| Revision as of 18:09, 27 May 2007 editEgyegy~enwiki (talk | contribs)1,994 edits rv vandalism of a quote← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:58, 16 December 2024 edit undoBD2412 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, IP block exemptions, Administrators2,449,295 editsm Clean up spacing around commas and other punctuation fixes, replaced: ,M → , MTag: AWB | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Ethnic group}} | |||

| {{otheruses4|the Egyptians, a North African ethnic group|the ethnic group in the Balkans|Egyptians (Balkans)}} | |||

| {{about|the contemporary Nile Valley ethnic group|other uses|Egyptian (disambiguation)|information on the population of Egypt|Demographics of Egypt}} | |||

| {{Ethnic group | |||

| {{Pp-pc}}{{Infobox ethnic group | |||

| |group = Egyptians<br>(مَصريين Ma{{Unicode|ṣ}}reyyīn)<br>({{Coptic|ⲛⲓⲣⲉⲙ'ⲛⲭⲏⲙⲓ}} ni.Ramenkīmi) | |||

| | group = Egyptians | |||

| |image = ]<div style="background-color:#fee8ab"><small><small>] • Prince Rahotep of the ] • ] • ] • ] • ] • ] • ] • ] • ]</small></small> | |||

| | image = File:Map of the Egyptian Diaspora in the World.svg | |||

| |population = 76.4 million (2006)<ref name="Factbook">Egypt. . 2006.</ref> plus 2.7 million in the ] (2004)<ref name="Egypt Today">Moll, Yasmin. . ''Egypt Today''. August 2004.</ref> | |||

| | population = 120 million (2017)<ref name="BBC News Arabic">{{Cite news|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/arabic/middleeast-41453757|title=مصر في المركز الـ13 عالميا في التعداد السكاني|date=2017-09-30|work=BBC News Arabic|access-date=2018-09-01|language=en-GB}}</ref> | |||

| |region1 = {{flagcountry|Egypt}} | |||

| | popplace = '''{{flagcountry|Egypt}}'''<br />116,538,258<br>(2024 estimate)<ref>https://worldpopulationreview.com/ {{Bare URL inline|date=August 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |pop1= 76.4 million | |||

| | region1 = | |||

| |region2={{flagcountry|Saudi Arabia}} | |||

| | pop1 = | |||

| |pop2=900,000 (2004) | |||

| | ref1 = | |||

| |ref2={{lower|<ref name="UN">Kapiszewski, Andrzej. . May 22, 2006.</ref>}} | |||

| | |

| region2 = {{flagcountry|Saudi Arabia}} | ||

| | pop2 = 2,900,000 | |||

| |pop3= 333,000 (1999) | |||

| | ref2 = <ref name="CAPMAS">{{cite web|url=http://www.egyptindependent.com/9-5-million-egyptians-live-abroad-mostly-saudi-arabia-jordan/|title=9.5 million Egyptians live abroad, mostly in Saudi Arabia and Jordan|publisher=Egypt Independent|date=1 October 2017|access-date=3 January 2018|website=egyptindependent.com|archive-date=3 January 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180103193413/http://www.egyptindependent.com/9-5-million-egyptians-live-abroad-mostly-saudi-arabia-jordan/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |ref3={{lower|<ref name="Wahba">Wahba, Jackline. . February 2003.</ref>}} | |||

| | |

| region3 = {{flagcountry|United States}} | ||

| | ref3 = <ref name="goevcensus">{{Citation|url=https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_15_1YR_B04006&prodType=table=table|title=2015 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates|access-date=2018-10-13|archive-url=https://archive.today/20200214061451/https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_15_1YR_B04006&prodType=table=table|archive-date=2020-02-14|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| |pop4=318,000 (2000) | |||

| | |

| pop3 = 1,000,000–1,500,000<ref>↑ Talani, Leila S. Out of Egypt. University of California, Los Angeles. 2005. | ||

| https://escholarship.org/uc/item/84t8q4p1 {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200328235526/https://escholarship.org/uc/item/84t8q4p1 |date=2020-03-28 }}</ref> | |||

| |region5={{flagcountry|Jordan}} | |||

| | region4 = {{flagcountry|Libya}} | |||

| |pop5=227,000 (1999) | |||

| | pop4 = ~1,000,000<ref name="Wahba">Wahba, Jackline. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629081022/http://english.aljazeera.net/news/middleeast/2011/02/2011221222342232993.html |date=2011-06-29 }}. February 2011.</ref>–2,000,000 (pre-2011)<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Zohry |first=Ayman |date=9 January 2014 |title=Egypt's International Migration after the Revolution: Is There Any Change? |url=https://www.cairn.info/revue-confluences-mediterranee-2013-4-page-47.htm?ref=doi |journal=Cairn.info|volume=87 |issue=4 |pages=47–54 |doi=10.3917/come.087.0047 }}</ref> | |||

| |ref5={{lower|<ref name="Wahba" />}} | |||

| | ref4 = | |||

| |region6={{flagcountry|Kuwait}} | |||

| | region5 = {{flagcountry|UAE}} | |||

| |pop6=191,000 (1999) | |||

| | pop5 = 750,000 | |||

| |ref6={{lower|<ref name="Wahba" />}} | |||

| | ref5 = <ref name="CAPMAS"/> | |||

| |region7={{flagcountry|UAE}} | |||

| | region6 = {{flagcountry|Jordan}} | |||

| |pop7=140,000 (2002) | |||

| | pop6 = 600,000 | |||

| |ref7={{lower|<ref name="UN" />}} | |||

| | ref6 = <ref name="CAPMAS"/>–1,600,000<ref name="Arz">{{Cite web|url=https://www.ethnologue.com/language/arz/|title=Egyptian Arabic|publisher=Ethnologue|access-date=22 November 2023}}</ref> | |||

| |region8={{flagcountry|Canada}} | |||

| | region7 = {{flagcountry|Kuwait}} | |||

| |pop8=110,000 (2000) | |||

| | pop7 = 500,000 | |||

| |ref8={{lower|<ref></ref><ref></ref>}} | |||

| | ref7 = <ref name="CAPMAS"/> | |||

| |region9={{flagcountry|Italy}} | |||

| | region8 = {{flagcountry|Sudan}} | |||

| |pop9=90,000 (2000) | |||

| | pop8 = 500,000 | |||

| |ref9={{lower|<ref name="Talani" />}} | |||

| | ref8 = <ref name="CAPMAS1">{{cite web |url=http://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/ShowPDF.aspx?page_id=/Admin/Pages%20Files/2017109144221Egy.pdf |title=تسع ملايين و 471 ألف مصري مقيم بالخارج في نهاية 2016 |author=CAPMAS |language=ar |access-date=4 January 2018 |archive-date=19 May 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200519201159/https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/ShowPDF.aspx?page_id=%2FAdmin%2FPages%20Files%2F2017109144221Egy.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |region10={{flagcountry|Australia}} | |||

| | region9 = {{flagcountry|Qatar}} | |||

| |pop10=70,000 (2000) | |||

| | pop9 = 230,000 | |||

| |ref10={{lower|<ref name="Talani" />}} | |||

| | ref9 = <ref name="CAPMAS"/> | |||

| |region11={{flagcountry|Iraq}} | |||

| | region10 = {{flagcountry|Italy}} | |||

| |pop11=66,000 (1999) | |||

| | pop10 = 140,322 | |||

| |ref11={{lower|<ref name="Wahba" />}} | |||

| | ref10 = <ref>{{Cite web|title=Egiziani in Italia – statistiche e distribuzione per regione|url=https://www.tuttitalia.it/statistiche/cittadini-stranieri/egitto/|access-date=2021-06-21|website=Tuttitalia.it|language=it|archive-date=2021-06-24|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210624202922/https://www.tuttitalia.it/statistiche/cittadini-stranieri/egitto/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |region12={{flagcountry|Greece}} | |||

| | region11 = {{flagcountry|Canada}} | |||

| |pop12=60,000 (2000) | |||

| | pop11 = 73,250 | |||

| |ref12={{lower|<ref name="Talani" />}} | |||

| | ref11 = <ref name="Statistics Canada">{{cite web |url=http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/dt-td/Rp-eng.cfm?TABID=2&LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=1118296&GK=0&GRP=0&PID=105396&PRID=0&PTYPE=105277&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2013&THEME=95&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=&D1=0&D2=0&D3=0&D4=0&D5=0&D6=0 |title=2011 National Household Survey: Data tables |author=] |date=8 May 2013 |access-date=11 February 2014 |archive-date=24 December 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181224190955/https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/dt-td/Rp-eng.cfm?TABID=2&LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=1118296&GK=0&GRP=0&PID=105396&PRID=0&PTYPE=105277&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2013&THEME=95&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=&D1=0&D2=0&D3=0&D4=0&D5=0&D6=0%20 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |region13={{flagcountry|Germany}} | |||

| | region12 = {{flag|Israel}} | |||

| |pop13=40,000 (2000) | |||

| | pop12 = 57,500 | |||

| |ref13={{lower|<ref></ref>}} | |||

| | ref12 = <ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/shnaton/templ_shnaton_e.html?num_tab=st02_24x&CYear=2011 |title=Jews, by Country of Origin and Age |date=26 September 2011 |work=Statistical Abstract of Israel |publisher=] |language=en, he |access-date=31 July 2016 |archive-date=27 December 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181227042653/http://www.cbs.gov.il/reader/shnaton/templ_shnaton_e.html?num_tab=st02_24x&CYear=2011 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| |region14={{flagcountry|Netherlands}} | |||

