| Revision as of 17:53, 25 September 2019 editBharatiya29 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,647 edits Undid revision 913126689 by DdBbCc22 (talk) Undue additionTag: Undo← Previous edit | Revision as of 13:04, 23 December 2024 edit undoEltabar243 (talk | contribs)67 edits →Zutt RebellionTag: content sourced to vanity pressNext edit → | ||

| (835 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| {{about|the history of the ] before 1947 | |||

| |the history of Pakistan |

{{about|the pre-1947 history of Pakistan|post-1946 history|History of Pakistan (1947–present)}} | ||

| {{Use Pakistani English|date=April 2020}} | |||

| |History of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2019}} | |||

| {{History of Pakistan}} | |||

| {{Culture of Pakistan}}{{History of South Asia}} |

{{History of Pakistan}} | ||

| {{Culture of Pakistan}} | |||

| {{History of South Asia}} | |||

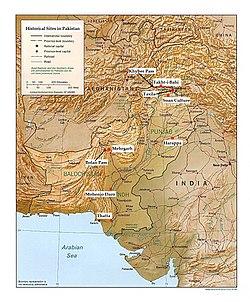

| ] | |||

| The '''History of Pakistan''' prior to its ] in 1947 spans several ] and covers a vast geographical area known as the Greater Indus region.<ref>{{Cite book |last=McIntosh |first=Jane |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F6iBAAAAMAAJ&q=Greater+Indus+Valley |title=The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives |date=2008 |publisher=Bloomsbury Academic |isbn=978-1-57607-907-2 |language=en}}</ref> ] modern humans arrived in what is now Pakistan between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=James |first1=Hannah V. A. |last2=Petraglia |first2=Michael D. |date=2005 |title=Modern Human Origins and the Evolution of Behavior in the Later Pleistocene Record of South Asia |url=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/444365 |journal=Current Anthropology |language=en |volume=46 |issue=S5 |pages=S3–S27 |doi=10.1086/444365 |hdl=11858/00-001M-0000-002B-0DBC-F |issn=0011-3204|hdl-access=free }}</ref> ], dating as far back as 2.1 million years, have been discovered in the ] of northern Pakistan, indicating early ] activity in the region.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Dennell |first1=R.W. |last2=Rendell |first2=H. |last3=Hailwood |first3=E. |date=1988 |title=Early tool-making in Asia: two-million-year-old artefacts in Pakistan |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0003598X00073555/type/journal_article |journal=Antiquity |language=en |volume=62 |issue=234 |pages=98–106 |doi=10.1017/S0003598X00073555 |issn=0003-598X}}</ref> The earliest known human remains in Pakistan are dated between 5000 BCE and 3000 BCE.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Oldest human remains found in Pakistan |url=https://www.rockartmuseum.com/oldest-human-remains-pakistan/#:~:text=At%20present%2C%20the%20oldest%20human,5000%20BCE%20to%203000%20BCE. |website=Rock Art Museum}}</ref> By around 7000 BCE, early human settlements began to emerge in Pakistan, leading to the development of urban centres such as ], one of the oldest in human history.<ref name="Mehrgarh">Hirst, K. Kris. 2005. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170118071157/http://archaeology.about.com/od/mterms/g/mehrgarh.htm|date=18 January 2017}}. '' Guide to Archaeology''</ref><ref name="whc.unesco.org2">UNESCO World Heritage. 2004. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181226013816/http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/1876/|date=26 December 2018}}. ''Archaeological Site of Mehrgarh''</ref> By 4500 BCE, the ] evolved, which flourished between 2500 BCE and 1900 BCE along the ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Asrar |first=Shakeeb |title=How British India was divided |url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/8/14/how-india-pakistan-and-bangladesh-were-formed |access-date=2024-05-01 |website=Al Jazeera |language=en}}</ref> The region that now constitutes ] served both as the ] of a major ancient civilization and as a strategic gateway connecting ] with ] and the ].<ref name="Srinivasan2007">{{citation|last=Neelis|first=Jason|editor=Srinivasan, Doris |title=On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kuṣāṇa World|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dCz8NczNbcMC&pg=PA55|year=2007|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-90-04-15451-3|pages=55–94|chapter=Passages to India: Śaka and Kuṣāṇa migrations in historical contexts}} Quote: "Numerous passageways through the northwestern frontiers of the Indian subcontinent in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan served as migration routes to South Asia from the Iranian plateau and the Central Asian steppes. Prehistoric and protohistoric exchanges across the ], ], and Himalaya ranges demonstrate earlier precedents for routes through the high mountain passes and river valleys in later historical periods. Typological similarities between Northern Neolithic sites in Kashmir and Swat and sites in the Tibetan plateau and northern China show that 'Mountain chains have often integrated rather than isolated peoples.' Ties between the trading post of ] in ] (northeastern Afghanistan) and the lower ] provide evidence for long-distance commercial networks and 'polymorphous relations' across the Hindu Kush until c. 1800 B.C.' The ] (BMAC) may have functioned as a 'filter' for the introduction of ] to the northwestern Indian subcontinent, although routes and chronologies remain hypothetical. (page 55)"</ref><ref name="Marshall2013">{{citation|last=Marshall|first=John|title=A Guide to Taxila|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JEMbH2aDO0UC&pg=PA1|year=2013|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-61544-1|pages=1–|orig-date=1960}} Quote: "Here also, in ancient days, was the meeting-place of three great trade-routes, one, from Hindustan and Eastern India, which was to become the `royal highway' described by ] as running from ] to the north-west of the ]; the second from Western Asia through ], ] and ] and so across the Indus at ] to Taxila; and the third from Kashmir and Central Asia by way of the ] valley and ] to ] and so down the ] valley. These three trade-routes, which carried the bulk of the traffic passing by land between India and Central and Western Asia, played an all-important part in the history of Taxila. (page 1)"</ref> | |||

| Situated on the first coastal migration route of '']'' out of Africa, the region was inhabited early by modern humans.<ref name="QamarAyub2002">{{cite journal|last1=Qamar|first1=Raheel|last2=Ayub|first2=Qasim|last3=Mohyuddin|first3=Aisha|last4=Helgason|first4=Agnar|last5=Mazhar|first5=Kehkashan|last6=Mansoor|first6=Atika|last7=Zerjal|first7=Tatiana|last8=Tyler-Smith|first8=Chris|last9=Mehdi|first9=S. Qasim|title=Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in Pakistan|journal=The American Journal of Human Genetics|volume=70|issue=5|year=2002|pages=1107–1124|issn=0002-9297|doi=10.1086/339929|pmid=11898125|pmc=447589}}</ref><ref name="DennellPorr2014">{{citation|last=Clarkson|first=Christopher |editor=Dennell, Robin |editor2=Porr, Martin |title=Southern Asia, Australia and the Search for Human Origins|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DuWfAgAAQBAJ|year=2014|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-01785-6|pages=76–89|chapter=East of Eden: Founder Effects and Archaeological Signature of Modern Human Dispersal}} Quote: "The record from South Asia (Pakistan, India and Sri Lanka) has been pivotal in discussions of the archaeological signature of early modern humans east of Africa because of the well-excavated and well-dated sites that have recently been reported in this region and because of the central role South Asia played in early population expansion and dispersals to the east. Genetic studies have revealed that India was the gateway to subsequent colonisation of Asia and Australia and saw the first major population expansion of modern human populations anywhere outside of Africa. South Asia therefore provides a crucial stepping-scone in early modern migration to Southeast Asia and Oceania. (pages 81–2)"</ref> The 9,000-year history of village life in South Asia traces back to the ] (7000–4300 ]) site of Mehrgarh in Pakistan,<ref name=coningham-young-1>{{Citation | last1 =Coningham | first1 =Robin |author1-link=Robin Coningham | last2 =Young | first2 =Ruth | year =2015 | title =The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE – 200 CE | publisher =Cambridge University Press}} Quote: ""Mehrgarh remains one of the key sites in South Asia because it has provided the earliest known undisputed evidence for farming and pastoral communities in the region, and its plant and animal material provide clear evidence for the ongoing manipulation, and domestication, of certain species. Perhaps most importantly in a South Asian context, the role played by zebu makes this a distinctive, localised development, with a character completely different to other parts of the world. Finally, the longevity of the site, and its articulation with the neighbouring site of Nausharo (c. 2800—2000 BCE), provides a very clear continuity from South Asia's first farming villages to the emergence of its first cities (Jarrige, 1984)."</ref><ref name=fisher1>{{citation|last=Fisher|first=Michael H.|title=An Environmental History of India: From Earliest Times to the Twenty-First Century|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kZVuDwAAQBAJ|year=2018|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-11162-2}} Quote: "page 33: "The earliest discovered instance in India of well-established, settled agricultural society is at Mehrgarh in the hills between the Bolan Pass and the Indus plain (today in Pakistan) (see Map 3.1). From as early as 7000 BCE, communities there started investing increased labor in preparing the land and selecting, planting, tending, and harvesting particular grain-producing plants. They also domesticated animals, including sheep, goats, pigs, and oxen (both humped zebu and unhumped ). Castrating oxen, for instance, turned them from mainly meat sources into domesticated draft-animals as well."</ref><ref name=dyson1>{{citation|last=Dyson|first=Tim|title=A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3TRtDwAAQBAJ|year=2018|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-882905-8}}, Quote: "(p 29) "The subcontinent's people were hunter-gatherers for many millennia. There were very few of them. Indeed, 10,000 years ago there may only have been a couple of hundred thousand people, living in small, often isolated groups, the descendants of various 'modern' human incomers. Then, perhaps linked to events in Mesopotamia, about 8,500 years ago agriculture emerged in Baluchistan."</ref> and the 5,000-year history of urban life in South Asia to the various sites of the ], including ] and ].<ref name="AllchinAllchin1982">{{citation|last1=Allchin|first1=Bridget|last2=Allchin|first2=Raymond|title=The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r4s-YsP6vcIC&pg=PA131|year=1982|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-28550-6|page=131}}Quote: "During the second half of the fourth and early part of the third millennium B.C., a new development begins to become apparent in the greater Indus system, which we can now see to be a formative stage underlying the Mature Indus of the middle and late third millennium. This development seems to have involved the whole Indus system, and to a lesser extent the Indo-Iranian borderlands to its west, but largely left untouched the subcontinent east of the Indus system. (page 81)"</ref><ref name="DalesKenoyer1986">{{citation|last1=Dales|first1=George|last2=Kenoyer|first2=Jonathan Mark|last3=Alcock|first3=Leslie|title=Excavations at Mohenjo Daro, Pakistan: The Pottery, with an Account of the Pottery from the 1950 Excavations of Sir Mortimer Wheeler|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4iew_THp8foC&pg=PA4|year=1986|publisher=UPenn Museum of Archaeology|isbn=978-0-934718-52-3|page=4}}</ref> | |||

