| Revision as of 21:09, 1 June 2009 editBearcat (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators1,564,169 editsm Quick-adding category HIV/AIDS; removed {{uncategorized}} (using HotCat)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:19, 6 June 2024 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,407,825 edits Altered title. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Abductive | Category:Circumcision | #UCB_Category 23/36 | ||

| (915 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Overview of relationship between male circumcision and HIV}} | |||

| {{update}} | |||

| {{About|male circumcision and HIV|female circumcision and HIV|Female genital mutilation#HIV}} | |||

| According to Alcena, it was he who first hypothesised that low rates of circumcision in ] were partly responsible for the continent's ].<ref>{{cite web | |||

| Male ] reduces the risk of ] from HIV positive women to men in high risk populations.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Sharma |first1=Adhikarimayum Lakhikumar |last2=Hokello |first2=Joseph |last3=Tyagi |first3=Mudit |date=2021-06-25 |title=Circumcision as an Intervening Strategy against HIV Acquisition in the Male Genital Tract |journal=Pathogens |volume=10 |issue=7 |pages=806 |doi=10.3390/pathogens10070806 |pmid=34201976 |pmc=8308621 |issn=2076-0817 |quote=There is disputed immunological evidence in support of MC in preventing the heterosexual acquisition of HIV-1.|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last1=Merson |first1=Michael |title=The AIDS Pandemic: Searching for a Global Response |last2=Inrig |first2=Stephen |publisher=] |year=2017 |isbn=9783319471334 |pages=379 |quote=This led to a consensus that male circumcision should be a priority for HIV prevention in countries and regions with heterosexual epidemics and high HIV and low male circumcision prevalence.}}</ref> | |||

| | last = Alcena | |||

| | first = Valiere | |||

| | title = AIDS in Third World countries | |||

| | work = response to "Randomized, Controlled Intervention Trial of Male Circumcision for Reduction of HIV Infection Risk: The ANRS 1265 Trial" | |||

| | publisher = PLos Medicine | |||

| | date = 2006-10-16 | |||

| | url = http://medicine.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=read-response&doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298#r1326 | |||

| | format = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-08-24 }}</ref> He did this via a letter to the New York State Journal of Medicine in August 1986.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Alcena | |||

| | first = Valiere | |||

| | title = AIDS in Third World countries | |||

| | journal = New York State Journal of Medicine | |||

| | volume = 86 | |||

| | issue = 8 | |||

| | pages = 446 | |||

| | year = 1986 | |||

| | month = August | |||

| | url = http://www.popline.org/docs/057476 | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | id = | |||

| | accessdate =2008-08-24 }}.</ref> He also alleges that the late ] stole his idea when Fink published a letter to the ] entitled ''A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS'', in October 1986.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Fink |first=Aaron J. |authorlink=Aaron J. Fink |year=1986 |month=October |title=A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS. |journal=New England Journal of Medicine |volume=315 |issue=18 |pages=1167|pmid=3762636 |url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3762636?dopt=Abstract |accessdate=2008-08-24 |quote= }}</ref> | |||

| In 2020, the ] (WHO) reiterated that male circumcision is an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention if carried out by medical professionals under safe conditions.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV">{{cite web|title=Preventing HIV Through Safe Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision For Adolescent Boys And Men In Generalized HIV Epidemics | |||

| ====Observational studies==== | |||

| |year=2020|publisher=]|url=https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978-92-4-000854-0 |access-date=2021-05-24}}</ref> | |||

| Circumcision reduces the risk that a man will acquire HIV and other ] (STIs) from an infected female partner through ].<ref name="CDCPrevHIV2018">{{cite report|title=Information for providers counseling male patients and parents regarding male circumcision and the prevention of HIV infection, STIs, and other health outcomes|publisher=]|date=August 22, 2018|url=https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/58456|access-date=2021-05-26|archive-date=2021-05-06|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210506034452/https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/58456|url-status=live}}</ref> The evidence regarding whether circumcision helps prevent HIV is not as clear among ] (MSM).<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /> The effectiveness of using circumcision to prevent HIV in the ] is not determined.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /><ref name="kim_2010" /> | |||

| ==Efficacy== | |||

| In 1989 Cameron found uncircumcised men 8.2 times more likely to have ].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Cameron |first=DW |authorlink= |coauthors=Simonsen JN, D'Costa LJ, Ronald AR, Maitha GM, Gakinya MN, Cheang M, Ndinya-Achola JO, Piot P, Brunham RC, et al. |year=1989 |month=August |title=Female to male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: risk factors for seroconversion in men. |journal=Lancet |volume=19 |issue=2(8660) |pages=403–7 |pmid= 2569597 |url= |accessdate= |quote= |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90589-8 }}</ref> Since then over 40 epidemiological studies have been conducted to investigate the relationship between circumcision and HIV infection.<ref name = "Szabo">{{cite journal | |||

| === Heterosexual men === | |||

| | last = Szabo | |||

| {{as of|2020}}, past research has shown that circumcision reduces the risk of HIV infection in heterosexual men, although these studies have had limitations.<ref name="farley">{{cite journal |vauthors=Farley TM, Samuelson J, Grabowski MK, Ameyan W, Gray RH, Baggaley R |title=Impact of male circumcision on risk of HIV infection in men in a changing epidemic context - systematic review and meta-analysis |journal=J Int AIDS Soc |volume=23 |issue=6 |pages=e25490 |date=June 2020 |pmid=32558344 |pmc=7303540 |doi=10.1002/jia2.25490 |type=Review}}</ref> | |||

| | first = Robert | |||

| | coauthors = Roger V. Short | |||

| | year = 2000 | |||

| | month = June | |||

| | title = How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection? | |||

| | journal = BMJ | |||

| | volume = 320 | |||

| | issue = 7249 | |||

| | pages = 1592–1594 | |||

| | doi = 10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592 | |||

| | pmid = 10845974 | |||

| | url = http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/reprint/320/7249/1592 | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| | accessdate = 2006-07-09 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| The WHO Expert Group on Models To Inform Fast Tracking Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision In HIV Combination Prevention in 2016 found "large benefits" of circumcision in settings with high HIV prevalence and low circumcision prevalence. The Group estimated male circumcision is cost-saving in almost all high priority countries. Furthermore, WHO stated that: "While circumcision reduces a man’s individual lifetime HIV risk, the indirect effect of preventing further HIV transmissions to women, their babies (vertical transmission) and from women to other men has an even greater impact on the population incidence, particularly for circumcisions performed at younger ages (under age | |||

| In 1994, de Vincenzi and Mertens surveyed previous studies that had links between circumcision status and HIV; they surveyed 23 in total. They criticised the Cameron study saying that it may have suffered from selection bias.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| 25 years)."<ref name="WHOModel2016">{{cite web |title=Models To Inform Fast Tracking Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision In HIV Combination Prevention | |||

| | last = de Vincenzi | |||

| |publisher=World Health Organization |date=March 2016 |url=https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259706/WHO-HIV-2017.39-eng.pdf|access-date=2021-05-26 |archive-date=2020-09-23 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200923203154/https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259706/WHO-HIV-2017.39-eng.pdf|url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | first = Isabelle | |||

| | coauthors = Thierry Mertens | |||

| | year = 1994 | |||

| | month = February | |||

| | title = Male circumcision: a role in HIV prevention? | |||

| | journal = AIDS | |||

| | volume = 8 | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | pages = 153–160 | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | pmid = 8043224 | |||

| | url = http://www.cirp.org/library/disease/HIV/vincenzi/ | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-10-16 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Newly circumcised HIV infected men who are not taking ] can ] the HIV virus from the circumcision wound, thus increasing the immediate risk of HIV transmission to female partners.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /> This risk of post-operative transmission presents a challenge, although in the long-term it is possible the circumcision of HIV-infected men helps lessen heterosexual HIV transmission overall. Such viral shedding can be mitigated by the use of antiretroviral drugs.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Tobian AA, Adamu T, Reed JB, Kiggundu V, Yazdi Y, Njeuhmeli E |title=Voluntary medical male circumcision in resource-constrained settings |journal=Nat Rev Urol |volume=12 |issue=12 |pages=661–70 |date=December 2015 |pmid=26526758 |doi=10.1038/nrurol.2015.253 |s2cid=10432723 |type=Review}}</ref> Additional research is needed to ascertain the existence and potential risk of viral shedding from circumcision wounds. | |||

