| Revision as of 19:08, 1 September 2013 editScoobydunk (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,480 edits Corrections regarding Johnson being the first slave owner in what would become mainland AmericaTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:54, 25 December 2024 edit undoSteveprutz (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers21,644 editsm →Later life: ref fixTag: 2017 wikitext editor | ||

| (853 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Indentured servant, farmer, enslaver (1600–1670)}} | |||

| {{other people|Anthony Johnson}} | {{other people|Anthony Johnson}} | ||

| {{Infobox person | {{Infobox person | ||

| |name=Anthony Johnson | | name = Anthony Johnson | ||

| | image = | |||

| |birth_name= | |||

| | alt = | |||

| |birth_date= | |||

| | caption = | |||

| |birth_place=] | |||

| | birth_name = unknown | |||

| |death_date=1670 | |||

| | birth_date = {{circa|1600}} | |||

| |death_place=] | |||

| | birth_place = ] | |||

| |occupation=Farmer | |||

| | death_date = {{death year|1670}} (aged 69–70) | |||

| |known_for = The first slaveowner in the mainland Thirteen Colonies | |||

| | death_place = ] | |||

| | nationality = | |||

| | other_names = António or | |||

| Antonio | |||

| | occupation = Farmer | |||

| | known_for = An African man indentured in Maryland who amassed sizable landholding and had indentured servants and enslaved people in the 1600s. | |||

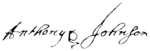

| | signature = Anthony Johnson Clerical Signature.png | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Anthony Johnson''' was a black ]n held as an ] by a merchant in the ] in 1620, but later freed to become a successful hemp farmer and property owner. Some mistakenly claim he was the first man to be a slave owner in 1654 in what would eventually become mainland America. This is untrue because Massachusetts legalized slavery in 1641<ref>http://www.pbs.org/wnet/slavery/timeline/1641.html</ref>, Connecticut legalized slavery in 1650<ref>http://www.pbs.org/wnet/slavery/timeline/1641.html</ref>, and Hugh Gwyn actually became the first lifelong slave owner in Virginia when the court granted him John Punch as a slave for life in 1640<ref>http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part1/1p262.html</ref>. Upon his death in 1670, his property was taken because a jury ruled that Anthony Johnson,as a black man, was an alien and his land should be returned to England<ref>http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part1/1h314t.html</ref>. | |||

| '''Anthony Johnson''' ({{born in|{{circa|1600}}}} – {{died in|1670}}) was an Angolan-born man who achieved wealth in the early 17th-century ]. Held as an ] in 1621, he earned his freedom after several years and was granted land by the colony.<ref name="Foner 1980"/> | |||

| He later became a ] farmer in Maryland. He attained great wealth after completing his term as an indentured servant and has been referred to as "'the black patriarch' of the first community of Negro property owners in America".<ref name="Foner 1980">{{Cite book|title=History of Black Americans: From Africa to the Emergence of the Cotton Kingdom |first=Philip S. |last=Foner |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1980 |url=http://testaae.greenwood.com/doc_print.aspx?fileID=GR7529&chapterID=GR7529-747&path=books/greenwood |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131014135617/http://testaae.greenwood.com/doc_print.aspx?fileID=GR7529&chapterID=GR7529-747&path=books%2Fgreenwood |archive-date=2013-10-14 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| ===Early life=== | ===Early life=== | ||

| In the early 1620s, African slave traders kidnapped the man who would later be known as Anthony Johnson in ] and sold him to Portuguese slavers, who named him António and sold him into the ]. A colonist in Virginia acquired António. As an indentured servant, António worked for a merchant at the ].<ref>Horton (2002), p. 29.</ref> He was also received into the Roman Catholic Church.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Pender|first=Alicia|date=2021-03-13|title=Catholics who care about US Black history must read 'Four Hundred Souls'|url=https://www.ncronline.org/news/opinion/catholics-who-care-about-us-black-history-must-read-four-hundred-souls|access-date=2021-03-13|website=National Catholic Reporter|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Johnson was captured by Arab traders in his native Angola by an enemy tribe and sold as a slave to a merchant working for the ].<ref>Horton 2002, p. 29.</ref> He arrived in Virginia in 1621 aboard the ''James''. At this time he was known in the records as "Antonio, a Negro".<ref>Breen1980, p. 8.</ref> Johnson was later sold to a white planter named Bennet to work on his Virginia tobacco farm as an ]. Servants typically worked four to seven years in exchange for passage, room, board, lodging and freedom dues. | |||

| ===Servitude in Virginia=== | |||

| He almost lost his life in the ] when his master's farm was attacked. The Powhatans, who were native to Virginia, were upset at the advance of the tobacco planters into their land and planned an attack on Good Friday. Of the fifty-seven men on the farm where Johnson worked, fifty-two died during the attack. In 1622, 30 Native Americans attacked Jamestown to avenge the death of one of their leaders. | |||

