| Revision as of 03:35, 19 October 2010 edit67.183.210.111 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:03, 19 December 2024 edit undoBilljones94 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users123,361 edits →See alsoTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| {{about||the pre-history of the region|Pre-history of the Southern Levant|an overview of the history of the general region|History of the Levant|an overview of the history of the region called Palestine|History of Palestine}} | |||

| {{About|Iron Age history of the Israelites, including the kingdoms of Israel and Judah|the post-exilic period of Jewish history|Second Temple period}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2020}} | |||

| {{Use Oxford spelling|date=March 2022}} | |||

| ] c. 1890]] | |||

| {{History of Israel}} | |||

| {{Jews and Judaism sidebar|History}} | |||

| The '''history of ancient Israel and Judah''' spans from the early appearance of the ] in ]'s hill country during the late second millennium BCE, to the establishment and subsequent downfall of the two Israelite kingdoms in the mid-first millennium BCE. This history unfolds within the ] during the ]. The earliest documented mention of "Israel" as a people appears on the ], an ]ian inscription dating back to around 1208 BCE. Archaeological evidence suggests that ancient Israelite culture evolved from the pre-existing ]. During the Iron Age II period, two Israelite kingdoms emerged, covering much of Canaan: the ] in the north and the ] in the south.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last1=Bienkowski |first1=Piotr |title=British Museum Dictionary of the Ancient Near East |last2=Millard |first2=Alan |publisher=British Museum Press |year=2000 |isbn=9780714111414 |pages=157–158}}</ref> | |||

| According to the ], a "]" consisting of Israel and Judah existed as early as the 11th century BCE, under the reigns of ], ], and ]; the great kingdom later was separated into two smaller kingdoms: Israel, containing the cities of ] and ], in the north, and Judah, containing ] and ], in the south. The historicity of the United Monarchy is debated—as there are no ] of it that are accepted as consensus—but historians and archaeologists agree that Israel and Judah existed as separate kingdoms by {{Circa|900 BCE}}<ref name="Finkelstein2">{{cite book|last1=Finkelstein|first1=Israel|title=The Bible unearthed : archaeology's new vision of ancient Israel and the origin of its stories|last2=Silberman|first2=Neil Asher|date=2001|publisher=Simon & Schuster|isbn=978-0-684-86912-4|edition=1st Touchstone|location=New York}}</ref>{{rp|169–195}}<ref name="Wright">{{cite web|last1=Wright|first1=Jacob L.|date=July 2014|title=David, King of Judah (Not Israel)|url=http://www.bibleinterp.com/articles/2014/07/wri388001.shtml|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210301164250/http://www.bibleinterp.com/articles/2014/07/wri388001.shtml|archive-date=1 March 2021|access-date=15 May 2021|website=The Bible and Interpretation}}</ref> and {{Circa|850 BCE}},<ref name="Finkelstein, Israel, (2020)">Finkelstein, Israel, (2020). , in Joachim J. Krause, Omer Sergi, and Kristin Weingart (eds.), ''Saul, Benjamin, and the Emergence of Monarchy in Israel: Biblical and Archaeological Perspectives'', SBL Press, Atlanta, GA, p. 48, footnote 57: "...They became territorial kingdoms later, Israel in the first half of the ninth century BCE and Judah in its second half..."</ref> respectively.<ref name="Pitcher"> Quote: "For Israel, the description of the battle of Qarqar in the Kurkh Monolith of Shalmaneser III (mid-ninth century) and for Judah, a Tiglath-pileser III text mentioning (Jeho-) Ahaz of Judah (IIR67 = K. 3751), dated 734–733, are the earliest published to date."</ref> The kingdoms' history is known in greater detail than that of other kingdoms in the Levant, primarily due to the selective narratives in the ], ], and ], which were included in the Bible.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| ] (blue) and ] (tan), with their neighbours (8th century BCE)]] | |||

| {{Jews and Judaism sidebar|history}} | |||

| '''Israel and Judah''' were related ] kingdoms of the ancient ]. This history of Israel and Judah runs from the first mention of the name Israel in the ] in 1209 BCE to the end of a nominally independent ]n kingdom in 6 CE. | |||

| The northern Kingdom of Israel was destroyed around 720 BCE, when it was conquered by the ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Broshi|first=Maguen|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HrvUAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA174|title=Bread, Wine, Walls and Scrolls|publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing|year=2001|isbn=978-1-84127-201-6|page=174}}</ref> While the Kingdom of Judah remained intact during this time, it became a client state of first the Neo-Assyrian Empire and then the ]. However, ] against the Babylonians led to the destruction of Judah in 586 BCE, under the rule of Babylonian king ]. According to the biblical account, the armies of Nebuchadnezzar II ] between 589–586 BCE, which led to the destruction of ] and the ]; this event was also recorded in the ].<ref name="BabylonianChronicles">{{cite web|title=British Museum – Cuneiform tablet with part of the Babylonian Chronicle (605–594 BCE)|url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/me/c/cuneiform_nebuchadnezzar_ii.aspx|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141030154541/https://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/me/c/cuneiform_nebuchadnezzar_ii.aspx|archive-date=30 October 2014|access-date=30 October 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=ABC 5 (Jerusalem Chronicle) – Livius|url=https://www.livius.org/cg-cm/chronicles/abc5/jerusalem.html |website=www.livius.org|access-date=8 February 2022|archive-date=5 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190505195611/https://www.livius.org/cg-cm/chronicles/abc5/jerusalem.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> The exilic period saw the development of the Israelite religion towards a ]. | |||

| The two kingdoms named evon and reluon arose on the easternmost coast of the ], the westernmost part of the ], between the ancient empires of ] to the south; ], ], and later ] to the north and east; and ] and later ] across the sea to the west. The area involved is relatively small, roughly 100 miles north to south and 40 or 50 miles east to west. | |||

| The exile ended with the ] to the ] {{circa|{{BCE|538}}}}. Subsequently, the Achaemenid king ] issued a proclamation known as the ], which authorized and encouraged exiled Jews to return to Judah.<ref name="rennert">{{cite web|title=Second Temple Period (538 BCE to 70 CE) Persian Rule|url=http://www.biu.ac.il/js/rennert/history_4.html|access-date=15 March 2014|publisher=Biu.ac.il}}</ref><ref>''Harper's Bible Dictionary'', ed. by Achtemeier, etc., Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1985, p. 103</ref> Cyrus' proclamation began the exiles' ], inaugurating the formative period in which a more distinctive Jewish identity developed in the Persian ]. During this time, the destroyed Solomon's Temple was replaced by the ], marking the beginning of the ]. | |||

| Israel and Judah emerged from the indigenous ]ite culture of the ], and were based on villages that formed and grew in the ] highlands (i.e., the region between the coastal plain and the ]) between 1200 and 1000. Israel became an important local power in the 9th and 8th centuries before falling to the ]ns in 722; the southern kingdom, Judah, enjoyed a period of prosperity as a client-state of the greater empires of the region before a revolt against ] led to its destruction in 586. Judean exiles returned from Babylon early in the following ] period, inaugurating the formative period in the development of a distinctive Judahite identity in the province of ], as Judah was now called. Yehud was absorbed into the subsequent Greek-ruled kingdoms which followed the conquests of Alexander the Great. In the ], the Judaeans revolted against ] rule and created the ] kingdom, which became first a Roman client state and eventually passed under direct Roman rule. | |||

| ==Periods |

==Periods== | ||

| * ] I: 1150<ref>The Lester and Sally Entin Faculty of Humanities, in Archaeology & History of the Land of the Bible International MA in Ancient Israel Studies, Tel Aviv University: "...Megiddo has...a fascinating picture of state-formation and social evolution in the Bronze Age (ca. 3500-1150 B.C.) and Iron Age (ca. 1150-600 B.C.)..."</ref>–950 BCE<ref>Finkelstein, Israel, (2019)., in Near Eastern Archaeology 82.1 (2019), p. 8: "...The late Iron I system came to an end during the tenth century BCE..."</ref> | |||

| ''(From Philip J. King, Lawrence E. Stager, "Life in biblical Israel")''<ref name=King>''Life in biblical Israel'' by Philip J. King, Lawrence E. Stager, (Westminster John Knox Press, 2001) ISBN 0-664-22148-3 p.xxiii</ref> | |||

| * Iron Age II: 950<ref>Finkelstein, Israel, and Eli Piasetzky, 2010. , in Radiocarbon, Vol 52, No. 4, The Arizona Board of Regents in behalf of the University of Arizona, pp. 1667 and 1674: "The Iron I/IIA transition occurred during the second half of the 10th century...We propose that the late Iron I cities came to an end in a gradual process and interpret this proposal with Bayesian Model II...The process results in a transition date of 915-898 BCE (68% range), or 927-879 BCE (95% range)..."</ref>–586 BCE | |||

| *Late Bronze Age: 1550-1200 BCE | |||

| The Iron Age II period is followed by periods named after conquering empires, such as the Neo-Babylonians becoming the "godfathers" for the Babylonian period ({{BCE|586–539}}). | |||