| In 1995 Ntozi noted: "There are now two schools of thought about the link between lack of circumcision and HIV infection in Africa. One school is that of Bongaarts et al. (1989), Moses et al. (n.d.) and Caldwell and Caldwell (1994) who use geographical distribution evidence to argue that the association between lack of circumcision and a high level of HIV infection in Africa is so convincing that the likelihood of a link should be recognized and taken into account where possible in the battle against AIDS. Moses et al. (n.d.) have gone further to recommend circumcision interventions for Africa. In contrast, De Vincenzi and Mertens (1994) argue that the evidence for an association, at least from small-scale surveys, is doubtful and hence not conclusive enough to qualify circumcision as an intervention.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Ndozi | |||

| | first = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | year = 1995 | |||

| | month = April | |||

| | title = The East African AIDS epidemic and the absence of male circumcision: what is the link? Using circumcision to prevent HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: the view of an African | |||

| | journal = Health transission review | |||

| | volume = 5 | |||

| | issue = 1 | |||

| | pages = 97–117 | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | pmid = | |||

| | url = http://htc.anu.edu.au/pdfs/Forum5_1.pdf | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-10-18 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ===Men who have sex with men=== | |||

| Van Howe conducted a meta-analysis in 1999 and found circumcised men at a greater risk for HIV infection.<ref name="VanHoweHIVmeta">{{cite journal |last= Van Howe |first=R.S. |authorlink= |coauthors= |year= 1999|month= January |title=Circumcision and HIV infection: review of the literature and meta-analysis |journal=International Journal of STD's and AIDS |volume=10 |issue= |pages=8–16 |id= |doi= |url=http://www.cirp.org/library/disease/HIV/vanhowe4/ |accessdate= 2008-09-23 |quote=Thirty-five articles and a number of abstracts have been published in the medical literature looking at the relationship between male circumcision and HIV infection. Study designs have included geographical analysis, studies of high-risk patients, partner studies and random population surveys. Most of the studies have been conducted in Africa. A meta-analysis was performed on the 29 published articles where data were available. When the raw data are combined, a man with a circumcised penis is at greater risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV than a man with a non-circumcised penis (odds ratio (OR)=1.06, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.01-1.12). Based on the studies published to date, recommending routine circumcision as a prophylactic measure to prevent HIV infection in Africa, or elsewhere, is scientifically unfounded.}}</ref> He further speculated that circumcision may be responsible for the increased number of partners, and therefore, the increased risk. Van Howe's work was reviewed by O'Farrell and Egger (2000) who said Van Howe used an inappropriate method for combining studies, stating that re-analysis of the same data revealed that the presence of the foreskin was associated with increased risk of HIV infection (fixed effects OR 1.43, 95%CI 1.32 to 1.54; random effects OR 1.67, 1.25 to 2.24).<ref>{{cite journal |author=O'Farrell N, Egger M |title=Circumcision in men and the prevention of HIV infection: a 'meta-analysis' revisited |journal=Int J STD AIDS |volume=11 |issue=3 |pages=137–42 |year=2000 |month=March |pmid=10726934 |url=http://ijsa.rsmjournals.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10726934 |quote=The results from this re-analysis thus support the contention that male circumcision may offer protection against HIV infection, particularly in high-risk groups where genital ulcers and other STDs 'drive' the HIV epidemic. A systematic review is required to clarify this issue. Such a review should be based on an extensive search for relevant studies, published and unpublished, and should include a careful assessment of the design and methodological quality of studies. Much emphasis should be given to the exploration of possible sources of heterogeneity. In view of the continued high prevalence and incidence of HIV in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the question of whether circumcision could contribute to prevent infections is of great importance, and a sound systematic review of the available evidence should be performed without delay.}}</ref> Moses ''et al.'' (1999) also criticised Van Howe's paper, stating that his results were a case of "Simpson's paradox, which is a type of confounding that can occur in epidemiological analyses when data from different strata with widely divergent exposure levels are combined, resulting in a combined measure of association that is not consistent with the results for each of the individual strata." They concluded that, contrary to Van Howe's assertion, the evidence that lack of circumcision increases the risk of HIV "appears compelling".<ref>{{cite journal |author=Moses S, Nagelkerke NJ, Blanchard J |title=Analysis of the scientific literature on male circumcision and risk for HIV infection |journal=International journal of STD & AIDS |volume=10 |issue=9 |pages=626–8 |year=1999 |month=September |pmid=10492434 |doi= |url=http://ijsa.rsmjournals.com/cgi/reprint/10/9/626?ijkey=a1ca8d961969d1a6970456a1a43f7ac7aa24304a&keytype2=tf_ipsecsha | format= PDF}}</ref> | |||

| The ] does not recommend circumcision as protection against male to male HIV transmission, as evidence is lacking in regards to receptive anal intercourse. The WHO also states that ] should not be excluded from circumcision services in countries in eastern and southern ], and that circumcision may be effective at limiting the spread of HIV for MSM if they also engage in vaginal sex with women.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /> | |||

| ===Regional differences=== | |||

| Weiss, Quigley and Hayes carried a meta-analysis on circumcision and HIV in 2000<ref name=Weiss2000>{{cite journal | |||

| Whether circumcision is beneficial to developed countries for HIV prevention purposes is undetermined.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /><ref name="kim_2010">{{cite journal |vauthors=Kim HH, Li PS, Goldstein M |title=Male circumcision: Africa and beyond? |journal=Curr Opin Urol |volume=20 |issue=6 |pages=515–9 |date=November 2010 |pmid=20844437 |doi=10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833f1b21 |s2cid=2158164 |url=}}</ref> It is not known whether the effect of male circumcision differs by HIV-1 variant. The predominant subtype of HIV-1 in the ] is subtype B, and in Africa, the predominant subtypes are A, C, and D.<ref>{{Cite journal|doi = 10.1186/s12301-019-0005-2|title = Male circumcision and global HIV/AIDS epidemic challenges|year = 2019|last1 = Olapade-Olaopa|first1 = Emiola Oluwabunmi|last2 = Salami|first2 = Mudasiru Adebayo|last3 = Lawal|first3 = Taiwo Akeem|journal = African Journal of Urology|volume = 25|s2cid = 208085886|doi-access = free}}</ref> | |||

| | last = Weiss | |||

| | first = H.A. | |||

| | coauthors= Quigley M.A., Hayes R.J. | |||

| | year = 2000 | |||

| | month = October | |||

| | title = Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis | |||

| | journal = AIDS | |||

| | volume = 14 | |||

| | issue = 15 | |||

| | pages = 2361–70 | |||

| | pmid = 11089625 | |||

| | url = http://www.aidsonline.com/pt/re/aids/pdfhandler.00002030-200010200-00018.pdf;jsessionid=L57hvrjhsS0JsXGZmmHZ2gpTTbZ7x5wqJh2CTXFDpNvpC8rNxmL1!949623904!181195628!8091!-1 | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-09-25 | |||

| }}</ref> and found as follows: "Male circumcision is associated with a significantly reduced risk of HIV infection among men in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly those at high risk of HIV. These results suggest that consideration should be given to the acceptability and feasibility of providing safe services for male circumcision as an additional HIV prevention strategy in areas of Africa where men are not traditionally circumcised." | |||

| ==Recommendations== | |||

| The USAID document summarised research as of September 2002. It states: | |||

| <!-- dummy edit; can be deleted. --> | |||

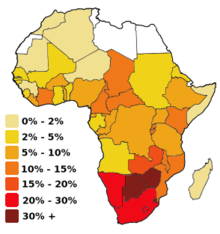

| The most recent WHO review of the evidence reiterates prior estimates of the impact of male circumcision on HIV incidence rates. In 2020, WHO again concluded that male circumcision is an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention and that the promotion of male circumcision is an essential strategy, in addition to other preventive measures, for the prevention of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men. Eastern and southern Africa had a particularly low prevalence of circumcised males. This region has a disproportionately high HIV infection rate, with a significant | |||

| number of those infections stemming from heterosexual transmission. | |||

| The WHO has made voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) a priority intervention in that region since their 2007 recommendations.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /> | |||