| He sailed to Virginia in 1621 aboard the ''James.'' The Virginia Muster (census) of 1624 lists his name as "Antonio not given," recorded as "a Negro" in the "notes" column.<ref>Breen 1980, p. 8.</ref> Historians dispute whether this was the same António later known as Anthony Johnson, as the census lists several men named "Antonio". This one is considered the most likely.<ref name="Walsh">{{cite book | last = Walsh | first = Lorena | year = 2010 | title = Motives of Honor, Pleasure, and Profit: Plantation Management in the Colonial Chesapeake, 1607–1763 | publisher = UNC Press | page=115 | isbn = 978-0807832349 }}</ref> | |||

| Johnson was sold as an "]" to merchant ] to work on his Virginia tobacco farm, Warrosquoake, on the southern bank of the James River.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=2677|title=Bennett’s Plantation Historical Marker|website=www.hmdb.org}}</ref> Slave laws were not passed until 1661 in Virginia; before that date, Africans were not officially considered to be enslaved.<ref>, pbs.org. Accessed March 9, 2023.</ref> | |||

| The following year (1623) "Mary, a Negro" arrived aboard the ship ''Margaret'' and was brought in to work on the plantation, where she was the only woman. They were married and lived together for over forty years.<ref name="Breen10">Breen 1980, p. 10.</ref> | |||

| Such workers typically worked under a limited indenture contract for four to seven years to pay off their passage, room, board, lodging, and freedom dues. In the early colonial years, most Africans in the ] were held under such contracts of limited ]. Except for those indentured for life, they were released after a contracted period. Those who managed to survive their period of indenture would receive land and equipment after their contracts expired or were bought out.<ref>Horton (2002), p. 26</ref> Most white laborers in this period also came to the colony as indentured servants.{{citation needed|date=March 2021}} | |||

| António almost died in the ] when Bennett's ] was attacked. The ], who were the ] dominant at that time in the ] of Virginia, were attempting to evict the colonists. They raided the settlement where Johnson worked on ] and killed 52 of the 57 men present.{{citation needed|date=March 2021}} | |||

| For those that survived the work and received their freedom package, many historians argue that they were better off than those new immigrants who came freely to the country. Their contract may have included at least 25 acres of land, a year's worth of corn, arms, a cow and new clothes. Some servants did rise to become part of the colonial elite, but for the majority of indentured servants that survived the treacherous journey by sea and the harsh conditions of life in the New World, satisfaction was a modest life as a freeman in a burgeoning colonial economy. | |||

| In 1623, a Black woman named Mary arrived aboard the ship ''Margaret''. She was brought to work on the same plantation as António, where she was the only woman present. António and Mary married and lived together for more than forty years.<ref name="Breen10">Breen (1980), p. 10.</ref> | |||

| ===Freedom=== | |||

| By around 1635 Antonio and Mary were free, and Antonio changed his name to Anthony Johnson.<ref name="Breen10"/> In the late 1640s he moved to the ] in ] where he acquired {{convert|250|acre|ha}} of land on the eastern shore. | |||

| ===Conclusion of indentured servitude=== | |||

| In 1657, Johnson’s white neighbor, ], forged a letter in which Johnson acknowledged a debt. Even though Johnson was clearly illiterate and couldn’t have written the letter, the court granted Scarborough 100 acres of Johnson’s land to pay off his "debt". | |||

| Sometime after 1635, António and Mary concluded the terms of their indentured servitude. António changed his name to Anthony Johnson.<ref name="Breen10" /> He first entered the legal record as an unindentured man when he purchased a calf in 1647.<ref>{{Cite book |last=D.P.A |first=Archie Morris III |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NvKRDwAAQBAJ&dq=anthony+Johnson+first+enters+the+legal+record+as+a+free+man+when+he+purchased+a+calf+in+1647.&pg=PT18 |title=Up from Slavery; an Unfinished Journey: The Legacy of Dunbar High School |date=2019 |publisher=AuthorHouse |isbn=978-1728304212 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| The colonial government granted Johnson a large plot of farmland after he paid off his indentured contract by his labor.<ref name="Rodriguez" /> On July 24, 1651, he acquired {{convert|250|acre|ha}} of land under the ] system by buying the contracts of five indentured servants, one of whom was his son, Richard Johnson. The headright system worked so that if a man were to bring indentured servants over to the colonies (in this particular case, Johnson brought the five servants), he was owed 50 acres a "head", or servant.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A87350120/ITOF?sid=lms|title='Black and white' in Colonial Virginia|website=link.galegroup.com|language=en|access-date=2019-12-11}}</ref> The land was located on the Great Naswattock Creek, which flowed into the ] in ].<ref name="Heinegg">{{cite book | last = Heinegg | first = Paul | year = 2005 | title = Free Africans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina from the Colonial Period to about 1820, Volume 2 | publisher = Genealogical Publishing | page=705 | isbn = 978-0806352824 }}</ref> | |||

| In 1665, Anthony Johnson and his family moved to Somerset County, Maryland, and negotiated a lease on a {{convert|300|acre|ha|adj=on}} plot of land for ninety-nine years. Johnson used this land to start a tobacco farm, which he named Tories Vineyards.<ref>Johnson 1999, p. 44.</ref> | |||