| | region13 = {{flagcountry|Oman}} | |||

| |pop14=40,000 (2000) | |||

| | pop13 = 56,000 | |||

| |ref14={{lower|<ref name="Talani" />}} | |||

| | ref13 = <ref name="CAPMAS1"/> | |||

| |region15={{flagcountry|France}} | |||

| | region14 = {{flagcountry|Lebanon}} | |||

| |pop15=36,000 (2000) | |||

| | pop14 = 40,000 | |||

| |ref15={{lower|<ref name="Talani" />}} | |||

| | ref14 = <ref name="CAPMAS1"/> | |||

| |region16={{flagcountry|England}} | |||

| | region15 = {{flagcountry|South Africa}} | |||

| |pop16=35,000 (2000) | |||

| | pop15 = 40,000 | |||

| |ref16={{lower|<ref name="Talani" />}} | |||

| | ref15 = <ref name="CAPMAS1"/> | |||

| |region17={{flagcountry|Austria}} | |||

| | region16 = {{flagcountry|United Kingdom}} | |||

| |pop17=14,000 (2000) | |||

| | pop16 = 39,000 | |||

| |ref17={{lower|<ref name="Talani" />}} | |||

| | ref16 = <ref>{{ONSCoB2019|access-date=28 June 2020}}</ref> | |||

| |region18={{flagcountry|Switzerland}} | |||

| | region17 = {{flagcountry|Australia}} | |||

| |pop18=14,000 (2000) | |||

| | pop17 = 36,532 | |||

| |ref18={{lower|<ref name="Talani" />}} | |||

| | ref17 = <ref name="COB 2011">{{cite web|title=2011 QuickStats Country of Birth (Egypt)|url=http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/quickstat/4102_0|website=Censusdata.abs.gov.au|access-date=2013-05-22|archive-date=2017-08-29|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170829033638/http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2011/quickstat/4102_0|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |region19={{flagcountry|Spain}} | |||

| | region18 = {{flagcountry|Germany}} | |||

| |pop19=12,000 (2000) | |||

| | pop18 = 32,505 | |||

| |ref19={{lower|<ref name="Talani" />}} | |||

| | ref18 = <ref>{{Cite web|url=https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1221/umfrage/anzahl-der-auslaender-in-deutschland-nach-herkunftsland/|website=de.statista.com|title=Ausländer in Deutschland bis 2019: Herkunftsland|access-date=2021-07-14|archive-date=2017-01-30|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170130065833/https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1221/umfrage/anzahl-der-auslaender-in-deutschland-nach-herkunftsland/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |region20={{flagcountry|Israel}} | |||

| | region19 = {{flagcountry|Greece}} | |||

| |pop20=11,000 (2005) | |||

| | pop19 = 29,000 | |||

| |ref20={{lower|<ref>Saad, Rasha, Eric Silverman. . ''Al-Ahram Weekly''. 1-7 September 2005.</ref>}} | |||

| | ref19 = <ref name="auto">{{Cite web|url=https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination|title=Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination|date=February 10, 2014|website=migrationpolicy.org|access-date=August 8, 2020|archive-date=April 14, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414153852/https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |langs = ], ], ]/] | |||

| | region20 = {{flagcountry|Netherlands}} | |||

| |rels = Predominantly ] and ], with minorities of ], ], ], ], ], and ] | |||

| | pop20 = 28,400 | |||

| |related = ], ], ] | |||

| | ref20 = <ref name="statline">{{Cite web|url=http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?DM=SLNL&PA=37325&D1=0&D2=0&D3=0&D4=0&D5=a&D6=l&VW=T|title=CBS Statline|access-date=2020-10-04|archive-date=2018-01-17|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180117210150/http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?DM=SLNL&PA=37325&D1=0&D2=0&D3=0&D4=0&D5=a&D6=l&VW=T|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| }}The '''Egyptians''' (]: ''{{Unicode|rmṯnkm.t}}''; ]: {{Coptic|ⲛⲓⲣⲉⲙⲛⲭⲏⲙⲓ}} ''ni.ramenkīmi''; ]: مِصريّون ''{{Unicode|miṣriyūn}}''; ]: مَصريين ''{{Unicode|maṣreyyīn}}'') are a ]n ethnic group native to ]. Egyptian identity is rooted in the lower ], the small strip of cultivatable land stretching from the ] to the ] and enclosed by vast deserts. This unique geography has been the basis of the development of Egyptian society in ]. | |||

| | region21 = {{flagcountry|State of Palestine}} | |||

| | pop21 = 22,000 | |||

| | ref21 = <ref name="auto"/> | |||

| | region22 = {{flag|Switzerland}} | |||

| | pop22 = 15,939 | |||

| | ref22 = <ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/bevoelkerung/bevoelkerungsstand/bevoelkerung-nach-staatsangehoerigkeit/-geburtsland | title=Bevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit/Geburtsland }}</ref> | |||

| | region23 = {{flagcountry|France}} | |||

| | pop23 = 15,000 | |||

| | ref23 = <ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200621081018/https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/dossiers-pays/egypte/presentation-de-l-egypte/ |date=2020-06-21 }}. Diplomatie.gouv.fr. Retrieved on 2020-06-02.</ref> | |||

| | region24 = {{flagcountry|Iraq}} | |||

| | pop24 = 14,710 | |||

| | ref24 = <ref name="datosmacro">{{cite web|url=https://countryeconomy.com/demography/migration/emigration/egypt|title=Egypt – International emigrant stock|access-date=2022-11-07|archive-date=2022-11-07|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221107095819/https://countryeconomy.com/demography/migration/emigration/egypt|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | region25 = {{flagcountry|Sweden}} | |||

| | pop25 = 8,846 | |||

| | ref25 = <ref name="datosmacro"/> | |||

| | region26 = {{flagcountry|Yemen}} | |||

| | pop26 = 7,710 | |||

| | ref26 = <ref name="datosmacro"/> | |||

| | region27 = {{flag|South Sudan}} | |||

| | pop27 = 5,000 | |||

| | ref27 = <ref name="auto"/> | |||

| | region28 = {{flag|Brazil}} | |||

| | pop28 = 2,786 | |||

| | ref28 = <ref></ref> | |||

| | region29 = {{flag|Morocco}} | |||

| | pop29 = 2,000 | |||

| | ref29 = <ref name="auto"/> | |||

| | region30 = {{flag|Japan}} | |||

| | pop30 = 2,000 | |||

| | ref30 = <ref name="auto"/> | |||

| | region31 = {{flag|Tunisia}} | |||

| | pop31 = 1,000 | |||

| | ref31 = <ref name="auto"/> | |||

| | region32 = {{flag|Mali}} | |||

| | pop32 = 1,000 | |||

| | ref32 = <ref name="auto"/> | |||

| | langs = ]<br />] | |||

| | rels = {{plainlist| | |||

| * Majority: ] (predominantly ]) | |||

| * Minority: ] (predominantly ]) | |||

| }} | |||

| | related = ] | |||

| | native_name = | |||

| | native_name_lang = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Egyptians''' ({{langx|ar|مِصرِيُّون|translit=Miṣriyyūn}}, {{IPA|ar|mɪsˤrɪjˈjuːn|IPA}}; {{langx|arz|مَصرِيِّين|translit=Maṣriyyīn}}, {{IPA|arz|mɑsˤɾɪjˈjiːn|IPA}}; {{langx|cop|ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ|remenkhēmi}}) are an ]<ref>{{Cite book|last=Goldschmidt|first=Arthur|title=A Brief History of Egypt|publisher=Facts on File Inc|year=2008|isbn=978-0-8160-6672-8|pages=241|quote=People: Ethnic groups: Egyptians (98%), Bedouins, Berbers, Nubians, Greeks.}}</ref> native to the ] in ]. Egyptian identity is closely tied to ]. The population is concentrated in the ], a small strip of cultivable land stretching from the ] to the ] and enclosed by ] both to the ] and to the ]. This unique geography has been the basis of the ] since ]. | |||

| The Egyptian people have spoken only languages from the northern branch of the ] throughout their history, from old ] to today's vernacular ]. Their religion is predominantly ] with a ] minority and a significant proportion who follow native ] ].<ref name="Hoffman">Hoffman, Valerie J. ''Sufism, Mystics, and Saints in Modern Egypt''. University of South Carolina Press, 1995. </ref><ref>. May 2005. {{ar icon}}</ref> A large minority of Egyptians belong to the ], whose ], ], is the latest stage of the indigenous ]. | |||

| The daily language of the Egyptians is a continuum of the local ]; the most famous dialect is known as ] or ''Masri''. Additionally, a sizable minority of Egyptians living in Upper Egypt speak ]. Egyptians are predominantly adherents of ] with a small ] minority{{citation needed|date=May 2024}} and a significant proportion who follow native ] ].<ref name="Hoffman">Hoffman, Valerie J. ''Sufism, Mystics, and Saints in Modern Egypt''. University of South Carolina Press, 1995. {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050829032403/http://www.sc.edu/uscpress/1995/3055.html|date=August 29, 2005}}</ref> A considerable percentage of Egyptians are Coptic Christians who belong to the ], whose ], ], is the most recent stage of the ancient ] and is still used in ]s along with Egyptian Arabic. | |||

