| Revision as of 20:03, 26 May 2015 editJytdog (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers187,951 edits remove undue weight from lead. no MEDRS sources for that← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:05, 26 May 2015 edit undoJytdog (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers187,951 edits →European Union: remove unsourced contentNext edit → | ||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

| === European Union === | === European Union === | ||

| In the ] (EU), HFCS, known as isoglucose in sugar regime, is subject to a ]. In 2005, this quota was set at 303,000 tons; in comparison, the EU produced an average of 18.6 million tons of sugar annually between 1999 and 2001.<ref>{{cite book|editor=M. Ataman Aksoy, John C. Beghin |title=Global Agricultural Trade and Developing Countries |year=2005 |publisher=World Bank Publications |isbn=0-8213-5863-4 |page=329 |chapter=Sugar Policies: An Opportunity for Change}}</ref> |

In the ] (EU), HFCS, known as isoglucose in sugar regime, is subject to a ]. In 2005, this quota was set at 303,000 tons; in comparison, the EU produced an average of 18.6 million tons of sugar annually between 1999 and 2001.<ref>{{cite book|editor=M. Ataman Aksoy, John C. Beghin |title=Global Agricultural Trade and Developing Countries |year=2005 |publisher=World Bank Publications |isbn=0-8213-5863-4 |page=329 |chapter=Sugar Policies: An Opportunity for Change}}</ref> | ||

| === Japan === | === Japan === | ||

Revision as of 20:05, 26 May 2015

"HFCS" redirects here. Not to be confused with HFCs.| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 1,176 kJ (281 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carbohydrates | 76 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 0 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fat | 0 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Protein | 0 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 24 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shown is for 100 g, roughly 5.25 tbsp. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults, except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

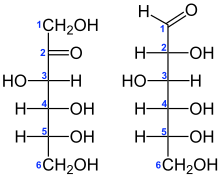

High fructose corn syrup (HFCS) (also called glucose-fructose and isoglucose) is made from corn starch that has been processed by glucose isomerase to convert some of its glucose into fructose. High fructose corn syrup was first brought to market in the early 1970s through the cooperative effort of a US company, the Clinton Corn Processing Company, and the Japanese research institute where the enzyme was discovered.

HFCS is used worldwide to sweeten foods and beverages since it is easier to handle than granulated sugar, and since price of the raw material, corn, has generally been more stable due to government subsidies and a wider worldwide base of production, than the sugar cane used for sugar production. Use of HCFS peaked in the late 1990s; demand decreased due to public concern about a possible link between HCFS and metabolic diseases like obesity and diabetes. The Corn Refiners Association has attempted to counter negative public perceptions by marketing campaigns describing HFCS as "natural" and by attempting to change the name of the product to "corn sugar," which the FDA rejected.

Uses and composition

HFCS is 24% water, the rest mainly fructose and glucose with 0–5% unprocessed glucose oligomers, HFCS 55 (≈55% fructose if water were removed) is mostly used in soft drinks; HFCS 42 is used in beverages, processed foods, cereals, and baked goods. HFCS-90 has some niche uses but mainly mixed with HFCS 42 to make HFCS 55.

Food

In the U.S., HFCS is among the sweeteners that mostly replaced sucrose (table sugar) in the food industry. Factors include production quotas of domestic sugar, import tariff on foreign sugar, and subsidies of U.S. corn, raising the price of sucrose and lowering that of HFCS, making it cheapest for many sweetener applications. The relative sweetness of HFCS 55, used most commonly is soft drinks, is comparable to sucrose.

Because of its superficially similar sugar profile and lower price, HFCS has been used illegally to "stretch" honey. Assays to detect adulteration with HFCA use differential scanning calorimetry and other advanced testing methods.

Beekeeping

In apiculture in the United States, HFCS became a sucrose replacement for honey bees starting in the late 1970s. When HFCS is heated to about 45 degrees C, hydroxymethylfurfural can form from the breakdown of fructose, and is toxic to bees. HCFS has been investigated as a possible source of colony collapse disorder.