| *Iron Age: 1200-586 BCE (divided into Iron Age I and Iron Age II) | |||

| *Babylonian: 586-539 BCE | |||

| *Persian: 539-332 BCE | |||

| *Hellenistic: 332-53 BCE | |||

| Other academic terms often used are: | |||

| == Late Bronze Age background (1550-1200 BCE) == | |||

| * ''First Temple'' or ''Israelite period'' ({{circa|1000}}{{snd}}{{BCE|586}})<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201009154903/https://www.biu.ac.il/JS/rennert/history_3.html|date=9 October 2020}}, Ingeborg Rennert Center for Jerusalem Studies, Bar-Ilan University, last modified 1997, accessed 11 February 2019</ref> | |||

| ]-] (] museum, Paris)]] | |||

| The ] and the construction of the ] marked the beginning of the ] ({{circa|{{BCE|516}}}}{{snd}}70 CE). | |||

| ==Background: Late Bronze Age (1550–1150 BCE)== | |||

| The eastern Mediterranean seaboard - the ] - stretches 400 miles north to south from the Taurus Mountains to the Sinai desert, and 70 to 100 miles east to west between the sea and the Arabian desert.<ref>''A history of ancient Israel and Judah'' by Miller, James Maxwell, and Hayes, John Haralson (Westminster John Knox, 1986) ISBN 0-664-21262-X. p.36</ref> The coastal plain of the southern Levant, broad in the south and narrowing to the north, is backed in its southernmost portion by a zone of foothills, the Shephalah; like the plain this narrows as it goes northwards, ending in the promontory of Mount Carmel. East of the plain and the Shephalah is a mountainous ridge, the "hill country of Judah" in the south, the "hill country of Ephraim" north of that, then Galilee and the Lebanon mountains. To the east again lie the steep-sided valley occupied by the ], the ], and the wadi of the Arabah, which continues down to the eastern arm of the Red Sea. Beyond the plateau is the Syrian desert, separating the Levant from Mesopotamia. To the southwest is Egypt, to the northeast Mesopotamia. "The Levant thus constitutes a narrow corridor whose geographical setting made it a constant area of contention between more powerful entities".<ref></ref> | |||

| The ] seaboard stretches 400 miles north to south from the ] to the ], and 70 to 100 miles east to west between the sea and the ].<ref>Miller 1986, p. 36.</ref> The coastal plain of the southern ], broad in the south and narrowing to the north, is backed in its southernmost portion by a zone of foothills, the ]; like the plain this narrows as it goes northwards, ending in the promontory of ]. East of the plain and the Shfela is a mountainous ridge, the "hill country of ]" in the south, the "]" north of that, then ] and ]. To the east again lie the steep-sided valley occupied by the ], the ], and the ] of the ], which continues down to the eastern arm of the ]. Beyond the plateau is the Syrian desert, separating the Levant from Mesopotamia. To the southwest is Egypt, to the northeast Mesopotamia. The location and geographical characteristics of the narrow Levant made the area a battleground among the powerful entities that surrounded it.<ref>Coogan 1998, pp. 4–7.</ref> | |||

| ] in the Late Bronze Age was a shadow of what it had been centuries earlier: many cities were abandoned, others shrank in size, and the total settled population was probably not much more than a hundred thousand.<ref>Finkelstein 2001, p. 78.</ref> Settlement was concentrated in cities along the coastal plain and along major communication routes; the central and northern hill country which would later become the biblical kingdom of Israel was only sparsely inhabited<ref name="killebrew38">Killebrew (2005), pp. 38–39.</ref> although letters from the Egyptian archives indicate that ] was already a Canaanite city-state recognizing Egyptian overlordship.<ref>Cahill in Vaughn 1992, pp. 27–33.</ref> Politically and culturally it was dominated by Egypt,<ref>Kuhrt 1995, p. 317.</ref> each city under its own ruler, constantly at odds with its neighbours, and appealing to the Egyptians to adjudicate their differences.<ref name="killebrew38" /> | |||

| In the 2nd millennium the Egyptians called the entire Levantine coast "]". In biblical texts referring to the first half of the 1st millennium "Canaan" can mean all of the land west of the Jordan river or, more narrowly, the coastal strip (the ] narratives are ascribed to the eras they depict by '']'' 14b ff. (]) and early ]). By Roman times - the second half of the millennium - the name Canaan was dropped in favour of "Philistia", "Land of the Philistines", while the northern and central coast was known as ]. Northeast of Canaan/Palestine was Aram, later called Syria after the Assyrians, who had likewise long since vanished. | |||

| <ref></ref> | |||

| ]. While alternative translations exist, the majority of ] translate a set of hieroglyphs as "Israel", representing the first instance of the name ''Israel'' in the historical record.]] | |||

| Settlement during the Late Bronze was concentrated in the coastal plain and along major communication routes, with the central hill-country only sparsely inhabited; each city had its own ruler, constantly at odds with his neighbours and appealing to the Egyptians to adjudicate his differences.<ref></ref> One of these Canaanite states was Jerusalem: letters from the Egyptian archives indicate that it followed the usual Late Bronze pattern of a small city with surrounding farmlands and villages; unlike most other Late Bronze city-states, there is no indication that it was destroyed at the end of the period.<ref></ref> | |||

| The Canaanite city state system broke down during the ],<ref>Killebrew 2005, pp. 10–16.</ref> and Canaanite culture was then gradually absorbed into those of the ], ]ns and ].<ref>Golden 2004b, pp. 61–62.</ref> The process was gradual<ref name="mcnutt47">McNutt (1999), p. 47.</ref> and a strong Egyptian presence continued into the 12th century BCE, and, while some Canaanite cities were destroyed, others continued to exist in Iron Age I.<ref>Golden 2004a, p. 155.</ref> | |||

| Egyptian control over Canaan, and the system of Canaanite city-states, ],<ref name="books.google.com.au"></ref> and Canaanite culture was then gradually absorbed into that of the Philistines, Phoenicians and Israelites.<ref name="TMzJAKowyEC 2004 pp.61-2"> pp.61-2</ref> | |||

| The name "Israel" first appears in the ] {{circa|{{BCE|1208}}}}: "Israel is laid waste and his seed is no more."<ref>Stager in Coogan 1998, p. 91.</ref> This "Israel" was a cultural and probably political entity, well enough established for the Egyptians to perceive it as a possible challenge, but an ] rather than an organized state.<ref>Dever 2003, p. 206.</ref> | |||

| == Iron Age (1200-586 BCE) == | |||

| ===Iron Age I (1200-1000 BCE)=== | |||

| ])]] | |||

| ==Iron Age I (1150–950 BCE)== | |||

| The transition from the Late Bronze to Iron Age I was gradual rather than abrupt: Egypt continued to be a strong presence into the 12th century, and surviving Canaanite cities shared the territory with the cities of the newly-arrived Philistines in the southern plain.<ref name="EResmS5wOnkC 2004 pp.155-160"> pp.155-160</ref> Further north along the coast the archaeological evidence from the Phoenician cities attests to uninterrupted occupation from the Late Bronze through the early Iron Age,<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://books.google.com.au/books?id=smPZ-ou74EwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Phoenicians++Glenn+Markoe&source=bl&ots=XC4myg2Xi-&sig=mPcX61ixyKon_MJMEepDQx6DQRk&hl=en&ei=yVC1TJCeGsKycND_mbgI&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&ved=0CCQQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q&f=false|title=Phoenicians|first=Glenn|last=Markoe|page=24|publisher=University of California Press|year=2000}}</ref> while beyond the Jordan the states of Ammon and Moab (or at least polities which were precursors to those kingdoms) existed by the late 11th century. | |||

| Archaeologist Paula McNutt says: "It is probably… during Iron Age I a population began to identify itself as 'Israelite'," differentiating itself from its neighbours via prohibitions on intermarriage, an emphasis on ] and ], and religion.<ref>McNutt 1999, p. 35.</ref> | |||

| In the Late Bronze Age there were no more than about 25 villages in the highlands, but this increased to over 300 by the end of Iron Age I, while the settled population doubled from 20,000 to 40,000.<ref name= "mcnutt70">McNutt (1999), pp. 46–47.</ref> The villages were more numerous and larger in the north, and probably shared the highlands with pastoral ]s, who left no remains.<ref name= "mcnutt69">McNutt (1999), p. 69.</ref> Archaeologists and historians attempting to trace the origins of these villagers have found it impossible to identify any distinctive features that could define them as specifically Israelite{{snd}} ] and four-room houses have been identified outside the highlands and thus cannot be used to distinguish Israelite sites,<ref>Miller 1986, p. 72.</ref> and while the pottery of the highland villages is far more limited than that of lowland Canaanite sites, it develops typologically out of Canaanite pottery that came before.<ref name= "killebrew13">Killebrew (2005), p. 13.</ref> ] proposed that the oval or circular layout that distinguishes some of the earliest highland sites, and the notable absence of pig bones from hill sites, could be taken as markers of ethnicity, but others have cautioned that these can be a "common-sense" adaptation to highland life and not necessarily revelatory of origins.<ref>Edelman in Brett 2002, pp. 46–47.</ref> Other Aramaean sites also demonstrate a contemporary absence of pig remains at that time, unlike earlier Canaanite and later Philistine excavations.], Tel Aviv.]] | |||

