| Revision as of 18:30, 6 June 2006 editARYAN818 (talk | contribs)594 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 15:23, 22 December 2024 edit undoDemetrios1993 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers9,012 editsm MOS:PAGERANGE | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Ancestor of the Indo-European languages}} | |||

| {{dablink|PIE redirects here. See ] for other uses.}} | |||

| {{redirect2|PIE|Proto-Indo-European|the people|Proto-Indo-Europeans|other uses|PIE (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Distinguish|Pre-Indo-European languages|Paleo-European languages}} | |||

| {{Infobox proto-language | |||

| | name = Proto-Indo-European | |||

| | altname = PIE | |||

| | region = ] {{Small|(])}} | |||

| | era = {{circa|4500|2500}} BC | |||

| | familycolor = Indo-European | |||

| | target = ] | |||

| | child1 = ] | |||

| | child2 = ] | |||

| | child3 = ] | |||

| | child4 = ] | |||

| | child5 = ] | |||

| | child6 = ] | |||

| | child7 = ] | |||

| | child8 = ] | |||

| | child9 = ] | |||

| | child10 = ] | |||

| | listclass = | |||

| | boxsize = | |||

| | module = | |||

| | notes = | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Indo-European topics}} | |||

| {{Contains special characters|PIE}} | |||

| '''Proto-Indo-European''' ('''PIE''') is the reconstructed common ancestor of the ].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Indo-European languages – The parent language: Proto-Indo-European|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Indo-European-languages|access-date=2021-09-19|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en}}</ref> No direct record of Proto-Indo-European exists; its proposed features have been derived by ] from documented Indo-European languages.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.ed.ac.uk/files/atoms/files/archaeology_et_al_-_an_indo-european_study.pdf |title=Archaeology et al: an Indo-European study |date=2018-04-11 |website=School of History, Classics and Archaeology |publisher=The University of Edinburgh |access-date=2018-12-01}}</ref> | |||

| Far more work has gone into reconstructing PIE than any other ], and it is the best understood of all proto-languages of its age. The majority of linguistic work during the 19th century was devoted to the reconstruction of PIE and its ]s, and many of the modern techniques of linguistic reconstruction (such as the ]) were developed as a result.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Ivić |first=Pavle |last2=Hamp |first2=Eric P. |last3=Lyons |first3=John |date=March 5, 2024 |title=Linguistics |url=https://www.britannica.com/science/linguistics/The-comparative-method |access-date=August 9, 2024 |website=Encyclopaedia Britannica}}</ref> | |||

| The '''Indo-European''' is short for ] and ]. The founder of all Indo-European languages were that ] people who were believed to have originated in Northern ] & parts of ] and ]. The first language of the Aryans was a language called ]. | |||

| PIE is hypothesized to have been spoken as a single language from approximately 4500 BCE to 2500 BCE<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.archaeology.org/exclusives/articles/1302-proto-indo-european-schleichers-fable |title=Telling Tales in Proto-Indo-European |work=Archaeology |last=Powell |first=Eric A. |access-date=2017-07-30 }}</ref> during the Late ] to Early ], though estimates vary by more than a thousand years. According to the prevailing ], the ] of the ] may have been in the ] of eastern Europe. The linguistic reconstruction of PIE has provided insight into the pastoral ] and patriarchal ] of its speakers.{{sfnp|Fortson|2010|p=16}} | |||

| All Indo-European languages are ] (although many modern Indo-European languages, including ], have lost much of their inflection). By comparative reconstruction, it is quite likely that at least the latest stage of the common PIE mother languages (''Late'' PIE) was an inflectional language, which was more ]ing than ]ing. | |||

| As speakers of Proto-Indo-European became isolated from each other through the ], the regional ]s of Proto-Indo-European spoken by the various groups diverged, as each dialect underwent shifts in pronunciation (the ]), morphology, and vocabulary. Over many centuries, these dialects transformed into the known ancient Indo-European languages. From there, further linguistic divergence led to the evolution of their current descendants, the modern Indo-European languages. | |||

| However, by means of internal reconstruction and ] (re-)analysis of the reconstructed, seemingly most ancient PIE word forms, it has recently been shown to be very probable that at a more distant stage PIE (''Early'' PIE) may have been a root-inflected language, as was ]. As a consequence, it seems to be highly probable that PIE once was of the root-and-pattern morphological type (literature: Pooth (2004): "''Ablaut und autosegmentale Morphologie: Theorie der uridg. Wurzelflexion''", in: Arbeitstagung "''Indogermanistik, Germanistik, Linguistik''" in Jena, Sept. 2002). | |||

| PIE is believed to have had an elaborate system of ] that included ] (analogous to English ''child, child's, children, children's'') as well as ] (vowel alterations, as preserved in English ''sing, sang, sung, song'') and ]. PIE ] and ] had a complex system of ], and ] similarly had a complex system of ]. The PIE ], ], ], and ] are also well-reconstructed. | |||

| ==Discovery and Reconstruction== | |||

| PIE was first proposed in the 18th century AD as the basal language for the Indo-European languages then known, which included Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit. PIE did not account for the language families Anatolian and Tocharian; in addition to being unknown then, the two were never spoken either in India or in Europe, and they most likely branched away from their common ancestor millennia prior to the root of PIE as formerly defined. It also did not account for PIE's hypothesized ] consonants—only after the discovery of these consonants in ancient the ] did they become an accepted part of the theory. But by common consent, Anatolian and Tocharian have always been accepted as "Indo-European". As a result, reconstructions of PIE's character, history, and homeland now take Anatolian and Tocharian into account. (Note that a sequence of Anatolian exit first and Tocharian exit second from PIE is compatible with ''both'' hypotheses on Indo-European origins.) | |||

| Asterisks are used by linguists as a conventional mark of reconstructed words, such as *{{PIE|''wódr̥''}}, *{{PIE|''ḱwn̥tós''}}, or *{{PIE|''tréyes''}}; these forms are the reconstructed ancestors of the modern English words ''water'', ''hound'', and ''three'', respectively. | |||

| There is no direct evidence of PIE, because it was never ]. All PIE sounds and words are reconstructed from later Indo-European languages using the ] and the method of ]. The ] is used to mark reconstructed PIE words, such as *{{unicode|wódr̥}} "]", *{{unicode|ḱwṓn}} "]", or *{{unicode|tréyes}} "three (masculine)". Many of the words in the modern Indo-European languages seem to have derived from such "protowords" via regular ]s (e.g., ]). | |||

| ===Relationship to other language families=== | |||

| ==Development of the hypothesis== | |||

| Many higher-level relationships between PIE and other language families have been proposed. Due to the great time depths, there is necessarily a great deal of speculation involved, and as a result the proposals are very controversial. Perhaps the most widely accepted proposal is of an ] family, encompassing PIE and ]. The evidence usually cited in favor of this is the proximity of the proposed ]en of the two families, the ] similarity between the two languages, and a number of apparent shared morphemes. ], while advocating a connection, concedes that "the gap between Uralic and Indo-European is huge", while Lyle Campbell, an authority of Uralic, denies any relationship exists. Other proposals, further back in time (and correspondingly less accepted), model PIE as a branch of Indo-Uralic with a ] substratum; link PIE and Uralic with ] and certain other families in Asia, such as ], ], ] and ] (representative proposals are ] and ]'s ]); or link some or all of these to ], ], etc., and ultimately to a single ] family (nowadays mostly associated with ]). Various proposals, with varying levels of skepticism, also exist that join some subset of the putative Eurasiatic language families and/or some of the ] language families, such as ], ] (once widely accepted but now largely discredited), ], etc. | |||

| No direct evidence of PIE exists; scholars have reconstructed PIE from its present-day descendants using the ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.britannica.com/science/linguistics/The-comparative-method#toc35116 |title=Linguistics – The comparative method |series=Science |publisher=Encyclopedia Britannica |access-date=27 July 2016}}</ref> For example, compare the pairs of words in Italian and English: {{lang|it|piede}} and ''foot'', {{lang|it|padre}} and ''father'', {{lang|it|pesce}} and ''fish''. Since there is a consistent correspondence of the initial consonants (''p'' and ''f'') that emerges far too frequently to be coincidental, one can infer that these languages stem from a common ].<ref name="comp-ling">{{cite encyclopedia |title=Comparative linguistics |url=https://www.britannica.com/science/comparative-linguistics |encyclopedia=] |access-date=27 August 2016}}</ref> Detailed analysis suggests a system of ] to describe the ] and ] changes from the hypothetical ancestral words to the modern ones. These laws have become so detailed and reliable as to support the ]: the Indo-European sound laws apply without exception. | |||

