overbeek, realized that the theory that was used at the time to explain Van der Waals forces, which had been developed by Fritz London in 1930, did not properly explain the experimental measurements on colloids. Overbeek therefore asked Casimir to investigate the problem. Working with Dirk Polder, Casimir discovered that the interaction between two neutral molecules could be correctly described only if the fact that light travels at a finite speed was taken into account. Soon afterwards after a conversation with Bohr about zero-point energy, Casimir noticed that this result could be interpreted in terms of vacuum fluctuations. He then asked himself what would happen if there were two mirrors – rather than two molecules – facing each other in a vacuum. It was this work that led to his prediction of an attractive force between reflecting plates. The work by Casimir and Polder opened up the way to a unified theory of van der Waals and Casimir forces and a smooth continuum between the two phenomena. This was done by Lifshitz (1956) in the case of plane parallel dielectric plates. The generic name for both van der Waals and Casimir forces is dispersion forces, because both of them are caused by dispersions of the operator of the dipole moment. The role of relativistic forces becomes dominant at orders of a hundred nanometers.

In 1951 Herbert Callen and Theodore Welton proved the quantum fluctuation-dissipation theorem (FDT) which was originally formulated in classical form by Nyquist (1928) as an explanation for observed Johnson noise in electric circuits. The fluctuation-dissipation theorem showed that when something dissipates energy, in an effectively irreversible way, a connected heat bath must also fluctuate. The fluctuations and the dissipation go hand in hand; it is impossible to have one without the other. The implication of FDT being that the vacuum could be treated as a heat bath coupled to a dissipative force and as such energy could, in part, be extracted from the vacuum for potentially useful work. FDT has been shown to be true experimentally under certain quantum, non-classical, conditions.

In 1963 the Jaynes–Cummings model was developed describing the system of a two-level atom interacting with a quantized field mode (i.e. the vacuum) within an optical cavity. It gave nonintuitive predictions such as that an atom's spontaneous emission could be driven by field of effectively constant frequency (Rabi frequency). In the 1970s experiments were being performed to test aspects of quantum optics and showed that the rate of spontaneous emission of an atom could be controlled using reflecting surfaces. These results were at first regarded with suspicion in some quarters: it was argued that no modification of a spontaneous emission rate would be possible, after all, how can the emission of a photon be affected by an atom's environment when the atom can only "see" its environment by emitting a photon in the first place? These experiments gave rise to cavity quantum electrodynamics (CQED), the study of effects of mirrors and cavities on radiative corrections. Spontaneous emission can be suppressed (or "inhibited") or amplified. Amplification was first predicted by Purcell in 1946 (the Purcell effect) and has been experimentally verified. This phenomenon can be understood, partly, in terms of the action of the vacuum field on the atom.

Uncertainty principle

Main article: Uncertainty principleZero-point energy is fundamentally related to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. Roughly speaking, the uncertainty principle states that complementary variables (such as a particle's position and momentum, or a field's value and derivative at a point in space) cannot simultaneously be specified precisely by any given quantum state. In particular, there cannot exist a state in which the system simply sits motionless at the bottom of its potential well, for then its position and momentum would both be completely determined to arbitrarily great precision. Therefore, the lowest-energy state (the ground state) of the system must have a distribution in position and momentum that satisfies the uncertainty principle, which implies its energy must be greater than the minimum of the potential well.

Near the bottom of a potential well, the Hamiltonian of a general system (the quantum-mechanical operator giving its energy) can be approximated as a quantum harmonic oscillator, where V0 is the minimum of the classical potential well.

The uncertainty principle tells us that making the expectation values of the kinetic and potential terms above satisfy

The expectation value of the energy must therefore be at least

where ω = √k/m is the angular frequency at which the system oscillates.

A more thorough treatment, showing that the energy of the ground state actually saturates this bound and is exactly E0 = V0 + ħω/2, requires solving for the ground state of the system.

Atomic physics

Main article: Ground state

The idea of a quantum harmonic oscillator and its associated energy can apply to either an atom or a subatomic particle. In ordinary atomic physics, the zero-point energy is the energy associated with the ground state of the system. The professional physics literature tends to measure frequency, as denoted by ν above, using angular frequency, denoted with ω and defined by ω = 2πν. This leads to a convention of writing the Planck constant h with a bar through its top (ħ) to denote the quantity h/2π. In these terms, an example of zero-point energy is the above E = ħω/2 associated with the ground state of the quantum harmonic oscillator. In quantum mechanical terms, the zero-point energy is the expectation value of the Hamiltonian of the system in the ground state.

If more than one ground state exists, they are said to be degenerate. Many systems have degenerate ground states. Degeneracy occurs whenever there exists a unitary operator which acts non-trivially on a ground state and commutes with the Hamiltonian of the system.

According to the third law of thermodynamics, a system at absolute zero temperature exists in its ground state; thus, its entropy is determined by the degeneracy of the ground state. Many systems, such as a perfect crystal lattice, have a unique ground state and therefore have zero entropy at absolute zero. It is also possible for the highest excited state to have absolute zero temperature for systems that exhibit negative temperature.

The wave function of the ground state of a particle in a one-dimensional well is a half-period sine wave which goes to zero at the two edges of the well. The energy of the particle is given by: where h is the Planck constant, m is the mass of the particle, n is the energy state (n = 1 corresponds to the ground-state energy), and L is the width of the well.

