| Revision as of 16:26, 20 October 2023 edit130.255.157.199 (talk) →Middle Assyrian Period and Empire← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:12, 24 December 2024 edit undo2001:a62:15af:e802:3522:6505:6b68:f988 (talk) →Chronology and periodizationTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| (37 intermediate revisions by 26 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {{Multiple issues| | {{Multiple issues| | ||

| {{Lead too short|date=May 2020}} | {{Lead too short|date=May 2020}} | ||

| {{More footnotes|date=May 2020}} | {{More footnotes needed|date=May 2020}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The ''' |

The '''Civilization of Mesopotamia''' ranges from the earliest human occupation in the ] period up to ]. This history is pieced together from evidence retrieved from archaeological excavations and, after the introduction of writing in the late 4th millennium BC, an increasing amount of historical sources. While in the ] and ] periods only parts of ] were occupied, the southern alluvium was settled during the late Neolithic period. Mesopotamia has been home to many of the oldest major civilizations, entering history from the ], for which reason it is often called a ]. | ||

| ==Short outline of Mesopotamia== | ==Short outline of Mesopotamia== | ||

| {{Main|Mesopotamia|Geography of Mesopotamia}} | {{Main|Mesopotamia|Geography of Mesopotamia}} | ||

| ], circa 7500 BC, with main archaeological sites of the ] period. At that time, the area of Mesopotamia proper was not yet settled by humans.]] | ], circa 7500 BC, with main archaeological sites of the ] period. At that time, the area of Mesopotamia proper was not yet settled by humans.]] | ||

| Mesopotamia ({{ |

Mesopotamia ({{langx|grc|Μεσοποταμία|Mesopotamíā}}; {{langx|syc|ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ||Bēṯ Nahrēn}}) means "Between the Rivers". The oldest known occurrence of the name Mesopotamia dates to the 4th century BC, when it was used to designate the area between the ] and the ]. The name was presumably translated from a term already current in the area—probably in Aramaic—and apparently was understood to mean the land lying "between the (Euphrates and Tigris) rivers", now ].<ref name="finkelstein">{{harvnb|Finkelstein|1962|p=73}}</ref> | ||

| Later and in the broader sense, the historical region included not only the area of present-day |

Later and in the broader sense, the historical region included not only the area of present-day Iraq, but also parts of present-day ], ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=history of Mesopotamia {{!}} Definition, Civilization, Summary, Agriculture, & Facts {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Mesopotamia-historical-region-Asia |access-date=2022-04-30 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last= |first= |last2= |last3= |first3= |last4= |last5= |last6= |last7= |last8= |first8= |last9= |date=1990-09-02 |title=How Mesopotamia Became Iraq (and Why It Matters) |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-09-02-bk-1977-story.html |access-date=2022-04-30 |website=Los Angeles Times |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Wood |first=Michael |date=2010-11-10 |title=The Ancient World {{!}} Mesopotamia |url=http://www.theguardian.com/culture/2010/nov/10/ancient-world-mesopotamia |access-date=2022-04-30 |website=the Guardian |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Seymour |first=Michael |date=2004 |title=Ancient Mesopotamia and Modern Iraq in the British Press, 1980–2003 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/383004 |journal=Current Anthropology |volume=45 |issue=3 |pages=351–368 |doi=10.1086/383004 |jstor=10.1086/383004 |s2cid=224788984 |issn=0011-3204}}</ref>{{sfn|Miquel|Brice|Sourdel|Aubin|2011}}<ref name="fosterpolingerfoster20096">{{harvnb|Foster|Polinger Foster|2009|p=6}}</ref> The neighbouring steppes to the west of the Euphrates and the western part of the ] are also often included under the wider term Mesopotamia.<ref name="canard">{{harvnb|Canard|2011}}</ref><ref name="wilkinson2000">{{harvnb|Wilkinson|2000|pp=222–223}}</ref><ref name="matthews20035">{{harvnb|Matthews|2003|p=5}}</ref> A further distinction is usually made between Upper or Northern Mesopotamia and Lower or Southern Mesopotamia.<ref name="miqueletal">{{harvnb|Miquel|Brice|Sourdel|Aubin|2011}}</ref> | ||

| ] is the area between the Euphrates and the Tigris from their sources down to ].<ref name="canard" /> ] is the area from Baghdad to the ].<ref name="miqueletal" /> In modern scientific usage, the term Mesopotamia often also has a chronological connotation. It is usually used to designate the area until the ] ] in the 7th century AD, with ] names like Syria, Jezirah and Iraq being used to describe the region after that date.<ref name="fosterpolingerfoster20096" /><ref>{{harvnb|Bahrani|1998}}</ref><ref group="nb">This page will use Mesopotamia in its widest geographical and chronological sense.</ref> | ] is the area between the Euphrates and the Tigris from their sources down to ].<ref name="canard" /> ] is the area from Baghdad to the ].<ref name="miqueletal" /> In modern scientific usage, the term Mesopotamia often also has a chronological connotation. It is usually used to designate the area until the ] ] in the 7th century AD, with ] names like Syria, Jezirah and Iraq being used to describe the region after that date.<ref name="fosterpolingerfoster20096" /><ref>{{harvnb|Bahrani|1998}}</ref><ref group="nb">This page will use Mesopotamia in its widest geographical and chronological sense.</ref> | ||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

| ===Chronology and periodization=== | ===Chronology and periodization=== | ||

| {{further|Chronology of the ancient Near East|ASPRO chronology|Dating methodologies in archaeology}} | {{further|Chronology of the ancient Near East|ASPRO chronology|Dating methodologies in archaeology}} | ||

| Two types of chronologies can be distinguished: a ] and an ]. The former establishes the order of phases, periods, cultures and reigns, whereas the latter establishes their absolute age expressed in years. In archaeology, relative chronologies are established by carefully excavating ]s and reconstructing their ] – the order in which layers were deposited. In general, newer remains are deposited on top of older material. Absolute chronologies are established by dating remains, or the layers in which they are found, through absolute dating methods. These methods include ] and the written record that can provide year names or ]s. | Two types of chronologies can be distinguished: a ] and an ]. The former establishes the order of phases, periods, cultures and reigns, whereas the latter establishes their absolute age expressed in years. In archaeology, relative chronologies are established by carefully excavating ]s and reconstructing their ] – the order in which layers were deposited. In general, newer remains are deposited on top of older material. Absolute chronologies are established by dating remains, or the layers in which they are found, through absolute dating methods. These methods include ], ] and the written record that can provide year names or ]s. | ||

| By combining absolute and relative dating methods, a chronological framework has been built for Mesopotamia that still incorporates many uncertainties but that also continues to be refined.<ref name=matthews20036566>{{harvnb|Matthews|2003|pp=65–66}}</ref><ref name=vandemieroop20074>{{harvnb|van de Mieroop|2007|p=4}}</ref> In this framework, many prehistorical and early historical periods have been defined on the basis of material culture that is thought to be representative for each period. These periods are often named after the site at which the material was recognized for the first time, as is for example the case for the ], ] and ]s.<ref name=matthews20036566/> When historical documents become widely available, periods tend to be named after the dominant dynasty or state; examples of this are the ] and ].<ref name=vandemieroop20073>{{harvnb|van de Mieroop|2007|p=3}}</ref> While reigns of kings can be securely dated for the 1st millennium BC, there is an increasingly large error margin toward the 2nd and 3rd millennia BC.<ref name=vandemieroop20074/> | By combining absolute and relative dating methods, a chronological framework has been built for Mesopotamia that still incorporates many uncertainties but that also continues to be refined.<ref name=matthews20036566>{{harvnb|Matthews|2003|pp=65–66}}</ref><ref name=vandemieroop20074>{{harvnb|van de Mieroop|2007|p=4}}</ref> In this framework, many prehistorical and early historical periods have been defined on the basis of material culture that is thought to be representative for each period. These periods are often named after the site at which the material was recognized for the first time, as is for example the case for the ], ] and ]s.<ref name=matthews20036566/> When historical documents become widely available, periods tend to be named after the dominant dynasty or state; examples of this are the ] and ].<ref name=vandemieroop20073>{{harvnb|van de Mieroop|2007|p=3}}</ref> While reigns of kings can be securely dated for the 1st millennium BC, there is an increasingly large error margin toward the 2nd and 3rd millennia BC.<ref name=vandemieroop20074/> | ||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