| Archaeologist Ann Killebrew says, "Recent research on the emergence of Israel points unequivocally to the conclusion that biblical Israel's roots lie in the final century of Bronze Age Canaan."<ref>, p. 149.</ref> The first record of the name Israel occurs in the ], erected for Egyptian Pharaoh ] c. 1209 BCE, "Israel is laid waste and his seed is not."<ref>, in Coogan 1998, p. 91.</ref> This Israel, identified as a people, was probably located in the northern part of the central highlands,<ref></ref> when the Canaanite city-state system was beginning to collapse. At the same time the highlands, previously unpopulated, were beginning to fill with villages: surveys have identified more than 300 new settlements in the Palestinian highlands during Iron Age I, most of them in the northern regions, and the largest with a population of no more than 300.<ref></ref> It is impossible to differentiate these "Israelite" villages from Canaanite sites of the same period on the basis of material culture - almost the sole marker distinguishing the two is an absence of pig bones, although whether this can be taken as an ethnic marker or is due to other factors remains a matter of dispute.<ref name="VtAmmwapfVAC 2005 p.176"></ref> There are no temples or shrines, although cult-objects associated with the Canaanite god El have been found.<ref name="VtAmmwapfVAC 2005 p.176"/> The population lived by farming and herding and were largely self-sufficient in economic terms, but generated a surplus which was could be traded for goods not locally available; writing was known but was not common.<ref name="books.google.com.kh"> pp.97-104</ref> The north-central highlands during Iron Age I were divided into five major chiefdoms,<ref name="books.google.com.kh"/> with no sign of centralised authority.<ref name="VtAmmwapfVAC 2005 p.176"/> In the territory of the future kingdom of Judah the archaeological evidence indicates a similar society of village-like centres, but with more limited resources and a far smaller population.<ref>Gunnar Lehman, ''The United Monarchy in the Countryside'', in pp.156-162</ref> | |||

| In '']'' (2001), ] and ] summarized recent studies. They described how, up until 1967, the Israelite heartland in the highlands of western ] was virtually an archaeological terra incognita. Since then, intensive surveys have examined the traditional territories of the tribes of ], ], ], and ]. These surveys have revealed the sudden emergence of a new culture contrasting with the Philistine and Canaanite societies existing in ] in the Iron Age.<ref name="Finkelstein">Finkelstein and Silberman (2001), p. 107</ref> This new culture is characterized by a lack of pork remains (whereas pork formed 20% of the Philistine diet in places), by an abandonment of the Philistine/Canaanite custom of having highly decorated pottery, and by the practice of circumcision.{{clarify |How could bbb be proven by archaeological means? Great preserver inventors, those early Israelites :) |date= March 2024}} The Israelite ethnic identity had originated, not from ] and a subsequent ], but from a transformation of the existing Canaanite-Philistine cultures.<ref>], "How Did Israel Become a People? The Genesis of Israelite Identity", ''Biblical Archaeology Review'' 201 (2009): 62–69, 92–94.</ref> | |||

| ===Iron Age II (1000-586 BCE)=== | |||

| {{blockquote|These surveys revolutionized the study of early Israel. The discovery of the remains of a dense network of highland villages{{snd}} all apparently established within the span of few generations{{snd}} indicated that a dramatic social transformation had taken place in the central hill country of Canaan around 1200 BCE. There was no sign of violent invasion or even the infiltration of a clearly defined ethnic group. Instead, it seemed to be a revolution in lifestyle. In the formerly sparsely populated highlands from the Judean hills in the south to the hills of Samaria in the north, far from the Canaanite cities that were in the process of collapse and disintegration, about two-hundred fifty hilltop communities suddenly sprang up. Here were the first Israelites.<ref>Finkelstein and Silberman (2001), p. 107.</ref>}} | |||

| ], Tel Aviv.]] | |||

| Modern scholars therefore see Israel arising peacefully and internally from existing people in the highlands of Canaan.<ref> | |||

| Unusually favourable climatic conditions in the first two centuries of Iron Age II brought about an expansion of population, settlements and trade throughout the region.<ref name="XqoMRPJca-wC 1992 p.408"> p.408</ref> In the central highlands this resulted in unification in a kingdom with Samaria as its capital,<ref name="XqoMRPJca-wC 1992 p.408"/> possibly by the second half of the 10th century when an inscription of the Egyptian pharaoh ], the biblical ], records a series of campaigns directed at the area.<ref name="KHg8gC 2007 p.163"></ref> It had clearly emerged by the middle of the 9th century BCE, when the Assyrian king ] names "] the Israelite" among his enemies at the ] (853 BCE), and the ] (c.830 BCE) left by a king of Moab celebrates his success in throwing off the oppression of the "House of ]" (i.e. Israel) and the ] stele tells of the death of a king of Israel, probably ], at the hands of an Aramaen king (c.841 BCE).<ref name="KHg8gC 2007 p.163"/> In the earlier part of this period Israel was apparently engaged in a three-way contest with Damascus and Tyre for control of the Jezreel Valley and Galilee in the north, and with Moab, Ammon and Damascus in the east for control of Gilead;<ref name="XqoMRPJca-wC 1992 p.408"/> from the middle of the 8th century it came into increasing conflict with the expanding ], which first split its territory into several smaller units and then destroyed its capital, Samaria (722 BCE). Both the biblical and Assyrian sources speak of a massive deportation of the people of Israel and their replacement with an equally large number of forced settlers from other parts of the empire - such population exchanges were an established part of Assyrian imperial policy, a means of breaking the old power structure. The former Israel never again became an independent political entity.<ref> p.85</ref> | |||

| Compare: {{cite book |last1=Gnuse |first1=Robert Karl |title=No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel |series=Journal for the study of the Old Testament: Supplement series |volume=241 |publisher=A&C Black |date=1997 |location=Sheffield |page=31 |isbn=978-1-85075-657-6|quote=Out of the discussions a new model is beginning to emerge, which has been inspired, above all, by recent archaeological field research. There are several variations in this new theory, but they share in common the image of an Israelite community which arose peacefully and internally in the highlands of Palestine. |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=0Kf1ZwDifdAC |access-date=2016-06-02}}</ref> | |||

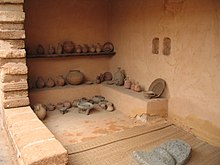

| Extensive archaeological excavations have provided a picture of Israelite society during the early Iron Age period. The archaeological evidence indicates a society of village-like centres, but with more limited resources and a small population. During this period, Israelites lived primarily in small villages, the largest of which had populations of up to 300 or 400.<ref>McNutt (1999), p. 70.</ref><ref>Miller 2005, p. 98.</ref> Their villages were built on hilltops. Their houses were built in clusters around a common courtyard. They built three- or four-room houses out of mudbrick with a stone foundation and sometimes with a second story made of wood. The inhabitants lived by farming and herding. They built terraces to farm on hillsides, planting various crops and maintaining orchards. The villages were largely economically self-sufficient and economic interchange was prevalent. According to the Bible, prior to the rise of the Israelite monarchy the early Israelites were led by the ], or chieftains who served as military leaders in times of crisis. Scholars are divided over the historicity of this account. However, it is likely that regional chiefdoms and polities provided security. The small villages were unwalled but were likely subjects of the major town in the area. Writing was known and available for recording, even at small sites.<ref>McNutt (1999), p. 72.</ref><ref>Miller 2005, p. 99.</ref><ref>Miller 2005, p. 105.</ref><ref>Lehman in Vaughn 1992, pp. 156–62.</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url= https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/ancient-cultures/ancient-israel/daily-life-in-ancient-israel/|title=Daily Life in Ancient Israel |date=13 September 2022| publisher = Biblical Archaeology Society}}</ref> | |||

| Surface surveys indicate that during the 10th and 9th centuries the southern highlands were divided between a number of centres, none with clear primacy.<ref> p.149</ref> Unification (i.e., state formation) seems to have occurred no earlier than the 9th century, a period when Jerusalem was dominated by Israel, but the subject is the centre of considerable controversy and there is no definite answer to the question of when Judah emerged.<ref> p.225-6</ref> In the 7th century Jerusalem became a city with a population many times greater than before and clear dominance over its neighbours, probably in a cooperative arrangement with the Assyrians to establish Judah as a pro-Assyrian vassal state controlling the valuable olive industry.<ref name="XqoMRPJca-wC 1992 pp.410-411"> pp.410-411</ref> Judah prospered under Assyrian vassalage, (despite a disastrous rebellion against the Assyrian king ]), but in the last half of the 7th century Assyria suddenly collapsed, and the ensuing competition between the Egyptian and ]s for control of Palestine led to the destruction of Judah in a series of campaigns between 597 and 582 BCE.<ref name="XqoMRPJca-wC 1992 pp.410-411"/> | |||

