| Revision as of 01:43, 25 January 2008 editSmackBot (talk | contribs)3,734,324 editsm Date the maintenance tags or general fixes using AWB← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:43, 20 December 2024 edit undo2001:fb1:10:35c4:a134:1545:c90d:442f (talk) →Russian | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Language used to facilitate communication between groups without a common native language}} | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{wiktionary|lingua franca}} | |||

| {{Distinguish|text=]}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2018}} | |||

| A '''lingua franca''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|l|ɪ|ŋ|ɡ|w|ə|_|ˈ|f|r|æ|ŋ|k|ə}}; {{literal translation|Frankish tongue}}; for plurals see {{section link|#Usage notes}}), also known as a '''bridge language''', '''common language''', '''trade language''', '''auxiliary language''', '''link language''' or '''language of wider communication''' ('''LWC'''), is a ] systematically used to make communication possible between groups of people who do not share a ] or dialect, particularly when it is a third language that is distinct from both of the speakers' native languages.<ref>Viacheslav A. Chirikba, "The problem of the Caucasian Sprachbund" in Pieter Muysken, ed., ''From Linguistic Areas to Areal Linguistics'', 2008, p. 31. {{ISBN|90-272-3100-1}}</ref> | |||

| A '''lingua franca''' (Italian literally meaning ], see ]) is any ] widely used beyond the population of its native speakers. The ] status of ''lingua franca'' is usually "awarded" by the masses to the language of the most influential nation(s) of the time. Any given language normally becomes a ''lingua franca'' primarily by being used for international commerce, but can be accepted in other cultural exchanges, especially ]. | |||

| Linguae francae have developed around the world throughout human history, sometimes for commercial reasons (so-called "trade languages" facilitated trade), but also for cultural, religious, diplomatic and administrative convenience, and as a means of exchanging information between scientists and other scholars of different nationalities.<ref name="Nye">{{cite journal|last1=Nye|first1=Mary Jo|title=Speaking in Tongues: Science's centuries-long hunt for a common language|journal=Distillations|year=2016|volume=2|issue=1|pages=40–43|url=https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/magazine/speaking-in-tongues|access-date=20 March 2018|archive-date=3 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200803130801/https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/magazine/speaking-in-tongues|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Gordin">{{cite book|last1=Gordin|first1=Michael D.|title=Scientific Babel: How Science Was Done Before and After Global English|date=2015|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago, Illinois|isbn=9780226000299}}</ref> The term is taken from the medieval ], a ]-based ] used especially by traders in the ] from the 11th to the 19th centuries.<ref>{{Cite book|date=1975|title=Italian-Based Pidgins and Lingua Franca|series=Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications|volume=14|pages=70–72}}</ref> A ]—a language spoken internationally and by many people—is a language that may function as a global lingua franca.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Woll |first1=Bensie |title=English of often considered the de facto global language... |url=https://www.ucl.ac.uk/culture-online/case-studies/2022/mar/english-often-considered-de-facto-global-language |website=University College London Culture Online |publisher=University College London |access-date=17 October 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ''Lingua franca'' sometimes refers to the ''de facto'' language within a more or less specialized field, such as international radio communications (], ]). | |||

| ==Characteristics== | |||

| A synonym for ''lingua franca'' is “'''vehicular language'''.” Whereas a '']'' language is used as a native language in a single speaker community, a ''vehicular'' language goes beyond the boundaries of its original community, and is used as a second language for communication between communities. For example, English is a vernacular in England, but is used as a vehicular language (that is, a ''lingua franca'') in Pakistan. | |||

| ] | |||

| Any language regularly used for communication between people who do not share a native language is a lingua franca.<ref>"vehicular, adj." ''OED Online''. Oxford University Press, July 2018. Web. 1 November 2018.</ref> Lingua franca is a functional term, independent of any linguistic history or language structure.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180522043320/http://privatewww.essex.ac.uk/~patrickp/Courses/PCs/IntroPidginsCreoles.htm |date=22 May 2018 }} – ''Pidgin and Creole Languages: Origins and Relationships'' – Notes for LG102, – University of Essex, Peter L. Patrick – Week 11, Autumn term.</ref> | |||

| The term '''lingua franca''' is also applied to ] meant specifically for communication between speakers of different native languages. Examples include ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| ]s are therefore lingua francas; ] and arguably ]s may similarly be used for communication between language groups. But lingua franca is equally applicable to a non-creole language native to one nation (often a colonial power) learned as a ] and used for communication between diverse language communities in a colony or former colony.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|url=http://www.termcoord.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Lingua_franca.pdf|title=Lingua Franca: Chomera or Reality?|year=2010|publisher=Publ. Office of the Europ. Union |isbn=9789279189876|access-date=15 December 2018|archive-date=27 February 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200227090056/https://termcoord.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Lingua_franca.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==European languages== | |||

| ===Greek and Latin=== | |||

| During the time of the ] and ], the ''linguae francae'' were ] and ]. During the ], the ''lingua franca'' was Greek in the parts of Europe and Middle East where the ] held hegemony, and Latin was primarily used in the rest of Europe. Latin, for a significant portion of the expansion of the ], was used as the basis of the Church. This was later changed to local languages, although it is still the official language of the ]. | |||

| Lingua francas are often pre-existing languages with native speakers, but they can also be pidgins or creoles developed for that specific region or context. Pidgins are rapidly developed and simplified combinations of two or more established languages, while creoles are generally viewed as pidgins that have evolved into fully complex languages in the course of adaptation by subsequent generations.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Pidgin and Creole Languages|last=Romaine|first=Suzanne|publisher=Longman|year=1988}}</ref> Pre-existing lingua francas such as French are used to facilitate intercommunication in large-scale trade or political matters, while pidgins and creoles often arise out of colonial situations and a specific need for communication between colonists and indigenous peoples.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://thariqalfathih.wordpress.com/2015/04/03/lingua-franca-pidgin-and-creole/|title=Lingua Franca, Pidgin, and Creole|date=3 April 2015|access-date=29 April 2019|archive-date=21 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200821190239/https://thariqalfathih.wordpress.com/2015/04/03/lingua-franca-pidgin-and-creole/|url-status=live}}</ref> Pre-existing lingua francas are generally widespread, highly developed languages with many native speakers.{{Citation needed|date=May 2021}} Conversely, pidgins are very simplified means of communication, containing loose structuring, few grammatical rules, and possessing few or no native speakers. ] languages are more developed than their ancestral pidgins, utilizing more complex structure, grammar, and vocabulary, as well as having substantial communities of native speakers.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Language – Pidgins and creoles|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/language|access-date=2021-05-11|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en|archive-date=5 December 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141205091036/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/329791/language/27194/Linguistic-change|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Sabir and Italian===<!-- This section is linked from ] --> | |||

| {{main|Lingua franca of the Mediterranean}} | |||

| Originally ''"Lingua Franca"'' (also known as ''Sabir'') referred to a mix of mostly ] with a broad vocabulary drawn from ], ], ] and ]. ''Lingua Franca'' literally means "] language". This originated from the Arabic custom of referring to all Europeans as Franks. This mixed language (], ]) was used for communication throughout the medieval and early modern ] as a '''diplomatic language'''; the generic description ''"lingua franca"'' has since become common for any language used by speakers of different languages to communicate with one another. Some samples of ''Sabir'' have been preserved in ]'s ], '']''. | |||

| Whereas a ] language is the native language of a specific geographical community,<ref>{{Cite web|title=Definition of VERNACULAR|url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/vernacular|access-date=2021-05-11|website=www.merriam-webster.com|language=en|archive-date=15 May 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210515083616/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/vernacular|url-status=live}}</ref> a lingua franca is used beyond the boundaries of its original community, for trade, religious, political, or academic reasons.<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|last=Dursteler|first=Eric R.|title=Speaking in Tongues: Language and Communication in the Early Modern Mediterranean|date=2012|journal=Past & Present|issue=217|pages=47–77|doi=10.1093/pastj/gts023}}</ref> For example, ] is a {{Emphasis|vernacular}} in the ] but it is used as a {{Emphasis|lingua franca}} in the ], alongside ]. Likewise, ], ], ], ] and ] serve similar purposes as industrial and educational lingua francas across regional and national boundaries. | |||

