| Revision as of 21:22, 23 March 2006 editKusma (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators59,522 edits Revert to revision 45057529 using popups← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:58, 18 December 2024 edit undo91.110.224.175 (talk)No edit summaryTags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Frankish military and political leader (c. 688–741)}} | |||

| {{Infobox Military Person | |||

| {{About|the Frankish ruler}} | |||

| |name= Charles Martel | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2019}} | |||

| |image= ] | |||

| {{Infobox royalty | |||

| |caption= Charles Martel is primarily famous for his victory at the ]. | |||

| | name = Charles Martel | |||

| |allegiance= | |||

| | title = {{plainlist| | |||

| |commands= | |||

| * ] | |||

| |nickname= "the Hammer" | |||

| * ] | |||

| |lived= ], ] - ], ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |placeofbirth= ] (]) | |||

| | image = Charles Martel 01.jpg | |||

| |portrayedby= | |||

| | caption = 1839 sculpture of Charles by ], located in the ]<ref>{{Cite web |title=Les collections – Château de Versailles |url=https://collections.chateauversailles.fr/#d9907040-29a2-4e2f-bf19-b508f28802bd |access-date=2024-01-17 |website=collections.chateauversailles.fr}}</ref> | |||

| | succession = ] | |||

| | reign = 718 – 22 October 741 | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | successor = {{plainlist| | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| }} | |||

| | succession1 = ] of ] | |||

| | reign1 = 715 – 22 October 741 | |||

| | predecessor1 = ] | |||

| | successor1 = ] | |||

| | succession2 = ] of ] | |||

| | reign2 = 718 – 22 October 741 | |||

| | predecessor2 = ] | |||

| | successor2 = ] | |||

| | spouse = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | issue = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | house = ] <br/>] (founder) | |||

| | father = ] | |||

| | mother = ] | |||

| | birth_date = 23 August c. 686 or 688<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fouracre |first=Paul |date=2000 |title=The Age of Charles Martel |location=Harlow, England |publisher=Longman |pages=1, 55 |isbn=0582064759 |oclc=43634337}}</ref> | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] | |||

| | death_date = 22 October 741 (aged 51–53) | |||

| | death_place = ], ] | |||

| | place of burial = ] | |||

| | signature = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Campaignbox Charles Martel}} | {{Campaignbox Charles Martel}} | ||

| {{dablink|For the 13th century titular King of Hungary, see ].}} | |||

| '''Charles Martel''' ({{IPAc-en|m|ɑr|ˈ|t|ɛ|l}}; {{circa|688}} – 22 October 741),<ref name="EB1911">{{Cite EB1911|wstitle= Charles Martel |volume= 5 |last= Pfister |first= Christian |author-link= Christian Pfister | pages = 942–943 }}</ref> ''Martel'' being a sobriquet in Old French for "The Hammer", was a ] political and military leader who, as ] and ], was the de facto ruler of the Franks from 718 until his death.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Schulman |first=Jana K. |title=The Rise of the Medieval World, 500–1300: A Biographical Dictionary |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=f_jLbHTM_zgC&pg=PA101 |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |year=2002 |page=101 |isbn=0-313-30817-9}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Cawthorne |first=Nigel |author-link=Nigel Cawthorne |title=Military Commanders: The 100 Greatest Throughout History |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F-QawgVmYn8C&pg=PA52 |publisher=Enchanted Lion Books |year=2004 |pages=52–53 |isbn=1-59270-029-2}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Kibler |first1=William W. |last2=Zinn |first2=Grover A. |title=Medieval France: An Encyclopedia |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4qFY1jpF2JAC&pg=PA205 |publisher=] |year=1995 |pages=205–206 |isbn=0-8240-4444-4}}</ref> He was a son of the Frankish statesman ] and a noblewoman named ]. Charles successfully asserted his claims to power as successor to his father as the ] in Frankish politics. Continuing and building on his father's work, he restored ] in Francia and began the series of military campaigns that re-established the Franks as the undisputed masters of all ]. According to a near-contemporary source, the '']'', Charles was "a warrior who was uncommonly ... effective in battle".<ref>{{Cite book |editor1-last=Fouracre |editor1-first=Paul |editor2-last=Gerberding |editor2-first=Richard A. |title=Late Merovingian France: history and hagiography, 640–720 |date=1996 |publisher=Manchester University Press |translator=Paul Fouracre and Richard A. Gerberding |isbn=0719047900 |location=Manchester |page=93 |oclc=32699266}}</ref> | |||

| '''Charles Martel''' (or, in ], Charles ''the Hammer'') (], ] – ] ]) was ] of the three kingdoms of the Franks. He is best remembered for winning the ] in ], which has traditionally been characterised as saving ] from the ]'s expansion beyond the ]. Martel's Frankish army defeated an ] army that had crushed all resistance before it. | |||

| Charles gained a very consequential victory against an Umayyad invasion of Aquitaine at the ], at a time when the ] controlled most of the ]. Alongside his military endeavours, Charles has been traditionally credited with an influential role in the development of the Frankish system of ].<ref>{{cite book|author1-last=White, Jr.|author1-first=Lynn|title=Medieval technology and social change|date=1962|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=London, England|pages=2–14}}</ref><ref>Mclaughlin, William, ": Charles Martel the 'Hammer' preserves Western Christianity", War History Online.</ref> | |||

| Martel was born in ], in what is now ], ], the illegitimate son of ] (] or ] – ], ]) and his concubine ] (or Chalpaida). | |||

| At the end of his reign, Charles divided Francia between his sons, ] and ]. The latter became the first king of the ]. Pepin's son ], grandson of Charles, extended the Frankish realms and became the first emperor in the West since the ].<ref name="Fouracre00">Fouracre, Paul (2000). . London: Longman. {{ISBN|0-582-06475-9}}. Accessed 2 August 2015.{{page needed|date=August 2015}}</ref> | |||

| ==Consolidation of power== | |||

| In December 714, Pippin the Middle died. He had, at his wife ]'s urging, designated ], his grandson by Plectrude's son ], his heir in the entire realm. This, however was immediately opposed by the nobles, for Theudoald was a child of eight years. Plectrude, however, was a vigorous woman and she immediately seized Charles Martel, her husband's eldest surviving son, a bastard, and put him in prison in ], the city which was destined to be her capital. This prevented an uprising on his behalf in ], but not in ]. | |||

| == Background == | |||

| ===Civil war of 715-718=== | |||

| Charles, nicknamed "Martel" ("the Hammer") in later chronicles, was a son of ] and his mistress, possible second wife, ].<ref>{{cite book|title=Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia|date=2002|publisher=Yorkin Publications|isbn=0-7876-4074-3|editor1-last=Commire|editor1-first=Anne|location=Waterford, Connecticut|chapter=Alphaida (c. 654–c. 714)|chapter-url=http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G2-2591300322.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924170313/http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G2-2591300322.html|archive-date=2015-09-24|url-status=dead|chapter-url-access=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Hanson|first=Victor Davis|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XGr16-CxpH8C|title=Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise to Western Power|date=2007-12-18|publisher=Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group|isbn=978-0-307-42518-8|language=en}}</ref> He had a brother named ], who later became the Frankish ''dux'' (that is, ''duke'') of ].<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|last=Commire|first=Anne|date=2015-09-24|orig-year=2002|title=Alphaida (c. 654–c. 714) – Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia |url=http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G2-2591300322.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924170313/http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G2-2591300322.html|archive-date=24 September 2015|access-date=2020-09-24|publisher=Yorkin Publications|publication-place=Waterford, Connecticut}}</ref>And is the great grandson of ]. | |||

| In ], the Neustrian noblesse proclaimed one ] ] on behalf of, and apparently with the support of, ], the young king, who in fact had the legal authority to select a mayor, though by this time the ] dynasty had lost most such regal powers. | |||

| Older historiography commonly describes Charles as "illegitimate", but the dividing line between wives and concubines was not clear-cut in eighth-century Francia. It is likely that the accusation of "illegitimacy" derives from the desire of Pepin's first wife ] to see her progeny as heirs to Pepin's throne.<ref name="Matthiesen Verlag">{{cite book|author1-last=Joch|author1-first=Waltraud|title=Legitimität und Integration: Untersuchungen zu den Anfängen Karl Martells|date=1999|publisher=Matthiesen Verlag|location=Husum, Germany}}</ref><ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite news|author1-last=Gerberding|author1-first=Richard A.|title=Review of ''Legitimität und Integration: Untersuchungen zu den Anfängen Karl Martells'' by Waltraud Joch|date=October 2002|journal=Speculum|volume=77|number=4|pages=1322–1323}}</ref> | |||

