| Revision as of 15:43, 6 December 2013 editSuhayb.Manzer (talk | contribs)29 edits →Kushan Empire: important info relating to art and culture of Kushan Empire← Previous edit | Revision as of 13:04, 23 December 2024 edit undoEltabar243 (talk | contribs)67 edits →Zutt RebellionTag: content sourced to vanity pressNext edit → | ||

| (990 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| {{History of Pakistan}} | |||

| {{about|the pre-1947 history of Pakistan|post-1946 history|History of Pakistan (1947–present)}} | |||

| {{Use Pakistani English|date=April 2020}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2019}} | |||

| {{History of Pakistan}} | |||

| {{Culture of Pakistan}} | {{Culture of Pakistan}} | ||

| {{History of South Asia}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The '''history of Pakistan''' ({{lang-ur|{{Nastaliq|تاريخ پاكِستان }}}}) encompasses the history of the region constituting modern ]. Prior to ] in 1947, the land that is now Pakistan was ruled in different periods by local kings and numerous imperial powers. The ancient history of the region comprising present-day Pakistan also includes some of the oldest empires of ]<ref name="coppa">{{cite journal |last=Coppa|first=A.|coauthors=L. Bondioli, A. Cucina, D. W. Frayer, C. Jarrige, J. F. Jarrige, G. Quivron, M. Rossi, M. Vidale, R. Macchiarelli|title=Palaeontology: Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry|journal=Nature|volume=440|pages=755–756|date=6 April 2006 |url=http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v440/n7085/pdf/440755a.pdf|doi=10.1038/440755a |accessdate=2007-11-22 |format=PDF |pmid=16598247 |issue=7085}}</ref> and some of its major civilizations.<ref name="possehl">{{cite journal|last=Possehl|first=G. L.|authorlink=Gregory Possehl|year=1990|month=October|title=Revolution in the Urban Revolution: The Emergence of Indus Urbanization|journal=Annual Review of Anthropology|volume=19|issue=1|pages=261–282|doi=10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.001401|url=http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/toc/anthro/19/1?cookieSet=1|accessdate=2007-05-06}}</ref><ref name="asaw">{{cite book|last=Kenoyer|first=Jonathan Mark|coauthors=Kimberley Heuston|title=The Ancient South Asian World|publisher=]|month=May |year=2005 |isbn=978-0-19-517422-9 |url=http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/HistoryWorld/Ancient/Other/~~/dmlldz11c2EmY2k9OTc4MDE5NTE3NDIyOQ==}}</ref><ref name="shef">{{cite web |url=http://www.shef.ac.uk/archaeology/research/pakistan |title=Palaeolithic and Pleistocene of Pakistan|publisher=Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield|accessdate=2007-12-01}}</ref><ref name="murray">{{cite book|last=Murray |first=Tim |authorlink=Tim Murray (archaeologist)|title=Time and archaeology |publisher=Routledge|year=1999 |location=London; New York |page=84|url=http://books.google.com/?id=k3z9iXo_Uq8C&pg=PP3&dq=%22Time+and+Archaeology%22|isbn=978-0-415-11762-3}}</ref> By the 18th century the land was incorporated into ]. Pakistan's political history began with the birth of the ] in 1906 to protect "Muslim interests, amid neglect and under-representation" and to oppose Congress and growing Indian nationalism in return the ] would decide to grant local self-rule. On 29 December 1930, philosopher ] called for an autonomous new state in "northwestern India for Indian Muslims".<ref name="aips"/> The League rose to popularity in the late 1930s. ] espoused the '']'' and led the League to adopt the '']''<ref name="resolution"/> of 1940, demanding the formation of independent states in the East and the West of British India. Eventually, a ] led by ] gained independence from the ], on ]. | |||

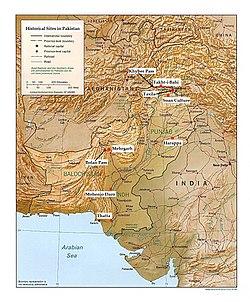

| The '''History of Pakistan''' prior to its ] in 1947 spans several ] and covers a vast geographical area known as the Greater Indus region.<ref>{{Cite book |last=McIntosh |first=Jane |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F6iBAAAAMAAJ&q=Greater+Indus+Valley |title=The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives |date=2008 |publisher=Bloomsbury Academic |isbn=978-1-57607-907-2 |language=en}}</ref> ] modern humans arrived in what is now Pakistan between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=James |first1=Hannah V. A. |last2=Petraglia |first2=Michael D. |date=2005 |title=Modern Human Origins and the Evolution of Behavior in the Later Pleistocene Record of South Asia |url=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/444365 |journal=Current Anthropology |language=en |volume=46 |issue=S5 |pages=S3–S27 |doi=10.1086/444365 |hdl=11858/00-001M-0000-002B-0DBC-F |issn=0011-3204|hdl-access=free }}</ref> ], dating as far back as 2.1 million years, have been discovered in the ] of northern Pakistan, indicating early ] activity in the region.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Dennell |first1=R.W. |last2=Rendell |first2=H. |last3=Hailwood |first3=E. |date=1988 |title=Early tool-making in Asia: two-million-year-old artefacts in Pakistan |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0003598X00073555/type/journal_article |journal=Antiquity |language=en |volume=62 |issue=234 |pages=98–106 |doi=10.1017/S0003598X00073555 |issn=0003-598X}}</ref> The earliest known human remains in Pakistan are dated between 5000 BCE and 3000 BCE.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Oldest human remains found in Pakistan |url=https://www.rockartmuseum.com/oldest-human-remains-pakistan/#:~:text=At%20present%2C%20the%20oldest%20human,5000%20BCE%20to%203000%20BCE. |website=Rock Art Museum}}</ref> By around 7000 BCE, early human settlements began to emerge in Pakistan, leading to the development of urban centres such as ], one of the oldest in human history.<ref name="Mehrgarh">Hirst, K. Kris. 2005. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170118071157/http://archaeology.about.com/od/mterms/g/mehrgarh.htm|date=18 January 2017}}. '' Guide to Archaeology''</ref><ref name="whc.unesco.org2">UNESCO World Heritage. 2004. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181226013816/http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/1876/|date=26 December 2018}}. ''Archaeological Site of Mehrgarh''</ref> By 4500 BCE, the ] evolved, which flourished between 2500 BCE and 1900 BCE along the ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Asrar |first=Shakeeb |title=How British India was divided |url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/8/14/how-india-pakistan-and-bangladesh-were-formed |access-date=2024-05-01 |website=Al Jazeera |language=en}}</ref> The region that now constitutes ] served both as the ] of a major ancient civilization and as a strategic gateway connecting ] with ] and the ].<ref name="Srinivasan2007">{{citation|last=Neelis|first=Jason|editor=Srinivasan, Doris |title=On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kuṣāṇa World|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dCz8NczNbcMC&pg=PA55|year=2007|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-90-04-15451-3|pages=55–94|chapter=Passages to India: Śaka and Kuṣāṇa migrations in historical contexts}} Quote: "Numerous passageways through the northwestern frontiers of the Indian subcontinent in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan served as migration routes to South Asia from the Iranian plateau and the Central Asian steppes. Prehistoric and protohistoric exchanges across the ], ], and Himalaya ranges demonstrate earlier precedents for routes through the high mountain passes and river valleys in later historical periods. Typological similarities between Northern Neolithic sites in Kashmir and Swat and sites in the Tibetan plateau and northern China show that 'Mountain chains have often integrated rather than isolated peoples.' Ties between the trading post of ] in ] (northeastern Afghanistan) and the lower ] provide evidence for long-distance commercial networks and 'polymorphous relations' across the Hindu Kush until c. 1800 B.C.' The ] (BMAC) may have functioned as a 'filter' for the introduction of ] to the northwestern Indian subcontinent, although routes and chronologies remain hypothetical. (page 55)"</ref><ref name="Marshall2013">{{citation|last=Marshall|first=John|title=A Guide to Taxila|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JEMbH2aDO0UC&pg=PA1|year=2013|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-61544-1|pages=1–|orig-date=1960}} Quote: "Here also, in ancient days, was the meeting-place of three great trade-routes, one, from Hindustan and Eastern India, which was to become the `royal highway' described by ] as running from ] to the north-west of the ]; the second from Western Asia through ], ] and ] and so across the Indus at ] to Taxila; and the third from Kashmir and Central Asia by way of the ] valley and ] to ] and so down the ] valley. These three trade-routes, which carried the bulk of the traffic passing by land between India and Central and Western Asia, played an all-important part in the history of Taxila. (page 1)"</ref> | |||

