| Revision as of 15:10, 27 June 2006 editInvisifan (talk | contribs)3,292 edits rvv (several levels)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:43, 17 December 2024 edit undoNyakase (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers9,573 editsm Reverted edits by 138.43.98.230 (talk) (HG) (3.4.13)Tags: Huggle Rollback | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|French Impressionist artist (1834–1917)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{redirect|Degas}} | |||

| '''Edgar Degas''' (], ] – ], ]) was a French artist famous for his work in ], ], and ]. He is also regarded as one of the fathers of ]. | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2021}} | |||

| {{Infobox artist | |||

| | name = Edgar Degas | |||

| | image = Self-portrait by Edgar Degas.jpg | |||

| | image_size = | |||

| | caption = Self-portrait (''Degas Saluant''), 1863 | |||

| | birth_name = Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|df=yes|1834|7|19}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], Kingdom of France | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|df=yes|1917|9|27|1834|7|19}} | |||

| | death_place = Paris, France | |||

| | field = Painting, sculpture, drawing | |||

| | training = | |||

| | movement = ] | |||

| | works = {{plainlist| | |||

| * {{Nowrap|'']'' (1858–1867)}} | |||

| * '']'' (1871–1874) | |||

| * '']'' (1875–1876) | |||

| * '']'' (1886) | |||

| }} | |||

| | patrons = | |||

| | awards = | |||

| | module = {{Infobox person|child=yes | |||

| | signature = Degas autograph.png}} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Edgar Degas''' ({{IPAc-en|uk|ˈ|d|eɪ|ɡ|ɑː}}, {{IPAc-en|us|d|eɪ|ˈ|ɡ|ɑː|,_|d|ə|ˈ|ɡ|ɑː}};<ref>{{cite RDPCE|page=330}}; {{cite book |last=Bollard |first=John K. |title=Pronouncing Dictionary of Proper Names |url=https://archive.org/details/pronouncingdicti00boll |url-access=registration |publisher=Omnigraphics, Inc. |location=Detroit, MI |edition=2nd |year=1998 |page= |isbn=978-0-7808-0098-4}}</ref><ref>{{cite LPD|3}}</ref> born '''Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas''', {{IPA|fr|ilɛːʁ ʒɛʁmɛ̃ ɛdɡaʁ də ɡa|lang}}; 19 July 1834{{spnd}}27 September 1917) was a ] ] artist famous for his pastel drawings and oil paintings. | |||

| Degas also produced ] ]s, ], and drawings. Degas is especially identified with the subject of dance; more than half of his works depict dancers.<ref>, Smithsonian Magazine, April 2003</ref> Although Degas is regarded as one of the founders of ], he rejected the term, preferring to be called a ],<ref name="Gordon31">Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 31</ref> and did not paint outdoors as many Impressionists did. | |||

| Degas was a superb ], and particularly masterly in depicting movement, as can be seen in his rendition of dancers and bathing female ]s. In addition to ballet dancers and bathing women, Degas painted ]s and racing ], as well as portraits. His ]s are notable for their psychological complexity and their portrayal of human isolation.<ref>Brown 1994, p. 11</ref> | |||

| At the beginning of his career, Degas wanted to be a ], a calling for which he was well prepared by his rigorous academic training and close study of classical Western art. In his early thirties he changed course, and by bringing the traditional methods of a history painter to bear on contemporary subject matter, he became a classical painter of modern life.<ref>Turner 2000, p. 139</ref> | |||

| ==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

| ] | |||

| Throughout his life, Degas had the opportunity to live in many ways, to live many lives. These lives would shape him, and shape his work to reflect true life. He was born on July 19, 1834, in ], ] to Celestine Musson de Gas, and Augustin de Gas, a ]. The de Gas family was moderately wealthy (Mannering 5). At age 11, Degas began his schooling, and started down the road of art with enrollment in the Lycee Louis Grand (Cannaday 930). | |||

| Degas was born in ], ], into a moderately wealthy family. He was the oldest of five children of Célestine Musson De Gas, a ] from ], ], and Augustin De Gas, a banker.<ref>Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 86.</ref> His maternal grandfather Germain Musson was born in ], ], of French descent, and had settled in New Orleans in 1810.<ref>{{cite book |last=Brown |first=Marilyn R |title=Degas and the Business of Art |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vWTZpFv4m9QC&pg=PA15 |access-date=29 September 2014 |year=1994 |page=14 |publisher=Penn State Press |isbn=0-271-04431-4}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Degas began to paint seriously early in life; by eighteen he had turned a room in his home into an artist's studio, but he was expected to go to ] as were most aristocratic young men. Degas, however, had other plans and dropped out of law school at age 20. After ending his law career, he studied drawing with ] under whose guidance he flourished, following the style of ] (Cannaday 930-931). Degas did, in 1855, meet Ingres (Benedek "Chronology.") and was advised by him to "draw lines"(Cannaday 931). In that same year, Degas received admission to the ] (Benedek "Chronology."). The next year, Degas traveled to ], where he saw the paintings of ], ], and other artists of the ] (Cannaday 931-932). | |||

| Degas (he adopted this less grandiose spelling of his family name when he became an adult)<ref>The family's ancestral name was Degas. Jean Sutherland Boggs explains that De Gas was the spelling, "with some pretensions, used by the artist's father when he moved to Paris to establish a French branch of his father's Neapolitan bank." While Edgar Degas's brother René adopted the still more aristocratic de Gas, the artist reverted to the original spelling, Degas, by the age of thirty. Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 98.</ref> began his schooling at age eleven, enrolling in the ].<ref>Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 86</ref> His mother died when he was thirteen, and the main influences on him for the remainder of his youth were his father and several unmarried uncles.<ref>Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 16</ref> | |||

| Degas began to paint early in life. By the time he graduated from the Lycée with a '']'' in literature in 1853, at age 18, he had turned a room in his home into an artist's studio. Upon graduating, he registered as a copyist in the ], but his father expected him to go to ]. Degas duly enrolled at the Faculty of Law of the ] in November 1853 but applied little effort to his studies. | |||

| In 1855, he met ], whom he revered and whose advice he never forgot: "Draw lines, young man, and still more lines, both from life and from memory, and you will become a good artist."<ref>Werner 1969, p. 14</ref> In April of that year Degas was admitted to the ]. He studied drawing there with ], under whose guidance he flourished, following the style of Ingres.<ref>Canaday 1969, p. 930–931</ref> | |||

