| Revision as of 19:14, 19 April 2023 view sourceCostcoantimationsS (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users963 edits →Artemis (2017–present)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:50, 1 January 2025 view source Citation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,418,721 edits Added work. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Jay8g | #UCB_toolbar | ||

| (246 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|American space and aeronautics agency}} | {{Short description|American space and aeronautics agency}} | ||

| {{Other uses}} | {{Other uses}} | ||

| {{pp-move |

{{pp-move}} | ||

| {{pp |

{{pp|small=yes}} | ||

| {{Use American English|date=July 2015}} | {{Use American English|date=July 2015}} | ||

| {{Use mdy dates|date= |

{{Use mdy dates|date=October 2023}} | ||

| {{Infobox space agency | {{Infobox space agency | ||

| | name = National Aeronautics and Space Administration | |||

| | seal = NASA seal.svg | |||

| |agency_type = ]<br />] | |||

| | seal_alt = A blue sphere with stars, a yellow planet with a white moon; a red chevron representing wings, and an orbiting spacecraft; surrounded by a white border with "NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION U.S.A." in red letters | |||

| |seal = ] | |||

| | seal_caption = ] | |||

| |seal_alt = A blue sphere with stars, a yellow planet with a white moon; a red chevron representing wings, and an orbiting spacecraft; surrounded by a white border with "NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION U.S.A." in red letters | |||

| | logo = ] ] | |||

| |seal_caption = NASA seal | |||

| | logo_alt = The "meatball" insignia, a blue sphere with stars, white letters of NASA, a red chevron representing wings, and a white orbiting spacecraft with a white trail showing its orbit path and the "worm" insignia, a red line forming stylized letters of NASA. | |||

| |logo = ] ] ] | |||

| | logo_caption = ] | |||

| |logo_alt = A blue sphere with stars, white letters N-A-S-A in Helvetica font; a red chevron representing wings, and a white orbiting spacecraft with a white trail showing its orbit path and, for "worm" insignia, a red line forming stylized letters N-A-S-A | |||

| | image = NASA HQ Building.jpg | |||

| |logo_caption = ] | |||

| | image_size = 250px | |||

| |image = NASA HQ Building.jpg | |||

| | image_caption = ] building in ] | |||

| | acronym = NASA | |||

| | formed = {{Start date and age|1958|07|29}} | |||

| | preceding1 = ] (1915–1958)<ref name="CentNACA">. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140220005256/http://www.centennialofflight.net/essay/Evolution_of_Technology/NACA/Tech1.htm |date=February 20, 2014}}. centennialofflight.net. Retrieved on November 3, 2011.</ref> | |||

| | agency_type = ]<br />] research agency | |||

| |jurisdiction = ] | |||

| | jurisdiction = ] | |||

| |headquarters = Washington, D.C. | |||

| | headquarters = ]<br>] | |||

| |coordinates = {{Coord|38|52|59|N|77|0|59|W|type:landmark_region:US-DC|display=inline}} | |||

| | coordinates = {{Coord|38|52|59|N|77|0|59|W|type:landmark_region:US-DC|display=inline}} | |||

| |motto = "Exploring the secrets of the universe for the benefit of all"<ref>{{cite web|title=Our Missions and Values|date=April 20, 2018 |url=https://www.nasa.gov/careers/our-mission-and-values|access-date=October 6, 2022|publisher=nasa.gov}}</ref> | |||

| | leader_title = ] | |||

| |employees = 17,960 (2022)<ref>{{cite web |url=https://wicn.nssc.nasa.gov/c10/cgi-bin/cognosisapi.dll?b_action=powerPlayService&m_encoding=UTF-8&BZ=1AAABgNNr_f942m2PQWuDQBCF%7E8yOaS9hdlTUgwd1DRHamEahZ6NjCTFuUFOaf981KYTSzu7wHm__gV2ryJdFme%7ESTIXjpAfO1BMQHSShS5TK2I89x%7ENXsYt24AfKd4Mg8mLHMM%7EWvJtGu2S9jcp1CLSqdT9xPxnX6q7hAdwYHOyrE4OtFttBt4eOgTC57HlcgKsMea7qY%7EXBv9F3PRxbPdQz%7ELM245YqkmWSbzZpUmZGotc0%7EAe14rewRRQSEaVEIQQKFwWhmI8QUdcZOD2dO31lHgGDvDeBukxXI0DtPP0yP2m4MfaFq082kADygWwDsATaAwX3QD4C8afk7c7m%7EqBbP_obQJNj2A%3D%3D |title=Workforce Profile |publisher=NASA |access-date=August 11, 2022 |archive-date=August 11, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220811051531/https://wicn.nssc.nasa.gov/c10/cgi-bin/cognosisapi.dll?b_action=powerPlayService&m_encoding=UTF-8&BZ=1AAABgNNr_f942m2PQWuDQBCF~8yOaS9hdlTUgwd1DRHamEahZ6NjCTFuUFOaf981KYTSzu7wHm__gV2ryJdFme~STIXjpAfO1BMQHSShS5TK2I89x~NXsYt24AfKd4Mg8mLHMM~WvJtGu2S9jcp1CLSqdT9xPxnX6q7hAdwYHOyrE4OtFttBt4eOgTC57HlcgKsMea7qY~XBv9F3PRxbPdQz~LM245YqkmWSbzZpUmZGotc0~Ae14rewRRQSEaVEIQQKFwWhmI8QUdcZOD2dO31lHgGDvDeBukxXI0DtPP0yP2m4MfaFq082kADygWwDsATaAwX3QD4C8afk7c7m~qBbP_obQJNj2A%3D%3D |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | leader_name = ] | |||

| |budget = {{increase}} {{US$|24.041 billion|link=yes}} (2022)<ref>{{Cite web |title=NASA's FY 2022 Budget |url=https://www.planetary.org/space-policy/nasas-fy-2022-budget |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210528194457/https://www.planetary.org/space-policy/nasas-fy-2022-budget |archive-date=28 May 2021 |access-date=June 28, 2022 |website=]}}</ref> | |||

| | leader_title2 = ] | |||

| | leader_name2 = ] | |||

| | spaceports = {{ubli | |||

| |leader_title2 = ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| |leader_name2 = ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| |website = {{official URL}} | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ] | |||

| |language = <!-- Please do not add English in this entry, English is NOT an official language of the US government. --> | |||

| }} | |||

| | employees = 17,960 (2022)<ref>{{Cite web |title=Workforce Profile |url=https://wicn.nssc.nasa.gov/c10/cgi-bin/cognosisapi.dll?b_action=powerPlayService&m_encoding=UTF-8&BZ=1AAABgNNr_f942m2PQWuDQBCF%7E8yOaS9hdlTUgwd1DRHamEahZ6NjCTFuUFOaf981KYTSzu7wHm__gV2ryJdFme%7ESTIXjpAfO1BMQHSShS5TK2I89x%7ENXsYt24AfKd4Mg8mLHMM%7EWvJtGu2S9jcp1CLSqdT9xPxnX6q7hAdwYHOyrE4OtFttBt4eOgTC57HlcgKsMea7qY%7EXBv9F3PRxbPdQz%7ELM245YqkmWSbzZpUmZGotc0%7EAe14rewRRQSEaVEIQQKFwWhmI8QUdcZOD2dO31lHgGDvDeBukxXI0DtPP0yP2m4MfaFq082kADygWwDsATaAwX3QD4C8afk7c7m%7EqBbP_obQJNj2A%3D%3D |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220811051531/https://wicn.nssc.nasa.gov/c10/cgi-bin/cognosisapi.dll?b_action=powerPlayService&m_encoding=UTF-8&BZ=1AAABgNNr_f942m2PQWuDQBCF~8yOaS9hdlTUgwd1DRHamEahZ6NjCTFuUFOaf981KYTSzu7wHm__gV2ryJdFme~STIXjpAfO1BMQHSShS5TK2I89x~NXsYt24AfKd4Mg8mLHMM~WvJtGu2S9jcp1CLSqdT9xPxnX6q7hAdwYHOyrE4OtFttBt4eOgTC57HlcgKsMea7qY~XBv9F3PRxbPdQz~LM245YqkmWSbzZpUmZGotc0~Ae14rewRRQSEaVEIQQKFwWhmI8QUdcZOD2dO31lHgGDvDeBukxXI0DtPP0yP2m4MfaFq082kADygWwDsATaAwX3QD4C8afk7c7m~qBbP_obQJNj2A%3D%3D |archive-date=August 11, 2022 |access-date=August 11, 2022 |publisher=NASA}}</ref> | |||

| | budget = {{increase}} {{US$|25.4 billion}} (2023)<ref>{{Cite web |title=NASA's FY 2023 Budget |url=https://www.planetary.org/space-policy/nasas-fy-2023-budget |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230324094555/https://www.planetary.org/space-policy/nasas-fy-2023-budget |archive-date=March 24, 2023 |access-date=July 27, 2023 |website=]}}</ref> | |||

| | website = {{url|https://www.nasa.gov/|nasa.gov}} | |||

| | language = <!-- Please do not add English in this entry, English is NOT an official language of the US government. --> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{United States space program sidebar}} | {{United States space program sidebar}} | ||

| The '''National Aeronautics and Space Administration''' ('''NASA''' {{IPAc-en|ˈ|n|æ|s|ə}}) is an ] of the ] responsible for the civil ], ] research |

