| Revision as of 12:42, 1 October 2009 editJAnDbot (talk | contribs)Bots159,117 editsm robot Adding: lo:ກຳປັ່ນ← Previous edit | Revision as of 18:37, 2 October 2009 edit undoCharles Dawson (talk | contribs)125 editsm A Short History of the Camel, used for Raising Sunken ships or Imparting Additional Buoyancy to Vessels.Next edit → | ||

| Line 704: | Line 704: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| A Short History of the Camel, used for raising sunken ships or imparting additional buoyancy to vessels. | |||

| The entry for "camel" in the Oxford English Dictionary gives two meanings to the device: | |||

| 1) for raising sunken ships, removing rocks, etc. | |||

| 2) for imparting additional buoyancy to vessels and thus enabling them to cross bars, shoals, etc., otherwise impassible. | |||

| RAISING SUNKEN SHIPS, etc | |||

| An important technique without which sunken ships could hardly be raised is that of diving, and this was known in ancient times in the Mediterranean area. Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) described how pearl-divers divers used up-ended pots to give them an air-supply under water. | |||

| Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), in his notebooks described how air could be used to raise sunken objects: "We shall show how air can be forced under water to lift very heavy weights, or how one can fill leather bags with air after they have been fastened to weights on the sea-bottom". Leonardo however, contrary to his general practice, appears to have made no drawings to accompany his notes. Leonardo may have been aware of the earlier work of the Romans in underwater operations; particularly diving for the purpose of salvaging cargo was known to them , but it is not certain that they ever raised complete vessels. | |||

| The Venetians from about the fifth century AD showed a great capacity for self preservation using their underwater techniques in building their city on piles, and developing their great ability as navigators and merchants in faraway lands. By the 15th century, contacts between Venice and England had become well established. John Cabot (c 1450-1498), the Venetian navigator, was in the service of England when he and his son Sebastian (1477-1557) discovered Labrador in 1497. In their case, Bristol was their base in southwest England, but in the south of England there was also a valuable connection. The area around Southampton, England, had a long tradition of supplying compass timber, the naturally curved shapes used in shipbuilding, to the Mediterranean. This, together with timber from other areas, was shipped via the Solent to the Mediterranean in Venetian galleys, so contacts between these two areas also became well-established. | |||

| It is therefore not surprising to find the Venetians being consulted over the problem of recovering Henry VIII's prestigious warship Mary Rose after her disastrous sinking off Portsmouth on the Solent on 19 July 1545. It was to the two Venetian experts Peter de Andreas and Simon de Marine that the English naval and military commanders delegated the task of recovering the ship. The proposed salvage, arranged only twelve days after she sank, was put in hand almost immediately. As buoyancy elements, two empty ships each of 700 tons burthen, Jesus of Lübeck and Samson were to be moored on either side of Mary Rose and secured to her by strong cables. At low water, the cables were to be hauled tight on the capstans and as the tide rose the buoyant empty ships would rise with it, bringing Mary Rose off the bottom. Unfortunately, in the event the experts had been unable to pass cables underneath her, but only to tie them to three of her four masts. The schedule of the equipment required was impressive: besides the hulks and hoys, and cables, capstans and cordage, there were listed "thirty Venetian mariners, one Venetian carpenter and sixty English mariners to attend upon them". | |||

| Despite this formidable array of manpower and equipment, the salvage attempt failed; they succeeded only in pulling out the ship's mainmast in the attempted lift, although the two Venetians did receive 40 marks from the Treasurer of the Chamber for their efforts. Some individual items were recovered during the following four years, but after that, attempts to salvage the ship were abandoned until she was finally rediscovered in 1971 and later raised. | |||

| CROSSING BARS, SHOALS, etc. | |||

| It was the requirement to cross specific bars that led to the technique using the "camel", developed in the Netherlands at the end of the seventeenth century. The main aim here will be to examine when, where, why and how this specific type of camel was invented, developed and used, and how other countries adopted the method for use in similar conditions. | |||

| In beginning the attempt to discover a specific "inventor" of the camel, it is as well to remember that the tendency to give recognition to individuals for the discovery of many of the advances of industrial society is often merely a convenient way of paying due homage to the person who brought about the crucial breakthrough, or put into practical application the final stage of a long process. Many of the contributors along the way are simply forgotten: "losers" are not news. Ironically, the "winners" are sometimes picked out on purely chauvinistic grounds. It has for example been suggested that the English may have created an apocryphal story about a hulk named Camel in order to claim credit for the invention. Although the Venetians had expertise in the technique of lifting ships, even if it was not always successfully used, it is to the Netherlands that credit must be given for the camel in its more or less finally developed form. For her, necessity had in fact become the mother of invention, as we shall see. | |||

| Technical change in many fields has often as not been connected with the struggle for power between nations, and the Dutch camel is no exception. The Dutch were the first great European maritime trading nation of modern times: they dominated overseas commerce for well over a century, starting from the time when Portugal was united with Spain in 1580. From that date, the Dutch were excluded from the profitable re-export trade of oriental goods from Lisbon to the rest of Europe, which previously had mainly been in their hands. However, the great advantage they had in the economy of design of operation of their trading vessels helped them overcome this temporary setback. On this matter of general efficiency Sir Walter Raleigh complained in 1603 that where an English ship of 100 tons needed a crew of thirty, a corresponding Dutch ship could make do with ten. | |||

| By the beginning of the 17th century the Dutch had over 10,000 merchantmen of different kinds, the most important being the fluyt, a round-sterned flat-bottomed and relatively narrow vessel, designed for efficiency. With this, they were able to dominate the important Baltic trade. The design of this vessel, with its sides sloping sharply inwards, gave it a distinct advantage when passing into the Baltic through the Sound. There, duty was based on tonnage, which was largely relative to the vessel's bulk amidships. Dutch shipbuilding yards were objects of admiration visited by many Europeans bent on learning about their methods. At this time Holland had by far the largest shipping fleet of all the major European seafaring nations and Amsterdam was the major port serving it. During the second half of the seventeenth century, the Netherlands was building new vessels at the rate of some two thousand a year. By the end of the century, she possessed a commercial fleet of 20,000 vessels totalling 900,000 tons compared to the only half a million tons of England and two million divided among the rest of the European countries. | |||

| In order to protect her commercial fleet, the Netherlands, during the last few years of the 17th century, was building new warships at a tremendous rate; between 1682 and 1700 she built 172, but by the end of the 17th century she had reached the peak of her sea power. A sure sign of this was that, between 1703 and 1745, she built only three. After that, the size of ships having reached a peak, she began to suffer from the lack of harbors with sufficient depth of water to take them. Ships entering these too-shallow harbors were restricted to a tonnage of no more than 700, while larger vessels had to be kept more or less perpetually upon the high seas. | |||

| From the beginning of the 18th century, the commercial power of the Netherlands began to be challenged by the growing power of England and France. With their wide and deep harbours by that time they were able to construct three-deckers of 100 guns measuring over 1500 tons with a crew of over 750 men. This new challenge to the sea power of the Netherlands came just at the time when the specific conditions for entry to the port of Amsterdam began to deteriorate at an ever-increasing rate. In fact, cause and effect are here so closely interwoven, that it could be said that her shallow harbours played a large part in starting the decline of the Netherlands as a great sea-power at the end of the seventeenth century. | |||

| A glance at the map of the Netherlands is sufficient to make us marvel at the importance of Amsterdam as a harbour, when we see the difficulties of access to it. At the end of the 17th century, it still had no outlet westwards to the sea by canal, although it was blessed with a fine natural harbour. Ships had first to enter the dangerous waters of the Marsdiep off the town of Den Helder, or the Vlie Stroom past the island of Terschelling, then cross the Zuider Zee, only to be hampered about six miles from Amsterdam. Here there were two sandbanks between which was a passage, named "Pampus" , which was sufficiently deep only for small ships with a depth of no more than 9 to 13 feet depending on the tide. One way for larger ships to avoid the shallows altogether was to unload them into lighters in the Marsdiep or the Vlie Stroom and come up to Amsterdam empty. Fig.1. | |||

