| Revision as of 12:07, 30 August 2007 editJbdelaporte (talk | contribs)59 editsm →Migration Agents← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:05, 28 November 2024 edit undoMuaza Husni (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users4,798 edits →See also | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} <!-- "none" is preferred when the title is sufficiently descriptive; see ] --> | |||

| '''Immigration to Australia''' began at least 40,000 years ago, when the ancestors of ]s arrived on the continent via the islands of the ] and ]. ]ans began landing in the ] and ], and the continent was colonised by ] in 1788. | |||

| {{Use Australian English|date=January 2018}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2018}} | |||

| ] | |||

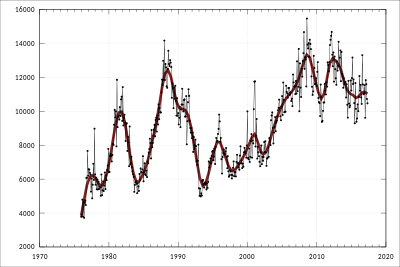

| The overall level of immigration has grown substantially during the last decade. Net overseas migration increased from 30,000 in 1993 <ref name="abs">Australian Bureau of Statistics, </ref> to 118,000 in 2003-04.<ref name="abs2">Australian Bureau of Statistics, </ref> The largest components of immigration are the skilled migration and family re-union programs. In recent years the ] of ]s ] has generated great levels of controversy. | |||

| ] | |||

| The Australian continent was first settled when ancestors of ] arrived via the islands of ] and ] over 50,000 years ago.<ref name="SMH_Origins2">{{cite news|url=https://www.smh.com.au/news/national/out-of-africa--aboriginal-origins-uncovered/2007/05/08/1178390312301.html|title=Out of Africa – Aboriginal origins uncovered|last=Smith|first=Debra|date=9 May 2007|newspaper=]|quote=Aboriginal Australians are descended from the same small group of people who left Africa about 70,000 years ago and colonised the rest of the world, a large genetic study shows. After arriving in Australia and New Guinea about 50,000 years ago, the settlers evolved in relative isolation, developing unique genetic characteristics and technology.|access-date=5 June 2008|archive-date=6 November 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121106051641/http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/out-of-africa--aboriginal-origins-uncovered/2007/05/08/1178390312301.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| During the 2004-05, total 123,424 people immigrated to Australia. Of them, 17,736 were from ], 54,804 from ], 21,131 from ], 18,220 from ], 1,506 from ], and 2,369 from ].<ref></ref> | |||

| European colonisation began in 1788 with the establishment of a ] ] in ]. Beginning in 1901, Australia maintained the ] for much of the 20th century, which forbid the entrance in Australia of people of non-European ethnic origins. Following ], the policy was gradually relaxed, and was abolished entirely in 1973. Since 1945, more than 7 million people have settled in Australia. | |||

| Between 1788 and the mid-20th century, the vast majority of settlers and immigrants came from Britain and Ireland (principally ], ] and ]), although there was significant immigration from ] and ] during the 19th century. In the decades immediately following World War II, Australia received a ] from across ], with many more immigrants arriving from ] and ] than in previous decades. Since the end of the ] in 1973, Australia has pursued an official policy of ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.immi.gov.au/facts/06evolution.htm|title=The Evolution of Australia's Multicultural Policy|access-date=18 September 2007|year=2005|publisher=Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060219130703/http://www.immi.gov.au/facts/06evolution.htm|archive-date=19 February 2006}}</ref> and there has been a large and continuing wave of immigration from across the world, with ] being the largest source of immigrants in the 21st century.<ref name="homeaffairs.gov.au">{{Cite web|url=https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/report-migration-program-2018-19.pdf|title=2018 – 19 Migration Program Report|date=30 June 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230406191145/https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/report-migration-program-2018-19.pdf|archive-date=6 April 2023|url-status=live|website=Department of Home Affairs}}</ref> In 2019–20, '''immigration to Australia''' came to a halt during the ], which in turn saw a shrinkage of the Australian population for the first time since World War I,<ref>{{cite web|title=Australia's population shrinks for the first time since WWI as COVID turns off immigration tap|work=ABC|date=24 March 2021|accessdate=14 April 2021|url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-03-24/population-declines-as-covid-border-closures-bite/13256938|archive-date=13 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210413233816/https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-03-24/population-declines-as-covid-border-closures-bite/13256938|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Australia's population has shrunk. What is the ideal population for this country?|work=ABC|date=25 March 2021|accessdate=14 April 2021|url=https://www.abc.net.au/radio/sydney/programs/afternoons/population/13276994|archive-date=12 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210412233446/https://www.abc.net.au/radio/sydney/programs/afternoons/population/13276994|url-status=live}}</ref> though in the following period 2021–22 showed a very strong recovery of migrant arrivals.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-12-16 |title=Overseas Migration, 2021-22 financial year {{!}} Australian Bureau of Statistics |url=https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/overseas-migration/latest-release |access-date=2022-12-25 |website=www.abs.gov.au |language=en |archive-date=25 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221225071241/https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/overseas-migration/latest-release |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| 131,000 people migrated to Australia in 2005-06<ref></ref> and migration target for 2006-07 was 144,000.<ref></ref> | |||

| Net overseas migration has increased from 30,042 in 1992–93<ref name="abs">Australian Bureau of Statistics, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200413184820/http://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/0BD75000987B71A0CA256F7200832F19?Open |date=13 April 2020 }}</ref> to 178,582 persons in 2015–16.<ref name="abs2">{{Cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3412.0Main%20Features52015-16?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3412.0&issue=2015-16&num=&view=|title=Australian Bureau of noms|access-date=21 April 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180707083017/http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3412.0Main%20Features52015-16?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3412.0&issue=2015-16&num=&view=|archive-date=7 July 2018|url-status=dead}}</ref> The largest components of ] are the skilled migration and family re-union programs. A 2014 sociological study concluded that: "Australia and Canada are the most receptive to immigration among western nations."<ref>Markus, Andrew. " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160623043715/http://jos.sagepub.com/content/50/1/10.full.pdf+html |date=23 June 2016 }}" Journal of Sociology 50.1 (2014): 10-22.</ref> In 2023, ] ranked Australia as the top country destination for individuals seeking to work and live a high-quality life based on global assessments.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-04-22 |title=Decoding Global Talent 2024: Dream Destinations and Mobility Trends |url=https://www.bcg.com/publications/2024/dream-destinations-and-talent-mobility-trends |website=BCG Global |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Immigration applications from offshore paper based applicants currently have a backlog of 8 months before they are processed; as of August 2007. The application process may change every three months due to legislation. It pays to keep abreast of changes to ensure your application has the best chance of success. When your application is received it is based on the legislation at that time, regardless of future changes in the next 8 months before your application is processed. On top of this 8 months your case worker may take several months to go through the application, request further documentation, or answers to questions, before a decision is made. The process can be quite lengthy. | |||

| == History == | |||

| {{main|Migratory history of Australia}} | |||

| Australia is a signatory to the ] and has resettled many ]. In recent years, Australia's policy of ] of ]s by boat has attracted controversy. | |||

| Human migration to the ]n continent was first achieved during the closing stages of the ] ], when sea levels were typically much lower than they are today. It is theorised that these ancestral peoples arrived via the nearest islands of the ], crossing over the intervening straits (which were then narrower) to reach the single landmass which then existed. Known as ], this landmass connected Australia with ] via a ] which emerged when prevailing glacial conditions lowered sea levels by some 100-150 ]. Australia's coastline also extended much further out into the ] than at present, affording another possible route by which these first peoples reached the continent. Estimates of the timing of these migrations vary considerably: the most widely-accepted conservative evidential view places this somewhere between 40,000 to 45,000 years ago, with earlier cited (but not universally accepted) dates of up to 60,000 years or more also proposed; the debate continues within the academic community. | |||

| == Immigration history of Australia == | |||

| On ], ], a date now celebrated as ], a landing was made by the British at ] for the purposes of establishing a colony. The new colony was formally proclaimed as the Colony of New South Wales on ]. | |||

