| Revision as of 17:03, 15 July 2005 editCodex Sinaiticus (talk | contribs)17,640 edits →Elamite language← Previous edit | Revision as of 12:40, 22 July 2005 edit undoJguk (talk | contribs)15,849 editsm copyeditNext edit → | ||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {{Iran}} | {{Iran}} | ||

| '''Elam''' (تمدن عیلام in ]) is one of the first ]s on record based in the far west and south-west of what is modern-day ] (in the ] and the lowlands of ]). It lasted from around ] to ], coming after what is known as the ] period, which began around ] when ], the later capital of the ] began to receive influence from the cultures of the ] to the east. | '''Elam''' (تمدن عیلام in ]) is one of the first ]s on record based in the far west and south-west of what is modern-day ] (in the ] and the lowlands of ]). It lasted from around ] to ], coming after what is known as the ] period, which began around ] when ], the later capital of the ] began to receive influence from the cultures of the ] to the east. | ||

| Ancient Elam lay to the east of ] and ] (modern-day ]). In the Old Elamite period, it consisted of kingdoms on the ], |

Ancient Elam lay to the east of ] and ] (modern-day ]). In the Old Elamite period, it consisted of kingdoms on the ], centred in ], and from the mid-], it centred in ] in the Khuzestan lowlands. Its culture played a crucial role in the ], especially during the ] that succeeded it, when the ] remained in official use. The Elamite period is thus sometimes considered a starting point for the ] (although the Elamite language was not related to ]). | ||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| The Elamites called their country ''Haltamti'' (in later Elamite, ''Atamti''), which the neighbouring ] rendered as ''Elam''. ''Elam'' means "highland". Additionally, the Haltamti were known as ''Elam'' in the ], where they are called the offspring of Elam, eldest son of ] (see ]). | The Elamites called their country ''Haltamti'' (in later Elamite, ''Atamti''), which the neighbouring ] rendered as ''Elam''. ''Elam'' means "highland". Additionally, the Haltamti were known as ''Elam'' in the ], where they are called the offspring of Elam, eldest son of ] (see ]). | ||

| The high country of Elam was increasingly identified by its low-lying later capital, ] |

The high country of Elam was increasingly identified by its low-lying later capital, ]. Geographers after ] called it ''Susiana''. The Elamite civilisation was primarily centred in the province of what is modern-day ], however it did extended into the later province of ] in prehistoric times. In fact, the modern provincial name ] is derived from the Old Persian root ''Hujiyā'', meaning "Elam". | ||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{Template:Ancient Mesopotamia}} | {{Template:Ancient Mesopotamia}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Knowledge of Elamite history remains largely fragmentary, reconstruction being based on mainly ]n sources. The city of ] was founded around ], and during its early history, fluctuated between submission to Mesopotamian and Elamite power. The earliest levels (22-17 in the excavations conducted by Le Brun, 1978) exhibit pottery that has no equivalent in Mesopotamia, but for the succeeding period, the excavated material allows identification with the culture of ] of the ]. ] influence from the ] in Susa becomes visible from about ], and texts in the still-undeciphered ] continue to be present until about ]. The Proto-Elamite period ends with the establishment of the ]. The earliest known historical figure connected with Elam is the king ] of ] (c. ]?), who subdued it, according to the ]. However, real Elamite history can only be traced from records dating to beginning of the ] in around ] onwards. | Knowledge of Elamite history remains largely fragmentary, reconstruction being based on mainly ]n sources. The city of ] was founded around ], and during its early history, fluctuated between submission to Mesopotamian and Elamite power. The earliest levels (22-17 in the excavations conducted by Le Brun, 1978) exhibit pottery that has no equivalent in Mesopotamia, but for the succeeding period, the excavated material allows identification with the culture of ] of the ]. ] influence from the ] in Susa becomes visible from about ], and texts in the still-undeciphered ] continue to be present until about ]. The Proto-Elamite period ends with the establishment of the ]. The earliest known historical figure connected with Elam is the king ] of ] (c. ]?), who subdued it, according to the ]. However, real Elamite history can only be traced from records dating to beginning of the ] in around ] onwards. | ||

| Elamite civilisation grew up east of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, in the watershed of the river ]. In modern terms, Elam included more than Khuzestan; it was a combination of the lowlands and the immediate highland areas to the north and east. Some Elamite sites, however, are found well outside this area, spread out on the ]; examples of Elamite remains north and east of Iran are ] in ] and ] in ]. Elamite strength was based on an ability to hold these various areas together under a coordinated government that permitted the maximum interchange of the natural resources unique to each region. Traditionally, this was done through a federated governmental structure. | Elamite civilisation grew up east of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, in the watershed of the river ]. In modern terms, Elam included more than Khuzestan; it was a combination of the lowlands and the immediate highland areas to the north and east. Some Elamite sites, however, are found well outside this area, spread out on the ]; examples of Elamite remains north and east of Iran are ] in ] and ] in ]. Elamite strength was based on an ability to hold these various areas together under a coordinated government that permitted the maximum interchange of the natural resources unique to each region. Traditionally, this was done through a federated governmental structure. | ||

| The history of Elam is conventionally divided into three periods, spanning more than two millennia: | The history of Elam is conventionally divided into three periods, spanning more than two millennia. The period before the first Elamite period is known as the pro-Elamite period: | ||

| *Proto-Elamite: c. 3200 |

*Proto-Elamite: c. 3200 BC – 2700 BC (Proto-Elamite script in Susa) | ||

| *Old Elamite period: c. 2700 |

*Old Elamite period: c. 2700 BC – 1600 BC (earliest documents until the Eparti dynasty) | ||

| *Middle Elamite period: c. 1500 |

*Middle Elamite period: c. 1500 BC – 1100 BC (Anzanite dynasty until the Babylonian invasion of Susa) | ||

| *Neo-Elamite period: c. 1100 |

*Neo-Elamite period: c. 1100 BC – 539 BC (characterised by Iranian and Syrian influence. 539 BCE marks the beginning of the Achaemenid period) | ||

| === Old Elamite Period === | === Old Elamite Period === | ||

| [[Image:Marlik vase monster.jpg|thumb|right|Golden Vase with Winged Monsters | [[Image:Marlik vase monster.jpg|thumb|right|Golden Vase with Winged Monsters | ||

