| Revision as of 14:48, 12 November 2024 edit2607:fea8:4a5c:fb40:98a6:ebb1:89ef:ae44 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit |

Latest revision as of 15:14, 20 December 2024 edit undo2607:fea8:4a5c:fb40:38af:6185:4427:420c (talk)No edit summaryTag: Disambiguation links added |

| (42 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

|

{{Short description|Legendary empress of Japan from 201 to 269}} |

|

{{Short description|Legendary empress of Japan from 201 to 269}} |

|

|

{{Multiple issues| |

|

|

{{Expert needed|1=History|reason=Dispute over lineage and legendary narrative|date=December 2024}} |

|

|

{{Disputed|date=December 2024}} |

|

|

{{Unreliable sources|date=December 2024}} |

|

|

}} |

|

{{Infobox royalty |

|

{{Infobox royalty |

|

| name = Empress Jingū<br>{{nobold|{{lang|ja|神功皇后}}}} |

|

| name = Empress Jingū<br>{{nobold|{{lang|ja|神功皇后}}}} |

| Line 23: |

Line 28: |

|

}} |

|

}} |

|

|

|

|

|

{{Nihongo|'''Empress Jingū'''|神功皇后|Jingū-kōgō}}{{efn|Occasionally she is given the title 天皇 ''tennō'', signifying an empress-regnant, as opposed to ''kōgō'', which indicates an empress-consort.}} was a ]ary Japanese empress of Korean (Buyeo) ethnicity<ref>Korean Impact on Japanese Culture: Japan's Hidden History by Jon Etta Hastings Carter Covell, Alan Carter Covell pg.13</ref>who ruled as a regent following her ]'s death in 200 AD.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://ehime-jinjacyo.jp/?p=1154 |title=The Shinto Shrine Agency of Ehime Prefecture |access-date=August 27, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131226114118/http://ehime-jinjacyo.jp/?p=1154 |archive-date=2013-12-26 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite EB1911 |wstitle=Jingo |volume=15 |page=416}}</ref> Both the {{Lang|ja-latn|Kojiki}} and the {{Lang|ja-latn|Nihon Shoki}} (collectively known as the ''Kiki'') record events that took place during Jingū's alleged lifetime. Legends say that after seeking revenge on the people who murdered her husband, she then turned her attention to a "promised land". Jingū is thus considered to be a controversial monarch by historians in terms of her altered/fabricated invasion of the ].<!--This does not need a source as the info is in the body of the article--> This was in turn used as justification for ] during the ]. The records state that Jingū gave birth to a baby boy whom she named ''Homutawake'' three years after he was conceived by her late husband. |

|

{{Nihongo|'''Empress Jingū'''|神功皇后|Jingū-kōgō}}{{efn|Occasionally she is given the title 天皇 ''tennō'', signifying an empress-regnant, as opposed to ''kōgō'', which indicates an empress-consort.}} was a ] Japanese empress suspected to be of ] origin<ref>Korean Impact on Japanese Culture: Japan's Hidden History by Jon Etta Hastings Carter Covell, Alan Carter Covell pg.12</ref> who ruled as a regent following her ]'s death in 200 AD.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://ehime-jinjacyo.jp/?p=1154 |title=The Shinto Shrine Agency of Ehime Prefecture |access-date=August 27, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131226114118/http://ehime-jinjacyo.jp/?p=1154 |archive-date=2013-12-26 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite EB1911 |wstitle=Jingo |volume=15 |page=416}}</ref> Both the {{Lang|ja-latn|Kojiki}} and the {{Lang|ja-latn|Nihon Shoki}} (collectively known as the ''Kiki'') record events that took place during Jingū's alleged lifetime. Legends say that after seeking revenge on the people who murdered her husband, she then turned her attention to a "promised land." Jingū is thus considered to be a controversial monarch by historians in terms of her alleged invasion of the ].<!--This does not need a source as the info is in the body of the article--> This was in turn possibly used as justification for ] during the ]. The records state that Jingū gave birth to a baby boy whom she named ''Homutawake'' three years after he was conceived by her late husband. |

|

|

|

|

|

Jingū's reign is conventionally considered to have been from 201 to 269 AD, and was considered to be the 15th ]ese ] until the Meiji period.{{efn|According to the traditional order of succession, hence her alternate title {{Nihongo||神功天皇|Jingū tennō}}}} Modern historians have come to the conclusion that the name "Jingū" was used by later generations to describe this legendary Empress. It has also been proposed that Jingū actually reigned later than she is attested. While the location of Jingū's grave (if any) is unknown, she is traditionally venerated at a ] and at a shrine. It is accepted today that Empress Jingū reigned as a regent until her son became ] upon her death. She was additionally the last de facto ruler of the ].{{efn|In terms of rulers she is traditionally listed as the last of the Yayoi period. This period itself though, is traditionally dated from 300 BC to 300 AD.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/yayoi.html |title=Yayoi Culture |first=Charles T. |last=Keally |date=2006-06-03 |work=Japanese Archaeology |publisher=Charles T. Keally |access-date=2010-03-19}}</ref>}} |

