| Revision as of 02:42, 9 December 2008 editShrampes (talk | contribs)111 edits this source is not compliant with WP:V← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:20, 21 December 2024 edit undoGreenC bot (talk | contribs)Bots2,547,810 edits Rescued 1 archive link; reformat 1 link. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:USURPURL and JUDI batch #20 | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Processed corn syrup}} | |||

| '''High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS)''' - in Europe called '''isoglucose'''<ref>Oxford Dictionary of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, | |||

| {{Redirect-distinguish-text|HFCS|]}} | |||

| Oxford University Press, 2006 (page 311)</ref> - comprises any of a group of ]s that has undergone ] processing to increase its ] content, and is then mixed with pure corn syrup (100% ]), becoming a high-fructose corn syrup. HFCS is used in various types of food, from soft drinks and yogurt to cookies, salad dressing and tomato soup.<ref></ref> | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2023}} | |||

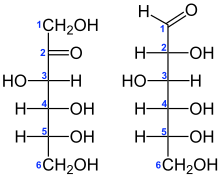

| ]s) of fructose (left) and glucose (right)]] | |||

| Most common types of High-fructose corn syrup are: HFCS 90 (mostly for making HFCS 55), approximately 90% fructose and 10% glucose; HFCS 55 (mostly used in soft drinks), approximately 55% fructose and 45% glucose; and HFCS 42 (used in most foods and baked goods), approximately 42% fructose and 58% glucose.<ref>University of Maryland press release Accessed 2007-11-15</ref> | |||

| '''High-fructose corn syrup''' ('''HFCS'''), also known as '''glucose–fructose''', '''isoglucose''' and '''glucose–fructose syrup''',<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.aaf-eu.org/factsheet-on-glucose-fructose-syrups-and-isoglucose/ | title=Factsheet on Glucose Fructose Syrups and Isoglucose |author=European Starch Association| date=10 June 2013 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title=Glucose-fructose syrup: How is it produced? |url=http://www.eufic.org/en/food-production/article/glucose-fructose-how-is-it-produced-infographic | publisher=European Food Information Council (EUFIC) |access-date=9 February 2024 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170517230154/http://www.eufic.org/en/food-production/article/glucose-fructose-how-is-it-produced-infographic |archive-date=17 May 2017}}</ref> is a ] made from ]. As in the production of conventional ], the starch is broken down into glucose by enzymes. To make HFCS, the corn syrup is further ] by ] to convert some of its ] into ]. HFCS was first marketed in the early 1970s by the Clinton Corn Processing Company, together with the Japanese Agency of Industrial Science and Technology, where the enzyme was discovered in 1965.<ref name=WhiteChapter2014/>{{rp|5}} | |||

| The process by which HFCS is produced was first developed by Richard Off. Marshalle and | |||

| Earl P. Kooi in 1927.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Marshall et al. | title = Enzymatic Conversion of d-Glucose to d-Fructose | journal = Science | year = 1957 | volume = 125 | issue = 3249 | pages = 648 | doi = 10.1126/science.125.3249.648 | pmid = 13421660}}</ref> The industrial production process was refined by Dr. Y. Takasaki at Agency of Industrial Science and Technology of Ministry of International Trade and Industry of Japan in 1965-1970. HFCS was rapidly introduced to many processed foods and ]s in the U.S. from about 1975 to 1985. | |||

| As a sweetener, HFCS is often compared to ], but manufacturing advantages of HFCS over sugar include that it is <!-- {{how?|date=March 2021}} Here's how, from the 22 April 2009 Journal of Nutrition article ff.: "ease of handling—beverage production with dry, bulk sugar was labor and energy intensive. HFCS could be pumped from the delivery vehicle directly into a holding tank and from there to the mixing tank. Dilution to desired solids was a simple matter of adding water and agitation" --> cheaper.<ref name=white09/> "HFCS 42" and "HFCS 55" refer to dry weight fructose compositions of 42% and 55% respectively, the rest being glucose.<ref name="fda">{{cite web|url=https://www.fda.gov/food/food-additives-petitions/high-fructose-corn-syrup-questions-and-answers|title=High Fructose Corn Syrup: Questions and Answers|publisher=US Food and Drug Administration|date=4 January 2018|access-date=19 August 2019}}</ref> HFCS 42 is mainly used for ]s and ]s, whereas HFCS 55 is used mostly for production of ]s.<ref name=fda/> | |||

| Per relative ], HFCS 55 is comparable to table sugar (]), a ] of fructose and glucose.<ref></ref> That makes it useful to food manufacturers as a substitute for ] in soft drinks and processed foods. HFCS 90 is sweeter than sucrose, HFCS 42 is less sweet than sucrose. | |||

| The United States ] (FDA) states that it is not aware of evidence showing that HFCS is less safe than traditional sweeteners such as ] and ].<ref name=fda/> Uses and exports of HFCS from American producers have grown steadily during the early 21st century.<ref name=fas/> | |||

| ==Use as a replacement for sugar== | |||

| Since its introduction, HFCS has begun to replace sugar in various processed foods in the USA and Canada.<ref>(Bray, 2004 & U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Sugar and Sweetener Yearbook series, Tables 50–52)</ref><ref></ref> | |||

| The main reasons for this switch are:<ref>(White JS. 1992. Fructose syrup: production, properties and applications, in FW Schenck & RE Hebeda, eds, Starch Hydrolysis Products – Worldwide Technology, Production, and Applications. VCH Publishers, Inc. 177-200)</ref> | |||

| * HFCS is somewhat cheaper in the United States due to a combination of corn subsidies and sugar tariffs.<ref>Pollan, M., , NY Times Magazine, 12 Oct. 2003.</ref> Since the mid-90s US Federal subsidies to corn growers have amounted to $40 billion.<ref>Encyclopedia of Junk Food and Fast Food, | |||

| Andrew F. Smith, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006 (page 258)</ref> | |||

| * HFCS is easier to blend and transport because it is a liquid.<ref>(Hanover LM, White JS. 1993. Manufacturing, composition, and applications of fructose. Am J Clin Nutr 58(suppl 5):724S-732S.)</ref> | |||

| == Food == | |||

| ==Comparison to other sugars== | |||

| In the United States, HFCS is among the sweeteners that have mostly replaced ] (table sugar) in the food industry.<ref>(Bray, 2004 & U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Sugar and Sweetener Yearbook series, Tables 50–52)</ref><ref name=white-straight/> Factors contributing to the increased use of HFCS in food manufacturing include production quotas of domestic sugar, import ]s on foreign sugar, and ], raising the price of sucrose and reducing that of HFCS, creating a manufacturing-cost advantage among sweetener applications.<ref name=white-straight/><ref>{{cite web |last=Engber |first=Daniel |url=http://www.slate.com/id/2216796 |title=Dark sugar: The decline and fall of high-fructose corn syrup |work=Slate Magazine |publisher=Slate.com |date=28 April 2009 |access-date=6 November 2010}}</ref> In spite of having a 10% greater fructose content,<ref name="Goran 55–64">{{Cite journal|last1=Goran|first1=Michael I.|last2=Ulijaszek|first2=Stanley J.|last3=Ventura|first3=Emily E.|date=1 January 2013|title=High fructose corn syrup and diabetes prevalence: A global perspective|journal=Global Public Health|volume=8|issue=1|pages=55–64|doi=10.1080/17441692.2012.736257|issn=1744-1692|pmid=23181629|s2cid=15658896}}</ref> the relative ] of HFCS 55, used most commonly in soft drinks,<ref name=fda/> is comparable to that of sucrose.<ref name=white-straight/> HFCS provides advantages in food and beverage manufacturing, such as simplicity of formulation, stability, and enabling processing efficiencies.<ref name=fda/><ref name=white-straight/><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Hanover LM, White JS | year = 1993 | title = Manufacturing, composition, and applications of fructose | journal = American Journal of Clinical Nutrition | volume = 58 | issue = suppl 5|pages=724S–732S |pmid=8213603| doi = 10.1093/ajcn/58.5.724S | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ===Cane and beet sugar=== | |||

| ] and ] are both relatively pure ]. While the glucose and fructose which are the two components of HFCS are ], sucrose is a ] ''composed'' of glucose and fructose linked together with a relatively weak glycosidic bond. A molecule of sucrose (with a chemical formula of C<sub>12</sub>H<sub>22</sub>O<sub>11</sub>) can be broken down into a molecule of glucose (C<sub>6</sub>H<sub>12</sub>O<sub>6</sub>) plus a molecule of fructose (also C<sub>6</sub>H<sub>12</sub>O<sub>6</sub> — an ] of glucose) in a weakly acidic environment{{Fact|see http://www.reddit.com/comments/6ulug/corn_syrup_fructose_glucose_sugar_sucrose/c051mdn|date=August 2008}}. Sucrose is broken down during ] into fructose and glucose through ] by the enzyme ], by which the body regulates the rate of sucrose breakdown. Without this regulation mechanism, the body has less control over the rate of sugar absorption into the bloodstream. | |||