| Every possible method was tried to overcome the obstacle created by Pampus. Looking first to changes in the design of the craft themselves, experiments were made with flat keels, and broader ships, but all to no avail. Turning their attention to legislation, the port authorities exercised strict control in an attempt to reduce the silting up of the harbours. However, they were fighting a losing battle. Despite regulations that had been in force as early as the sixteenth century forbidding ballast to be dumped into the passage, Pampus continued to silt up and became increasingly shallower, while ships were becoming increasingly larger. | |||

| It was at this stage that ideas for physically carrying vessels over the shallows began to be developed. Johan Beckmann described in 1782 how, by about 1672, a rudimentary form of flotation device had come into use by the Dutch although getting the fleet to sea using it was attended with the utmost difficulty. An earlier writer, Caspar Commelin, had referred to this in 1726. The principle was that large rectangular chests filled with water were made fast to the ship by cables, and the water pumped out so that the ships were buoyed up sufficiently to pass over the shallow. These writers name no specific inventor of this system. However, the German historian of technology, Jacob Leupold (1674-1727) attributes it to the Dutch civil engineer Cornelius Meijer, and uses the term 'camel' in describing it, perhaps being the first to do so in print in a German technical text. | |||

| Meijer was sufficiently renowned for his work in Holland to have later been invited to Rome by the Apostolic Chamber to render the River Tiber navigable. Some of his plans were carried out, but the most important and greater part of them was never adopted. The reasons, he claimed, were 'chiefly through the jealousy of the Romans'. To do himself justice and prevent others from claiming his inventions, he published a book in Rome in 1683 as a riposte. It is an impressive work ranging widely over the civil engineering field. His disdain over his treatment did not prevent Meijer's son Otto, who followed his father's profession, later working under Pope Clement XI, during the latter's papacy, 1700-1721. | |||

| Meijer senior in his book, dedicated to Pope Innocent XI, (Pope 1676-1689), proposed, among many other things, a method for lifting a ship by the use of a single shaped support under the hull of the ship. In effect, this was a rudimentary form of floating dock, Fig. 2. He describes the process: Screws C are fitted in the walls of A, to submerge B. the ship D is sailed into B, the doors of A (not shown) are closed and all the water that could have entered is pumped out. This frees the hull to enable the ship to be dealt with. | |||

| Meijer apparently never took this idea further, but it can perhaps be considered as the starting point for the further development that produced the double, pumpable version that came to be the camel proper. This was the work of another engineer Dutchman, Meeuwen Meindertszoon Bakker, of whom, unfortunately, little information is available, but is believed to have been born in Amsterdam in about 1640/1. By about 1690, Bakker had begun to put his ideas into practice in the following few years, during which he obtained employment in the Admiralty. It was probably he who adopted the word camel (kameel in Dutch) to describe his invention. He no doubt likened the slow motion of the vessel, when being lifted, to the way in which the live "ship of the desert" raises itself, after having its load strapped to both flanks; not to mention its enormous water capacity. Bakker was presumably aware of, and could well have been inspired by, the earlier work of Meyer. | |||

| Bakker's camel comprised a pair of specially shaped wooden boxes - a right-hand half and a left-hand half making a pair - on the inside of which the exterior form was a "negative", so to say, of that of the general shape of a ship's hull, to give as snug a fit as possible. The boxes were built up of a series of shaped ribs, which were finally planked, much as in ship construction. Each box was divided into several compartments - as many as seven for the largest - and each could be flooded or pumped dry separately, for ease of control. Several sizes of camel were constructed to suit different sizes of ship. If the ship to be lifted was long, a series of camels in tandem could be used. Leupold shows a cross-section of the camels B and C, the windlasses d by which the suspension cables efe support the ship A while the water is being pumped out by the pumps g, Fig. 3. | |||

| Beckmann describes the procedure: On the deck of each part of the camel there are a great many horizontal windlasses from which ropes proceed, through openings in the one half, and, being carried under the keel of the vessel, enter like openings in the other, from which they are conveyed to the windlasses on deck. When they are to be used, as much water as may be necessary is suffered to run into them; all the ropes are cast loose; the vessel is conducted between them; and large beams are placed horizontally through the port-holes, with their ends resting on the camel on each side. When the ropes are made fast, so that the ship is secured between the two parts of the camel, the water is pumped from it; and it then rises, and raises the ship along with it. An East India ship drawing 15' could be lightened by 4' and the heaviest warships by sufficient to pass without obstruction all the sandbanks of the Zuider Zee. | |||

| There is a general description of Bakker's work in a book of 1697 by the Dutch ship carpenter Cornelis van Ijk, together with probably the first illustrations of the camel ever published, Fig. 4. However, some specific information had already been presented by Caspar Commelin on the first trial in 1690 under the supervision of Bakker on a vessel. This had been carried out on the 170-foot long, 92 gun Dutch warship Princes Maria, when she was successfully lifted over Pampus in April 1690. For this, Bakker was awarded an annuity by the Amsterdam Admiralty. | |||

| Beckmann refers to a still-preserved testimony of Bakker himself, in which he gives June 1692 as the date when he conveyed, in the space of twenty four hours, the 156' long warship Maagt van Enkhuysen from 'Enkhuizen on the Zuider Zee to a place where there was sufficient depth'. He added that this could have been done much more quickly had not a perfect calm prevailed. Also mentioned is his raising in 1693 of a ship called Unie by a height of six feet and once again 'conducting her to a place of safety'. A warning is added by Beckmann that the method seems not to be without the danger of straining the timbers of large vessels so raised. | |||

| A ship cradled so tightly between the camel pair could, naturally, not sail in the normal way; any sails set were intended only to give stability, so the cradled ship had to be towed. There was a special compartment for the crew at the after end of the camel, from where they could steer when under way, using massive rudders. Fishermen from Marken, a small island in the Zuider Zee, north east of Amsterdam were usually given the task of towing the equipage over Pampus, using several in line of the type of craft known as 'waterships'. An engraving of 1691 depicts such a line of these sailing tugs. Their hulls were so well designed that leeboards, almost a basic requirement for the smaller flat-bottomed boats of Holland, were not necessary. These vessels had an open water compartment, known as a bun, in which newly caught fish could be kept alive, and it is from this that their name derives. They were also used for carrying fresh water into Amsterdam, a feature that was said to enhance their sailing qualities, presumably by giving them added stability, when they were used as tugs for camel-cradled ships. Three or four of them working together were said to be capable of towing a vessel through mud as deep as some four feet. | |||

| Two companies in Amsterdam, known appropriately as the Big and the Small were entrusted with the towing. The former owned fifteen boats and the latter, three. The Big Company however towed only its own ships and those of the Rotterdam Admiralty and the Dutch East India Company, while the Small Company took care of all other customers, which even included the Greenland whalers. The service was expensive: towing a man-of-war over Pampus in camels cost 225 guilders at a time when a ship's carpenter earned between 0.5 and 0.75 guilders per day, depending on the season. | |||

| Later the government took over control of both companies and remained in control until after the Noord-Hollandsch Canal was completed in 1824, Fig.1. This gave direct access to the North Sea, whereupon the necessity for camels here virtually disappeared. The journey via this canal to the North Sea, however, was not free of problems. For reasons of economy, the canal had been formed by connecting a series of existing waterways, which resulted in a canal with many twists and turns. According to one legend, the sermon in one of the churches on the route was disturbed one Sunday by the bowsprit of a clipper ship coming through a window of the church. Only when the North Sea Canal to IJmuiden was completed in 1876, Fig. 1, did Amsterdam have its long-desired effective direct connection with the North Sea. | |||

| The idea of the camel spread fairly rapidly from the Netherlands to other naval powers having waterways with similar problems. In Europe, these were mainly Russia, France and the Republic of Venice and, in the United States, specifically at Nantucket. | |||

| The history of the camel in each country is often highlighted by the date of the first use of the word that appears in their major national dictionaries. Surprisingly, in the case of English, Falconer's Marine Dictionary lags behind: his first edition of 1784 has no mention of the camel at all, although Burney's later revised version of it is quite explicit in giving details of its application in both Holland and Russia. | |||