| {{blockquote|text=Although these results confirm that male circumcision reduces the risk of men becoming infected with HIV, the UN agencies emphasize that it does not provide complete protection against HIV infection. Circumcised men can still become infected with the virus and, if HIV-positive, can infect their sexual partners. Male circumcision should never replace other known effective prevention methods and should always be considered as part of a comprehensive prevention package, which includes correct and consistent use of male or female condoms, reduction in the number of sexual partners, delaying the onset of sexual relations, and HIV testing, counseling, and treatment.|author=World Health Organization|source=Joint WHO/UNAIDS Statement made in 2007.<ref name="WHOsec">{{cite press release | url = https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2007/s04/en/index.html | title = WHO and UNAIDS Secretariat welcome corroborating findings of trials assessing impact of male circumcision on HIV risk | access-date = 2007-02-23 | date = February 23, 2007 | publisher = World Health Organization | archive-date = 2007-02-26 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070226135123/http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2007/s04/en/index.html | url-status = dead }}</ref>}} | |||

| In the United States, the ] (AAP) led a 2012 task force which included the ] (AAFP), the ] (ACOG), and the ] (CDC). The task force concluded that circumcision may be helpful for the prevention of HIV in the United States.<ref name="AAP_2012">{{cite journal |author=American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision |title=Technical Report |journal=Pediatrics |volume=130 |issue=3 |year=2012 |pages=e756–e785 |issn=0031-4005 |pmid=22926175 |doi=10.1542/peds.2012-1990 |url=http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/3/e756.full |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120920054623/http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/3/e756.full |archive-date=2012-09-20 |doi-access=free }}</ref> The CDC 2018 position on circumcision and HIV recommended that circumcision should continue to be offered to parents who are ] of the benefits and risks, including a potential reduction in risk of HIV transmission. The position asserts that circumcision conducted after sexual debut can result in missed opportunities for HIV prevention.<ref name="CDCPrevHIV2018" /> | |||

| :A systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 published studies by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, published in the journal AIDS in 2000, found that circumcised men are less than half as likely to be infected by HIV as uncircumcised men. A subanalysis of 10 African studies found a 71 percent reduction among higher-risk men. A September 2002 update considered the results of these 28 studies plus an additional 10 studies and, after controlling for various potentially confounding religious, cultural, behavioral, and other factors, had similarly robust findings. Recent laboratory studies in Chicago found HIV uptake in the inner foreskin tissue to be up to nine times more efficient than in a control sample of cervical tissue.<ref>{{cite conference | |||

| | last = USAID/AIDSMark | |||

| | title = Conference Report | |||

| | booktitle = Program and Policy Implications For HIV Prevention and Reproductive Health | |||

| | pages = 1–48 | |||

| | publisher = USAID/AIDSMark | |||

| | date = 18-19 September, 2002 | |||

| | location = Washington, DC | |||

| | url = http://www.psi.org/resources/pubs/male-circ.pdf | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-10-04 | |||

| | id = | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Because the evidence that circumcision prevents HIV mainly comes from studies conducted in Africa, the ] (KNMG) questioned the applicability of those studies to developed countries. Circumcision has not been included in their HIV prevention recommendations. The KNMG circumcision policy statement was endorsed by several Dutch medical associations. The policy statement was initially released in 2010, but was reviewed again and accepted in 2022.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Non-therapeutic circumcision of male minors KNMG viewpoint|url=https://www.knmg.nl/advies-richtlijnen/dossiers/jongensbesnijdenis|date=31 March 2022}}</ref> | |||

| Siegried ''et al.'' (2003) surveyed 35 observational studies relating to HIV and circumcision: 16 conducted in the general population and 19 in high-risk populations. | |||

| ==Mechanism of action== | |||

| :We found insufficient evidence to support an interventional effect of male circumcision on HIV acquisition in heterosexual men. The results from existing observational studies show a strong epidemiological association between male circumcision and prevention of HIV, especially among high-risk groups. However, observational studies are inherently limited by confounding which is unlikely to be fully adjusted for. In the light of forthcoming results from RCTs, the value of IPD analysis of the included studies is doubtful. The results of these trials will need to be carefully considered before circumcision is implemented as a public health intervention for prevention of sexually transmitted HIV.<ref name="Siegfried2003">{{cite journal |author=Siegfried N, Muller M, Volmink J, ''et al'' |title=Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men |journal=Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) |volume= |issue=3 |pages=CD003362 |year=2003 |pmid=12917962 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD003362 |url=}}</ref> | |||

| While the biological mechanism of action is not known, a 2020 meta-analysis stated "the consistent protective effect suggests that the reasons for the heterogeneity lie in concomitant individual social and medical factors, such as presence of STIs, rather than a different biological impact of circumcision."<ref name="farley" /> The inner foreskin harbours an increased density of CD4 T-cells and releases increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Hence the sub-preputial space displays a pro-inflammatory environment, conducive to HIV infection.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Prodger |first1=Jessica L. |title=The biology of how circumcision reduces HIV susceptibility: broader implications for the prevention field |journal=AIDS Research and Therapy |date=September 2017 |volume=14 |issue=1 |page=49 |doi=10.1186/s12981-017-0167-6|pmid=28893286 |pmc=5594533 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ]s (part of the human immune system) under the foreskin may be a source of entry for HIV.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Weiss HA, Dickson KE, Agot K, Hankins CA | title = Male circumcision for HIV prevention: current research and programmatic issues | journal = AIDS | volume = 24 | issue = Suppl 4 | pages = S61-9 | date = October 2010 | pmid = 21042054 | pmc = 4233247 | doi = 10.1097/01.aids.0000390708.66136.f4 | type = Randomized controlled trial }}</ref> Excising the foreskin removes what is thought to be a main entry point for the HIV virus.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Szabo R, Short RV |title=How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection? |journal=BMJ |volume=320 |issue=7249 |pages=1592–4 |date=June 2000 |pmid=10845974 |pmc=1127372 |doi=10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592 |type=Review}}</ref> | |||

| In 2005, Siegfried ''et al.'' published a review including in which 37 observational studies were included. Most studies indicated an association between lack of circumcision and increased risk of HIV, but the quality of evidence was judged insufficient to warrant implementation of circumcision as a public health measure. The authors stated that the results of the three randomised controlled trials then underway would therefore provide essential evidence about the effects of circumcision as an HIV intervention.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks J, ''et al'' |title=HIV and male circumcision--a systematic review with assessment of the quality of studies |journal=The Lancet infectious diseases |volume=5 |issue=3 |pages=165–73 |year=2005 |month=March |pmid=15766651 |doi=10.1016/S1473-3099(05)01309-5 |url=}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Kiwanuka ''et al.'''s (1996) study on the relationship between religion and HIV in Rural Uganda was presented at the 1996 10th ''International AIDS Conference'' He said that: "Lower rates of HIV infection among ]s appear to be associated with less ] consumption, ] and fewer sexual partners, whereas the low HIV prevalence in ]s appears to be associated with low reported alcohol consumption and male circumcision." Muslims, despite having the lowest rate of sexual abstinence and the highest rate of having two or more sexual partners, had the lowest level of HIV infection compared with the other religious groups in the study (]s, ]s, and Pentecostals). The factor in common between the Muslims (14.5% seropositive) and the Pentecostals (14.6% seropositive) was the lower alcohol consumption rate in these two groups than amongst Protestants (19.2%) and Catholics (19.9%).<ref>{{cite conference | |||

| ] based on 1999–2001 figures]] | |||

| | first = Noah | |||

| | last = Kiwanuka | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = Gray R., Sewankambo N.K., Serwadda D., Wawer M., Li C. | |||

| | title = International Conference AIDS. | |||

| | booktitle = Religion, behaviours, and circumcision as determinants of HIV dynamics in rural Uganda | |||

| | pages = | |||

| | publisher = | |||

| | date = 7-12 July, 1996 | |||

| | location = ], ] | |||

| | url = http://gateway.nlm.nih.gov/MeetingAbstracts/ma?f=102221633.html | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-09-25 | |||