| ], an ] ] and ] in ], caused an academic sensation when in 1786 he postulated the common ancestry of ], ], ], ], the ], and ],<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Jones-British-orientalist-and-jurist |title=Sir William Jones, British orientalist and jurist |encyclopedia=] |access-date=3 September 2016}}</ref> but he was not the first to state such a hypothesis. In the 16th century, European visitors to the ] became aware of similarities between ]s and European languages,<ref name="auroux">{{cite book |first=Sylvain |last=Auroux |title=History of the Language Sciences |page=1156 |isbn=3-11-016735-2 |publisher=] |year=2000 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yasNy365EywC&q=3110167352&pg=PA1156}}</ref> and as early as 1653, ] had published a proposal for a ] ("Scythian") for the following language families: ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="Blench">{{cite book |author-link=Roger Blench |first=Roger |last=Blench |url=http://www.rogerblench.info/Archaeology/World/CH4-BLENCH.pdf |article=Archaeology and language: Methods and issues |title=A Companion to Archaeology |editor=Bintliff, J. |pages=52–74 |place=Oxford, UK |publisher=Basil Blackwell |year=2004}}</ref> In a memoir sent to the {{lang|fr|]|italic=no}} in 1767, {{lang|fr|]|italic=no}}, a French ] who spent most of his life in India, had specifically demonstrated the analogy between Sanskrit and European languages.<ref>{{cite web |first=Kip |last=Wheeler |title= The Sanskrit Connection: Keeping Up With the Joneses |url=http://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/IE_Main4_Sanskrit.html |publisher=] |access-date=16 April 2013 }}</ref> According to current academic consensus, Jones's famous work of 1786 was less accurate than his predecessors', as he erroneously included ], ] and ] in the Indo-European languages, while omitting ]. | |||

| ===Development=== | |||

| {{main|Indo-European sound laws}} | |||

| As the Proto-Indo-European language broke up, its sound system diverged as well, according to various ]s in the daughter languages. Notable among these are ] and ] in ], loss of prevocalic ''*p-'' in ], loss of prevocalic ''*s-'' in ], ] in ]. ] and ] may or may not have been still common Indo-European. | |||

| In 1818, Danish linguist ] elaborated the set of correspondences in his prize essay {{lang|da|Undersøgelse om det gamle Nordiske eller Islandske Sprogs Oprindelse}} ('Investigation of the Origin of the Old Norse or Icelandic Language'), where he argued that ] was related to the Germanic languages, and had even suggested a relation to the Baltic, Slavic, Greek, Latin and Romance languages.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Momma |first=Haruko |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WGYzp7olz6QC |title=From Philology to English Studies: Language and Culture in the Nineteenth Century |date=2013 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-521-51886-4 |pages=65–66 |language=en |author-link=Haruko Momma}}</ref> In 1816, ] published ''On the System of Conjugation in Sanskrit'', in which he investigated the common origin of Sanskrit, Persian, Greek, Latin, and German. In 1833, he began publishing the ''Comparative Grammar of Sanskrit, ], Greek, Latin, Lithuanian, Old Slavic, Gothic, and German''.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |url= https://www.britannica.com/biography/Franz-Bopp |title=Franz Bopp, German philologist |encyclopedia=] |access-date=26 August 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ==Phonology== | |||

| In 1822, ] formulated what became known as ] as a general rule in his {{lang|de|Deutsche Grammatik}}. Grimm showed correlations between the Germanic and other Indo-European languages and demonstrated that sound change systematically transforms all words of a language.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Grimms-law |title=Grimm's law, linguistics |encyclopedia=] |access-date=26 August 2016}}</ref> From the 1870s, the Neogrammarians proposed that sound laws have no exceptions, as illustrated by ], published in 1876, which resolved apparent exceptions to Grimm's law by exploring the role of accent (stress) in language change.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/science/Neogrammarian |title=Neogrammarian, German scholar |encyclopedia=] |access-date=26 August 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Proto-Indo-European is conjectured to have used the following ]. See ] for a summary of how these sounds evolved in the various Indo-European languages. | |||

| ]'s ''A Compendium of the Comparative Grammar of the Indo-European, Sanskrit, Greek and Latin Languages'' (1874–77) represented an early attempt to reconstruct the Proto-Indo-European language.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/August-Schleicher |title=August Schleicher, German linguist |encyclopedia=] |access-date=26 August 2016 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Consonants=== | |||

| By the early 1900s, ]s had developed well-defined descriptions of PIE which scholars still accept today. Later, the discovery of the ] and ] added to the corpus of descendant languages. A subtle new principle won wide acceptance: the ], which explained irregularities in the reconstruction of Proto-Indo-European phonology as the effects of hypothetical sounds which no longer exist in all languages documented prior to the excavation of ] tablets in Anatolian. This theory was first proposed by ] in 1879 on the basis of internal reconstruction only,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Saussure |first=Ferdinand de |url=http://archive.org/details/memoiresurlesyst00saus |title=Mémoire sur le système primitif des voyelles dans les langues indo-européennes |date=1879 |publisher=Leipsick : B. G. Teubner |others=University of California Libraries}}</ref> and progressively won general acceptance after ]'s discovery of consonantal reflexes of these reconstructed sounds in Hittite.<ref>Kuryłowicz, Jerzy (1927). "''ə'' indo-européen et ''ḫ'' hittite". In: Witold Taszycki and Witold Doroszewki (eds.), ''Symbolae Grammaticae in honorem Ioannis Rozwadowski'', v. 1, 95–104. Krakow: Uniwersytet Jagielloński.</ref> | |||

| ]'s {{lang|de|]}} ('Indo-European Etymological Dictionary', 1959) gave a detailed, though conservative, overview of the lexical knowledge accumulated by 1959. Jerzy Kuryłowicz's 1956 ''Apophonie'' gave a better understanding of ]. From the 1960s, knowledge of Anatolian became robust enough to establish its relationship to PIE. | |||

| ==Historical and geographical setting== | |||

| {{main|Proto-Indo-European homeland}} | |||

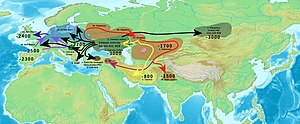

| ] from the ] and across Central Asia according to the widely held Kurgan hypothesis]] | |||

| {{anchor|Era}}{{anchor|Region}}Scholars have proposed multiple hypotheses about when, where, and by whom PIE was spoken. The ], first put forward in 1956 by ], has become the most popular.{{efn|See: | |||

| * Bomhard: "This scenario is supported not only by linguistic evidence, but also by a growing body of archeological and genetic evidence. The Indo-Europeans have been identified with several cultural complexes existing in that area between 4,500—3,500 BCE. The literature supporting such a homeland is both extensive and persuasive . Consequently, other scenarios regarding the possible Indo-European homeland, such as Anatolia, have now been mostly abandoned."{{sfn|Bomhard|2019|p=2}} | |||

| *Anthony & Ringe: "Archaeological evidence and linguistic evidence converge in support of an origin of Indo-European languages on the Pontic-Caspian steppes around 4,000 years BCE. The evidence is so strong that arguments in support of other hypotheses should be reexamined."{{sfn|Anthony|Ringe|2015|pp=199–219}} | |||

| * Mallory: "The Kurgan solution is attractive and has been accepted by many archaeologists and linguists, in part or total. It is the solution one encounters in the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' and the ''Grand Dictionnaire Encyclopédique Larousse''."{{sfn|Mallory|1989|p=185}} | |||

| * Strazny: "The single most popular proposal is the Pontic steppes (see the Kurgan hypothesis)..."{{sfn|Strazny|2000|p=163}}}} It proposes that the original speakers of PIE were the ] associated with the ]s (burial mounds) on the ] north of the Black Sea.<ref>{{cite book|title= The horse, the wheel, and language: how bronze-age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world|date= 2007|publisher= Princeton University Press|isbn= 978-0-691-05887-0|edition= 8th reprint|location= Princeton, N.J.|last1= Anthony|first1= David W.|author-link1= David W. Anthony|title-link= The Horse, the Wheel, and Language}}</ref>{{rp|305–7}}<ref name="Science">{{cite journal|url= https://www.science.org/content/article/mysterious-indo-european-homeland-may-have-been-steppes-ukraine-and-russia|title= Mysterious Indo-European homeland may have been in the steppes of Ukraine and Russia|last= Balter|first= Michael|date= 13 February 2015|journal= Science|doi= 10.1126/science.aaa7858|access-date= 17 February 2015}}</ref> According to the theory, they were ] who ], which allowed them to migrate across Europe and Asia in wagons and chariots.<ref name="Science" /> By the early 3rd millennium BCE, they had expanded throughout the Pontic–Caspian steppe and into eastern Europe.<ref>{{Cite journal|last= Gimbutas|first= Marija|year= 1985|title= Primary and Secondary Homeland of the Indo-Europeans: comments on Gamkrelidze-Ivanov articles|journal= Journal of Indo-European Studies|volume= 13|issue= 1–2|pages= 185–202}}</ref> | |||