| In July 1856, Degas traveled to ], where he would remain for the next three years. In 1858, while staying with his aunt's family in ], he made the first studies for his early masterpiece '']''. He also drew and painted numerous copies of works by ], ], ], and other ] artists, but—contrary to conventional practice—he usually selected from an altarpiece a detail that had caught his attention: a secondary figure, or a head which he treated as a portrait.<ref>Dunlop 1979, p. 19</ref> | |||

| ==Artistic career== | ==Artistic career== | ||

| Upon his return to France in 1859, Degas moved into a Paris studio large enough to permit him to begin painting ''The Bellelli Family''—an imposing canvas he intended for exhibition in the ], although it remained unfinished until 1867. He also began work on several ]s: ''Alexander and Bucephalus'' and ''The Daughter of Jephthah'' in 1859–60; ''Sémiramis Building Babylon'' in 1860; and '']'' around 1860.<ref>Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 43</ref> In 1861, Degas visited his childhood friend Paul Valpinçon in ], and made the earliest of his many studies of horses.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ouest-france.fr/normandie/le-chateau-en-vente-pour-7-millions-deuros-1496557|title=Le château en vente pour 7 millions d'euros|date=23 February 2013|website=Ouest-France.fr}}</ref> He exhibited at the Salon for the first time in 1865, when the jury accepted his painting ''Scene of War in the Middle Ages'', which attracted little attention.<ref>Thomson 1988, p. 48</ref> | |||

| After returning from Italy, Degas copied paintings at the ], but lived a mostly uneventful life, until 1865 when some of his works were accepted in the ]. During the next five years, Degas had additional works accepted in the Salon, and gradually gained respect in the world of conventional art (Benedek "Chronology."). In 1870, Degas's life was changed by the outbreak of the ]. During the war, Degas served in the National Guard to defend Paris (Mannering 6), allowing little time for painting. | |||

| Although he exhibited annually in the Salon during the next five years, he submitted no more history paintings, and his '']'' (Salon of 1866) signaled his growing commitment to contemporary subject matter. The change in his art was influenced primarily by the example of ], whom Degas had met in 1864 (while both were copying the same ] portrait in the Louvre, according to a story that may be apocryphal).<ref>Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 23</ref> | |||

| Following the war, Degas visited his brother, Rene, in ] and produced a number of works before returning to Paris in 1873 (Mannering 6). Soon after his return, in 1874, Degas helped to organize an art show that became known as the ] (Benedek "Chronology."). The Impressionists held seven additional shows, the last in 1886, and Degas showed his work in all but one (Mannering 6-7). Also showing works in these exhibitions was Degas's "friend and rival"(Mannering 5), ], who helped shaped the works of Degas(Mannering 5). At around the same time, Degas also became an amateur ], both for pleasure, and in order to accurately capture action for painting (Hartt 365). | |||

| Upon the outbreak of the ] in 1870, Degas enlisted in the ], where his partaking in the defense of Paris left him little time for painting. During rifle training his eyesight was found to be defective, and for the rest of his life his eye problems were a constant worry to him.<ref name="Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 29">Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 29</ref> | |||

| Degas also had the opportunity, or perhaps curse, of living without monetary security. This occurred after the death of his father, when various debts forced him to sell his collection of art, live more modestly, and depend on his artwork for income (Cannaday 936-937). As the years passed, Degas became isolated due, in part, to his belief "that a painter could have no personal life."(Cannaday 929). As a result of this, he also never married and spent the last years of his life "aimlessly wandering the streets of Paris"(Mannering 7) before dying in 1917. | |||

| ]'', 1873]] | |||

| After the war, Degas began in 1872 an extended stay in ], where his brother René and a number of other relatives lived. Staying at the home of his Creole uncle, Michel Musson, on ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.degaslegacy.com/4degasauntanduncle.html |title=Michael Musson and Odile Longer: Degas' aunt and uncle in New Orleans |publisher=Degaslegacy.com |date=30 March 1973 |access-date=18 March 2013}}</ref> Degas produced a number of works, many depicting family members. One of Degas's New Orleans works, '']'', garnered favorable attention back in France, and was his only work purchased by a museum (the ]) during his lifetime.<ref>Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 202</ref> | |||

| Degas returned to Paris in 1873 and his father died the following year, whereupon Degas learned that his brother René had amassed enormous business debts. To preserve his family's reputation, Degas sold his house and an art collection he had inherited, and used the money to pay off his brother's debts. Dependent for the first time in his life on sales of his artwork for income, he produced much of his greatest work during the decade beginning in 1874.<ref name="auto1">Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 33</ref> Disenchanted by now with the Salon, he instead joined a group of young artists who were organizing an independent exhibiting society. The group soon became known as the Impressionists. | |||

| Between 1874 and 1886, they mounted eight art shows, known as the Impressionist Exhibitions. Degas took a leading role in organizing the exhibitions, and showed his work in all but one of them, despite his persistent conflicts with others in the group. He had little in common with ] and the other landscape painters in the group, whom he mocked for ]. Conservative in his social attitudes, he abhorred the scandal created by the exhibitions, as well as the publicity and advertising that his colleagues sought.<ref name="Gordon31"/> He also deeply disliked being associated with the term "Impressionist", which the press had coined and popularized, and insisted on including non-Impressionist artists such as ] and ] in the group's exhibitions. The resulting rancor within the group contributed to its disbanding in 1886.<ref>Armstrong 1991, p. 25</ref> | |||

| As his financial situation improved through sales of his own work, he was able to indulge his passion for collecting works by artists he admired: old masters such as ] and such contemporaries as ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. Three artists he idolized, ], ], and ], were especially well represented in his collection.<ref>"In the final inventory of his collection, there were twenty paintings and eighty-eight drawings by Ingres, thirteen paintings and almost two hundred drawings by ]. There were hundreds of lithographs by ]. His contemporaries were well represented—with the exception of ], by whom he had nothing." Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 37</ref> | |||

| In the late 1880s, Degas also developed a passion for photography.<ref>Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 26</ref> He photographed many of his friends, often by lamplight, as in his double portrait of ] and ]. Other photographs, depicting dancers and nudes, were used for reference in some of Degas's drawings, and paintings.<ref>Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 34</ref> | |||

