| Revision as of 00:18, 17 October 2020 editClueBot NG (talk | contribs)Bots, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers6,438,354 editsm Reverting possible vandalism by 37.47.67.179 to version by Oliszydlowski. Report False Positive? Thanks, ClueBot NG. (3799882) (Bot)Tag: Rollback← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:40, 21 December 2024 edit undoGreenC bot (talk | contribs)Bots2,547,810 edits Reformat 1 archive link. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:USURPURL and JUDI batch #20 | ||

| (666 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|City in Poland}} | ||

| {{ |

{{redirect2|Krakow|Cracow|other uses|Krakow (disambiguation)|and|Cracow (disambiguation)}} | ||

| {{Title language|pl|italic=no}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2018}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox settlement | {{Infobox settlement | ||

| | name |

| name = {{Langr|pl|Kraków}} | ||

| | |

| other_name = Cracow | ||

| | official_name = Royal Capital City of Kraków<br/>{{lower|0.1em|{{nobold|{{langx|pl|Stołeczne Królewskie Miasto Kraków}}}}}} | |||

| | image_skyline = {{Photomontage | |||

| | settlement_type = | |||

| |color=#ffffff | |||

| | image_skyline = {{multiple image | |||

| | photo1a = Krakow Rynek Glowny panorama 2.jpg | |||

| | total_width = 280 | |||

| | photo2a = XII, XIV, XIX, Kraków.jpg | |||

| | border = infobox | |||

| | photo2b = Kościół p.w. św. Piotra i Pawła, Kraków.jpg | |||

| | perrow = 1/2/2/1 | |||

| | photo3a = Wawel Krakow June 2006 003.jpg | |||

| | caption_align = center | |||

| | photo3b = Kamienica, Floriańska 55, Kraków 1.JPG | |||

| | |

| image1 = Krakow Rynek Glowny panorama 2.jpg | ||

| | alt1 = St. Mary's Basilica | |||

| | spacing = 2 | |||

| | caption1 = ] and the ] | |||

| | border = 0 | |||

| | image2 = Wawel Cathedral Front.jpg | |||

| | size = 276 | |||

| | alt2 = Wawel Cathedral | |||

| }} | |||

| | caption2 = ] | |||

| | image_caption = {{hlist|Left to right: ]|]|]|] ] within ]|]||]}} | |||

| | image3 = Kosciol Sw. Piotra i Pawla 1.JPG | |||

| | image_flag = Flag of Krakow.svg | |||

| | alt3 = Saints Peter and Paul Church | |||

| | image_shield = ] | |||

| | caption3 = ] | |||

| | map_caption = Location of Krakow in Poland | |||

| | |

| image4 = Wawel Royal Castle courtyard (SE), 4 Wawel, Old Town, Krakow, Poland.jpg | ||

| | alt4 = Wawel Castle | |||

| | pushpin_relief = 1 | |||

| | caption4 = ] | |||

| | pushpin_label_position = bottom | |||

| | image5 = 2017-05-29 Ulica Floriańska, Kraków 3.jpg | |||

| | subdivision_type = Country | |||

| | alt5 = Floriańska Street | |||

| | subdivision_name = ] | |||

| | caption5 = ] | |||

| | subdivision_type1 = ] | |||

| | image6 = Kraków Cloth Hall. View from the west. Poland.jpg | |||

| | subdivision_name1 = ] | |||

| | alt6 = Cloth Hall | |||

| | leader_title = Mayor | |||

| | caption6 = ] at ] | |||

| | leader_name = ] (]) | |||

| }} | |||

| | leader_title2 = | |||

| | |

| image_flag = Flag of Krakow.svg | ||

| | image_shield = ] | |||

| | area_total_km2 = 326.8 | |||

| | image_blank_emblem = Logo_of_Kraków.svg | |||

| | area_metro_km2 = 1023.21 | |||

| | blank_emblem_type = ] | |||

| | population_as_of = 31 December 2019 | |||

| | map_caption = Location of Kraków in Poland | |||

| | population_total = 779,115 {{increase}} (2nd)<ref>{{cite web|url=https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/dane/teryt/jednostka|title=Local Data Bank|accessdate=21 June 2020|publisher=Statistics Poland}} Data for territorial unit 1261000.</ref> | |||

| | |

| pushpin_map = Poland | ||

| | pushpin_label_position = bottom | |||

| | population_density_km2 = 2359 | |||

| | subdivision_type = ] | |||

| | population_demonym = Cracovian | |||

| | subdivision_name = {{POL}} | |||

| | established_title = City rights | |||

| | subdivision_type1 = ] | |||

| | established_date = 5 June 1257<ref>https://historykon.pl/kalendarium-historyczne/5-czerwca-1257-roku-krakow-otrzymal-prawa-miejskie</ref> | |||

| | subdivision_name1 = {{flag|Lesser Poland}} | |||

| | timezone = ] | |||

| | |

| leader_party = ] | ||

| | leader_title = ] | |||

| | timezone_DST = ] | |||

| | |

| leader_name = {{ill|Aleksander Miszalski|pl}} | ||

| | seat_type = ] | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|50|03|41|N|19|56|14|E|region:PL|display=inline,title}} | |||

| | |

| seat = ] | ||

| | government_type = ] | |||

| | postal_code_type = Postal code | |||

| | governing_body = ] | |||

| | postal_code = 30-024 to 31–962 | |||

| | |

| parts_style = coll | ||

| | |

| parts_type = ] | ||

| | |

| parts = ] | ||

| | leader_title2 = | |||

| | leader_name2 = | |||

| | area_total_km2 = 326.8 | |||

| | area_metro_km2 = 4065.11 | |||

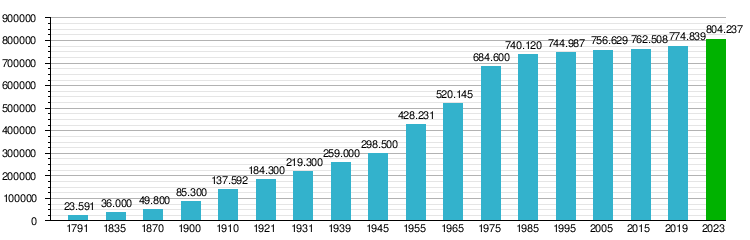

| | population_as_of = 30 June 2023 | |||

| | population_total = {{increaseNeutral}} 804,237 (])<ref name="demografia.stat.gov.pl"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230201103446/https://demografia.stat.gov.pl/BazaDemografia/Tables.aspx}} (in Polish)</ref> | |||

| | population_metro = 1,498,499 | |||

| | population_density_km2 = 2461 | |||

| | population_density_metro_km2 = auto | |||

| | population_demonym = Cracovian (]) <br/> krakowianin (male) <br/> krakowianka (female) (]) | |||

| | demographics_type1 = GDP | |||

| | demographics1_footnotes = <ref name=ec.europa.eu>{{Cite web|url=https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/met_10r_3gdp/default/table?lang=en|title=Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by metropolitan regions|website=ec.europa.eu|access-date=4 January 2024|archive-date=15 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230215185052/https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/met_10r_3gdp/default/table?lang=en|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/nama_10r_3gdp/default/table | title=Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by NUTS 3 regions | website=ec.europa.eu | access-date=4 January 2024 | archive-date=1 January 2024 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240101045308/https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/nama_10r_3gdp/default/table | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | demographics1_title1 = City | |||

| | demographics1_info1 = €18.031 billion (2020) | |||

| | demographics1_title2 = ] | |||

| | demographics1_info2 = €25.534 billion (2020) | |||

| | established_title = City rights | |||

| | established_date = 5 June 1257<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://historykon.pl/5-czerwca-1257-roku-krakow-otrzymal-prawa-miejskie/|title=5 czerwca 1257 roku Kraków otrzymał prawa miejskie » Historykon.pl|first=Jakub|last=Sikora|date=4 June 2018|access-date=5 November 2020|archive-date=11 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201111153307/https://historykon.pl/5-czerwca-1257-roku-krakow-otrzymal-prawa-miejskie/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | timezone = ] | |||

| | utc_offset = +1 | |||

| | timezone_DST = ] | |||

| | utc_offset_DST = +2 | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|50|03|41|N|19|56|14|E|region:PL|display=title,inline}} | |||

| | postal_code_type = Postal code | |||

| | postal_code = 30-024 to 31–963 | |||

| | area_code = +48 12 | |||

| | blank1_name_sec1 = ] | |||

| | blank1_info_sec1 = ] (]) | |||

| | website = {{official URL}} | |||

| | footnotes = {{designation list | embed = yes | |||

| | designation1 = WHS | | designation1 = WHS | ||

| | designation1_offname = ] | | designation1_offname = ] | ||

| | designation1_date = 1978 <small>(2nd ])</small> | | designation1_date = 1978 <small>(2nd ])</small> | ||

| | designation1_number = 29 | | designation1_number = 29 | ||

| Line 61: | Line 92: | ||

| | designation1_free1value = ] | | designation1_free1value = ] | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| | motto |

| motto = Cracovia urbs celeberrima <br/> (Kraków, the most famous city) | ||

| | elevation_min_m = 187 | |||

| | elevation_max_m = 383 | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| <!-- Do not add any foreign names to the opening paragraph! See section International Relations (bottom) for names in all equally important languages --> | <!-- Do not add any foreign names to the opening paragraph! See section International Relations (bottom) for names in all equally important languages --> | ||