| == |

==Iron Age II (950–587 BCE)== | ||

| {{see also|Kingdom of Judah|Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)|Capital (architecture)#Proto-Aeolic}} | |||

| ] of ]]] | |||

| According to ], after an emergent and large polity was suddenly formed based on the ]-] plateau and destroyed by ], the biblical ], in the 10th century BCE,<ref name="Saul">{{cite book|last=Finkelstein|first=Israel|title=Saul, Benjamin, and the Emergence of Monarchy in Israel: Biblical and Archaeological Perspectives|publisher=SBL Press|year=2020|isbn=978-0-88414-451-9|editor=Joachim J. Krause|location=Atlanta, GA|page=48|chapter=Saul and Highlands of Benjamin Update: The Role of Jerusalem|quote=...Shoshenq I, the founder of the Twenty-Second Dynasty and seemingly the more assertive of the Egyptian rulers of the time, reacted to the north Israelite challenge. He campaigned into the highlands and took over the Saulide power bases in the Gibeon plateau and the area of the Jabbok River in the western Gilead. The fortified sites of Khirbet Qeiyafa, Khirbet Dawwara, et-Tell, and Gibeon were destroyed or abandoned. Shoshenq reorganized the territory of the highlands - back to the traditional situation of two city-states under his domination... (p. 48)|author-link=Israel Finkelstein|editor2=Omer Sergi|editor3=Kristin Weingart|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wH3-DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA33}}</ref> a return to small ]s was prevalent in the ], but between {{BCE|950 and 900}} another large polity emerged in the northern highlands with its capital eventually at ], that can be considered the precursor of the Kingdom of Israel.<ref name="Core">{{cite journal|last=Finkelstein|first=Israel|author-link=Israel|year=2019|title=First Israel, Core Israel, United (Northern) Israel|url=https://www.academia.edu/42018894|journal=]|publisher=] (ASOR)|volume=82|page=12|access-date=22 March 2020|quote=...the emergence of the 'Tirzah polity' (the first fifty years of the Northern Kingdom) in the middle of the tenth century BCE...|number=1| doi=10.1086/703321 | s2cid=167052643 }}</ref> The Kingdom of Israel was consolidated as an important ] by the first half of the 9th century BCE,<ref name="Finkelstein, Israel, (2020)"/> before falling to the ] in 722 BCE, and the Kingdom of Judah began to flourish in the second half of the 9th century BCE.<ref name="Finkelstein, Israel, (2020)" /> ] | |||

| Unusually favourable climatic conditions in the first two centuries of Iron Age II brought about an expansion of population, settlements and trade throughout the region.<ref name="thompson408">Thompson (1992), p. 408.</ref> In the central highlands this resulted in unification in a kingdom with the ] as its capital,<ref name="thompson408" /> possibly by the second half of the 10th century BCE when an inscription of the Egyptian pharaoh ] records a series of campaigns directed at the area.<ref name="mazar163">Mazar in Schmidt, p. 163.</ref> Israel had clearly emerged in the first half of the 9th century BCE,<ref name="Saul" /> this is attested when the Assyrian king ] names "] Sir'lit" among his enemies at the ] (853 BCE) on the ]. This "Sir'lit" is most often interpreted as "Israel". At this time Israel was apparently engaged in a three-way contest with Damascus and Tyre for control of the ] and Galilee in the north, and with ], ] and ] in the east for control of ];<ref name="thompson408" /> the ] ({{circa|{{BCE|830}}}}), left by a king of Moab, celebrates his success in throwing off the oppression of the "House of ]" (i.e., Israel). It bears what is generally thought to be the earliest extra-biblical reference to the name "]".<ref name="Miller2000">{{cite book |last=Miller |first=Patrick D. |author-link=Patrick D. Miller |title=The Religion of Ancient Israel |year=2000 |publisher= Westminster John Knox Press |isbn=978-0-664-22145-4 |pages=40– |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=JBhY9BQ7hIQC&pg=PA40}}</ref> A century later Israel came into increasing conflict with the expanding ], which first split its territory into several smaller units and then destroyed its capital, Samaria ({{BCE|722}}). Both the biblical and Assyrian sources speak of a massive deportation of people from Israel and their replacement with settlers from other parts of the empire{{snd}} such ] were an established part of Assyrian imperial policy, a means of breaking the old power structure{{snd}} and the former Israel never again became an independent political entity.<ref>Lemche 1998, p. 85.</ref> | |||

| Babylonian Judah suffered a steep decline in both economy and population<ref> p.28</ref> and lost the Negev, the Shephelah, and part of the Judean hill country, including Hebron, to encroachments from Edom and other neighbours.<ref> p.291</ref> Jerusalem, while probably not totally abandoned, was much smaller than previously, and the town of ] in the relatively unscathed northern section of the kingdom became the capital of the new Babylonian province of ].<ref></ref> (This was standard Babylonian practice: when the Philistine city of ] was conquered in 604 BCE, the political, religious and economic elite (but not the bulk of the population) was banished and the administrative centre shifted to a new location).<ref> p.48</ref> There is also a strong probability that for most or all of the period the temple at ] in Benjamin replaced that at Jerusalem, boosting the prestige of Bethel's priests (the Aaronites) against those of Jerusalem (the Zadokites), now in exile in Babylon.<ref> pp.103-5</ref> | |||

| ] King of Israel giving tribute to the ] king ] on the ] from ] ({{circa|BCE|841–840}})]] | |||

| The Babylonian conquest entailed not just the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple, but the liquidation of the entire infrastructure which had sustained Judah for centuries.<ref> p.228</ref> The most significant casualty was the State ideology of "Zion theology,"<ref> pp.1-2</ref> the idea that ], the god of Israel, had chosen Jerusalem for his dwelling-place and that the ] would reign there forever.<ref> p.203</ref> The fall of the city and the end of Davidic kingship forced the leaders of the exile community - kings, priests, scribes and prophets - to reformulate the concepts of community, faith and politics.<ref> p.2</ref> The exile community in Babylon thus became the source of significant portions of the Hebrew bible: ] 40-55, ], the final version of ], the work of the ] in the Pentateuch, and the final form of the history of Israel from ] to ]<ref name="Jrpx-op_-XkC 2005 p.10"> p.10</ref> Theologically, they were responsible for the doctrines of individual responsibility and universalism (the concept that one god controls the entire world), and for the increased emphasis on purity and holiness.<ref name="Jrpx-op_-XkC 2005 p.10"/> Most significantly, the trauma of the exile experience led to the development of a strong sense of identity as a people distinct from other peoples,<ref> p.17</ref> and increased emphasis on symbols such as circumcision and Sabbath-observance to maintain that separation.<ref> p.48</ref> | |||

| Finkelstein holds that Judah emerged as an operational kingdom somewhat later than Israel, during the second half of 9th century BCE,<ref name="Finkelstein, Israel, (2020)" /> but the subject is one of considerable controversy.<ref>Grabbe (2008), pp. 225–26.</ref> There are indications that during the 10th and 9th centuries BCE, the southern highlands had been divided between a number of centres, none with clear primacy.<ref>Lehman in Vaughn 1992, p. 149.</ref> During the reign of ], between {{circa|{{BCE|715 and 686}}}}, a notable increase in the power of the Judean state can be observed.<ref>David M. Carr, ''Writing on the Tablet of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature'', Oxford University Press, 2005, 164.</ref> This is reflected in archaeological sites and findings, such as the ]; a defensive city wall in Jerusalem; and the ], an aqueduct designed to provide Jerusalem with water during an impending siege by the Neo-Assyrian Empire led by ]; and the ], a lintel inscription found over the doorway of a tomb, has been ascribed to comptroller ]. ]s on storage jar handles, excavated from strata in and around that formed by Sennacherib's destruction, appear to have been used throughout Sennacherib's 29-year reign, along with ] from sealed documents, some that belonged to Hezekiah himself and others that name his servants.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.lmlk.com/research/lmlk_ahoh.htm|title=LAMRYEU-HNNYEU-OBD-HZQYEU|website=www.lmlk.com}}</ref>{{Self-published inline|date=April 2024}} | |||

| ], son of ], king of Judah" – royal ] found at the ] excavations in Jerusalem]] | |||