| Johnson ran a tobacco farm using indentured servants. One of those servants, ], would later become one of the first African men to be declared indentured for life.<ref name="auto">{{cite news | url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/horrible-fate-john-casor-180962352/#TewjfFASFy7jWzhh.99, | title=The Horrible Fate of John Casor, The First Black Man to be Declared Slave for Life in The Colonies| newspaper=Smithsonian Magazine| last1=Magazine| first1=Smithsonian}}</ref> | |||

| === Court cases during his life === | |||

| By July 1651 Johnson had five indentured servants of his own and he claimed an additional {{convert|250|acre|ha}} of land based on the ].<ref name="Rodriguez352"/> He is recognized in Virginia court documents when he pled for tax relief in 1653 after a fire destroyed much of his plantation,<ref>Breen 1980, p. 11.</ref> and in a case brought in 1654 in which he contested the freedom suit of a servant, ]. Johnson won the suit and retained Casor as his servant for life. In the tax-relief case, the justices noted that Anthony and Mary "have lived Inhabitants in Virginia (above thirty years)" and had been respected for their "hard labor and known service".<ref name="Breen10"/> | |||

| In 1652, "an unfortunate fire" caused "great losses" for the family, and Johnson applied to the courts for tax relief. The court reduced the family's taxes and, on February 28, 1652, exempted his wife Mary and their two daughters from paying taxes "during their natural lives." At that time, taxes were levied on people, not property. Under the 1645 Virginia taxation act, "all negro men and women and all other men from the age of 16 to 60 shall be judged tithable."<ref name="Heinegg" /><ref name="Breen">{{cite book | last = Breen | first = T. H. | year = 2004 | title = "Myne Owne Ground" : Race and Freedom on Virginia's Eastern Shore, 1640–1676 | publisher = Oxford University Press | page=12 | isbn = 978-0199729050 }}</ref> It is unclear from the records why the Johnson women were exempted, but the change gave them the same social standing as white women, who were not taxed.<ref name="Breen" /> During the case, the justices noted that Anthony and Mary "have lived Inhabitants in Virginia (above thirty years)" and had been respected for their "hard labor and known service".<ref name="Breen10" /> | |||

| ==Court ruling after death== | |||

| When Anthony was released he was legally recognized as a “free Negro” and ran a successful farm. In 1651 he held 250 acres and five black indentured servants. In 1654, it was time for Anthony to release John Casor, a black indentured servant. Instead Anthony told Casor he was extending his time. Casor left and became employed by the free white man Robert Parker. | |||

| By the 1650s, Anthony and Mary Johnson were farming 250 acres in Northampton County, while their two sons owned 550 acres.<ref>, encyclopediavirginia.org. Accessed March 9, 2023.</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Lombard |first1=Anne |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2hexv5SmqLgC&dq=anthony+johnson+virginia+indentured+gained+freedom+in+16&pg=PT85 |title=Colonial America: A History to 1763 |last2=Middleton |first2=Richard |date=2011 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-1444396287 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Anthony Johnson sued Robert Parker in the Northampton Court in 1654. In 1655, the court ruled that Anthony Johnson could hold John Casor indefinitely. The court gave judicial sanction for blacks to own slave of their own race. Thus Casor became the first permanent slave and Johnson the first slave owner. | |||

| ==Casor lawsuit== | |||

| Whites still could not legally hold a black servant as an indefinite slave until 1670. In that year, the colonial assembly passed legislation permitting free whites, blacks, and Indians the right to own blacks as slaves. | |||

| When Anthony Johnson was released from his servitude, he was legally recognized as a "free Negro." He became a successful farmer. In 1651, he owned {{convert|250|acre|ha}} and the services of five indentured servants (four white and one black). In 1653, John Casor, a black indentured servant whose contract Johnson appeared to have bought in the early 1640s, approached Captain Samuel Goldsmith, claiming his indenture had expired seven years earlier and that he was being held illegally by Johnson. A neighbor, Robert Parker, intervened and persuaded Johnson to free Casor. | |||

| == Significance == | |||

| Slavery was established in Virginia in 1655, when Johnson convinced a court that his servant John Casor (also a black man), was his for life.<ref name="Sweet2005">{{Cite book|author=Frank W. Sweet|title=Legal History of the Color Line: The Rise and Triumph of the One-Drop Rule|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=kezflCVnongC&pg=PA117|accessdate=23 February 2013|date=July 2005|publisher=Backintyme|isbn=978-0-939479-23-8|page=117}}</ref> Johnson himself had been brought to Virginia some years earlier as an indentured servant but he had saved enough money to buy out the remainder of his contract and that of his wife. The court ruling in Johnson’s favor resulted in Casor becoming the first state-recognized slave in the ]. Slavery in Virginia was officially enacted in state law for free whites, blacks, and Indians in 1661.<ref>Act CII, Laws of Virginia, March, 1661-2 (Hening, Statutes at Large, 2: 116-17)</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Typically, young men or women would sign a contract of indenture in exchange for transportation to the New World. The landowner received 50 acres of land from the state (headrights) for each servant purchased (around £6 per person in the 17th Century) from a ships captain. The status of indentured servants in early Virginia and Maryland was similar to slavery. Servants could be bought, sold, or leased. They could be physically beaten for disobedience or running away. Unlike slaves they were freed after their term of service expired or was bought out, their children did not inherit their status, and on their release from contract they received "a year's provision of corn, double apparel, tools necessary" and a small cash payment called "freedom dues."—John Hammond ''Indentured Servitude''. Johnson himself had arrived in Virginia as an indentured servant. | |||