| The Austrasians were not to be left supporting a woman and her young boy for long. Before the end of the year, Charles Martel had escaped from prison and been acclaimed mayor by the nobles of that kingdom. The Neustrians had been attacking Austrasia and the nobles were waiting for a strong man to lead them against their invading countrymen. That year, Dagobert died and the Neustrians proclaimed ] king without the support of the rest of the Frankish people. | |||

| By Charles's lifetime the ]s had ceded power to the ], who controlled the royal treasury, dispensed patronage, and granted land and privileges in the name of the figurehead king. Charles's father, Pepin of Herstal, had united the Frankish realm by conquering ] and ]. Pepin was the first to call himself Duke and Prince of the Franks, a title later taken up by Charles. | |||

| In ], Chilperic and Ragenfrid together led an army into Austrasia. The Neustrians allied with another invading force under ] and met Charles in battle near Cologne, still held by Plectrude. Chilperic and Ragenfrid were victorious and Charles fled to the mountains of the ]. The king and his mayor then turned to besiege their other rival in the city and took it, the treasury, and received the recognition of both Chilperic as king and Ragenfrid as mayor. | |||

| == Contesting for power == | |||

| At this juncture, events turned in favour of Charles. Charles fell upon the triumphant army, as it returned to its own province, near ] and, in the ensuing Battle of ], routed them and they fled. Hereafter, Charles remained virtually undefeated until his death. | |||

| ] | |||

| In December 714, ] died.<ref name=Kurth> Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909</ref> A few months before his death and shortly after the murder of his son ], he had taken the advice of his wife ] to designate as his sole heir ], his grandson by their deceased son ]. This was immediately opposed by the Austrasian nobles because Theudoald was a child of only eight years of age. To prevent Charles using this unrest to his own advantage, Plectrude had him imprisoned in ], the city which was intended to be her capital. This prevented an uprising on his behalf in ], but not in ]. | |||

| In Spring ], Charles returned to Neustria with an army and confirmed his supremacy with a victory at ], near ]. He chased the fleeing king and mayor to ] before turning back to deal with Plectrude and Cologne. He took the city and dispersed her adherents. On this success, he proclaimed one ] king of Austrasia in opposition to Chilperic and deposed the ], ], replacing him with one ]. | |||

| {{carolingians}} | |||

| === Civil war of 715–718 === | |||

| After subjugating all Austrasia to his hand, he marched against Radbod and pushed him back into his territory, even forcing the concession of ] (later ]). He also sent the ] back over the ] and thus secured his realms borders — in the name of the new king, of course. More than any other prior mayor of the palace, however, absolute power lay with Charles Martel, though he never cared about titles; his son did, and finally asked the ] "who should be King, he who has the title, or he who has the power?" The Pope, highly dependent on Frankish armies for his independence from Lombard and Bzyantine power (the ] still considered himself to be the only legitimate "Roman" Emperor, and thus, ruler of all of the provinces of the ancient empire, whether recognised or not), declared for "he who had the power" and immediately crowned Pippin. Decades later, in ], Pippin's son, ], was crowned emperor by the pope, further extending the "he who had the power" principle by delegitimising the nominal authority of the Byzantine emperor in the Italian peninsula (which had, by then, shrunk to little more than ] and ] at best) and ancient Roman Gaul, including the Iberian outposts Charlmagne had established in the '']'' across the ], what today forms ]. In short, though the Byzantine Emperor claimed authority over all the old ], as the legitimate "Roman" Emperor, and this may have been legally true, it was simply not reality. The bulk of the ] had come under Carolingian rule, the Bzyantine Emperor having had almost no authority in the West since the ], though Charlemagne, a consummate politican, preferred to avoid an open breach with Constantinople. What was occurring was the birth of an institution unique in history: the ]. Though the sardonic ] ridiculed its nomenclature, saying that the Holy Roman Empire was "neither Holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire," it constitued an enormous political power for a time, especially under the ] and ] and, to a lesser, extent, the ]. It lasted until ], by then a nonentity. Though his grandson became it's first emperor, the "empire" such as it was, was largely born during the reign of Charles Martel. | |||

| {{Carolingians|315px}} | |||

| Pepin's death occasioned open conflict between his heirs and the Neustrian nobles who sought political independence from Austrasian control. In 715, ] named ] ]. On 26 September 715, Raganfrid's Neustrians met the young Theudoald's forces at the ]. Theudoald was defeated and fled back to Cologne. Before the end of the year, Charles had escaped from prison and been acclaimed mayor by the nobles of Austrasia.<ref name=Kurth /> That same year, Dagobert III died and the Neustrians proclaimed ], the cloistered son of ], as king. | |||

| ==== Battle of Cologne ==== | |||

| In ], Chilperic, in response to Charles new ascendancy, allied with ] (or Eudes, as he is sometimes known), the ] who had made himself independent during the civil war in 715, but was again defeated, at ], by Charles. The king fled with his ducal ally to the land south of the ] and Ragenfrid fled to ]. Soon Clotaire IV died and Odo gave up on Chilperic and, in exchange for recognising his kingship over all the Franks, the king surrendered his kingdom to the mayoralty of Charles over all the kingdoms (718). | |||

| {{main|Battle of Cologne}} | |||

| In 716, Chilperic and Raganfrid together led an army into Austrasia intent on seizing the Pippinid wealth at Cologne. The Neustrians allied with another invading force under ] and met Charles in battle near ], which was still held by Plectrude. Charles had little time to gather men or prepare and the result was inevitable. The Frisians held off Charles, while the king and his mayor besieged Plectrude at Cologne, where she bought them off with a substantial portion of Pepin's treasure. After that they withdrew.<ref name="Costambeys">Costambeys, Marios; Matthew Innes & MacLean, Simon (2011) ''The Carolingian World,'' p. 43, Cambridge, GBR: Cambridge University Press, see , accessed 2 August 2015.</ref> The Battle of Cologne is the only defeat of Charles's career. | |||

| === |

==== Battle of Amblève ==== | ||

| {{main|Battle of Amblève}} | |||

| The ensuing years were full of strife. Between 718 and 723, Charles secured his power through a series of victories: he won the loyalty of several important bishops and abbots (by donating lands and money for the foundation of abbeys such as ]), he subjugated ] and ], and he defeated the pagan ]. | |||

| Charles retreated to the hills of the ] to gather and train men. In April 716, he fell upon the triumphant army near ] as it was returning to Neustria. In the ensuing ], Charles attacked as the enemy rested at midday. According to one source, he split his forces into several groups which fell at them from many sides.<ref> Daniel, Gabriel. ''The History of France'', G. Strahan, 1726, p. 148]</ref> Another suggests that while this was his intention, he then decided, given the enemy's unpreparedness, this was not necessary. In any event, the suddenness of the assault led them to believe they were facing a much larger host. Many of the enemy fled and Charles's troops gathered the spoils of the camp. His reputation increased considerably as a result, and he attracted more followers. This battle is often considered by historians as the turning point in Charles's struggle.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Age of Charles Martel|last=Fouracre|first=Paul|date=2000|publisher=Longman|isbn=0582064759|location=Harlow, England|pages=61|oclc=43634337}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Battle of Vincy ==== | |||

| Having unified the Franks under his banner, Charles was determined to punish the Saxons who had invaded Austrasia. Therefore, late in 718, he laid waste their country to the banks of the ], the ], and the ], and the ]. In ], Charles seized ] without any great resistance on the part of the ], who had been subjects of the Franks but had seized control upon the death of Pippin. Charles did not trust the pagans, but their ruler, ], accepted Christianity in his realm and ], ], the famous Apostle to the Frisians, went to convert them at Charles behest. Charles also did much to support Winfrid, later ], the Apostle of the Germans. | |||

| {{main|Battle of Vincy}} | |||

| ] points out that up to this time, much of Charles's support was probably from his mother's kindred in the lands around Liege. After Amblève, he seems to have won the backing of the influential ], founder of the ]. The abbey had been built on land donated by Plectrude's mother, ], but most of Willibrord's missionary work had been carried out in Frisia. In joining Chilperic and Raganfrid, Radbod of Frisia sacked Utrecht, burning churches and killing many missionaries. Willibrord and his monks were forced to flee to Echternach. Gerberding suggests that Willibrord had decided that the chances of preserving his life's work were better with a successful field commander like Charles than with Plectrude in Cologne. Willibrord subsequently baptized Charles's son ]. Gerberding suggests a likely date of Easter 716.<ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.medievalists.net/2014/11/716-crucial-year-charles-martel/| title = Gerberding, Richard. "716: A Crucial Year For Charles Martel", Medievalists.net, November 3, 2014| date = 3 November 2014}}</ref> Charles also received support from bishop Pepo of Verdun. | |||