| ==Names of the Egyptians== | |||

| == Terminology == | |||

| *'''{{Unicode|Rmṯ}} (n) km.t''' – This is the native ] name of the people of the Nile Valley, literally 'People of ]' (i.e., Egypt). In ], it was often rendered simply as ''{{Unicode|Rmṯ}}'' or '(the) People.' The name is vocalized '''{{Unicode|ramenkīmi}}''' {{Coptic|ⲣⲉⲙⲛⲭⲏⲙⲓ}} in the ] stage of the language, meaning Egyptian (] dialect: '''{{Unicode|remnekēme}}''' {{Coptic|ⲣⲙⲛⲕⲏⲙⲉ}}) — and '''{{Unicode|ni.ramenkīmi}}''' {{Coptic|ⲛⲓⲣⲉⲙⲛⲭⲏⲙⲓ}} with the plural definite article, i.e., Egyptians, | |||

| Egyptians have received several names: | |||

| * 𓂋𓍿𓀂𓁐𓏥𓈖𓆎𓅓𓏏𓊖 ''rmṯ n Km.t'', the native ] name and ] of the Black Soil of the Nile Valley. In ]<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gri/9kemet.html | title=Chariot to Heaven, Kemet }}</ref> The name is vocalized as "''{{transliteration|egy|ræm/en/kā/mi}}''" {{Coptic|ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ}} in the late (Bohairic) ] stage of the language during the Greco-Roman era. ("''{{transliteration|egy|ni/ræm/en/kāmi}}''" {{Coptic|ⲛⲓⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ}} with the plural definite article, "Black Lands"). | |||

| *'''Copts''' ({{Unicode|qibṭ, qubṭ}} قبط) – Under Muslim rule, the Egyptians came to be known as ]s, a derivative of the Greek word {{Polytonic|Αἰγύπτιος}}, ''Aiguptios'' (Egyptian), from {{Polytonic|Αἰγύπτος}}, ''Aiguptos'' (Egypt). The Greek name in turn may be derived from the ] ''{{Unicode|ḥw.t-ka-ptḥ}}'', literally "Estate (or 'House') of ]", the name of the temple complex of the god ] at ]. After the vast majority of Egyptians converted from ] to ], the term became exclusively associated with ] and Egyptians who remained Christian, though references to native Muslims as Copts are attested until the ] period.<ref>C. Petry. "Copts in Late Medieval Egypt." ''Coptic Encylcopaedia''. 2:618 (1991).</ref> | |||

| * '''Egyptians''', from ] "{{lang|grc|Αἰγύπτιοι}}", ''{{transliteration|grc|Aiguptioi}}'', from "{{lang|grc|Αἴγυπτος}}", "''{{transliteration|grc|Aiguptos}}''". Prominent ] ], ], provided a ] stating that "''{{lang|grc|Αἴγυπτος}}''" had evolved as a ] from "''{{transliteration|grc|Aἰγαίου ὑπτίως}}''" ''{{transliteration|grc|Aegaeou huptiōs}}'', meaning "]". In ], the noun "Egyptians" appears in the 14th century, in ], as ''Egipcions''. | |||

| * ''']''' (قبط, ''{{transliteration|ar|qibṭ, qubṭ}}''), also a derivative of the ] {{lang|grc|Αἰγύπτιος}}, ''Aiguptios'' ("Egypt, Egyptian"), that appeared under ] when it overtook ] in Egypt. The term referred to the Egyptian locals, to distinguish them from the Arab rulers. ] was the language of the Christian church and people,<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130922211311/http://cdm15831.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/cce/id/520 |date=2013-09-22 }}. Cdm15831.contentdm.oclc.org. Retrieved on 2020-06-02.</ref> but lost its popularity to ] after the Muslim conquest.<ref>{{Citation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FZ8JAQAAIAAJ|title=The Muslim Conquest of Egypt and North Africa|last1=Akram|first1=A. I.|year=1977|publisher=Ferozsons |isbn=9789690002242}}</ref><ref>{{Citation|url=https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/reference-populations-next-gen/|title=National Geographic Geno 2.0 Project - Egypt|quote=Egypt= 71% North and East African. As ancient populations first migrated from Africa, they passed first through northeast Africa to southwest Asia. The Northern Africa and Arabian components in Egypt are representative of that ancient migratory route, as well as later migrations from the Fertile Crescent back into Africa with the spread of agriculture over the past 10,000 years, and migrations in the seventh century with the spread of Islam from the Arabian Peninsula. The East African component likely reflects localized movement up the navigable Nile River, while the Southern Europe and Asia Minor components reflect the geographic and historical role of Egypt as a historical player in the economic and cultural growth across the Mediterranean region.|access-date=2018-10-22|archive-date=2017-02-07|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170207031612/https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/reference-populations-next-gen//|url-status=dead}}</ref> Islam became the dominant religion centuries after the Muslim conquest in Egypt. This is due to centuries of conversion from Christianity to Islam. The modern term then became exclusively associated with ] and Coptic Christians who are members of the Coptic Orthodox Church or Coptic Catholic Church. References to native Muslims as Copts are attested until the ] period.<ref name=":0">C. Petry. "Copts in Late Medieval Egypt." ''Coptic Encyclopaedia''. 2:618 (1991).</ref> | |||

| * '''Masryeen''' ({{langx|arz|مَصريين|Maṣriyyīn}}),<ref>{{Citation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YmZyAAAAMAAJ|title=Modern Egypt: The formation of a nation state|quote= Among the peoples of the ancient Near East, only the Egyptians have stayed where they were and remained what they were, although they have changed their language once and their religion twice. In a sense, they constitute the world's oldest nation. – Arthur Goldschmidt|isbn=9780865311824|last1=Goldschmidt|first1=Arthur|year=1988|publisher=Avalon }}</ref> the modern ] name, which comes from the ancient ] name for Egypt. The term originally connoted "]" or "]".<ref>{{Citation|title=Civilizations and World Order|isbn = 9780739186077|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5QeqBAAAQBAJ&q=misr+means+civilization&pg=PA87|last1 = Dallmayr|first1 = Fred|last2 = Akif Kayapınar|first2 = M.|last3 = Yaylacı|first3 = İsmail|date = 24 September 2014| publisher=Lexington Books }}</ref> ] ''{{transliteration|ar|Miṣr}}'' (Egyptian Arabic ''{{transliteration|arz|Maṣr}}'') is directly cognate with the ] ''Mitsráyīm'' (מִצְרַיִם / מִצְרָיִם), meaning "the two straits", a reference to the predynastic separation of ]. Also mentioned in several Semitic languages as ''Mesru'', ''Misir'' and ''Masar''. The term "Misr" in Arabic refers to Egypt, but sometimes also to the Cairo area,<ref>An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, LONDON & TORONTO PUBLISHED BY J·M·DENT &SONS IN NEW YORK BY E·P ·DUTTON & CO. P4 |quote=The modem Egyptian metropolis, to the inhabitants of which most of the contents of the following pages relate, is now called " Masr", more properly, "Misr" but was formerly named " El-Kahireh;" whence Europeans have formed the name of Cairo</ref> as a consequence, and because of the habit of identifying people with cities rather than countries (i.e. Tunis (capital of Tunisia), Tunsi). The term Masreyeen originally referred only to the native inhabitants of Cairo or "City of Misr" before its meaning expanded to encompass all Egyptians. ], writing in the 1820s, said that the native Muslim inhabitants of Cairo commonly call themselves ''{{transliteration|arz|El-Maṣreeyeen}}'', ''{{transliteration|arz|Ewlad Maṣr}}'' (lit. ''Children of Masr'') and ''{{transliteration|arz|Ahl Maṣr}}'' (lit. ''The People of Masr'').<ref>An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, P 27.LONDON & TORONTO PUBLISHED BY J·M·DENT &SONS IN NEW YORK BY E·P ·DUTTON & CO. |quote=""The native Muslim inhabitants of Cairo commonly call themselves " El-Masreeyeen," "Owlad-Maasr " (or " Ahl Masr "), and "Owlad-el-Beled, which signify People of Masr, Children of. Masr, and Children of the Town : the singular forms of these appellations are "Maasree, "Ibn-Masr," and "Ibn-el-Beled." Of these three terms, the last is most common in the town itself. The country people are called "El-Fellaheen" (or the agriculturists), in the singular" Fellah. P4 |quote=The modern Egyptian metropolis, to the inhabitants of which most of the contents of the following pages relate, is now called " Masr", more properly, "Misr" but was formerly named " El-Kahireh;" whence Europeans have formed the name of Cairo"</ref> He also added that the Ottoman rulers of the region "stigmatized" the people of Egypt with the name ''{{transliteration|ar|Ahl-Far'ūn}}'' or the 'People of the Pharaoh'.<ref>Lane, Edward William. ''An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians''. Cairo: American University in Cairo, 2003. Rep. of 5th ed, 1860. pp. 26–27.</ref> | |||

| ==Demographics== | |||

| *'''{{Unicode|Maṣreyyīn}}''' (مَصريين) – The modern Egyptian name comes from the ancient ] name for Egypt and originally connoted "civilization" or "metropolis". ] ''Mi{{Unicode|ṣ}}r'' (] ''Ma{{Unicode|ṣ}}r'') is directly cognate with the ] ''Mitzráyīm'', meaning "the two straits", a reference to the predynastic separation of ]. ] writing in the 1820s, said that Egyptians commonly called themselves ''El-Ma{{Unicode|ṣ}}reeyeen'' 'the Egyptians', ''Owlad {{Unicode|Maṣr}}'' 'the Children of Egypt' and ''Ahl {{Unicode|Maṣr}}'' 'the People of Egypt'. He added that the ] "stigmatized" the Egyptians with the name ''Ahl-Far'oon'' or the 'People of the Pharaoh'.<ref>Lane, Edward William. ''An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians''. Cairo: American University in Cairo, 2003. Rep. of 5th ed, 1860. pp. 26-27.</ref> | |||