Quantum field theory

Vacuum expectation value, Vacuum energy, and Vacuum stateIn quantum field theory (QFT), the fabric of "empty" space is visualized as consisting of fields, with the field at every point in space and time being a quantum harmonic oscillator, with neighboring oscillators interacting with each other. According to QFT the universe is made up of matter fields whose quanta are fermions (e.g. electrons and quarks), force fields whose quanta are bosons (i.e. photons and gluons) and a Higgs field whose quantum is the Higgs boson. The matter and force fields have zero-point energy. A related term is zero-point field (ZPF), which is the lowest energy state of a particular field. The vacuum can be viewed not as empty space, but as the combination of all zero-point fields.

In QFT the zero-point energy of the vacuum state is called the vacuum energy and the average expectation value of the Hamiltonian is called the vacuum expectation value (also called condensate or simply VEV). The QED vacuum is a part of the vacuum state which specifically deals with quantum electrodynamics (e.g. electromagnetic interactions between photons, electrons and the vacuum) and the QCD vacuum deals with quantum chromodynamics (e.g. color charge interactions between quarks, gluons and the vacuum). Recent experiments advocate the idea that particles themselves can be thought of as excited states of the underlying quantum vacuum, and that all properties of matter are merely vacuum fluctuations arising from interactions with the zero-point field.

Each point in space makes a contribution of E = ħω/2, resulting in a calculation of infinite zero-point energy in any finite volume; this is one reason renormalization is needed to make sense of quantum field theories. In cosmology, the vacuum energy is one possible explanation for the cosmological constant and the source of dark energy.

Scientists are not in agreement about how much energy is contained in the vacuum. Quantum mechanics requires the energy to be large as Paul Dirac claimed it is, like a sea of energy. Other scientists specializing in General Relativity require the energy to be small enough for curvature of space to agree with observed astronomy. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle allows the energy to be as large as needed to promote quantum actions for a brief moment of time, even if the average energy is small enough to satisfy relativity and flat space. To cope with disagreements, the vacuum energy is described as a virtual energy potential of positive and negative energy.

In quantum perturbation theory, it is sometimes said that the contribution of one-loop and multi-loop Feynman diagrams to elementary particle propagators are the contribution of vacuum fluctuations, or the zero-point energy to the particle masses.

Quantum electrodynamic vacuum

Main article: QED vacuumThe oldest and best known quantized force field is the electromagnetic field. Maxwell's equations have been superseded by quantum electrodynamics (QED). By considering the zero-point energy that arises from QED it is possible to gain a characteristic understanding of zero-point energy that arises not just through electromagnetic interactions but in all quantum field theories.

Redefining the zero of energy

In the quantum theory of the electromagnetic field, classical wave amplitudes α and α* are replaced by operators a and a that satisfy:

The classical quantity |α| appearing in the classical expression for the energy of a field mode is replaced in quantum theory by the photon number operator aa. The fact that: implies that quantum theory does not allow states of the radiation field for which the photon number and a field amplitude can be precisely defined, i.e., we cannot have simultaneous eigenstates for aa and a. The reconciliation of wave and particle attributes of the field is accomplished via the association of a probability amplitude with a classical mode pattern. The calculation of field modes is entirely classical problem, while the quantum properties of the field are carried by the mode "amplitudes" a and a associated with these classical modes.

The zero-point energy of the field arises formally from the non-commutativity of a and a. This is true for any harmonic oscillator: the zero-point energy ħω/2 appears when we write the Hamiltonian:

It is often argued that the entire universe is completely bathed in the zero-point electromagnetic field, and as such it can add only some constant amount to expectation values. Physical measurements will therefore reveal only deviations from the vacuum state. Thus the zero-point energy can be dropped from the Hamiltonian by redefining the zero of energy, or by arguing that it is a constant and therefore has no effect on Heisenberg equations of motion. Thus we can choose to declare by fiat that the ground state has zero energy and a field Hamiltonian, for example, can be replaced by: without affecting any physical predictions of the theory. The new Hamiltonian is said to be normally ordered (or Wick ordered) and is denoted by a double-dot symbol. The normally ordered Hamiltonian is denoted :HF, i.e.:

In other words, within the normal ordering symbol we can commute a and a. Since zero-point energy is intimately connected to the non-commutativity of a and a, the normal ordering procedure eliminates any contribution from the zero-point field. This is especially reasonable in the case of the field Hamiltonian, since the zero-point term merely adds a constant energy which can be eliminated by a simple redefinition for the zero of energy. Moreover, this constant energy in the Hamiltonian obviously commutes with a and a and so cannot have any effect on the quantum dynamics described by the Heisenberg equations of motion.

However, things are not quite that simple. The zero-point energy cannot be eliminated by dropping its energy from the Hamiltonian: When we do this and solve the Heisenberg equation for a field operator, we must include the vacuum field, which is the homogeneous part of the solution for the field operator. In fact we can show that the vacuum field is essential for the preservation of the commutators and the formal consistency of QED. When we calculate the field energy we obtain not only a contribution from particles and forces that may be present but also a contribution from the vacuum field itself i.e. the zero-point field energy. In other words, the zero-point energy reappears even though we may have deleted it from the Hamiltonian.

Electromagnetic field in free space

From Maxwell's equations, the electromagnetic energy of a "free" field i.e. one with no sources, is described by:

We introduce the "mode function" A0(r) that satisfies the Helmholtz equation: where k = ω/c and assume it is normalized such that:

We wish to "quantize" the electromagnetic energy of free space for a multimode field. The field intensity of free space should be independent of position such that |A0(r)| should be independent of r for each mode of the field. The mode function satisfying these conditions is: where k · ek = 0 in order to have the transversality condition ∇ · A(r,t) satisfied for the Coulomb gauge in which we are working.