| Charles took time to rally more men and prepare. By the following spring, he had attracted enough support to invade Neustria. Charles sent an envoy who proposed a cessation of hostilities if Chilperic would recognize his rights as mayor of the palace in Austrasia. The refusal was not unexpected but served to impress upon Charles's forces the unreasonableness of the Neustrians. They met near Cambrai at the ] on 21 March 717. The victorious Charles pursued the fleeing king and mayor to Paris, but as he was not yet prepared to hold the city, he turned back to deal with Plectrude and Cologne. He took the city and dispersed her adherents. Plectrude was allowed to retire to a convent. Theudoald lived to 741 under his uncle's protection. | |||

| When Chilperic II died the following year (]), Charles appointed as his successor the son of Dagobert III, ], who was still a minor, and who occupied the throne from 720 to 737. Charles was now appointing the kings whom he supposedly served, these ''rois fainéants'' were mere puppets in his hands and by the end of his reign, they were so useless, he didn't even bother appointing one. At this time, Charles again marched against the Saxons. Then, the Neustrians rebelled under Ragenfrid, who had been left the county of Anjou. They were easily defeated (]), but Ragenfrid gave up his sons as hostages in turn for keeping his county. This ended the civil wars of Charles' reign. | |||

| == Consolidation of power == | |||

| The next six years were devoted in their entirity to assuring Frankish authority over the dependent Germanic tribes. Between 720 and ], Charles was fighting in Bavaria, where the ] dukes had gradually evolved into independent rulers, recently in alliance with ]. He forced the ] to accompany him, and Duke ] submitted to Frankish suzerainty. In ] and ], he again entered Bavaria and the ties of lordship seemed strong. From his first campaign, he brought back the Agilolfing princess Swanachild, who apparently became his concubine. In ], he marched against ], duke of Alemannia, who had also become independent, and killed him in battle. He forced the Alemanni capitulation to Frankish suzerainty and did not appoint a successor to Lantfrid. Thus, southern Germany once more became part of the Frankish kingdom, as had northern Germany during the first years of the reign. | |||

| Upon this success, Charles proclaimed ] king in ] in opposition to Chilperic and deposed ], ], replacing him with ], a lifelong supporter. | |||

| In 718, Chilperic responded to Charles's new ascendancy by making an alliance with ] (or Eudes, as he is sometimes known), the ], who had become independent during the civil war in 715, but was again defeated, at the ], by Charles.<ref name="Strauss">Strauss, Gustave Louis M. (1854) ''Moslem and Frank; or, Charles Martel and the rescue of Europe,'' Oxford, GBR:Oxford University Press, see , accessed 2 August 2015.{{page needed|date=August 2015}}</ref> Chilperic fled with his ducal ally to the land south of the ] and Raganfrid fled to ]. Soon Chlotar IV died and Odo surrendered King Chilperic in exchange for Charles recognizing his dukedom. Charles recognized Chilperic as king of the Franks in return for legitimate royal affirmation of his own mayoralty over all the kingdoms. | |||

| But by 730, his own realm secure, Charles began to prepare exclusively for the coming storm from the west. In ], the ] had built up a strong army from ], ], and ] to conquer Aquitaine, the large duchy in the southwest of Gaul, nominally under Frankish sovereignty, but in practice almost independent in the hands of the Odo the Great since the Merovingian kings had lost power. The invading Muslims besieged the city of Toulouse, then Aquitaine's most important city, and Odo immediately left to find help. He returned three months later just before the city was about to surrender and defeated the Muslim invaders on ], ], at what is now known as the ]. The defeat was essentially the result of a classic enveloping movement on Odo's part. After Odo originally fled, the Muslims became overconfident and, instead of maintaining strong outer defenses around their siege camp and continuing scouting, did neither. Thus, when Odo returned, he was able to launch a near complete surprise attack on the besieging force, scattering it at the first attack, and slaughtering units which were resting, or who fled without weapons or armour. | |||

| === Wars of 718–732 === | |||

| Charles had watched the Iberian situation since Toulouse, convinced the Muslims would return, and while he was securing his own realms, he was also preparing for war against the ]s. It is vital to note that Charles had used an extremely — for the time — controversial method of maintaining a standing army, one he could train as a core of veterans to add to the usual conscripts the Franks called up in time of war. During the ], troops were only available after the crops had been planted, and before harvesting time. Charles believed he needed a standing army, one he could train, to counter the Muslim heavy cavalry, of which, at the time, he had none. To train the kind of infantry which could withstand heavy cavalry, Charles needed them year-round, and he needed to pay them, so their families could buy the food they would have otherwise grown. To obtain this money, he seized church lands and property, and used the funds to pay his soldiers. The same Charles who had secured the support of the ''ecclesia'' by donating land, seized some of it back between 724 and 732. The Church was enraged, and, for a time, it looked as though Charles might even be excommunicated for his actions. But then came a significant invasions . . . | |||

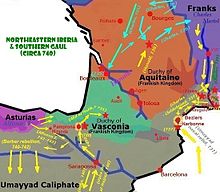

| ].]] | |||

| Between 718 and 732, Charles secured his power through a series of victories. Having unified the Franks under his banner, Charles was determined to punish the Saxons who had invaded Austrasia. Therefore, late in 718, he laid waste their country to the banks of the ], the ], and the ].<ref name=Kurth/> He defeated them in the ] and thus secured the Frankish border. | |||

| When the Frisian leader ] died in 719, Charles seized West Frisia without any great resistance on the part of the ], who had been subjected to the Franks but had rebelled upon the death of Pippin. When Chilperic II died in 721, Charles appointed as his successor the son of Dagobert III, ], who was still a minor, and who occupied the throne from 721 to 737. Charles was now appointing the kings whom he supposedly served ('']''). By the end of his reign, he didn't appoint any at all. At this time, Charles again marched against the Saxons. Then the Neustrians rebelled under Raganfrid, who had left the county of Anjou. They were easily defeated in 724 but Raganfrid gave up his sons as hostages in turn for keeping his county. This ended the civil wars of Charles' reign. | |||

| ===Eve of Tours=== | |||

| It has been noted that Charles Martel could have pursued the wars against the Saxons—but he was determined to prepare for what he thought was a greater danger. Instead of concentrating on conquest to his east, he prepared for the storm gathering in the west. Well aware of the danger posed by the ]s after the ], in ], it has been explained that he used the intervening years to consolidate his power, and gather and train a veteran army that would stand ready to defend ] itself (at ]). Moreover, after his victory at ], Martel continued on in campaigns in ]-] to drive other Muslim armies from bases in ] after they again attempted to get a foothold in ] beyond ]. ] calles Martel "the paramount prince of his age." | |||

| The next six years were devoted in their entirety to assuring Frankish authority over the neighboring political groups. Between 720 and 723, Charles was fighting in Bavaria, where the ] dukes had gradually evolved into independent rulers, recently in alliance with ]. He forced the ] to accompany him, and Duke ] submitted to Frankish suzerainty. In 725 he brought back the Agilolfing Princess Swanachild as a second wife. | |||

| It is also vital to note that the Muslims were not aware, at that time, of the true strength of the Franks, or the fact that they were building a real army, not the typical barbarian hordes which had infested Europe after Rome's fall. They considered the Germanic tribes, of which the Franks were part, simply barbarians, and were not particularly concerned about them. (the Arab Chronicles, the history of that age, show that awareness of the Franks as a growing military power only came after the Battle of Tours when the Caliph expressed shock at his army's disastrous defeat) Thus, when they launched their great invasion of 732, they were not prepared to confront Charles Martel and his Frankish army. This, in retrospect, was a disastrous mistake. Emir Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi was a good general and should have done two things he utterly failed to do. He assumed that the Franks would not come to the aid of their Aquitanian cousins, and thus failed to assess their strength in advance of invasion. He also failed to scout the movements of the Frankish army. Having done either, he would have curtailed his lighthorse ravaging throughout lower Gaul, and marched at once with his full power against the Franks. This would not have allowed Charles Martel to pick the time and place the two powers would collide, which all historians agree was pivotal to his victory. | |||

| In 725 and 728, he again entered Bavaria but, in 730, he marched against ], Duke of Alemannia, who had also become independent, and killed him in battle. He forced the Alemanni to capitulate to Frankish suzerainty and did not appoint a successor to Lantfrid. Thus, southern Germany once more became part of the Frankish kingdom, as had northern Germany during the first years of the reign. | |||