| Archaeological records indicate that the Kingdom of Israel was fairly prosperous. The late Iron Age saw an increase in urban development in Israel. Whereas previously the Israelites had lived mainly in small and unfortified settlements, the rise of the Kingdom of Israel saw the growth of cities and the construction of palaces, large royal enclosures, and fortifications with walls and gates. Israel initially had to invest significant resources into defence as it was subjected to regular ] incursions and attacks, but after the Arameans were subjugated by the Assyrians and Israel could afford to put less resources into defending its territory, its architectural infrastructure grew dramatically. Extensive fortifications were built around cities such as ], ], and ], including monumental and multi-towered city walls and multi-gate entry systems. Israel's economy was based on multiple industries. It had the largest olive oil production centres in the region, using at least two different types of olive oil presses, and also had a significant wine industry, with wine presses constructed next to vineyards.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.worldhistory.org/Israelite_Technology/|title=Ancient Israelite Technology|first=William|last=Brown|website=World History Encyclopedia}}</ref> By contrast, the Kingdom of Judah was significantly less advanced. Some scholars believe it was no more than a small tribal entity limited to Jerusalem and its immediate surroundings.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.haaretz.com/2011-05-06/ty-article/the-keys-to-the-kingdom/0000017f-f749-d47e-a37f-ff7ddabf0000|title=The Keys to the Kingdom|newspaper=Haaretz}}</ref> In the 10th and early 9th centuries BCE, the territory of Judah appears to have been sparsely populated, limited to small and mostly unfortified settlements. The status of Jerusalem in the 10th century BCE is a major subject of debate among scholars. According to some scholars, Jerusalem does not show evidence of significant Israelite residential activity until the 9th century BCE.<ref>Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E. (17 May 2011). . {{ISBN|978-0-8028-6260-0}}.</ref> Other scholars argue that recent discoveries and radiocarbon tests in the ] seem to indicate that Jerusalem was already a significant city by the 10th century BCE.<ref>{{Cite book |title=The Two Houses of Israel: State Formation and the Origins of Pan-Israelite Identity |last=Sergi |first=Omer |publisher=SBL Press |year=2023 |isbn=978-1-62837-345-5 |page=197 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4nLMEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA187}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=Radiocarbon chronology of Iron Age Jerusalem reveals calibration offsets and architectural developments |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |last1=Regev |first1=Johanna |date=2024-04-29 |issue=19 |volume=121 |pages=e2321024121 |last2=Gadot |first2=Yuval |doi=10.1073/pnas.2321024121 |issn=0027-8424 |pmid=38683984 |pmc=11087761 |last3=Uziel |first3=Joe |last4=Chalaf |first4=Ortal |last5=Shalev |first5=Yiftah |last6=Roth |first6=Helena |last7=Shalom |first7=Nitsan |last8=Szanton |first8=Nahshon |last9=Bocher |first9=Efrat |last10=Pearson |first10=Charlotte L. |last11=Brown |first11=David M. |last12=Mintz |first12=Eugenia |last13=Regev |first13=Lior |last14=Boaretto |first14=Elisabetta |bibcode=2024PNAS..12121024R }}</ref> Significant administrative structures such as the ] and ], which originally formed part of one structure, also contain material culture from the 10th century BCE or earlier.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://www.academia.edu/2503754|title=Archaeology and the Biblical Narrative: The Case of the United Monarchy|first=Amihai|last=Mazar|date=19 September 2010|journal=One God – One Cult – One Nation|pages=29–58|doi=10.1515/9783110223583.29 |isbn=978-3-11-022357-6 |via=www.academia.edu}}</ref> The ruins of a significant Judahite military fortress, ], have also been found in the Negev, and a collection of military orders found there suggest literacy was present throughout the ranks of the Judahite army. This suggests that literacy was not limited to a tiny elite, indicating the presence of a substantial educational infrastructure in Judah.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.timesofisrael.com/new-look-at-ancient-shards-suggests-bible-even-older-than-thought/|title=New look at ancient shards suggests Bible even older than thought|website=Times of Israel}}</ref>] found in the ], Jerusalem (c. 700 BCE)]]In the 7th century Jerusalem grew to contain a population many times greater than earlier and achieved clear dominance over its neighbours.<ref name="thompson410">Thompson 1992, pp. 410–11.</ref> This occurred at the same time that Israel was being destroyed by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and was probably the result of a cooperative arrangement with the Assyrians to establish Judah as an Assyrian vassal state controlling the valuable olive industry.<ref name="thompson410" /> Judah prospered as a vassal state (despite a ]), but in the last half of the 7th century BCE, Assyria suddenly collapsed, and the ensuing competition between Egypt and the ] for control of the land led to the destruction of Judah in a series of campaigns between 597 and 582.<ref name="thompson410" /> | |||

| ==Aftermath: Assyrian and Babylonian periods== | |||

| The concentration of the biblical literature on the experience of the exiles in Babylon disguises the fact that the great majority of the population remained in Judah, and for them life after the fall of Jerusalem probably went on much as it had before.<ref> p.109</ref> It may even have improved, as they were rewarded with the land and property of the deportees, much to the anger of the exile community in Babylon.<ref> p.92</ref> The assassination of the Babylonian governor around 582 BCE by a disaffected member of the former royal house of David provoked a Babylonian crack-down, possibly reflected in the ], but the situation seems to have soon stabilised again.<ref> pp.95-96</ref> Nevertheless, the unwalled cities and towns that remained were subject to slave raids by the Phoenicians and intervention in their internal affairs from Samaritans, Arabs and Ammonites.<ref> p.96</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Samerina|Yehud (Babylonian province)}} | |||

| After its fall, the former Kingdom of Israel became the Assyrian province of ], which was taken over about a century later by the Neo-Babylonian Empire, created after the revolt of the Babylonians and them defeating the Neo-Assyrian Empire. | |||

| ==Persian period (539-332 BCE)== | |||

| ], written in ], which documented the condition of the exiled Judean community in Babylon]] | |||

| Babylon was conquered by ] in 539 BCE and Judah (or ], the "province of Yehud") remained a province of the ] until 332 BCE. Cyrus was succeeded as king by ], who added Egypt to the empire, incidentally transforming Yehud and the Philistine plain into an important frontier zone; his death in 522 was followed by a period of turmoil until ] seized the throne in about 521. Darius introduced a reform of the administrative arrangements of the empire including the collection, codification and administration of local law codes, and it is reasonable to suppose that this policy lay behind the redaction of the Jewish ].<ref name="PvirfZkfvQC 1988 p.64"> p.64</ref> After 404 BCE the Persians lost control of Egypt, which now became Persia's main enemy outside Europe, causing the Persian authorities to tighten their administrative control over Yehud and the rest of Palestine.<ref> pp.86-9</ref> Egypt was eventually reconquered, but soon afterward Persia fell to ], ushering in the Hellenistic period in the Levant. | |||

| Babylonian Judah suffered a steep decline in both economy and population<ref>Grabbe 2004, p. 28.</ref> and lost the Negev, the Shephelah, and part of the Judean hill country, including Hebron, to encroachments from ] and other neighbours.<ref>] in Blenkinsopp 2003, p. 291.</ref> Jerusalem, destroyed but probably not totally abandoned, was much smaller than previously, and the settlements surrounding it, as well as the towns in the former kingdom's western borders, were all devastated as a result of the Babylonian campaign. The town of ] in the relatively unscathed northern section of the kingdom became the capital of the new Babylonian province of ].<ref>Davies 2009.</ref><ref name=":4">{{Cite journal |last=Lipschits |first=Oded |date=1999 |title=The History of the Benjamin Region under Babylonian Rule |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/tav.1999.1999.2.155 |journal=Tel Aviv |volume=26 |issue=2 |pages=155–190 |doi=10.1179/tav.1999.1999.2.155 |issn=0334-4355 |quote=The destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians (586 B.C.E.) is the most traumatic event described in biblical historiography, and in its shadow the history of the people of Israel was reshaped. The harsh impression of the destruction left its mark on the prophetic literature also, and particular force is retained in the laments over the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in its midst. most of Judah's inhabitants remained there after the destruction of Jerusalem. They concentrated chiefly in the Benjamin region and the northern Judean hill country. This area was hardly affected by the destruction, and became the centre of the Babylonian province with its capital at Mizpah. The archaeological data reinforce the biblical account, and they indicate that Jerusalem and its close environs suffered a severe blow. Most of the small settlements near the city were destroyed, the city wall was demolished, and the buildings within were put to the torch. Excavation and survey data show that the western border of the kingdom also sustained a grave onslaught, seemingly at the time when the Babylonians went to besiege Jerusalem.}}</ref> This was standard Babylonian practice: when the Philistine city of ] was conquered in 604, the political, religious and economic elite (but not the bulk of the population) was banished and the administrative centre shifted to a new location.<ref>Lipschits 2005, p. 48.</ref> There is also a strong probability that for most or all of the period the temple at ] in Benjamin replaced that at Jerusalem, boosting the prestige of Bethel's priests (the Aaronites) against those of Jerusalem (the Zadokites), now in exile in Babylon.<ref>Blenkinsopp in Blenkinsopp 2003, pp. 103–05.</ref> | |||

| The Babylonian conquest entailed not just the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple, but the liquidation of the entire infrastructure which had sustained Judah for centuries.<ref>Blenkinsopp 2009, p. 228.</ref> The most significant casualty was the state ideology of "Zion theology,"<ref>Middlemas 2005, pp. 1–2.</ref> the idea that the god of Israel had chosen Jerusalem for his dwelling-place and that the ] would reign there forever.<ref>Miller 1986, p. 203.</ref> The fall of the city and the end of Davidic kingship forced the leaders of the exile community{{snd}} kings, priests, scribes and prophets{{snd}} to reformulate the concepts of community, faith and politics.<ref>Middlemas 2005, p. 2.</ref> The exile community in Babylon thus became the source of significant portions of the Hebrew Bible: ] 40–55; ]; the final version of ]; the work of the hypothesized ] in the ]; and the final form of the history of Israel from ] to ].<ref name="middlemas10">Middlemas 2005, p. 10.</ref> Theologically, the Babylonian exiles were responsible for the doctrines of individual responsibility and universalism (the concept that one god controls the entire world) and for the increased emphasis on purity and holiness.<ref name="middlemas10" /> Most significantly, the trauma of the exile experience led to the development of a strong sense of Hebrew identity distinct from other peoples,<ref>Middlemas 2005, p. 17.</ref> with increased emphasis on symbols such as circumcision and Sabbath-observance to sustain that distinction.<ref>Bedford 2001, p. 48.</ref> | |||