| Marlik Region, ], Iran 14th-13th centuries |

Marlik Region, ], Iran 14th-13th centuries BC. Excavated by The ].]] | ||

| ], with Proto-Elamite inscription on it. 3rd Millenium |

], with Proto-Elamite inscription on it. 3rd Millenium BC. ].]] | ||

| The Old Elamite period began around 2700 |

The Old Elamite period began around 2700 BC. Historical records mention the conquest of Elam by ] of ]. Three dynasties ruled during this period. We know of twelve kings of each of the first two dynasties, those of Avan (c. 2400–2100 BC) and Simash (c. 2100-1970 BC), from a list from Susa dating to the Old Babylonian period. Two Elamite dynasties said to have exercised brief control over Sumer in very early times include Avan and Hamazi, and likewise, several of the stronger Sumerian rulers, such as Eannatum of Lagash and Lugal-anne-mundu of Adab, are recorded as temporarily dominating Elam. | ||

| The Avan dynasty was partly contemporary with that of ], who not only subjected Elam, but attempted to make Akkadian the official language there. However, with the collapse of Akkad under Sargon's great-grandson, ], Elam declared independence and threw off the Akkadian language. | The Avan dynasty was partly contemporary with that of ], who not only subjected Elam, but attempted to make Akkadian the official language there. However, with the collapse of Akkad under Sargon's great-grandson, ], Elam declared independence and threw off the Akkadian language. | ||

| The last Avan king, Puzur-Inshushinnak was roughly a contemporary of ]. From this time, Mesopotamian sources concerning Elam become more frequent, since the Mesopotamians had developed an interest in resources (such as wood, stone and metal) from the Iranian plateau, and military expeditions to the area became more common. Puzur-Inshushinnak conquered Susa and Anshan, and seems to have achieved some sort of political unity. A few years later, ] of ] retook the city of Susa and the surrounding region. During the first part of the rule of the Simashki dynasty, Elam was under intermittent attack from Mesopotamians and Gutians, alternating with periods of peace and diplomatic approaches. ] of Ur, for example, gave one of his daughters in marriage to a prince of Anshan. But the power of the Sumerians was waning; ] in the 21st century did not manage to penetrate far into Elam, and in ], the Elamites, allied with the people of Susa and led by king Kindattu, the sixth king of Simashk, managed to sack Ur and lead Ibbi-Sin into captivity -- thus ending the ]. However, the kings of ], successor state to Ur, did manage to drive the Elamites out of Ur, rebuild the city, and to return the statue of Nanna that the Elamites had plundered. | The last Avan king, Puzur-Inshushinnak was roughly a contemporary of ]. From this time, Mesopotamian sources concerning Elam become more frequent, since the Mesopotamians had developed an interest in resources (such as wood, stone and metal) from the Iranian plateau, and military expeditions to the area became more common. Puzur-Inshushinnak conquered Susa and Anshan, and seems to have achieved some sort of political unity. A few years later, ] of ] retook the city of Susa and the surrounding region. During the first part of the rule of the Simashki dynasty, Elam was under intermittent attack from Mesopotamians and Gutians, alternating with periods of peace and diplomatic approaches. ] of Ur, for example, gave one of his daughters in marriage to a prince of Anshan. But the power of the Sumerians was waning; ] in the 21st century did not manage to penetrate far into Elam, and in ], the Elamites, allied with the people of Susa and led by king Kindattu, the sixth king of Simashk, managed to sack Ur and lead Ibbi-Sin into captivity -- thus ending the ]. However, the kings of ], successor state to Ur, did manage to drive the Elamites out of Ur, rebuild the city, and to return the statue of Nanna that the Elamites had plundered. | ||

| The succeeding dynasty, the Epartids ( |

The succeeding dynasty, the Epartids (a. 1970–1600 BC), also called "of the ''sukkalmah''s" because of the title borne by its members, was contemporary with the Old Babylonian period in Mesopotamia. This period is confusing and difficult to reconstruct. It was apparently founded by Eparti II, the ninth ruler of the Shimashki dynasty. During this time, Susa was under Elamite control, but Mesopotamian states such as ] continually tried to retake the city. Sirukdukh, the third ruler of this dynasty, entered various military coalitions to contain the rising power of Babylon. Kudur-mabug, apparently king of another Elamite state to the north of Susa, managed to install his son, Warad-Sin, on the throne of Larsa, and Warad-Sin's brother, Rim-Sin (the biblical Arioch), succeeded him and conquered much of Mesopotamia for Larsa before being overthrown by ] of ]. | ||

| The most notable Epartid ruler was Siwe-palar-huppak, who for some time was the most powerful person in the area, respectfully addressed as "Father" by Mesopotamian kings such as ] of ], and even Hammurabi. But Elamite influence in Mesopotamia did not last, and after a few years, Hammurabi established ]n dominance in Mesopotamia. Little is known about the latter part of this dynasty, since sources become again more sparse with the ] rule of Babylon. | The most notable Epartid ruler was Siwe-palar-huppak, who for some time was the most powerful person in the area, respectfully addressed as "Father" by Mesopotamian kings such as ] of ], and even Hammurabi. But Elamite influence in Mesopotamia did not last, and after a few years, Hammurabi established ]n dominance in Mesopotamia. Little is known about the latter part of this dynasty, since sources become again more sparse with the ] rule of Babylon. | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

| === Middle Elamite Period === | === Middle Elamite Period === | ||

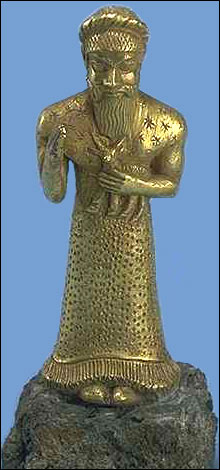

| ], Iran | ], Iran | ||

| 12th century |

12th century BC, excavated by Ronald de Mecquenem in 1904.]] | ||

| The Middle Elamite period began with the rise of the Anshanite dynasties around 1500 BCE. Their rule was characterised by an "Elamisation" of Susa, and the kings took the title "king of Anshan and Susa". While the first of these dynasties, the Kidinuids continued to use the Akkadian language frequently in their inscriptions, the succeeding Igihalkids and Shutrukids used Elamite with increasing regularity. Likewise, Elamite language and culture grew in importance in Susiana. | The Middle Elamite period began with the rise of the Anshanite dynasties around 1500 BCE. Their rule was characterised by an "Elamisation" of Susa, and the kings took the title "king of Anshan and Susa". While the first of these dynasties, the Kidinuids continued to use the Akkadian language frequently in their inscriptions, the succeeding Igihalkids and Shutrukids used Elamite with increasing regularity. Likewise, Elamite language and culture grew in importance in Susiana. | ||

| Line 48: | Line 48: | ||

| The Kidinuids (c. 1500–1400) are a group of five rulers of uncertain affiliation. They are identified by their use of the older title, "king of Susa and of Anshan", and by calling themselves "servant of Kirwashir", an Elamite deity, thereby introducing the pantheon of the highlands to Susiana. | The Kidinuids (c. 1500–1400) are a group of five rulers of uncertain affiliation. They are identified by their use of the older title, "king of Susa and of Anshan", and by calling themselves "servant of Kirwashir", an Elamite deity, thereby introducing the pantheon of the highlands to Susiana. | ||

| Of the Igihalkids (ca. 1400–1210), ten rulers are known, and there were possibly more. Some of them married ] princesses. The Kassite king Kurigalzu II temporarily occupied Elam c. 1320 |