| RUSSIA | |||

| In the case of Russia, the historical struggle for power that can be said to have contributed to her need for the camel hinged round Russia's aim to have access to the Baltic Sea. Ivan IV "the Terrible" (1530-1584) had begun the process when he gained it for a short time, through Livonia, to the Gulf of Riga. He lost it in the struggle with his main rivals in the Baltic, Sweden and Poland, and this led to his concentrating what fleet he had at Archangel, a port that the English Muscovy Company had helped to develop for its fur trade. | |||

| Over a century later, Peter the Great (1672-1725) renewed the struggle to gain control of the Baltic, by then firmly in the hands of Sweden. Peter aimed at winning back territory his country had lost in the war with Sweden of 1609-17 and realised that to entertain any hope of success, he must first begin to modernise his country in order to build up the necessary military and naval power. | |||

| First, however, he had turned his attention eastwards; in January 1695 he issued an order for a mobilisation against Turkey. It was after failing to take Azov by land that Peter began to build up a fleet with which to attack the enemy from the sea. Landowners and monasteries were taxed to bring in the necessary capital. Craftsmen were forcibly recruited and directed to the shores of the River Don. Material was requisitioned; whole forests were cut down. At the Voronetj yard, Peter himself helped to build the galley Principium, when, on 29 January 1696, he became sole tsar. Besides ordering warships from Holland, he brought in foreign naval officers to head his new fleet. After all these measures had brought victory at the storming of Azov in 1696, Peter could turn his attention westwards. | |||

| Peter already had Dutch shipbuilders helping him, but he induced other specialists to visit his country or to stay to practice. Peter himself ventured out on his own version of the Grand Tour, breaking the over 600 years-old tradition of Russian isolation; the previous regent to leave his country was the Grand Duke Izjaslav who visited the German king Heinrich IV in Mainz in 1075. Peter was to go incognito, but this secret could not always be maintained; there was an enormous corps of c. 250 representatives in his entourage. | |||

| Costs were to be covered by the barter of sable furs in the event of their gold running out. Peter's tour was to cover Amsterdam, Berlin, Vienna, Rome, Copenhagen, London and Venice. France was not to be included since Louis XIV had offered the Turks his help and was attempting to place his own representative on the Polish throne. The main interest of the European aristocrats in their Grand Tours was of course in studying classical antiquity, while Peter's interest lay largely in new technology, although he did include some "sightseeing", not to mention wassailing. His great interest, shipbuilding, he aimed to study mainly in Holland and England. | |||

| A banquet to celebrate the inauguration of the tour was held on 23 February 1697, but departure was held up until 10 March "for the punishment of traitors". The entourage was naturally enough not welcomed on their way through Swedish Latvia, especially when they arrived at Riga. They left on 10 March 1697 and arrived in Amsterdam on 7 August 1697. There, Peter stayed in a little house in Zaandam, and worked in a shipbuilding yard as carpenter on the frigate Peter and Paul. The entourage left for England on 7 January 1698 in Vice Admiral Mitchell's flagship York. | |||

| While in England Peter met Peregrine Osborne, the Marquis of Carmarthen, (1631-1712), then a Rear Admiral, who had designed the 6th rate, 18 gun, Royal Transport, 220 tons bm, 90' x 23½', built at Chatham Dockyard in 1695. She was renovated and given to Peter, "Czar of Muscovy", and handed over to a Dutch crew in London on 12 March 1698. Ostensibly this was given as a present, but it was in fact a covert bribe to induce Peter to grant England a tobacco monopoly, to compensate for the loss of privileges of the Muscovy merchants. | |||

| In April 1698 Peter was introduced to the English Captain John Perry (1670-1732), one of the many military and naval experts whom Peter recruited for service in Russia. First he had the task, as Peter's adviser, of accompanying him to Holland in Royal Transport later that month, escorted by Admiral Mitchell in his flagship Yorke. It was in Amsterdam that Peter and Perry saw the use of camels. Perry reported in his book that he stayed only seven or eight days in Amsterdam after which the Tsar, who was next to visit Vienna, sent him off to Narva in Russia. There he was to take up his appointment, having accepted Peter's offer to superintend the naval and civil engineering works which were then under progress or planned in Russia. Among the latter were several daring schemes for canal construction. Coupled with Perry's appointment was a promise of expenses, an annual salary of £300 and "liberal rewards if his work should prove of exceptional value". | |||

| Venice had to be missed from Peter's itinerary, despite minute preparations, because he was forced to return hastily to quell yet another uprising at home and after three weeks in Vienna, he arrived back in Moscow on 25 August 1698. In 1699 a row of peace agreements between Russia and Sweden were coming up for renewal but in 1700, before any action was taken, Peter, together with Denmark and Poland, declared war on Sweden. Peter made it one of his first tasks in attacking Sweden to break through Swedish Livonia and Esthonia to the Baltic. After his successes here, including capturing the capital of Esthonia, Reval (now Tallinn) he considered creating a new port at Rågövik further west. However, he decided against his scheme because he considered its position was too vulnerable. The territory that in 1703 he had wrested from Swedish Ingria at the head of the Gulf of Finland, where Sweden had founded the town Nyen in 1638, was ideal for Peter. It was here that he based his new capital, St. Petersburg "his window overlooking Europe". The term appears to have been coined, not by Pushkin as is often quoted, but by an earlier visitor to St. Petersburg, the Italian connoisseur of the Arts & Sciences, Count Francesco Algarotti, (1712-1764). He was on a visit to England in 1738 and from there embarked on Lord Baltimore's flagship Augusta at Gravesend for the Baltic. In his third letter to John, Lord Hervey, the English Vice Chamberlain, written from Cronstadt and dated 21 June 1739, Algarotti refers to camels "using the Dutch method". He describes their sailing from St. Petersburg, past Peterhof, the site of the Czar's summer palace some 25 miles west of his new capital, to Cronstadt, the Russian naval base conveniently some 25 miles west of St. Petersburg. He noted that it was the depth of water of only eight French pieds (c. 8.4 English feet), which necessitated the use of camels. Incidentally, the Italian word camelo (also camello, and even cammello) is, in a modern Italian dictionary, ascribed to Algarotti's use of the word in his letters. | |||

| Captain Perry* was involved in building the canals aimed at helping the transport of material to the shipyards near St.Petersburg. In his book there appears an inset to enlarged scale Fig. 5 showing particularly the channel from St. Petersburg to the naval base Cronstadt. At a later stage, after dredging had taken place, it was named the Morskoi Canal. Despite having the canal, ships built in the yards near St.Petersburg were specially constructed with a shallow depth (compare the frigates Samson and Fortuna, bought from Holland and England, of 4 metres depth with Olifant's 3.2 metres). | |||

| *Perry gradually discovered that the Tsar’s promises were of no great worth, and after repeated attempts at redress felt forced to put himself under the protection of the English Envoy, Mr.Whitworth and returned under his care to England in 1812, where he undertook important drainage work in the Fens. Samuel Smiles thought Perry important enough to include him in his book Lives of the Engineers, (London, 1861-2), 73-82. | |||

| Camels remained in use at Cronstadt for over a century. When the American paddle steamship Savannah arrived there in September 1819 after her pioneering crossing of the Atlantic, camels were used to enable her to enter the harbour. It was undoubtedly during his time in Russia that the word kamel was introduced into the Russian language. After the publication of the first version of Perry's book in London in 1716, which introduced the word in print in the English language, translations followed quickly: in both French and German in 1717. | |||

| FRANCE | |||

| At about the same time, the word first came into French as châmeau. Nicolas Aubin describes the camel, pointing out that the poor political relations between France and Holland at the time precluded any exchange of ideas between the two countries: the War of the League of Augsburg, 1688-1697, had just ended and the War of Spanish Succession, 1701-1714 was about to begin. The man who brought attention to the camel in France was the French Abbé Pierre Sartre, born in 1693. He paid a visit to the 86 year old Abbé Quesnel in Rotterdam between 22 July and 19 September 1719. In his description of his visit, he noted that in one shipbuilding yard, 1200 men worked from four o'clock in the morning to six o'clock in the evening. He describes the three-stage procedure by which ships were taken over Pampus by camel: 1, filling the camels with water and taking on the ships, 2, pumping out the camels to raise the ships over Pampus, and 3, refilling the camels with water. It is presumably from his report that the first use of the word camel in French is to be found. | |||