| ==Prehistory== | ==Prehistory== | ||

| {{Main |

{{Main|Prehistory of Mesopotamia}} | ||

| ===Pre-Pottery Neolithic period=== | ===Pre-Pottery Neolithic period=== | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

| <gallery widths="170" heights="170"> | <gallery widths="170" heights="170"> | ||

| File:Shanidar Cave - overview.jpg|Inside the Shanidar Cave, where the remains of eight adults and two infant ], dating from around 65,000–35,000 years ago were found, northern ]. | File:Shanidar Cave - overview.jpg|Inside the Shanidar Cave, where the remains of eight adults and two infant ]s, dating from around 65,000–35,000 years ago were found, northern ]. | ||

| File:Skeletal remains of Shanidar II, c. 60,000 to 45,000 BCE. Iraq Museum.jpg|Skeletal remains of ] II, c. 60,000 to 45,000 BCE. ] | File:Skeletal remains of Shanidar II, c. 60,000 to 45,000 BCE. Iraq Museum.jpg|Skeletal remains of ] II, c. 60,000 to 45,000 BCE. ] | ||

| File:Asikli Hoyuk sarah c murray 6176.jpg|Reconstitution of housing in ], Upper Mesopotamia, modern ]. | File:Asikli Hoyuk sarah c murray 6176.jpg|Reconstitution of housing in ], Upper Mesopotamia, modern ]. | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

| ====Ubaid culture (Southern Mesopotamia)==== | ====Ubaid culture (Southern Mesopotamia)==== | ||

| {{main|Ubaid culture}} | {{main|Ubaid culture}} | ||

| The ] (c. 6500–3800 BC)<ref>Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham '''' The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (2010) {{ISBN|978-1-885923-66-0}} p. 2; "Radiometric data suggest that the whole Southern Mesopotamian Ubaid period, including Ubaid 0 and 5, is of immense duration, spanning nearly three millennia from about 6500 to 3800 B.C."</ref> is a ] period of ]. The name derives from ] in Southern Mesopotamia, where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially by ] and later by ].<ref>Hall, Henry R. and Woolley, C. Leonard. 1927. ''Al-'Ubaid. Ur Excavations 1''. Oxford: Oxford University Press.</ref> | The ] (c. 6500–3800 BC)<ref>Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131115070526/http://oi.uchicago.edu/research/pubs/catalog/saoc/saoc63.html |date=2013-11-15 }}'' The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (2010) {{ISBN|978-1-885923-66-0}} p. 2; "Radiometric data suggest that the whole Southern Mesopotamian Ubaid period, including Ubaid 0 and 5, is of immense duration, spanning nearly three millennia from about 6500 to 3800 B.C."</ref> is a ] period of ]. The name derives from ] in Southern Mesopotamia, where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially by ] and later by ].<ref>Hall, Henry R. and Woolley, C. Leonard. 1927. ''Al-'Ubaid. Ur Excavations 1''. Oxford: Oxford University Press.</ref> | ||

| In South Mesopotamia the period is the earliest known period on the ] although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the ].<ref>Adams, Robert MCC. and Wright, Henry T. 1989. 'Concluding Remarks' in Henrickson, Elizabeth and Thuesen, Ingolf (eds.) ''Upon This Foundation - The ’Ubaid Reconsidered''. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 451-456.</ref> In the south it has a very long duration between about 6500 and 3800 BC when it is replaced by the ].<ref name="CarterRobert">Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham. 2010. 'Deconstructing the Ubaid' in Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham (eds.) ''Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East''. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. p. 2.</ref> | In South Mesopotamia the period is the earliest known period on the ] although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the ].<ref>Adams, Robert MCC. and Wright, Henry T. 1989. 'Concluding Remarks' in Henrickson, Elizabeth and Thuesen, Ingolf (eds.) ''Upon This Foundation - The ’Ubaid Reconsidered''. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 451-456.</ref> In the south it has a very long duration between about 6500 and 3800 BC when it is replaced by the ].<ref name="CarterRobert">Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham. 2010. 'Deconstructing the Ubaid' in Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham (eds.) ''Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East''. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. p. 2.</ref> | ||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

| | footer= | | footer= | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| In North Mesopotamia the period runs only between about 5300 and 4300 BC.<ref name="CarterRobert" /> It is preceded by the ] and the ] and succeeded by the Late Chalcolithic period. The new period is named Northern Ubaid to distinguish it from the proper Ubaid in southern Mesopotamia,<ref name="suz">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bRUMQb_1uKcC&pg=PA190|title= Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives|author1=Susan Pollock |author2=Reinhard Bernbeck |page= 190|year= 2009|isbn= 9781405137232}}</ref> and two explanations were presented for the transformation. The first maintain an invasion and a replacement of the Halafians by the Ubaidians; however, there is no hiatus between the Halaf and northern Ubaid that excludes the invasion theory.<ref name="gorg" /><ref name="aker2">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_4oqvpAHDEoC&pg=PA157|title= The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC)|author=Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz|page= 157|year= 2003|isbn= 9780521796668}}</ref> The most plausible theory is a Halafian adoption of the Ubaid culture.<ref name="gorg">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=klZX8B_RzzYC&pg=PT101|title= Ancient Iraq|author= Georges Roux|page= 101|year= 1992|isbn= 9780141938257}}</ref><ref name="suz" /><ref name="aker2" /><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jcOqDcDrNt4C&pg=PA128|title= Laser Ablation ICP-MS in Archaeological Research|author1=Robert J. Speakman |author2=Hector Neff |page= 128|year= 2005|isbn= 9780826332547}}</ref> | In North Mesopotamia the period runs only between about 5300 and 4300 BC.<ref name="CarterRobert" /> It is preceded by the ] and the ] and succeeded by the Late Chalcolithic period. The new period is named Northern Ubaid to distinguish it from the proper Ubaid in southern Mesopotamia,<ref name="suz">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bRUMQb_1uKcC&pg=PA190|title= Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives|author1=Susan Pollock |author2=Reinhard Bernbeck |page= 190|year= 2009|publisher= John Wiley & Sons|isbn= 9781405137232}}</ref> and two explanations were presented for the transformation. The first maintain an invasion and a replacement of the Halafians by the Ubaidians; however, there is no hiatus between the Halaf and northern Ubaid that excludes the invasion theory.<ref name="gorg" /><ref name="aker2">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_4oqvpAHDEoC&pg=PA157|title= The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC)|author=Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz|page= 157|year= 2003|publisher= Cambridge University Press|isbn= 9780521796668}}</ref> The most plausible theory is a Halafian adoption of the Ubaid culture.<ref name="gorg">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=klZX8B_RzzYC&pg=PT101|title= Ancient Iraq|author= Georges Roux|page= 101|year= 1992|publisher= Penguin Books Limited|isbn= 9780141938257}}</ref><ref name="suz" /><ref name="aker2" /><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jcOqDcDrNt4C&pg=PA128|title= Laser Ablation ICP-MS in Archaeological Research|author1=Robert J. Speakman |author2=Hector Neff |page= 128|year= 2005|publisher= UNM Press|isbn= 9780826332547}}</ref> | ||

| ===Uruk period=== | ===Uruk period=== | ||

| {{main|Uruk period}} | {{main|Uruk period}} | ||

| Named after the Sumerian city of ], this period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia. | |||

| Sumerian civilization took form in the ] (4th millennium BC), continuing into the ] and ] periods | |||

| .<ref>{{harvnb|Crawford|2004|p=75}}</ref> | |||

| The late Uruk period (34th to 32nd centuries) saw the gradual emergence of the ] and corresponds to the ]; it may also be called the "Protoliterate period". | |||

| ==Third millennium BC== | ==Third millennium BC== | ||

| Line 111: | Line 117: | ||

| {{Main|Akkadian Empire}} | {{Main|Akkadian Empire}} | ||

| ] (brown) and the directions in which military campaigns were conducted (yellow arrows)]] | ] (brown) and the directions in which military campaigns were conducted (yellow arrows)]] | ||