| Italian dialects were spoken in medieval times as ''lingua franca'' in the European commercial empires of Italian cities (], ], ], ], ], ], ]) and in their colonies located in the Middle East and in the Mediterranean sea. During the ], ] was also spoken as language of culture in the main royal courts of Europe and among intellectuals. The Italian language is still used as a lingua franca in some environments. For example, in the Catholic ecclesiastic hierarchy, Italian is known by a large part of members and is used in substitution of Latin in some official documents as well. The presence of Italian as the second official language in Vatican City indicates its use not only in the seat in ], but also anywhere in the world where an episcopal seat is present. | |||

| Even though they are used as bridge languages, ]s such as ] have not had a great degree of adoption, so they are not described as lingua francas.<ref>{{cite web|last=Directorate-General for Translation|first=European Commission|year=2011|title=Studies on translation and multilingualism|url=http://cordis.europa.eu/fp7/ict/language-technologies/docs/lingua-franca-en.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121115090926/http://cordis.europa.eu/fp7/ict/language-technologies/docs/lingua-franca-en.pdf|archive-date=2012-11-15|publisher=Europa (web portal)|pages=8, 22–23|quote=Up to now have all proved transient and none has actually achieved the status of lingua franca with a large community of fluent speakers.}}</ref> | |||

| ===Spanish=== | |||

| ] replaced ] as the language of diplomacy and (in some aspects) culture during the 16th and 17th centuries, until it was replaced by French. Spanish was also used throughout the former ], particularly in ] and ], and became the lingua franca of the ] in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Today, it is a lingua franca in most of the countries of ] (with the notable exceptions of ] and the ]). | |||

| == |

==Etymology== | ||

| The term ''lingua franca'' derives from ] (also known as ''Sabir''), the pidgin language that people around the ] and the eastern Mediterranean Sea used as the main language of commerce and diplomacy from the late ] to the 18th century, most notably during the ].<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/lingua-franca|title=lingua franca {{!}} linguistics|encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica|access-date=8 August 2017|archive-date=31 July 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200731180042/https://www.britannica.com/topic/lingua-franca|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=":0" /> During that period, a simplified version of mainly ] in the eastern Mediterranean and ] in the western Mediterranean that incorporated many ]s from ], ], ], and ] came to be widely used as the "lingua franca" of the region, although some scholars claim that the Mediterranean Lingua Franca was just poorly used Italian.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

| ] was the language of ] in ] from the ] until its recent replacement by English, and as a result is still a working language of international institutions and is seen on documents ranging from passports to airmail letters. For many years, until the accession of the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Denmark in ], French and German were the only official working languages of the ]. French was also the lingua franca of European ] in the ]. | |||

| In Lingua Franca (the specific language), {{Lang|pml|lingua}} is from the Italian for 'a language'. {{Lang|pml|Franca}} is related to Greek {{Lang|grc|Φρᾰ́γκοι}} ({{Lang|grc|]}}) and Arabic {{Lang|ar|إِفْرَنْجِي}} ({{Lang|ar-Latn|ʾifranjiyy}}) as well as the equivalent Italian—in all three cases, the literal sense is ']', leading to the direct translation: 'language of the ]'. During the late ], ''Franks'' was a term that applied to all Western Europeans.<ref name="HEL">{{cite book |url=http://www.komvos.edu.gr/dictonlineplsql/simple_search.display_full_lemma?the_lemma_id=16800&target_dict=1 |title=''Lexico Triantaphyllide'' online dictionary, Greek Language Center (''Kentro Hellenikes Glossas''), lemma Franc ( Φράγκος ''Phrankos''), ''Lexico tes Neas Hellenikes Glossas'', G.Babiniotes, Kentro Lexikologias(Legicology Center) LTD Publications |publisher=Komvos.edu.gr |year=2002 |isbn=960-86190-1-7 |quote=Franc and (prefix) franco- (Φράγκος ''Phrankos'' and φράγκο- ''phranko-'') |access-date=18 June 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120324054919/http://www.komvos.edu.gr/dictonlineplsql/simple_search.display_full_lemma?the_lemma_id=16800&target_dict=1 |archive-date=24 March 2012 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://archive.org/details/etymologicaldict00weekuoft/ |title=An etymological dictionary of modern English : Weekley, Ernest, 1865–1954 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive |access-date=18 June 2015}}</ref><ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141012185830/http://www.scribd.com/doc/14047074/Dictionary-English-Etymology-Origins-A-Short-Etymological-Dictionary-of-Modern-English-Rouledge-1958-Parridge|date=12 October 2014}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=House|first=Juliane|date=2003|title=English as a lingua franca: A threat to multilingualism?|journal=Journal of Sociolinguistics|language=en|volume=7|issue=4|pages=557|doi=10.1111/j.1467-9841.2003.00242.x|issn=1467-9841|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| French was also the language used among the educated in many cosmopolitan cities across the ] and ]. This was true in cities such as Cairo, around the turn of the 20th century until ], and especially in the French colonies of the ]. French is particularly important in ] and its capital, ]. Until the outbreak of the ] in Lebanon, French was the language that the Christian members of the upper class of Lebanese society used. French is still a lingua franca in most ] and ]n countries (where it often enjoys official status), a remnant of the colonial rule of France and ]. These African countries, together with several other countries throughout the world, are members of '']''. | |||

| Through changes of the term in literature, ''lingua franca'' has come to be interpreted as a general term for pidgins, creoles, and some or all forms of vehicular languages. This transition in meaning has been attributed to the idea that pidgin languages only became widely known from the 16th century on due to European colonization of continents such as The Americas, Africa, and Asia. During this time, the need for a term to address these pidgin languages arose, hence the shift in the meaning of Lingua Franca from a single proper noun to a common noun encompassing a large class of pidgin languages.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Brosch|first=C.|date=2015|title=On the Conceptual History of the Term Lingua Franca|journal= Apples: Journal of Applied Language Studies|volume=9|issue=1|pages=71–85|doi=10.17011/apples/2015090104|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ===German=== | |||

| ] served as a ''lingua franca'' in large portions of Europe for centuries, mainly the ] (of the German Nation). From about 1200 to 1600, ] was the language of the ] which was present in most Northern European seaports, even London{{Fact|date=January 2008}}. Later, variants of German were (or are) also used in the Americas and small parts of Asia, (Turkey, Russia, Kazakhstan). During the 19th and 20th centuries, Germany was leading in the sciences — particularly in ], ] and ], winning ] — and the language was also used in international business and politics. Since 1933, the politics of Nazi Germany caused the emigration of many scientists like ], or artists like ], mainly to the US, thus American English took over in these fields after 1945. German was also spoken in much of Eastern Europe long after the end of ]. In some academic disciplines, most notably ] and ], a reading knowledge of German is still considered essential and required of doctoral candidates by some universities all over the world, not just those in ]. During the construction of the ] in Australia, German was the lingua franca for workers from central and east Europe. | |||

| As recently as the late 20th century, some restricted the use of the generic term to mean only mixed languages that are used as vehicular languages, its original meaning.<ref>Webster's New World Dictionary of the American Language, Simon and Schuster, 1980</ref> | |||

| ===Polish=== | |||

| ] was a kind of ''lingua franca'' in large areas of Central and Eastern Europe, especially regions that belonged to the ]; this influence extend beyond the borders of the Commonwealth because of the state's considerable political and military power in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. Polish was for several centuries the main language spoken by the ruling classes in ] and ], and the modern state of ], but was also understood further south-east, for example in the Tatar Khanate, the Romanian lands and the Slav parts of Hungary. After the partitioning of Poland in the 1790s, the ] almost completely substituted Polish by the 20th century. Even so, Polish is today still sometimes spoken or at least understood in the western border areas of ], ], ] and parts of northern Slovakia. | |||

| Douglas Harper's ''Online Etymology Dictionary'' states that the term ''Lingua Franca'' (as the name of the particular language) was first recorded in English during the 1670s,<ref name="Harper">{{cite web |url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=lingua+franca |title=Online Etymology Dictionary |publisher=Etymonline.com |access-date=18 June 2015 |archive-date=11 May 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150511041942/http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=lingua+franca |url-status=live }}</ref> although an even earlier example of the use of it in English is attested from 1632, where it is also referred to as "Bastard Spanish".<ref name="Morgan">{{cite book |last=Morgan |first=J. |year=1632 |title=A Compleat History of the Present Seat of War in Africa, Between the Spaniards and Algerines |page=98 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6M8TAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA98 |access-date=8 June 2013 |archive-date=17 October 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221017152407/https://books.google.com/books?id=6M8TAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA98 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Portuguese=== | |||