| Situated on the first coastal migration route of '']'' out of Africa, the region was inhabited early by modern humans.<ref name="QamarAyub2002">{{cite journal|last1=Qamar|first1=Raheel|last2=Ayub|first2=Qasim|last3=Mohyuddin|first3=Aisha|last4=Helgason|first4=Agnar|last5=Mazhar|first5=Kehkashan|last6=Mansoor|first6=Atika|last7=Zerjal|first7=Tatiana|last8=Tyler-Smith|first8=Chris|last9=Mehdi|first9=S. Qasim|title=Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in Pakistan|journal=The American Journal of Human Genetics|volume=70|issue=5|year=2002|pages=1107–1124|issn=0002-9297|doi=10.1086/339929|pmid=11898125|pmc=447589}}</ref><ref name="DennellPorr2014">{{citation|last=Clarkson|first=Christopher |editor=Dennell, Robin |editor2=Porr, Martin |title=Southern Asia, Australia and the Search for Human Origins|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DuWfAgAAQBAJ|year=2014|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-01785-6|pages=76–89|chapter=East of Eden: Founder Effects and Archaeological Signature of Modern Human Dispersal}} Quote: "The record from South Asia (Pakistan, India and Sri Lanka) has been pivotal in discussions of the archaeological signature of early modern humans east of Africa because of the well-excavated and well-dated sites that have recently been reported in this region and because of the central role South Asia played in early population expansion and dispersals to the east. Genetic studies have revealed that India was the gateway to subsequent colonisation of Asia and Australia and saw the first major population expansion of modern human populations anywhere outside of Africa. South Asia therefore provides a crucial stepping-scone in early modern migration to Southeast Asia and Oceania. (pages 81–2)"</ref> The 9,000-year history of village life in South Asia traces back to the ] (7000–4300 ]) site of Mehrgarh in Pakistan,<ref name=coningham-young-1>{{Citation | last1 =Coningham | first1 =Robin |author1-link=Robin Coningham | last2 =Young | first2 =Ruth | year =2015 | title =The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE – 200 CE | publisher =Cambridge University Press}} Quote: ""Mehrgarh remains one of the key sites in South Asia because it has provided the earliest known undisputed evidence for farming and pastoral communities in the region, and its plant and animal material provide clear evidence for the ongoing manipulation, and domestication, of certain species. Perhaps most importantly in a South Asian context, the role played by zebu makes this a distinctive, localised development, with a character completely different to other parts of the world. Finally, the longevity of the site, and its articulation with the neighbouring site of Nausharo (c. 2800—2000 BCE), provides a very clear continuity from South Asia's first farming villages to the emergence of its first cities (Jarrige, 1984)."</ref><ref name=fisher1>{{citation|last=Fisher|first=Michael H.|title=An Environmental History of India: From Earliest Times to the Twenty-First Century|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kZVuDwAAQBAJ|year=2018|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-11162-2}} Quote: "page 33: "The earliest discovered instance in India of well-established, settled agricultural society is at Mehrgarh in the hills between the Bolan Pass and the Indus plain (today in Pakistan) (see Map 3.1). From as early as 7000 BCE, communities there started investing increased labor in preparing the land and selecting, planting, tending, and harvesting particular grain-producing plants. They also domesticated animals, including sheep, goats, pigs, and oxen (both humped zebu and unhumped ). Castrating oxen, for instance, turned them from mainly meat sources into domesticated draft-animals as well."</ref><ref name=dyson1>{{citation|last=Dyson|first=Tim|title=A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3TRtDwAAQBAJ|year=2018|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-882905-8}}, Quote: "(p 29) "The subcontinent's people were hunter-gatherers for many millennia. There were very few of them. Indeed, 10,000 years ago there may only have been a couple of hundred thousand people, living in small, often isolated groups, the descendants of various 'modern' human incomers. Then, perhaps linked to events in Mesopotamia, about 8,500 years ago agriculture emerged in Baluchistan."</ref> and the 5,000-year history of urban life in South Asia to the various sites of the ], including ] and ].<ref name="AllchinAllchin1982">{{citation|last1=Allchin|first1=Bridget|last2=Allchin|first2=Raymond|title=The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r4s-YsP6vcIC&pg=PA131|year=1982|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-28550-6|page=131}}Quote: "During the second half of the fourth and early part of the third millennium B.C., a new development begins to become apparent in the greater Indus system, which we can now see to be a formative stage underlying the Mature Indus of the middle and late third millennium. This development seems to have involved the whole Indus system, and to a lesser extent the Indo-Iranian borderlands to its west, but largely left untouched the subcontinent east of the Indus system. (page 81)"</ref><ref name="DalesKenoyer1986">{{citation|last1=Dales|first1=George|last2=Kenoyer|first2=Jonathan Mark|last3=Alcock|first3=Leslie|title=Excavations at Mohenjo Daro, Pakistan: The Pottery, with an Account of the Pottery from the 1950 Excavations of Sir Mortimer Wheeler|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4iew_THp8foC&pg=PA4|year=1986|publisher=UPenn Museum of Archaeology|isbn=978-0-934718-52-3|page=4}}</ref> | |||

| On 12 March 1949, the first ] of Pakistan passed the ] which was proposed by the first ] ], proclaimed that the future constitution of Pakistan would not be modeled entirely on a ], but on the ideology and democratic faith of ]. The ] in 1954 saw the ] coming to power and its leader ] becoming country's first ] ]. Promulgation of ] in 1956 leads to Pakistan declaring itself ] (official name) with the adoption of ] ] of government. The constitution transformed the ] into ] (as ]). Subsequently, ] became the first president as well as first Bengali in 1956, but the democratic system was stalled after President Mirza imposed the ] and appointed ] as an enforcer of martial law. Two week later, President ] was ousted by ]; his presidency saw an era of internal instability and a ] with India in 1965. Economic grievances and political disenfranchisement in ] led to violent political tensions and armed repression, escalating into ]<ref name="civilwar"/> followed by the ] with India. After an intense ], followed by ] with ], the state of East Pakistan separated at a considerable distance from the rest of Pakistan and became the independent state of ] in 1971. Pakistan's defeat in the war ultimately led to the secession of East Pakistan and the birth of Bangladesh.<ref name="uscsbn"/> | |||

| Following the decline of the Indus valley civilization, ] moved into the ] from Central Asia originally from the ] in several ] in the ] (1500–500 BCE), bringing with them came their ] which fused with local culture.<ref name="White 2003 28">{{cite book |last=White |first=David Gordon |url=https://archive.org/details/kissyoginitantri00whit |title=Kiss of the Yogini |publisher=University of Chicago Press |year=2003 |isbn=978-0-226-89483-6 |location=Chicago |page= |url-access=limited}}</ref> The Indo-Aryans religious beliefs and practices from the ] and the native Harappan Indus beliefs of the former Indus Valley Civilisation eventually gave rise to Vedic culture and tribes.<ref>. Retrieved 12 May 2007.</ref>{{refn|Archaeological cultures identified with phases of Vedic culture include the ], the ], the ] and the ].{{sfn|Witzel|1989}}|group=note}} Most notable among them was ], which flourished at the crossroads of India, Central Asia, and the Middle East, connecting ] and absorbing cultural influences from diverse civilizations.<ref>Kurt A. Behrendt (2007), , pp.4—5, 91</ref> The initial early Vedic culture was a tribal, ] society centred in the Indus Valley, of what is today Pakistan. During this period the ], the oldest ] of ], were composed.{{refn|The precise time span of the period is uncertain. ] and ] evidence indicates that the ], the oldest of the Vedas, was composed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period.<ref name="Oberlies p. 158">Oberlies (1998:155) gives an estimate of 1100 BCE for the youngest hymns in book 10. Estimates for a ''terminus post quem'' of the earliest hymns are more uncertain. Oberlies (p. 158) based on 'cumulative evidence' sets wide range of 1700–1100</ref>|group=note}} | |||

| Democracy again returned which was resumed from 1972 to 1977 under leftist ] led by ], until he was varnished by General ], who became the country's third military president. Pakistan's banished-] policies were replaced by the new Islamic ]h legal code, which increased religious influences on the civil service and the military. With the ] of President Zia-ul-Haq in 1988, the new ] announced the victory of ] led by ] who was elevated as the country's first female ]. Over the next decade, she alternated power with conservative ] (PML(N)) led by ], as the country's political and economic situation becoming worsen. Military tensions in the ]<ref name="kargil"/> with India were followed by a ] in which General ] assumed executive powers. | |||