| {{Main|Immigration history of Australia}} | |||

| The first ] of humans to the continent took place around 65,000 years ago<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200413184828/https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2017-11-17/when-did-australias-human-history-begin-conversation/9158202 |date=13 April 2020 }} ''ABC News'', 17 November 2017, Retrieved 17 November 2017.</ref> via the islands of ] and ] as part of the early ] out of Africa.<ref name="genographic.nationalgeographic.com">{{Cite web|url=https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/human-journey/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130114080014/https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/human-journey/|url-status=dead|archive-date=14 January 2013|title=Map of Human Migration}}</ref> | |||

| === Penal transportation === | |||

| The ], beginning in 1851, led to an enormous expansion in population, including large numbers of ] and ] settlers, followed by smaller numbers of ] and other Europeans, and ]. This latter group were subject to increasing restrictions and discrimination, making it impossible for many to remain in the country. With the Federation of the Australian colonies into a single nation, one of the first acts of the new Commonwealth Government was the ], otherwise known as the ], which was a strengthening and unification of disparate colonial policies designed to restrict non-White settlement. | |||

| {{Main|Convicts in Australia}} | |||

| ], 1792]] | |||

| European migration to Australia began with the British ] of ] on 26 January 1788. The ] comprised 11 ships carrying 775 convicts and 645 officials, members of the crew, marines, and their families and children. The settlers consisted of petty criminals, second-rate soldiers and a crew of sailors. There were few with skills needed to start a self-sufficient settlement, such as farmers and builders, and the colony experienced hunger and hardships. Male settlers far outnumbered female settlers. The ] arrived in 1790 bringing more convicts. The conditions of the transportation was described as horrific and worse than slave transports. Of the 1,026 convicts who embarked, 267 (256 men and 11 women) died during the voyage (26%); a further 486 were sick when they arrived of which 124 died soon after. The fleet was more of a drain on the struggling settlement than of any benefit. Conditions on the ], which followed on the heels of the Second Fleet in 1791, were a bit better. The fleet comprised 11 ships. Of the more than 2000 convicts brought onto the ships, 173 male convicts and 9 female convicts died during the voyage. Other transport fleets bringing further convicts as well as freemen to the colony would follow. By the end of the ] in 1868, approximately 165,000 people had entered Australia as convicts. | |||

| === Bounty Immigration === | |||

| After ], Australia launched a massive immigration programme, believing that having narrowly avoided a Japanese invasion, Australia must "populate or perish." Hundreds of thousands of displaced Europeans migrated to Australia and over 1,000,000 British Citizens immigrated under the Assisted Migration Scheme, colloquially becoming known as ]. | |||

| The colonies promoted migration by a variety of schemes. The Bounty Immigration Scheme (1835-1841) boosted emigration from the United Kingdom to New South Wales.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.angelfire.com/al/aslc/immigration.html|title=Australia's Early Immigration Schemes|website=]|access-date=23 September 2018|archive-date=2 April 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200402195742/http://www.angelfire.com/al/aslc/immigration.html|url-status=live}}</ref> The ] was established to encourage settlement in South Australia by labourers and skilled migrants. | |||

| During the 2001 election campaign, immigration and border protection became the hot issue, as a result of incidents such as the ], the ], ], and the sinking of the ]. This incident marked the beginning of the controversial ]. | |||

| === Gold rush and population growth === | |||

| {{Main|Australian gold rush}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] poster issued by the Overseas Settlement Office to attract immigrants (1928).]] | |||

| The ], beginning in 1851, led to an enormous expansion in population, including large numbers of British and Irish settlers, followed by smaller numbers of Germans, other Europeans, and ]. This latter group was subject to increasing restrictions and discrimination, making it impossible for many to remain in the country. With the federation of the Australian colonies into a single nation, one of the first acts of the new Commonwealth Government was the ], otherwise known as the ], which was a strengthening and unification of disparate colonial policies designed to restrict non-White settlement. Because of opposition from the British government, an explicit racial policy was avoided in the legislation, with the control mechanism being a dictation test in a European language selected by the immigration officer. This was selected to be one the immigrant did not know; the last time an immigrant passed a test was in 1909. Perhaps the most celebrated case was ], a left-wing Austrian journalist who could speak five languages, who was failed in a test in Scottish Gaelic and deported as illiterate. | |||

| The government also found that if it wanted immigrants, it had to subsidise migration. The great distance from Europe made Australia a more expensive and less attractive destination than Canada and the United States. The number of immigrants needed during different stages of the economic cycle could be controlled by varying the subsidy. Before ], assisted migrants received passage assistance from colonial government funds. The British government paid for the passage of convicts, paupers, the military, and civil servants. Few immigrants received colonial government assistance before 1831.<ref name="Price">{{cite book |last=Price |first=Charles |title=Australians: Historical Statistics |publisher=Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates |year=1987 |isbn=0-949288-29-2 |editor=Wray Vamplew |location=Broadway, New South Wales, Australia |pages=2–22 |chapter=Chapter 1: Immigration and Ethnic Origin}}</ref> However, young women were receiving assisted passages from state governments to migrate to Australia in the early years of Federation.<ref>{{Cite Q|Q118696098}}</ref> | |||

| ==Environmental, economic and social impacts== | |||

| There are a wide range of views in the Australian community on the composition and level of immigration, and on the possible effects of varying the level of immigration and ], some of which are based on empirical data, others more speculative in nature. In ], a ] population study entitled "Future Dilemmas", commissioned by ], outlined six potential dilemmas associated with immigration-driven population growth. These dilemmas included the absolute numbers of aged continuing to rise despite high immigration off-setting ageing and declining birth-rates in a proportional sense, a worsening of Australia's ] due to more imports and higher consumption of domestic production, increased green house gas emissions, overuse of agricultural soils, marine fisheries and domestic supplies of oil and gas, and a decline in urban air quality, river quality and biodiversity.<ref name="csiro">Foran, B., and F. Poldy, (2002), , CSIRO Resource Futures, Canberra. </ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center" | |||

| ==== Replacement ==== | |||

| |- | |||

| The ] in Australia has dropped over the last generation below replacement levels, meaning that without immigration, Australia's population would both age and decline, raising the question of long-term social and cultural sustainability. | |||

| !Period!!Annual average assisted immigrants<ref name = Price/> | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1831–1860 || 18,268 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1861–1900 || 10,087 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1901–1940 || 10,662 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1941–1980 || 52,960 | |||

| |} | |||

| With the onset of the ], the Governor-General proclaimed the cessation of immigration until further notice. The next group to arrive were 5,000 Jewish refugee families from Germany in 1938. Approved groups such as these were assured of entry by being issued a Certificate of Exemption from the Dictation Test. | |||

| In 2006, Treasurer ] warned Australians to increase their birth rate to replacement levels or run the risk of Australia's population composition being fundamentally transformed by immigration. Raising the spectre of social fragmentation and violence under a low birth rate, high immigration scenario, Costello cautioned that immigrants might not be absorbed successfully if the Australian-born population dwindled. He stated: "Increasing immigration to cover natural population decline will change the composition of our population and raise concerns about social dislocation." <ref name="popdecline">Oakes, L. (July 19, 2006) "It's the end of the world as we know it", National Nine News. Retrieved 04 June 2007 from http://news.ninemsn.com.au/article.aspx?id=117684</ref> | |||

| === Post-war immigration to Australia === | |||

| ==== Environment ==== | |||

| {{Main|Post-war immigration to Australia|New Australians}} | |||

| Some members of the Australian ], notably the organisation ], believe that as the driest inhabited continent, Australia cannot continue to sustain its current rate of population growth without becoming ]. SPA also argues that ] will lead to a deterioration of natural ecosystems through increased temperatures, extreme weather events and less rainfall in the southern part of the continent, thus reducing its capacity to sustain a large population even further. The ]-based ] supports the view that Australia is overpopulated, and believes that to maintain the current ] in Australia, the optimum population is 10 million, or 21 million with a reduced standard of living. Other members of the environment movement point out that Australians are, per capita, the highest users of water on the planet and the worst emitters of ], so any consideration of changes to ] needs to consider a broader context regarding appropriate use of resources independently of population. | |||

