| Revision as of 21:42, 14 April 2009 view source68.152.22.130 (talk) →Goal of yoga← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:59, 13 December 2024 view source Chiswick Chap (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers295,760 edits →{{anchor|Yoga as a physical practice}}Yoga as exercise: small ce, punct | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Spiritual practices from ancient India}} | |||

| {{dablink|For other uses, such as ] or ], see ]}} | |||

| {{about||modern yoga as exercise|Yoga as exercise|the use of yoga as therapy|Yoga as therapy|the ancient Indian philosophy|Yoga (philosophy)|other uses}} | |||

| ] performing Yogic meditation in the ] posture.]]{{Hindu philosophy}} | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2016}} | |||

| {{Use Indian English|date=June 2016}} | |||

| ] performing yoga in the ]]] | |||

| {{Contains special characters|Indic}} | |||

| {{Hinduism |schools}} | |||

| '''Yoga'''{{efn|name="traditional_modern_yoga"}} ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|j|oʊ|g|ə}};{{sfn|OED|0000}} {{langx|sa|योग}}, {{IPA|sa|joːɡɐ|audio=Yoga pronunciation.ogg}}, lit. "yoke" or "union") is a group of ], mental, and ] practices or disciplines that originated in ], aimed at controlling body and mind to attain various ] goals,{{sfn|Bowker|2000 |p=entry "Yoga"}}{{sfn|Keown|2004|p=entry "Yoga"}}{{sfn|Johnson|2009|p=entry "Yoga"}}{{efn|name="two_definitions"}} as practiced in the ], ], and ] traditions.{{sfn|Carmody|Carmody|1996|p=68}}{{sfn|Sarbacker|2005|pp=1–2}} | |||

| Yoga may have pre-] origins,{{efn|Hindu-scholars have argued that Yoga has ] Vedic origins, and influenced Jainism and Buddhism.}} but is first attested in the early first millennium BCE. It developed as various traditions in the eastern Ganges basin drew from a common body of practices, including ] elements.{{sfn|Crangle|1994|pp=1–6}}{{sfn|Crangle|1994|pp=103–138}} Yoga-like practices are mentioned in the '']''{{sfn|Werner|1977}} and a number of early ],{{sfn|Deussen|1997|p=556}}{{sfn|Ayyangar|1938|p=2}}{{sfn|Ruff|2011|pp=97–112}}{{efn|name="Katha_Upanishad"}} but systematic yoga concepts emerge during the fifth and sixth centuries BCE in ancient India's ] and ] movements, including Jainism and Buddhism.{{sfn|Samuel|2008|p=8}} The '']'', the classical text on Hindu yoga, ]-based but influenced by Buddhism, dates to the early centuries of the ].{{sfn|Bryant|2009|p=xxxiv}}{{sfn|Desmarais|2008|p=16–17}}{{efn|name="YS_dating"}} ] texts began to emerge between the ninth and 11th centuries, originating in ].{{efn|name="hatha_yoga_dating"}} | |||

| '''Yoga''' (], ]: {{lang|inc|]}} ''{{IAST|yóga}}'') refers to traditional ] and ] disciplines originating in ].<ref>For the uses of the word in ] literature, see Thomas William Rhys Davids, William Stede, ''Pali-English dictionary.'' Reprint by Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1993, page 558: </ref> The word is associated with meditative practices in both ] and ].<ref>Denise Lardner Carmody, John Carmody, ''Serene Compassion.'' Oxford University Press US, 1996, page 68.</ref><ref>Stuart Ray Sarbacker, ''Samadhi: The Numinous and Cessative in Indo-Tibetan Yoga.'' SUNY Press, 2005, pages 1-2.</ref> In Hinduism, it also refers to one of the six orthodox (]) schools of ], and to the goal toward which that school directs its practices.<ref>"Yoga has five principal meanings: 1) yoga as a disciplined method for attaining a goal; 2) yoga as techniques of controlling the body and the mind; 3) yoga as a name of one of the schools or systems of philosophy (''{{IAST|darśana}}''); 4) yoga in connection with other words, such as ''hatha-, mantra-, and laya-'', referring to traditions specialising in particular techniques of yoga; 5) yoga as the goal of yoga practice." Jacobsen, p. 4.</ref><ref>Monier-Williams includes "it is the second of the two Sāṃkhya systems," and "mental abstraction practised as a system (as taught by Patañjali and called the Yoga philosophy)" in his definitions of "yoga".</ref> | |||

| Yoga is practiced worldwide,{{sfn|BBC|2017}} but "yoga" in the Western world often entails a modern form of Hatha yoga and a ],{{sfn|Burley|2000|pp=1–2}} consisting largely of ]s;{{sfn|History|2019}} this differs from traditional yoga, which focuses on ] and release from worldly attachments.{{sfn|King|1999|p=67}}{{sfn|Burley|2000|pp=1–2}}{{sfn|Jantos|2012|pp=362–363}}{{efn|name="traditional_modern_yoga"}} It was introduced by ]s from ] after the success of ]'s adaptation of yoga without asanas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.{{sfn|White|2011|p=xvi–xvii, 2}} Vivekananda introduced the ''Yoga Sutras'' to the West, and they became prominent after the 20th-century success of hatha yoga.{{sfn|White|2014|pp=xvi–xvii}} | |||

| Major branches of yoga include ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name=yogaTrads1_042007>Pandit Usharbudh Arya (1985). The philosophy of hatha yoga. Himalayan Institute Press; 2nd ed.</ref><ref name=yogaTrads2_042007>Sri Swami Rama (2008) The royal path: Practical lessons on yoga. Himalayan Institute Press; New Ed edition.</ref><ref name=yogaTrads_3042007>Swami Prabhavananda (Translator), Christopher Isherwood (Translator), Patanjali (Author). (1996). Vedanta Press; How to know god: The yoga aphorisms of Patanjali. New Ed edition.</ref> Raja Yoga, compiled in the ], and known simply as yoga in the context of Hindu philosophy, is part of the ] tradition.<ref>Jacobsen, p. 4.</ref> Many other ] discuss aspects of yoga, including ], the ], the ], the ] and various ]s. | |||

| {{TOC limit|3}} | |||

| The ] word ''yoga'' has many meanings,<ref>For a list of 38 meanings of the word "yoga" see: Apte, p. 788.</ref> and is derived from the Sanskrit root ''yuj'', meaning "to control", "to yoke" or "to unite".<ref>For "yoga" as derived from the Sanskrit root "yuj" with meanings of "to control", "to yoke, or "to unite" see: Flood (1996), p. 94.</ref> Translations include "joining", "uniting", "union", "conjunction", and "means".<ref>For meaning 1. joining, uniting, and 2., union, junction, combination see: Apte, p. 788.</ref><ref>For "mode, manner, means", see: Apte, p. 788, definition 5.</ref><ref>For "expedient, means in general", see: Apte, p. 788, definition 13.</ref> Outside India, the term ''yoga'' is typically associated with ] and its ] (postures) or as a ]. An accomplished practitioner of Yoga is called a ] (gender neutral) or ] (feminine form). | |||

| == |

==Etymology== | ||

| ], author of the '']'', meditating in the ]]] | |||

| {{Main|History of yoga}} | |||

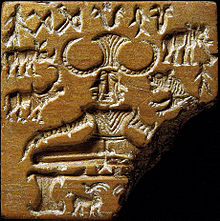

| The Vedic ] contain references to ascetics, while ascetic practices ('']'') are referenced in the ] (900 to 500 BCE), early commentaries on the ].<ref name="Flood, p. 94">Flood, p. 94.</ref> Several seals discovered at Indus Valley Civilization (c. 3300–1700 B.C.E.) sites depict figures in positions resembling a common yoga or meditation pose, showing "a form of ritual discipline, suggesting a precursor of yoga", according to archaeologist ].<ref>Possehl (2003), pp. 144-145</ref> Some type of connection between the Indus Valley seals and later yoga and meditation practices is supported by many scholars.<ref>See: | |||

| * ] describes one figure as "seated in yogic position". | |||

| * Karel Werner writes that "Archeological discoveries allow us therefore to speculate with some justification that a wide range of Yoga activities was already known to the people of pre-Aryan India." {{cite book|last=Werner|first=Karel|title=Yoga and Indian Philosophy|publisher=Motilal Banarsidass Publ.|page=103|date=1998|isbn=9788120816091|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=c6b3lH0-OekC&pg=PA103}}. | |||

| * ] describes one seal as "seated like a yogi". {{cite book|last=Zimmer|first=Heinrich|title=Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization|page=168|publisher=Princeton University Press, New Ed edition|year=1972|ISBN=978-0691017785}} | |||

| * ] writes that "The six mysterious Indus Valley seal images...all without exception show figures in a position known in hatha yoga as ''mulabhandasana'' or possibly the closely related ''utkatasana'' or ''baddha konasana''...." {{cite book|last=McEvilley|first=Thomas|title=The shape of ancient thought|publisher=Allworth Communications|date=2002|pages=219-220|isbn=9781581152036|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Vpqr1vNWQhUC&pg=PA219}} | |||

| * Dr. Farzand Masih, Punjab University Archaeology Department Chairman, describes a recently disovered seal as depicting a "yogi". | |||

| * Gavin Flood disputes the idea regarding one of the seals, the so-called "Pashupati seal", writing that it isn't clear the figure is seated in a yoga posture, or that the shape is intended to represent a human figure. Flood, pp. 28-29.</ref> | |||

| The ] noun {{lang|sa|योग}} ''{{IAST|yoga}}'' is derived from the root ''{{IAST|]}}'' ({{lang|sa|युज्}}) "to attach, join, harness, yoke".{{sfn|Satyananda|2008|p=1}}{{sfn|Jones|Ryan|2007|p=511}} According to Jones and Ryan, "The word yoga is derived from the root yuj, “to yoke,” probably because the early practice concentrated on restraining or “yoking in” the senses. Later the name was also seen as a metaphor for “linking” or “yoking to” God or the divine."{{sfn|Jones|Ryan|2007|p=511}} | |||