| ==Usage notes== | |||

| ] served as ''lingua franca'' in ], ] and ] in the ] and ]. When the Portuguese started exploring the seas of Africa, America, Asia and Oceania, they tried to communicate with the natives by mixing a Portuguese-influenced version of Lingua Franca with the local languages. When English or French ships came to compete with the Portuguese, the crew tried to learn this "broken Portuguese". Through a process of change the Lingua Franca and Portuguese lexicon was replaced with the languages of the people in contact. | |||

| The term is well established in its naturalization to English and so major dictionaries do not italicize it as a "foreign" term.<ref name="OxfordDictionaries">{{Citation |author=Oxford Dictionaries |author-link=OxfordDictionaries.com |title=Oxford Dictionaries Online |publisher=Oxford University Press |url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20010516042450/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/ |url-status=dead |archive-date=16 May 2001 |postscript=.}}</ref><ref name="AHD">{{Citation |author=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt |title=The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language |publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt |url=https://ahdictionary.com/ |postscript=. |access-date=25 February 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150925104737/https://ahdictionary.com/ |archive-date=25 September 2015 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref name="MW_Collegiate">{{Citation |author=Merriam-Webster |author-link=Merriam-Webster |title=MerriamWebster's Collegiate Dictionary |publisher=Merriam-Webster |url=http://unabridged.merriam-webster.com/collegiate/ |postscript=. |access-date=25 February 2018 |archive-date=10 October 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201010163505/https://unabridged.merriam-webster.com/subscriber/login?redirect_to=%2Fcollegiate%2F |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Its plurals in English are ''lingua francas'' and ''linguae francae'',<ref name="AHD" /><ref name="MW_Collegiate" /> with the former being first-listed<ref name="AHD" /><ref name="MW_Collegiate" /> or only-listed<ref name="OxfordDictionaries" /> in major dictionaries. | |||

| Portuguese remains an important ''lingua franca'' in Africa (]), ], ], and to a certain extent in ] because ] is the largest and most populous country in Latin America. | |||

| == |

==Examples== | ||

| {{Main|List of lingua francas}} | |||

| ] is in use and widely understood in areas of ] and ] ] and Northern and Central ] formerly part of the ], or of the former ]. Its use in Central and Eastern Europe has declined dramatically since the ], but it remains the lingua franca in the ]. Recent migrations from the former Soviet Union made Russian one of the most spoken languages in Israel. | |||

| ===Historical lingua francas=== | |||

| ===English=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] is the current ''lingua franca'' of international business, science, technology and aviation, and has displaced French as the lingua franca of diplomacy since ]{{Fact|date=December 2007}}. It was advanced by the role of English-speaking countries, such as the ], ], ], and the ] in the aftermath of ], particularly in the organization and procedure of the ]. | |||

| The use of lingua francas has existed since antiquity. | |||

| English was previously imposed as, and remains, the ''lingua franca'' of former ] nations (including ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]), present British territories (like ], ], and ]), former British territories (such as ]), U.S. territories (like ], ], ]), ] (both ] and ]), and ]. In many of these nations the use of English is seen as a means of avoiding the political difficulties inherent in promoting any individual indigenous language as the lingua franca. | |||

| ] remained the common language of a large part of Western Asia from several earlier empires, until it was supplanted in this role by ].<ref>Ostler, 2005 pp. 38–40</ref><ref>Ostler, 2010 pp. 163–167</ref> | |||

| The modern trend to use English outside of English-speaking countries has a number of sources. Ultimately, the use of English in a variety of locations across the globe is a consequence of the reach of the British Empire. But the establishment of English as an international lingua franca after World War II was mostly a result of the spread of English via cultural and technological exports from the United States as well as its embedding in international institutions; for instance, the seating and roll-call order in sessions of the ] and its organs is determined by English alphabetical order, and, while there are six ''official'' languages of the United Nations, only two (English and French) are ''working'' languages, and, in practice, English is the sole working language of most UN bodies. This is contributed to by the fact that UN headquarters, and the majority of UN bodies, are based in the United States. | |||

| ] historically served as a lingua franca throughout the majority of South Asia.<ref>The Last Lingua Franca: English Until the Return of Babel. Nicholas Ostler. Ch.7. {{ISBN|978-0802717719}}</ref><ref>A Dictionary of Buddhism p.350 {{ISBN|0191579173}}</ref><ref>Before the European Challenge: The Great Civilizations of Asia and the Middle East p.180 {{ISBN|0791401685}}</ref> The Sanskrit language's historic presence is attested across a wide geography beyond South Asia. Inscriptions and literary evidence suggest that Sanskrit was already being adopted in Southeast Asia and Central Asia in the 1st millennium CE, through monks, religious pilgrims and merchants.<ref>{{cite book|author=Sheldon Pollock|editor=Jan E. M. Houben|title=Ideology and Status of Sanskrit|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_eqr833q9qYC|year=1996|publisher=BRILL Academic|isbn=978-90-04-10613-0|pages=197–223 with footnotes|access-date=19 March 2022|archive-date=17 October 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221017152353/https://books.google.com/books?id=_eqr833q9qYC|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author1=William S.-Y. Wang|author-link1=William S-Y. Wang|author2=Chaofen Sun|title=The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Linguistics|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YqT4BQAAQBAJ|year=2015|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-985633-6|pages=6–19, 203–212, 236–245|access-date=19 March 2022|archive-date=17 October 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221017152357/https://books.google.com/books?id=YqT4BQAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Burrow |first=Thomas |author-link=Thomas Burrow |title=The Sanskrit Language |year=1973 |edition=3rd, revised |location=London |publisher=Faber & Faber |pages=63–66}}</ref> | |||

| English is also regarded by some as the global ''lingua franca'' owing to the economic hegemony of most of the developed Western nations in world financial and business institutions. The de facto status of English as the ''lingua franca'' in these countries has carried over globally as a result. English is also overwhelmingly dominant in scientific and technological communications, and all of the world's major ] are published in English. | |||

| Until the early 20th century, ] served as both the written lingua franca and the diplomatic language in East Asia, including China, ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{Cite web |date=2015-04-28 |title=Reclaiming a Common Language {{!}} BU Today |url=https://www.bu.edu/articles/2015/reclaiming-a-common-language/ |access-date=2023-07-23 |website=Boston University |language=en}}</ref> In the early 20th century, ] replaced Classical Chinese within China as both the written and spoken lingua franca for speakers of different Chinese dialects, and because of the declining power and cultural influence of China in East Asia, English has since replaced Classical Chinese as the lingua franca in East Asia. | |||

| A landmark recognition of the dominance of English in Europe came in 1995 when, on the accession of Austria, Finland and Sweden, English joined French and German as one of the working languages of the ]. Many Europeans outside of the EU have also adopted English as their current lingua franca. For example, English serves as a somewhat lingua franca in ], which has four ''official'' languages (German, French, Italian and ], spoken by a relatively small minority). German is also spoken by many Swiss citizens, but the relatively high foreign-born population (21% of residents) ensures a relatively wide use of English. | |||

| ] was the lingua franca of the Hellenistic culture. Koine Greek<ref name=collins>{{cite Collins Dictionary|Koine | |||

| English is also the dominant language of the Internet, due to the fact that the Internet was first developed in the United States, and the dominance of English in academics and science and technology (especially computer technology), which were some of the original uses of the Internet. | |||

| |access-date=2014-09-24}}</ref><ref>{{cite Dictionary.com|Koine}}</ref><ref name="mw">{{cite Merriam-Webster|Koine}}</ref> (Modern {{langx|el|Ελληνιστική Κοινή|Ellinistikí Kiní|Common Greek}}; {{IPA-el|elinistiˈci ciˈni|lang}}), also known as Alexandrian dialect, common Attic, Hellenistic, or Biblical Greek, was the ] of Greek spoken and written during the ], the ] and the early ]. It evolved from the spread of Greek following the conquests of ] in the fourth century BC, and served as the lingua franca of much of the Mediterranean region and the Middle East during the following centuries.<ref name="Bubenik">{{cite book|last=Bubenik|first=V.|year=2007|chapter=The rise of Koiné|editor=A. F. Christidis|title=A history of Ancient Greek: from the beginnings to late antiquity|location=Cambridge|publisher=University Press|pages=342–345}}</ref> | |||