| Other theories include the ],<ref name="bouckaert">{{Citation|title= Mapping the Origins and Expansion of the Indo-European Language Family|date= 24 August 2012|last1= Bouckaert|last2= Lemey|last3= Dunn|last4= Greenhill|last5= Alekseyenko|last6= Drummond|last7= Gray|last8= Suchard|first1= Remco|first2= P.|first3= M.|first4= S. J.|first5= A. V.|first6= A. J.|first7= R. D.|first8= M. A.|journal= Science|volume= 337|issue= 6097|pages= 957–960|doi= 10.1126/science.1219669|pmc= 4112997|pmid=22923579|display-authors= etal|bibcode= 2012Sci...337..957B|url= http://pubman.mpdl.mpg.de/pubman/item/escidoc:1539154/component/escidoc:1539165/Bouckaert_2012.pdf|hdl= 11858/00-001M-0000-000F-EADF-A}}</ref> which posits that PIE spread out from Anatolia with agriculture beginning {{circa}} 7500–6000 BCE,<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Chang|first1=Will|last2=Cathcart|first2=Chundra|last3=Hall|first3=David|last4=Garrett|first4=Andrew|date=2015|title=Ancestry-constrained phylogenetic analysis supports the Indo-European steppe hypothesis|url=https://muse.jhu.edu/content/crossref/journals/language/v091/91.1.chang.html|journal=Language|language=en|volume=91|issue=1|pages=194–244|doi=10.1353/lan.2015.0005| s2cid=143978664 |issn=1535-0665}}</ref> the ], the ], and the ] theory. The last two of these theories are not regarded as credible within academia.<ref>] (2006). ''''. National Book Trust. p. 127. {{ISBN|9788123747798}}.</ref><ref>"The opposing argument, that speakers of Indo-European languages were indigenous to the Indian subcontinent, is not supported by any reliable scholarship". ] (2017). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230514094423/https://inference-review.com/article/another-great-story |date=14 May 2023 }}", review of Asko Parpola's ''The Roots of Hinduism''. In: ''Inference, International Review of Science'', Volume 3, Issue 2.</ref> Out of all the theories for a PIE homeland, the Kurgan and Anatolian hypotheses are the ones most widely accepted, and also the ones most debated against each other.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mallory |first=J. P. |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/139999117 |title=The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World |date=2006 |publisher=Oxford University Press |others=Douglas Q. Adams |isbn=978-1-4294-7104-6 |location=New York |oclc=139999117}}</ref> Following the publication of several studies on ancient DNA in 2015, Colin Renfrew, the original author and proponent of the Anatolian hypothesis, has accepted the reality of migrations of populations speaking one or several Indo-European languages from the Pontic steppe towards Northwestern Europe.<ref>Renfrew, Colin (2017) "" (''The Oriental Institute lecture series : Marija Gimbutas memorial lecture'', Chicago. November 8, 2017).</ref><ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|last1=Pellard|first1=Thomas|last2=Sagart|first2=Laurent|author-link2=Laurent Sagart|last3=Jacques|first3=Guillaume|date=2018|title=L'indo-européen n'est pas un mythe|journal=Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris|volume=113|issue=1|pages=79–102|doi=10.2143/BSL.113.1.3285465|s2cid=171874630 }}</ref> | |||

| ] languages; right half: ] languages]] | |||

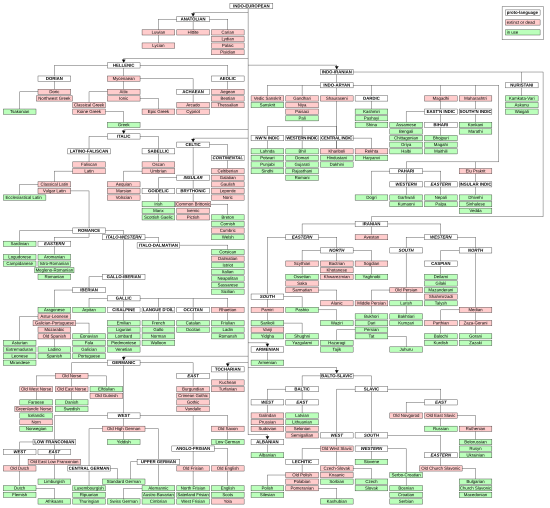

| ==Descendants== | |||

| {{main|Indo-European languages}} | |||

| The table lists the main Indo-European language families, comprising the languages descended from Proto-Indo-European. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| !Clade | |||

| |+ '''Proto-Indo-European consonants (traditional transcription)''' | |||

| !Proto-language | |||

| !Description | |||

| !Historical languages | |||

| !Modern descendants | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] | |||

| !] | |||

| |] | |||

| !] | |||

| |All now extinct, the best attested being the ]. | |||

| !] | |||

| |], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| !] | |||

| |There are no living descendants of Proto-Anatolian. | |||

| !] | |||

| !] | |||

| !] | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] | |||

| !] ] | |||

| |] | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|p}} | |||

| |An extinct branch known from manuscripts dating from the 6th to the 8th century AD and found in northwest China. | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|t}} | |||

| |Tocharian A, ] | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|ḱ}} | |||

| |There are no living descendants of Proto-Tocharian. | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|k}} | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|kʷ}} | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] | |||

| !] ] | |||

| |] | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|b}} | |||

| |This included many languages, but only descendants of ] (the ]) survive. | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|d}} | |||

| |], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|ǵ}} | |||

| |], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], Latin (as a ] of the Catholic Church and the official language of the ]), ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|g}} | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|gʷ}} | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] | |||

| !] ] | |||

| |] | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|bʰ}} | |||

| |Once spoken across Europe, but now mostly confined to its northwestern edge. | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|dʰ}} | |||

| |], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|ǵʰ}} | |||

| |], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|gʰ}} | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|gʷʰ}} | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] | |||

| !] | |||

| |] | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|m}} | |||

| |Branched into three subfamilies: ], ] (now extinct), and ]. | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|n}} | |||

| |], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | | |||

| |], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] | |||

| !] | |||

| |] | |||

| | | |||

| |Branched into the ] and the ]. | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|s}} | |||

| |], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | | |||

| |Baltic: ], ] and ]; | |||

| | | |||

| Slavic: ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|h₁, h₂, h₃}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] | |||

| !], ] | |||

| |] | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|w}} | |||

| |Branched into the ], ] and ] languages. | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|r, l}} | |||

| |], ], ]; ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | align=center | {{unicode|y}} | |||

| |Indo-Aryan: ] (] and ]), ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] (]); | |||

| | | |||

| Iranic: ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]; | |||

| | | |||

| ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |Branched into ] and ]. | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |Modern Greek and Tsakonian are the only surviving varieties of Greek. | |||

| |], ] | |||

| |], ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |Albanian is the only surviving representative of the ] branch of the Indo-European language family.<ref>{{cite book|last=Trumper|first=John|chapter=Some Celto-Albanian isoglosses and their implications|editor1-last=Grimaldi|editor1-first=Mirko|editor2-last=Lai|editor2-first=Rosangela|editor3-last=Franco|editor3-first=Ludovico|editor4-last=Baldi|editor4-first=Benedetta|title=Structuring Variation in Romance Linguistics and Beyond: In Honour of Leonardo M. Savoia|year=2018|publisher=John Benjamins Publishing Company|isbn=9789027263179|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kAR-DwAAQBAJ}} pp. 383–386.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.cs.rice.edu/~nakhleh/Papers/81.2nakhleh.pdf |title= Perfect Phylogenetic Networks: A New Methodology for Reconstructing the Evolutionary History of Natural Languages, pg. 396 |access-date= 22 September 2010 | archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20101105223804/http://www.cs.rice.edu/~nakhleh/Papers/81.2nakhleh.pdf | archive-date= 5 November 2010 | url-status = live}}</ref> | |||

| |] (disputed); ] (disputed) | |||

| |] (] and ]) | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| Commonly proposed subgroups of Indo-European languages include ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| The table gives the most common notation in modern publications. Variant transcriptions are given below. Raised {{unicode|ʰ}} stands for ]. According to the ], the "voiced stops" of the system as described above were glottalic, perhaps ], while the "voiced aspirated stops" may not have been voiced. | |||

| There are numerous lexical similarities between the Proto-Indo-European and ] languages due to early ],{{Citation needed|date=March 2023}} as well as some morphological similarities—notably the ], which is remarkably similar to the root ablaut system reconstructible for Proto-Kartvelian.<ref>Gamkrelidze, Th. & Ivanov, V. (1995). Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Analysis of a Proto-Language and a Proto-Culture. 2 Vols. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.</ref><ref>Gamkrelidze, T. V. (2008). Kartvelian and Indo-European: a typological comparison of reconstructed linguistic systems. Bulletin of the Georgian National Academy of Sciences 2 (2): 154–160.</ref> | |||

| *], ], ], and ] merged the voiced aspirated series {{unicode|bʰ, dʰ, ǵʰ, gʰ, gʷʰ}} with the plain voiced series {{unicode|b, d, ǵ, g, gʷ}}. (However, Proto-Celtic did not merge {{unicode |gʷʰ and gʷ}} - the first became g while the second became b). | |||

| *] underwent ], changing voiceless stops into fricatives, devoicing unaspirated voiced stops, and de-aspirating voiced aspirates. | |||

| *] ({{unicode|Tʰ-Tʰ}} > {{unicode|T-Tʰ}}, e.g. {{unicode|dʰi-dʰeh₁-}} > {{unicode|di-dʰeh₁-}}) and ] ({{unicode|TʰT}} > {{unicode|TTʰ}}, e.g. {{unicode|budʰ-to-}} > {{unicode|]}}) describe the behaviour of aspirates in particular contexts in some early daughter languages. | |||

| ===Marginally attested languages=== | |||

| ====Labials==== | |||

| The ] was a marginally attested language spoken in areas near the border between present-day ] and ]. | |||

| {{unicode|p, b, bʰ}}, grouped with the cover symbol ''P''. {{unicode|b}} was a very rare phoneme, which is one argument in favor of the glottalic theory - it seems that languages having ejective stops tend not to have an ejective labial stop {{unicode|p'}}. | |||

| The ] and ] languages known from the North Adriatic region are sometimes classified as Italic. | |||

| ====Coronals/Dentals==== | |||

| The standard reconstruction identified three coronal/dental stops: {{unicode|t, d, dʰ}}. They are symbolically grouped with the cover symbol ''T''. | |||