| As the years passed, Degas became isolated, due in part to his belief that a painter could have no personal life.<ref>Canaday 1969, p. 929</ref> The ] controversy brought his ] leanings to the fore and he broke with all his ]ish friends.<ref name="Guillaud and Guillaud, 1985, p. 56">Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 56</ref> His argumentative nature was deplored by Renoir, who said of him: "What a creature he was, that Degas! All his friends had to leave him; I was one of the last to go, but even I couldn't stay till the end."<ref name="Bade and Degas 1992, p. 6">Bade and Degas 1992, p. 6</ref> | |||

| After 1890, Degas's eyesight, which had long troubled him, deteriorated further.<ref>Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 99.</ref> Although he is known to have been working in ] as late as the end of 1907, and is believed to have continued making sculptures as late as 1910, he apparently ceased working in 1912, when the impending demolition of his longtime residence on the rue Victor Massé forced him to move to quarters on the ].<ref>Thomson 1988, p. 211</ref> He never married, and spent the last years of his life, nearly blind, restlessly wandering the streets of Paris before dying in September 1917.<ref>Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 41</ref> | |||

| ==Artistic style== | ==Artistic style== | ||

| ].]] | ]'', 1873–1876, oil on canvas]] | ||

| Degas is often identified as an ], an understandable but insufficient description. Impressionism originated in the 1860s and 1870s and grew, in part, from the realism of painters such as ] and ]. The Impressionists painted the realities of the world around them using bright, "dazzling" colors, concentrating primarily on the effects of light, and hoping to infuse their scenes with immediacy. They wanted to express their visual experience in that exact moment.<ref>Clay 1973, p. 28.</ref> | |||

| Degas is often identified as an ], an understandable, but erroneous belief. (Mannering 7). Degas was different from the impressionists in that he "never adopted the Impressionist color fleck"(Hartt 365). and "disapproved of their work" (Mannering 7). Degas is, however, described more accurately as an impressionist than as a member of any other movement. Impressionism was a short, varied movement during 1860s and 70s that grew out of ] and the ideas of two painters, ] and ]. The movement used bright, "dazzling" colors, while still concentrating primarily on the effects of light (Hartt 357-358). The movement, which also focused on "the division of tone,"("Impressionism", 953) was started by a group of painters who met each other in Paris around 1860 ("Impressionism", 953). The impressionists exhibited their paintings eight times between 1874 and 1886 and were insultingly given their name by ] at the time of their first exhibition. However, they were not universally disliked ,and, by the early 1880s, the general public had begun to accept their art. Unfortunately, the group was, by that time, breaking up both artistically and geographically, thus ending the Impressionist movement by the late 1880s("Impressionism" 953-955). | |||

| Technically, Degas differs from the Impressionists in that he continually belittled their practice of painting '']''.<ref>Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 11</ref> | |||

| Degas, as at best a partial member of the impressionist group, had his own distinct style, one developed from two very different influences, ], and ] (Dorra, 208). Degas, though famous for horses and dancers, began with conventional historical paintings such as ''The Young Spartans''. During his early career, Degas also painted portraits of both individuals and groups, for example, The Belelli Family. However, even in these early paintings, Degas began to show the style that he would later develop by cropping paintings awkwardly, implying tensions, and portraying historical subjects in a less idealized manner (Mannering 11-13). Also during this early period, Degas painted about the tensions present between men and women (Benedek "Style."). | |||

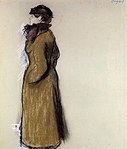

| By the late 1860s, Degas had begun to paint in his own style, one different from that of the conventional art world. During this time, he began to paint women at work, ]s, ], ] performers, and ]s. Degas began to paint ] life as well. He also asked other artists to paint about real life instead of traditional mythological or historical paintings (Benedek "Style."). As his subject matter changed, Degas also began to change his technique. He began to use "vibrant strokes"(Dorra 208) and "vivid colors"(Benedek "Style."). | |||

| <blockquote>You know what I think of people who work out in the open. If I were the government I would have a special brigade of ] to keep an eye on artists who paint landscapes from nature. Oh, I don't mean to kill anyone; just a little dose of bird-shot now and then as a warning.<ref>, Crown, New York, 1937, p. 56</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ]'', ], Edgar Degas, ], St. Petersburg]] | |||

| ] | |||

| In addition, Degas made other changes in his technique. His paintings, such as ] became like "snapshots,"(Hartt 365) freezing moments of time to show them accurately and completely (Hartt 365). His paintings also showed subjects from unusual angles. All of these techniques were used with Degas's self-expressed goal of "'bewitching the truth'"(Hartt, 365). Degas also used certain amusing devices in his paintings. For example he would paint the faces of friends on people in his paintings, such as in The Musicians of the Opera. He also painted literary scenes; for example, Interior, which was probably based on a scene from Therese Raquin (Mannering 22, 25). | |||

| "He was often as anti-impressionist as the critics who reviewed the shows", according to art historian ]; as Degas himself explained, "no art was ever less spontaneous than mine. What I do is the result of reflection and of the study of the great masters; of inspiration, spontaneity, temperament, I know nothing."<ref>Armstrong 1991, p. 22</ref> Nonetheless, he is described more accurately as an Impressionist than as a member of any other movement. His scenes of Parisian life, his off-center compositions, his experiments with color and form, and his friendship with several key Impressionist artists—most notably ] and Manet—all relate him intimately to the Impressionist movement.<ref name="Roskill, 1983, p. 33">Roskill 1983, p. 33</ref> | |||

| Degas's style reflects his deep respect for the old masters (he was an enthusiastic copyist well into middle age)<ref>Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 151</ref> and his great admiration for Ingres and Delacroix. He was also a collector of ], whose compositional principles influenced his work, as did the vigorous realism of popular illustrators such as Daumier and ]. Although famous for horses and dancers, Degas began with conventional historical paintings such as ''The Daughter of Jephthah'' ({{Circa|1859–61}}) and '']'' ({{Circa|1860–62}}), in which his gradual progress toward a less idealized treatment of the figure is already apparent. During his early career, Degas also painted portraits of individuals and groups; an example of the latter is '']'' ({{Circa|1858–67}}), an ambitious and psychologically poignant portrayal of his aunt, her husband, and their children.<ref>Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 189</ref> In this painting, as in ''Young Spartans Exercising'' and many later works, Degas was drawn to the tensions present between men and women.<ref>Shackelford, et al. 2011, pp. 60–61</ref> In his early paintings, Degas already evidenced the mature style that he would later develop more fully by cropping subjects awkwardly and by choosing unusual viewpoints.<ref>Gordon and Forge 1988, pp. 120–126, 137</ref> | |||