| {{main|Demographics of Egypt}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] (bottom-right) is the main performing arts venue in the Egyptian capital.]] | |||

| There are an estimated 105.3 million Egyptians.<ref>{{Cite web |title=عدد سكان مصر الآن |url=https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/populationClock.aspx |website=CAPMAS – الجهاز المركزي للتعبئة و الاحصاء}}</ref> Most are native to Egypt, where Egyptians constitute around 99.6% of the population.<ref>{{cite book|editor-last1=Martino|editor-first1=John|title=Worldwide Government Directory with Intergovernmental Organizations 2013|date=2013|publisher=CQ Press|isbn=978-1452299372|page=508|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CQWhAQAAQBAJ&q=%2299.6%22|access-date=19 July 2016|archive-date=5 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200805060728/https://books.google.com/books?id=CQWhAQAAQBAJ&q=%2299.6%22|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Demographics and society== | |||

| {{See also|Demographics of Egypt}} | |||

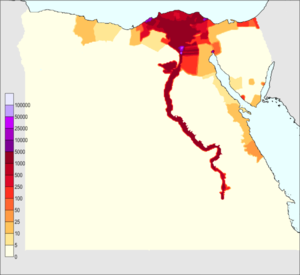

| Approximately 84–90% of the population of Egypt are ] adherents and 10–15% are ] adherents (10–15% ], 1% other Christian Sects (mainly ])) according to estimates.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/281789/Egypt/Politics-/Egypts-Sisi-meets-world-Evangelical-churches-deleg.aspx|title=Egypt's Sisi meets world Evangelical churches delegation in Cairo|work=Al-Ahram Weekly|language=en|access-date=2018-04-26|archive-date=2018-05-04|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180504020907/http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/281789/Egypt/Politics-/Egypts-Sisi-meets-world-Evangelical-churches-deleg.aspx|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Factbook">Egypt. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211009073315/https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/egypt/ |date=2021-10-09 }}. 2006.</ref> Most of Egypt's people live along the banks of the ], and more than two-fifths of the population lives in urban areas. Along the Nile, the population density is one of the highest in the world, in excess of {{convert|5,000|/mi2|/km2|disp=preunit|persons |persons|}} in a number of riverine governorates. The rapidly growing population is young, with roughly one-third of the total under age 15 and about three-fifths under 30. In response to the strain put on Egypt's economy by the country's burgeoning population, a national family planning program was initiated in 1964, and by the 1990s it had succeeded in lowering the birth rate. Improvements in health care also brought the infant mortality rate well below the world average by the turn of the 21st century. Life expectancy averages about 72 years for men and 74 years for women.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Egypt/Demographic-trends |title=Egypt-Demographic trends |website=britannica.com |access-date=2019-09-28 |archive-date=2021-09-11 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210911173048/https://www.britannica.com/place/Egypt/Demographic-trends |url-status=live }}</ref> Egyptians also form smaller minorities in neighboring countries, North America, Europe and Australia. | |||

| ] river are part of today's landscape in Egypt's capital city.]]There are an estimated 79 million Egyptians in the world, but the vast majority live in ] where they constitute 97-98% (76.4 million) of the total population. Approximately 90% of Egyptians are Muslim and 10% are Christian (9% ], 1% other Christian).<ref name="Factbook" /> Almost all live near the banks of the Nile River where the only arable land is found. Close to a half of the Egyptian people today are urban, living in the densely populated centres of greater ], ] and other major cities. Most of the rest are '']'' or farmers leading humble lives in rural towns and villages. A large influx of fellahin into urban towns and cities, and rapid urbanization of many rural areas since the turn of the last century, have shifted the balance between the number of urban and rural Egyptians. | |||

| Egyptians also tend to be provincial, meaning their attachment extends not only to Egypt but to the specific ], towns and villages from which they hail. Therefore, return migrants, such as temporary workers abroad, come back to their region of origin in Egypt. According to the ], an estimated 2.7 million Egyptians live abroad and contribute actively to the development of their country through remittances (US$7.8 billion in 2009), circulation of human and social capital, as well as investment. Approximately 70% of Egyptian migrants live in Arab countries (923,600 in ], 332,600 in ], 226,850 in ], 190,550 in ] with the rest elsewhere in the region) and the remaining 30% are living mostly in Europe and North America (318,000 in the ], 110,000 in ] and 90,000 in ]).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.egypt.iom.int/Doc/IOM%20Migration%20and%20Development%20in%20Egypt%20Facts%20and%20Figures%20(English).pdf |title=Migration And Development In Egypt |access-date=2017-10-28 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160501234716/http://www.egypt.iom.int/Doc/IOM%20Migration%20and%20Development%20in%20Egypt%20Facts%20and%20Figures%20(English).pdf |archive-date=2016-05-01}}</ref> | |||

| Egyptians also form smaller minorities in the countries that neighbour them, in particular ] and ] where they are mostly temporary professionals and workers, as well as in other countries as immigrants, notably in the ], ], ], ], ] and ]. It is also a matter of dispute whether the ] of the ] are ethnic Egyptians. | |||

| {{blockquote|Their characteristic rootedness as Egyptians, commonly explained as the result of centuries as a farming people clinging to the banks of the ], is reflected in sights, sounds and atmosphere that are meaningful to all Egyptians. Dominating the intangible pull of Egypt is the ever present Nile, which is more than a constant backdrop. Its varying colors and changing water levels signal the coming and going of the Nile flood that sets the rhythm of farming in a rainless country and holds the attention of all Egyptians. No Egyptian is ever far from his river and, except for the ] whose personality is split by looking outward toward the Mediterranean, the Egyptians are a hinterland people with little appetite for travel, even inside their own country. They glorify their national dishes, including the ]. Most of all, they have a sense of all-encompassing familiarity at home and a sense of alienation when abroad ... There is something particularly excruciating about Egyptian nostalgia for Egypt: it is sometimes outlandish, but the attachment flows through all Egyptians, as the Nile through Egypt.<ref>Wakin, Edward. A Lonely Minority. The Modern Story of Egypt's Copts. New York: William, Morrow & Company, 1963. pp. 30–31, 37.</ref>}} | |||

| The Egyptians are an autochthonous people deeply attached to their land. Historically, it was rare for Egyptians to leave their country permanently or for an extended period of time—it was not until the 1970s that Egyptians began to emigrate in large numbers. Until only recently, a study on the pattern of Egyptian emigration was quoted as saying "Egyptians have a reputation of preferring their own soil. Few leave except to study or travel; and they always return... Egyptians do not emigrate."<ref>qtd. in Talani, p. 20</ref> Egyptians also tend to be provincial, meaning their attachment extends not only to Egypt but to the specific ], towns and villages from which they hail. Therefore, return migrants, such as temporary workers abroad, come back to their region of origin in Egypt. | |||

| A sizable ] did not begin to form until well into the 1980s, when political and economic conditions began driving Egyptians out of the country in significant numbers. Today, the diaspora numbers nearly 4 million (2006 est).<ref name="Ahram Weekly 1">of which c. 4 million in the ]. Newsreel. {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071011173545/http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2007/839/eg1.htm |date=2007-10-11}}. 2007, ''Ahram Weekly''. 5–11 April</ref> Generally, those who emigrate to the United States and western European countries tend to do so permanently, with 93% and 55.5% of Egyptians (respectively) settling in the new country. On the other hand, Egyptians migrating to Arab countries almost always only go there with the intention of returning to Egypt; virtually none settle in the new country on a permanent basis.<ref name="Talani">Talani, Leila S. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081210171941/http://repositories.cdlib.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1014&context=international/cees |date=2008-12-10 }} University of California, Los Angeles. 2005.</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|Their characteristic rootedness as Egyptians, commonly explained as the result of centuries as a farming people clinging to the banks of the Nile, is reflected in sights, sounds and atmosphere that are meaningful to all Egyptians. Dominating the intangible pull of Egypt is the ever present ], which is more than a constant backdrop. Its varying colors and changing water levels signal the coming and going of the Nile flood that sets the rhythm of farming in a rainless country and holds the attention of all Egyptians. No Egyptian is ever far from his river and, except for the ] whose personality is split by looking outward toward the Mediterranean, the Egyptians are a hinterland people with little appetite for travel, even inside their own country. They glorify their national dishes, including the ]. Most of all, they have a sense of all-encompassing familiarity at home and a sense of alienation when abroad... There is something particularly excruciating about Egyptian nostalgia for Egypt: it is sometimes outlandish, but the attachment flows through all Egyptians, as the Nile through Egypt.<ref>Wakin, Edward. A Lonely Minority. The Modern Story of Egypt's Copts. New York: William, Morrow & Company, 1963. pp. 30-31, 37.</ref>}} | |||

| Prior to 1974, only few Egyptian professionals had left the country in search for employment. Political, demographic and economic pressures led to the first wave of emigration after 1952. Later more Egyptians left their homeland first after the 1973 boom in oil prices and again in 1979, but it was only in the second half of the 1980s that Egyptian migration became prominent.<ref name="Talani" /> | |||