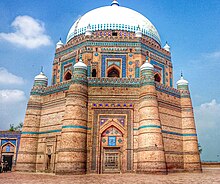

| The ensuing millennia saw the region of present-day Pakistan absorb many influences represented among others in the ancient, mainly ]-], sites of ], and ], the 14th-century ]-]i monuments of ], and the 17th-century ] monuments of ]. In the first half of the 19th century, the region was appropriated by the ], followed, after 1857, by 90 years of direct ], and ending with the creation of Pakistan in 1947, through the efforts, among others, of its future national poet ] and its founder, ]. Since then, the country has experienced both civilian democratic and military rule, resulting in periods of significant economic and military growth as well as those of instability; significant during the latter, was the 1971 ] of ] as the new nation of ].{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} | |||

| ] as ] after the resignation of President ], Musharraf held ] ] in 2002 to transfer the executive powers to newly elected Prime Minister ], who was succeeded in the 2004 by ]. During the election campaign in 2007 following the ] completing its term on 15 November 2007, Benazir Bhutto was ] which that resulted in a series of important political developments when ] led by ]. The historic ] held in 2013 marked the return of ] coming to national prominence with ] ] assuming the leadership of the country for the third time in the history. | |||

| == Prehistory == | == Prehistory == | ||

| === Paleolithic period === | |||

| The ] is archaeological culture of the ], ]. It is named after the ] in the Sivalik Hills, near modern-day ] and is dated between c.774,000 and c.11,700 BCE.<ref name="murray">{{cite book |last=Murray |first=Tim |author-link=Tim Murray (archaeologist) |title=Time and Archaeology |url=https://archive.org/details/timearchaeology00murr |url-access=limited |publisher=Routledge |year=1999 |location=London | page= |isbn=978-0-415-11762-3}}</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Neolithic period === | ||

| {{Main|Soanian}} | |||

| ], with houses built with mud bricks. (], Paris).]] | |||

| The ] is an archaeological culture of the ] (ca. 1.9 mya to 125,000 BC), contemporary to the ]. It is named after the ] in the Sivalik Hills, near modern-day ]/], Pakistan. The bearers of this culture were ]. In ] and ], about {{convert|16|km|mi}} from Rawalpindi, on the bend of the ] hundreds of edged pebble tools were discovered. No human skeletons of this age have yet been found. In the Soan River Gorge many fossil bearing rocks are exposed on the surface. The 14 million year old fossils of gazelle, rhinoceros, crocodile, giraffe and rodents have been found there. Some of these fossils are on display at the Natural History Museum in Islamabad. | |||

| ===Mehgarh period === | |||

| {{Main|Mehrgarh}} | {{Main|Mehrgarh}} | ||

| ] |

] is an important ] site discovered in 1974, which shows early evidence of farming and herding,<ref>Hirst, K. Kris. 2005. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170118071157/http://archaeology.about.com/od/mterms/g/mehrgarh.htm |date=18 January 2017 }}. ''Guide to Archaeology''</ref> and dentistry.<ref name="coppa">{{cite journal |last=Coppa|first=A.|author2=L. Bondioli |author3=A. Cucina |author4=D. W. Frayer |author5=C. Jarrige |author6=J. F. Jarrige |author7=G. Quivron |author8=M. Rossi |author9=M. Vidale |author10=R. Macchiarelli |title=Palaeontology: Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry|journal=Nature|volume=440|pages=755–756|doi=10.1038/440755a |pmid=16598247 |issue=7085|year=2006|bibcode=2006Natur.440..755C|s2cid=6787162}}</ref> The site dates back to 7000–5500 ] and is located on the Kachi Plain of ]. The residents of Mehrgarh lived in mud brick houses, stored grain in granaries, fashioned tools from ], cultivated barley, wheat, ]s and dates, and herded sheep, goats and cattle. As the civilization progressed (5500–2600 BCE) residents began to engage in crafts, including ], ], bead production, and ]. The site was occupied continuously until 2600 BCE,<ref>] 1996. "Mehrgarh." ''Oxford Companion to Archaeology'', edited by Brian Fagan. Oxford University Press, Oxford</ref> when climatic changes began to occur. Between 2600 and 2000 BCE, region became more arid and Mehrgarh was abandoned in favor of the Indus Valley,<ref name=guimet> | ||

| {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070928044049/http://www.guimet.fr/Indus-and-Mehrgarh-archaeological |date=28 September 2007 }}, Musée National des Arts Asiatiques – Guimet | |||

| </ref> where a ] was in the early stages of development.<ref> | |||

| Chandler, Graham. 1999. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070218235318/http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/199905/traders.of.the.plain.htm |date=18 February 2007 }} ''Saudi Aramco World''. | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ==Bronze age== | |||

| ==Indus Valley Civilization== | |||

| ===Indus Valley Civilisation=== | |||

| {{Main|Indus Valley Civilisation}} | |||

| The Indus Valley Civilization developed between 3300–1700 BCE on the banks of the ]. At its peak, the civilisation hosted a population of approximately 5 million in hundreds of settlements extending as far as the ], present-day southern and eastern ], southeastern ] and the ].<ref name="feuerstein">{{cite book|last=Feuerstein|first=Georg|coauthors=Subhash Kak; David Frawley|title=In search of the cradle of civilization: new light on ancient India|publisher=Quest Books|location=Wheaton, Illinois|year=1995|page=147|url=http://books.google.com/?id=kbx7q0gxyTcC&printsec=frontcover&dq=In+Search+of+the+Cradle+of+Civilization|isbn=978-0-8356-0720-9}}</ref> Major urban centers were at ], ], ], ], ], and ], as well as an offshoot called the ] (2500–2000 BCE) in southern Balochistan, which had similar settlements, pottery and other artifacts. The civilization collapsed abruptly around 1700 BCE. | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | align = | |||

| | direction = | |||

| | width = | |||

| | header = ] | |||

| | total_width = 300 | |||

| | perrow = 2 | |||

| | image1 = Mohenjo-daro Priesterkönig.jpeg | |||

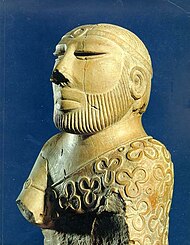

| | caption1 = The ] sculpture is carved from ]. | |||

| | image2 = Shiva Pashupati.jpg | |||

| | caption2 = The '']'' | |||

| | image3 = Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daro.jpg | |||

| | caption3 = The ] of Mohenjo-daro | |||

| | image4 = Mohenjodaro Sindh.jpeg | |||

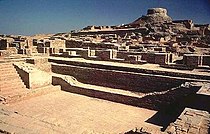

| | caption4 = Excavated ruins of the Great Bath at ] in ] | |||

| }} | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] in the ] began around 3300 BCE with the Indus Valley Civilization.{{Sfn|Wright|2009|p=1}} Along with ] and ], it was one of three early civilizations of the ], and of the three the most widespread,{{Sfn|Wright|2009|ps=: Quote: "The Indus civilization is one of three in the 'Ancient East' that, along with ] and ], was a cradle of early civilization in the Old World (Childe 1950). Mesopotamia and Egypt were longer lived, but coexisted with Indus civilization during its florescence between 2600 and 1900 B.C. Of the three, the Indus was the most expansive, extending from today's northeast Afghanistan to Pakistan and India."}} covering an area of 1.25 million km<sup>2</sup>.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Blanc De La|first1=Paul|title=Indus Epigraphic Perspectives: Exploring Past Decipherment Attempts & Possible New Approaches 2013 Pg 11|url=http://www.ruor.uottawa.ca/bitstream/10393/26166/1/Leblanc_Paul_2013_thesis.pdf|website=University of Ottawa Research|publisher=University of Ottawa|access-date=11 August 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140904103021/http://ruor.uottawa.ca/bitstream/10393/26166/1/Leblanc_Paul_2013_thesis.pdf|archive-date=4 September 2014|url-status=dead}}</ref> It flourished in the basins of the ], in what is today the Pakistani provinces of ], ] and ], and along a system of perennial, mostly monsoon-fed, rivers that once coursed in the vicinity of the seasonal ] in parts of north-west India.{{Sfn|Wright|2009|p=1}} At its peak, the civilization hosted a population of approximately 5 million spread across hundreds of settlements extending as far as the ] to present-day southern and eastern ], and the ].<ref name="feuerstein">{{cite book|last=Feuerstein|first=Georg|author2=Subhash Kak |author3=David Frawley |title=In search of the cradle of civilization: new light on ancient India|publisher=Quest Books|location=Wheaton, Illinois|year=1995|page=147|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kbx7q0gxyTcC|isbn=978-0-8356-0720-9}}</ref> Inhabitants of the ancient Indus river valley, the Harappans, developed new techniques in metallurgy and handicraft (carneol products, seal carving), and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin. | |||

| The Mature Indus civilisation flourished from about 2600 to 1900 BCE, marking the beginning of urban civilisation in the Indus Valley. The civilisation included urban centres such as ], ] and ] as well as an offshoot called the ] (2500–2000 BCE) in southern Balochistan and was noted for its cities built of brick, roadside drainage system, and multi-storeyed houses. It is thought to have had some kind of municipal organisation as well. | |||

| In the early part of the second millennium BCE, the Rigvedic civilization existed,<ref name="stein">{{cite book|last=Stein|first=Burton|title=A history of India|publisher=Blackwell Publishers|location=Oxford (UK); Malden (Mass.)|year=1998|isbn=978-0-631-17899-6}}</ref> between the ] and ]-] rivers.<ref name=britannica-early-vedic>"Early Aryan Period." 2007. In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2007-03-20, from : </ref> The city of ] in northern Pakistan, became important to Vedic religion (and later in ]).<ref>Taxila. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2007-03-19, from </ref> | |||

| During the ] of this civilisation, signs of a ] began to emerge, and by around 1700 BCE, most of the cities were abandoned. However, the Indus Valley Civilisation did not disappear suddenly, and some elements of the Indus Civilisation may have survived. ] of this region during the 3rd millennium BCE may have been the initial spur for the urbanisation associated with the civilisation, but eventually also reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilisation's demise, and to scatter its population eastward. The civilization collapsed around 1700 BCE, though the reasons behind its fall are still unknown. Through the excavation of the Indus cities and analysis of town planning and seals, it has been inferred that the Civilization had high level of sophistication in its town planning, arts, crafts, and trade.<ref>P. Biagi and E. Starnini 2021 - Indus Civilization. In Smith, C. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Springer Nature, Switzerland: 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1_3491-1</ref> | |||