| {{about|the history of the ] before 1947 | |||

| |the history of Pakistan after 1947 | |||

| |History of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan}} | |||

| {{History of Pakistan}} | |||

| {{Culture of Pakistan}}{{History of South Asia}} | |||

| The '''history of Pakistan''' encompasses the history of the region constituting modern-day ], which is intertwined with the history of the broader ] and the surrounding regions of ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.dawn.com/news/1312059|title=Pakistan: The lesser-known histories of an ancient land}}</ref> ] are thought to have arrived on the Pakistan between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago.<ref name="PetragliaAllchin">{{cite book |author1=Michael D. Petraglia |author2=Bridget Allchin |author-link2=Bridget Allchin |title=The Evolution and History of Human Populations in South Asia: Inter-disciplinary Studies in Archaeology, Biological Anthropology, Linguistics and Genetics |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Qm9GfjNlnRwC&pg=PA6#v=onepage |publisher=Springer Science & Business Media |pages=6 |isbn=978-1-4020-5562-1|date=22 May 2007 }}</ref> Settled life which involves the transition from ] to ] and ], began in Pakistan around 7,000 BCE. The ] and ] rapidly followed by that of goats, sheep, and cattle, has been documented at ], ].<ref name="Wright2009-p=44">{{citation|last=Wright|first=Rita P.|authorlink=Rita P. Wright|title=The Ancient Indus: Urbanism, Economy, and Society|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fwgFPQAACAAJ&pg=PA44|year=2009|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-57652-9|pages=44, 51}}</ref> By 4,500 BCE, settled life had become more widely prevalent,<ref name="Wright2009-p=44"/> and eventually evolved into the ],<ref name="coppa">{{cite journal |last=Coppa|first=A.|author2=L. Bondioli |author3=A. Cucina |author4=D. W. Frayer |author5=C. Jarrige |author6=J. F. Jarrige |author7=G. Quivron |author8=M. Rossi |author9=M. Vidale |author10=R. Macchiarelli |title=Palaeontology: Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry|journal=Nature|volume=440|pages=755–756|doi=10.1038/440755a |pmid=16598247 |issue=7085|year=2006|bibcode=2006Natur.440..755C}}</ref> an early civilization of the ] which was larger in land area than both of its contemporaries ] and ] combined.<ref name="possehl">{{cite journal|last=Possehl|first=G. L.|authorlink=Gregory Possehl|date=October 1990|title=Revolution in the Urban Revolution: The Emergence of Indus Urbanization|journal=Annual Review of Anthropology|volume=19|issue=1|pages=261–282|doi=10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.001401|url=http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/toc/anthro/19/1?cookieSet=1|accessdate=6 May 2007}}</ref><ref name="asaw">{{cite book|last=Kenoyer|first=Jonathan Mark|author2=Kimberley Heuston|title=The Ancient South Asian World|publisher=]|date=May 2005|isbn=978-0-19-517422-9|url=http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/HistoryWorld/Ancient/Other/~~/dmlldz11c2EmY2k9OTc4MDE5NTE3NDIyOQ==|url-status=dead|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20121120093649/http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/HistoryWorld/Ancient/Other/~~/dmlldz11c2EmY2k9OTc4MDE5NTE3NDIyOQ%3D%3D|archivedate=20 November 2012|df=dmy-all}}</ref><ref name="shef">{{cite web |url=http://www.shef.ac.uk/archaeology/research/pakistan |title=Palaeolithic and Pleistocene of Pakistan|publisher=Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield|accessdate=1 December 2007}}</ref><ref name="murray">{{cite book|last=Murray |first=Tim |authorlink=Tim Murray (archaeologist)|title=Time and archaeology |publisher=Routledge|year=1999 |location=London; New York |page=84|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=k3z9iXo_Uq8C&pg=PP3|isbn=978-0-415-11762-3}}</ref> It flourished between 2,500 BCE and 1,900 BCE with the headquarters of ]<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.harappa.com/indus4/e1.html|title=Recent Indus Discoveries and Highlights from Excavations at Harappa 1998-2000|website=www.harappa.com|access-date=2019-03-31}}</ref> and ]<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.harappa.com/slideshows/mohenjo-daro|title=Mohenjo-daro!|website=www.harappa.com|access-date=2019-06-19}}</ref>, centred mainly in ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.harappa.com/slideshows/mohenjo-daro|title=Mohenjo-daro!|website=www.harappa.com|access-date=2019-05-18}}</ref> | |||

| Following the decline of the Indus valley civilization, ] moved into the ] from Central Asia originally from the ] in several ] in the ] (1500–500 BCE), bringing with them came their ] which fused with local culture.<ref name="White 2003 28">{{cite book |last=White |first=David Gordon |url=https://archive.org/details/kissyoginitantri00whit |title=Kiss of the Yogini |publisher=University of Chicago Press |year=2003 |isbn=978-0-226-89483-6 |location=Chicago |page= |url-access=limited}}</ref> The Indo-Aryans religious beliefs and practices from the ] and the native Harappan Indus beliefs of the former Indus Valley Civilisation eventually gave rise to Vedic culture and tribes.<ref>. Retrieved 12 May 2007.</ref>{{refn|Archaeological cultures identified with phases of Vedic culture include the ], the ], the ] and the ].{{sfn|Witzel|1989}}|group=note}} Most notable among them was ], which flourished at the crossroads of India, Central Asia, and the Middle East, connecting ] and absorbing cultural influences from diverse civilizations.<ref>Kurt A. Behrendt (2007), , pp.4—5, 91</ref> The initial early Vedic culture was a tribal, ] society centred in the Indus Valley, of what is today Pakistan. During this period the ], the oldest ] of ], were composed.{{refn|The precise time span of the period is uncertain. ] and ] evidence indicates that the ], the oldest of the Vedas, was composed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period.<ref name="Oberlies p. 158">Oberlies (1998:155) gives an estimate of 1100 BCE for the youngest hymns in book 10. Estimates for a ''terminus post quem'' of the earliest hymns are more uncertain. Oberlies (p. 158) based on 'cumulative evidence' sets wide range of 1700–1100</ref>|group=note}} | |||

| The history of ] for the period preceding the country's creation in ]<ref>Pakistan was created as the ] on 14 August 1947 after the end of ] in, and ] of ].</ref> is shared with those of ], ], and ]. Spanning the western expanse of the ] and the eastern borderlands of the ], the region of present-day Pakistan served both as the fertile ground of a major civilization and as the gateway of South Asia to ] and the ].<ref name="Srinivasan2007">{{citation|last=Neelis|first=Jason|editor=Srinivasan, Doris |title=On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kuṣāṇa World|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dCz8NczNbcMC&pg=PA55|year=2007|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-90-04-15451-3|pages=55–94|chapter=Passages to India: Śaka and Kuṣāṇa migrations in historical contexts}} Quote: "Numerous passageways through the northwestern frontiers of the Indian subcontinent in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan served as migration routes to South Asia from the Iranian plateau and the Central Asian steppes. Prehistoric and protohistoric exchanges across the ], ], and Himalaya ranges demonstrate earlier precedents for routes through the high mountain passes and river valleys in later historical periods. Typological similarities between Northern Neolithic sites in Kashmir and Swat and sites in the Tibetan plateau and northern China show that 'Mountain chains have often integrated rather than isolated peoples.' Ties between the trading post of ] in ] (northeastern Afghanistan) and the lower ] provide evidence for long-distance commercial networks and 'polymorphous relations' across the Hindu Kush until c. 1800 B.C.' The ] (BMAC) may have functioned as a 'filter' for the introduction of ] to the northwestern Indian subcontinent, although routes and chronologies remain hypothetical. (page 55)"</ref><ref name="Marshall2013">{{citation|last=Marshall|first=John|title=A Guide to Taxila|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JEMbH2aDO0UC&pg=PA1|year=2013|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-61544-1|pages=1–|origyear=1960}} Quote: "Here also, in ancient days, was the meeting-place of three great trade-routes , one, from Hindustan and Eastern India, which was to become the `royal highway' described by ] as running from ] to the north-west of the ]; the second from Western Asia through ], ] and ] and so across the Indus at ] to Taxila; and the third from Kashmir and Central Asia by way of the ] valley and ] to ] and so down the ] valley. These three trade-routes, which carried the bulk of the traffic passing by land between India and Central and Western Asia, played an all-important part in the history of Taxila. (page 1)"</ref> | |||