| A sizable Egyptian diaspora did not begin to form until well into the 1980s, today numbering nearly 3 million (2004 est).<ref name="Egypt Today" /> Generally, those who emigrate to the United States and western European countries tend to do so with the intention of settling permanently, while Egyptians migrating to neighboring countries in the Middle East only go there to work with the intention of returning to Egypt: | |||

| Egyptian emigration today is motivated by even higher rates of unemployment, population growth and increasing prices. Political repression and human rights violations by Egypt's ruling régime are other contributing factors (see {{format link|Egypt#Human rights}}). Egyptians have also been impacted by the wars between Egypt and ], particularly after the ] in 1967, when migration rates began to rise. In August 2006, Egyptians made headlines when 11 students from ] failed to show up at their American host institutions for a cultural exchange program in the hope of finding employment.<ref>Mitchell, Josh. {{cite web |url=http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/local/baltimore_county/bal-md.co.egyptians13aug13,0,4970784.story?coll=bal-local-headlines |title=Egyptians came for jobs, then built lives |access-date=2008-04-13 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060819050909/http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/local/baltimore_county/bal-md.co.egyptians13aug13,0,4970784.story?coll=bal-local-headlines |archive-date=August 19, 2006 }}. Baltimore Sun. August 13, 2006.</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|Only a reduced number of Egyptians, primarily professionals, had left the country in search for employment before 1974. Scholars identify three phases in the evolution of the Egyptian migratory flows... Coexisting political, demographic and economic pressures led to the first wave of international migration in post-revolutionary Egypt, which, however, interested only a very limited number of students and professionals... With the advent of the 1970s, Egyptian emigration changed in nature, size and destination. More Egyptians left their homeland and headed towards the rich oil-producing states, first after the 1973 boom in oil prices and again after the second increase in oil prices in 1979. However, it was only in the second half of the 1980s that Egyptian migration became a relevant phenomenon, entering its last phase of development... Two-thirds of Egyptian migration is temporary, while the other third is permanent... most going to western European countries (55.5%) and almost all those who go to the US and Australia (93%) are permanent migrants. On the contrary, the whole sample of those going to Arab countries (100%) intends to go back to Egypt.<ref name="Talani" />}} | |||

| Egyptians in neighboring countries face additional challenges. Over the years, abuse, exploitation and/or ill-treatment of Egyptian workers and professionals in the ], ] and ] have been reported by the Egyptian Human Rights Organization<ref>EHRO. . March 2003. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060616085024/http://www.eohr.org/report/2003/5-1103.htm |date=June 16, 2006}}</ref> and different media outlets.<ref>IRIN. . March 7, 2006. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060907044418/http://www.irinnews.org/report.asp?ReportID=52063&SelectRegion=Middle_East&SelectCountry=EGYPT |date=September 7, 2006}}</ref><ref>Evans, Brian. .</ref> Arab nationals have in the past expressed fear over an "'Egyptianization' of the local dialects and culture that were believed to have resulted from the predominance of Egyptians in the field of education"<ref name="UN">Kapiszewski, Andrzej. . May 22, 2006. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060731021826/http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/EGM_Ittmig_Arab/P02_Kapiszewski.pdf |date=July 31, 2006 }}</ref> (see also ]). | |||

| ]in'' or farmers. The percentage was much higher at the turn of the last century, before rapid urbanization and large-scale in-migration shifted Egypt's demographics.]]Egyptian emigration is primarily motivated by economic and political considerations. High rates of unemployment and population growth are two of the socioeconomic conditions that steadily deteriorated following the 1952 ], leading scores of Egyptians to seek better opportunities in foreign countries. Political repression and human rights violations by Egypt's ruling régime are other contributing factors (see ]). Egyptians have also been impacted by the wars between Egypt and ], particularly after the ] in 1967, when migration rates began to rise. In August 2006, Egyptians made headlines when 11 students from ] failed to show up at their ] host institutions for a cultural exchange program in the hope of finding employment.<ref>Mitchell, Josh. . Baltimore Sun. August 13, 2006.</ref> Many ] also leave the country due to discrimination and harassment by the Egyptian government and Islamist groups. | |||

| A Newsweek article in 2008 featured Egyptian citizens objecting to a prudish "Saudization" of their culture due to Saudi Arabian petrodollar-flush investment in the Egyptian ].<ref name="Newsweek">{{cite web|url=http://www.newsweek.com/id/139434|title=The Last Egyptian Belly Dancer|access-date=2008-06-02|publisher=Newsweek|year=2008|author=Rod Nordland|archive-date=2010-03-28|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100328214128/http://www.newsweek.com/id/139434|url-status=live}}</ref> Twice Libya was on the brink of war with Egypt due to mistreatment of Egyptian workers and after the signing of the ] with Israel.<ref>AfricaNet. . {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060503055624/http://www.africanet.com/africanet/country/libya/home.htm |date=May 3, 2006 }}</ref> When the ] ended, Egyptian workers in Iraq were subjected to harsh measures and expulsion by the Iraqi government and to violent attacks by Iraqis returning from the war to fill the workforce.<ref>Vatikiotis, P.J. ''The History of Modern Egypt''. 4th edition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1992, p. 432</ref> | |||

| == |

==History== | ||

| {{Main|Population history of Egypt}} | |||

| {{Further|History of Egypt}} | |||

| ===Ancient Egypt=== | |||

| ] King ].]]Over the years, the findings of ], ] and ] have shed light on the origins of the Egyptians. The indigenous Nile Valley population became firmly established during the ] when nomadic ]s began living along the ] river. Traces of these proto-Egyptians appear in the form of artifacts and rock carvings in the terraces of the Nile and the desert oases. Beginning in the ], some differences between the populations of Upper and Lower Egypt were ascertained through their skeletal remains, suggesting a gradual ] pattern north to south.<ref>Batrawi A (1945). ''The racial history of Egypt and Nubia'', Part I. J Roy Anthropol Inst 75:81-102.</ref><ref>Batrawi A. 1946. ''The racial history of Egypt and Nubia, Part II''. J Roy Anthropol Inst 76:131-156.</ref><ref>Keita SOY (1990). ''Studies of ancient crania from northern Africa''. Am J Phys Anthropol 83:35–48.</ref><ref>Keita SOY (1992). ''Further studies of crania from ancient northern Africa: an analysis of crania from First Dynasty Egyptian tombs''. Am J Phys Anthropol 87:245–254.</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Ancient Egypt|History of ancient Egypt}} | |||

| {{Hiero | 'People of the Black Lands' | <hiero>r:T-A1-B1-Z3 km-m-t:niwt</hiero> | align=right | era=default}} | |||

| When Lower and Upper Egypt were unified ''c''. 3150 BC, the distinction began to blur, resulting in a more "homogeneous" population in Egypt, though the distinction remains true to some degree to this day.<ref>Berry AC, Berry RJ, Ucko PJ (1967). ''Genetical change in ancient Egypt''. Man 2:551–568.</ref><ref>Brace CL, Tracer DP, Yaroch LA, Robb J, Brandt K, Nelson AR (1993). ''Clines and clusters versus "race:" a test in ancient Egypt and the case of a death on the Nile''. ''.</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author=Irish JD | title=Who were the ancient Egyptians? Dental affinities among Neolithic through postdynastic peoples. | journal=Am J Phys Anthropol | volume=129 | issue=4 | pages=529-43 | year=2006 | id=PMID 16331657}}</ref> Some biological anthropologists such as ] believe the range of variability to be primarily indigenous and not necessarily the result of significant intermingling of widely divergent peoples.<ref>Keita SOY and Rick A. Kittles. ''The Persistence of Racial Thinking and the Myth of Racial Divergence''. American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 99, No. 3 (Sep., 1997), pp. 534-544</ref> Keita describes the northern and southern patterns of the early ] period as "northern-Egyptian-Maghreb" and "tropical African variant" (overlapping with ]/]) respectively. He shows that a progressive change in Upper Egypt toward the northern Egyptian pattern takes place through the predynastic period. The southern pattern continues to predominate by the ], but "lower Egyptian, Maghrebian, and European patterns are observed."<ref>Keita 1992, p. 252</ref> | |||

| ] saw a succession of thirty ] spanning three millennia. During this period, Egyptian culture underwent significant development in terms of ], ], ], and customs. | |||

| A 2006 ] study on the dental morphology of ancient Egyptians by Prof. Joel Irish shows dental traits characteristic of indigenous ]ns and to a lesser extent ]n populations. Among the samples included in the study is skeletal material from the ], which clustered very closely with the ] series of the ] period. All the samples, particularly those of the Dynastic period, were significantly divergent from a neolithic West Saharan sample from Lower Nubia. Biological continuity was also found intact from the dynastic to the post-pharaonic periods. According to Irish: | |||

| <blockquote> samples exhibit morphologically simple, mass-reduced dentitions that are similar to those in populations from greater North Africa (Irish, 1993, 1998a–c, 2000) and, to a lesser extent, western Asia and Europe (Turner, 1985a; Turner and Markowitz, 1990; Roler, 1992; Lipschultz, 1996; Irish, 1998a). Similar craniofacial measurements among samples from these regions were reported as well (Brace et al., 1993)... an inspection of MMD values reveals no evidence of increasing phenetic distance between samples from the first and second halves of this almost 3,000-year-long period. For example, phenetic distances between First-Second Dynasty Abydos and samples from Fourth Dynasty Saqqara (MMD ¼ 0.050), 11-12th Dynasty Thebes (0.000), 12th Dynasty Lisht (0.072), 19th Dynasty Qurneh (0.053), and 26th–30th Dynasty Giza (0.027) do not exhibit a directional increase through time... Thus, despite increasing foreign influence after the Second Intermediate Period, not only did Egyptian culture remain intact (Lloyd, 2000a), but the people themselves, as represented by the dental samples, appear biologically constant as well... Gebel Ramlah is, in fact, significantly different from Badari based on the 22-trait MMD (Table 4). For that matter, the Neolithic Western Desert sample is significantly different from all others is closest to predynastic and early dynastic samples.<ref>Irish pp. 10-11</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ]A group of noted physical anthropologists conducted craniofacial studies of Egyptian skeletal remains and concluded similarly that "the Egyptians have been in place since back in the Pleistocene and have been largely unaffected by either invasions or migrations. As others have noted, Egyptians are Egyptians, and they were so in the past as well."<ref>Brace et al. 1993 </ref> | |||