| ==Battle of Tours== | |||

| :''Main article ]''. | |||

| == Aquitaine and the Battle of Tours in 732 == | |||

| ===Leadup and importance=== | |||

| {{Main|Battle of Tours}} | |||

| The ]n ] had previously invaded ] and had been stopped in its northward sweep at the Battle of Toulouse, in 721. The hero of that less celebrated event had been Odo the Great, Duke of Aquitane, who was not the progenitor of a race of kings and patron of chroniclers. It has previously been explained how Odo defeated the invading Muslims, but when they returned, things were far different. In the interim, the arrival of a new ], ], who brought with him a huge force of Arabs and ] horsemen, triggered a far greater invasion. This time the Muslim horsemen were ready for battle, and the results were horrific for the Aquintanians. Odo, hero of Toulouse, was badly defeated in the Muslim invasion of ] at the ]—where the western chroniclers state, "God alone knows the number of the slain"—and fled to Charles, seeking help. Thus, Odo faded into history, and Charles marched into it. | |||

| In 731, after defeating the Saxons, Charles turned his attention to the rival southern realm of Aquitaine, and crossed the Loire, breaking the treaty with Duke Odo. The Franks ransacked Aquitaine twice, and captured ], although Odo retook it. The ''Continuations of Fredegar'' allege that Odo called on assistance from the recently established emirate of al-Andalus, but there had been Arab raids into Aquitaine from the 720s onwards. Indeed, the anonymous ] records a victory for Odo in 721 at the ], while the '']'' records that Odo had killed 375,000 Saracens.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Age of Charles Martel|last=Fouracre|first=Paul|date=2000|publisher=Longman|isbn=0582064759|location=Harlow, England|pages=84–5|oclc=43634337}}</ref> It is more likely that this invasion or raid took place in revenge for Odo's support for a rebel Berber leader named ]. | |||

| Whatever the precise circumstances were, it is clear that an army under the leadership of ] headed north, and after some minor engagements marched on the wealthy city of Tours. According to British medieval historian ], "Their campaign should perhaps be interpreted as a long-distance raid rather than the beginning of a war".<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Age of Charles Martel|last=Fouracre|first=Paul|date=2000|publisher=Longman|isbn=0582064759|location=Harlow, England|pages=88|oclc=43634337}}</ref> They were, however, defeated by the army of Charles at the ] (known in France as the Battle of Poitiers), at a location between the French cities of ] and ], in a victory described by the ''Continuations of Fredegar''. According to the historian ], the Arab army, mostly mounted, failed to break through the Frankish infantry.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bachrach |first=Bernard S. |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/43095805 |title=Early Carolingian warfare : prelude to empire |date=2001 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |isbn=0-8122-3533-9 |location=Philadelphia |pages=170–178 |oclc=43095805}}</ref> News of this battle spread, and may be recorded in Bede's ] (Book V, ch. 23). However, it is not given prominence in Arabic sources from the period.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Christys|first=Ann|title=Sons of Ishmael, Turn Back!|year=2019|chapter-url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781316941072%23CN-bp-20/type/book_part|series=East and West in the Early Middle Ages|pages=318–328|editor-last=Esders|editor-first=Stefan|edition=1|publisher=Cambridge University Press|doi=10.1017/9781316941072.021|isbn=9781316941072|access-date=2019-05-07|editor2-last=Fox|editor2-first=Yaniv|editor3-last=Hen|editor3-first=Yitzhak|editor4-last=Sarti|editor4-first=Laury|chapter='Sons of Ishmael, Turn Back!'|s2cid=166413345 }}</ref> | |||

| The ] earned Charles the ] "Martel", for the merciless way he hammered his enemies. Many historians, including the great military historian ], believe that had he failed at Tours, ] would probably have overrun ], and perhaps the remainder of western Christian Europe. No power existed, had Martel fallen at Tours, to stop the Muslims from conquering and occupying Italy, and Rome, in addition to all of Western Europe. Certainly Gibbon made clear he believed the Muslims would have conquered from Rome to the Rhine, and even England, with ease, had Martel not prevailed. Other reputable historians that echo Creasy's belief that this battle was central to the halt of Islamic expansion into Europe include William Watson, and Edward Gibbon believed the fate of ] hinged on this battle. This opinion was very popular for most of modern historiography, but it fell somewhat out of style in the ]. Some historians, such as Bernard Lewis, claimed that Arabs had little intention of occupying northern France. This opinion has once more fallen out of style and the Battle of Tours is usually considered by historian's today as a very significant event in the history of Europe and Christianity. | |||

| Despite his victory, Charles did not gain full control of Aquitaine, and Odo remained duke until 735. | |||

| In the modern era, Norwich, the the most widely read authority on the ], says the Franks halting Muslim Expansion at Tours literally preserved Christianity as we know it. A more realistic viewpoint may be found in ''Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels'' by Antonio Santosuosso, Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Western Ontario, and considered an expert historian in the era in dispute in this article. It was published in 2004, and has quite an interesting modern expert opinion on Charles Martel, Tours, and the subsequent campaigns against Rahman's successor in 736-737. Santosuosso makes a compelling case that these defeats of invading Muslim Armies, were at least as important as Tours in their defense of western Christianity, and the preservation of those Christian monasteries and centers of learning which ultimately led Europe out of the dark ages. He also makes a compelling case that while Tours was unquestionably of macrohistorical importance, the later battles were at least equally so. Both invading forces defeated in those campaigns had come to set up permanent outposts for expansion, and there can be no doubt that these three defeats combined broke the back of European expansion by Islam while the Caliphate was still united. While some modern assessments of the battle's impact have backed away from the extreme of Gibbon's position, Gibbons's conjecture is supported by other historians such as Edward Shepard Creasy and William E. Watson. Most modern historians such as Norwich and Santosuosso generally support the concept of Tours as a macrohistorical event favoring western civilization and Christianity . Military writers such as Robert W. Martin, "''The Battle of Tours is still felt today"'', also argue that Tours was such a turning point in favor of western civilization and Christianity that its aftereffect remains to this day. This is the majority view of the battle as it is viewed today. | |||

| == Wars of 732–737 == | |||

| ===Battle=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The Battle of Tours probably took place somewhere between Tours and ] (hence its other name: Battle of Poitiers). The Frankish army, under Charles Martel, consisted mostly of veteran ], somewhere between 15,000 and 75,000 men. Responding to the Muslim invasion, the Franks had avoided the old Roman roads, hoping to take the invaders by surprise. Martel believed it was absolutely essential that he not only take the Muslims by surprise, but that he be allowed to select the ground on which the battle would be fought, ideally a high, wooded, plain where the Islamic horsemen, already tired from carrying armour, would be further exhausted charging uphill. Further, the woods would aid the Franks in their defensive square by partially impeding the ability of the Muslim horesmen from making a clear charge. | |||

| Between his victory of 732 and 735, Charles reorganized the kingdom of ], replacing the counts and dukes with his loyal supporters, thus strengthening his hold on power. He was forced, by the ventures of ], to invade independent-minded Frisia again in 734. In that year, he slew the duke at the ]. Charles ordered the Frisian pagan shrines destroyed, and so wholly subjugated the populace that the region was peaceful for twenty years after. | |||

| From the Muslim accounts of the battle, they were indeed taken by surprise to find a large force opposing their expected sack of Tours, and they waited for six days, scouting the enemy. They did not like charging uphill, against an unknown number of foe, who seemed well disciplined and well disposed for battle. But the weather was also a factor. The Germanic Franks, in their wolf and bear pelts, were more used the cold, better dressed for it, and despite not having tents, which the Muslims did, were prepared to wait as long as needed, the fall only growing colder. | |||

| In 735, Duke Odo of Aquitaine died. Though Charles wished to rule the duchy directly and went there to elicit the submission of the Aquitanians, the aristocracy proclaimed Odo's son, ], as duke, and Charles and Hunald eventually recognised each other's position. | |||