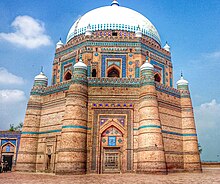

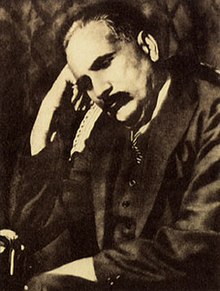

| The ensuing millennia saw the region of present-day Pakistan absorb many influences represented among others in the ancient, mainly ]-], sites of ], and ], the 14th-century ]-]i monuments of ], and the 17th-century ] monuments of ]. In the first half of the 19th century, the region was appropriated by the ], followed, after 1857, by 90 years of direct ], and ending with the creation of Pakistan in 1947, through the efforts, among others, of its future national poet ] and its founder, ]. Since then, the country has experienced both civilian democratic and military rule, resulting in periods of significant economic and military growth as well as those of instability; significant during the latter, was the 1971 ] of ] as the new nation of ].{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} | |||

| Situated on the first coastal migration route of '']'' out of Africa, the region was inhabited early by modern humans.<ref name="QamarAyub2002">{{cite journal|last1=Qamar|first1=Raheel|last2=Ayub|first2=Qasim|last3=Mohyuddin|first3=Aisha|last4=Helgason|first4=Agnar|last5=Mazhar|first5=Kehkashan|last6=Mansoor|first6=Atika|last7=Zerjal|first7=Tatiana|last8=Tyler-Smith|first8=Chris|last9=Mehdi|first9=S. Qasim|title=Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in Pakistan|journal=The American Journal of Human Genetics|volume=70|issue=5|year=2002|pages=1107–1124|issn=0002-9297|doi=10.1086/339929|pmid=11898125|pmc=447589}}</ref><ref name="DennellPorr2014">{{citation|last=Clarkson|first=Christopher |editor=Dennell, Robin |editor2=Porr, Martin |title=Southern Asia, Australia and the Search for Human Origins|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DuWfAgAAQBAJ|year=2014|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-01785-6|pages=76–89|chapter=East of Eden: Founder Effects and Archaeological Signature of Modern Human Dispersal}} Quote: "The record from South Asia (Pakistan, India and Sri Lanka) has been pivotal in discussions of the archaeological signature of early modern humans east of Africa because of the well-excavated and well-dated sites that have recently been reported in this region and because of the central role South Asia played in early population expansion and dispersals to the east. Genetic studies have revealed that India was the gateway to subsequent colonisation of Asia and Australia and saw the first major population expansion of modern human populations anywhere outside of Africa. South Asia therefore provides a crucial stepping-scone in early modern migration to Southeast Asia and Oceania. (pages 81–2)"</ref> The 9,000-year history of village life in South Asia traces back to the ] (7000–4300 ]) site of ] in Pakistan,<ref name=coningham-young-1>{{Citation | last1 =Coningham | first1 =Robin |author1link=Robin Coningham | last2 =Young | first2 =Ruth | year =2015 | title =The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE – 200 CE | publisher =Cambridge University Press}} Quote: ""Mehrgarh remains one of the key sites in South Asia because it has provided the earliest known undisputed evidence for farming and pastoral communities in the region, and its plant and animal material provide clear evidence for the ongoing manipulation, and domestication, of certain species. Perhaps most importantly in a South Asian context, the role played by zebu makes this a distinctive, localised development, with a character completely different to other parts of the world. Finally, the longevity of the site, and its articulation with the neighbouring site of Nausharo (c. 2800—2000 BCE), provides a very clear continuity from South Asia's first farming villages to the emergence of its first cities (Jarrige, 1984)."</ref><ref name=fisher1>{{citation|last=Fisher|first=Michael H.|title=An Environmental History of India: From Earliest Times to the Twenty-First Century|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kZVuDwAAQBAJ|year=2018|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-107-11162-2}} Quote: "page 33: "The earliest discovered instance in India of well-established, settled agricultural society is at Mehrgarh in the hills between the Bolan Pass and the Indus plain (today in Pakistan) (see Map 3.1). From as early as 7000 BCE, communities there started investing increased labor in preparing the land and selecting, planting, tending, and harvesting particular grain-producing plants. They also domesticated animals, including sheep, goats, pigs, and oxen (both humped zebu and unhumped ). Castrating oxen, for instance, turned them from mainly meat sources into domesticated draft-animals as well."</ref><ref name=dyson1>{{citation|last=Dyson|first=Tim|title=A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3TRtDwAAQBAJ|year=2018|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-882905-8}}, Quote: "(p 29) "The subcontinent's people were hunter-gatherers for many millennia. There were very few of them. Indeed, 10,000 years ago there may only have been a couple of hundred thousand people, living in small, often isolated groups, the descendants of various 'modern' human incomers. Then, perhaps linked to events in Mesopotamia, about 8,500 years ago agriculture emerged in Baluchistan."</ref> and the 5,000-year history of urban life in South Asia to the various sites of the ], including ] and ].<ref name="AllchinAllchin1982">{{citation|last1=Allchin|first1=Bridget|last2=Allchin|first2=Raymond|title=The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r4s-YsP6vcIC&pg=PA131|year=1982|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-28550-6|page=131}}Quote: "During the second half of the fourth and early part of the third millennium B.C., a new development begins to become apparent in the greater Indus system, which we can now see to be a formative stage underlying the Mature Indus of the middle and late third millennium. This development seems to have involved the whole Indus system, and to a lesser extent the Indo-Iranian borderlands to its west, but largely left untouched the subcontinent east of the Indus system. (page 81)"</ref><ref name="DalesKenoyer1986">{{citation|last1=Dales|first1=George|last2=Kenoyer|first2=Jonathan Mark|last3=Alcock|first3=Leslie|title=Excavations at Mohenjo Daro, Pakistan: The Pottery, with an Account of the Pottery from the 1950 Excavations of Sir Mortimer Wheeler|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4iew_THp8foC&pg=PA4|year=1986|publisher=UPenn Museum of Archaeology|isbn=978-0-934718-52-3|page=4}}</ref> | |||

| The ensuing millennia saw the region of present-day Pakistan absorb many influences—represented among others in the ancient ] sites of ], and ], the 14th-century ]-]i monuments of ], and the 17th-century ] monuments of ]. In the first half of the 19th century, the region was appropriated by the ], followed, after 1857, by 90 years of direct ], and ending with the creation of Pakistan in 1947, through the efforts, among others, of its future national poet ] and its founder, ]. Since then, the country has experienced both civilian-democratic and military rule, resulting in periods of significant economic and military growth as well those of instability; significant during the latter, was the ], in 1971, of ] as the new nation of ]. | |||

| == History by region == | |||

| {{main|Timeline of Pakistani history}} | |||

| {{columns-list|colwidth=30em| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| == Prehistory == | == Prehistory == | ||

| === Paleolithic period === | === Paleolithic period === | ||

| The ] is archaeological culture of the ], ]. It is named after the ] in the Sivalik Hills, near modern-day ] and is dated between c.774,000 and c.11,700 BCE.<ref name="murray">{{cite book |last=Murray |first=Tim |author-link=Tim Murray (archaeologist) |title=Time and Archaeology |url=https://archive.org/details/timearchaeology00murr |url-access=limited |publisher=Routledge |year=1999 |location=London | page= |isbn=978-0-415-11762-3}}</ref> | |||

| === Neolithic period === | === Neolithic period === | ||

| {{Main|Mehrgarh}} | {{Main|Mehrgarh}} | ||

| ] is an important ] site discovered in 1974, which shows early evidence of farming and herding,<ref>Hirst, K. Kris. 2005. . ''Guide to Archaeology''</ref> and dentistry.<ref name="coppa"/> The site dates back to 7000–5500 ] |