| ] analysis of modern Egyptians reveals that they have ] lineages common to indigenous North Africans/] populations primarily, and to ]ern peoples to a lesser extent. These lineages would have spread during the ] and maintained by the ].<ref>{{cite journal | author=Arredi B, Poloni E, Paracchini S, Zerjal T, Fathallah D, Makrelouf M, Pascali V, Novelletto A, Tyler-Smith C | title=A predominantly neolithic origin for Y-chromosomal DNA variation in North Africa. | journal=Am J Hum Genet | volume=75 | issue=2 | pages=338-45 | year=2004 | id=PMID 15202071}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author=Manni F, Leonardi P, Barakat A, Rouba H, Heyer E, Klintschar M, McElreavey K, Quintana-Murci L | title=Y-chromosome analysis in Egypt suggests a genetic regional continuity in Northeastern Africa. | journal=Hum Biol | volume=74 | issue=5 | pages=645-58 | year=2002 | id=PMID 12495079}}</ref> Studies based on ] lineages also link Egyptians with people from modern ]/] such as the ].<ref>{{cite journal | author=Kivisild T, Reidla M, Metspalu E, Rosa A, Brehm A, Pennarun E, Parik J, Geberhiwot T, Usanga E, Villems R | title=Ethiopian mitochondrial DNA heritage: tracking gene flow across and around the gate of tears. | journal=Am J Hum Genet | volume=75 | issue=5 | pages=752-70 | year=2004 | id=PMID 15457403}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author=Stevanovitch A, Gilles A, Bouzaid E, Kefi R, Paris F, Gayraud R, Spadoni J, El-Chenawi F, Béraud-Colomb E | title=Mitochondrial DNA sequence diversity in a sedentary population from Egypt. | journal=Ann Hum Genet | volume=68 | issue=Pt 1 | pages=23-39 | year=2004 | id=PMID 14748828}}</ref> | |||

| Egypt fell under ] rule in the Middle ]. The native nobility managed to expel the conquerors by the ], thereby initiating the ]. During this period, the Egyptian civilization rose to the status of an empire under Pharaoh ] of the ]. It remained a super-regional power throughout the ] as well as during the ] and ] dynasties (the Ramesside Period), lasting into the Early ]. | |||

| ] Egyptologist Frank Yurco confirmed this finding of historical and regional continuity, saying: | |||

| <blockquote>Certainly there was some foreign admixture , but basically a homogeneous African population had lived in the Nile Valley from ancient to modern times... Badarian people, who developed the earliest Predynastic Egyptian culture, already exhibited the mix of North African and Sub-Saharan physical traits that have typified Egyptians ever since (Hassan 1985; Yurco 1989; Trigger 1978; Keita 1990; Brace et al., this volume)... The peoples of Egypt, the Sudan, and much of East Africa, Ethiopia and Somalia are now generally regarded as a Nilotic (i.e. Nile River) continuity, with widely ranging physical features (complexions light to dark, various hair and craniofacial types) but with powerful common cultural traits, including cattle pastoralist traditions (Trigger 1978; Bard, Snowden, this volume). Language research suggests that this Saharan-Nilotic population became speakers of the Afro-Asiatic languages... Semitic was evidently spoken by Saharans who crossed the Red Sea into Arabia and became ancestors of the Semitic speakers there, possibly around 7000 BC... In summary we may say that Egypt was distinct North African culture rooted in the Nile Valley and on the Sahara.<ref>Frank Yurco, "An Egyptological Review" in Mary R. Lefkowitz and Guy MacLean Rogers, eds. ''Black Athena Revisited''. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996. p. 62-100</ref></blockquote> | |||

| The ] that had afflicted the Mesopotamian empires reached Egypt with some delay, and it was only in the 11th century BC that the Empire declined, falling into the comparative obscurity of the ]. The ] of ] rulers was again briefly replaced by native nobility in the 7th century BC, and in 525 BC, Egypt fell under ]. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{main|History of Egypt}} | |||

| {{Hiero | ''rmṯ (n) kmt'' (People of Egypt; "Egyptians") | <hiero>r:T-A1-B1-Z3 km-m-t:niwt</hiero> | align=right | era=default}} | |||

| Egypt fell under Greek control after ]'s conquest in 332 BC. The ] is taken to end with his death in 323 BC. The ] ruled Egypt from 305 BC to 30 BC and introduced ] culture to Egyptians. 4,000 ] mercenaries under Ptolemy II had even attempted an ambitious but doomed coup d'état around the year 270 BC.{{citation needed|date=March 2023}} | |||

| Egyptians may have the longest continuous history of any people, spanning a period of some 7,000 years. The Egyptians' recorded history starts with the unification of ] ''c''. 3150 BC, an event that sparked the beginning of Egypt's ]. A succession of thirty mostly native dynasties ruled for the next three ], during which Egyptian culture flourished and remained distinctively Egyptian in its ], ], ] and ]. ] conquered Egypt in ], giving rise to the ] which introduced ] culture to the Egyptians, but continued to rule according to ancient Egyptian traditions. This stability shifted when the Egyptians fell under ] rule, most notably with the introduction of ] in Egypt by ] in the ] AD. The Egyptians were soon incorporated within the ] fold and remained so until the ] AD, when Egypt became part of the ] following ]'s conquest that brought ] to Egypt. Egyptians were ruled by a succession of ], ] ], ] and ] until independence was reasserted in 1922 and a republic was declared in 1953. | |||

| Throughout the Pharaonic epoch (viz., from 2920 BC to 525 BC in ]), ] was the glue which held Egyptian society together. It was especially pronounced in the ] and ] and continued until the Roman conquest. The societal structure created by this system of government remained virtually unchanged up to modern times.<ref>Grimal, p. 93</ref> | |||

| ===Prehistory=== | |||

| The role of the king was considerably weakened after the ]. The king in his role as Son of Ra was entrusted to maintain ], the principle of truth, justice, and order, and to enhance the country's agricultural economy by ensuring regular ]. Ascendancy to the Egyptian throne reflected the myth of Horus who assumed kingship after he buried his murdered father ]. The king of Egypt, as a living personification of Horus, could claim the throne after burying his predecessor, who was typically his father. When the role of the king waned, the country became more susceptible to foreign influence and invasion. | |||

| ] findings show that primitive tribes lived along the Nile long before the ] of the ]s began. By about 5500 BC, Egypt was inhabited by settled communities of people who cultivated emmer wheat and barley, made pottery, weaved linen and raised sheep, goats and cattle. Before the unification of ], northern Egyptians seem to have been somewhat culturally distinct from their neighbors to the south. Surviving evidence for early settlement in Lower Egypt such as pottery, houses and burial sites appear different from those of the Upper Egyptians. The earliest known predynastic northern Egyptian site, Merimda, predates the earliest in Upper Egypt, the ], by about 700 years.<ref>Watterson, Barbara. ''The Egyptians''. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. 1997. p. 30.</ref> However, later predynastic Lower Egyptians were in contact with not only contemporaneous southern Egyptians, but also with people from the ] and with the ] of ], as some of the plants cultivated and the pottery types found in Lower Egypt resemble those of neighboring cultures.<ref>Midant-Reynes, Béatrix. ''The Prehistory of Egypt: From the First Egyptians to the First Pharaohs''. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. 2000. p. 219.</ref> | |||

| The attention paid to the dead, and the veneration with which they were held, were one of the hallmarks of ]. Egyptians built tombs for their dead that were meant to last for eternity. This was most prominently expressed by the ]. The ancient ] word for tomb ''{{transliteration|egy|pr nḥḥ}}'' means ']'. The Egyptians also celebrated life, as is shown by tomb reliefs and inscriptions, papyri and other sources depicting Egyptians farming, conducting trade expeditions, hunting, holding festivals, attending parties and receptions with their pet dogs, cats and monkeys, dancing and singing, enjoying food and drink, and playing games. The ancient Egyptians were also known for their engaging sense of humor, much like their modern descendants.<ref>Watterson, p. 15</ref> | |||

| Prehistoric Lower Egyptians already believed in an existence after death, as attested by their grave goods.<ref>Watterson, p. 30.</ref> Each province before the unification of Egypt acquired its own animal deity. ] and ] were worshipped in the ] towns of ] and ] respectively, while ] and ] were the Upper Egyptian deities of ] and ]. The predynastic settlements of Upper Egypt displayed more elaborate funerary practices and artifacts that were more clearly the direct predecessors of those of the dynastic Egyptians. Significantly, the earliest known evidence of ]ic inscriptions appears on ] III pottery vessels dated to about 3200 BC.<ref>Bard, Kathryn A. Ian Shaw, ed. ''The Oxford Illustrated History of Ancient Egypt''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. p. 69.</ref> During the predynastic and ] periods, the southern Egyptian cities of ], ] (Hierakonpolis) and ] were major centers of power. The first attempt to conquer Lower Egypt seems to have been made by a king from Nekhen known as Scorpion, but it would be another 100 years or so before another upper Egyptian king successfully unified the two lands.<ref>Watterson, p. 42</ref> | |||