| Colbert Du Terron, intendent of Marine at La Rochelle, persuaded the Court, where his name carried great renown, that here was the best place in the world to make an excellent harbour and site for the construction of ships." They believed him and spent millions there. And when they had, La Rochelle was found to be so far from the sea, with an elbow and among other snags perhaps even more troublesome, and the tide, so low, that large vessels could not reach the sea. On top of that, they had to be off-loaded and needed a change of wind on the way. Its defects could easily have been foreseen, before the expenditure had been committed". | |||

| A later naval architect, Clairain-Deslauriers (1722-1780), a pupil of Duhamel du Monceau, became enthusiastic about the use of camels for transporting large warships, from the yards where they were built, out to sea. He was chief engineer at Rochefort between 1747 and 1778. Here, he was responsible for building, for example, the 92 gun Ville de Paris, launched on 19 January 1764. It was he who advised that Bordeaux and Bayonne were also suitable as shipbuilding centres, the first for vessels up to 74-80 guns and the latter, for up to 64 guns. At Bayonne, it was necessary to transport the ships on camels along the 16' deep channel to St.Jean de Luz before they could be sure of water of sufficient depth. By the time they reached Cape Figuer, they had 8 -12 fathoms of water and favourable easterly winds. | |||

| VENICE | |||

| In about 1700, Venice began also to have problems for their vessels in negotiating the Malamocco sandbank, Fig. 6. Here, it was Marco Vincenzo Coronelli (1650-1718) who introduced his versions of the camel. He simplified their construction by using straight timbers, instead of those specially curved to fit the profile of the ship's hull, Fig. 7. He was an extremely prolific and in his time renowned cosmographer and globe- maker who in 1684 had founded the Academia Cosmografica degli Argonauti, the first institute of its kind in Europe. In 1696 he sailed, as part of his projected tour of Europe, to England in English yachts with the Venetian ambassadors who were sent to confirm the Republic's recognition of William III. His way home took him via Amsterdam. Once back home in Venice, Coronelli was quick to impart the information he had gained, in his two-volume work. The illustrations in his book give due credit to the Dutch origin of the camel, in fact they closely resemble those of van Ijk. Coronelli also instructed a group of Russian noblemen on a course in maritime matters, including navigation. The Russians were part of the complete force of fifty, which had been commandeered by Peter to different parts of Europe for the purpose of study - at their own expense. | |||

| They took back home with them know-how, which Peter exploited in his war with Sweden, when he attacked the Swedish Baltic coast in 1719 with fast shallow draft galleys inspired by Venetian design. His aim was not conquest, but rather a way of speeding up the process of forcing Sweden to come to terms. His strategy succeeded, for Sweden was finally forced by the Treaty of Nystad of 1721 to relinquish her Baltic territories, only Finland being left to her. | |||

| Venice, because of its particular position, was faced with similar problems and ready to learn from the experience of others. Although Coronelli borrowed Bakker's idea of the camel, he adopted it to the specific needs of the port. He designed a number of different types of camel, his third, he claimed, being of less expensive construction, the basic framework being built up of straight, tangential members instead of the type slavishly following the form of the ship. Nor did he attempt to cover the full length of a ship with one snugly fitting pair of camels, but proposed that a string of shorter length camels could be used in just sufficient numbers to cover the length of the ship. This was a further way of standardising or rationalising the number of variants required. A rival to Coronelli was Benedetto Civran, who proposed two slightly different solutions, the main variations being the way in which the cables were disposed. Almost a century later, in 1808, a new era began under the French engineer Jean-Marguerite Tupinier, who was made Director of Naval Construction at Venice, now occupied by Napoleonic France. | |||

| USA | |||

| In the early 1800s, with the increasing size of whaling ships, it became difficult for them to cross the bar at the entrance to Nantucket harbour, Mass. The same problems that had arisen earlier at other harbours had repeated themselves here, and the same old alternative of partly unloading vessels outside the harbour was an equally time-consuming and costly affair. | |||

| A local captain, William Morris, had in 1827 proposed a solution on the lines of the traditional Dutch camel, and also suggested using wind driven pumps for filling the camels. It was Peter Folger Ewer (1800-1855) a Nantucket shipping merchant, who put forward his proposals. He was financed by fifty Nantucket people and the plans and construction were carried out by J.G. Thurber at Nantucket. | |||

| In the early summer of 1842 the first prototypes were completed and on 4 September the first tests were carried out on Christopher Mitchell & Co's whaleship Phoebe. Inside Brant Point the camels were placed in position and the water pumped into the hulls. The ship was hauled into place and the chains secured; the steamboat Telegraph put her hawsers aboard each of the camels and the towing began. Problems with weak chains were finally solved after some harassing months, when on 23 September Charles & Henry Coffin's whaleship Constitution was successfully towed out by the steamboat Telegraph and was able to sail for the Pacific under the command of Captain Obed. R Bunker. | |||

| Ewer's camels, 135' long were able at a signal from whaleships outside the harbour to manœuvre along the main channel under their own power to meet the oncoming ship. As they approached at a speed of some two knots, the camels separated and lengthened the loops of their fifteen heavy connecting chains until they sagged sufficiently to clear the keel of the whaleship. They then passed along underneath it until the whaler was well within. At this point, the water-gates of the camel were opened so that they could be filled with seawater. Once full, they sank below the surface of the water. The chains were then tightened by means of thirty windlasses, steam pumps pumped the water out of the camels at a rate of thirty barrels a minute and as the lightened camels rose, the ship became steady and secure between them, supported by the looped chains. | |||

| After the completion of the operation, the whaler, camels and all, could easily pass over the bar into the harbour, propelled by the engines of the camel and with the extra help of the flat-bottomed towing steamboat. This was in effect a floating dry-dock, which enabled large vessels to go right up to the wharf for unloading most of their cargo. Drawing only five feet of water, they had no problem in clearing the 7½ feet depth of water in the inner harbour, all that was available at low tide. Fig. 8. | |||

| ENGLAND | |||

| Edward Austin of London was granted British Patent No. 7372, 12 May 1837 for a system of raising sunken objects using flexible airtight bags, without the necessity of sending down divers or persons in diving bells. The bags were to be made from two surfaces of strong canvas, or other suitable fabric, combined with a layer of india-rubber ("according to the patent process of Mr. Macintosh" - obviously referring to the latter's British Patent of 1823). This basic material was then to be made up into bags of preferably cylindrical form with hemispherical ends using india-rubber cement. Flexible air and watertight tubes made of similar materials were to be fastened to the bags to force air into the bags when down below the water, in order to inflate them. Austin's shows a combination of chains drawn round a sunken ships by "creeping", using a series of buoys, together with purchase chains and shackles and a special design of a heavy metal stopper to ensure stability. | |||

| One of the finest detailed accounts in English of the use of camels, together with a number of other methods, appears in the report of the salvaging in 1844 of the British naval paddle-steamer sloop HMS Gorgon, 1111 tons bm, 178' x 37.5', launched at Pembroke on 31 August 1837. Apart from its technical interest, the account describes the outstanding tenacity, inventiveness and leadership of her captain Charles Hotham. This he displayed during the nearly six months, from 10 May to 30 October, during which he struggled to save his ship after she was driven ashore in a "Pampero" storm in Montevideo Bay. The camels were made on the spot to fit the particular contour of the ship. Besides the camels, he also used inflatable bags during his operation. | |||

| The most spectacular recent example of the use of camels was the lifting of the sunken Russian submarine “Kursk” in the Barents Sea in the autumn of 2001. | |||

| If we apply strictly the definition of a camel given by the Oxford English Dictionary, it could be taken to apply to any number of the more unusual methods for imparting additional buoyancy. One proposal for a patent covering the filling of the hull of a sunken vessel with table tennis balls is said to have been rejected on the grounds that the method had already | |||

Revision as of 18:37, 2 October 2009

For other uses, see Ship (disambiguation).