Of the Igihalkids (ca. 1400–1210), ten rulers are known, and there were possibly more. Some of them married ] princesses. The Kassite king Kurigalzu II temporarily occupied Elam c. 1320 BC, and later (c. 1230) another Kassite king, Kashtiliash IV, fought Elam unsuccessfully. Kidin-Hutran I of Elam repulsed the Kassites by defeating Enlil-nadin-shumi in 1224 and Adad-shuma-iddina around 1222-17. Under the Igihalkids, Akkadian inscriptions were rare, and Elamite highland gods became firmly established in Susa. | ||

| Under the Shutrukids (c. 1210–1100), the Elamite empire reached the height of its power. Shutruk-Nahhunte and his three sons, Kutir-Nahhunte II, Shilhak-Inshushinak, and Khutelutush-Inshushinak were capable of frequent military campaigns into Kassite Mesopotamia, and at the same time were exhibiting vigorous construction activity -- building and restoring luxurious temples in Susa and across their Empire. Shutruk-Nahhunte raided Akkad, Babylon, and Eshnunna, carrying home to Susa trophies like the statues of Marduk and Manishtushu, the ] and the stele of ]. | Under the Shutrukids (c. 1210–1100), the Elamite empire reached the height of its power. Shutruk-Nahhunte and his three sons, Kutir-Nahhunte II, Shilhak-Inshushinak, and Khutelutush-Inshushinak were capable of frequent military campaigns into Kassite Mesopotamia, and at the same time were exhibiting vigorous construction activity -- building and restoring luxurious temples in Susa and across their Empire. Shutruk-Nahhunte raided Akkad, Babylon, and Eshnunna, carrying home to Susa trophies like the statues of Marduk and Manishtushu, the ] and the stele of ]. | ||

| In ], Shutruk-Nahhunte defeated the Kassites permanently, killing the Kassite king of Babylon, ], and replacing him with his eldest son, Kutir-Nahhunte, who held it no more than three years. | In ], Shutruk-Nahhunte defeated the Kassites permanently, killing the Kassite king of Babylon, ], and replacing him with his eldest son, Kutir-Nahhunte, who held it no more than three years. | ||

| Kutir-Nahhunte's son Khutelutush-Inshushinak was the last king of the Shutrukids. He was probably of an incestuous relation of Kutir-Nahhunte's with his own daughter, Nahhunte-utu. He ended up temporarily yielding Susa to the forces of ] I of Babylon, who returned the statue of Marduk. He fled to Anshan, but later returned to Susa, and his brother Shilhina-Hamru-Lagamar may have succeeded him. Following Khutelutush-Inshushinak, the power of the Elamite empire began to wane seriously, for with this ruler, Elam disappears into obscurity for more than three centuries. | Kutir-Nahhunte's son Khutelutush-Inshushinak was the last king of the Shutrukids. He was probably of an incestuous relation of Kutir-Nahhunte's with his own daughter, Nahhunte-utu. He ended up temporarily yielding Susa to the forces of ] I of Babylon, who returned the statue of Marduk. He fled to Anshan, but later returned to Susa, and his brother Shilhina-Hamru-Lagamar may have succeeded him. Following Khutelutush-Inshushinak, the power of the Elamite empire began to wane seriously, for with this ruler, Elam disappears into obscurity for more than three centuries. | ||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

| === Neo-Elamite Period === | === Neo-Elamite Period === | ||

| ====Neo-Elamite I ( |

====Neo-Elamite I (c. 1100–770)==== | ||

| Very little is known of this period. Anshan was still at least partially Elamite. There appear to have been alliances of Elam and Babylonia against the Assyrians; the Babylonian king Mar-biti-apla-ushur (984—79) was of Elamite origin, and Elamites are recorded to have fought with the Babylonian king Marduk-balassu-iqbi against the Assyrian forces under ] (823–11). | Very little is known of this period. Anshan was still at least partially Elamite. There appear to have been alliances of Elam and Babylonia against the Assyrians; the Babylonian king Mar-biti-apla-ushur (984—79) was of Elamite origin, and Elamites are recorded to have fought with the Babylonian king Marduk-balassu-iqbi against the Assyrian forces under ] (823–11). | ||

| ====Neo-Elamite II ( |

====Neo-Elamite II (c. 770–646)==== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The later Neo-Elamite period is |

The later Neo-Elamite period is characterised by a significant migration of ] to the Iranian plateau. Assyrian sources beginning around 800 BC distinguish the "powerful Medes", ie the actual ], and the "distant Medes" that would later enter history under their proper names, (], ], ], ], ] etc). This pressure of immigrating Iranians pushed the Elamites of Anshan towards Susa, so that in the course ot this period, Susiana became known as Elam, while Anshan and the Iranian plateau, the original home of the Elamites, were renamed Persia proper. The Elamite kings, apart from the last three, nevertheless continued to claim the title of "king of Anshan and Susa". | ||

| More details of an alliance of Babylonia and Elam against Assyria are tangible from the late ]. | More details of an alliance of Babylonia and Elam against Assyria are tangible from the late ]. | ||

| Humban-nikash (743–17) supported ] against ], apparently with limited success; while his successor, Shutruk-Nahhunte II (716–699), was routed by Sargon's troops during an expedition in 710, and another Elamite defeat by Sargon's troops is recorded for 708. The Assyrian victory was completed by Sargon's son ], who dethroned Merodach-baladan and installed his own son ] on the throne of Babylon. | Humban-nikash (743–17) supported ] against ], apparently with limited success; while his successor, Shutruk-Nahhunte II (716–699), was routed by Sargon's troops during an expedition in 710, and another Elamite defeat by Sargon's troops is recorded for 708. The Assyrian victory was completed by Sargon's son ], who dethroned Merodach-baladan and installed his own son ] on the throne of Babylon. | ||