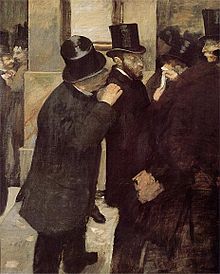

| During the later 1870s, Degas again began to change his style, in that he began to move away from his traditional medium, ] on ] (Mannering 8-49). He also ceased to paint individual people and began instead to paint generalized people based on their social stature or form of employment(Benedek "Style."). In 1879's ], he portrayed a group of Jewish businessmen. | |||

| ]}}, 1876, oil on canvas]] | |||

| ] – ], Edgar Degas, ], Paris.]] | |||

| By the late 1860s, Degas had shifted from his initial forays into history painting to an original observation of contemporary life. Racecourse scenes provided an opportunity to depict horses and their riders in a modern context. He began to paint women at work, ] and ].<ref name="Lubrich-2022" /> His milliner series is interpreted as artistic self-reflection.<ref name="Lubrich-2022">{{Cite journal |last=Lubrich |first=Naomi |title="Ceci n'est pas un chapeau: What is Art and what is Fashion in Degas's Millinery Series?" |journal=Fashion Theory |publication-date=2022}}</ref> | |||

| ''Mlle. Fiocre in the Ballet La Source'', exhibited in the Salon of 1868, was his first major work to introduce a subject with which he would become especially identified, dancers.<ref>Dumas 1988, p. 9.</ref> In many subsequent paintings, dancers were shown backstage or in rehearsal, emphasizing their status as professionals doing a job. From 1870 Degas increasingly painted ] subjects, partly because they sold well and provided him with needed income after his brother's debts had left the family bankrupt.<ref name="Growe 1992">Growe 1992</ref> Degas began to paint café life as well, in works such as {{Lang|fr|]}} and ''Singer with a Glove''. His paintings often hinted at narrative content in a way that was highly ambiguous; for example, '']'' (which has also been called ''The Rape'') has presented a conundrum to art historians in search of a literary source—'']'' has been suggested<ref>Reff 1976, pp. 200–204</ref>—but it may be a depiction of ].<ref>Krämer 2007</ref> | |||

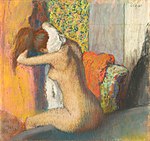

| These changes helped to give birth to the paintings that Degas would produce in later life. In the late years of his life, Degas began, controversially, to draw women drying themselves with towels, combing their hair, and bathing. At the same time, Degas began to use ]s rather than paint to create his works(Mannering 70). His strokes also became "long" and "slashing"(Mannering 75). The pictures created in this late period of his life bear almost no resemblance to his early paintings(Mannering 77). Ironically, it is these paintings, created late in Degas's life after the end of the Impressionist Movement that use the techniques of Impressionism and show Degas as an Impressionist in art not just business (Mannering 70-77). | |||

| As his subject matter changed, so, too, did Degas's technique. The dark palette that bore the influence of Dutch painting gave way to the use of vivid colors and bold brushstrokes. Paintings such as '']'' read as "snapshots," freezing moments of time to portray them accurately, imparting a sense of movement. The lack of color in the 1874 ''Ballet Rehearsal on Stage'' and the 1876 ''The Ballet Instructor'' can be said to link with his interest in the new technique of photography. The changes to his palette, brushwork, and sense of composition all evidence the influence that both the Impressionist movement and modern photography, with its spontaneous images and off-kilter angles, had on his work.<ref name="Roskill, 1983, p. 33"/> | |||

| However, certain features of Degas's work remained the same throughout his life. He always worked in his ], painting either from memory or models. (Benedek "Style."). Also, Degas often repeated a subject many times(Sellier and Peugeot 39). Finally, Degas painted and drew, with few exceptions, indoor scenes. | |||

| ]'', 1875, oil on canvas, ], St. Petersburg]] | |||

| The masterful style of Degas allowed him to produce many great works during his life time. The first of these was the Bellelli Family. It was painted in oil on canvas in 1859, and is a group portrait of Degas's Italian cousins ("Edgar Degas, 1834-1917" 4,20). Another of Degas's paintings, Absinthe, is very well known. The painting is probably making a moral point about drinking (Mannering 43), but it also exhibits a number of well-executed techniques. It is a "superb composition" and carefully uses diagonals to create depth(Hartt 365). Of course, Degas is probably most famous for painting ballet dancers in paintings such as The Rehearsal. The Rehearsal, painted with oil on canvas, effectively uses Degas's "snapshot" effect, truncating dancers here and there, blocking others with inanimate objects and positioning major elements off-center. Finally, the room's proportions, lighting, and atmosphere give the painting a "calm" feeling (Mannering 30). One of Degas's later works, After the Bath has also achieved considerable fame, and demonstrates many of the techniques used by Degas in later life. It, in typical Degas style, shows the subject from a strange angle. It also uses a pastel stroke very characteristic of the impressionists and Degas's later style. Finally the painting has texture ("Edgar Degas, 1834-1917") and a "glorious richness of colour" (Mannering 75).In his paintings, Degas would put small little details. For example, in New Orlens Cotten office, all of the people in the painting are various members of his family. | |||

| Blurring the distinction between portraiture and ] pieces, he painted his bassoonist friend, ], in '']'' (c. 1870) as one of fourteen musicians in an orchestra pit, viewed as though by a member of the audience. Above the musicians can be seen only the legs and tutus of the dancers onstage, their figures cropped by the edge of the painting. Art historian Charles Stuckey has compared the viewpoint to that of a distracted spectator at a ballet, and says that "it is Degas' fascination with the depiction of movement, including the movement of a spectator's eyes as during a random glance, that is properly speaking 'Impressionist'."<ref>Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 28</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Degas's mature style is distinguished by conspicuously unfinished passages, even in otherwise tightly rendered paintings. He frequently blamed his eye troubles for his inability to finish, an explanation that met with some skepticism from colleagues and collectors who reasoned, as Stuckey explains, that "his pictures could hardly have been executed by anyone with inadequate vision".<ref name="Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 29"/> The artist provided another clue when he described his predilection "to begin a hundred things and not finish one of them",<ref>Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 50</ref> and was in any case notoriously reluctant to consider a painting complete.<ref>Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 30</ref> | |||