| Techniques for experiencing higher states of consciousness in meditation initially had only a slight philosophical underpinning, and were unconnected with ] doctrines.<ref>Charles Eliot, ''Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch.'' Routledge, 1998, page 303.</ref> These techniques were developed by the ] traditions and in the ] tradition.<ref>Flood, pp. 94–95.</ref> An early textual reference to meditation is made in ], one of the earliest Upanishads (approx. 900 BCE).<ref>"...which states that, having become calm and concentrated, one perceives the self (''atman''), within oneself." Flood, pp. 94–95.</ref> The Buddhist texts are probably the earliest texts describing meditation techniques.<ref>], ''Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo.'' Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1988, page 44. Gombrich notes that the early Upanishads do mention meditation, but it is possible that all that is meant by the use of the word is meditation as in meditating upon a topic, i.e. pondering it. For more on the lack of emphasis on meditation in Upanishadic literature prior to Buddhism see Randall Collins, ''The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change.'' Harvard University Press, 2000, pages 199, 205.</ref> In Hindu literature, the term "yoga" first occurs in the ], where it refers to control of the senses and the cessation of mental activity leading to a supreme state.<ref>Flood, p. 95. Scholars do not list the Katha Upanishad among those that can be safely described as pre-Buddhist, see for example Helmuth von Glasenapp, from the 1950 Proceedings of the "Akademie der Wissenschaften und Literatur," . Some have argued that it is post-Buddhist, see for example Arvind Sharma's review of ]'s ''A History of Early Vedanta Philosophy'', Philosophy East and West, Vol. 37, No. 3 (Jul., 1987), pp. 325-331. For a comprehensive examination of the uses of the Pali word "yoga" in early Buddhist texts, see Thomas William Rhys Davids, William Stede, ''Pali-English dictionary.'' Reprint by Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1993, page 558: . For the use of the word in the sense of "spiritual practice" in the ], see Gil Fronsdal, ''The Dhammapada'', Shambhala, 2005, pages 56, 130.</ref> Important textual sources for the evolving concept of Yoga are the middle ], (ca. 400 BCE), the ] including the ] (ca. 200 BCE), and the ] (150 BCE). | |||

| Buswell and Lopez translate "yoga" as "'bond', 'restraint', and by extension "spiritual discipline."{{sfn|Buswell|Lopez|2014|p=entry "yoga"}} Flood refers to restraining the mind as yoking the mind.{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=95}} | |||

| ====Yoga Sutras of Patanjali==== | |||

| ''Yoga'' is a ] of the ] word "yoke," since both are derived from an ] root.{{sfn|White|2011|p=3}} According to ], the first use of the root of the word "yoga" is in hymn 5.81.1 of the '']'', a dedication to the rising Sun-god, where it has been interpreted as "yoke" or "control".{{sfn|Burley|2000|p=25}}<ref name=sriauro />{{efn|Original Sanskrit: '''युञ्जते''' मन उत '''युञ्जते''' धियो विप्रा विप्रस्य बृहतो विपश्चितः। वि होत्रा दधे वयुनाविदेक इन्मही देवस्य सवितुः परिष्टुतिः॥१॥<ref>Sanskrit: <br />Source: {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170511111113/https://sa.wikisource.org/%E0%A4%8B%E0%A4%97%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%B5%E0%A5%87%E0%A4%A6:_%E0%A4%B8%E0%A5%82%E0%A4%95%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%A4%E0%A4%82_%E0%A5%AB.%E0%A5%AE%E0%A5%A7 |date=11 May 2017 }} Wikisource</ref><br />'''Translation 1''': Seers of the vast illumined seer yogically control their minds and their intelligence... (…){{sfn|Burley|2000|p=25}}<br /> | |||

| {{main|Raja Yoga|Yoga Sutras of Patanjali}} | |||

| '''Translation 2''': The illumined yoke their mind and they yoke their thoughts to the illuminating godhead, to the vast, to the luminous in consciousness;<br /> | |||

| In ], Yoga is the name of one of the six ] philosophical schools.<ref>For an overview of the six orthodox schools, with detail on the grouping of schools, see: Radhakrishnan and Moore, "Contents", and pp. 453–487.</ref><ref>For a brief overview of the Yoga school of philosophy see: Chatterjee and Datta, p. 43.</ref> The Yoga philosophical system is closely allied with the ] school.<ref>For close connection between Yoga philosophy and Samkhya, see: Chatterjee and Datta, p. 43.</ref> The Yoga school as expounded by the sage ] accepts the Samkhya psychology and metaphysics, but is more theistic than the Samkhya, as evidenced by the addition of a divine entity to the Samkhya's twenty-five elements of reality.<ref>For Yoga acceptance of Samkhya concepts, but with addition of a category for God, see: Radhakrishnan and Moore, p. 453.</ref><ref>For Yoga as accepting the 25 principles of Samkhya with the addition of God, see: Chatterjee and Datta, p. 43.</ref> The parallels between Yoga and Samkhya were so close that ] says that "the two philosophies were in popular parlance distinguished from each other as Samkhya with and Samkhya without a Lord...."<ref>Müller (1899), Chapter 7, "Yoga Philosophy", p. 104.</ref> The intimate relationship between Samkhya and Yoga is explained by ]: | |||

| the one knower of all manifestation of knowledge, he alone orders the things of the sacrifice. Great is the praise of Savitri, the creating godhead.<ref name=sriauro>Sri Aurobindo (1916, Reprinted 1995), A Hymn to Savitri V.81, in The Secret of Veda, {{ISBN|978-0-914955-19-1}}, page 529</ref>}} | |||

| ] (4th c. BCE) wrote that the term ''yoga'' can be derived from either of two roots: ''yujir yoga'' (to yoke) or ''yuj samādhau'' ("to concentrate").<ref name="Dasgupta 1975 226">{{cite book |last=Dasgupta |first=Surendranath |title=A History of Indian Philosophy | volume=1 |year=1975 |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |location=], India |isbn=81-208-0412-0 |page=226}}</ref> In the context of the ''Yoga Sutras'', the root ''yuj samādhau'' (to concentrate) is considered the correct etymology by traditional commentators.{{sfn|Bryant|2009|p=5}} In accordance with Pāṇini, ] (who wrote the first commentary on the ''Yoga Sutras''){{sfn|Bryant|2009|p=xxxix}} says that yoga means '']'' (concentration).<ref>{{cite book |last=Aranya |first=Swami Hariharananda |author-link=Swami Hariharananda Aranya |title=Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali with Bhasvati |year=2000 |publisher=] |location=Calcutta, India |isbn=81-87594-00-4 |page=1}}</ref> Larson notes that in the Vyāsa Bhāsy the term "samadhi" refers to "all levels of mental life" (sārvabhauma), that is, "all possible states of awareness, whether ordinary or extraordinary."{{sfn|Larson|2008|p=29}} | |||

| <blockquote class="toccolours" style="float:none; padding: 10px 15px 10px 15px; display:table;"> | |||

| These two are regarded in India as twins, the two aspects of a single discipline. {{IAST|Sāṅkhya}} provides a basic theoretical exposition of human nature, enumerating and defining its elements, analyzing their manner of co-operation in a state of bondage ('']''), and describing their state of disentanglement or separation in release ('']''), while Yoga treats specifically of the dynamics of the process for the disentanglement, and outlines practical techniques for the gaining of release, or 'isolation-integration' (''kaivalya'').<ref>Zimmer (1951), p. 280.</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| A person who practices yoga, or follows the yoga philosophy with a high level of commitment, is called a ]; a female yogi may also be known as a ].<ref>American Heritage Dictionary: "Yogi, One who practices yoga." Websters: "Yogi, A follower of the yoga philosophy; an ascetic."</ref> | |||

| Patanjali is widely regarded as the founder of the formal Yoga philosophy.<ref>For ] as the founder of the philosophical system called Yoga see: Chatterjee and Datta, p. 42.</ref> Patanjali's yoga is known as ], which is a system for control of the mind.<ref>For "raja yoga" as a system for control of the mind and connection to Patanjali's Yoga Sutras as a key work, see: Flood (1996), pp. 96–98.</ref> Patanjali defines the word "yoga" in his second sutra,<ref name="yogasutrastext">{{cite web | last = Patañjali| first = | authorlink = Patanjali| coauthors = | title = Yoga Sutras of Patañjali| work = | publisher = Studio 34 Yoga Healing Arts | date = 2001-02-01 | url = http://www.studio34yoga.com/yoga.php#reading| format = ] | doi = | accessdate = 2008-11-24}} </ref> which is the definitional sutra for his entire work: | |||

| {{anchor|Definition in classic Indian texts}} | |||

| <blockquote class="toccolours" style="float:none; padding: 10px 15px 10px 15px; display:table;">''{{IAST|'''योग: चित्त-वृत्ति निरोध:''' <br> ( yogaś citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ ) }}''<br>- Yoga Sutras 1.2</blockquote> | |||

| ==Definition== | |||

| This terse definition hinges on the meaning of three Sanskrit terms. ] translates it as "Yoga is the inhibition (''{{IAST|nirodhaḥ}}'') of the modifications (''{{IAST|vṛtti}}'') of the mind (''{{IAST|citta}}'')".<ref>For text and word-by-word translation as "Yoga is the inhibition of the modifications of the mind" see: Taimni, p. 6.</ref> The use of the word ''{{IAST|nirodhaḥ}}'' in the opening definition of yoga is an example of the important role that Buddhist technical terminology and concepts play in the Yoga Sutra; this role suggests that Patanjali was aware of Buddhist ideas and wove them into his system.<ref>Barbara Stoler Miller, ''Yoga: Discipline of Freedom: the Yoga Sutra Attributed to Patanjali; a Translation of the Text, with Commentary, Introduction, and Glossary of Keywords.'' University of California Press, 1996, page 9.</ref> ] translates the sutra as "Yoga is restraining the mind-stuff (Citta) from taking various forms (Vrittis)."<ref>Vivekanada, p. 115.</ref> | |||