The '''National Aeronautics and Space Administration''' ('''NASA''' {{IPAc-en|ˈ|n|æ|s|ə}}) is an ] of the ] responsible for the ]' civil ], ] research and ] research. ], it succeeded the ] (NACA) to give the US space development effort a distinct civilian orientation, emphasizing peaceful applications in ]. It has since led most of America's ] programs, including ], ], the 1968–1972 ] ] missions, the ] space station, and the ]. Currently, NASA supports the ] (ISS) along with the ], and oversees the development of the ] and the ] for the lunar ]. | ||

| NASA's science division is focused on better understanding Earth through the ]; advancing ] through the efforts of the ]'s Heliophysics Research Program; exploring bodies throughout the ] with advanced ] such as '']'' and ] such as '']''; and researching ] topics, such as the ], through the ], the four ], and associated programs. The ] oversees launch operations for its ]. | |||

| NASA was ], succeeding the ] (NACA), to give the U.S. space development effort a distinctly civilian orientation, emphasizing peaceful applications in ].<ref name="DDE">{{Cite web |url=http://www.eisenhowermemorial.org/#/news?nid=244 |title=Ike in History: Eisenhower Creates NASA |access-date=November 27, 2013 |publisher=Eisenhower Memorial |date=2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131119131818/http://www.eisenhowermemorial.org/#/news?nid=244 |archive-date=November 19, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="act1">{{cite web |url=https://www.nasa.gov/offices/ogc/about/space_act1.html |title=The National Aeronautics and Space Act |access-date=August 29, 2007 |publisher=NASA |date=2005 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070816121716/http://www.nasa.gov/offices/ogc/about/space_act1.html |archive-date=August 16, 2007 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="NacaNASA">{{cite book |last=Bilstein |first=Roger E. |title=NASA SP-4206, Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicles |chapter=From NACA to NASA |chapter-url=https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4206/ch2.htm#32 |date=1996 |publisher=NASA |isbn=978-0-16-004259-1 |pages=32–33 |access-date=May 6, 2013 |archive-date=July 14, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190714121412/https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4206/ch2.htm#32 |url-status=live }}</ref> NASA has since led most American ], including ], ], the 1968–1972 ] ] missions, the ] space station, and the ]. NASA supports the ] and oversees the development of the ] and the ] for the crewed lunar ], ] spacecraft, and the planned ] space station. The agency is also responsible for the ], which provides oversight of launch operations and countdown management for ]. | |||

| NASA's science is focused on better understanding Earth through the ];<ref>{{cite web |url=http://nasascience.nasa.gov/earth-science |title=Earth—NASA Science |first=Ruth |last=Netting |date=June 30, 2009 |access-date=July 15, 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090716013403/http://nasascience.nasa.gov/earth-science |archive-date=July 16, 2009}}</ref> advancing ] through the efforts of the ]'s Heliophysics Research Program;<ref>{{cite web |url=http://nasascience.nasa.gov/heliophysics |title=Heliophysics—NASA Science |first=Ruth |last=Netting |date=January 8, 2009 |access-date=July 15, 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090716023622/http://nasascience.nasa.gov/heliophysics |archive-date=July 16, 2009}}</ref> exploring bodies throughout the ] with advanced ] such as '']'' and ] such as '']'';<ref name="NYT-20150828">{{cite news|last=Roston|first=Michael|date=August 28, 2015|title=NASA's Next Horizon in Space|website=]|url=https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/08/25/science/space/nasa-next-mission.html|url-status=live|access-date=August 28, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150829045031/http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/08/25/science/space/nasa-next-mission.html|archive-date=August 29, 2015}}</ref> and researching ] topics, such as the ], through the ], and the ] and associated programs.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://nasascience.nasa.gov/astrophysics |title=Astrophysics—NASA Science |first=Ruth |last=Netting |date=July 13, 2009 |access-date=July 15, 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090716013614/http://nasascience.nasa.gov/astrophysics |archive-date=July 16, 2009}}</ref> | |||

| ==Management== | |||

| ===Leadership=== | |||

| ] (2021–present)]] | |||

| The agency's administration is located at ] in Washington, DC, and provides overall guidance and direction.<ref name="HQ">{{cite web |url=https://www.nasa.gov/centers/hq/home/index.html |title=Welcome to NASA Headquarters |first=Mary |last=Shouse |date=July 9, 2009 |access-date=July 15, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090713052817/http://www1.nasa.gov/centers/hq/home/index.html |archive-date=July 13, 2009 |url-status=live}}</ref> Except under exceptional circumstances, NASA civil service employees are required to be ].<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181007011245/https://nasajobs.nasa.gov/jobs/noncitizens.htm |date=October 7, 2018}}, NASA (downloaded September 16, 2013)</ref> | |||

| NASA's administrator is nominated by the President of the United States subject to the approval of the ],<ref>{{cite act |type=Title |index= |date=July 29, 1958 |article=II Sec. 202 (a) |article-type=Title |legislature=85th Congress of the United States |title=] |trans-title= |page= |url=https://en.wikisource.org/National_Aeronautics_and_Space_Act_of_1958 |access-date=September 11, 2020 |archive-date=September 17, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200917214738/https://en.wikisource.org/National_Aeronautics_and_Space_Act_of_1958 |url-status=live }} {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200917214738/https://en.wikisource.org/National_Aeronautics_and_Space_Act_of_1958 |date=September 17, 2020 }}</ref> and serves at the President's pleasure as a senior space science advisor. The current administrator is ], appointed by President ], since May 3, 2021.<ref>{{cite news |last=Bartels |first=Meghan |title=President Biden nominates Bill Nelson to serve as NASA chief |url=https://www.space.com/biden-nasa-chief-bill-nelson-nomination |work=space.com |date= March 19, 2021 |access-date= September 6, 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ===Strategic plan=== | |||

| NASA operates with four FY2022 strategic goals.<ref name="nasa.stratpln">{{cite web |title=NASA FY2022 Strategic Plan |url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/fy_22_strategic_plan.pdf |access-date=2 Sep 2022}}</ref> | |||

| * Expand human knowledge through new scientific discoveries | |||

| * Extend human presence to the Moon and on towards Mars for sustainable long-term exploration, development, and utilization | |||

| * Catalyze economic growth and drive innovation to address national challenges | |||

| * Enhance capabilities and operations to catalyze current and future mission success | |||

| ===Budget=== | |||

| {{Further|Budget of NASA}} | |||

| NASA budget requests are developed by NASA and approved by the administration prior to submission to the ]. Authorized budgets are those that have been included in enacted appropriations bills that are approved by both houses of Congress and enacted into law by the U.S. president.<ref>{{cite web|title=Budget of the U.S. Government |url=https://www.usa.gov/budget|work=us.gov |access-date=September 6, 2022 }}</ref> | |||

| NASA fiscal year budget requests and authorized budgets are provided below. | |||

| {| class="wikitable float-left" style="text-align: center;" | |||

| !Year | |||

| !Budget Request <br />in bil. US$ | |||

| !Authorized Budget <br />in bil. US$ | |||

| !U.S. Government<br>Employees | |||

| |- | |||

| |2018 | |||

| |$19.092<ref name="nasa.bdgt2018">{{cite web |title=NASA FY2018 Budget Estimates |url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/fy19_nasa_budget_estimates.pdf |access-date=2 Sep 2022}}</ref> | |||

| |$20.736<ref name="nasa.bdgt2019"/> | |||

| |17,551<ref name="nasa.eeop2018">{{cite web |title=NASA Equal Employment Opportunity Strategic Plan: FY 2018-19|url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/2018_nasa_md_715_report_5-15-2019_tagged.pdf|access-date=2 Sep 2022}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |2019 | |||

| |$19.892<ref name="nasa.bdgt2019">{{cite web |title=NASA FY2019 Budget Estimates |url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/fy19_nasa_budget_estimates.pdf |access-date=2 Sep 2022}}</ref> | |||

| |$21.500<ref name="nasa.bdgt2020"/> | |||

| |17,551<ref name="nasa.eeop2019">{{cite web |title=NASA Model Equal Employment Opportunity Program Status Report: FY2019|url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/a2020-00087-signed-05-08-2020-tagged.pdf|access-date=2 Sep 2022}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |2020 | |||

| |$22.613<ref name="nasa.bdgt2020">{{cite web |title=NASA FY2020 Budget Estimates |url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/fy_2020_congressional_justification.pdf |access-date=2 Sep 2022}}</ref> | |||

| |$22.629<ref name="nasa.bdgt2021"/> | |||

| |18,048<ref name="nasa.eeop2020">{{cite web |title=NASA Model Equal Employment Opportunity Program Status Report: FY2020|url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/fy2020_md_715_report_signed_tagged.pdf|access-date=2 Sep 2022}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |2021 | |||

| |$25.246<ref name="nasa.bdgt2021">{{cite web |title=NASA FY2021 Budget Estimates |url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/fy_2021_budget_book_508.pdf |access-date=2 Sep 2022}}</ref> | |||