| | id = | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Valiere Alcena, in a 1986 letter to the ''New York State Journal of Medicine,'' noted that low rates of circumcision in parts of Africa had been linked to the ].<ref name="taken">{{cite journal | type = Comment | vauthors = Alcena V | title = AIDS in Third World countries | journal = PLOS Medicine | date = 19 October 2006 | volume = 86 | issue = 8 | page = 446 | pmid = 3463895 | url = http://www.plosmedicine.org/annotation/listThread.action?root=15231 | access-date = 10 January 2014 | archive-date = 10 January 2014 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140110204325/http://www.plosmedicine.org/annotation/listThread.action?root=15231 | url-status = dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |type = Letter |vauthors = Alcena V |title = AIDS in Third World countries |journal = New York State Journal of Medicine |volume = 86 |issue = 8 |pages = 446 |date = August 1986 |pmid = 3463895 |url = http://www.popline.org/node/363663 |access-date = 2014-01-10 |archive-date = 2014-01-10 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140110194304/http://www.popline.org/node/363663 |url-status = live }}</ref> Aaron J. Fink several months later also proposed that circumcision could have a preventive role when the '']'' published his letter, "A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS," in October, 1986.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fink AJ | title = A possible explanation for heterosexual male infection with AIDS | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 315 | issue = 18 | pages = 1167 | date = October 1986 | pmid = 3762636 | doi = 10.1056/nejm198610303151818 | type = Letter }}</ref> By 2000, over 40 epidemiological studies had been conducted to investigate the relationship between circumcision and HIV infection.<ref name="Szabo">{{cite journal | vauthors = Szabo R, Short RV | title = How does male circumcision protect against HIV infection? | journal = BMJ | volume = 320 | issue = 7249 | pages = 1592–4 | date = June 2000 | pmid = 10845974 | pmc = 1127372 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1592 | type = Review }}</ref> A meta-analysis conducted by researchers at the ] examined 27 studies of circumcision and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and concluded that these showed circumcision to be "associated with a significantly reduced risk of HIV infection" that could form part of a useful public health strategy.<ref name="Weiss2000">{{cite journal | vauthors = Weiss HA, Quigley MA, Hayes RJ | s2cid = 21857086 | title = Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis | journal = AIDS | volume = 14 | issue = 15 | pages = 2361–70 | date = October 2000 | pmid = 11089625 | doi = 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00018 | url = http://www.aidsonline.com/pt/re/aids/pdfhandler.00002030-200010200-00018.pdf | url-status = dead | type = Meta-analysis | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140110151608/http://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/Fulltext/2000/10200/Male_circumcision_and_risk_of_HIV_infection_in.18.aspx | archive-date = 2014-01-10 }}</ref> A 2005 review of 37 observational studies expressed reservations about the conclusion because of possible ]s, since all studies to date had been observational as opposed to ]s. The authors stated that three randomized controlled trials then underway in Africa would provide "essential evidence" about the effects of circumcision on preventing HIV.<ref name="Siegfried2005">{{cite journal | vauthors = Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks J, Volmink J, Egger M, Low N, Walker S, Williamson P | display-authors = 6 | title = HIV and male circumcision--a systematic review with assessment of the quality of studies | journal = The Lancet. Infectious Diseases | volume = 5 | issue = 3 | pages = 165–73 | date = March 2005 | pmid = 15766651 | doi = 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)01309-5 | type = Review }}</ref> | |||

| Kelly ''et al.'' (1999) investigated the age of male circumcision and risk of prevalent HIV infection in rural Uganda and found that circumcision before the age of 12 resulted in a reduction to 0.39 of the odds of being infected. The degree of protection varied with the age at which circumcision was performed. Those circumcised at between 13 and 20 years had an odds ratio of 0.46, and those circumcised after the age of 20 at an odds ratio of 0.78. They concluded: "Prepubertal circumcision is associated with reduced HIV risk, whereas circumcision after age 20 years is not significantly protective against HIV-1 infection."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| |author=Kelly R, Kiwanuka N, Wawer MJ, ''et al'' |title=Age of male circumcision and risk of prevalent HIV infection in rural Uganda |journal=AIDS |volume=13 |issue=3 |pages=399–405 |year=1999 |month=February |pmid=10199231 |url=http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0269-9370&volume=13&issue=3&spage=399}}</ref> | |||

| Experimental evidence was needed to establish a causal relationship, so three ]s (RCT) were commissioned as a means to reduce the effect of any confounding factors. Trials took place in ], ] and ].<ref name=":1">{{cite journal |vauthors=Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J |date=April 2009 |title=Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men |journal=The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |issue=2 |pages=CD003362 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2 |pmid=19370585 |veditors=Siegfried N}}</ref> All three trials were stopped early by their monitoring boards because those in the circumcised group had a substantially lower rate of HIV incidence than the control group, and hence it was seen as unethical to withhold the procedure, in light of strong evidence of efficacy.<ref name=":1" /> In 2009, a ] which included the results of the three ]s found "strong" evidence that the acquisition of HIV by a man during sex with a woman was decreased by 54% (], 38% to 66%) over 24 months if the man was circumcised. The review also found a low incidence of adverse effects from circumcision in the trials reviewed.<ref name="Cochrane2009">{{cite journal |last1=Siegfried |first1=Nandi |last2=Muller |first2=Martie |last3=Deeks |first3=Jonathan J |last4=Volmink |first4=Jimmy |title=Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men |journal=Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |date=15 April 2009 |issue=2 |pages=CD003362 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2|pmid=19370585 }}</ref> WHO assessed the trials as "gold standard" studies and found "strong and consistent" evidence from later studies that confirmed the results.<ref name="WHO-PrevHIV" /> In 2020, a review including post-study follow up from the three randomized controlled trials, as well as newer observational studies, found a 59% relative reduction in HIV incidence, and 1.31% absolute decrease across the three randomized controlled trials, as well as continued protection for up to 6 years after the studies began.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Farley |first1=Timothy MM |last2=Samuelson |first2=Julia |last3=Grabowski |first3=M Kate |last4=Ameyan |first4=Wole |last5=Gray |first5=Ronald H |last6=Baggaley |first6=Rachel |title=Impact of male circumcision on risk of HIV infection in men in a changing epidemic context – systematic review and meta-analysis |journal=Journal of the International AIDS Society |date=June 2020 |volume=23 |issue=6 |pages=e25490 |doi=10.1002/jia2.25490|pmid=32558344 |pmc=7303540 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| Buvé and colleagues (1999) investigated the reasons why the HIV prevalence rate among pregnant women in many large towns in Central, East and southern Africa was higher (>30%) than in the cities and towns of most of West Africa (<10%). Between June 1997 and March 1998 surveys were carried out and blood samples were taken in 4 sites. Kisumu (Kenya) and Ndola (Zambia), in Central/East Africa, were selected as the towns with high HIV prevalence, while the low-prevalence towns in West Africa were Cotonou (Benin) and Yaoundé (Cameroon). "In conclusion, differences in the rate of HIV spread between the East African and West African cities studied cannot be explained away by differences in sexual behaviour alone. In fact, behavioural differences seem to be outweighed by differences in HIV transmission probability."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Buvé | |||

| | first = Anne | |||

| | coauthors= M. Laga, E. Van Dyck, W. Janssens, L. Heyndricks; S. Anagonou ; M. Laourou; L. Kanhonou; Evina Akam, M. de Loenzien ; S-C. Abega ; Zekeng ; J. Chege ; V Kimani, J Olenja ; M Kahindo; F. Kaona, R Musonda, T. Sukwa ; N. Rutenberg ; B Auvert, E Lagarde ; B Ferry, N Lydié ; R. Hayes, L Morison, H Weiss, J. Glynn ; N.J. Robinson ; M. Caraël | |||

| | year = 1999 | |||

| | month = September | |||

| | title = Differences in HIV spread in four sub-Saharan African cities | |||

| | journal = UNAIDS | |||

| | volume = | |||

| | issue = | |||

| | pages = UNAIDS fact sheet | |||

| | pmid = | |||

| | url = http://data.unaids.org/Publications/IRC-pub03/lusaka99_en.html | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-09-25 | |||

| | nopp = true | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Buvé | |||

| | first = Anne | |||

| | coauthors= Carael M., Hayes R. J., Auvert B., Ferry B., Robinson N. J., Anagonou S., Kanhonou L., Laourou M., Abega S., Akam E., Zekeng L., Chege J., Kahindo M., Rutenberg N., Kaona F., Musonda R., Sukwa T., Morison L., Weiss H, A., Laga M. | |||

| | year = 2001 | |||

| | month = August | |||

| | title = Multicentre study on factors determining differences in rate of spread of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: methods and prevalence of HIV infection | |||

| | journal = AIDS | |||

| | volume = 15 | |||

| | issue = Supplement 4 | |||

| | pages = S5–S14 | |||

| | pmid = | |||

| | url = http://www.aidsonline.com/pt/re/aids/pdfhandler.00002030-200108004-00002.pdf;jsessionid=LbgSyTLVTgklp7Ns1JPGXpczTGPLmS80XKGVQtY1rtwgrGTPXBNt!1455807198!181195628!8091!-1 | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-09-25 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| == Society and culture == | |||