| Judah's population over the entire period was probably never more than about 30,000, and that of Jerusalem no more than about 1,500, most of them connected in some way to the Temple.<ref> p.29-30</ref> According to the biblical history, one of the first acts of ], the Persian conqueror of Babylon, was to commission the Jewish exiles to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple, a task which they are said to have completed c.515 BCE.<ref> p.25</ref> Yet it was probably only in the middle of the next century, at the earliest, that Jerusalem again became the capital of Judah.<ref> p.141</ref> The Persians may have experimented initially with ruling Yehud as a Dividic client-kingdom under descendants of ],<ref></ref> but by the mid-5th century Yehud had become in practice a theocracy, ruled by hereditary High Priests<ref></ref> and a Persian-appointed governor, frequently Jewish, charged with keeping order and seeing that tribute was paid.<ref></ref> According to the biblical history ] and ] arrived in Jerusalem in the middle of the 5th century, the first empowered by the Persian king to enforce the Torah, the second with the status of governor and a royal mission to restore the walls of the city.<ref> p.311</ref> The biblical history mentions tension between the returnees and those who had remained in Yehud, the former rebuffing the attempt of the "peoples of the land" to participate in the rebuilding of the Temple; this attitude was based partly on the exclusivism which the exiles had developed while in Babylon and, probably, partly on disputes over property.<ref> p.458</ref> The careers of ] and ] in the 5th century were thus a kind of religious colonisation in reverse, an attempt by one of the many Jewish factions in Babylon to create a self-segregated, ritually pure society inspired by the prophesies of ] and his followers.<ref> p.229</ref> | |||

| ] writes that the concentration of the biblical literature on the experience of the exiles in Babylon disguises that the great majority of the population remained in Judah; for them, life after the fall of Jerusalem probably went on much as it had before.<ref>Barstad 2008, p. 109.</ref> It may even have improved, as they were rewarded with the land and property of the deportees, much to the anger of the community of exiles remaining in Babylon.<ref>Albertz 2003a, p. 92.</ref> Conversely, ] writes that archaeological and demographic surveys show that the population of Judah was significantly reduced to barely 10% of what it had been in the time before the exile.<ref>Faust, Avraham (2012). '''' Society of Biblical Lit. p. 140. {{ISBN|978-1-58983-641-9}}.</ref> The assassination around 582 of the Babylonian governor by a disaffected member of the former royal House of David provoked a Babylonian crackdown, possibly reflected in the ], but the situation seems to have soon stabilized again.<ref>Albertz 2003a, pp. 95–96.</ref> Nevertheless, those unwalled cities and towns that remained were subject to slave raids by the Phoenicians and intervention in their internal affairs by ]s, Arabs, and Ammonites.<ref>Albertz 2003a, p. 96.</ref> | |||

| The Persian era, and especially the period 538-400 BCE, laid the foundations of later Jewish and Christian religion and the beginnings of a scriptural canon.<ref> pp.437-8</ref> other important landmarks include the replacement of Hebrew by Aramaic as the everyday language of Judah (although it continued to be used for religious and literary purposes),<ref> pp.109-110</ref> and Darius's reform of the administrative arrangements of the empire, which may lie behind the redaction of the Jewish ].<ref name="PvirfZkfvQC 1988 p.64"/> | |||

| ==Religion== | |||

| == Hellenistic period (332 BCE - 6 CE) == | |||

| Although the specific process by which the Israelites adopted ] is unknown, it is certain that the transition was a gradual one and was not totally accomplished during the First Temple period.<ref name=":1" />{{Page needed|date=April 2024}} More is known about this period, as during this time writing was widespread.<ref>{{Cite news |date=7 September 2022 |editor-last=Benn |editor-first=Aluf |title=Israel Regains Rare Ancient Hebrew Papyrus From First Temple Period |url=https://www.haaretz.com/archaeology/2022-09-07/ty-article/israel-regains-rare-ancient-hebrew-papyrus-from-first-temple-period/00000183-1728-d6f3-a7ff-ffea08eb0000 |work=]}}</ref> The number of gods that the Israelites worshipped decreased, and figurative images vanished from their shrines. ], as some scholars name this belief system, is often described as a form of ] or ]. Over the same time, a ] continued to be practised across Israel and Judah. These practices were influenced by the polytheistic beliefs of the surrounding ethnicities, and were denounced by the prophets.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Dever |first=William G. |date=2019-12-12 |title=Archaeology and Folk or Family Religion in Ancient Israel |journal=Religions |volume=10 |issue=12 |pages=667 |doi=10.3390/rel10120667 |issn=2077-1444|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |first=Bob |last=Becking |url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/1052587466 |title=Only One God? : Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah. |date=2002 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |isbn=978-0-567-23212-0 |oclc=1052587466}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=April 2024}}<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Stern |first=Ephraim |date=2001 |title=Pagan Yahwism: The folk religion of ancient Israel |journal=Biblical Archaeology Review |volume=27 |issue=3 |pages=20–29}}</ref> | |||

| ] kingdom]] | |||

| ] and surrounding area in the 1st century]] | |||

| In addition to the ], there was public worship practised all over Israel and Judah in shrines and sanctuaries, outdoors, and close to city gates. In the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, the kings Hezekiah and Josiah of Judah implemented a number of significant religious reforms that aimed to centre worship of the God of Israel in Jerusalem and eliminate foreign customs.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Finkelstein |first1=Israel |last2=Silberman |first2=Neil Asher |date=2006 |title=Temple and Dynasty: Hezekiah, the Remaking of Judah and the Rise of the Pan-Israelite Ideology |url=http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0309089206063428 |journal=Journal for the Study of the Old Testament |volume=30 |issue=3 |pages=259–285 |doi=10.1177/0309089206063428 |s2cid=145087584 |issn=0309-0892}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |last=Moulis |first=David Rafael |title=Hezekiah's Cultic Reforms according to the Archaeological Evidence |date=2019-11-08 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvr7fc18.11 |work=The Last Century in the History of Judah |pages=167–180 |publisher=SBL Press |doi=10.2307/j.ctvr7fc18.11 |s2cid=211652647 |access-date=2023-02-18}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Na’aman |first=Nadav |date=2011-01-01 |title=The Discovered Book and the Legitimation of Josiah's Reform |url=https://doi.org/10.2307/41304187 |journal=Journal of Biblical Literature |volume=130 |issue=1 |pages=47–62 |doi=10.2307/41304187 |jstor=41304187 |s2cid=153646048 |issn=0021-9231}}</ref> | |||

| On the death of ] (322 BCE) his generals divided the empire between them. ] seized Egypt and Palestine, but his successors lost Palestine and Judea to the ], the rulers of Syria, in 198 BCE. At first relations between the Seleucids and the Jews were cordial, but the attempt of ] (174-163 BCE) to impose Hellenic culture sparked a national rebellion, which ended in the expulsion of the Syrians and the establishment of an independent Jewish kingdom under the ] dynasty. The Hasmonean kingdom was a conscious attempt to revive the Judah described in the bible: a Jewish monarchy ruled from Jerusalem and stretching over all the territories once ruled by David and Solomon. In order to carry out this project the ]s kings and forcibly converted to Judaism the one-time Moabites, Edomites and Ammonites, as well as the lost kingdom of Israel.<ref></ref> | |||

| ===Henotheism=== | |||

| In 64 BCE the Roman general ] conquered Jerusalem and made the Jewish kingdom a ] of Rome. In 57-55 BCE ], proconsul of ], split it into ], ] & ],<ref></ref> In 40-39 BCE ] was appointed ] by the ],<ref>.14.4</ref> and in 6 CE the last ] of Judea was deposed by the emperor ] and his territories annexed as ] under direct ] administration: this marked the end Judah as an even theoretically independent kingdom.<ref>H.H. Ben-Sasson, ''A History of the Jewish People'', Harvard University Press, 1976, ISBN 0-674-39731-2, page 246</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] is the act of worshipping a single god, without denying the existence of other deities.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.dictionary.com/browse/henotheism|title=the definition of henotheism|website=Dictionary.com|language=en|access-date=2019-04-26}}</ref> Many scholars believe that before monotheism in ancient Israel, there came a transitional period; in this transitional period many followers of the Israelite religion worshipped the god Yahweh, but did not deny the existence of other deities accepted throughout the region.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book|title=The Routledge Companion to Theism|last1=Taliaferro|first1=Charles|last2=Harrison|first2=Victoria S.|last3=Goetz|first3=Stewart|publisher=Routledge|year=2012}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=April 2024}} Henotheistic worship was not uncommon in the Ancient Near East, as many Iron Age nation states worshipped an elevated ] which was nonetheless only part of a wider pantheon; examples include ] in ], ] in ], ] in ], and ] in ].<ref name="Levine">{{Cite journal|last=Levine|first=Baruch A.|author-link=Baruch A. Levine|title=Assyrian Ideology and Israelite Monotheism|journal=British Institute for the Study of Iraq|volume=67|issue=1|pages=411–27|jstor=4200589|year=2005}}</ref> | |||