| Albanian and Greek are the only surviving Indo-European descendants of a ] language area, named for their occurrence in or in the vicinity of the ]. Most of the other languages of this area—including ], ], and ]—do not appear to be members of any other subfamilies of PIE, but are so poorly attested that proper classification of them is not possible. Forming an exception, ] is sufficiently well-attested to allow proposals of a particularly close affiliation with Greek, and a ] branch of Indo-European is becoming increasingly accepted.<ref>{{cite book|last=Brixhe|first=Claude|year=2008|chapter=Phrygian|editor-last=Woodard|editor-first=Roger D.|title=The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor|publisher=Cambridge University Press|page=72|isbn=9781139469333|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=J-f_jwCgmeUC&pg=PA72}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Ligorio |first1=Orsat |last2=Lubotsky |first2=Alexander |chapter=101. Phrygian |year=2018 |editor1=Jared Klein |editor2=Brian Joseph |editor3=Matthias Fritz |title=Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics |location=Berlin, Boston |publisher=De Gruyter Mouton |pages=1816–1831 |series=HSK 41.3 |doi=10.1515/9783110542431-022 |hdl=1887/63481 |isbn=9783110542431 |s2cid=242082908 |chapter-url=https://www.academia.edu/36922557}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Obrador-Cursach|first=Bartomeu|date=2019|title=On the place of Phrygian among the Indo-European languages|journal=Journal of Language Relationship|volume=17|issue=3–4|pages=239|doi=10.31826/jlr-2019-173-407|s2cid=215769896|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| Some theorists conclude that consonant clusters of the form ''TK'' would undergo a metathesis in the proto-language, resulting in {{unicode|Kþ}}, compare ] ''dagan'' "earth" with Greek ''khthōn'' "earth", from {{unicode|ǵʰðōm}}, from earlier {{unicode|*dʰǵʰoms}}, Hittite ''hartagas'' "monster", Greek ''arktos'' "bear" from {{unicode|hrkþos}} from earlier {{unicode|hrtgos}}. Both metathetized and unmetathetized forms survive in different ablaut grades of the root {{unicode|dʰégʷʰ}} "burn" (cognate to '']'', day) in Sanskrit, {{IAST|dáhati}} "is being burnt" < {{unicode|dʰégʷʰ-e-}} and {{IAST|kṣā́yat}} "burns" < {{unicode|dʰgʷʰ-éh<sub>1</sub>-}}. | |||

| == |

==Phonology== | ||

| {{Main|Proto-Indo-European phonology}} | |||

| Direct comparison, informed by the ] yields the reconstruction of three rows of ]s in PIE. | |||

| *Palatovelars, {{unicode|ḱ, ǵ, ǵʰ}} (also transcribed {{unicode|k', g', g'ʰ}} or {{unicode|k̑, g̑, g̑ʰ}} or {{unicode|k̂, ĝ, ĝʰ)}}. These were {{IPA|}}- or {{IPA|}}-like sounds which underwent a characteristic change in the ] languages; they were possibly ] ] ({{IPA|}}, {{IPA|}}) in Proto-Indo-European. | |||

| *Pure velars, {{unicode|k, g, gʰ}}. | |||

| *Labiovelars, {{unicode|kʷ, gʷ, gʷʰ}} (also transcribed {{unicode|k<sup>u̯</sup>, g<sup>u̯</sup>, g<sup>u̯h</sup>}}). Raised {{unicode|ʷ}} stands for labialization, or ] accompanying the articulation of velar sounds ({{IPA|}} is a sound similar to English ''qu'' in ''queen''). | |||

| Proto-Indo-European ] has been reconstructed in some detail. Notable features of the most widely accepted (but not uncontroversial) reconstruction include: | |||

| The ] group of languages merged the palatovelars {{unicode|ḱ, ǵ, ǵʰ}} with the plain velars {{unicode|k, g, gʰ}} while the ] group of languages merged the labiovelars {{unicode|kʷ, gʷ, gʷʰ}} with the plain velars {{unicode|k, g, gʰ}}. | |||

| *three series of ]s reconstructed as ], ], and ]d; | |||

| *] consonants that could be used ]; | |||

| *three so-called ] consonants, whose exact pronunciation is not well-established but which are believed to have existed in part based on their detectable effects on adjacent sounds; | |||

| *the ] {{IPA|/s/}} | |||

| *a ] system in which {{IPA|/e/}} and {{IPA|/o/}} were the most frequently occurring vowels. The existence of {{IPA|/a/}} as a separate phoneme is debated. | |||

| ===Notation=== | |||

| The existence of the plain velars as phonemes separate from the palatovelars and labiovelars has been disputed. In most circumstances they appear to be ]s resulting from the neutralization of the other two series in particular phonetic circumstances. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly what the circumstances of the allophony are, although it is generally accepted that neutralization occurred after {{unicode|s}} and {{unicode|u}}, and often before {{unicode|r}}. Most PIE linguists believe that all three series were distinct by late Proto-Indo-European, although a minority, including ], believe that the plain velar series was a later development of certain satem languages; this view was originally articuled by ] in 1894. Those who support the view of the threefold distinction in PIE cite evidence from ] (Holger Pedersen, '']'' 36 (1900) 277-340; Norbert Jokl, ''Mélanges linguistiques offerts à M. Holger Pedersen'' (1937) 127-161) and ] (Vittore Pisani, ''Ricerche Linguistiche'' 1 (1950) 165ff.) that they treated plain velars differently from the labiovelars in at least some circumstances, as well as the fact that ] apparently has distinct reflexes of all three series: *{{unicode|ḱ}} > ''z'' (probably {{IPA|}}); *{{unicode|k}} > ''k''; *{{unicode|kʷ}} > ''ku'' (probably {{IPA|}}) (Craig Melchert, ''Studies in Memory of Warren Cowgill'' (1987) 182–204). Kortlandt, however, disputes the significance of this evidence (''Recent developments in historical phonology'' (1978) 237-243 = ). Ultimately, this dispute may be irresoluble -- analogical developments tend to quickly obscure the original distribution of allophonic variants that have been phonemicized, and the time frame is too great and the evidence too meager to make definite conclusions as to when exactly this phonemicization happened. | |||

| ==== |

====Vowels==== | ||

| The vowels in commonly used notation are:{{sfnp|Kapović|2017|p=13}} | |||

| {{unicode|s}} (with the voiced allophone {{unicode|z}}). The "laryngeals" may have been fricatives, but there is no consensus as to their phonetic realization. There were also fricative allophones of {{unicode|t, d}}, usually transcribed {{unicode|þ, ð}}. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| ====Laryngeals==== | |||

| |+ | |||

| The symbols {{unicode|h₁, h₂, h₃}}, with cover symbol {{unicode|H}} (or {{unicode|ə₁, ə₂, ə₃}} and {{unicode|ə}}), stand for three hypothetical "]" phonemes. There is no consensus as to what these phonemes were, but it is widely accepted that {{unicode|h₂}} was probably uvular or pharyngeal, and that {{unicode|h₃}} was labialized. Commonly cited possibilities are {{IPA|ʔ ʕ ʕʷ}} and {{IPA|x χ~ħ xʷ}}; there is some evidence that {{unicode|h₁}} may have been two consonants, {{IPA|ʔ}} and {{IPA|h}}, that fell together. | |||

| !Type | |||

| !] | |||

| !] | |||

| !] | |||

| |- | |||

| ! rowspan="2" |] | |||

| !short | |||

| |{{IPA|*]}} | |||

| |{{IPA|*]}} | |||

| |- | |||

| !long | |||

| |*] | |||

| |*] | |||

| |} | |||

| ====Consonants==== | |||

| The ''] indogermanicum'' symbol {{unicode|ə}} is commonly used for a laryngeal between consonants. | |||

| The corresponding consonants in commonly used notation are:{{sfnp|Fortson|2010|loc=§3.2}}{{sfnp|Beekes|1995|loc=§11}} | |||

| ====Nasals and Liquids==== | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center" | |||

| {{unicode|r, l, m, n}}, with vocalic allophones {{unicode|r̥, l̥, m̥, n̥}}, grouped with the cover symbol ''R''. | |||

| ====Semivowels==== | |||

| {{unicode|w, y}} (also transcribed {{unicode|u̯, i̯}}) with vocalic allophones {{unicode|u, i}}. | |||

| ===Vowels=== | |||

| * '''Short ]s''' {{unicode|a, e, i, o, u}} | |||

| * '''Long vowels''' {{unicode|ā, ē, ō}}; a colon ''(:)'' is sometimes employed to indicate ] instead of the macron sign (''a:, e:, o:''). | |||

| * ''']s''' {{unicode|ai, au, āi, āu, ei, eu, ēi, ēu, oi, ou, ōi, ōu}} | |||

| *vocalic allophones of consonantal phonemes: {{unicode|u, i, r̥, l̥, m̥, n̥}}. | |||

| Other long vowels may have appeared already in the proto-language by ]: {{unicode|ī, ū, r̥̄, l̥̄, m̥̄, n̥̄}}. | |||

| It is often suggested that all {{unicode|a}} sounds (short and long) were earlier derived from an {{unicode|e}} preceded or followed by {{unicode|h₂}}, but Mayrhofer (1986: 170 ff.) has argued that PIE did in fact have {{unicode|a}} and {{unicode|ā}} phonemes independent of {{unicode|h₂}}. | |||

| ==Ablaut== | |||

| {{main|Indo-European ablaut}} | |||

| Indo-European had a characteristic general ablaut sequence that contrasted the vowel phonemes {{unicode|o/e/Ø}} through the same root. | |||

| ==Noun== | |||

| Nouns were declined for eight cases (], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]). There were three genders: masculine, feminine, and neuter. | |||

| There are two major types of declension, thematic and athematic. Thematic nominal stems are formed with a suffix ''-o-'' (in vocative ''-e'') and the stem does not undergo ]. The athematic stems are more archaic, and they are classified further by their ablaut behaviour (''acro-dynamic'', ''protero-dynamic'', ''hystero-dynamic'' and ''holo-dynamic'', after the positioning of the early PIE accent (''dynamis'') in the paradigm). | |||

| Case endings: | |||

| {| rules=all style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid darkgray;" cellpadding=3 | |||

| !rowspan="4" | | |||

| !rowspan="2" colspan="6" | '''(Beekes 1995)''' | |||

| !colspan="9" | '''(Ramat 1998)''' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| !colspan=" |