| ] arrived in Australia.]] | |||

| After ] Australia launched a massive ], believing that having narrowly avoided a Japanese invasion, Australia must "populate or perish". Hundreds of thousands of displaced Europeans migrated to Australia and over 1,000,000 British subjects immigrated under the ], colloquially becoming known as ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.abc.net.au/tv/guide/netw/200711/programs/ZY8804A001D1112007T203000.htm|title=Ten Pound Poms|date=1 November 2007|work=]|access-date=14 June 2009|archive-date=2 April 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200402195744/http://www.abc.net.au/tv/guide/netw/200711/programs/ZY8804A001D1112007T203000.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> The scheme initially targeted citizens of all Commonwealth countries; after the war it gradually extended to other countries such as the Netherlands and Italy. The qualifications were straightforward: migrants needed to be in sound health and under the age of 45 years. There were initially no skill restrictions, although under the ], people from mixed-race backgrounds found it very difficult to take advantage of the scheme.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://museumvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/discoverycentre/your-questions/ten-pound-poms/|title=Ten Pound Poms|date=10 May 2009|work=]|access-date=14 June 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100117183339/http://museumvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/discoverycentre/your-questions/ten-pound-poms/|archive-date=17 January 2010|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Housing ==== | |||

| Some claim that Australia's recent level of immigration has (along with natural population growth and other economic factors) contributed to a widespread shortage of affordable housing, particularly in the major cities.<ref name="pp">People & Place Volume 11, Issue 3 (2003), , Birrell, B. and Healy, E</ref> A number of economists, such as ] analyst Rory Robertson, assert that high immigration and the propensity of new arrivals to cluster in the capital cities is exacerbating the nation's housing affordability problem.<ref name="lo">Klan, A. (March 17, 2007) </ref> According to Robertson, Federal Government policies that fuel demand for housing, such as the currently high levels of immigration but also capital gains tax discounts, have had a greater impact on housing affordability than land release on urban fringes.<ref name="wade">Wade, M. (September 9, 2006) </ref> However, the ] does not accept "population pressures" as a major driver of strong increases in house prices, stating that "increased demand for better quality and better located dwellings, rather than for more dwellings, has been the primary driver".<ref name="pc">Productivity Commission, , p.63 (final par.) & p.68</ref>. Furthermore, demographer ] has argued that Australian cities are among the least affordable in the world due to government policies of ]<ref>http://www.demographia.com/dhi-ix2005q3.pdf</ref>. | |||

| In 1973, ] largely displaced cultural selectivity in ]. | |||

| ==== Employment ==== | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center" | |||

| According to one researcher, there are thousands of low-cost IT workers entering Australia who are undermining the job prospects of new computer science graduates and reducing salaries in the IT industry.<ref name="afr">Australian Financial Review 7/7/04, “Immigrants taking local IT jobs: report”</ref> However, other research sponsored by DIAC has found that Australia’s structured labour market along with the larger number of immigrants with higher education levels has tended to raise employment levels for Australians who are relatively unskilled.<ref name="garnaut2003">DIMA research publications (Garnaut), , p.21</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| !Period!!Migration programme<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.border.gov.au/about/corporate/information/fact-sheets/02key |title=Fact sheet - Key facts about immigration |access-date=18 April 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150912192513/http://www.border.gov.au/about/corporate/information/fact-sheets/02key |archive-date=12 September 2015 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BN/1011/AustMigration|title=Australia's Migration Program|publisher=Parliament of Australia|website=www.aph.gov.au|access-date=13 June 2018|archive-date=13 June 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180613134026/https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BN/1011/AustMigration|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1998–99 || 68 000 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1999–00 || 70 000 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2000–01 || 76 000 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2001–02 || 85 000 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2002–03 || 108,070 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2003–2004 || 114,360 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2004–2005 || 120,060 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2005 || 142,933 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2006 || 148,200 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2007 || 158,630 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2008 || 171,318 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2011 || 185,000 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2012 || 190,000 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2013 || 190,000<ref>https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/report-migration-programme-2013-14.pdf {{Bare URL PDF|date=August 2024}}</ref><ref>https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-statistics/statistics/visa-statistics/live/migration-program {{Bare URL inline|date=August 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2015-2016 || 190,000<ref>https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/2015-16-migration-programme-report.pdf {{Bare URL PDF|date=August 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2016-2017 || 190,000<ref>https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/report-on-migration-program-2016-17.pdf {{Bare URL PDF|date=August 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2017-2018 || 190,000<ref>https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/report-migration-program-2017-18.pdf {{Bare URL PDF|date=August 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2018-2019 || 190,000<ref>https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/report-migration-program-2018-19.pdf {{Bare URL PDF|date=August 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | 2023-2024 || 190,000<ref>https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/what-we-do/migration-program-planning-levels#:~:text=In%20the%202024%E2%80%9325%20Migration,21%20and%202021%E2%80%9322%20respectively. {{Bare URL inline|date=August 2024}}</ref> | |||

| |} | |||

| === Overview === | |||

| Australian ]s have sometimes exposed attempts by employers to introduce foreign workers into the country in order to avoid paying local workers higher wages.<ref name="ln">LaborNET </ref> The government's policy of ], especially regarding the impact upon children, has come under criticism from a range of religious, community and political groups including the ], ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |+Foreign-born Australian residents by country of birth<ref>{{Cite web|last=Commonwealth Parliament|first=Canberra|title=Population and migration statistics in Australia|url=https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1819/Quick_Guides/PopulationStatistics|access-date=2020-07-22|website=www.aph.gov.au|language=en-AU|archive-date=3 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200803154740/https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1819/Quick_Guides/PopulationStatistics/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| !'''#''' | |||

| ! colspan="2" |1901 | |||

| ! colspan="2" |1954 | |||

| ! colspan="2" |2016 | |||

| |- | |||

| |1. | |||

| |{{flagicon|UK}} ] | |||

| |495 504 | |||

| |{{flagicon|UK}} ] | |||

| |616 532 | |||

| |{{flagicon|UK}} ] | |||

| |1 087 756 | |||

| |- | |||

| |2. | |||

| |{{flagicon|UK}} ] | |||

| |184 085 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Italy}} ] | |||

| |119 897 | |||

| |{{flagicon|New Zealand}} ] | |||

| |518 462 | |||

| |- | |||

| |3. | |||

| |{{flagicon|German Empire}} ] | |||

| |38 352 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Germany}} ] | |||

| |65 422 | |||

| |{{flagicon|China}} ] | |||

| |509 558 | |||

| |- | |||

| |4. | |||

| |{{flagicon|Qing Empire}} ] | |||

| |29 907 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Poland}} ] | |||

| |56 594 | |||

| |{{flagicon|India}} ] | |||

| |455 385 | |||

| |- | |||

| |5. | |||

| |{{flagicon|UK}} ] | |||

| |25 788 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Netherlands}} ] | |||

| |52 035 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Philippines}} ] | |||

| |232 391 | |||

| |- | |||

| |6. | |||

| |{{flagicon|Sweden|1844}}{{flagicon|Norway|1901}} ] | |||

| |9 863 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Ireland}} ] | |||

| |47 673 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Vietnam}} ] | |||

| |219 351 | |||

| |- | |||

| |7. | |||

| |{{flagicon|UK}} ] | |||

| |9 128 | |||

| |{{flagicon|New Zealand}} ] | |||

| |43 350 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Italy}} ] | |||

| |174 042 | |||

| |- | |||

| |8. | |||

| |{{flagicon|British Raj}} ] | |||

| |7 637 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Greece|old}} ] | |||

| |25 862 | |||

| |{{flagicon|South Africa}} ] | |||

| |162 450 | |||

| |- | |||

| |9. | |||

| |{{flagicon|USA}} ] | |||

| |7 448 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Yugoslavia}} ] | |||

| |22 856 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Malaysia}} ] | |||

| |138 363 | |||

| |- | |||

| |10. | |||

| |{{flagicon|Denmark}} ] | |||

| |6 281 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Malta|colonial}} ] | |||