| HFCS (or standard ]) is the primary ingredient in most brands of commercial "pancake syrup," as a less expensive substitute for ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.consumerreports.org/maple-syrup/5-things-you-need-to-know-about-maple-syrup|title=5 Things You Need to Know About Maple Syrup|access-date=29 September 2016}}</ref> ]s to detect adulteration of sweetened products with HFCS, such as liquid honey, use ] and other advanced testing methods.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.foodsafetymagazine.com/magazine-archive1/augustseptember-2009/advances-in-honey-adulteration-detection/ |title=Advances in Honey Adulteration Detection |publisher=Food Safety Magazine |date=12 August 1974 |access-date=9 May 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Everstine K, Spink J, Kennedy S |title=Economically motivated adulteration (EMA) of food: common characteristics of EMA incidents |journal=J Food Prot |date=April 2013 |volume=76 |issue=4 |pages=723–35 |pmid=23575142 |doi=10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-399 |quote=Because the sugar profile of high-fructose corn syrup is similar to that of honey, high-fructose corn syrup was more difficult to detect until new tests were developed in the 1980s. Honey adulteration has continued to evolve to evade testing methodology, requiring continual updating of testing methods.|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| The fact that sucrose is composed of glucose and fructose units chemically bonded complicates the comparison between cane sugar and HFCS. Sucrose, glucose and fructose are unique, distinct molecules. Sucrose is broken down into its constituent monosaccharides—namely, fructose and glucose—in weakly acidic environments by a process called inversion.<ref>Sugar Confectionery Manufacture, E. B. Jackson, Springer, 1995, ISBN 0834212978 (page 109 and 115)</ref>. This same process occurs in the stomach and in the small intestine during the digestion of sucrose into fructose and glucose. People with ] deficiency cannot digest (break down) sucrose and thus exhibit ].<ref></ref> | |||

| == Production == | |||

| Both HFCS and sucrose have approximately 4 kcal per gram of solid if the HFCS is dried; HFCS has approximately 3 kcal per gram in its liquid form.{{fact}} | |||

| === Process === | |||

| In the contemporary process, corn is milled to extract ] and an "acid-enzyme" process is used, in which the corn-starch solution is acidified to begin breaking up the existing ]s. High-temperature enzymes are added to further metabolize the starch and convert the resulting sugars to fructose.<ref name=Hobbs/>{{rp|808–813}} The first enzyme added is ], which breaks the long chains down into shorter sugar chains (]s). ] is mixed in and converts them to glucose. The resulting solution is filtered to remove protein using ]. Then the solution is demineralized using ]. That purified solution is then run over immobilized xylose isomerase, which turns the sugars to ~50–52% glucose with some unconverted oligosaccharides and 42% fructose (HFCS 42), and again demineralized and again purified using activated carbon. Some is processed into HFCS 90 by liquid ], and then mixed with HFCS 42 to form HFCS 55. The enzymes used in the process are made by ].<ref name=Hobbs>{{cite book|last1=Hobbs|first1=Larry|editor1-last=BeMiller|editor1-first=James N.|editor2-last=Whistler|editor2-first=Roy L.|title=Starch: chemistry and technology|date=2009|publisher=Academic Press/Elsevier|location=London|isbn=978-0-12-746275-2|pages=797–832|edition=3rd|doi=10.1016/B978-0-12-746275-2.00021-5|chapter=21. Sweeteners from Starch: Production, Properties and Uses}}</ref>{{rp|808–813}}<ref name=WhiteChapter2014/>{{rp|20–22}} | |||

| === Composition and varieties === | |||

| ===Honey=== | |||

| HFCS is 24% water, the rest being mainly fructose and glucose with 0–5% unprocessed ].<ref name=Rizkalla>{{Cite journal | last1 = Rizkalla | first1 = S. W. | doi = 10.1186/1743-7075-7-82 | title = Health implications of fructose consumption: A review of recent data | journal = Nutrition & Metabolism | volume = 7 | pages = 82 | year = 2010 | pmid = 21050460 | pmc =2991323 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ] is a mixture of different types of sugars, water, and small amounts of other compounds. Honey typically has a fructose/glucose ratio similar to HFCS 55, as well as containing some sucrose and other sugars. Honey, HFCS and sucrose have the same number of calories, having approximately 4 ] per gram of solid; honey and HFCS both have about 3 kcal per gram in liquid form. Because of its similar sugar profile and its lower price HFCS has been used illegally to "stretch" honey. As a result checks for adulteration no longer test for sugar but instead test for minute quantities of proteins that can be used to differentiate between HFCS and honey <ref>From where I Sit: Essays on Bees, Beekeeping, and Science, Mark L. Winston, | |||

| Cornell University Press, 1998, ISBN 0801484782 (page 109)</ref>. | |||

| The most common forms of HFCS used for food and beverage manufacturing contain fructose in either 42% ("HFCS 42") or 55% ("HFCS 55") by dry weight, as described in the U.S. ] (21 CFR 184.1866).<ref name=fda/> | |||

| ==Production== | |||

| High-fructose corn syrup is produced by milling corn to produce corn starch, then processing that corn starch to yield corn syrup which is almost entirely glucose, and then adding ]s which change the glucose into fructose. The resulting syrup (after enzyme conversion) contains approximately 90% fructose and is HFCS 90. To make the other common forms of HFCS (HFCS 55 and HFCS 42) the HFCS 90 is mixed with 100% glucose corn syrup in the appropriate ratios to form the desired HFCS. The enzyme process which changes the 100% glucose corn syrup into HFCS 90 is as follows: | |||

| # ] is treated with ] to produce shorter chains of sugars called ]s. | |||

| # ] breaks the sugar chains down even further to yield the simple sugar glucose. | |||

| # ] (aka glucose isomerase) converts glucose to a mixture of about 42% fructose and 50–52% glucose with some other sugars mixed in. | |||

| * HFCS 42 (approx. 42% fructose if water were ignored) is used in beverages, processed foods, cereals, and baked goods.<ref name=fda/><ref name="usda14">{{cite web |url=http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/sugar-sweeteners/background.aspx|title=Sugar and Sweeteners: Background |publisher=] Economic Research Service |date=14 November 2014 |access-date=26 May 2015}}</ref> | |||

| While inexpensive alpha-amylase and glucoamylase are added directly to the slurry and used only once, the more costly glucose-isomerase is packed into columns and the sugar mixture is then passed over it, allowing it to be used repeatedly until it loses its activity. This 42–43% fructose glucose mixture is then subjected to a liquid ] step where the fructose is enriched to approximately 90%. The 90% fructose is then back-blended with 42% fructose to achieve a 55% fructose final product. Most manufacturers use carbon absorption for impurity removal. Numerous filtration, ion-exchange and evaporation steps are also part of the overall process. | |||

| * HFCS 55 is mostly used in soft drinks.<ref name=fda/> | |||

| *HFCS 70 is used in filling jellies<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170216006427/en/Japan-Corn-Starch-Ltd.-Releasing-New-High-Fructose|title=Japan Corn Starch Co., Ltd. Releasing the New High-Fructose Corn Syrup, "HFCS 70"!!|date=17 February 2017|website=www.businesswire.com|language=en|access-date=4 December 2019}}</ref> | |||

| ==Commerce and consumption== | |||

| == Measuring concentration of HFCS == | |||

| ] | |||

| The global market for HFCS is expected to grow from $5.9 billion in 2019 to a projected $7.6 billion in 2024.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.marketwatch.com/press-release/high-fructose-corn-syrup-market-2019-industry-research-share-trend-global-industry-size-price-future-analysis-regional-outlook-to-2024-research-report-2019-05-20|title=High Fructose Corn Syrup Market 2019 Industry Research, Share, Trend, Global Industry Size, Price, Future Analysis, Regional Outlook to 2024 Research Report|website=MarketWatch|language=en-US|access-date=4 December 2019}}</ref>{{dubious|date=December 2019}} | |||

| The units of measurement for sugars including HFCS are degrees ] (symbol °Bx). ] is a measurement of the mass ratio of dissolved sugars to water in a liquid. A 25 °Bx solution has 25 grams of sugar per 100 grams of liquid (25% w/w). Or, to put it another way, there are 25 grams of sugar and 75 grams of water in the 100 grams of solution. The Brix measurement was introduced by Antoine Brix. | |||

| === China === | |||

| When an infrared Brix sensor is used, it measures the vibrational frequency of the high-fructose corn syrup molecules, giving a Brix degrees measurement. This will not be the same measurement as Brix degrees using a density or refractive index measurement because it will specifically measure dissolved sugar concentration instead of all dissolved solids. When a refractometer is used, it is correct to report the result as "refractometric dried substance" (RDS). One might speak of a liquid as being 20 °Bx RDS. This is a measure of percent by weight of ''total'' dried solids and, although not technically the same as Brix degrees determined through an infrared method, renders an accurate measurement of sucrose content since the majority of dried solids are in fact sucrose. The advent of in-line infrared Brix measurement sensors have made measuring the amount of dissolved HFCS in products economical using a direct measurement. It also gives the possibility of a direct volume/volume measurement. | |||

| HFCS in China makes up about 20% of sweetener demand. HFCS has gained popularity due to rising prices of sucrose, while selling for a third the price. Production was estimated to reach 4,150,000 tonnes in 2017. About half of total produced HFCS is exported to the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and India.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-corn-sugar/old-foes-sugar-and-corn-syrup-battle-for-lucrative-asian-market-idUSKBN1A50HF|title=Old foes sugar and corn syrup battle for lucrative Asian market|last1=Gu|first1=Hallie|last2=Cruz|first2=Enrico Dela|date=20 July 2017|website=Reuters|access-date=18 November 2019}}</ref> | |||