| His interest in portraiture led Degas to study carefully the ways in which a person's social stature or form of employment may be revealed by their ], posture, dress, and other attributes. In his 1879 '']'', he portrayed a group of Jewish businessmen with a hint of anti-Semitism. In 1881, he exhibited two pastels, ''Criminal Physiognomies'', that depicted juvenile gang members recently convicted of murder in the "Abadie Affair". Degas had attended their trial with sketchbook in hand, and his numerous drawings of the defendants reveal his interest in the ] features thought by some 19th-century scientists to be evidence of innate criminality.<ref>{{cite book |title=Degas and The Little Dancer |first=Richard |last= Kendall |year=1998 |pages= 78–85 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-300-07497-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=O4pupXRt8NUC&pg=PA78 |display-authors=etal}}</ref> In his paintings of dancers and laundresses, he reveals their occupations not only by their dress and activities but also by their body type: his ballerinas exhibit an athletic physicality, while his laundresses are heavy and solid.<ref>Muehlig 1979, p. 6</ref> | |||

| ], Paris]] | |||

| By the later 1870s, Degas had mastered not only the traditional medium of ] on ], but pastel as well. The dry medium, which he applied in complex layers and textures, enabled him more easily to reconcile his facility for line with a growing interest in expressive color.<ref>Kendall 1996, pp. 93, 97</ref> | |||

| In the mid-1870s, he also returned to the medium of ], which he had neglected for ten years. At first he was guided in this by his old friend ], himself an innovator in its use, and began experimenting with ]y and ].<ref name="Thomson75">Thomson 1988, p. 75</ref> | |||

| He produced some 300 monotypes over two periods, from the mid-1870s to the mid-1880s and again in the early 1890s.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cosmopolis.ch/english/art/e0019100/degas_a_strange_new_beauty_e0191000.htm|title=Degas: A Strange New Beauty|first=Louis|last=Gerber}}{{Dead link|date=April 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| He was especially fascinated by the effects produced by monotype and frequently reworked the printed images with pastel.<ref name="Thomson75" /> By 1880, sculpture had become one more strand to Degas's continuing endeavor to explore different media, although the artist displayed only one sculpture publicly during his lifetime.<ref>Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 182</ref> | |||

| ], St. Petersburg]] | |||

| These changes in media engendered the paintings that Degas would produce in later life. Degas began to draw and paint women drying themselves with towels, combing their hair, and bathing (see: '']''). The strokes that model the form are scribbled more freely than before; backgrounds are simplified.<ref name="auto">Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 48</ref> | |||

| The meticulous naturalism of his youth gave way to an increasing abstraction of form. Except for his characteristically brilliant draftsmanship and obsession with the figure, the pictures created in this late period of his life bear little superficial resemblance to his early paintings. In point of fact, these paintings—created late in his life and after the heyday of the Impressionist movement—most vividly use the coloristic techniques of Impressionism.<ref>Mannering 1994, pp. 70–77</ref><ref>, H.N. Abrams, New York, 1952, p. 6</ref> | |||

| For all the stylistic evolution, certain features of Degas's work remained the same throughout his life. He always painted indoors, preferring to work in his ] from memory, photographs, or live models.<ref>Benedek "Style."</ref> The figure remained his primary subject; his few landscapes were produced from memory or imagination. It was not unusual for him to repeat a subject many times, varying the composition or treatment. He was a deliberative artist whose works, as Andrew Forge has written, "were prepared, calculated, practiced, developed in stages. They were made up of parts. The adjustment of each part to the whole, their linear arrangement, was the occasion for infinite reflection and experiment."<ref>Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 9</ref> Degas explained, "In art, nothing should look like chance, not even movement".<ref name="Growe 1992"/> He was most interested in the presentation of his paintings, patronizing ] as a framer, and disliking ornate styles of the day, often insisting on his choices for the framing as a condition of purchase.<ref>Blakenmore, Erin, "", '']'', 16 October 2022.</ref> | |||

| ==Sculpture== | |||

| {{external media | width = 210px | float = right | |||

| | headerimage = ] '']'', (1879) ], ] | |||

| | video1 =, ] | |||

| | video2 = , ] | |||

| | video3 = {{YouTube|oNPfCKhovI8|Video Postcard: ''The Millinery Shop'' (1879/86)}}, ] | |||

| }} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Degas's only showing of sculpture during his life took place in 1881 when he exhibited ''The ]''. A nearly life-size wax figure with real hair and dressed in a cloth tutu, it provoked a strong reaction from critics, most of whom found its realism extraordinary but denounced the dancer as ugly.<ref name="Cohan_Artnews"/> In a review, ] wrote: "The terrible reality of this statuette evidently produces uneasiness in the spectators; all their notions about sculpture, about those cold inanimate whitenesses ... are here overturned. The fact is that with his first attempt Monsieur Degas has revolutionized the traditions of sculpture as he has long since shaken the conventions of painting."<ref>Gordon and Forge 1988, p. 206</ref> | |||

| Degas created a substantial number of other sculptures during a span of four decades, but they remained unseen by the public until a posthumous exhibition in 1918. Neither ''The Little Dancer of Fourteen Years'' nor any of Degas's other sculptures were cast in bronze during the artist's lifetime.<ref name="Cohan_Artnews"/> Degas scholars have agreed that the sculptures were not created as aids to painting, although the artist habitually explored ways of linking graphic art and oil painting, drawing and pastel, sculpture and photography. Degas assigned the same significance to sculpture as to drawing: "Drawing is a way of thinking, modelling another".<ref name="Growe 1992"/> | |||

| After Degas's death, his heirs found in his studio 150 wax sculptures, many in disrepair. They consulted foundry owner Adrien Hébrard, who concluded that 74 of the waxes could be cast in ]. It is assumed that, except for the ''Little Dancer Aged Fourteen'', all Degas bronzes worldwide are cast from ''{{Interlanguage link|surmoulages|fr}}'' (i.e., cast from bronze masters). A ''surmoulage'' bronze is a bit smaller, and shows less surface detail, than its original bronze mold. The Hébrard Foundry cast the bronzes from 1919 until 1936, and closed down in 1937, shortly before Hébrard's death. | |||