| |19 988 | |||

| |{{flagicon|Sri Lanka}} ] | |||

| |109 850 | |||

| |- | |||

| | - | |||

| |Other | |||

| |47 463 | |||

| |Other | |||

| |215 589 | |||

| |Other | |||

| |2 542 443 | |||

| |} | |||

| ==Current immigration programs== | |||

| ==== Economy ==== | |||

| The ], ] considers that Australia is underpopulated due to a low birth rate, and claims that negative population growth will have adverse long-term effects on the economy as the population ages and the labour market becomes less competitive<ref>http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/costello-hatches-censustime-challenge-procreate-and-cherish/2006/07/24/1153593272565.html</ref>. To avoid this outcome the government has increased immigration to fill gaps in labour markets and introduced a subsidy to encourage families to have more children. However, opponents of population growth such as Sustainable Population Australia do not accept that population growth will decline and reverse, based on current immigration and fertility projections.<ref name="Goldie">Goldie, J. (23 February 2006) (retrieved 30 October 2006)</ref> In terms of using immigration to offset an aging workforce, a 1999 parliamentary research paper entitled "Population Futures for Australia: the Policy Alternatives" concluded: "It is demographic nonsense to believe that immigration can help to keep our population young." <ref name="PFFAPA">McDonald, P., Kippen, R. (1999) </ref> | |||

| === Migration program === | |||

| ] claims that the Liberal Party's focus on skilled migration has reduced the average age of migrants. "More than half are aged 15 to 34, compared with 28 per cent of our population. Only 2 per cent of permanent immigrants are 65 or older, compared with 13 per cent of our population."<ref>http://www.smh.com.au/news/opinion/backscratching-at-a-national-level/2007/06/12/1181414298095.html</ref> Because of these statistics, Gittens claims that immigration is slowing the ageing of the Australian population. He also claims that the emphasis on skilled migration also means that the "net benefit to the economy is a lot more clear-cut." Even though Gittens suggests that skilled workers add more to the economy, there are those who acknowledge the importance of unskilled migrants. Treasurer Eric Ripper claims that in Australia "several major capital works projects had to be put on hold because there were not enough skilled and unskilled workers."<ref>http://theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,20867,21709159-12332,00.html?from=public_rss</ref> | |||

| {{see also|Australian permanent resident}} | |||

| ] dedicated to immigrants in Australia]] | |||

| There are a number of different types of Australian immigration, classed under different categories of visa:<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/trav/visa-1/Visa-listing|title=Visa listing|author=Australian Government. Department of Home Affairs|access-date=23 January 2018|archive-date=23 January 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180123190415/https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/trav/visa-1/Visa-listing|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Chapman and Cobb-Clark believe that "immigrant spending from past savings will increase the demand for labour and create job vacancies".<ref name="er2">Chapman, B. and Cobb-Clark, D. (1999). A comparative static model of the relationship between immigration and the short-run job prospects of unemployed residents. , Vol. 75, pp. 358-368.</ref> However, immigration also increases the supply of labour and the number of people applying for job vacancies. | |||

| * '''Skilled Occupation visas''' - Australian working visas are most commonly granted to highly skilled workers. Candidates are assessed against a points-based system, with points allocated for certain standards of education. These visas are often sponsored by individual States, which recruit workers according to specific needs. Visas may also be granted to applicants sponsored by an Australian business. The most popular form of sponsored working visa was the ] set in place in 1996 which has now been abolished by the Turnbull government. | |||

| * '''Student visas''' - The Australian Government actively encourages foreign students to study in Australia. There are a number of categories of a student visa, most of which require a confirmed offer from an educational institution. | |||

| * '''Family visas''' - Visas are often granted on the basis of family ties in Australia. There are a number of different types of Australian family visas, including Contributory Parent visas, Child Visa and Partner visas. | |||

| * '''Working holiday visa''' - This visa is a residence permit allowing travelers to undertake employment (and sometimes study) in the country issuing the visa to supplement education. | |||

| Employment and family visas can often lead to Australian citizenship; however, this requires the applicant to have lived in Australia for at least four years with at least one year as a ]. | |||

| Using ], Addison and Worswick found that “there is no evidence that immigration has negatively impacted on the wages of young or low-skilled natives.” Furthermore, Addison's study found that immigration did not increase unemployment among native workers. Rather, immigration decreased unemployment.<ref name="er">Addison, T. and Worswick, C. (2002). The impact of immigration on the earnings of natives: Evidence from Australian micro data. , Vol. 78, pp. 68-78.</ref> The evidence from the Economic Record runs counter to the common view that immigration adds only to labour supply and reduces wages. Economic empirical data show that immigrants not only add to labour supply but also to labour demand. Whether labour demand increase is greater than labor supply increase after immigration is an empirical issue. When the magnitude of change in aggregate labour supply is much greater than the magnitude of change in aggregate labour demand as a result of increased immigration then immigration can cause wages to decrease. Analysis by Garnaut shows this<ref name="garnaut2003" />. | |||

| * '''Investor visas''' - Foreign investors could invest the business or fund in Australia to acquire the Permanent Residential of Australia, after 4 years (including the year which acquire the visa), they need to take the exam and make a declaration in order to be a citizen of Australia.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url = http://www.visabureau.com/australia/default.aspx | |||

| | title = Australia visas | |||

| | date = 22 December 2011 | |||

| | access-date = 22 December 2011 | |||

| | author = Australian Visa Bureau | |||

| | archive-date = 1 January 2012 | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120101134140/http://www.visabureau.com/australia/default.aspx | |||

| | url-status = live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Claims have been made that Australia's migration program is in conflict with anti age-discrimination legislation and there have been calls to remove or amend the age limit of 50 for general skilled migrants.<ref>{{cite news |title=How old is too old to become a migrant? |url=https://www.sbs.com.au/news/how-old-is-too-old-to-become-a-migrant |access-date=27 April 2020 |agency=SBS News |date=26 August 2013 |archive-date=9 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210309023447/https://www.sbs.com.au/news/how-old-is-too-old-to-become-a-migrant |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In ] the ] launched a commissioned study entitled "Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth",<ref name="PC index">http://www.pc.gov.au/study/migrationandpopulation/index.html</ref> and released an initial position paper on 17 January 2006<ref name="pc3">Productivity Commission, , p.73</ref> which states that the increase of income per capita provided by higher migration (50% more than the base model) by the 2024-2025 financial year would be $335 (0.6%), an amount described as "very small". The paper also found that Australians would on average work 1.3% longer hours, about twice the proportional increase in income.<ref name="pc2">Productivity Commission, </ref>. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |+New permanent migrants to Australia by region (2016–17)<ref>{{Cite web|last=Liddy|first=Matt|date=2018-08-20|title=Chart of the day: Where do migrants to Australia come from?|url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-08-20/where-do-migrants-to-australia-come-from-chart/10133560|access-date=2020-07-22|website=ABC News|language=en-AU|archive-date=11 April 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200411035512/https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-08-20/where-do-migrants-to-australia-come-from-chart/10133560|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| !Region | |||

| !Number of migrants | |||

| |- | |||

| |Southern and Central Asia | |||

| |58,232 | |||

| |- | |||

| |North-East Asia | |||

| |37,235 | |||

| |- | |||

| |South-East Asia | |||

| |31,488 | |||

| |- | |||

| |North Africa and the Middle East | |||

| |28,525 | |||

| |- | |||

| |North-West Europe | |||

| |25,174 | |||

| |- | |||

| |Oceania and Antarctica | |||

| |16,445 | |||

| |- | |||

| |Sub-Saharan Africa | |||

| |11,369 | |||

| |- | |||

| |Americas | |||

| |9,687 | |||

| |- | |||

| |Southern and Eastern Europe | |||

| |7,306 | |||

| |- | |||

| |Supplementary and Not Stated | |||

| |492 | |||

| |} | |||

| In a study in the Australian Economic Review, Junankar finds that during the 1980s the Hawke Government’s decision not to decrease immigration lowered the unemployment rate<ref name="aer">Junankar, P., Pope, D. and Withers, G. (1998). Immigration and the Australian macroeconomy: Perspective and prospective. , Vol. 31, pp. 435-444.</ref>. | |||