| '''{{Langr|pl|Kraków}}'''{{Efn|Pronunciation: | |||

| '''Kraków''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|r|æ|k|aʊ|,_|-|k|oʊ}}, <small>also</small> {{IPAc-en|US|ˈ|k|r|eɪ|k|-|,_|ˈ|k|r|ɑː|k|aʊ}}, {{IPAc-en|UK|ˈ|k|r|æ|k|ɒ|f}},<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/cracow|title=Cracow|work=]|publisher=]|accessdate=3 June 2019}}</ref><ref> (US) and {{Cite Oxford Dictionaries|Cracow|accessdate=3 June 2019}}</ref> {{IPA-pl|ˈkrakuf|lang|Pl-Kraków.ogg}}), written in English as '''Krakow''' and traditionally known as '''Cracow''', is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in ]. On the ] in ] Province, the city dates back to the 7th century.<ref name="History"/> Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596<ref>{{Cite web |title=History of the City |url=http://warsawtour.pl/en/about-warsaw/history-of-the-city-2076.html |access-date=22 March 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180322210302/http://warsawtour.pl/en/about-warsaw/history-of-the-city-2076.html |archive-date=22 March 2018 |publisher=Oficjalny portal turystyczny m.st. Warszawy |df=dmy-all }}</ref> and has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, economic, cultural and artistic life. Cited as one of Europe's most beautiful cities,<ref> TheNews.pl.</ref> its ] was declared the first ] ] in the world. | |||

| *<small>English:</small> {{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|r|æ|k|aʊ|,_|-|oʊ}} {{respell|KRAK|ow|,_-|oh}}<ref>{{cite web |url=https://collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/cracow |title=Cracow |website=] |publisher=] |access-date=3 June 2019 |archive-date=3 June 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190603145748/https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/cracow |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| **{{IPAc-en|US|ˈ|k|r|eɪ|k|aʊ|,_|ˈ|k|r|ɑː|-}} {{respell|KRAY|kow|,_|KRAH|-}}<ref>{{cite web |url=https://lexico.com/en/definition/Cracow |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191221150906/https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/cracow |archive-date=21 December 2019 |title=Cracow |website=] |access-date=12 August 2022}}</ref> | |||

| **{{IPAc-en|UK|ˈ|k|r|æ|k|ɒ|f}} {{respell|KRAK|of}}<ref>{{cite web |url=https://lexico.com/definition/Cracow |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191221150910/https://www.lexico.com/definition/cracow |archive-date=21 December 2019 |title=Cracow |website=] UK English Dictionary |publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| *]: ''Cracovia'' | |||

| *{{langx|de|Krakau}}, {{IPA|de|ˈkʁaːkaʊ̯|pron|De-Krakau.ogg}} | |||

| *{{langx|uk|Краків|Krakiv}}, {{IPA|uk|krɐkiu̯|pron|Uk-Krakow.flac}} | |||

| }} ({{IPA-pl|ˈkrakuf|lang|Pl-Kraków.ogg}}), also spelled as '''Cracow''' or '''Krakow''',<ref>{{cite web |last1=Harper |first1=Douglas R. |title=Krakow |url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/Krakow |website=]}}</ref> is the ] and one of the oldest cities in ]. Situated on the ] in ], the city has a population of 804,237 (2023), with approximately 8 million additional people living within a {{convert|100|km|0|abbr=on}} radius.<ref name="welcome"/> Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596,<ref>{{cite book |last=Davies |first=Norman |date=2023 |title=Boże igrzysko. Historia Polski |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TJp-AwAAQBAJ&dq=krakowa+warszawy+1596+roku&pg=PT298 |location=Kraków |publisher=Znak |isbn=978-83-240-8836-2 |access-date=9 March 2023 |archive-date=5 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230405014905/https://books.google.com/books?id=TJp-AwAAQBAJ&dq=krakowa+warszawy+1596+roku&pg=PT298 |url-status=live }}</ref> and has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, cultural, and artistic life. Cited as one of ]'s most beautiful cities,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thenews.pl/1/12/Artykul/118486,Krakow-makes-top-ten-in-Conde-Nast-Traveler-poll |title=Kraków makes top ten in Conde Nast Traveler poll |date=15 November 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140310074729/http://www.thenews.pl/1/12/Artykul/118486,Krakow-makes-top-ten-in-Conde-Nast-Traveler-poll |archive-date=10 March 2014 |url-status=live |website=TheNews.pl}}</ref> its ] was declared a ] in 1978, one of the world's first sites granted the status. | |||

| The city began as a ] on Wawel Hill and was a busy trading centre of ] in 985.<ref name="History"/> In 1038, it became the seat of ] from the ], and subsequently served as the centre of administration under ] and of the ] until the late 16th century, when ] transferred his royal court to ]. With the emergence of the ] in 1918, Kraków reaffirmed its role as the nucleus of a national spirit. After the ], at the start of ], the newly defined {{Lang|de|]}} became the seat of ]'s ]. The Jewish population was forced into the ], a walled zone from where they were sent to Nazi ]s such as the nearby ], and ] like ].<ref name=ARC>{{cite web |title=Plaszow Forced Labour Camp |url=http://www.deathcamps.org/occupation/plaszow.html |year=2005 |website=ARC |access-date=14 November 2014 |archive-date=29 April 2004 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040429123214/http://www.deathcamps.org/occupation/plaszow.html |url-status=live }}</ref> However, the city was spared from destruction. In 1978, ], ], was elevated to the ] as Pope John Paul, the first non-Italian pope in 455 years.<ref name="Clark"/> | |||

| The city has grown from a ] settlement to Poland's second-most-important city. It began as a hamlet on ] and was reported as a busy trading centre of Central Europe in 965.<ref name="History"/> With the establishment of new universities and cultural venues at the emergence of the ] in 1918 and throughout the 20th century, Kraków reaffirmed its role as a major national academic and artistic centre. The city has a population of about 780,000, with approximately 8 million additional people living within a {{convert|100|km|0|abbr=on}} radius of its ].<ref name="welcome"/> | |||

| The Old Town and historic centre of Kraków, along with the nearby ], are Poland's first ]s.<ref name="Centre">{{cite web|url=https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/29|title=Historic Centre of Kraków|publisher=UNESCO World Heritage Centre|website=whc.unesco.org|access-date=26 December 2019|archive-date=10 June 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230610071815/https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/29|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="unesco-02com"/> Its extensive cultural and architectural legacy across the epochs of ], ], and ] includes ] and ] on the banks of the Vistula, ], ], and the largest ] market square in Europe, {{lang|pl|]}}.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/poland/articles/poland-fascinating-facts/ |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220111/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/poland/articles/poland-fascinating-facts/ |archive-date=11 January 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live|title=10 amazing things you probably didn't know about Poland|newspaper=The Telegraph|access-date=13 November 2016}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Kraków is home to ], one of the ] and often considered Poland's most reputable academic institution of higher learning. The city also hosts a number of institutions of national significance, including the ], ], ], ], and the ]. | |||

| After the ] by Nazi Germany at the start of ], the newly defined ] (Kraków District) became the capital of Germany's ]. The Jewish population of the city was forced into a walled zone known as the ], from which they were sent to German ]s such as the nearby ], and the ] like ].<ref name=ARC>{{cite web |title=Plaszow Forced Labour Camp |url=http://www.deathcamps.org/occupation/plaszow.html |year=2005 |website=ARC |accessdate=14 November 2014}}</ref> However, the city was spared from destruction and major bombing. | |||

| Kraków is classified as a ] with the ranking of "high sufficiency" by the ].<ref>{{cite web |title=The World According to GaWC 2020 |url=https://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2020t.html |website=GaWC – Research Network |publisher=Globalization and World Cities |access-date=31 August 2020 |archive-date=24 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200824031341/https://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2020t.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The city is served by ], the country's second busiest airport and the most important international airport for the inhabitants of south-eastern Poland. In 2000, Kraków was named ]. In 2013, Kraków was officially approved as a ].<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/nov/14/krakow-unesco-city-of-literatre |title=Kraków's story: a Unesco City of Literature built out of books |work=The Guardian |date=14 November 2013 |access-date=26 November 2016 |archive-date=14 October 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161014155319/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/nov/14/krakow-unesco-city-of-literatre |url-status=live }}</ref> The city hosted ] in 2016,<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/27759/krakow-to-host-next-world-youth-day |title=Krakow to host next World Youth Day |newspaper=Catholic News Agency (CNA) |date=28 July 2013 |access-date=4 January 2015 |archive-date=11 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201111162342/https://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/krakow-to-host-next-world-youth-day |url-status=live }}</ref> and the ] in 2023.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.european-games.org/pl/key-facts-figures-european-games-krakow-malopolska-2023/ |title=Key facts & figures: European Games Kraków-Malopolska 2023 |website=european-games.org |date=19 June 2023 |access-date=13 July 2023 |archive-date=13 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230713184243/https://www.european-games.org/pl/key-facts-figures-european-games-krakow-malopolska-2023/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 1978, Karol Wojtyła, ], was elevated to the ] as ]—the first non-Italian pope in 455 years.<ref name="Clark"/> Also that year, ] approved ] as its first ] alongside ].<ref name="Centre">{{cite web|url=https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/29|title=Historic Centre of Kraków|first=UNESCO World Heritage|last=Centre|website=whc.unesco.org}}</ref><ref name="unesco-02com"/> Kraków is classified as a ] with the ranking of "high sufficiency" by the ].<ref>{{cite web |title=The World According to GaWC 2020 |url=https://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2020t.html |website=GaWC - Research Network |publisher=Globalization and World Cities |accessdate=31 August 2020}}</ref> Its extensive cultural heritage across the epochs of ], ] and ] includes the ] and the ] on the banks of the ], the ], ] and the largest ] market square in Europe, the ].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/poland/articles/poland-fascinating-facts/|title=10 amazing things you probably didn't know about Poland|newspaper=The Telegraph|access-date=13 November 2016}}</ref> Kraków is home to ], one of the ] and traditionally Poland's most reputable institution of higher learning. | |||

| In 2000, Kraków was named ]. In 2013, Kraków was officially approved as a ].<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/nov/14/krakow-unesco-city-of-literatre |title=Kraków's story: a Unesco City of Literature built out of books |date=14 November 2013 |access-date=26 November 2016}}</ref> The city hosted the ] in July 2016.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/krakow-to-host-next-world-youth-day/ |title=Krakow to host next World Youth Day |newspaper=Catholic News Agency (CNA) |date=28 July 2013 |access-date=4 January 2015}}</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| The name of Kraków is traditionally derived from ] (Krak, Grakch), the legendary founder of Kraków and a ruler of the tribe of ]. In Polish, {{lang|pl|Kraków}} is an archaic ] form of ''Krak'' and essentially means "Krak's (town)". |