To achieve the desired normalization we pretend space is divided into cubes of volume V = L and impose on the field the periodic boundary condition:

or equivalently

where n can assume any integer value. This allows us to consider the field in any one of the imaginary cubes and to define the mode function:

which satisfies the Helmholtz equation, transversality, and the "box normalization":

where ek is chosen to be a unit vector which specifies the polarization of the field mode. The condition k · ek = 0 means that there are two independent choices of ek, which we call ek1 and ek2 where ek1 · ek2 = 0 and e

k1 = e

k2 = 1. Thus we define the mode functions:

in terms of which the vector potential becomes:

or:

where ωk = kc and akλ, a

kλ are photon annihilation and creation operators for the mode with wave vector k and polarization λ. This gives the vector potential for a plane wave mode of the field. The condition for (kx, ky, kz) shows that there are infinitely many such modes. The linearity of Maxwell's equations allows us to write:

for the total vector potential in free space. Using the fact that:

we find the field Hamiltonian is:

This is the Hamiltonian for an infinite number of uncoupled harmonic oscillators. Thus different modes of the field are independent and satisfy the commutation relations:

Clearly the least eigenvalue for HF is:

This state describes the zero-point energy of the vacuum. It appears that this sum is divergent – in fact highly divergent, as putting in the density factor shows. The summation becomes approximately the integral: for high values of v. It diverges proportional to v for large v.

There are two separate questions to consider. First, is the divergence a real one such that the zero-point energy really is infinite? If we consider the volume V is contained by perfectly conducting walls, very high frequencies can only be contained by taking more and more perfect conduction. No actual method of containing the high frequencies is possible. Such modes will not be stationary in our box and thus not countable in the stationary energy content. So from this physical point of view the above sum should only extend to those frequencies which are countable; a cut-off energy is thus eminently reasonable. However, on the scale of a "universe" questions of general relativity must be included. Suppose even the boxes could be reproduced, fit together and closed nicely by curving spacetime. Then exact conditions for running waves may be possible. However the very high frequency quanta will still not be contained. As per John Wheeler's "geons" these will leak out of the system. So again a cut-off is permissible, almost necessary. The question here becomes one of consistency since the very high energy quanta will act as a mass source and start curving the geometry.

This leads to the second question. Divergent or not, finite or infinite, is the zero-point energy of any physical significance? The ignoring of the whole zero-point energy is often encouraged for all practical calculations. The reason for this is that energies are not typically defined by an arbitrary data point, but rather changes in data points, so adding or subtracting a constant (even if infinite) should be allowed. However this is not the whole story, in reality energy is not so arbitrarily defined: in general relativity the seat of the curvature of spacetime is the energy content and there the absolute amount of energy has real physical meaning. There is no such thing as an arbitrary additive constant with density of field energy. Energy density curves space, and an increase in energy density produces an increase of curvature. Furthermore, the zero-point energy density has other physical consequences e.g. the Casimir effect, contribution to the Lamb shift, or anomalous magnetic moment of the electron, it is clear it is not just a mathematical constant or artifact that can be cancelled out.

Necessity of the vacuum field in QED

The vacuum state of the "free" electromagnetic field (that with no sources) is defined as the ground state in which nkλ = 0 for all modes (k, λ). The vacuum state, like all stationary states of the field, is an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian but not the electric and magnetic field operators. In the vacuum state, therefore, the electric and magnetic fields do not have definite values. We can imagine them to be fluctuating about their mean value of zero.

In a process in which a photon is annihilated (absorbed), we can think of the photon as making a transition into the vacuum state. Similarly, when a photon is created (emitted), it is occasionally useful to imagine that the photon has made a transition out of the vacuum state. An atom, for instance, can be considered to be "dressed" by emission and reabsorption of "virtual photons" from the vacuum. The vacuum state energy described by Σkλ ħωk/2 is infinite. We can make the replacement: the zero-point energy density is: or in other words the spectral energy density of the vacuum field:

The zero-point energy density in the frequency range from ω1 to ω2 is therefore:

This can be large even in relatively narrow "low frequency" regions of the spectrum. In the optical region from 400 to 700 nm, for instance, the above equation yields around 220 erg/cm.

We showed in the above section that the zero-point energy can be eliminated from the Hamiltonian by the normal ordering prescription. However, this elimination does not mean that the vacuum field has been rendered unimportant or without physical consequences. To illustrate this point we consider a linear dipole oscillator in the vacuum. The Hamiltonian for the oscillator plus the field with which it interacts is:

This has the same form as the corresponding classical Hamiltonian and the Heisenberg equations of motion for the oscillator and the field are formally the same as their classical counterparts. For instance the Heisenberg equations for the coordinate x and the canonical momentum p = mẋ +eA/c of the oscillator are: or: since the rate of change of the vector potential in the frame of the moving charge is given by the convective derivative

For nonrelativistic motion we may neglect the magnetic force and replace the expression for mẍ by:

Above we have made the electric dipole approximation in which the spatial dependence of the field is neglected. The Heisenberg equation for akλ is found similarly from the Hamiltonian to be: in the electric dipole approximation.