| ===Humanitarian program=== | |||

| Gittens claims there is considerable opposition to immigration to Australia by "battlers" because of the belief that immigrants will steal jobs. Gittens claims though that "it's true that immigrants add to the supply of labour. But it's equally true that, by consuming and bringing families who consume, they also add to the demand for labour - usually by more."<ref>http://www.smh.com.au/news/opinion/backscratching-at-a-national-level/2007/06/12/1181414298095.html</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Asylum in Australia}} | |||

| Australia grants two types of visa under its humanitarian program:<ref>{{Cite web|url= http://www.border.gov.au/Trav/Refu/Offs|title= Offshore - Resettlement|website= www.border.gov.au|access-date= 2017-01-02|archive-date= 21 January 2017|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170121133852/http://www.border.gov.au/Trav/Refu/Offs|url-status= live}}</ref> | |||

| * Refugee-category visas for refugees under the ] | |||

| ==== Infrastructure ==== | |||

| * Special Humanitarian Programme (SHP) visas for persons who are subject to substantial discrimination amounting to gross violation of their human rights in their home country | |||

| Individuals and interest groups such as ] filed submissions in response to the Productivity Commission's position paper, arguing amongst other things that immigration causes a decline in wealth per capita and leads to environmental degradation and overburdened infrastructure, the latter creating a costly demand for new infrastructure.<ref name="er3">Claus, E (2005) (submission 12 to the Productivity Commission's position paper on Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth).</ref><ref name="er4">Nilsson (2005) (submission 9 to the Productivity Commission's position paper on Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth).</ref> However, the Productivity Commission's final research report found that it was not possible to reliably assess the impact of environmental limitations upon productivity and economic growth, nor to reliably attribute the contribution of immigration to any such impact.<ref name="PC final">Productivity Commission, , p.119</ref> | |||

| The cap for visas granted under the humanitarian program was 13,750 for 2015–16,<ref>{{Cite web|url= https://www.border.gov.au/Trav/Refu/Offs/The-Special-Humanitarian-Programme-(SHP)|title= The Special Humanitarian Programme (SHP)|website= www.border.gov.au|access-date= 2017-01-02|archive-date= 3 January 2017|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170103002531/https://www.border.gov.au/Trav/Refu/Offs/The-Special-Humanitarian-Programme-(SHP)|url-status= live}}</ref> plus an additional 12,000 visas available for refugees from the ].<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| Australia is a relatively high-immigration country like Canada (the country with the highest per capita immigration rate in the world, see ]) and the ], and while other economically developed countries like Japan have historically had negligible immigration<ref>http://www.opinionjournal.com/extra/?id=110008892</ref>, the issue of ] is forcing a rethink of such policies. | |||

| |url= https://www.border.gov.au/Trav/Refu/response-syrian-humanitarian-crisis | |||

| |title= Australia's response to the Syrian and Iraqi humanitarian crisis | |||

| |website= www.border.gov.au | |||

| |access-date= 2017-01-02 | |||

| |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20170321233214/https://www.border.gov.au/Trav/Refu/response-syrian-humanitarian-crisis | |||

| |archive-date= 21 March 2017 | |||

| |url-status= dead | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| == |

===Migration and settlement services=== | ||

| Both major Australian political parties favour a relatively high level of immigration. When ] became Prime Minister, net migration was rising, and the upward trend in the number of immigrants has increased over the decade since he took office. According to Banham, Australian political leaders who support higher immigration include ], John Howard, ], ], and ], with vocal opposition to immigration coming from former New South Wales premier ] who cites environmental reasons for his opposition.<ref name="uk3">Banham, C. (2004, April 2). Door opens to 6000 more immigrants. Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved October 2 from http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2004/04/01/1080544631282.html</ref> Peter Costello believes that high population growth in Australia is important for economic growth.<ref>http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2006/07/24/1153593271730.html?from=top5</ref> | |||

| The Australian Government and the community{{which|date=January 2019}} provide a number of migration-assistance and settlement-support services: | |||

| An anti-immigration party, the ], was formed by ] in the late 1990s. The party enjoyed significant electoral success for a while, most notably in its home state of ], but is now electorally marginalized. One Nation argued for a zero net immigration policy, asserting that "environmentally Australia is near her carrying capacity, economically immigration is unsustainable and socially, if continued as is, will lead to an ethnically divided Australia." <ref></ref> | |||

| * The ], available to eligible migrants from the humanitarian, family and skilled-visa streams, provides free English-language courses for those who do not have functional English. Up to 510 hours of English language courses are provided during the first five years of settlement in Australia. | |||

| * The Department of Home Affairs operates a 24-hour, seven-days-a-week telephone-based interpreting service called the Translating and Interpreting Service National, which facilitates contact between non-English speakers and interpreters, enabling access to government and community services.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.directory.gov.au/portfolios/home-affairs/department-home-affairs|title=Department of Home Affairs|date=25 May 2017|website=www.directory.gov.au|access-date=27 June 2018|archive-date=27 June 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180627183123/https://www.directory.gov.au/portfolios/home-affairs/department-home-affairs|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| * The Settlement Grants Program provides funding to assist humanitarian entrants and migrants settle in Australia and to participate equitably in Australian society as soon as possible after arrival. The program is targeted to deliver settlement services to humanitarian entrants, family migrants with low levels of English proficiency and dependants of skilled migrants in rural and regional areas with low English-proficiency. | |||

| * The Australian Cultural Orientation program provides practical advice and the opportunity to ask questions about travel to and life in Australia to refugee and humanitarian visa holders who are preparing to settle in Australia. The program is delivered overseas over five days before the visa holder begins his or her journey.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/lega/lega/form/immi-faqs/what-is-the-australian-cultural-orientation-program |title=What is the Australian Cultural Orientation program? |access-date=1 April 2018 |archive-date=1 April 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180401144744/https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/lega/lega/form/immi-faqs/what-is-the-australian-cultural-orientation-program |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| * Refugee and humanitarian visa holders are also eligible to receive on-arrival settlement support through the Humanitarian Settlement Services program, which provides intensive settlement-support and equips individuals with the skills and knowledge to independently access services beyond the initial settlement period.<ref>{{cite web| url = https://www.dss.gov.au/settlement-and-multicultural-affairs/programs-policy/settlement-services/humanitarian-settlement-program| url-status = dead| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20180323030656/https://www.dss.gov.au/settlement-and-multicultural-affairs/programs-policy/settlement-services/humanitarian-settlement-program| archive-date = 2018-03-23| title = Humanitarian Settlement Program {{!}} Department of Social Services, Australian Government}}</ref> | |||

| * The Immigration Advice and Application Assistance Scheme provides professional assistance, free of charge, to disadvantaged visa-applicants, to help with the completion and submission of visa applications, liaison with the department,{{which|date=January 2019}} and advice on complex immigration matters. It also provides migration advice to prospective visa-applicants and sponsors.<ref>{{cite web| url = https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/about/corporate/information/fact-sheets/63advice| url-status = dead| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20180211013740/http://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/about/corporate/information/fact-sheets/63advice| archive-date = 2018-02-11| title = Fact sheet - Immigration Advice and Application Assistance Scheme (IAAAS)}}</ref> | |||

| * In response to the needs of asylum seekers, the Asylum Seeker Assistance Scheme was established{{by whom|date=January 2019}} in 1992 to address Australia's obligations under the ]. The Australian Red Cross administers the scheme under contract to the Department of Immigration and Citizenship. It provides financial assistance to asylum seekers in the community who satisfy specific eligibility criteria, and also facilitates access to casework assistance and to other support services for asylum seekers through the Australian Red Cross.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.immi.gov.au/media/fact-sheets/66hss.htm |title=Australian Immigration Fact Sheet 66. Humanitarian Settlement Services<!-- Bot generated title --> |access-date=23 October 2012 |archive-date=3 November 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121103235036/http://www.immi.gov.au/media/fact-sheets/66hss.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * A variety of community-based services cater to the needs of newly-arrived migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. Some of these services, such as ]s, receive funding from the Commonwealth Government. | |||