| Parker offered Casor work, and he signed a term of indenture to the planter. Johnson filed a ] against Parker in the Northampton Court in 1654 for the return of Casor. The court initially found in favor of Parker, but Johnson appealed. In 1655, the court reversed its ruling.<ref name="Walker">{{cite book | last = Walker | first = Juliet | year = 2009 | title = The History of Black Business in America: Capitalism, Race, Entrepreneurship, Volume 1 | publisher = ] | page=49 | isbn = 978-0807832417 }}</ref> Finding that Anthony Johnson still "owned" John Casor, the court ordered that he be returned with the court dues paid by Robert Parker.<ref name="Sweet2005">{{Cite book|author=Frank W. Sweet|title=Legal History of the Color Line: The Rise and Triumph of the One-Drop Rule|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kezflCVnongC&pg=PA117|access-date=23 February 2013|date=2005|publisher=Backintyme|isbn=978-0939479238|page=117}}</ref> | |||

| The practice of importing Africans to the North American colonies started in the Virginia area in 1619, though ] brought African slaves to the Americas as early as the 1560s.<ref>], ''Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World.'' ], 2006, p. 124</ref> | |||

| This was the first instance of a judicial determination in the ] holding that a person who had committed no crime could be held in servitude for life.<ref name="Project">{{cite book | last = Federal Writers' Project | author-link = Federal Writers' Project | year = 1954 | title = Virginia: A Guide to the Old Dominion | publisher = US History Publishers |page=76 | isbn = 978-1603540452 }}</ref><ref name="Danver">{{cite book | last = Danver | first = Steven | year = 2010 | title = Popular Controversies in World History | publisher = ] | page=322 | isbn = 978-1598840780 }}</ref><ref name="Kozlowski">{{cite book | last = Kozlowski | first = Darrell | year = 2010 | title = Colonialism: Key Concepts in American History | publisher = ] | page=78 | isbn = 978-1604132175 }}</ref><ref name="Conway">{{cite book | last = Conway | first = John | year = 2008 | title = A Look at the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments: Slavery Abolished, Equal Protection Established | publisher = ] | page=5 | isbn = 978-1598450705 | url-access = registration | url = https://archive.org/details/lookatthirteenth0000conw }}</ref><ref name="Toppin">{{cite book | last = Toppin | first = Edgar | year = 2010 | title = The Black American in United States History | publisher = ]| page=46 | isbn = 978-1475961720 }}</ref> | |||

| By 1699, the number of free blacks prompted fears of a “Negro insurrection.” Virginia Colonial ordered the repatriation of freed blacks back to Africa. Many blacks sold themselves to white masters so they would not have to go to Africa. This was the first effort to repatriate free blacks back to Africa. The modern nations of Sierra Leone and Liberia both originated as colonies of repatriated former black slaves.However, black slave owners continued to thrive in the United States.By 1830 there were 3,775 black families living in the South who owned black slaves. By 1860 there were about 3,000 slaves owned by black households in the city of New Orleans alone. | |||

| Though Casor was the first person who was declared an enslaved person in a civil case, there were both black and white indentured servants sentenced to lifetime servitude before him. Many historians describe indentured servant ] as the first documented slave (or slave for life) in America as punishment for escaping his captors in 1640. It is considered one of the first legal cases to make a racial distinction between black and white indentured servants.<ref name="LLC"> ]</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.virtualjamestown.org/practise.html |title=Slave Laws |publisher=Virtual Jamestown |access-date=2013-11-04}}</ref> | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| <references /> | |||

| === Sources === | |||

| ===Significance of Casor lawsuit=== | |||

| *T.H. Breen and Stephen Innes, "Myne Owne Ground" Race and Freedom on Virginia's Eastern Shore, 1640–1676, Oxford University Press, 1980. | |||

| The Casor lawsuit demonstrates the culture and mentality of planters in the mid-17th century. Individuals made assumptions about the society of Northampton County and their place in it. According to historians T.H. Brean and Stephen Innes, Casor believed he could form a stronger relationship with his patron, Robert Parker, than Anthony Johnson had developed over the years with his patrons. Casor considered the dispute to be a matter of patron-client relationship, and this wrongful assumption resulted in his losing his case in court and having the ruling against him. Johnson knew that the local justices shared his fundamental belief in the sanctity of property. The judge sided with Johnson, although in future legal issues, race played a more prominent role.<ref>Breen and Innes, ''"Myne Owne Ground,"'' p. 15</ref> | |||

| *James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, Hard road to freedon: the story of African America, Rutgers University Press, 2002. | |||

| *Junius P. Rodriguez, Slavery in the United States: a social, political, and historical encyclopedia, Volume 2, ABC-CLIO, 2007. | |||