| === Definitions in classical texts === | |||

| ] yogi in the ], ]]] | |||

| The term "''yoga''" has been defined in different ways in Indian philosophical and religious traditions.<!--the whole table sources this statement--> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| Patanjali's writing also became the basis for a system referred to as "Ashtanga Yoga" ("Eight-Limbed Yoga"). This eight-limbed concept derived from the 29<sup>th</sup> Sutra of the 2<sup>nd</sup> book, and is a core characteristic of practically every Raja yoga variation taught today. The Eight Limbs are: | |||

| |+ | |||

| #] (The five "abstentions"): non-violence, non-lying, non-covetousness, non-sensuality, and non-possessiveness. | |||

| !Source Text | |||

| #] (The five "observances"): purity, contentment, austerity, study, and surrender to ]. | |||

| !Approx. Date | |||

| #]: Literally means "seat", and in Patanjali's Sutras refers to the seated position used for meditation. | |||

| !Definition of Yoga{{sfn|Mallinson|Singleton|2017|pp=17–23}} | |||

| #] ("Lengthening Prāna"): ''Prāna'', life force, or vital energy, particularly, the breath, "āyāma", to lengthen or extend. Also interpreted as control of the life force. | |||

| |- | |||

| #] ("Abstraction"): Withdrawal of the sense organs from external objects. | |||

| |'']'' | |||

| #] ("Concentration"): Fixing the attention on a single object. | |||

| | c. 4th century BCE | |||

| #] ("Meditation"): Intense contemplation of the nature of the object of meditation. | |||

| |"Because in this manner he joins the ] (breath), the ], and this Universe in its manifold forms, or because they join themselves (to him), therefore this (process of meditation) is called Yoga (joining). The oneness of breath, mind, and senses, and then the surrendering of all conceptions, that is called Yoga"<ref>{{Cite book |last=Muller |first=F. Max |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TXf-AQAAQBAJ |title=The Upanisads |date=2013-11-05 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-136-86449-0 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| #] ("Liberation"): merging consciousness with the object of meditation. | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| | c. 4th century BCE | |||

| |"Pleasure and suffering arise as a result of the drawing together of the sense organs, the mind and objects. When that does not happen because the mind is in the self, there is no pleasure or suffering for one who is embodied. That is yoga" (5.2.15–16)<ref>], 5.2.15–16</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |'']'' | |||

| | last centuries BCE | |||

| |"When the five senses, along with the mind, remain still and the intellect is not active, that is known as the highest state. They consider yoga to be firm restraint of the senses. Then one becomes un-distracted for yoga is the arising and the passing away" (6.10–11)<ref>'']'', 6.10–11</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |'']'' | |||

| | c. 2nd century BCE | |||

| |"Be equal minded in both success and failure. Such equanimity is called Yoga" (2.48) | |||

| "Yoga is skill in action" (2.50) | |||

| "Know that which is called yoga to be separation from contact with suffering" (6.23)<ref>'']'', 2.48, 2.50, 6.23</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |'']'' | |||

| |c. first centuries CE{{sfn|Bryant|2009|p=xxxiv}}{{sfn|Desmarais|2008|p=16-17}}{{efn|name="YS_dating"}} | |||

| |1.2. ''yogas chitta vritti nirodhah'' – "Yoga is the calming down the fluctuations/patterns of mind"<br />1.3. Then the ] is established in his own essential and fundamental nature.<br />1.4. In other states there is assimilation (of the Seer) with the modifications (of the mind).<ref>'']'', 1.2–4</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |''] (Sravakabhumi)'', a ] Buddhist ] work | |||

| | 4th century CE | |||

| |"Yoga is fourfold: faith, aspiration, perseverance and means" (2.152)<ref>''] (Sravakabhumi)'', 2.152</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |Kaundinya's ''Pancarthabhasya'' on the '']'' | |||

| | 4th century CE | |||

| |"In this system, yoga is the union of the self and the Lord" (I.I.43) | |||

| |- | |||

| |''Yogaśataka'' a ] work by ] | |||

| | 6th century CE | |||

| |"With conviction, the lords of Yogins have in our doctrine defined yoga as the concurrence (''sambandhah'') of the three beginning with correct knowledge, since conjunction with liberation....In common usage this yoga also contact with the causes of these , due to the common usage of the cause for the effect." (2, 4).<ref>''Yogaśataka'', 2, 4</ref>{{sfn|Vasudeva|p=241}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |'']'' | |||

| | {{nowrap|7th–10th century CE}} | |||

| |"By the word 'yoga' is meant nirvana, the condition of ]." (I.8.5a)<ref>'']'', I.8.5a</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |'']-bhasya'' of ] | |||

| | c. 8th century CE | |||

| |"It is said in the treatises on yoga: 'Yoga is the means of perceiving reality' (''atha tattvadarsanabhyupāyo yogah'')" (2.1.3)<ref>']-bhasya'', 2.1.3</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |''Mālinīvijayottara Tantra'', one of the primary authorities in non-dual ] | |||

| | 6th–10th century CE | |||

| |"Yoga is said to be the oneness of one entity with another." (4.4–8)<ref>''Mālinīvijayottara Tantra'', 4.4–8</ref>{{sfn|Vasudeva|pp=235–236}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |''Mrgendratantravrtti'', of the ] scholar Narayanakantha | |||

| | 6th–10th century CE | |||

| |"To have self-mastery is to be a Yogin. The term Yogin means "one who is necessarily "conjoined with" the manifestation of his nature...the Siva-state (''sivatvam'')" (yp 2a)<ref>''Mrgendratantravrtti'', yp 2a</ref>{{sfn|Vasudeva|pp=235–236}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |''Śaradatilaka'' of Lakshmanadesikendra, a ] ] work | |||

| | 11th century CE | |||

| |"Yogic experts state that yoga is the oneness of the individual Self (jiva) with the atman. Others understand it to be the ascertainment of Siva and the Self as non-different. The scholars of the Agamas say that it is a Knowledge which is of the nature of Siva's Power. Other scholars say it is the knowledge of the primordial Self." (25.1–3b)<ref>''Śaradatilaka'', 25.1–3b</ref>{{sfn|Vasudeva|p=243}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |''Yogabija'', a ] work | |||

| | 14th century CE | |||

| |"The union of apana and prana, one's own rajas and semen, the sun and moon, the individual Self and the supreme Self, and in the same way the union of all dualities, is called yoga. " (89)<ref>''Yogabija'', 89</ref> | |||

| |} | |||

| ===Scholarly definitions=== | |||

| In the view of this school, the highest attainment does not reveal the experienced diversity of the world to be ]. The everyday world is real. Furthermore, the highest attainment is the event of one of many individual ] discovering itself; there is no single universal self shared by all persons.<ref>Stephen H. Phillips, ''Classical Indian Metaphysics: Refutations of Realism and the Emergence of "new Logic".'' Open Court Publishing, 1995, pages 12–13.</ref> | |||

| Due to its complicated historical development, and the broad array of definitions and usage in Indian religions, scholars have warned that yoga is hard, if not impossible, to define exactly.{{sfn|White|2011}} David Gordon White notes that "'Yoga' has a wider range of meanings than nearly any other word in the entire Sanskrit lexicon."{{sfn|White|2011}} | |||

| In its broadest sense, yoga is a generic term for techniques aimed at controlling body and mind and attaining a soteriological goal as specified by a specific tradition: | |||

| ====Bhagavad Gita==== | |||

| * Richard King (1999): "Yoga in the more traditional sense of the term has been practised throughout South Asia and beyond and involves a multitude of techniques leading to spiritual and ethical purification. Hindu and Buddhist traditions alike place a great deal of emphasis upon the practice of yoga as a means of attaining liberation from the world of rebirth and yogic practices have been aligned with a variety of philosophical theories and metaphysical positions."{{sfn|King|1999|p=67}} | |||

| {{Main|Bhagavad Gita}} | |||

| * John Bowker (2000): "The means or techniques for transforming consciousness and attaining liberation (mokṣa) from karma and rebirth (saṃsāra) in Indian religions."{{sfn|Bowker|2000 |p=entry "Yoga"}} | |||

| The Bhagavad Gita ('Song of the Lord'), uses the term ''yoga'' extensively in a variety of ways. In addition to an entire chapter (ch. 6) dedicated to traditional yoga practice, including meditation,<ref>Jacobsen, p. 10.</ref> it introduces three prominent types of yoga:<ref>"...Bhagavad Gita, including a complete chapter (ch. 6) devoted to traditional yoga practice. The Gita also introduces the famous three kinds of yoga, 'knowledge' (jnana), 'action' (karma), and 'love' (bhakti)." Flood, p. 96.</ref> | |||

| * Damien Keown (2004): "Any form of spiritual discipline aimed at gaining control over the mind with the ultimate aim of attaining liberation from rebirth."{{sfn|Keown|2004|p=entry "Yoga"}} | |||

| * W. J. Johnson (2009): "A generic term for a wide variety of religious practices At its broadest, however, ‘yoga’ simply refers to a particular method or discipline for transforming the individual A narrower reading makes the practice contingent on, or derived from, control of the body and the senses, as in haṭha-yoga, or control of the breath (prāṇāyāma) and through it the mind, as in Patañjali's rājayoga. At its most neutral, yoga is therefore simply a technique, or set of techniques, including what is usually termed ‘meditation’, for attaining whatever soteriological or soteriological-cum-physiological transformation a particular tradition specifies."{{sfn|Johnson|2009|p=entry "Yoga"}} | |||

| According to ], yoga has five principal meanings:{{sfn|Jacobsen|2018|p=4}} | |||

| *]: The yoga of action, | |||

| # A disciplined method for attaining a goal | |||

| *]: The yoga of devotion, | |||

| # Techniques of controlling the body and mind | |||

| *]: The yoga of knowledge, | |||

| # A name of a school or system of philosophy (''{{IAST|darśana}}'') | |||

| *]: The yoga of wisdom. | |||

| # With prefixes such as "hatha-, mantra-, and laya-, traditions specialising in particular yoga techniques | |||