| == Country of birth of Australian residents == | |||

| Commentators such as Ross Gittens, a columnist at ''The Age'' accuse John Howard of deception, by appearing "tough" on illegal immigration to win support from the working class while simultaneously winning support from employers with high legal immigration.<ref name="uk2">Gittens, R. (2003, August 20). Honest John's migrant twostep. The Age. Retrieved October 2 from http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2003/08/19/1061261148920.html</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Foreign-born population of Australia}} | |||

| {{As of | 2019}}, 30% of the Australian resident population, or 7,529,570 people, had been born overseas.<ref name="auto">{{cite web|url= https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/log?openagent&34120do005_201819.xls&3412.0&Data%20Cubes&B95CDCBDF3B53509CA25855700002DC2&0&2018-19&28.04.2020&Latest|title= Table 5.1 Estimated resident population, by country of birth(a), Australia, as at 30 June, 1996 to 2019(b)(c)|publisher= Australian Bureau of Statistics|access-date= 4 May 2020|archive-date= 2 July 2021|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20210702055137/https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/migration-australia/latest-release|url-status= live}}</ref> | |||

| The following table shows Australia's population by country of birth as estimated by the ] in 2020. It shows only countries or regions or birth with a population of over 100,000 residing in Australia. | |||

| <!-- The following statement is incorrect. The linked article only suggests Latham wanted to divert migrants to regional areas, not reduce the overall level of immigration. Former Labor leader Mark Latham wanted to take a tougher line on migration <ref name="uk4"></ref> but in 2001 the Labor Party was defeated in elections by John Howard's Liberal-National Coalition. --> | |||

| In 2006, the Labor Party under Kim Beazley took a stance against the importation of increasingly large numbers of temporary migrant workers ("foreign workers") by employers, arguing that this is simply a way for employers to drive down wages.<ref name="ER">, Background Briefing, Radio National Sunday 18 June 2006</ref>. At the same time, it is estimated that a million Australians are employed outside Australia<ref>http://www.abc.net.au/rn/backgroundbriefing/stories/2006/1662023.htm#transcript “Workers of the World”], Background Briefing, Radio National Sunday 18 June 2006</ref>. | |||

| {| class="wikitable plainrowheaders" style="text-align:right" | |||

| Ross Gittens claims that "a central element in John Howard's outstanding political success has been his ability to attract the votes of people in modest circumstances whom you'd normally expect to be Labor voters - Howard's battlers."<ref>http://www.theage.com.au/news/Ross-Gittins/Howards-battlers-may-not-be-that-loyal/2005/03/08/1110160824800.html</ref> However, issues of ] and ] before the ] are being blamed for the Liberal Party's slump in opinion polls<ref>http://www.wsws.org/articles/2007/jun2007/sep-j22.shtml</ref>. | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="col" colspan="2" | Source: ] (2020)<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/migration-australia/2019-20/34120DO005_201920.xls|title=Table 5.1 Estimated resident population, by country of birth(a), Australia, as at 30 June, 1996 to 2020(b)(c)|publisher=Australian Bureau of Statistics|accessdate=24 April 2021|archive-date=16 July 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220716010533/https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/migration-australia/2019-20/34120DO005_201920.xls|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! scope="col" | Place of birth | |||

| ! scope="col" | Estimated resident population{{efn-ua|Only countries with 100,000 or more are listed here.}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| ''Total ]'' | |||

| | ''18,043,310'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| ''Total foreign-born'' | |||

| | ''7,653,990'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|England}} ] | |||

| | 980,360 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|India}} ] | |||

| | 721,050 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|Mainland China}} ]{{efn-ua|The Australian Bureau of Statistics lists ], ] and the Special Administrative Regions of ] and ] separately.}} | |||

| | 650,640 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|New Zealand}} ] | |||

| | 564,840 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|Philippines}} ] | |||

| | 310,050 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|Vietnam}} ] | |||

| | 270,340 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|South Africa}} ] | |||

| | 200,240 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|Italy}} ] | |||

| | 177,840 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|Malaysia}} ] | |||

| | 177,460 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|Sri Lanka}} ] | |||

| | 146,950 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|Scotland}} ]{{efn-ua|The Australian Bureau of Statistics source lists England and Scotland separately although they are both part of the ].}} | |||

| | 132,590 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|Nepal}} ] | |||

| | 131,830 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|South Korea}} ] | |||

| | 111,530 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|Germany}} ] | |||

| | 111,030 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|United States}} ] | |||

| | 110,160 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|Hong Kong}} ] ]{{efn-ua|In accordance with the Australian Bureau of Statistics source, ], ] and the Special Administrative Regions of ] and ] are listed separately.}} | |||

| | 104,760 | |||

| |- | |||

| | scope="row" style="text-align:left;"| {{flagicon|Greece}} ] | |||

| | 103,710 | |||

| |} | |||

| {{notelist-ua}} | |||

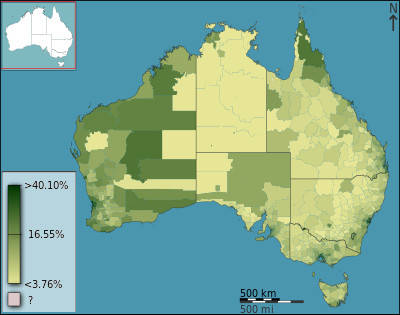

| The separate Australian States show some differences in settlement patterns, as demonstrated in the statistics compiled during the ]:<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/ProductSelect?newproducttype=Census+Tables&btnSelectProduct=Select+Location+or+Topic+%3E&collection=Census&period=2006&areacode=&geography=&method=&productlabel=&producttype=&topic=&navmapdisplayed=true&javascript=true&breadcrumb=P&topholder=0&leftholder=0¤taction=201&action=601&textversion=false |title= 2006 Census Data : View by Location Or Topic |publisher= Censusdata.abs.gov.au |access-date= 14 July 2011 |archive-date= 24 March 2012 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20120324233830/http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/ProductSelect?newproducttype=Census+Tables&btnSelectProduct=Select+Location+or+Topic+%3E&collection=Census&period=2006&areacode=&geography=&method=&productlabel=&producttype=&topic=&navmapdisplayed=true&javascript=true&breadcrumb=P&topholder=0&leftholder=0¤taction=201&action=601&textversion=false |url-status= dead }}</ref> | |||

| ACNielsen polling in March 2007 showed 53% of respondents preferred ] as Prime Minister compared to ] on 39%, and Labor on 61% of the two party preferred vote to the Coalition's 39%. Rudd's personal approval rating of 67% makes him the most popular opposition leader in the poll's 35 year history, with Newspoll two party preferred polling the highest in its history.<ref>http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/its-going-to-be-a-ruddslide/2007/03/11/1173548022964.html</ref> | |||

| * ] had the largest population, and the largest foreign-born population, in Australia (1,544,023). Certain nationalities concentrated notably in this state: 74.5% of ], 63.1% of ], 63.0% of ], 59.4% of ], and 59.4% of ] Australian residents lived in New South Wales. | |||

| * ], the second-most populous state, also had the second-largest number of overseas-born persons (1,161,984). 50.6% of ], 50.1% of ], 49.4% of ] and 41.6% of ] Australian residents lived in Victoria. | |||

| * ], with 528,827 overseas-born residents, had the highest proportion of foreign-born population. The state attracted 29.6% of all ] Australian residents, and narrowly trailed ] in having the largest population of ] Australian residents. | |||

| * ] had 695,525 overseas-born residents, and attracted the greatest proportion of persons born in ] (52.4%) and in ] (38.2%). | |||

| ==Impacts and concerns== | |||

| Some political commentators believe the Liberal Party's slump in the polls is due to environmental issues (Roy Morgon Research claims that 71% of Australians believe the Government should act immediately to address the consequences of global warming<ref>http://www.roymorgan.com/news/polls/2006/4013/</ref>). Gittens points to issues of immigration and industrial relations, claiming that "Howard is under considerable pressure to make changes that advantage business and high-income earners but disadvantage ordinary workers."<ref>http://www.smh.com.au/news/opinion/backscratching-at-a-national-level/2007/06/12/1181414298095.html</ref> | |||

