| Revision as of 19:10, 24 April 2006 view sourceRJII (talk | contribs)25,810 edits →Anarcho-capitalism: sources for many scholars regarding it as anarchism. need more?← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:32, 28 December 2024 view source Tassedethe (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators1,365,479 editsm v2.05 - fix links - Peter Marshall (author)Tag: WPCleaner | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Political philosophy and movement}} | |||

| {{Anarchism}} | |||

| {{Other uses|Anarchy|Anarchism (disambiguation)|Anarchist (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{disputed}} | |||

| {{Pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| '''Anarchism''' is ] the ] '']'' ("without ]s (ruler, chief, king)"). Anarchism as a ], is the belief that all forms of social ], such as governments and social hierarchies are undesireable. <ref>]''The Politics of Individualism'', p. 106</ref> {{dubious}}. Anarchism also refers to related ]s that advocate the elimination of coercive institutions. The word "]", as most anarchists use it, does not imply ], ], or ], but rather a harmonious ] society that is based on individual ] and personal involvement. In place of what are regarded as authoritarian political structures and coercive economic institutions, anarchists advocate social relations based upon ] of free individuals in autonomous communities, ], and ]. | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=August 2021}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2024}} | |||

| {{Use shortened footnotes|date=May 2023}} | |||

| {{Anarchism sidebar}} | |||

| '''Anarchism''' is a ] and ] that is against all forms of authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and ], typically including the ] and ]. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state with ] and voluntary ]. A historically left-wing movement, anarchism is usually described as the ] wing of the ] (]). | |||

| The word ''anarchist'' originated as a term of ]. At the ] (]) during the ], ] remarked "I know that some particular men we debate with believe we are for anarchy" after ] had said "No man says that you have a mind to anarchy, but that the consequence of this rule tends to anarchy, must end in anarchy"<ref>{{cite web|url=http://courses.essex.ac.uk/cs/cs101/putney.htm|title=The Putney debates|accessdate=2004-03-24}}</ref>. The term was later used against ] ]s and '']'' during and following the ]. Whilst the term is still used in a pejorative way to describe ''"any act that used violent means to destroy the organization of society"''<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cas.sc.edu/socy/faculty/deflem/zhistorintpolency.html|title=History of International Police Cooperation|accessdate=2006-03-24|author=Mathieu Deflem|year=2005|work=The Encyclopedia | |||

| of Criminology|publisher=Routledge}}</ref>, it has also been taken up as a positive label by self-defined anarchists. | |||

| Although traces of anarchist ideas are found all throughout history, modern anarchism emerged from the ]. During the latter half of the 19th and the first decades of the 20th century, the anarchist movement flourished in most parts of the world and had a significant role in ] for ]. ] formed during this period. Anarchists have taken part in ], most notably in the ], the ] and the ], whose end marked the end of the ]. In the last decades of the 20th and into the 21st century, the anarchist movement has been resurgent once more, growing in popularity and influence within ], ] and ] movements. | |||

| While anarchism is most easily defined by what it is against, anarchists also offer positive visions of what they believe to be a truly free society. However, ideas about how an anarchist society might work vary considerably, especially with respect to economics; there is also disagreement about how a free society might be brought about. Scholars generally do not consider there to be one monolithic "anarchism"; however a number of anarchists do, and often do not identify or organize more specifically. Beyond the commonality that justifies a wide variety of philosophies as all being forms of anarchism, specific forms of anarchism may overlap in additional respects with other forms and may conflict in some ways as well. Moreover, degrees of commonality and conflict also exist ''within'' each form of anarchism as a result of the unique opinions of those who theorize within the broad genres. | |||

| Anarchists employ ], which may be generally divided into ] and ]; there is significant overlap between the two. Evolutionary methods try to simulate what an anarchist society might be like, but revolutionary tactics, which have historically taken a ] turn, aim to overthrow authority and the state. Many facets of ] have been influenced by anarchist theory, critique, and ]. | |||

| ==Origins and predecessors== | |||

| {{Toc limit|3}} | |||

| In '']'', ] argued that mutual aid was a natural feature of animal and human relations. <ref>], Peter. ''"]"'', 1902.</ref> Most ] agree that the ] is not a natural phenomenon and that many hunter-gatherer bands were egalitarian and lacked ], accumulated wealth, or decreed ], and had equal access to resources.<ref>], Freidrich. ''""'', 1884.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| == Etymology, terminology, and definition == | |||

| Many anarchists cite earlier religious, social, and political movements as inspirational and sometimes as embodying "anarchistic principles" even though they have not proclaimed themselves as anarchist. An example of this is ] from ]<ref>The Anarchy Organization (Toronto). ''Taoism and Anarchy.'' ] ] </ref>, although Taoism became the ] in China in ] C.E.<ref>http://www.imperialtours.net/comparative_history.htm</ref>. According to ] the ] ] "repudiated the ] of the state, its intervention and regimentation, and proclaimed the ] of the moral law of the individual". <ref>, written by Peter Kropotkin, from Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1910]</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Definition of anarchism and libertarianism}} | |||

| {{See also|Glossary of anarchism}} | |||

| ] is an example of a writer who added to anarchist theory without using the exact term.{{Sfn|Carlson|1972|pp=22–23}}]] | |||

| The ] origin of ''anarchism'' is from the ] ''anarkhia'' (ἀναρχία), meaning "without a ruler", composed of the ] ''an-'' ("without") and the word ''arkhos'' ("leader" or "ruler"). The ] '']'' denotes the ideological current that favours anarchy.{{Sfnm|1a1=Bates|1y=2017|1p=128|2a1=Long|2y=2013|2p=217}} ''Anarchism'' appears in English from 1642 as ''anarchisme'' and ''anarchy'' from 1539; early English usages emphasised a sense of disorder.{{Sfnm|1a1=Merriam-Webster|1y=2019|1loc="Anarchism"|2a1=''Oxford English Dictionary''|2y=2005|2loc="Anarchism"|3a1=Sylvan|3y=2007|3p=260}} Various factions within the ] labelled their opponents as ''anarchists'', although few such accused shared many views with later anarchists. Many revolutionaries of the 19th century such as ] (1756–1836) and ] (1808–1871) would contribute to the anarchist doctrines of the next generation but did not use ''anarchist'' or ''anarchism'' in describing themselves or their beliefs.{{Sfn|Joll|1964|pp=27–37}} | |||

| The first ] to call himself an ''anarchist'' ({{Langx|fr|link=no|anarchiste}}) was ] (1809–1865),{{Sfn|Kahn|2000}} marking the formal birth of anarchism in the mid-19th century. Since the 1890s and beginning in France,{{Sfn|Nettlau|1996|p=162}} '']'' has often been used as a synonym for anarchism;{{Sfn|Guérin|1970|loc="The Basic Ideas of Anarchism"}} its use as a synonym is still common outside the United States.{{Sfnm|1a1=Ward|1y=2004|1p=62|2a1=Goodway|2y=2006|2p=4|3a1=Skirda|3y=2002|3p=183|4a1=Fernández|4y=2009|4p=9}} Some usages of ''libertarianism'' refer to ] ] philosophy only, and ] in particular is termed ''libertarian anarchism''.{{Sfn|Morris|2002|p=61}} | |||

| Likewise ], in his '']'', writes that the ]s "repudiated all law, since they held that the good man will be guided at every moment by ]...rom this premise they arrive at ]...."<ref>], Bertrand. ''"Ancient philosophy"'' in ''A History of Western Philosophy, and its connection with political and social circumstances from the earliest times to the present day'', 1945.</ref> ] or "True Levellers" were an early communistic movement during the time of the ], and have been cited as forerunners of modern anarchism.<ref>, from Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1994.</ref> | |||