The name of Kraków is traditionally derived from ] (Krak, Grakch), the legendary founder of Kraków and a ruler of the tribe of ].<ref name="Nungovitch1">{{cite book |last=Nungovitch |first=Petro Andreas |date=2019 |title=Here All Is Poland: A Pantheonic History of Wawel, 1787–2010 |location=Lanham |publisher=Lexington Books |pages=55, 287 |isbn=978-1-4985-6913-2}}</ref> In Polish, {{lang|pl|Kraków}} is an ] ] form of ''Krak'' and essentially means "Krak's (town)".<ref name="Małecki"/> The true origin of the name is highly disputed among historians, with many theories in existence and no unanimous consensus.<ref name="Nungovitch1"/> The first recorded mention of Prince Krakus (then written as ''Grakch'') dates back to 1190, although the town existed as early as the seventh century, when it was inhabited by the tribe of Vistulans.<ref name="History"/> It is possible that the name of the city is derived from the word {{wikt-lang|pl|kruk}}, meaning 'crow' or 'raven'.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.krakow.pl/kultura/73601,artykul,krakowskie_abc.html#:~:text=Istnieje+kilka+koncepcji+wyja%C5%9Bniaj%C4%85cych+pochodzenie,od+imienia+legendarnego+ksi%C4%99cia+Kraka|title=Krakowskie ABC - Magiczny Kraków|website=www.krakow.pl|access-date=20 July 2021|archive-date=24 January 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230124051953/https://www.krakow.pl/kultura/73601,artykul,krakowskie_abc.html#:~:text=Istnieje+kilka+koncepcji+wyja%C5%9Bniaj%C4%85cych+pochodzenie,od+imienia+legendarnego+ksi%C4%99cia+Kraka|url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| The city's full official name is {{lang|pl|Stołeczne Królewskie Miasto Kraków}},<ref name="bip.krakow-UCHWAŁA"/> which can be translated as "] of Kraków". In English, a person born or living in Kraków is a Cracovian ({{ |

The city's full official name is {{lang|pl|Stołeczne Królewskie Miasto Kraków}},<ref name="bip.krakow-UCHWAŁA"/> which can be translated as "] of Kraków". In English, a person born or living in Kraków is a Cracovian ({{langx|pl|krakowianin}} or {{lang|pl|krakus}}).<ref name="Tyrmand">{{cite book |last=Tyrmand |first=Leopold |date=2014 |title=Diary 1954 |location=Evanston |publisher=Northwestern University Press |page=xi |isbn=978-0-8101-6749-0}}</ref> Until the 1990s the English version of the name was often written as Cracow, but now the most widespread modern English version is Krakow.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170829161714/http://krakow.wyborcza.pl/krakow/1,44425,4824554.html?disableRedirects=true |date=29 August 2017 }}. Rafał Romanowski. Gazeta Wyborcza, 9 January 2008</ref> | ||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{Main|History |

{{Main|History of Kraków}} | ||

| {{For timeline}} | |||

| ] at ]. Kraków was the capital of Poland from 1038 to 1596]] | |||

| ===Origins and middle ages=== | |||

| Kraków's ] begins with evidence of a Stone Age settlement on the present site of the Wawel Hill.<ref name="Wawel Kraków"/> A legend attributes Kraków's founding to the mythical ruler ], who built it above a cave occupied by a ], ]. The first written record of the city's name dates back to 965, when Kraków was described as a notable commercial centre controlled first by Moravia (876–879), but captured by a Bohemian duke ] in 955.<ref name="krakow.pl-2"/> The first acclaimed ruler of Poland, ], took Kraków from the Bohemians and incorporated it into the holdings of the ] towards the end of his reign. | |||

| ] ] dates back to the 11th century, when ] made Kraków his royal residence and the capital of the ].]] | |||

| Kraków's ] begins with evidence of a ] settlement on the present site of the ].<ref name="Fischinger">{{cite book |first1=Andrzej |last1=Fischinger |first2=Jerzy |last2=Banach |first3=Janusz |last3=Smólski |date=1991 |title=Cracow: History, Art, Renovation |publisher=The Citizen's Committee for the Restoration of Cracow's Historical Monuments |page=11 |oclc=749994485}}</ref> A legend attributes Kraków's founding to the mythical ruler ], who built it above a cave occupied by a ], ]. The first written record of the city's name dates back to 965, when Kraków was described as a notable commercial centre controlled first by Moravia (876–879), but captured by a Bohemian duke ] in 955.<ref name="krakow.pl-2"/> The first acclaimed ruler of Poland, ], took Kraków from the Bohemians and incorporated it into the holdings of the ] towards the end of his reign.<ref name="Živković">{{cite book |first1=Tibor |last1=Živković |first2=Dejan |last2=Crnčević |first3=Dejan |last3=Bulić |date=2013 |title=The World of the Slavs |location=Belgrade |publisher=The Institute of History |page=310 |isbn=978-86-7743-104-4}}</ref> | |||

| In 1038, Kraków became the seat of the Polish government.<ref name="History"/> By the end of the 10th century, the city was a leading centre of trade.<ref name="Van Dongen"/> Brick buildings were constructed, including the Royal ] with St. Felix and Adaukt Rotunda, ] churches such as ], ], and ].<ref name="Rosik - Urbańczyk"/> The city was sacked and burned during the ] of 1241.<ref>J.J. Saunders, ''The History of the Mongol Conquests'', (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1971), 85.</ref> It was rebuilt practically identical,<ref name="Akt lokacyjny">Polska Agencja Prasowa. Nauka w Polsce (June 2007), See also: , translated from Latin by Bożena Wyrozumska {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130508131151/http://wiadomosci.gazeta.pl/kraj/1%2C34309%2C4193098.html |date=8 May 2013 }} Retrieved 21 December 2012.</ref> based on new location act and ] in 1257 by the high duke ] who following the example of ], introduced city rights modelled on the ] allowing for tax benefits and new trade privileges for the citizens.<ref name="Strzala2"/> In 1259, the city was again ravaged by the Mongols. A third attack in 1287 was repelled thanks in part to the ].<ref name="Kolodziejczyk"/> In 1335, King ] (Kazimierz in Polish) declared the two western suburbs to be a new city named after him, ] (''Casimiria'' in Latin). The defensive walls were erected around the central section of Kazimierz in 1362, and a plot was set aside for the ] order next to ].<ref name="Świszczowski"/> | |||

| In 1038, Kraków became the seat of the Polish government.<ref name="History"/> By the end of the tenth century, the city was a leading centre of trade.<ref name="Van Dongen"/> Brick buildings were constructed, including the Royal ] with St. Felix and Adaukt Rotunda, ] churches such as ], ], and ].<ref name="Rosik - Urbańczyk"/> ] during the ] of 1241.<ref>J.J. Saunders, ''The History of the Mongol Conquests'', (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1971), 85.</ref> It was rebuilt practically identically,<ref name="Akt lokacyjny">Polska Agencja Prasowa. Nauka w Polsce (June 2007), See also: {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230128062513/http://www.konflikty.pl/a,1707,Sredniowiecze,Akt_lokacji_Krakowa.html |date=28 January 2023 }}, translated from Latin by Bożena Wyrozumska {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130508131151/http://wiadomosci.gazeta.pl/kraj/1%2C34309%2C4193098.html |date=8 May 2013 }} Retrieved 21 December 2012.</ref> based on new location act and ] in 1257 by the high duke ] who following the example of ], introduced city rights modelled on the ] allowing for tax benefits and new trade privileges for the citizens.<ref name="Strzala2"/> In 1259, the city was ] by the Mongols. A ] in 1287 was repelled thanks in part to the ].<ref name="Kolodziejczyk"/> In 1315 a large alliance of Poland, Denmark, ] and ] was formed in Kraków.<ref>{{cite web|title=Wydarzenia z kalendarza historycznego: 27 czerwca 1315|url=http://www.chronologia.pl/wydarzenie-w13150627ppk00.html|access-date=22 August 2024|website=chronologia.pl|language=pl}}</ref> | |||

| ] is one of the oldest churches in the city dating from the 11th-century]] | |||