| There are a range of views in the Australian community on the composition and level of immigration, and on the possible effects of varying the level of immigration and ]. | |||

| In 2002, a ] population study commissioned by the former ], outlined six potential dilemmas associated with immigration-driven population growth. These included: the absolute numbers of aged residents continuing to rise despite high immigration off-setting ageing and declining birth-rates in a proportional sense; a worsening of Australia's ] due to more imports and higher consumption of domestic production; increased ]; overuse of agricultural soils; marine fisheries and domestic supplies of oil and gas; and a decline in urban air quality, river quality and biodiversity.<ref name="csiro">Foran, B., and F. Poldy, (2002), {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101105070515/http://www.cse.csiro.au/publications/2002/fulldilemmasreport02-01.pdf |date=5 November 2010 }}, CSIRO Resource Futures, Canberra.</ref> | |||

| ==Migration Agents== | |||

| Under Australian law (Migration Act 1958<ref></ref>, Part 3) any person who gives what is called "immigration assistance" for a fee must in most cases be a Registered Migration Agent. The term "immigration assistance" is defined in section 276 of the Act to cover using, or purporting to use, knowledge of or experience in migration procedure to advise or assist various people with visa applications and related sponsorships, appeals, etc. | |||

| ===Environment=== | |||

| The legislation appoints an organisation called the Migration Institute of Australia Limited (MIA) to function as the Migration Agents Registration Authority (MARA) which is charged with maintaining a register of migration agents and carrying out a variety of functions under the Act in relation to supervision and discipline of agents. The register can be accessed on the internet<ref></ref>. | |||

| ] at night from the ], showing its ]]] | |||

| Some ]s believe that as the driest inhabited continent, Australia cannot continue to sustain its current rate of population growth without becoming ]. The ] (SPA) argues that ] will lead to a deterioration of natural ecosystems through increased temperatures, extreme weather events and less rainfall in the southern part of the continent, thus reducing its capacity to sustain a large population even further.<ref>{{cite web|title=Baby Bonus Bad for Environment |url=http://www.population.org.au/media/mediarels/mr20061023.pdf |website=population.org.au |publisher=Sustainable Population Australia |access-date=20 May 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080627115015/http://www.population.org.au/media/mediarels/mr20061023.pdf |archive-date=27 June 2008 }}</ref> The ] has concluded that Australia's ] has been one of the main factors driving growth in domestic greenhouse gas emissions.<ref name=":1" /> It concluded that the average emissions per capita in the countries that immigrants come from is only 42 percent of average emissions in Australia, finding that as immigrants alter their lifestyle to that of Australians, they increase global greenhouse gas emissions.<ref name=":1">{{cite web |url=http://www.tai.org.au/index.php?option=com_remository&Itemid=36&func=fileinfo&id=47 |title=Population Growth and Greenhouse Gas Emissions |publisher=Tai.org.au |date=10 July 2011 |access-date=14 July 2011 |archive-date=8 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200808233615/https://www.tai.org.au/index.php?Itemid=36&func=fileinfo&id=47&option=com_remository |url-status=live }}</ref> The Institute calculated that each additional 70,000 immigrants will lead to additional emissions of 20 million tonnes of greenhouse gases by the end of the Kyoto target period (2012) and 30 million tonnes by 2020.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.tai.org.au/index.php?option=com_remository&Itemid=36&func=fileinfo&id=876 |title=High Population Policy Will Double Greenhouse Gas Growth |publisher=Tai.org.au |date=10 July 2011 |access-date=14 July 2011 |archive-date=8 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200808164736/https://www.tai.org.au/index.php?Itemid=36&func=fileinfo&id=876&option=com_remository |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Housing and infrastructure=== | |||

| In the United Kingdom the Office of the Immigration Services Commissioner (OISC) performs a similar function to the MARA, as does the Canadian Society for Immigration Consultants (CSIC) in Canada. However, in both countries practising lawyers are regulated by their own professional bodies. In the United States, only practising lawyers may perform such functions. Australia is the only country which imposes a regime of dual regulation on lawyers working in the area of immigration law. | |||

| A number of economists, such as ] analyst Rory Robertson, assert that high immigration and the propensity of new arrivals to cluster in the capital cities is exacerbating the nation's ] problem.<ref name="lo">Klan, A. (17 March 2007) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081022125344/http://theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,20867,21376192-25658,00.html |date=22 October 2008 }}</ref> According to Robertson, Federal Government policies that fuel demand for housing, such as the currently high levels of immigration, as well as capital gains tax discounts and subsidies to boost fertility, have had a greater impact on housing affordability than land release on urban fringes.<ref name="wade">Wade, M. (9 September 2006) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171019215927/http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/pm-wrong-on-house-prices/2006/09/08/1157222334155.html |date=19 October 2017 }}</ref> | |||

| The ] in its 2004 Inquiry Report No. 28, ''First Home Ownership'', concluded: "Growth in immigration since the mid-1990s has been an important contributor to underlying demand, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne."<ref name="Microsoft Word - prelims.doc">{{cite web|url=http://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/56302/housing.pdf |title=Microsoft Word - prelims.doc |access-date=14 July 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110603013605/http://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/56302/housing.pdf |archive-date=3 June 2011 |df=dmy }}</ref> The ] in its submission to the same Productivity Commission report stated that "rapid growth in overseas visitors such as students may have boosted demand for rental housing".<ref name="Microsoft Word - prelims.doc" /> However, the Commission found that "the ABS resident population estimates have limitations when used for assessing housing demand. Given the significant influx of foreigners coming to work or study in Australia in recent years, it seems highly likely that short-stay visitor movements may have added to the demand for housing. However, the Commissions are unaware of any research that quantifies the effects."<ref name="Microsoft Word - prelims.doc" /> | |||

| There is a significant difference in education and training between Migration Agents and Lawyers. Migration Agents, unlike Lawyers, are not practically trained or supervised, and have not completed full-time legal education, only an 18 week course of six hours per week. Before July 2006, Migration Agents were only required to pass a short multiple choice examination. To identify how many years a Migration Agent has been registered from, the first two numbers of their seven digit registration number will show the year. Only Migration Agents registered pre March 28, 1998 can have a five digit number. | |||

| Some individuals and interest groups have also argued that immigration causes overburdened infrastructure.<ref name="er3">Claus, E (2005) (submission 12 to the Productivity Commission's position paper on Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth). {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927003342/http://www.pc.gov.au/study/migrationandpopulation/subs/sub012.rtf|date=27 September 2007}}</ref><ref name="er4">Nilsson (2005) (submission 9 to the Productivity Commission's position paper on Economic Impacts of Migration and Population Growth). {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927003114/http://www.pc.gov.au/study/migrationandpopulation/subs/sub009.rtf|date=27 September 2007}}</ref> | |||

| == Migration and settlement services == | |||

| There are a variety of community-based services that cater to the needs of newly-arrived migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, some of which receive funding from the Commonwealth Government, such as ]s. Asylum seekers, however, are denied access to such services and there are only a very small number of specific ] catering to their needs. | |||

| ===Employment=== | |||

| Australia maintains a ] of skilled occupations that are currently acceptable for immigration to Australia.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/visas/working-in-australia/skill-occupation-list|title=Skilled Occupations List|website=]. Department of Home Affairs|access-date=4 Jan 2021|date=10 December 2020|archive-date=4 January 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210104002713/https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/visas/working-in-australia/skill-occupation-list|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| In 2009, following the ], the Australian government reduced its immigration target by 14%, and the permanent migration program for skilled migrants was reduced to 115,000 people for that financial year.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2009/03/16/2517422.htm?section=justin|title=Immigration cut only temporary 16Mar 2009|date=16 March 2009|publisher=Abc.net.au|access-date=14 July 2011|archive-date=5 August 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090805152525/http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2009/03/16/2517422.htm?section=justin|url-status=live}}</ref> In 2010–2011, the migration intake was adjusted so that 67.5% of the permanent migration program would be for skilled migrants, and 113,725 visas were granted.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/statistics/net-overseas-migration-march-2013.pdf|title=Net overseas migration|date=31 March 2013|website=Department of Immigration and Border Protection (Australia)|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151126045250/http://www.border.gov.au/ReportsandPublications/Documents/statistics/net-overseas-migration-march-2013.pdf|archive-date=26 November 2015|access-date=28 December 2019}}</ref> | |||