| ] was once the lingua franca for most of ancient ] and ]. ] states that Tamil was also the lingua franca for early maritime traders from India.<ref name="scroll.in">{{citation|url=http://scroll.in/article/704603/Step-aside%2C-Gujaratis%3A-Tamilians-were-India%27s-earliest-recorded-maritime-traders|title=Scroll.in – News. Politics. Culture.|date=6 February 2015 |publisher=scroll.in|access-date=29 March 2022|archive-date=8 February 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150208095602/http://scroll.in/article/704603/Step-aside%2C-Gujaratis%3A-Tamilians-were-India%27s-earliest-recorded-maritime-traders|url-status=live}}</ref> The language and its dialects were used widely in the state of Kerala as the major language of administration, literature and common usage until the 12th century AD. Tamil was also used widely in inscriptions found in the southern ] districts of ] and ] until the 12th century AD.<ref>{{Citation |last=Talbot |first=Cynthia |title=Precolonial India in practice: Society, Region and Identity in Medieval Andhra |place=New York |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-19-513661-6 |pages=27–37}}</ref> Tamil was used for inscriptions from the 10th through 14th centuries in southern Karnataka districts such as ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{Citation |last1=Murthy |first1=Srinivasa |last2=Rao |first2=Surendra |last3=Veluthat |first3=Kesavan |last4=Bari |first4=S.A. |year=1990 |title=Essays on Indian History and culture: Felicitation volume in Honour of Professor B. Sheik Ali |publisher=Mittal |place=New Delhi |isbn=978-81-7099-211-0 |pages=85–106}}</ref> | |||

| On the other hand English as a former lingua franca of the Indian subcontinent was replaced by Hindi-Urdu and has suffered a strong decline in recent decades. | |||

| ], through the power of the ], became the dominant language in ] and subsequently throughout the realms of the Roman Empire. Even after the ], Latin was the common language of communication, science, and academia in Europe until well into the 18th century, when other regional vernaculars (including its own descendants, the Romance languages) supplanted it in common academic and political usage, and it eventually became a ] in the modern linguistic definition. | |||

| ==Asian languages== | |||

| ===Arabic=== | |||

| ], the native language of the ], who originally came from the ], became the "lingua franca" of the ] (]) (from AD 700 - AD 1492), which at a certain point spread from the borders of ] and ] through ], ], ], ], ] all the way to ] and ] in the west. | |||

| ] is the retrospective name for the language (formed out of many dialects, albeit all mutually intelligible)<ref name="History of the Māori language">{{Cite web |title=History of the Māori language |url=https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/maori-language-week/history-of-the-maori-language |access-date=2023-09-12 |website=nzhistory.govt.nz |language=en}}</ref> of both the North Island and the South Island for the 800 years before the ].<ref>''Ko Aotearoa Tēnei, Te Taumata Tuarua - Wai 262'' (2011), Waitangi Tribunal, pp. 41</ref><ref>Preservation of Classical Maori', from An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A.H. McLintock. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand URL: <nowiki>http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/1966/maori-language/page-10</nowiki> (accessed 16 Mar 2024)</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Belich |first=Jamie |title=Making Peoples: A History of New Zealanders |date=1996 |publisher=] |isbn=9781742288222 |edition=1st |location=Auckland |publication-date=1996 |pages=57,67 |language=English}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=New Zealand literature - Modern Maori, Poetry, Novels {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/art/New-Zealand-literature/Modern-Maori-literature |access-date=2024-03-15 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref><ref>''High or Classical Māori:'' Salient. Victoria University Student Newspaper. Volume 36, Number 21. 5 September 1973</ref> ] shared a common language that was used for trade, inter-] dialogue on ], and education through ].<ref>https://teara.govt.nz/en/economic-history/page-2 {{Bare URL inline|date=August 2024}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Brar |first=Atarjit |title=LibGuides: The Polynesian expansion across the Pacific: Maori |url=https://libguides.stalbanssc.vic.edu.au/polynesian-expansion/maori |access-date=2023-09-12 |website=libguides.stalbanssc.vic.edu.au |language=en}}</ref> After the signing of the ], Māori language was the lingua franca of the ] until English superseded it in the 1870s.<ref name="History of the Māori language"/><ref>{{Cite web |title=The Post |url=https://www.thepost.co.nz/nz-news/350124740/ok-monolingual-boomer-you-might-be-having-your-final-moment-sun#:~:text=At%20the%20advent%20of%20colonisation,language%20of%20trade%20and%20education. |access-date=2024-03-15 |website=www.thepost.co.nz}}</ref> The description of Māori language as New Zealand's 19th-century lingua franca has been widely accepted.<ref>Benton, Richard A. "Changes in Language Use in a Rural Maori Community 1963-1978." ''The Journal of the Polynesian Society'', vol. 89, no. 4, 1980, pp. 455–78. ''JSTOR'', <nowiki>http://www.jstor.org/stable/20705517</nowiki>. Accessed 15 Mar. 2024.</ref><ref name=":7">{{Cite web |title=The Post |url=https://www.thepost.co.nz/nz-news/350124740/ok-monolingual-boomer-you-might-be-having-your-final-moment-sun#:~:text=At%20the%20advent%20of%20colonisation,language%20of%20trade%20and%20education. |access-date=2024-03-15 |website=www.thepost.co.nz}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Coffey |first=Clare |title=Demand For Māori Language Skills at Work Rises in New Zealand |url=https://lightcast.io/resources/blog/demand-for-maori-language-skills-at-work-rises-in-new-zealand |access-date=2024-03-15 |website=Lightcast |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Revitalizing Endangered Languages |url=https://www.iar-gwu.org/blog/vsba8c5mqrhvufzl4gjfmqz39e20x0 |access-date=2024-03-15 |website=THE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS REVIEW |language=en-US}}</ref> The language was initially vital for all European and ] in New Zealand to learn,<ref name="Revitalizing Endangered Languages">{{Cite web |title=Revitalizing Endangered Languages |url=https://www.iar-gwu.org/blog/vsba8c5mqrhvufzl4gjfmqz39e20x0 |access-date=2023-09-12 |website=THE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS REVIEW |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Coffey |first=Clare |title=Demand For Māori Language Skills at Work Rises in New Zealand |url=https://lightcast.io/resources/blog/demand-for-maori-language-skills-at-work-rises-in-new-zealand |access-date=2024-03-15 |website=Lightcast |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=The Post |url=https://www.thepost.co.nz/nz-news/350124740/ok-monolingual-boomer-you-might-be-having-your-final-moment-sun#:~:text=At%20the%20advent%20of%20colonisation,language%20of%20trade%20and%20education. |access-date=2024-03-15 |website=www.thepost.co.nz}}</ref> as Māori formed a majority of the population, owned nearly all the country's land and dominated the economy until the 1860s.<ref name="Revitalizing Endangered Languages"/><ref>{{Cite web |last=Keane |first=Basil |date=11 March 2020 |title=Te Māori i te ohanga – Māori in the economy - Māori enterprise, 1840 to 1860 |url=https://teara.govt.nz/en/te-maori-i-te-ohanga-maori-in-the-economy/page-3 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240315040836/https://teara.govt.nz/en/te-maori-i-te-ohanga-maori-in-the-economy/page-3 |archive-date=15 March 2024 |access-date=19 November 2024 |website=Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand}}</ref> Discriminatory laws such as the ] contributed to the demise of Māori language as a lingua franca.<ref name="History of the Māori language"/> | |||

| Arabic was also used by people neighboring the Islamic Empire. During the ], Arabic was the language of science and diplomacy (around 1200 AD), when more books were written in Arabic than in any other language in the world at that time period. It influenced African sub-Saharan languages, east African languages, such as ] and loaned many words to ], ], ] and to significant extent on European languages such as ] and ], countries it ruled for 700 years (see Al-]). It is also said to have some ]. | |||

| ] was used to facilitate trade between those who spoke different languages along the ], which is why native speakers of Sogdian were employed as translators in ].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Lung|first=Rachel|title=Interpreters in Early Imperial China|publisher=John Benjamins Publishing Company|year=2011|isbn=9789027284181|pages=151–154}}</ref> The Sogdians also ended up circulating spiritual beliefs and texts, including those of ] and ], thanks to their ability to communicate to many people in the region through their native language.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Who Were the Sogdians, {{!}} The Sogdians|url=https://sogdians.si.edu/introduction/|access-date=2021-05-10|website=sogdians.si.edu|archive-date=11 September 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210911220242/https://sogdians.si.edu/introduction/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] was adopted by many other languages such as ], ], ] (changed to Latin in the late 19th century) and ] which switched to Latin script in 1928. Arabic became the lingua franca of these regions mainly because it is the language of the ], Islam's holy book. Arabic remains as the lingua franca for 22 countries in the ] and ], in addition to ]. Despite a few language script conversions from Arabic to Latin as just described, Arabic still is the second most widely used alphabetic system in the world after Latin.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9008156/Arabic-alphabet |title=Arabic Alphabet |accessdate=2007-11-23 |publisher=Enclopaedia Britannica online}}</ref> | |||