| === European Union === | |||

| Recently an isotopic method for quantifying sweeteners derived from corn and sugar cane was developed by Jahren et al. which permits measurement of corn syrup and cane sugar derived sweeteners in humans thus allowing dietary assessment of the intake of these substances relative to total intake.<ref></ref> | |||

| In the ] (EU), HFCS is known as isoglucose or glucose–fructose syrup (GFS) which has 20–30% fructose content compared to 42% (HFCS 42) and 55% (HFCS 55) in the United States.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|url=https://www.starch.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/5247.055_starch_eu-fiche-glucose-fructose-webC-1.pdf|title=Glucose-fructose syrup: An ingredient worth knowing|date=June 2017|publisher=Starch EU, Brussels, Belgium|access-date=20 October 2019}}</ref> While HFCS is produced exclusively with corn in the U.S., manufacturers in the EU use corn and wheat to produce GFS.<ref name=":1" /><ref name=":2">{{Cite web|url=https://starch.eu/blog/2017/06/20/starch-europe-position-on-the-end-of-eu-sugar-and-isoglucose-production-quotas/|title=The end of EU sugar production quotas and its impact on sugar consumption in the EU|date=20 June 2017|publisher=Starch EU, Brussels, Belgium|access-date=10 October 2019}}</ref> GFS was once subject to a sugar production quota, which was abolished on 1 October 2017, removing the previous production cap of 720,000 tonnes, and allowing production and export without restriction.<ref name=":2" /> Use of GFS in soft drinks is limited in the EU because manufacturers do not have a sufficient supply of GFS containing at least 42% fructose content. As a result, soft drinks are primarily sweetened by sucrose which has a 50% fructose content.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://starch.eu/blog/2018/07/13/ttps-www-starch-eu-wp-content-uploads-2018-10-2018-07-update-factsheet-on-glucose-fructose-syrups-isoglucose-and-high-fructose-corn-syrup-pdf/#6552bf5a017976b17|title=Updated factsheet on glucose fructose syrups, isoglucose and high fructose corn syrup|date=13 July 2018|publisher=Starch EU, Brussels, Belgium|access-date=20 October 2019}}</ref> | |||

| === Japan === | |||

| ==Sweetener consumption patterns== | |||

| In Japan, HFCS is also referred to as 異性化糖 (iseika-to; isomerized sugar).<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.puntofocal.gov.ar/notific_otros_miembros/jpn208_t.pdf|title=Quality Labeling Standard for Processed Foods|date=27 October 2006|website=Punto Focal|access-date=18 November 2019}}</ref> HFCS production arose in Japan after government policies created a rise in the price of sugar.<ref name="Sweetener Policies in Japan">{{Cite web|url=https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/39233/38024_sss23401.pdf?v=41668|title=Sweetener Policies in Japan|access-date=26 April 2020|archive-date=21 May 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170521134008/https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/39233/38024_sss23401.pdf?v=41668|url-status=dead}}</ref> Japanese HFCS is manufactured mostly from imported U.S. corn, and the output is regulated by the government. For the period from 2007 to 2012, HFCS had a 27–30% share of the Japanese sweetener market.<ref>International Sugar Organization March 2012 .</ref> Japan consumed approximately 800,000 tonnes of HFCS in 2016.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.usdajapan.org/wpusda/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Japan-Trade-Agreements-Affect-US-Sweetener-Confections_Tokyo_Japan_2-5-2019.pdf|title=Japan Trade Agreements Affect US Sweetener Confections|date=5 February 2019|website=US Department of Agriculture Japan|access-date=17 November 2019}}</ref> The United States Department of Agriculture states that HFCS is produced in Japan from U.S. corn. Japan imports at a level of 3 million tonnes per year, leading 20 percent of corn imports to be for HFCS production.<ref name="Sweetener Policies in Japan"/> | |||

| ===In the United States === | |||

| ] | |||

| === Mexico === | |||

| A system of tariffs and sugar quotas imposed in 1977 significantly increased the cost of importing sugar, and producers sought a cheaper alternative. High-fructose corn syrup, derived from corn, is more economical because the American and Canadian prices of sugar are twice the global price of sugar<ref>] </ref> and the price of ] is artificially low due to both government subsidies and dumping on the market as farmers produce more corn annually.<ref></ref><ref></ref> HFCS became an attractive substitute, and is preferred over cane sugar among the vast majority of American food and beverage manufacturers. For instance, soft drink makers like Coca-Cola and Pepsi use sugar in other nations, but switched to HFCS in the U.S. in 1984.<ref></ref> Large corporations, such as ], ] for the continuation of these subsidies.<ref name="cato.org-corporate_welfare">{{cite web |url=http://www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa-241.html |title=Archer Daniels Midland: A Case Study in Corporate Welfare |author=James Bovard |publisher=]|accessdate=2007-07-12}}</ref> | |||

| Mexico is the largest importer of U.S. HFCS.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/DataFiles/53304/Table32.xls?v=2627.9|title=Table 32-U.S. high fructose corn syrup exports, by destinations, 2000–2015|date=20 November 2018|website=United States Department of Agriculture, ]|access-date=11 November 2019|archive-date=1 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200801163004/https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/DataFiles/53304/Table32.xls?v=2627.9|url-status=dead}}</ref> HFCS accounts for about 27 percent of total sweetener consumption, with Mexico importing 983,069 tonnes of HFCS in 2018.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Sugar%20Semi-annual_Mexico%20City_Mexico_9-26-2018.pdf|title=Production Sufficient to Meet U.S. Quota Demand|date=15 April 2019|website=United States Department of Agriculture, ]|access-date=11 November 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/DataFiles/53304/Table34a.xls?v=2944.3|title=Table 34a-U.S. exports of high fructose corn syrup to Mexico|date=6 November 2019|website=United States Department of Agriculture, ]|access-date=11 November 2019}}{{Dead link|date=August 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> Mexico's soft drink industry is shifting from sugar to HFCS which is expected to boost U.S. HFCS exports to Mexico according to a U.S. Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service report.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.world-grain.com/articles/985-mexico-s-hfcs-imports-usage-increasing|title=Mexicos HFCS imports usage increasing {{!}} World-grain.com {{!}} 29 April 2011 09:04|website=www.world-grain.com|access-date=4 December 2019}}</ref> | |||

| On 1 January 2002, Mexico imposed a 20% beverage tax on soft drinks and syrups not sweetened with cane sugar. The United States challenged the tax, appealing to the ] (WTO). On 3 March 2006, the WTO ruled in favor of the U.S. citing the tax as discriminatory against U.S. imports of HFCS without being justified under WTO rules.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/agreements/FTA/AdvisoryCommitteeReports/Agricultural%20Technical%20Advisory%20Committee%20%28ATAC%29%2C%20Sweeteners%20and%20Sweetener%20Products.pdf|title=Report of the Agricultural Technical Advisory Committee (ATAC) for Sweeteners and Sweetener Products|date=27 September 2018|website=]|access-date=17 November 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://ustr.gov/archive/Document_Library/Press_Releases/2006/March/US_Wins_Mexico_Beverage_Tax_Dispute.html|title=U.S. Wins Mexico Beverage Tax Dispute|date=3 March 2006|website=]|access-date=11 November 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Other countries, including Mexico, typically use sugar in soft drinks. Some Americans seek out Mexican Coke in ethnic groceries, because they feel it tastes better or is healthier than Coke made with HFCS, and because they believe it will have less effect on obesity. | |||

| === Philippines === | |||

| The average American consumed approximately 28.4 kg of HFCS in ], versus 26.7 kg of sucrose sugar.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/FoodConsumption/FoodAvailQueriable.aspx | title=U.S. per capita food availability – Sugar and sweeteners (individual) | publisher=] | date=] | accessdate=2007-09-14}}</ref> In countries where HFCS is not used or rarely used, sucrose consumption per person may be higher than in the USA; Sucrose consumption per person from various locations is shown below (]):<ref>WHO Oral Health Country/Area Profile Programme</ref> | |||

| The Philippines was the largest importer of Chinese HFCS. Imports of HFCS would peak at 373,137 tonnes in 2016. Complaints from domestic sugar producers would result in a crackdown on Chinese exports.<ref name=":3" /> On 1 January 2018, the Philippine government imposed a tax of 12 pesos ($.24) on drinks sweetened with HFCS versus 6 pesos ($.12) for drinks sweetened with other sugars.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/philippines-sugar/philippines-drinks-makers-shun-china-corn-syrup-imports-to-avoid-tax-idUSL4N1PP1TW|title=Philippines drinks makers shun China corn syrup imports to avoid tax|date=30 January 2018|website=Reuters|access-date=18 November 2019}}</ref> | |||

| * USA: 32.4 kg | |||

| * EU: 40.1 kg | |||

| * Brazil: 59.7 kg | |||

| * Australia: 56.2 kg | |||

| Of course, in terms of total sugars consumed, the figures from countries where HFCS is not used should be compared to the sum of the sucrose and HFCS figures from countries where HFCS consumption is significant. | |||