| Bailey et al. (1999) interviewed 188 circumcised and 177 uncircumcised consenting Ugandan men in one of four native languages during April and May, 1997. Non-] circumcised men were found to have a higher risk profile than uncircumcised men. Muslims generally had a lower risk profile than other circumcised men except they were less likely to have ever used a condom or to have used a condom during the last sex encounter. Bailey et al. concluded that "these results suggest that differences between circumcised and uncircumcised men in their sex practices and hygienic behaviors do not account for the higher risk of HIV infection found among uncircumcised men. Further consideration should be given to male circumcision as a prevention strategy in areas of high prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Studies of the feasibility and acceptability of male circumcision in traditionally non-circumcising societies are warranted."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| ] became the 1 millionth VMMC against HIV/AIDS transmission in the ] of ], ] in 2018.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Seeth |first=Avantika |date=June 1, 2018 |title='It's hassle-free,' says actor Melusi Yeni about his medical circumcision |url=https://www.news24.com/citypress/news/its-hassle-free-says-actor-melusi-yeni-about-his-medical-circumcision-20180601 |access-date=September 6, 2022|website=] |language=en-US |quote=Actor Melusi Yeni was the millionth man to undergo voluntary male medical circumcision at the Sivananda Clinic in KwaZulu-Natal.}}</ref>]]The WHO recommends VMMC, as opposed to traditional circumcision. There is some evidence that traditionally circumcised men (i.e. who have been circumcised by a person who is not medically trained) use condoms less often and have higher numbers of sexual partners, increasing their risk of contracting HIV.{{r|WHO-PrevHIV|p=3/42}} Newly circumcised men must refrain from sexual activity until the wounds are fully healed.<ref name=WHO-PrevHIV/> | |||

| |author=Bailey RC, Neema S, Othieno R |title=Sexual behaviors and other HIV risk factors in circumcised and uncircumcised men in Uganda |journal=J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. |volume=22 |issue=3 |pages=294–301 |year=1999 |month=November |pmid=10770351 |url=http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=1525-4135&volume=22&issue=3&spage=294}}</ref> | |||

| The prevalence of circumcision varies across Africa.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Marck J | title = Aspects of male circumcision in sub-equatorial African culture history | journal = Health Transition Review | volume = 7 Suppl | issue = Suppl | pages = 337–60 | year = 1997 | pmid = 10173099 | url = http://htc.anu.edu.au/pdfs/Marck1.pdf | access-date = 2009-03-23 | url-status = dead | type = Review | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080906115430/http://htc.anu.edu.au/pdfs/Marck1.pdf | archive-date = 2008-09-06 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|year=2007|title=Male circumcision: global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability|journal=Who/Unaids|url=http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241596169_eng.pdf|access-date=2008-10-16|archive-date=2015-07-15|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150715135808/http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241596169_eng.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> Studies were conducted to assess the acceptability of promoting circumcision; in 2007, country consultations and planning to scale up male circumcision programmes took place in ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite journal | year = 2008 | title = Towards Universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector | journal = Who/Unaids/Unicef | pages = 75 | url = http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdf | access-date = 2008-10-16 | archive-date = 2008-10-18 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20081018050047/http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdf | url-status = live }}</ref> | |||

| Bonner (2001) reserved caution over using circumcision to prevent HIV: "Until we know why and how circumcision is protective, exactly what the relationship is between circumcision status and other STIs, and whether the effect | |||

| seen in high-risk populations is generalisable to other groups, the wisest course is to recommend risk | |||

| reduction strategies of proven efficacy, such as condom use."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Bonner | |||

| | first = Kate | |||

| | year = 2001 | |||

| | month = November | |||

| | title = Male circumcision as an HIV control strategy: not a 'natural condom'. | |||

| | journal = Reproductive health matters | |||

| | volume = 9 | |||

| | issue = 18 | |||

| | pages = 143–155 | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | pmid = | |||

| | url = http://www.rhmjournal.org.uk/PDFs/18bonner.pdf | |||

| |format=PDF| accessdate = 2008-10-08 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ===Programs=== | |||

| At the 14th International AIDS conference in 2002, Changedia and Gilada reported that "Though circumcision offers protection in acquisition of HIV infection, our findings reveal that it does not reduce transmission of HIV in conjugal settings."<ref>{{cite conference | |||

| In 2011, UNAIDS prioritized 15 high HIV prevalence countries in eastern and southern Africa, with a goal of circumcising 80% of men (20.8 million) by the end of 2016.<ref name="UNAIDS"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170729033902/http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2686_WAD2014report_en.pdf |date=2017-07-29 }} WHO. 2014.</ref> As of 2020, WHO estimated that 250,000 HIV infections have been averted by the 23 million circumcisions conducted in the 15 priority countries of eastern and southern Africa.<ref name=WHO-PrevHIV /> | |||

| | first = S.M | |||

| | last = Changedia | |||

| | coauthors = Gilada I.S. | |||

| | title = International Conference AIDS. | |||

| | booktitle = Religion, behaviours, and circumcision as determinants of HIV dynamics in rural Uganda | |||

| | pages = | |||

| | publisher = aegis.com | |||

| | date = 7-12 July, 2002 | |||

| | location = ], ] | |||

| | url = http://www.aegis.com/conferences/iac/2002/ThPeC7420.html | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-10-04 | |||

| | id = | |||

| }}</ref> Hunter ''et al.'' (1994), however, report that "Women whose husband or usual sex partner was uncircumcised had a threefold increase in risk of HIV, and this risk was present in almost all strata of potential confounding factors."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Hunter | |||

| | first = D.J | |||

| | coauthors = Maggwa BN, Mati JK, Tukei PM, Mbugua S | |||

| | year = 1994 | |||

| | month = January | |||

| | title = Sexual behavior, sexually transmitted diseases, male circumcision and risk of HIV infection among women in Nairobi, Kenya | |||

| | journal = AIDS | |||

| | volume = 8 | |||

| | issue = 1 | |||

| | pages = 93–99 | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | pmid = 8011242 | |||

| | url = http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=3925955 | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-10-04 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> Fonck ''et al.'' (2000) reported that "Partners of circumcised men had less-prevalent HIV infection."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Fonck | |||

| | first = K. | |||

| | coauthors = Kidula N, Kirui P, Ndinya-Achola J, Bwayo J, Claeys P, Temmerman M | |||

| | year = 2000 | |||

| | month = August | |||

| | title = Pattern of sexually transmitted diseases and risk factors among women attending an STD referral clinic in Nairobi, Kenya | |||

| | journal = Sexually transmitted diseases | |||

| | volume = 27 | |||

| | issue = 7 | |||

| | pages = 417–423 | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | pmid = 10949433 | |||

| | url = http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=1455493 | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-10-04 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| == See also == | |||

| The prevalence of circumcision varies across Africa.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| {{Portal|Human sexuality}} | |||

| | last = Marck | |||

| * ] | |||

| | first = Jeff | |||

| | coauthors= | |||

| | year = 1997 | |||

| | title = Aspects of male circumcision in subequatorial African culture history | |||

| | journal = Health Transition Review | |||

| | volume = 7 | |||

| | issue = Supplement | |||

| | pages = 337–60 | |||

| | pmid = 10173099 | |||

| | url = http://htc.anu.edu.au/pdfs/Marck1.pdf | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-10-16 | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = | |||

| | first = | |||

| | coauthors= | |||

| | year = 2007 | |||

| | title = Male circumcision: global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability | |||

| | journal = Who/Unaids | |||

| | volume = | |||

| | issue = | |||

| | pages = | |||

| | pmid = | |||

| | url = http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241596169_eng.pdf | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-10-16 | |||

| }}</ref>Studies have been conducted to assess the acceptability of promoting circumcision in place where they traditionally do not circumcise. In 2007, country consultations and planning to scale up male circumcision programmes took place in ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = | |||

| | first = | |||

| | coauthors= | |||

| | year = 2008 | |||

| | title = Towards Universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector | |||

| | journal = Who/Unaids/Unicef | |||

| | volume = | |||

| | issue = | |||

| | pages = 75 | |||

| | pmid = | |||

| | url = http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/towards_universal_access_report_2008.pdf | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-10-16 | |||