| While the term ''libertarian'' has been largely synonymous with anarchism,{{Sfnm|1a1=Marshall|1y=1992|1p=641|2a1=Cohn|2y=2009|2p=6}} its meaning has more recently been diluted by wider adoption from ideologically disparate groups,{{Sfn|Marshall|1992|p=641}} including both the ] and ], who do not associate themselves with ] or a ], and extreme ], who are primarily concerned with ].{{Sfn|Marshall|1992|p=641}} Additionally, some anarchists use '']''{{Sfnm|1a1=Marshall|1y=1992|1p=641|2a1=Cohn|2y=2009|2p=6|3a1=Levy|3a2=Adams|3y=2018|3p=104}} to avoid anarchism's negative connotations and emphasise its connections with ].{{Sfn|Marshall|1992|p=641}} ''Anarchism'' is broadly used to describe the ] wing of the ].{{Sfn|Levy|Adams|2018|p=104}}{{Refn|In ''Anarchism: From Theory to Practice'' (1970),{{Sfn|Guérin|1970|p=12}} anarchist historian ] described it as a synonym for ], and wrote that anarchism "is really a synonym for socialism. The anarchist is primarily a socialist whose aim is to abolish the exploitation of man by man. Anarchism is only one of the streams of socialist thought, that stream whose main components are concern for liberty and haste to abolish the State."{{Sfn|Arvidsson|2017}} In his many works on anarchism, historian ] describes anarchism, alongside ], as the ] wing of ].{{Sfn|Otero|1994|p=617}}|group=nb}} Anarchism is contrasted to socialist forms which are ] or from above.{{Sfn|Osgood|1889|p=1}} Scholars of anarchism generally highlight anarchism's socialist credentials{{Sfn|Newman|2005|p=15}} and criticise attempts at creating dichotomies between the two.{{Sfn|Morris|2015|p=64}} Some scholars describe anarchism as having many influences from liberalism,{{Sfn|Marshall|1992|p=641}} and being both liberal and socialist but more so.{{Sfn|Walter|2002|p=44}} Many scholars reject ] as a misunderstanding of anarchist principles.{{Sfnm|1a1=Marshall|1y=1992|1pp=564–565|2a1=Jennings|2y=1993|2p=143|3a1=Gay|3a2=Gay|3y=1999|3p=15|4a1=Morris|4y=2008|4p=13|5a1=Johnson|5y=2008|5p=169|6a1=Franks|6y=2013|6pp=393–394}}{{Refn|] claimed that anarchism is "the extreme antithesis" of ] and ].{{Sfn|Osgood|1889|p=1}} ] states that "n general anarchism is closer to socialism than liberalism. ... Anarchism finds itself largely in the socialist camp, but it also has outriders in liberalism. It cannot be reduced to socialism, and is best seen as a separate and distinctive doctrine."{{Sfn|Marshall|1992|p=641}} According to ], "t is hard not to conclude that these ideas", referring to ], "are described as anarchist only on the basis of a misunderstanding of what anarchism is." Jennings adds that "anarchism does not stand for the untrammelled freedom of the individual (as the 'anarcho-capitalists' appear to believe) but, as we have already seen, for the extension of individuality and community."{{Sfn|Jennings|1999|p=147}} ] wrote that "anarchism does derive from liberalism and socialism both historically and ideologically. ... In a sense, anarchists always remain liberals and socialists, and whenever they reject what is good in either they betray anarchism itself. ... We are liberals but more so, and socialists but more so."{{Sfn|Walter|2002|p=44}} Michael Newman includes anarchism as one of many ], especially the more socialist-aligned tradition following Proudhon and ].{{Sfn|Newman|2005|p=15}} ] argues that it is "conceptually and historically misleading" to "create a dichotomy between socialism and anarchism."{{Sfn|Morris|2015|p=64}}|group=nb}} | |||

| In the ], the first to use the term '''Anarchy''' to mean something other than chaos was ] in his ''Nouveaux voyages dans l'Amérique septentrionale'', (1703), where he described the ] society, which had no state, laws, prisons, priests, or private property, as being in anarchy<ref></ref>. ], a ] and leader in the ], has repeatedly stated that he is "an anarchist, and so are all ancestors." | |||

| While ] is central to anarchist thought, defining ''anarchism'' is not an easy task for scholars, as there is a lot of discussion among scholars and anarchists on the matter, and various currents perceive anarchism slightly differently.{{Sfn|Long|2013|p=217}}{{Refn|One common definition adopted by anarchists is that anarchism is a cluster of political philosophies opposing ] and ], including ], ], the ], and all associated institutions, in the conduct of all ] in favour of a society based on ], ], and ]. Scholars highlight that this definition has the same shortcomings as the definition based on anti-authoritarianism ('']'' conclusion), anti-statism (anarchism is much more than that),{{Sfnm|1a1=McLaughlin|1y=2007|1p=166|2a1=Jun|2y=2009|2p=507|3a1=Franks|3y=2013|3pp=386–388}} and etymology (negation of rulers).{{Sfnm|1a1=McLaughlin|1y=2007|1pp=25–29|2a1=Long|2y=2013|2pp=217}}|group=nb}} Major definitional elements include the will for a non-coercive society, the rejection of the state apparatus, the belief that ] allows humans to exist in or progress toward such a non-coercive society, and a suggestion on how to act to pursue the ideal of anarchy.{{Sfn|McLaughlin|2007|pp=25–26}} | |||

| In 1793, in the thick of the ], ] published ''An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice'' . Although Godwin did not use the word ''anarchism'', many later anarchists have regarded this book as the first major anarchist text, and Godwin as the "founder of philosophical anarchism." But at this point no anarchist movement yet existed, and the term ''anarchiste'' was known mainly as an insult hurled by the ] ] at more radical elements in the ]. | |||

| == History == | |||

| ==The first self-labelled anarchist== | |||

| {{Main|History of anarchism}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main articles|] and ]}} | |||

| === Pre-modern era === | |||

| ] is commonly regarded as the first self-proclaimed anarchist, a label he adopted in his ground breaking work '']'', published in 1840. It is for this reason that some claim Proudhon as the founder of modern anarchist theory. In ] Proudhon answers with the famous accusation "]." In this work he opposed the institution of decreed "property" (propriété), where owners have complete rights to "use and abuse" their property as they wish, such as exploiting workers for profit.<ref name="proudhon-prop">], Pierre-Joseph. ''""'' from ''"]"'', 1840</ref> At first, Proudhon starkly contrasted what he called 'possession' - limited rights to use resources, capital and goods in accordance with principles of equality and justice - with existing forms of 'property.' | |||

| ] ({{Circa|334|262 BC}}), whose '']'' inspired ]{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|p=70}}]] | |||

| The most notable precursors to anarchism in the ancient world were in ] and ]. In China, ] (the discussion on the legitimacy of the state) was delineated by ] philosophers ] and ].{{Sfnm|1a1=Coutinho|1y=2016|2a1=Marshall|2y=1993|2p=54}} Alongside ], Taoism has been said to have had "significant anticipations" of anarchism.{{Sfn|Sylvan|2007|p=257}} | |||

| Anarchic attitudes were also articulated by ] and ] in Greece. ] and ] used the myth of ] to illustrate the conflict between laws imposed by the state and personal ]. ] questioned ] authorities constantly and insisted on the right of individual ]. ] dismissed human law ('']'') and associated authorities while trying to live according to nature ('']''). ] were supportive of a society based on unofficial and friendly relations among its citizens without the presence of a state.{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|pp=4, 66–73}} | |||

| His opposition to capitalism, the state and organised religion inspired subsequent anarchists and made him one of the leading socialist thinkers of his time. For Proudhon: | |||

| In ], there was no anarchistic activity except some ascetic religious movements. These, and other Muslim movements, later gave birth to ]. In the ], ] called for an ] society and the ], only to be soon executed by Emperor ].{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|p=86}} In ], religious sects preached against the state.{{Sfn|Crone|2000|pp=3, 21–25}} In Europe, various religious sects developed anti-state and libertarian tendencies.{{Sfn|Nettlau|1996|p=8}} | |||

| :''"Capital . . . in the political field is analogous to government . . . The economic idea of capitalism, the politics of government or of authority, and the theological idea of the Church are three identical ideas, linked in various ways. To attack one of them is equivalent to attacking all of them . . . What capital does to labour, and the State to liberty, the Church does to the spirit. This trinity of absolutism is as baneful in practice as it is in philosophy. The most effective means for oppressing the people would be simultaneously to enslave its body, its will and its reason."'' <ref>quoted by Max Nettlau, A Short History of Anarchism, pp. 43-44</ref> | |||

| Renewed interest in antiquity during the ] and in private judgment during the ] restored elements of anti-authoritarian ] in Europe, particularly in France.{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|p=108}} ] challenges to intellectual authority (secular and religious) and the ] all spurred the ideological development of what became the era of classical anarchism.{{Sfn|Levy|Adams|2018|p=307}} | |||

| A few years before his death in 1865, when his thinking became dominated by the theory of irreducible "antinomies," he came to support "property" in a more conventional sense "by its aims" - as a source of social stability and independence - without abandoning his earlier critique (as the size of ownership was limited to the amount an individual, family or group could use by themselves). | |||

| === Modern era === | |||

| By then, however, Proudhon had moved away from anarchism, arguing in ''The Principle of Federation'' (1863) that anarchy was to remain a perpetual desideratum. Nevertheless, his ideas still contained anarchistic elements, particularly his notion that social and political relations should be based on genuinely voluntary contracts between free and equal producers. He argued for a federative state, an "agro-industial federation," and for the right of secession. He accepted the need for small-scale property to keep "the State on an even keel" (while property was "an absolutism within an absolutism") and the need to "regulate the market" to "protect the citizens of the federated states from capitalist and financial feudalism, both within them and from the outside." <ref>'''Selected Writings''' and '''The Principle of Federation'''</ref> In his political testament, ''On the Political Capacity of the Working Classes'' (1865), he argued that a federative political organization could only function based on ] economics, which would provide for "the effective sovereignty of the laboring masses" through their mutualist associations | |||