| ] |

] (brown) and its sphere of influence (red)]] | ||

| The Akkadian period is generally dated to 2350–2170 BC according to the ], or 2230–2050 BC according to the ].<ref name=pruss2004/> Around 2334 BC, Sargon became ruler of ] in northern ]. He proceeded to conquer an area stretching from the ] into modern-day ]. The Akkadians were a ] and the ] came into widespread use as the ] during this period, but literacy remained in the Sumerian language. The Akkadians further developed the Sumerian irrigation system with the incorporation of large ] and ] into the design to facilitate the reservoirs and canals required to transport water vast distances.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://mygeologypage.ucdavis.edu/cowen/~GEL115/115CH17oldirrigation.html |title=Ancient Irrigation |access-date=2013-04-23 |archive-date=2019-05-03 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190503125952/http://mygeologypage.ucdavis.edu/cowen/~GEL115/115CH17oldirrigation.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> The dynasty continued until around c. 2154 BC, and reached its zenith under ], who began the trend for rulers to claim divinity for themselves. | The Akkadian period is generally dated to 2350–2170 BC according to the ], or 2230–2050 BC according to the ].<ref name=pruss2004/> Around 2334 BC, Sargon became ruler of ] in northern ]. He proceeded to conquer an area stretching from the ] into modern-day ]. The Akkadians were a ] and the ] came into widespread use as the ] during this period, but literacy remained in the Sumerian language. The Akkadians further developed the Sumerian irrigation system with the incorporation of large ] and ] into the design to facilitate the reservoirs and canals required to transport water vast distances.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://mygeologypage.ucdavis.edu/cowen/~GEL115/115CH17oldirrigation.html |title=Ancient Irrigation |access-date=2013-04-23 |archive-date=2019-05-03 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190503125952/http://mygeologypage.ucdavis.edu/cowen/~GEL115/115CH17oldirrigation.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> The dynasty continued until around c. 2154 BC, and reached its zenith under ], who began the trend for rulers to claim divinity for themselves. | ||

| Line 154: | Line 160: | ||

| ===Hurrians=== | ===Hurrians=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| {{Main|Mitanni}} | {{Main|Mitanni}} | ||

| The ] were a people who settled in northwestern Mesopotamia and southeast Anatolia in 1600 BC. By 1450 BC they established a medium-sized empire under a ] ruling class, and temporarily made tributary vassals out of kings in the west, making them a major threat for the ] in Egypt until their overthrow by Assyria. The ] is related to the later ], but there is no conclusive evidence these two languages are related to any others. | The ] were a people who settled in northwestern Mesopotamia and southeast Anatolia in 1600 BC. By 1450 BC they established a medium-sized empire under a ] ruling class, and temporarily made tributary vassals out of kings in the west, making them a major threat for the ] in Egypt until their overthrow by Assyria. The ] is related to the later ], but there is no conclusive evidence these two languages are related to any others. | ||

| Line 200: | Line 206: | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| === Citations === | === Citations === | ||

| {{reflist|30}} | {{reflist|30}} | ||

| === Notes === | === Notes === | ||

| <references group="nb" /> | <references group="nb" /> | ||

| === Bibliography === | === Bibliography === | ||

| * {{cite book|title=The Archaeology of Syria. From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (ca. 16,000–300 BC)|last1=Akkermans|first1=Peter M.M.G.|last2=Schwartz|first2=Glenn M.|year=2003|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=Cambridge|isbn=0-521-79666-0}} | * {{cite book|title=The Archaeology of Syria. From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (ca. 16,000–300 BC)|last1=Akkermans|first1=Peter M.M.G.|last2=Schwartz|first2=Glenn M.|year=2003|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=Cambridge|isbn=0-521-79666-0}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last1=Bahrani|first1=Z.|editor1-last=Meskell|editor1-first=L.|title=Archaeology under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East|year=1998|publisher=Routledge|location=London|isbn=978-0-415-19655-0|pages=159–174|chapter=Conjuring Mesopotamia: Imaginative Geography a World Past}} | * {{cite book|last1=Bahrani|first1=Z.|author-link=Zainab Bahrani |editor1-last=Meskell|editor1-first=L.|title=Archaeology under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East|year=1998|publisher=Routledge|location=London|isbn=978-0-415-19655-0|pages=159–174|chapter=Conjuring Mesopotamia: Imaginative Geography and a World Past}} | ||

| * {{cite journal|last1=Banning|first1=E.B.|year=2011|title=So Fair a House. Göbekli Tepe and the Identification of Temples in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of the Near East|journal=Current Anthropology|volume=52|issue=5|pages=619–660|doi=10.1086/661207|s2cid=161719608}} | * {{cite journal|last1=Banning|first1=E.B.|year=2011|title=So Fair a House. Göbekli Tepe and the Identification of Temples in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of the Near East|journal=Current Anthropology|volume=52|issue=5|pages=619–660|doi=10.1086/661207|s2cid=161719608}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last1=Braidwood|first1=Robert J.|author-link1=Robert John Braidwood|last2=Howe|first2=Bruce|title=Prehistoric Investigations in Iraqi Kurdistan|url=http://oi.uchicago.edu/pdf/saoc31.pdf|series=Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization|volume=31|year=1960|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|oclc=395172}} | * {{cite book|last1=Braidwood|first1=Robert J.|author-link1=Robert John Braidwood|last2=Howe|first2=Bruce|title=Prehistoric Investigations in Iraqi Kurdistan|url=http://oi.uchicago.edu/pdf/saoc31.pdf|series=Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization|volume=31|year=1960|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|oclc=395172|access-date=2011-02-26|archive-date=2012-10-07|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121007235010/http://oi.uchicago.edu/pdf/saoc31.pdf|url-status=dead}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last1=Brinkman|first1=J.A.|editor1-last=Oppenheim|editor1-first=A.L.|editor1-link=A. Leo Oppenheim|title=Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization|year=1977|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|isbn=0-226-63186-9|pages=|chapter=Appendix: Mesopotamian Chronology of the Historical Period|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/ancientmesopotam00aleo/page/335}} | * {{cite book|last1=Brinkman|first1=J.A.|editor1-last=Oppenheim|editor1-first=A.L.|editor1-link=A. Leo Oppenheim|title=Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization|year=1977|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|isbn=0-226-63186-9|pages=|chapter=Appendix: Mesopotamian Chronology of the Historical Period|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/ancientmesopotam00aleo/page/335}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last1=Canard|first1=M.|editor1-first=P.|editor1-last=Bearman|editor2-first=Th.|editor2-last=Bianquis|editor3-first=C.E.|editor3-last=Bosworth|editor4-first=E.|editor4-last=van Donzel|editor5-first=W.P.|editor5-last=Heinrichs|editor3-link=Clifford Edmund Bosworth|title=Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition|year=2011|publisher=Brill Online|location=Leiden|chapter=al-ḎJazīra, Ḏjazīrat Aḳūr or Iḳlīm Aḳūr|oclc=624382576}} | * {{cite book|last1=Canard|first1=M.|editor1-first=P.|editor1-last=Bearman|editor2-first=Th.|editor2-last=Bianquis|editor3-first=C.E.|editor3-last=Bosworth|editor4-first=E.|editor4-last=van Donzel|editor5-first=W.P.|editor5-last=Heinrichs|editor3-link=Clifford Edmund Bosworth|title=Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition|year=2011|publisher=Brill Online|location=Leiden|chapter=al-ḎJazīra, Ḏjazīrat Aḳūr or Iḳlīm Aḳūr|oclc=624382576}} | ||

| Line 242: | Line 250: | ||

| * {{cite book|last=van de Mieroop|first=M.|author-link=Marc Van de Mieroop|title=A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC|year=2007|publisher=Blackwell|location=Malden|isbn=978-0-631-22552-2}} | * {{cite book|last=van de Mieroop|first=M.|author-link=Marc Van de Mieroop|title=A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC|year=2007|publisher=Blackwell|location=Malden|isbn=978-0-631-22552-2}} | ||

| * {{cite journal|last1=Wilkinson|first1=Tony J.|year=2000|title=Regional Approaches to Mesopotamian Archaeology: the Contribution of Archaeological Surveys|journal=Journal of Archaeological Research|volume=8|issue=3|pages=219–267|issn=1573-7756|doi=10.1023/A:1009487620969|s2cid=140771958}} | * {{cite journal|last1=Wilkinson|first1=Tony J.|year=2000|title=Regional Approaches to Mesopotamian Archaeology: the Contribution of Archaeological Surveys|journal=Journal of Archaeological Research|volume=8|issue=3|pages=219–267|issn=1573-7756|doi=10.1023/A:1009487620969|s2cid=140771958}} | ||