| === |

===United States=== | ||

| In the United States, HFCS was widely used in food manufacturing from the 1970s through the early 21st century, primarily as a replacement for sucrose because its sweetness was similar to sucrose, it improved manufacturing quality, was easier to use, and was cheaper.<ref name="white-straight">{{cite journal | last=White | first=John S | title=Straight talk about high-fructose corn syrup: what it is and what it ain't | journal=The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition| volume=88 | issue=6 | date=1 November 2008 | issn=0002-9165 | doi=10.3945/ajcn.2008.25825b | pages=1716S–1721S|pmid=19064536| doi-access=free }}</ref> Domestic production of HFCS increased from 2.2 million tons in 1980 to a peak of 9.5 million tons in 1999.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/sugar-sweeteners/background.aspx#hfcs|title=USDA ERS – Background|website=www.ers.usda.gov|access-date=4 December 2019}}</ref> Although HFCS use is about the same as sucrose use in the United States, more than 90% of sweeteners used in global manufacturing is sucrose.<ref name=white-straight/> | |||

| In the ] (EU), HFCS, known as isoglucose, has been subject to production quotas since 1977.{{Fact|date=September 2008}} Production of isoglucose in the EU has been limited to 507,000 metric tons, equivalent to about 2%-3% of sugar production. Therefore, wide scale replacement of sugar has not occurred in the EU. In Japan, HFCS consumption accounts for one quarter of total sweetener consumption.<ref>{{ja icon}} http://sugar.lin.go.jp/japan/data/j_html/j_1_01.htm</ref><!--Total sugar 2100 kilo ton : HFCS 700 kilo ton--> | |||

| Production of HFCS in the United States was 8.3 million tons in 2017.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/sugar-sweeteners/background/|title=Sugar and sweeteners|date=20 August 2019|publisher=United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service|access-date=15 October 2019}}</ref> HFCS is easier to handle than granulated sucrose, although some sucrose is transported as solution. Unlike sucrose, HFCS cannot be hydrolyzed, but the free fructose in HFCS may produce ] when stored at high temperatures; these differences are most prominent in acidic beverages.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://beverageinstitute.org/article/understanding-high-fructose-corn-syrup/ | title = Understanding High Fructose Corn Syrup | publisher = Beverage Institute}}</ref> Soft drink makers such as ] and ] continue to use sugar in other nations but transitioned to HFCS for U.S. markets in 1980 before completely switching over in 1984.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1984/11/07/business/coke-pepsi-to-use-more-corn-syrup.html|title=Coke, Pepsi to use more corn syrup|last=Daniels|first=Lee A.|date=7 November 1984|newspaper=The New York Times|issn=0362-4331|access-date=20 January 2017}}</ref> Large corporations, such as ], ] for the continuation of government corn subsidies.<ref name="cato.org-corporate_welfare">{{cite web |url=http://www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa-241.html |title=Archer Daniels Midland: A Case Study in Corporate Welfare |author=James Bovard |publisher=] |access-date=12 July 2007 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070711092430/http://www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa-241.html |archive-date=11 July 2007 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Health effects== | |||

| {{POV-section|Clear Bias|date=October 2008}} | |||

| There are indications that soda and sweet drinks provide a greater proportion of daily calories than any other food in the American diet. | |||

| Consumption of HFCS in the U.S. has declined since it peaked at {{convert|37.5|lb|kg|abbr=on}} per person in 1999. The average American consumed approximately {{convert|22.1|lb|kg|abbr=on}} of HFCS in 2018,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/DataFiles/53304/table52.xls?v=5617.5|title=Table 52-High fructose corn syrup: estimated number of per capita calories consumed daily, by calendar year|date=18 July 2019|publisher=]|access-date=17 November 2019|archive-date=1 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200801150239/https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/DataFiles/53304/table52.xls?v=5617.5|url-status=dead}}</ref> versus {{convert|40.3|lb|kg|abbr=on}} of refined cane and beet sugar.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/DataFiles/53304/table51.xls?v=667|title=Table 51-Refined cane and beet sugar: estimated number of per capita calories consumed daily, by calendar year|date=18 July 2019|publisher=]|access-date=17 November 2019|archive-date=1 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200801135413/https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/DataFiles/53304/table51.xls?v=667|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/sugar-and-sweeteners-yearbook-tables/sugar-and-sweeteners-yearbook-tables/#U.S.%20Consumption%20of%20Caloric%20Sweeteners|title=U.S. Consumption of Caloric Sweeteners|publisher=]|access-date=17 November 2019}}</ref> This decrease in domestic consumption of HFCS resulted in a push in exporting of the product. In 2014, exports of HFCS were valued at $436 million, a decrease of 21% in one year, with Mexico receiving about 75% of the export volume.<ref name="fas">{{cite web|url=https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/us-exports-corn-based-products-continue-climb|title=U.S. Exports of Corn-Based Products Continue to Climb|publisher=Foreign Agricultural Service, US Department of Agriculture|date=21 January 2015|access-date=4 March 2017}}</ref> | |||

| Overconsumption of sugars has been linked to adverse health effects, such as obesity, and most of these effects are similar for HFCS and sucrose. There is a correlation between the rise of obesity in the U.S. and the use of HFCS for sweetening beverages and foods.<ref>While HFCS is not toxic and made from natural components, it is the bodies' reaction to this particular sugar that raises questions of its safety. HFCS is not recognized by the body in the same way natural fruit and cane sugars are recognized; triggering an enzyme that gives the feeling of "fullness". As a result, a person can consume a much larger amount of calories without satisfaction. Obesity Rates have increased in the United States (the world's largest consumer of HFCS) since the introduction of this sweetener. Critics of HFCS point out the direct correlation between percentages of increased usage of HFCS in foods and obesity rates in the United States over three decades. Supporters of HFCS attribute this correlation to coincidence. Individuals who have lowered their intake of HFCS have reported weight loss, better control of insulin levels, and improved heart health; each as a result of a lower caloric intake. <ref>, CBC News, November 19, 2008</ref> | |||

| In 2010, the ] petitioned the FDA to call HFCS "corn sugar," but the petition was denied.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofFoods/CFSAN/CFSANFOIAElectronicReadingRoom/ucm305226.htm|title=Response to Petition from Corn Refiners Association to Authorize "Corn Sugar" as an Alternate Common or Usual Name for High Fructose Corn Syrup (HFCS)|publisher=Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, US Food and Drug Administration|author=Landa, Michael M|date=30 May 2012|access-date=3 March 2017}}</ref> | |||

| The controversy largely comes down to whether this is coincidence or a causal relationship. Some critics of HFCS do not claim that it is any worse than similar quantities of sucrose would be, but rather focus on its prominent role in the overconsumption of sugar; for example, encouraging overconsumption through its low cost. Others, like the Corn Refiners Association, claim that high fructose corn syrup "has the same natural sweeteners as table sugar" and is natural.<ref></ref> | |||

| === Vietnam === | |||

| The possible difference in health effects between sucrose and HFCS could come from the difference in chemical make up between them. HFCS 55 (the type most commonly used in soft drinks) is made up of 55% fructose and 45% glucose. By contrast, ] is made up of 50% fructose and 50% glucose, when broken down by adding a water molecule.<ref></ref> | |||

| 90% of Vietnam's HFCS import comes from China and South Korea. Imports would total 89,343 tonnes in 2017.<ref name=":4">{{Cite web|url=https://vietnamnews.vn/economy/448778/sugar-association-seeks-help-against-corn-syrup-imports.html|title=Sugar association seeks help against corn syrup imports|date=28 May 2018|website=Vietnam News|access-date=18 November 2019}}</ref> One ton of HFCS was priced at $398 in 2017, while one ton of sugar would cost $702. HFCS has a zero cent import tax and no quota, while ] under quota has a 5% tax, and white and raw sugar not under quota have an 85% and 80% tax.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web|url=https://english.thesaigontimes.vn/62102/vssa-proposes-self-defense-measure-against-hfcs.html|title=VSSA proposes self-defense measure against HFCS|last=Chanh|first=Trung|date=20 August 2018|website=The Saigon Times|access-date=18 November 2019|archive-date=1 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200801155536/https://english.thesaigontimes.vn/62102/vssa-proposes-self-defense-measure-against-hfcs.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> In 2018, the Vietnam Sugarcane and Sugar Association (VSSA) called for government intervention on current tax policies.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5" /> According to the VSSA, sugar companies face tighter lending policies which cause the association's member companies with increased risk of bankruptcy.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://dtinews.vn/en/news/018/61633/sugar-association-seeks-help-amid-bankruptcy-fears.html|date=10 April 2019|title=Sugar association seeks help amid bankruptcy fears {{!}} DTiNews – Dan Tri International|website=dtinews.vn|access-date=4 December 2019}}</ref> | |||

| == Health == | |||

| Furthermore, the fructose and glucose in HFCS 55 are in the form of separate molecules; by contrast, the fructose and glucose that are contained in sucrose are joined together to form a single molecule (called a ]). This chemical difference may be less significant in many beverages that are sweetened with sucrose. This is because many beverages are strongly acidic, and the acid in the beverage will cause the sucrose to separate into its component parts of glucose and fructose. The amount of sucrose converted will depend on the temperature the beverage is kept at and the amount of time it is kept at this temperature.{{Fact|date=September 2008}} | |||

| {{nutritionalvalue | |||

| | name = High-fructose corn syrup | |||

| | kJ=1176 | |||

| | water=24 g | protein=0 g | fat=0 g | carbs=76 g | sugars=76 g | fiber=0 g | |||