|

Jingū's reign is conventionally considered to have been from 201 to 269 AD, and was considered to be the 15th ]ese ] until the Meiji period.{{efn|According to the traditional order of succession, hence her alternate title {{Nihongo||神功天皇|Jingū tennō}}}} Modern historians have come to the conclusion that the name "Jingū" was used by later generations to describe this legendary Empress. It has also been proposed that Jingū actually reigned later than she is attested. While the location of Jingū's grave (if any) is unknown, she is traditionally venerated at a ] and at a shrine. It is accepted today that Empress Jingū reigned as a regent until her son became ] upon her death. She was additionally the last de facto ruler of the ].{{efn|In terms of rulers she is traditionally listed as the last of the Yayoi period. This period itself though, is traditionally dated from 300 BC to 300 AD.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/yayoi.html |title=Yayoi Culture |first=Charles T. |last=Keally |date=2006-06-03 |work=Japanese Archaeology |publisher=Charles T. Keally |access-date=2010-03-19}}</ref>}} |

| Line 29: |

Line 34: |

|

|

|

|

|

==Legendary narrative== |

|

==Legendary narrative== |

|

|

{{Tone|section|date=December 2024}} |

|

|

|

|

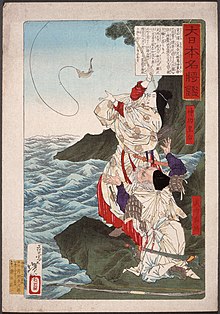

] (1880)]] |

|

] (1880)]] |

|

] Fishing at Chikuzen]] |

|

] Fishing at Chikuzen]] |

| Line 34: |

Line 41: |

|

The Japanese have traditionally accepted this regent's historical existence, and a mausoleum (misasagi) for Jingū is currently maintained. The following information available is taken from the ] {{Lang|ja-latn|]}} and {{Lang|ja-latn|]}}, which are collectively known as {{Nihongo|''Kiki''|記紀}} or ''Japanese chronicles''. These chronicles include legends and myths, as well as potential historical facts that have since been exaggerated and/or distorted over time. According to extrapolations from mythology, Jingū's birth name was {{nihongo|''Okinaga-Tarashi''|息長帯比売}}, she was born sometime in 169 AD.<ref name="birth"/><ref name="name">{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/ahistoryjapanes00kikugoog|quote=Okinaga-Tarashi.|title=''A History of the Japanese People from the Earliest Times to the end of the Meiji Era''|author=Brinkley, Frank|publisher=Encyclopaedia Britannica Company|year=1915|pages=–89|author-link=Francis Brinkley}}</ref><ref name="Rambelli">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NexdDwAAQBAJ&q=Empress+Jing%C5%AB+169&pg=PT259|title=The Sea and the Sacred in Japan: Aspects of Maritime Religion|author=Rambelli, Fabio|publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing|year=2018|author-link=Fabio Rambelli|isbn=9781350062870}}</ref> Her father was named {{Nihongo|Okinaganosukune|息長宿禰王}}, and her mother {{Nihongo|Kazurakinotakanuka-hime|葛城高額媛}}. Her mother is noted for being a descendant of {{Nihongo|]|天日槍}}, a legendary prince of Korea (despite the fact that Amenohiboko is believed to have moved to Japan between the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, at least 100 years after the extrapolated birth year of his granddaughter Jingū<ref>], Vol.6 "天日槍對曰 僕新羅國主之子也 然聞日本國有聖皇 則以己國授弟知古而化歸之"</ref>).<ref name="Allen">{{Cite journal|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171015045008/http://www.academia.edu/3335635/Empress_Jing%C5%AB_a_shamaness_ruler_in_early_Japan|archive-date=2017-10-15|url-status=live|url=https://www.academia.edu/3335635|title=Empress Jingū: a shamaness ruler in early Japan|author=Chizuko Allen|journal=Japan Forum|year=2003|volume=15|issue=1|pages=81–98|doi=10.1080/0955580032000077748|s2cid=143770151|access-date=November 6, 2019}}</ref> At some point in time she wed Tarashinakahiko (or Tarashinakatsuhiko), who would later be known as ] and bore him one child under a now disputed set of events. Jingū would serve as "Empress consort" during Chūai's reign until his death in 200 AD. |

|

The Japanese have traditionally accepted this regent's historical existence, and a mausoleum (misasagi) for Jingū is currently maintained. The following information available is taken from the ] {{Lang|ja-latn|]}} and {{Lang|ja-latn|]}}, which are collectively known as {{Nihongo|''Kiki''|記紀}} or ''Japanese chronicles''. These chronicles include legends and myths, as well as potential historical facts that have since been exaggerated and/or distorted over time. According to extrapolations from mythology, Jingū's birth name was {{nihongo|''Okinaga-Tarashi''|息長帯比売}}, she was born sometime in 169 AD.<ref name="birth"/><ref name="name">{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/ahistoryjapanes00kikugoog|quote=Okinaga-Tarashi.|title=''A History of the Japanese People from the Earliest Times to the end of the Meiji Era''|author=Brinkley, Frank|publisher=Encyclopaedia Britannica Company|year=1915|pages=–89|author-link=Francis Brinkley}}</ref><ref name="Rambelli">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NexdDwAAQBAJ&q=Empress+Jing%C5%AB+169&pg=PT259|title=The Sea and the Sacred in Japan: Aspects of Maritime Religion|author=Rambelli, Fabio|publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing|year=2018|author-link=Fabio Rambelli|isbn=9781350062870}}</ref> Her father was named {{Nihongo|Okinaganosukune|息長宿禰王}}, and her mother {{Nihongo|Kazurakinotakanuka-hime|葛城高額媛}}. Her mother is noted for being a descendant of {{Nihongo|]|天日槍}}, a legendary prince of Korea (despite the fact that Amenohiboko is believed to have moved to Japan between the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, at least 100 years after the extrapolated birth year of his granddaughter Jingū<ref>], Vol.6 "天日槍對曰 僕新羅國主之子也 然聞日本國有聖皇 則以己國授弟知古而化歸之"</ref>).<ref name="Allen">{{Cite journal|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171015045008/http://www.academia.edu/3335635/Empress_Jing%C5%AB_a_shamaness_ruler_in_early_Japan|archive-date=2017-10-15|url-status=live|url=https://www.academia.edu/3335635|title=Empress Jingū: a shamaness ruler in early Japan|author=Chizuko Allen|journal=Japan Forum|year=2003|volume=15|issue=1|pages=81–98|doi=10.1080/0955580032000077748|s2cid=143770151|access-date=November 6, 2019}}</ref> At some point in time she wed Tarashinakahiko (or Tarashinakatsuhiko), who would later be known as ] and bore him one child under a now disputed set of events. Jingū would serve as "Empress consort" during Chūai's reign until his death in 200 AD. |