| In 2004, a little-known group of 73 ] casts, more or less closely resembling Degas's original wax sculptures, was presented as having been discovered among the materials bought by the Airaindor Foundry (later known as Airaindor-Valsuani) from Hébrard's descendants. Bronzes cast from these plasters were issued between 2004 and 2016 by Airaindor-Valsuani in editions inconsistently marked and thus of unknown size. There has been substantial controversy concerning the authenticity of these plasters as well as the circumstances and date of their creation as proposed by their promoters.<ref name="Cohan_Artnews">Cohan, William D., , ''Artnews'', 1 April 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2014.</ref><ref>Cohan, William D. , ''The New York Times'', 4 April 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.</ref> While several museum and academic professionals accept them as presented, most of the recognized Degas scholars have declined to comment.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Degas-bronzes-controversy-leads-to-scholars-boycott/26580 |last1=Bailey |first1=Martin |title=Degas bronzes controversy leads to scholars' boycott |date= 31 May 2012 |publisher=The Art Newspaper |access-date=4 January 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120819112037/http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Degas-bronzes-controversy-leads-to-scholars-boycott/26580 |archive-date=19 August 2012 }}</ref><ref>According to William Cohan, "a group of Degas experts" who convened in January 2010 to discuss the sculptures reached "universal agreement ... that these things were not what they were being advertised as", but declined to speak on the record, citing fear of litigation. {{cite web |last1=Cohan |first1=William D. |url=http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2011-08-23/shaky-degas-sculpture-gets-silent-treatment-commentary-by-william-cohan |title=Shaky Degas Dancer Gets the Silent Treatment |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160327183247/http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2011-08-23/shaky-degas-sculpture-gets-silent-treatment-commentary-by-william-cohan |archive-date=27 March 2016 |website=Bloomberg View |date=22 August 2011 |access-date=13 August 2014}}</ref> | |||

| ==Personality and politics== | |||

| ]'', 1879]] | |||

| ]'' (photograph), c. 1895]] | |||

| Degas, who believed that "the artist must live alone, and his private life must remain unknown",<ref name="Werner11">Werner 1969, p. 11</ref> lived an outwardly uneventful life. In company he was known for his wit, which could often be cruel. He was characterized as an "old curmudgeon" by the novelist ],<ref name="Werner11" /> and he deliberately cultivated his reputation as a ] bachelor.<ref name="Bade and Degas 1992, p. 6"/> | |||

| In the 1870s, Degas gravitated towards the ] circles of ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Nord |first=Philip G. |title=The Republican Moment: Struggles for Democracy in Nineteenth-century France |url=https://archive.org/details/republicanmoment0000nord |url-access=registration |date=1995 |publisher=] |pages=|isbn=9780674762718 }}</ref> However, his republicanism did not come untainted, and signs of the prejudice and irritability which would overtake him in old age were occasionally manifested. He fired a model upon learning she was ].<ref name="Werner11" /> Although Degas painted a number of Jewish subjects from 1865 to 1870, his 1879 painting '']'' may be a watershed in his political opinions. The painting is a portrait of the Jewish banker Ernest May—who may have commissioned the work and was its first owner—and is widely regarded as anti-Semitic by modern experts. The facial features of the banker in profile have been directly compared to those in the ] cartoons rampant in Paris at the time, while those of the background characters have drawn comparisons to Degas' earlier work ''Criminal Physiognomies''.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111001011842/http://blogs.princeton.edu/wri152-3/f05/eharwood/insider_trading_degas_most_antisemitic_painting.html|date=1 October 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bernheimer |first1=Charles |last2=Armstrong |first2=Carol |last3=Kendall |first3=Richard |last4=Pollock |first4=Griselda |author-link4=Griselda Pollock |title=Odd Man Out: Readings of the Work and Reputation of Edgar Degas |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3045939 |journal=The Art Bulletin |volume=75 |issue=1 |pages=180 |date=March 1993 |jstor=3045939 |issn=0004-3079 |doi=10.2307/3045939}}</ref> | |||

| The ], which divided opinion in Paris from the 1890s to the early 1900s, intensified his anti-Semitism. By the mid-1890s, he had broken off relations with all of his Jewish friends,<ref name="Guillaud and Guillaud, 1985, p. 56" /> publicly disavowed his previous friendships with Jewish artists, and refused to use models who he believed might be Jewish. He remained an outspoken anti-Semite and member of the anti-Semitic ] until his death.<ref>{{cite book |last=Nochlin |first=Linda |author-link=Linda Nochlin |title=Politics of Vision: Essays on 19th Century Art And Society |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HCwD6Kgp_d0C&q=pissarro+and+degas+%22anti-semitism%22&pg=PA141 |publisher=] |year=1989 |isbn=978-0-06-430187-9 }}{{Dead link|date=May 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| ==Reputation== | ==Reputation== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| During his life, public reception of Degas's work ranged from admiration to contempt. As a promising artist in the conventional mode, Degas had a number of paintings accepted in the Salon between 1865 and 1870. These works received praise from ] and the critic ].<ref>Bowness 1965, pp. 41–42</ref> He soon joined forces with the Impressionists, however, and rejected the rigid rules and judgments of the Salon.<ref name="auto1"/> | |||

| The works of Degas were received in varied ways throughout his life, from admiration to contempt. His career as that of a promising artist in the conventional school of art, and in the several years following 1860, Degas had a number of paintings accepted in the Salon. These works received praise from ] and Castagnary, a critic, demonstrating his success in conventional art (Bowness 41-42). However, Degas soon joined the impressionist movement and rejected the Salon, just as the Salon and general public rejected the impressionists. His work was, at that time, considered "controversial" (Benedek "Style."), and Degas was, as an impressionist ridiculed by many including Louis Leroy(Benedek "Style."). However, towards the end of the impressionist movement, Degas began to gain acceptance ("Impressionism" , 953-955), and by his death, Degas was considered an important artist (Cannaday 935). Degas, though, made no important contributions to the style of the impressionists; instead, his contributions involved the organization of exhibitions. Today, Degas is thought of as "one of the founders impressionism"(Mannering 6-7), his work is highly regarded, and his ]s as well as his ]s (discovered after his death in his studio) are on prominent display in many museums. Unfortunately, Degas's style did not have as great an impact on future art as other that of painters because he taught no pupils whose artwork gained fame, however he did teach one man who has recently become notorious, ] (J. Paul Getty Trust). | |||

| Degas's work was controversial, but was generally admired for its draftsmanship. His '']'', or ''Little Dancer of Fourteen Years'', which he displayed at the sixth Impressionist exhibition in 1881, was probably his most controversial piece; some critics decried what they thought its "appalling ugliness" while others saw in it a "blossoming".<ref>Muehlig 1979, p. 7</ref> <blockquote>In part Degas' originality consisted in disregarding the smooth, full surfaces and contours of classical sculpture ... in garnishing his little statue with real hair and clothing made to scale like the accoutrements for a doll. These relatively "real" additions heightened the illusion, but they also posed searching questions, such as what can be referred to as "real" when art is concerned.<ref>Guillaud and Guillaud 1985, p. 46</ref></blockquote> The suite of pastels depicting nudes that Degas exhibited in the eighth Impressionist Exhibition in 1886 produced "the most concentrated body of critical writing on the artist during his lifetime ... The overall reaction was positive and laudatory".<ref>Thomson 1988, p. 135</ref> | |||