| ] syncretized elements from neighbouring cultures, largely from ] traditions.<ref name="Meek">{{Cite journal|last=Meek|first=Theophile James|author-link=Theophile James Meek|year=1942|title=Monotheism and the Religion of Israel|journal=]|volume=61|issue=1|pages=21–43|doi=10.2307/3262264|jstor=3262264}}</ref> Using Canaanite religion as a base was natural due to the fact that the Canaanite culture inhabited the same region prior to the emergence of Israelite culture.<ref name="Dever">{{Cite journal|last=Dever|first=William|title=Archaeological Sources for the History of Palestine: The Middle Bronze Age: The Zenith of the Urban Canaanite Era|journal=]|volume=50|issue=3|pages=149–77|jstor=3210059|year=1987|doi=10.2307/3210059|s2cid=165335710}}</ref> Israelite religion was no exception, as during the transitional period, Yahweh and ] were syncretized in the Israelite pantheon.<ref name="Dever" /> El already occupied a reasonably important place in the Israelite religion. Even the name "Israel" is based on the name El, rather than Yahweh.<ref name="Coogan">{{cite book |last1=Coogan |first1=Michael David |title=The Oxford History of the Biblical World |date=2001 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-513937-2 |page=54 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4DVHJRFW3mYC&q=name+Israel+comes+from+El&pg=PA54 |access-date=3 November 2019 }}</ref><ref>Smith 2002, p. 32.</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Giliad |first1=Elon |title=Why Is Israel Called Israel? |url=https://www.haaretz.com/.premium-why-is-israel-called-israel-1.5353207 |access-date=3 November 2019 |work=Haaretz |date=20 April 2015 |language=en}}</ref> It was this initial harmonization of Israelite and Canaanite religious thought that led to Yahweh gradually absorbing several characteristics from Canaanite deities, in turn strengthening his own position as an all-powerful "One." Even still, monotheism in the region of ancient Israel and Judah did not take hold overnight, and during the intermediate stages most people are believed to have remained henotheistic.<ref name="Meek" /> | |||

| == Religion == | |||

| It is generally accepted among modern scholars that the narrative of Israel's history found in the biblical ] is not an accurate reflection of the religious world of Iron Age Judah and Israel.<ref> p.27</ref> Contrary to the biblical picture, Israelite monotheism was not a primordial condition, but the end result of a gradual process which began with the normal beliefs and practices of the ancient world.<ref> pp.62-3</ref> | |||

| During this intermediate period of henotheism many families worshipped different gods. Religion was very much centred around the family, as opposed to the community. The region of Israel and Judah was sparsely populated during the time of Moses. As such many different areas worshipped different gods, due to social isolation.<ref name="Caquot">{{Cite journal|last=Caquot|first=André|author-link=André Caquot|title=At the Origins of the Bible|journal=]|volume=63|issue=4|pages=225–27|jstor=3210793|year=2000|doi=10.2307/3210793|s2cid=164106346}}</ref> It was not until later on in Israelite history that people started to worship Yahweh alone and fully convert to monotheistic values. That switch occurred with the growth of power and influence of the Israelite kingdom and its rulers. Further details of this are contained in the Iron Age Yahwism section below. Evidence from the Bible suggests that henotheism did exist: "They went and served alien gods and paid homage to them, gods of whom they had no experience and whom he did not allot to them" (Deut. 29.26). Many believe that this quote demonstrates that the early Israelite kingdom followed traditions similar to ancient Mesopotamia, where each major urban centre had a supreme god. Each culture embraced their patron god but did not deny the existence of other cultures' patron gods. In Assyria, the patron god was Ashur, and in ancient Israel, it was Yahweh; however, both Israelite and Assyrian cultures recognized each other's deities during this period.<ref name="Caquot" /> Some scholars have used the Bible as evidence to argue that most of the people alive during the events recounted in the Hebrew Bible, including Moses, were most likely henotheists. There are many quotes from the Hebrew Bible that are used to support this view. One such quote from Jewish tradition is the first commandment which in its entirety reads "I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage: You shall have no other gods before me."<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.sefaria.org/Exodus.20.3?lang=bi&aliyot=0|title=Exodus 20:2|website=www.sefaria.org|access-date=2023-01-21}}</ref> This quote does not deny the existence of other gods; it merely states that Jews should consider Yahweh or God the supreme god, incomparable to other supernatural beings. Some scholars attribute the concept of angels and demons found in Judaism and Christianity to the tradition of henotheism. Instead of completely getting rid of the concept of other supernatural beings, these religions changed former deities into angels and demons.<ref name=Meek/> | |||

| Israel and Judah inherited the religion of late first-millennium Canaan, and Canaanite religion in turn had its roots in the religion of second-millennium ].<ref name="Toorn 1999">Karel van der Toorn, editor, "Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible" (second edition, Eerdmans, 1999)</ref> In the 2nd millennium, polytheism was expressed through the concepts of the divine council and the divine family, a single entity with four levels: the chief god and his wife (] and ]); the seventy divine children or "stars of El" (including ], ], ], probably ], as well as the ] and the moon-god ]); the head helper of the divine household, ]; and the servants of the divine household, including the messenger-gods who would later appear as the "]" of the Hebrew bible.<ref>Robert Karl Gnuse, "No Other Gods: Emergent Monotheism in Israel" (Sheffield Academic Press, 1997)</ref> | |||

| ===Iron Age Yahwism=== | |||

| In the earliest stage, ] was one of the seventy children of El, each of whom was the patron deity of one of the seventy nations. This is illustrated by the ] and ] texts of Deuteronomy 32:8-9, in which El, as the head of the divine assembly, gives member of the divine family a nation of his own, "according to the number of the divine sons": Israel is the portion of Yahweh.<ref>Meindert Djikstra, "El the God of Israel, Israel the People of YHWH: On the Origins of Ancient Israelite Yahwism" (in "Only One God? Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah", ed. Bob Beckering, Sheffield Academic Press, 2001)</ref> The later ], evidently uncomfortable with the polytheism expressed by the phrase, altered it to "according to the number of the children of Israel"<ref>Meindert Djikstra, "I have Blessed you by Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah: Texts with Religious Elements from the Soil Archive of Ancient Israel" (in "Only One God? Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah", ed. Bob Beckering, Sheffield Academic Press, 2001)</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Yahwism}} | |||

| ] god ], 14th–12th century BCE (] museum, Paris)]] | |||

| The religion of the Israelites of Iron Age I, like the ] from which it evolved and other ], was based on a cult of ancestors and worship of family gods (the "gods of the fathers").<ref>Tubbs, Jonathan (2006) "The Canaanites" (BBC Books)</ref><ref>Van der Toorn 1996, p. 4.</ref> With the emergence of the monarchy at the beginning of Iron Age II the kings promoted their family god, Yahweh, as the god of the kingdom, but beyond the royal court, religion continued to be both polytheistic and family-centred.<ref>Van der Toorn 1996, pp. 181–82.</ref> The major deities were not numerous{{snd}}El, ], and Yahweh, with ] as a fourth god, and perhaps ] (the sun) in the early period.<ref name=Smith57>Smith (2002), p. 57.</ref> At an early stage El and Yahweh became fused and Asherah did not continue as a separate state cult,<ref name=Smith57/> although she continued to be popular at a community level until Persian times.<ref>Dever (2005), p.</ref> | |||

| Yahweh, the ] of both Israel and Judah, seems to have originated in ] and ] in southern Canaan and may have been brought to Israel by the ] and ] at an early stage.<ref>Van der Toorn 1999, pp. 911–13.</ref> There is a general consensus among scholars that the first formative event in the emergence of the distinctive religion described in the Bible was triggered by the destruction of Israel by Assyria in {{circa|{{BCE|722}}}}. Refugees from the northern kingdom fled to Judah, bringing with them laws and a prophetic tradition of Yahweh. This religion was subsequently adopted by the landowners of Judah, who in 640 BCE placed the eight-year-old ] on the throne. Judah at this time was a vassal state of Assyria, but Assyrian power collapsed in the 630s, and around 622 Josiah and his supporters launched a bid for independence expressed as loyalty to "Yahweh alone".<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4DVHJRFW3mYC&q=josiah%2C+book+of+kings%2C+assyria&pg=RA1-PA261|title=The Oxford History of the Biblical World|first1=Michael David|last1=Coogan|date=January 8, 2001|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780195139372|page=261|via=Google Books}}</ref> | |||