| # The goal of yoga practice{{sfn|Jacobsen|2011|p=4}} | |||

| ] writes that yoga's core principles were more or less in place in the 5th century CE, and variations of the principles developed over time:{{sfn|White|2011|p=6}} | |||

| ] (b. circa 1490) divided the Gita into three sections, with the first six chapters dealing with Karma yoga, the middle six with Bhakti yoga, and the last six with Jnana (knowledge).<ref> Gambhirananda, p. 16.</ref> Other commentators ascribe a different 'yoga' to each chapter, delineating eighteen different yogas.<ref>Jacobsen, p. 46.</ref> | |||

| # A meditative means of discovering dysfunctional perception and cognition, as well as overcoming it to release any suffering, find inner peace, and salvation. Illustration of this principle is found in Hindu texts such as the '']'' and '']'', in a number of Buddhist Mahāyāna works, as well as Jain texts.{{sfn|White|2011|pp=6–8}} | |||

| # The raising and expansion of consciousness from oneself to being coextensive with everyone and everything. These are discussed in sources such as in Hinduism Vedic literature and its epic '']'', the Jain Praśamaratiprakarana, and Buddhist Nikaya texts.{{sfn|White|2011|pp=8–9}} | |||

| # A path to omniscience and enlightened consciousness enabling one to comprehend the impermanent (illusive, delusive) and permanent (true, transcendent) reality. Examples of this are found in Hinduism ] and ] school texts as well as Buddhism Mādhyamaka texts, but in different ways.{{sfn|White|2011|pp=9–10}} | |||

| # A technique for entering into other bodies, generating multiple bodies, and the attainment of other supernatural accomplishments. These are, states White, described in ] literature of Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as the Buddhist Sāmaññaphalasutta.{{sfn|White|2011|pp=10–12}} | |||

| According to White, the last principle relates to legendary goals of yoga practice; it differs from yoga's practical goals in South Asian thought and practice since the beginning of the Common Era in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain philosophical schools.{{sfn|White|2011|p=11}} ] disagrees with the inclusion of supernatural accomplishments, and suggests that such fringe practices are far removed from the mainstream Yoga's goal as meditation-driven means to liberation in Indian religions.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Mallinson |first=James |author-link=James Mallinson (author) |title=The Yogīs' Latest Trick |journal=Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society |publisher=] |volume=24 |issue=1 |year=2013 |pages=165–180 |doi=10.1017/s1356186313000734 | s2cid=161393103 |doi-access=free |issn = 0035-869X}}</ref> | |||

| ====Hatha Yoga==== | |||

| {{Main|Hatha yoga|Hatha Yoga Pradipika}} | |||

| A classic definition of yoga comes from Patanjali Yoga Sutras 1.2 and 1.3,{{sfn|King|1999|p=67}}{{sfn|White|2011|p=3}}{{sfn|Feuerstein|1998|p=4-5}}{{sfn|Olsson|2023|p=2}} which define yoga as "the stilling of the movements of the mind," and the recognition of Purusha, the witness-consciousness, as different from Prakriti, mind and matter.{{sfn|White|2011|p=3}}{{sfn|Feuerstein|1998|p=4-5}}{{sfn|Olsson|2023|p=2}}{{efn|name="Samuel_White|Vivekananda"|{{harvtxt|Samuel|2010|p=221}}, referring to White (2006), ''"Open" and "Closed" Models of the Human Body in Indian Medical and Yogic Traditions''. Asian Medicine: Tradition and Modernity 2: 1-13, notes that, according to White, a "frequent modern interpretation of yoga" is largely based on "Vivekananda's selective reading of the ''Yogasutra'', as 'a meditative practice through which the absolute was to be found by turning the mind and senses inwards, away from the world'."}} According to Larson, in the context of the ''Yoga Sutras'', yoga has two meanings. The first meaning is yoga "as a general term to be translated as "disciplined meditation" that focuses on any of the many levels of ordinary awareness."{{sfn|Larson|2008|p=30}} In the second meaning yoga is "that specific system of thought (sāstra) that has for its focus the analysis, understanding and cultivation of those altered states of awareness that lead one to the experience of spiritual liberation."{{sfn|Larson|2008|p=30}} | |||

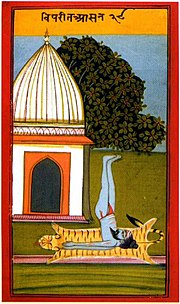

| Hatha Yoga is a particular system of Yoga described by ], compiler of the ] in 15th century India. Hatha Yoga differs substantially from the ] of Patanjali in that it focuses on '']'', the purification of the physical body as leading to the purification of the mind (''ha''), and '']'', or vital energy (''tha'').<ref>Living Yoga: Creating a Life Practice - Page 42 by Christy Turlington (page 42)</ref><ref>Guiding Yoga's Light: Yoga Lessons for Yoga Teachers - Page 10 by Nancy Gerstein </ref> Compared to the seated asana, or sitting meditation posture, of Patanjali's Raja yoga,<ref>Mindfulness Yoga: The Awakened Union of Breath Body & Mind - Page 6 by Frank Jude Boccio</ref> it marks the development of ''asanas'' (plural) into the full body 'postures' now in popular usage.<ref name=Burley>Hatha Yoga: Its Context, Theory and Practice By Mikel Burley (page 16)</ref> Hatha Yoga in its many modern variations is the style that many people associate with the word "Yoga" today.<ref>Feuerstein, Georg. (1996). ''The Shambhala Guide to Yoga''. Boston & London: Shambhala Publications, Inc.</ref> | |||

| Another classic understanding{{sfn|King|1999|p=67}}{{sfn|White|2011|p=3}}{{sfn|Feuerstein|1998|p=4-5}}{{sfn|Olsson|2023|p=2}} sees yoga as union or connection with the highest Self (''paramatman''), Brahman,{{sfn|Feuerstein|1998|p=4-5}} or God, a "union, a linking of the individual to the divine."{{sfn|Olsson|2023|p=2}} This definition is based on the devotionalism (]) of the Bhagavad Gita, and the ] of ].{{sfn|Olsson|2023|p=2}}{{sfn|Feuerstein|1998|p=4-5}}{{efn|name="Grimes"|See, for example, {{harvtxt|Grimes|1996|p=359}}, who states that yoga is a process (or discipline) leading to unity ('']'') with the divine ('']'') or with one's self ('']'').}}{{efn|name="union_AV"|This understanding of yoga as union with the divine is also informed by the medieaval synthesis of Advaita Vedanta and yoga, with the Advaita Vedanta-tradition explicitly incorporating elements from the yogic tradition and texts like the '']'' and the '']'',{{sfn|Madaio|2017|pp=4–5}} culminating in ]'s full embrace and propagation of Yogic samadhi as an Advaita means of knowledge of the identity of the individual self (''jivataman'') and the highest self (''Brahman''), leading to liberation.{{sfn|Rambachan|1994}}{{sfn|Nicholson|2010}}}} | |||

| ==Yoga practices in other traditions== | |||

| ===Buddhism=== | |||

| {{main | Yoga and Buddhism}} | |||

| Early ] incorporated ].<ref name=Heisig>Zen Buddhism: A History (India and China) By ], James W. Heisig, Paul F. Knitter (page 22)</ref> The most ancient sustained expression of yogic ideas is found in the early sermons of the Buddha.<ref>Barbara Stoler Miller, ''Yoga: Discipline of Freedom: the Yoga Sutra Attributed to Patanjali; a Translation of the Text, with Commentary, Introduction, and Glossary of Keywords.'' University of California Press, 1996, page 8.</ref> | |||

| While yoga is often conflated with the "classical yoga" of Patanjali's yoga sutras, Karen O'Brien-Kop notes that "classical yoga" is informed by, and includes, Buddhist yoga.{{sfn|O'Brien-Kop|2021|p=1}} Regarding Buddhist yoga, James Buswell in his ''Encyclopedia of Buddhism'' treats yoga in his entry on meditation, stating that the aim of meditation is to attain samadhi, which serves as the foundation for ''vipasyana'', "discerning the real from the unreal," liberating insight into true reality.{{sfn|Buswell|2004|p=520}} Buswell & Lopez state that "in Buddhism, a generic term for soteriological training or contemplative practice, including tantric practice."{{sfn|Buswell|Lopez|2014|p=entry "yoga"}} | |||

| ====Yogacara Buddhism==== | |||

| ] (Sanskrit: "yoga practice"<ref></ref>), also spelled yogāchāra, is a school of philosophy and psychology that developed in ] during the 4th to 5th centuries. Yogacara received the name as it provided a ''yoga'', a framework for engaging in the practices that lead to the path of the ].<ref>Dan Lusthaus. Buddhist Phenomenology: A Philosophical Investigation of Yogacara Buddhism and the Ch'eng Wei-shih Lun. Published 2002 (Routledge). ISBN 0700711864. pg 533</ref> The Yogacara sect teaches ''yoga'' in order to reach enlightenment.<ref name=Simpkins>Simple Tibetan Buddhism: A Guide to Tantric Living By C. Alexander Simpkins, Annellen M. Simpkins. Published 2001. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0804831998</ref> | |||

| O'Brien-Kop further notes that "classical yoga" is not an independent category, but "was informed by the European colonialist project."{{sfn|O'Brien-Kop|2021|p=1}} | |||

| ====Ch'an (Seon/Zen) Buddhism==== | |||

| ] (the name of which derives from the Sanskrit "dhyaana" via the Chinese "ch'an"<ref> The Buddhist Tradition in India, China, and Japan. Edited by William Theodore de Bary. Pgs. 207-208. ISBN 0-394-71696-5 - "The Meditation school, called ''Ch'an'' in Chinese from the Sanskrit ''dhyāna'', is best known in the West by the Japanese pronunciation ''Zen''"</ref>) is a form of ]. The Mahayana school of Buddhism is noted for its proximity with Yoga.<ref name=Heisig/> In the west, Zen is often set alongside Yoga; the two schools of meditation display obvious family resemblances.<ref> Zen Buddhism: A History (India and China) By ], James W. Heisig, Paul F. Knitter (Page xviii) </ref> This phenomenon merits special attention since the Zen Buddhist school of meditation has some of its roots in yogic practices.<ref>Zen Buddhism: A History (India and China) By ], James W. Heisig, Paul F. Knitter (page 13). | |||