| During the ], partisan groups such as the ] and the {{Lang|fr|]}} saw a turning point in the fermentation of anti-state and federalist sentiments.{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|p=4}} The first anarchist currents developed throughout the 18th century as ] espoused ] ], morally delegitimising the state, ]'s thinking paved the way to ] and ]'s theory of ] found fertile soil ].{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|pp=4–5}} By the late 1870s, various anarchist schools of thought had become well-defined and a wave of then-unprecedented ] occurred from 1880 to 1914.{{Sfn|Levy|2011|pp=10–15}} This era of ] lasted until the end of the ] and is considered the golden age of anarchism.{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|pp=4–5}} | |||

| ] and allied himself with the federalists in the First International before his expulsion by the Marxists.]] | |||

| Proudhon's ] (mutuellisme) involved an exchange economy where individuals and groups could trade the products of their labor using ''labor notes'' which represented the amount of working time involved in production. This would ensure that no one would profit from the labor of others. Workers could freely join together in co-operative workshops. An interest-free bank would be set up to provide everyone with access to the means of production and allow them to manage their own work (i.e. to ensure workers' control of production). Proudhon's ideas were influential within French working class movements, and his followers were active in the ] in France as well as the ] of 1871. Anarcho-communists, such as Kropotkin, later disagreed with Proudhon for his support of "private property" in the products of labour (i.e. wages, or ''"remuneration for work done"'') rather than free distribution of the products of labour.<ref>Kropotkin, Peter. , G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London, 1906.</ref> | |||

| Drawing from mutualism, ] founded ] and entered the ], a class ] ] later known as the ] that formed in 1864 to unite diverse revolutionary currents. The International became a significant political force, with ] being a leading figure and a member of its General Council. Bakunin's faction (the ]) and Proudhon's followers (the mutualists) opposed ], advocating political ] and small property holdings.{{Sfnm|1a1=Dodson|1y=2002|1p=312|2a1=Thomas|2y=1985|2p=187|3a1=Chaliand|3a2=Blin|3y=2007|3p=116}} After bitter disputes, the Bakuninists were expelled from the International by the ] at the ].{{Sfnm|1a1=Graham|1y=2019|1pp=334–336|2a1=Marshall|2y=1993|2p=24}} Anarchists were treated similarly in the ], being ultimately expelled in 1896.{{Sfn|Levy|2011|p=12}} Bakunin predicted that if revolutionaries gained power by Marx's terms, they would end up the ]. In response to their expulsion from the First International, anarchists formed the ]. Under the influence of ], a Russian philosopher and scientist, ] overlapped with ].{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|p=5}} Anarcho-communists, who drew inspiration from the 1871 ], advocated for free federation and for the distribution of goods ].{{Sfn|Graham|2005|p=xii}} | |||

| By the turn of the 20th century, anarchism had spread all over the world.{{Sfn|Moya|2015|p=327}} It was a notable feature of the international ] movement.{{Sfn|Levy|2011|p=16}} In ], small groups of students imported the ] pro-science version of anarcho-communism.{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|pp=519–521}} ] was a hotspot for ] youth from East Asian countries, who moved to the Japanese capital to study.{{Sfnm|1a1=Dirlik|1y=1991|1p=133|2a1=Ramnath|2y=2019|2pp=681–682}} In Latin America, ] was a stronghold for ], where it became the most prominent left-wing ideology.{{Sfnm|1a1=Levy|1y=2011|1p=23|2a1=Laursen|2y=2019|2p=157|3a1=Marshall|3y=1993|3pp=504–508}} During this time, a minority of anarchists adopted tactics of revolutionary ], known as ].{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|pp=633–636}} The dismemberment of the French socialist movement into many groups and the execution and exile of many ] to ] following the suppression of the Paris Commune favoured individualist political expression and acts.{{Sfn|Anderson|2004}} Even though many anarchists distanced themselves from these terrorist acts, infamy came upon the movement and attempts were made to prevent ], including the ], also called the Anarchist Exclusion Act.{{Sfnm|1a1=Marshall|1y=1993|1pp=633–636|2a1=Lutz|2a2=Ulmschneider|2y=2019|2p=46}} ] was another strategy which some anarchists adopted during this period.{{Sfn|Bantman|2019|p=374}} | |||

| As a socialist, Proudhon opposed private property in workplaces, land and housing in favour of a system of "possession" by their users (''"all accumulated capital being social property, no one can be its exclusive proprietor."'' <ref> Chapter 3, section 6 of "What is Property?", p. 130 </ref>). While he opposed communism and favoured remuneration for labour, he also opposed ] (i.e. when capitalists and landlords hire labourers to work for them). <ref>], Pierre-Joseph. ''The General Idea of the Revolution'', p. 281</ref> He urged workers ''"to form themselves into democratic societies, with equal conditions for all members, on pain of a relapse into feudalism."'' Under capitalism, he argued employees are ''"subordinated, exploited"'' and their ''"permanent condition is one of obedience,"'' a ''"slave."'' Capitalist companies ''"plunder the bodies and souls of wage workers"'' and they are ''"an outrage upon human dignity and personality."'' He advocated workers' co-operatives to replace capitalism. The worker becomes an ''"associate"'' and ''"forms a part of the producing organisation . . . forms a part of the sovereign power, of which he was before but the subject."'' Without this, people ''"would remain related as subordinates and superiors, and there would ensue two industrial castes of masters and wage-workers, which is repugnant to a free and democratic society."'' <ref>], Pierre-Joseph. ''The General Idea of the Revolution'', p. 277 and pp. 216-8</ref> Support for workers' management of production is shared by all schools of social anarchism. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Proudhon's philosophy of property is complex: it was developed in a number of works over his lifetime, and there are differing interpretations of some of his ideas. ''For more detailed discussion see ].'' | |||

| Despite concerns, ] enthusiastically participated in the ] in opposition to the ], especially in the ]; however, they met harsh suppression after the ] had stabilised, including during the ].{{Sfn|Avrich|2006|p=204}} Several anarchists from Petrograd and Moscow fled to Ukraine, before the Bolsheviks crushed the ] too.{{Sfn|Avrich|2006|p=204}} With the anarchists being repressed in Russia, two new antithetical currents emerged, namely ] and ]. The former sought to create a coherent group that would push for revolution while the latter were against anything that would resemble a political party. Seeing the victories of the ] in the ] and the resulting ], many workers and activists turned to ], which grew at the expense of anarchism and other socialist movements. In France and the United States, members of major syndicalist movements such as the ] and the ] left their organisations and joined the ].{{Sfn|Nomad|1966|p=88}} | |||

| In the ] of 1936–39, anarchists and syndicalists (] and ]) once again allied themselves with various currents of leftists. A long tradition of ] led to anarchists playing a pivotal role in the war, and particularly in the ]. In response to the army ], an ] of peasants and workers, supported by armed militias, took control of ] and of large areas of rural Spain, where they ] the land.{{Sfn|Bolloten|1984|p=1107}} The ] provided some limited assistance at the beginning of the war, but the result was a bitter fight between communists and other leftists in a series of events known as the ], as ] asserted Soviet control of the ] government, ending in another defeat of anarchists at the hands of the communists.{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|pp=xi, 466}} | |||

| ==Max Stirner's egoism== | |||

| {{main articles|] and ]}} | |||

| ==== Post-WWII ==== | |||

| In his '']'', Stirner argued that most commonly accepted social institutions - including the notion of State, property as a right, natural rights in general, and the very notion of society - were mere illusions or ''ghosts'' in the mind, saying of society that "the individuals are its reality." He advocated egoism and a form of amoralism, in which individuals would unite in 'associations of egoists' only when it was in their self interest to do so. For him, property simply comes about through might: "Whoever knows how to take, to defend, the thing, to him belongs property." And, "What I have in my power, that is my own. So long as I assert myself as holder, I am the proprietor of the thing." | |||

| ] support efforts for workers to form cooperatives is exemplified in this sewing cooperative.]] | |||

| By the end of ], the anarchist movement had been severely weakened.{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|p=xi}} The 1960s witnessed a revival of anarchism, likely caused by a perceived failure of ] and tensions built by the ].{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|p=539}} During this time, anarchism found a presence in other movements critical towards both capitalism and the state such as the ], ], and ]s, the ], and the ].{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|pp=xi, 539}} It also saw a transition from its previous revolutionary nature to provocative ]ism.{{Sfn|Levy|2011|pp=5|p=}} Anarchism became associated with ] as exemplified by bands such as ] and the ].{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|pp=493–494}} The established ] tendencies of ] returned with vigour during the ].{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|pp=556–557}} ] began to take form at this time and influenced anarchism's move from a ] demographic.{{Sfn|Williams|2015|p=680}} This coincided with its failure to gain traction in Northern Europe and its unprecedented height in Latin America.{{Sfn|Harmon|2011|p=70}} | |||

| Around the turn of the 21st century, anarchism grew in popularity and influence within anti-capitalist, ] and ] movements.{{Sfn|Rupert|2006|p=66}} Anarchists became known for their involvement in protests against the ] (WTO), the ] and the ]. During the ]s, ''ad hoc'' ] anonymous cadres known as ]s engaged in rioting, ] and ] confrontations with the police. Other organisational tactics pioneered at this time include ]s, ] and the use of decentralised technologies such as the Internet. A significant event of this period was the confrontations at the ].{{Sfn|Rupert|2006|p=66}} Anarchist ideas have been influential in the development of the ] in ] and the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria, more commonly known as ], a ''de facto'' ] in northern ].{{Sfn|Ramnath|2019|p=691}} | |||