| * {{cite book|title=Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture|last=Woods|first=Christopher|editor1-last=Sanders|editor1-first=S.L.|year=2006|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|pages=91–120|chapter-url=http://oi.uchicago.edu/pdf/OIS2.pdf|chapter=Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian}} | * {{cite book|title=Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture|last=Woods|first=Christopher|editor1-last=Sanders|editor1-first=S.L.|year=2006|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|pages=91–120|chapter-url=http://oi.uchicago.edu/pdf/OIS2.pdf|chapter=Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian|access-date=2010-03-29|archive-date=2013-04-29|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130429121058/http://oi.uchicago.edu/pdf/OIS2.pdf|url-status=dead}} | ||

| * {{cite book|last1=Woods|first1=Christopher|editor1-first=Christopher|editor1-last=Woods|title=Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond|chapter-url=http://oi.uchicago.edu/pdf/oimp32.pdf|series=Oriental Institute Museum Publications|volume=32|year=2010|publisher=University of Chicago|location=Chicago|isbn=978-1-885923-76-9|chapter=The Earliest Mesopotamian Writing|pages=33–50}} | * {{cite book|last1=Woods|first1=Christopher|editor1-first=Christopher|editor1-last=Woods|title=Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond|chapter-url=http://oi.uchicago.edu/pdf/oimp32.pdf|series=Oriental Institute Museum Publications|volume=32|year=2010|publisher=University of Chicago|location=Chicago|isbn=978-1-885923-76-9|chapter=The Earliest Mesopotamian Writing|pages=33–50|access-date=2011-08-10|archive-date=2021-08-26|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210826005847/https://oi.uchicago.edu//sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/oimp32.pdf|url-status=dead}} | ||

| * {{cite book|title=The Sumerians|last=Woolley|first=C.L.|author-link=Leonard Woolley|year=1965|publisher=W.W. Norton|location=New York}} | * {{cite book|title=The Sumerians|last=Woolley|first=C.L.|author-link=Leonard Woolley|year=1965|publisher=W.W. Norton|location=New York}} | ||

Latest revision as of 12:12, 24 December 2024

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Civilization of Mesopotamia ranges from the earliest human occupation in the Paleolithic period up to Late antiquity. This history is pieced together from evidence retrieved from archaeological excavations and, after the introduction of writing in the late 4th millennium BC, an increasing amount of historical sources. While in the Paleolithic and early Neolithic periods only parts of Upper Mesopotamia were occupied, the southern alluvium was settled during the late Neolithic period. Mesopotamia has been home to many of the oldest major civilizations, entering history from the Early Bronze Age, for which reason it is often called a cradle of civilization.

Short outline of Mesopotamia

Main articles: Mesopotamia and Geography of Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia (Ancient Greek: Μεσοποταμία, romanized: Mesopotamíā; Classical Syriac: ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, lit. 'Bēṯ Nahrēn') means "Between the Rivers". The oldest known occurrence of the name Mesopotamia dates to the 4th century BC, when it was used to designate the area between the Euphrates and the Tigris. The name was presumably translated from a term already current in the area—probably in Aramaic—and apparently was understood to mean the land lying "between the (Euphrates and Tigris) rivers", now Iraq.

Later and in the broader sense, the historical region included not only the area of present-day Iraq, but also parts of present-day Iran, Syria and Turkey. The neighbouring steppes to the west of the Euphrates and the western part of the Zagros Mountains are also often included under the wider term Mesopotamia. A further distinction is usually made between Upper or Northern Mesopotamia and Lower or Southern Mesopotamia.

Upper Mesopotamia is the area between the Euphrates and the Tigris from their sources down to Baghdad. Lower Mesopotamia is the area from Baghdad to the Persian Gulf. In modern scientific usage, the term Mesopotamia often also has a chronological connotation. It is usually used to designate the area until the Arab Muslim conquests in the 7th century AD, with Arabic names like Syria, Jezirah and Iraq being used to describe the region after that date.

Chronology and periodization

Further information: Chronology of the ancient Near East, ASPRO chronology, and Dating methodologies in archaeologyTwo types of chronologies can be distinguished: a relative chronology and an absolute chronology. The former establishes the order of phases, periods, cultures and reigns, whereas the latter establishes their absolute age expressed in years. In archaeology, relative chronologies are established by carefully excavating archaeological sites and reconstructing their stratigraphy – the order in which layers were deposited. In general, newer remains are deposited on top of older material. Absolute chronologies are established by dating remains, or the layers in which they are found, through absolute dating methods. These methods include radiocarbon dating, dendrochronology and the written record that can provide year names or calendar dates.

By combining absolute and relative dating methods, a chronological framework has been built for Mesopotamia that still incorporates many uncertainties but that also continues to be refined. In this framework, many prehistorical and early historical periods have been defined on the basis of material culture that is thought to be representative for each period. These periods are often named after the site at which the material was recognized for the first time, as is for example the case for the Halaf, Ubaid and Jemdet Nasr periods. When historical documents become widely available, periods tend to be named after the dominant dynasty or state; examples of this are the Ur III and Old Babylonian periods. While reigns of kings can be securely dated for the 1st millennium BC, there is an increasingly large error margin toward the 2nd and 3rd millennia BC.

The chronology for much of the third and second millennia BC is subject to much debate. Based on different estimates for the length of periods for which still very few historical documents are available, so-called Ultra-long, Long, Middle, Short and Ultra-short Chronologies have been proposed by various scholars, varying by as much as 150 years in their dating of specific periods. Despite problems with the Middle Chronology, this chronological framework continues to be used by many recent handbooks on the archaeology and history of the ancient Near East. A study from 2001 published high-resolution radiocarbon dates from Turkey supporting dates for the 2nd millennium BC that are very close to those proposed by the Middle Chronology.

Prehistory

Main article: Prehistory of MesopotamiaPre-Pottery Neolithic period

The early Neolithic human occupation of Mesopotamia is, like the previous Epipaleolithic period, confined to the foothill zones of the Taurus and Zagros Mountains and the upper reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates valleys. The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) period (10,000–8,700 BC) saw the introduction of agriculture, while the oldest evidence for animal domestication dates to the transition from the PPNA to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB, 8700–6800 BC) at the end of the 9th millennium BC. This transition has been documented at sites like Abu Hureyra and Mureybet, which continued to be occupied from the Natufian well into the PPNB. The so-far earliest monumental sculptures and circular stone buildings from Göbekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey date to the PPNA/Early PPNB and represent, according to the excavator, the communal efforts of a large community of hunter-gatherers.

-

Inside the Shanidar Cave, where the remains of eight adults and two infant Neanderthals, dating from around 65,000–35,000 years ago were found, northern Iraq.

Inside the Shanidar Cave, where the remains of eight adults and two infant Neanderthals, dating from around 65,000–35,000 years ago were found, northern Iraq.

-

Skeletal remains of Shanidar II, c. 60,000 to 45,000 BCE. Iraq Museum

Skeletal remains of Shanidar II, c. 60,000 to 45,000 BCE. Iraq Museum

-

Reconstitution of housing in Aşıklı Höyük, Upper Mesopotamia, modern Turkey.

Reconstitution of housing in Aşıklı Höyük, Upper Mesopotamia, modern Turkey.

-

Jar in calcite alabaster, Syria, late 8th millennium BC.

Jar in calcite alabaster, Syria, late 8th millennium BC.

-

Mace-head, late 8th millennium BC.

Mace-head, late 8th millennium BC.

-

Alabaster pot Mid-Euphrates region, 6500 BC, Louvre Museum

Alabaster pot Mid-Euphrates region, 6500 BC, Louvre Museum

-

Alabaster pot, Mid-Euphrates region, 6500 BC, Louvre Museum

Alabaster pot, Mid-Euphrates region, 6500 BC, Louvre Museum

-

Female statuette, 8th millennium BC, Syria.

Female statuette, 8th millennium BC, Syria.

Chalcolithic period

The Fertile Crescent was inhabited by several distinct, flourishing cultures between the end of the last ice age (c. 10,000 BC) and the beginning of history. One of the oldest known Neolithic sites in Mesopotamia is Jarmo, settled around 7000 BC and broadly contemporary with Jericho (in the Levant) and Çatalhöyük (in Anatolia). It as well as other early Neolithic sites, such as Samarra and Tell Halaf were in northern Mesopotamia; later settlements in southern Mesopotamia required complicated irrigation methods. The first of these was Eridu, settled during the Ubaid period culture by farmers who brought with them the Samarran culture from the north.