| ], 1493]] | |||

| The city rose to prominence in 1364, when Casimir III of Poland founded the ],<ref name="The establishment of a university"/> the second oldest university in central Europe after the Charles University in Prague. King Casimir also began work on a campus for the Academy in Kazimierz, but he died in 1370 and the campus was never completed. The city continued to grow under the joint ]-Polish ]. As the capital of the ] and a member of the ], the city attracted many craftsmen, businesses, and ]s as science and the arts began to flourish.<ref name="poloniahans"/> The royal chancery and the University ensured a first flourishing of Polish literary culture in the city.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Sobecki|first1=Sebastian|title=Cracow|journal=Europe: A Literary History, 1348–1418, Ed. David Wallace|date=2016|pages=551–65|url=https://global.oup.com/academic/product/europe-9780198735359?cc=nl&lang=en&|isbn=9780198735359|publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> | |||

| In 1335, King ] ({{langx|pl|Kazimierz}}) declared the two western suburbs to be a new city named after him, ] ({{langx|la|Casimiria}}). The defensive walls were erected around the central section of Kazimierz in 1362, and a plot was set aside for the ] order next to ].<ref name="Świszczowski" /> The city rose to prominence in 1364, when Casimir founded the ],<ref name="The establishment of a university" /> the second oldest university in central Europe after the ]. | |||

| The city continued to grow under the ]. As the capital of the ] and a member of the ], the city attracted many craftsmen from abroad,<ref>{{cite book|title=God's Playground A History of Poland Volume 1: The Origins to 1795|first=Norman|last=Davies|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2005|pages=65}}</ref> businesses, and ]s as science and the arts began to flourish.<ref name="poloniahans"/> The royal chancery and the university ensured a first flourishing of Polish literary culture in the city.<ref>{{cite book|last=Sobecki|first=Sebastian|title=Cracow, Europe: A Literary History, 1348–1418, ed. David Wallace|date=2016|pages=551–65|url=https://global.oup.com/academic/product/europe-9780198735359?cc=nl&lang=en&|isbn=978-0-19-873535-9|publisher=Oxford University Press|access-date=2 June 2016|archive-date=20 December 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161220183041/https://global.oup.com/academic/product/europe-9780198735359?cc=nl&lang=en&}}</ref> | |||

| ===Kraków's "Golden Age"=== | |||

| ], 1493]] | |||

| The 15th and 16th centuries were known as Poland's ''Złoty Wiek'' or ].<ref name="NormanDavies"/> Many works of ] art and architecture were created,<ref name="Mikos"/><ref name="unescoancient"/> including ancient synagogues in Kraków's Jewish quarter located in the north-eastern part of Kazimierz, such as the ].<ref name="infosyn"/> During the reign of ], various artists came to work and live in Kraków, and ] established a ] in the city<ref name="Haller"/> after ] had printed the ], the first work printed in Poland, in 1473.<ref name="Norman Davies, God's Playground, vol.1, chapter 5"/><ref name="Wieslaw Wydra 88"/> | |||

| ===Early modern period=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The 15th and 16th centuries were known as Poland's {{lang|pl|Złoty Wiek}} or ].<ref name="NormanDavies"/> Many works of ] art and architecture were created,<ref name="Mikos"/><ref name="unescoancient"/> including ancient synagogues in Kraków's Jewish quarter located in the north-eastern part of Kazimierz, such as the ].<ref name="infosyn"/> During the reign of ], various artists came to work and live in Kraków, and ] established a ] in the city<ref name="Haller"/> after ] had printed the ], the first work printed in Poland, in 1473.<ref name="Norman Davies, God's Playground, vol.1, chapter 5"/><ref name="Wieslaw Wydra 88"/> | |||

| In 1520, the most famous ] in Poland, named |

In 1520, the most famous ] in Poland, named {{lang|pl|]}} after ], was cast by Hans Behem.<ref name="dzwon"/> At that time, ], a younger brother of artist and thinker ], was Sigismund's ].<ref name="HansDur"/> ] made ]s for several churches.<ref name="Kulmbach"/> In 1553, the Kazimierz district council gave the Jewish ] (council of a Jewish self-governing community) a licence for the right to build their own interior walls across the western section of the already existing defensive walls. The walls were expanded again in 1608 due to the growth of the community and influx of Jews from Bohemia.<ref name="Kazimierz.com"/> In 1572, King ], the last of the Jagiellons, died childless. The Polish throne passed to ] and then to other foreign-based rulers in rapid succession, causing a decline in the city's importance. Furthermore, in 1596, ] of the ] moved the administrative capital of the ] from Kraków to ].<ref name="warsaw-capital-1596"/> The city was destabilised by pillaging in the 1650s during the ], especially during the ].<ref name="Milewski2">{{cite web |first=Dariusz |last=Milewski |date=8 June 2007 |title=Szwedzi w Krakowie |url=http://wiadomosci.onet.pl/kiosk/historia/szwedzi-w-krakowie,1,3338904,wiadomosc.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110518220019/http://wiadomosci.onet.pl/kiosk/historia/szwedzi-w-krakowie,1,3338904,wiadomosc.html |archive-date=18 May 2011 |access-date=10 April 2015 |work=Internet Archive |publisher=] |language=pl}}</ref> Later in 1707, the city underwent an outbreak of ] that left 20,000 of the city's residents dead.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Frandsen |first=Karl-Erik |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F3bNWrVRMb8C |title=The Last Plague in the Baltic Region 1709-1713 |date=2010 |publisher=Museum Tusculanum Press |isbn=978-87-635-0770-7 |pages=20 |language=en}}</ref> | ||

| {{wide image|View of Kraków near the end of the 16th century.jpg|900px|View of Kraków (''Cracovia'') near the end of the 16th century|100%|center}} | |||

| ===19th century=== | ===19th century=== | ||

| ] |

] taking the ] in Kraków's market square (''Rynek''), 1794]] | ||

| Already weakened during the 18th century, by the mid-1790s the ] had twice been ] by its neighbors: ], the ] and ].<ref name="The Polish struggle for freedom"/> In 1791, the Holy Roman Emperor ] changed the status of Kazimierz as a separate city and made it into a district of Kraków. The richer Jewish families began to move out. However, because of the injunction against travel on the ], most Jewish families stayed relatively close to the historic synagogues. In 1794, ] initiated an unsuccessful ] in ] which, in spite of his victorious ] against a numerically superior ], resulted in the ]. As a result, Kraków fell under Habsburg rule.<ref name="GR"/> | |||

| In 1802, German became the town's official language. Of the members appointed by the Habsburgs to the municipal council only half were Polish.<ref name=Franaszek>{{Cite web |last=Franaszek |first=Piotr |title=Economic effects of Cracow's frontier between 1772 and 1867 |url=https://shron2.chtyvo.org.ua/Zbirnyk_statei/Die_galizische_Grenze_1772-1867_Kommunikation_oder_Isolation7_nim.pdf |access-date=31 March 2023 |archive-date=31 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230531114948/https://shron2.chtyvo.org.ua/Zbirnyk_statei/Die_galizische_Grenze_1772-1867_Kommunikation_oder_Isolation7_nim.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> From 1796 to 1809, the population of the city rose from 22,000 to 26,000 with an increasing percentage of nobles and officials.<ref name=Franaszek/> In 1809, ] captured former Polish territories from Austria and made the town part of the ].<ref name=Franaszek/> During the time of the Duchy of Warsaw, requirements to upkeep the Polish army followed by tours of Austrian, Polish and Russian troops, plus Russian occupation and a flood in the year 1813 all added up to the adverse development of the city with a high debt burden on public finances and many workshops and trading houses needing to close their activities.<ref name=Franaszek/> | |||

| ]. After the ], Kraków became a city-state and remained the only piece of sovereign Polish territory between 1815 and 1846.]] | |||

| Following Napoleon's defeat, the 1815 ] restored the pre-war boundaries but also created the partially independent and neutral ].<ref name=Franaszek/> In addition to the historic city of Kraków itself, the Free City included the towns of ], ] and ] and 224 villages. Outside the city, mining and metallurgy started developing. The population of Kraków itself grew in this time from 23,000 to 43,000; that of the overall republic from 88,000 to 103,000. The population of the city had an increasing number of ] clergy, officials and intelligentsia with which the rich townspeople sympathised. They were opposed to the conservative ] who also were drawn more and more to the city real estates even though their income still mainly came from their agricultural possessions in the Republic, the Kingdom of Poland and Galicia. The percentage of the Jewish population in the city also increased in this time from 20.8% to 30.4%. However, nationalist sentiment and other political issues led to instability; this culminated in the ] of 1846, which was crushed by the Austrian authorities.<ref name="Frommer"/> The Free City was therefore annexed into the Austrian Empire as the ] ({{langx|pl|Wielkie Księstwo Krakowskie}}, {{langx|de|Großherzogtum Krakau}}), which was legally separate from but administratively part of the ] (more simply Austrian Galicia).<ref name="Chambers's encyclopaedia: a... - Google Books"/> | |||

| During the era of the free city, a ] led to positive economic development. But because of the unstable political situation and insecurity about the future, not much of the accumulated wealth was invested.<ref name=Franaszek/> Through the increase of taxes, customs and regulations, prices soared and the city fell into a recession. From 1844 to 1850 the population was diminished by over 4,000 inhabitants.<ref name=Franaszek/> | |||

| In 1866, Austria granted a degree of autonomy to ] after its own defeat in the ].<ref name="(''see: Franz Joseph I granted Kraków the municipal government'')"/> Politically freer Kraków became a Polish national symbol and a centre of culture and art, known frequently as the "Polish Athens" (''{{lang|pl|Polskie Ateny}}''). Many leading Polish artists of the period resided in Kraków,<ref name="google"/> among them the seminal painter ],<ref name="Matejko"/> laid to rest at ], and the founder of modern Polish drama, ].<ref name="culture"/> ] Kraków evolved into a modern metropolis; ] and electric ] were introduced in 1901, and between 1910 and 1915, Kraków and its surrounding suburban communities were gradually combined into a single administrative unit called Greater Kraków (''{{lang|pl|Wielki Kraków}}'').<ref name="Becoming Metropolitan: Urban Selfhood and the Making of Modern Krakow"/><ref name="Kalendarium"/> | |||