| Stirner never called himself an anarchist - he accepted only the label 'egoist'. Nevertheless, he is considered by most to be an anarchist, and his ideas were influential on many anarchists, although interpretations of his thought are diverse. | |||

| While having revolutionary aspirations, many contemporary forms of anarchism are not confrontational. Instead, they are trying to build an alternative way of ] (following the theories of ]), based on ] and voluntary cooperation. Scholar Carissa Honeywell takes the example of ] group of collectives, to highlight some features of how contemporary anarchist groups work: ], working together and in solidarity with those left behind. While doing so, Food Not Bombs provides ] about the rising rates of world ] and suggest policies to tackle hunger, ranging from ] the ] to addressing ] ] policies and ]s, helping ]s, and resisting the ] of food and housing.{{Sfn|Honeywell|2021|pp=34–44}} Honeywell also emphasizes that contemporary anarchists are interested in the flourishing not only of ]s, but ] and the ] as well.{{Sfn|Honeywell|2021|pp=1–2}} Honeywell argues that their analysis of capitalism and governments results in anarchists ] ] and the state as a whole.{{Sfn|Honeywell|2021|pp=1–3}} | |||

| ==American individualist anarchism== | |||

| {{main articles|] and ]}} | |||

| {{Anchor|Branches}} | |||

| The context of American anarchism can be traced back to the ] and the ], ], and similar local revolts following American independence. ] theory had been used to justify the secession of the American colonies from Britain, and by extension settlers on the Western frontier claimed the right of counties and towns to ] from American states, and for pioneers to live in what was effectively the ]. Although the Whiskey Rebellion was put down by ], ] ultimately did secede from ] during the ], following Virginia's secession into the ]. The movement's economic projects also had colonial roots. The mutual bank was a reinvention of the private land banks and public loan offices of the colonies, a tradition extending back to 1681 and the establishment of "The Fund at Boston." | |||

| == Schools of thought == | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Anarchist schools of thought have been generally grouped into two main historical traditions, ] and ], owing to their different origins, ] and evolution.{{Sfnm|1a1=McLean|1a2=McMillan|1y=2003|1loc="Anarchism"|2a1=Ostergaard|2y=2003|2p=14|2loc="Anarchism"}} The individualist current emphasises ] in opposing restraints upon the free individual, while the social current emphasises ] in aiming to achieve the free potential of society through equality and ].{{Sfn|Harrison|Boyd|2003|p=251}} In a chronological sense, anarchism can be segmented by the classical currents of the late 19th century and the post-classical currents (], ], and ]) developed thereafter.{{Sfn|Levy|Adams|2018|p=9}} | |||

| Beyond the specific factions of anarchist movements which constitute political anarchism lies philosophical anarchism which holds that the state lacks ], without necessarily accepting the imperative of revolution to eliminate it.{{Sfn|Egoumenides|2014|p=2}} A component especially of individualist anarchism,{{Sfnm|1a1=Ostergaard|1y=2003|1p=12|2a1=Gabardi|2y=1986|2pp=300–302}} philosophical anarchism may tolerate the existence of a ] but claims that citizens have no ] to obey government when it conflicts with individual ].{{Sfn|Klosko|2005|p=4}} Anarchism pays significant attention to moral arguments since ethics have a central role in anarchist philosophy.{{Sfn|Franks|2019|p=549}} Anarchism's emphasis on ], ], and for the extension of community and ]ity sets it apart from anarcho-capitalism and other types of ]ism.{{Sfnm|1a1=Marshall|1y=1992|1pp=564–565|2a1=Jennings|2y=1993|2p=143|3a1=Gay|3a2=Gay|3y=1999|3p=15|4a1=Morris|4y=2008|4p=13|5a1=Johnson|5y=2008|5p=169|6a1=Franks|6y=2013|6pp=393–394}} | |||

| In 1825 ] had participated in a ] experiment headed by ] called ], which failed in a few years amidst much internal conflict. Warren blamed the community's failure on a lack of ] and a lack of private property. Warren proceeded to organise experimental anarchist communities which respected what he called "the sovereignty of the individual" at ] and ]. In 1833 Warren wrote and published ''The Peaceful Revolutionist'', which some have noted to be the first anarchist periodical ever published. Benjamin Tucker says that Warren "was the first man to expound and formulate the doctrine now known as Anarchism." (''Liberty'' XIV (December, 1900):1) | |||

| Anarchism is usually placed on the far-left of the political spectrum.{{Sfnm|1a1=Brooks|1y=1994|1p=|1ps=, "Usually considered to be an extreme left-wing ideology".}} Much of its ] and ] reflect ], ], ], and ] interpretations of left-wing and ] politics{{Sfn|Guérin|1970|p=12}} such as ], ], ], ], and ], among other ] economic theories.{{Sfn|Guérin|1970|p=35|loc="Critique of authoritarian socialism"}} As anarchism does not offer a fixed body of ] from a single particular ],{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|pp=14–17}} many anarchist types and traditions exist and varieties of anarchy diverge widely.{{Sfn|Sylvan|2007|p=262}} One reaction against ] within the anarchist milieu was ], a call for ] and unity among anarchists first adopted by ] in 1889 in response to the bitter debates of anarchist theory at the time.{{Sfn|Avrich|1996|p=6}} Belief in political ] has been espoused by anarchists.{{Sfn|Walter|2002|p=52}} Despite separation, the various anarchist schools of thought are not seen as distinct entities but rather as tendencies that intermingle and are connected through a set of shared principles such as autonomy, ], ] and ].{{Sfnm|1a1=Marshall|1y=1993|1pp=1–6|2a1=Angelbeck|2a2=Grier|2y=2012|2p=551}} | |||

| ] became interested in anarchism through meeting Josiah Warren and ]. He edited and published ''Liberty'' from August 1881 to April 1908; it is widely considered to be the finest individualist-anarchist periodical ever issued in the English language. Tucker's conception of individualist anarchism incorporated the ideas of a variety of theorists: Greene's ideas on ]; Warren's ideas on ] (a ] variety of ]); ]'s market anarchism; ]'s ]; and, ]'s "law of equal freedom". Tucker strongly supported the individual's right to own the product of his or her labour as "]", and believed in a <ref name="tucker-pay">], Benjamin. ''""'' Individual Liberty: Selections From the Writings of Benjamin R. Tucker, Vanguard Press, New York, 1926, Kraus Reprint Co., Millwood, NY, 1973.</ref>] for trading this property. However, like most anarchists, he rejected intellectual property rights as well as opposing private property in land and other natural resources in favour of "occupancy and use" He argued that in a truly free market system without the state, the abundance of competition would eliminate profits, interest and rent and ensure that all workers received the full value of their labor. Many individualists (such as Tucker and Yarros) supported market-provided private defense of labour produced property and land occupied by those who used it. | |||

| === Classical === | |||

| Other nineteenth century individualists included ], ], and ]. | |||

| ] is the primary proponent of ] and influenced many future ] and ] thinkers.{{Sfn|Wilbur|2019|pp=216–218}}]] | |||

| Inceptive currents among classical anarchist currents were ] and ]. They were followed by the major currents of social anarchism (], ] and ]). They differ on ] and economic aspects of their ideal society.{{Sfn|Levy|Adams|2018|p=2}} | |||

| Mutualism is an 18th-century economic theory that was developed into anarchist theory by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. Its aims include "abolishing the state",<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |title=The Desk Encyclopedia of World History |publisher=] |date=2006 |isbn=978-0-7394-7809-7 |editor-last=Wright |editor-first=Edmund |location=New York |pages=20–21}}</ref> ], ], voluntary contract, federation and ] of both credit and currency that would be regulated by a bank of the people.{{Sfn|Wilbur|2019|pp=213–218}} Mutualism has been retrospectively characterised as ideologically situated between individualist and collectivist forms of anarchism.{{Sfnm|1a1=Avrich|1y=1996|1p=6|2a1=Miller|2y=1991|2p=11}} In '']'' (1840), Proudhon first characterised his goal as a "third form of society, the synthesis of communism and property."{{Sfn|Pierson|2013|p=187}} Collectivist anarchism is a ] form of anarchism{{Sfn|Morris|1993|p=76}} commonly associated with ].{{Sfn|Shannon|2019|p=101}} Collectivist anarchists advocate ] of the ] which is theorised to be achieved through violent revolution{{Sfn|Avrich|1996|pp=3–4}} and that workers be paid according to time worked, rather than goods being distributed according to need as in communism. Collectivist anarchism arose alongside ] but rejected the ] despite the stated Marxist goal of a collectivist ].{{Sfnm|1a1=Heywood|1y=2017|1pp=146–147|2a1=Bakunin|2y=1990}} | |||