| The Casor lawsuit was an example of how difficult it was for Africans who were indentured servants to prevent being reduced to slavery. Most Africans could not read and had almost no knowledge of the English language. Planters found it easy to force them into slavery by refusing to acknowledge the completion of their indentured contracts.<ref name="Foner 1980"/> This is what happened in ''Johnson v. Parker.'' Although two white planters confirmed that Casor had completed his indentured contract with Johnson, the court still ruled in Johnson's favor.<ref>Klein, 43–44.</ref> | |||

| *Charles Johnson, Patricia Smith and the WGBH Research Team, Africans in America: America's Journey Through Slavery, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1999. | |||

| *Cox, Ryan Charles. "'', accessed 16 November 2012. | |||

| ==Later life== | |||

| *Ira Berlin, _Many Thousands Gone, The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America_, Harvard University Press, 1998. | |||

| ] | |||

| *''Virginia, Guide to The Old Dominion'', WPA Writers' Program, Oxford University Press, NY, 1940 (p. 378) | |||

| * | |||

| In 1657, Johnson's neighbor, ], allegedly forged a letter in which Johnson acknowledged a debt; whether this debt was real or not is unknown. Johnson did not contest the case. Johnson was illiterate and could not have written the letter; nevertheless, the court awarded Scarborough {{convert|100|acre|ha}} of Johnson's land to pay off his alleged "debt".<ref name="Rodriguez">{{cite book | last = Rodriguez | first = Junius | title = Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 2 | publisher = ] | page=353 | isbn = 978-1851095445 | year = 2007 }}</ref> | |||

| *Nash, Gary B., ], John R. Howe, Peter J. Frederick, Allen F. Davis, and Allan M. Winkler. The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society. 6th ed. New York: Pearson, 2004. 74-75. | |||

| *Matthews, Harry Bradshaw, The Family Legacy of Anthony Johnson: From Jamestown, VA to Somerset, MD, 1619-1995. Oneonta, NY: Sondhi Loimthongkul Center for Interdependenc, Hartwick College, 1995. | |||

| In this early period, free blacks enjoyed "relative equality" with the white community. About 20% of free black Virginians owned their own homes. In 1662, the Virginia Colony passed a law that children in the colony were born with the social status of their mother, according to the Roman principle of '']''. This meant that the children of slave women were born into slavery, even if their fathers were free, European, Christian, and white. This was a reversal of English ], which held that the children of English subjects took the status of their father. The Virginian colonial government expressed the opinion that since Africans were not Christians, common law could not and did not apply to them.<ref name="Banks">, Digital Commons Law, University of Maryland Law School. Retrieved April 21, 2009.</ref> | |||

| Anthony Johnson moved his family to ] in 1655, where he negotiated a lease on a {{convert|300|acres|ha|adj=on}} plot of land for ninety-nine years.<ref></ref> He developed the property as a ] farm, which he named Tories Vineyard.<ref>Johnson (1999), ''Africans in America'', p. 44.</ref> Mary survived, and in 1672, she bequeathed a cow to each of her grandsons. | |||

| Research indicates that when Johnson died in 1670, his plantation was given to a white colonist, not to Johnson's children. A judge had ruled that he was "not a citizen of the colony" because he was black. | |||

| <ref name="auto"/> In 1677, Anthony and Mary's grandson, John Jr., purchased a {{convert|44|acre|ha|adj=on|abbr=off}} farm, which he named Angola. John Jr. died without leaving an heir, however. By 1730, the Johnson family had vanished from historical significance.<ref>, Black Past.org</ref> Genealogical research suggests that some of Anthony's other descendants moved to Delaware and then to North Carolina.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://news.asu.edu/20190819-discoveries-impossible-story-african-pioneer-colonial-america|title = The impossible story of an African pioneer in colonial America|date = 19 August 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.freeafricanamericans.com/Jeffery_Johnson.htm|title = Jeffery-Johnson}}</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ===Sources=== | |||

| <!--Keep in alphabetical order by surname of author; make format standard--> | |||

| * Berlin, Ira. ''Many Thousands Gone, The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America'', Harvard University Press, 1998. | |||

| * Breen, Timothy and Stephen Innes. ''"Myne Own Ground" Race and Freedom on Virginia's Eastern Shore,'' 1979/reprint 2004, 25th-anniversary edition: Oxford University Press | |||

| * Cox, Ryan Charles. "The Johnson Family: The Migratory Study of an African-American Family on the Eastern Shore", ''Delmarva Settlers]'', University of Maryland Salisbury, accessed 16 November 2012. | |||

| * Horton, James Oliver and ], ''Hard Road to Freedom: The Story of African America,'' Rutgers University Press, 2002. | |||

| * Johnson, Charles; Patricia Smith, and the ] Research Team, ''Africans in America: America's Journey Through Slavery,'' Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1999. | |||

| * Klein, Herbert S. ''Slavery in the Americas; A Comparative Study of Virginia and Cuba''.{{ISBN?}} | |||

| * Nash, Gary B., ], John R. Howe, Peter J. Frederick, Allen F. Davis, and Allan M. Winkler. ''The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society''. 6th ed. New York: Pearson, 2004. 74–75.{{ISBN?}} | |||

| * Matthews, Harry Bradshaw, ''The Family Legacy of Anthony Johnson: From Jamestown, VA to Somerset, MD, 1619–1995'', Oneonta, NY: Sondhi Loimthongkul Center for Interdependence, Hartwick College, 1995.{{ISBN?}} | |||

| * Russell, Jack Henderson. ''The Free Negro in Virginia, 1619–1865,'' Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1913 | |||

| * WPA Writers' Program, ''Virginia, Guide to The Old Dominion'', Oxford University Press, NY, 1940 (p. 378) | |||

| * , Thinkport Library | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| * |