| |$23.271<ref name="nasa.bdgt2022"/> | |||

| |18,339<ref name="nasa.eeop2021">{{cite web |title=NASA Model Equal Employment Opportunity Program Status Report: FY2021|url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/odeo-fy21_model_715_report_tagged.pdf|access-date=September 2, 2022}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |2022 | |||

| |$24.802<ref name="nasa.bdgt2022">{{cite web |title=NASA FY2022 Budget Estimates |url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/fy2022_congressional_justification_nasa_budget_request.pdf |access-date=2 Sep 2022}}</ref> | |||

| |$24.041<ref>{{cite web |last=Smith |first=Marcia |title=NASA to get $24 billion for FY2022, more than last year but less than Biden Wanted |url=https://spacepolicyonline.com/news/nasa-to-get-24-billion-for-fy2022-more-than-last-year-but-less-than-biden-wanted/ |date=March 9, 2022 |access-date=September 6, 2022 |work=SpacePolicyOnline.com }}</ref> | |||

| |18,400 est | |||

| |} | |||

| ===Organization=== | |||

| NASA funding and priorities are developed through its six Mission Directorates. | |||

| {| class="wikitable float-left" style="text-align: left" style="width: 500px;" | |||

| !Mission Directorate | |||

| !Associate Administrator | |||

| !% of NASA Budget (FY22)<ref name="nasa.bdgt2022"/> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |Robert A. Pearce<ref>{{cite web |title=NASA Administrator Names Robert Pearce Head of Agency Aeronautics | |||

| |url=https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/nasa-administrator-names-robert-pearce-head-of-agency-aeronautics-300972658.html|work=NASA |date=December 10, 2019 |access-date=September 6, 2022 |via=prnewswire}}</ref> | |||

| |{{center|4%}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Exploration Systems Development (ESDMD) | |||

| |James Free<ref name=nasa20210921>{{cite news |title= NASA Splits Human Spaceflight Directorate into Two | |||

| |url=https://spacepolicyonline.com/news/nasa-splits-human-spaceflight-directorate-into-two/ | |||

| |last=Smith |first=Marcia | |||

| |date=September 21, 2021 |access-date=September 6, 2022|work=Space Policy Online}}</ref> | |||

| |{{center|28%}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Space Operations (SOMD) | |||

| |]<ref name=nasa20210921/> | |||

| |{{center|17%}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |Dr. ]<ref>{{Cite news |last=Roulette |first=Joey |date=2023-02-27 |title=NASA names solar physicist as agency's science chief |language=en |work=Reuters |url=https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/science/nasa-name-first-woman-agencys-science-chief-sources-say-2023-02-27/ |access-date=2023-04-07}}</ref> | |||

| |{{center|32%}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Space Technology (STMD) | |||

| |James L. Reuter<ref>{{cite news |title=James Reuter, Associate Administrator, STMD, NASA HQ |url=https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/spacetech/about_us/bios/reuter_bio2/ |date=November 29, 2021|access-date=September 7, 2022 |work=nasa.gov}}</ref> | |||

| |{{center|5%}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |Mission Support (MSD) | |||

| |Robert Gibbs<ref>{{cite news |title=NASA executive discusses his approach to leadership | |||

| |url=https://federalnewsnetwork.com/leaders-and-legends/2022/06/nasa-executive-discusses-his-approach-to-leadership/ |date=June 21, 2022|access-date=September 7, 2022 |work=Federal News Network}}</ref> | |||

| |{{center|14%}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |} | |||

| Center-wide activities such as the Chief Engineer and Safety and Mission Assurance organizations are aligned to the headquarters function. The MSD budget estimate includes funds for these HQ functions. The administration operates 10 major field centers with several managing additional subordinate facilities across the country. Each is led by a Center Director (data below valid as of September 1, 2022). | |||

| {| class="wikitable float-left" style="text-align: left;" | |||

| !Field Center | |||

| !Primary Location | |||

| !Center Director | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |Dr. Eugene L. Tu<ref>{{cite news |last= Clemens |first=Jay |title=Eugene Tu Named Director of NASA Ames Research Center; Charles Bolden Comments |url=https://executivegov.com/2015/05/eugene-tu-named-director-of-nasa-ames-research-center-charles-bolden-comments/ |date=May 5, 2015 |access-date=September 6, 2022 |work=ExecutiveGov}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |Brad Flick (acting)<ref>{{cite web |title=NASA Announces Armstrong Flight Research Center Director to Retire | |||

| |url=https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-announces-armstrong-flight-research-center-director-to-retire |date=May 23, 2022 |access-date=September 6, 2022|work=NASA.gov}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |], Ohio | |||

| |Dr. James A. Kenyon (acting)<ref>{{cite news |last=Suttle |first=Scott |title=NASA names two interim leaders for Glenn Research Center |url=https://www.crainscleveland.com/government/nasa-names-two-interim-leaders-glenn-research-center | |||

| |date=May 22, 2022 |access-date=September 6, 2022|work=Crain's Cleveland Business}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |Dr. Makenzie Lystrup<ref>{{cite press release| last=Bardan | first=Roxana | title=NASA Administrator Names New Goddard Center Director | website=NASA | date=April 6, 2023 | url=http://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-administrator-names-new-goddard-center-director | access-date=April 6, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |Laurie Leshin<ref>{{cite news |title=WPI president to step down to become director of JPL |url=https://apnews.com/article/business-education-worcester-67f3316391e12747d149cec3129596f9 |date=January 29, 2022 |access-date=September 6, 2022|work=ap news}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |], Texas | |||

| |Vanessa E. Wyche<ref>{{cite news |last=Hagerty |first=Michael |title=Vanessa Wyche Takes The Helm At NASA's Johnson Space Center | |||

| |url=https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/shows/houston-matters/2021/08/26/406823/vanessa-wyche-takes-the-helm-at-nasas-johnson-space-center-aug-26-2021/|work=Houston Public Media |date=August 26, 2021 |access-date=September 6, 2022}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |Janet Petro<ref>{{cite news |title=First Woman to Lead NASA's Kennedy Space Center Is a BU Alum |url=https://www.bu.edu/articles/2021/janet-petro-nasa-kennedy-space-center-director/ |date=July 16, 2021 |access-date=September 6, 2022|work=Bostonia}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |Clayton Turner<ref>{{cite news |last=Dietrich |first=Tamara |title=NASA Langley gets a new director | |||

| |url=https://www.dailypress.com/news/dp-nw-nasa-langley-new-director-20190909-itmxmy74anafjnpnm56g3mh4wm-story.html|date=September 9, 2019 |access-date=September 6, 2022 | |||

| |work=Daily Press}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |Jody Singer<ref>{{cite news |last=Beck |first=Caroline |title=Jody Singer appointed first female director of Marshall Space Flight Center | |||

| |url=https://www.aldailynews.com/jody-singer-appointed-first-female-director-of-marshall-space-flight-center/ |work=Alabama Daily News|date=September 14, 2018|access-date=September 6, 2022}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |Richard J. Gilbrech<ref>{{cite news |title=Stennis Space Center Announces New Senior Executive Service Appointment |url=https://www.bizneworleans.com/stennis-space-center-announces-new-senior-executive-service-appointment/ |date=August 26, 2021 |access-date=September 6, 2022 |work=Biz New Orleans}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |} | |||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| === |

=== Creation === | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|Creation of NASA|National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics}} | ||

| ] test flight]] | |||

| <section begin=CONASA/> | |||

| ] | |||

| Beginning in 1946, the ] (NACA) began experimenting with ]s such as the supersonic ].<ref name="NACASupersonic">{{cite web |url=https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20100025896_2010028361.pdf |title=The NACA, NASA, and the Supersonic-Hypersonic Frontier |access-date=September 30, 2011 |publisher=NASA |archive-date=June 18, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200618015305/https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20100025896.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> In the early 1950s, there was challenge to launch an artificial satellite for the ] (1957–1958). An effort for this was the American ]. After the ]'s launch of the world's first artificial ] ('']'') on October 4, 1957, the attention of the United States turned toward its own fledgling space efforts. The ], alarmed by the perceived threat to national security and technological leadership (known as the "]"), urged immediate and swift action; President ] counseled more deliberate measures. The result was a consensus that the White House forged among key interest groups, including scientists committed to basic research; the Pentagon which had to match the Soviet military achievement; corporate America looking for new business; and a strong new trend in public opinion looking up to space exploration.<ref>Roger D. Launius, "Eisenhower, Sputnik, and the Creation of NASA." ''Prologue-Quarterly of the National Archives'' 28.2 (1996): 127–143.</ref> | |||

| On January 12, 1958, NACA organized a "Special Committee on Space Technology", headed by ].<ref name="NacaNASA" /> On January 14, 1958, NACA Director ] published "A National Research Program for Space Technology", stating,<ref name="Erickson">{{Cite book |title=Into the Unknown Together—The DOD, NASA, and Early Spaceflight |last=Erickson |first=Mark |isbn=978-1-58566-140-4 |url=http://aupress.au.af.mil/Books/Erickson/erickson.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090920093817/http://aupress.au.af.mil/Books/Erickson/erickson.pdf |archive-date=September 20, 2009|year=2005}}</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|It is of great urgency and importance to our country both from consideration of our prestige as a nation as well as military necessity that this challenge ]''] be met by an energetic program of research and development for the conquest of space ... It is accordingly proposed that the scientific research be the responsibility of a national civilian agency ... NACA is capable, by rapid extension and expansion of its effort, of providing leadership in ].<ref name="Erickson" />}} | |||