| ==The First International== | |||

| ] ]-]]] | |||

| {{main articles|], ]}} | |||

| Anarcho-communism is a theory of anarchism that advocates a ] with ] of the means of production,{{Sfn|Mayne|1999|p=131}} held by a ] network of ]s,{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|p=327}} with production and consumption based on the guiding principle "]."{{Sfnm|1a1=Marshall|1y=1993|1p=327|2a1=Turcato|2y=2019|2pp=237–238}} Anarcho-communism developed from radical socialist currents after the ]{{Sfn|Graham|2005}} but was first formulated as such in the ] section of the ].{{Sfn|Pernicone|2009|pp=111–113}} It was later expanded upon in the theoretical work of ],{{Sfn|Turcato|2019|pp=239–244}} whose specific style would go onto become the dominating view of anarchists by the late 19th century.{{Sfn|Levy|2011|p=6}} Anarcho-syndicalism is a branch of anarchism that views ]s as a potential force for revolutionary social change, replacing capitalism and the state with a new society democratically self-managed by workers. The basic principles of anarcho-syndicalism are ], workers' ] and ].{{Sfn|Van der Walt|2019|p=249}} | |||

| In Europe, harsh reaction followed the revolutions of 1848. Twenty years later in 1864 the ], sometimes called the 'First International', united some diverse European revolutionary currents, including French followers of ], ], English trade unionists, ] and ]. Due to its genuine links to active workers movements the International became a significant organization. | |||

| Individualist anarchism is a set of several traditions of thought within the anarchist movement that emphasise the ] and their ] over any kinds of external determinants.{{Sfn|Ryley|2019|p=225}} Early influences on individualist forms of anarchism include ], ], and ]. Through many countries, individualist anarchism attracted a small yet diverse following of Bohemian artists and intellectuals{{Sfn|Marshall|1993|p=440}} as well as young anarchist outlaws in what became known as ] and ].{{Sfnm|1a1=Imrie|1y=1994|2a1=Parry|2y=1987|2p=15}} | |||

| ] was a leading figure in the International and a member of its General Council. Proudhon's followers, the ], opposed Marx's ], advocating political abstentionism and small property holdings. ] joined in 1868, allying with the anti-authoritarian socialist sections of the International, who advocated the revolutionary overthrow of the state and the collectivization of property. At first, the ] worked with the Marxists to push the First International into a more revolutionary socialist direction. Subsequently, the International became polarised into two camps, with Marx and Bakunin as their respective figureheads. The clearest difference between the camps was over strategy. The anarchist collectivists around Bakunin favoured (in Kropotkin's words) "direct economic struggle against capitalism, without interfering in the political parliamentary agitation." Marx and his followers focused on parliamentary activity and the need for structured political parties with central leadership and control. | |||

| === Post-classical and contemporary === | |||

| Bakunin characterised Marx's ideas as ], and predicted that if a Marxist party came to power its leaders would simply take the place of the ] they had fought against.<ref>{{cite book|last=Bakunin|first=Mikhail|authorlink=Mikhail Bakunin|origyear=1873|year = 1991|title =Statism and Anarchy | publisher = Cambridge University Press|location = | id = ISBN 0521369738}}</ref> In 1872 the conflict climaxed with a final split between the two groups, when at the ] Marx engineered the expulsion of Bakunin and ] from the International and had its headquarters transferred to New York. In response, the anti-authoritarian sections formed their own International at the ], adopting a revolutionary anarchist program. | |||

| {{Main|Contemporary anarchism}} | |||

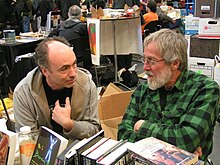

| ] (right) are two prominent contemporary anarchist authors, with Zerzan being a prominent voice within ] and Jarach a notable advocate of ].]] | |||

| Anarchist principles undergird contemporary radical ]s of the left. Interest in the anarchist movement developed alongside momentum in the anti-globalisation movement,{{Sfn|Evren|2011|p=1}} whose leading activist networks were anarchist in orientation.{{Sfn|Evren|2011|p=2}} As the movement shaped 21st century radicalism, wider embrace of anarchist principles signaled a revival of interest.{{Sfn|Evren|2011|p=2}} Anarchism has continued to generate many philosophies and movements, at times eclectic, drawing upon various sources and ] to create new philosophical approaches.{{Sfn|Williams|2007|p=303}} The anti-capitalist tradition of classical anarchism has remained prominent within contemporary currents.{{Sfn|Williams|2018|p=4}} | |||

| Contemporary news coverage which emphasizes ] demonstrations has reinforced anarchism's historical association with chaos and violence. Its publicity has also led more scholars in fields such as ] and ] to engage with the anarchist movement, although contemporary anarchism favours actions over ] theory.{{Sfnm|1a1=Williams|1y=2010|1p=110|2a1=Evren|2y=2011|2p=1|3a1=Angelbeck|3a2=Grier|3y=2012|3p=549}} Various anarchist groups, tendencies, and schools of thought exist today, making it difficult to describe the contemporary anarchist movement.{{Sfn|Franks|2013|pp=385–386}} While theorists and activists have established "relatively stable constellations of anarchist principles", there is no consensus on which principles are core and commentators describe multiple ''anarchisms'', rather than a singular ''anarchism'', in which common principles are shared between schools of anarchism while each group prioritizes those principles differently. ] can be a common principle, although it ranks as a higher priority to anarcha-feminists than anarcho-communists.{{Sfn|Franks|2013|p=386}} | |||

| Many contemporary debates among the Left can be traced back to the debate between Bakunin and Marx over the role of revolutionary parties in the revolution and in post-revolutionary society. Many leftists, communist and anarchist, reject the traditional ] and ] concept of a vanguard party prepared to form a new proletarian state, in part because of the historical failures of the Soviet Union but also out of concern for the development of an aparatchik/bureaucratic class that will replace the existing ruling class with their own bureaucratic dictatorship, although the radical communists do not share the anarchists' opposition to all political power (see a 1992 interview with ], former leader of the militant urban guerilla group Action Directe in France). | |||

| Anarchists are generally committed against coercive authority in all forms, namely "all centralized and ] forms of government (e.g., monarchy, representative democracy, state socialism, etc.), economic class systems (e.g., capitalism, ], ], ], etc.), autocratic religions (e.g., ], ], etc.), ], ], ], and ]."{{Sfn|Jun|2009|pp=507–508}} Anarchist schools disagree on the methods by which these forms should be opposed.{{Sfn|Jun|2009|p=507}} The principle of ] is closer to anarchist political ethics in that it transcends both the liberal and socialist traditions. This entails that liberty and equality cannot be implemented within the state, resulting in the questioning of all forms of domination and hierarchy.{{Sfn|Egoumenides|2014|p=91}} | |||

| ==Anarchist communism== | |||

| {{main|Anarchist communism}} | |||

| ] | |||

| == Tactics == | |||

| Whereas Proudhon disliked the collective aspects of ], Bakunin was originally sympathetic to it, translating the ] into ]. Bakunin was to repudiate communism, however, which he associated with statism, for a form of ]. The collectivist anarchists advocated remuneration for labor but held out the possibility of a post-revolutionary transition to a communist system of distribution according to need. Bakunin's associate, ], put it this way in his essay, '''' (1876): "When… production comes to outstrip consumption… veryone will draw what he needs from the abundant social reserve of commodities, without fear of depletion; and the moral sentiment which will be more highly developed among free and equal workers will prevent, or greatly reduce, abuse and waste." | |||

| Anarchists' tactics take various forms but in general serve two major goals, namely, to first oppose ] and secondly to promote anarchist ethics and reflect an anarchist vision of society, illustrating the ].{{Sfn|Williams|2019|pp=107–108}} A broad categorisation can be made between aims to destroy oppressive states and institutions by revolutionary means on one hand and aims to change society through evolutionary means on the other.{{Sfn|Williams|2018|pp=4–5}} Evolutionary tactics embrace ] and take a gradual approach to anarchist aims, although there is significant overlap between the two.{{Sfn|Kinna|2019|p=125}} | |||

| Anarchist tactics have shifted during the course of the last century. Anarchists during the early 20th century focused more on strikes and militancy while contemporary anarchists use a ].{{Sfn|Williams|2019|p=112}} | |||

| An early anarchist communist was ], the first person to describe himself as "]".<ref> (in ])</ref> Unlike Proudhon, he argued that "it is not the product of his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature." He announced his ideas in his US published journal Le Libertaire (1858-1861). | |||

| === Classical era === | |||

| ], often seen as the most important theorist of anarchist communism, outlined his economic ideas in '']'' and '']''. Kropotkin felt co-operation to be more beneficial than competition, arguing in '']'' that this was illustrated in nature. | |||

| ] is a controversial subject among anarchists as shown by anarchist ] ] ].]] | |||