] is an important ] site discovered in 1974, which shows early evidence of farming and herding,<ref>Hirst, K. Kris. 2005. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170118071157/http://archaeology.about.com/od/mterms/g/mehrgarh.htm |date=18 January 2017 }}. ''Guide to Archaeology''</ref> and dentistry.<ref name="coppa">{{cite journal |last=Coppa|first=A.|author2=L. Bondioli |author3=A. Cucina |author4=D. W. Frayer |author5=C. Jarrige |author6=J. F. Jarrige |author7=G. Quivron |author8=M. Rossi |author9=M. Vidale |author10=R. Macchiarelli |title=Palaeontology: Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry|journal=Nature|volume=440|pages=755–756|doi=10.1038/440755a |pmid=16598247 |issue=7085|year=2006|bibcode=2006Natur.440..755C|s2cid=6787162}}</ref> The site dates back to 7000–5500 ] and is located on the Kachi Plain of ]. The residents of Mehrgarh lived in mud brick houses, stored grain in granaries, fashioned tools from ], cultivated barley, wheat, ]s and dates, and herded sheep, goats and cattle. As the civilization progressed (5500–2600 BCE) residents began to engage in crafts, including ], ], bead production, and ]. The site was occupied continuously until 2600 BCE,<ref>] 1996. "Mehrgarh." ''Oxford Companion to Archaeology'', edited by Brian Fagan. Oxford University Press, Oxford</ref> when climatic changes began to occur. Between 2600 and 2000 BCE, region became more arid and Mehrgarh was abandoned in favor of the Indus Valley,<ref name=guimet> | ||

| {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070928044049/http://www.guimet.fr/Indus-and-Mehrgarh-archaeological |date=28 September 2007 }} |

{{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070928044049/http://www.guimet.fr/Indus-and-Mehrgarh-archaeological |date=28 September 2007 }}, Musée National des Arts Asiatiques – Guimet | ||

| </ref> where a ] was in the early stages of development.<ref> | </ref> where a ] was in the early stages of development.<ref> | ||

| Chandler, Graham. 1999. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070218235318/http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/199905/traders.of.the.plain.htm |date=18 February 2007 }} ''Saudi Aramco World''. | Chandler, Graham. 1999. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070218235318/http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/199905/traders.of.the.plain.htm |date=18 February 2007 }} ''Saudi Aramco World''. | ||

| </ref> | </ref> | ||

| ==Bronze age== | |||

| ===Indus Valley Civilisation=== | ===Indus Valley Civilisation=== | ||

| {{Main|Indus Valley Civilisation}} | {{Main|Indus Valley Civilisation}} | ||

| {{multiple image | {{multiple image | ||

| | align = | | align = | ||

| | direction = | | direction = | ||

| | width = | | width = | ||

| | header = ] | | header = ] | ||

| | total_width = 300 | | total_width = 300 | ||

| | perrow = 2 | | perrow = 2 | ||

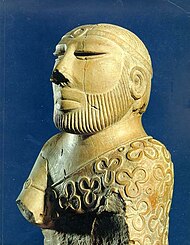

| | image1 = Mohenjo-daro Priesterkönig.jpeg | | image1 = Mohenjo-daro Priesterkönig.jpeg | ||

| | caption1 = The |

| caption1 = The ] sculpture is carved from ]. | ||

| | image2 = Shiva Pashupati.jpg | | image2 = Shiva Pashupati.jpg | ||

| | caption2 = The '']'' |

| caption2 = The '']'' | ||

| | image3 = Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daro.jpg | | image3 = Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daro.jpg | ||

| | caption3 = The ] of Mohenjo-daro |

| caption3 = The ] of Mohenjo-daro | ||

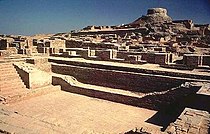

| | image4 = Mohenjodaro Sindh.jpeg | | image4 = Mohenjodaro Sindh.jpeg | ||

| | caption4 = Excavated ruins of the Great Bath at ] in ] |

| caption4 = Excavated ruins of the Great Bath at ] in ] | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| ] | |||

| The ] in the ] began around 3300 BCE with the Indus Valley Civilization.{{Sfn|Wright|2009|p=1}} Along with ] and ], it was one of three early civilizations of the ], and of the three the most widespread,{{Sfn|Wright| |

The ] in the ] began around 3300 BCE with the Indus Valley Civilization.{{Sfn|Wright|2009|p=1}} Along with ] and ], it was one of three early civilizations of the ], and of the three the most widespread,{{Sfn|Wright|2009|ps=: Quote: "The Indus civilization is one of three in the 'Ancient East' that, along with ] and ], was a cradle of early civilization in the Old World (Childe 1950). Mesopotamia and Egypt were longer lived, but coexisted with Indus civilization during its florescence between 2600 and 1900 B.C. Of the three, the Indus was the most expansive, extending from today's northeast Afghanistan to Pakistan and India."}} covering an area of 1.25 million km<sup>2</sup>.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Blanc De La|first1=Paul|title=Indus Epigraphic Perspectives: Exploring Past Decipherment Attempts & Possible New Approaches 2013 Pg 11|url=http://www.ruor.uottawa.ca/bitstream/10393/26166/1/Leblanc_Paul_2013_thesis.pdf|website=University of Ottawa Research|publisher=University of Ottawa|access-date=11 August 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140904103021/http://ruor.uottawa.ca/bitstream/10393/26166/1/Leblanc_Paul_2013_thesis.pdf|archive-date=4 September 2014|url-status=dead}}</ref> It flourished in the basins of the ], in what is today the Pakistani provinces of ], ] and ], and along a system of perennial, mostly monsoon-fed, rivers that once coursed in the vicinity of the seasonal ] in parts of north-west India.{{Sfn|Wright|2009|p=1}} At its peak, the civilization hosted a population of approximately 5 million spread across hundreds of settlements extending as far as the ] to present-day southern and eastern ], and the ].<ref name="feuerstein">{{cite book|last=Feuerstein|first=Georg|author2=Subhash Kak |author3=David Frawley |title=In search of the cradle of civilization: new light on ancient India|publisher=Quest Books|location=Wheaton, Illinois|year=1995|page=147|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kbx7q0gxyTcC|isbn=978-0-8356-0720-9}}</ref> Inhabitants of the ancient Indus river valley, the Harappans, developed new techniques in metallurgy and handicraft (carneol products, seal carving), and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin. | ||

| The Mature Indus civilisation flourished from about 2600 to 1900 BCE, marking the beginning of urban civilisation in the Indus Valley. The civilisation included urban centres such as ], ] and ] as well as an offshoot called the ] (2500–2000 BCE) in southern Balochistan and was noted for its cities built of brick, roadside drainage system, and multi-storeyed houses. It is thought to have had some kind of municipal organisation as well. | The Mature Indus civilisation flourished from about 2600 to 1900 BCE, marking the beginning of urban civilisation in the Indus Valley. The civilisation included urban centres such as ], ] and ] as well as an offshoot called the ] (2500–2000 BCE) in southern Balochistan and was noted for its cities built of brick, roadside drainage system, and multi-storeyed houses. It is thought to have had some kind of municipal organisation as well. | ||

| During the ] of this civilisation, signs of a ] began to emerge, and by around 1700 BCE, most of the cities were abandoned. However, the Indus Valley Civilisation did not disappear suddenly, and some elements of the Indus Civilisation may have survived. ] of this region during the 3rd millennium BCE may have been the initial spur for the urbanisation associated with the civilisation, but eventually also reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilisation's demise, and to scatter its population eastward. The civilization collapsed around 1700 BCE, though the reasons behind its fall are still unknown. Through the excavation of the Indus cities and analysis of town planning and seals, it has been inferred that the Civilization had high level of sophistication in its town planning, arts, crafts, and trade. | During the ] of this civilisation, signs of a ] began to emerge, and by around 1700 BCE, most of the cities were abandoned. However, the Indus Valley Civilisation did not disappear suddenly, and some elements of the Indus Civilisation may have survived. ] of this region during the 3rd millennium BCE may have been the initial spur for the urbanisation associated with the civilisation, but eventually also reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilisation's demise, and to scatter its population eastward. The civilization collapsed around 1700 BCE, though the reasons behind its fall are still unknown. Through the excavation of the Indus cities and analysis of town planning and seals, it has been inferred that the Civilization had high level of sophistication in its town planning, arts, crafts, and trade.<ref>P. Biagi and E. Starnini 2021 - Indus Civilization. In Smith, C. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Springer Nature, Switzerland: 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1_3491-1</ref> | ||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Dates | |||

| ! colspan=2 | Phase | |||

| ! Era | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;" | 7000–5500 BCE | |||

| ! rowspan=2 | Pre-Harappan | |||

| | style="text-align:center;" | ] (aceramic Neolithic) | |||

| !| Early Food Producing Era | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;" | 5500–3300 BCE | |||

| | style="text-align:center;" | Mehrgarh II-VI (ceramic Neolithic) | |||

| ! rowspan=3 | Regionalisation Era<br /><small>c.4000-2500/2300 BCE (Shaffer){{sfn|Manuel|2010|p=149}}<br />c.5000–3200 BCE (Coningham & Young){{sfn|Coningham|Young|2015|p=145}}</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;" | 3300–2800 BCE | |||

| ! rowspan=2 | Early Harappan | |||

| | style="text-align:center;" | Harappan 1 (Ravi Phase; ]) | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| || 2800–2600 BCE | |||

| || Harappan 2 (Kot Diji Phase, Nausharo I, Mehrgarh VII) | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;" | 2600–2450 BCE | |||

| ! rowspan=3 | Mature Harappan<br />(Indus Valley Civilisation) | |||

| | style="text-align:center;" | Harappan 3A (Nausharo II) | |||

| ! rowspan=3 | Integration Era | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| || 2450–2200 BCE | |||