| In 1866, Austria granted a degree of autonomy to Galicia after its own defeat in the ].<ref name="(''see: Franz Joseph I granted Kraków the municipal government'')"/> Kraków, being politically freer than the Polish cities under Prussian (later German) and Russian rule, became a Polish national symbol and a centre of culture and art, known frequently as the "Polish Athens" ({{lang|pl|Polskie Ateny}}). Many leading Polish artists of the period resided in Kraków,<ref name="google"/> among them the seminal painter ],<ref name="Matejko"/> laid to rest at ], and the founder of modern Polish drama, ].<ref name="culture"/> ] Kraków evolved into a modern metropolis; ] and electric ] were introduced in 1901, and between 1910 and 1915, Kraków and its surrounding suburban communities were gradually combined into a single administrative unit called Greater Kraków ({{lang|pl|Wielki Kraków}}).<ref name="Becoming Metropolitan: Urban Selfhood and the Making of Modern Krakow"/><ref name="Kalendarium"/> | |||

| ]. After the ], Kraków was independent city republic and the only piece of sovereign Polish territory between 1815 and 1846.]] | |||

| At the outbreak of ] on 3 August 1914, ] formed a small ] ], the ]—the predecessor of the ]—which set out from Kraków to fight for the liberation of Poland.<ref name="Urb 171-172"/> The city was briefly besieged by Russian troops in November 1914.<ref name="twierdza"/> Austrian rule in Kraków ended in 1918 when the ] assumed power.<ref name="Eastern Europe: an introduction to... - Google Books"/><ref name="Encyclopedia of Rusyn history and... - Google Books"/> | At the outbreak of ] on 3 August 1914, ] formed a small ] ], the ]—the predecessor of the ]—which set out from Kraków to fight for the liberation of Poland.<ref name="Urb 171-172"/> The city was briefly besieged by Russian troops in November 1914.<ref name="twierdza"/> Austrian rule in Kraków ended in 1918 when the ] assumed power.<ref name="Eastern Europe: an introduction to... - Google Books"/><ref name="Encyclopedia of Rusyn history and... - Google Books"/> | ||

| ===20th century to the present=== | ===20th century to the present=== | ||

| ] | ]—the first autochrome in Poland, dated 1912]] | ||

| Following the emergence of the ] in 1918, Kraków resumed its role as a major Polish academic and cultural centre, with the establishment of new universities such as the ] and the ], as well as several new and essential vocational schools. The city became an important cultural centre for ], including both ] and ] groups.<ref>{{cite web |title= Kraków after 1795 |url= http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Krakow/Krakow_after_1795 |publisher= YIVO |access-date= 13 November 2018 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20181113161327/http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Krakow/Krakow_after_1795|archive-date= 13 November 2018}}</ref><ref name="Krakow old scenes, including historical photographs"/><ref>{{Cite web|date=17 February 2021|title=Kazimierz na przedwojennych zdjęciach. "Ruch na ulicach panował niebywały"|url=https://krowoderska.pl/kazimierz-na-przedwojennych-zdjeciach-ruch-na-ulicach-panowal-niebywaly/|access-date=6 August 2021|website=Krowoderska.pl|language=pl-PL|archive-date=14 August 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210814164403/https://krowoderska.pl/kazimierz-na-przedwojennych-zdjeciach-ruch-na-ulicach-panowal-niebywaly/|url-status=live}}</ref> Kraków was also an influential centre of Jewish spiritual life, with all its manifestations of religious observance—from ] to ] and ]—flourishing side by side.<ref name="Sinnreich">{{cite book |last=Sinnreich |first=Helene J. |date=2023 |title=The Atrocity of Hunger. Starvation in the Warsaw, Lodz, and Krakow Ghettos During World War II |location=Cambridge |publisher=University Press |page=9 |isbn=978-1-009-11767-8}}</ref> | |||

| Following the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany in September 1939, the city of Kraków became part of the ], a separate administrative region of the |

Following the ] by ] in September 1939, the city of Kraków became part of the ], a separate administrative region of the Third Reich. On 26 October 1939, the Nazi régime set up {{lang|de|]}}, one of four districts within the General Government. On the same day, the city of Kraków became the capital of the administration.<ref>{{Cite web |date=11 February 2021 |title=Niemiecka okupacja w Krakowie na zdjęciach |url=https://krowoderska.pl/niemiecka-okupacja-w-krakowie-na-zdjeciach/ |access-date=24 April 2022 |website=Krowoderska.pl |language=pl-PL |archive-date=6 February 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230206065228/https://krowoderska.pl/niemiecka-okupacja-w-krakowie-na-zdjeciach/ |url-status=live }}</ref> The General Government was ruled by Governor-General ], who was based in the city's Wawel Castle. The Nazis envisioned turning Kraków into a completely Germanised city; after removal of all Jews and Poles, renaming of locations and streets into the German language, and sponsorship of propaganda portraying the city as historically German.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tygodnik.com.pl/dodatek-ks/04/sabor.html |title=Cztery miasta w jednym – nowa historia wojennego Krakowa Niechciana "stolica" |trans-title=Four cities in one – a new history of wartime Krakow. The unwanted "capital" |language=pl |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230206065229/http://www.tygodnik.com.pl/dodatek-ks/04/sabor.html |archive-date=6 February 2023 |url-status=dead |first=Agnieszka |last=Sabor |work=Tygodnik Powszechny No. 4 (2794) |date=26 January 2003}}</ref> On 28 November 1939, Frank set up {{lang|de|]}} ('Jewish Councils') to be run by Jewish citizens for the purpose of carrying out orders for the Nazis. These orders included the registration of all Jewish people living in each area, the collection of taxes, and the formation of ] groups. The Polish ] maintained a parallel underground administrative system.<ref>{{cite book |last=Williamson |first=David G. |author-link=David G. Williamson |title=The Polish Underground 1939–1947 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SSPOAwAAQBAJ |series=Campaign chronicles |date=12 April 2012 |location=Barnsley, Yorkshire |publisher=Pen and Sword |publication-date=2012 |isbn=978-1-84884-281-6 |access-date=17 July 2022 |archive-date=18 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231018205548/https://books.google.com/books?id=SSPOAwAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> | ||

| At the outbreak of ], some 56,000 Jews resided in Kraków—almost one-quarter of a total population of about 250,000; by November 1939, the Jewish population of the city had grown to approximately 70,000.<ref name=USHMM-Holocaust-Encyclopedia-Krakow/><ref name=USHMM-Ghettos-Encyclopedia-VolII/> According to German statistics from 1940, over 200,000 Jews lived within the entire Kraków District, comprising more than 5 percent of the district's total population. However, these statistics probably underestimate the situation.<ref name=USHMM-Ghettos-Encyclopedia-VolII/> In November 1939, during an operation known as {{lang|de|]}} ('special operation Kraków'), the Germans arrested more than 180 university professors and academics, and sent them to the ] and ] ], though the survivors were later released on the request of prominent Italians.<ref name="16B. Eastern Europe in World War II: October 1939 – May 1945."/><ref name="sonderaktion"/> | |||

| ], 1942—a German checkpoint during {{lang|de|]}}]] | |||

| During an operation called "{{lang|de|]}}", more than 180 university professors and academics were arrested and sent to ] and ] ], though the survivors were later released on the request of prominent Italians.<ref name="16B. Eastern Europe in World War II: October 1939 – May 1945."/><ref name="sonderaktion"/> | |||

| Before the formation of ], which began in the Kraków District in December 1939, Jews were encouraged to flee the city. For those who remained, the German authorities decided in March 1941 to allocate a then-suburban neighborhood, ], to become Kraków's ghetto, where many Jews subsequently died of illness or starvation. Initially, most ghettos were open and Jews were allowed to enter and exit freely, but as security became tighter the ghettos were generally closed. From autumn 1941, the ] developed the policy of ],{{sfn|Longerich|2010| p=171}} which further worsened the already bleak conditions for Jews. The inhabitants of the ] were later murdered or sent to German ]s, including ] and ], and to ].<ref name="The-Kraków_Ghetto_1940-1943"/> The largest deportations within the Distrikt occurred from June to September 1942. More specifically, mass deportation from Kraków's ghetto occurred in the first week of June 1942,<ref name=USHMM-Ghettos-Encyclopedia-VolII/> and the ghetto was finally liquidated in March 1943.{{sfn|Longerich|2010| p=376}} | |||

| ], 1942—a German checkpoint during operation ''{{lang|de|]}}'']] | |||

| The film director ] survived the Kraków Ghetto. ] selected employees from the ghetto to work in his enamelware factory {{lang|de|]}}, saving them from the camps.<ref name="All for Love - Google Books"/><ref name="Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account... - Google Books"/> Similarly, many men capable of physical labor were saved from deportation to extermination camps and instead sent to labor camps across the General Government.<ref name=USHMM-Ghettos-Encyclopedia-VolII/> By September 1943, the last of the Jews from the Kraków Ghetto had been deported. Although ], Kraków remained relatively undamaged at the end of World War II,<ref name="LukZaw"/> with most of the city's historical and architectural legacy spared. Soviet forces under the command of Marshal ] entered the city on 18 January 1945, and began arresting Poles loyal to the ] or those who had served in the Home Army.<ref>Gilbert, M (1989) Second World War, Weidenfeld & Nicolson P646.</ref> | |||