| He advocated the abolition of private property through the "expropriation of the whole of social wealth" by the people themselves<ref>], Peter. ''Words of a Rebel'', p99.</ref>, and for the economy to be co-ordinated through a horizontal network of voluntary associations<ref>], Peter. '']'', p145.</ref>. He maintained that in anarcho-communism "houses, fields, and factories will no longer be private property, and that they will belong to the commune or the nation" and money, wages, and trade would be abolished.<ref>Kropotkin, Peter. , G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London, 1906.</ref> Individuals and groups would use and control whatever resources they needed as the aim of anarchist-communism was to place "the product reaped or manufactured at the disposal of all, leaving to each the liberty to consume them as he pleases in his own home." <ref>''The Place of Anarchism in the Evolution of Socialist Thought''</ref> Moreover, he repeatedly stressed (like other communist-anarchists) that individuals would not be forced into communism, arguing that the peasant "who is in possession of just the amount of land he can cultivate," the family "inhabiting a house which affords them just enough space… considered necessary for that number of people" and the artisan "working with their own tools or handloom" would be free to live as they saw fit. <ref>''Act for Yourself'', pp. 104-5</ref> Some argue that communist-anarchism is based on the same distinction between possession and property as found in ]'s work. | |||

| During the classical era, anarchists had a militant tendency. Not only did they confront state armed forces, as in Spain and Ukraine, but some of them also employed terrorism as ]. Assassination attempts were carried out against ], some of which were successful. Anarchists also took part in revolutions.{{Sfn|Williams|2019|pp=112–113}} Many anarchists, especially the ], believed that these attempts would be the impetus for a revolution against capitalism and the state.{{Sfn|Norris|2020|pp=7–8}} Many of these attacks were done by individual assailants and the majority took place in the late 1870s, the early 1880s and the 1890s, with some still occurring in the early 1900s.{{Sfnm|1a1=Levy|1y=2011|1p=13|2a1=Nesser|2y=2012|2p=62}} Their decrease in prevalence was the result of further judicial power and of targeting and cataloging by state institutions.{{Sfn|Harmon|2011|p=55}} | |||

| Anarchist perspectives towards violence have always been controversial.{{Sfn|Carter|1978|p=320}} ] advocate for non-violence means to achieve their stateless, nonviolent ends.{{Sfn|Fiala|2017|loc=section 3.1}} Other anarchist groups advocate ], a tactic which can include acts of ] or ]. This attitude was quite prominent a century ago when seeing the state as a ] and some anarchists believing that they had every right to oppose its oppression by any means possible.{{Sfn|Kinna|2019|pp=116–117}} ] and ], who were proponents of limited use of violence, stated that violence is merely a reaction to state violence as a ].{{Sfn|Carter|1978|pp=320–325}} | |||

| Other important anarchist communists include ], ] and ], while ] moved from individualist to communist anarchism. Many in the anarcho-syndicalist movements (see below) saw anarchist communism as their objective. ]'s 1932 '']'' was adopted by the Spanish CNT as its manifesto for a post-revolutionary society. | |||

| Anarchists took an active role in strike actions, although they tended to be antipathetic to formal ], seeing it as ]. They saw it as a part of the movement which sought to overthrow the state and capitalism.{{Sfn|Williams|2019|p=113}} Anarchists also reinforced their propaganda ], some of whom practiced ] and ]. Those anarchists also built communities which were based on friendship and were involved in the news media.{{Sfn|Williams|2019|p=114}} | |||

| Some anarchists disliked merging communism with anarchism. A number of individualist anarchists maintained that abolition of private property was not consistent with liberty. For example, Benjamin Tucker, whilst professing respect for Kropotkin and publishing his work, described communist anarchism as "pseudo-anarchism".<ref name="tucker-pay"/> | |||

| === Revolutionary === | |||

| ==Propaganda of the deed== | |||

| ]"]] | |||

| ] was an outspoken advocate of violence]] | |||

| In the current era, ] ], a proponent of ], has reinstated the debate on violence by rejecting the nonviolence tactic adopted since the late 19th century by Kropotkin and other prominent anarchists afterwards. Both Bonanno and the French group ] advocate for small, informal affiliation groups, where each member is responsible for their own actions but works together to bring down oppression using ] and other violent means against state, capitalism, and other enemies. ] on various charges, terrorism included.{{Sfn|Kinna|2019|pp=134–135}} | |||

| {{main|Propaganda of the deed}} | |||

| Overall, contemporary anarchists are much less violent and militant than their ideological ancestors. They mostly engage in confronting the police during demonstrations and riots, especially in countries such as ], ], and ]. Militant black bloc protest groups are known for clashing with the police;{{Sfn|Williams|2019|p=115}} however, anarchists not only clash with state operators, they also engage in the struggle against ] and ], taking ] action and mobilizing to prevent hate rallies from happening.{{Sfn|Williams|2019|p=117}} | |||

| Anarchists have often been portrayed as dangerous and violent, due mainly to a number of high-profile violent acts, including ]s, ]s, ]s, and ] by some anarchists. Some ]aries of the late 19th century encouraged acts of political violence, such as ]ings and the ]s of ] to further anarchism. Such actions have sometimes been called ']'. However, the term originally referred to exemplary forms of direct action meant to inspire the masses to revolution. Propaganda of the deed may be violent or nonviolent. | |||

| === Evolutionary === | |||

| There is no ] on the legitimacy or utility of violence in general. ] and ], for example, wrote of violence as a necessary and sometimes desirable force in revolutionary settings. But at the same time, they denounced acts of individual terrorism. (Bakunin, "The Program of the International Brotherhood" (1869) and Malatesta, "Violence as a Social Factor" (1895)). | |||

| Anarchists commonly employ ]. This can take the form of disrupting and protesting against unjust hierarchy, or the form of self-managing their lives through the creation of counter-institutions such as ] and non-hierarchical collectives.{{Sfn|Williams|2018|pp=4–5}} Decision-making is often handled in an anti-authoritarian way, with everyone having ], an approach known as ].{{Sfn|Williams|2019|pp=109–117}} Contemporary-era anarchists have been engaging with various ] movements that are more or less based on horizontalism, although not explicitly anarchist, respecting personal autonomy and participating in mass activism such as strikes and demonstrations. In contrast with the "big-A Anarchism" of the classical era, the newly coined term "small-a anarchism" signals their tendency not to base their thoughts and actions on classical-era anarchism or to refer to classical anarchists such as Peter Kropotkin and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon to justify their opinions. Those anarchists would rather base their thought and praxis on their own experience, which they will later theorize.{{Sfn|Kinna|2019|pp=145–149}} | |||

| The concept of ] is enacted by many contemporary anarchist groups, striving to embody the principles, organization and tactics of the changed social structure they hope to bring about. As part of this the decision-making process of small anarchist affinity groups plays a significant tactical role.{{Sfn|Williams|2019|pp=109, 119}} Anarchists have employed various methods to build a rough consensus among members of their group without the need of a leader or a leading group. One way is for an individual from the group to play the role of ] to help achieve a ] without taking part in the discussion themselves or promoting a specific point. Minorities usually accept rough consensus, except when they feel the proposal contradicts anarchist ethics, goals and values. Anarchists usually form small groups (5–20 individuals) to enhance autonomy and friendships among their members. These kinds of groups more often than not interconnect with each other, forming larger networks. Anarchists still support and participate in strikes, especially ] as these are leaderless strikes not organised centrally by a syndicate.{{Sfn|Williams|2019|pp=119–121}} | |||

| Other anarchists, sometimes identified as ], advocated complete ]. ], whose philosophy is often viewed as a form of ] ''(see below)'', was a notable exponent of ]. | |||

| As in the past, newspapers and journals are used, and anarchists have gone online to spread their message. Anarchists have found it easier to create websites because of distributional and other difficulties, hosting electronic libraries and other portals.{{Sfn|Williams|2019|pp=118–119}} Anarchists were also involved in developing various software that are available for free. The way these ] work to develop and distribute resembles the anarchist ideals, especially when it comes to preserving users' privacy from ].{{Sfn|Williams|2019|pp=120–121}} | |||

| ==Anarchism in the labour movement== | |||

| {{seealso|Anarcho-syndicalism}} | |||

| Anarchists organize themselves to ] and reclaim ]s. During important events such as protests and when spaces are being occupied, they are often called ]s (TAZ), spaces where art, poetry, and ] are blended to display the anarchist ideal.{{Sfnm|1a1=Kinna|1y=2019|1p=139|2a1=Mattern|2y=2019|2p=596|3a1=Williams|3y=2018|3pp=5–6}} As seen by anarchists, ] is a way to regain urban space from the capitalist market, serving pragmatical needs and also being an exemplary direct action.{{Sfnm|1a1=Kinna|1y=2012|1p=250|2a1=Williams|2y=2019|2p=119}} Acquiring space enables anarchists to experiment with their ideas and build social bonds.{{Sfn|Williams|2019|p=122}} Adding up these tactics while having in mind that not all anarchists share the same attitudes towards them, along with various forms of protesting at highly symbolic events, make up a ] atmosphere that is part of contemporary anarchist vividity.{{Sfn|Morland|2004|pp=37–38}} | |||

| ] is anarchism focusing on the labor movement ("syndicalism" being derived from the French ''syndicalisme'', meaning "trade unionism"). Anarcho-syndicalists view labour unions as a potential force for revolutionary social change, replacing capitalism and the State with a society self-managed by workers. Anarcho-syndicalists seek to abolish the wage system and private ownership of the means of production, which they believe lead to class division. | |||