| On the seventh day, the Muslim army, consisting of between 60,000 and 400,000 horsemen and led by Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, attacked. During the battle, the Franks defeated the Islamic army and the emir was killed. While Western accounts are sketchy, Arab accounts are fairly detailed in describing how the Franks formed a large square and fought a brilliant defensive battle. Rahman had doubts before the battle that his men were ready for such a struggle, and should have had them abandon the loot which hindered them, but instead decided to trust his horsemen, who had never failed him. Indeed, it was thought impossible for infantry of that age to withstand armoured mounted warriors. Martel managed to inspire his men to stand firm against a force which must have seemed invincible to them, huge mailed horsemen, who in addition probably badly outnumbered the Franks. In one of the rare instances where medieval infantry stood up against cavalry charges, the disciplined Frankish soldiers withstood the assaults, though according to Arab sources, the Arab cavalry several times broke into the interior of the Frankish square. But despite this, Franks did not break, and it is probably best expressed by a translation of an Arab account of the battle from the Medieval Source Book: "And in the shock of the battle the men of the North seemed like North a sea that cannot be moved. Firmly they stood, one close to another, forming as it were a bulwark of ice; and with great blows of their swords they hewed down the Arabs. Drawn up in a band around their chief, the people of the Austrasians carried all before them. Their tireless hands drove their swords down to the breasts of the foe." Both Western and Muslim accounts of the battle agree that sometime during the height of the fighting, scouts sent by Martel to the Muslim camp began freeing prisoners, and fearing loss of their plunder, a large portion of the Muslim army abandoned the battle, and returned to camp to protect their spoils. In attempting to stop what appeared to be a retreat, Abdul Rahman was surrounded and killed by the Franks, and what started as a ruse ended up a real retreat, as the Muslim army fled the field that day. They could have probably resumed the battle the following morning, but Rahman's death led to bickering between the surviving generals, and the Arabs abandoned the battlefield the day after his death, leaving Martel a unique place in history as the savior of Europe and a brilliant general in an age not known for its generalship. Martel's Franks, virtually all infantry without armour, managed to withstand mailed horsemen, without the aid of bows or firearms, a feat of arms almost unheard of in medieval history. | |||

| == Interregnum (737–741) == | |||

| ==After Tours== | |||

| In 737, at the tail end of his campaigning in Provence and ], the Merovingian king, Theuderic IV, died. Charles, titling himself ''maior domus'' and ''princeps et dux Francorum'', did not appoint a new king and nobody acclaimed one. The throne lay vacant until Charles' death. The interregnum, the final four years of Charles' life, was relatively peaceful although in 738 he compelled the Saxons of ] to submit and pay tribute and in 739 he checked an uprising in Provence where some rebels united under the leadership of ]. | |||

| In the subsequent decade, Charles led the Frankish army against the eastern duchies, Bavaria and Alemannia, and the southern duchies, ] and ]. He dealt with the ongoing conflict with the ]ns and ] to his northeast with some success, but full conquest of the Saxons and their incorporation into the Frankish empire would wait for his grandson Charlemagne, primarily because Martel concentrated the bulk of his efforts against Muslim expansion. | |||

| Charles used the relative peace to set about integrating the outlying realms of his empire into the Frankish church. He erected four dioceses in Bavaria (], ], ], and ]) and gave them ] as ] and ] over all Germany east of the Rhine, with his seat at ]. Boniface had been under his protection from 723 on. Indeed, the saint himself explained to his old friend, ], that without it he could neither administer his church, defend his clergy nor prevent idolatry. | |||

| So instead of concentrating on conquest to his east, he continued expanding Frankish authority in the west, and denying the Emirite of Córdoba a foothold in Europe. After his victory at Tours, Martel continued on in campaigns in ] and ] to drive other Muslim armies from bases in Gaul after they again attempted to get a foothold in Europe beyond al-Andalus. His victories at Berre and Narbonne again expelled invading Islamic armies. | |||

| In 739, ] begged Charles for his aid against ], but Charles was loath to fight his onetime ally and ignored the plea. Nonetheless, the pope's request for Frankish protection showed how far Charles had come from the days when he was tottering on excommunication, and set the stage for his son and grandson to assert themselves in the peninsula. | |||

| ===Wars from 732-737=== | |||

| Between his victory of 732 and ], Charles reorganised the kingdom of ], replacing the counts and dukes with his loyal supporters, thus strengthening his hold on power. He was forced, by the ventures of ], ] (719-734), son of the Duke Aldegisel who had accepted the missionaries Willibrord and Boniface, to invade independence-minded Frisia again in ]. In that year, he slew the duke, who had expelled the Christian missionaries, in battle and so wholly subjugated the populace (he destroyed every pagan shrine) that the people were peaceful for twenty years after. | |||

| == Death and transition in rule == | |||

| The dynamic changed in 735 because of the death of Odo the Great, who had been forced to acknowledge, albeit reservedly, the suzerainty of Charles in 719. Though Charles wished to unite the duchy directly to himself and went there to elicit the proper homage of the Aquitainians, the nobility proclaimed Odo's son, ], whose dukeship Charles recognised when the Arabs invaded Provence the next year. | |||

| ] | |||

| ].]] | |||

| Charles died on 22 October 741, at ] in what is today the ] '']'' in the ] region of France. He was buried at ] in ].<ref>{{cite web|title=History of the Monument|url=http://www.saint-denis-basilique.fr/en/Explore/History-of-the-monument|website=Basilique Cathédrale de Saint-Denis|access-date=27 January 2017|archive-date=15 June 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200615060407/http://www.saint-denis-basilique.fr/en/Explore/History-of-the-monument|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| This naval Arab invasion was headed by Abdul Rahman's son. It landed in ] in 736 and took ]. Charles, the conflict with Hunold temporarily put on a back burner, descended on the Provençal strongholds of the Muslims. In 736, he retook ] and ], and Arles and ] with the help of ]. ], ], and ], held by Isalm since ], fell to him and their fortresses destroyed. He defeated a mighty host outside of Narbonne, but failed to take the city. Provence, however, he successfully rid of its foreign occupiers. | |||

| His territories had been divided among his adult sons a year earlier: to ] he gave Austrasia, Alemannia, and Thuringia, and to ] Neustria, Burgundy, Provence, and Metz and Trier in the "Mosel duchy". ] was given several lands throughout the kingdom, but at a later date, just before Charles died.<ref name="Riche93">Riche, Pierre (1993) ''The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe,'' , Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, {{ISBN|0-8122-1342-4}}, see , accessed 2 August 2015.</ref>{{rp|50}} | |||

| Notable about these campaigns was Charles' incorporation, for the first time, of heavy cavalry with stirrups to augment his ]. His ability to coordinate infantry and cavalry veterans was unequaled in that era and enabled him to face superior numbers of invaders, and decisively defeat them again and again. Some historians believe Narbonne in particular was as imporant a victory for Christian Europe as Tours. In ''Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels'', ], Professor Emeritus of History at the ], and considered an expert historian in the era in dispute, puts forth an interesting modern opinion on Martel, Tours, and the subsequent campaigns against Rahman's son in 736-737. Santosuosso presents a compelling case that these later defeats of invading Muslim armies were at least as important as Tours in their defence of Western Christendom and the preservation of Western monasticism, the monasteries of which were the centers of learning which ultimately led Europe out of her Dark Ages. He also makes a compelling argument, after studying the Arab histories of the period, that these were clearly armies of invasion, sent by the Caliph not just to avenge Tours, but to conquer Christian Europe and bring it into the Caliphate. Thus, Charles again championed Christianity and halted Muslim expansion into Europe, as the window was closing on Islamic ability to do so. These defeats were the last great attempt at expansion by the Umayyad Caliphate before the destruction of the dynasty at the ], and the rending of the Caliphate forever. | |||

| == |

== Legacy == | ||

| Earlier in his life Charles had many internal opponents and felt the need to appoint his own kingly claimant, ]. Later, however, the dynamics of rulership in Francia had changed, and no hallowed Merovingian ruler was required. Charles divided his realm among his sons without opposition (though he ignored his young son ]). For many historians, Charles laid the foundations for his son Pepin's rise to the Frankish throne in 751, and his grandson Charlemagne's imperial acclamation in 800. However, for Paul Fouracre, while Charles was "the most effective military leader in Francia", his career "finished on a note of unfinished business".<ref>Paul Fouracre, 'Writing about Charles Martel', in ''Law, Laity and Solidarities: essays in honour of Susan Reynolds,'' ed. Pauline Stafford et al. (Manchester, 2001), pp. 12–26.</ref> | |||

| In 737, at the tail end of his campaigning in Provence and ], the king, Theuderic IV, died. Martel, titling himself ''maior domus'' and ''princeps et dux Francorum'', did not appoint a new king and nobody acclaimed one. The throne lay vacant until Martel's death. As the historian ] says (''The Dark Ages'', pg 297), "he cared not for name or style so long as the real power was in his hands." Echoing Oman, ] has said: | |||