| While this new federal agency would conduct all non-military space activity, the ] (ARPA) was created in February 1958 to develop space technology for military application.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N-IPAAAAIAAJ |title=Supplemental military construction authorization (Air Force).: Hearings, Eighty-fifth Congress, second session, on H.R. 9739. |date= January 21–24, 1958 |last1=Subcommittee On Military Construction |first1=United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Armed Services |access-date=June 27, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150905184757/https://books.google.com/books/about/Fiscal_year_1958_supplemental_military_c.html?id=N-IPAAAAIAAJ |archive-date=September 5, 2015 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| On July 29, 1958, Eisenhower signed the ], establishing NASA.<ref>{{cite news |title=U.S. makes ready to launch program for outer space conquest |url=https://www.upi.com/Archives/1958/07/29/US-makes-ready-to-launch-program-for-outer-space-conquest/5841501125157/ |date= July 29, 1958 |access-date=September 7, 2022 |work=upi}}</ref> When it began operations on October 1, 1958, NASA absorbed the 43-year-old NACA intact; its 8,000 employees, an annual budget of US$100 million, three major research laboratories (], ], and ]) and two small test facilities.<ref name="Glennan">{{cite web |url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/Biographies/glennan.html |title=T. Keith Glennan |publisher=NASA |date=August 4, 2006 |access-date=July 15, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170214234112/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/Biographies/glennan.html |archive-date=February 14, 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> Elements of the ] and the ] were incorporated into NASA. A significant contributor to NASA's entry into the ] with the Soviet Union was the technology from the ] led by ], who was now working for the ] (ABMA), which in turn incorporated the technology of American scientist ]'s earlier works.<ref name="recoll">{{cite web |url=https://history.msfc.nasa.gov/vonbraun/recollect-childhood.html |first=Werner |last=von Braun |date=1963 |title=Recollections of Childhood: Early Experiences in Rocketry as Told by Werner Von Braun 1963 |website=MSFC History Office |publisher=NASA Marshall Space Flight Center |access-date=July 15, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090709045105/http://history.msfc.nasa.gov/vonbraun/recollect-childhood.html |archive-date=July 9, 2009 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Earlier research efforts within the ]<ref name="Glennan" /> and many of ARPA's early space programs were also transferred to NASA.<ref name="DARPA">{{Cite web |url=http://www.arpa.mil/Docs/Intro_-_Van_Atta_200807180920581.pdf |title=50 years of Bridging the Gap |first=Richard |last=Van Atta |date=April 10, 2008 |access-date=July 15, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090224210533/http://www.arpa.mil/Docs/Intro_-_Van_Atta_200807180920581.pdf |archive-date=February 24, 2009 |url-status=dead}}</ref> In December 1958, NASA gained control of the ], a contractor facility operated by the ].<ref name="Glennan" /><section end=CONASA/> | |||

| === Past administrators === | |||

| {{Further|Administrator of NASA}} | |||

| NASA's first administrator was Dr. ] who was appointed by President ]. During his term (1958–1961) he brought together the disparate projects in American space development research.<ref name="glennan_biography">{{cite web |url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/Biographies/glennan.html |title=T. Keith Glennan biography |publisher=NASA |date=August 4, 2006 |access-date=July 5, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170214234112/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/Biographies/glennan.html |archive-date=February 14, 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> ] led the agency during the development of the Apollo program in the 1960s.<ref>{{cite news|last=Williams|first=Christian|title=James Webb and NASA's Reach For The Moon|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1981/09/24/james-webb-and-nasas-reach-for-the-moon/253a284e-bdd9-480f-ae0b-19a96ca7d961/|date=September 24, 1981|access-date=October 4, 2022|newspaper=Washington Post}}</ref> ] has held the position twice; first during the Nixon administration in the 1970s and then at the request of Ronald Reagan following the ].<ref name="fletcher">{{cite web |url=http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/Biographies/fletcher.html |title=James C. Fletcher biography |publisher=NASA |access-date=July 5, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080706164016/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/Biographies/fletcher.html |archive-date= July 6, 2008 |url-status=live}}</ref> ] held the post for nearly 10 years and is the longest serving administrator to date. He is best known for pioneering the "faster, better, cheaper" approach to space programs.<ref name="goldin_biography">{{cite web |url=http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/dan_goldin.html |title=Daniel S. Goldin biography |publisher=NASA |date=March 12, 2004 |access-date= July 5, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080615143450/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/dan_goldin.html |archive-date=June 15, 2008|url-status=live}}</ref> Bill Nelson is currently serving as the 14th administrator of NASA. | |||

| === Insignia === | |||

| {{Further|NASA insignia}} | |||

| The ] was approved by Eisenhower in 1959, and slightly modified by President ] in 1961.<ref name="order">]</ref><ref>]</ref> NASA's first logo was designed by the head of Lewis' Research Reports Division, James Modarelli, as a simplification of the 1959 seal.<ref name="nasameatball">{{cite web|last1=Garber|first1=Steve|title=NASA "Meatball" Logo|url=https://history.nasa.gov/meatball.htm|website=NASA History Program Office|publisher=NASA|access-date=October 15, 2015|archive-date=November 12, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201112010815/https://history.nasa.gov/meatball.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> In 1975, the original logo was first dubbed "the meatball" to distinguish it from the newly designed "worm" logo which replaced it. The "meatball" returned to official use in 1992.<ref name="nasameatball" /> The "worm" was brought out of retirement by administrator ] in 2020.<ref name="NYT-20200408">{{cite news |last=Chang |first=Kenneth |title=NASA's 'Worm' Logo Will Return to Space – The new old logo, dropped in the 1990s in favor of a more vintage brand, will adorn a SpaceX rocket that is to carry astronauts to the space station in May. |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/science/nasa-logo-worm-spacex.html |date=April 8, 2020 |work=] |access-date=April 8, 2020 |archive-date=October 27, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201027203512/https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/science/nasa-logo-worm-spacex.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Facilities === | |||

| {{Further|NASA facilities}} | |||

| ] in Washington, DC provides overall guidance and political leadership to the agency's ten field centers, through which all other facilities are administered.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/files/NASAFacilitiesAndCenters.pdf |title=NASA Facilities and Centers |publisher=NASA |access-date=July 30, 2020 |archive-date=October 25, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201025025648/https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/files/NASAFacilitiesAndCenters.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| | total_width = 320 | |||

| | image1 = Aerial View Ames Research Center Wind Tunnels - GPN-2000-001761.jpg | |||

| | image2 = Edw-081013-03-dryden-12.jpg | |||

| | footer = Aerial views of the NASA Ames (left) and NASA Armstrong (right) centers | |||

| }} | |||

| ] (ARC) at ] is located in the Silicon Valley of central California and delivers wind-tunnel research on the aerodynamics of propeller-driven aircraft along with research and technology in aeronautics, spaceflight, and information technology.<ref>{{cite news |last=Tillman |first=Nola |title=Ames Research Center: R&D Lab for NASA |url=https://www.space.com/39381-ames-research-center.html |date= January 12, 2018 |access-date=September 7, 2022 |work=space.com}}</ref> It provides leadership in ], small satellites, robotic lunar exploration, intelligent/adaptive systems and thermal protection. | |||

| ] (AFRC) is located inside ] and is the home of the ] (SCA), a modified Boeing 747 designed to carry a ] back to ] after a landing at Edwards AFB. The center focuses on flight testing of advanced aerospace systems. | |||

| ] is based in Cleveland, Ohio and focuses on air-breathing and in-space propulsion and cryogenics, communications, power energy storage and conversion, microgravity sciences, and advanced materials.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nasa.gov/centers/glenn/about/history/timeline.html |title=NASA Glenn's Historical Timeline |date=April 16, 2015 |publisher=NASA |access-date=September 4, 2022 }}</ref> | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| | total_width = 320 | |||

| | image1 = NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Aerial view 2010 facing south.jpg | |||

| | image2 = Mission_control_center.jpg | |||

| | footer = View of ] campus (left) and ] at JSC (right) | |||

| }} | |||

| ] (GSFC), located in ] develops and operates uncrewed scientific spacecraft.<ref name=space.gsfc/> GSFC also operates two spaceflight tracking and data acquisition networks (the ] and the ]), develops and maintains advanced space and Earth science data information systems, and develops satellite systems for the ] (NOAA).<ref name=space.gsfc>{{cite news |last=Fentress |first=Steve |title=NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center: Exploring Earth and space by remote control |url=https://www.space.com/goddard-space-flight-center.html |date=February 10, 2020 |access-date=September 8, 2022 |work=space.com}}</ref> | |||