In deriving these equations for x, p, and akλ we have used the fact that equal-time particle and field operators commute. This follows from the assumption that particle and field operators commute at some time (say, t = 0) when the matter-field interpretation is presumed to begin, together with the fact that a Heisenberg-picture operator A(t) evolves in time as A(t) = U(t)A(0)U(t), where U(t) is the time evolution operator satisfying

Alternatively, we can argue that these operators must commute if we are to obtain the correct equations of motion from the Hamiltonian, just as the corresponding Poisson brackets in classical theory must vanish in order to generate the correct Hamilton equations. The formal solution of the field equation is: and therefore the equation for ȧkλ may be written: where and

It can be shown that in the radiation reaction field, if the mass m is regarded as the "observed" mass then we can take

The total field acting on the dipole has two parts, E0(t) and ERR(t). E0(t) is the free or zero-point field acting on the dipole. It is the homogeneous solution of the Maxwell equation for the field acting on the dipole, i.e., the solution, at the position of the dipole, of the wave equation satisfied by the field in the (source free) vacuum. For this reason E0(t) is often referred to as the "vacuum field", although it is of course a Heisenberg-picture operator acting on whatever state of the field happens to be appropriate at t = 0. ERR(t) is the source field, the field generated by the dipole and acting on the dipole.

Using the above equation for ERR(t) we obtain an equation for the Heisenberg-picture operator that is formally the same as the classical equation for a linear dipole oscillator: where τ = 2e/3mc. in this instance we have considered a dipole in the vacuum, without any "external" field acting on it. the role of the external field in the above equation is played by the vacuum electric field acting on the dipole.

Classically, a dipole in the vacuum is not acted upon by any "external" field: if there are no sources other than the dipole itself, then the only field acting on the dipole is its own radiation reaction field. In quantum theory however there is always an "external" field, namely the source-free or vacuum field E0(t).

According to our earlier equation for akλ(t) the free field is the only field in existence at t = 0 as the time at which the interaction between the dipole and the field is "switched on". The state vector of the dipole-field system at t = 0 is therefore of the form where |vac⟩ is the vacuum state of the field and |ψD⟩ is the initial state of the dipole oscillator. The expectation value of the free field is therefore at all times equal to zero: since akλ(0)|vac⟩ = 0. however, the energy density associated with the free field is infinite:

The important point of this is that the zero-point field energy HF does not affect the Heisenberg equation for akλ since it is a c-number or constant (i.e. an ordinary number rather than an operator) and commutes with akλ. We can therefore drop the zero-point field energy from the Hamiltonian, as is usually done. But the zero-point field re-emerges as the homogeneous solution for the field equation. A charged particle in the vacuum will therefore always see a zero-point field of infinite density. This is the origin of one of the infinities of quantum electrodynamics, and it cannot be eliminated by the trivial expedient dropping of the term Σkλ ħωk/2 in the field Hamiltonian.

The free field is in fact necessary for the formal consistency of the theory. In particular, it is necessary for the preservation of the commutation relations, which is required by the unitary of time evolution in quantum theory:

We can calculate from the formal solution of the operator equation of motion

Using the fact that and that equal-time particle and field operators commute, we obtain:

For the dipole oscillator under consideration it can be assumed that the radiative damping rate is small compared with the natural oscillation frequency, i.e., τω0 ≪ 1. Then the integrand above is sharply peaked at ω = ω0 and: the necessity of the vacuum field can also be appreciated by making the small damping approximation in and

Without the free field E0(t) in this equation the operator x(t) would be exponentially dampened, and commutators like would approach zero for t ≫ 1/τω

0. With the vacuum field included, however, the commutator is iħ at all times, as required by unitarity, and as we have just shown. A similar result is easily worked out for the case of a free particle instead of a dipole oscillator.

What we have here is an example of a "fluctuation-dissipation elation". Generally speaking if a system is coupled to a bath that can take energy from the system in an effectively irreversible way, then the bath must also cause fluctuations. The fluctuations and the dissipation go hand in hand we cannot have one without the other. In the current example the coupling of a dipole oscillator to the electromagnetic field has a dissipative component, in the form of the zero-point (vacuum) field; given the existence of radiation reaction, the vacuum field must also exist in order to preserve the canonical commutation rule and all it entails.

The spectral density of the vacuum field is fixed by the form of the radiation reaction field, or vice versa: because the radiation reaction field varies with the third derivative of x, the spectral energy density of the vacuum field must be proportional to the third power of ω in order for to hold. In the case of a dissipative force proportional to ẋ, by contrast, the fluctuation force must be proportional to in order to maintain the canonical commutation relation. This relation between the form of the dissipation and the spectral density of the fluctuation is the essence of the fluctuation-dissipation theorem.

The fact that the canonical commutation relation for a harmonic oscillator coupled to the vacuum field is preserved implies that the zero-point energy of the oscillator is preserved. it is easy to show that after a few damping times the zero-point motion of the oscillator is in fact sustained by the driving zero-point field.

Quantum chromodynamic vacuum

Main article: QCD vacuumThe QCD vacuum is the vacuum state of quantum chromodynamics (QCD). It is an example of a non-perturbative vacuum state, characterized by a non-vanishing condensates such as the gluon condensate and the quark condensate in the complete theory which includes quarks. The presence of these condensates characterizes the confined phase of quark matter. In technical terms, gluons are vector gauge bosons that mediate strong interactions of quarks in quantum chromodynamics (QCD). Gluons themselves carry the color charge of the strong interaction. This is unlike the photon, which mediates the electromagnetic interaction but lacks an electric charge. Gluons therefore participate in the strong interaction in addition to mediating it, making QCD significantly harder to analyze than QED (quantum electrodynamics) as it deals with nonlinear equations to characterize such interactions.