* , ''Africans in America,'' PBS.org | ||

| * | * , Exploring Maryland's Roots | ||

| * , "The Blurred Racial Lines Famous Families" ''Frontline'' PBS | |||

| * {{Persondata <!-- Metadata: see ]. --> | |||

| * | |||

| | NAME = Johnson, Anthony | |||

| * | |||

| | ALTERNATIVE NAMES = | |||

| * | |||

| | SHORT DESCRIPTION = Farmer, slave owner | |||

| * | |||

| | DATE OF BIRTH = | |||

| * | |||

| | PLACE OF BIRTH = Angola | |||

| | DATE OF DEATH = 1670 | |||

| {{Slavery in Virginia}} | |||

| | PLACE OF DEATH = Virginia, United States | |||

| {{Jamestown Colony}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Johnson, Anthony}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Johnson, Anthony}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 01:54, 25 December 2024

Indentured servant, farmer, enslaver (1600–1670) For other people named Anthony Johnson, see Anthony Johnson (disambiguation).| Anthony Johnson | |

|---|---|

| Born | unknown c. 1600 Portuguese Angola |

| Died | 1670 (1671) (aged 69–70) Colony of Virginia |

| Other names | António or Antonio |

| Occupation | Farmer |

| Known for | An African man indentured in Maryland who amassed sizable landholding and had indentured servants and enslaved people in the 1600s. |

| Signature | |

| |

Anthony Johnson (b. c. 1600 – d. 1670) was an Angolan-born man who achieved wealth in the early 17th-century Colony of Virginia. Held as an indentured servant in 1621, he earned his freedom after several years and was granted land by the colony.

He later became a tobacco farmer in Maryland. He attained great wealth after completing his term as an indentured servant and has been referred to as "'the black patriarch' of the first community of Negro property owners in America".

Biography

Early life

In the early 1620s, African slave traders kidnapped the man who would later be known as Anthony Johnson in Portuguese Angola and sold him to Portuguese slavers, who named him António and sold him into the Atlantic slave trade. A colonist in Virginia acquired António. As an indentured servant, António worked for a merchant at the Virginia Company. He was also received into the Roman Catholic Church.

Servitude in Virginia

He sailed to Virginia in 1621 aboard the James. The Virginia Muster (census) of 1624 lists his name as "Antonio not given," recorded as "a Negro" in the "notes" column. Historians dispute whether this was the same António later known as Anthony Johnson, as the census lists several men named "Antonio". This one is considered the most likely.

Johnson was sold as an "indentured servant" to merchant Edward Bennett to work on his Virginia tobacco farm, Warrosquoake, on the southern bank of the James River. Slave laws were not passed until 1661 in Virginia; before that date, Africans were not officially considered to be enslaved.

Such workers typically worked under a limited indenture contract for four to seven years to pay off their passage, room, board, lodging, and freedom dues. In the early colonial years, most Africans in the Thirteen Colonies were held under such contracts of limited indentured servitude. Except for those indentured for life, they were released after a contracted period. Those who managed to survive their period of indenture would receive land and equipment after their contracts expired or were bought out. Most white laborers in this period also came to the colony as indentured servants.

António almost died in the Indian massacre of 1622 when Bennett's plantation was attacked. The Powhatan, who were the indigenous people dominant at that time in the Tidewater region of Virginia, were attempting to evict the colonists. They raided the settlement where Johnson worked on Good Friday and killed 52 of the 57 men present.

In 1623, a Black woman named Mary arrived aboard the ship Margaret. She was brought to work on the same plantation as António, where she was the only woman present. António and Mary married and lived together for more than forty years.

Conclusion of indentured servitude

Sometime after 1635, António and Mary concluded the terms of their indentured servitude. António changed his name to Anthony Johnson. He first entered the legal record as an unindentured man when he purchased a calf in 1647.

The colonial government granted Johnson a large plot of farmland after he paid off his indentured contract by his labor. On July 24, 1651, he acquired 250 acres (100 ha) of land under the headright system by buying the contracts of five indentured servants, one of whom was his son, Richard Johnson. The headright system worked so that if a man were to bring indentured servants over to the colonies (in this particular case, Johnson brought the five servants), he was owed 50 acres a "head", or servant. The land was located on the Great Naswattock Creek, which flowed into the Pungoteague River in Northampton County, Virginia.

Johnson ran a tobacco farm using indentured servants. One of those servants, John Casor, would later become one of the first African men to be declared indentured for life.