| ] (JSC) is the NASA center for human spaceflight training, research and flight control.<ref>{{cite news |title=6 decades of space and Houston: JSC celebrates anniversary with big bash |url=https://www.khou.com/article/tech/science/space/houston-we-have-an-anniversary-60-years-of-the-johnson-space-center/285-fc467c14-69f8-4242-aa80-21b9f06cd93b |date=April 28, 2022 |access-date=September 8, 2022 |work=KHOU Channel 11}}</ref> It is home to the ] and is responsible for training astronauts from the US and its international partners, and includes the ].<ref name=ar5>{{cite web |url=http://www.sti.nasa.gov/tto/spinoff1997/ar5.html |title=Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center |author=NASA |access-date=August 27, 2008 |archive-date=September 8, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120908190120/http://spinoff.nasa.gov/spinoff1997/ar5.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> JSC also operates the ] in Las Cruces, New Mexico to support rocket testing. | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| | total_width = 320 | |||

| | image1 = Site du JPL en Californie.jpg | |||

| | image2 = Langley research center.jpg | |||

| | footer = View of ] (left) and the Langley Research Center (right) | |||

| }} | |||

| ] (JPL), located in the ] area of Los Angeles County, C and builds and operates robotic planetary spacecraft, though it also conducts Earth-orbit and astronomy missions.<ref>{{cite news |last=Voosen |first=Paul |title=New director of NASA's storied Jet Propulsion Lab takes on ballooning mission costs |url=https://www.science.org/content/article/new-director-nasa-s-storied-jet-propulsion-lab-takes-ballooning-mission-costs |date=June 3, 2022 |access-date=September 7, 2022|work=science.com}}</ref> It is also responsible for operating NASA's ]. | |||

| ] (LaRC), located in ], Virginia devotes two-thirds of its programs to ], and the rest to ]. LaRC researchers use more than 40 ]s to study improved aircraft and ] safety, performance, and efficiency. The center was also home to early human spaceflight efforts including the team chronicled in the ] story.<ref>{{cite news |date=January 5, 2017|access-date=September 8, 2022 |last=Rothman |first=Lily |title=What to Know About the Real Research Lab From Hidden Figures |url=https://time.com/4602996/hidden-figures-langley/ |work=time.com}}</ref> | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| | total_width = 320 | |||

| | image1 = VAB_and_SLS.jpg | |||

| | image2 = Msfc aerial view.jpg | |||

| | alt2 = Aerial view of Kennedy Space Center showing VAB and Launch Complex 39 | |||

| | footer = View of the SLS exiting the ] at KSC (left) and of the ] test stands (right) | |||

| }} | |||

| ] (KSC), located west of ] in Florida, has been the launch site for every United States human space flight since 1968. KSC also manages and operates uncrewed rocket launch facilities for America's civil space program from three pads at Cape Canaveral.<ref name="KSC Story">{{cite web|title=Kennedy Space Center Story|url=http://www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/about/history/story/kscstory.html|publisher=NASA|access-date=November 5, 2015|date=1991|archive-date=May 20, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170520011616/https://www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/about/history/story/kscstory.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] (MSFC), located on the ] near Huntsville, Alabama, is one of NASA's largest centers and is leading the development of the ] in support of the ] program. Marshall is NASA's lead center for ] (ISS) design and assembly; payloads and related crew training; and was the lead for ] propulsion and its external tank.<ref>{{cite web |last=Fentress |first=Steve |title=NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center: A hub for historic and modern-day rocket power |url=https://www.space.com/marshall-space-flight-center.html |date=July 6, 2021 |access-date=September 8, 2022 |work=space.com}}</ref> | |||

| ], originally the "Mississippi Test Facility", is located in ], on the banks of the ] at the ]–] border.<ref>{{cite news |last=Glorioso |first=Mark |title=The path to the moon runs through Mississippi | |||

| |url=https://www.hattiesburgamerican.com/story/opinion/2020/10/19/stennis-space-center-opportunities-mississippi-opinion/3678720001/ |date=October 19, 2020 |access-date=September 8, 2022 |work=Hattiesburg American }}</ref> Commissioned in October 1961, it is currently used for rocket testing by over 30 local, state, national, international, private, and public companies and agencies.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://wgno.com/news/viral/stennis-space-center-tests-rocket-engines-that-will-be-used-in-nasas-historic-artemis-i-mission-to-the-moon/ |title=Stennis Space Center tests rocket engines that will be used in NASA's historic Artemis I mission to the moon |last=Lopez |first=Kenny |publisher=WGNO TV |date=August 9, 2022 |access-date=September 4, 2022 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.meridianstar.com/news/state/stennis-space-center-set-for-active-testing-year/article_07dc7545-c79b-525c-9ed9-2b9c98cc55ae.html |title=Stennis Space Center set for active testing year |author=<!--not stated--> |publisher=Meridian Star |date=January 22, 2022 |access-date=September 4, 2022 }}</ref> It also contains the NASA Shared Services Center.<ref name="NSSC">{{cite web|url=http://www.nssc.nasa.gov/main/background.htm|title=NASA Shared Services Center Background|first=Rebecca|last=Dubuisson|date=July 19, 2007|access-date=July 15, 2009|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090716045126/https://www.nssc.nasa.gov/main/background.htm|archive-date=July 16, 2009}}</ref> | |||

| === Past human spaceflight programs === | |||

| ==== X-15 (1954<!-- RfP of the program initiated in 1954, see below -->–1968) ==== | |||

| {{Further|North American X-15}} | |||

| ] | |||

| NASA inherited NACA's X-15 experimental rocket-powered ] research aircraft, developed in conjunction with the US Air Force and ]. Three planes were built starting in 1955. The X-15 was ] from the wing of one of two NASA ]es, ''NB52A'' tail number 52-003, and ''NB52B'', tail number 52-008 (known as the '']''). Release took place at an altitude of about {{convert|45000|ft|km|sp=us}} and a speed of about {{convert|805|km/h|mph|sp=us|order=flip}}.<ref name="E-4942">{{cite web |url=http://www.dfrc.nasa.gov/Gallery/Photo/X-15/HTML/E-4942.html |title=X-15 launch from B-52 mothership |publisher=Armstrong Flight Research Center |date=February 6, 2002 |id=Photo E-4942 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |archive-date=May 27, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210527122519/https://www.dfrc.nasa.gov/Gallery/Photo/X-15/HTML/E-4942.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Twelve pilots were selected for the program from the Air Force, Navy, and NACA. A total of 199 flights were made between June 1959 and December 1968, resulting in the ] for the highest speed ever reached by a crewed powered aircraft (current {{As of|2013|alt=as of 2014}}), and a maximum speed of Mach 6.72, {{convert|4519|mph|km/h|sp=us}}.<ref name="Fastest"> {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110921174821/http://www.aerospaceweb.org/aircraft/research/x15/ |date=September 21, 2011}} ''Aerospaceweb.org'', November 24, 2008.</ref> The altitude record for X-15 was 354,200 feet (107.96 km).<ref name="NASAHyper" /> Eight of the pilots were awarded Air Force ] for flying above {{convert|80|km|ft|sp=us|order=flip}}, and two flights by ] exceeded {{convert|100|km|ft|sp=us}}, qualifying as spaceflight according to the ]. The X-15 program employed mechanical techniques used in the later crewed spaceflight programs, including ] jets for controlling the orientation of a spacecraft, ]s, and horizon definition for navigation.<ref name="NASAHyper"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181007011246/https://www.nasa.gov/centers/dryden/news/FactSheets/FS-052-DFRC.html |date=October 7, 2018}}, retrieved October 17, 2011</ref> The ] and landing data collected were valuable to NASA for designing the ].<ref name="AerospacewebX15"> {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110921174821/http://www.aerospaceweb.org/aircraft/research/x15/ |date=September 21, 2011}}. Aerospaceweb.org. Retrieved on November 3, 2011.</ref> | |||