Higgs field

Main article: Higgs mechanism

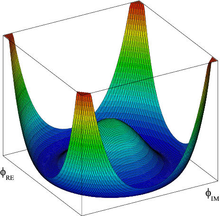

The Standard Model hypothesises a field called the Higgs field (symbol: ϕ), which has the unusual property of a non-zero amplitude in its ground state (zero-point) energy after renormalization; i.e., a non-zero vacuum expectation value. It can have this effect because of its unusual "Mexican hat" shaped potential whose lowest "point" is not at its "centre". Below a certain extremely high energy level the existence of this non-zero vacuum expectation spontaneously breaks electroweak gauge symmetry which in turn gives rise to the Higgs mechanism and triggers the acquisition of mass by those particles interacting with the field. The Higgs mechanism occurs whenever a charged field has a vacuum expectation value. This effect occurs because scalar field components of the Higgs field are "absorbed" by the massive bosons as degrees of freedom, and couple to the fermions via Yukawa coupling, thereby producing the expected mass terms. The expectation value of ϕ in the ground state (the vacuum expectation value or VEV) is then ⟨ϕ⟩ = v/√2, where v = |μ|/√λ. The measured value of this parameter is approximately 246 GeV/c. It has units of mass, and is the only free parameter of the Standard Model that is not a dimensionless number.

The Higgs mechanism is a type of superconductivity which occurs in the vacuum. It occurs when all of space is filled with a sea of particles which are charged and thus the field has a nonzero vacuum expectation value. Interaction with the vacuum energy filling the space prevents certain forces from propagating over long distances (as it does in a superconducting medium; e.g., in the Ginzburg–Landau theory).

Experimental observations

Zero-point energy has many observed physical consequences. It is important to note that zero-point energy is not merely an artifact of mathematical formalism that can, for instance, be dropped from a Hamiltonian by redefining the zero of energy, or by arguing that it is a constant and therefore has no effect on Heisenberg equations of motion without latter consequence. Indeed, such treatment could create a problem at a deeper, as of yet undiscovered, theory. For instance, in general relativity the zero of energy (i.e. the energy density of the vacuum) contributes to a cosmological constant of the type introduced by Einstein in order to obtain static solutions to his field equations. The zero-point energy density of the vacuum, due to all quantum fields, is extremely large, even when we cut off the largest allowable frequencies based on plausible physical arguments. It implies a cosmological constant larger than the limits imposed by observation by about 120 orders of magnitude. This "cosmological constant problem" remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of physics.

Casimir effect

Main article: Casimir effect

A phenomenon that is commonly presented as evidence for the existence of zero-point energy in vacuum is the Casimir effect, proposed in 1948 by Dutch physicist Hendrik Casimir, who considered the quantized electromagnetic field between a pair of grounded, neutral metal plates. The vacuum energy contains contributions from all wavelengths, except those excluded by the spacing between plates. As the plates draw together, more wavelengths are excluded and the vacuum energy decreases. The decrease in energy means there must be a force doing work on the plates as they move.

Early experimental tests from the 1950s onwards gave positive results showing the force was real, but other external factors could not be ruled out as the primary cause, with the range of experimental error sometimes being nearly 100%. That changed in 1997 with Lamoreaux conclusively showing that the Casimir force was real. Results have been repeatedly replicated since then.

In 2009, Munday et al. published experimental proof that (as predicted in 1961) the Casimir force could also be repulsive as well as being attractive. Repulsive Casimir forces could allow quantum levitation of objects in a fluid and lead to a new class of switchable nanoscale devices with ultra-low static friction.

An interesting hypothetical side effect of the Casimir effect is the Scharnhorst effect, a hypothetical phenomenon in which light signals travel slightly faster than c between two closely spaced conducting plates.

Lamb shift

Main article: Lamb shift

The quantum fluctuations of the electromagnetic field have important physical consequences. In addition to the Casimir effect, they also lead to a splitting between the two energy levels S1/2 and P1/2 (in term symbol notation) of the hydrogen atom which was not predicted by the Dirac equation, according to which these states should have the same energy. Charged particles can interact with the fluctuations of the quantized vacuum field, leading to slight shifts in energy; this effect is called the Lamb shift. The shift of about 4.38×10 eV is roughly 10 of the difference between the energies of the 1s and 2s levels, and amounts to 1,058 MHz in frequency units. A small part of this shift (27 MHz ≈ 3%) arises not from fluctuations of the electromagnetic field, but from fluctuations of the electron–positron field. The creation of (virtual) electron–positron pairs has the effect of screening the Coulomb field and acts as a vacuum dielectric constant. This effect is much more important in muonic atoms.

Fine-structure constant

Main article: Fine-structure constantTaking ħ (the Planck constant divided by 2π), c (the speed of light), and e = q

e/4πε0 (the electromagnetic coupling constant i.e. a measure of the strength of the electromagnetic force (where qe is the absolute value of the electronic charge and is the vacuum permittivity)) we can form a dimensionless quantity called the fine-structure constant:

The fine-structure constant is the coupling constant of quantum electrodynamics (QED) determining the strength of the interaction between electrons and photons. It turns out that the fine-structure constant is not really a constant at all owing to the zero-point energy fluctuations of the electron-positron field. The quantum fluctuations caused by zero-point energy have the effect of screening electric charges: owing to (virtual) electron-positron pair production, the charge of the particle measured far from the particle is far smaller than the charge measured when close to it.

The Heisenberg inequality where ħ = h/2π, and Δx, Δp are the standard deviations of position and momentum states that:

It means that a short distance implies large momentum and therefore high energy i.e. particles of high energy must be used to explore short distances. QED concludes that the fine-structure constant is an increasing function of energy. It has been shown that at energies of the order of the Z boson rest energy, mzc ≈ 90 GeV, that: rather than the low-energy α ≈ 1/137. The renormalization procedure of eliminating zero-point energy infinities allows the choice of an arbitrary energy (or distance) scale for defining α. All in all, α depends on the energy scale characteristic of the process under study, and also on details of the renormalization procedure. The energy dependence of α has been observed for several years now in precision experiment in high-energy physics.