| Recognized as an important artist in his lifetime, Degas is now considered "one of the founders of Impressionism".<ref>Mannering 1994, pp. 6–7</ref> Though his work crossed many stylistic boundaries, his involvement with the other major figures of Impressionism and their exhibitions, his dynamic paintings and sketches of everyday life and activities, and his bold color experiments, served to finally tie him to the Impressionist movement as one of its greatest artists.<ref name="Roskill, 1983, p. 33"/> | |||

| Although Degas had no formal pupils, he greatly influenced several important painters, most notably ], Mary Cassatt, and ];<ref>J. Paul Getty Trust</ref> his greatest admirer may have been ].<ref name="auto"/> | |||

| Degas's paintings, pastels, drawings, and sculptures are on prominent display in many museums, and have been the subject of many museum exhibitions and retrospectives. Recent exhibitions include ''Degas: Drawings and Sketchbooks'' (The ], 2010); ''Picasso Looks at Degas'' (] de Barcelona, 2010); ''Degas and the Nude'' (], 2011); ''Degas' Method'' (], 2013); ''Degas's Little Dancer'' (], Washington D.C., 2014); ''Degas: A passion for perfection'' (], ], 2017–2018);<ref>{{cite web |title=Degas: A passion for perfection |url=http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/degas |website=Fitzwilliam Museum |access-date=23 November 2017}}</ref> and ''Manet / Degas'' at the ]<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/whats-on/exhibitions/manet-degas | title=Exhibition Manet / Degas | Musée d'Orsay }}</ref> and then the ] in 2023 and into 2024.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/manet-degas | title=The Metropolitan Museum of Art }}</ref> | |||

| == Relationship with Mary Cassatt== | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1877, Degas invited ] to exhibit in the third Impressionist exhibition.<ref>''Mary Cassatt: an American Observer: a loan exhibition for the benefit of the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Oct. 3–27, 1984''. 1984. New York, N.Y.: Coe Kerr Gallery. {{OCLC|744493160}}</ref> He had admired a portrait (''Ida'') she exhibited in the Salon of 1874, and the two formed a friendship. They had much in common: they shared similar tastes in art and literature, came from affluent backgrounds, had studied painting in Italy, and both were independent, never marrying. Both regarded themselves as figure painters, and the art historian George Shackelford suggests they were influenced by the art critic ]'s appeal in his pamphlet ''The New Painting'' for a revitalization in figure painting: "Let us take leave of the stylized human body, which is treated like a vase. What we need is the characteristic modern person in his clothes, in the midst of his social surroundings, at home or out in the street."{{sfn|Duranty|1876}}<ref>{{Google books|AcdBAQAAQBAJ |title=MoMA Highlights: 350 Works from The Museum of Modern Art, New York |page=31}}</ref> | |||

| ], Washington DC (NPG.76.33)<ref name="auto2"/>]] | |||

| After Cassatt's parents and sister Lydia joined Cassatt in Paris in 1877, Degas, Cassatt, and Lydia were often to be seen at the Louvre studying artworks together. Degas produced two prints, notable for their technical innovation, depicting Cassatt at the Louvre looking at artworks while Lydia reads a guidebook. These were destined for a prints journal planned by Degas (together with ] and others), which never came to fruition. Cassatt frequently posed for Degas, notably for his millinery series trying on hats.<ref>Gordon and Forge 1988, pp. 110–112</ref> | |||

| Degas introduced Cassatt to pastel and engraving, while for her part Cassatt was instrumental in helping Degas sell his paintings and promoting his reputation in the United States.{{sfn|Bullard|p=14}} Cassatt and Degas worked most closely together in the fall and winter of 1879–80 when Cassatt was mastering her printmaking technique. Degas owned a small ], and by day she worked at his studio using his tools and press. However, in April 1880, Degas abruptly withdrew from the prints journal they had been collaborating on, and without his support the project folded. Although they continued to visit each other until Degas' death in 1917,{{sfn|Mathews|pp= 312–13}} she never again worked with him as closely as she had over the prints journal.{{citation needed|date=October 2023}} | |||

| Around 1884, Degas made a portrait in oils of Cassatt, ''Mary Cassatt Seated, Holding Cards''. Stephanie Strasnick suggests that the cards are probably '']'', used by artists and dealers at the time to document their work.<ref name="Strasnick">{{cite web|last=Strasnick |first=Stephanie |title=Degas and Cassatt: The Untold Story of Their Artistic Friendship |url=http://www.artnews.com/2014/03/27/national-gallery-show-explores-artistic-friendship-of-degas-and-cassatt/ |publisher=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140327165838/http://www.artnews.com/2014/03/27/national-gallery-show-explores-artistic-friendship-of-degas-and-cassatt/ |archive-date=27 March 2014 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Cassatt thought it represented her as "a repugnant person" and later sold it, writing to her dealer ] in 1912 or 1913 that "I would not want it known that I posed for it."<ref>Baumann, et al. 1994, p. 270</ref> | |||

| Degas was forthright in his views, as was Cassatt.{{sfn|Mathews| p= 149}} They clashed over the ].{{efn | Pro-Dreyfus included Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Paul Signac and Mary Cassatt. Anti-Dreyfus included Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Auguste Rodin and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.<ref>{{cite news|last=Meiseler |first=Stanley |title=History's new verdict on the Dreyfus case |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2006-jul-09-op-meisler9-story.html |newspaper=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140109164907/http://articles.latimes.com/2006/jul/09/opinion/op-meisler9 |archive-date=9 January 2014 |date=9 July 2006 |url-status=live }}</ref>}}{{sfn|Mathews| p= 275}}{{sfn|Shackelford| p= 137}} Cassatt later expressed satisfaction at the irony of Lousine Havermeyer's 1915 joint exhibition of hers and Degas' work being held in aid of ], equally capable of affectionately repeating Degas' antifemale comments as being estranged by them (when viewing her '']'' for the first time, he had commented "No woman has the right to draw like that").{{sfn|Mathews|pp= 303, 308}} | |||