In 1652, "an unfortunate fire" caused "great losses" for the family, and Johnson applied to the courts for tax relief. The court reduced the family's taxes and, on February 28, 1652, exempted his wife Mary and their two daughters from paying taxes "during their natural lives." At that time, taxes were levied on people, not property. Under the 1645 Virginia taxation act, "all negro men and women and all other men from the age of 16 to 60 shall be judged tithable." It is unclear from the records why the Johnson women were exempted, but the change gave them the same social standing as white women, who were not taxed. During the case, the justices noted that Anthony and Mary "have lived Inhabitants in Virginia (above thirty years)" and had been respected for their "hard labor and known service".

By the 1650s, Anthony and Mary Johnson were farming 250 acres in Northampton County, while their two sons owned 550 acres.

Casor lawsuit

When Anthony Johnson was released from his servitude, he was legally recognized as a "free Negro." He became a successful farmer. In 1651, he owned 250 acres (100 ha) and the services of five indentured servants (four white and one black). In 1653, John Casor, a black indentured servant whose contract Johnson appeared to have bought in the early 1640s, approached Captain Samuel Goldsmith, claiming his indenture had expired seven years earlier and that he was being held illegally by Johnson. A neighbor, Robert Parker, intervened and persuaded Johnson to free Casor.

March 8, 1655

Parker offered Casor work, and he signed a term of indenture to the planter. Johnson filed a Freedom suit against Parker in the Northampton Court in 1654 for the return of Casor. The court initially found in favor of Parker, but Johnson appealed. In 1655, the court reversed its ruling. Finding that Anthony Johnson still "owned" John Casor, the court ordered that he be returned with the court dues paid by Robert Parker.

This was the first instance of a judicial determination in the Thirteen Colonies holding that a person who had committed no crime could be held in servitude for life.

Though Casor was the first person who was declared an enslaved person in a civil case, there were both black and white indentured servants sentenced to lifetime servitude before him. Many historians describe indentured servant John Punch as the first documented slave (or slave for life) in America as punishment for escaping his captors in 1640. It is considered one of the first legal cases to make a racial distinction between black and white indentured servants.

Significance of Casor lawsuit

The Casor lawsuit demonstrates the culture and mentality of planters in the mid-17th century. Individuals made assumptions about the society of Northampton County and their place in it. According to historians T.H. Brean and Stephen Innes, Casor believed he could form a stronger relationship with his patron, Robert Parker, than Anthony Johnson had developed over the years with his patrons. Casor considered the dispute to be a matter of patron-client relationship, and this wrongful assumption resulted in his losing his case in court and having the ruling against him. Johnson knew that the local justices shared his fundamental belief in the sanctity of property. The judge sided with Johnson, although in future legal issues, race played a more prominent role.

The Casor lawsuit was an example of how difficult it was for Africans who were indentured servants to prevent being reduced to slavery. Most Africans could not read and had almost no knowledge of the English language. Planters found it easy to force them into slavery by refusing to acknowledge the completion of their indentured contracts. This is what happened in Johnson v. Parker. Although two white planters confirmed that Casor had completed his indentured contract with Johnson, the court still ruled in Johnson's favor.

Later life

In 1657, Johnson's neighbor, Edmund Scarborough, allegedly forged a letter in which Johnson acknowledged a debt; whether this debt was real or not is unknown. Johnson did not contest the case. Johnson was illiterate and could not have written the letter; nevertheless, the court awarded Scarborough 100 acres (40 ha) of Johnson's land to pay off his alleged "debt".

In this early period, free blacks enjoyed "relative equality" with the white community. About 20% of free black Virginians owned their own homes. In 1662, the Virginia Colony passed a law that children in the colony were born with the social status of their mother, according to the Roman principle of partus sequitur ventrem. This meant that the children of slave women were born into slavery, even if their fathers were free, European, Christian, and white. This was a reversal of English common law, which held that the children of English subjects took the status of their father. The Virginian colonial government expressed the opinion that since Africans were not Christians, common law could not and did not apply to them.

Anthony Johnson moved his family to Somerset County, Maryland in 1655, where he negotiated a lease on a 300-acre (120 ha) plot of land for ninety-nine years. He developed the property as a tobacco farm, which he named Tories Vineyard. Mary survived, and in 1672, she bequeathed a cow to each of her grandsons.

Research indicates that when Johnson died in 1670, his plantation was given to a white colonist, not to Johnson's children. A judge had ruled that he was "not a citizen of the colony" because he was black. In 1677, Anthony and Mary's grandson, John Jr., purchased a 44-acre (18-hectare) farm, which he named Angola. John Jr. died without leaving an heir, however. By 1730, the Johnson family had vanished from historical significance. Genealogical research suggests that some of Anthony's other descendants moved to Delaware and then to North Carolina.

See also

References

- ^ Foner, Philip S. (1980). History of Black Americans: From Africa to the Emergence of the Cotton Kingdom. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2013-10-14.

- Horton (2002), p. 29.

- Pender, Alicia (2021-03-13). "Catholics who care about US Black history must read 'Four Hundred Souls'". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- Breen 1980, p. 8.

- Walsh, Lorena (2010). Motives of Honor, Pleasure, and Profit: Plantation Management in the Colonial Chesapeake, 1607–1763. UNC Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0807832349.