|

|

|

|

|

] died in 200 AD having been killed directly or indirectly in battle by rebel forces. Okinagatarashi-hime no Mikoto then turned her rage on the rebels whom she vanquished in a fit of revenge.<ref name="name"/> She led an army in an invasion of a "promised land" (sometimes interpreted as lands on the ]), and returned to Japan victorious after three years.<ref name="NS9">{{Cite web |url=http://www.j-texts.com/jodai/shoki9.html |title=Nihon Shoki, Volume 9 |access-date=November 5, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140425133202/http://www.j-texts.com/jodai/shoki9.html |archive-date=2014-04-25 |url-status=live }}</ref> The Nihongi of 720 A.D. gives Jingu's route of conquest, beginning with Koryong (Taegu) and continuing southward, overrunning the Kaya League cities and pushing the resisting remnants up the eastern coast of Korea. The route followed is reasonable and militarily brilliant. However, in order to make Jingu a Japanese, the court histories needed to start Jingu from Kyushu and take her to Koryong and then backtrack southward.(In other words she passed peacefully over south Korean territory, and then reversed her route, fighting all the way.) |

|

] died in 200 AD, having been killed directly or indirectly in battle by rebel forces. Okinagatarashi-hime no Mikoto then turned her rage on the rebels whom she vanquished in a fit of revenge.<ref name="name"/> She led an army in an invasion of a "promised land" (sometimes interpreted as lands on the ]), and returned to Japan victorious after three years.<ref name="NS9">{{Cite web |url=http://www.j-texts.com/jodai/shoki9.html |title=Nihon Shoki, Volume 9 |access-date=November 5, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140425133202/http://www.j-texts.com/jodai/shoki9.html |archive-date=2014-04-25 |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] of 720 A.D. gives Jingu's route of conquest, beginning with Koryong (Taegu) and continuing southward, overrunning the ] League cities and pushing the resisting remnants up the eastern coast of ]. The route followed is reasonable and militarily brilliant. However, in order to revise history and make Jingu a Japanese, the court histories needed to start Jingu from Kyushu and take her to Koryong and then backtrack southward (in other words she passed peacefully over south Korean territory, and then reversed her route, fighting all the way).<ref>Korean Impact on Japanese Culture: Japan's Hidden History by Jon Etta Hastings Carter Covell, Alan Carter Covell pg.17</ref> |

|

|

|

|

An interesting little indication of Jingu's ancestral roots in the extreme north, near the mighty Yalu River, someway crept into the Nihongi and has been preserved. (Perhaps not being understood?) It goes as follows: When Jingu subjugated "the King of Silla," he promised to faithfully serve her as a vassal "until the River Arinarae" runs backward in its course. Aston, the Nihongi's translator, had no nationalistic ax to grind, and he considered this river to be the Yalu, which forms |

|

|

the western half of the present border of North Korea. Would Jingu, if she were indeed a native of Japan, have even heard of this river? Why should she consider an oath by this remote northern spot especially binding? The ”King of Silla" might have knowledge of this river in memories which the Eastern Buyeo had brought down to Kaya with them. The oath indicates that the king of the territory referred to as ”Silla" in later times (eighth century) and Jingu shared a common heritage.<ref>Korean Impact on Japanese Culture: Japan's Hidden History by Jon Etta Hastings Carter Covell, Alan Carter Covell pg.17</ref> While returning to Japan she was nearly shipwrecked but managed to survive thanks to praying to ], and she made the shrine to honor him.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |title=Watatsumi Shrine {{!}} 海神社 {{!}}Hyogo-ken, Kobe-shi |url=https://www.rodsshinto.com/28-108-01 |access-date=2023-04-06 |website=shintoshrines |language=en}}</ref> ] and ] and ] were both also made at the same time by the Empress.<ref name=":1" /> She then ascended the ] as Empress Jingū, and legend continues by saying that her son was conceived but unborn when Chūai died.<ref name=":0" /> |