| || Harappan 3B | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| || 2200–1900 BCE | |||

| || Harappan 3C | |||

| |- | |||

| | style="text-align:center;" | 1900–1700 BCE | |||

| ! rowspan=2 | Late Harappan<br />(]);] | |||

| | style="text-align:center;" | Harappan 4 | |||

| ! rowspan=2 | Localisation Era | |||

| |- style="text-align:center;" | |||

| || 1700–1300 BCE | |||

| || Harappan 5 | |||

| |} | |||

| == {{anchor|Early history}} Early history – Iron Age == | |||

| == Early history – Iron Age == | |||

| ===Vedic period=== | ===Vedic period=== | ||

| {{Main|Vedic |

{{Main|Vedic period|Indo-Aryan Migration|Indo-Aryans|Vedas}} | ||

| {{Further|Sintashta culture}} | |||

| {{See also|Indo-Aryan Migration|Indo-Aryans|Vedas}} | |||

| ].]] | ].|left]] | ||

| The Vedic Period ({{circa|1500|500 BCE}}) is postulated to have formed during the 1500 BCE to 800 BCE. As Indo-Aryans migrated and settled into the Indus Valley, along with them came their distinctive religious traditions and practices which fused with local culture.<ref name="White 2003 28"/> The Indo-Aryans religious beliefs and practices from the ] and the native Harappan Indus beliefs of the former Indus Valley Civilisation eventually gave rise to Vedic culture and tribes.<ref>. Retrieved 12 May 2007.</ref>{{refn|group=note|Archaeological cultures identified with phases of Vedic culture include the ], the ], the ] and the ].{{sfn|Witzel|1989}}}} Early ] were a ] society centred in the ], organised into tribes rather than kingdoms, and primarily sustained by a ] way of life. During this period the ], the oldest ] of ], were composed.{{refn|group=note|The precise time span of the period is uncertain. ] and ] evidence indicates that the ], the oldest of the Vedas, was composed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period.<ref name="Oberlies p. 158">Oberlies (1998:155) gives an estimate of 1100 BCE for the youngest hymns in book 10. Estimates for a ''terminus post quem'' of the earliest hymns are more uncertain. Oberlies (p. 158) based on 'cumulative evidence' sets wide range of 1700–1100</ref>}} | |||

| ====Indus Valley==== | |||

| The Vedic Period ({{circa|1500|500 BCE}}) is postulated to have formed during the 1500 BCE to 800 BCE. As Indo-Aryans migrated and settled into the Indus Valley, along with them came their distinctive religious traditions and practices which fused with local culture.<ref name="White 2003 28">{{cite book|last=White|first=David Gordon|title=Kiss of the Yogini|year=2003|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|isbn=978-0-226-89483-6|page=28}}</ref> The Indo-Aryans religious beliefs and practices from the ] and the native Harappan Indus beliefs of the former Indus Valley Civilisation eventually gave rise to Vedic culture and tribes.<ref>. Retrieved 2007-05-12.</ref> {{refn|group=note|Archaeological cultures identified with phases of Vedic culture include the ], the ], the ] and the ].{{sfn|Witzel|1989}}}} The initial early Vedic culture was a tribal, ] society centered in the Indus Valley, of what is today Pakistan. During this period the ], the oldest ] of ], were composed.{{refn|group=note|The precise time span of the period is uncertain. ] and ] evidence indicates that the ], the oldest of the Vedas, was composed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period.<ref>Oberlies (1998:155) gives an estimate of 1100 BCE for the youngest hymns in book 10. Estimates for a ''terminus post quem'' of the earliest hymns are more uncertain. Oberlies (p. 158) based on 'cumulative evidence' sets wide range of 1700–1100</ref>}} | |||

| Several early tribes and kingdoms arose during this period and internecine military conflicts between these various tribes was common; as described in the ], which was being composed at this time, the most notable of such conflicts was the ]. This battle took place on the banks of the ] in the 14th century BC (1300 BCE). The battle was fought between the ] tribe and a confederation of ten tribes: | |||

| *''']''', centered in the ]-] region.{{citation needed|date=September 2017}} | |||

| *''']''', centered in ]. | |||

| *''']''', also called ''Swat culture'' and centered in the ] of present-day ]. | |||

| *''']''', centered in the ] region. | |||

| *''']''', centered in present-day ]. | |||

| *''']''', centered in upper Punjab, with its capital at ] | |||

| *''']''', a sub-clan of Kambojas | |||

| *''']''', centered in present-day ]. | |||

| *''']''', centered in the ]-] region.{{citation needed|date=September 2017}} | |||

| ==Ancient history== | |||

| === Achaemenid Empire === | === Achaemenid Empire === | ||

| {{Main|Achaemenid invasion of the Indus Valley}} | {{Main|Achaemenid invasion of the Indus Valley}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] representing the city of ] during the Achaemenid period]] | |||

| The main Vedic tribes remaining in the ] by 550 BC were the ''Kamboja'', ''Sindhu'', ''Taksas'' of Gandhara, the ''Madras'' and ''Kathas'' of the ], ''Mallas'' of the ] and ''Tugras'' of the ]. These several tribes and principalities fought against one another to such an extent that the Indus Valley no longer had one powerful Vedic tribal kingdom to defend against outsiders and to wield the warring tribes into one organized kingdom |

The main Vedic tribes remaining in the ] by 550 BC were the ''Kamboja'', ''Sindhu'', ''Taksas'' of Gandhara, the ''Madras'' and ''Kathas'' of the ], ''Mallas'' of the ] and ''Tugras'' of the ]. These several tribes and principalities fought against one another to such an extent that the Indus Valley no longer had one powerful Vedic tribal kingdom to defend against outsiders and to wield the warring tribes into one organized kingdom. King ] of ] was engaged in power struggles against his local rivals and as such the ] remained poorly defended. ] of the ] took advantage of the opportunity and planned for an invasion. The Indus Valley was fabled in Persia for its gold and fertile soil and conquering it had been a major objective of his predecessor ].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Petrie |first1=Cameron A. |last2=Magee |first2=Peter |title=Histories, epigraphy and authority: Achaemenid and indigenous control in Pakistan in the 1st millennium BC |url=https://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/bannu-archaeological-project/petrie2007_02.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110611053344/https://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/bannu-archaeological-project/petrie2007_02.pdf |archive-date=2011-06-11 |access-date=18 April 2024}}</ref> In 542 BC, Cyrus had led his army and conquered the Makran coast in southern ]. However, he is known to have campaigned beyond Makran (in the regions of ], ] and ]) and lost most of his army in the ''Gedrosian Desert'' (speculated today as the ]). | ||

| Histories, epigraphy and authority: Achaemenid and indigenous control in Pakistan in the 1st millennium BC {{Dead link|date=March 2019 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}{{dead link|date=April 2017|bot=InternetArchiveBot|fix-attempted=yes}} | |||

| </ref> In 542 BC, Cyrus had led his army and conquered the Makran coast in southern ]. However, he is known to have campaigned beyond Makran (in the regions of ], ] and ]) and lost most of his army in the ''Gedrosian Desert'' (speculated today as the ]). | |||

| In 518 BC, Darius led his army through the Khyber Pass and southwards in stages, eventually reaching the ] coast in Sindh by 516 BC. Under Persian rule, a system of centralized administration, with a bureaucratic system, was introduced into the Indus Valley for the first time. Provinces or "satrapy" were established with provincial capitals: | |||

| *'''] satrapy''', established 518 BC with its capital at ] (]). Gandhara Satrapy was established in the general region of the old Gandhara grave culture, in what is today ]. During Achaemenid rule, the ] alphabet, derived from the one used for Aramaic (the official language of Achaemenids), developed here and remained the national script of Gandhara until 200 AD. | |||

| *'''] satrapy''', established in 518 BC with its capital at ]. The satrapy was established in upper Punjab (presumably in the ] region). | |||

| *'''] satrapy''', established in 517 BC with its capital at ]. Arachosia was one of the larger provinces covering much of lower Punjab, southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa of modern-day Pakistan and Helmand province of what is today ]. The inhabitants of Arachosia were referred to as ''Paktyans'' by ethnicity, and that name may have been in reference to the ethnic Pax̌tūn (Pashtun) tribes. | |||

| *'''] satrapy''', established in 516 BC in what is today ]. Sattagydia is mentioned for the first time in the ] of Darius the Great as one of the provinces in revolt while the king was in Babylon. The revolt was presumably suppressed in 515 BC. The satrapy disappears from sources after 480 BC, possibly being mentioned by another name or included with other regions.<ref name="arch.cam.ac.uk"/> | |||

| *'''] satrapy''', established in 542 BC, covered much of the ] region of southern ]. It had been conquered much earlier by Cyrus The Great.<ref></ref> | |||