| Translated by James W. Heisig, Paul F. Knitter. Contributor John McRae. Published 2005 ]. 387 pages. ISBN 0941532895 </ref> Certain essential elements of Yoga are important both for Buddhism in general and for Zen in particular.<ref name=Knitter>Zen Buddhism: A History (India and China) By ], James W. Heisig, Paul F. Knitter (page 13)</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ====Tibetan Buddhism==== | |||

| ], showing a seated figure in ], surrounded by animals,3300 BCE, ] ]] | |||

| Yoga is central to ]. In the ] tradition, practitioners progress to increasingly profound levels of yoga, starting with ], continuing to ] and ultimately undertaking the highest practice, ]. In the ] traditions, the ] class is equivalent. Other tantra yoga practices include a system of 108 bodily postures practiced with breath and heart rhythm. Timing in movement exercises is known as ] or union of moon and sun (channel) prajna energies. The body postures of Tibetan ancient yogis are depicted on the walls of the Dalai Lama's summer temple of ]. A semi-popular account of Tibetan Yoga by Chang (1993) refers to ], the generation of heat in one's own body, as being "the very foundation of the whole of Tibetan Yoga".<ref>Chang, G.C.C. (1993). ''Tibetan Yoga''. New Jersey: Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8065-1453-1, p.7</ref> Chang also claims that Tibetan Yoga involves reconciliation of apparent polarities, such as ] and mind, relating this to theoretical implications of ]. | |||

| There is no consensus on yoga's chronology or origins other than its development in ancient India. There are two broad theories explaining the origins of yoga. The linear model holds that yoga has Vedic origins (as reflected in Vedic texts), and influenced Buddhism. This model is mainly supported by Hindu scholars.{{sfn|Crangle|1994|p=1-6}} According to the synthesis model, yoga is a synthesis of indigenous, non-Vedic practices with Vedic elements. This model is favoured in Western scholarship.{{sfn|Crangle|1994|p=103-138}} | |||

| The earliest yoga-practices may have appeared in the Jain tradition at ca. 900 BCE.{{sfn|Jones|Ryan|2007|p=511}}Speculations about yoga are documented in the early Upanishads of the first half of the first millennium BCE, with expositions also appearing in Jain and Buddhist texts {{circa|500|200 BCE}}. Between 200 BCE and 500 CE, traditions of Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain philosophy were taking shape; teachings were collected as ]s, and a philosophical system of ''Patanjaliyogasastra'' began to emerge.{{sfn|Larson|2008|p=36}} The Middle Ages saw the development of a number of yoga satellite traditions. It and other aspects of Indian philosophy came to the attention of the educated Western public during the mid-19th century. | |||

| ===Islam=== | |||

| ===Origins=== | |||

| The development of ]sm was considerably influenced by Indian yogic practises, where they adapted both physical postures (]) and breath control (]).<ref></ref> The ancient Indian yogic text, Amritakunda, ("Pool of Nectar)" was translated into Arabic and Persian as early as the 11th century.<ref> </ref> | |||

| ===={{anchor|Synthetic model}}Synthesis model==== | |||

| Malaysia's top ]ic body in 2008 passed a ], which is legally non-binding, against ]s practicing yoga, saying it had elements of "] spiritual teachings" and could lead to ] and is therefore ]. Muslim yoga teachers in Malaysia criticized the decision as "insulting".<ref> - ]</ref> ], a women's rights group in Malaysia, also expressed disappointment and said they would continue with their yoga classes.<ref></ref> The fatwa states that yoga practiced only as physical exercise is permissible, but prohibits the chanting of religious mantras,<ref>"," Associated Press</ref> and states that teachings such as uniting of a human with God is not consistent with Islamic philosophy.<ref> </ref> | |||

| Heinrich Zimmer was an exponent of the synthesis model,{{sfn|Crangle|1994|p=5}} arguing for non-Vedic ].{{sfn|Zimmer|1951|p=217, 314}} According to Zimmer, yoga is part of a non-Vedic system which includes the ] school of ], ] and ]:{{sfn|Zimmer|1951|p=217, 314}} " does not derive from Brahman-Aryan sources, but reflects the cosmology and anthropology of a much older pre-Aryan upper class of northeastern India – being rooted in the same subsoil of archaic metaphysical speculation as Yoga, ], and Buddhism, the other non-Vedic Indian systems."{{sfn|Zimmer|1951|p=217}}{{refn|group=note|Zimmer's point of view is supported by other scholars, such as Niniam Smart in ''Doctrine and argument in Indian Philosophy'', 1964, pp. 27–32, 76{{sfn|Crangle|1994|p=7}} and S. K. Belvakar and ] in ''History of Indian philosophy'', 1974 (1927), pp. 81, 303–409.{{sfn|Crangle|1994|pp=5–7}}}} More recently, ]{{sfn|Gombrich|2007}} and Geoffrey Samuel{{sfn|Samuel|2008}} also argue that the '']'' movement originated in the non-Vedic eastern Ganges basin,{{sfn|Samuel|2008}} specifically ].{{sfn|Gombrich|2007}} | |||

| In a similar vein, the ], an Islamic body in Indonesia, passed a ] banning yoga on the grounds that it contains "Hindu elements"<ref></ref> These fatwas have, in turn, been criticized by ], a ] Islamic seminary in India.<ref></ref> | |||

| Thomas McEvilley favors a composite model in which a pre-Aryan yoga prototype existed in the pre-Vedic period and was refined during the Vedic period.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=McEvilley|first=Thomas|year=1981|title=An Archaeology of Yoga|journal=Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics |volume=1 |issue=spring |page=51 |doi=10.1086/RESv1n1ms20166655 |s2cid=192221643|issn=0277-1322}}</ref> According to Gavin D. Flood, the Upanishads differ fundamentally from the Vedic ritual tradition and indicate non-Vedic influences.{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=78}} However, the traditions may be connected: | |||

| ===Christianity=== | |||

| {{blockquote|his dichotomization is too simplistic, for continuities can undoubtedly be found between renunciation and vedic Brahmanism, while elements from non-Brahmanical, Sramana traditions also played an important part in the formation of the renunciate ideal.{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=77}}{{refn|group=note|Gavin Flood: "These renouncer traditions offered a new vision of the human condition which became incorporated, to some degree, into the worldview of the Brahman householder. The ideology of asceticism and renunciation seems, at first, discontinuous with the brahmanical ideology of the affirmation of social obligations and the performance of public and domestic rituals. Indeed, there has been some debate as to whether asceticism and its ideas of retributive action, reincarnation and spiritual liberation, might not have originated outside the orthodox vedic sphere, or even outside Aryan culture: that a divergent historical origin might account for the apparent contradiction within 'Hinduism' between the world affirmation of the householder and the world negation of the renouncer. However, this dichotomization is too simplistic, for continuities can undoubtedly be found between renunciation and vedic Brahmanism, while elements from non-Brahmanical, Sramana traditions also played an important part in the formation of the renunciate ideal. Indeed there are continuities between vedic Brahmanism and Buddhism, and it has been argued that the Buddha sought to return to the ideals of a vedic society which he saw as being eroded in his own day."{{sfn|Flood|1996|pp=76–77}}}}}} | |||

| In 1989, the ] declared that Eastern meditation practices such as Zen and yoga can "degenerate into a cult of the body." In spite of the Vatican statement, many ]s bring elements of Yoga, Buddhism, and Hinduism into their spiritual practices.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0CE1D61531F934A35752C0A966958260&sec=&spon=|title=Trying to Reconcile the Ways of the Vatican and the East |last=Steinfels|first=Peter|date=1990-01-07|work=New York Times|accessdate=2008-12-05}}</ref> | |||

| ........... | |||

| OSB, who is a Benedictine monk, is an expert in Zen Buddhism and was given the mandate to teach Eastern meditation techniques to monks and nuns in convents and monasteries, in the 1970's. | |||

| The ascetic traditions of the eastern Ganges plain are thought to drew from a common body of practices and philosophies,{{sfn|Bryant|2009|p=xxi}}{{sfn|Samuel|2008}}{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=233}} with proto-samkhya concepts of ''purusha'' and ''prakriti'' as a common denominator.{{sfn|Larson|2014}}{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=233}} | |||

| Pope John Paul II gave his blessings to for his ecumenism work through Integral Yoga. | |||

| ====Linear model==== | |||

| Many Catholic churches and colleges have served as venues for over forty years for Integral Yoga events and retreats, such as Salve Regina College in Rhode Island, where Marcela Andre ]staffed as a disciple of Swami Satchidananda in the 1970's. | |||

| According to Edward Fitzpatrick Crangle, Hindu researchers have favoured a linear theory which attempts "to interpret the origin and early development of Indian contemplative practices as a sequential growth from an Aryan genesis";{{sfn|Crangle|1994|p=4}}{{refn|group=note|See also Gavin Flood (1996), ''Hinduism'', p.87–90, on "The orthogenetic theory" and "Non-Vedic origins of renunciation".{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=87–90}}}} traditional Hinduism regards the ] as the source of all spiritual knowledge.{{sfn|Crangle|1994|p=5}}{{refn|group=note|Post-classical traditions consider ] the originator of yoga.{{sfn|Feuerstein|2001|loc=Kindle Locations 7299–7300}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Aranya |first=Swami Hariharananda |author-link=Swami Hariharananda Aranya |title=Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali with Bhasvati |year=2000 |publisher=University of Calcutta |location=Calcutta, India |isbn=81-87594-00-4|page=xxiv | chapter=Introduction}}</ref>}} Edwin Bryant wrote that authors who support ] also tend to support the linear model.{{sfn|Bryant2009|p=xix-xx}} | |||

| ====Indus Valley Civilisation==== | |||

| Notably, in New York City, the hemisphere's largest cathedral, St. John the Divine in the upper West side of New York has been the participating host to the Yoga Ecumenical Service of Swami Satchidananda, and hosted his 12-year anniversary of arriving in the USA in 1978. This is a truly Anglican service in communion with people of all faiths and is a diverse congregation. | |||