Production

Corn syrups, including HFCS, are made from corn starch, which is turn refined from corn. The process of turning starches into sugars dates back to the nineteenth century; commercial production of corn syrup began in 1864. In the late 1950s scientists at Clinton Corn Processing Company in Iowa attempted to turn glucose from corn starch into fructose, but the process was not scalable. In the mid 1960s a scientist, Yoshiyuki Takasaki, at the Japanese National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) developed a heat-stable Xylose isomerase enyzme from yeast, and three years later AIST partnered with the Clinton company to commercialize the process.

In the contemporary process, corn (maize) is milled to produces corn starch and an "acid-enzyme" process is used in which the corn starch solution is acidified to begin breaking up the existing carbohydrates, and then enzymes are added to further metabolize the starch and convert the resulting sugars to fructose. The first enzyme added is alpha-amylase which turns breaks the long chains down into shorter sugar chains – oligosaccharides. Glucoamylase is mixed in and converts them to glucose; the resulting solution is filtered to remove protein, then using activated carbon, and then demineralized using Ion-exchange resins. The purified solution is then run over immobilized xylose isomerase, which turns the sugars to ~50–52% glucose with some unconverted oligosaccharides, and 42% fructose (HFCS 42), and again demineralized and again purified using activated carbon. Some is processed into HFCS 90 by liquid chromatography, then mixed with HFCS 42 to form HFCS 55. The enzymes used in the process are made by microbial fermentation.

Sweetener consumption patterns

Historical

Prior to the development of the worldwide sugar industry, dietary fructose was limited to only a few items. Milk, meats, and most vegetables, the staples of many early diets, have no fructose, and only 5–10% fructose by weight is found in fruits such as grapes, apples, and blueberries. Molasses and common dried fruits have a content of less than 10% fructose sugar. From 1970 to 2000 there was a 25% increase in "added sugars" in the U.S. After being classified as "generally recognized as safe" (GRAS) by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1976, HFCS began to replace sucrose as the main sweetener of soft drinks in the United States. At the same time, rates of obesity rose. That correlation, in combination with laboratory research and epidemiological studies that suggested a link between consuming large amounts of fructose and changes to various proxy health measures including elevated blood triglycerides, size and type of low-density lipoproteins, uric acid levels, and weight, raised concerns about health effects of HFCS itself.

United States

In the US, sugar tariffs and quotas keep imported sugar at up to twice the global price since 1797, while subsidies to corn growers cheapen the primary ingredient in HFCS, corn. Industrial users looking for cheaper replacements rapidly adopted HFCS in the 1970s.

HFCS is easier to handle than granulated sucrose, although some sucrose is transported as solution. Unlike sucrose, HFCS cannot be hydrolyzed, but the free fructose in HFCS may produce Hydroxymethylfurfural when stored at high temperatures; these differences are most prominent in acidic beverages. Soft drink makers such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi use sugar in other nations, but switched to HFCS in the U.S. in 1984. Large corporations, such as Archer Daniels Midland, lobby for the continuation of government corn subsidies.

Other countries, including Mexico, typically use sugar in soft drinks. Some Americans seek out Mexican Coca-Cola in ethnic groceries because they prefer the taste compared to Coca-Cola in the U.S. which is made with HFCS. Kosher for Passover Coca-Cola sold in the U.S. around the Jewish holiday also uses sucrose rather than HFCS and is also highly sought after by people who prefer the original taste.

Consumption of HFCS in the U.S. has declined since it peaked at 37.5 lb (17.0 kg) per person in 1999. The average American consumed approximately 27.1 lb (12.3 kg) of HFCS in 2012, versus 39.0 lb (17.7 kg) of refined cane and beet sugar.

European Union

In the European Union (EU), HFCS, known as isoglucose in sugar regime, is subject to a production quota. In 2005, this quota was set at 303,000 tons; in comparison, the EU produced an average of 18.6 million tons of sugar annually between 1999 and 2001.

Japan

In Japan, HFCS is manufactured mostly from imported US corn and the output is regulated by the government. For the period from 2007 to 2012 HFCS had a 27-30% share of the Japanese sweetener market.