| Despite all this, there is no archaeological evidence of Achaemenid control over these region as not a single archaeological site that can be positively identified with the Achaemenid Empire has been found anywhere in Pakistan, including at ]. What is known about the easternmost satraps and borderlands of the Achaemenid Empire is alluded to in the ] inscriptions and from Greek sources such as the ''Histories'' of ] and the later ''Alexander Chronicles'' (Arrian, Strabo et al.). These sources list three Indus Valley tributaries or conquered territories that were subordinated to the Persian Empire and made to pay tributes to the Persian Kings: Gandhara, Sattagydia and Hindush.<ref name="arch.cam.ac.uk">{{cite web |url=http://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/bannu-archaeological-project/petrie2007_02.pdf |title=Microsoft Word - GS_Alexander_Arrian.doc |accessdate=4 April 2013 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120519044446/http://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/bannu-archaeological-project/petrie2007_02.pdf |archivedate=19 May 2012 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> | |||

| In 518 BC, Darius led his army through the Khyber Pass and southwards in stages, eventually reaching the ] coast in Sindh by 516 BC. Under Persian rule, a system of centralized administration, with a bureaucratic system, was introduced into the Indus Valley for the first time, establishing several ]ies: ] around the general region of Gandhara, ] around Punjab and Sindh, ], encompassing parts of present-day ], and ],<ref name="Iranicaarticle">{{cite encyclopedia|last=Schmitt|first=Rüdiger|title=Arachosia |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Iranica |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/arachosia |date=10 August 2011}}</ref> ] around the ] basin,<ref name="arch.cam.ac.uk" /> and ] covering much of the ] region of southern Balochistan.<ref></ref> | |||

| ===Ror dynasty=== | |||

| {{Main|Ror Dynasty}} | |||

| What is known about the easternmost satraps and borderlands of the Achaemenid Empire is alluded to in the ] inscriptions and from Greek sources such as the ''Histories'' of ] and the later ''Alexander Chronicles'' (Arrian, Strabo et al.). These sources list three Indus Valley tributaries or conquered territories that were subordinated to the Persian Empire and made to pay tributes to the Persian Kings.<ref name="arch.cam.ac.uk">{{cite web |url=http://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/bannu-archaeological-project/petrie2007_02.pdf |title=Microsoft Word - GS_Alexander_Arrian.doc |access-date=4 April 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120519044446/http://www.arch.cam.ac.uk/bannu-archaeological-project/petrie2007_02.pdf |archive-date=19 May 2012}}</ref> | |||

| The '''Ror dynasty''' ({{lang-sd|'''روهڙا راڄ'''}}) was a ] ] dynasty which ruled much of what is today ], ] and northwest ] in 450 BC.<ref>{{cite web|author=P L Kessler |url=http://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsFarEast/IndiaSindh.htm |title=Kingdoms of South Asia - Kingdoms of the Indus / Sindh |publisher=Historyfiles.co.uk |date=2018-02-22 |accessdate=2018-08-15}}</ref> The Rors ruled from ] and was built by ], a Ror Kshatriya. ] ] stories talk about exchanges of gifts between King Rudrayan of Roruka and King ] of ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.borobudur.tv/avadana_07.htm |title=Archived copy |accessdate=2015-12-08 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130603004232/http://www.borobudur.tv/avadana_07.htm |archivedate=3 June 2013 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> ], the Buddhist chronicle has said that Rori historically competed with ] in terms of political influence.<ref>"The Divyavadana (Tibetan version) reports: 'The Buddha is in Rajgriha. At this time there were two great cities in ]: ] and Roruka. When Roruka rises, Pataliputra declines; when Pataliputra rises, Roruka declines.' Here was Roruka of Sindh competing with the capital of the Magadha empire." Chapter 'Sindhu is divine', The Sindh Story, by K. R. Malkani from Karachi, Publisher: Sindhi Academy (1997), {{ISBN|81-87096-01-2}}</ref> Rori was wiped out in a major sand storm,<ref>Page 174, Alexander's campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan and the siege of the Brahmin town of Harmatelia, Volume 3 of Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta, by Pierre Herman Leonard Eggermont, Peeters Publishers, 1975, {{ISBN|90-6186-037-7}}, {{ISBN|978-90-6186-037-2}}</ref> which was recorded in both the ] Bhallatiya Jataka and ] annals. | |||

| ===Macedonian Empire=== | ===Macedonian Empire=== | ||

| {{Main|Indian campaign of Alexander the Great|Macedonian Empire}} | {{Main|Indian campaign of Alexander the Great|Macedonian Empire}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ], with ]]] | |||

| In 328 BC, ] of ] and now the king of Persia, had conquered much of the former Satraps of the ] up to ]. The remaining satraps lay in the Indus Valley, but Alexander ruled off invading the Indus until his forces were in complete control of the newly acquired satraps. In 327 BC, Alexander married ] (a princess of the former ]) to cement his relations with his new territories. Now firmly under Macedonian rule, Alexander was free to turn his attention to the Indus Valley. The rationale for the Indus campaign is usually said to be Alexander's desire to conquer the entire known world, which the Greeks thought ended around the vicinity of the River Indus. | |||

| By spring of 326 BC, Alexander began on his Indus expedition from Bactria, leaving behind 3500 horses and 10,000 soldiers. He divided his army into two groups. The larger force would enter the Indus Valley through the Khyber Pass, just as Darius had done 200 years earlier, while a smaller force under the personal command of Alexander entered through a northern route, possibly through ] or ] near ]. Alexander was commanding a group of shield-bearing guards, foot-companions, archers, Agrianians, and horse-javelin-men and led them against the tribes of the former Gandhara satrapy. | |||

| The first tribe they encountered were the ] tribe of the ], who initiated a fierce battle against Alexander, in which he himself was wounded in the shoulder by a dart. However, the Aspasioi eventually lost and 40,000 people were enslaved. Alexander then continued in a southwestern direction where he encountered the ] tribe of the ] & ] valleys in April 326 BC. The Assakenoi fought bravely and offered stubborn resistance to Alexander and his army in the cities of Ora, Bazira (]) and Massaga. So enraged was Alexander about the resistance put up by the Assakenoi that he killed the entire population of Massaga and reduced its buildings to rubble – similar slaughters followed in Ora.<ref>{{cite book|title=History and Culture of Indian People, The Age of Imperial Unity, Foreign Invasion|author=Mukerjee, R. K.|page=46}}</ref> A similar slaughter then followed at Ora, another stronghold of the Assakenoi. The stories of these slaughters reached numerous Assakenians, who began fleeing to Aornos, a hill-fort located between ] and ]. Alexander followed close behind their heels and besieged the strategic hill-fort, eventually capturing and destroying the fort and killing everyone inside. The remaining smaller tribes either surrendered or like the Astanenoi tribe of ] (]) were quickly neutralized where 38,000 soldiers and 230,000 oxen were captured by Alexander.<ref>Curtius in McCrindle, p. 192, J. W. McCrindle; ''History of Punjab'', Vol I, 1997, p 229, Punjabi University, Patiala (editors): Fauja Singh, L. M. Joshi; ''Kambojas Through the Ages'', 2005, p. 134, Kirpal Singh.</ref> Eventually Alexander's smaller force would meet with the larger force which had come through the Khyber Pass met at ]. With the conquest of Gandhara complete, Alexander switched to strengthening his military supply line, which by now stretched dangerously vulnerable over the ] back to ] in Bactria. | |||

| In the winter of 327 BC, Alexander invited all the chieftains in the remaining five Achaemenid satraps to submit to his authority. ], then ruler of Taxila in the former ] satrapy complied, but the remaining tribes and clans in the former satraps of Gandhara, Arachosia, Sattagydia and Gedrosia rejected Alexander's offer. By spring of 326 BC, Alexander began on his Indus expedition from Bactira, leaving behind 3500 horses and 10,000 soldiers. He divided his army into two groups. The larger force would enter the Indus Valley through the ], just as Darius had done 200 years earlier, while a smaller force under the personal command of Alexander entered through a northern route, possibly through ] or ] near ]. Alexander was commanding a group of shield-bearing guards, foot-companions, archers, Agrianians, and horse-javelin-men and led them against the tribes of the former Gandhara satrapy. | |||

| After conquering Gandhara and solidifying his supply line back to Bactria, Alexander combined his forces with the King Ambhi of Taxila and crossed the River Indus in July 326 BC to begin the Archosia (Punjab) campaign. His first resistance would come at the ] near ] against King ] of the ] tribe. The famous ] (]) between Alexander (with Ambhi) and Porus would be the last major battle fought by him. After defeating Porus, his battle weary troops refused to advance into India<ref name="Plutarch1994">{{cite book|last1=Plutarch|first1=Mestrius|translator-last=Perrin|translator-first=Bernadotte|title=Plutarch's Lives|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oJhpAAAAMAAJ|access-date=23 May 2016 |volume=7|year=1994|publisher=Heinemann|location=London|isbn=978-0-674-99110-1|chapter=Chapter LXII}}</ref> to engage the army of ] and its vanguard of trampling elephants. Alexander, therefore proceeded south-west along the Indus Valley.<ref name="PlutarchLXIII">{{cite book|last1=Plutarch|first1=Mestrius|translator-last=Perrin|translator-first=Bernadotte|title=Plutarch's Lives|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oJhpAAAAMAAJ|access-date=23 May 2016|volume=7|year=1994|publisher=Heinemann|location=London|isbn=978-0-674-99110-1|chapter=Chapter LXIII}}</ref> Along the way, he engaged in several battles with smaller kingdoms in ] and ], before marching his army westward across the ] desert towards what is now ]. In crossing the desert, Alexander's army took enormous casualties from hunger and thirst, but fought no human enemy. They encountered the "Fish Eaters", or Ichthyophagi, primitive people who lived on the Makran coast, who had matted hair, no fire, no metal, no clothes, lived in huts made of whale bones, and ate raw seafood. | |||