! rowspan="2" colspan="2" | Type | ||

| ! rowspan="2" | ] | |||

| !colspan="5" | '''Thematic''' | |||

| ! rowspan="2" | ] | |||

| ! colspan=3| ] | |||

| ! colspan="3" | ] | |||

| ! rowspan="6" | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! <small>]</small> | |||

| ! colspan="3" | '''Masculine and Feminine''' | |||

| ! <small>]</small> | |||

| ! colspan="3" | '''Neuter''' | |||

| ! <small>]</small> | |||

| ! colspan="3" | '''Masculine and Feminine''' | |||

| !<small>]</small> | |||

| ! colspan="2" | '''Neuter''' | |||

| ! colspan="2" |<small>] or ]</small> | |||

| ! colspan="3" | '''Masculine''' | |||

| | '''Neuter''' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! colspan="2" | ] | |||

| | '''Singular''' | |||

| | *{{PIE|m}} {{IPAslink|m}} | |||

| | '''Plural''' | |||

| | *{{PIE|n}} {{IPAslink|n}} | |||

| | '''Dual''' | |||

| | || || || | |||

| | '''Singular''' | |||

| | | |||

| | '''Plural''' | |||

| | | |||

| | '''Dual''' | |||

| | '''Singular''' | |||

| | '''Plural''' | |||

| | '''Dual''' | |||

| | '''Singular''' | |||

| | '''Plural''' | |||

| | '''Singular''' | |||

| | '''Plural''' | |||

| | '''Dual''' | |||

| | '''Singular''' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! rowspan=3| ] | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| ! <small>]</small> | |||

| | {{unicode|-s, 0}} | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|p}} {{IPAslink|p}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|t}} {{IPAslink|t}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *ḱ {{IPAslink|kʲ}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|k}} {{IPAslink|k}} | ||

| | *{{PIE|kʷ}} {{IPAslink|kʷ}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-ih₁}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-s}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-es}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-h₁e?}} | |||

| | {{unicode|0}} | |||

| | (coll.) {{unicode|-(e)h₂}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-os}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-ōs}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-oh₁(u)?}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-om}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! <small>]</small> | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | {{ |

| (*{{PIE|b}}) {{IPAslink|b}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|d}} {{IPAslink|d}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *ǵ {{IPAslink|ɡʲ}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|g}} {{IPAslink|ɡ}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|gʷ}} {{IPAslink|ɡʷ}} | ||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-ih₁}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-m̥}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-m̥s}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-h₁e?}} | |||

| | {{unicode|0}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-om}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-ons}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-oh₁(u)?}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-om}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! <small>]</small> | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | *{{PIE|bʰ}} {{IPAslink|bʱ}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-(o)s}} | |||

| | *{{PIE|dʰ}} {{IPAslink|dʱ}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-om}} | |||

| | {{ |

| *ǵʰ {{IPAslink|ɡʲʱ}} | ||

| | *{{PIE|gʰ}} {{IPAslink|ɡʱ}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-(o)s}} | |||

| | *{{PIE|gʷʰ}} {{IPAslink|ɡʷʱ}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-om}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-h₁e}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-es, -os, -s}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-ōm}} | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-os(y)o}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-ōm}} | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! colspan="2" rowspan="2" | ] | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | rowspan="2" | | |||

| | {{unicode|-(e)i}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" | *{{PIE|s}} {{IPAslink|s}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-mus}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" | || rowspan="2" | || rowspan="2" | | |||

| | {{unicode|-me}} | |||

| | *{{PIE|h₁}} {{IPAslink|h}}~{{IPAslink|ʔ}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-(e)i}} | |||

| |*{{PIE|h₂}} {{IPAslink|x}}~{{IPAslink|qː}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-mus}} | |||

| |*{{PIE|h₃}} {{IPAslink|ɣʷ}}~{{IPAslink|qʷː}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-me}} | |||

| !<small>Laryngeal Pronunciation<br />(], ])</small> | |||

| | {{unicode|-ei}} | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-ōi}} | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |{{IPAblink|ə}} | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | |

|{{IPAblink|ɐ}} | ||

| | |

|{{IPAblink|ɵ}} | ||

| !<small>] ]</small> | |||

| | {{unicode|-bʰih₁}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-(e)h₁}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-bʰi}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-bʰih₁}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-bʰi}} | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-ō}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-ōjs}} | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! rowspan="2" | ] | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| !] | |||

| | {{unicode|-(o)s}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-ios}} | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|r}} {{IPAslink|r}} | ||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-(o)s}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-ios}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-ios}} | |||

| | |

| | ||

| | |

| | ||

| | |

| | ||

| ! rowspan="3" | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| !] | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-i, 0}} | |||

| | {{ |

|*{{PIE|l}} {{IPAslink|l}} | ||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-h₁ou}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-i, 0}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-su}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-h₁ou}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-i, 0}} | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-su, -si}} | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | {{unicode|-oi}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-oisu, -oisi}} | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! colspan="2" rowspan="2" | ] | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | rowspan="2" | | |||

| | {{unicode|0}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" | | |||

| | {{unicode|-es}} | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|y}} {{IPAslink|j}} | ||

| | rowspan="2" | | |||

| | {{unicode|-m, 0}} | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|w}} {{IPAslink|w}} | ||

| | rowspan="2" | | |||

| | {{unicode|-ih₁}} | |||

| | rowspan="2" | | |||

| | | |||

| | rowspan="2" | | |||

| | {{unicode|-es}} | |||

| | |

|- | ||

| |*i {{IPAblink|i}} | |||

| | | |||

| | |

|*u {{IPAblink|u}} | ||

| !<small>Syllabic allophone{{sfnp|Kapović|2017|p=14}}</small> | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| All ]s (i.e. nasals, liquids and semivowels) can appear in ] position. The syllabic allophones of *y and *w are realized as the surface vowels *i and *u respectively.{{sfnp|Kapović|2017|p=14}} | |||

| ==Pronoun== | |||

| {{main|Proto-Indo-European pronouns}} | |||

| ===Accent=== | |||

| PIE pronouns are difficult to reconstruct due to their variety in later languages. This is especially the case for ]s. | |||

| The ] is reconstructed today as having had variable lexical stress, which could appear on any syllable and whose position often varied among different members of a paradigm (e.g. between singular and plural of a verbal paradigm). Stressed syllables received a higher pitch; therefore it is often said that PIE had a ]. The location of the stress is associated with ablaut variations, especially between full-grade vowels ({{IPA|/e/}} and {{IPA|/o/}}) and zero-grade (i.e. lack of a vowel), but not entirely predictable from it. | |||

| The accent is best preserved in ] and (in the case of nouns) ], and indirectly attested in a number of phenomena in other IE languages, such as ] in the Germanic branch. Sources for Indo-European accentuation are also the ] accentual system and ''plene'' spelling in ] cuneiform. To account for mismatches between the accent of Vedic Sanskrit and Ancient Greek, as well as a few other phenomena, a few historical linguists prefer to reconstruct PIE as a ] where each ] had an inherent tone; the sequence of tones in a word then evolved, according to that hypothesis, into the placement of lexical stress in different ways in different IE branches.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kortlandt |first=Frederik |date=1986 |title=Proto-Indo-European tones |url=https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:55314276 |journal=Journal of Indo-European Studies |pages=153–160}}</ref> | |||

| PIE had personal ]s in the ] and second person, but not the third person, where demonstratives were used instead. The personal pronouns had their own unique forms and endings, and some had two distinct stems; this is most obvious in the first person singular, where the two stems are still preserved in English ''I'' and ''me''. According to Beekes (1995), there were also two varieties for the accusative, genitive and dative cases, a stressed and an ] form. | |||

| ==Morphology== | |||

| {| rules=all style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid darkgray;" cellpadding=3 | |||

| Proto-Indo-European, like its earliest attested descendants, was a highly inflected, ]. Suffixation and ablaut were the main methods of marking inflection, both for nominals and verbs. The subject of a sentence was in the nominative case and agreed in number and person with the verb, which was additionally marked for voice, tense, aspect, and mood.<ref name="ELL - PIE Morphology">{{Cite book |title=Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics |publisher=] |year=2006 |isbn=9780080547848 |editor-last=Brown |editor-first=Keith |edition=2nd |language=en |chapter=Proto-Indo-European Morphology}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| ! colspan="4" | '''Personal pronouns (Beekes 1995)''' | |||