|

An interesting little indication of Jingu's ancestral roots in the extreme north, near the mighty ], someway crept into the Nihongi and has been preserved; perhaps not being understood. It goes as follows: When Jingu subjugated "the King of ]," he promised to faithfully serve her as a vassal "until the "River Arinarae" runs backward in its course." ], the ]'s translator had no nationalistic ax to grind, and he considered this river to be the ], which forms the western half of the present border of North Korea. Would Jingu, if she were indeed a native of Japan, have even heard of this river?<ref>Korean Impact on Japanese Culture: Japan's Hidden History by Jon Etta Hastings Carter Covell, Alan Carter Covell pg.17</ref> Why should she consider an oath by this remote northern spot especially binding? The ”King of ]" might have knowledge of this river in memories which the Eastern ] had brought down to ] with them. The oath indicates that the king of the territory referred to as ”]" in later times (eighth century) and Jingu shared a common heritage.<ref>Korean Impact on Japanese Culture: Japan's Hidden History by Jon Etta Hastings Carter Covell, Alan Carter Covell pg.17</ref> While returning to Japan she was nearly shipwrecked but managed to survive thanks to praying to ], and she made the shrine to honor him.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |title=Watatsumi Shrine {{!}} 海神社 {{!}}Hyogo-ken, Kobe-shi |url=https://www.rodsshinto.com/28-108-01 |access-date=2023-04-06 |website=shintoshrines |language=en}}</ref> ] and ] and ] were both also made at the same time by the Empress.<ref name=":1" /> She then ascended the ] as Empress Jingū, and legend continues by saying that her son was conceived but unborn when Chūai died.<ref name=":0" /> |

|

|

|

|

|

According to a certain source Empress Jingu had sex with the god ] while pregnant with ] after he said from the womb that it was acceptable, and then Azumi no Isora gave her the ], and she later strapped a stone to her stomach to delay the birth of her son.<ref name=":023">{{Cite book |last=Rambelli |first=F |title=The Sea and The Sacred in Japan |publisher=Bloomsbury Academic Publishing |year=2018 |isbn=978-1350062870 |location=Camden |pages=}}</ref>{{rp|xxvii}}{{Refn|According to a certain source, Isora offered his navigational services in "exchange for a sexual relationship" with the empress.{{sfnp|Rambelli|2018|p=77}} Though "the motif of divine union between Jingu and a sea god is relatively uncommon", the notion that Azumi-no-isora obtained sexual favors from the empress is attested in shrine-foundation myth ({{interlanguage link|jisha engi|ja|寺社縁起|lt=''jisha engi''}}) document called the {{nihongo|''Rokugō kaizan Ninmmon daibosatsu hongi''|六郷開山仁聞大菩薩本紀}}.{{sfnp|Rambelli|2018|p=69}} Other shrines of the cult do not promote this idea. Isora carries out the task "without any sexual compensation" in the ''{{interlanguage link|Hachiman gudōkun|ja|八幡愚童訓|lt=''Hachiman gudōkun''}} attributed to a priest at the ].{{sfnp|Rambelli|2018|p=74}}|group="lower-alpha"}} After those three years she gave birth to a baby boy whom she named ''Homutawake''. |

|

According to a certain source Empress Jingu had sex with the god ] while pregnant with ] after he said from the womb that it was acceptable, and then Azumi no Isora gave her the ], and she later strapped a stone to her stomach to delay the birth of her son.<ref name=":023">{{Cite book |last=Rambelli |first=F |title=The Sea and The Sacred in Japan |publisher=Bloomsbury Academic Publishing |year=2018 |isbn=978-1350062870 |location=Camden |pages=}}</ref>{{rp|xxvii}}{{Refn|According to a certain source, Isora offered his navigational services in "exchange for a sexual relationship" with the empress.{{sfnp|Rambelli|2018|p=77}} Though "the motif of divine union between Jingu and a sea god is relatively uncommon", the notion that Azumi-no-isora obtained sexual favors from the empress is attested in shrine-foundation myth ({{interlanguage link|jisha engi|ja|寺社縁起|lt=''jisha engi''}}) document called the {{nihongo|''Rokugō kaizan Ninmmon daibosatsu hongi''|六郷開山仁聞大菩薩本紀}}.{{sfnp|Rambelli|2018|p=69}} Other shrines of the cult do not promote this idea. Isora carries out the task "without any sexual compensation" in the ''{{interlanguage link|Hachiman gudōkun|ja|八幡愚童訓|lt=''Hachiman gudōkun''}} attributed to a priest at the ].{{sfnp|Rambelli|2018|p=74}}|group="lower-alpha"}} After those three years she gave birth to a baby boy whom she named ''Homutawake''. |

| Line 47: |

Line 54: |

|

] |

|

] |

|

|

|

|

|

Empress consort Jingū is regarded by historians as a legendary figure as there is insufficient material available for further verification and study. The lack of this information has made her very existence open to debate. If Empress Jingū was an actual figure, investigations of her tomb suggest she may have been a regent in the late 4th century AD or late 5th century AD.<ref name="Kofun">{{cite web |author=Keally, Charles T. |title=Kofun Culture |url=http://www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/kofun.html |access-date=November 4, 2019 |work=www.t-net.ne.jp}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tmYYAgAAQBAJ&q=Empress|isbn = 9780810878723|title = Historical Dictionary of Japan to 1945|date = 7 November 2013|publisher = Scarecrow Press}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=May 2024}} |