- "Bennett's Plantation Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org.

- Indentured Servants In The U.S., pbs.org. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- Horton (2002), p. 26

- ^ Breen (1980), p. 10.

- D.P.A, Archie Morris III (2019). Up from Slavery; an Unfinished Journey: The Legacy of Dunbar High School. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1728304212.

- ^ Rodriguez, Junius (2007). Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 353. ISBN 978-1851095445.

- "'Black and white' in Colonial Virginia". link.galegroup.com. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- ^ Heinegg, Paul (2005). Free Africans of North Carolina, Virginia, and South Carolina from the Colonial Period to about 1820, Volume 2. Genealogical Publishing. p. 705. ISBN 978-0806352824.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian. "The Horrible Fate of John Casor, The First Black Man to be Declared Slave for Life in The Colonies". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Breen, T. H. (2004). "Myne Owne Ground" : Race and Freedom on Virginia's Eastern Shore, 1640–1676. Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0199729050.

- Virginia's First Africans, encyclopediavirginia.org. Accessed March 9, 2023.

- Lombard, Anne; Middleton, Richard (2011). Colonial America: A History to 1763. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1444396287.

- Walker, Juliet (2009). The History of Black Business in America: Capitalism, Race, Entrepreneurship, Volume 1. University of North Carolina Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0807832417.

- Frank W. Sweet (2005). Legal History of the Color Line: The Rise and Triumph of the One-Drop Rule. Backintyme. p. 117. ISBN 978-0939479238. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- Federal Writers' Project (1954). Virginia: A Guide to the Old Dominion. US History Publishers. p. 76. ISBN 978-1603540452.

- Danver, Steven (2010). Popular Controversies in World History. ABC-CLIO. p. 322. ISBN 978-1598840780.

- Kozlowski, Darrell (2010). Colonialism: Key Concepts in American History. Infobase Publishing. p. 78. ISBN 978-1604132175.

- Conway, John (2008). A Look at the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments: Slavery Abolished, Equal Protection Established. Enslow Publishers. p. 5. ISBN 978-1598450705.

- Toppin, Edgar (2010). The Black American in United States History. Allyn & Bacon. p. 46. ISBN 978-1475961720.

- Slavery and Indentured Servants Law Library of Congress

- "Slave Laws". Virtual Jamestown. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

- Breen and Innes, "Myne Owne Ground," p. 15

- Klein, 43–44.

- Taunya Lovell Banks, "Dangerous Woman: Elizabeth Key's Freedom Suit – Subjecthood and Racialized Identity in Seventeenth Century Colonial Virginia", Digital Commons Law, University of Maryland Law School. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- Johnson, Charles, and Smith, Patricia. Africans in America: America's Journey Through Slavery. United States, Harcourt Brace, 1999.

- Johnson (1999), Africans in America, p. 44.

- "Johnson, Anthony – 1670", Black Past.org

- "The impossible story of an African pioneer in colonial America". 19 August 2019.

- "Jeffery-Johnson".

Sources

- Berlin, Ira. Many Thousands Gone, The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America, Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Breen, Timothy and Stephen Innes. "Myne Own Ground" Race and Freedom on Virginia's Eastern Shore, 1979/reprint 2004, 25th-anniversary edition: Oxford University Press

- Cox, Ryan Charles. Delmarva Settlers Settlers and Sites - "The Johnson Family: The Migratory Study of an African-American Family on the Eastern Shore", Delmarva Settlers], University of Maryland Salisbury, accessed 16 November 2012.

- Horton, James Oliver and Lois E. Horton, Hard Road to Freedom: The Story of African America, Rutgers University Press, 2002.

- Johnson, Charles; Patricia Smith, and the WGBH Research Team, Africans in America: America's Journey Through Slavery, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1999.

- Klein, Herbert S. Slavery in the Americas; A Comparative Study of Virginia and Cuba.

- Nash, Gary B., Julie R. Jeffrey, John R. Howe, Peter J. Frederick, Allen F. Davis, and Allan M. Winkler. The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society. 6th ed. New York: Pearson, 2004. 74–75.

- Matthews, Harry Bradshaw, The Family Legacy of Anthony Johnson: From Jamestown, VA to Somerset, MD, 1619–1995, Oneonta, NY: Sondhi Loimthongkul Center for Interdependence, Hartwick College, 1995.

- Russell, Jack Henderson. The Free Negro in Virginia, 1619–1865, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1913

- WPA Writers' Program, Virginia, Guide to The Old Dominion, Oxford University Press, NY, 1940 (p. 378)

- "Anthony Johnson", Thinkport Library

External links

- "Anthony Johnson", Africans in America, PBS.org

- "Anthony Johnson", Exploring Maryland's Roots

- Johnson Family, "The Blurred Racial Lines Famous Families" Frontline PBS

- Site of 17th Century Estate of Anthony and Mary Johnson

- Johnson Family Genealogy Report

- Anthony Johnson (?–1670), BlackPast

- Fact CheckF: 9 'Facts' About Slavery They Don't Want You to Know

- Court Ruling on Anthony Johnson and His Servant (1655)