| Before the formation of ghettos, which began in the District in December 1939, Jews were encouraged to flee the city. For those who remained the German authorities decided in March 1941 to allocate a then suburban neighborhood, ], to become Kraków's ghetto where so many Jews were destined to die of illness or starvation. Initially, most ghettos were open and Jews were allowed to enter and exit freely. However, with time ghettos were generally closed and security became tighter. From autumn 1941, the ] developed the policy of ],{{sfn|Longerich|2010| p=171}} which further worsened the already bleak Jewish condition.The ghetto inhabitants were later murdered or sent to German ]s, including ] and ], and to ].<ref name="The-Kraków_Ghetto_1940-1943"/> The largest deportations within the District occurred from June to September 1942. More specifically, the Kraków ghetto deportation occurred in the first week of June 1942,<ref name=USHMM-Ghettos-Encyclopedia-VolII/> and in March 1943 the ghetto was definitely liquidated.{{sfn|Longerich|2010| p=376}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ], the film director, is a survivor of the Kraków Ghetto, while ] selected employees from the ghetto to work in his ], ''{{lang|de|Deutsche Emailwaren Fabrik}}'' (''{{lang|de|Emalia}}'' for short) saving them from the camps.<ref name="All for Love - Google Books"/><ref name="Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account... - Google Books"/> Similarly, many men capable of physical labor were saved from the deportations to extermination camps and instead set to labor camps across the General Government.<ref name=USHMM-Ghettos-Encyclopedia-VolII/> | |||

| By September 1943, the last of the Jews from the Kraków ghetto were deported. Although ], Kraków remained relatively undamaged at the end of World War II,<ref name="LukZaw"/> sparing most of the city's historical and architectural legacy. Soviet forces entered the city on 18 January 1945, and began arresting Poles loyal to the ] or those who had served in the ].<ref>Gilbert, M (1989) Second World War, Weidenfeld & Nicolson P646</ref> | |||

| After the war, under the ] (officially declared in 1952), the intellectual and academic community of Kraków came under complete political control. The universities were soon deprived of their printing rights and autonomy.<ref name="autonomy"/> The ] government of Poland ordered the construction of the country's largest ] in the newly created suburb of ].<ref name="krakow_history"/> The creation of the giant Lenin Steelworks (now ] owned by ]) sealed Kraków's transformation from a university city into an industrial centre.<ref name="communist era"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| In an effort that spanned two decades, ], the cardinal archbishop of Kraków from 1964 to 1978, successfully lobbied for permission to build the first churches in the newly industrialized suburbs.<ref name="communist era"/><ref name="NH-anthology"/> In 1978, the Catholic Church elevated Wojtyła to the ] as ], the first non-Italian pope in over 450 years. In the same year, ], following the application of local authorities, placed Kraków Old Town on the first list of ]s.<ref name="Woodward">{{cite book |first1=Simon C. |last1=Woodward |first2=Louise |last2=Cooke |date=2022 |title=World Heritage. Concepts, Management and Conservation |location=London |publisher=Routledge, Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-1-000-77729-1}}</ref> | |||

| After the war, under the ], the intellectual and academic community of Kraków was put under complete political control. The universities were soon deprived of printing rights and autonomy.<ref name="autonomy"/> The ] government ordered the construction of the country's largest ] in the newly created suburb of ].<ref name="krakow_history"/> The creation of the giant Lenin Steelworks (now ] Steelworks owned by ]) sealed Kraków's transformation from a university city, into an industrial centre.<ref name="communist era"/> The new working-class, drawn by the industrialization of Kraków, contributed to rapid population growth. | |||

| In an effort that spanned two decades, ], cardinal archbishop of Kraków, successfully lobbied for permission to build the first churches in the newly industrial suburbs.<ref name="communist era"/><ref name="NH-anthology"/> In 1978, Wojtyła was elevated to the ] as ], the first non-Italian pope in 455 years. In the same year, ] placed Kraków Old Town on the first-ever list of ]s. | |||

| ==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

| ] in |

] with the ] ] in the distance]] | ||

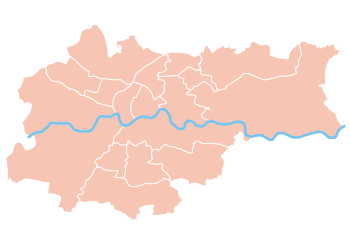

| Kraków lies in the southern part of Poland, on the ], approximately {{convert|219|m|ft|abbr=on}} ].<ref name="SiT">{{cite book |last1=Bujak |first1=Adam |last2=Rożek |first2=Michał |date=1989 |title=Kraków |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Cd_NAAAAMAAJ&q=krakow%20219%20morza |publisher=Sport i Turystyka |page=22 |isbn=978-83-217-2787-5 |language=pl |access-date=27 March 2024 |archive-date=27 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240327172416/https://books.google.com/books?id=Cd_NAAAAMAAJ&q=krakow%20219%20morza |url-status=live }}</ref> The city is located on the border between different ]s: the ] in the north-western parts of the city, the ] in the north-east, the ] (east) and the ] of the ] (south).<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Traczyk |first1=Paulina |last2=Gruszecka-Kosowska |first2=Agnieszka |date=2020-08-20 |title=The Condition of Air Pollution in Kraków, Poland, in 2005–2020, with Health Risk Assessment |journal=International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health |language=en |volume=17 |issue=17 |pages=6063 |doi=10.3390/ijerph17176063 |doi-access=free |issn=1660-4601 |pmc=7503758 |pmid=32825405}}</ref> | |||

| Kraków lies in the southern part of Poland, on the ], in a valley at the foot of the ], {{convert|219|m|ft|abbr=on}} ]; halfway between the ] ({{lang-pl|Jura Krakowsko-Częstochowska}}) to the north, and the ] {{convert|100|km|mi|abbr=on}} to the south, constituting the natural border with ] and the ]; {{convert|230|km|0|abbr=on}} west from the border with ]. | |||

| There are five ]s in Kraków, with a combined area of ca. {{convert|48.6|ha|acre|abbr=off}}. Due to their ecological value, these areas are legally protected. The western part of the city, along its northern and north-western side, borders an area of international significance known as the Jurassic ]-] refuge. The main motives for the protection of this area include plant and animal wildlife and the area's ] features and landscape.<ref name="Pattern of karst landscape of the Cracow Upland (South Poland)"/> Another part of the city is located within the ecological 'corridor' of the Vistula River valley. This corridor is also assessed as being of international significance as part of the Pan-European ecological network.<ref name="The forms of nature protection within the city limits"/> |

There are five ]s in Kraków, with a combined area of ca. {{convert|48.6|ha|acre|abbr=off}}.<ref name="ZZM">{{cite web |url=https://zzm.krakow.pl/przyroda.html |title=Przyroda |date=2016 |website=zzm.krakow.pl |publisher=Zarząd Zieleni Miejskiej w Krakowie |access-date=23 February 2024 |language=pl |archive-date=23 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240223211011/https://zzm.krakow.pl/przyroda.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Due to their ecological value, these areas are legally protected.<ref name="ZZM"/> The western part of the city, along its northern and north-western side, borders an area of international significance known as the Jurassic ]-] refuge.<ref name="ZZM"/> The main motives for the protection of this area include plant and animal wildlife and the area's ] features and landscape.<ref name="Pattern of karst landscape of the Cracow Upland (South Poland)"/> Another part of the city is located within the ecological 'corridor' of the Vistula River valley. This corridor is also assessed as being of international significance as part of the Pan-European ecological network.<ref name="The forms of nature protection within the city limits"/> | ||

| ===Climate=== | ===Climate=== | ||

| ] during the summer season]] | ] during the summer season]] | ||

| Kraków has a ], denoted by ] as ''Dfb'', somewhat boardering on an ] (''Cfb''); with climate change winters are rapidly becoming milder, and hot summers days above 30C are increasingly common,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.weatherbase.com/weather/weather-summary.php3?s=66521&cityname=Krakow%2C+Lesser+Poland+Voivodeship%2C+Poland&units=metric|title=Krakow, Poland|website=weatherbase.com|access-date=20 July 2020|archive-date=9 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230209140214/https://www.weatherbase.com/weather/weather-summary.php3?s=66521&cityname=Krakow,+Lesser+Poland+Voivodeship,+Poland&units=metric|url-status=live}}</ref> but with winter temperatures on average still below freezing, it is perhaps best defined as having a semicontinental climate.<ref name="Warsaw">{{Cite web|url=http://www.warsaw.climatemps.com/vs/krakow.php|title=Warsaw vs Krakow Climate & Distance Between|website=www.warsaw.climatemps.com|access-date=10 March 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200524071827/http://www.warsaw.climatemps.com/vs/krakow.php|archive-date=24 May 2020}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.introducingkrakow.com/climate|title=Kraków Weather Averages – Climate and temperatures|website=www.introducingkrakow.com|access-date=10 March 2019|archive-date=9 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230209140213/https://www.introducingkrakow.com/climate|url-status=live}}</ref> In older reference periods it was classified as a ] (''Dfb'').<ref>{{Cite web|last1=Peel|first1=M. C.|last2=Finlayson|first2=B. L.|last3=McMahon|first3=T. A.|title=Climate map of Europe (from the "Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification").|date=12 October 2007|url=https://commons.wikimedia.org/File:Europe_K%C3%B6ppen_Map.png|access-date=10 March 2019|archive-date=11 May 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220511170134/https://commons.wikimedia.org/File:Europe_K%C3%B6ppen_Map.png|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=az3qCAAAQBAJ&q=KR%C3%81KOW+K%C3%96PPEN+CFB&pg=PA28|title=Selected climatic data for a global set of standard stations for vegetation science|last=Muller|first=M. J.|date=6 December 2012|publisher=Springer Science & Business Media|isbn=978-94-009-8040-2|language=en|access-date=14 November 2020|archive-date=18 October 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231018205612/https://books.google.com/books?id=az3qCAAAQBAJ&q=KR%C3%81KOW+K%C3%96PPEN+CFB&pg=PA28#v=onepage&q=KR%C3%81KOW%20K%C3%96PPEN%20CFB&f=false|url-status=live}}</ref> By classification of ], it has a ] in the centre of ] with the "fusion" of different features.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.vividmaps.com/2015/05/climates-classification-by-wincenty.html|title=Climates classification by Wincenty Okołowicz|last=Egoshin|first=Alex|date=10 May 2015|website=Vivid Maps|language=en-US|access-date=10 March 2019|archive-date=22 March 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190322142951/https://www.vividmaps.com/2015/05/climates-classification-by-wincenty.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Due to its geographic location, the city may be under marine influence, sometimes ] influence, but without direct influence, giving the city variable meteorological conditions over short spaces of time.<ref>{{Cite journal| |