| Shutruk-Nahhunte was murdered by his brother Hallushu, who managed to capture Assur-nadin-shumi, and was in turn assassinated by Kudur -- who succeeded him, but soon abdicated in favour of Humban-umena III (692–89). Humban-umena recruited a new army to help the Babylonians against the Assyrians at the battle of ] in ]. The battle was indecisive, or at least both sides claimed the victory in their annals, but Babylon fell to the Assyrians only two years later. | Shutruk-Nahhunte was murdered by his brother Hallushu, who managed to capture Assur-nadin-shumi, and was in turn assassinated by Kudur -- who succeeded him, but soon abdicated in favour of Humban-umena III (692–89). Humban-umena recruited a new army to help the Babylonians against the Assyrians at the battle of ] in ]. The battle was indecisive, or at least both sides claimed the victory in their annals, but Babylon fell to the Assyrians only two years later. | ||

| The reigns of Humban-haltash I (688–81) and Humban-haltash II (680–75) saw a deterioration of Elamite-Babylonian relations, and both of them raided ]. Urtak (674–64) for some time maintained good relations with ] (668&ndsah;27), who sent wheat to Susiana during a famine. But these friendly relations were only temporary, and Urtak died during another Elamite attack on Mesopotamia. | The reigns of Humban-haltash I (688–81) and Humban-haltash II (680–75) saw a deterioration of Elamite-Babylonian relations, and both of them raided ]. Urtak (674–64) for some time maintained good relations with ] (668&ndsah;27), who sent wheat to Susiana during a famine. But these friendly relations were only temporary, and Urtak died during another Elamite attack on Mesopotamia. | ||

| His successor Te-Umman (664–53) was counter-attacked by Assurbanipal, and was killed following the battle of the Ulaï in ]; and Elam was occupied by the Assyrians. During a brief respite provided by the civil war between Assurbanipal and his brother Shamash-shum-ukin, the Elamites too indulged in fighting among themselves, so weakening the Elamite kingdom that in ] Assurbanipal devastated Susiana with ease, and sacked Susa. A succession of brief reigns continued in Elam from 651 to 640, each of them ended either due to usurpation, or because of capture of their king by the Assyrians. In this manner, the last Elamite king, Humban-Haldash III, was captured in 640 |

His successor Te-Umman (664–53) was counter-attacked by Assurbanipal, and was killed following the battle of the Ulaï in ]; and Elam was occupied by the Assyrians. During a brief respite provided by the civil war between Assurbanipal and his brother Shamash-shum-ukin, the Elamites too indulged in fighting among themselves, so weakening the Elamite kingdom that in ] Assurbanipal devastated Susiana with ease, and sacked Susa. A succession of brief reigns continued in Elam from 651 to 640, each of them ended either due to usurpation, or because of capture of their king by the Assyrians. In this manner, the last Elamite king, Humban-Haldash III, was captured in 640 BC by Ashurbanipal, who devastated the country. | ||

| In a tablet unearthed in 1854 by Henry Austin Layard, Ashurbanipal boasts of the destruction he had wrought: | In a tablet unearthed in 1854 by Henry Austin Layard, Ashurbanipal boasts of the destruction he had wrought: | ||

| :"Susa, the great holy city, abode of their Gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed...I destroyed the ]. I smashed its shining copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated, I exposed to the sun, and I carried away their bones |

:"Susa, the great holy city, abode of their Gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed...I destroyed the ]. I smashed its shining copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated, I exposed to the sun, and I carried away their bones towards the land of Ashur. I devastated the provinces of Elam and on their lands I ]." (''Persians: Masters of Empire'', p7-8, ISBN 0-80949104-4) | ||

| ====Neo-Elamite III (646–539)==== | ====Neo-Elamite III (646–539)==== | ||

| The devastation was however less complete than Assurbanipal boasted, and Elamite rule was resurrected soon after with Shutur-Nahhunte, son of Humban-umena III (not to be confused with Shutur-Nahhunte, son of Indada, |

The devastation was however less complete than Assurbanipal boasted, and Elamite rule was resurrected soon after with Shutur-Nahhunte, son of Humban-umena III (not to be confused with Shutur-Nahhunte, son of Indada, a petty king in the first half of the 6th century). | ||

| Elamite royalty in the final century preceding the Achaemenids | Elamite royalty in the final century preceding the Achaemenids | ||

| was fragmented among different small kingdoms, The three kings at the close of the 7th century (Shutur-Nahhunte, Hallutash-Inshushinak and Atta-hamiti-Inshushinak) still called themselves "king of Anzan and of Susa" or "enlarger of the kingdom of Anzan and of Susa |

was fragmented among different small kingdoms, The three kings at the close of the 7th century (Shutur-Nahhunte, Hallutash-Inshushinak and Atta-hamiti-Inshushinak) still called themselves "king of Anzan and of Susa" or "enlarger of the kingdom of Anzan and of Susa", at a time when the Achaemenids were already ruling Anshan. | ||

| Their successors Ummanunu and Shilhak-Inshushinak II bore the simple title "king," and the final king Tepti-Humban-Inshushinak boasted no title altogether. In ], ] rule begins in Susa. | Their successors Ummanunu and Shilhak-Inshushinak II bore the simple title "king," and the final king Tepti-Humban-Inshushinak boasted no title altogether. In ], ] rule begins in Susa. | ||

| ==Elamite language== | ==Elamite language== | ||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

| Elamite is unrelated to the neighbouring ], ] and ] languages. It was written in a cuneiform adapted from Akkadian script, although the very earliest documents were written in the quite different "Linear Elamite" script. This seems to have developed from an even earlier writing known as "proto-Elamite", but scholars are not unanimous on whether or not this script was used to write Elamite or another language, and it has not yet been deciphered. | Elamite is unrelated to the neighbouring ], ] and ] languages. It was written in a cuneiform adapted from Akkadian script, although the very earliest documents were written in the quite different "Linear Elamite" script. This seems to have developed from an even earlier writing known as "proto-Elamite", but scholars are not unanimous on whether or not this script was used to write Elamite or another language, and it has not yet been deciphered. | ||

| Some linguists believe Elamite may be related to the living ] (of southern India, and ] in Pakistan). The |