| }}</ref> Kebaabetswe ''et al.'' carried out interviews in nine geographically representative locations to determine the acceptability of male circumcision as well as the preferred age and setting for male circumcision in Botswana. Their conclusion was "Male circumcision appears to be highly acceptable in Botswana. The option for safe circumcision should be made available to parents in Botswana for their male children. Circumcision might also be an acceptable option for adults and adolescents, if its efficacy as an HIV prevention strategy among sexually active people is supported by clinical trials."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Kebaabetswe | |||

| | first = P. | |||

| | coauthors= S. Lockman, S. Mogwe, R. Mandevu, I Thior, M Essex, R. L. Shapiro | |||

| | year = 2003 | |||

| | month = | |||

| | title = Male circumcision: an acceptable strategy for HIV prevention in Botswana | |||

| | journal = Sexually Transmitted Infections | |||

| | volume = 79 | |||

| | issue = | |||

| | pages = 214–219 | |||

| | pmid = | |||

| | url = http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1744675&blobtype=pdf | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-09-25 | |||

| }}</ref> Boyle criticised Kebaabetswe ''et al.'''s proposal to introduce infant circumcision to Botswana saying that: "The proposal by Kebaabetswe and colleagues for the introduction of circumcision into Botswana is seriously flawed, and is irresponsible in failing to place the emphasis on safe sex practices. As described here, there are many medical, sexual, psychological, social, human rights, ethical, and legal aspects that must be considered. Reliance on circumcision to prevent HIV transmission is wishful fantasy, and can only result in a calamitous worsening of the HIV-AIDS epidemic."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Boyle | |||

| | first = G. J. | |||

| | coauthors= | |||

| | year = 2003 | |||

| | month = November | |||

| | title = Issues associated with the introduction of circumcision into a non-circumcising society | |||

| | journal = Sexually transmitted infections | |||

| | volume = 79 | |||

| | issue = 5 | |||

| | pages = 427–428 | |||

| | pmid = | |||

| | doi = 10.1136/sti.79.5.427 | |||

| | url = http://www.cirp.org/library/disease/HIV/boyle-sti/ | |||

| | format = | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| == References == | |||

| Bailey ''et al.'' looked at the possible adverse effects of introducing male circumcision on a public health scale and the post operative satisfaction levels of 380 circumcisions on 18-24 year old consenting men. As to satisfaction; "At 30 days post-surgery, 99.3% of men reported being very satisfied and 0.7% somewhat satisfied with circumcision. None were dissatisfied." And with regard to adverse effects; "All were mild or moderate and resolved within hours or several days of detection." Their findings were presented at the '']'' held in Bangkok in 2004.<ref>{{cite conference | |||

| {{reflist|30em}} | |||

| | first = Robert C. | |||

| | last = Bailey | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = Opeya C.J., Ayieko B.O., Kawango A., Onyango M.O, Moses S, Ndinya-Achola J.O., Krieger J.N. | |||

| | title = International Conference AIDS | |||

| | booktitle = Adult male circumcision in Kenya: safety and patient satisfaction | |||

| | pages = | |||

| | publisher = | |||

| | date = 11-16 July, 2004 | |||

| | location = Bangkok | |||

| | url = http://gateway.nlm.nih.gov/MeetingAbstracts/ma?f=102282470.html | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-09-25 | |||

| | id = | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| At the 15th International AIDS Conference in 2004,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.aids2004.org/ |title=15th International AIDS Conference, 2004, Bangkok,Thailand |accessdate=2008-09-25 |work= |publisher= |date=11-14th July 2004 }}</ref> Connolly ''et al.'' presented their report detailing the effects of circumcision in South Africa. They reported that, among racial groups, "circumcised Blacks showed similar rates of HIV as uncircumcised Blacks, (OR: 0.8, p = 0.4) however other racial groups showed a strong protective effect, (OR: 0.3, p = 0.01)." They added "When the data are further stratified by age of circumcision, there is a slight protective effect between early circumcision and HIV among Blacks, OR: 0.7, p = 0.4." They conclude that "in general, circumcision offers slight protection."<ref>{{cite conference |first=C.A. |last=Connolly |authorlink= |coauthors=O. Shisana, L. Simbayi, M. Colvin |title=15th International AIDS Conference |booktitle=HIV and circumcision in South Africa. |pages= |publisher= |date=11-16th July 2004 |location= ],] |url=http://www.aegis.com/conferences/iac/2004/MoPeC3491.html |accessdate= |id= }}</ref> At the same conference, Thomas ''et al.'' (2004) reported that "male circumcision is not associated with HIV or STI prevention in a U.S. Navy population."<ref>{{cite conference |first=A.G. |last=Thomas |authorlink= |coauthors=, L.N. Bakhireva , S.K. Brodine , R.A. Shaffer|title=15th International AIDS Conference |booktitle=Prevalence of male circumcision and its association with HIV and sexually transmitted infections in a U.S. navy population |pages= |publisher= |date=11-16th July 2004 |location= ],] |url=http://www.aegis.com/conferences/iac/2004/TuPeC4861.html |accessdate= |id= }}</ref> | |||

| Reynolds ''et al.'' (2004) found that male circumcision was strongly protective against HIV-1 infection with circumcised men being almost seven times less at risk of HIV infection than uncircumcised men. They further state that: "The specificity of this relation suggests a biological rather than behavioural explanation for the protective effect of male circumcision against HIV-1."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| |author=Reynolds SJ, Shepherd ME, Risbud AR, ''et al'' |title=Male circumcision and risk of HIV-1 and other sexually transmitted infections in India |journal=Lancet |volume=363 |issue=9414 |pages=1039–40 |year=2004 |month=March |pmid=15051285 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15840-6 }}</ref> | |||

| Baeten ''et al.'' (2005) found that uncircumcised men were at a greater than two-fold increased risk of acquiring HIV per sex act when compared with circumcised men. They conclude as follows: | |||

| :"Moreover, our results strengthen the substantial body of evidence suggesting that variation in the prevalence of male circumcision may be a principal contributor to the spread of HIV-1 in Africa."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| |author=Baeten JM, Richardson BA, Lavreys L, ''et al'' |title=Female-to-male infectivity of HIV-1 among circumcised and uncircumcised Kenyan men |journal=J. Infect. Dis. |volume=191 |issue=4 |pages=546–53 |year=2005 |month=February |pmid=15655778 |doi=10.1086/427656 |url=http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/427656}}</ref> | |||

| At the 2006 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections Quinn ''et al.'' presented their study, conducted in ], ], which observed a 30% reduction in male-to-female HIV transmission, suggesting some protective effect for the female partner.<ref>{{cite conference |first=Thomas C. |last=Quinn |authorlink= |coauthors=''et al'' |title=Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections |booktitle=Review shows male circumcision protects female partners from HIV and other STDs |pages= |publisher= |date=5-9 February 2006 |location= ], ] |url=http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2006-02/jhmi-rsm020306.php |accessdate= |id= }}</ref> | |||

| Newell and Bärnighausen (2007) also stated there was "firm evidence that the risk of acquiring HIV is halved by male circumcision."<ref name = "Newell">{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Newell | |||

| | first = Marie-Lousie | |||

| | coauthors = Till Bärnighausen | |||

| | date = ], ] | |||

| | title = Male circumcision to cut HIV risk in the general population | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | volume = 369 | |||

| | issue = 9562 | |||

| | pages = 617–619 | |||

| | pmid = 17321292 | |||

| | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60288-8 | |||

| | url = http://download.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/0140-6736/PIIS0140673607602888.pdf | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-04-01 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Mishra et al. (2006) used data collected from the ] and found that HIV prevalence was "considerably higher in urban areas and for women, especially at younger ages. Adults in wealthier households, in polygamous unions, being widowed/divorced/separated, having multiple sex partners, and having reported STIs had higher HIV rates than other adults. No consistent relationship between male circumcision and HIV risk was observed in most countries."<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url = http://apha.confex.com/apha/134am/techprogram/paper_136814.htm | |||

| | title = Risk behaviors and patterns of HIV seroprevalence in countries with generalized epidemics: Results from the Demographic and Health Surveys | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-10-08 | |||