Health

Health concerns have been raised about a relationship between HFCS and metabolic disorders, and with regard to manufacturing contaminants.

Obesity and metabolic disorders

Sugars became a health concern among the American public in the early 1970s with the publication of John Yudkin’s book, Pure, White and Deadly, which claimed that simple sugars, an increasingly large part of the Western diet, were dangerous. In the 1980s and 1990s Gerald Reaven and Sheldon Reiser of the USDA published papers discussing the dangers of dietary fructose from consumption of sucrose and of HFCS, especially with regard to heart disease, diabetes, and obesity. These concerns came to the public's attention through media attention to a 2004 commentary in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition that suggested that the altered metabolism of fructose when compared to glucose may be a factor in increasing obesity rates since, as compared to glucose, fructose may be more readily converted to fat and the sugar causes less of a rise in insulin and leptin, both of which increase feelings of satiety. Fructose, in contrast to glucose, was shown to potently stimulate lipogenesis (creation of fatty acids, for conversion to fat). In subsequent interviews, two of the study's authors stated the article was distorted to place emphasis solely on HFCS when the actual issue was the overconsumption of any type of sugar. While fructose absorption and modification by the intestines and liver does differ from glucose initially, the majority of the fructose molecules are converted to glucose or metabolized into byproducts identical to those produced by glucose metabolism. Consumption of moderate amounts of fructose has also been linked to positive outcomes, including reducing appetite if consumed before a meal, lower blood sugar increases compared to glucose, and (again compared to glucose) delaying exhaustion if consumed during exercise.

In 2007 an expert panel assembled by the University of Maryland's Center for Food, Nutrition and Agriculture Policy reviewed the links between HFCS and obesity and concluded there was no ecological validity in the association between rising body mass indexes (a measure of obesity) and the consumption of HFCS. The panel stated that since the ratio of fructose to glucose had not changed substantially in the United States since the 1960s when HFCS was introduced, the changes in obesity rates were probably not due to HFCS specifically but rather a greater consumption of calories overall, and recommended further research on the topic. In 2009 the American Medical Association published a review article on HFCS and concluded that based on the science available at the time it appeared unlikely that HFCS contributed more to obesity or other health conditions than sucrose, and there was insufficient evidence to suggest warning about or restricting use of HFCS or other fructose-containing sweeteners in foods. The review did report that studies found direct associations between high intakes of fructose and adverse health outcomes, including obesity and the metabolic syndrome.

In 2010, Consumer Reports noted that "HFCS has roughly the same composition as cane sugar—about half glucose and half fructose—and the same number of calories. Concerns that it's directly responsible for rising obesity rates or somehow intrinsically more fat-inducing than sugar are largely unfounded, though researchers continue to study whether the body handles HFCS differently."

Epidemiological research has suggested that the increase in metabolic disorders like obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, is linked to increased consumption of sugars and/or calories in general, and not due to any special effect of HFCS High fructose consumption has been linked to high levels of uric acid in the blood, though this is only thought to be a concern for patients with gout.

Numerous agencies in the United States recommend reducing the consumption of all sugars, including HFCS, without singling it out as presenting extra concerns. The Mayo Clinic cites the American Heart Association's recommendation that women limit the added sugar in their diet to 100 calories a day (~6 teaspoons) and that men limit it to 150 calories a day (~9 teaspoons), noting that there is not enough evidence to support HFCS having more adverse health effects than excess consumption of any other type of sugar. The United States departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services recommendations for a healthy diet state that consumption of all types of added sugars be reduced.

Manufacturing contaminants

HFCS contains reactive dicarbonyl compounds that are created during the processing steps, these compounds are comparable to the levels found in bread, instant coffee, and alcoholic beverages, and significantly lower than those found in toast, brewed coffee, soybean paste and sauce, and cheeses. These dicarbonyl compounds can in turn create advanced glycation end-products, the possible health effects of which were under investigation as of 2013.