| Another important continuity during this period is the Egyptian attitude toward foreigners—those they considered not fortunate enough to be part of the community of ''rmṯ'' or "the people" (i.e., Egyptians.) This attitude was facilitated by the Egyptians' more frequent contact with other peoples during the New Kingdom when Egypt expanded to an empire that also encompassed ] through ] and parts of the ]. | |||

| ===Dynastic period=== | |||

| {{main|Ancient Egypt|History of Ancient Egypt}} | |||

| The Egyptian sense of superiority was given religious validation, as foreigners in the land of ''Ta-Meri'' (Egypt) were anathema to the maintenance of Maat—a view most clearly expressed by the ] in reaction to the chaotic events of the ]. Foreigners in Egyptian texts were described in derogatory terms, e.g., 'wretched Asiatics' (Semites), 'vile Kushites' (Nubians), and 'Ionian dogs' (Greeks). Egyptian beliefs remained unchallenged when Egypt fell to the Hyksos, ]ns, ], Persians and Greeks—their rulers assumed the role of the Egyptian Pharaoh and were often depicted praying to Egyptian gods. | |||

| ] believed to depict the unification of ].]]The beginning of the Egyptians' recorded history starts with the unification of Lower and Upper Egypt by the Upper Egyptian king ] (identified with the pharaoh ]). He founded ]'s ] around 3150 BC. To strengthen his political role, King Menes/Narmer married the northern Egyptian princess Neithotep and took on the title of ], i.e., ], the vulture goddess of Upper Egypt and ] the cobra goddess worshipped by the Lower Egyptians, as a symbol of the unification. ], like the Egyptian historian ], associated the unification with King Menes. He also indicated that Menes founded the ancient city of ] in Lower Egypt, which became the new capital of the unified country. The Egyptians from this point onwards referred to the country as ''tAwy'', Two Lands, a name that came to predominate until the ] period when the name ''km.t'' (]: ''kīmi''), Black Land, was more commonly used. The first two dynasties of Egypt were each ruled by eight kings and lasted for a combined period of nearly 400 years. | |||

| The ancient Egyptians used a solar calendar that divided the year into 12 months of 30 days each, with five extra days added. The calendar revolved around the annual ] Inundation (''akh.t''), the first of three seasons into which the year was divided. The other two were Winter and Summer, each lasting for four months. The modern Egyptian '']in'' calculate the agricultural seasons, with the months still bearing their ancient names, in much the same manner. | |||

| ====Old Kingdom==== | |||

| The importance of the Nile in Egyptian life, ancient and modern, cannot be overemphasized. The rich alluvium carried by the Nile inundation was the basis of Egypt's formation as a society and a state. Regular inundations were a cause for celebration; low waters often meant famine and starvation. The ancient Egyptians personified the river flood as the god ] and dedicated a ''Hymn to the Nile'' to celebrate it. ''km.t'', the Black Land, was as ] observed, "the gift of the river." | |||

| ], ].]]By the end of the ], a strong centralized government was firmly established with Memphis as its capital city, and the foundations of the first peak period of Egyptian civilization were laid. The following era in Egyptian history, the ] (''c''. 2700−2200 BC), is particularly famous for its magnificent superstructures, many of which served as royal tombs for the pharaohs. They were state-sponsored projects built in the ] and ] dynasties and in which the whole of the Egyptian population often participated. Building typically commenced during the Nile's Inundation when agricultural lands were submerged in water and people could not farm. King ]'s ] at ], engineered by the famous architect and physician ], and the ] are among this period's most famous examples. They are a testament to the Egyptians' extraordinary competence in astronomy and mathematics very early in their history. It is believed that many parts of famous medical papyri that appear in later periods, particularly the ], were written during this period by Imhotep and other Egyptian doctors.<ref>Nunn, John F. ''Ancient Egyptian Medicine''. University of Oklahoma Press, 1996. p. 11</ref> | |||

| ===Graeco-Roman period=== | |||

| ].]]Egyptian ] and ] took definitive shape in the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom periods. The local pantheon, which had been in the predynastic period confined to sacred animal deities, expanded to include cosmic gods representing the sun, moon, sky and wind. This constituted an effort toward greater philosophical and intellectual development.<ref>Watterson, p. 65</ref> Solar worship embodied in the cults of ] and ]—subsequently Atum-Ra—came to particular prominence in the Old Kingdom. Other important dieties during this period were ], ] and ]. The art of ] was also honed before the end of this period. The oldest known mummy dates to the ] and was found in Saqqara.<ref>Watterson p. 69</ref> Lasting for an estimated 500 years, the Old Kingdom was the quintessential Egyptian civilization. Insular and unchallenged from abroad, the Egyptians enjoyed a time of continuous prosperity and stability unmatched by any other period, leading one historian to describe it as the "Peaceable Kingdom of historical memory."<ref>Jankowski, James. ''Egypt: A Short History''. Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2000. p. 5</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Ptolemaic Kingdom|Egypt (Roman province)}} | |||

| ], ''c.'' AD 125 − AD 150]] | |||

| When Alexander died, a story began to circulate that ] was Alexander's father. This made Alexander in the eyes of the Egyptians a legitimate heir to the native pharaohs.<ref>Watterson, p. 192</ref> The new Ptolemaic rulers, however, exploited Egypt for their own benefit and a great social divide was created between Egyptians and Greeks.<ref>Kamil, Jill. ''Coptic Egypt: History and Guide''. Cairo: American University in Cairo, 1997. p. 11</ref> The local priesthood continued to wield power as they had during the Dynastic age. Egyptians continued to practice their religion undisturbed and largely maintained their own separate communities from their foreign conquerors.<ref>Watterson, p. 215</ref> The language of administration became ], but the mass of the Egyptian population was ]-speaking and concentrated in the countryside, while most Greeks lived in Alexandria and only few had any knowledge of Egyptian.<ref>Jankowski, p. 28</ref> | |||

| ====Middle Kingdom==== | |||

| {| style="border: 0px" align="left" | |||

| |-- | |||

| |] depicted in statue: Lion-headed with flared mane, ].]] | |||

| |-- | |||

| |], ''c''. 1525 BC.]] | |||

| |}A period of political fragmentation led to the ]. It lasted for about 150 years during which central authority and social order were maintained by local governors. Stronger Nile floods and stabilization of government brought back renewed prosperity for the country in the ] ''c''. 2040 BC, reaching a peak during the reign of ]. ] (modern ]) became the new capital during the ], though government administration remained in Memphis. Egyptians regularly traded with their neighbors to the south and east, and their political influence extended into those areas. However, land cultivation and stock raising remained the foundation of Egypt's economy, as they would during the course of Egyptian history. The state did not institute a system of coinage until the ]—most business hitherto was conducted by barter.<ref>Watterson, p. 62</ref> The Middle Kingdom became a golden age of Egyptian literature thanks to a large body of textual evidence that made this stage of ] (i.e., Middle Egyptian) the classical phase of the language. | |||

| The Ptolemaic rulers all retained their Greek names and titles, but projected a public image of being Egyptian pharaohs. Much of this period's vernacular literature was composed in the ] phase and script of the Egyptian language. It was focused on earlier stages of Egyptian history when Egyptians were independent and ruled by great native pharaohs such as ]. Prophetic writings circulated among Egyptians promising expulsion of the Greeks, and frequent revolts by the Egyptians took place throughout the Ptolemaic period.<ref>Kamil, p. 12</ref> A revival in animal cults, the hallmark of the Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods, is said to have come about to fill a spiritual void as Egyptians became increasingly disillusioned and weary due to successive waves of foreign invasions.<ref>Watterson, p. 214</ref> | |||

| The end of the Middle Kingdom was brought about by a decline in central authority which led to Egypt being occupied for the first time during its dynastic history. The ] invaders were a ] people who took over much of Lower Egypt around 1650 BC, and founded a new capital at ]. They ruled as Egyptian pharaohs and their names were often inscribed on scarabs bearing both the their Semitic and Egyptian titles. Hyksos rule lasted just over 100 years when they were eventually driven out by the native Egyptian nobleman ]. Despite the Hyksos' attempt to rule according to native Egyptian traditions, the Egyptians' perception of them was consistently negative. They were depicted as "uncouth barbarians who 'ruled without Re.'"<ref>Jankowski, p. 6</ref> Ahmose took to the throne in a re-unified Egypt, and with his rule began a period of Egyptian independence as well as expansion into surrounding regions. | |||

| When the ] annexed Egypt in 30 BC, the social structure created by the Greeks was largely retained, though the power of the Egyptian priesthood diminished. The Roman emperors lived abroad and did not perform the ceremonial functions of Egyptian kingship as the Ptolemies had. The art of ] flourished, but Egypt became further stratified with Romans at the apex of the social pyramid, Greeks and ] occupied the middle stratum, while Egyptians, who constituted the vast majority, were at the bottom. Egyptians paid a poll tax at full rate, Greeks paid at half-rate and Roman citizens were exempt.<ref>Watterson, p. 237</ref> | |||