| ==== Mercury (1958–1963) ==== | |||

| {{Further|Project Mercury}} | |||

| {{Image frame|align=left|content=]|border=no}} | |||

| ], photographed by a ] camera aboard '']'' (May 16, 1963)]] | |||

| In 1958, NASA formed an engineering group, the ], to manage their ] programs under the direction of ]. Their earliest programs were conducted under the pressure of the ] competition between the US and the Soviet Union. NASA inherited the US Air Force's ] program, which considered many crewed spacecraft designs ranging from rocket planes like the X-15, to small ballistic ]s.<ref name="Project1969"> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111011131311/http://astronautix.com/craft/prot7969.htm |date=October 11, 2011}}, retrieved October 17, 2011</ref> By 1958, the space plane concepts were eliminated in favor of the ballistic capsule,<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130603211738/http://www-pao.ksc.nasa.gov/history/mercury/mercury-overview.htm |date=June 3, 2013}}, retrieved October 17, 2011</ref> and NASA renamed it ]. The ] were selected among candidates from the Navy, Air Force and Marine test pilot programs. On May 5, 1961, astronaut ] became the first American in space aboard a capsule he named '']'', launched on a ] on a 15-minute ] (suborbital) flight.<ref name="ShepardsRide">{{Cite book |url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4201/toc.htm |title=This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury |format=url |chapter=11-4 Shepard's Ride |chapter-url=https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4201/ch11-4.htm |publisher=NASA |website=Published as NASA Special Publication-4201 in the NASA History Series |first1=Loyd S. |last1=Swenson Jr. |first2=James M. |last2=Grimwood |first3=Charles C. |last3=Alexander |editor1-first=David |editor1-last=Woods |editor2-first=Chris |editor2-last=Gamble |access-date=July 14, 2009 |date=1989 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090713233748/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4201/toc.htm |archive-date=July 13, 2009 |url-status=live}}</ref> ] became the first American to be launched into ], on an ] on February 20, 1962, aboard ].<ref name="AnAmericaninOrbit">{{Cite book |url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4201/toc.htm |title=This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury |format=url |chapter=13-4 An American in Orbit |chapter-url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4201/ch13-4.htm |publisher=NASA |website=Published as NASA Special Publication-4201 in the NASA History Series |first1=Loyd S. |last1=Swenson Jr. |first2=James M. |last2=Grimwood |first3=Charles C. |last3=Alexander |editor1-first=David |editor1-last=Woods |editor2-first=Chris |editor2-last=Gamble |access-date=July 14, 2009 |date=1989 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090713233748/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4201/toc.htm |archive-date=July 13, 2009 |url-status=live}}</ref> Glenn completed three orbits, after which three more orbital flights were made, culminating in ]'s 22-orbit flight '']'', May 15–16, 1963.<ref name="NASAManned">{{cite web |publisher=NASA |url=https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/mercury/missions/manned_flights.html |title=Mercury Manned Flights Summary |access-date=October 9, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110916001228/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/mercury/missions/manned_flights.html |archive-date=September 16, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> ], ], and ] were three of the ] doing calculations on trajectories during the Space Race.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|url=http://www.nasa.gov/content/katherine-johnson-biography|title=Katherine Johnson Biography|last=Loff|first=Sarah|date=November 22, 2016|website=NASA|access-date=March 8, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190331103455/https://www.nasa.gov/content/katherine-johnson-biography/|archive-date=March 31, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.nasa.gov/content/mary-jackson-biography|title=Mary Jackson Biography|last=Loff|first=Sarah|date=November 22, 2016|website=NASA|access-date=March 8, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190120155710/https://www.nasa.gov/content/mary-jackson-biography|archive-date=January 20, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.nasa.gov/content/dorothy-vaughan-biography|title=Dorothy Vaughan Biography|last=Loff|first=Sarah|date=November 22, 2016|website=NASA|access-date=March 8, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181130144413/https://www.nasa.gov/content/dorothy-vaughan-biography/|archive-date=November 30, 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> Johnson was well known for doing trajectory calculations for John Glenn's mission in 1962, where she was running the same equations by hand that were being run on the computer.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| NASA traces its roots to the ] (NACA). Despite being the birthplace of aviation, by 1914 the United States recognized that it was far behind Europe in aviation capability. Determined to regain American leadership in aviation, the ] created the ] of the US Army Signal Corps in 1914 and established NACA in 1915 to foster aeronautical research and development. Over the next forty years, NACA would conduct aeronautical research in support of the ], ], ], and the civil aviation sector. After the end of ], NACA became interested in the possibilities of guided missiles and supersonic aircraft, developing and testing the ] in a joint program with the ]. NACA's interest in space grew out of its rocketry program at the Pilotless Aircraft Research Division.<ref name="auto">{{Cite web |title=Naca to Nasa to Now – The frontiers of air and space in the American century |url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/naca_to_nasa_to_now_tagged.pdf |access-date=June 8, 2023 |archive-date=May 5, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230505075936/https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/naca_to_nasa_to_now_tagged.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Mercury's competition from the ] (USSR) was the single-pilot ] spacecraft. They sent the first man in space, cosmonaut ], into a single Earth orbit aboard ] in April 1961, one month before Shepard's flight.<ref name="NASAGagarin">{{cite web |publisher=NASA |url=https://www.nasa.gov/topics/history/features/gagarin/gagarin.html |title=NASA history, Gagarin |access-date=October 9, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111025035327/http://www.nasa.gov/topics/history/features/gagarin/gagarin.html |archive-date=October 25, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> In August 1962, they achieved an almost four-day record flight with ] aboard ], and also conducted a concurrent ] mission carrying ].<ref>{{cite web|title=Joint flight of Vostok-3 and Vostok-4|url=http://www.russianspaceweb.com/vostok3.html|date=December 1, 2020|access-date=October 1, 2022|publisher=russianspaceweb.com}}</ref> | |||

| ]'s ], America's first satellite]] | |||

| ==== Gemini (1961–1966) ==== | |||

| The Soviet Union's launch of ] ushered in the ] and kicked off the ]. Despite NACA's early rocketry program, the responsibility for launching the first American satellite fell to the ]'s ], whose operational issues ensured the ] would launch ], America's first satellite, on February 1, 1958. | |||

| {{Further|Project Gemini}} | |||

| {{Image frame|align=left|content=]|border=no}} | |||

| The ] decided to split the United States' military and civil spaceflight programs, which were organized together under the ]'s ]. NASA was established on July 29, 1958, with the signing of the ] and it began operations on October 1, 1958.<ref name="auto" /> | |||

| ] performs a ] to attach a tether to the ] on ], 1966.]] | |||

| Based on studies to grow the Mercury spacecraft capabilities to long-duration flights, developing ] techniques, and precision Earth landing, Project Gemini was started as a two-man program in 1961 to overcome the Soviets' lead and to support the planned Apollo crewed lunar landing program, adding ] (EVA) and ] and ] to its objectives. The first crewed Gemini flight, ], was flown by ] and ] on March 23, 1965.<ref name="TheLastHurdle">{{cite book |author=Barton C. Hacker |author2=James M. Grimwood |title=On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini |url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4203/toc.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100113132344/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4203/toc.htm |archive-date=January 13, 2010 |url-status=live |format=url |access-date=July 14, 2009 |date=December 31, 2002 |publisher=NASA |isbn=978-0-16-067157-9 |chapter=10-1 The Last Hurdle |chapter-url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4203/ch10-1.htm}}</ref> Nine missions followed in 1965 and 1966, demonstrating an endurance mission of nearly fourteen days, rendezvous, docking, and practical EVA, and gathering medical data on the effects of weightlessness on humans.<ref name="PlansforGemini3">{{cite book |author=Barton C. Hacker |author2=James M. Grimwood |title=On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini |url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4203/toc.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100113132344/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4203/toc.htm |archive-date=January 13, 2010 |url-status=live |access-date=July 14, 2009 |date=December 31, 2002 |publisher=NASA |isbn=978-0-16-067157-9 |chapter=12-5 Two Weeks in a Spacecraft |chapter-url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4203/ch12-5.htm}}</ref><ref name="AnAlternativeTarget">{{cite book |author=Barton C. Hacker |author2=James M. Grimwood |title=On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini |url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4203/toc.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100113132344/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4203/toc.htm |archive-date=January 13, 2010 |url-status=live |access-date=July 14, 2009 |date=December 31, 2002 |publisher=NASA |isbn=978-0-16-067157-9 |chapter=13-3 An Alternative Target |chapter-url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4203/ch13-3.htm}}</ref> | |||

| As the US's premier aeronautics agency, NACA formed the core of NASA's new structure by reassigning 8,000 employees and three major research laboratories. NASA also proceeded to absorb the Naval Research Laboratory's Project Vanguard, the Army's ] (JPL), and the ] under ]. This left NASA firmly as the United States' civil space lead and the Air Force as the military space lead.<ref name="auto" /> | |||

| Under the direction of ] ], the USSR competed with Gemini by converting their Vostok spacecraft into a two- or three-man ]. They succeeded in launching two crewed flights before Gemini's first flight, achieving a three-cosmonaut flight in 1964 and the first EVA in 1965.<ref>{{cite web|last=Mann|first=Adam|title=Voskhod program: The Soviet Union's first crewed space program | |||

| |url=https://www.space.com/voskhod-program.html|date=October 1, 2020|access-date=October 2, 2022|publisher=space.com}}</ref> After this, the program was canceled, and Gemini caught up while spacecraft designer ] developed the ], their answer to Apollo. | |||

| === First orbital and hypersonic flights === | |||

| ==== Apollo (1960–1972) ==== | |||

| {{ |

{{Main|Project Mercury}} | ||

| ]'', NASA's first orbital flight, February 20, 1962]] | |||

| {{Image frame|align=left|content=]|border=no}} | |||

| Plans for human spaceflight began in the US Armed Forces prior to NASA's creation. The Air Force's ] project formed in 1956,<ref>{{Cite web |last=Avilla |first=Aeryn |date=2021-06-02 |title=Wild Blue Yonder: USAF's Man In Space Soonest |url=https://www.spaceflighthistories.com/post/man-in-space-soonest |access-date=2024-05-02 |website=SpaceflightHistories |language=en}}</ref> coupled with the Army's Project Adam, served as the foundation for ]. NASA established the ] to manage the program,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Grimwood |first=James M. |date=February 13, 2006 |title=Project Mercury – A Chronology |url=https://spacemedicineassociation.org/videos/Project%20Mercury-A%20Chronology-NASA%20SP-4001.pdf |journal=NASA Office of Scientific and Technical Information |pages=44, 45}}</ref> which would conduct crewed sub-orbital flights with the Army's ] rockets and orbital flights with the Air Force's ] launch vehicles. While NASA intended for its first astronauts to be civilians, President Eisenhower directed that they be selected from the military. The ] astronauts included three Air Force pilots, three Navy aviators, and one Marine Corps pilot.<ref name="auto" /> | |||