| == Key issues == | |||

| After the ] French anarchism reemerged, influencing the ''Bourses de Travails'' of autonomous workers groups and trade unions. From this movement the ] (General Confederation of Labour, CGT) was formed in 1895 as the first major anarcho-syndicalist movement. ] and ]'s writing for the CGT saw ] developing from a ]. After 1914 the CGT moved away from anarcho-syndicalism due to the appeal of ]. French-style syndicalism was a significant movement in Europe prior to 1921, and remained a significant movement in Spain until the mid 1940s.] | |||

| Spanish anarchist trade union federations were formed in the 1870's, 1900 and 1910. The most successful was the ] (National Confederation of Labour: CNT), founded in 1910. Prior to the 1940s the CNT was the major force in Spanish working class politics. With a membership of 1.58 million in 1934, the CNT played a major role in the ]. ''See also:'' ]. | |||

| <!-- In the interest of restricting article length, these overview summaries are meant to be brief. Thank you. --> | |||

| Syndicalists like ] were key figures in the ]. ]n anarchism was strongly influenced, extending to the ] rebellion and the ] in Argentina. In Berlin in 1922 the CNT was joined with the ], an anarcho-syndicalist successor to the ]. | |||

| As anarchism is a philosophy that embodies many diverse attitudes, tendencies, and schools of thought, disagreement over questions of values, ideology, and ] is common. Its diversity has led to widely different uses of identical terms among different anarchist traditions which has created a number of ]. The compatibility of ],{{Sfnm|1a1=Marshall|1y=1993|1p=565|2a1=Honderich|2y=1995|2p=31|3a1=Meltzer|3y=2000|3p=50|4a1=Goodway|4y=2006|4p=4|5a1=Newman|5y=2010|5p=53}} ], and ] with anarchism is widely disputed, and anarchism enjoys complex relationships with ideologies such as communism, ], Marxism, and ]. Anarchists may be motivated by ], ], ], ], or any number of alternative ethical doctrines. Phenomena such as ], technology (e.g. within anarcho-primitivism), and the ] may be sharply criticised within some anarchist tendencies and simultaneously lauded in others.{{Sfn|De George|2005|pp=31–32}} | |||

| === The state === | |||

| The largest organised anarchist movement today is in Spain, in the form of the ] (CGT) and the ]. The CGT claims a paid-up membership of 60,000, and received over a million votes in Spanish ] elections. Other active syndicalist movements include the US ], and the UK ]. The revolutionary industrial unionist ] also exists, claiming 2,000 paid members. | |||

| <!-- Important! Strive to explain how anarchists perceive authority and oppression and why they reject them. Jun (2019), p. 41. -->] opposing state-waged war]] | |||

| Objection to the ] and its institutions is a '']'' of anarchism.{{Sfnm|1a1=Carter|1y=1971|1p=14|2a1=Jun|2y=2019|2pp=29–30}} Anarchists consider the state as a tool of domination and believe it to be illegitimate regardless of its political tendencies. Instead of people being able to control the aspects of their life, major decisions are taken by a small elite. Authority ultimately rests solely on power, regardless of whether that power is ] or ], as it still has the ability to coerce people. Another anarchist argument against states is that the people constituting a government, even the most altruistic among officials, will unavoidably seek to gain more power, leading to corruption. Anarchists consider the idea that the state is the collective will of the people to be an unachievable fiction due to the fact that the ] is distinct from the rest of society.{{Sfn|Jun|2019|pp=32–38}} | |||

| Specific anarchist attitudes towards the state vary. ] believed that the tension between authority and autonomy would mean the state could never be legitimate. Bakunin saw the state as meaning "coercion, domination by means of coercion, camouflaged if possible but unceremonious and overt if need be." ] and ], who leaned toward philosophical anarchism, believed that the state could be legitimate if it is governed by consensus, although they saw this as highly unlikely.{{Sfnm|1a1=Wendt|1y=2020|1p=2|2a1=Ashwood|2y=2018|2p=727}} Beliefs on how to abolish the state also differ.{{Sfn|Ashwood|2018|p=735}} | |||

| Contemporary critics of anarcho-syndicalism and revolutionary industrial unionism claim that they are ] and fail to deal with economic life outside work. Post-leftist critics such as ] claim anarcho-syndicalism advocates oppressive social structures, such as ], ], and compulsory membership in ]s, which violates the concept of individual autonomy by denying the ]. | |||

| === Gender, sexuality, and free love === | |||

| ==The Russian Revolution== | |||

| {{Main|Anarchism and issues related to love and sex}} | |||

| {{main|Russian Revolution of 1917}} | |||

| As ] and ] carry along them dynamics of hierarchy, many anarchists address, analyse, and oppose the suppression of one's autonomy imposed by gender roles.{{Sfn|Nicholas|2019|p=603}} | |||

| ] protests, symbols, and flags]] | |||

| The ] was a seismic event in the development of anarchism as a movement and as a philosophy. | |||

| Sexuality was not often discussed by classical anarchists but the few that did felt that an anarchist society would lead to sexuality naturally developing.{{Sfn|Lucy|2020|p=162}} Sexual violence was a concern for anarchists such as ], who opposed ], believing they would benefit predatory men.{{Sfn|Lucy|2020|p=178}} A historical current that arose and flourished during 1890 and 1920 within anarchism was ]. In contemporary anarchism, this current survives as a tendency to support ], ], and ].{{Sfnm|1a1=Nicholas|1y=2019|1p=611|2a1=Jeppesen|2a2=Nazar|2y=2012|2pp=175–176}} Free love advocates were against marriage, which they saw as a way of men imposing authority over women, largely because marriage law greatly favoured the power of men. The notion of free love was much broader and included a critique of the established order that limited women's sexual freedom and pleasure.{{Sfn|Jeppesen|Nazar|2012|pp=175–176}} Those free love movements contributed to the establishment of communal houses, where large groups of travelers, anarchists and other activists slept in beds together.{{Sfn|Jeppesen|Nazar|2012|p=177}} Free love had roots both in Europe and the United States; however, some anarchists struggled with the jealousy that arose from free love.{{Sfn|Jeppesen|Nazar|2012|pp=175–177}} Anarchist feminists were advocates of free love, against marriage, and ] (using a contemporary term), and had a similar agenda. Anarchist and non-anarchist feminists differed on ] but were supportive of one another.{{Sfn|Kinna|2019|pp=166–167}} | |||

| During the second half of the 20th century, anarchism intermingled with the ], radicalising some currents of the feminist movement and being influenced as well. By the latest decades of the 20th century, anarchists and feminists were advocating for the rights and autonomy of women, gays, queers and other marginalised groups, with some feminist thinkers suggesting a fusion of the two currents.{{Sfn|Nicholas|2019|pp=609–611}} With the ], sexual identity and ] became a subject of study for anarchists, yielding a ] critique of ].{{Sfn|Nicholas|2019|pp=610–611}} Some anarchists distanced themselves from this line of thinking, suggesting that it leaned towards an individualism that was dropping the cause of social liberation.{{Sfn|Nicholas|2019|pp=616–617}} | |||

| Anarchists participated alongside the ] in both February and October revolutions, many anarchists initially supporting the Bolshevik coup. However the Bolsheviks soon turned against the anarchists and other left-wing opposition, a conflict which culminated in the 1921 ]. Anarchists in central Russia were imprisoned or driven underground, or joined the victorious Bolsheviks. In ] anarchists fought in the ] against both Whites and Bolsheviks within the Makhnovshchina peasant army led by ]. | |||

| === Education === | |||

| Expelled American anarchists ] and ] before leaving Russia were amongst those agitating in response to Bolshevik policy and the suppression of the Kronstadt uprising. Both wrote classic accounts of their experiences in Russia, aiming to expose the reality of Bolshevik control. For them, ]'s predictions about the consequences of Marxist rule had proved all too true. | |||

| {{Main|Anarchism and education}} | |||

| {|class="wikitable" style="border: none; float: right;" | |||

| |+ Anarchist vs. statist perspectives on education<br/>{{Small|Ruth Kinna (2019){{Sfn|Kinna|2019|p=97}}}} | |||

| |- | |||

| !scope="col"| | |||

| !scope="col"|Anarchist education | |||

| !scope="col"|State education | |||

| |- | |||

| |Concept || Education as self-mastery || Education as service | |||

| |- | |||

| |Management || Community based || State run | |||

| |- | |||

| |Methods || Practice-based learning || Vocational training | |||

| |- | |||

| |Aims || Being a critical member of society || Being a productive member of society | |||

| |} | |||

| The interest of anarchists in education stretches back to the first emergence of classical anarchism. Anarchists consider proper education, one which sets the foundations of the future autonomy of the individual and the society, to be an act of ].{{Sfnm|1a1=Kinna|1y=2019|1pp=83–85|2a2=Suissa|2y=2019|2pp=514–515, 520}} Anarchist writers such as William Godwin ('']'') and Max Stirner ("]") attacked both ] and private education as another means by which the ruling class replicate their privileges.{{Sfnm|1a1=Suissa|1y=2019|1pp=514, 521|2a1=Kinna|2y=2019|2pp=83–86|3a1=Marshall|3y=1993|3p=222}} | |||