| ===Root=== | |||

| {{main|Proto-Indo-European root}} | |||

| Proto-Indo-European nominals and verbs were primarily composed of roots – ]-lacking ]s that carried the core ] meaning of a word. They were used to derive related words (cf. the English root "-''friend''-", from which are derived related words such as ''friendship,'' ''friendly'', ''befriend'', and newly coined words such as ''unfriend''). As a rule, roots were monosyllabic, and had the structure (s)(C)CVC(C), where the symbols C stand for consonants, V stands for a variable vowel, and optional components are in parentheses. All roots ended in a consonant and, although less certain, they appear to have started with a consonant as well.<ref name="ELL - PIE Morphology" /> | |||

| A root plus a ] formed a ], and a word stem plus an ] formed a word. Proto-Indo-European was a ], in which ]al morphemes signaled the grammatical relationships between words. This dependence on inflectional morphemes means that roots in PIE, unlike those in English, were rarely used without affixes.{{sfnp|Fortson|2010|loc=§4.2, §4.20}} | |||

| ===Ablaut=== | |||

| {{main|Indo-European ablaut}} | |||

| Many morphemes in Proto-Indo-European had short ''e'' as their inherent vowel; the ] is the change of this short ''e'' to short ''o'', long ''e'' (ē), long ''o'' (''ō''), or no vowel. The forms are referred to as the "ablaut grades" of the morpheme—the ''e''-grade, ''o''-grade, zero-grade (no vowel), etc. This variation in vowels occurred both within ] (e.g., different grammatical forms of a noun or verb may have different vowels) and ] (e.g., a verb and an associated abstract ] may have different vowels).{{sfnp|Fortson|2010|pp=73–74}} | |||

| Categories that PIE distinguished through ablaut were often also identifiable by contrasting endings, but the loss of these endings in some later Indo-European languages has led them to use ablaut alone to identify grammatical categories, as in the Modern English words ''sing'', ''sang'', ''sung''. | |||

| ===Noun=== | |||

| ] were probably declined for eight or nine cases:{{sfnp|Fortson|2010|p=102}} | |||

| *]: marks the ] of a verb. Words that follow a linking verb (]) and restate the subject of that verb also use the nominative case. The nominative is the dictionary form of the noun. | |||

| *]: used for the ] of a ]. | |||

| *]: marks a ] as modifying another noun. | |||

| *]: used to indicate the indirect object of a transitive verb, such as ''Jacob'' in ''Maria gave Jacob a drink''. | |||

| *]: marks the ''instrument'' or means by, or with, which the subject achieves or accomplishes an action. It may be either a physical object or an abstract concept. | |||

| *]: used to express motion away from something. | |||

| *]: expresses location, corresponding vaguely to the English prepositions ''in'', ''on'', ''at'', and ''by''. | |||

| *]: used for a word that identifies an addressee. A ] is one of direct address where the identity of the party spoken to is set forth expressly within a sentence. For example, in the sentence, "I don't know, John", ''John'' is a vocative expression that indicates the party being addressed. | |||

| *]: used as a type of ] that expresses movement towards something. It was preserved in Anatolian (particularly Old Hittite), and fossilized traces of it have been found in Greek. It is also present in Tocharian.<ref>{{Citation |last=Pinault |first=Georges-Jean |title=Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics |chapter=76. The morphology of Tocharian |date=2017-10-23 |chapter-url=https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9783110523874-031/html |pages=1335–1352 |access-date=2023-03-08 |publisher=De Gruyter Mouton |language=en |doi=10.1515/9783110523874-031 |isbn=978-3-11-052387-4}}</ref> Its PIE shape is uncertain, with candidates including ''*-h<sub>2</sub>(e)'', ''*-(e)h<sub>2</sub>'', or ''*-a''.{{sfnp|Fortson|2010|pp=102, 105}} | |||

| Late Proto-Indo-European had three ]s: | |||

| * masculine | |||

| * feminine | |||

| * neuter | |||

| This system is probably derived from an older two-gender system, attested in Anatolian languages: ] (or ]) and neuter (or inanimate) gender. The feminine gender only arose in the later period of the language.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Sanskrit Language|last=Burrow|first=T|year=1955|publisher=Motilal Banarsidass Publ. |isbn=81-208-1767-2}}</ref> Neuter nouns collapsed the nominative, vocative and accusative into a single form, the plural of which used a special ] suffix {{wt|ine-pro|-h₂|*-h<sub>2</sub>}} (manifested in most descendants as ''-a''). This same collective suffix in extended forms {{wt|ine-pro|-éh₂|*-eh<sub>2</sub>}} and {{wt|ine-pro|-ih₂|*-ih<sub>2</sub>}} (respectively on thematic and athematic nouns, becoming ''-ā'' and ''-ī'' in the early daughter languages) became used to form feminine nouns from masculines. | |||

| All nominals distinguished three ]: | |||

| * singular | |||

| * dual | |||

| * plural | |||

| These numbers were also distinguished in verbs (see ]), requiring ] with their subject nominal. | |||

| ===Pronoun=== | |||

| ] are difficult to reconstruct, owing to their variety in later languages. PIE had personal ]s in the first and second ], but not the third person, where ]s were used instead. The personal pronouns had their own unique forms and endings, and some had ]; this is most obvious in the first person singular where the two stems are still preserved in English ''I'' and ''me''. There were also two varieties for the accusative, genitive and dative cases, a stressed and an ] form.<ref name="beekes">{{cite book|last=Beekes|first=Robert|title=Comparative Indo-European linguistics: an introduction|date=1995|publisher=J. Benjamins Publishing Company|location=Amsterdam|isbn=978-1556195044|pages=147, 212–217, 233, 243}}</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center;" | |||

| |+ Personal pronouns<ref name=beekes/> | |||

| ! rowspan="2" | Case | |||

| ! colspan="2" | First person | |||

| ! colspan="2" | Second person | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! Singular | |||

| | | |||

| ! Plural | |||

| ! colspan="2" | '''First person''' | |||

| ! Singular | |||

| ! colspan="2" | '''Second person''' | |||

| ! Plural | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! ] | |||

| | | |||

| | *{{PIE|h₁eǵ(oH/Hom)}} | |||

| | '''Singular''' | |||

| | *{{PIE|wei}} | |||

| | '''Plural''' | |||

| | *{{PIE|tuH}} | |||

| | '''Singular''' | |||

| | *{{PIE|yuH}} | |||

| | '''Plural''' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! ] | |||

| | *{{PIE|h₁mé}}, *{{PIE|h₁me}} | |||

| | {{unicode|h₁eǵ(oH/Hom)}} | |||

| | *{{PIE|n̥smé}}, *{{PIE|nōs}} | |||

| | {{unicode|wei}} | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|twé}} | ||

| | *{{PIE|usmé}}, *{{PIE|wōs}} | |||

| | {{unicode|yuH}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! ] | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|h₁méne}}, *{{PIE|h₁moi}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|n̥s(er)o-}}, *{{PIE|nos}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|tewe}}, *{{PIE|toi}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|yus(er)o-}}, *{{PIE|wos}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! ] | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|h₁méǵʰio}}, *{{PIE|h₁moi}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|n̥smei}}, *{{PIE|n̥s}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|tébʰio}}, *{{PIE|toi}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|usmei}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! ] | |||

| | *{{PIE|h₁moí}} | |||

| | {{unicode|h₁méǵʰio, h₁moi}} | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|n̥smoí}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|toí}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|usmoí}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! ] | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|h₁med}} | ||

| | *{{PIE|n̥smed}} | |||

| | ? | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|tued}} | ||

| | *{{PIE|usmed}} | |||

| | ? | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! ] | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|h₁moí}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|n̥smi}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|toí}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|usmi}} | ||

| |- | |||

| | ''']''' | |||

| | {{unicode|h₁moí}} | |||

| | {{unicode|nsmi}} | |||

| | {{unicode|toí}} | |||

| | {{unicode|usmi}} | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| ===Verb===<!-- This section is linked from ] --> | |||

| As for demonstratives, Beekes (1995) tentatively reconstructs a system with only two pronouns: {{unicode|so/seh₂/tod}} "this, that" and {{unicode|h₁e/ (h₁)ih₂/(h₁)id}} "the (just named)" (]). He also postulates three adverbial particles {{unicode|ḱi}} "here", {{unicode|h₂en}} "there" and {{unicode|h₂eu}} "away, again", from which demonstratives were constructed in various later languages. | |||

| ], like the nouns, exhibited an ablaut system. | |||

| The most basic categorisation for the reconstructed Indo-European verb is ]. Verbs are classed as: | |||

| There was also an interrogative/indefinite pronoun with the stem {{unicode|kʷe-/kʷi-}} (adjectival {{unicode|kʷo-}}), and probably a relative pronoun with the stem {{unicode|yo-}}. A third-person reflexive pronoun {{unicode|se}} (acc.), {{unicode|sewe, sei}} (gen.), {{unicode|sébʰio, soi}} (dat.), parallel to the first and second person singular personal pronouns, also existed, as well as possessive pronominal adjectives. | |||

| *]: verbs that depict a state of being | |||

| *]: verbs depicting ongoing, habitual or repeated action | |||

| *]: verbs depicting a completed action or actions viewed as an entire process. | |||