| According to ''Graduate Careers Australia'', there have been ] for recent university graduates of various degrees, including dentistry, computer science, architecture, psychology, and nursing.<ref name="graduatecareers.com.au">{{Cite web |url=http://www.graduatecareers.com.au/research/surveys/australiangraduatesurvey/ |title=Australian Graduate Survey - Graduate Careers Australia |access-date=18 December 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170827054424/http://www.graduatecareers.com.au/Research/Surveys/australiangraduatesurvey/ |archive-date=27 August 2017 |url-status=dead }}</ref> In 2014, a number of the professional associations for some of these fields criticised the immigration policy for skilled migrants, contending that these policies have contributed to difficulties for local degree holders in obtaining full-time employment.<ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.theaustralian.com.au/higher-education/dentists-join-the-growing-calls-for-cap-on-student-uni-places/story-e6frgcjx-1226871304881| url-status = dead| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140402193918/http://www.theaustralian.com.au/higher-education/dentists-join-the-growing-calls-for-cap-on-student-uni-places/story-e6frgcjx-1226871304881| archive-date = 2014-04-02| title = Dentists join the growing calls for cap on student uni places {{!}} The Australian}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{cite web| url = http://www.optometrists.asn.au/blog-news/2014/6/23/workforce-report-forecasts-1,200-excess-by-2036.aspx| url-status = dead| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140720052514/http://www.optometrists.asn.au/blog-news/2014/6/23/workforce-report-forecasts-1,200-excess-by-2036.aspx| archive-date = 2014-07-20| title = Optometry Australia}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-05-24/thousands-of-nursing-graduates-unable-to-find-work/5475320|title=Nurses union says 3,000 graduates cannot find work|first=John|last=Stewart|date=24 May 2014|website=ABC News|access-date=28 December 2019|archive-date=19 May 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190519015332/https://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-05-24/thousands-of-nursing-graduates-unable-to-find-work/5475320|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title=Surfeit of vets prompts call to cap places| website=]|url=http://www.theaustralian.com.au/higher-education/surfeit-of-vets-prompts-call-to-cap-places/story-e6frgcjx-1226807060998|date=January 22, 2014|first=Julie|last=Hare|archive-date=January 25, 2017 | archive-url=https://archive.today/20170125123528/http://www.theaustralian.com.au/higher-education/surfeit-of-vets-prompts-call-to-cap-places/story-e6frgcjx-1226807060998|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.architectureanddesign.com.au/news/does-australia-have-too-many-designers|title=Construction & Architecture News|website=Architecture & Design|access-date=28 December 2019|archive-date=28 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191228013236/https://www.architectureanddesign.com.au/news/does-australia-have-too-many-designers|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title=Accounting 'not cut' from immigration skilled occupations list for 2015| website=]|url=http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/immigration/accounting-not-cut-from-immigration-skilled-occupations-list-for-2015/story-fn9hm1gu-1227120626345|date=November 12, 2014|first=Nicola|last=Berkovic|archive-date=January 18, 2015 | archive-url=https://archive.today/20150118130524/http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/immigration/accounting-not-cut-from-immigration-skilled-occupations-list-for-2015/story-fn9hm1gu-1227120626345?nk=52819a49a912daae89871175d7f130ee|url-status=dead}}</ref> In 2016, the Department of Health forecast a shortfall in nurses of approximately 85,000 by 2025 and 123,000 by 2030.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.smh.com.au/business/workplace-relations/forecast-oversupply-of-doctors-to-hit-this-year-amid-calls-to-halt-imports-20170103-gtle76.html|title=Forecast oversupply of doctors to hit this year amid calls to halt imports|last=Patty|first=Anna|date=2017-01-08|newspaper=The Sydney Morning Herald|language=en-US|access-date=2017-01-08|archive-date=27 August 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170827043928/http://www.smh.com.au/business/workplace-relations/forecast-oversupply-of-doctors-to-hit-this-year-amid-calls-to-halt-imports-20170103-gtle76.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| In 2016, ] academics published a report which contended that Australia's immigration program is deeply flawed. The government's ''Medium to Long-Term Strategic Skill List'' allows immigration by professionals who end up competing with graduates of Australian universities for scarce positions. On the other hand, Australia's shortage of ] is not being addressed.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | url =http://tapri.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Final-March-8-Australias-skilled-migration-program.pdf | |||

| | title =Australia's Skilled Migration Program: Scarce Skills Not Required | |||

| | last =Birrell | |||

| | first =Bob | |||

| | date =8 March 2016 | |||

| | website =The Australian Population Research Institute | |||

| | publisher =Monash University | |||

| | access-date =14 March 2018 | |||

| | archive-date =15 March 2018 | |||

| | archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20180315003733/http://tapri.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Final-March-8-Australias-skilled-migration-program.pdf | |||

| | url-status =live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ===Economic growth and aging population=== | |||

| Another element in the immigration debate is a concern to alleviate adverse impacts arising from Australia's ageing population. In the 1990s, the former ] ] stated that Australia is underpopulated due to a low birth rate, and that negative population growth will have adverse long-term effects on the economy as the population ages and the labour market becomes less competitive.<ref>{{cite news | url=https://www.smh.com.au/news/national/costello-hatches-censustime-challenge-procreate-and-cherish/2006/07/24/1153593272565.html | title=Costello hatches census-time challenge: procreate and cherish | date=25 July 2006 | work=The Sydney Morning Herald | access-date=20 February 2020 | archive-date=2 January 2017 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170102150849/http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/costello-hatches-censustime-challenge-procreate-and-cherish/2006/07/24/1153593272565.html | url-status=live }}</ref> To avoid this outcome the government increased immigration to fill gaps in labour markets and introduced a ] to encourage families to have more children.{{Citation needed|date=January 2017}} However, opponents of population growth such as Sustainable Population Australia do not accept that population growth will decline and reverse, based on current immigration and fertility projections.<ref name="Goldie">Goldie, J. (23 February 2006) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210225141712/http://www.onlineopinion.com.au/view.asp?article=4163 |date=25 February 2021 }} (Retrieved 30 October 2006)</ref> | |||

| There is debate over whether immigration can slow the ageing of Australia's population. In a research paper entitled ''Population Futures for Australia: the Policy Alternatives'', Peter McDonald claims that "it is demographic nonsense to believe that immigration can help to keep our population young."<ref name="PFFAPA">McDonald, P., Kippen, R. (1999) {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110818001206/http://www.aph.gov.au/library/pubs/rp/1999-2000/2000rp05.htm |date=18 August 2011 }}</ref> However, according to Creedy and Alvarado (p. 99),<ref>{{cite book|title=Population Ageing, Migration and Social Expenditure |date=9 September 2009 |isbn=978-1858987248 |last1=Alvarado |first1=José |last2=Creedy |first2=John |publisher=Edward Elgar }}</ref> by 2031 there will be a 1.1 per cent fall in the proportion of the population aged over 65 if net migration rate is 80,000 per year. If net migration rate is 170,000 per year, the proportion of the population aged over 65 would reduce by 3.1 per cent. As of 2007 during the leadership of ], the net migration rate was 160,000 per year.<ref>{{cite news | url=http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2007/11/24/1195753378227.html?page=fullpage#contentSwap2 | location=Melbourne | work=The Age | title=Farewell, John. We will never forget you | date=25 November 2007 | access-date=27 November 2007 | archive-date=3 March 2016 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303203019/http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2007/11/24/1195753378227.html?page=fullpage#contentSwap2 | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||