| The twentieth-century scholars ], ], and Mircea Eliade believe that the central figure of the ] is in a ] posture,{{sfn|Singleton|2010|pp=25–34}} and the roots of yoga are in the ].{{sfn|Samuel|2008|pp=1–14}} This is rejected by more recent scholarship; for example, ], Andrea R. Jain, and ] describe the identification as speculative; the meaning of the figure will remain unknown until ] is deciphered, and the roots of yoga cannot be linked to the IVC.{{sfn|Samuel|2008|pp=1–14}}<ref name=":5">{{Cite journal|last=Doniger|first=Wendy|date=2011|title=God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shiva|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/23347187|journal=Social Research|volume=78|issue=2|pages=485–508|jstor=23347187|issn=0037-783X}}</ref>{{refn|group=note|Some scholars are now considering the image to be an instance of Lord of the Beasts found in Eurasian neolithic mythology or the widespread motif of the ] found in ancient ]ern and Mediterranean art.{{sfn|Witzel|2008|pp=68–70, 90}}<ref>{{Cite book|last=Kenoyer|first=Jonathan Mark|title=The Master of Animals in Old World Iconography|publisher=Archaeolingua Alapítvány|year=2010|editor-last=Counts|editor-first=Derek B.|pages=50|chapter=Master of Animals and Animal Masters in the Iconography of the Indus Tradition|editor-last2=Arnold|editor-first2=Bettina}}</ref>}} | |||

| ==={{anchor|Earliest textual references (1000–500 BCE)}}Earliest references (1000–500 BCE)=== | |||

| ===Tantra=== | |||

| {{Further|Vedic period}} | |||

| The ], the only texts preserved from the early Vedic period and codified between c. 1200 and 900 BCE, contain references to yogic practices primarily related to ascetics outside, or on the fringes of ].{{sfn|Jacobsen|2018|p=6}}{{sfn|Werner|1977}} The earliest yoga-practices may have come from the Jain tradition at ca. 900 BCE.{{sfn|Jones|Ryan|2007|p=511}} | |||

| The ''Rigveda''{{'s}} ] suggests an early Brahmanic contemplative tradition.{{refn|group=note| | |||

| * Wynne states that "The Nasadiyasukta, one of the earliest and most important cosmogonic tracts in the early Brahminic literature, contains evidence suggesting it was closely related to a tradition of early Brahminic contemplation. A close reading of this text suggests that it was closely related to a tradition of early Brahminic contemplation. The poem may have been composed by contemplatives, but even if not, an argument can be made that it marks the beginning of the contemplative/meditative trend in Indian thought."{{sfn|Wynne|2007|p=50}} | |||

| * Miller suggests that the composition of Nasadiya Sukta and '']'' arises from "the subtlest meditative stage, called absorption in mind and heart" which "involves enheightened experiences" through which seer "explores the mysterious psychic and cosmic forces...".{{sfn|Whicher|1998|p=11}} | |||

| * Jacobsen writes that dhyana (meditation) is derived from the Vedic term dhih which refers to "visionary insight", "thought provoking vision".{{sfn|Whicher|1998|p=11}}}} Techniques for controlling breath and vital energies are mentioned in the ''Atharvaveda'' and in the ]s (the second layer of the Vedas, composed c. 1000–800 BCE).{{sfn|Jacobsen|2018|p=6}}{{sfn|Lamb|2011|p=427}}{{sfn|Whicher|1998|p=13}} | |||

| According to Flood, "The ]s contain some references ... to ascetics, namely the ] or ]s and the Vratyas."{{sfn|Flood|1996|pp=94–95}} Werner wrote in 1977 that the ''Rigveda'' does not describe yoga, and there is little evidence of practices.{{sfn|Werner|1977}} The earliest description of "an outsider who does not belong to the Brahminic establishment" is found in the ] hymn 10.136, the ''Rigveda''{{'s}} youngest book, which was codified around 1000 BCE.{{sfn|Werner|1977}} Werner wrote that there were | |||

| {{Blockquote|... individuals who were active outside the trend of Vedic mythological creativity and the Brahminic religious orthodoxy and therefore little evidence of their existence, practices and achievements has survived. And such evidence as is available in the Vedas themselves is scanty and indirect. Nevertheless the indirect evidence is strong enough not to allow any doubt about the existence | |||

| of spiritually highly advanced wanderers.{{sfn|Werner|1977}}}} | |||

| According to Whicher (1998), scholarship frequently fails to see the connection between the contemplative practices of the '']s'' and later yoga practices: "The proto-Yoga of the Vedic ]s is an early form of sacrificial mysticism and contains many elements characteristic of later Yoga that include: concentration, meditative observation, ascetic forms of practice (''tapas''), breath control practiced in conjunction with the recitation of sacred hymns during the ritual, the notion of self-sacrifice, impeccably accurate recitation of sacred words (prefiguring ''mantra-yoga''), mystical experience, and the engagement with a reality far greater than our psychological identity or the ego."{{sfn|Whicher|1998|p=12}} Jacobsen wrote in 2018, "Bodily postures are closely related to the tradition of ('']''), ascetic practices in the Vedic tradition"; ascetic practices used by Vedic priests "in their preparations for the performance of the ]" may be precursors of yoga.{{sfn|Jacobsen|2018|p=6}} "The ecstatic practice of enigmatic longhaired ''muni'' in ''Rgveda'' 10.136 and the ascetic performance of the ''vratya-s'' in the ''Atharvaveda'' outside of or on the fringe of the Brahmanical ritual order, have probably contributed more to the ascetic practices of yoga."{{sfn|Jacobsen|2018|p=6}} | |||

| According to Bryant, practices recognizable as classical yoga first appear in the Upanishads (composed during the late ]).{{sfn|Bryant|2009|p=xxi}} Alexander Wynne agrees that formless, elemental meditation might have originated in the Upanishadic tradition.{{sfn|Wynne|2007|pp=44–45, 58}} An early reference to meditation is made in the ] (c. 900 BCE), one of the ].{{sfn|Flood|1996|pp=94–95}} The ] (c. 800–700 BCE) describes the five vital energies ('']''), and concepts of later yoga traditions (such as ] and an internal sound) are also described in this upanishad.{{sfn|Jacobsen|2011|p=6}} The practice of ] (focusing on the breath) is mentioned in hymn 1.5.23 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad,<ref name=Eliade2009/> and ] (withdrawal of the senses) is mentioned in hymn 8.15 of Chandogya Upanishad.<ref name=Eliade2009>Mircea Eliade (2009), Yoga: Immortality and Freedom, Princeton University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-691-14203-6}}, pages 117–118</ref>{{refn|group=note|Original Sanskrit: स्वाध्यायमधीयानो धर्मिकान्विदध'''दात्मनि सर्वैन्द्रियाणि संप्रतिष्ठा'''प्याहिँसन्सर्व भूतान्यन्यत्र तीर्थेभ्यः स खल्वेवं वर्तयन्यावदायुषं ब्रह्मलोकमभिसंपद्यते न च पुनरावर्तते न च पुनरावर्तते॥ १॥ – ], VIII.15<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160822070520/https://sa.wikisource.org/%E0%A4%9B%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%A8%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%A6%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%97%E0%A5%8D%E0%A4%AF%E0%A5%8B%E0%A4%AA%E0%A4%A8%E0%A4%BF%E0%A4%B7%E0%A4%A6%E0%A5%8D_%E0%A5%AA |date=22 August 2016 }}, Chandogya Upanishad, अष्टमोऽध्यायः॥ पञ्चदशः खण्डः॥</ref><br /> | |||

| Translation 1 by ], The Upanishads, The ] – Part 1, Oxford University Press: (He who engages in) self study, concentrates all his senses on the Self, never giving pain to any creature, except at the tîrthas, he who behaves thus all his life, reaches the world of ], and does not return, yea, he does not return.<br /> | |||

| Translation 2 by G.N. Jha: VIII.15, page 488: (He who engages in self study),—and having withdrawn all his sense-organs into the Self,—never causing pain to any living beings, except in places specially ordained,—one who behaves thus throughout life reaches the ''Region of Brahman'' and does not return,—yea, does not return.—}} The ] (probably before the 6th c. BCE) teaches breath control and repetition of a ].{{sfn|Mallinson|Singleton|2017|p=xii}} The 6th-c. BCE ] defines yoga as the mastery of body and senses.{{sfn|Whicher|1998|p=17}} According to Flood, "he actual term ''yoga'' first appears in the ],{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=95}} dated to the fifth<ref>Richard King (1995). ''''. SUNY Press. {{ISBN|978-0-7914-2513-8}}, page 52</ref> to first centuries BCE.{{sfn|Olivelle|1996|p=xxxvii}} | |||

| ===Second urbanisation (500–200 BCE)=== | |||

| {{Main|History of India#"Second urbanisation" (c. 600 – c. 200 BCE)|l1=Second urbanisation}} | |||

| Systematic yoga concepts begin to emerge in texts dating to c. 500–200 BCE, such as the ], the middle Upanishads, and the '']''{{'s}} '']'' and '']''.{{sfn|Larson|2008|pp=34–35, 53}}{{refn|group=note|Ancient Indian literature was transmitted and preserved through an ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Wynne |first1=Alexander |title=The Oral Transmission of the Early Buddhist Literature |journal=Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies |date=2004 |volume=27 |issue=1 |pages=97–128 |url=http://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/jiabs/article/view/8945/2838}}</ref> For example, the earliest written Pali Canon text is dated to the later part of the 1st century BCE, many centuries after the Buddha's death.<ref>Donald Lopez (2004). Buddhist Scriptures. Penguin Books. pp. xi–xv. {{ISBN|978-0-14-190937-0}}</ref>}} | |||

| ===={{anchor|Buddhism and śramaṇa movement}}Buddhism and the śramaṇa movement==== | |||