| ] on the Moon, 1969 (photograph by ])]] | |||

| The U.S. public's perception of the Soviet lead in the Space Race (by putting the first man into space) motivated President ]<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Decision to Go to the Moon: President John F. Kennedy's May 25, 1961 Speech before Congress|url=https://history.nasa.gov/moondec.html|access-date=June 3, 2020|website=history.nasa.gov|archive-date=May 23, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200523060729/https://history.nasa.gov/moondec.html|url-status=live}}</ref> to ask the Congress on May 25, 1961, to commit the federal government to a program to land a man on the Moon by the end of the 1960s, which effectively launched the ].<ref>{{YouTube|TUXuV7XbZvU|John F. Kennedy "Landing a man on the Moon" Address to Congress}}, speech</ref> | |||

| ] hypersonic aircraft]] | |||

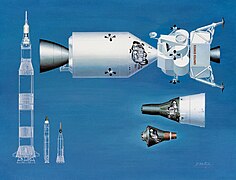

| Apollo was one of the most expensive American scientific programs ever. It cost more than $20 billion in 1960s dollars<ref name="Butts">{{cite web |last1=Butts |first1=Glenn |last2=Linton |first2=Kent |title=The Joint Confidence Level Paradox: A History of Denial, 2009 NASA Cost Symposium |date=April 28, 2009 |pages=25–26 |url=https://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/nexgen/Nexgen_Downloads/Butts_NASA's_Joint_Cost-Schedule_Paradox_-_A_History_of_Denial.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111026132859/http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/nexgen/Nexgen_Downloads/Butts_NASA%27s_Joint_Cost-Schedule_Paradox_-_A_History_of_Denial.pdf |archive-date=October 26, 2011 |access-date=December 23, 2021 }}</ref> or an estimated ${{Formatprice|{{Inflation|US|170000000000|2005|r=2}}}} in present-day US dollars.{{Inflation-fn|US}} (In comparison, the ] cost roughly ${{Formatprice|{{Inflation|US|2000000000|1945|r=2}}}}, accounting for inflation.){{Inflation-fn|US}}<ref name="harv">{{cite book |last=Nichols |first=Kenneth David |author-link=Kenneth Nichols |title=The Road to Trinity: A Personal Account of How America's Nuclear Policies Were Made, pp 34–35 |location=New York |publisher=William Morrow and Company |date=1987 |isbn=978-0-688-06910-0 |oclc=15223648 }}</ref> The Apollo program used the newly developed ] and ] rockets, which were far larger than the repurposed ICBMs of the previous Mercury and Gemini programs.<ref name="AstroSat5">{{cite web |title=Saturn V |url=http://www.astronautix.com/lvs/saturnv.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111007153222/http://astronautix.com/lvs/saturnv.htm |archive-date=October 7, 2011 |access-date=October 13, 2011 |publisher=Encyclopedia Astronautica}}</ref> They were used to launch the Apollo spacecraft, consisting of the ] (CSM) and the ] (LM). The CSM ferried astronauts from Earth to Moon orbit and back, while the Lunar Module would land them on the Moon itself.{{refn|group=note|The descent stage of the LM stayed on the Moon after landing, while the ascent stage brought the two astronauts back to the CSM and then was discarded in lunar orbit.}} | |||

| On May 5, 1961, ] became the first American to enter space, performing a suborbital spaceflight in the ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Gabriel |first=Angeli |date=2023-05-04 |title=On this day in 1961: First American astronaut goes to space |url=https://www.foxweather.com/earth-space/on-this-day-alan-shepard-first-american-space |access-date=2024-05-02 |website=Fox Weather |language=en-US}}</ref> This flight occurred less than a month after the Soviet ] became the first human in space, executing a full orbital spaceflight. NASA's first orbital spaceflight was conducted by ] on February 20, 1962, in the ], making three full orbits before reentering. Glenn had to fly parts of his final two orbits manually due to an autopilot malfunction.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Richard |first=Witkin |date=February 21, 1962 |title=Glenn Orbits Earth 3 Times Safely |url=https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/library/national/science/nasa/022162sci-nasa-witkin.html |access-date=2024-05-02 |website=archive.nytimes.com}}</ref> The sixth and final Mercury mission was flown by ] in May 1963, performing 22 orbits over 34 hours in the ].<ref>{{Cite web |author1=Elizabeth Howell |date=2014-02-01 |title=Gordon Cooper: Record-Setting Astronaut in Mercury & Gemini Programs |url=https://www.space.com/24520-gordon-cooper.html |access-date=2024-05-02 |website=Space.com |language=en}}</ref> The Mercury Program was wildly recognized as a resounding success, achieving its objectives to orbit a human in space, develop tracking and control systems, and identify other issues associated with human spaceflight.<ref name="auto" /> | |||

| While much of NASA's attention turned to space, it did not put aside its aeronautics mission. Early aeronautics research attempted to build upon the X-1's ] to build an aircraft capable of ]. The ] was a joint NASA–US Air Force program,<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-05-13 |title=North American X-15 {{!}} National Air and Space Museum |url=https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/north-american-x-15/nasm_A19690360000 |access-date=2024-05-02 |website=airandspace.si.edu |language=en}}</ref> with the hypersonic test aircraft becoming the first non-dedicated spacecraft to cross from the atmosphere to outer space. The X-15 also served as a testbed for Apollo program technologies, as well as ] and ] propulsion.<ref name="auto" /> | |||

| The planned first crew of 3 astronauts were killed due to a fire during a 1967 preflight test for the Apollo 204 mission (later renamed ]).<ref>{{cite web |title=Apollo 1 |url=https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/apollo/missions/apollo1.html |website=NASA |date=March 16, 2015 |access-date=16 May 2022 |archive-date=February 3, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170203185822/https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/apollo/missions/apollo1.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The second crewed mission, ], brought astronauts for the first time in a flight around the Moon in December 1968.<ref name="NASAApol8">{{cite web |url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4205/ch11-6.html |title=Apollo 8: The First Lunar Voyage |publisher=NASA |access-date=October 13, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111027194659/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4205/ch11-6.html |archive-date=October 27, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> Shortly before, the Soviets had sent an uncrewed spacecraft around the Moon.<ref name="Siddiqi">{{cite book |last=Siddiqi |first=Asif A. |title=The Soviet Space Race with Apollo |pages=654–656 |date=2003 |publisher=Gainesville: University Press of Florida |isbn=978-0-8130-2628-2}}</ref> The next two missions (] and ]) practiced rendezvous and docking maneuvers required to conduct the Moon landing.<ref name="NasaApollo9">{{cite web |url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4205/ch12-5.html |title=Apollo 9: Earth Orbital trials |publisher=NASA |access-date=October 13, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111027200206/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4205/ch12-5.html |archive-date=October 27, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="NASAApollo10">{{cite web |url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4205/ch12-7.html |title=Apollo 10: The Dress Rehearsal |publisher=NASA |access-date=October 13, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111027193342/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4205/ch12-7.html |archive-date=October 27, 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| === Moon landing === | |||

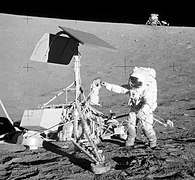

| The ] mission, launched in July 1969, landed the first humans on the Moon. Astronauts ] and ] walked on the lunar surface, conducting ] and ], while ] orbited above in the CSM.<ref name="NasaApollo11">{{cite web |title=The First Landing |url=https://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4205/ch14-4.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111027234250/http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4205/ch14-4.html |archive-date=October 27, 2011 |access-date=October 13, 2011 |publisher=NASA}}</ref> Six subsequent Apollo missions (12 through 17) were launched; five of them were successful, while one (]) was aborted after an in-flight emergency nearly killed the astronauts. Throughout these seven Apollo spaceflights, twelve men walked on the Moon. These missions returned a wealth of scientific data and {{convert|381.7|kg|lb}} of lunar samples. Topics covered by experiments performed included ], ]s, ], ], ], ]s, and ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Arriclucea|first=Eva|title=Case Study Report: Apollo Project (US)|url=https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/mission_oriented_r_and_i_policies_case_study_report_apollo_project-us.pdf|isbn=978-92-79-80155-6 | |||

| {{Main|Project Gemini|Apollo program}} | |||

| |doi=10.2777/568253|page=10|date=January 2018|access-date=October 2, 2022|publisher=European Commission}}</ref> The Moon landing marked the end of the space race; and as a gesture, Armstrong mentioned mankind when he stepped down on the Moon.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110924171813/http://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/324100.html |date=September 24, 2011}}'' ... a giant leap for mankind'', retrieved October 1, 2011</ref> | |||

| ] and ] conduct an orbital rendezvous]] | |||

| Escalations in the ] between the United States and Soviet Union prompted President ] to charge NASA with landing an American on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth by the end of the 1960s and installed ] as NASA administrator to achieve this goal.<ref>{{Cite web |title=James E. Webb |url=https://www.nmspacemuseum.org/inductee/james-e-webb/ |access-date=2024-05-05 |website=New Mexico Museum of Space History |language=en-US}}</ref> On May{{nbsp}}25, 1961, President Kennedy openly declared this goal in his "Urgent National Needs" speech to the United States Congress, declaring: | |||