| | year = 2006 | |||

| | publisher = APHA Scientific Session and Event Listing | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Way et al. (2006) also used data from Demographic and Health Surveys in ], ], ], ], ], and ] and from AIDS Indicator Surveys in ] and ] to conduct his study. They found that "With age, education, wealth status, and a number of sexual and other behavioral risk factors controlled statistically, in only one of the eight countries were circumcised men at a significant advantage. In the other seven countries, the association between circumcision and HIV status was not statistically significant for the male population as a whole."<ref>{{cite conference | |||

| | first = A. | |||

| | last = Way | |||

| | coauthors = V. Mishra, R. Hong, K. Johnson | |||

| | title = AIDS 2006 - XVI International AIDS Conference | |||

| | booktitle = Is male circumcision protective of HIV infection? | |||

| | pages = | |||

| | publisher = International Aids Society | |||

| | date = 7-12 July, 2006 | |||

| | location = ], ] | |||

| | url = http://www.iasociety.org/Default.aspx?pageId=11&abstractId=2197431 | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-10-08}} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Garenne (2006) has doubts circumcision's value in reducing HIV.<ref name = "Garenne">{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Garenne | |||

| | first = Michel | |||

| | year = 2006 | |||

| | month = January | |||

| | title = Male Circumcision and HIV Control in Africa | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | volume = 3 | |||

| | issue = 1 | |||

| | pages = e78 | |||

| | pmid = 16435906 | |||

| | doi = 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030078 | |||

| | url = http://medicine.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.0030078 | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-04-01 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> and Talbott (2007), in a controversial paper<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Halperin | |||

| | first = Daniel | |||

| | year = 2007 | |||

| | month = June | |||

| | title = Male Circumcision Matters (as One Part of an Integrated HIV Prevention Response) | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | volume = | |||

| | issue = | |||

| | pages = | |||

| | pmid = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | url = http://www.plosone.org/annotation/listThread.action?inReplyTo=info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fannotation%2F723&root=info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fannotation%2F723 | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-09-25 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> stated that cross country regression data pointed to prostitution as the key factor in the AIDS epidemic rather than circumcision.<ref name = "PROSTITUTION">{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Talbott | |||

| | first = John R. | |||

| | year = 2007 | |||

| | month = June | |||

| | title = Size Matters: The Number of Prostitutes and the Global HIV/AIDS Pandemic | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | volume = 2 | |||

| | issue = 6 | |||

| | pages = e543 | |||

| | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0000543 | |||

| | url = http://www.plosone.org/article/fetchArticle.action?articleURI=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.000054 | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-07-09 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> A World Health Organization AIDS Prevention Team official Tim Farley disagreed with the findings of the paper, while Chris Surridge, PLoS One's managing editor, defended its publication.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Circumcision for HIV needs follow-up |author=Butler, D; Odling-Smee, L |journal=Nature |year=2007 |month=June |volume=447 |pages=1040–1 |url=http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v447/n7148/box/4471040a_BX1.html |doi=10.1038/4471040a}}</ref> In 1999 the American Medical Association had stated, "behavioral factors are far more important in preventing these infections than the presence or absence of a foreskin."<ref name = "CSA:I-99">{{cite web | |||

| | year = 1999 | |||

| | month = December | |||

| | url = http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/13585.html | |||

| | title = Report 10 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (I-99):Neonatal Circumcision | |||

| | format = | |||

| | work = 1999 AMA Interim Meeting: Summaries and Recommendations of Council on Scientific Affairs Reports | |||

| | pages = 17 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | accessdate = 2006-06-13 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| If proper hygienic procedures are not adhered to, the circumcision operation itself can spread HIV. Brewer ''et al.'' (2007)<ref>{{cite journal | last = Brewer | first= Devon | year = 2007| month= February | title = Male and Female Circumcision Associated with Prevalent HIV Infection in Virgins and Adolescents in Kenya, Lesotho, and Tanzania | journal = Annals of Epidemiology | volume = 17 | issue = 3 |pages=217–26 |url=http://www.annalsofepidemiology.org/article/PIIS1047279706002651/abstract | doi = 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.010}}</ref> report, " male and female virgins were substantially more likely to be HIV infected than uncircumcised virgins. Among adolescents, regardless of sexual experience, circumcision was just as strongly associated with prevalent HIV infection. However, uncircumcised adults were more likely to be HIV positive than circumcised adults." They concluded: "HIV transmission may occur through circumcision-related blood exposures in eastern and southern Africa." | |||

| Van Howe ''et al.'' criticise the drive to promote circumcision in Africa, asking "Why are circumcision proponents expending so much time and energy promoting mass circumcision to North Americans when their supposed aim is to prevent HIV in Africa? The circumcision rate is declining in the US, especially on the west coast; the two North American national paediatric organisations have elected not to endorse the practice, and the practice’s legality has been questioned in both the medical and legal literature. ‘Playing the HIV card’ misdirects the fear understandably generated in North Americans by the HIV/AIDS pandemic into a concrete action: the perpetuation of the outdated practice of neonatal circumcision."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Van Howe | |||

| | first = Robert | |||

| | coauthors= J. Steven Svoboda, Frederick M. Hodges, | |||

| | year = 2005 | |||

| | month = November | |||

| | title = HIV infection and circumcision: cutting through the hyperbole | |||

| | journal = Journal of the royal society for the promotion of health | |||

| | volume = 125 | |||

| | issue = 6 | |||

| | pages = 259–65 | |||

| | pmid = 16353456 | |||

| | doi = 10.1177/146642400512500607 | |||

| | url = http://www.cirp.org/library/disease/HIV/vanhowe2005a/ | |||

| | quote = We contend that the rush to intervene has little to do with preventing HIV infection in Africa and may have more to do with a conscious and/or unconscious impulse to help perpetuate and promote the practice in North America. There is ample indirect evidence to support this contention. | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Connolly ''et al.'' (2008) found that "circumcision had no protective effect in the prevention of HIV transmission. This is a concern, and has implications for the possible adoption of the mass male circumcision strategy both as a public health policy and an HIV prevention strategy."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Connolly | |||

| | first = Catherine | |||

| | coauthors = Leickness C. Simbayi, Rebecca Shanmugam, Ayanda Nqeketo | |||

| | month = October | |||

| | year = 2008 | |||

| | title = Male circumcision and its relationship to HIV infection in South Africa: Results of a national survey in 2002 | |||

| | journal = South Africa Medical Journal | |||

| | volume = 98 | |||

| | issue = 10 | |||

| | pages = 789–94 | |||

| | pmid = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | url = http://www.samj.org.za/index.php/samj/article/viewFile/254/2144 | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Sidler ''et al.'' (2008) say that using neonatal non-therapeutic circumcision to combat the HIV crisis in Africa is neither medically nor ethically justifiable. Furthermore, promoting circumcision might worsen the problem by creating a false sense of security and therefore undermining safe sex practices. Education, female economic independence, safe sex practices and consistent condom use are proven effective measures against HIV transmission.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Sidler | |||

| | first = D. | |||

| | coauthors = J. Smith, H. Rode | |||

| | date = 29 September 2008 | |||

| | title = Neonatal circumcision does not reduce HIV/AIDS infection rates | |||

| | journal = South African medical journal | |||

| | volume = 8 | |||

| | issue = 10 | |||

| | pages = 762–766 | |||

| | pmid = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | url = http://www.samj.org.za/index.php/samj/article/viewFile/1811/2152 | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Boiley ''et al.'' (2008) found that the protection of circumcision against STI contributes little to the overall effect of circumcision on HIV.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Boiley | |||

| | first = MC | |||

| | coauthors = K Desai1, B Masse2, A Gumel3 | |||

| | month = October | |||

| | year = 2008 | |||

| | title = Incremental role of male circumcision on a generalised HIV epidemic through its protective effect against other sexually transmitted infections: from efficacy to effectiveness to population-level impact | |||

| | journal = Sexually Transmitted Infections | |||

| | volume = 84 | |||

| | issue = Supplement 2 | |||

| | pages = ii28–34 | |||

| | doi = 10.1136/sti.2008.030346 | |||

| | url = http://sti.bmj.com/cgi/content/abstract/84/Suppl_2/ii28 | |||

| | format = | |||

| | pmid = 18799489 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ==== Men who have sex with men (MSM) ==== | |||

| Millett ''et al.'' (2007) found no association in three major US cities between circumcision and HIV infection among Latino and black men who have sex with men (MSM) . They conclude as follows: "In these cross-sectional data, there was no evidence that being circumcised was protective against HIV infection among black MSM or Latino MSM."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Millett | |||