| ] | |||

| :''He kept no court, cared not for titles, and the thought of a crown amused him. All that interested him was the true essence of power, and what could be done with it. He believed he had a mission to preserve what his ancestors had struggled so to build after Rome's fall, and intended that it not be destroyed during his stewardship. For a man of such enormous power—the real master of today's Europe at his life's end—he cared naught for show, but only for results.'' | |||

| ===Family and children=== | |||

| The interregnum, the final four years of Charles' life, was more peaceful than most of it had been and much of his time was now spent on administrative and organisational plans to create a more efficient state. Though, in ], he compelled the Saxons of ] to do him homage and pay tribute. Charles set about integrating the outlying realms of his empire into the Frankish church. He erected four diocese in Bavaria (], ], ], and ]) and gave them Boniface as ] and ] over all Germany east of the Rhine, with his seat at ]. In ], ] begged Charles for his aid against Liutprand. But Charles was loathe to fight his onetime ally and ignored the papal pleas. Nonetheless, the Papal applications for Frankish protection showed how far Martel had come from the days he was tottering on excommunication, and set the stage for his son and grandson to literally rearrange Italy to suit the Papacy, and protect it. | |||

| Charles married twice, his first wife being ], daughter either of ], or of ], Count of Treves.{{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} They had the following children: | |||

| ==Death== | |||

| Charles Martel died on ], ], at ] in what is today the ] '']'' in the ] region of France. He was buried at ] in ]. His territories were divided among his adult sons a year earlier: to ] he gave Austrasia and Alemannia (with Bavaria as a vassal), to ] Neustria and Burgundy (with Aquitaine as a vassal), and to ] nothing, though some sources indicate he intended to give him a strip of land between Neustria and Austrasia. | |||

| * ] | |||

| As noted, Gibbon called him "the paramount prince of his age." A strong argument can be made that Gibbon was correct. | |||

| * ]<ref name=Riche93 />{{rp|50}} | |||

| * Landrade, also rendered as Landres {{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| * ], also rendered as Aldana {{Citation needed|date=March 2024}} | |||

| * ]<ref name=Riche93 />{{rp|50}} | |||

| Most of the children married and had issue. ] married ] (]). Landrade was once believed to have married a ] (Count of Hesbania) but Sigrand's wife was more likely the sister of Rotrude. ] married ]. | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| At the beginning of Charles Martel's career, he had many internal opponents and felt the need to appoint his own kingly claimant, Clotaire IV. By his end, however, the dynamics of rulership in Francia had changed, no hallowed Meroving was needed, neither for defence nor legitimacy: Charles divided his realm between his sons without opposition (though he ignored his young son ]. In between, he strengthened the Frankish state by consistently defeating, through superior generalship, the host of hostile foreign nations which beset it on all sides, including the heathen Saxons, which his grandson Charlemagne would fully subdue, and Moors, which he halted on a path of continental domination. | |||

| Charles also married a second time, to ] and they had a child named ].<ref name=Riche93 />{{rp|50}} | |||

| Charles was that rarest of commodities in the Dark Ages: a brilliant stategic general, who also was a tactical commander ''par excellance'', able in the crush and heat of battle to adapt his plans to his foes forces and movement — and amazingly, defeated them repeatedly, especially when, as at Tours, they were far superior in men and weaponry, and at Berre and Narbonne, when they were superior in numbers of brave fighting men. Charles had the last quality which defines genuine greatness in a military commander: he foresaw the dangers of his foes, and prepared for them with care; he used ground, time, place, and fierce loyalty of his troops to offset his foes superior weaponry and tactics; third, he adapted, again and again, to the enemy on the battlefield, cooly shifting to compensate for the unforeseen and unforeseeable. | |||

| With ], with whom he had: | |||

| ===Beginning of the Reconquista=== | |||

| It is vital to note that Martel's victory at Tours, and his later campaigns, prevented invasion of Europe while the unified Caliphate was able to do so. In doing so, Martel probably preserved Christianity and ] as we know it. Although it took another two generations for the Franks to drive all the Arab garrisons out of Septimania and across the Pyrenees, Charles Martel's halt of the invasion of French soil turned the tide of Islamic advances, and the unification of the Frankish kingdoms under Martel, his son Pippin the Younger, and his grandson Charlemagne created a western power which prevented the Emirate of Córdoba from expanding over the Pyrenees. Martel, who in 732 was on the verge of excommunication, instead was recognised by the Church as its paramount defender. ] wrote him more than once, asking his protection and aid , and he remained, till his death, fixated on stopping the Muslims. Martel's son kept his father's promise and returned and took Narbonne by siege in ], and his grandson, Charlamagne, actually established the ''Marca Hispanica'' across the Pyrenees in part of what today is Catalonia, reconquering Girona in ] and Barcelona in ]. This formed a permanent buffer zone against Islam, which became the basis, along with the King of Asturias, named Pelayo (718-737, who started his fight against the Moors in the mountains of ], 722) and his descendants, for the Reconquista until all of the Muslims were expelled from Iberia. | |||

| * ] ({{circa|720}}–787), | |||

| ===Military legacy=== | |||

| * ] ({{circa|722}} – after 782), | |||

| In his vision of what would be necessary for him to withstand a larger force and superior technology (the Muslim horsemen had the ], which made the first ]s possible), he, daring not to send his few horsemen against the Islamic cavalry, trained his army to fight in a formation used by the ]s to withstand superior numbers and weapons by discipline, courage, and a willingness to die for their cause: a phalanx. After using this infantry force by itself at Tours, he studied the foe's forces, and further adapted to them. After 732, he began the integration of heavy cavalry, using the stirrup, and mailed armour, into his army, and trained his infantry to fight in conjunction with cavalry, a tactic which stood him in good stead during his campaigns of 736-7, especially at the Battle of Narbonne. Martel's ability to use what he had, integrate new ideas and technology, earned him his reputation for brilliant generalship in an age generally bereft of same, and was the reason he was undefeated from 716 to his death, against a wide range of opponents, including the Muslim cavalry, at that time the world's best. | |||

| * ] (d. 771) ]. | |||

| == Reputation and historiography == | |||

| The defeats Martel inflicted on the Muslims were absolutely vital in that the split in the Islamic world left the ] unable to mount an all out attack on Europe via its Iberian stronghold after ]. His ability to meet this challenge, until the Muslims self destructed, is of macrohisorical importance, and is why ] writes of him in Heaven as one of the "Defenders of the Faith." The struggle between the ]s and the ]s, which came to a head during this period, left the Arabs unable to mount another massive invasion before they lost the base they needed from which to do it. The door to Europe, the Iberian emirate, was in the hands of the Umayyads, while most of the remainder of the Muslim world came under the control of the Abbasids, making an invasion of Europe a logistical impossibility while the two Muslim empires battled. There was no unified Caliphate to mount an invasion, and no foothold to launch such an invasion from. Instead, al-Andalus (Umayyad Emirate was busy fighting off challenges from the Abbasids in Bagdad to think of invading Europe) and the Abbasid caliphate needed the foothold in Iberia which they lacked. This put off invasion of Europe until the ] conquest of the ] half a millennium later. | |||

| ]'' by ], published in 1553]] | |||

| It is also interesting that the Northmen did not begin their horrific raids until after the death of Martel's grandson, Charlemagne. They had the naval capacity to begin those raids at least three generations earlier, but chose not to challenge Martel, his son Pippin, or his grandson, Charlemagne. This was probably fortunate for Martel, who despite his enormous gifts, would probably not have been able to beat off the Vikings in addition to the Muslims. | |||

| === Military victories === | |||

| ==Family and children== | |||

| Charles Martel married two times: | |||

| #] or Rotrude (]-]), with children: | |||

| ## Hiltrude (d. 754), married ], ]. | |||

| ## ] | |||

| ## Landres of Hesbaye, married ]. | |||

| ## Auda or Alane Martel, married Thierry IV, Count of Autun and Toulouse. | |||

| ## ] | |||

| #], with child: | |||

| ## ] | |||

| ## ] (b. ca. 700) | |||

| For early medieval authors, Charles was famous for his military victories. ] for instance attributed a victory against the ]s actually won by Odo of Aquitaine to Charles.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Age of Charles Martel|last=Fouracre|first=Paul|date=2000|publisher=Longman|isbn=0582064759|location=Harlow, England|page=85|oclc=43634337}}</ref> However, alongside this there soon developed a darker reputation, for his alleged abuse of church property. A ninth-century text, the ''Visio Eucherii'', possibly written by ], portrayed Charles as suffering in ] for this reason.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Merovingian kingdoms, 450–751|last=Wood|first=I. N.|date=1994|publisher=Longman|isbn=0582218780|location=London|oclc=27172340}} pp. 275–276</ref> According to British medieval historian ], this was "the single most important text in the construction of Charles's reputation as a seculariser or despoiler of church lands".<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Age of Charles Martel|last=Fouracre|first=Paul|date=2000|publisher=Longman|isbn=0582064759|location=Harlow, England|page=124|oclc=43634337}}</ref> | |||