| | sodium_mg=2 | potassium_mg = 0 | iron_mg=0.42 | magnesium_mg=2 | phosphorus_mg=4 | zinc_mg=0.22 | calcium_mg=6 | |||

| | vitB6_mg=0.024 | vitC_mg=0 | riboflavin_mg=0.019 | niacin_mg=0 | pantothenic_mg=0.011 | folate_ug=0 | |||

| | source_usda=1 | |||

| | note= | |||

| }} | |||

| ===Nutrition=== | |||

| There are a number of relevant studies published in ] journals suggesting a link between high fructose diets and adverse health effects. For example, studies on the effect of fructose, as reviewed by Elliot et al.,<ref>{{Cite journal|title=Fructose, weight gain, and the insulin resistance syndrome1|first=Sharon S|last=Elliott|coauthors=Nancy L Keim, Judith S Stern, Karen Teff and Peter J Havel|journal=Am J Clin Nutr.|year=2004|month=April|volume=79|number=4|pages=537–43}}</ref> implicate increased consumption of fructose (due primarily to the increased consumption of sugars but also partly due to the slightly higher fructose content of HFCS as compared to sucrose) in obesity and insulin resistance. ] ''et al.'' found that soft drinks sweetened with HFCS are up to 10 times richer in harmful carbonyl compounds, such as ], than a diet soft drink control.<ref></ref> Carbonyl compounds are elevated in people with ] and are blamed for causing diabetic complications such as foot ulcers and eye and nerve damage;<ref name= "NewScientist">{{cite web | title = Diabetes fears over corn syrup in soda | publisher = New Scientist | date = ] ] | url = http://www.newscientist.com/channel/health/mg19526192.800-diabetes-fears-over-corn-syrup-in-soda.html | accessdate = 2007-11-17}}</ref><ref>Theresa Waldron </ref> | |||

| HFCS is 76% ] and 24% water, containing no fat, ], or ]s in significant amounts. In a 100-gram reference amount, it supplies 281 ], while in one ] of 19 grams, it supplies 53 calories. | |||

| === Obesity and metabolic syndrome === | |||

| Furthermore, a study in mice suggests that fructose increases ].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Jurgens|first=Hella|coauthors=et al.|url=http://www.obesityresearch.org/cgi/content/abstract/13/7/1146|title=Consuming Fructose-sweetened Beverages Increases Body Adiposity in Mice | journal = Obesity Res | volume = 13 | pages = 1146–1156 | year = 2005|doi=10.1038/oby.2005.136|format=abstract }}</ref> Large quantities of fructose stimulate the liver to produce ]s, promotes ] of proteins and induces ].<ref>{{Cite journal | author = Faeh D, Minehira K, Schwarz JM, Periasamy R, Park S, Tappy L | title = Effect of fructose overfeeding and fish oil administration on hepatic de novo lipogenesis and insulin sensitivity in healthy men | journal = DIABETES | volume = 54 | issue = 7 | pages = 1907–1913 | month = July | year = 2005 | pmid=15983189 | url = http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/content/full/54/7/1907 | doi = 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.1907 }}</ref> According to one study, the average American consumes nearly 70 pounds of HFCS per annum, marking HFCS as a major contributor to the rising rates of obesity in the last generation. <ref name= High_fructose_corn_syrup>{{cite news | last = Mariniello| first = J. Martin | title = ''Weight Loss — Revealing The Hidden Secrets'' | language = English | publisher = Obesity Factors In Current Society |date=2007-11-28 | url = http://weightloss.revealthesecret.net| accessdate = 2007-11-28}}</ref> | |||

| The role of fructose in ] has been the subject of controversy, but {{as of|lc=yes|2022}}, there is no scientific consensus that fructose or HFCS has any impact on cardiometabolic markers when substituted for sucrose.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Fattore E, Botta F, Bosetti C |title=Effect of fructose instead of glucose or sucrose on cardiometabolic markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of isoenergetic intervention trials |journal=Nutrition Reviews |volume=79 |issue=2 |pages=209–226 |date=January 2022 |pmid=33029629 |doi=10.1093/nutrit/nuaa077|url=https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article/79/2/209/5919255|type=Systematic review}}</ref><ref name = Allocca>{{cite book | first = M | last = Allocca |author2=Selmi C | year = 2010 | chapter = Emerging nutritional treatments for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | title = Nutrition, diet therapy, and the liver | pages = | isbn = 978-1-4200-8549-5 | publisher = ] |editor1=Preedy VR |editor2=Lakshman R |editor3=Rajaskanthan RS}}</ref> A 2014 ] found little evidence for an association between HFCS consumption and ], ] or fat content.<ref>{{cite journal|pmc=4135494|year=2014|last1=Chung|first1=M|title=Fructose, high-fructose corn syrup, sucrose, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or indexes of liver health: A systematic review and meta-analysis|journal=American Journal of Clinical Nutrition|volume=100|issue=3|pages=833–849|last2=Ma|first2=J|last3=Patel|first3=K|last4=Berger|first4=S|last5=Lau|first5=J|last6=Lichtenstein|first6=A. H.|doi=10.3945/ajcn.114.086314|pmid=25099546}}</ref> | |||

| A 2018 review found that lowering consumption of sugary beverages and fructose products may reduce hepatic fat accumulation, which is associated with ].<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Jensen|first1=Thomas|last2=Abdelmalek|first2=Manal F.|last3=Sullivan|first3=Shelby|last4=Nadeau|first4=Kristen J.|last5=Green|first5=Melanie|last6=Roncal|first6=Carlos|last7=Nakagawa|first7=Takahiko|last8=Kuwabara|first8=Masanari|last9=Sato|first9=Yuka|last10=Kang|first10=Duk-Hee|last11=Tolan|first11=Dean R.|date=May 2018|title=Fructose and Sugar: A Major Mediator of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease|journal=Journal of Hepatology|volume=68|issue=5|pages=1063–1075|doi=10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.019|issn=0168-8278|pmc=5893377|pmid=29408694}}</ref> In 2018, the ] recommended that people limit total added sugar (including maltose, sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup, molasses, cane sugar, corn sweetener, raw sugar, syrup, honey, or fruit juice concentrates) in their diets to nine teaspoons per day for men and six for women.<ref>{{cite web|publisher=American Heart Association|date=17 April 2018|url=https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/sugar/added-sugars|title=Added sugars|quote=The AHA recommendations focus on all added sugars, without singling out any particular types such as high-fructose corn syrup}}</ref> | |||

| A 2007 study also raised concerns of possible liver damage as a result of HFCS in combination with a high fat diet and a sedentary lifestyle.<ref></ref> | |||

| === Safety and manufacturing concerns === | |||

| In contrast to the above studies other papers (some of which were funded by corn refiners or the American Beverage Institute{{Fact|date=November 2008}}) suggest HFCS has no ill health effects. A review supported by ], a large corn refiner which makes a significant profit from the sale of corn-based products, concluded "that HFCS does not appear to contribute to overweight and obesity any differently than do other energy sources."<ref>{{Cite journal|title=A critical examination of the evidence relating high fructose corn syrup and weight gain|author=Forshee et al.|journal=Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition|year=2007|volume=47|number=6|pages=561–582|doi=10.1080/10408390600846457|pmid=17653981|url=http://www.hfcsfacts.com/images/pdf/CriticalReviewsinFSandN47-6-561-582.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| Since 2014, the United States FDA has determined that HFCS is ] (GRAS) as an ],<ref name="gras">{{Cite web|title=CFR – Code of Federal Regulations Title 21: Listing of Specific Substances Affirmed as GRAS. Sec. 184.1866. High fructose corn syrup (amended 1 April 2020)|url=https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=184.1866|access-date=10 January 2021|publisher=US Code of Regulations, Food and Drug Administration|date=23 August 1996}}</ref> and there is no evidence that retail HFCS products differ in safety from those containing alternative nutritive sweeteners. The ] recommended that ] should be limited in the diet.<ref name="white09" /><ref name="fda" /> | |||

| One consumer concern about HFCS is that processing of corn is more complex than used for common sugar sources, such as fruit ]s or ], but all sweetener products derived from ]s involve similar processing steps of ], ], ] treatment, and filtration, among other common steps of sweetener manufacturing from natural sources.<ref name=white09/> In the contemporary process to make HFCS, an "acid-enzyme" step is used in which the corn starch solution is acidified to digest the existing carbohydrates, then enzymes are added to further metabolize the corn starch and convert the resulting sugars to their constituents of fructose and glucose. Analyses published in 2014 showed that HFCS content of fructose was consistent across samples from 80 randomly selected ]s sweetened with HFCS.<ref>{{cite journal|pmc=4285619|year=2014|last1=White|first1=J. S.|title=Fructose content and composition of commercial HFCS-sweetened carbonated beverages|journal=International Journal of Obesity|volume=39|issue=1|pages=176–182|last2=Hobbs|first2=L. J.|last3=Fernandez|first3=S|doi=10.1038/ijo.2014.73|pmid=24798032}}</ref> | |||