A ship Audio (US) is a large vessel that floats on water. Ships are generally distinguished from boats based on size and passenger capacity. Ships may be found on lakes, seas, and rivers and they allow for a variety of activities, such as the transport of people or goods, fishing, entertainment, public safety, and warfare.

Ships and boats have developed alongside mankind. In major wars, and in day to day life, they have become an integral part of modern commercial and military systems. Fishing boats are used by millions of fishermen throughout the world. Military forces operate highly sophisticated vessels to transport and support forces ashore. Commercial vessels, nearly 35,000 in number, carried 7.4 billion tons of cargo in 2007.

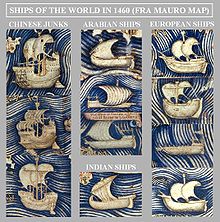

These vessels were also key in history's great explorations and scientific and technological development. Navigators such as Zheng He spread such inventions as the compass and gunpowder. Ships have been used for such purposes as colonization and the slave trade, and have served scientific, cultural, and humanitarian needs.

As Thor Heyerdahl demonstrated with his tiny boat the Kon-Tiki, it is possible to navigate long distances upon a simple log raft. From Mesolithic canoes to today's powerful nuclear-powered aircraft carriers, ships tell the history of human technological development.

Nomenclature

Ships can usually be distinguished from boats based on size and the ship's ability to operate independently for extended periods. A commonly used rule of thumb is that if one vessel can carry another, the larger of the two is a ship. As dinghies are common on sailing yachts as small as 35 feet (11 m), this rule of thumb is not foolproof. In a more technical and now rare sense, the term ship refers to a sailing ship with at least 3 square-rigged masts and a full bowsprit.

A number of large vessels are traditionally referred to as boats. Submarines are a prime example. Other types of large vessels which are traditionally called boats are the Great Lakes freighter, the riverboat, and the ferryboat. Though large enough to carry their own boats and heavy cargoes, these vessels are designed for operation on inland or protected coastal waters.

History

Further information: Maritime historyPrehistory and antiquity

The history of boats parallels the human adventure. The first known boats date back to the Neolithic Period, about 10,000 years ago. These early vessels had limited function: they could move on water, but that was it. They were used mainly for hunting and fishing. The oldest dugout canoes found by archaeologists were often cut from coniferous tree logs, using simple stone tools.

By around 3000 BC, Ancient Egyptians already knew how to assemble planks of wood into a ship hull. They used woven straps to lash the planks together, and reeds or grass stuffed between the planks helped to seal the seams. The Greek historian and geographer Agatharchides had documented ship-faring among the early Egyptians: "During the prosperous period of the Old Kingdom, between the 30th and 25th centuries B. C., the river-routes were kept in order, and Egyptian ships sailed the Red Sea as far as the myrrh-country." Sneferu's ancient cedar wood ship Praise of the Two Lands is the first reference recorded (2613 BCE) to a ship being referred to by name.

It is known that ancient Nubia/Axum traded with India, and there is evidence that ships from Northeast Africa may have sailed back and forth between India/Sri Lanka and Nubia trading goods and even to Persia, Himyar and Rome. Aksum was known by the Greeks for having seaports for ships from Greece and Yemen. Elsewhere in Northeast Africa, the Periplus of the Red Sea reports that Somalis, through their northern ports such as Zeila and Berbera, were trading frankincense and other items with the inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula well before the arrival of Islam as well as with then Roman-controlled Egypt.

The Swahili people had various extensive trading ports dotting the cost of medieval East Africa and Great Zimbabwe had extensive trading contacts with Central Africa, and likely also imported goods brought to Africa through the Southeast African shore trade of Kilwa in modern-day Tanzania.

At about the same time, people living near Kongens Lyngby in Denmark invented the segregated hull, which allowed the size of boats to gradually be increased. Boats soon developed into keel boats similar to today's wooden pleasure craft.

The first navigators began to use animal skins or woven fabrics as sails. Affixed to the top of a pole set upright in a boat, these sails gave early ships range. This allowed men to explore widely, allowing, for example the settlement of Oceania about 3,000 years ago.

The ancient Egyptians were perfectly at ease building sailboats. A remarkable example of their shipbuilding skills was the Khufu ship, a vessel 143 feet (44 m) in length entombed at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza around 2,500 BC and found intact in 1954. According to Herodotus, the Egyptians made the first circumnavigation of Africa around 600 BC.

The Phoenicians and Greeks gradually mastered navigation at sea aboard triremes, exploring and colonizing the Mediterranean via ship. Around 340 BC, the Greek navigator Pytheas of Massalia ventured from Greece to Western Europe and Great Britain.

Before the introduction of the compass, celestial navigation was the main method for navigation at sea. In China, early versions of the magnetic compass were being developed and used in navigation between 1040 and 1117. The true mariner's compass, using a pivoting needle in a dry box, was invented in Europe no later than 1300.

Through the Renaissance

Until the Renaissance, navigational technology remained comparatively primitive. This absence of technology didn't prevent some civilizations from becoming sea powers. Examples include the maritime republics of Genoa and Venice, and the Byzantine navy. The Vikings used their knarrs to explore North America, trade in the Baltic Sea and plunder many of the coastal regions of Western Europe.

Towards the end of the fourteenth century, ships like the carrack began to develop towers on the bow and stern. These towers decreased the vessel's stability, and in the fifteenth century, the caravel, a descendent of the Arabic qarib which could sail closer to the wind, became more widely used. The towers were gradually replaced by the forecastle and sterncastle, as in the carrack Santa María of Christopher Columbus. This increased freeboard allowed another innovation: the freeing port, and the artillery associated with it.

In the sixteenth century, the use of freeboard and freeing ports become widespread on galleons. The English modified their vessels to maximize their firepower and demonstrated the effectiveness of their doctrine, in 1588, by defeating the Spanish Armada.

At this time, ships were developing in Asia in much the same way as Europe. Japan used defensive naval techniques in the Mongol invasions of Japan in 1281. It is likely that the Mongols of the time took advantage of both European and Asian shipbuilding techniques. In Japan, during the Sengoku era from the fifteenth to seventeenth century, the great struggle for feudal supremacy was fought, in part, by coastal fleets of several hundred boats, including the atakebune.

During the Age of the Ajuuraan, the Somali sultanates and republics of Merca, Mogadishu, Barawa, Hobyo and their respective ports flourished and had a lucrative foreign commerce with ships sailing to and coming from Arabia, India, Venetia, Persia, Egypt, Portugal and as far away as China. In the 1500s, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya in what is modern-day India sailed to Mogadishu with cloths and spices, for which they in return received gold, wax and ivory. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.

Middle Age Swahili Kingdoms are known to have had trade port islands and trade routes with the Islamic world and Asia and were described by Greek historians are "metropolises". Famous African trade ports such as Mombasa, Zanzibar, and Kilwa were known to Chinese sailors such as Zheng He and medieval Islamic historians such as the Berber Islamic voyager Abu Abdullah ibn Battua. In the 14th century CE King Abubakari I, the brother of King Mansa Musa of the Mali Empire is thought to have had a great armada of ships sitting on the coast of West Africa. This is corroborated by ibn Battuta himself who recalls several hundred Malian ships off the coast. This has lead to great speculation, with historical evidence, that it is possible that Malian sailors may have reached the coast of Pre-Columbian America under the rule of Abubakari II, nearly two hundred years before Christopher Columbus and that black traders may have been in the Americas before Columbus.

Fifty years before Christopher Columbus, Chinese navigator Zheng He traveled the world at the head of what was for the time a huge armada. The largest of his ships had nine masts, were 130 metres (430 ft) long and had a beam of 55 metres (180 ft). His fleet carried 30,000 men aboard 70 vessels, with the goal of bringing glory to the Chinese emperor.

Specialization and modernization

Parallel to the development of warships, ships in service of marine fishery and trade also developed in the period between antiquity and the Renaissance. Still primarily a coastal endeavor, fishing is largely practiced by individuals with little other money using small boats.