| {{s-start}} | |||

| {{s-hou|]||676||741}} | |||

| {{s-bef|before=]}} | |||

| {{s-ttl|title=]|years=]–]}} | |||

| {{s-aft|after=]}} | |||

| {{s-bef|before=]}} | |||

| {{s-ttl|title=]|years=]–]}} | |||

| {{s-aft|after=]}} | |||

| {{end}} | |||

| By the eighteenth century, historians such as ] had begun to portray the Frankish leader as the saviour of Christian Europe from a full-scale Islamic invasion.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ccel.org/g/gibbon/decline/volume2/chap52.htm|title=Chapter 52 of The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire|website=www.ccel.org}}</ref> | |||

| In the nineteenth century, the German historian ] argued that Charles had confiscated church lands in order to fund military reforms that allowed him to defeat the Arab conquests, in this way brilliantly combining two traditions about the ruler. However, Fouracre argued that "...there is not enough evidence to show that there was a decisive change either in the way in which the Franks fought, or in the way in which they organised the resources needed to support their warriors."<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Age of Charles Martel|last=Fouracre|first=Paul|date=2000|publisher=Longman|isbn=0582064759|location=Harlow, England|page=149|oclc=43634337}}</ref> | |||

| Many twentieth-century European historians continued to develop Gibbon's perspectives, such as French medievalist ], who wrote in 1911 that | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| *: A sketch giving the context of the conflict from the Arab point of view. | |||

| *http://www.standin.se/fifteen07a.htm ''Poke's edition of Creasy's 15 Most Important Battles Ever Fought '''ACCORDING TO EDWARD SHEPHERD CREASY Chapter VII. THE BATTLE OF TOURS, A.D. 732.''' | |||

| {{blockquote|"Besides establishing a certain unity in Gaul, Charles saved it from a great peril. In 711 the Arabs had conquered Spain. In 720 they crossed the Pyrenees, seized Narbonensis, a dependency of the kingdom of the Visigoths, and advanced on Gaul. By his able policy Odo succeeded in arresting their progress for some years; but a new vali, ], a member of an extremely fanatical sect, resumed the attack, reached Poitiers, and advanced on Tours, the holy town of Gaul. In October 732—just 100 years after the death of ]—Charles gained a brilliant victory over ], who was called back to Africa by revolts of the Berbers and had to give up the struggle. ...After his victory, Charles took the offensive".<ref name="EB1911"/>|sign=|source=}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| *Watson, William E., , ''Providence: Studies in Western Civilization'', 2 (1993) | |||

| *Poke,, from Sir Edward Creasy, MA, ''Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World From Marathon to Waterloo'' | |||

| *Edward Gibbon, , '']'' | |||

| *Richard Hooker, | |||

| *, from the "]" website: A division of the ]. | |||

| *, from "]" online. | |||

| *Robert W. Martin, , from ] | |||

| *Santosuosso, Anthony, ''Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels'' ISBN 0-8133-9153-9 | |||

| * | |||

| * from the ] | |||

| * | |||

| *Bennett, Bradsbury, Devries, Dickie and Jestice, ''Fighting Tehniques of the Medieval World'' | |||

| Similarly, ], who wrote of the battle's importance in Frankish and world history in 1993, suggested that | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{blockquote|"Had Charles Martel suffered at Tours-Poitiers the fate of King Roderick at the Rio Barbate, it is doubtful that a "do-nothing" sovereign of the Merovingian realm could have later succeeded where his talented major domus had failed. Indeed, as Charles was the progenitor of the Carolingian line of Frankish rulers and grandfather of Charlemagne, one can even say with a degree of certainty that the subsequent history of the West would have proceeded along vastly different currents had 'Abd al-Rahman been victorious at Tours-Poitiers in 732."<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Watson|first=William|date=1993|title=The Battle of Tours-Poitiers Revisited|journal=Providence: Studies in Western Civilization|volume=2}}</ref>|sign=|source=}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| And in 1993, the influential political scientist ] saw the battle of Tours as marking the end of the "Arab and Moorish surge west and north".<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Huntington |first=Samuel P. |date=1993 |title=The Clash of Civilizations? |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/20045621 |journal=Foreign Affairs |volume=72 |issue=3 |pages=22–49 |doi=10.2307/20045621 |jstor=20045621 |issn=0015-7120}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Other recent historians, however, argue that the importance of the battle is dramatically overstated, both for European history in general and for Charles's reign in particular. This view is typified by ], who in 2004 wrote, | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{blockquote|"Today, historians tend to play down the significance of the battle of Poitiers, pointing out that the purpose of the Arab force defeated by Charles Martel was not to conquer the Frankish kingdom, but simply to pillage the wealthy monastery of St-Martin of Tours".<ref>{{Cite book|title=Charlemagne : father of a continent|first=Alessandro|last=Barbero|date=2004|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=0520239431|location=Berkeley|oclc=52773483|page=10}}</ref>|sign=|source=}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Similarly, in 2002 Tomaž Mastnak wrote: | |||

| ] | |||

| {{blockquote|"The continuators of Fredegar's chronicle, who probably wrote in the mid-eighth century, pictured the battle as just one of many military encounters between Christians and Saracens—moreover, as only one in a series of wars fought by Frankish princes for booty and territory... One of Fredegar's continuators presented the battle of Poitiers as what it really was: an episode in the struggle between Christian princes as the Carolingians strove to bring Aquitaine under their rule."<ref>{{Cite book|title=Crusading peace : Christendom, the Muslim world, and Western political order|first=Tomaž|last=Mastnak|date=2002|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=9780520925991|location=Berkeley|oclc=52861403|page= }}</ref>}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| More recently, the memory of Charles has been appropriated by ] and ] groups, such as the ']' in France, and by the perpetrator of the ] at ] and ] in ], New Zealand, in 2019.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/03/18/fake-history-that-fueled-accused-christchurch-shooter/|title=Perspective {{!}} The fake history that fueled the accused Christchurch shooter|newspaper=Washington Post|language=en|access-date=2019-06-04}}</ref> The memory of Charles is a topic of debate in contemporary French politics on both the right and the left.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Blanc |first=William |title=Charles Martel et la Bataille de Poitiers |year=2022 |publisher=Libertalia |isbn=9782377292356}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| === Order of the Genet === | |||

| ] | |||

| In the seventeenth century, a legend emerged that Charles had formed the first regular order of knights in France. In 1620, Andre Favyn stated (without providing a source) that among the spoils Charles's forces captured after the Battle of Tours were many ] (raised for their fur) and several of their pelts.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Favyn |first=Andre |title=Le Theatre d'honneur et de chevalerie |year=1620}}</ref> Charles gave these furs to leaders amongst his army, forming the first order of knighthood, the Order of the Genet. Favyn's claim was then repeated and elaborated in later works in English, for instance by ] in 1672,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Ashmole |first=Elias |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=woFlAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA97 |title=The Institution, Laws and Ceremonies of the Most Noble Order of the Garter |year=1672 |pages=97|publisher=J. Macock }}</ref> and James Coats in 1725.<ref>{{cite book |author=James Coats |title=A New Dictionary of Heraldry |date=1725 |publisher=Jer. Batley |pages=163–164}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| == References == | |||

| ] | |||

| {{reflist|30em}} | |||

| == External links == | |||

| {{commonscat}} | |||

| {{Wikiquote}} | |||

| {{EB9 Poster|Charles Martel}} | |||

| {{NIE Poster|year=1905}} | |||

| * : A sketch giving the context of the conflict from the Arab point of view. | |||

| * | |||

| * —'']'', ] (2014) | |||

| * ({{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141011132606/http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/732tours.html |date=11 October 2014 }}) | |||

| * ({{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141011132606/http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/732tours.html |date=11 October 2014 }}) from the ] | |||

| * ({{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080429225422/http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/g2-martellet.html |date=29 April 2008 }}) | |||

| * {{Cite EB1911|wstitle= Charles Martel |volume= 5 |last= Pfister |first= Christian |author-link= Christian Pfister | pages = 942–943 |short= 1}} | |||

| {{S-start}} | |||

| {{S-hou|] Dynasty||676, 686, 688 or 690||741}} | |||

| {{s-reg}} | |||

| {{S-bef|before=]}} | |||

| {{S-ttl|title=]|years=717–741}} | |||

| {{S-aft|after=]}} | |||

| {{s-break}} | |||

| {{S-bef|before=]}} | |||

| {{S-ttl|title=]|years=717–741}} | |||

| {{S-aft|after=]}} | |||

| {{S-end}} | |||

| {{Carolingians footer}} | |||

| {{Portal bar|Christianity}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] <!--infobox gives various dates--> | |||