In the contemporary process to make HFCS, an "acid-enzyme" process is used in which the corn starch solution is acidified to begin breaking up the existing carbohydrates, and then enzymes are added to further metabolize the starch and convert the resulting sugars to fructose. The chemical used to acidify the solution, lye was formerly manufactured using a process that included mercury, and scientists decided to investigate if HFCS used in food contained mercury. Two papers published in 2009 finding that there were traces of inorganic mercury in some foods. However, the mercury was not methylmercury, the form of mercury that is dangerous to human health.

Public relations

Main article: Public relations of high fructose corn syrupThere are various public relations issues with HFCS, including with its labeling as "natural", with its advertising, with companies that have moved back to sugar, and a proposed name change to "corn sugar". In 2010 the Corn Refiners Association applied to allow HFCS to be renamed "corn sugar", but were rejected by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 2012.

See also

Further reading

Litchfield, Ruth (2008). High Fructose Corn Syrup—How sweet it is. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

Alternative names

References

- United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). "Chapter 4: Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". In Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). pp. 120–121. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada: The Canadian Soft Drink Industry

- European Starch Association. "Factsheet on Glucose Fructose Syrups and Isoglucose".

- "Frequently Asked Questions: What is Glucose-Fructose Syrup?". European Food Information Council (EUFIC). Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21050460 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 21050460instead. - "Sugar and Sweeteners: Background". United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. November 14, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- John S. White (December 2, 2008). "HFCS: How sweet it is". Food Product Design. Retrieved September 6, 2009.

- (Bray, 2004 & U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Sugar and Sweetener Yearbook series, Tables 50–52)

- Pollan M (12 October 2003). "The (Agri)Cultural Contradictions Of Obesity". The New York Times.

- Engber, Daniel (2009-04-28). "The decline and fall of high-fructose corn syrup. – By Daniel Engber – Slate Magazine". Slate.com. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- Hanover LM, White JS (1993). "Manufacturing, composition, and applications of fructose". Am J Clin Nutr. 58 (suppl 5): 724S–732S. PMID 8213603.

- "Advances in Honey Adulteration Detection". Food Safety Magazine. 1974-08-12. Retrieved 2015-05-09.

- "Economically motivated adulteration (EMA) of food: common characteristics of EMA incidents". J Food Prot. 76 (4): 723–35. April 2013. doi:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-399. PMID 23575142.

Because the sugar profile of high-fructose corn syrup is similar to that of honey, high-fructose corn syrup was more difficult to detect until new tests were developed in the 1980s. Honey adulteration has continued to evolve to evade testing methodology, requiring continual updating of testing methods.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - "High fructose corn syrup: Production, uses and public health concerns" (PDF). Biotechnology and Molecular Biology Review. 5 (5): 71–78. December 2010. ISSN 1538-2273.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ White JS. Sucrose, HFCS, and Fructose: History, Manufacture, Composition, Applications, and Production. Chapter 2 in J.M. Rippe (ed.), Fructose, High Fructose Corn Syrup, Sucrose and Health, Nutrition and Health. Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014. ISBN 9781489980779.

- MARSHALL RO, KOOI ER (1957). "Enzymatic Conversion of d-Glucose to d-Fructose". Science. 125 (3249): 648–649. doi:10.1126/science.125.3249.648. PMID 13421660.

- ^ Larry Hobbs. Sweeteners from Starch: Production, Properties and Uses. Chapter 21 in Starch: Chemistry and Technology, Third Edition. Eds. James N. BeMiller, Roy L. Whistler. Elsevier Inc.: 2009. ISBN 9780127462752

- Leeper HA, Jones E (October 2007). "How bad is fructose?" (PDF). Am J Clin Nutr. 86 (4). American Society for Clinical Nutrition: 895–896. PMID 1792136.

- "Database of Select Committee on GRAS Substances (SCOGS) Reviews". Accessdata.fda.gov. 2006-10-31. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- Tyler James Wiltgen (August 2007). "An Economic History of the United States Sugar Program" (PDF). Masters thesis.

- "U.S. Sugar Policy". SugarCane.org. Retrieved 2015-02-11.