| In addition, some of the above-referenced studies have addressed fructose specifically, not sweeteners such as HFCS or sucrose which contain fructose in combination with other sugars. Thus, although they indicate that high fructose intake should be avoided, they don't necessarily indicate that HFCS is worse than sucrose intake, except insofar as HFCS contains 10% more fructose. Studies which have compared HFCS to sucrose (as opposed to pure fructose) find that they have essentially identical physiological effects. For instance, Melanson ''et al.'' (2006), studied the effects of HFCS and sucrose sweetened drinks on blood glucose, insulin, leptin, and ghrelin levels. They found no significant differences in any of these parameters.<ref name="melanson">Melanson K et al. Eating Rate and Satiation. Obesity Society (NAASO) 2006 Annual Meeting. October 20-24, 2006, Hynes Convention Center, Boston, Massachusett </ref> | |||

| Accounts are conflicting however, as another source claims that HFCS actually does affect ], causing the body to not know how to stop eating, or when to start digesting food.<ref></ref> | |||

| One prior concern in manufacturing was whether HFCS contains reactive ] compounds or ] evolved during processing.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/08/070823094819.htm|title=Soda Warning? High-fructose Corn Syrup Linked To Diabetes, New Study Suggests|website=ScienceDaily|date=23 August 2007|access-date=3 March 2017}}</ref> This concern was dismissed, however, with evidence that HFCS poses no dietary risk from these compounds.<ref name="white09">{{cite journal|pmid=19386820|year=2009|last1=White|first1=J. S.|title=Misconceptions about high-fructose corn syrup: Is it uniquely responsible for obesity, reactive dicarbonyl compounds, and advanced glycation endproducts?|journal=Journal of Nutrition|volume=139|issue=6|pages=1219S–1227S|doi=10.3945/jn.108.097998|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| A typical soda contains 23 grams of fructose. <ref></ref>. An average 100g apple contains 5.9 grams of fructose.{{fact}} Therefore, a consumer would need to eat over 3 and a half apples to ingest the fructose contained in one can of soda since fructose concentration is higher in the soda compared to the fruit. Because of this, the levels of fructose in the typical American diet, which consists of many HFCS foods, are on average higher given the high concentration of fructose in HFCS foods and the prevalence of HFCS foods in the American diet. Therefore the studies which show the ill effects of fructose do apply to HFCS when you take into account these considerations. Of course chemically there is no difference between fructose from a fruit or fructose from HFCS, but HFCS being consumed heavily in a diet means American consumers are ingesting more fructose compared to a diet which substitutes HFCS with fruit. | |||

| As late as 2004, some factories manufacturing HFCS used a ] corn processing method which, in cases of applying ] for digesting corn raw material, left trace residues of ] in some batches of HFCS.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Dufault|first=Renee|year=2009|title=Mercury from chlor-alkali plants: measured concentrations in food product sugar|journal=Environmental Health|volume=8|issue=1 |pages=2|doi=10.1186/1476-069X-8-2|pmid=19171026|pmc=2637263 |doi-access=free |bibcode=2009EnvHe...8....2D }}</ref> In a 2009 release,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://corn.org/hfcs-mercury-study-outdated/|title=High Fructose Corn Syrup Mercury Study Outdated; Based on Discontinued Technology|publisher=The Corn Refiners Association|date=26 January 2009|access-date=14 March 2017|archive-date=15 March 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170315085549/http://corn.org/hfcs-mercury-study-outdated/|url-status=dead}}</ref> The Corn Refiners Association stated that all factories in the American industry for manufacturing HFCS had used mercury-free processing over several previous years, making the prior report outdated.<ref name=":0"/> | |||

| Perrigue ''et al.'' (2006) compared the effects of isocaloric servings of colas sweetened with HFCS 45, HFCS 55, sucrose, and aspartame on satiety and subsequent energy intake{{Fact|date=November 2008}}. They found that all of the drinks with caloric sweeteners produced similar satiety responses, and had the same effects on subsequent energy intake. Taken together with Melanson ''et al.'' (2006), this study suggests that there is little or no evidence for the hypothesis that HFCS is different from sucrose in its effects on appetite or on metabolic processes involved in fat storage. | |||

| == Other == | |||

| It should be noted that both the Perrigue ''et al.'' study and the Melanson ''et al.'' study were funded by "the ] and the ]."<ref></ref><ref></ref> suggesting a possible conflict of interest in regards to the study of HFCS. | |||

| === Taste difference === | |||

| Most countries, including Mexico, use sucrose, or table sugar, in soft drinks. In the U.S., soft drinks, such as Coca-Cola, are typically made with HFCS 55. HFCS has a sweeter taste than sucrose. Some Americans seek out drinks such as ] in ethnic groceries because they prefer the taste over that of HFCS-sweetened Coca-Cola.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20041109/news_1b9mexcoke.html|title=Is Mexican Coke the real thing?|date=9 November 2004|work=The San Diego Union-Tribune|author=Louise Chu|agency=Associated Press|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071027080246/http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20041109/news_1b9mexcoke.html|archive-date=27 October 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/nationworld/2002076071_coke29.html |title=Mexican Coke a hit in U.S. |work=The Seattle Times |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629002034/http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/nationworld/2002076071_coke29.html |archive-date=29 June 2011 }}</ref> ] Coca-Cola, sold in the U.S. around the Jewish holiday of ], also uses sucrose rather than HFCS.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.usatoday.com/money/industries/food/2009-04-08-kosher-coke_N.htm|title=Kosher Coke 'flying out of the store'|date=9 April 2009|work=USA Today|access-date=4 May 2010|first1=Duffie|last1=Dixon|archive-date=2 February 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110202121310/http://www.usatoday.com/money/industries/food/2009-04-08-kosher-coke_N.htm|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| === Beekeeping === | |||

| One much-publicized 2004 study found an association between ] and high HFCS consumption, especially from soft drinks.<ref>{{ cite journal | last = Bray | first = George A.| coauthors = Samara Joy Nielsen and Barry M. Popkin | title = Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity | journal = American Journal of Clinical Nutrition | volume = 79 | issue = 4 | pages = 537–543 | month = April | year = 2004 | url = http://www.ajcn.org/cgi/content/full/79/4/537 | pmid = 15051594 | |||

| {{Main|Colony collapse disorder}} | |||

| }}</ref> However, this study provided only correlative data. One of the study coauthors, Dr. Barry M. Popkin, is quoted in the ''New York Times'' as saying, "I don't think there should be a perception that high-fructose corn syrup has caused obesity until we know more."<ref>{{cite web | first = Melanie | last = Warner | title = A Sweetener With a Bad Rap | publisher = The New York Times | date = ], ] | url = http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/02/business/yourmoney/02syrup.html | accessdate = 2007-11-17}}</ref> In the same article, Walter Willett, chair of the nutrition department of the Harvard School of Public Health, is quoted as saying, "There's no substantial evidence to support the idea that high-fructose corn syrup is somehow responsible for obesity .... If there was no high-fructose corn syrup, I don't think we would see a change in anything important." Willett also recommends drinking water over soft drinks containing sugars or high-fructose corn syrup.<ref> </ref> | |||

| In ] in the United States, HFCS is a honey substitute for some managed ] colonies during times when nectar is in low supply.<ref name="mao">{{cite journal|pmc=3670375|year=2013|last1=Mao|first1=W|title=Honey constituents up-regulate detoxification and immunity genes in the western honey bee Apis mellifera|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=110|issue=22|pages=8842–8846|last2=Schuler|first2=M. A.|last3=Berenbaum|first3=M. R.|doi=10.1073/pnas.1303884110|bibcode=2013PNAS..110.8842M|pmid=23630255|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="wheeler">{{cite journal|pmc=4103092|year=2014|last1=Wheeler|first1=M. M.|title=Diet-dependent gene expression in honey bees: Honey vs. Sucrose or high fructose corn syrup|journal=Scientific Reports|volume=4|pages=5726|last2=Robinson|first2=G. E.|doi=10.1038/srep05726|pmid=25034029|bibcode=2014NatSR...4.5726W}}</ref> However, when HFCS is heated to about {{convert|45|C|F}}, ], which is toxic to bees, can form from the breakdown of fructose.<ref>{{cite journal|pmid=26590927|year=2016|last1=Krainer|first1=S|title=Effect of hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) on mortality of artificially reared honey bee larvae (Apis mellifera carnica)|journal=Ecotoxicology|volume=25|issue=2|pages=320–8|last2=Brodschneider|first2=R|last3=Vollmann|first3=J|last4=Crailsheim|first4=K|last5=Riessberger-Gallé|first5=U|doi=10.1007/s10646-015-1590-x|bibcode=2016Ecotx..25..320K |s2cid=207121566|url=http://resolver.obvsg.at/urn:nbn:at:at-ubg:1-36811}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|pmid=19645504|year=2009|last1=Leblanc|first1=B. W.|title=Formation of hydroxymethylfurfural in domestic high-fructose corn syrup and its toxicity to the honey bee (Apis mellifera)|journal=Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry|volume=57|issue=16|pages=7369–76|last2=Eggleston|first2=G|last3=Sammataro|first3=D|last4=Cornett|first4=C|last5=Dufault|first5=R|last6=Deeby|first6=T|last7=St Cyr|first7=E|doi=10.1021/jf9014526|bibcode=2009JAFC...57.7369L }}</ref> Although some researchers cite honey substitution with HFCS as one factor among many for ], there is no evidence that HFCS is the only cause.<ref name=mao/><ref name=wheeler/><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.epa.gov/pollinator-protection/colony-collapse-disorder|title=Colony collapse disorder|publisher=US Environmental Protection Agency|date=16 September 2016|access-date=3 March 2017}}</ref> Compared to hive honey, both HFCS and sucrose caused signs of malnutrition in bees fed with them, apparent in the ] of genes involved in ] and other processes affecting honey bee health.<ref name=wheeler/> | |||