| On July 3, 1969, the Soviets suffered a major setback on their Moon program when the rocket known as the ] had exploded in a fireball at its launch site at ] in Kazakhstan, destroying one of two launch pads. Each of the first four launches of N-1 resulted in failure before the end of the first stage flight effectively denying the Soviet Union the capacity to deliver the systems required for a crewed lunar landing.<ref>{{cite web|first=Asif|last=Siddiqi|title=Why the Soviets Lost the Moon Race|url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/apollo-why-the-soviets-lost-180972229/|date=June 2019|access-date=October 2, 2022|publisher=Smithsonian Magazine}}</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|I believe this Nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.}} | |||

| Kennedy gave his "]" speech the next year, on September{{nbsp}}12, 1962 at ], where he addressed the nation hoping to reinforce public support for the Apollo program.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Ketterer |first=Samantha |title=JFK's moon speech at Rice Stadium was 60 years ago. Has the U.S. lived up to it? |url=https://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/houston-texas/space/article/JFK-Rice-moon-speech-anniversary-space-exploration-17430937.php |access-date=2024-05-05 |work=Houston Chronicle |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Despite attacks on the goal of landing astronauts on the Moon from the former president Dwight Eisenhower and 1964 presidential candidate ], President Kennedy was able to protect NASA's growing budget, of which 50% went directly to human spaceflight and it was later estimated that, at its height, 5% of Americans worked on some aspect of the Apollo program.<ref name="auto" /> | |||

| Apollo set major ] in human spaceflight. It stands alone in sending crewed missions beyond ], and landing humans on another ].<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110220232013/https://history.nasa.gov/ap11ann/missions.htm |date=February 20, 2011}}. NASA, 1999.</ref> ] was the first crewed spacecraft to orbit another celestial body, while ] marked the last moonwalk and the last crewed mission beyond ]. The program spurred advances in many areas of technology peripheral to rocketry and crewed spaceflight, including ], telecommunications, and computers. Apollo sparked interest in many fields of engineering and left many physical facilities and machines developed for the program as landmarks. Many objects and artifacts from the program are on display at various locations throughout the world, notably at the ]. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ==== Skylab (1965–1979) ==== | |||

| Mirroring the Department of Defense's program management concept using redundant systems in building the first intercontinental ballistic missiles, NASA requested the Air Force assign Major General ] to the space agency where he would serve as the director of the Apollo program. Development of the ] rocket was led by Wernher von Braun and his team at the ], derived from the Army Ballistic Missile Agency's original ]. The ] was designed and built by ], while the ] was designed and built by ].<ref name="auto" /> | |||

| {{Further|Skylab}} | |||

| {{Image frame|align=left |total_width=120|content=]|border=no}} | |||

| To develop the spaceflight skills and equipment required for a lunar mission, NASA initiated ].<ref>{{Cite web |author1=Karl Tate |date=2015-06-03 |title=How NASA's Gemini Spacecraft Worked (Infographic) |url=https://www.space.com/29549-how-nasa-gemini-spacecraft-worked-infographic.html |access-date=2024-05-05 |website=Space.com |language=en}}</ref> Using a modified Air Force ] launch vehicle, the Gemini capsule could hold two astronauts for flights of over two weeks. Gemini pioneered the use of ] instead of batteries, and conducted the first American ] and ]. | |||

| ] in 1974, seen from the departing ] CSM]] | |||

| Skylab was the United States' first and only independently built ].<ref name="skylabFirst">{{Cite book |url=https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19770020211_1977020211.pdf |title=Skylab Our First Space Station—NASA report |id=NASA-SP-400 |date=1977 |publisher=NASA |editor-first=Leland F. |editor-last=Belew |access-date=July 15, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100317234819/http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19770020211_1977020211.pdf |archive-date=March 17, 2010 |url-status=live}}</ref> Conceived in 1965 as a workshop to be constructed in space from a spent ] upper stage, the {{convert|169950|lb|kg|0|abbr=on}} station was constructed on Earth and launched on May 14, 1973, atop the first two stages of a ], into a {{convert|235|nmi|km|adj=on}} orbit inclined at 50° to the equator. Damaged during launch by the loss of its thermal protection and one electricity-generating solar panel, it was repaired to functionality by its first crew. It was occupied for a total of 171 days by 3 successive crews in 1973 and 1974.<ref name="skylabFirst" /> It included a laboratory for studying the effects of ], and a ].<ref name="skylabFirst" /> NASA planned to have the in-development ] dock with it, and elevate Skylab to a higher safe altitude, but the Shuttle was not ready for flight before Skylab's re-entry and demise on July 11, 1979.<ref name="livingandworking">Benson, Charles Dunlap and William David Compton. '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151105142105/http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4208/contents.htm |date=November 5, 2015}}''. NASA publication SP-4208.</ref> | |||

| ] salutes the United States flag on the ].]] | |||

| To reduce cost, NASA modified one of the Saturn V rockets originally earmarked for a canceled Apollo mission to launch Skylab, which itself was a modified ]. Apollo spacecraft, launched on smaller ] rockets, were used for transporting astronauts to and from the station. Three crews, consisting of three men each, stayed aboard the station for periods of 28, 59, and 84 days. Skylab's habitable volume was {{convert|11290|ft3|m3|sp=us}}, which was 30.7 times bigger than that of the ].<ref name="livingandworking" /> | |||

| The ] was started in the 1950s as a response to Soviet lunar exploration, however most missions ended in failure. The ] had greater success, mapping the surface in preparation for Apollo landings and measured ], conducted meteoroid detection, and measured radiation levels. The ] conducted uncrewed lunar landings and takeoffs, as well as taking surface and regolith observations.<ref name="auto" /> Despite the setback caused by the ] fire, which killed three astronauts, the program proceeded. | |||

| ] was the first crewed ] to leave ] and the first ] to reach the ]. The crew orbited the Moon ten times on December{{nbsp}}24 and{{nbsp}}25, 1968, and then traveled safely back to ].<ref name="NYT-20181221">{{Cite news |last=Overbye |first=Dennis |author-link=Dennis Overbye |date=December 21, 2018 |title=Apollo 8's Earthrise: The Shot Seen Round the World – Half a century ago today, a photograph from the moon helped humans rediscover Earth. |work=] |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/21/science/earthrise-moon-apollo-nasa.html |url-access=limited |access-date=December 24, 2018 |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220101/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/21/science/earthrise-moon-apollo-nasa.html |archive-date=January 1, 2022}}{{cbignore}}</ref><ref name="NYT-20181224a">{{Cite news |last1=Boulton |first1=Matthew Myer |last2=Heithaus |first2=Joseph |date=December 24, 2018 |title=We Are All Riders on the Same Planet – Seen from space 50 years ago, Earth appeared as a gift to preserve and cherish. What happened? |work=] |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/24/opinion/earth-space-christmas-eve-apollo-8.html |url-access=limited |access-date=December 25, 2018 |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220101/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/24/opinion/earth-space-christmas-eve-apollo-8.html |archive-date=January 1, 2022}}{{cbignore}}</ref><ref name="NYT-20181224b">{{Cite news |last=Widmer |first=Ted |date=December 24, 2018 |title=What Did Plato Think the Earth Looked Like? – For millenniums, humans have tried to imagine the world in space. Fifty years ago, we finally saw it. |work=] |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/24/opinion/plato-earth-christmas-eve-apollo-8.html |url-access=limited |access-date=December 25, 2018 |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220101/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/24/opinion/plato-earth-christmas-eve-apollo-8.html |archive-date=January 1, 2022}}{{cbignore}}</ref> The three Apollo{{nbsp}}8 astronauts—], ], and ]—were the first humans to see the Earth as a globe in space, the first to witness an ], and the first to see and manually photograph the far side of the Moon. | |||

| ==== Space Transportation System (1969–1972) ==== | |||

| {{Further|Space Transportation System}} | |||

| In February 1969, President ] appointed a space task group headed by Vice President ] to recommend human spaceflight projects beyond Apollo. The group responded in September with the Integrated Program Plan (IPP), intended to support ]s in Earth and lunar orbit, a lunar surface base, and a human Mars landing. These would be supported by replacing NASA's existing ]s with a reusable infrastructure including Earth orbit shuttles, ]s, and a ] trans-lunar and interplanetary shuttle. Despite the enthusiastic support of Agnew and NASA Administrator ], Nixon realized public enthusiasm, which translated into Congressional support, for the space program was waning as Apollo neared its climax, and vetoed most of these plans, except for the ], and a deferred Earth space station.<ref>{{cite web|title=50 Years Ago: After Apollo, What? Space Task Group Report to President Nixon|url=https://www.nasa.gov/feature/50-years-ago-after-apollo-what-space-task-group-report-to-president-nixon|date=September 18, 2019|access-date=October 1, 2022|publisher=nasa.gov}}</ref> | |||

| The first lunar landing was conducted by Apollo{{nbsp}}11. Commanded by ] with astronauts ] and ], Apollo{{nbsp}}11 was one of the most significant missions in NASA's history, marking the end of the ] when the ] gave up its lunar ambitions. As the first human to step on the surface of the Moon, Neil Armstrong uttered the now famous words: | |||

| ==== Apollo–Soyuz (1972–1975) ==== | |||

| {{Further|Apollo–Soyuz}} | |||