Vacuum birefringence

Main articles: Lorentz-violating electrodynamics and Euler–Heisenberg LagrangianIn the presence of strong electrostatic fields it is predicted that virtual particles become separated from the vacuum state and form real matter. The fact that electromagnetic radiation can be transformed into matter and vice versa leads to fundamentally new features in quantum electrodynamics. One of the most important consequences is that, even in the vacuum, the Maxwell equations have to be exchanged by more complicated formulas. In general, it will be not possible to separate processes in the vacuum from the processes involving matter since electromagnetic fields can create matter if the field fluctuations are strong enough. This leads to highly complex nonlinear interaction – gravity will have an effect on the light at the same time the light has an effect on gravity. These effects were first predicted by Werner Heisenberg and Hans Heinrich Euler in 1936 and independently the same year by Victor Weisskopf who stated: "The physical properties of the vacuum originate in the "zero-point energy" of matter, which also depends on absent particles through the external field strengths and therefore contributes an additional term to the purely Maxwellian field energy". Thus strong magnetic fields vary the energy contained in the vacuum. The scale above which the electromagnetic field is expected to become nonlinear is known as the Schwinger limit. At this point the vacuum has all the properties of a birefringent medium, thus in principle a rotation of the polarization frame (the Faraday effect) can be observed in empty space.

Both Einstein's theory of special and general relativity state that light should pass freely through a vacuum without being altered, a principle known as Lorentz invariance. Yet, in theory, large nonlinear self-interaction of light due to quantum fluctuations should lead to this principle being measurably violated if the interactions are strong enough. Nearly all theories of quantum gravity predict that Lorentz invariance is not an exact symmetry of nature. It is predicted the speed at which light travels through the vacuum depends on its direction, polarization and the local strength of the magnetic field. There have been a number of inconclusive results which claim to show evidence of a Lorentz violation by finding a rotation of the polarization plane of light coming from distant galaxies. The first concrete evidence for vacuum birefringence was published in 2017 when a team of astronomers looked at the light coming from the star RX J1856.5-3754, the closest discovered neutron star to Earth.

Roberto Mignani at the National Institute for Astrophysics in Milan who led the team of astronomers has commented that "When Einstein came up with the theory of general relativity 100 years ago, he had no idea that it would be used for navigational systems. The consequences of this discovery probably will also have to be realised on a longer timescale." The team found that visible light from the star had undergone linear polarisation of around 16%. If the birefringence had been caused by light passing through interstellar gas or plasma, the effect should have been no more than 1%. Definitive proof would require repeating the observation at other wavelengths and on other neutron stars. At X-ray wavelengths the polarization from the quantum fluctuations should be near 100%. Although no telescope currently exists that can make such measurements, there are several proposed X-ray telescopes that may soon be able to verify the result conclusively such as China's Hard X-ray Modulation Telescope (HXMT) and NASA's Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE).

Speculated involvement in other phenomena

Dark energy

Main article: Dark energy Unsolved problem in physics: Why does the large zero-point energy of the vacuum not cause a large cosmological constant? What cancels it out? (more unsolved problems in physics)In the late 1990s it was discovered that very distant supernovae were dimmer than expected suggesting that the universe's expansion was accelerating rather than slowing down. This revived discussion that Einstein's cosmological constant, long disregarded by physicists as being equal to zero, was in fact some small positive value. This would indicate empty space exerted some form of negative pressure or energy.

There is no natural candidate for what might cause what has been called dark energy but the current best guess is that it is the zero-point energy of the vacuum, but this guess is known to be off by 120 orders of magnitude.

The European Space Agency's Euclid telescope, launched on 1 July 2023, will map galaxies up to 10 billion light years away. By seeing how dark energy influences their arrangement and shape, the mission will allow scientists to see if the strength of dark energy has changed. If dark energy is found to vary throughout time it would indicate it is due to quintessence, where observed acceleration is due to the energy of a scalar field, rather than the cosmological constant. No evidence of quintessence is yet available, but it has not been ruled out either. It generally predicts a slightly slower acceleration of the expansion of the universe than the cosmological constant. Some scientists think that the best evidence for quintessence would come from violations of Einstein's equivalence principle and variation of the fundamental constants in space or time. Scalar fields are predicted by the Standard Model of particle physics and string theory, but an analogous problem to the cosmological constant problem (or the problem of constructing models of cosmological inflation) occurs: renormalization theory predicts that scalar fields should acquire large masses again due to zero-point energy.

Cosmic inflation

Main article: Inflation (cosmology) Unsolved problem in physics: Why does the observable universe have more matter than antimatter? (more unsolved problems in physics)Cosmic inflation is phase of accelerated cosmic expansion just after the Big Bang. It explains the origin of the large-scale structure of the cosmos. It is believed quantum vacuum fluctuations caused by zero-point energy arising in the microscopic inflationary period, later became magnified to a cosmic size, becoming the gravitational seeds for galaxies and structure in the Universe (see galaxy formation and evolution and structure formation). Many physicists also believe that inflation explains why the Universe appears to be the same in all directions (isotropic), why the cosmic microwave background radiation is distributed evenly, why the Universe is flat, and why no magnetic monopoles have been observed.