Due to its geographic location, the city may be under marine influence, sometimes ] influence, but without direct influence, giving the city variable meteorological conditions over short spaces of time.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Twardosz|first1=Robert|last2=Niedźwiedź|first2=Tadeusz|last3=Łupikasza|first3=Ewa|date=1 May 2011|title=The influence of atmospheric circulation on the type of precipitation (Kraków, southern Poland)|journal=Theoretical and Applied Climatology|language=en|volume=104|issue=1|pages=233–250|doi=10.1007/s00704-010-0340-5|issn=1434-4483|bibcode=2011ThApC.104..233T|doi-access=free|hdl=20.500.12128/10463|hdl-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Poland|title=Poland - Climate|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en|access-date=10 March 2019|archive-date=2 May 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150502183748/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/466681/Poland/28238/Languages|url-status=live}}</ref> The city lies in proximity to the ] and there are often occurrences of a ] called ], causing temperatures to rise rapidly.<ref name="SEDNO">{{cite book |first1=Magdalena |last1=Kuchcik |first2=Krzysztof |last2=Błażejczyk |first3=Jakub |last3=Szmyd |first4=Paweł |last4=Milewski |first5=Anna |last5=Błażejczyk |first6=Jarosław |last6=Baranowski |date=2013 |title=Potencjał leczniczy klimatu Polski |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0phhBAAAQBAJ |location=Warszawa (Warsaw) |publisher=Wydawnictwo SEDNO |page=64 |isbn=978-83-7963-001-1 |language=pl |access-date=27 March 2024 |archive-date=27 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240327172414/https://books.google.com/books?id=0phhBAAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> In relation to Warsaw, temperatures are very similar for most of the year, except that in the colder months ] has a larger daily temperature range, more moderate winds, generally more rainy days and with greater chances of clear skies on average, especially in winter. The higher sun angle also allows for a longer ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://weatherspark.com/compare/y/85104~87583/Comparison-of-the-Average-Weather-in-Krak%C3%B3w-and-Warsaw|title=The Typical Weather Anywhere on Earth – Weather Spark|website=weatherspark.com|access-date=10 March 2019|archive-date=9 February 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230209140213/https://weatherspark.com/compare/y/85104~87583/Comparison-of-the-Average-Weather-in-Krak%C3%B3w-and-Warsaw|url-status=live}}</ref> In addition, for older data there was less sun than the capital of the country, about 30 minutes daily per year, but both have small differences in relative humidity and the direction of the winds is northeast.<ref name="Warsaw" /> | ||

| The climate table below presents weather data with averages from 1991 to 2020, sunshine ranges from 1971 to 2000, and valid extremes from 1951 to the present day: | |||

| Being towards ] and a relatively considerable distance from the sea, Krakow has significant temperature differences according to the progress of different ]es, having four defined seasons of the year. Average temperatures in summer range from {{convert|18.6|to|20.4|C|F|0}} and in winter from {{convert|-0.6|to|0.8|C|F|0}}. The average annual temperature is {{convert|10.0|C|F|0}}. In summer temperatures often exceed {{convert|25|C|F|0}}, even reaching {{convert|30|C|F|0}}, while in winter temperatures drop to {{convert|-5|C|F|0}} at night and about {{convert|0|C|F|0}} during the day. During very cold nights the temperature can drop to {{convert|-15|C|F|0}}. The city lies near the ], there are often occurrences of ] blowing (a ]), causing temperatures to rise rapidly, and even in winter reach up to {{convert|20|C|F|0}}.{{Citation needed|date=January 2019}} | |||

| {{Weather box|location = Kraków-Airport (]), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present | |||

| | collapsed = | |||

| In relation to ], temperatures are very similar for most of the year, except that in the colder months ] has a larger daily temperature range, more moderate winds, generally more rainy days and with greater chances of clear skies on average, especially in winter. The lower sun angle also allows for a larger ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://weatherspark.com/compare/y/85104~87583/Comparison-of-the-Average-Weather-in-Krak%C3%B3w-and-Warsaw|title=The Typical Weather Anywhere on Earth - Weather Spark|website=weatherspark.com|access-date=2019-03-10}}</ref> In addition, for older data there was less sun than the capital of the country, about 30 minutes daily per year, but both have small differences in relative humidity and the direction of the winds is northeast.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| | metric first = y | |||

| | single line = y | |||

| The climate table below presents weather data from the years 2000–2012 although the official Köppen reference period was from 1981–2010 (therefore not being technically a ]<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://library.wmo.int/index.php?lvl=notice_display&id=20130#.XIWVbyhKiM8|title=WMO Guidelines on the Calculation of Climate Normals|last=Group|first=PMB|date=|website=library.wmo.int|access-date=2019-03-10}}</ref>). According to ongoing measurements, the temperature has increased during these years as compared with the last series. This increase averages about 0.6 °C over all months. Warming is most pronounced during the winter months, with an increase of more than 1.0 °C in January. | |||