| === Public relations === | |||

| A study published recently suggests that the consumption of high fructose corn syrups may be linked to leptin resistance in the body. High fructose corn syrups are inexpensive, extremely sweet and extend the shelf life of processed foods, making this a very popular food additive since the early 1980s. Overconsumption of the syrup can lead to weight gain through its suppression of feelings of fullness leading a person to consume more calories than required. <ref></ref><ref></ref> | |||

| {{Main|Public relations of high-fructose corn syrup}} | |||

| There are various public relations concerns with HFCS, including how HFCS products are advertised and labeled as "natural." As a consequence, several companies reverted to manufacturing with sucrose (table sugar) from products that had previously been made with HFCS.<ref name="forbes">{{Cite web|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/kavinsenapathy/2016/04/28/pepsi-coke-want-you-to-think-real-sugar-is-good-for-you/|title=Pepsi, Coke And Other Soda Companies Want You To Think 'Real' Sugar Is Good For You—It's Not|last=Senapathy|first=Kavin|date=28 April 2016|website=Forbes|location=US|language=en|url-status=live|archive-url=https://archive.today/20200323002511/https://www.forbes.com/sites/kavinsenapathy/2016/04/28/pepsi-coke-want-you-to-think-real-sugar-is-good-for-you/%232bb7806664d1|archive-date=23 March 2020}}</ref> In 2010, the Corn Refiners Association applied to allow HFCS to be renamed "corn sugar," but that petition was rejected by the FDA in 2012.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.cbsnews.com/news/fda-rejects-industry-bid-to-change-name-of-high-fructose-corn-syrup-to-corn-sugar/|title=FDA rejects industry bid to change name of high fructose corn syrup to "corn sugar"|work=CBS News|date=31 May 2012}}</ref> | |||

| In August 2016, in a move to please consumers with health concerns, ] announced that it would be replacing all HFCS in their ]s with sucrose (table sugar) and would remove preservatives and other artificial additives from its menu items.<ref name="cnbc">{{Cite web|url=https://www.cnbc.com/2016/08/02/mcdonalds-to-remove-corn-syrup-from-buns-curbs-antibiotics-in-chicken.html|title=McDonald's to remove corn syrup from buns, curbs antibiotics in chicken|date=2 August 2016|website=CNBC|access-date=16 November 2016}}</ref> Marion Gross, senior vice president of McDonald's stated, "We know that they don't feel good about high-fructose corn syrup so we're giving them what they're looking for instead."<ref name=cnbc/> Over the early 21st century, other companies such as ], ], and ] also phased out HFCS, replacing it with conventional sugar because consumers perceived sugar to be healthier.<ref name="zmuda">{{Cite news|url=http://adage.com/article/news/major-brands-longer-sweet-high-fructose-corn-syrup/142788/|title=Major Brands No Longer Sweet on High-Fructose Corn Syrup|author=Zmuda, Natalie|date=15 March 2010|access-date=16 November 2016}}</ref><ref name="guardian">{{cite web|title=Hershey considers removing high-fructose corn syrup from products in favor of sugar|url=https://www.theguardian.com/business/us-money-blog/2014/dec/03/hershey-corn-syrup-sugar-chocolate|publisher=The Guardian, London, UK|access-date=30 January 2018|date=3 December 2014}}</ref> Companies such as ] and Heinz have also released products that use sugar in lieu of HFCS, although they still sell HFCS-sweetened products.<ref name=forbes/><ref name=zmuda/> | |||

| ==Labeling as "natural"== | |||

| {{Cleanup-section|date=September 2008}} | |||

| In May 2006, the ] (CSPI) threatened to file a lawsuit against ] for labeling ] as "All Natural"<ref>{{cite news | url=http://www.douglassreport.com/dailydose/dd200606/dd20060627.html | title=The new, "all-natural" 7Up soft drink | author=William Campbell Douglass II | date=] | accessdate=2007-09-24}}{{Verify credibility|The URL is blacklisted, that's not a good sign I guess|date=November 2008}}</ref> or "100% Natural",<ref>{{cite news | url=http://www.usatoday.com/money/industries/food/2006-04-19-7up-usat_x.htm | title=Food, beverage marketers seek healthier images | publisher=] | first=Theresa | last=Howard | date=] | accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> despite containing high-fructose corn syrup. While the ] has no definition of "natural", CSPI claims that HFCS is not a “natural” ingredient due to the high level of processing and the use of at least one ] (GMO) enzyme required to produce it.<ref>{{cite web | title = CSPI to Sue Cadbury Schweppes over “All Natural” 7UP | publisher = ] | url= http://www.cspinet.org/new/200605111.html | accessdate = 2007-11-17}}</ref> On ], ], ] agreed to stop calling ] "All Natural".<ref>{{cite web | first = Steve | last = Gardner | title = CSPI’s Litigation Project Forces Change By Two Major Food Companies | publisher = ] | date = ], ] | url = http://pubcit.typepad.com/clpblog/2007/01/cspis_litigatio.html | accessdate = 2007-11-17}}</ref> They now label it "100% Natural Flavors".<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.7up.com/7uptext/7up.asp | title=7UP, Now 100% Natural Flavors | publisher=Dr Pepper/Seven Up | year=2007 | accessdate=2007-09-24}}</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| ] (another Cadbury-Schweppes brand) is well-known for being labeled "all-natural", but most varieties contain HFCS. ] Lemonade <ref></ref> and <ref></ref> Limeade are labeled as "all-natural" but also contain HFCS. Bread produced by ] is labeled as having "no artificial preservatives, colors, or flavors", though some varieties contain HFCS.<ref></ref> Still, as the U.S. FDA has no general definition of "natural", a company may refer to its product as "all natural", regardless of the ingredients, in most cases. However, FDA does prohibit beverages that contain less than 100% juice from using phrases like 100% natural and 100% pure. 21 CFR 101.35(l) This might apply to 7UP based on vignettes of lemon, lime, or other fruit which could be construed as purporting to contain juice. | |||

| Commercial production of HFCS began in 1964.<ref name=WhiteChapter2014>{{cite book| | |||

| last=White| first= John S.| chapter=Sucrose, HFCS, and Fructose: History, Manufacture, Composition, Applications, and Production| editor-last=Rippe| editor-first=James M.| title=Fructose, High Fructose Corn Syrup, Sucrose and Health| date= 21 February 2014| publisher=Humana Press| ol = 37192628M| publication-date=2014| isbn=9781489980779}}</ref>{{rp|17}} In the late 1950s, scientists at Clinton Corn Processing Company of ], Iowa, tried to turn glucose from corn starch into fructose, but the process they used was not scalable.<ref name=WhiteChapter2014/>{{rp|17}}<ref>{{cite journal |author=Marshall R. O. |author2=Kooi E. R. | title = Enzymatic Conversion of d-Glucose to d-Fructose | journal = Science | volume = 125 | issue = 3249 | pages = 648–649 | year = 1957 | pmid = 13421660 | doi = 10.1126/science.125.3249.648| bibcode = 1957Sci...125..648M }}</ref> In 1965–1970, Yoshiyuki Takasaki, at the Japanese ] developed a heat-stable xylose isomerase enzyme from yeast. In 1967, the Clinton Corn Processing Company obtained an exclusive license to manufacture glucose ] derived from '']'' bacteria and began shipping an early version of HFCS in February 1967.<ref name=WhiteChapter2014/>{{rp|140}} In 1983, the FDA accepted HFCS as "generally recognized as safe," and that decision was reaffirmed in 1996.<ref name=FDAC>{{cite web|url=https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/?set=SCOGS |title=Database of Select Committee on GRAS Substances (SCOGS) Reviews (updated 29 April 2019)|publisher=US Food and Drug Administration |date=2019 |access-date=17 November 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=High Fructose Corn Syrup: A Guide for Consumers, Policymakers, and the Media|date=2008|publisher=Grocery Manufacturers Association|pages=1–14|url=http://www.gmaonline.org/downloads/research-and-reports/SciPol_HFCS_0602.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101204050842/http://www.gmaonline.org/downloads/research-and-reports/SciPol_HFCS_0602.pdf|url-status=usurped|archive-date=4 December 2010}}</ref> | |||

| Prior to the development of the worldwide sugar industry, dietary fructose was limited to only a few items. Milk, meats, and most vegetables, the staples of many early diets, have no fructose, and only 5–10% fructose by weight is found in fruits such as grapes, apples, and blueberries. Most ]s, however, contain about 50% fructose. From 1970 to 2000, there was a 25% increase in "added sugars" in the U.S.<ref name="Bray2007">{{cite journal |author=Leeper H. A. |author2=Jones E. | title = How bad is fructose? | journal = Am. J. Clin. Nutr. | volume = 86 | issue = 4 | pages = 895–896 | date = October 2007 | pmid = 17921361 | url = http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/86/4/895.full.pdf |doi=10.1093/ajcn/86.4.895 | doi-access = free }}</ref> When recognized as a cheaper, more versatile sweetener, HFCS replaced sucrose as the main sweetener of soft drinks in the United States.<ref name=white-straight/> | |||