| ], an ] language, is the first Slavic ]. Between 9th and 11th century, it was the lingua franca of a great part of the predominantly ] states and populations in ] and ], in ] and church organization, culture, literature, education and diplomacy, as an ] and ] in the case of ]. It was the first national and also international Slavic literary language (autonym {{lang|cu|словѣ́ньскъ ѩꙁꙑ́къ}}, {{lang|cu-Latn|slověnĭskŭ językŭ}}).<ref name="lpd">{{citation|last= Wells|first= John C.|year= 2008|title= Longman Pronunciation Dictionary|edition= 3rd|publisher= Longman|isbn= 9781405881180}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |last= Jones |first= Daniel |author-link= Daniel Jones (phonetician) |title= English Pronouncing Dictionary |editor= Peter Roach |editor2= James Hartmann |editor3= Jane Setter |place= Cambridge |publisher= Cambridge University Press |orig-year= 1917 |year= 2003 |isbn= 978-3-12-539683-8 }}</ref> The Glagolitic alphabet was originally used at both schools, though the ] was developed early on at the ], where it superseded Glagolitic as the official script in ] in 893. Old Church Slavonic spread to other South-Eastern, Central, and Eastern European Slavic territories, most notably ], ], ], ], and principalities of the ] while retaining characteristically ] linguistic features. It spread also to not completely Slavic territories between the ], the ] and the ], corresponding to ] and ]. Nowadays, the Cyrillic ] is used for various languages across Eurasia, and as the national script in various Slavic, ], ], ], ] and ]-speaking countries in ], Eastern Europe, the ], Central, North, and East Asia. | |||

| According to ], and excluding Mandarin for which no information is given, Arabic is perceived to be the largest language among first-time speakers.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://encarta.msn.com/media_701500404/Languages_Spoken_by_More_Than_10_Million_People.html |title=Languages Spoken by More Than 10 Million People |accessdate=2007-02-18 |publisher=Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2006}}</ref> | |||

| The ] was largely based on Italian and ]. This language was spoken from the 11th to 19th centuries around the Mediterranean basin, particularly in the European commercial empires of Italian cities (], Venice, ], Milan, ], ]) and in trading ports located throughout the eastern Mediterranean rim.<ref>Henry Romanos Kahane. ''The Lingua Franca in the Levant'' (Turkish Nautical Terms of Italian and Greek Origin)</ref> | |||

| ===Aramaic=== | |||

| ], the native language of the ], became the ''lingua franca'' of the ] and the western provinces of the ], mainly because of its simple, ] ] (of which the modern ] is little more than a stylized form), more useful in administration than ]. | |||

| During the ], standard Italian was spoken as a language of culture in the main royal courts of Europe, and among intellectuals. This lasted from the 14th century to the end of the 16th, when French replaced Italian as the usual lingua franca in northern Europe.{{citation needed|date=July 2012}} Italian musical terms, in particular dynamic and tempo notations, have continued in use to the present day.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=15040264|title=Italian: The Language That Sings|website=NPR.org|access-date=21 February 2019|archive-date=17 October 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221017152355/https://www.npr.org/2007/10/08/15040264/italian-the-language-that-sings|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.ivirtuosidelloperadiroma.com/en/why-italian-is-the-language-of-music-and-opera/ |title=Why Italian is the language of music and opera |website=I Virtuosi dell'Opera Di Roma |date=4 January 2022 |access-date=10 January 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ===Azeri=== | |||

| According to the Russian historian ], ] served as a ''lingua franca'' throughout most parts of ] (except the ] coast), in ], ], and Southern ].<ref> by N. Trubetskoi. ''IRS'' Magazine, #7. Retrieved ], ] (in Russian)</ref> | |||

| ] is either of two historical forms of ], the exact relationship and degree of closeness between which is controversial, and which have sometimes been identified with each other.<ref>See Itier (2000: 47) for the distinction between the first and second enumerated senses, and the quote below for their partial identification.</ref> These are: | |||

| ===]=== | |||

| {{see|Bengali language}} | |||

| Bengali or Bangla, is commonly spoken in Bangladesh and India (especially in the states of West Bengal and Tripura). It is the official language and lingua franca of ]. Bengali is also an official language in of the ] state in India. | |||

| It has been derived from Sanskrit. | |||

| # the variety of Quechua that was used as a lingua franca and administrative language in the ] (1438–1533)<ref name=snow,stark1971>Snow, Charles T., Louisa Rowell Stark. 1971. Ancash Quechua: A Pedagogical Grammar. P.V 'The Quechua language is generally associated with the "classical" Quechua of the Cuzco area, which was used as a lingua franca through Peru and Bolivia with the spread of the Inca Empire'</ref> (or Inca lingua franca<ref>Following the terminology of Durston 2007: 40</ref>). Since the Incas didn't have writing, the evidence about the characteristics of this variety is scant and they have been a subject of significant disagreements.<ref>Durston 2007: 40, 322</ref> | |||

| ===]=== | |||

| # the variety of Quechua that was used in writing for religious and administrative purposes in the Andean territories of the Spanish Empire, mostly in the late 16th century and the first half of the 17th century and has sometimes been referred to, both historically and in academia, as ''lengua general'' ('common language')<ref>Beyersdorff, Margot, Sabine Dedenbach-Salazar Sáenz. 1994. Andean Oral Traditions: Discourse and Literature. P.275. 'the primarily ] domain of this lingua franca – sometimes referred to as "classical" Quechua'...</ref><ref>Bills, Garland D., Bernardo Valejo. 1969. P. XV. 'Immediately following the Spanish Conquest the Quechua language, especially the prestigious "classical" Quechua of the Cuzco area, was used as a lingua franca throughout the Andean region by both missionaries and administrators.'</ref><ref>Cf. also Durston (2007: 17): 'The 1550–1650 period can be considered both formative and classical in relation to the late colonial and republican production'.</ref><ref>See e.g. Taylor 1975: 7–8 for the dating and the name ''lengua general'' and Adelaar 2007: 183 for the dating</ref> (or Standard Colonial Quechua<ref>Following the terminology of Durston (2007: 40)</ref>). | |||

| In the ], Cebuano is spoken natively by the inhabitants of ], ], ] and some parts of ] and the ] islands and throughout ]. It is also spoken in a few towns and islands in Samar. Until 1975, Cebuano surpassed ] in terms of number of native speakers. Some dialects of Cebuano give different names to the language. Residents of Bohol may refer to Cebuano as "Bol-anon" while Cebuano-speakers in Leyte may call their dialect "Kana". It is also spoken by ]s in Samar and Leyte, ] in Poro, ]s in Negros Oriental, ] in Bohol, and by native (like ]s, ]s, and ]s) and migrant ] ethnic groups (like ]s and Ilonggos), and foreign ethnic groups (like Spaniards, Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans) ,and other people in Mindanao as second language. | |||

| ] functioned as lingua franca in the Caucasus region and in southeastern ], and was widely spoken at the court and in the army of ].<ref>{{cite book|pages=248–261|chapter=14|title=The Turkic Languages|author1=Lars Johanson|author2=Éva Á. Castó|year=1998|publisher=Routledge}}</ref> | |||

| ===Chinese=== | |||

| ] previously served as both a written ''lingua franca'' and diplomatic language in ], used by ], ], ], ], the ], and ] in interstate communications. In the early 20th century Classical Chinese in China was replaced by ]. Currently, among most Chinese-speaking communities, ] serves the function of providing a common spoken language between speakers of different and ] ] - not to mention between the ] and other ethnic groups in ]. ] has also been used as a way of communication through these character-using countries. Chinese is also a ''lingua franca'' of ], ], the ethnic Chinese population in ] and to a lesser extent the ethnic Chinese population in ]. | |||

| === |

===Modern=== | ||

| ====English==== | |||

| {{see|Filipino language}} | |||

| {{Main|English as a lingua franca}} | |||

| ], a standardized variety of ], serves as a ''lingua franca'' throughout the ] archipelago together with some ] words and ]. In the southern regions though, the ] and ] is more used as a ''lingua franca'' than Filipino. | |||