The mechanism for inflation is unclear, it is similar in effect to dark energy but is a far more energetic and short lived process. As with dark energy the best explanation is some form of vacuum energy arising from quantum fluctuations. It may be that inflation caused baryogenesis, the hypothetical physical processes that produced an asymmetry (imbalance) between baryons and antibaryons produced in the very early universe, but this is far from certain.

Cosmology

Paul S. Wesson examined the cosmological implications of assuming that zero-point energy is real. Among numerous difficulties, general relativity requires that such energy not gravitate, so it cannot be similar to electromagnetic radiation.

Alternative theories

There has been a long debate over the question of whether zero-point fluctuations of quantized vacuum fields are "real" i.e. do they have physical effects that cannot be interpreted by an equally valid alternative theory? Schwinger, in particular, attempted to formulate QED without reference to zero-point fluctuations via his "source theory". From such an approach it is possible to derive the Casimir Effect without reference to a fluctuating field. Such a derivation was first given by Schwinger (1975) for a scalar field, and then generalized to the electromagnetic case by Schwinger, DeRaad, and Milton (1978). in which they state "the vacuum is regarded as truly a state with all physical properties equal to zero". Jaffe (2005) has highlighted a similar approach in deriving the Casimir effect stating "the concept of zero-point fluctuations is a heuristic and calculational aid in the description of the Casimir effect, but not a necessity in QED."

Milonni has shown the necessity of the vacuum field for the formal consistency of QED. Modern physics does not know any better way to construct gauge-invariant, renormalizable theories than with zero-point energy and they would seem to be a necessity for any attempt at a unified theory. Nevertheless, as pointed out by Jaffe, "no known phenomenon, including the Casimir effect, demonstrates that zero point energies are “real”"

Chaotic and emergent phenomena

Chaos theory, Emergence, and Self-organizationThe mathematical models used in classical electromagnetism, quantum electrodynamics (QED) and the Standard Model all view the electromagnetic vacuum as a linear system with no overall observable consequence. For example, in the case of the Casimir effect, Lamb shift, and so on these phenomena can be explained by alternative mechanisms other than action of the vacuum by arbitrary changes to the normal ordering of field operators. See the alternative theories section. This is a consequence of viewing electromagnetism as a U(1) gauge theory, which topologically does not allow the complex interaction of a field with and on itself. In higher symmetry groups and in reality, the vacuum is not a calm, randomly fluctuating, largely immaterial and passive substance, but at times can be viewed as a turbulent virtual plasma that can have complex vortices (i.e. solitons vis-à-vis particles), entangled states and a rich nonlinear structure. There are many observed nonlinear physical electromagnetic phenomena such as Aharonov–Bohm (AB) and Altshuler–Aronov–Spivak (AAS) effects, Berry, Aharonov–Anandan, Pancharatnam and Chiao–Wu phase rotation effects, Josephson effect, Quantum Hall effect, the De Haas–Van Alphen effect, the Sagnac effect and many other physically observable phenomena which would indicate that the electromagnetic potential field has real physical meaning rather than being a mathematical artifact and therefore an all encompassing theory would not confine electromagnetism as a local force as is currently done, but as a SU(2) gauge theory or higher geometry. Higher symmetries allow for nonlinear, aperiodic behaviour which manifest as a variety of complex non-equilibrium phenomena that do not arise in the linearised U(1) theory, such as multiple stable states, symmetry breaking, chaos and emergence.

What are called Maxwell's equations today, are in fact a simplified version of the original equations reformulated by Heaviside, FitzGerald, Lodge and Hertz. The original equations used Hamilton's more expressive quaternion notation, a kind of Clifford algebra, which fully subsumes the standard Maxwell vectorial equations largely used today. In the late 1880s there was a debate over the relative merits of vector analysis and quaternions. According to Heaviside the electromagnetic potential field was purely metaphysical, an arbitrary mathematical fiction, that needed to be "murdered". It was concluded that there was no need for the greater physical insights provided by the quaternions if the theory was purely local in nature. Local vector analysis has become the dominant way of using Maxwell's equations ever since. However, this strictly vectorial approach has led to a restrictive topological understanding in some areas of electromagnetism, for example, a full understanding of the energy transfer dynamics in Tesla's oscillator-shuttle-circuit can only be achieved in quaternionic algebra or higher SU(2) symmetries. It has often been argued that quaternions are not compatible with special relativity, but multiple papers have shown ways of incorporating relativity.

A good example of nonlinear electromagnetics is in high energy dense plasmas, where vortical phenomena occur which seemingly violate the second law of thermodynamics by increasing the energy gradient within the electromagnetic field and violate Maxwell's laws by creating ion currents which capture and concentrate their own and surrounding magnetic fields. In particular Lorentz force law, which elaborates Maxwell's equations is violated by these force free vortices. These apparent violations are due to the fact that the traditional conservation laws in classical and quantum electrodynamics (QED) only display linear U(1) symmetry (in particular, by the extended Noether theorem, conservation laws such as the laws of thermodynamics need not always apply to dissipative systems, which are expressed in gauges of higher symmetry). The second law of thermodynamics states that in a closed linear system entropy flow can only be positive (or exactly zero at the end of a cycle). However, negative entropy (i.e. increased order, structure or self-organisation) can spontaneously appear in an open nonlinear thermodynamic system that is far from equilibrium, so long as this emergent order accelerates the overall flow of entropy in the total system. The 1977 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to thermodynamicist Ilya Prigogine for his theory of dissipative systems that described this notion. Prigogine described the principle as "order through fluctuations" or "order out of chaos". It has been argued by some that all emergent order in the universe from galaxies, solar systems, planets, weather, complex chemistry, evolutionary biology to even consciousness, technology and civilizations are themselves examples of thermodynamic dissipative systems; nature having naturally selected these structures to accelerate entropy flow within the universe to an ever-increasing degree. For example, it has been estimated that human body is 10,000 times more effective at dissipating energy per unit of mass than the sun.