| Despite the lawsuit from CSPI, the FDA released this letter to the Corn Refiners Association saying HFCS can be labeled as natural.{{Fact|date=December 2008}} | |||

| Since 1789, the U.S. sugar industry has had trade protection in the form of tariffs on foreign-produced sugar,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://sugarcane.org/sugar-policy-in-united-states/ |title=U.S. Sugar Policy |work=SugarCane.org |access-date=11 February 2015 |archive-date=19 September 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180919114552/http://sugarcane.org/sugar-policy-in-united-states/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> while subsidies to corn growers cheapen the primary ingredient in HFCS, ]. Accordingly, industrial users looking for cheaper sugar replacements rapidly adopted HFCS in the 1970s.<ref>{{cite web|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927203158/http://www.iatp.org/iatp/factsheets.cfm?accountID=258&refID=89968 |archive-date=27 September 2007 |title=Food without Thought: How U.S. Farm Policy Contributes to Obesity |publisher=Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy |date=November 2006|url=http://www.iatp.org/iatp/factsheets.cfm?accountID=258&refID=89968}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.allcountries.org/uscensus/1127_corn_acreage_production_and_value_by.html |title=Corn Production/Value |publisher=Allcountries.org |access-date=6 November 2010}}</ref> | |||

| ==Television ads== | |||

| In September 2008, the Corn Refiners Association<ref></ref> launched a series of United States ]s that claim that HFCS "is made from corn", "doesn't have artificial ]s", "has the same ]s as ] or ]", "is ]ally the same as sugar", and "is fine in ]". The ads feature actors portraying roles in upbeat domestic situations with sugary foods, with one actor disparaging a food's HFCS content but being unable to explain why, and another actor rebuking the comments with these claims. Finally, the ads each advertise the URL with more information provided by the Corn Refiners Association. As HFCS is a ] topic, ] and ]s of the ads have appeared on ]. | |||

| == |

== See also == | ||

| * ] | |||

| Some beverage manufacturers, such as ], ], ], ], ] and ], use sugar rather than high fructose corn syrup in their products. These companies maintain in their advertising that there is a noticeable difference in taste between the two sweeteners. | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | == References == | ||

| {{ |

{{Reflist|30em}} | ||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| *{{Commons category-inline}} | |||

| * {{dmoz|Society/Issues/Health/Food,_Drink_and_Nutrition/Food_Additives/Sugar_Substitutes/High_Fructose_Corn_Syrup}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{corn}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Sugar}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Consumer Food Safety}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:High-Fructose Corn Syrup}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 01:20, 21 December 2024

Processed corn syrup "HFCS" redirects here. Not to be confused with HFCs (hydrofluorocarbons).

High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), also known as glucose–fructose, isoglucose and glucose–fructose syrup, is a sweetener made from corn starch. As in the production of conventional corn syrup, the starch is broken down into glucose by enzymes. To make HFCS, the corn syrup is further processed by D-xylose isomerase to convert some of its glucose into fructose. HFCS was first marketed in the early 1970s by the Clinton Corn Processing Company, together with the Japanese Agency of Industrial Science and Technology, where the enzyme was discovered in 1965.

As a sweetener, HFCS is often compared to granulated sugar, but manufacturing advantages of HFCS over sugar include that it is cheaper. "HFCS 42" and "HFCS 55" refer to dry weight fructose compositions of 42% and 55% respectively, the rest being glucose. HFCS 42 is mainly used for processed foods and breakfast cereals, whereas HFCS 55 is used mostly for production of soft drinks.

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) states that it is not aware of evidence showing that HFCS is less safe than traditional sweeteners such as sucrose and honey. Uses and exports of HFCS from American producers have grown steadily during the early 21st century.

Food

In the United States, HFCS is among the sweeteners that have mostly replaced sucrose (table sugar) in the food industry. Factors contributing to the increased use of HFCS in food manufacturing include production quotas of domestic sugar, import tariffs on foreign sugar, and subsidies of U.S. corn, raising the price of sucrose and reducing that of HFCS, creating a manufacturing-cost advantage among sweetener applications. In spite of having a 10% greater fructose content, the relative sweetness of HFCS 55, used most commonly in soft drinks, is comparable to that of sucrose. HFCS provides advantages in food and beverage manufacturing, such as simplicity of formulation, stability, and enabling processing efficiencies.

HFCS (or standard corn syrup) is the primary ingredient in most brands of commercial "pancake syrup," as a less expensive substitute for maple syrup. Assays to detect adulteration of sweetened products with HFCS, such as liquid honey, use differential scanning calorimetry and other advanced testing methods.

Production

Process

In the contemporary process, corn is milled to extract corn starch and an "acid-enzyme" process is used, in which the corn-starch solution is acidified to begin breaking up the existing carbohydrates. High-temperature enzymes are added to further metabolize the starch and convert the resulting sugars to fructose. The first enzyme added is alpha-amylase, which breaks the long chains down into shorter sugar chains (oligosaccharides). Glucoamylase is mixed in and converts them to glucose. The resulting solution is filtered to remove protein using activated carbon. Then the solution is demineralized using ion-exchange resins. That purified solution is then run over immobilized xylose isomerase, which turns the sugars to ~50–52% glucose with some unconverted oligosaccharides and 42% fructose (HFCS 42), and again demineralized and again purified using activated carbon. Some is processed into HFCS 90 by liquid chromatography, and then mixed with HFCS 42 to form HFCS 55. The enzymes used in the process are made by microbial fermentation.

Composition and varieties

HFCS is 24% water, the rest being mainly fructose and glucose with 0–5% unprocessed glucose oligomers.

The most common forms of HFCS used for food and beverage manufacturing contain fructose in either 42% ("HFCS 42") or 55% ("HFCS 55") by dry weight, as described in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR 184.1866).

- HFCS 42 (approx. 42% fructose if water were ignored) is used in beverages, processed foods, cereals, and baked goods.

- HFCS 55 is mostly used in soft drinks.

- HFCS 70 is used in filling jellies

Commerce and consumption

The global market for HFCS is expected to grow from $5.9 billion in 2019 to a projected $7.6 billion in 2024.

China

HFCS in China makes up about 20% of sweetener demand. HFCS has gained popularity due to rising prices of sucrose, while selling for a third the price. Production was estimated to reach 4,150,000 tonnes in 2017. About half of total produced HFCS is exported to the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and India.

European Union

In the European Union (EU), HFCS is known as isoglucose or glucose–fructose syrup (GFS) which has 20–30% fructose content compared to 42% (HFCS 42) and 55% (HFCS 55) in the United States. While HFCS is produced exclusively with corn in the U.S., manufacturers in the EU use corn and wheat to produce GFS. GFS was once subject to a sugar production quota, which was abolished on 1 October 2017, removing the previous production cap of 720,000 tonnes, and allowing production and export without restriction. Use of GFS in soft drinks is limited in the EU because manufacturers do not have a sufficient supply of GFS containing at least 42% fructose content. As a result, soft drinks are primarily sweetened by sucrose which has a 50% fructose content.

Japan

In Japan, HFCS is also referred to as 異性化糖 (iseika-to; isomerized sugar). HFCS production arose in Japan after government policies created a rise in the price of sugar. Japanese HFCS is manufactured mostly from imported U.S. corn, and the output is regulated by the government. For the period from 2007 to 2012, HFCS had a 27–30% share of the Japanese sweetener market. Japan consumed approximately 800,000 tonnes of HFCS in 2016. The United States Department of Agriculture states that HFCS is produced in Japan from U.S. corn. Japan imports at a level of 3 million tonnes per year, leading 20 percent of corn imports to be for HFCS production.

Mexico

Mexico is the largest importer of U.S. HFCS. HFCS accounts for about 27 percent of total sweetener consumption, with Mexico importing 983,069 tonnes of HFCS in 2018. Mexico's soft drink industry is shifting from sugar to HFCS which is expected to boost U.S. HFCS exports to Mexico according to a U.S. Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service report.

On 1 January 2002, Mexico imposed a 20% beverage tax on soft drinks and syrups not sweetened with cane sugar. The United States challenged the tax, appealing to the World Trade Organization (WTO). On 3 March 2006, the WTO ruled in favor of the U.S. citing the tax as discriminatory against U.S. imports of HFCS without being justified under WTO rules.

Philippines

The Philippines was the largest importer of Chinese HFCS. Imports of HFCS would peak at 373,137 tonnes in 2016. Complaints from domestic sugar producers would result in a crackdown on Chinese exports. On 1 January 2018, the Philippine government imposed a tax of 12 pesos ($.24) on drinks sweetened with HFCS versus 6 pesos ($.12) for drinks sweetened with other sugars.

United States

In the United States, HFCS was widely used in food manufacturing from the 1970s through the early 21st century, primarily as a replacement for sucrose because its sweetness was similar to sucrose, it improved manufacturing quality, was easier to use, and was cheaper. Domestic production of HFCS increased from 2.2 million tons in 1980 to a peak of 9.5 million tons in 1999. Although HFCS use is about the same as sucrose use in the United States, more than 90% of sweeteners used in global manufacturing is sucrose.