- "Food without Thought: How U.S. Farm Policy Contributes to Obesity". Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy. November 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.

- "Corn Production/Value". Allcountries.org. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- "Understanding High Fructose Corn Syrup". Beverage Institute.

- The Great Sugar Shaft by James Bovard, April 1998 The Future of Freedom Foundation

- James Bovard. "Archer Daniels Midland: A Case Study in Corporate Welfare". cato.org. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- Louise Chu,Associated Press (2004-11-09). "Is Mexican Coke the real thing?". The San Diego Union-Tribune.

- "Mexican Coke a hit in U.S." The Seattle Times.

- Dixon, Duffie (April 9, 2009). "Kosher Coke 'flying out of the store'". USA Today. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- "table51 – Refined cane and beet sugar: estimated number of per capita calories consumed daily, by calendar year". Economic Research Service. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- "table50 – U.S. per capita caloric sweeteners estimated deliveries for domestic food and beverage use, by calendar year". Economic Research Service. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- "U.S. Consumption of Caloric Sweeteners". Economic Research Service. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- M. Ataman Aksoy, John C. Beghin, ed. (2005). "Sugar Policies: An Opportunity for Change". Global Agricultural Trade and Developing Countries. World Bank Publications. p. 329. ISBN 0-8213-5863-4.

- International Sugar Organization March 2012 Alternative Sweeteners in a High Sugar Price Environment

- Samuel VT (February 2011). "Fructose induced lipogenesis: from sugar to fat to insulin resistance". Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 22 (2): 60–5. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2010.10.003. PMID 21067942.

- Bray, GA; Nielsen SJ; Popkin BM (2004). "Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 79 (4): 537–543. PMID 15051594.

- Parker-Pope, Tara (September 20, 2010). "In Worries About Sweeteners, Think of All Sugars". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-04-20.

- Warner, M (2006-07-02). "A Sweetener With a Bad Rap". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- Forshee RA; Storey, ML; et al. (2007). "A critical examination of the evidence relating high-fructose corn syrup and weight gain" (pdf). Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 47 (6): 561–82. doi:10.1080/10408390600846457. PMID 17653981.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last3=(help) - Moeller SM et al. The effects of high fructose syrup. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009 Dec;28(6):619-26. PMID 20516261

- Staff writers (March 2010). "The lowdown on high-fructose corn syrup". Consumer Reports.

- Stanhope, Kimber L.; Schwarz, Jean-Marc; Havel, Peter J. (June 2013). "Adverse metabolic effects of dietary fructose". Current Opinion in Lipidology. 24 (3): 198–206. doi:10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283613bca.

- Allocca, M; Selmi C (2010). "Emerging nutritional treatments for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". Nutrition, diet therapy, and the liver. CRC Press. pp. 131–146. ISBN 1-4200-8549-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - "High-fructose corn syrup: What are the health concerns?". Mayo Clinic. 2012-09-27. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th Edition (pdf). United States Department of Agriculture and United States Department of Health and Human Services. December 2010. Retrieved 2012-10-17.

- White, J.S. (2009). "Misconceptions about High-Fructose Corn Syrup: Is It Uniquely Responsible for Obesity, Reactive Dicarbonyl Compounds, and Advanced Glycation Endproducts?". J Nutr. 139 (6): 1219S–1227S. PMID 19386820.

- Poulsen MW et al Advanced glycation endproducts in food and their effects on health. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013 Oct;60:10-37.PMID 23867544

- By Miranda Hitti and Louise Chang for WebMD. January 27, 2009 Mercury in High-Fructose Corn Syrup?

- FDA rejects industry bid to change name of high fructose corn syrup to "corn sugar"

External links

- Sugar, The Bitter Truth

- Template:Dmoz

- Not only Sugar is Sweet, article in FDA Consumer published in 1991

| Maize and corn | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varieties | |||||||||||||||

| Parts | |||||||||||||||

| Processing | |||||||||||||||

| Pathology | |||||||||||||||

| Production | |||||||||||||||

| Culture |

| ||||||||||||||

| Maize dishes |

| ||||||||||||||