| The first tribe they encountered were the ] tribe of the ], who initiated a fierce battle against Alexander, in which he himself was wounded in the shoulder by a dart. However, the Aspasioi eventually lost and 40,000 people were enslaved. Alexander then continued in a southwestern direction where he encountered the ] tribe of the ] & ] valleys in April 326 BC. The Assakenoi fought bravely and offered stubborn resistance to Alexander and his army in the cities of Ora, Bazira (]) and Massaga. So enraged was Alexander about the resistance put up by the Assakenoi that he killed the entire population of Massaga and reduced its buildings to rubble – similar slaughters followed in Ora.<ref>{{cite book|title=History and Culture of Indian People, The Age of Imperial Unity, Foreign Invasion|author=Mukerjee, R. K.|page=46}}</ref> A similar slaughter then followed at Ora, another stronghold of the Assakenoi. The stories of these slaughters reached numerous Assakenians, who began fleeing to Aornos, a hill-fort located between ] and ]. Alexander followed close behind their heels and besieged the strategic hill-fort, eventually capturing and destroying the fort and killing everyone inside. The remaining smaller tribes either surrendered or like the ] tribe of ](]) were quickly neutralized where 38,000 soldiers and 230,000 oxen were captured by Alexander.<ref>Curtius in McCrindle, p. 192, J. W. McCrindle; ''History of Punjab'', Vol I, 1997, p 229, Punjabi University, Patiala (editors): Fauja Singh, L. M. Joshi; ''Kambojas Through the Ages'', 2005, p. 134, Kirpal Singh.</ref> Eventually Alexander's smaller force would meet with the larger force which had come through the Khyber Pass met at ]. With the conquest of Gandhara complete, Alexander switched to strengthening his military supply line, which by now stretched dangerously vulnerable over the ] back to ] in Bactria. | |||

| After conquering Gandhara and solidifying his supply line back to Bactria, Alexander combined his forces with the King Ambhi of Taxila and crossed the River Indus in July 326 BC to begin the Archosia (Punjab) campaign. His first resistance would come at the ] near ] against King ] of the ] tribe. The famous ] (]) between Alexander (with Ambhi) and Porus would be the last major battle fought by him. After defeating ], his battle weary troops refused to advance into India<ref name="Plutarch1994">{{cite book|last1=Plutarch|first1=Mestrius|last2=Perrin|first2=Bernadotte|title=Plutarch's Lives|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oJhpAAAAMAAJ|accessdate=23 May 2016|edition=Translation (1919)|volume=Volume 7|year=1994|publisher=Heinemann|location=London|isbn=978-0-674-99110-1|chapter=Chapter LXII}}</ref> to engage the army of ] and its vanguard of trampling elephants. Alexander, therefore proceeded southwest along the Indus Valley.<ref name="PlutarchLXIII">{{cite book|last1=Plutarch|first1=Mestrius|last2=Perrin|first2=Bernadotte|title=Plutarch's Lives|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oJhpAAAAMAAJ|accessdate=23 May 2016|edition=Translation (1919)|volume=Volume 7|year=1994|publisher=Heinemann|location=London|isbn=978-0-674-99110-1|chapter=Chapter LXIII}}</ref> Along the way, he engaged in several battles with smaller kingdoms in ] and ], before marching his army westward across the ] desert towards what is now ]. In crossing the desert, Alexander's army took enormous casualties from hunger and thirst, but fought no human enemy. They encountered the "Fish Eaters", or Ichthyophagi, primitive people who lived on the Makran coast, who had matted hair, no fire, no metal, no clothes, lived in huts made of whale bones, and ate raw seafood. | |||

| Alexander founded several new settlements in ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ancientpakistan.info/pakistan-history-timeline/alexanders-empire/|title=Alexanders Empire – History of Ancient Pakistan}}</ref> and nominated officers as Satraps of the new provinces: | |||

| *In ''']''', ] was nominated to the position of Satrap by Alexander in 326 BC. | |||

| *In ''']''', Alexander nominated his officer ] as Satrap in 325 BC, a position he would hold for the next ten years. | |||

| *In ''']''', Alexander initially nominated ] as Satrap from 327 BC to 326 BC. In 326 BC, he nominated ] and Taxiles as joint-Satraps until 323 BC when ] resigned leaving Taxiles as Satrap until 321 BC. Porus of Jhelum then became Satrap of Punjab. | |||

| *In ''']''', ] was nominated as Satrap in 323 BC and remained so until 303 BC. | |||

| When Alexander died in 323 BCE, he left behind an expansive empire stretching from ] to the ]. The empire was put under the authority of ], and the territories were divided among Alexander's generals (the ]), who thereby became satraps of the new provinces. However, the Satraps of the Indus Valley largely remained under the same leaders while conflicts were brewing in ] and ]. | |||

| === Mauryan Empire === | === Mauryan Empire === | ||

| ]]] | |||

| {{Main|Maurya Empire|Greco-Bactrian Kingdom|Greco-Buddhism}} | {{Main|Maurya Empire|Greco-Bactrian Kingdom|Greco-Buddhism}} | ||

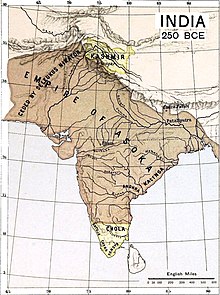

| ] under king ], c.250 BCE.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/cu31924022983567/page/n23/mode/1up|title=Historical atlas of India, for the use of high schools, colleges and private students|last=Joppen|first=Charles|date=1907|publisher=London; New York : Longmans, Green|others=Cornell University Library|pages=map 2}}</ref>]] | |||

| The Maurya Empire was a geographically extensive ] ] in ] based in ], having been founded by ] in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until 185 BCE.<ref name="Dyson2018-lead-maurya"> | |||

| Due to the internal conflicts of Alexanders generals, ] saw an opportunity to expand the Mauryan Empire from its Ganges Plain heartland by defeating ] one of the Mahajanpadas of that time towards the Indus Valley between 325 BCE to 303 BCE. At the same time, ] now ruler much of the Macedonian Empire was advancing from ] in order to establish his writ in the former Persian and Indus Valley provinces of Alexander. During this period, Chandragupta's mercenaries may have assassinated Satrap of Punjab Philip. They presumably also fought Eudemus, Porus and Taxiles of Punjab and Peithon of Sindh. In 316 BCE, both Eudemus and Peithon left Punjab and Sindh for Babylon, thus ending Macedonian rule. The Mauryan Empire now controlled Punjab and Sindh. As the ] expanded eastwards towards the Indus, it was becoming more difficult for Seleucus to assert control over the vast eastern domains. Seleucus invaded Punjab in 305 BC, confronting Chandragupta Maurya. It is said that Chandragupta fielded an army of 600,000 men and 9000 war elephants. After two years of war, Seleucus reached an agreement with Chandragupta, in which he gave his daughter in marriage to Chandragupta and exchanged his eastern provinces for a considerable force of 500 war elephants, which would play a decisive role at ] (301 BCE). Strabo, in his Geographica, wrote: | |||

| {{citation | |||

| |last=Dyson|first=Tim|title=A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3TRtDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA16|year=2018|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-882905-8|pages=16–17}} Quote: "Magadha power came to extend over the main cities and communication routes of the Ganges basin. Then, under Chandragupta Maurya (c.321–297 bce), and subsequently Ashoka his grandson, Pataliputra became the centre of the loose-knit Mauryan 'Empire' which during Ashoka's reign (c.268–232 bce) briefly had a presence throughout the main urban centres and arteries of the subcontinent, except for the extreme south."</ref> The Maurya Empire was centralized by the conquest of the ], and its capital city was located at ] (modern ]). Outside this imperial centre, the empire's geographical extent was dependent on the loyalty of military commanders who controlled the armed cities sprinkling it.<ref name="Ludden2013-lead-maurya"> | |||

| {{citation | |||

| |last=Ludden | |||

| |first=David|title=India and South Asia: A Short History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EbFHAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA29|year=2013|publisher=Oneworld Publications|isbn=978-1-78074-108-6|pages=29–30}} |quote=The geography of the Mauryan Empire resembled a spider with a small dense body and long spindly legs. The highest echelons of imperial society lived in the inner circle composed of the ruler, his immediate family, other relatives, and close allies, who formed a dynastic core. Outside the core, empire travelled stringy routes dotted with armed cities. Outside the palace, in the capital cities, the highest ranks in the imperial elite were held by military commanders whose active loyalty and success in war determined imperial fortunes. Wherever these men failed or rebelled, dynastic power crumbled. ... Imperial society flourished where elites mingled; they were its backbone, its strength was theirs. Kautilya's ''Arthasastra'' indicates that imperial power was concentrated in its original heartland, in old ''Magadha'', where key institutions seem to have survived for about seven hundred years, down to the age of the Guptas. Here, Mauryan officials ruled local society, but not elsewhere. In provincial towns and cities, officials formed a top layer of royalty; under them, old conquered royal families were not removed, but rather subordinated. In most ''janapadas'', the Mauryan Empire consisted of strategic urban sites connected loosely to vast hinterlands through lineages and local elites who were there when the Mauryas arrived and were still in control when they left.</ref>{{sfn|Hermann Kulke|2004|pp=xii, 448}}<ref>{{cite book | first1=Romila | last1=Thapar | title=A History of India, Volume 1 | publisher=Penguin Books | author-link=Romila Thapar | year=1990 | page=384 | isbn=0-14-013835-8}}</ref> During ]'s rule (ca. 268–232 BCE) the empire briefly controlled the major urban hubs and arteries of the ] excepting the deep south.<ref name="Dyson2018-lead-maurya"/> It declined for about 50 years after Ashoka's rule, and dissolved in 185 BCE with the assassination of Brihadratha by ] and foundation of the ] in Magadha. | |||