Halaf culture (Northwestern Mesopotamia)

Main article: Halaf culturePottery was decorated with abstract geometric patterns and ornaments, especially in the Halaf culture, also known for its clay fertility figurines, painted with lines. Clay was all around and the main material; often modelled figures were painted with black decoration. Carefully crafted and dyed pots, especially jugs and bowls, were traded. As dyes, iron oxide containing clays were diluted in different degrees or various minerals were mixed to produce different colours.

Hassuna culture (Northern Mesopotamia)

Main article: Hassuna cultureThe Hassuna culture is a Neolithic archaeological culture in northern Mesopotamia dating to the early sixth millennium BC. It is named after the type site of Tell Hassuna in Iraq. Other sites where Hassuna material has been found include Tell Shemshara.

Samarra culture (Central Mesopotamia)

Main article: Samarra culture

The Samarra culture is a Chalcolithic archaeological culture in northern Mesopotamia that is roughly dated to 5500–4800 BCE. It partially overlaps with the Hassuna and early Ubaid.

Ubaid culture (Southern Mesopotamia)

Main article: Ubaid cultureThe Ubaid period (c. 6500–3800 BC) is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid in Southern Mesopotamia, where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Woolley.

In South Mesopotamia the period is the earliest known period on the alluvial plain although it is likely earlier periods exist obscured under the alluvium. In the south it has a very long duration between about 6500 and 3800 BC when it is replaced by the Uruk period.

Northern expansion of Ubaid culture

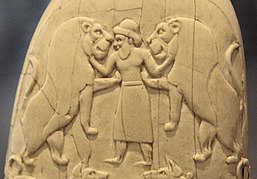

Uruk period "King-Priest" Mesopotamian king as Master of Animals on the Gebel el-Arak Knife, dated circa 3300-3200 BC, Abydos, Egypt. This work of art suggests early Egypt-Mesopotamia relations, showing the influence of Mesopotamia on Egypt at an early date, and the state of Mesopotamian royal iconography during the Uruk period. Louvre Museum.

Mesopotamian king as Master of Animals on the Gebel el-Arak Knife, dated circa 3300-3200 BC, Abydos, Egypt. This work of art suggests early Egypt-Mesopotamia relations, showing the influence of Mesopotamia on Egypt at an early date, and the state of Mesopotamian royal iconography during the Uruk period. Louvre Museum. Similar portrait of a probable Uruk King-Priest with a brimmed round hat and large beard, excavated in Uruk and dated to 3300 BC. Louvre Museum.

Similar portrait of a probable Uruk King-Priest with a brimmed round hat and large beard, excavated in Uruk and dated to 3300 BC. Louvre Museum.

In North Mesopotamia the period runs only between about 5300 and 4300 BC. It is preceded by the Halaf period and the Halaf-Ubaid Transitional period and succeeded by the Late Chalcolithic period. The new period is named Northern Ubaid to distinguish it from the proper Ubaid in southern Mesopotamia, and two explanations were presented for the transformation. The first maintain an invasion and a replacement of the Halafians by the Ubaidians; however, there is no hiatus between the Halaf and northern Ubaid that excludes the invasion theory. The most plausible theory is a Halafian adoption of the Ubaid culture.

Uruk period

Main article: Uruk periodNamed after the Sumerian city of Uruk, this period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia.

Sumerian civilization took form in the Uruk period (4th millennium BC), continuing into the Jemdet Nasr and Early Dynastic periods

.

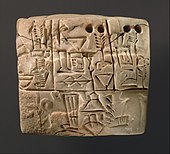

The late Uruk period (34th to 32nd centuries) saw the gradual emergence of the cuneiform script and corresponds to the Early Bronze Age; it may also be called the "Protoliterate period".

Third millennium BC

Jemdet Nasr period

Main article: Jemdet Nasr period

The Jemdet Nasr period, named after the type-site Jemdet Nasr, is generally dated to 3100–2900 BC. It was first distinguished on the basis of distinctive painted monochrome and polychrome pottery with geometric and figurative designs. The cuneiform writing system that had been developed during the preceding Uruk period was further refined. While the language in which these tablets were written cannot be identified with certainty for this period, it is thought to be Sumerian. The texts deal with administrative matters like the rationing of foodstuffs or lists of objects or animals. Settlements during this period were highly organized around a central building that controlled all aspects of society. The economy focused on local agricultural production and sheep-and-goat pastoralism. The homogeneity of the Jemdet Nasr period across a large area of southern Mesopotamia indicates intensive contacts and trade between settlements. This is strengthened by the find of a sealing at Jemdet Nasr that lists a number of cities that can be identified, including Ur, Uruk and Larsa.

Early Dynastic period

Main article: Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia)

The entire Early Dynastic period is generally dated to 2900–2350 BC according to the Middle Chronology, or 2800–2230 BC according to the Short Chronology. The Sumerians were firmly established in Mesopotamia by the middle of the 4th millennium BC, in the archaeological Uruk period, although scholars dispute when they arrived. It is hard to tell where the Sumerians might have come from because the Sumerian language is a language isolate, unrelated to any other known language. Their mythology includes many references to the area of Mesopotamia but little clue regarding their place of origin, perhaps indicating that they had been there for a long time. The Sumerian language is identifiable from its initially logographic script which arose last half of the 4th millennium BC.

By the 3rd millennium BC, these urban centers had developed into increasingly complex societies. Irrigation and other means of exploiting food sources were being used to amass large surpluses. Huge building projects were being undertaken by rulers, and political organization was becoming ever more sophisticated. Throughout the millennium, the various city-states Kish, Uruk, Ur and Lagash vied for power and gained hegemony at various times. Nippur and Girsu were important religious centers, as was Eridu at this point. This was also the time of Gilgamesh, a semi-historical king of Uruk, and the subject of the famous Epic of Gilgamesh. By 2600 BC, the logographic script had developed into a decipherable cuneiform syllabic script.

The chronology of this era is particularly uncertain due to difficulties in our understanding of the text, our understanding of the material culture of the Early Dynastic period and a general lack of radiocarbon dates for sites in Iraq. Also, the multitude of city-states makes for a confusing situation, as each has its own history. In the past, the Sumerian King List was considered to be an important historical source, but recent scholarship has dismissed the utility of this text up to the point that it should not be used at all for the reconstruction of Early Dynastic political history.

Enshakushanna of Uruk conquered all of Sumer, Akkad, and Hamazi, followed by Eannatum of Lagash who also conquered Sumer. His methods were force and intimidation (see the Stele of the Vultures), and soon after his death, the cities rebelled and the empire again fell apart. Some time later, Lugal-Anne-Mundu of Adab created the first, if short-lived, empire to extend west of Mesopotamia, at least according to historical accounts dated centuries later. The last native Sumerian to rule over most of Sumer before Sargon of Akkad established supremacy was Lugal-Zage-Si.

Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as the spoken language of Mesopotamia somewhere around the turn of the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC (the exact dating being a matter of debate), but Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary and scientific language in Mesopotamia until the 1st century AD.

Akkadian Empire

Main article: Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian period is generally dated to 2350–2170 BC according to the Middle Chronology, or 2230–2050 BC according to the Short Chronology. Around 2334 BC, Sargon became ruler of Akkad in northern Mesopotamia. He proceeded to conquer an area stretching from the Persian Gulf into modern-day Syria. The Akkadians were a Semitic people and the Akkadian language came into widespread use as the lingua franca during this period, but literacy remained in the Sumerian language. The Akkadians further developed the Sumerian irrigation system with the incorporation of large weirs and diversion dams into the design to facilitate the reservoirs and canals required to transport water vast distances. The dynasty continued until around c. 2154 BC, and reached its zenith under Naram-Sin, who began the trend for rulers to claim divinity for themselves.

The Akkadian Empire lost power after the reign of Naram-Sin, and eventually was invaded by the Guti from the Zagros Mountains. For half a century the Guti controlled Mesopotamia, especially the south, but they left few inscriptions, so they are not well understood. The Guti hold loosened on southern Mesopotamia, where the second dynasty of Lagash came into prominence. Its most famous ruler was Gudea, who left many statues of himself in temples across Sumer.