Maritime trade was driven by the development of shipping companies with significant financial resources. Canal barges, towed by draft animals on an adjacent towpath, contended with the railway up to and past the early days of the industrial revolution. Flat-bottomed and flexible scow boats also became widely used for transporting small cargoes. Mercantile trade went hand-in-hand with exploration, self-financed by the commercial benefits of exploration.

During the first half of the eighteenth century, the French Navy began to develop a new type of vessel known as a ship of the line, featuring seventy-four guns. This type of ship became the backbone of all European fighting fleets. These ships were 56 metres (184 ft) long and their construction required 2,800 oak trees and 40 kilometres (25 mi) of rope; they carried a crew of about 800 sailors and soldiers.

Ship designs stayed fairly unchanged until the late nineteenth century. The industrial revolution, new mechanical methods of propulsion, and the ability to construct ships from metal triggered an explosion in ship design. Factors including the quest for more efficient ships, the end of long running and wasteful maritime conflicts, and the increased financial capacity of industrial powers created an avalanche of more specialized boats and ships. Ships built for entirely new functions, such as firefighting, rescue, and research, also began to appear.

In light of this, classification of vessels by type or function can be difficult. Even using very broad functional classifications such as fishery, trade, military, and exploration fails to classify most of the old ships. This difficulty is increased by the fact that the terms such as sloop and frigate are used by old and new ships alike, and often the modern vessels sometimes have little in common with their predecessors.

Today

In 2007, the world's fleet included 34,882 commercial vessels with gross tonnage of more than 1,000 tons, totaling 1.04 billion tons. These ships carried 7.4 billion tons of cargo in 2006, a sum that grew by 8% over the previous year. In terms of tonnage, 39% of these ships are tankers, 26% are bulk carriers, 17% container ships and 15% were other types.

In 2002, there were 1,240 warships operating in the world, not counting small vessels such as patrol boats. The United States accounted for 3 million tons worth of these vessels, Russia 1.35 million tons, the United Kingdom 504,660 tons and China 402,830 tons. The twentieth century saw many naval engagements during the two world wars, the Cold War, and the rise to power of naval forces of the two blocs. The world's major powers have recently used their naval power in cases such as the United Kingdom in the Falkland Islands and the United States in Iraq.

The size of the world's fishing fleet is more difficult to estimate. The largest of these are counted as commercial vessels, but the smallest are legion. Fishing vessels can be found in most seaside villages in the world. As of 2004, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimated 4 million fishing vessels were operating worldwide. The same study estimated that the world's 29 million fishermen caught 85.8 million metric tons of fish and shellfish that year.

Types of ships

Ships are difficult to classify, mainly because there are so many criteria to base classification on. One classification is based on propulsion; with ships categorised as either a sailing ship or a motorship. Sailing ships are ships which are propelled solely by means of sails. Motorships are ships which are propelled by mechanical means to propel itself. Motorships include ships that propel itself through the use of both sail and mechanical means.

Other classification systems exist that use criteria such as:

- The number of hulls, giving categories like monohull, catamaran, trimaran.

- The shape and size, giving categories like dinghy, keelboat, and icebreaker.

- The building materials used, giving steel, aluminum, wood, fiberglass, and plastic.

- The type of propulsion system used, giving human-propelled, mechanical, and sails.

- The epoch in which the vessel was used, triremes of Ancient Greece, man' o' wars, eighteenth century.

- The geographic origin of the vessel, many vessels are associated with a particular region, such as the pinnace of Northern Europe, the gondolas of Venice, and the junks of China.

- The manufacturer, series, or class.

Another way to categorize ships and boats is based on their use, as described by Paulet and Presles. This system includes military ships, commercial vessels, fishing boats, pleasure craft and competitive boats. In this section, ships are classified using the first four of those categories, and adding a section for lake and river boats, and one for vessels which fall outside these categories.

Commercial vessels

Commercial vessels or merchant ships can be divided into three broad categories: cargo ships, passenger ships, and special-purpose ships. Cargo ships transport dry and liquid cargo. Dry cargo can be transported in bulk by bulk carriers, packed directly onto a general cargo ship in break-bulk, packed in intermodal containers as aboard a container ship, or driven aboard as in roll-on roll-off ships. Liquid cargo is generally carried in bulk aboard tankers, such as oil tankers, chemical tankers and LNG tankers.

Passenger ships range in size from small river ferries to giant cruise ships. This type of vessel includes ferries, which move passengers and vehicles on short trips; ocean liners, which carry passengers on one-way trips; and cruise ships, which typically transport passengers on round-trip voyages promoting leisure activities onboard and in the ports they visit.

Special-purpose vessels are not used for transport but are designed to perform other specific tasks. Examples include tugboats, pilot boats, rescue boats, cable ships, research vessels, survey vessels, and ice breakers.

Most commercial vessels have full hull-forms to maximize cargo capacity. Hulls are usually made of steel, although aluminum can be used on faster craft, and fiberglass on the smallest service vessels. Commercial vessels generally have a crew headed by a captain, with deck officers and marine engineers on larger vessels. Special-purpose vessels often have specialized crew if necessary, for example scientists aboard research vessels. Commercial vessels are typically powered by a single propeller driven by a diesel engine. Vessels which operate at the higher end of the speed spectrum may use pump-jet engines or sometimes gas turbine engines.

-

Two modern container ships in San Francisco

Two modern container ships in San Francisco

-

A ferry in Hong Kong

-

A pilot boat near the port of Rotterdam

-

The research vessel Pourquoi pas? at Brest, France

Naval vessels

There are many types of naval vessels currently and through history. Modern naval vessels can be broken down into three categories: warships, submarines, and support and auxiliary vessels.

Modern warships are generally divided into seven main categories, which are: aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, frigates, corvettes, submarines and amphibious assault ships. Battleships encompass an eighth category, but are not in current service with any navy in the world.

Most military submarines are either attack submarines or ballistic missile submarines. Until World War II , the primary role of the diesel/electric submarine was anti-ship warfare, inserting and removing covert agents and military forces, and intelligence-gathering. With the development of the homing torpedo, better sonar systems, and nuclear propulsion, submarines also became able to effectively hunt each other. The development of submarine-launched nuclear missiles and submarine-launched cruise missiles gave submarines a substantial and long-ranged ability to attack both land and sea targets with a variety of weapons ranging from cluster bombs to nuclear weapons.

Most navies also include many types of support and auxiliary vessels, such as minesweepers, patrol boats, offshore patrol vessels, replenishment ships, and hospital ships which are designated medical treatment facilities.

Combat vessels like cruisers and destroyers usually have fine hulls to maximize speed and maneuverability. They also usually have advanced electronics and communication systems, as well as weapons.

-

American aircraft carrier Harry S. Truman and a replenishment ship

American aircraft carrier Harry S. Truman and a replenishment ship

-

American battleship USS Iowa fires an artillery salvo

American battleship USS Iowa fires an artillery salvo

-

French landing craft Rapière near Toulon

French landing craft Rapière near Toulon

Fishing vessels

Main article: Fishing vesselsFishing vessels are a subset of commercial vessels, but generally small in size and often subject to different regulations and classification. They can be categorized by several criteria: architecture, the type of fish they catch, the fishing method used, geographical origin, and technical features such as rigging. As of 2004, the world's fishing fleet consisted of some 4 million vessels. Of these, 1.3 million were decked vessels with enclosed areas and the rest were open vessels. Most decked vessels were mechanized, but two-thirds of the open vessels were traditional craft propelled by sails and oars. More than 60% of all existing large fishing vessels were built in Japan, Peru, the Russian Federation, Spain or the United States of America.

Fishing boats are generally small, often little more than 30 metres (98 ft) but up to 100 metres (330 ft) for a large tuna or whaling ship. Aboard a fish processing vessel, the catch can be made ready for market and sold more quickly once the ship makes port. Special purpose vessels have special gear. For example, trawlers have winches and arms, stern-trawlers have a rear ramp, and tuna seiners have skiffs.