| | Jan record high C = 16.6 | |||

| {{Kraków weatherbox}} | |||

| | Feb record high C = 19.8 | |||

| | Mar record high C = 24.1 | |||

| | Apr record high C = 30.0 | |||

| | May record high C = 32.6 | |||

| | Jun record high C = 34.2 | |||

| | Jul record high C = 35.7 | |||

| | Aug record high C = 37.3 | |||

| | Sep record high C = 34.8 | |||

| | Oct record high C = 27.1 | |||

| | Nov record high C = 22.5 | |||

| | Dec record high C = 19.3 | |||

| | year record high C = 37.3 | |||

| | Jan avg record high C = 10.0 | |||

| | Feb avg record high C = 12.3 | |||

| | Mar avg record high C = 18.0 | |||

| | Apr avg record high C = 24.3 | |||

| | May avg record high C = 27.9 | |||

| | Jun avg record high C = 31.1 | |||

| | Jul avg record high C = 32.5 | |||

| | Aug avg record high C = 32.2 | |||

| | Sep avg record high C = 27.6 | |||

| | Oct avg record high C = 23.4 | |||

| | Nov avg record high C = 17.3 | |||

| | Dec avg record high C = 10.9 | |||

| | year avg record high C = 33.8 | |||

| | Jan high C = 1.6 | |||

| | Feb high C = 3.7 | |||

| | Mar high C = 8.4 | |||

| | Apr high C = 15.1 | |||

| | May high C = 19.8 | |||

| | Jun high C = 23.2 | |||

| | Jul high C = 25.3 | |||

| | Aug high C = 25.0 | |||

| | Sep high C = 19.5 | |||

| | Oct high C = 14.0 | |||

| | Nov high C = 7.6 | |||

| | Dec high C = 2.7 | |||

| | year high C = 13.8 | |||

| | Jan mean C = -1.6 | |||

| | Feb mean C = -0.2 | |||

| | Mar mean C = 3.5 | |||

| | Apr mean C = 9.3 | |||

| | May mean C = 14.0 | |||

| | Jun mean C = 17.6 | |||

| | Jul mean C = 19.3 | |||

| | Aug mean C = 18.9 | |||

| | Sep mean C = 13.9 | |||

| | Oct mean C = 8.8 | |||

| | Nov mean C = 3.8 | |||

| | Dec mean C = -0.5 | |||

| | year mean C = 8.9 | |||

| | Jan low C = -4.7 | |||

| | Feb low C = -3.7 | |||

| | Mar low C = -0.8 | |||

| | Apr low C = 3.7 | |||

| | May low C = 8.5 | |||

| | Jun low C = 12.2 | |||

| | Jul low C = 13.8 | |||

| | Aug low C = 13.4 | |||

| | Sep low C = 9.2 | |||

| | Oct low C = 4.7 | |||

| | Nov low C = 0.6 | |||

| | Dec low C = -3.4 | |||

| | year low C = 4.5 | |||

| | Jan avg record low C = -15.7 | |||

| | Feb avg record low C = -13.0 | |||

| | Mar avg record low C = -8.0 | |||

| | Apr avg record low C = -3.0 | |||

| | May avg record low C = 1.9 | |||

| | Jun avg record low C = 6.6 | |||

| | Jul avg record low C = 8.3 | |||

| | Aug avg record low C = 7.7 | |||

| | Sep avg record low C = 2.8 | |||

| | Oct avg record low C = -3.2 | |||

| | Nov avg record low C = -7.3 | |||

| | Dec avg record low C = -13.5 | |||

| | year avg record low C = -18.0 | |||

| | Jan record low C = -29.9 | |||

| | Feb record low C = -29.5 | |||

| | Mar record low C = -26.7 | |||

| | Apr record low C = -7.5 | |||

| | May record low C = -3.2 | |||

| | Jun record low C = -0.1 | |||

| | Jul record low C = 5.4 | |||

| | Aug record low C = 2.7 | |||

| | Sep record low C = -3.1 | |||

| | Oct record low C = -7.4 | |||

| | Nov record low C = -17.2 | |||

| | Dec record low C = -29.5 | |||

| | year record low C = -29.9 | |||

| | precipitation colour = green | |||

| | Jan precipitation mm = 37.9 | |||

| | Feb precipitation mm = 32.3 | |||

| | Mar precipitation mm = 38.1 | |||

| | Apr precipitation mm = 46.4 | |||

| | May precipitation mm = 79.0 | |||

| | Jun precipitation mm = 77.0 | |||

| | Jul precipitation mm = 98.2 | |||

| | Aug precipitation mm = 72.5 | |||

| | Sep precipitation mm = 65.8 | |||

| | Oct precipitation mm = 51.2 | |||

| | Nov precipitation mm = 41.4 | |||

| | Dec precipitation mm = 33.4 | |||

| | year precipitation mm = 673.0 | |||

| | Jan snow depth cm = 7.6 | |||

| | Feb snow depth cm = 6.5 | |||

| | Mar snow depth cm = 2.7 | |||

| | Apr snow depth cm = 0.9 | |||

| | May snow depth cm = 0.0 | |||

| | Jun snow depth cm = 0.0 | |||

| | Jul snow depth cm = 0.0 | |||

| | Aug snow depth cm = 0.0 | |||

| | Sep snow depth cm = 0.0 | |||

| | Oct snow depth cm = 0.3 | |||

| | Nov snow depth cm = 2.7 | |||

| | Dec snow depth cm = 4.1 | |||

| | year snow depth cm = | |||

| | unit precipitation days = 0.1 mm | |||

| | Jan precipitation days = 16.93 | |||

| | Feb precipitation days = 15.71 | |||

| | Mar precipitation days = 15.00 | |||

| | Apr precipitation days = 12.87 | |||

| | May precipitation days = 14.97 | |||

| | Jun precipitation days = 13.37 | |||

| | Jul precipitation days = 15.00 | |||

| | Aug precipitation days = 12.00 | |||

| | Sep precipitation days = 12.07 | |||

| | Oct precipitation days = 13.40 | |||

| | Nov precipitation days = 14.67 | |||

| | Dec precipitation days = 15.77 | |||

| | year precipitation days = 171.74 | |||

| | unit snow days = 0 cm | |||

| | Jan snow days = 17.9 | |||

| | Feb snow days = 14.1 | |||

| | Mar snow days = 5.5 | |||

| | Apr snow days = 0.8 | |||

| | May snow days = 0.0 | |||

| | Jun snow days = 0.0 | |||

| | Jul snow days = 0.0 | |||

| | Aug snow days = 0.0 | |||

| | Sep snow days = 0.0 | |||

| | Oct snow days = 0.3 | |||

| | Nov snow days = 4.3 | |||

| | Dec snow days = 11.9 | |||

| | year snow days = 54.8 | |||

| | Jan humidity = 85.8 | |||

| | Feb humidity = 82.5 | |||

| | Mar humidity = 76.3 | |||

| | Apr humidity = 69.9 | |||

| | May humidity = 72.0 | |||

| | Jun humidity = 72.7 | |||

| | Jul humidity = 73.2 | |||

| | Aug humidity = 74.5 | |||

| | Sep humidity = 80.2 | |||

| | Oct humidity = 83.8 | |||

| | Nov humidity = 87.7 | |||

| | Dec humidity = 87.5 | |||

| | year humidity = 78.8 | |||

| | Jan sun = 43.3 | |||

| | Feb sun = 63.2 | |||

| | Mar sun = 100.5 | |||

| | Apr sun = 136.9 | |||

| | May sun = 200.8 | |||

| | Jun sun = 193.5 | |||

| | Jul sun = 210.5 | |||

| | Aug sun = 200.7 | |||

| | Sep sun = 125.4 | |||

| | Oct sun = 97.7 | |||

| | Nov sun = 48.8 | |||

| | Dec sun = 32.1 | |||

| | year sun = | |||

| | source 1 = Institute of Meteorology and Water Management<ref name=IMGWtavg>{{cite web | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20211203115527/https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/TSR_AVE | |||

| | archive-date = 3 December 2021 | |||

| | url = https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/TSR_AVE | |||

| | title = Średnia dobowa temperatura powietrza | |||

| | work = Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 | |||

| | publisher = Institute of Meteorology and Water Management | |||

| | language = pl | |||

| | access-date = 20 January 2022 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref><ref name=IMGWtmin>{{cite web | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220115043924/https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/TMIN_AVE | |||

| | archive-date = 15 January 2022 | |||

| | url = https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/TMIN_AVE | |||

| | title = Średnia minimalna temperatura powietrza | |||

| | work = Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 | |||

| | publisher = Institute of Meteorology and Water Management | |||

| | language = pl | |||

| | access-date = 20 January 2022 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref><ref name=IMGWtmax>{{cite web | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220115044916/https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/TMAX_AVE | |||

| | archive-date = 15 January 2022 | |||

| | url = https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/TMAX_AVE | |||

| | title = Średnia maksymalna temperatura powietrza | |||

| | work = Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 | |||

| | publisher = Institute of Meteorology and Water Management | |||

| | language = pl | |||

| | access-date = 20 January 2022 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref><ref name=IMGWprecip>{{cite web | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220109045820/https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/OPAD_SUMA | |||

| | archive-date = 9 January 2022 | |||

| | url = https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/OPAD_SUMA | |||

| | title = Miesięczna suma opadu | |||

| | work = Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 | |||

| | publisher = Institute of Meteorology and Water Management | |||

| | language = pl | |||

| | access-date = 20 January 2022 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref><ref name=IMGWprecipdays>{{cite web | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220115051112/https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/OPAD_01 | |||

| | archive-date = 15 January 2022 | |||

| | url = https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/OPAD_01 | |||

| | title = Liczba dni z opadem >= 0,1 mm | |||

| | work = Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 | |||

| | publisher = Institute of Meteorology and Water Management | |||

| | language = pl | |||

| | access-date = 20 January 2022 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref><ref name=IMGWsnowdepth>{{cite web | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220115054936/https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/SNIEG_SR_GRUB | |||

| | archive-date = 15 January 2022 | |||

| | url = https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/SNIEG_SR_GRUB | |||

| | title = Średnia grubość pokrywy śnieżnej | |||

| | work = Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 | |||

| | publisher = Institute of Meteorology and Water Management | |||

| | language = pl | |||

| | access-date = 20 January 2022 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref><ref name=IMGWsnowdays>{{cite web | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220121044246/https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/SNIEG_0 | |||

| | archive-date = 21 January 2022 | |||

| | url = https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/SNIEG_0 | |||

| | title = Liczba dni z pokrywą śnieżna > 0 cm | |||

| | work = Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 | |||

| | publisher = Institute of Meteorology and Water Management | |||

| | language = pl | |||

| | access-date = 20 January 2022 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref><ref name=IMGWsun>{{cite web | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220115055331/https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/USL | |||

| | archive-date = 15 January 2022 | |||

| | url = https://klimat.imgw.pl/pl/climate-normals/USL | |||

| | title = Średnia suma usłonecznienia (h) | |||

| | work = Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 | |||

| | publisher = Institute of Meteorology and Water Management | |||

| | language = pl | |||

| | access-date = 20 January 2022 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| |source 2 = Meteomodel.pl (records, relative humidity 1991–2020, sunshine 1971–2000)<ref name=recordhigh1>{{cite web | |||

| | url = https://meteomodel.pl/dane/srednie-miesieczne/?imgwid=350190560&par=tmax&max_empty=3 | |||

| | title = Kraków-Balice Absolutna temperatura maksymalna | |||

| | date = 6 April 2018 | |||

| | publisher = Meteomodel.pl | |||

| | language = pl | |||

| | access-date = 20 January 2022 | |||

| | archive-date = 13 February 2023 | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230213123807/https://meteomodel.pl/dane/srednie-miesieczne/?imgwid=350190560&par=tmax&max_empty=3 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref><ref name=recordlow1>{{cite web | |||

| | url = https://meteomodel.pl/dane/srednie-miesieczne/?imgwid=350190566&par=tmax&max_empty=3 | |||

| | title = Kraków-Balice Absolutna temperatura minimalna | |||

| | date = 6 April 2018 | |||

| | publisher = Meteomodel.pl | |||

| | language = pl | |||

| | access-date = 20 January 2022 | |||

| | archive-date = 9 February 2023 | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230209140332/https://meteomodel.pl/dane/srednie-miesieczne/?imgwid=350190566&par=tmax&max_empty=3 | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref><ref name=relativehumidity1>{{cite web | |||

| | url = https://meteomodel.pl/dane/srednie-miesieczne/?imgwid=350190566&par=rh&max_empty=3 | |||

| | title = Kraków-Balice Średnia wilgotność | |||

| | date = 6 April 2018 | |||

| | publisher = Meteomodel.pl | |||

| | language = pl | |||

| | access-date = 20 January 2022 | |||