| == {{anchor|Early history}} Early history == | |||

| == Early history – Iron Age == | |||

| ===Vedic period=== | ===Vedic period=== | ||

| {{Main|Vedic |

{{Main|Vedic period|Indo-Aryan Migration|Indo-Aryans|Vedas}} | ||

| {{Further|Sintashta culture}} | |||

| {{See also|Vedas|Indo-Aryans}} | |||

| ].]] | ].|left]] | ||

| Early Vedic society consisted of largely pastoral groups, with late Harappan urbanization having been abandoned.<ref>. Retrieved 2007-05-12.</ref> After the time of the ], Aryan society became increasingly agricultural and was socially organized around the four '']'', or social classes. In addition to the Vedas, the principal texts of Hinduism, the core themes of the Sanskrit epics ] and ] are said to have their ultimate origins during this period.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | author=Valmiki | editor = Goldman, Robert P | title = The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India, Volume 1: Balakanda | series = Ramayana of Valmiki | month = March | year = 1990 | publisher = ] | location = ] | isbn = 0-691-01485-X | page = 23}}</ref> The early Indo-Aryan presence probably corresponds, in part, to the ] in archaeological contexts.<ref name = "tqlgsv">{{cite book | author= Krishna Reddy | title = Indian History | year = 2003 | publisher = Tata McGraw Hill | location = New Delhi | isbn = 0-07-048369-8 | page = A11}}</ref> | |||

| The Vedic Period ({{circa|1500|500 BCE}}) is postulated to have formed during the 1500 BCE to 800 BCE. As Indo-Aryans migrated and settled into the Indus Valley, along with them came their distinctive religious traditions and practices which fused with local culture.<ref name="White 2003 28"/> The Indo-Aryans religious beliefs and practices from the ] and the native Harappan Indus beliefs of the former Indus Valley Civilisation eventually gave rise to Vedic culture and tribes.<ref>. Retrieved 12 May 2007.</ref>{{refn|group=note|Archaeological cultures identified with phases of Vedic culture include the ], the ], the ] and the ].{{sfn|Witzel|1989}}}} Early ] were a ] society centred in the ], organised into tribes rather than kingdoms, and primarily sustained by a ] way of life. During this period the ], the oldest ] of ], were composed.{{refn|group=note|The precise time span of the period is uncertain. ] and ] evidence indicates that the ], the oldest of the Vedas, was composed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period.<ref name="Oberlies p. 158">Oberlies (1998:155) gives an estimate of 1100 BCE for the youngest hymns in book 10. Estimates for a ''terminus post quem'' of the earliest hymns are more uncertain. Oberlies (p. 158) based on 'cumulative evidence' sets wide range of 1700–1100</ref>}} | |||

| The ]<ref>M. Witzel, Early Sanskritization. Origins and development of the Kuru State. B. Kölver (ed.), Recht, Staat und Verwaltung im klassischen Indien. The state, the Law, and Administration in Classical India. München : R. Oldenbourg 1997, 27–52 = Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies, vol. 1,4, December 1995, </ref> corresponds to the ] and ] cultures and to the beginning of the Iron Age in South Asia, around 1000 BCE, as well as with the composition of the ], the first Vedic text to mention iron, as {{IAST|śyāma ayas}}, literally "black metal." The Painted Grey Ware culture spanned much of northern India from about 1100 to 600 BCE.<ref name = "tqlgsv"/> The Vedic Period also established republics such as ], which existed as early as the 6th century BCE and persisted in some areas until the 4th century CE. The later part of this period corresponds with an increasing movement away from the previous tribal system towards the establishment of kingdoms, called '']''. | |||

| ==Ancient history== | |||

| === Achaemenid Empire === | === Achaemenid Empire === | ||

| {{Main|Achaemenid |

{{Main|Achaemenid invasion of the Indus Valley}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] representing the city of ] during the Achaemenid period]] | |||

| Little is known about the Achaemenid Persian invasion of modern-day ] as historical sources and evidence are scant and fragmentary containing little detail. There is no archaeological evidence of Achaemind control over modern-day Pakistan as not a single archaeological site that can be positively identified with the Achaemenid Empire has been found anywhere in Pakistan, including at ].<ref> http://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/bannu-archaeological-project/petrie2007_02.pdf</ref> What is known about the easternmost satraps and borderlands of the Achaemenid Empire are alluded to in the ] inscriptions and from Greek sources such as the ''Histories'' of ] and the later ''Alexander Chronicles'' (Arrian, Strabo et al.). These sources list three Indian tributaries or conquered territories that were subordinated to the Persian Empire and made to pay tributes to the Persian Kings: ], ] (Thatagus) and ].<ref name="arch.cam.ac.uk">{{cite web|url=http://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/bannu-archaeological-project/petrie2007_02.pdf |title=Microsoft Word - GS_Alexander_Arrian.doc |format=PDF |date= |accessdate=2013-04-04}}</ref> | |||

| The main Vedic tribes remaining in the ] by 550 BC were the ''Kamboja'', ''Sindhu'', ''Taksas'' of Gandhara, the ''Madras'' and ''Kathas'' of the ], ''Mallas'' of the ] and ''Tugras'' of the ]. These several tribes and principalities fought against one another to such an extent that the Indus Valley no longer had one powerful Vedic tribal kingdom to defend against outsiders and to wield the warring tribes into one organized kingdom. King ] of ] was engaged in power struggles against his local rivals and as such the ] remained poorly defended. ] of the ] took advantage of the opportunity and planned for an invasion. The Indus Valley was fabled in Persia for its gold and fertile soil and conquering it had been a major objective of his predecessor ].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Petrie |first1=Cameron A. |last2=Magee |first2=Peter |title=Histories, epigraphy and authority: Achaemenid and indigenous control in Pakistan in the 1st millennium BC |url=https://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/bannu-archaeological-project/petrie2007_02.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110611053344/https://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/bannu-archaeological-project/petrie2007_02.pdf |archive-date=2011-06-11 |access-date=18 April 2024}}</ref> In 542 BC, Cyrus had led his army and conquered the Makran coast in southern ]. However, he is known to have campaigned beyond Makran (in the regions of ], ] and ]) and lost most of his army in the ''Gedrosian Desert'' (speculated today as the ]). | |||

| In 518 BC, Darius led his army through the Khyber Pass and southwards in stages, eventually reaching the ] coast in Sindh by 516 BC. Under Persian rule, a system of centralized administration, with a bureaucratic system, was introduced into the Indus Valley for the first time, establishing several ]ies: ] around the general region of Gandhara, ] around Punjab and Sindh, ], encompassing parts of present-day ], and ],<ref name="Iranicaarticle">{{cite encyclopedia|last=Schmitt|first=Rüdiger|title=Arachosia |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Iranica |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/arachosia |date=10 August 2011}}</ref> ] around the ] basin,<ref name="arch.cam.ac.uk" /> and ] covering much of the ] region of southern Balochistan.<ref></ref> | |||

| Gandhara and Sattagydia (Thatagus) are listed amongst the provinces inherited by Darius when he seized the throne in 522 BC in his commemorative Behistun inscription, however, the dates of the initial annexation of these two regions is not certain.<ref name="arch.cam.ac.uk"/> The locations of Sattagydia and Hindush and the extent of their boundaries have not been identified either though it is certain that these two tributaries existed along the river Indus as the name Hindush is analogous with the Indus and was derived by the Persians from the ] word ''Sindhu''. | |||

| What is known about the easternmost satraps and borderlands of the Achaemenid Empire is alluded to in the ] inscriptions and from Greek sources such as the ''Histories'' of ] and the later ''Alexander Chronicles'' (Arrian, Strabo et al.). These sources list three Indus Valley tributaries or conquered territories that were subordinated to the Persian Empire and made to pay tributes to the Persian Kings.<ref name="arch.cam.ac.uk">{{cite web |url=http://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/bannu-archaeological-project/petrie2007_02.pdf |title=Microsoft Word - GS_Alexander_Arrian.doc |access-date=4 April 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120519044446/http://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/bannu-archaeological-project/petrie2007_02.pdf |archive-date=19 May 2012}}</ref> | |||

| Additionally, much of what constitutes ] province in southwest Pakistan formed part of the Achaemenid satrap of ].<ref></ref> | |||

| ===Macedonian Empire=== | |||

| == Greek rule == | |||

| {{Main|Indian campaign of Alexander the Great|Macedonian Empire}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ], with ]]] | |||

| By spring of 326 BC, Alexander began on his Indus expedition from Bactria, leaving behind 3500 horses and 10,000 soldiers. He divided his army into two groups. The larger force would enter the Indus Valley through the Khyber Pass, just as Darius had done 200 years earlier, while a smaller force under the personal command of Alexander entered through a northern route, possibly through ] or ] near ]. Alexander was commanding a group of shield-bearing guards, foot-companions, archers, Agrianians, and horse-javelin-men and led them against the tribes of the former Gandhara satrapy. | |||