Ur III period

Main article: Third Dynasty of UrEventually the Guti were overthrown by Utu-hengal of Uruk, and the various city-states again vied for power. Power over the area finally went to the city-state of Ur, when Ur-Nammu founded the Ur III Empire (2112–2004 BC) and conquered the Sumerian region. Under his son Shulgi, state control over industry reached a level never again seen in the region. Shulgi may have devised the Code of Ur-Nammu, one of the earliest known law codes (three centuries before the more famous Code of Hammurabi). Around 2000 BC, the power of Ur waned, and the Amorites came to occupy much of the area, although it was Sumer's long-standing rivals to the east, the Elamites, who finally overthrew Ur. In the north, Assyria remained free of Amorite control until the very end of the 19th century BC. This marked the end of city-states ruling empires in Mesopotamia, and the end of Sumerian dominance, but the succeeding rulers adopted much of Sumerian civilization as their own.

Second millennium BC

Old Assyrian Period

Of the early history of the kingdom of Assyria, little is positively known. The Assyrian King List mentions rulers going back to the 23rd and 22nd century BC. The earliest king named Tudiya, who was a contemporary of Ibrium of Ebla, appears to have lived in the mid-23rd century BC, according to the king list. Tudiya concluded a treaty with Ibrium for the use of a trading post in the Levant officially controlled by Ebla. Apart from this reference to trading activity, nothing further has yet been discovered about Tudiya. He was succeeded by Adamu and then a further thirteen rulers about all of whom nothing is yet known. These early kings from the 23rd to late 21st centuries BC, who are recorded as kings who lived in tents were likely to have been semi nomadic pastoralist rulers, nominally independent but subject to the Akkadian Empire, who dominated the region and at some point during this period became fully urbanised and founded the city state of Ashur. A king named Ushpia (c. 2030 BC) is credited with dedicating temples to Ashur in the home city of the god. In around 1975 BC Puzur-Ashur I founded a new dynasty, and his successors such as Shalim-ahum, Ilushuma (1945–1906 BC), Erishum I (1905–1867 BC), Ikunum (1867–1860 BC), Sargon I, Naram-Sin and Puzur-Ashur II left inscriptions regarding the building of temples to Ashur, Adad and Ishtar in Assyria. Ilushuma in particular appears to have been a powerful king and the dominant ruler in the region, who made many raids into southern Mesopotamia between 1945 BC and 1906 BC, attacking the independent Sumero-Akkadian city states of the region such as Isin, and founding colonies in Asia Minor. This was to become a pattern throughout the history of ancient Mesopotamia with the future rivalry between Assyria and Babylonia. However, Babylonia did not exist at this time, but was founded in 1894 BC by an Amorite prince named Sumuabum during the reign of Erishum I.

Isin-Larsa, Old Babylonian and Shamshi-Adad I

(Isin-Larsa period)

Original relief.

Original relief. Components of the relief.

Components of the relief.

The next two centuries or so, called the Isin-Larsa period, saw southern Mesopotamia dominated by the Amorite cities of Isin and Larsa, as the two cities vied for dominance. This period also marked a growth in power in the north of Mesopotamia. An Assyrian king named Ilushuma (1945–1906 BC) became a dominant figure in Mesopotamia, raiding the southern city states and founding colonies in Asia Minor. Eshnunna and Mari, two Amorite ruled states also became important in the north.

Babylonia was founded as an independent state by an Amorite chieftain named Sumuabum in 1894 BC. For over a century after its founding, it was a minor and relatively weak state, overshadowed by older and more powerful states such as Isin, Larsa, Assyria and Elam. However, Hammurabi (1792 BC to 1750 BC), the Amorite ruler of Babylon, turned Babylon into a major power and eventually conquered Mesopotamia and beyond. He is famous for his law code and conquests, but he is also famous due to the large amount of records that exist from the period of his reign. After the death of Hammurabi, the first Babylonian dynasty lasted for another century and a half, but his empire quickly unravelled, and Babylon once more became a small state. The Amorite dynasty ended in 1595 BC, when Babylonia fell to the Hittite king Mursilis, after which the Kassites took control.

Unlike the south of Mesopotamia, the native Akkadian kings of Assyria repelled Amorite advances during the 20th and 19th centuries BC. However this changed in 1813 BC when an Amorite king named Shamshi-Adad I usurped the throne of Assyria. Although claiming descendency from the native Assyrian king Ushpia, he was regarded as an interloper. Shamshi-Adad I created a regional empire in Assyria, maintaining and expanding the established colonies in Asia Minor and Syria. His son Ishme-Dagan I continued this process, however his successors were eventually conquered by Hammurabi, a fellow Amorite from Babylon. The three Amorite kings succeeding Ishme-Dagan were vassals of Hammurabi, but after his death, a native Akkadian vice regent Puzur-Sin overthrew the Amorites of Babylon and a period of civil war with multiple claimants to the throne ensued, ending with the succession of king Adasi c. 1720 BC.

Middle Assyrian Period and Empire

The Middle Assyrian period begins c. 1720 BC with the ejection of Amorites and Babylonians from Assyria by a king called Adasi. The nation remained relatively strong and stable, peace was made with the Kassite rulers of Babylonia, and Assyria was free from Hittite, Hurrian, Gutian, Elamite and Mitanni threat. However a period of Mitanni domination occurred from the mid-15th to early 14th centuries BC. This was ended by Eriba-Adad I (1392 BC - 1366), and his successor Ashur-uballit I completely overthrew the Mitanni Empire and founded a powerful Assyrian Empire that came to dominate Mesopotamia and much of the ancient Near East (including Babylonia, Asia Minor, Iran, the Levant and parts of the Caucasus and Arabia), with Assyrian armies campaigning from the Mediterranean Sea to the Caspian, and from the Caucasus to Arabia. The empire endured until 1076 BC with the death of Tiglath-Pileser I. During this period Assyria became a major power, overthrowing the Mitanni Empire, annexing swathes of Hittite, Hurrian and Amorite land, sacking and dominating Babylon, Canaan/Phoenicia and becoming a rival to Egypt.

Kassite dynasty of Babylon

Main article: KassitesAlthough the Hittites overthrew Babylon, another people, the Kassites, took it as their capital (c. 1650–1155 BC (short chronology)). They have the distinction of being the longest lasting dynasty in Babylon, reigning for over four centuries. They left few records, so this period is unfortunately obscure. They are of unknown origin; what little we have of their language suggests it is a language isolate. Although Babylonia maintained its independence through this period, it was not a power in the Near East, and mostly sat out the large wars fought over the Levant between Egypt, the Hittite Empire, and Mitanni (see below), as well as independent peoples in the region. Assyria participated in these wars toward the end of the period, overthrowing the Mitanni Empire and besting the Hittites and Phrygians, but the Kassites in Babylon did not. They did, however, fight against their longstanding rival to the east, Elam (related by some linguists to the Dravidian languages in modern India). Babylonia found itself under Assyrian and Elamite domination for much of the later Kassite period. In the end, the Elamites conquered Babylon, bringing this period to an end.

Hurrians

The Hurrians were a people who settled in northwestern Mesopotamia and southeast Anatolia in 1600 BC. By 1450 BC they established a medium-sized empire under a Mitanni ruling class, and temporarily made tributary vassals out of kings in the west, making them a major threat for the Pharaoh in Egypt until their overthrow by Assyria. The Hurrian language is related to the later Urartian, but there is no conclusive evidence these two languages are related to any others.

Hittites

Main article: HittitesBy 1300 BC the Hurrians had been reduced to their homelands in Asia Minor after their power was broken by the Assyrians and Hittites, and held the status of vassals to the "Hatti", the Hittites, a western Indo-European people (belonging to the linguistic "centum" group) who dominated most of Asia Minor (modern Turkey) at this time from their capital of Hattusa. The Hittites came into conflict with the Assyrians from the mid-14th to the 13th centuries BC, losing territory to the Assyrian kings of the period. However they endured until being finally swept aside by the Phrygians, who conquered their homelands in Asia Minor. The Phrygians were prevented from moving south into Mesopotamia by the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I. The Hittites fragmented into a number of small Neo-Hittite states, which endured in the region for many centuries.

Bronze Age collapse

Main article: Bronze Age collapseRecords from the 12th and 11th centuries BC are sparse in Babylonia, which had been overrun with new Semitic settlers, namely the Arameans, Chaldeans and Sutu. Assyria however, remained a compact and strong nation, which continued to provide much written record. The 10th century BC is even worse for Babylonia, with very few inscriptions. Mesopotamia was not alone in this obscurity: the Hittite Empire fell at the beginning of this period and very few records are known from Egypt and Elam. This was a time of invasion and upheaval by many new people throughout the Near East, North Africa, The Caucasus, Mediterranean and Balkan regions.