|

Empress consort Jingū is regarded by historians as a legendary figure, as there is insufficient material available for further verification and study. The lack of this information has made her very existence open to debate. If Empress Jingū was an actual figure, investigations of her tomb suggest she may have been a regent in the late 4th century AD or late 5th century AD.<ref name="Kofun">{{cite web |author=Keally, Charles T. |title=Kofun Culture |url=http://www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/kofun.html |access-date=November 4, 2019 |work=www.t-net.ne.jp}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tmYYAgAAQBAJ&q=Empress|isbn = 9780810878723|title = Historical Dictionary of Japan to 1945|date = 7 November 2013|publisher = Scarecrow Press}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=May 2024}} |

|

|

|

|

|

There is no evidence to suggest that the title tennō was used during the time to which Jingū's regency has been assigned. It is certainly possible that she was a chieftain or local clan leader, and that the polity she ruled would have only encompassed a small portion of modern-day Japan. The name ''Jingū'' was more than likely assigned to her ] by later generations; during her lifetime she would have been called ''Okinaga-Tarashi'' respectively.<ref name="name" /> Empress Jingū was later removed from the imperial lineage during the reign of ] as a way of making sure the lineage remained unbroken. This occurred when examining the emperors of the ] and ] of the fourteenth century. Focus was given on who should be the "true" ancestors of those who occupied the throne.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=m34p1f93HogC&q=Jingu+removed+imperial+lineage&pg=PA22|title=From Sovereign to Symbol: An Age of Ritual Determinism in Fourteenth Century Japan|author=Conlan, Thomas|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2011|page=22|isbn=9780199778102}}</ref> |

|

There is no evidence to suggest that the title tennō was used during the time to which Jingū's regency has been assigned. It is certainly possible that she was a chieftain or local clan leader, and that the polity she ruled would have only encompassed a small portion of modern-day Japan. The name ''Jingū'' was more than likely assigned to her ] by later generations; during her lifetime she would have been called ''Okinaga-Tarashi'' respectively.<ref name="name" /> Empress Jingū was later removed from the imperial lineage during the reign of ] as a way of making sure the lineage remained unbroken. This occurred when examining the emperors of the ] and ] of the fourteenth century. Focus was given on who should be the "true" ancestors of those who occupied the throne.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=m34p1f93HogC&q=Jingu+removed+imperial+lineage&pg=PA22|title=From Sovereign to Symbol: An Age of Ritual Determinism in Fourteenth Century Japan|author=Conlan, Thomas|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2011|page=22|isbn=9780199778102}}</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

=== Gosashi kofun === |

|

=== Gosashi kofun === |

|

While the actual site of Jingū's ] is not known, this regent is traditionally venerated at a '']''-type Imperial tomb in ].<ref>{{citation | place = JP | publisher = Nara shikanko | url = http://narashikanko.jp/english/aria_map/map_pdf/39.pdf | title = Jingū's ''misasagi'' | at = lower right | type = map | access-date = January 7, 2008 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090124082216/http://narashikanko.jp/english/aria_map/map_pdf/39.pdf | archive-date = 2009-01-24 | url-status = dead }}.</ref> This Kofun is also known as the "Gosashi tomb", and is managed by the ]. The tomb was restricted from archaeology studies in 1976 as the tomb dates back to the founding of a central Japanese state under imperial rule. The Imperial Household Agency had also cited "tranquility and dignity" concerns in making their decision. Serious ethics concerns had been raised in 2000 after a massive archaeological hoax was exposed. Things changed in 2008 when Japan allowed limited access to Jingū's kofun to foreign archaeologists, who were able to determine that the tomb likely dated to the 4th century AD. The examination also discovered ] terracotta figures.<ref name="Kofun"/><ref name="NG"/><ref>]. (1959). ''The Imperial House of Japan,'' p. 424.</ref> Empress Jingū is also enshrined at ] in ], which was established in the 11th year of her reign (211 AD).<ref>{{cite web|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924111551/http://www.sumiyoshitaisha.net/outline/history.html|archive-date=September 24, 2015|url=http://www.sumiyoshitaisha.net/outline/history.html|title=歴史年表 (History of Sumiyoshi-taisha)|work=sumiyoshitaisha.net|access-date=November 11, 2019}}</ref> |

|

While the actual site of Jingū's ] is not known, this regent is traditionally venerated at a '']''-type Imperial tomb in ].<ref>{{citation | place = JP | publisher = Nara shikanko | url = http://narashikanko.jp/english/aria_map/map_pdf/39.pdf | title = Jingū's ''misasagi'' | at = lower right | type = map | access-date = January 7, 2008 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090124082216/http://narashikanko.jp/english/aria_map/map_pdf/39.pdf | archive-date = 2009-01-24 | url-status = dead }}.</ref> This kofun is also known as the "Gosashi tomb", and is managed by the ]. The tomb was restricted from archaeology studies in 1976 as the tomb dates back to the founding of a central Japanese state under imperial rule. The Imperial Household Agency had also cited "tranquility and dignity" concerns in making their decision. Serious ethics concerns had been raised in 2000 after a massive archaeological hoax was exposed. Things changed in 2008 when Japan allowed limited access to Jingū's kofun to foreign archaeologists, who were able to determine that the tomb likely dated to the 4th century AD. The examination also discovered ] terracotta figures.<ref name="Kofun"/><ref name="NG"/><ref>]. (1959). ''The Imperial House of Japan,'' p. 424.</ref> Empress Jingū is also enshrined at ] in ], which was established in the 11th year of her reign (211 AD).<ref>{{cite web|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924111551/http://www.sumiyoshitaisha.net/outline/history.html|archive-date=September 24, 2015|url=http://www.sumiyoshitaisha.net/outline/history.html|title=歴史年表 (History of Sumiyoshi-taisha)|work=sumiyoshitaisha.net|access-date=November 11, 2019}}</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