In 2004, 85.8 million metric tons of fish were caught in the marine capture fishery. Anchoveta represented the largest single catch at 10.7 million metric tons. That year, the top ten marine capture species also included Alaska pollock, Blue whiting, Skipjack tuna, Atlantic herring, Chub mackerel, Japanese anchovy, Chilean jack mackerel, Largehead hairtail, and Yellowfin tuna. Other species including salmon, shrimp, lobster, clams, squid and crab, are also commercially fished.

Modern commercial fishermen use many methods. One is fishing by nets, such as purse seine, beach seine, lift nets, gillnets, or entangling nets. Another is trawling, including bottom trawl. Hooks and lines are used in methods like long-line fishing and hand-line fishing). Another method is the use of fishing trap.

-

Fishing boat in Cap-Haïtien, Haïti

Fishing boat in Cap-Haïtien, Haïti

-

A trawler at Saint-Nazaire

-

An oyster boat at La Trinité-sur-Mer

An oyster boat at La Trinité-sur-Mer

-

The Albatun Dos, a tuna boat at work near Victoria, Seychelles

The Albatun Dos, a tuna boat at work near Victoria, Seychelles

Inland and coastal boats

Many types of boats and ships are designed for inland and coastal waterways. These are the vessels that trade upon the lakes, rivers and canals.

Barges are a prime example of inland vessels. Flat-bottomed boats built to transport heavy goods, most barges are not self-propelled and need to be moved by tugboats towing or towboats pushing them. Barges towed along canals by draft animals on an adjacent towpath contended with the railway in the early industrial revolution but were out competed in the carriage of high value items because of the higher speed, falling costs, and route flexibility of rail transport.

Riverboats and inland ferries are specially designed to carry passengers, cargo, or both in the challenging river environment. Rivers present special hazards to vessels. They usually have varying water flows that alternately lead to high speed water flows or protruding rock hazards. Changing siltation patterns may cause the sudden appearance of shoal waters, and often floating or sunken logs and trees (called snags) can endanger the hulls and propulsion of riverboats. Riverboats are generally of shallow draft, being broad of beam and rather square in plan, with a low freeboard and high topsides. Riverboats can survive with this type of configuration as they do not have to withstand the high winds or large waves that are seen on large lakes, seas, or oceans.

Lake freighters, also called lakers, are cargo vessels that ply the Great Lakes. The most well-known is the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, the latest major vessel to be wrecked on the Lakes. These vessels are traditionally called boats, not ships. Visiting ocean-going vessels are called "salties." Because of their additional beam, very large salties are never seen inland of the Saint Lawrence Seaway. Because the largest of the Soo Locks is larger than any Seaway lock, salties that can pass through the Seaway may travel anywhere in the Great Lakes. Because of their deeper draft, salties may accept partial loads on the Great Lakes, "topping off" when they have exited the Seaway. Similarly, the largest lakers are confined to the Upper Lakes (Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie) because they are too large to use the Seaway locks, beginning at the Welland Canal that bypasses the Niagara River.

Since the freshwater lakes are less corrosive to ships than the salt water of the oceans, lakers tend to last much longer than ocean freighters. Lakers older than 50 years are not unusual, and as of 2005, all were over 20 years of age.

The St. Mary's Challenger, built in 1906 as the William P Snyder, is the oldest laker still working on the Lakes. Similarly, the E.M. Ford, built in 1898 as the Presque Isle, was sailing the lakes 98 years later in 1996. As of 2007 the Ford was still afloat as a stationary transfer vessel at a riverside cement silo in Saginaw, Michigan.

-

Riverboat Temptation on the Rhine

-

Riverboat Natchez on the Mississippi River

Riverboat Natchez on the Mississippi River

-

Commuter boat on the Seine

Commuter boat on the Seine

Other

The wide variety of vessels at work on the Earth's waters defy a simple classification scheme. A representative few that fail to fit into the above categories include:

- Historical boats, frequently used as museum ships, training ships, or as good-will ambassadors of a country abroad.

- Houseboats, floating structures used as dwellings.

- Scientific, technical, and industrial vessels such as mobile offshore drilling units, offshore wind farms, survey ships, and research vessels.

- Submarines, for underwater navigation and exploration

-

The Polish sailing frigate Dar Pomorza

The Polish sailing frigate Dar Pomorza

-

A houseboat near Kerala

-

A mobile offshore drilling unit in the Gulf of Mexico

A mobile offshore drilling unit in the Gulf of Mexico

-

A bathyscaphe at the oceanographic museum in Monaco

A bathyscaphe at the oceanographic museum in Monaco

Architecture

Further information: Naval architectureSome components exist in vessels of any size and purpose. Every vessel has a hull of sorts. Every vessel has some sort of propulsion, whether it's a pole, an ox, or a nuclear reactor. Most vessels have some sort of steering system. Other characteristics are common, but not as universal, such as compartments, holds, a superstructure, and equipment such as anchors and winches.

The hull

For a ship to float, its weight must be less than that of the water displaced by the ship's hull. There are many types of hulls, from logs lashed together to form a raft to the advanced hulls of America's Cup sailboats. A vessel may have a single hull (called a monohull design), two in the case of catamarans, or three in the case of trimarans. Vessels with more than three hulls are rare, but some experiments have been conducted with designs such as pentamarans. Multiple hulls are generally parallel to each other and connected by rigid arms.

Hulls have several elements. The bow is the foremost part of the hull. Many ships feature a bulbous bow. The keel is at the very bottom of the hull, extending the entire length of the ship. The rear part of the hull is known as the stern, and many hulls have a flat back known as a transom. Common hull appendages include propellers for propulsion, rudders for steering, and stabilizers to quell a ship's rolling motion. Other hull features can be related to the vessel's work, such as fishing gear and sonar domes.

Hulls are subject to various hydrostatic and hydrodynamic constraints. The key hydrostatic constraint is that it must be able to support the entire weight of the boat, and maintain stability even with often unevenly distributed weight. Hydrodynamic constraints include the ability to withstand shock waves, weather collisions and groundings.

Older ships and pleasure craft often have or had wooden hulls. Steel is used for most commercial vessels. Aluminium is frequently used for fast vessels, and composite materials are often found in sailboats and pleasure craft. Some ships have been made with concrete hulls.

Propulsion systems

Propulsion systems for ships and boats vary from the simple paddle to the largest diesel engines in the world. These systems fall into three categories: human propulsion, sailing, and mechanical propulsion. Human propulsion includes the pole, still widely used in marshy areas, rowing which was used even on large galleys, and the pedals. In modern times, human propulsion is found mainly on small boats or as auxiliary propulsion on sailboats.

Propulsion by sail generally consists of a sail hoisted on an erect mast, supported by stays and spars and controlled by ropes. Sail systems were the dominant form of propulsion until the nineteenth century. They are now generally used for recreation and racing, although experimental sail systems, such as the kites/royals, turbosails, rotorsails, wingsails, windmills and SkySails's own kite buoy-system have been used on larger modern vessels for fuel savings.

Mechanical propulsion systems generally consist of a motor or engine turning a propeller. Steam engines were first used for this purpose, but have mostly been replaced by two-stroke or four-stroke diesel engines, outboard motors, and gas turbine engines on faster ships. Electric motors have sometimes been used, such as on submarines. Nuclear reactors are sometimes employed to propel warships and icebreakers.

There are many variations of propeller systems, including twin, contra-rotating, controllable-pitch, and nozzle-style propellers. Smaller vessels tend to have a single propeller. Aircraft carriers use up to four propellers, supplemented with bow- and stern-thrusters. Power is transmitted from the engine to the propeller by way of a propeller shaft, which may or may not be connected to a gearbox.

Pre-mechanisation

Until the application of the steam engine to ships in the early 19th century, oars propelled galleys, or the wind propelled sailing ships. Before mechanisation, merchant ships always used sail, but as long as naval warfare depended on ships closing to ram or to fight hand-to-hand, galleys dominated in marine conflicts because of their maneuverability and speed. The Greek navies that fought in the Peloponnesian War used triremes, as did the Romans at the Battle of Actium. The use of large numbers of cannon from the 16th century meant that maneuverability took second place to broadside weight; this led to the dominance of the sail-powered warship.