| [[File:English language distribution.svg|thumb|upright=1.5|English language distribution | |||

| {{legend|#346699|Majority native language}} | |||

| {{legend|#99ccff|Official or administrative language, but not native language}} | |||

| ]] | |||

| English is sometimes described as the foremost global lingua franca, being used as a working language by individuals of diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds in a variety of fields and international organizations to communicate with one another.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web|date=2017-04-25|title=The Linguistic Colonialism of English|url=https://brownpoliticalreview.org/2017/04/linguistic-colonialism-english/|access-date=2021-04-24|website=Brown Political Review|language=en-US|archive-date=24 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210424084057/https://brownpoliticalreview.org/2017/04/linguistic-colonialism-english/|url-status=live}}</ref> English is the ] in the world, primarily due to the historical global influence of the ] and the ].<ref>{{e22|eng|English}}</ref> It is a ] and many other international and regional organizations and has also become the ''de facto'' language of ], ], ], ], ], ] and the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/18/books/review/the-rise-of-english-rosemary-salomone.html|title=How the English Language Conquered the World|last=Chua|first=Amy|website=]|date=18 January 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220301222132/https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/18/books/review/the-rise-of-english-rosemary-salomone.html|archive-date=1 March 2022|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Hindi - Urdu=== | |||

| {{see|Hindustani language}} | |||

| ] or ]-], is commonly spoken in India and Pakistan. It encompasses two ] ]s in the form of the official languages of ] and ], as well as several ]s. ] is one of the official languages and lingua franca of ], and ] is the official language and lingua franca of ]. ] is also an official language in ]. | |||

| However, whilst the words and much of the speaking may sound similar, the writing styles are completely different, both using different charactersets altogether. | |||

| When the ] became a colonial power, English served as the lingua franca of the colonies of the ]. In the post-colonial period, most of the newly independent nations which had many ]s opted to continue using English as one of their official languages such as ] and ].<ref name=":3" /> In other former colonies with several official languages such as ] and ], English is the primary medium of education and serves as the lingua franca among citizens.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Tan|first=Jason|date=1997|title=Education and Colonial Transition in Singapore and Hong Kong: Comparisons and Contrasts|journal=Comparative Education|volume=33|issue=2|pages=303–312|doi=10.1080/03050069728587}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | chapter-url=https://ewave-atlas.org/languages/68 | title=The Electronic World Atlas of Varieties of English | chapter=Pure Fiji English (Basilectal FijiE) | year=2020 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://fijiluxuryvacation.com/everyone-speak-english-in-fiji/ |title=Why Does Everyone Speak English in Fiji? |work=Raiwasa Private Resort |url-status=dead |access-date=5 December 2023 |date=26 February 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220827143620/https://fijiluxuryvacation.com/everyone-speak-english-in-fiji/ |archive-date=2022-08-27 }}</ref> | |||

| ===]=== | |||

| Ilokano is natively spoken in ], northwest Philippines. ] migrated to ], Cordillera, ], and ] until it is now the lingua franca of northern Philippines. | |||

| Even in countries not associated with the ], English has emerged as a lingua franca in certain situations where its use is perceived to be more efficient to communicate, especially among groups consisting of native speakers of many languages. In ], the medical community is primarily made up of workers from countries without English as a native language. In medical practices and hospitals, nurses typically communicate with other professionals in English as a lingua franca.<ref name="melf">{{cite web|url=http://bild-lida.ca/journal/volume_2_1_2018/tweedie_johnson/|title=Listening instruction and patient safety: Exploring medical English as a lingua franca (MELF) for nursing education|first1=Gregory|last1=Tweedie|first2=Robert|last2=Johnson|access-date=6 January 2018|archive-date=3 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200803074912/http://bild-lida.ca/journal/volume_2_1_2018/tweedie_johnson/|url-status=live}}</ref> This occurrence has led to interest in researching the consequences of the medical community communicating in a lingua franca.<ref name="melf"/> English is also sometimes used in ] between people who do not share one of Switzerland's ], or with foreigners who are not fluent in the local language.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/english-as-a-common-language-in-switzerland--a-positive-or-a-problem-/46494332 |first=Thomas |last=Stephens |access-date=4 December 2023 |title=English as a common language in Switzerland: a positive or a problem? |date=4 April 2021 }}</ref> In the ], the use of English as a lingua franca has led researchers to investigate whether a ] dialect has emerged.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Mollin|first1=Sandra|title=Euro-English assessing variety status|date=2005|publisher=Narr|location=Tübingen|isbn=382336250X}}</ref> In the fields of technology and science, English emerged as a lingua franca in the 20th century.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1109/MC.2017.3001253 |title=The Lingua Franca of Technology |year=2017 |last1=Alan Grier |first1=David |journal=Computer |volume=50 |issue=8 |page=104 }}</ref> English has also significantly ] many other languages.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Mikanowski |first=Jacob |date=2018-07-27 |title=Behemoth, bully, thief: how the English language is taking over the planet |url=https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/jul/27/english-language-global-dominance |access-date=2024-12-15 |work=The Guardian |language=en-GB |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> | |||

| ===Malay and Indonesian=== | |||

| In the ], during the ], ] was used as a ''lingua franca'' in the ], by the locals as much as by the traders and artisans that stopped at ] via the ]. Nowadays, ] is used mostly in ] (officially called ]) and ], as well as - but to a lesser extent in - ] (one out of their four official languages; a "street" version of Malay - ] was the ''lingua franca'' in Singapore prior to the introduction of English as a working and instructional language, and remains so for the elder generation). | |||

| ====Spanish==== | |||

| However, ], a standardized variety of ], serves as a ''lingua franca'' throughout ] and ]. While Indonesia counts several hundred different languages, ], the official language of Indonesia, is their vehicular language. | |||

| [[File:Map-Hispanophone World.svg|thumb|upright=1.5|Spanish language distribution | |||

| {{legend|#045a8d|Official language}} | |||

| {{legend|#0674b6|Co-official language}} | |||

| {{legend|#9bbae1|Culturally important or secondary language (> 20% of the population)}} | |||

| ]] | |||

| The Spanish language spread mainly throughout the ], becoming a lingua franca in the territories and colonies of the ], which also included parts of Africa, Asia, and Oceania. After the breakup of much of the empire in the Americas, its function as a lingua franca was solidified by the governments of the newly independent nations of what is now ].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Stavans |first1=Ilan |title=The Spanish Language in Latin America since Independence |url=https://oxfordre.com/latinamericanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.001.0001/acrefore-9780199366439-e-371 |website=Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History |access-date=2 June 2021 |language=en |doi=10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.371 |date=2017-04-26|isbn=978-0-19-936643-9 }}</ref> While its usage in Spain's Asia-Pacific colonies has largely died out, Spanish became the lingua franca of what is now ], being the main language of government and education and is spoken by the vast majority of the population.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Granda|first=Germán de|title=El Español en Tres Mundos: Retenciones y Contactos Lingüísticos en América y África|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pasdAQAAIAAJ|date=1 January 1991|publisher=Universidad de Valladolid, Secretariado de Publicaciones|isbn=9788477622062|language=es}}</ref> | |||

| Due to large numbers of immigrants from Latin America in the second half of the 20th century and resulting influence, Spanish has also emerged somewhat as a lingua franca in parts of the ] and southern ], especially in communities where native Spanish speakers form the majority of the population.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Macías|first=Reynaldo|date=2014|title=Spanish as the Second National Language of the United States: Fact, Future, Fiction, or Hope?|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/43284061|journal=Review of Research in Education|volume=38|pages=33–57|doi=10.3102/0091732X13506544 |jstor=43284061 |s2cid=143648085 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Lynch|first=Andrew|date=2023|title=Heritage language socialization at work: Spanish in Miami|journal=Journal of World Languages|volume=9|issue=1|pages=111–132 |doi=10.1515/jwl-2022-0048 |s2cid=255570955 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ===Persian=== | |||

| {{see|Persian language}} | |||

| Persian served as the lingua franca of the eastern Islamic world and became the second lingua franca of the Islamic World.<ref>Dr Seyyed Hossein Nasr, ''Islam: Religion, History, and Civilization'', HarperCollins,Published 2003</ref> Besides serving as the state and administrative language in many Islamic dynasties, some of which included ], ], ], ]s, ], ] and early ], Persian cultural and political forms, and often the Persian language were used by the cultural elites from the Balkans to India.<ref>Robert Famighetti, ''The World Almanac and Book of Facts'',World Almanac Books, 1998, pg 582</ref> | |||