==Controversy== |

|

==Controversy== |

| Line 65: |

Line 72: |

|

]]] |

|

]]] |

|

|

|

|

|

Both the {{Lang|ja-latn|]}} and the {{Lang|ja-latn|]}} give accounts of how Okinaga-Tarashi (Jingū) led an army to invade a "promised land" (sometimes interpreted as lands on the ]).<ref name="Rambelli" /><ref name="NS9" /> She then returned to Japan victorious after three years of conquest where she was proclaimed as Empress. The second volume of the {{Lang|ja-latn|]}} (中巻 or "Nakatsumaki") states that the Korean kingdom of ] (百済 or "Kudara") paid tribute to Japan under "Tribute from Korea".<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/kj/kj117.htm|title=|author=Chamberlain, Basil Hall.|year=1920}}</ref> The {{Lang|ja-latn|Nihon Shoki}} states that Jingū conquered a region in southern Korea in the 3rd century AD naming it "Mimana".<ref name="Seth">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Qe4PoOd89XIC&q=empress&pg=PA31|title=A Concise History of Korea: From the Neolithic Period Through the Nineteenth Century|author=Seth, Michael J.|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield|year=2006|page=31|isbn=9780742540057}}</ref><ref name="Rurarz89">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=O6W6uQEACAAJ&q=Historia+Korei|title=Historia Korei|author=Joanna Rurarz|publisher=Wydawnictwo Akademickie Dialog|language=pl|year=2014|page=89|isbn=9788363778866}}</ref> One of the main proponents of this theory was Japanese scholar Suematsu Yasukazu, who in 1949 proposed that Mimana was a Japanese colony on the Korean peninsula that existed from the 3rd until the 6th century.<ref name="Rurarz89" /> The Chinese '']'' of the ] also allegedly notes the Japanese presence in the Korean Peninsula, while the '']'' says that Japan provided military support to Baekje and Silla.<ref name="sui"> ]: 隋書 東夷伝 第81巻列伝46 : 新羅、百濟皆以倭為大國,多珍物,並敬仰之,恆通使往來.</ref> |

|

Both the {{Lang|ja-latn|]}} and the {{Lang|ja-latn|]}} give accounts of how Okinaga-Tarashi (Jingū) led an army to invade a "promised land" (sometimes interpreted as lands on the ]).<ref name="Rambelli" /><ref name="NS9" /> She then returned to Japan victorious after three years of conquest where she was proclaimed as Empress. But all of that is known to be revised history of early royalties of Japan, the primary purpose of these two history books was to give the new Fujiwara dynasty a credible family tree.<ref>Korean Impact on Japanese Culture: Japan's Hidden History by Jon Etta Hastings Carter Covell, Alan Carter Covell pg.111</ref> Unlike the {{Lang|ja-latn|]}}, which attempted no dates, the {{Lang|ja-latn|]}} does date events. Its chronology is unreliable until the fifth century; most events in the fourth century were placed 120 years too early, when compared with |

|

|

continental histories.<ref>Korean Impact on Japanese Culture: Japan's Hidden History by Jon Etta Hastings Carter Covell, Alan Carter Covell pg.111</ref> Before the fourth century, the ]’s dates are not reliable at all. For example, Japan's first dozen emperors are given an average |

|

|

of over a century of life, when the lifespan for Japanese a millennium later was about twenty-seven.<ref>Korean Impact on Japanese Culture: Japan's Hidden History by Jon Etta Hastings Carter Covell, Alan Carter Covell pg.111</ref> The second volume of the {{Lang|ja-latn|]}} (中巻 or "Nakatsumaki") states that the Korean kingdom of ] (百済 or "Kudara") paid tribute to Japan under "Tribute from Korea".<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/kj/kj117.htm|title=|author=Chamberlain, Basil Hall.|year=1920}}</ref>This is based on ]'s claim that the ] was a tribute paid to Jinmu, when in actuality the translation of the scriptures on the sword itself clearly indicates that the sword was a gift given by the prince of ] to his tributary/vessel state; Wei.<ref>Korean Impact on Japanese Culture: Japan's Hidden History by Jon Etta Hastings Carter Covell, Alan Carter Covell pg.22</ref> The {{Lang|ja-latn|Nihon Shoki}} states that Jingū conquered a region in southern Korea in the 3rd century AD naming it "Mimana".<ref name="Seth">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Qe4PoOd89XIC&q=empress&pg=PA31|title=A Concise History of Korea: From the Neolithic Period Through the Nineteenth Century|author=Seth, Michael J.|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield|year=2006|page=31|isbn=9780742540057}}</ref><ref name="Rurarz89">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=O6W6uQEACAAJ&q=Historia+Korei|title=Historia Korei|author=Joanna Rurarz|publisher=Wydawnictwo Akademickie Dialog|language=pl|year=2014|page=89|isbn=9788363778866}}</ref> One of the main proponents of this theory was Japanese scholar Suematsu Yasukazu, who in 1949 proposed that Mimana was a Japanese colony on the Korean peninsula that existed from the 3rd until the 6th century.<ref name="Rurarz89" /> The Chinese '']'' of the ] also allegedly notes the Japanese presence in the Korean Peninsula, while the '']'' says that Japan provided military support to Baekje and Silla.<ref name="sui"> ]: 隋書 東夷伝 第81巻列伝46 : 新羅、百濟皆以倭為大國,多珍物,並敬仰之,恆通使往來.</ref> |