| In 1901, ] anarchist and free thinker ] established the ] in Barcelona as an opposition to the established education system which was dictated largely by the Catholic Church.{{Sfn|Suissa|2019|pp=511–512}} Ferrer's approach was secular, rejecting both state and church involvement in the educational process while giving pupils large amounts of autonomy in planning their work and attendance. Ferrer aimed to educate the working class and explicitly sought to foster ] among students. The school closed after constant harassment by the state and Ferrer was later arrested. Nonetheless, his ideas formed the inspiration for a series of ] around the world.{{Sfn|Suissa|2019|pp=511–514}} ] ], who published the essay ''Education and Culture'', also established a similar school with its founding principle being that "for education to be effective it had to be free."{{Sfn|Suissa|2019|pp=517–518}} In a similar token, ] founded what became the ] in 1921, also declaring being free from coercion.{{Sfn|Suissa|2019|pp=518–519}} | |||

| The victory of the Bolsheviks in the October Revolution and the resulting Russian Civil War did serious damage to anarchist movements internationally. Many workers and activists saw Bolshevik success as setting an example; Communist parties grew at the expense of anarchism and other socialist movements. In France and the US for example, the major syndicalist movements of the ] and ] began to realign themselves away from anarchism and towards the ]. | |||

| Anarchist education is based largely on the idea that a child's right to develop freely and without manipulation ought to be respected and that rationality would lead children to morally good conclusions; however, there has been little consensus among anarchist figures as to what constitutes ]. Ferrer believed that moral indoctrination was necessary and explicitly taught pupils that equality, liberty and ] were not possible under capitalism, along with other critiques of government and nationalism.{{Sfnm|1a1=Avrich|1y=1980|1pp=3–33|2a1=Suissa|2y=2019|2pp=519–522}} | |||

| In Paris, the ] group of Russian anarchist exiles which included ] concluded that anarchists needed to develop new forms of organisation in response to the structures of Bolshevism. Their 1926 manifesto, known as the ], was supported by some communist anarchists, though opposed by many others. | |||

| Late 20th century and contemporary anarchist writers (], ], and ]) intensified and expanded the anarchist critique of ], largely focusing on the need for a system that focuses on children's creativity rather than on their ability to attain a career or participate in ] as part of a consumer society.{{Sfn|Kinna|2019|pp=89–96}} Contemporary anarchists such as Ward claim that state education serves to perpetuate ].{{Sfn|Ward|1973|pp=39–48}} | |||

| The ''Platform'' continues to inspire some contemporary anarchist groups who believe in an anarchist movement organised around its principles of 'theoretical unity', 'tactical unity', 'collective responsibility' and 'federalism'. Platformist groups today include the ] in Ireland, the UK's ], and the ] in the northeastern United States and bordering Canada and Québec. | |||

| While few anarchist education institutions have survived to the modern-day, major tenets of anarchist schools, among them respect for ] and relying on reasoning rather than indoctrination as a teaching method, have spread among mainstream educational institutions. Judith Suissa names three schools as explicitly anarchists' schools, namely the Free Skool Santa Cruz in the United States which is part of a wider American-Canadian network of schools, the Self-Managed Learning College in ], and the Paideia School in Spain.{{Sfn|Suissa|2019|pp=523–526}} | |||

| ==The fight against fascism== | |||

| ], ]. Members of the ] construct ]s to fight against the ]s in one of the ] factories.]] | |||

| {{main articles|] and ]}} | |||

| In the 1920s and 1930s the familiar dynamics of anarchism's conflict with the state were transformed by the rise of ] in Europe. In many cases, European anarchists faced difficult choices - should they join in ]s with reformist democrats and Soviet-led ] against a common fascist enemy Luigi Fabbri, an exile from Italian fascism, was amongst those arguing that fascism was something different: | |||

| === The arts === | |||

| :"Fascism is not just another form of government which, like all others, uses violence. It is the most authoritarian and the most violent form of government imaginable. It represents the utmost glorification of the theory and practice of the principle of authority." | |||

| {{Main|Anarchism and the arts}} | |||

| ] is a notable example of blending anarchism and the arts.{{Sfn|Antliff|1998|p=99}}]] | |||

| The connection between anarchism and art was quite profound during the classical era of anarchism, especially among artistic currents that were developing during that era such as futurists, surrealists and others.{{Sfn|Mattern|2019|p=592}} In literature, anarchism was mostly associated with the ] and the ] movement.{{Sfn|Gifford|2019|p=577}} In music, anarchism has been associated with music scenes such as ].{{Sfnm|1a1=Marshall|1y=1993|1pp=493–494|2a1=Dunn|2y=2012|3a1=Evren|3a2=Kinna|3a3=Rouselle|3y=2013|p=138}} Anarchists such as ] and ] stated that the border between the artist and the non-artist, what separates art from a daily act, is a construct produced by the alienation caused by capitalism and it prevents humans from living a joyful life.{{Sfn|Mattern|2019|pp=592–593}} | |||

| Other anarchists advocated for or used art as a means to achieve anarchist ends.{{Sfn|Mattern|2019|p=593}} In his book ''Breaking the Spell: A History of Anarchist Filmmakers, Videotape Guerrillas, and Digital Ninjas'', Chris Robé claims that "anarchist-inflected practices have increasingly structured movement-based video activism."{{Sfn|Robé|2017|p=44}} Throughout the 20th century, many prominent anarchists (], ], ] and ]) and publications such as '']'' wrote about matters pertaining to the arts.{{Sfn|Miller|Dirlik|Rosemont|Augustyn|2019|p=1}} | |||

| Italy saw the first struggles between anarchists and fascists. Anarchists played a key role in the anti-fascist organisation '''Arditi del Popolo.''' This group was strongest in areas with anarchist traditions and marked up numerous successful victories, including the total humiliation of thousands of Blackshirts in the anarchist stronghold of Parma in August 1922. Unfortunately, anarchist calls for a united front against fascism were ignored by the socialists and communists until it was too late. <ref></ref> In France, where the fascists came close to insurrection in the February 1934 riots, anarchists divided over a 'united front' policy. In Spain, the ] initially refused to join a popular front electoral alliance, and abstention by CNT supporters led to a right wing election victory. But in 1936, the CNT changed its policy and anarchist votes helped bring the popular front back to power. Months later, the ruling class responded with an attempted coup, and the ] (1936-39) was underway. | |||

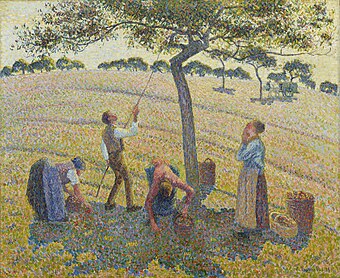

| Three overlapping properties made art useful to anarchists. It could depict a critique of existing society and hierarchies, serve as a prefigurative tool to reflect the anarchist ideal society and even turn into a means of direct action such as in protests. As it appeals to both emotion and reason, art could appeal to the whole human and have a powerful effect.{{Sfn|Mattern|2019|pp=593–596}} The 19th-century ] movement had an ecological aesthetic and offered an example of an anarchist perception of the road towards socialism.{{Sfn|Antliff|1998|p=78}} In ''Les chataigniers a Osny'' by anarchist painter ], the blending of aesthetic and social harmony is prefiguring an ideal anarchistic agrarian community.{{Sfn|Antliff|1998|p=99}} | |||

| In response to the army rebellion ] movement of peasants and workers, supported by armed militias, took control of the major ] of ] and of large areas of rural Spain where they ] the land. But even before the eventual fascist victory in 1939, the anarchists were losing ground in a bitter struggle with the ]. The CNT leadership often appeared confused and divided, with some members controversially entering the government. Stalinist-led troops suppressed the collectives, and persecuted both ] and anarchists. | |||

| == Criticism == | |||

| Since the late 1970s anarchists have been involved in fighting the rise of ] groups. In Germany and the United Kingdom some anarchists worked within ] ] groups alongside members of the ] left. They advocated directly combating fascists with physical force rather than relying on the state. Since the late 1990s, a similar tendency has developed within US anarchism. ''See also: ] (US), ] (UK/Europe), ]'' | |||

| The most common critique of anarchism is the assertion that humans cannot ] and so a state is necessary for human survival. Philosopher ] supported this critique, stating that "eace and war, ]s, regulations of ] conditions and the sale of noxious ]s, the preservation of a just system of distribution: these, among others, are functions which could hardly be performed in a community in which there was no central government."{{Sfn|Krimerman|Perry|1966|p=494}} Another common criticism of anarchism is that it fits a world of ] in which only the small enough entities can be self-governing; a response would be that major anarchist thinkers advocated anarchist federalism.{{Sfn|Ward|2004|p=78}} | |||