Latest revision as of 19:58, 18 December 2024

Frankish military and political leader (c. 688–741) This article is about the Frankish ruler. For other uses, see Charles Martel (disambiguation).

| Charles Martel | |

|---|---|

1839 sculpture of Charles by Jean Baptiste Joseph De Bay père, located in the Palace of Versailles 1839 sculpture of Charles by Jean Baptiste Joseph De Bay père, located in the Palace of Versailles | |

| Duke and Prince of the Franks | |

| Reign | 718 – 22 October 741 |

| Predecessor | Pepin of Herstal |

| Successor | |

| Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia | |

| Reign | 715 – 22 October 741 |

| Predecessor | Theudoald |

| Successor | Carloman |

| Mayor of the Palace of Neustria | |

| Reign | 718 – 22 October 741 |

| Predecessor | Raganfrid |

| Successor | Pepin the Younger |

| Born | 23 August c. 686 or 688 Herstal, Austrasia |

| Died | 22 October 741 (aged 51–53) Quierzy, Frankish Empire |

| Burial | Basilica of St Denis |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Arnulfings Carolingian (founder) |

| Father | Pepin of Herstal |

| Mother | Alpaida |

| Campaigns of Charles Martel | |

|---|---|

Charles Martel (/mɑːrˈtɛl/; c. 688 – 22 October 741), Martel being a sobriquet in Old French for "The Hammer", was a Frankish political and military leader who, as Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, was the de facto ruler of the Franks from 718 until his death. He was a son of the Frankish statesman Pepin of Herstal and a noblewoman named Alpaida. Charles successfully asserted his claims to power as successor to his father as the power behind the throne in Frankish politics. Continuing and building on his father's work, he restored centralized government in Francia and began the series of military campaigns that re-established the Franks as the undisputed masters of all Gaul. According to a near-contemporary source, the Liber Historiae Francorum, Charles was "a warrior who was uncommonly ... effective in battle".

Charles gained a very consequential victory against an Umayyad invasion of Aquitaine at the Battle of Tours, at a time when the Umayyad Caliphate controlled most of the Iberian Peninsula. Alongside his military endeavours, Charles has been traditionally credited with an influential role in the development of the Frankish system of feudalism.

At the end of his reign, Charles divided Francia between his sons, Carloman and Pepin. The latter became the first king of the Carolingian dynasty. Pepin's son Charlemagne, grandson of Charles, extended the Frankish realms and became the first emperor in the West since the Fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Background

Charles, nicknamed "Martel" ("the Hammer") in later chronicles, was a son of Pepin of Herstal and his mistress, possible second wife, Alpaida. He had a brother named Childebrand, who later became the Frankish dux (that is, duke) of Burgundy.And is the great grandson of Arnulf of Metz.

Older historiography commonly describes Charles as "illegitimate", but the dividing line between wives and concubines was not clear-cut in eighth-century Francia. It is likely that the accusation of "illegitimacy" derives from the desire of Pepin's first wife Plectrude to see her progeny as heirs to Pepin's throne.

By Charles's lifetime the Merovingians had ceded power to the Mayors of the Palace, who controlled the royal treasury, dispensed patronage, and granted land and privileges in the name of the figurehead king. Charles's father, Pepin of Herstal, had united the Frankish realm by conquering Neustria and Burgundy. Pepin was the first to call himself Duke and Prince of the Franks, a title later taken up by Charles.

Contesting for power

In December 714, Pepin of Herstal died. A few months before his death and shortly after the murder of his son Grimoald the Younger, he had taken the advice of his wife Plectrude to designate as his sole heir Theudoald, his grandson by their deceased son Grimoald. This was immediately opposed by the Austrasian nobles because Theudoald was a child of only eight years of age. To prevent Charles using this unrest to his own advantage, Plectrude had him imprisoned in Cologne, the city which was intended to be her capital. This prevented an uprising on his behalf in Austrasia, but not in Neustria.

Civil war of 715–718

| Carolingian dynasty |

|---|

|

Pippinids

|

Arnulfings

|

Carolingians

|

After the Treaty of Verdun (843)

|

Pepin's death occasioned open conflict between his heirs and the Neustrian nobles who sought political independence from Austrasian control. In 715, Dagobert III named Raganfrid mayor of the palace. On 26 September 715, Raganfrid's Neustrians met the young Theudoald's forces at the Battle of Compiègne. Theudoald was defeated and fled back to Cologne. Before the end of the year, Charles had escaped from prison and been acclaimed mayor by the nobles of Austrasia. That same year, Dagobert III died and the Neustrians proclaimed Chilperic II, the cloistered son of Childeric II, as king.

Battle of Cologne

Main article: Battle of CologneIn 716, Chilperic and Raganfrid together led an army into Austrasia intent on seizing the Pippinid wealth at Cologne. The Neustrians allied with another invading force under Redbad, King of the Frisians and met Charles in battle near Cologne, which was still held by Plectrude. Charles had little time to gather men or prepare and the result was inevitable. The Frisians held off Charles, while the king and his mayor besieged Plectrude at Cologne, where she bought them off with a substantial portion of Pepin's treasure. After that they withdrew. The Battle of Cologne is the only defeat of Charles's career.

Battle of Amblève

Main article: Battle of AmblèveCharles retreated to the hills of the Eifel to gather and train men. In April 716, he fell upon the triumphant army near Malmedy as it was returning to Neustria. In the ensuing Battle of Amblève, Charles attacked as the enemy rested at midday. According to one source, he split his forces into several groups which fell at them from many sides. Another suggests that while this was his intention, he then decided, given the enemy's unpreparedness, this was not necessary. In any event, the suddenness of the assault led them to believe they were facing a much larger host. Many of the enemy fled and Charles's troops gathered the spoils of the camp. His reputation increased considerably as a result, and he attracted more followers. This battle is often considered by historians as the turning point in Charles's struggle.

Battle of Vincy

Main article: Battle of VincyRichard Gerberding points out that up to this time, much of Charles's support was probably from his mother's kindred in the lands around Liege. After Amblève, he seems to have won the backing of the influential Willibrord, founder of the Abbey of Echternach. The abbey had been built on land donated by Plectrude's mother, Irmina of Oeren, but most of Willibrord's missionary work had been carried out in Frisia. In joining Chilperic and Raganfrid, Radbod of Frisia sacked Utrecht, burning churches and killing many missionaries. Willibrord and his monks were forced to flee to Echternach. Gerberding suggests that Willibrord had decided that the chances of preserving his life's work were better with a successful field commander like Charles than with Plectrude in Cologne. Willibrord subsequently baptized Charles's son Pepin. Gerberding suggests a likely date of Easter 716. Charles also received support from bishop Pepo of Verdun.

Charles took time to rally more men and prepare. By the following spring, he had attracted enough support to invade Neustria. Charles sent an envoy who proposed a cessation of hostilities if Chilperic would recognize his rights as mayor of the palace in Austrasia. The refusal was not unexpected but served to impress upon Charles's forces the unreasonableness of the Neustrians. They met near Cambrai at the Battle of Vincy on 21 March 717. The victorious Charles pursued the fleeing king and mayor to Paris, but as he was not yet prepared to hold the city, he turned back to deal with Plectrude and Cologne. He took the city and dispersed her adherents. Plectrude was allowed to retire to a convent. Theudoald lived to 741 under his uncle's protection.

Consolidation of power

Upon this success, Charles proclaimed Chlothar IV king in Austrasia in opposition to Chilperic and deposed Rigobert, archbishop of Reims, replacing him with Milo, a lifelong supporter.

In 718, Chilperic responded to Charles's new ascendancy by making an alliance with Odo the Great (or Eudes, as he is sometimes known), the duke of Aquitaine, who had become independent during the civil war in 715, but was again defeated, at the Battle of Soissons, by Charles. Chilperic fled with his ducal ally to the land south of the Loire and Raganfrid fled to Angers. Soon Chlotar IV died and Odo surrendered King Chilperic in exchange for Charles recognizing his dukedom. Charles recognized Chilperic as king of the Franks in return for legitimate royal affirmation of his own mayoralty over all the kingdoms.

Wars of 718–732