|

|

|

|

|

In 1883, a memorial ] for the tomb of King ] (374 – 413) of ] was discovered and hence named the ]. An issue arose though, when the inscriptions describing events during the king's reign were found to be in bad condition with portions illegible.<ref name="Rawski">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6p1NCgAAQBAJ&q=Gwanggaeto+Stele+1883&pg=PA243|title=Early Modern China and Northeast Asia: Cross-Border Perspectives|author=Rawski, Evelyn S.|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2015|pages=243–244|author-link=Evelyn S. Rawski|isbn=9781316300350}}</ref> At the center of the disagreement is the "sinmyo passage" of year 391 as it can be interpreted in multiple ways. Korean scholars maintain that it states the Goguryeo subjugated Baekje and Silla, while Japanese scholars have traditionally interpreted that ] had at one time subjugated Baekje and Silla. The stele soon caught the interest of the ], who obtained a ] copy from its member Kageaki Sakō in 1884. They particularly became intrigued over the passage describing the king's military campaigns for the ''sinmyo'' in 391 AD.<ref name=JXu>Xu, Jianxin. ''好太王碑拓本の研究 (An Investigation of Rubbings from the Stele of Haotai Wang)''. {{interlanguage link|Tokyodo Shuppan|ja|東京堂出版}}, 2006. {{ISBN|978-4-490-20569-5}}.</ref> Additional research was done by some officers in the Japanese army and navy, and the rubbed copy was later published in 1889.<ref name="Lee">Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Park Jinhoon; Yi Huyn-hae (2014), ''Korean History in Maps'', Cambridge University Press, p. 49, {{ISBN|1107098467}}</ref> The interpretation was made by Japanese scholars at the time that the "Wa" had occupied and controlled the Korean Peninsula. The legends of Empress Jingū's conquest of Korea could have then been used by Imperial Japan as reasoning for their ] in 1910 as "restoring" unity between the two countries. As it was, imperialists had already used this historical claim to justify expansion into the Korean Peninsula.<ref name="Seth"/> |

|

In 1883, a memorial ] for the tomb of King ] (374 – 413) of ] was discovered and hence named the ]. An issue arose though, when the inscriptions describing events during the king's reign were found to be in bad condition with portions illegible.<ref name="Rawski">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6p1NCgAAQBAJ&q=Gwanggaeto+Stele+1883&pg=PA243|title=Early Modern China and Northeast Asia: Cross-Border Perspectives|author=Rawski, Evelyn S.|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2015|pages=243–244|author-link=Evelyn S. Rawski|isbn=9781316300350}}</ref> At the center of the disagreement is the "sinmyo passage" of year 391 as it can be interpreted in multiple ways. Korean scholars maintain that it states the Goguryeo subjugated Baekje and Silla, while Japanese scholars have traditionally interpreted that ] had at one time subjugated Baekje and Silla. The stele soon caught the interest of the ], who obtained a ] copy from its member Kageaki Sakō in 1884. They particularly became intrigued over the passage describing the king's military campaigns for the ''sinmyo'' in 391 AD.<ref name=JXu>Xu, Jianxin. ''好太王碑拓本の研究 (An Investigation of Rubbings from the Stele of Haotai Wang)''. {{interlanguage link|Tokyodo Shuppan|ja|東京堂出版}}, 2006. {{ISBN|978-4-490-20569-5}}.</ref> Additional research was done by some officers in the Japanese army and navy, and the rubbed copy was later published in 1889.<ref name="Lee">Injae, Lee; Miller, Owen; Park Jinhoon; Yi Huyn-hae (2014), ''Korean History in Maps'', Cambridge University Press, p. 49, {{ISBN|1107098467}}</ref> The interpretation was made by Japanese scholars at the time that the "Wa" had occupied and controlled the Korean Peninsula. The legends of Empress Jingū's conquest of Korea could have then been used by Imperial Japan as reasoning for their ] in 1910 as "restoring" unity between the two countries. As it was, imperialists had already used this historical claim to justify expansion into the Korean Peninsula.<ref name="Seth"/> |

Jingū's reign is conventionally considered to have been from 201 to 269 AD, and was considered to be the 15th Japanese imperial ruler until the Meiji period. Modern historians have come to the conclusion that the name "Jingū" was used by later generations to describe this legendary Empress. It has also been proposed that Jingū actually reigned later than she is attested. While the location of Jingū's grave (if any) is unknown, she is traditionally venerated at a kofun and at a shrine. It is accepted today that Empress Jingū reigned as a regent until her son became Emperor Ōjin upon her death. She was additionally the last de facto ruler of the Yayoi period.