| ]'s assessment of the role of the Persian language is worth quoting in more detail: | |||

| <blockquote>''In the Iranic world, before it began to succumb to the process of Westernization, the New Persian language, which had been fashioned into literary form in mighty works of art. . . gained a currency as a lingua franca; and at its widest, about the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries of the Christian Era, its range in this role extended, without a break, across the face of South-Eastern Europe and South-Western Asia''. <ref>Arnold J. Toynbee, A Study of History,V, pp. 514-15</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Persian remains the lingua franca in its native homelands of ], ] and ] and was the lingua franca of India before the British conquest. It is still understood by many intellectuals of ] and ]. | |||

| At present it is the second most used language in international trade, and the third most used in politics, diplomacy and culture after English and French.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221017152438/http://www.quadernsdigitals.net/index.php?accionMenu=secciones.VisualizaArticuloSeccionIU.visualiza&proyecto_id=361&articuloSeccion_id=4463 |date=17 October 2022}} – Copyright 2003 Quaderns Digitals Todos los derechos reservados ISSN 1575-9393.</ref> | |||

| Persian is also said to have some sort of ]. | |||

| It is also one of the most taught foreign languages throughout the world<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210206042553/https://www.languagemagazine.com/2019/11/18/spanish-in-the-world/ |date=6 February 2021}}, ''Language Magazine'', 18 November 2019.</ref> and is also one of the ]. | |||

| ===Sanskrit=== | |||

| {{see|Sanskrit}} | |||

| Sanskrit was widely used across ], ], ] and ] at various times in ] and ] history; it has religious significance for all those religious traditions that arose from the ]. | |||

| === |

====French==== | ||

| [[File:Map-Francophone World.svg|thumb|upright=1.5|French language distribution | |||

| {{legend|#0049a2|Majority native language}} | |||

| {{legend|#006aFF|Official language, but not a majority native language}} | |||

| {{legend|#8ec3ff|Administrative or cultural language}} | |||

| ]] | |||

| French is sometimes regarded as the first global lingua franca, having supplanted ] as the prestige language of politics, trade, education, diplomacy, and military in ] Europe and later spreading around the world with the establishment of the ].<ref name="Wright">{{cite journal|last=Wright|first=Sue|date=2006|title=French as a lingua franca|url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/annual-review-of-applied-linguistics/article/abs/french-as-a-lingua-franca/709F93AD0A5A7E7162C6E170FCA59E43|journal=Annual Review of Applied Linguistics|volume=26|pages=35–60|doi=10.1017/S0267190506000031|doi-broken-date=1 November 2024 }}</ref> With ] emerging as the leading political, economic, and cultural power of Europe in the 16th century, the language was adopted by royal courts throughout the continent, including the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Russia, and as the language of communication between European academics, merchants, and diplomats.<ref>{{cite book |title=When The World Spoke French |author=Marc Fumaroli |translator=Richard Howard |year=2011 |publisher=New York Review of Books |isbn=978-1590173756 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/whenworldspokefr00fuma }}</ref> With the expansion of Western colonial empires, French became the main language of diplomacy and international relations up until ] when it was replaced by English due the rise of the ] as the leading ]. Stanley Meisler of the '']'' said that the fact that the ] was written in English as well as French was the "first diplomatic blow" against the language.<ref>{{cite news|last=Meisler|first=Stanley|title=Seduction Still Works : French—a Language in Decline|newspaper=The Los Angeles Times|date=1 March 1986|access-date=18 October 2021|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1986-03-01-mn-13048-story.html|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150702203738/http://articles.latimes.com/1986-03-01/news/mn-13048_1_french-language/2|archive-date=2 July 2015}}</ref> Nevertheless, it remains the second most used language in international affairs and is one of the ].<ref name="andaman.org"> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080312042140/http://www.andaman.org/BOOK/reprints/weber/rep-weber.htm |date=12 March 2008 }} ''Top Languages''. Retrieved 11 April 2011.</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pya2KY8upAUC&pg=PA2 |title=The French Language Today: A Linguistic Introduction |last1=Battye |first1=Adrian |last2=Hintze |first2=Marie-Anne |last3=Rowlett |first3=Paul |publisher=Taylor & Francis |year=2003 |language=en |isbn=978-0-203-41796-6 |access-date=19 March 2022 |archive-date=17 October 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221017152354/https://books.google.com/books?id=pya2KY8upAUC&pg=PA2 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>, ''Ask UN'', 23 December 2023.</ref> | |||

| Tetum, official language of ] (along with ]), is a lingua franca of ] island. | |||

| As a legacy of French and ] colonial rule, most former colonies of these countries maintain French as an official language or lingua franca due to the many indigenous languages spoken in their territory. Notably, in most Francophone ] and ]n countries, French has transitioned from being only a lingua franca to the native language among some communities, mostly in urban areas or among the elite class.<ref>{{Cite news|date=2019-04-07|title=Why the future of French is African|language=en-GB|work=BBC News|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-47790128|access-date=2021-04-24|archive-date=11 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210411215818/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-47790128|url-status=live}}</ref> In other regions such as the French-speaking countries of the ] (], ], ], and ]) and parts of the ], French is the lingua franca in professional sectors and education, even though it is not the native language of the majority.<ref name="Maamri1013">Maamri, Malika Rebai. "." () ''International Journal of Arts and Sciences''. 3(3): 77 – 89 (2009) CD-ROM. {{ISSN|1944-6934}} p. 10 of 13</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Stevens |first=Paul |title=Modernism and Authenticity as Reflected in Language Attitudes : The Case of Tunisia |publisher=Civilisations |volume=30 |issue=1/2 |year=1980 |pages=37–59 |jstor=41802986 |url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/41802986 }}</ref><ref>Felicien, Marie Michelle. , ''Global Press Journal'', 13 November 2019</ref> | |||

| ==African languages== | |||

| ===Hausa=== | |||

| ] is widely spoken through Nigeria and Niger and recognised in neighbouring states (], ], ] etc). The reason for this is that Hausa people used to be traders who led caravans with goods (cotton, leather, slaves, food crops etc.) through the whole West African region, from the Niger Delta to the Atlantic shores at the very west edge of Africa. They also reached North African states through Trans-Saharan routes. Thus trade deals in ] in modern Mali, ], ], ] in Northern Africa, and other trade centers were often concluded in Hausa. | |||

| French continues to be used as a lingua franca in certain cultural fields such as ], ], and ].<ref>Notaker, Henry. , excerpt from ''A History of Cookbooks From Kitchen to Page over Seven Centuries'', University of California Press, 13 September 2017.</ref><ref name="Wright"></ref> | |||

| ===Swahili=== | |||

| ] is used throughout large parts of ] as a lingua franca, despite being the mother tongue of a relatively small ethnic group on the East African coast and nearby islands in the ]. At least as early as the late eighteenth century, Swahili was used along trading and slave routes that extended west across Lake Tanganyika and into the present-day ]. Swahili rose in prominence throughout the colonial era, and has become the predominant African language of ] and ]. Some contemporary members of non-Swahili ethnic groups speak Swahili more often than their mother tongues, and many choose to raise their children with Swahili as their first language, leading to the possibility that several smaller East African languages will fade as Swahili transitions from being a regional lingua franca to a regional ]. | |||

| As a consequence of ], French has been increasingly used as a lingua franca in the ] and its institutions either alongside or, at times, in place of English.<ref>Chazan, Guy and Jim Brunsden. , ''Financial Times'', 28 June 2016.</ref><ref>Rankin, Jennifer. , '']'', 5 May 2017.</ref> | |||

| ===Zulu=== | |||

| ] has eleven ], however the mutual intelligibility of many ] (Zulu, Xhosa, Swazi and Ndebele) has meant that ] is increasingly becoming a lingua franca throughout Eastern South Africa, including the major cities of Durban and Johannesburg. Zulu is the first language of ten million people, but is spoken as a second language by over 25 million in the region and is now the most commonly understood language in the country. | |||