| Chandragupta Maurya raised an army, with the assistance of ], author of ],<ref>{{Cite book|title=India: A History|last=Keay|first=John|publisher=Grove Press|year=2000|isbn=978-0-8021-3797-5|pages=82}}</ref> and overthrew the ] in {{circa|322 BCE}}. Chandragupta rapidly expanded his power westwards across central and western India by conquering the ]s left by ], and by 317 BCE the empire had fully occupied northwestern India.{{sfn|R. K. Mookerji|1966|p=31}} The Mauryan Empire then defeated ], a ] and founder of the ], during the ], thus acquiring territory west of the Indus River.<ref>] ceded the territories of ] (modern Kandahar), ] (modern ]), and ] (or ]). ] (modern ]) "has been wrongly included in the list of ceded satrapies by some scholars ... on the basis of wrong assessments of the passage of Strabo ... and a statement by Pliny" (Raychaudhuri & Mukherjee 1996, p. 594).</ref>{{sfn|John D Grainger|2014|p=109|ps=: Seleucus "must ... have held Aria", and furthermore, his "son ] was active there fifteen years later".}} | |||

| {{quote|'' "He crossed the Indus and waged war with Maurya who dwelt on the banks of that stream, until they came to an understanding with each other and contracted a marriage relationship."}} | |||

| {{quote|''Alexander took these away from the ] and established settlements of his own, but ] gave them to ] (]), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants.''<ref name="aisk">{{cite web|url=http://www.aisk.org/aisk/NHDAHGTK05.php |title=An Historical Guide to Kabul: The Name |author=Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād |publisher=American International School of Kabul |year=1972 |accessdate=18 September 2010 |url-status=dead |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20100830031416/http://www.aisk.org/aisk/NHDAHGTK05.php |archivedate=30 August 2010 |df=dmy-all }}</ref>|]|64 BC–24 AD}} | |||

| Under the Mauryas, internal and external trade, agriculture, and economic activities thrived and expanded across South Asia due to the creation of a single and efficient system of finance, administration, and security. The Maurya dynasty built a precursor of the ] from Patliputra to Taxila.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://roadsandkingdoms.com/2016/dinner-on-the-grand-trunk-road/|title=Dinner on the Grand Trunk Road|last=Bhandari|first=Shirin|date=2016-01-05|publisher=Roads & Kingdoms|language=en-US|access-date=2016-07-19}}</ref> After the ], the Empire experienced nearly half a century of centralized rule under Ashoka. Ashoka's embrace of ] and sponsorship of Buddhist missionaries allowed for the expansion of that faith into ], northwest India, and Central Asia.{{sfn|Hermann Kulke|2004|p=67}} | |||

| Thus Chandragupta was given Gedrosia (]) and much of what is now ], including the modern ]<ref name="historyfiles.co.uk">{{cite web|last=Rajadhyaksha |first=Abhijit |url=http://www.historyfiles.co.uk/FeaturesFarEast/India_IronAge_Mauryas01.htm |title=The Mauryas: Chandragupta |publisher=Historyfiles.co.uk |date=2 August 2009 |accessdate=4 April 2013}}</ref> and ] provinces, thereby ending Macedonian control in the Indus Valley by 303 BC. | |||

| The population of South Asia during the Mauryan period has been estimated to be between 15 and 30 million.<ref name="Dyson2018-lead-maurya-4"> | |||

| Under Chandragupta and his successors, internal and external trade, agriculture and commercial activities all thrived and expanded across the Indian subcontinent due to the establishment of a cohesive system of finance, administration, and security. The empire was divided into four provinces, the imperial capital being at ]. From Asokan edicts, the names of the four provincial capitals were Tosali (in the eastern Ganges plain), Ujjain (in the western Ganges plain), Suvarnagiri (in the Deccan), and ] (in the northern Indus Valley). The head of the provincial administration was the ''Kumara'' (royal prince), who governed the provinces as king's representative and was assisted by ''Mahamatyas'' and a council of ministers. The empire also enjoyed an era of social harmony, religious transformation, and expansion of the sciences and of knowledge. | |||

| {{citation | |||

| ] | |||

| |last=Dyson|first=Tim|title=A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3TRtDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA24|year=2018|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-882905-8|page=24}} Quote: "Yet Sumit Guha considers that 20 million is an upper limit. This is because the demographic growth experienced in core areas is likely to have been less than that experienced in areas that were more lightly settled in the early historic period. The position taken here is that the population in Mauryan times (320–220 BCE) was between 15 and 30 million—although it may have been a little more, or it may have been a little less."</ref> | |||

| The empire's period of dominion was marked by exceptional creativity in art, architecture, inscriptions and produced texts.<ref name="Ludden2013-lead-4"> | |||

| Members of the Maurya dynasty were primarily adherents of ] and ]. Chandragupta Maurya's embrace of ] increased social and religious renewal and reform across his society, while Ashoka's embrace of Buddhism has been said to have been the foundation of the reign of social and political peace and non-violence across the empire.<ref name="historyfiles.co.uk" /> Proselytization of Buddhism was extended even to the Indo-Iranian and Greek peoples in the western frontiers and dominions of the empire, as mentioned by the Edicts of Asoka: | |||

| {{citation | |||

| ] | |||

| |last=Ludden | |||

| <blockquote>''Now they work among all religions for the establishment of Dhamma, for the promotion of Dhamma, and for the welfare and happiness of all who are devoted to Dhamma. They work among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Gandharas, the Rastrikas, the Pitinikas and other peoples on the western borders. (Edicts of Asoka, 5th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika)''</blockquote>By the time Chandragupta's grandson ] had become emperor, ] was flourishing through the ] and much of the eastern Seleucid Empire. Many of the Greek and Indo-Iranian peoples in the western domains also converted to Buddhism during this period, according to the Edicts of Asoka: <blockquote>''Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the ], the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the ] and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in ]. (], 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika).''</blockquote>]Although Buddhism was flourishing, ] was resisting Buddhist advances in the ] and when Ashoka himself converted to Buddhism, he directed his efforts towards expanding the faith in the Indo-Iranian and Hellenistic worlds. According to the stone-inscribed ]—some in bilingual Greek and Aramaic inscriptions—he sent Buddhist emissaries to Graeco-Asiatic kingdoms, as far away as the eastern Mediterranean. The edicts name each of the rulers of the ] world at the time, indicating the intimacy between Hellenistic and Buddhistic peoples in the region. | |||

| |first=David|title=India and South Asia: A Short History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EbFHAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA28|year=2013|publisher=Oneworld Publications|isbn=978-1-78074-108-6|pages=28–29}}Quote: "A creative explosion in all the arts was a most remarkable feature of this ancient transformation, a permanent cultural legacy. Mauryan territory was created in its day by awesome armies and dreadful war, but future generations would cherish its beautiful pillars, inscriptions, coins, sculptures, buildings, ceremonies, and texts, particularly later Buddhist writers." | |||

| <blockquote>''The conquest by ] has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred ]s (4,000 miles) away, where the Greek king ] rules, beyond there where the four kings named ], ], ] and ] rule, likewise in the south among the ]s, the ]s, and as far as ]. (], 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika).''</blockquote> | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Furthermore, according to ] sources, some of Ashoka's emissaries were Greek-Buddhist monks, indicating close religious exchanges between the two cultures: | |||

| <blockquote>When the thera (elder) Moggaliputta, the illuminator of the religion of the Conqueror (Ashoka), had brought the (third) council to an end… he sent forth theras, one here and one there: …and to Aparantaka (the "Western countries" corresponding to ] and ]) he sent the Greek (]) named ]... and the thera Maharakkhita he sent into the country of the Yona. (], XII).</blockquote> | |||

| When Ashoka died in 232 BC, Mauryan hold on the Indus began weakening. Other Empires tried to retake control of the Ganges heartland though the ]. As such, the Mauryans began retreating out of the Indus back east towards ] (Patna) to protect the imperial capital. This left most of the Indus Valley unguarded and most importantly left the ] open to invasion. In 250 BC, the eastern part of the Seleucid Empire broke away to form the ] by ] of ]. In 230 BC, ] overthrew Diodotus to establish himself as king, firmly establishing a Hellenistic kingdom in northern Afghanistan and Tajikistan, distinct from the neighboring Seleucid Empire. The Greco-Bactrians were allied with the Mauryans and had kept close relations with Ashoka. | |||