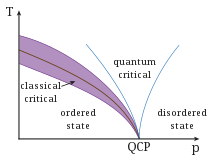

One may query what this has to do with zero-point energy. Given the complex and adaptive behaviour that arises from nonlinear systems considerable attention in recent years has gone into studying a new class of phase transitions which occur at absolute zero temperature. These are quantum phase transitions which are driven by EM field fluctuations as a consequence of zero-point energy. A good example of a spontaneous phase transition that are attributed to zero-point fluctuations can be found in superconductors. Superconductivity is one of the best known empirically quantified macroscopic electromagnetic phenomena whose basis is recognised to be quantum mechanical in origin. The behaviour of the electric and magnetic fields under superconductivity is governed by the London equations. However, it has been questioned in a series of journal articles whether the quantum mechanically canonised London equations can be given a purely classical derivation. Bostick, for instance, has claimed to show that the London equations do indeed have a classical origin that applies to superconductors and to some collisionless plasmas as well. In particular it has been asserted that the Beltrami vortices in the plasma focus display the same paired flux-tube morphology as Type II superconductors. Others have also pointed out this connection, Fröhlich has shown that the hydrodynamic equations of compressible fluids, together with the London equations, lead to a macroscopic parameter ( = electric charge density / mass density), without involving either quantum phase factors or the Planck constant. In essence, it has been asserted that Beltrami plasma vortex structures are able to at least simulate the morphology of Type I and Type II superconductors. This occurs because the "organised" dissipative energy of the vortex configuration comprising the ions and electrons far exceeds the "disorganised" dissipative random thermal energy. The transition from disorganised fluctuations to organised helical structures is a phase transition involving a change in the condensate's energy (i.e. the ground state or zero-point energy) but without any associated rise in temperature. This is an example of zero-point energy having multiple stable states (see Quantum phase transition, Quantum critical point, Topological degeneracy, Topological order) and where the overall system structure is independent of a reductionist or deterministic view, that "classical" macroscopic order can also causally affect quantum phenomena. Furthermore, the pair production of Beltrami vortices has been compared to the morphology of pair production of virtual particles in the vacuum.

The idea that the vacuum energy can have multiple stable energy states is a leading hypothesis for the cause of cosmic inflation. In fact, it has been argued that these early vacuum fluctuations led to the expansion of the universe and in turn have guaranteed the non-equilibrium conditions necessary to drive order from chaos, as without such expansion the universe would have reached thermal equilibrium and no complexity could have existed. With the continued accelerated expansion of the universe, the cosmos generates an energy gradient that increases the "free energy" (i.e. the available, usable or potential energy for useful work) which the universe is able to use to create ever more complex forms of order. The only reason Earth's environment does not decay into an equilibrium state is that it receives a daily dose of sunshine and that, in turn, is due to the sun "polluting" interstellar space with entropy. The sun's fusion power is only possible due to the gravitational disequilibrium of matter that arose from cosmic expansion. In this essence, the vacuum energy can be viewed as the key cause of the structure throughout the universe. That humanity might alter the morphology of the vacuum energy to create an energy gradient for useful work is the subject of much controversy.

Purported applications

Physicists overwhelmingly reject any possibility that the zero-point energy field can be exploited to obtain useful energy (work) or uncompensated momentum; such efforts are seen as tantamount to perpetual motion machines.

Nevertheless, the allure of free energy has motivated such research, usually falling in the category of fringe science. As long ago as 1889 (before quantum theory or discovery of the zero point energy) Nikola Tesla proposed that useful energy could be obtained from free space, or what was assumed at that time to be an all-pervasive aether. Others have since claimed to exploit zero-point or vacuum energy with a large amount of pseudoscientific literature causing ridicule around the subject. Despite rejection by the scientific community, harnessing zero-point energy remains an interest of research, particularly in the US where it has attracted the attention of major aerospace/defence contractors and the U.S. Department of Defense as well as in China, Germany, Russia and Brazil.

Casimir batteries and engines

A common assumption is that the Casimir force is of little practical use; the argument is made that the only way to actually gain energy from the two plates is to allow them to come together (getting them apart again would then require more energy), and therefore it is a one-use-only tiny force in nature. In 1984 Robert Forward published work showing how a "vacuum-fluctuation battery" could be constructed; the battery can be recharged by making the electrical forces slightly stronger than the Casimir force to reexpand the plates.

In 1999, Pinto, a former scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech in Pasadena, published in Physical Review his thought experiment (Gedankenexperiment) for a "Casimir engine". The paper showed that continuous positive net exchange of energy from the Casimir effect was possible, even stating in the abstract "In the event of no other alternative explanations, one should conclude that major technological advances in the area of endless, by-product free-energy production could be achieved."

Garret Moddel at University of Colorado has highlighted that he believes such devices hinge on the assumption that the Casimir force is a nonconservative force, he argues that there is sufficient evidence (e.g. analysis by Scandurra (2001)) to say that the Casimir effect is a conservative force and therefore even though such an engine can exploit the Casimir force for useful work it cannot produce more output energy than has been input into the system.

In 2008, DARPA solicited research proposals in the area of Casimir Effect Enhancement (CEE). The goal of the program is to develop new methods to control and manipulate attractive and repulsive forces at surfaces based on engineering of the Casimir force.