| ] of the Buddha becoming a wandering hermit instead of a warrior |alt=Old stone carving of the Buddha with his servants and horse]] | |||

| <!-- Irrelevant to article subject ] is said to have attained omniscience|left]] --> | |||

| <!--This quotation is repeated, see above-->According to ], the "best evidence to date" suggests that yogic practices "developed in the same ascetic circles as the early ] movements (], ] and ]), probably in around the sixth and fifth centuries BCE." This occurred during India's ] period.{{sfn|Samuel|2008|p=8}} According to Mallinson and Singleton, these traditions were the first to use mind-body techniques (known as ''Dhyāna'' and ''tapas'') but later described as yoga, to strive for liberation from the round of rebirth.{{sfn|Mallinson|Singleton|2017|pp=13–15}} | |||

| Werner writes, "The Buddha was the founder of his system, even though, admittedly, he made use of some of the experiences he had previously gained under various Yoga teachers of his time."{{sfn|Werner|1998|p=131}} He notes:{{sfn|Werner|1998|pp=119–20}} | |||

| {{blockquote|But it is only with Buddhism itself as expounded in the ] that we can speak about a systematic and comprehensive or even integral school of Yoga practice, which is thus the first and oldest to have been preserved for us in its entirety.{{sfn|Werner|1998|pp=119–20}}}} | |||

| Early Buddhist texts describe yogic and meditative practices, some of which the Buddha borrowed from the ] tradition.<ref>], "Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo." Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1988, p. 44.</ref><ref>Barbara Stoler Miller, "Yoga: Discipline of Freedom: the Yoga Sutra Attributed to Patanjali; a Translation of the Text, with Commentary, Introduction, and Glossary of Keywords." University of California Press, 1996, p. 8.</ref> The ] contains three passages in which the Buddha describes pressing the tongue against the palate to control hunger or the mind, depending on the passage.<ref>Mallinson, James. 2007. ''The Khecarīvidyā of Adinathā.'' London: Routledge. pp. 17–19.</ref> There is no mention of the tongue inserted into the ], as in ]. The Buddha used a posture in which pressure is put on the ] with the heel, similar to modern postures used to evoke ].<ref>{{harvnb|Mallinson |2012|pp=20–21}}, "The Buddha himself is said to have tried both pressing his tongue to the back of his mouth, in a manner similar to that of the hathayogic khecarīmudrā, and ukkutikappadhāna, a ] which may be related to hathayogic techniques such as mahāmudrā, mahābandha, mahāvedha, mūlabandha, and vajrāsana in which pressure is put on the perineum with the heel, in order to force upwards the breath or Kundalinī."</ref> ] which discuss yogic practice include the '']'' (the ] sutta) and the '']'' (the ] sutta). | |||

| The chronology of these yoga-related early Buddhist texts, like the ancient Hindu texts, is unclear.{{sfn|Samuel|2008|pp=31–32}}{{sfn|Singleton|2010|loc=Chapter 1}} Early Buddhist sources such as the ] mention meditation; the ] describes ''jhāyins'' (meditators) who resemble early Hindu descriptions of ''muni'', the Kesin and meditating ascetics,<ref>] (1993), The Two Traditions of Meditation in Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, {{ISBN|978-8120816435}}, pages 1–24</ref> but the meditation practices are not called "yoga" in these texts.{{sfn|White|2011|pp=5–6}} The earliest known discussions of yoga in Buddhist literature, as understood in a modern context, are from the later Buddhist ] and ] schools.{{sfn|White|2011|pp=5–6}} | |||

| ] is a yoga system which predated the Buddhist school. Since Jain sources are later than Buddhist ones, however, it is difficult to distinguish between the early Jain school and elements derived from other schools.{{sfn|Werner|1998|pp=119–120}} Most of the other contemporary yoga systems alluded to in the Upanishads and some Buddhist texts have been lost.<ref name="Eating disorders">{{cite journal |last=Douglass |first=Laura |year=2011 |title=Thinking Through The Body: The Conceptualization Of Yoga As Therapy For Individuals With Eating Disorders |url=http://web.ebscohost.com.subzero.lib.uoguelph.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&sid=1d8495be-1c1c-4423-ad48-1f6054f42876%40sessionmgr111&hid=103 |journal=Academic Search Premier|page=83 |access-date=19 February 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zB4n3MVozbUC&pg=PA1809|title=Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: devraj to jyoti|last=Datta|first=Amaresh|publisher=Sahitya Akademi|year=1988|isbn=978-81-260-1194-0|page=1809}}</ref>{{refn|On the dates of the Pali canon, Gregory Schopen writes, "We know, and have known for some time, that the Pali canon as we have it — and it is generally conceded to be our oldest source — cannot be taken back further than the last quarter of the first century BCE, the date of the Alu-vihara redaction, the earliest redaction we can have some knowledge of, and that — for a critical history — it can serve, at the very most, only as a source for the Buddhism of this period. But we also know that even this is problematic ... In fact, it is not until the time of the commentaries of Buddhaghosa, Dhammapala, and others — that is to say, the fifth to sixth centuries CE — that we can know anything definite about the actual contents of canon."{{sfn|Wynne|2007|pp=3–4}}|group=note}} | |||

| ====Upanishads==== | |||

| The Upanishads, composed in the late ], contain the first references to practices recognizable as classical yoga.{{sfn|Bryant|2009|p=xxi}} The first known appearance of the word "yoga" in the modern sense is in the ]{{sfn|Singleton|2010|pp=25–34}}{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=95}} (probably composed between the fifth and third centuries BCE),{{sfn|Phillips|2009|pp=28–30}}{{sfn|Olivelle|1998|pp=12–13}} where it is defined as steady control of the senses which{{snd}}with cessation of mental activity{{snd}}leads to a supreme state.{{sfn|Flood|1996|pp=94–95}}{{refn|For the date of this Upanishad see also Helmuth von Glasenapp, from the 1950 Proceedings of the "Akademie der Wissenschaften und Literatur"<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/vonglasenapp/wheel002.html |title=Vedanta and Buddhism, A Comparative Study |access-date=29 August 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130204142029/http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/vonglasenapp/wheel002.html |archive-date=4 February 2013 }}</ref>|group=note}} The Katha Upanishad integrates the ] of the early Upanishads with concepts of ] and yoga. It defines levels of existence by their proximity to one's ]. Yoga is viewed as a process of interiorization, or ascent of consciousness.{{sfn|Whicher|1998|pp=18–19}}{{sfn|Jacobsen|2011|p=8}} The upanishad is the earliest literary work which highlights the fundamentals of yoga. According to White, | |||

| {{blockquote|The earliest extant systematic account of yoga and a bridge from the earlier Vedic uses of the term is found in the Hindu Katha Upanisad (Ku), a scripture dating from about the third century BCE ... t describes the hierarchy of mind-body constituents—the senses, mind, intellect, etc.—that comprise the foundational categories of Sāmkhya philosophy, whose metaphysical system grounds the yoga of the Yogasutras, Bhagavad Gita, and other texts and schools (Ku3.10–11; 6.7–8).{{sfn|White|2011|p=4}}}} | |||

| The hymns in book two of the ] (another late-first-millennium BCE text) describe a procedure in which the body is upright, the breath is restrained and the mind is meditatively focused, preferably in a cave or a place that is simple and quiet.<ref>See: Original Sanskrit: {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110304112640/http://sanskritdocuments.org/all_pdf/shveta.pdf |date=4 March 2011 }} Book 2, Hymns 8–14;<br /> English Translation: ] (German: 1897; English Translated by Bedekar & Palsule, Reprint: 2010), Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Vol 1, Motilal Banarsidass, {{ISBN|978-8120814677}}, pages 309–310</ref>{{sfn|Singleton|2010|p=26}}{{sfn|Jacobsen|2011|p=8}} | |||

| The '']'', probably composed later than the Katha and Shvetashvatara Upanishads but before the ''Yoga Sutras of Patanjali'', mentions a sixfold yoga method: breath control, introspective withdrawal of the senses, meditation (''dhyana''), ], ], and ].{{sfn|Singleton|2010|pp=25–34}}{{sfn|Jacobsen|2011|p=8}}<ref>{{cite journal |title=Introducing Yoga's Great Literary Heritage |last=Feuerstein |first=Georg |author-link=Georg Feuerstein |journal=] |date=January–February 1988 |issue=78 |pages=70–75}}</ref> In addition to discussions in the Principal Upanishads, the twenty ] and related texts (such as '']'', composed between the sixth and 14th centuries CE) discuss yoga methods.{{sfn|Ayyangar|1938|p=2}}{{sfn|Ruff|2011|pp=97–112}} | |||

| ===={{anchor|Macedonian historical texts}}Macedonian texts==== | |||

| ] reached India in the 4th century BCE. In addition to his army, he brought Greek academics who wrote memoirs about its geography, people, and customs. One of Alexander's companions was ] (quoted in Book 15, Sections 63–65 by ] in his ''Geography''), who describes yogis.<ref name=charlesrl>Charles R Lanman, , Harvard Theological Review, Volume XI, Number 4, Harvard University Press, pages 355–359</ref> Onesicritus says that the yogis were aloof and adopted "different postures – standing or sitting or lying naked – and motionless".<ref name=strabo>Strabo, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221101030721/https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Strabo/15A3%2A.html#ref101 |date=1 November 2022 }} Book XV, Chapter 1, see Sections 63–65, Loeb Classical Library edition, Harvard University Press, Translator: H. L. Jones</ref> | |||

| Onesicritus also mentions attempts by his colleague, ], to meet them. Initially denied an audience, he was later invited because he was sent by a "king curious of wisdom and philosophy".<ref name=strabo /> Onesicritus and Calanus learn that the yogis consider life's best doctrines to "rid the spirit of not only pain, but also pleasure", that "man trains the body for toil in order that his opinions may be strengthened", that "there is no shame in life on frugal fare", and that "the best place to inhabit is one with scantiest equipment or outfit".<ref name=charlesrl /><ref name=strabo /> According to ], these principles are significant in the history of yoga's spiritual side and may reflect the roots of "undisturbed calmness" and "mindfulness through balance" in the later works of ] and ].<ref name=charlesrl /> | |||