| The first tribe they encountered were the ] tribe of the ], who initiated a fierce battle against Alexander, in which he himself was wounded in the shoulder by a dart. However, the Aspasioi eventually lost and 40,000 people were enslaved. Alexander then continued in a southwestern direction where he encountered the ] tribe of the ] & ] valleys in April 326 BC. The Assakenoi fought bravely and offered stubborn resistance to Alexander and his army in the cities of Ora, Bazira (]) and Massaga. So enraged was Alexander about the resistance put up by the Assakenoi that he killed the entire population of Massaga and reduced its buildings to rubble – similar slaughters followed in Ora.<ref>{{cite book|title=History and Culture of Indian People, The Age of Imperial Unity, Foreign Invasion|author=Mukerjee, R. K.|page=46}}</ref> A similar slaughter then followed at Ora, another stronghold of the Assakenoi. The stories of these slaughters reached numerous Assakenians, who began fleeing to Aornos, a hill-fort located between ] and ]. Alexander followed close behind their heels and besieged the strategic hill-fort, eventually capturing and destroying the fort and killing everyone inside. The remaining smaller tribes either surrendered or like the Astanenoi tribe of ] (]) were quickly neutralized where 38,000 soldiers and 230,000 oxen were captured by Alexander.<ref>Curtius in McCrindle, p. 192, J. W. McCrindle; ''History of Punjab'', Vol I, 1997, p 229, Punjabi University, Patiala (editors): Fauja Singh, L. M. Joshi; ''Kambojas Through the Ages'', 2005, p. 134, Kirpal Singh.</ref> Eventually Alexander's smaller force would meet with the larger force which had come through the Khyber Pass met at ]. With the conquest of Gandhara complete, Alexander switched to strengthening his military supply line, which by now stretched dangerously vulnerable over the ] back to ] in Bactria. | |||

| ===Greek invasion, colonization, and cultural heritage=== | |||

| After conquering Gandhara and solidifying his supply line back to Bactria, Alexander combined his forces with the King Ambhi of Taxila and crossed the River Indus in July 326 BC to begin the Archosia (Punjab) campaign. His first resistance would come at the ] near ] against King ] of the ] tribe. The famous ] (]) between Alexander (with Ambhi) and Porus would be the last major battle fought by him. After defeating Porus, his battle weary troops refused to advance into India<ref name="Plutarch1994">{{cite book|last1=Plutarch|first1=Mestrius|translator-last=Perrin|translator-first=Bernadotte|title=Plutarch's Lives|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oJhpAAAAMAAJ|access-date=23 May 2016 |volume=7|year=1994|publisher=Heinemann|location=London|isbn=978-0-674-99110-1|chapter=Chapter LXII}}</ref> to engage the army of ] and its vanguard of trampling elephants. Alexander, therefore proceeded south-west along the Indus Valley.<ref name="PlutarchLXIII">{{cite book|last1=Plutarch|first1=Mestrius|translator-last=Perrin|translator-first=Bernadotte|title=Plutarch's Lives|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oJhpAAAAMAAJ|access-date=23 May 2016|volume=7|year=1994|publisher=Heinemann|location=London|isbn=978-0-674-99110-1|chapter=Chapter LXIII}}</ref> Along the way, he engaged in several battles with smaller kingdoms in ] and ], before marching his army westward across the ] desert towards what is now ]. In crossing the desert, Alexander's army took enormous casualties from hunger and thirst, but fought no human enemy. They encountered the "Fish Eaters", or Ichthyophagi, primitive people who lived on the Makran coast, who had matted hair, no fire, no metal, no clothes, lived in huts made of whale bones, and ate raw seafood. | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Alexander the Great}} | |||

| Crushing the Persian Achaemenid empire, ], the Greek king from ], invaded the region of modern Pakistan and conquered much of the ]. After defeating ] in the ] (modern-day ]), his battle weary troops refused to advance further into India<ref name="plutarch62">{{cite book|last=Plutarchus|first=Mestrius|authorlink=Plutarch|coauthors=Bernadotte Perrin (trans.)|title=Plutarch's Lives|publisher=William Heinemann|year=1919|location=London|pages=Ch. LXII|url=http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plut.+Caes.+62.1|isbn=978-0-674-99110-1|accessdate=2007-11-27}}</ref> to engage the army of ] and its vanguard of trampling elephants. Alexander, therefore proceeded southwest along the Indus valley.<ref name="plutarch63">{{cite book|last=Plutarchus|first=Mestrius|authorlink=Plutarch|coauthors=Bernadotte Perrin (trans.)|title=Plutarch's Lives|publisher=William Heinemann|year=1919|location=London|pages=Ch. LXIII|url=http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Plut.+Caes.+63.1|isbn=978-0-674-99110-1|accessdate=2007-11-27}}</ref> Along the way, he engaged in several battles with smaller kingdoms before marching his army westward across the ] towards what is now Iran. Alexander founded several new Macedonian and Greek settlements in ], ] and ].{{Citation needed|date=July 2012}} During that time, many Greeks settled all over in Pakistan,{{Dubious|date=July 2012}} initiating interaction between the culture of ] and the region's prevalent ] and ] cultures. | |||

| === Mauryan Empire === | |||

| {{Main|Greco-Bactrian Kingdom}} | |||

| {{Main|Maurya Empire|Greco-Bactrian Kingdom|Greco-Buddhism}} | |||

| After Alexander's death in 323 BC, his '']'' (generals) divided the empire among themselves, with the Macedonian warlord ] setting up the ], which included the Indus plain.<ref name="appian">{{cite book|author=Appian of Alexandria|authorlink=Appian|coauthors=Horace White (trans.)|title=The Roman History of Appian of Alexandria|publisher=Macmillan & Co.|year=1899|url=http://www.livius.org/ap-ark/appian/appian_syriaca_11.html|accessdate=2007-11-27}}</ref> Around 250 BCE, the eastern part of the Seleucid Kingdom broke away to form the ]. | |||

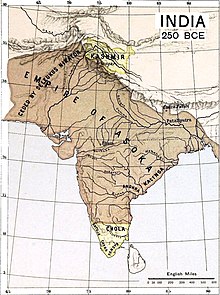

| ] under king ], c.250 BCE.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/cu31924022983567/page/n23/mode/1up|title=Historical atlas of India, for the use of high schools, colleges and private students|last=Joppen|first=Charles|date=1907|publisher=London; New York : Longmans, Green|others=Cornell University Library|pages=map 2}}</ref>]] | |||

| The Maurya Empire was a geographically extensive ] ] in ] based in ], having been founded by ] in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until 185 BCE.<ref name="Dyson2018-lead-maurya"> | |||

| === Maurya Empire === | |||

| {{citation | |||

| ]]] | |||

| |last=Dyson|first=Tim|title=A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3TRtDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA16|year=2018|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-882905-8|pages=16–17}} Quote: "Magadha power came to extend over the main cities and communication routes of the Ganges basin. Then, under Chandragupta Maurya (c.321–297 bce), and subsequently Ashoka his grandson, Pataliputra became the centre of the loose-knit Mauryan 'Empire' which during Ashoka's reign (c.268–232 bce) briefly had a presence throughout the main urban centres and arteries of the subcontinent, except for the extreme south."</ref> The Maurya Empire was centralized by the conquest of the ], and its capital city was located at ] (modern ]). Outside this imperial centre, the empire's geographical extent was dependent on the loyalty of military commanders who controlled the armed cities sprinkling it.<ref name="Ludden2013-lead-maurya"> | |||

| {{Main|Maurya Empire}} | |||

| {{citation | |||

| Modern-day Pakistan was conquered by ], who overthrew the powerful ] of ] and established the Maurya Empire: He conquered the trans-] region to the west, which was under Macedonian rule - annexing ], south eastern parts of ] and much of what is now ], including the modern ]<ref name="historyfiles.co.uk">{{cite web|last=Rajadhyaksha |first=Abhijit |url=http://www.historyfiles.co.uk/FeaturesFarEast/India_IronAge_Mauryas01.htm |title=The Mauryas: Chandragupta |publisher=Historyfiles.co.uk |date=2009-08-02 |accessdate=2013-04-04}}</ref> and ] provinces - and then defeated the invasion led by ], a Greek general from Alexander's army. Seleucus is said to have reached a ] with Chandragupta by giving him control of the territory south of the Hindu Kush upon intermarriage as well as 500 elephants. | |||

| |last=Ludden | |||

| |first=David|title=India and South Asia: A Short History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EbFHAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA29|year=2013|publisher=Oneworld Publications|isbn=978-1-78074-108-6|pages=29–30}} |quote=The geography of the Mauryan Empire resembled a spider with a small dense body and long spindly legs. The highest echelons of imperial society lived in the inner circle composed of the ruler, his immediate family, other relatives, and close allies, who formed a dynastic core. Outside the core, empire travelled stringy routes dotted with armed cities. Outside the palace, in the capital cities, the highest ranks in the imperial elite were held by military commanders whose active loyalty and success in war determined imperial fortunes. Wherever these men failed or rebelled, dynastic power crumbled. ... Imperial society flourished where elites mingled; they were its backbone, its strength was theirs. Kautilya's ''Arthasastra'' indicates that imperial power was concentrated in its original heartland, in old ''Magadha'', where key institutions seem to have survived for about seven hundred years, down to the age of the Guptas. Here, Mauryan officials ruled local society, but not elsewhere. In provincial towns and cities, officials formed a top layer of royalty; under them, old conquered royal families were not removed, but rather subordinated. In most ''janapadas'', the Mauryan Empire consisted of strategic urban sites connected loosely to vast hinterlands through lineages and local elites who were there when the Mauryas arrived and were still in control when they left.</ref>{{sfn|Hermann Kulke|2004|pp=xii, 448}}<ref>{{cite book | first1=Romila | last1=Thapar | title=A History of India, Volume 1 | publisher=Penguin Books | author-link=Romila Thapar | year=1990 | page=384 | isbn=0-14-013835-8}}</ref> During ]'s rule (ca. 268–232 BCE) the empire briefly controlled the major urban hubs and arteries of the ] excepting the deep south.<ref name="Dyson2018-lead-maurya"/> It declined for about 50 years after Ashoka's rule, and dissolved in 185 BCE with the assassination of Brihadratha by ] and foundation of the ] in Magadha. | |||