| Verbs have at least four ]s: | |||

| *]: indicates that something is a statement of fact; in other words, to express what the speaker considers to be a known state of affairs, as in ]s. | |||

| *]: forms commands or requests, including the giving of prohibition or permission, or any other kind of advice or exhortation. | |||

| *]: used to express various states of unreality such as wish, emotion, possibility, judgment, opinion, obligation, or action that has not yet occurred | |||

| *]: indicates a wish or hope. It is similar to the ] and is closely related to the ]. | |||

| Verbs had two ]s: | |||

| * ]: used in a clause whose subject expresses the main verb's ]. | |||

| *]: for the ] and the ]. | |||

| Verbs had three ]s: first, second and third. | |||

| Verbs had three ]s: | |||

| PIE had a separate set of endings for pronouns; many of these were later borrowed as nominal endings. | |||

| *singular | |||

| *]: referring to precisely two of the entities (objects or persons) identified by the noun or pronoun. | |||

| *]: a number other than singular or dual. | |||

| Verbs were probably marked by a highly developed system of ]s, one for each combination of tense and voice, and an assorted array of ]s and adjectival formations. | |||

| ==Verb== | |||

| The following table shows a possible reconstruction of the PIE verb endings from Sihler, which largely represents the current consensus among Indo-Europeanists. | |||

| The Indo-European verb system is complex and exhibits a system of ], as is still visible in the Germanic languages (among others)—for example, the vowel in the English verb ''to sing'' varies according to the conjugation of the verb: ''s'''i'''ng'', ''s'''a'''ng'', and ''s'''u'''ng''. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center;" | |||

| ! colspan="2" rowspan="2" | Person | |||

| The system is clearly represented in ] and ], two of the most completely attested of the early daughter languages of Proto-Indo-European. | |||

| ! colspan="2"|'''Sihler (1995)'''<ref name="sihler">{{cite book|author-link1=Andrew Sihler|last1=Sihler|first1=Andrew L.|title=New comparative grammar of Greek and Latin|date=1995|publisher=Oxford Univ. Press|location=New York u. a.|isbn=0-19-508345-8}}</ref> | |||

| ]s have at least four ] (], ], ] and ], as well as possibly the ], reconstructible from Vedic Sanskrit), two ] (] and ]), as well as three ] (], ] and ]) and three ] (], ] and ]). Verbs are conjugated in at least three "tenses" (], ], and ]), which actually have primarily ]ual value. Indicative forms of the ] and (less likely) the ] may have existed. Verbs were also marked by a highly developed system of ]s, one for each combination of tense and mood, and an assorted array of ]s and adjectival formations. | |||

| A number of secondary forms could be created, such as the ], ] and ]; technically these were part of the ] system rather than the ]al system, as they existed only for certain verbs and did not necessarily have completely predictable meanings (compare the remnants of causative constructions in English – ''to fall'' vs. ''to fell'', ''to sit'' vs. ''to set'', ''to rise'' vs. ''to raise'' and ''to rear''). The above-mentioned verbal nouns and adjectives were likewise part of the derivational system (compare the formation of verbal nouns in ], using ''-tion'', ''-ence'', ''-al'', etc.), and it appears that the same originally applied to the different verb tenses. Some verbs in ] still have perfect tenses with unpredictable meanings – from ''histēmi'' "I set, I cause to stand": ''hestēka'' "I am standing"; from ''mimnēiskō'' "I remind": ''memnēmai'' "I remember"; from ''peithō'' "I persuade": ''pepoitha'' "I trust" as well as ''pepeika'' "I have persuaded"; from ''phūō'' "I produce": ''pephūka'' "I am (by nature)". The present tense in Ancient Greek and in Sanskrit is formed by the unpredictable addition of one of a number of suffixes (at least 10, in Sanskrit; at least 6, in Greek) to the verbal root; the aorist and perfect are likewise formed, in each case from their own set of suffixes (7 for the Sanskrit aorist, at least 3 for the Greek aorist), with little or no relation between the suffixes used in one tense and in another. (The perfect tense in ] is likewise unpredictable, formed in one of at least six ways.) Sometimes more than one suffix can be applied to the same root, producing different present, aorist and/or perfect stems for the same verb, sometimes with the same meaning, sometimes with different meanings (see the above example with the Greek verb ''peithō''). All of this suggests that the various tenses were originally independent lexical formations, similarly to the way that verbal nouns in English are formed unpredictably in English from different suffixes, sometimes with two or more formations that may differ in meaning: ''reference'' vs. ''referral'', ''transference'' vs. ''transferral'' vs. ''transfer'', ''recitation'' vs. ''recital'', ''delivery'' vs. ''deliverance'' etc. (This is more understandable if one considers that the original meaning of these tenses was ]ual.) Only later, and gradually, were these various forms combined into a single set of inflectional paradigms. ] had still not completed the process, and even ] has places where the old unorganized system still shows through. (As a result, verbs in Vedic Sanskrit have the appearance at first glance of a fantastically complex and disorganized system, with numerous redundancies combined with inexplicable holes. The system of PIE must have looked even more strongly like this.) | |||

| The primary distinction in verbs between the different ways of forming the present tenses was between thematic ({{unicode|ō}}) classes, with a "thematic" vowel {{unicode|o}} or {{unicode|e}} before the endings, and athematic ({{unicode|mi}}) classes, with endings added directly to the root. The endings themselves differed somewhat, at the very least in the first-person singular, with the endings as indicated ({{unicode|ō}} vs. {{unicode|mi}}). Traditional accounts say that this is the only form where the endings differed, except for the presence or absence of the thematic vowel; but some newer researchers, e.g. Beekes (1995), have proposed a totally different set of thematic endings, based primarily on Greek and ]. These proposals are still controversial, however. | |||

| {| rules=all style="text-align: center; border: 1px solid darkgray;" cellpadding=3 | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| ! colspan="2" | '''Buck 1933''' | |||

| ! colspan="2" | '''Beekes 1995''' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! ] | |||

| | | |||

| ! ] | |||

| | | |||

| | '''Athematic''' | |||

| | '''Thematic''' | |||

| | '''Athematic''' | |||

| | '''Thematic''' | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! rowspan=3 | ] | |||

| ! ] | |||

| | '''1st''' | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|-mi}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|-oh₂}} | ||

| | {{unicode|-mi}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-oH}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! 2nd | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|-si}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|-esi}} | ||

| | {{unicode|-si}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-eh₁i}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! 3rd | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|-ti}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|-eti}} | ||

| | {{unicode|-ti}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-e}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! rowspan=3 | Dual | |||

| ! 1st | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|-wos}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|-owos}} | ||

| | {{unicode|-mes}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-omom}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! 2nd | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|-th₁es}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|-eth₁es}} | ||

| | {{unicode|-th₁e}} | |||

| | {{unicode|-eth₁e}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! 3rd | |||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|-tes}} | ||

| | {{ |

| *{{PIE|-etes}} | ||

| |- | |||

| | {{unicode|-nti}} | |||

| ! rowspan=3 | Plural | |||

| | {{unicode|-o}} | |||

| ! 1st | |||

| | *{{PIE|-mos}} | |||

| | *{{PIE|-omos}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 2nd | |||

| | *{{PIE|-te}} | |||

| | *{{PIE|-ete}} | |||

| |- | |||

| ! 3rd | |||

| | *{{PIE|-nti}} | |||

| | *{{PIE|-onti}} | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| ===Numbers=== | |||

| The original meanings of the past tenses (aorist, perfect and imperfect) are often assumed to match their meanings in Greek. That is, the aorist represents a single action in the past, viewed as a discrete event; the imperfect represents a repeated past action or a past action viewed as extending over time, with the focus on some point in the middle of the action; and the perfect represents a present state resulting from a past action. This corresponds, approximately, to the English distinction between "I ate", "I was eating" and "I have eaten", respectively. (Note that the English "I have eaten" often has the meaning, or at least the strong implication, of "I am in the state resulting from having eaten", in other words "I am now full". Similarly, "I have sent the letter" means approximately "The letter is now (in the state of having been) sent". However, the Greek, and presumably PIE, perfect, more strongly emphasizes the ''state'' resulting from an action, rather than the action itself, and can shade into a present tense.) | |||

| ] are generally reconstructed as follows: | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center;" | |||

| Note that in Greek the difference between the present, aorist and perfect tenses when used outside of the indicative (that is, in the subjunctive, optative, imperative, infinitive and participles) is almost entirely one of ], not of tense. That is, the aorist refers to a simple action, the present to an ongoing action, and the perfect to a state resulting from a previous action. An aorist infinitive or imperative, for example, does ''not'' refer to a past action, and in fact for many verbs (e.g. "kill") would likely be more common than a present infinitive or imperative. (In some participial constructions, however, an aorist participle can have either a tensal or aspectual meaning.) It is assumed that this distinction of aspect was the original significance of the PIE "tenses", rather than any actual tense distinction, and that tense distinctions were originally indicated by means of adverbs, as in ]. However, it appears that by late PIE, the different tenses had already acquired a tensal meaning in particular contexts, as in Greek, and in later Indo-European languages this became dominant. | |||