Reciprocating steam engines

Main article: Marine steam engineThe development of piston-engined steamships was a complex process. Early steamships were fueled by wood, later ones by coal or fuel oil. Early ships used stern or side paddle wheels, while later ones used screw propellers.

The first commercial success accrued to Robert Fulton's North River Steamboat (often called Clermont) in the US in 1807, followed in Europe by the 45-foot Comet of 1812. Steam propulsion progressed considerably over the rest of the 19th century. Notable developments included the steam surface condenser, which eliminated the use of sea water in the ship's boilers. This permitted higher steam pressures, and thus the use of higher efficiency multiple expansion (compound) engines. As the means of transmitting the engine's power, paddle wheels gave way to more efficient screw propellers.

Steam turbines

Steam turbines were fueled by coal or, later, fuel oil or nuclear power. The marine steam turbine developed by Sir Charles Algernon Parsons raised the power to weight ratio. He achieved publicity by demonstrating it unofficially in the 100-foot Turbinia at the Spithead naval review in 1897. This facilitated a generation of high-speed liners in the first half of the 20th century and rendered the reciprocating steam engine obsolete, first in warships and later in merchant vessels.

In the early 20th century, heavy fuel oil came into more general use and began to replace coal as the fuel of choice in steamships. Its great advantages were convenience, reduced manpower by removal of the need for trimmers and stokers, and reduced space needed for fuel bunkers.

In the second half of the 20th century, rising fuel costs almost led to the demise of the steam turbine. Most new ships since around 1960 have been built with diesel engines. The last major passenger ship built with steam turbines was the Fairsky, launched in 1984. Similarly, many steam ships were re-engined to improve fuel efficiency. One high profile example was the 1968 built Queen Elizabeth 2 which had her steam turbines replaced with a diesel-electric propulsion plant in 1986.

Most new-build ships with steam turbines are specialist vessels such as nuclear-powered vessels, and certain merchant vessels (notably Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) and coal carriers) where the cargo can be used as bunker fuel.

LNG carriers

New LNG carriers (a high growth area of shipping) continue to be built with steam turbines. The natural gas is stored in a liquid state in cryogenic vessels aboard these ships, and a small amount of 'boil off' gas is needed to maintain the pressure and temperature inside the vessels within operating limits. The 'boil off' gas provides the fuel for the ship's boilers, which provide steam for the turbines, the simplest way to deal with the gas. Technology to operate internal combustion engines (modified marine two-stroke diesel engines) on this gas has improved, however, so such engines are starting to appear in LNG carriers; with their greater thermal efficiency, less gas is burnt. Developments have also been made in the process of re-liquefying 'boil off' gas, letting it be returned to the cryogenic tanks. The financial returns on LNG are potentially greater than the cost of the marine-grade fuel oil burnt in conventional diesel engines, so the re-liquefaction process is starting to be used on diesel engine propelled LNG carriers. Another factor driving the change from turbines to diesel engines for LNG carriers is the shortage of steam turbine qualified seagoing engineers. With the lack of turbine powered ships in other shipping sectors, and the rapid rise in size of the worldwide LNG fleet, not enough have been trained to meet the demand. It may be that the days are numbered for marine steam turbine propulsion systems, even though all but sixteen of the orders for new LNG carriers at the end of 2004 were for steam turbine propelled ships.

Nuclear-powered steam turbines

In these vessels, the reactor heats steam to drive the turbines. Partly because of concerns about safety and waste disposal, nuclear propulsion is rare except in some navy and specialist vessels such as icebreakers. In large aircraft carriers, the space formerly used for ship's bunkerage could be used instead to bunker aviation fuel. In submarines, the ability to run submerged at high speed and in relative quiet for long periods holds obvious advantages. A few cruisers have also employed nuclear power; as of 2006, the only ones remaining in service are the Russian Kirov class. An example of a non-military ship with nuclear marine propulsion is the Arktika class icebreaker with 75,000 shaft horsepower. Commercial experiments such as the NS Savannah proved uneconomical compared with conventional propulsion.

Reciprocating diesel engines

About 99% of modern ships use diesel reciprocating engines. The rotating crankshaft can power the propeller directly for slow speed engines, via a gearbox for medium and high speed engines, or via an alternator and electric motor in diesel-electric vessels.

The reciprocating marine diesel engine first came into use in 1903 when the diesel electric rivertanker Vandal was put in service by Branobel. Diesel engines soon offered greater efficiency than the steam turbine, but for many years had an inferior power-to-space ratio.

Diesel engines today are broadly classified according to

- Their operating cycle: two-stroke or four-stroke

- Their construction: Crosshead, trunk, or opposed piston

- Their speed

- Slow speed: any engine with a maximum operating speed up to 300 revs/minute, although most large 2-stroke slow speed diesel engines operate below 120 revs/minute. Some very long stroke engines have a maximum speed of around 80 revs/minute. The largest, most powerful engines in the world are slow speed, two stroke, crosshead diesels.

- Medium speed: any engine with a maximum operating speed in the range 300-900 revs/minute. Many modern 4-stroke medium speed diesel engines have a maximum operating speed of around 500 rpm.

- High speed: any engine with a maximum operating speed above 900 revs/minute.

Most modern larger merchant ships use either slow speed, two stroke, crosshead engines, or medium speed, four stroke, trunk engines. Some smaller vessels may use high speed diesel engines.

The size of the different types of engines is an important factor in selecting what will be installed in a new ship. Slow speed two-stroke engines are much taller, but the area needed, length and width, is smaller than that needed for four-stroke medium speed diesel engines. As space higher up in passenger ships and ferries is at a premium, these ships tend to use multiple medium speed engines resulting in a longer, lower engine room than that needed for two-stroke diesel engines. Multiple engine installations also give redundancy in the event of mechanical failure of one or more engines and greater efficiency over a wider range of operating conditions.

As modern ships' propellers are at their most efficient at the operating speed of most slow speed diesel engines, ships with these engines do not generally need gearboxes. Usually such propulsion systems consist of either one or two propeller shafts each with its own direct drive engine. Ships propelled by medium or high speed diesel engines may have one or two (sometimes more) propellers, commonly with one or more engines driving each propeller shaft through a gearbox. Where more than one engine is geared to a single shaft, each engine will most likely drive through a clutch, allowing engines not being used to be disconnected from the gearbox while others keep running. This arrangement lets maintenance be carried out while under way, even far from port.

Gas turbines

Many warships built since the 1960s have used gas turbines for propulsion, as have a few passenger ships, like the jetfoil. Gas turbines are commonly used in combination with other types of engine. Most recently, the Queen Mary 2 has had gas turbines installed in addition to diesel engines. Because of their poor thermal efficiency at low power (cruising) output, it is common for ships using them to have diesel engines for cruising, with gas turbines reserved for when higher speeds are needed however, in the case of passenger ships the main reason for installing gas turbines has been to allow a reduction of emissions in sensitive environmental areas or while in port. Some warships and a few modern cruise ships have also used the steam turbines to improve the efficiency of their gas turbines in a combined cycle, where wasted heat from a gas turbine exhaust is utilized to boil water and create steam for driving a steam turbine. In such combined cycles, thermal efficiency can be the same or slightly greater than that of diesel engines alone; however, the grade of fuel needed for these gas turbines is far more costly than that needed for the diesel engines, so the running costs are still higher.

Steering systems

On boats with simple propulsion systems, such as paddles, steering systems may not be necessary. In more advanced designs, such as boats propelled by engines or sails, a steering system becomes more necessary. The most common is a rudder, a submerged plane located at the rear of the hull. Rudders are rotated to generate a lateral force which turns the boat. Rudders can be rotated by a tiller, manual wheels, or electro-hydraulic systems. Autopilot systems combine mechanical rudders with navigation systems. Ducted propellers are sometimes used for steering.

Some propulsion systems are inherently steering systems. Examples include the outboard motor, the bow thruster, and the Z-drive. Some sails, such as jibs and the mizzen sail on a ketch rig, are used more for steering than propulsion.

Holds, compartments, and the superstructure