| ====New Kingdom==== | |||

| The Roman emperor ] advocated the expulsion of all ethnic Egyptians from the city of Alexandria, saying "genuine Egyptians can easily be recognized among the linen-weavers by their speech."<ref>qtd. in Alan K. Bowman ''Egypt after the Pharaohs, 332 BC − AD 642''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996. p. 126.</ref> This attitude lasted until AD 212 when Roman citizenship was finally granted to all the inhabitants of Egypt, though ethnic divisions remained largely entrenched.<ref>Jankowski, p. 29</ref> The Romans, like the Ptolemies, treated Egypt like their own private property, a land exploited for the benefit of a small foreign elite. The Egyptian peasants, pressed for maximum production to meet Roman quotas, suffered and fled to the desert.<ref>Kamil, p. 16</ref> | |||

| ], ], ''c''. 1333 – 1324 BC.]]The ] is perhaps the most celebrated period of Egyptian history. Lasting from roughly 1550 to 1070 BC, the period marked the rise of Egypt as an international power. Ahmose founded the ] and relocated the capital to ], though once again Memphis remained the administrative capital. The Egyptians emerged from the shock of the Hyksos invasion determined to protect Egypt's national and territorial integrity. The Egyptian army developed into a well-organized service made up of professionally trained soldiers. International relations became a primary concern for the New Kingdom pharaohs. Egyptians were introduced to many foreign ideas, some of which they adopted and incorporated into their lifestyle. As in most periods, agriculture and stock farming continued to be the mainstays of Egyptian economy. The introduction of the ] from western Asia helped develop more efficient methods of irrigation. ] rose to become a state god and was ] with Ra as Amun-Ra. The main ] built in Thebes is the largest structure in the ] complex. | |||

| The cult of ], like those of ] and ], had been popular in Egypt and throughout the ] at the coming of Christianity, and continued to be the main competitor with Christianity in its early years. The main temple of Isis remained a major center of worship in Egypt until the reign of the ] emperor ] in the 6th century, when it was finally closed down. Egyptians, disaffected and weary after a series of foreign occupations, identified the story of the mother-goddess Isis protecting her child ] with that of the ] and her son ] escaping the emperor ].<ref>Kamil, p. 21</ref> | |||

| Perhaps this period is best known for some of its rulers. Queen ] was one of only a few Egyptian female rulers and their most influential. She sent trade missions as far south as the coast of modern ], and her numerous building projects, most notably her ] complex at ], were rivaled only by those of her Old Kingdom predecessors. ], dubbed the Napoleon of Egypt, pushed Egypt's southern frontier to the Fourth Cataract in ], then conquered and subsequently founded protectorates in the ]. He undertook a building program at Karnak, including the festival temple "Effective of Monuments" in the precinct of Amun.<ref>Besty M. Bryan. ''18th Dynasty before the Amarna Period (''c''. 1550-1352 BC)'' in Shaw, p. 259</ref> ] with his wife ] revolutionized Egyptian religion, albeit briefly, with the solar ] of ]. Young King ] is world famous for his magnificent tomb found intact. ] conducted many successful military campaigns and signed what may be the world's first peace treaty.<ref>Grimal, Nicolas. ''A History of Ancient Egypt''. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. 1997. p. 257</ref> He constructed many impressive monuments, including the renowned archaeological complex of ] and the memorial temple of ]. ] was the last of the great pharaohs of the New Kingdom, under whose rule Egypt reached a peak of prosperity.<ref>Watterson, p. 123</ref> | |||

| Consequently, many sites believed to have been the resting places of the holy family during their sojourn in Egypt became sacred to the Egyptians. The visit of the holy family later circulated among Egyptian Christians as fulfillment of the Biblical prophecy "When Israel was a child, then I loved him, and called my son out of Egypt" (Hosea 11:1). The feast of the coming of the Lord of Egypt on June 1 became an important part of Christian Egyptian tradition. According to tradition, Christianity was brought to Egypt by ] in the early 40s of the 1st century, under the reign of the Roman emperor ]. The earliest converts were Jews residing in ], a city which had by then become a center of culture and learning in the entire Mediterranean '']''. | |||

| ====Late period==== | |||

| ] period, AD 1249–50. Images depict ] in the Garden of Gethsemane, the kiss of ], the arrest of Christ, his appearance before ], Peter's denial at cockcrow, Christ before ], and the baptism of Jesus in the ].]] | |||

| ] was Egypt's last native Pharaoh, 360 − 343 BC.]]When the New Kingdom came to an end, the priests of Amun and the military had become powerful and independent at the expense of the throne. By 1200 BC, Egypt was under repeated attacks by ] from the west and invaders from the ] region referred to as the ]. The country fell into the chaos of the ] during which authority was divided among several competing ]s. The 22nd through the 25th dynasties were made up entirely of Libyan and ]n/]ite rulers. The ]ns invaded and took of control of Egypt in the 7th century BC, but soon a native Egyptian dynasty drove out the Assyrians and reclaimed the throne. The ] began the Saïte period which witnessed another period of Egyptian independence as well as a cultural revival. The first Saïte king, ], founded a new capital at ] and reunified upper and lower Egypt. Egyptians looked at the Old Kingdom, by then a 2000-year-old civilization, for inspiration in their artistic and religious expression to cope with the repeated foreign assaults on their country at the close of the Pharaonic era. | |||

| St. Mark is said to have founded the Holy Apostolic See of Alexandria and to have become its first ]. Within 50 years of St. Mark's arrival in Alexandria, a fragment of ] writings appeared in ] (Bahnasa), which suggests that Christianity already began to spread south of Alexandria at an early date. By the mid-third century, a sizable number of Egyptians were persecuted by the Romans on account of having adopted the new Christian faith, beginning with the Edict of ]. Christianity was tolerated in the Roman Empire until AD 284, when the Emperor ] persecuted and put to death a great number of Christian Egyptians.<ref name="Jankowski, p. 32">Jankowski, p. 32</ref> | |||

| Soon Egypt fell to the ] led by ] in 525 BC, marking more than a century of Persian rule. Constant revolting by Egyptians through the 5th century BC culminated in the Egyptians reasserting their independence briefly under ], who led a revolt from the ] and took control of Memphis and Upper Egypt.<ref>Watterson, p. 181</ref> Egyptians remained independent until the reign of King ], who was to be the last native ruler of pharaonic Egypt. The country prospered during his reign (360−343 BC) and he undertook large building and sculpture construction comparable to those of the Saïte period.<ref>Watterson, p. 182</ref> The Persians under ] dealt a final blow to the Egyptians' independence when they reconquered Egypt in 343 BC. ], on his way to conquer and dismantle the ], arrived in Egypt in 332 BC. After Alexander's death, the Greek Macedonian ] was established by one of his generals, which continued to rule the country along pharaonic traditions. Alexander founded the city of ] which became the new capital of Egypt until the ] period. When the last and most famous of the Ptolemies, Queen ], was defeated along with ] by the Roman Emperor ] in the ], it marked the end of 3000 years of Dynastic Egyptian history. | |||

| This event became a watershed in the history of Egyptian Christianity, marking the beginning of a distinct Egyptian or ]. It became known as the 'Era of the Martyrs' and is commemorated in the ] in which dating of the years began with the start of Diocletian's reign. When Egyptians were persecuted by Diocletian, many retreated to the desert to seek relief. The practice precipitated the rise of ], for which the Egyptians, namely ], ], ] and ], are credited as pioneers. By the end of the 4th century, it is estimated that the mass of the Egyptians had either embraced Christianity or were nominally Christian.<ref name="Jankowski, p. 32"/> | |||

| ====Society==== | |||

| The ] was founded in the 3rd century by ], becoming a major school of Christian learning as well as science, mathematics and the humanities. The ] and part of the New Testament were translated at the school from Greek to Egyptian, which had already begun to be written in Greek letters with the addition of a number of demotic characters. This stage of the Egyptian language would later come to be known as ] along with its ]. The third theologian to head the Catachetical School was a native Egyptian by the name of ]. Origen was an outstanding theologian and one of the most influential ]. He traveled extensively to lecture in various churches around the world and has many important texts to his credit including the '']'', an ] of various translations of the ]. | |||

| ], ''c''. 1279–1213 BC.]] Throughout the Pharaonic epoch, divine kingship was the glue which held Egyptian society together. It was especially pronounced in the Old and Middle Kingdoms and continued until the Roman conquest. The societal structure created by this system of government remained virtually unchanged up to modern times.<ref>Grimal, p. 93</ref> The role of the king, however, was considerably weakened after the ]. The king in his role as Son of Ra was entrusted to maintain ], the principle of truth, justice and order. His job also entailed maintaining and enhancing the country's agricultural economy by ensuring regular annual ] floods on which the people depended for sustenance and their very livelihood. Ascendancy to the Egyptian throne reflected the myth of Horus who assumed kingship after he buried his murdered father ]. The king of Egypt, as a living personification of Horus, could claim the throne after burying his predecessor, who was typically his father. When the role of the king waned, the country became more susceptible to foreign influence and invasion. | |||

| At the threshold of the ] period, the New Testament had been entirely translated into Coptic. But while Christianity continued to thrive in Egypt, the old pagan beliefs which had survived the test of time were facing mounting pressure. The Byzantine period was particularly brutal in its zeal to erase any traces of ancient Egyptian religion. Under emperor ], Christianity had already been proclaimed the religion of the Empire and all pagan cults were forbidden. When Egypt fell under the jurisdiction of ] after the split of the Roman Empire, many ancient Egyptian temples were either destroyed or converted into monasteries.<ref>Kamil, p. 35</ref> | |||