First millennium BC

Neo-Assyrian Empire

Main article: Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire is usually considered to have begun with the accession of Adad-nirari II, in 911 BC, lasting until the fall of Nineveh at the hands of the Babylonians, Medes, Scythians and Cimmerians in 612 BC. The empire was the largest and most powerful the world had yet seen. At its height Assyria conquered the 25th Dynasty Egypt (and expelled its Nubian/Kushite dynasty) as well as Babylonia, Chaldea, Elam, Media, Persia, Urartu, Phoenicia, Aramea/Syria, Phrygia, the Neo-Hittites, Hurrians, northern Arabia, Gutium, Israel, Judah, Moab, Edom, Corduene, Cilicia, Mannea and parts of Ancient Greece (such as Cyprus), and defeated and/or exacted tribute from Scythia, Cimmeria, Lydia, Nubia, Ethiopia and others.

Neo-Babylonian Empire

Main article: Neo-Babylonian EmpireThe Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire was a period of Mesopotamian history which began in 620 BC and ended in 539 BC. During the preceding three centuries, Babylonia had been ruled by their fellow Akkadian speakers and northern neighbours, Assyria. The Assyrians had managed to maintain Babylonian loyalty through the Neo-Assyrian period, whether through granting of increased privileges, or militarily, but that finally changed after 627 BC with the death of the last strong Assyrian ruler, Ashurbanipal, and Babylonia rebelled under Nabopolassar a Chaldean chieftain the following year. In alliance with king Cyaxares of the Medes, and with the help of the Scythians and Cimmerians the city of Nineveh was sacked in 612 BC, Assyria fell by 605 BC and the seat of empire was transferred to Babylonia for the first time since Hammurabi.

Classical Antiquity to Late Antiquity

After the death of Ashurbanipal in 627 BC, the Assyrian empire descended into a series of bitter civil wars, allowing its former vassals to free themselves. Cyaxares reorganized and modernized the Median Army, then joined with King Nabopolassar of Babylon. These allies, together with the Scythians, overthrew the Assyrian Empire and destroyed Nineveh in 612 BC. After the final victory at Carchemish in 605 BC the Medes and Babylonians ruled Assyria. Babylon and Media fell under Persian rule in the 6th century BC (Cyrus the Great).

For two centuries of Achaemenid rule both Assyria and Babylonia flourished, Achaemenid Assyria in particular becoming a major source of manpower for the army and a breadbasket for the economy. Mesopotamian Aramaic remained the lingua franca of the Achaemenid Empire, much as it had done in Assyrian times. Mesopotamia fell to Alexander the Great in 330 BC, and remained under Hellenistic rule for another two centuries, with Seleucia as capital from 305 BC. In the 1st century BC, Mesopotamia was in constant turmoil as the Seleucid Empire was weakened by Parthia on one hand and the Mithridatic Wars on the other. The Parthian Empire lasted for five centuries, into the 3rd century AD, when it was succeeded by the Sassanids. After constant wars between Romans and first Parthians, later Sassanids; the western part of Mesopotamia was passed to the Roman Empire. Christianity as well as Mandeism entered Mesopotamia from the 1st to 3rd centuries AD, and flourished, particularly in Assyria (Assuristan in Sassanid Persian), which became the center of the Assyrian Church of the East and a flourishing Syriac Christian tradition which remains to this day. A number of Neo-Assyrian kingdoms arose, in particular Adiabene. The Sassanid Empire and Byzantine Mesopotamia finally fell to the Rashidun army under Khalid ibn al-Walid in the 630s. After the Arab-Islamic conquest of the mid-7th century AD, Mesopotamia saw an influx of non native Arabs and later also Turkic peoples. The city of Assur was still occupied until the 14th century, and Assyrians possibly still formed the majority in northern Mesopotamia until the Middle Ages. Assyrians retain Eastern Rite Christianity whereas the Mandaeans retain their ancient gnostic religion and Mesopotamian Aramaic as a mother tongue and written script to this day. Among these peoples, the giving of traditional Mesopotamian names is still common.

- Classical Antiquity

- Median and Babylonian Assyria (605 to 549 BC)

- Persian Babylonia,

- Achaemenid Assyria (6th to 4th centuries BC)

- Seleucid Mesopotamia (4th to 2nd centuries BC)

- Parthian Asuristan (Assyria) (2nd century BC to 3rd century AD)

- Osroene (2nd century BC to 3rd century AD)

- Adiabene (1st to 2nd centuries AD)

- Roman Mesopotamia (2nd to 7th centuries AD), Roman Assyria (2nd century AD)

- Late Antiquity

- Sassanid Asuristan (Assyria) (3rd to 7th centuries AD)

- Arab Muslim conquest of Mesopotamia, dissolution of Assyria (633–651 AD)

See also

- Assyria

- Babylonia

- Cradle of civilization

- History of institutions in Mesopotamia

- History of Iraq

- Levantine Iron Age Anomaly

- Music of Mesopotamia

- Sumer

References

Citations

- Finkelstein 1962, p. 73

- "history of Mesopotamia | Definition, Civilization, Summary, Agriculture, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-04-30.

- "How Mesopotamia Became Iraq (and Why It Matters)". Los Angeles Times. 1990-09-02. Retrieved 2022-04-30.

- Wood, Michael (2010-11-10). "The Ancient World | Mesopotamia". the Guardian. Retrieved 2022-04-30.

- Seymour, Michael (2004). "Ancient Mesopotamia and Modern Iraq in the British Press, 1980–2003". Current Anthropology. 45 (3): 351–368. doi:10.1086/383004. ISSN 0011-3204. JSTOR 10.1086/383004. S2CID 224788984.

- Miquel et al. 2011.

- ^ Foster & Polinger Foster 2009, p. 6

- ^ Canard 2011

- Wilkinson 2000, pp. 222–223

- Matthews 2003, p. 5

- ^ Miquel et al. 2011

- Bahrani 1998

- ^ Matthews 2003, pp. 65–66

- ^ van de Mieroop 2007, p. 4

- van de Mieroop 2007, p. 3

- Brinkman 1977

- Gasche et al. 1998

- Kuhrt 1997, p. 12

- Potts 1999, p. xxix

- Akkermans & Schwartz 2003, p. 13

- Sagona & Zimansky 2009, p. 251

- Manning et al. 2001

- Moore, Hillman & Legge 2000

- Akkermans & Schwartz 2003

- Schmidt 2003

- Banning 2011

- Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East (Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, Number 63) Archived 2013-11-15 at the Wayback Machine The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (2010) ISBN 978-1-885923-66-0 p. 2; "Radiometric data suggest that the whole Southern Mesopotamian Ubaid period, including Ubaid 0 and 5, is of immense duration, spanning nearly three millennia from about 6500 to 3800 B.C."

- Hall, Henry R. and Woolley, C. Leonard. 1927. Al-'Ubaid. Ur Excavations 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Adams, Robert MCC. and Wright, Henry T. 1989. 'Concluding Remarks' in Henrickson, Elizabeth and Thuesen, Ingolf (eds.) Upon This Foundation - The ’Ubaid Reconsidered. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 451-456.

- ^ Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham. 2010. 'Deconstructing the Ubaid' in Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham (eds.) Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. p. 2.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- Cooper, Jerrol S. (1996). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. pp. 10–14. ISBN 9780931464966.

- "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ Susan Pollock; Reinhard Bernbeck (2009). Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives. John Wiley & Sons. p. 190. ISBN 9781405137232.

- ^ Georges Roux (1992). Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books Limited. p. 101. ISBN 9780141938257.

- ^ Peter M. M. G. Akkermans, Glenn M. Schwartz (2003). The Archaeology of Syria: From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c.16,000-300 BC). Cambridge University Press. p. 157. ISBN 9780521796668.

- Robert J. Speakman; Hector Neff (2005). Laser Ablation ICP-MS in Archaeological Research. UNM Press. p. 128. ISBN 9780826332547.

- Crawford 2004, p. 75

- Pollock 1999, p. 2

- Matthews 2002, pp. 20–21

- Woods 2010, pp. 36–45

- Matthews 2002, pp. 33–37

- ^ Pruß 2004

- Woolley 1965, p. 9

- Marchesi, Gianni (2010). "The Sumerian King List and the Early History of Mesopotamia". M. G. Biga - M. Liverani (Eds.), ana turri gimilli: Studi dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer, S. J., da amici e allievi (Vicino Oriente - Quaderno 5; Roma): 231–248.