| !Number | |||

| !'''Sihler'''<ref name="sihler"/> | |||

| The meanings of the three tenses in the oldest ], however, differs somewhat from their meanings in Greek, and thus it is not clear whether the PIE meanings corresponded exactly to the Greek meanings. In particular, the Vedic imperfect had a meaning that was close to the Greek aorist, and the Vedic aorist had a meaning that was close to the Greek perfect. Meanwhile, the Vedic perfect was often indistinguishable from a present tense (Whitney 1924). In the moods other than the indicative, the present, aorist and perfect were almost indistinguishable from each other. (The lack of semantic distinction between different grammatical forms in a literary language often indicates that some of these forms no longer existed in the spoken language of the time. In fact, in ], the subjunctive dropped out, as did all tenses of the optative and imperative other than the present; meanwhile, in the indicative the imperfect, aorist and perfect became largely interchangeable, and in later Classical Sanskrit, all three could be freely replaced by a participial construction. All of these developments appear to reflect changes in spoken ]; among the past tenses, for example, only the aorist survived into early Middle Indo-Aryan, which was later displaced by a participial past tense.) | |||

| == Numbers == | |||

| {{main|Proto-Indo-European numerals}} | |||

| The numbers are generally reconstructed as follows: | |||

| {| | |||

| | | |||

| |Sihler 1995, 402–24 | |||

| |Beekes 1995, 212–16 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |one | |one | ||

| |*{{PIE|(H)óynos}}/*{{PIE|(H)óywos}}/*{{PIE|(H)óyk(ʷ)os}}; *{{PIE|sḗm}} (full grade), *{{PIE|sm̥-}} ''(zero grade)'' | |||

| |*{{unicode|Hoi-no-/*Hoi-wo-/*Hoi-k(ʷ)o-; *sem-}} | |||

| |*{{unicode|Hoi(H)nos}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |two | |two | ||

| |*{{PIE|d(u)wóh₁}} (full grade), *{{PIE|dwi-}} ''(zero grade)'' | |||

| |*{{unicode|d(u)wo-}} | |||

| |*{{unicode|duoh₁}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |three | |three | ||

| |*{{ |

|*{{PIE|tréyes}} (full grade), *{{PIE|tri-}} ''(zero grade)'' | ||

| |*{{unicode|treies}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |four | |four | ||

| |*{{ |

|*{{PIE|kʷetwóres}} (''o''-grade), *{{PIE|kʷ(e)twr̥-}} ''(zero grade)''<br />(''see also the ]'') | ||

| |*{{unicode|kʷetuōr}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |five | |five | ||

| |*{{ |

|*{{PIE|pénkʷe}} | ||

| |*{{unicode|penkʷe}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |six | |six | ||

| |*{{ |

|*{{PIE|s(w)éḱs}}; ''originally perhaps'' *{{PIE|wéḱs}}, with ''*s-'' under the influence of *{{PIE|septḿ̥}} | ||

| |*{{unicode|(s)uéks}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |seven | |seven | ||

| |*{{ |

|*{{PIE|septḿ̥}} | ||

| |*{{unicode|séptm}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |eight | |eight | ||

| |*{{PIE|oḱtṓ(w)}} ''or'' *{{PIE|h₃eḱtṓ(w)}} | |||

| |*{{unicode|oḱtō}}, *{{unicode|oḱtou}} or *{{unicode|h₃eḱtō}}, *{{unicode|h₃eḱtou}} | |||

| |*{{unicode|h₃eḱteh₃}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |nine | |nine | ||

| |*{{ |

|*{{PIE|h₁néwn̥}} | ||

| |*{{unicode|(h₁)néun}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |ten | |ten | ||

| |*{{ |

|*{{PIE|déḱm̥(t)}} | ||

| |*{{unicode|déḱmt}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |twenty | |||

| |*{{unicode|wīḱm̥t-}}; originally perhaps *{{unicode|widḱomt-}} | |||

| | *{{unicode|duidḱmti}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |thirty | |||

| |*{{unicode|trīḱomt-}}; originally perhaps *{{unicode|tridḱomt-}} | |||

| | *{{unicode|trih₂dḱomth₂}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |forty | |||

| |*{{unicode|kʷetwr̥̄ḱomt-}}; originally perhaps *{{unicode|kʷetwr̥dḱomt-}} | |||

| |*{{unicode|kʷeturdḱomth₂}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |fifty | |||

| |*{{unicode|penkʷēḱomt-}}; originally perhaps *{{unicode|penkʷedḱomt-}} | |||

| |*{{unicode|penkʷedḱomth₂}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |sixty | |||

| |*{{unicode|s(w)eḱsḱomt-}}; originally perhaps *{{unicode|weḱsdḱomt-}} | |||

| |*{{unicode|ueksdḱomth₂}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |seventy | |||

| |*{{unicode|septm̥̄ḱomt-}}; originally perhaps *{{unicode|septm̥dḱomt-}} | |||

| |*{{unicode|septmdḱomth₂}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |eighty | |||

| |*{{unicode|oḱtō(u)ḱomt-}}; originally perhaps *{{unicode|h₃eḱto(u)dḱomt-}} | |||

| |*{{unicode|h₃eḱth₃dḱomth₂}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |ninety | |||

| |*{{unicode|(h₁)newn̥̄ḱomt-}}; originally perhaps *{{unicode|h₁newn̥dḱomt-}} | |||

| |*{{unicode|h₁neundḱomth₂}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |hundred | |||

| |*{{unicode|ḱm̥tom}}; originally perhaps *{{unicode|dḱm̥tom}} | |||

| |*{{unicode|dḱmtóm}} | |||

| |- | |||

| |thousand | |||

| |*{{unicode|ǵheslo-}}, *{{unicode|tusdḱomti}} | |||

| |*{{unicode|ǵʰes-l-}} | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| Rather than specifically 100, *{{PIE|''ḱm̥tóm''}} may originally have meant "a large number".<ref>{{Citation|last=Lehmann|first=Winfried P|title=Theoretical Bases of Indo-European Linguistics|year=1993|pages=|location=London|publisher=Routledge|isbn=0-415-08201-3|url=https://archive.org/details/theoreticalbases0000lehm/page/252}}</ref> | |||

| Lehmann (1993, 252-255) believes that the numbers greater than ten were constructed separately in the dialects groups and that *{{unicode|ḱm̥tóm}} originally meant "a large number" rather than specifically "one hundred." | |||

| == |

===Particle=== | ||

| ] were probably used both as ]s and as ]. These postpositions became prepositions in most daughter languages. | |||

| Reconstructed particles include for example, *{{PIE|''upo''}} "under, below"; the ] *{{PIE|''ne''}}, *{{PIE|''mē''}}; the ] *{{PIE|''kʷe''}} "and", *{{PIE|''wē''}} "or" and others; and an ], *{{PIE|''wai!''}}, expressing woe or agony. | |||

| As PIE was spoken by a prehistoric society, no genuine sample texts are available, but since the 19th century modern scholars have made various attempts to compose example texts for purposes of illustration. These texts are educated guesses at best; ] in 1969 rightly observes that in spite of its 150 years' history, comparative linguistics is not in the position to reconstruct a single well-formed sentence in PIE. Nevertheless, such texts do have the merit of giving an impression of what a coherent utterance in PIE might have sounded like. | |||

| ===Derivational morphology=== | |||

| Published PIE sample texts: | |||

| Proto-Indo-European employed various means of deriving words from other words, or directly from verb roots. | |||

| *] (''{{unicode|Avis akvasas ka}}'') by ] (1868), modernized by ] (1939) and ] and ] (1979) | |||

| *] (''{{unicode|rēḱs deiwos-kʷe}}'') by S. K. Sen, E. P. Hamp et al. (1994) | |||

| ====Internal derivation==== | |||

| Internal derivation was a process that derived new words through changes in accent and ablaut alone. It was not as productive as external (affixing) derivation, but is firmly established by the evidence of various later languages. | |||

| =====Possessive adjectives===== | |||

| Possessive or associated adjectives were probably created from nouns through internal derivation. Such words could be used directly as adjectives, or they could be turned back into a noun without any change in morphology, indicating someone or something characterised by the adjective. They were probably also used as the second elements in compounds. If the first element was a noun, this created an adjective that resembled a present participle in meaning, e.g. "having much rice" or "cutting trees". When turned back into nouns, such compounds were ]s or semantically resembled ]s. | |||

| In thematic stems, creating a possessive adjective seems to have involved shifting the accent one syllable to the right, for example:<ref name="Jay Jasanoff 21">{{cite book|author=Jay Jasanoff|title=The Prehistory of the Balto-Slavic Accent|page=21|author-link=Jay Jasanoff}}</ref> | |||

| * ''*tómh₁-o-s'' "slice" (Greek ''tómos'') > ''*tomh₁-ó-s'' "cutting" (i.e. "making slices"; Greek ''tomós'') > ''*dr-u-tomh₁-ó-s'' "cutting trees" (Greek ''drutómos'' "woodcutter" with irregular accent). | |||

| * ''*wólh₁-o-s'' "wish" (Sanskrit ''vára-'') > ''*wolh₁-ó-s'' "having wishes" (Sanskrit ''vará-'' "suitor"). | |||

| In athematic stems, there was a change in the accent/ablaut class. The reconstructed four classes followed an ordering in which a derivation would shift the class one to the right:<ref name="Jay Jasanoff 21"/> | |||

| : acrostatic → proterokinetic → hysterokinetic → amphikinetic | |||

| The reason for this particular ordering of the classes in derivation is not known. Some examples: | |||