Some linguists believe Elamite may be related to the living ] (of southern India, and ] in Pakistan). The hypothesised family of ] may further prove to be connected with the ] somewhat to the East, possibly corresponding to ] in Sumerian records. However, such links are at best conjectural, and ] have also yet to be deciphered. | ||

| Several stages of the language are attested; the earliest date back to the third milennium |

Several stages of the language are attested; the earliest date back to the third milennium BC, the latest to the ]. | ||

| The Elamite language may have survived as late as the early Islamic period. ] among other Arab , for instance, wrote that "The Iranian languages are Fahlavi (Pahlavi), Dari, Khuzi, Persian and Suryani", and ] noted that ''Khuzi'' was the unofficial language of the royalty of Persia, "Khuz" being the corrupted name for Elam. ''See ] for details.'' | The Elamite language may have survived as late as the early Islamic period. ] among other Arab , for instance, wrote that "The Iranian languages are Fahlavi (Pahlavi), Dari, Khuzi, Persian and Suryani", and ] noted that ''Khuzi'' was the unofficial language of the royalty of Persia, "Khuz" being the corrupted name for Elam. ''See ] for details.'' | ||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

| ==The Elamite Legacy== | ==The Elamite Legacy== | ||

| ].]] | ].]] | ||

| The Assyrians thought that they had utterly destroyed the Elamites, but new polities emerged in the area after Assyrian power faded. However, they never again exercised the power of the earlier Elamite empires; they controlled the watershed of the Karun and little beyond. Among the nations that benefitted from the decline of the Assyrians were the ], whose presence around ] to the north of Elam is attested from the ] in Assyrian texts. Some time after that region fell to Madius the Scythian (653 |

The Assyrians thought that they had utterly destroyed the Elamites, but new polities emerged in the area after Assyrian power faded. However, they never again exercised the power of the earlier Elamite empires; they controlled the watershed of the Karun and little beyond. Among the nations that benefitted from the decline of the Assyrians were the ], whose presence around ] to the north of Elam is attested from the ] in Assyrian texts. Some time after that region fell to Madius the Scythian (653 BC), ] son of ] conquered Elamite ] in the mid ], forming a nucleus that would expand into the ]. | ||

| ===Elamite influence on the Achaemenids=== | ===Elamite influence on the Achaemenids=== | ||

| The rise of the ]s in the ] brought an end to the existence of Elam as an independent political power "but not as a cultural entity" (Encyclopedia Iranica, ]). Indigenous Elamite traditions, such as the use of the title "king of Anshan" by ]; the "Elamite robe" worn by ] and seen on the famous winged ] at ]; some glyptic styles; the use of Elamite as the first of three official languages of the empire used in thousands of administrative texts found at Darius’ city of ]; the continued worship of Elamite deities; and the persistence of Elamite religious personnel and cults supported by the crown, formed an essential part of the newly emerging Achaemenid culture in Persian Iran. The Elamites thus became the conduit by which achievements of the Mesopotamian civilisations were introduced to the tribes of the Iranian plateau. | The rise of the ]s in the ] brought an end to the existence of Elam as an independent political power "but not as a cultural entity" (Encyclopedia Iranica, ]). Indigenous Elamite traditions, such as the use of the title "king of Anshan" by ]; the "Elamite robe" worn by ] and seen on the famous winged ] at ]; some glyptic styles; the use of Elamite as the first of three official languages of the empire used in thousands of administrative texts found at Darius’ city of ]; the continued worship of Elamite deities; and the persistence of Elamite religious personnel and cults supported by the crown, formed an essential part of the newly emerging Achaemenid culture in Persian Iran. The Elamites thus became the conduit by which achievements of the Mesopotamian civilisations were introduced to the tribes of the Iranian plateau. | ||

| According to the editors of ''Persians, Masters of Empire'': "The Elamites, fierce rivals of the Babylonians, were precursors of the royal Persians" (ISBN 0-80949104-4). This view is widely accepted today, as experts unanimously recognise the Elamites to have "absorbed Iranian influences in both structure and vocabulary" by 500 |

According to the editors of ''Persians, Masters of Empire'': "The Elamites, fierce rivals of the Babylonians, were precursors of the royal Persians" (ISBN 0-80949104-4). This view is widely accepted today, as experts unanimously recognise the Elamites to have "absorbed Iranian influences in both structure and vocabulary" by 500 BC. (], ]) | ||

| The Elamite civilisation's originality, coupled with studies carried out at Elamite sites well spread out over the ], have led modern historians to conclude that "The Elamites are the founders of the first Iranian empire in the geographic sense". (Elton Daniel, ''The History of Iran'', p. 26) | The Elamite civilisation's originality, coupled with studies carried out at Elamite sites well spread out over the ], have led modern historians to conclude that "The Elamites are the founders of the first Iranian empire in the geographic sense". (Elton Daniel, ''The History of Iran'', p. 26) | ||

Revision as of 12:40, 22 July 2005

- For biblical characters named Elam, see Elam (Hebrew Bible).

Template:Iran Elam (تمدن عیلام in Persian) is one of the first civilisations on record based in the far west and south-west of what is modern-day Iran (in the Ilam Province and the lowlands of Khuzestan). It lasted from around 2700 BC to 539 BC, coming after what is known as the Proto-Elamite period, which began around 3200 BC when Susa, the later capital of the Elamites began to receive influence from the cultures of the Iranian plateau to the east.

Ancient Elam lay to the east of Sumer and Akkad (modern-day Iraq). In the Old Elamite period, it consisted of kingdoms on the Iranian plateau, centred in Anshan, and from the mid-2nd millennium BC, it centred in Susa in the Khuzestan lowlands. Its culture played a crucial role in the Persian Empire, especially during the Achaemenid dynasty that succeeded it, when the Elamite language remained in official use. The Elamite period is thus sometimes considered a starting point for the history of Iran (although the Elamite language was not related to Persian).

Etymology

The Elamites called their country Haltamti (in later Elamite, Atamti), which the neighbouring Akkadians rendered as Elam. Elam means "highland". Additionally, the Haltamti were known as Elam in the Hebrew Old Testament, where they are called the offspring of Elam, eldest son of Shem (see Elam (Hebrew Bible)).

The high country of Elam was increasingly identified by its low-lying later capital, Susa. Geographers after Ptolemy called it Susiana. The Elamite civilisation was primarily centred in the province of what is modern-day Khuzestan, however it did extended into the later province of Fars in prehistoric times. In fact, the modern provincial name Khuzestān is derived from the Old Persian root Hujiyā, meaning "Elam".