| === |

====German==== | ||

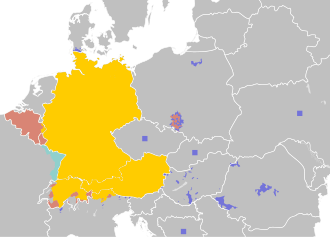

| [[File:Legal status of German in Europe.svg|thumb|right|upright=1.5| | |||

| ], also known as ''Pulaar'' or ''Fulfulde'' depending on the region, is the language of the ] – who in turn are known under the various names of Fula or Fulani or Peuls or Fulbe or ] or ]. Fula is spoken in all countries directly south of the Sahara (north of ], ], ], ], ]…). It is spoken mainly by Fula people, but is also used as a lingua franca by several populations of various origin, throughout Western Africa.{{Fact|date=April 2007}} | |||

| Legal statuses of German in Europe: | |||

| {{legend|#ffcc00|"German ]": German is (co-)official language and first language of the majority of the population.}} | |||

| {{legend|#d98575|German is a co-official language, but not the first language of the majority of the population.}} | |||

| {{legend|#7373d9|German (or a German dialect) is a legally recognized minority language (squares: geographic distribution too dispersed/small for map scale).}} | |||

| {{legend|#30efe3|German (or a variety of German) is spoken by a sizable minority, but has no legal recognition.}}]] | |||

| ] is used as a lingua franca in Switzerland to some extent; however, English is generally preferred to avoid favoring it over the three other official languages. ] used to be the Lingua franca during the late ] till the mid-15th century periods, in the ] and the ] when extensive trading was done by the ] along the Baltic and North Seas. German remains a widely studied language in Central Europe and the Balkans, especially in ]. It is recognized as an official language in countries outside of Europe, specifically ]. German is also one of the ]s of the EU along English and French, but it is used less in that role than the other two. | |||

| ===Manding=== | |||

| The largely interintelligible ] of West Africa serve as lingua francas in various places. For instance ] is the most widely spoken language in ], and ] (almost the same as Bambara) is commonly used in western ] and northern ]. Manding languages have long been used in regional commerce, so much so that the word for trader, ''jula'', was applied to the language currently known by the same name. Other varieties of Manding are used in several other countries, such as ], ], and ]. | |||

| === |

====Chinese==== | ||

| Today, ] is the lingua franca of ] and ], which are home to many mutually unintelligible ] and, in the case of Taiwan, indigenous ]. Among many ] communities, ] is often used as the lingua franca instead, particularly in Southeast Asia, due to a longer history of immigration and trade networks with southern China, although Mandarin has also been adopted in some circles since the 2000s.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Li|first=David|date=2006|title=Chinese as a lingua franca in Greater China|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231791003|journal=Annual Review of Applied Linguistics|volume=26|pages=149–176|doi=10.1017/S0267190506000080|doi-broken-date=1 November 2024 }}</ref> | |||

| The ] is a lingua franca developed for intertribal trading in the ]. It is based on the Northern ] spoken by the Sango people of the Democratic Republic of the Congo but with a large vocabulary of French loan words. | |||

| ====Arabic==== | |||

| ===]=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] was used as a lingua franca across the Islamic empires, whose sizes necessitated a common language, and spread across the Arab and Muslim worlds.<ref>{{Cite web|last1=M. A.|first1=Geography|last2=B. A.|first2=English and Geography|title=How Lingua Franca Helps Different Cultures to Communicate|url=https://www.thoughtco.com/lingua-franca-overview-1434507|access-date=2021-04-24|website=ThoughtCo|language=en|archive-date=17 October 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221017152440/https://www.thoughtco.com/lingua-franca-overview-1434507|url-status=live}}</ref> In ] and parts of ], both of which are countries where multiple official languages are spoken, Arabic has emerged as a lingua franca in part thanks to the population of the region being predominantly Muslim and Arabic playing a crucial role in Islam. In addition, after having fled from Eritrea due to ] and gone to some of the nearby Arab countries, Eritrean emigrants are contributing to Arabic becoming a lingua franca in the region by coming back to their homelands having picked up the Arabic language.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Simeone-Sinelle|first=Marie-Claude|date=2005|title=Arabic Lingua Franca in the Horn of Africa|journal=Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics|volume=2|via=Academia.edu}}</ref> | |||

| Wolof is a more widely spoken lingua franca of The Gambia and Senegal, although English and French, the official languages of The Gambia and Senegal, are the lingua francas of the urban areas of the 2 countries. | |||

| ====Russian==== | |||

| == Amerindian languages == | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Mobilian Jargon=== | |||

| Russian is in use and widely understood in ] and the ], areas formerly part of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union. Its use remains prevalent in many ]. Russian has some presence as a minority language in the ] and some other states in Eastern Europe, as well as in pre-] China.{{citation needed|date=October 2023}} It remains the official language of the ]. Russian is also one of the six official languages of the United Nations.<ref name="un.org">{{cite web|url=https://www.un.org/Depts/DGACM/faq_languages.htm |title=Department for General Assembly and Conference Management – What are the official languages of the United Nations?|access-date=25 January 2008|publisher=United Nations|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20071012035848/http://www.un.org/Depts/DGACM/faq_languages.htm |archive-date=12 October 2007|url-status=dead}}</ref> Since the ], its use has declined in post-Soviet states. Parts of the Russian speaking minorities outside Russia have either emigrated to Russia or assimilated into their countries of residence by learning the local language, which they now prefer to use in daily communication. | |||

| The ] was developed and used along the Gulf Coast from Florida to Texas. It was a creole named for the ] (Mobile) tribe, which spoke ] (Alabama), but it was more based on ]. | |||

| In ]an countries that were members of the ], where Russian was only a political language used in international communication and where there was no Russian minority, the Russian language practically does not exist, and in schools it was replaced by English as the primary foreign language. | |||

| ===Tupi=== | |||

| The ] served as the ''lingua franca'' of Brazil among speakers of the various indigenous languages, mainly in the coastal regions. Tupi as a lingua franca, and as recorded in colonial books, was in fact a creation of the Portuguese, who assembled it from the similarities between the coastal indigenous Tupi-guarani languages. The language served the Jesuit priests as a way to teach natives, and it was widely spoken by Europeans. It was the predominant language spoken in Brazil until 1758, when the Jesuits were expelled from Brazil by the Portuguese government and the use and teaching of Tupi was banned.<ref> essay in Portuguese.</ref> Since then, Tupi as Lingua Franca was quickly replaced by Portuguese, although Tupi-guarani family languages are still spoken by small native groups in Brazil. | |||

| === |

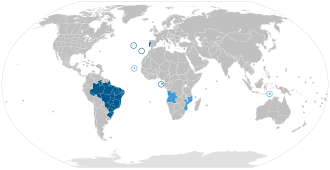

====Portuguese==== | ||

| ] world{{legend|#002375|Native language}} | |||

| As the ] rose to prominence in ], the imperial language ] became the most widely spoken language in the western regions of the continent. Even among tribes that were not absorbed by the empire Quechua still became an important language for trade because of the empire's influence. Even after the ] of ] Quechua for a long time was the most common language. Today it is still widely spoken although it has given way to Spanish as the more common lingua franca. | |||

| {{legend|#1886FE|Official and administrative language}} | |||

| {{legend|#79BDFF|Cultural or secondary language}}]] | |||

| ] served as lingua franca in the Portuguese Empire, Africa, South America and Asia in the 15th and 16th centuries. When the Portuguese started exploring the seas of Africa, America, Asia and Oceania, they tried to communicate with the natives by mixing a Portuguese-influenced version of lingua franca with the local languages. When Dutch, English or French ships came to compete with the Portuguese, the crews tried to learn this "broken Portuguese". Through a process of change the lingua franca and Portuguese lexicon was replaced with the languages of the people in contact. Portuguese remains an important lingua franca in the ], ], and to a certain extent in ] where it is recognized as an official language alongside Chinese though in practice not commonly spoken. Portuguese and Spanish have a certain degree of ] and ]s such as ] are used {{Cn|date=July 2024}} to facilitate communication in areas like the border area between Brazil and Uruguay. | |||

| ==Creoles== | |||

| Various ] languages have been used in many locations and times as a common trade speech. They can be based on English, French, Chinese, or indeed any other language. A pidgin is defined by its use as a lingua franca, between populations speaking other mother tongues. When a pidgin becomes a population's first language, then it is called a ]. | |||

| === |

====Hindustani==== | ||

| ] (based on ]) serves as the ''lingua franca.'']] | |||

| ] is largely spoken in ] as a ''lingua franca''. It developed as an English-based creole with influences from local languages and to a smaller extent ] or ] and ]. Tok Pisin originated as a ] in the 19th century, hence the name 'Tok Pisin' from 'Talk Pidgin', but has now evolved into a modern language. | |||