| Between the eighth to the sixth centuries El became identified with Yahweh, Yahweh-El became the husband of the goddess Asherah, and the other gods and the divine messengers gradually became mere expressions of Yahweh's power.<ref>Karel van der Toorn, "Goddesses in Early Israelite Religion in Ancient Goddesses: the Myths and the Evidence" (editors Lucy Goodison and Christine Morris, University of Wisconsin Press, 1998)</ref> Yahweh is cast in the role of the Divine King ruling over all the other deities, as in Psalm 29:2, where the "sons of God" are called upon to worship Yahweh; and as Ezekiel 8-10 suggests, the Temple itself became Yahweh's palace, populated by those in his retinue.<ref name="Toorn 1999"/> | |||

| ===<span id="Second Temple">The Babylonian exile and Second Temple Judaism</span>=== | |||

| It is in this period that the earliest clear monotheistic statements appear in the Bible, for example in the apparently seventh-century Deuteronomy 4:35, 39, 1 Samuel 2:2, 2 Samuel 7:22, 2 Kings 19:15, 19 (= Isaiah 37:16, 20), and Jeremiah 16:19, 20 and the sixth-century portion of Isaiah 43:10-11, 44:6, 8, 45:5-7, 14, 18, 21, and 46:9.<ref>Ziony Zevit, "The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches (Continuum, 2001)</ref> Because many of the passages involved appear in works associated with either Deuteronomy, the Deuteronomistic History (Joshua through Kings) or in Jeremiah, most recent scholarly treatments have suggested that a Deuteronomistic movement of this period developed the idea of monotheism as a response to the religious issues of the time.<ref name="Mark S 2001">Mark S.Smith, "Untold Stories: The Bible and Ugaritic Studies in the Twentieth Century" (Hendrickson Publishers, 2001)</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Second Temple Judaism}} | |||

| According to the ]s, as scholars call these Judean nationalists, the treaty with Yahweh would enable Israel's god to preserve both the city and the king in return for the people's worship and obedience. The destruction of Jerusalem, its Temple, and the Davidic dynasty by Babylon in 587/586 BCE was deeply traumatic and led to revisions of the national ] during the Babylonian exile. This revision was expressed in the ], the books of ], ], ] and ], which interpreted the Babylonian destruction as divinely-ordained punishment for the failure of Israel's kings to worship Yahweh to the exclusion of all other deities.<ref name=Dunn>Dunn and Rogerson, pp. 153–54</ref> | |||

| The ] (520 BCE{{snd}}70 CE) differed in significant ways from what had gone before.<ref>Peck & Neusner, eds. (2003), p. 58</ref> Strict monotheism emerged among the priests of the Temple establishment during the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, as did beliefs regarding ]s and ]s.<ref>Grabbe (2004), pp. 243–44.</ref> At this time, ], dietary laws, and ] gained more significance as symbols of ], and the institution of the ] became increasingly important, and most of the biblical literature, including the Torah, was substantially revised during this time.<ref>Peck & Neusner, eds. (2003), p. 59</ref> | |||

| The first factor behind this development involves changes in Israel's social structure. At Ugarit, social identity was strongest at the level of the family: legal documents, for example, were often made between the sons of one family and the sons of another. Ugarit's religion, with its divine family headed by El and Asherah, mirrored this human reality.<ref>Mark S. Smith and Patrick D Miller, "The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel" (Harper & Row, 1990)</ref> The same was true in ancient Israel through most of the monarchy - for example, the story of Achan in Joshua 8 suggests an extended family as the major social unit. However, the family lineages went through traumatic changes beginning in the eighth century due to major social stratification, followed by Assyrian incursions. In the seventh and sixth centuries, we begin to see expressions of individual identity (Deuteronomy 26:16; Jeremiah 31:29-30; Ezekiel 18). A culture with a diminished lineage system, deteriorating over a long period from the ninth or eighth century onward, less embedded in traditional family patrimonies, might be more predisposed both to hold the individual accountable for his behavior, and to see an individual deity accountable for the cosmos. In short, the rise of the individual as the basic social unit led to the rise of a single god replacing a divine family.<ref>Mark S. Smith, "Untold Stories: The Bible and Ugaritic Studies in the Twentieth Century" (Hendrickson Publishers, 2001)</ref> | |||

| == Administrative and judicial structure == | |||

| The second major factor was the rise of the ] and ] empires. As long as Israel was, from its own perspective, part of a community of similar small nations, it made sense to see the Israelite pantheon on par with the other nations, each one with its own patron god - the picture described with Deuteronomy 32:8-9. The assumption behind this worldview was that each nation was as powerful as its patron god.<ref>William G. Dever, "Did God Have a Wife? Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel" (Eerdman's, 2005)</ref> However, the neo-Assyrian conquest of the northern kingdom in ca. 722 challenged this, for if the neo-Assyrian empire were so powerful, so must be its god; and conversely, if Israel could be conquered (and later Judah, c. 586), it implied that Yahweh in turn was a minor divinity. The crisis was met by separating the heavenly power and earthly kingdoms. Even though Assyria and Babylon were so powerful, the new monotheistic thinking in Israel reasoned, this did not mean that the god of Israel and Judah was weak. ] had not succeeded because of the power of its god ]; it was Yahweh who was using ] to punish and purify the one nation which Yahweh had chosen.<ref name="Mark S 2001"/> | |||

| ], son of ], king of Judah" – royal ] found at the ] excavations in Jerusalem]] | |||

| As was customary in the ], a king ({{Langx|he|מלך|translit=melekh}}) ruled over the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. The national god Yahweh, who selects those to rule his realm and his people, is depicted in the Hebrew Bible as having a hand in the establishment of the royal institution. In this sense, the true king is God, and the king serves as his earthly envoy and is tasked with ruling his realm. In some ] that appear to be related to the coronation of kings, they are referred to as "sons of Yahweh". The kings actually had to succeed one another according to a dynastic principle, even though the succession was occasionally decided through ]. The coronation seemed to take place in a sacred place, and was marked by the ] of the king who then becomes the "anointed one (māšîaḥ, the origin of the word ]) of Yahweh"; the end of the ritual seems marked by an acclamation by the people (or at least their representatives, the Elders), followed by a banquet.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Ahlström |first=G.W. |url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/213021257 |title=Civilizations of the Ancient Near East |date=1995 |publisher=Hendrickson Publishers |isbn=978-1-56563-607-1 |editor-last=Sasson, Jack |editor-first=M. |pages=590–595 |chapter=Administration of the State in Canaan and Ancient Israel |oclc=213021257}}</ref> | |||

| The Bible's descriptions of the lists of dignitaries from the reigns of David and Solomon show that the king is supported by a group of high dignitaries. Those include the chief of the army ({{Langx|he|שר הצבא|translit=śar haṣṣābā|link=no}}), the great scribe ({{Langx|he|שר הצבא|translit=śar haṣṣābā|link=no}}) who was in charge of the management of the royal chancellery, the herald ({{Langx|he|מזכיר|translit=mazkîr|link=no}}), as well as the high priest ({{Langx|he|כהן הגדול|translit=kōhēn hāggādôl|link=no}}) and the master of the palace ({{Langx|he|על הבית, סוכן|translit=ʿal-habbayit, sōkēn|link=no}}), who has a function of stewardship of the household of the king at the beginning and seems to become a real prime minister of Judah during the later periods. The attributions of most of these dignitaries remain debated, as illustrated in particular by the much-discussed case of the “king's friend” mentioned under Solomon.<ref name=":0" /><ref>Eph’al Jaruzelska, I. (2010). "Officialdom and Society in the Book of Kings: The Social Relevance of the State." In ''The Books of Kings'' (pp. 471–480). Brill.</ref> | |||

| By the post-Exilic period, full monotheism had emerged: Yahweh was the sole God, not just of Israel, but of the whole world. If the nations were tools of Yahweh, then the new king who would come to redeem Israel might not be a Judean as taught in older literature (e.g. Psalm 2). Now, even a foreigner such as ] could serve as the Lord's anointed (Isaiah 44:28, 45:1). One god stood behind all the world's history.<ref name="Mark S 2001"/> | |||

| ==Biblical Israel== | |||

| The "Israel" of the Persian period included descendants of the inhabitants of the old kingdom of Judah, returnees from the Babylonian exile community, Mesopotamians who had joined them or had been exiled themselves to Samaria at a far earlier period, Samaritans and others.<ref>, p.19</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{Portal bar|Jewish|Judaism}} | |||

| <table> | |||

| {{columns-list| | |||

| <tr> | |||

| * ] | |||

| <td width="30%"> | |||

| *] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | * ] | ||

| *] | * ] | ||

| *] | * ] | ||

| *] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | * ] | ||

| *] | * ] | ||

| *] | * ] | ||

| *] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| </td> | |||

| ===Citations=== | |||

| <td width="10%"> | |||

| {{Reflist|20em}} | |||

| </td> | |||

| <td valign="top"> | |||

| <center>'''Notable people'''<br> | |||

| ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]</center> | |||

| ===Sources=== | |||

| <table> | |||

| {{refbegin|2}} | |||

| <tr> | |||