| Chandragupta Maurya raised an army, with the assistance of ], author of ],<ref>{{Cite book|title=India: A History|last=Keay|first=John|publisher=Grove Press|year=2000|isbn=978-0-8021-3797-5|pages=82}}</ref> and overthrew the ] in {{circa|322 BCE}}. Chandragupta rapidly expanded his power westwards across central and western India by conquering the ]s left by ], and by 317 BCE the empire had fully occupied northwestern India.{{sfn|R. K. Mookerji|1966|p=31}} The Mauryan Empire then defeated ], a ] and founder of the ], during the ], thus acquiring territory west of the Indus River.<ref>] ceded the territories of ] (modern Kandahar), ] (modern ]), and ] (or ]). ] (modern ]) "has been wrongly included in the list of ceded satrapies by some scholars ... on the basis of wrong assessments of the passage of Strabo ... and a statement by Pliny" (Raychaudhuri & Mukherjee 1996, p. 594).</ref>{{sfn|John D Grainger|2014|p=109|ps=: Seleucus "must ... have held Aria", and furthermore, his "son ] was active there fifteen years later".}} | |||

| {{quote|''Alexander took these away from the ] and established settlements of his own, but ] gave them to ] (]), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants.''<ref name="aisk">{{cite web |url=http://www.aisk.org/aisk/NHDAHGTK05.php |title=An Historical Guide to Kabul: The Name |author=Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād|publisher=American International School of Kabul |year=1972 |accessdate=2010-09-18}}</ref>|]|64 BC–24 AD}} | |||

| Under the Mauryas, internal and external trade, agriculture, and economic activities thrived and expanded across South Asia due to the creation of a single and efficient system of finance, administration, and security. The Maurya dynasty built a precursor of the ] from Patliputra to Taxila.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://roadsandkingdoms.com/2016/dinner-on-the-grand-trunk-road/|title=Dinner on the Grand Trunk Road|last=Bhandari|first=Shirin|date=2016-01-05|publisher=Roads & Kingdoms|language=en-US|access-date=2016-07-19}}</ref> After the ], the Empire experienced nearly half a century of centralized rule under Ashoka. Ashoka's embrace of ] and sponsorship of Buddhist missionaries allowed for the expansion of that faith into ], northwest India, and Central Asia.{{sfn|Hermann Kulke|2004|p=67}} | |||

| Emperors Chandragupta and ] expanded the Empire into India's central and southern areas, while ] pushed further into previously unexplored tribal and forested regions near ] (modern ]). With an area of 5,000,000 km<sup>2</sup>, the Maura Empire was one of the world's ] in its time, and the largest ever in the South Asia. At its greatest extent, the empire stretched to the north along the natural boundaries of the ], and to the east stretching into what is now ] province near the border with modern ] (]). | |||

| The population of South Asia during the Mauryan period has been estimated to be between 15 and 30 million.<ref name="Dyson2018-lead-maurya-4"> | |||

| Under Chandragupta and his successors, internal and external trade, agriculture and economic activities, all thrived and expanded across India thanks to the creation of a single and efficient system of finance, administration, and security. Mauryan India also enjoyed an era of social harmony, religious transformation, and expansion of the sciences and of knowledge. Mauryans were followers of ] and ]. Chandragupta Maurya's embrace of ] increased social and religious renewal and reform across his society, while Ashoka's embrace of Buddhism has been said to have been the foundation of the reign of social and political peace and non-violence across all of ]. Ashoka sponsored the spreading of Buddhist ideals into ], Southeast Asia, West Asia and Mediterranean Europe.<ref name="historyfiles.co.uk"/> After the ], the Empire experienced half a century of peace and security under Ashoka. Mauryan Empire's decline began 60 years after Ashoka's rule ended, and it dissolved in 185 BC with the foundation of the ] in Magadha. | |||

| {{citation | |||

| |last=Dyson|first=Tim|title=A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3TRtDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA24|year=2018|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-882905-8|page=24}} Quote: "Yet Sumit Guha considers that 20 million is an upper limit. This is because the demographic growth experienced in core areas is likely to have been less than that experienced in areas that were more lightly settled in the early historic period. The position taken here is that the population in Mauryan times (320–220 BCE) was between 15 and 30 million—although it may have been a little more, or it may have been a little less."</ref> | |||

| The empire's period of dominion was marked by exceptional creativity in art, architecture, inscriptions and produced texts.<ref name="Ludden2013-lead-4"> | |||

| {{citation | |||

| |last=Ludden | |||

| |first=David|title=India and South Asia: A Short History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EbFHAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA28|year=2013|publisher=Oneworld Publications|isbn=978-1-78074-108-6|pages=28–29}}Quote: "A creative explosion in all the arts was a most remarkable feature of this ancient transformation, a permanent cultural legacy. Mauryan territory was created in its day by awesome armies and dreadful war, but future generations would cherish its beautiful pillars, inscriptions, coins, sculptures, buildings, ceremonies, and texts, particularly later Buddhist writers." | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ==Classical history – Middle Kingdoms== | |||

| ===Gandhara culture=== | |||

| Greco-Buddhism (or Græco-Buddhism) was the ] between the culture of ] and ] in the then ] region of modern ] and Pakistan, between the 4th century BCE and the 5th century CE.<ref name="mcevilly">{{cite book|last=McEvilley|first=Thomas|title=The shape of ancient thought|publisher=Allworth Press|year=2002|location=New York|url=http://www.google.co.uk/books?id=Vpqr1vNWQhUC&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+shape+of+ancient+thought%7C+publisher&sig=mLs2tF5QycF9U5uIj9vEsElLbpI|isbn=978-1-58115-203-6|accessdate=2007-11-27}}</ref> It influenced the artistic development of Buddhism, and in particular ], before it spread to central and eastern Asia, from the 1st century CE onward. ] (son of the ] king ]) invaded northern India in 180 BCE as far as ] and established an ]. To the south, the Greeks captured ] and nearby coastal areas, completing the invasion by 175 BCE and confining the borders of ] (]) to the east. Meanwhile, in Bactria, the usurper ] killed Demetrius in a battle. Although the Indo-Greeks lost part of the Gangetic plain, their kingdom lasted nearly two centuries. | |||

| === |

===Indo-Greek Kingdom=== | ||

| {{Main|Indo-Greek Kingdom|Greco-Buddhist art|Indo-Greek art}} | |||

| ], who ruled the eastern dominions of the divided Greek empire of ] and the modern Pakistani provinces of the ], ] and ].]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The Indo-Greek ] (reigned 155–130 BCE) drove the Greco-Bactrians out of ] and beyond the ], becoming a king shortly after his victory. His territories covered ] and ] in modern Afghanistan and extended to the ], with many tributaries to the south and east, possibly as far as ]. The capital ] (modern ]) prospered greatly under Menander's rule and Menander is one of the few Bactrian kings mentioned by Greek authors.<ref name="strabo">{{cite book|author=Strabo|authorlink=Strabo|coauthors=H. L. Jones (ed.)|title=Geographica|publisher=William Heinemann|year=1924|location=London|pages=Ch. XI|url=http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Strab.+11.11.1|isbn=978-0-674-99055-5|accessdate=2007-11-22}}</ref> The classical ] ] praises Menander, saying there was "none equal to Milinda in all India".<ref name="davids">{{cite book|last=Davids|first=T. W. Rhys (trans.)|authorlink=Rhys Davids|title=The Milinda-questions|publisher=Routledge|date=2000, 1930|location=London|url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/sbe35/sbe3503.htm|isbn=978-0-415-24475-6|accessdate=2007-11-22}}</ref> His empire survived him in a fragmented manner until the last independent Greek king, ], disappeared around 10 CE. Around 125 BCE, the Greco-Bactrian king ], son of Eucratides, fled from the ] invasion of Bactria and relocated to Gandhara, pushing the Indo-Greeks east of the ]. The last known Indo-Greek ruler was ], from the ] area of Gandhara, mentioned on a 1st-century CE signet ring, bearing the Kharoṣṭhī inscription ''"Su Theodamasa"'' (''"Su"'' was the Greek transliteration of the ] royal title ''"Shau"'' ("]" or "King")). Various petty kings ruled into the early 1st century CE, until the conquests by the ], ] and the Yuezhi, who founded the Kushan dynasty. | |||