History

| Ancient Mesopotamia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geography |

|  | ||||

| (Pre)history |

| |||||

| Languages | ||||||

| Culture/society |

| |||||

| Archaeology | ||||||

| Religion | ||||||

| Academia | ||||||

Knowledge of Elamite history remains largely fragmentary, reconstruction being based on mainly Mesopotamian sources. The city of Susa was founded around 4000 BC, and during its early history, fluctuated between submission to Mesopotamian and Elamite power. The earliest levels (22-17 in the excavations conducted by Le Brun, 1978) exhibit pottery that has no equivalent in Mesopotamia, but for the succeeding period, the excavated material allows identification with the culture of Sumer of the Uruk period. Proto-Elamite influence from the Persian plateau in Susa becomes visible from about 3200 BC, and texts in the still-undeciphered Proto-Elamite script continue to be present until about 2700 BC. The Proto-Elamite period ends with the establishment of the Awan dynasty. The earliest known historical figure connected with Elam is the king Enmebaragesi of Kish (c. 2650 BC?), who subdued it, according to the Sumerian king list. However, real Elamite history can only be traced from records dating to beginning of the Akkadian Empire in around 2300 BC onwards.

Elamite civilisation grew up east of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, in the watershed of the river Karun. In modern terms, Elam included more than Khuzestan; it was a combination of the lowlands and the immediate highland areas to the north and east. Some Elamite sites, however, are found well outside this area, spread out on the Iranian plateau; examples of Elamite remains north and east of Iran are Sialk in Isfahan Province and Jiroft in Kerman Province. Elamite strength was based on an ability to hold these various areas together under a coordinated government that permitted the maximum interchange of the natural resources unique to each region. Traditionally, this was done through a federated governmental structure.

The history of Elam is conventionally divided into three periods, spanning more than two millennia. The period before the first Elamite period is known as the pro-Elamite period:

- Proto-Elamite: c. 3200 BC – 2700 BC (Proto-Elamite script in Susa)

- Old Elamite period: c. 2700 BC – 1600 BC (earliest documents until the Eparti dynasty)

- Middle Elamite period: c. 1500 BC – 1100 BC (Anzanite dynasty until the Babylonian invasion of Susa)

- Neo-Elamite period: c. 1100 BC – 539 BC (characterised by Iranian and Syrian influence. 539 BCE marks the beginning of the Achaemenid period)

Old Elamite Period

The Old Elamite period began around 2700 BC. Historical records mention the conquest of Elam by Enmebaragesi of Kish. Three dynasties ruled during this period. We know of twelve kings of each of the first two dynasties, those of Avan (c. 2400–2100 BC) and Simash (c. 2100-1970 BC), from a list from Susa dating to the Old Babylonian period. Two Elamite dynasties said to have exercised brief control over Sumer in very early times include Avan and Hamazi, and likewise, several of the stronger Sumerian rulers, such as Eannatum of Lagash and Lugal-anne-mundu of Adab, are recorded as temporarily dominating Elam.

The Avan dynasty was partly contemporary with that of Sargon of Akkad, who not only subjected Elam, but attempted to make Akkadian the official language there. However, with the collapse of Akkad under Sargon's great-grandson, Shar-kali-sharri, Elam declared independence and threw off the Akkadian language.

The last Avan king, Puzur-Inshushinnak was roughly a contemporary of Ur-Nammu. From this time, Mesopotamian sources concerning Elam become more frequent, since the Mesopotamians had developed an interest in resources (such as wood, stone and metal) from the Iranian plateau, and military expeditions to the area became more common. Puzur-Inshushinnak conquered Susa and Anshan, and seems to have achieved some sort of political unity. A few years later, Shulgi of Ur retook the city of Susa and the surrounding region. During the first part of the rule of the Simashki dynasty, Elam was under intermittent attack from Mesopotamians and Gutians, alternating with periods of peace and diplomatic approaches. Shu-Sin of Ur, for example, gave one of his daughters in marriage to a prince of Anshan. But the power of the Sumerians was waning; Ibbi-Sin in the 21st century did not manage to penetrate far into Elam, and in 2004 BC, the Elamites, allied with the people of Susa and led by king Kindattu, the sixth king of Simashk, managed to sack Ur and lead Ibbi-Sin into captivity -- thus ending the third dynasty of Ur. However, the kings of Isin, successor state to Ur, did manage to drive the Elamites out of Ur, rebuild the city, and to return the statue of Nanna that the Elamites had plundered.

The succeeding dynasty, the Epartids (a. 1970–1600 BC), also called "of the sukkalmahs" because of the title borne by its members, was contemporary with the Old Babylonian period in Mesopotamia. This period is confusing and difficult to reconstruct. It was apparently founded by Eparti II, the ninth ruler of the Shimashki dynasty. During this time, Susa was under Elamite control, but Mesopotamian states such as Larsa continually tried to retake the city. Sirukdukh, the third ruler of this dynasty, entered various military coalitions to contain the rising power of Babylon. Kudur-mabug, apparently king of another Elamite state to the north of Susa, managed to install his son, Warad-Sin, on the throne of Larsa, and Warad-Sin's brother, Rim-Sin (the biblical Arioch), succeeded him and conquered much of Mesopotamia for Larsa before being overthrown by Hammurabi of Babylon.

The most notable Epartid ruler was Siwe-palar-huppak, who for some time was the most powerful person in the area, respectfully addressed as "Father" by Mesopotamian kings such as Zimri-Lim of Mari, and even Hammurabi. But Elamite influence in Mesopotamia did not last, and after a few years, Hammurabi established Babylonian dominance in Mesopotamia. Little is known about the latter part of this dynasty, since sources become again more sparse with the Kassite rule of Babylon.

Middle Elamite Period

The Middle Elamite period began with the rise of the Anshanite dynasties around 1500 BCE. Their rule was characterised by an "Elamisation" of Susa, and the kings took the title "king of Anshan and Susa". While the first of these dynasties, the Kidinuids continued to use the Akkadian language frequently in their inscriptions, the succeeding Igihalkids and Shutrukids used Elamite with increasing regularity. Likewise, Elamite language and culture grew in importance in Susiana.

The Kidinuids (c. 1500–1400) are a group of five rulers of uncertain affiliation. They are identified by their use of the older title, "king of Susa and of Anshan", and by calling themselves "servant of Kirwashir", an Elamite deity, thereby introducing the pantheon of the highlands to Susiana.