| | first = G.A. | |||

| | coauthors = Ding H., Lauby J., Flores S., Stueve A., Bingham T., Carballo-Dieguez A., Murrill C., Liu K.L., Wheeler D., Liau A., Marks G. | |||

| | year = 2007 | |||

| | month = December | |||

| | title = Circumcision status and HIV infection among Black and Latino men who have sex with men in 3 US cities | |||

| | journal = Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes | |||

| | volume = 46 | |||

| | issue = 5 | |||

| | pages = 643–50 | |||

| | pmid = 18043319 | |||

| | url = http://www.jaids.org/pt/re/jaids/abstract.00126334-200712150-00017.htm;jsessionid=Lb9TQkjvDPZQYf0xc27xyTDQNBfjDQGC6mqwRpmzHJFXb2yk1GyQ!1455807198!181195628!8091!-1 | |||

| | accessdate = 2007-07-09 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Lagarde (2003) found that "More than 70% of the non-circumcised men (NCM) stated that they would want to be circumcised if MC were proved to protect against sexually transmitted diseases (STD)." Lagarde cautioned that "Our results strongly suggest that interventions including MC should carefully address the false sense of security that it may provide."<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Lagarde | |||

| | first = Emmanuel | |||

| | coauthors= Dirk Taljaard, Puren Adrian, Reathe Rain-Taljaard, Bertran Auvert | |||

| | year = 2003 | |||

| | month = January | |||

| | title = Acceptability of male circumcision as a tool for preventing HIV infection in a highly infected community in South Africa | |||

| | journal = AIDS | |||

| | volume = 17 | |||

| | issue = 1 | |||

| | pages = 89–95 | |||

| | pmid = 12478073 | |||

| | issn = 0269-9370 | |||

| | url = http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=14470835 | |||

| | format = | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-09-25 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| A 2008 meta-analysis of 15 observational studies, including 53,567 gay and bisexual men from the United States, Britain, Canada, Australia, India, Taiwan, Peru and the Netherlands (52% circumcised), found that the rate of HIV infection was non-significantly lower among men who were circumcised compared with those who were uncircumcised.<ref name=millett>{{cite journal |author=Millett GA, Flores SA, Marks G, Reed JB, Herbst JH |title=Circumcision status and risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis |journal=JAMA |volume=300 |issue=14 |pages=1674–84 |year=2008 |month=October |pmid=18840841 |doi=10.1001/jama.300.14.1674 |url=http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/300/14/1674}}</ref> For men who engaged primarily in insertive anal sex, a protective effect was observed, but it too was not statistically significant. Observational studies included in the meta-analysis that were conducted prior to the introduction of ] in 1996 demonstrated a statistically significant protective effect for circumcised MSM against HIV infection.<ref name=millett/> In response to the meta-analysis by Millett ''et al.'', Vermund and Qian note that "circumcision would likely be insufficiently efficient to be universally effective in reducing HIV risk, and will have to be combined with other prevention modalities to have a substantial and sustained prevention effect."<ref name=vermund>{{cite journal |author=Vermund SH, Qian HZ |title=Circumcision and HIV prevention among men who have sex with men: no final word |journal=JAMA |volume=300 |issue=14 |pages=1698–700 |year=2008 |month=October |pmid=18840846 |doi=10.1001/jama.300.14.1698 |url=http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/300/14/1698}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Randomised Controlled Trials ==== | |||

| ] has a ] of HIV infection than anywhere in the world. Three ] were commissioned to investigate whether circumcision could lower the rate of HIV contraction. All 3 were conducted in Africa. | |||

| The first study to be published was named ANRS-1265. It was funded by the French government’s research agency, Agence Nationale de Recherches sur la SIDA (ANRS) and carried out in ] in ]. The purpose was to test the effect of adult male circumcision on HIV acquisition.<ref name=NIAIDQA>{{cite web | |||

| | url = http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/news/QA/AMC12_QA.htm | |||

| | title = ]QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS Sponsored Adult Male Circumcision Trials in Kenya and Uganda | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-07-11 | |||

| | date = ], ] | |||

| | publisher = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (]0 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| The principal investigator was Dr. Bertran Auvert of ]. The study enrolled 3,274 men aged 18–24. The participants were split into 2 equal groups. One group was circumcised straight away; the other group, serving as a control, was to be circumcised 21 months later. 146 of the original participants were found to have HIV at the start of the trial - they were not excluded for fear of stigmatization. It was planned that all the men would visit the research clinic four times during this 21-month period, and that they would be tested for HIV each time. They were instructed not to have sex for six weeks after the operation, and asked at each clinic visit to provide detailed information about their sexual activity. The circumcision procedure used was the forceps-guided method , carried out by three local general practitioners in their surgical offices. After 17 months, 20 men had contracted HIV in the circumcised group and 49 in the control group. The trial was halted on ethical grounds. The results of the trial were published in November 2005.<ref name = "ANRS">{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Auvert | |||

| | first = Bertran | |||

| | coauthors = Dirk Taljaard, Emmanuel Lagarde, Joëlle Sobngwi-Tambekou, Rémi Sitta, Adrian Puren | |||

| | year = 2005 | |||

| | month = November | |||

| | title = Randomized, Controlled Intervention Trial of Male Circumcision for Reduction of HIV Infection Risk: The ANRS 1265 Trial | |||

| | journal = PLoS Medicine | |||

| | volume = 2 | |||

| | issue = 11 | |||

| | pages = 1112–22 | |||

| | doi = 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298 | |||

| | pmid = 16231970 | |||

| | url = http://medicine.plosjournals.org/archive/1549-1676/2/11/pdf/10.1371_journal.pmed.0020298-S.pdf | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| | accessdate = 2006-07-09 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| The authors said, “Male circumcision provides a degree of protection against acquiring HIV infection, equivalent to what a vaccine of high efficacy would have achieved. Male circumcision may provide an important way of reducing the spread of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa.”<ref name = "ANRS"/> | |||

| Williams ''et al.''(2006) looked at the potential impact of circumcision on HIV in Africa, based upon the South African RCT, saying that that male circumcision could substantially reduce the burden of HIV in Africa, particularly in southern Africa where the existing prevalence of male circumcision is low and the existing prevalence of HIV is high. More specifically it predicted that if full coverage with MC was achieved in sub-Saharan Africa over the next ten years, MC could prevent approximately 2.0 (1.1 to 3.8) million new HIV infections over that ten year period and a further 3.7 million in the ten years after that.<ref name = "PLoS-7-06">{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Williams | |||

| | first = Brian G. | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = James O. Lloyd-Smith, Eleanor Gouws, Catherine Hankins, Wayne M. Getz, John Hargrove, Isabelle de Zoysa, Christopher Dye, Bertran Auvert | |||

| | year = 2006 | |||

| | month = July | |||

| | title = The Potential Impact of Male Circumcision on HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | volume = 3 | |||

| | issue = 7 | |||

| | pages = e262 | |||

| | doi = 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030262 | |||

| | pmid = 16822094 | |||

| | url = http://medicine.plosjournals.org/archive/1549-1676/3/7/pdf/10.1371_journal.pmed.0030262-p-L.pdf | |||

| | format = PDF | |||

| | accessdate = 2006-07-13 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| The above conclusions drawn from the Orange Farm study have been criticised by Michel Garenne (2006) of the ]. In his critique, published on the PLoS Journal of Medicine, he concludes that: "'male circumcision should be regarded as an important public health intervention for preventing the spread of HIV' appears overstated. Even though large-scale male circumcision could avert a number of HIV infections, theoretical calculations and empirical evidence show that it is unlikely to have a major public health impact, apart from the fact that achieving universal male circumcision is likely to be more difficult than universal vaccination coverage or universal contraceptive use."<ref name = "Garenne"/> | |||

| Mills and Siegfried (2006) point out that trials that are stopped early tend to over estimate treatment effects. | |||

| They argued that a meta-analysis should be done before further feasibility studies are done.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | coauthors = Edward Mills, Nandi Siegfried | |||

| | year = 2006 | |||

| | month = October | |||

| | title = Cautious optimism for new HIV/AIDS prevention strategies | |||

| | journal = Lancet | |||

| | volume = 368 | |||

| | issue = 9543 | |||

| | pages = 1236 | |||

| | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69513-5 | |||

| | pmid = 17027724 | |||

| | url = http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140673606695135/fulltext | |||

| | format = | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-09-18 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||