The Japanese have traditionally accepted this regent's historical existence, and a mausoleum (misasagi) for Jingū is currently maintained. The following information available is taken from the pseudo-historical Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, which are collectively known as Kiki (記紀) or Japanese chronicles. These chronicles include legends and myths, as well as potential historical facts that have since been exaggerated and/or distorted over time. According to extrapolations from mythology, Jingū's birth name was Okinaga-Tarashi (息長帯比売), she was born sometime in 169 AD. Her father was named Okinaganosukune (息長宿禰王), and her mother Kazurakinotakanuka-hime (葛城高額媛). Her mother is noted for being a descendant of Amenohiboko (天日槍), a legendary prince of Korea (despite the fact that Amenohiboko is believed to have moved to Japan between the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, at least 100 years after the extrapolated birth year of his granddaughter Jingū). At some point in time she wed Tarashinakahiko (or Tarashinakatsuhiko), who would later be known as Emperor Chūai and bore him one child under a now disputed set of events. Jingū would serve as "Empress consort" during Chūai's reign until his death in 200 AD.

An interesting little indication of Jingu's ancestral roots in the extreme north, near the mighty Yalu River, someway crept into the Nihongi and has been preserved; perhaps not being understood. It goes as follows: When Jingu subjugated "the King of Silla," he promised to faithfully serve her as a vassal "until the "River Arinarae" runs backward in its course." William George Aston, the Nihongi's translator had no nationalistic ax to grind, and he considered this river to be the Yalu, which forms the western half of the present border of North Korea. Would Jingu, if she were indeed a native of Japan, have even heard of this river? Why should she consider an oath by this remote northern spot especially binding? The ”King of Silla" might have knowledge of this river in memories which the Eastern Buyeo had brought down to Gaya with them. The oath indicates that the king of the territory referred to as ”Silla" in later times (eighth century) and Jingu shared a common heritage. While returning to Japan she was nearly shipwrecked but managed to survive thanks to praying to Watatsumi, and she made the shrine to honor him. Ikasuri Shrine and Ikuta Shrine and Watatsumi Shrine were both also made at the same time by the Empress. She then ascended the Chrysanthemum Throne as Empress Jingū, and legend continues by saying that her son was conceived but unborn when Chūai died.

Empress Jingū was the de facto ruler until her death in 269 at the age of 100. The modern traditional view is that Chūai's son (Homutawake) became the next Emperor after Jingū acted as a regent. She would have been de facto ruler in the interim.

Empress consort Jingū is regarded by historians as a legendary figure, as there is insufficient material available for further verification and study. The lack of this information has made her very existence open to debate. If Empress Jingū was an actual figure, investigations of her tomb suggest she may have been a regent in the late 4th century AD or late 5th century AD.

There is no evidence to suggest that the title tennō was used during the time to which Jingū's regency has been assigned. It is certainly possible that she was a chieftain or local clan leader, and that the polity she ruled would have only encompassed a small portion of modern-day Japan. The name Jingū was more than likely assigned to her posthumously by later generations; during her lifetime she would have been called Okinaga-Tarashi respectively. Empress Jingū was later removed from the imperial lineage during the reign of Emperor Meiji as a way of making sure the lineage remained unbroken. This occurred when examining the emperors of the Northern Court and Southern Court of the fourteenth century. Focus was given on who should be the "true" ancestors of those who occupied the throne.

Jingū's identity has since been questioned by medieval and modern scholars whom have put forward different theories. Kitabatake Chikafusa (1293–1354) and Arai Hakuseki (1657–1725) asserted that she was actually the shaman-queen Himiko. The kiki does not include any mentions of Queen Himiko, and the circumstances under which these books were written is a matter of unending debate. Even if such a person was known to the authors of the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, they may have intentionally decided not to include her. However, they do include imperial-family shamans identified with her which include Jingū. Modern scholars such as Naitō Torajirō have stated that Jingū was actually Yamatohime-no-mikoto and that Wa armies obtained control of southern Korea. Yamatohime-no-Mikoto supposedly founded the Ise Shrine in tribute to the sun-goddess Amaterasu. While historian Higo Kazuo suggested that she is a daughter of Emperor Kōrei (Yamatototohimomosohime-no-Mikoto).

The main issue with an invasion scenario is a lack of evidence of Jingū's rule in Korea, or the existence of Jingū as an actual historical figure. This suggests that the accounts given are either fictional or an inaccurate/misleading account of events that occurred. According to the book "From Paekchae Korea to the Origin of Yamato Japan", the Japanese had misinterpreted the Gwanggaeto Stele. The Stele was a tribute to a Korean king, but because of a lack of correct punctuation, the writing can be translated in 4 different ways. This same Stele can also be interpreted as saying Korea crossed the strait and forced Japan into subjugation, depending on where the sentence is punctuated. An investigation done by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2006 suggested that the inscription could also be interpreted as "Silla and Baekje were dependent states of Yamato Japan."

The imperialist reasoning for occupation eventually led to an emotional repulsion from Jingu after World War II had ended as she had symbolized Japan's nationalistic foreign policy. Historian Chizuko Allen notes that while these feelings are understandable, they are not academically justifiable. The overall popularity of the Jingū theory has been declining since the 1970s due to concerns raised about available evidence.

Excluding the legendary Empress Jingū, there were eight reigning empresses and their successors were most often selected from amongst the males of the paternal Imperial bloodline, which is why some conservative scholars argue that the women's reigns were temporary and that male-only succession tradition must be maintained in the 21st century.

Woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, c. 1843-44

Woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, c. 1843-44