- Woods 2006

- "Ancient Irrigation". Archived from the original on 2019-05-03. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- Saggs, The Might, 24.

- Potts 1999, p. 318.

Notes

- This page will use Mesopotamia in its widest geographical and chronological sense.

- This page will use the Middle Chronology.

Bibliography

- Akkermans, Peter M.M.G.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (2003). The Archaeology of Syria. From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (ca. 16,000–300 BC). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79666-0.

- Bahrani, Z. (1998). "Conjuring Mesopotamia: Imaginative Geography and a World Past". In Meskell, L. (ed.). Archaeology under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. London: Routledge. pp. 159–174. ISBN 978-0-415-19655-0.

- Banning, E.B. (2011). "So Fair a House. Göbekli Tepe and the Identification of Temples in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of the Near East". Current Anthropology. 52 (5): 619–660. doi:10.1086/661207. S2CID 161719608.

- Braidwood, Robert J.; Howe, Bruce (1960). Prehistoric Investigations in Iraqi Kurdistan (PDF). Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization. Vol. 31. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 395172. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-07. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- Brinkman, J.A. (1977). "Appendix: Mesopotamian Chronology of the Historical Period". In Oppenheim, A.L. (ed.). Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 335–348. ISBN 0-226-63186-9.

- Canard, M. (2011). "al-ḎJazīra, Ḏjazīrat Aḳūr or Iḳlīm Aḳūr". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Leiden: Brill Online. OCLC 624382576.

- Crawford, Harriet E. W. (2004). Sumer and the Sumerians (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521533386.

- Deutscher, Guy (2007). Syntactic Change in Akkadian: The Evolution of Sentential Complementation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953222-3.

- Finkelstein, J.J. (1962). "Mesopotamia". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 21 (2): 73–92. doi:10.1086/371676. JSTOR 543884. S2CID 222432558.

- Foster, Benjamin R.; Polinger Foster, Karen (2009). Civilizations of Ancient Iraq. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13722-3.

- Gasche, H.; Armstrong, J.A.; Cole, S.W.; Gurzadyan, V.G. (1998). Dating the Fall of Babylon: a Reappraisal of Second-Millennium Chronology. Chicago: University of Ghent/Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. ISBN 1-885923-10-4.

- Hunt, Will (2010). Arbil, Iraq Discovery Could be Earliest Evidence of Humans in the Near East. Heritage Key. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- Kozłowski, Stefan Karol (1998). "M'lefaat: Early Neolithic Site in Northern Irak". Cahiers de l'Euphrate. 8: 179–273. OCLC 468390039.

- Kuhrt, A. (1997). Ancient Near East c. 3000–330 BC. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16763-9.

- Manning, S.W.; Kromer, B.; Kuniholm, P.I.; Newton, M.W. (2001). "Anatolian Tree Rings and a New Chronology for the East Mediterranean Bronze-Iron Ages". Science. 294 (5551): 2532–2535. Bibcode:2001Sci...294.2532M. doi:10.1126/science.1066112. PMID 11743159. S2CID 33497945.

- Matthews, Roger (2002). Secrets of the Dark Mound: Jemdet Nasr 1926–1928. Iraq Archaeological Reports. Vol. 6. Warminster: BSAI. ISBN 0-85668-735-9.

- Matthews, Roger (2003). The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: Theories and Approaches. Approaching the past. Milton Square: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25317-9.

- Miquel, A.; Brice, W.C.; Sourdel, D.; Aubin, J.; Holt, P.M.; Kelidar, A.; Blanc, H.; MacKenzie, D.N.; Pellat, Ch. (2011). "ʿIrāḳ". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Leiden: Brill Online. OCLC 624382576.

- Mohammadifar, Yaghoub; Motarjem, Abbass (2008). "Settlement Continuity in Kurdistan". Antiquity. 82 (317). ISSN 0003-598X.

- Moore, A.M.T.; Hillman, G.C.; Legge, A.J. (2000). Village on the Euphrates: From Foraging to Farming at Abu Hureyra. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510807-8.

- Muhesen, Sultan (2002). "The Earliest Paleolithic Occupation in Syria". In Akazawa, Takeru; Aoki, Kenichi; Bar-Yosef, Ofer (eds.). Neandertals and Modern Humans in Western Asia. New York: Kluwer. pp. 95–105. doi:10.1007/0-306-47153-1_7. ISBN 0-306-47153-1.

- Pollock, Susan (1999). Ancient Mesopotamia: The Eden That Never Was. Case Studies in Early Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57568-3.

- Potts, D.T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56496-4.

- Pruß, Alexander (2004), "Remarks on the Chronological Periods", in Lebeau, Marc; Sauvage, Martin (eds.), Atlas of Preclassical Upper Mesopotamia, Subartu, vol. 13, pp. 7–21, ISBN 2503991203

- Sagona, A.; Zimansky, P. (2009). Ancient Turkey. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-28916-0.

- Schmid, P.; Rentzel, Ph.; Renault-Miskovsky, J.; Muhesen, Sultan; Morel, Ph.; Le Tensorer, Jean Marie; Jagher, R. (1997). "Découvertes de Restes Humains dans les Niveaux Acheuléens de Nadaouiyeh Aïn Askar (El Kowm, Syrie Centrale)". Paléorient. 23 (1): 87–93. doi:10.3406/paleo.1997.4646.

- Schmidt, Klaus (2003). "The 2003 Campaign at Göbekli Tepe (Southeastern Turkey)" (PDF). Neo-Lithics. 2/03: 3–8. ISSN 1434-6990. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- Solecki, Ralph S. (1997). "Shanidar Cave". In Meyers, Eric M. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Ancient Near East. Vol. 5. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-19-506512-3.

- van de Mieroop, M. (2007). A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000–323 BC. Malden: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22552-2.

- Wilkinson, Tony J. (2000). "Regional Approaches to Mesopotamian Archaeology: the Contribution of Archaeological Surveys". Journal of Archaeological Research. 8 (3): 219–267. doi:10.1023/A:1009487620969. ISSN 1573-7756. S2CID 140771958.

- Woods, Christopher (2006). "Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian" (PDF). In Sanders, S.L. (ed.). Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 91–120. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-29. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- Woods, Christopher (2010). "The Earliest Mesopotamian Writing" (PDF). In Woods, Christopher (ed.). Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond. Oriental Institute Museum Publications. Vol. 32. Chicago: University of Chicago. pp. 33–50. ISBN 978-1-885923-76-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-08-26. Retrieved 2011-08-10.

- Woolley, C.L. (1965). The Sumerians. New York: W.W. Norton.

Further reading

- Joannès, Francis (2004). The Age of Empires: Mesopotamia in the First Millennium BC. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1755-8.

- Matthews, Roger (2000). The Early Prehistory of Mesopotamia: 500,000 to 4,500 BC. Subartu. Vol. 5. Turnhout: Brepols. ISBN 2-503-50729-8.

- Nissen, Hans J. (1988). The Early History of the Ancient Near East 9000–2000 B.C. London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-58656-1.

- Postgate, J.N. (1992). Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-11032-7.

- Saggs, H.W.F. (1990). Assyria: The Might that Was. London: Sidgwick and Johnson. ISBN 0-312-03511-X.

- Simpson, St. John (1997). "Mesopotamia from Alexander to the Rise of Islam". In Meyers, Eric M. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Ancient Near East. Vol. 3. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 484–487. ISBN 0-19-506512-3.

- Wencel, Maciej Mateusz (2017). "Radiocarbon Dating of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia: Results, Limitations, and Prospects". Radiocarbon. 59 (2): 635–645. Bibcode:2017Radcb..59..635W. doi:10.1017/RDC.2016.60. ISSN 0033-8222. S2CID 133337438.

| Ancient Mesopotamia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geography |

|  | ||||

| (Pre)history |

| |||||

| Languages | ||||||

| Culture/society |

| |||||

| Archaeology | ||||||

| Religion | ||||||

| Academia | ||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Prehistoric Asia | |

|---|---|

| Paleolithic | |

| Neolithic | |

| Chalcolithic | |

| Bronze Age | |

| Rulers of the ancient Near East | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chronology of the Neolithic period | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Pottery Neolithic Pottery Neolithic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||