Of the Igihalkids (ca. 1400–1210), ten rulers are known, and there were possibly more. Some of them married Kassite princesses. The Kassite king Kurigalzu II temporarily occupied Elam c. 1320 BC, and later (c. 1230) another Kassite king, Kashtiliash IV, fought Elam unsuccessfully. Kidin-Hutran I of Elam repulsed the Kassites by defeating Enlil-nadin-shumi in 1224 and Adad-shuma-iddina around 1222-17. Under the Igihalkids, Akkadian inscriptions were rare, and Elamite highland gods became firmly established in Susa.

Under the Shutrukids (c. 1210–1100), the Elamite empire reached the height of its power. Shutruk-Nahhunte and his three sons, Kutir-Nahhunte II, Shilhak-Inshushinak, and Khutelutush-Inshushinak were capable of frequent military campaigns into Kassite Mesopotamia, and at the same time were exhibiting vigorous construction activity -- building and restoring luxurious temples in Susa and across their Empire. Shutruk-Nahhunte raided Akkad, Babylon, and Eshnunna, carrying home to Susa trophies like the statues of Marduk and Manishtushu, the code of Hammurabi and the stele of Naram-Sin.

In 1158 BC, Shutruk-Nahhunte defeated the Kassites permanently, killing the Kassite king of Babylon, Zababa-shuma-iddina, and replacing him with his eldest son, Kutir-Nahhunte, who held it no more than three years.

Kutir-Nahhunte's son Khutelutush-Inshushinak was the last king of the Shutrukids. He was probably of an incestuous relation of Kutir-Nahhunte's with his own daughter, Nahhunte-utu. He ended up temporarily yielding Susa to the forces of Nebuchadnezzar I of Babylon, who returned the statue of Marduk. He fled to Anshan, but later returned to Susa, and his brother Shilhina-Hamru-Lagamar may have succeeded him. Following Khutelutush-Inshushinak, the power of the Elamite empire began to wane seriously, for with this ruler, Elam disappears into obscurity for more than three centuries.

Neo-Elamite Period

Neo-Elamite I (c. 1100–770)

Very little is known of this period. Anshan was still at least partially Elamite. There appear to have been alliances of Elam and Babylonia against the Assyrians; the Babylonian king Mar-biti-apla-ushur (984—79) was of Elamite origin, and Elamites are recorded to have fought with the Babylonian king Marduk-balassu-iqbi against the Assyrian forces under Shamshi-Adad V (823–11).

Neo-Elamite II (c. 770–646)

The later Neo-Elamite period is characterised by a significant migration of Iranians to the Iranian plateau. Assyrian sources beginning around 800 BC distinguish the "powerful Medes", ie the actual Medes, and the "distant Medes" that would later enter history under their proper names, (Parthians, Sagartians, Margians, Bactrians, Sogdians etc). This pressure of immigrating Iranians pushed the Elamites of Anshan towards Susa, so that in the course ot this period, Susiana became known as Elam, while Anshan and the Iranian plateau, the original home of the Elamites, were renamed Persia proper. The Elamite kings, apart from the last three, nevertheless continued to claim the title of "king of Anshan and Susa".

More details of an alliance of Babylonia and Elam against Assyria are tangible from the late 8th century BC. Humban-nikash (743–17) supported Merodach-baladan against Sargon II, apparently with limited success; while his successor, Shutruk-Nahhunte II (716–699), was routed by Sargon's troops during an expedition in 710, and another Elamite defeat by Sargon's troops is recorded for 708. The Assyrian victory was completed by Sargon's son Sennacherib, who dethroned Merodach-baladan and installed his own son Assur-nadin-shumi on the throne of Babylon.

Shutruk-Nahhunte was murdered by his brother Hallushu, who managed to capture Assur-nadin-shumi, and was in turn assassinated by Kudur -- who succeeded him, but soon abdicated in favour of Humban-umena III (692–89). Humban-umena recruited a new army to help the Babylonians against the Assyrians at the battle of Halule in 691 BC. The battle was indecisive, or at least both sides claimed the victory in their annals, but Babylon fell to the Assyrians only two years later. The reigns of Humban-haltash I (688–81) and Humban-haltash II (680–75) saw a deterioration of Elamite-Babylonian relations, and both of them raided Sippar. Urtak (674–64) for some time maintained good relations with Assurbanipal (668&ndsah;27), who sent wheat to Susiana during a famine. But these friendly relations were only temporary, and Urtak died during another Elamite attack on Mesopotamia.

His successor Te-Umman (664–53) was counter-attacked by Assurbanipal, and was killed following the battle of the Ulaï in 653 BC; and Elam was occupied by the Assyrians. During a brief respite provided by the civil war between Assurbanipal and his brother Shamash-shum-ukin, the Elamites too indulged in fighting among themselves, so weakening the Elamite kingdom that in 646 BC Assurbanipal devastated Susiana with ease, and sacked Susa. A succession of brief reigns continued in Elam from 651 to 640, each of them ended either due to usurpation, or because of capture of their king by the Assyrians. In this manner, the last Elamite king, Humban-Haldash III, was captured in 640 BC by Ashurbanipal, who devastated the country.

In a tablet unearthed in 1854 by Henry Austin Layard, Ashurbanipal boasts of the destruction he had wrought:

- "Susa, the great holy city, abode of their Gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed...I destroyed the ziggurat of Susa. I smashed its shining copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated, I exposed to the sun, and I carried away their bones towards the land of Ashur. I devastated the provinces of Elam and on their lands I sowed salt." (Persians: Masters of Empire, p7-8, ISBN 0-80949104-4)

Neo-Elamite III (646–539)

The devastation was however less complete than Assurbanipal boasted, and Elamite rule was resurrected soon after with Shutur-Nahhunte, son of Humban-umena III (not to be confused with Shutur-Nahhunte, son of Indada, a petty king in the first half of the 6th century). Elamite royalty in the final century preceding the Achaemenids was fragmented among different small kingdoms, The three kings at the close of the 7th century (Shutur-Nahhunte, Hallutash-Inshushinak and Atta-hamiti-Inshushinak) still called themselves "king of Anzan and of Susa" or "enlarger of the kingdom of Anzan and of Susa", at a time when the Achaemenids were already ruling Anshan. Their successors Ummanunu and Shilhak-Inshushinak II bore the simple title "king," and the final king Tepti-Humban-Inshushinak boasted no title altogether. In 539 BC, Achaemenid rule begins in Susa.