| ] in the guise of the Hellenic god ]<ref>"The Buddha accompanied by Vajrapani, who has the characteristics of the Greek Heracles" Description of the same image on the cover page in {{cite book |last1=Stoneman |first1=Richard |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Mx4OEAAAQBAJ&pg=PR4 |title=The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks |date=8 June 2021 |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0-691-21747-5 |page=4 |language=en}} Also "Herakles found an independent life in India in the guise of Vajrapani, the bearded, club-wielding companion of the Buddha" in {{cite book |last1=Stoneman |first1=Richard |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Mx4OEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA88 |title=The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks |date=8 June 2021 |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0-691-21747-5 |pages=88–89 |language=en}}</ref>]] | |||

| The Indo-Greek ] (reigned 155–130 BCE) drove the Greco-Bactrians out of ] and beyond the ], becoming king shortly after his victory. His territories covered ] and ] in modern Afghanistan and extended to the ], with many tributaries to the south and east, possibly as far as ]. The capital ] (modern ]) prospered greatly under Menander's rule and Menander is one of the few Bactrian kings mentioned by Greek authors.<ref name="strabo">{{cite book|author=Strabo|author-link=Strabo |editor-last=Jones |editor-first=H. L. |title=Geographica|publisher=William Heinemann|year=1924|location=London|pages=Ch. XI|url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?lookup=Strab.+11.11.1|isbn=978-0-674-99055-5|access-date=22 November 2007}}</ref> | |||

| The classical ] ] praises Menander, saying there was "none equal to Milinda in all India".<ref name="davids">{{cite book|last=Davids|first=T. W. Rhys (trans.)|title=The Milinda-questions|publisher=Routledge|edition=2000|date= 1930|location=London|url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/sbe35/sbe3503.htm|isbn=978-0-415-24475-6|access-date=22 November 2007}}</ref> His empire survived him in a fragmented manner until the last independent Greek king, ], disappeared around 10 CE. Around 125 BCE, the Greco-Bactrian king ], son of Eucratides, fled from the ] invasion of Bactria and relocated to Gandhara, pushing the Indo-Greeks east of the ]. The last known Indo-Greek ruler was ], from the ] area of Gandhara, mentioned on a 1st-century CE signet ring, bearing the Kharoṣṭhī inscription ''"Su Theodamasa"'' (''"Su"'' was the Greek transliteration of the ] royal title ''"Shau"'' ("]" or "King")). Various petty kings ruled into the early 1st century CE, until the conquests by the ], ] and the Yuezhi, who founded the Kushan dynasty. | |||

| ===Indo-Scythians=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] were descended from the ] (Scythians) who migrated from southern ] to ] and ] from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century BCE. They displaced the Indo-Greeks and ruled a kingdom that stretched from Gandhara to ]. Scythian tribes spread into the present-day Pakistan region and the Iranian plateau. The power of the Saka rulers started to decline in the 2nd century CE after the Scythians were defeated by the south Indian Emperor ] of the ] .<ref>World history from early times to A D 2000 by B .V. Rao: p.97</ref><ref>A Brief History of India by Alain Daniélou p.136</ref> Later the Saka kingdom was completely destroyed by ] of the ] in the 4th century.<ref>Ancient India by Ramesh Chandra Majumdar p. 234</ref> | |||

| It is during this period that the fusion of Hellenistic and Asiatic mythological, artistic and religious elements becomes most apparent, especially in the region of Gandhara, straddling western Pakistan and southern Afghanistan. Detailed, humanistic representations of the Buddha begin to emerge, depicting the figure with a close resemblance to the Hellenic god Apollo; Greek mythological motifs such as centaurs, Bacchanalian scenes, Nereids and deities such as Tyche and Heracles are prominent in the Buddhistic art of ancient Pakistan and Afghanistan.{{Citation needed|date=January 2024}} | |||

| ===Indo-Parthians, Romans and Christianity=== | |||

| The ], a nomadic Central Asian tribe, invaded ] in the middle of the 3rd century BCE, drove away its Greek satraps — who had just then proclaimed independence from the Seleucids — and annexed much of the Indus region, thus founding an ]{{Citation needed|date=July 2012}} dynasty of Scythian or Bactrian origin. Following the decline of the central ] authority after clashes with the ], a local Parthian leader, ] established the ] in the 1st century CE. The kingdom was ruled from ] and covered much of modern southeast Afghanistan and Pakistan.<ref name="earrings">{{cite web|url=http://www.marymount.k12.ny.us/marynet/stwbwk05/05vm/earrings/html/emanalysis.html|title=Parthian Pair of Earrings|publisher=Marymount School, New York|accessdate=2007-11-22}}</ref> | |||

| Christian writings claim<!-- Ref. WP Article on St. Thomas --> that the Apostle ] – an architect and skilled carpenter – had a long sojourn in the court of king ], had built a palace for the king at ] and had also ordained leaders for the Church before leaving for ] in a chariot, for sailing out to eventually reach ]. | |||

| === |

===Indo-Scythian Kingdom=== | ||

| ] of the type found in the Early Saka layer at ], ]]] | |||

| {{Main|Kushan Empire}} | |||

| ] and ].]] | |||

| ]]The next important chapter in Pakistan's history begins with the arrival of another wave of Central Asian tribes called the ], a branch of which was known as the Kushans. The Kushan kingdom (30-375 C.E.) was founded by King ], and greatly expanded by his successor, ]. Kadphises' son, ] conquered territory now in India, but lost much of the west of the kingdom to the Parthians. The fourth Kushan emperor, ] I, (c. 127 CE) had a winter capital at Purushapura (]) and a summer capital at Kapisa (]). Kushan's Bring new trends to Budding and Blossoming ], which reached its peak during Kushan Rule. ] and ] have been seats of learning and art, centres of great religious activity and pivots of political power during that period.<ref></ref> | |||

| The ] were descended from the ] (Scythians) who migrated from southern Central Asia into ] and ] from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century BCE. They displaced the Indo-Greeks and ruled a kingdom that stretched from Gandhara to Mathura. The power of the Saka rulers started to decline in the 2nd century CE after the Scythians were defeated by the south Indian Emperor ] of the ].<ref>World history from early times to A D 2000 by B .V. Rao: p.97</ref><ref>A Brief History of India by Alain Daniélou p.136</ref> Later the Saka kingdom was completely destroyed by ] of the ] from eastern India in the 4th century.<ref>Ancient India by Ramesh Chandra Majumdar p. 234</ref> | |||

| The kingdom linked the ] maritime trade with the commerce of the ] through the Indus valley. At its height, the empire extended from the ] to northern India, encouraging long-distance trade, particularly between ] and ]. Kanishka convened a great Buddhist council in Taxila, marking the start of the pantheistic ] Buddhism and its scission with ]. The art and culture of Gandhara — the best known expressions of the interaction of Greek and Buddhist cultures — also continued over several centuries, until the 5th century CE ] invasions of ]. The travelogues of Chinese pilgrims ] (337 – ca.422 CE) and ] (602/603–664 CE) describe the state of famed ] seminary at ] and the status of ] in the region of Pakistan in this period.<ref>Si-Yu-Ki, Buddhist Records of the Western World, (Tr. Samuel Beal: Travels of Fa-Hian, The Mission of Sung-Yun and Hwei-S?ng, Books 1–5), Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. London. 1906</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Indo-Parthian Kingdom === | ||

| {{main|Apracharajas|Paratarajas}} | |||

| ] at its maximum extent.]] | |||

| ] ] ] (a ]) constructed by the Indo-Parthians]] | |||

| {{Main|Gupta Empire}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The Gupta Empire existed approximately from 320 to 600 CE and covered much of the ], including modern Pakistan.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|title=Gupta Dynasty – MSN Encarta |url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761571624/gupta_dynasty.html|work=|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/5kwqOxl5F|archivedate=2009-10-31|deadurl=yes}}</ref> Founded by ], the dynasty was the model of a ''classical civilization''<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.fsmitha.com/h1/ch28gup.htm |title=The Gupta Dynasty and Empire |publisher=Fsmitha.com |date= |accessdate=2013-04-04}}</ref> and was marked by extensive inventions and discoveries.<ref>http://www.wsu.edu:8001/~dee/ANCINDIA/GUPTA.HTM</ref><ref>. Indianchild.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.</ref> | |||

| The ] was ruled by the Gondopharid dynasty, named after its eponymous first ruler ]. They ruled parts of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan,<ref name="earrings">{{cite web|url=http://www.marymount.k12.ny.us/marynet/stwbwk05/05vm/earrings/html/emanalysis.html|title=Parthian Pair of Earrings|publisher=Marymount School, New York|access-date=22 November 2007|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071024151850/http://www.marymount.k12.ny.us/marynet/stwbwk05/05vm/earrings/html/emanalysis.html|archive-date=24 October 2007}}</ref> and northwestern ], during or slightly before the 1st century AD. For most of their history, the leading Gondopharid kings held ] (in the present ] province of Pakistan) as their residence, but during their last few years of existence the capital shifted between ] and ]. These kings have traditionally been referred to as Indo-Parthians, as their coinage was often inspired by the ] dynasty, but they probably belonged to a wider groups of ] tribes who lived east of ] proper, and there is no evidence that all the kings who assumed the title ''Gondophares'', which means "Holder of Glory", were even related. Christian writings claim<!-- Ref. WP Article on St. Thomas --> that the Apostle ] – an architect and skilled carpenter – had a long sojourn in the court of king ], had built a palace for the king at Taxila and had also ordained leaders for the Church before leaving for ] in a chariot, for sailing out to eventually reach ]. | |||