| ====''Mahabharata'' and ''Bhagavad Gita''==== | |||

| ''Nirodhayoga'' (yoga of cessation), an early form of yoga, is described in the Mokshadharma section of the 12th chapter (''Shanti Parva'') of the third-century BCE '']''.{{sfn|Mallinson|Singleton|2017|pp=xii–xxii}} ''Nirodhayoga'' emphasizes progressive withdrawal from empirical consciousness, including thoughts and sensations, until ''purusha'' (self) is realized. Terms such as ''vichara'' (subtle reflection) and ''viveka'' (discrimination) similar to Patanjali's terminology are used, but not described.{{sfn|Whicher|1998|pp=25–26}} Although the ''Mahabharata'' contains no uniform yogic goal, the separation of self from matter and perception of ] everywhere are described as goals of yoga. ] and yoga are ], and some verses describe them as identical.{{sfn|Jacobsen|2011|p=9}} Mokshadharma also describes an early practice of elemental meditation.{{sfn|Wynne|2007|p=33}} The ''Mahabharata'' defines the purpose of yoga as uniting the individual '']'' with the universal Brahman pervading all things.{{sfn|Jacobsen|2011|p=9}} | |||

| ] narrating the ''Bhagavad Gita'' to ]]] | |||

| The '']'' (''Song of the Lord''), part of the ''Mahabharata'', contains extensive teachings about yoga. According to Mallinson and Singleton, the ''Gita'' "seeks to appropriate yoga from the renunciate milieu in which it originated, teaching that it is compatible with worldly activity carried out according to one's caste and life stage; it is only the fruits of one's actions that are to be renounced."{{sfn|Mallinson|Singleton|2017|pp=xii–xxii}} In addition to a chapter (chapter six) dedicated to traditional yoga practice (including meditation),{{sfn|Jacobsen|2011|p=10}} it introduces three significant types of yoga:{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=96}} | |||

| * ]: yoga of action{{sfn|Jacobsen|2011|pp=10–11}} | |||

| * ]: yoga of devotion{{sfn|Jacobsen|2011|pp=10–11}} | |||

| * ]: yoga of knowledge<ref>E. Easwaran, Essence of the Bhagavad Gita, Nilgiri Press, {{ISBN|978-1-58638-068-7}}, pages 117–118</ref><ref>Jack Hawley (2011), The Bhagavad Gita, {{ISBN|978-1-60868-014-6}}, pages 50, 130; Arvind Sharma (2000), Classical Hindu Thought: An Introduction, Oxford University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-19-564441-8}}, pages 114–122</ref> | |||

| The ''Gita'' consists of 18 chapters and 700 ''shlokas'' (verses);<ref name="bibekd">Bibek Debroy (2005), The Bhagavad Gita, Penguin Books, {{ISBN|978-0-14-400068-5}}, Introduction, pages x–xi</ref> each chapter is named for a different form of yoga.<ref name=bibekd />{{sfn|Jacobsen|2011|p=46}}<ref>Georg Feuerstein (2011), The Bhagavad Gita – A New Translation, Shambhala, {{ISBN|978-1-59030-893-6}}</ref> Some scholars divide the ''Gita'' into three sections; the first six chapters (280 ''shlokas'') deal with karma yoga, the middle six (209 ''shlokas'') with bhakti yoga, and the last six (211 ''shlokas'') with jnana yoga. However, elements of all three are found throughout the work.<ref name="bibekd" /> | |||

| ====Philosophical sutras==== | |||

| Yoga is discussed in the foundational ]s of ]. The '']'' of the ] school of Hinduism, composed between the sixth and second centuries BCE, discusses yoga.{{refn|group=note|The currently existing version of ''Vaiśeṣika Sūtra'' manuscript was likely finalized sometime between the 2nd century BCE and the start of the common era. Wezler has proposed that the Yoga related text may have been inserted into this Sutra later, among other things; however, Bronkhorst finds much to disagree on with Wezler.<ref name=Bronkhorst64/>}} According to ], the ''Vaiśeṣika Sūtra'' describes yoga as "a state where the mind resides only in the Self and therefore not in the senses".<ref name="Bronkhorst64">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AZbZDP8MRJoC&pg=PA64|title=The Two Traditions of Meditation in Ancient India |author=Johannes Bronkhorst |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |year=1993 |isbn=978-81-208-1114-0 |page=64}}</ref> This is equivalent to ''pratyahara'' (withdrawal of the senses). The sutra asserts that yoga leads to an absence of ''sukha'' (happiness) and ''dukkha'' (suffering), describing meditative steps in the journey towards spiritual liberation.<ref name="Bronkhorst64" /> | |||

| The '']'', the foundation text of the ] school of Hinduism, also discusses yoga.<ref name="Phillips2009p281">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uLqrAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA281 |title=Yoga, Karma, and Rebirth: A Brief History and Philosophy |author=Stephen Phillips |publisher=Columbia University Press |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-231-14485-8 |pages=281 footnote 36}}</ref> Estimated as completed in its surviving form between 450 BCE and 200 CE,<ref name="Nicholson2013p26">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AVusAgAAQBAJ |title=Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History |author=Andrew J. Nicholson |publisher=Columbia University Press |year=2013 |isbn=978-0-231-14987-7 |pages=26}}, "From a historical perspective, the Brahmasutras are best understood as a group of sutras composed by multiple authors over the course of hundreds of years, most likely composed in its current form between 400 and 450 BCE."</ref><ref name="nvisaeva36">NV Isaeva (1992), Shankara and Indian Philosophy, State University of New York Press, {{ISBN|978-0-7914-1281-7}}, page 36, ""on the whole, scholars are rather unanimous, considering the most probable date for Brahmasutra sometime between the 2nd-century BCE and the 2nd-century CE"</ref> its sutras assert that yoga is a means to attain "subtlety of body".<ref name="Phillips2009p281" /> The '']''—the foundation text of the ] school, estimated as composed between the sixth century BCE and the secondcentury CE<ref name="jfowlerpor129">Jeaneane Fowler (2002), Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism, Sussex Academic Press, {{ISBN|978-1898723943}}, page 129</ref><ref>B. K. Matilal (1986), "Perception. An Essay on Classical Indian Theories of Knowledge", Oxford University Press, p. xiv.</ref>—discusses yoga in sutras 4.2.38–50. It includes a discussion of yogic ethics, ] (meditation) and ], noting that debate and philosophy are also forms of yoga.<ref name="Phillips2009p297">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uLqrAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA281 |title=Yoga, Karma, and Rebirth: A Brief History and Philosophy |author=Stephen Phillips |publisher=Columbia University Press |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-231-14485-8 |pages=281 footnote 40, 297}}</ref><ref name="vidyabhushana137">SC Vidyabhushana (1913, Translator), , The Sacred Book of the Hindus, Volume VIII, Bhuvaneshvar Asrama Press, pages 137–139</ref><ref name="potterteip237">Karl Potter (2004), The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies: Indian metaphysics and epistemology, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass, {{ISBN|978-8120803091}}, page 237</ref> | |||

| ===Classical era (200 BCE – 500 CE)=== | |||

| The Indic traditions of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism were taking shape during the period between the ] and the ] eras (c. 200 BCE – 500 CE), and systems of yoga began to emerge;{{sfn|Larson|2008|p=36}} a number of texts from these traditions discussed and compiled yoga methods and practices. Key works of the era include the ''],'' the ''],'' the '']'', and the ''].'' | |||

| ==== ''Yoga Sutras of Patanjali'' ==== | |||

| ] as an avatar of the divine serpent ]]] | |||

| One of the best-known early expressions of ]ical yoga thought is the '']'' (early centuries CE,{{sfn|Bryant|2009|p=xxxiv}}{{sfn|Desmarais|2008|p=16-17}}{{efn|name="YS_dating"}} the original name of which may have been the ''Pātañjalayogaśāstra-sāṃkhya-pravacana'' (c. 325–425 CE); some scholars believe that it included the sutras and a commentary.{{sfn|Mallinson|Singleton|2017|pp=xvi–xvii}} As the name suggests, the metaphysical basis of the text is ]; the school is mentioned in Kauṭilya's ] as one of the three categories of ''anviksikis'' (philosophies), with yoga and '']''.<ref>Original Sanskrit: साङ्ख्यं योगो लोकायतं च इत्यान्वीक्षिकी |<br />English Translation: Kautiliya, R Shamasastry (Translator), page 9</ref><ref>Olivelle, Patrick (2013), King, Governance, and Law in Ancient India: Kautilya's Arthasastra, Oxford University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-19-989182-5}}, see Introduction</ref> Yoga and samkhya have some differences; yoga accepted the concept of a personal god, and Samkhya was a rational, non-theistic system of Hindu philosophy.<ref name="lpfl" />{{sfn|Burley|2012|pp=31–46}}{{sfn|Radhakrishnan|Moore|1967|p=453}} Patanjali's system is sometimes called "Seshvara Samkhya", distinguishing it from ]'s Nirivara Samkhya.{{sfn|Radhakrishnan|1971|p=344}} The parallels between yoga and samkhya were so close that ] says, "The two philosophies were in popular parlance distinguished from each other as Samkhya with and Samkhya without a Lord."{{sfn|Müller|1899|p=104}} ] wrote that the systematization of yoga which began in the middle and early Yoga Upanishads culminated in the ''Yoga Sutras of Patanjali''.{{refn|Werner writes, "The word Yoga appears here for the first time in its fully technical meaning, namely as a systematic training, and it already received a more or less clear formulation in some other middle Upanishads....Further process of the systematization of Yoga as a path to the ultimate mystic goal is obvious in subsequent Yoga Upanishads and the culmination of this endeavour is represented by Patanjali's codification of this path into a system of the eightfold Yoga."{{sfn|Werner|1998|p=24}}|group=note}} | |||

| {| class="wikitable floatright" | |||

| |+ Yoga Sutras of Patanjali{{sfn|Stiles|2001|p=x}} | |||

| |- | |||