Elamite language

- Main article: Elamite language

Elamite is unrelated to the neighbouring Semitic, Sumerian and Indo-European languages. It was written in a cuneiform adapted from Akkadian script, although the very earliest documents were written in the quite different "Linear Elamite" script. This seems to have developed from an even earlier writing known as "proto-Elamite", but scholars are not unanimous on whether or not this script was used to write Elamite or another language, and it has not yet been deciphered.

Some linguists believe Elamite may be related to the living Dravidian languages (of southern India, and Brahui in Pakistan). The hypothesised family of Elamo-Dravidian languages may further prove to be connected with the Indus Valley Civilisation somewhat to the East, possibly corresponding to Meluhha in Sumerian records. However, such links are at best conjectural, and Harappan pictographs have also yet to be deciphered.

Several stages of the language are attested; the earliest date back to the third milennium BC, the latest to the Achaemenid Empire.

The Elamite language may have survived as late as the early Islamic period. Ibn al-Nadim among other Arab medieval historians, for instance, wrote that "The Iranian languages are Fahlavi (Pahlavi), Dari, Khuzi, Persian and Suryani", and Ibn Moqaffa noted that Khuzi was the unofficial language of the royalty of Persia, "Khuz" being the corrupted name for Elam. See Origin of the name Khuzestan for details.

The Elamite Legacy

The Assyrians thought that they had utterly destroyed the Elamites, but new polities emerged in the area after Assyrian power faded. However, they never again exercised the power of the earlier Elamite empires; they controlled the watershed of the Karun and little beyond. Among the nations that benefitted from the decline of the Assyrians were the Persians, whose presence around Lake Urmia to the north of Elam is attested from the ] in Assyrian texts. Some time after that region fell to Madius the Scythian (653 BC), Teispes son of Achaemenes conquered Elamite Anshan in the mid 7th century BC, forming a nucleus that would expand into the Persian Empire.

Elamite influence on the Achaemenids

The rise of the Achaemenids in the 6th century BC brought an end to the existence of Elam as an independent political power "but not as a cultural entity" (Encyclopedia Iranica, Columbia University). Indigenous Elamite traditions, such as the use of the title "king of Anshan" by Cyrus the Great; the "Elamite robe" worn by Cambyses I of Anshan and seen on the famous winged genii at Pasargadae; some glyptic styles; the use of Elamite as the first of three official languages of the empire used in thousands of administrative texts found at Darius’ city of Persepolis; the continued worship of Elamite deities; and the persistence of Elamite religious personnel and cults supported by the crown, formed an essential part of the newly emerging Achaemenid culture in Persian Iran. The Elamites thus became the conduit by which achievements of the Mesopotamian civilisations were introduced to the tribes of the Iranian plateau.

According to the editors of Persians, Masters of Empire: "The Elamites, fierce rivals of the Babylonians, were precursors of the royal Persians" (ISBN 0-80949104-4). This view is widely accepted today, as experts unanimously recognise the Elamites to have "absorbed Iranian influences in both structure and vocabulary" by 500 BC. (Encyclopedia Iranica, Columbia University)

The Elamite civilisation's originality, coupled with studies carried out at Elamite sites well spread out over the Iranian plateau, have led modern historians to conclude that "The Elamites are the founders of the first Iranian empire in the geographic sense". (Elton Daniel, The History of Iran, p. 26)

Most experts go even further and establish a clear chain of cultural continuity between the Elamites and later dynasties of Iran. Elamologist DT Potts verifies this in writing, "There is much evidence, both archaeological and literary/epigraphic, to suggest that the rise of the Persian empire witnessed the fusion of Elamite and Persian elements already present in highland Fars". (The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State, Cambridge World Archaeology, Chap 9 Introduction.).

Thus, not only was "Elam absorbed into the new empire" (Encyclopedia Iranica, Columbia University), becoming part of the millennia old imperial heritage of Iran, but the Elamite civilisation is now recognised to be "the earliest civilization of Persia", in the words of Sir Percy Sykes. (A History of Persia, p38, ISBN 0415326788).

Post Achaemenid influence

Traditional histories have ended Elamite history with its submergence in the Achaemenids, but Greek and Latin references to "Elymeans" attest to cultural survival, according to Daniel Potts. The traditional name "Elam" appears as late as 1300 in the records of the Nestorian Christians.

Elamite studies

In a 2001 talk, Basello Gian Pietro (Istituto Universitario Orientale, Naples) stated:

- While even today the languages play a basic role in our schematisation and teaching of the past, this stepchild shows us how frail the boundaries of our academic subjects are. While ancient Elamites fought against Assyrians and rebelled against Persians, Elamite studies are strictly bound to Assyriology and Iranian studies. As ancient Elam stood and represented a meeting place between Mesopotamian lowland and Iranian highland, so Elamite studies need to grab and grasp data both from Assyriology and Iranian studies and through many fields of work.

- Unfortunately, missing an independent academic subject, we have little specific teaching of Elamite studies. As we employ a foreign designation in referring to ancient Anšan and Susiana, Elamite scholars are often Assyriologists, Iranists or Linguists in their academic background, i.e. they have approached Elam later and from an external point of view.

As opposed to the typical view that Elam is of interest only for its contributions to Iranian or Assyrian culture, or for its unique language, some scholars feel that Elam should be studied in its own right, and not annexed to another cultural tradition.

See also: Historiography and nationalism

See also

- Elamite language

- List of rulers of Elam

- Full list of Iranian Kingdoms

- Ilam Province

- Khuzestan

- Origin of the name Khuzestan.

- Roman Ghirshman

External links

- Elam article of the Encyclopædia Iranica

- History of the Elamite Empire

- Elamite Art

- All Empires - The Elamite Empire

- Elam in Ancient Southwest Iran

- Iran Before Iranians

- Establishment of Elamite Museum in Iran

- Translations of Elamite Persepolis Inscriptions to be Published in the U.S.

- Encyclopedia Britannica's article on Proto-Elamites

References

- Khačikjan, Margaret: The Elamite Language, Documenta Asiana IV, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Istituto per gli Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici, 1998 ISBN 8887345015

- Persians: Masters of Empire, Time-Life Books, Alexandria, VA (1995) ISBN 0809491044

- Potts, Daniel T.: The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State, Cambridge University Press (1999) ISBN 0521564964 and ISBN 0521563585