| === Kushan Empire === | |||

| The high points of this cultural creativity are magnificent architectures, sculptures and paintings.{{clarify|date=October 2011}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/249590/Gupta-dynasty |title=Gupta dynasty (Indian dynasty) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia |publisher=Britannica.com |date= |accessdate=2013-04-04}}</ref><ref>Mahajan, V.D. (1960) ''Ancient India'', New Delhi: S. Chand, ISBN 81-219-0887-6, p. 540</ref><ref></ref> Science and political administration reached new heights during the Gupta era.{{clarify|date=October 2011}}<ref>{{cite web|author=Thorfire Enterprises |url=http://www.historybits.com/gupta.htm |title=The Gupta Empire of India | Chandragupta I | Samudragupta History |publisher=Historybits.com |date=2001-09-11 |accessdate=2013-04-04}}</ref> Strong trade ties also made the region an important cultural center and set the region up as a base that would influence nearby kingdoms and regions in ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pbs.org/thestoryofindia/gallery/photos/8.html |title=Trade | The Story of India - Photo Gallery |publisher=PBS |date= |accessdate=2013-04-04}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Kushan Empire|Kushan coinage|Kanishka}} | |||

| ]'s ] once kept sacred ] relics in the ].]] | |||

| ]. Most historians consider the empire to have variously extended as far east as the middle Ganges plain,<ref>{{cite book|author=Romila Thapar|title=Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300|year=2004|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-24225-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-5irrXX0apQC&pg=PA221|page=221}}</ref> to Varanasi on the confluence of the ] and the ],<ref>{{cite book|author=Burton Stein|title=A History of India |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QY4zdTDwMAQC&pg=PA86|date= 2010|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-1-4443-2351-1|page=86}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Peter Robb|title=A History of India|publisher=Macmillan International Higher Education|year=2011|isbn=978-0-230-34549-2|page=55}}</ref> or probably even ].<ref>{{cite book |author1=Hermann Kulke|author2=Dietmar Rothermund |title=A History of India|publisher=Taylor & Francis |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xYelDQAAQBAJ|year=2016|isbn=978-1-317-24212-3}}</ref><ref name="AADC">{{cite book |last1=Di Castro |first1=Angelo Andrea |last2=Hope |first2=Colin A. |chapter=The Barbarisation of Bactria |title=Cultural Interaction in Afghanistan c 300 BCE to 300 CE |date=2005 |publisher=Monash University Press |location=Melbourne |isbn=978-1876924393 |pages=1-18, map visible online page 2 of }}</ref>]] | |||

| The ] expanded out of what is now Afghanistan into the northwest of the subcontinent under the leadership of their first emperor, ], about the middle of the 1st century CE. They were descended from an Indo-European, Central Asian people called the ],<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/105520/Zhang-Qian |title=Zhang Qian |date=2015 |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica}}</ref><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/654618/Yuezhi |title=Yuezhi |date=2015 |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica}}</ref> a branch of which was known as the Kushans. By the time of his grandson, ], the empire spread to encompass much of Afghanistan<ref>Si-Yu-Ki, Buddhist Records of the Western World, (Tr. Samuel Beal: Travels of Fa-Hian, The Mission of Sung-Yun and Hwei-S?ng, Books 1–5), Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. London. 1906 and Hill (2009), pp. 29, 318–350</ref> and the northern parts of the ] at least as far as ] and ] near ] (Benares).<ref>which began about 127 CE. "Falk 2001, pp. 121–136", Falk (2001), pp. 121–136, Falk, Harry (2004), pp. 167–176 and Hill (2009), pp. 29, 33, 368–371.</ref> | |||

| Emperor Kanishka was a great patron of ]; however, as Kushans expanded southward, the deities<ref name="Samad2011">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pNUwBYGYgxsC&pg=PA93|title=The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys|publisher=Algora Publishing|year=2011|isbn=978-0-87586-859-2|pages=93–|author=Rafi U. Samad}}</ref> of their later coinage came to reflect its new ] majority.<ref name="Frumkin1970">{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/archaeologyinsov0000frum|url-access=registration|title=Archaeology in Soviet Central Asia|publisher=Brill Archive|year=1970|pages=–|id=GGKEY:4NPLATFACBB|author=Grégoire Frumkin}}</ref> The monumental Kanishka stupa is believed to have been established by the king near the outskirts of modern-day Peshawar, Pakistan. | |||

| The empire gradually declined due in part to loss of territory and imperial authority caused by their own erstwhile feudatories, and from the invasion by the ]s from Central Asia.<ref name="aa">Agarwal, Ashvini (1989). ''Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas'', Delhi:Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0592-5, pp. 264–269</ref> After the collapse of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century, India was again ruled by numerous regional kingdoms. A minor line of the Gupta clan continued to rule Magadha after the disintegration of the empire. These Guptas were ultimately ousted by the Vardhana king ], who established an empire in the first half of the 7th century. | |||

| The Kushan dynasty played an important role in the establishment of Buddhism in India and its spread to Central Asia and China. Historian ] said about Kanishka in particular: | |||

| === Sassanid Empire=== | |||

| Over the next few centuries, while the Parthians and Kushans shared control of the Indus plain until the arrival of the White Huns, the Persian ] dominated the south and southwest.{{citation needed|date=July 2013}} | |||

| {{Blockquote|He played the part of a second Ashoka in the history of Buddhism.<ref name="ReferenceC">Oxford History of India – Vincent Smith</ref>}} | |||

| ===The White Huns=== | |||

| The ], who seem to have been part of the predominantly ] ] group, established themselves in Afghanistan by the first half of the 5th century, with their capital at ]. Led by the Hun military leader ], they overran the northern region of Pakistan and made their capital at the city of Sakala, modern ] in ], under Toramana's son, Emperor ], who was a ] ]. Hiuen Tsiang narrates Mihirakula's merciless persecution of Buddhists and destruction of monasteries.<ref>Hiuen Tsiang, Si-Yu-Ki, Buddhist Records of the Western World, (Tr. Samuel Beal), Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. London. 1906, pp. 167–168.</ref> | |||

| The Huns were defeated by the Indian kings ] of Malwa and Narasimhagupta of the ] in the 6th century and were driven out of India.<ref>History of India by N. Jayapalan p.134</ref><ref>The First Spring: The Golden Age of India by Abraham Eraly p.48</ref> | |||

| The empire linked the Indian Ocean maritime trade with the commerce of the ] through the Indus valley, encouraging long-distance trade, particularly between China and ]. The Kushans brought new trends to the budding and blossoming ], which reached its peak during Kushan Rule. | |||

| ===Rai dynasty=== | |||

| {{Main|Rai Dynasty}} | |||

| According to ], the ] of ] (c. 489–632) arose after the end of ]. They were practitioners of ] and ]; they established a huge temple of ] in present-day ] – derived from original ] – close to their capital in ].<ref name=" Thakur Deshraj ">Thakur Deshraj, Jat Itihas (Hindi), Maharaja Suraj Mal Smarak Shiksha Sansthan, Delhi, 1934, 2nd edition 1992</ref> At the time of Rai Diwaji (Devaditya), influence of the Rai-state exdended from ] in the east, ] and Debal (]) port in the south, ], ], Suleyman, Ferdan and Kikanan hills in the north. | |||

| H.G. Rowlinson commented: | |||

| ===Pāla Empire=== | |||

| {{Main|Pala Empire}} | |||

| {{Blockquote|The Kushan period is a fitting prelude to the Age of the Guptas.<ref>Ancient and Medieval History of India – H.G. Rowlinson</ref>}} | |||

| The Pāla Empire was an Indian imperial power, . It was ruled by a Buddhist dynasty from Bengal in the eastern region of the Indian subcontinent. At the time of their greatest extent from 770 to 850 A.D. they ruled over Northern parts | |||

| of Pakistani regions.<ref></ref> | |||

| By the 3rd century, their empire in India was disintegrating and their last known great emperor was ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kushan.org/general/other/part1.htm|title=The History of Pakistan: The Kushans|website=www.kushan.org|access-date=30 April 2017|archive-date=7 July 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150707162312/http://www.kushan.org/general/other/part1.htm|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>Si-Yu-Ki, Buddhist Records of the Western World, (Tr. Samuel Beal: Travels of Fa-Hian, The Mission of Sung-Yun and Hwei-S?ng, Books 1–5), Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd. London. 1906</ref> | |||

| == Later Medieval Age == | |||

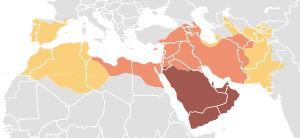

| ] ]. {{legend|#a1584e|Expansion under Muhammad, 622–632}} {{legend|#ef9070|Expansion during the Rashidun Caliphate, 632–661}} {{legend|#fad07d|Expansion during the Umayyad Caliphate, 661–750}}]] | |||

| === |

===Alchon Huns=== | ||