| == Relationship with Suzanne Valadon== | |||

| Degas was a friend and admirer of ]. He was the first person to purchase her art, and he taught her soft-ground etching. | |||

| He wrote her several letters, most asking her to come see him with her drawings. For example, in an undated letter he said in response to one of her letters to him (translated from French): | |||

| <blockquote>Every year I see this handwriting, drawn like a saw, arriving, terrible Maria. But I never see the author arrive with a box (of drawings) under her arm. And yet I am getting very old. Happy new year.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Guérin |first1=Marcel |title=Lettres de Degas |date=1945 |publisher=Editions Bernard Grasset |location=Paris |page=233}}</ref></blockquote>R. W. Meek’s historical fiction novel, ''The Dream Collector: Sabrine & ]'', imagines Edgar Degas's friendship with ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Meek |first=R. W.. |title=The Dream Collector, Book 1, Sabrine & Sigmund Freud |date=2023 |publisher=Historium Press |isbn=978-1-962465-13-7 |location=New York |pages=297-301, 306-322}}</ref> | |||

| == Legacy with Édouard Manet == | |||

| In 2023, ] in New York exhibited a two-person exhibition of Degas and ].<ref>{{Cite news |last=Esposito |first=Veronica |date=2023-10-02 |title='It's a very rich story': the complicated connection between Manet and Degas |language=en-GB |work=The Guardian |url=https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/oct/02/manet-degas-exhibit-metropolitan-museum-art-new-york |access-date=2023-11-16 |issn=0261-3077}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Carrier |first=David |date=2023-11-01 |title=Manet/Degas |url=https://brooklynrail.org/2023/11/artseen/ManetDegas-1 |access-date=2023-11-16 |website=The Brooklyn Rail |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| == Gallery == | |||

| === Paintings === | |||

| <gallery class="center" widths="150" heights="150"> | |||

| File:Degas - Self Portrait, c.1852.jpg|Degas - Self Portrait, c.1852 | |||

| File:Marguerite de Gas 713.jpg|Marguerite de Gas 1853 | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - Achille De Gas in the Uniform of a Cadet.jpg|''Achille De Gas in the Uniform of a Cadet'', 1856/57, ], Washington, D.C. | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - The Bellelli Family - Google Art Project.jpg|'']'', 1858–1867, ], Paris | |||

| File:Degas, A Woman Seated beside a Vase of Flowers (Madame Paul Valpinçon).jpg|''Woman Seated beside a Vase of Flowers'', 1865, oil on canvas, ], New York City | |||

| File:The Collector of Prints MET DT1920.jpg|''The Amateur'', 1866, The ], New York City | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - Portrait of James Tissot.jpg|''James-Jacques-Joseph Tissot (1836–1902)'', 1867, ], New York City | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - At the Races in the Countryside - Google Art Project.jpg|'']'', 1869, ] | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - The Orchestra at the Opera - Google Art Project 2.jpg|''The Orchestra of the Opera'', 1870, ], Paris | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - Portrait of Mlle. Hortense Valpinçon - Google Art Project.jpg|''Portrait of Mlle. Hortense Valpinçon'', c. 1871, ] | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - Chasse de danse.jpg|'']'', 1871, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City | |||

| File:Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas 004.jpg|''Ballet Rehearsal'', 1873, The ], ] | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - Ballet Rehearsal on Stage - Google Art Project.jpg|''Rehearsal on Stage'', 1874, Musée d'Orsay, Paris | |||

| File:Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas 037.jpg|''At the'' Café-Concert'': The Song of the Dog'', 1875–1877, Private collection | |||

| File:Danceringreen.jpg|''Swaying Dancer (Dancer in Green)'', 1877–1879, ], Madrid | |||

| File:Fin d'arabesque, Edgar Degas.jpg|''Fin d'Arabesque'', with ballerina ], 1877, Musée d'Orsay, Paris | |||

| File:Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas 069.jpg|''Dancer with a Bouquet of Flowers (Star of the Ballet)'' (also with ballerina ]), 1878 | |||

| File:Degas - Cafekonzert Sängerin mit Handschuh.jpg|''The Singer with the Glove'', 1878, The ], ] | |||

| File:Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas 009.jpg|''Stage Rehearsal'', 1878–1879, The ], New York City | |||

| File:Portrait of Henri Michel-Lévy by Edgar Degas.jpg|Portrait of ], 1878, ] | |||

| File:Edgar Degas, Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando, 1879.jpg|'']'', 1879, The ], London | |||

| File:Degas - Frau mit Stadtkostüm.jpg|''Woman in Street Clothes, Portrait of Ellen Andrée'', 1879, pastel on paper | |||

| File:Degas, Deux danseuses .jpg|Deux danseuses, 1879 at the ] | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - Waiting - Google Art Project.jpg|'']'', pastel on paper, 1880–1882 | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - Before the Race - Walters 37850.jpg|'']'', 1882–1884, oil on panel, ], Baltimore | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - The Millinery Shop - Google Art Project.jpg|'']'', 1885, The ] | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - Dancers at the Barre - Google Art Project.jpg|''Dancers at the Bar'', 1888, The ], Washington, D.C. | |||

| File:Three Dancers in Yellow Skirts Edgar Degas.JPG|''Three Dancers in Yellow Skirts'', c. 1891, ] | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - The Milliners - 25-2007 - Saint Louis Art Museum.jpg|''The Milliners'', c. 1898, ] | |||

| File:Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas 076.jpg|''],'' 1897, pastel on paper, ], ] | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - Ukrainian Dancers - c. 1899.png|''Ukrainian Dancers'', c. 1899, pastel and charcoal on paper, 73 × 59 cm, The National Gallery, London | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===Nudes=== | |||

| <gallery class="center" widths="150" heights="150"> | |||

| File:Male Nude - Edgar Degas.jpg|''Male Nude'', 1856, oil on canvas, ], New York City | |||

| File:Young Spartans Exercising National Gallery NG3860.jpg|'']'', {{Circa|1860–1862}}, ], London | |||

| File:'Woman Getting out of the Bath' by Edgar Degas, Norton Simon Museum.JPG|''Woman Getting out of the Bath'', 1877, ], ] | |||

| File:Edgar Degas - After the bath, woman drying herself - Google Art Project.jpg|''After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself'', {{Circa|1884–1886}}, reworked between 1890 and 1900, pastel on wove paper, 40.5 × 32 cm, ], ] | |||

| File:Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas 042.jpg|''Kneeling Woman'', 1884, ], Moscow | |||

| File:Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas 032.jpg|'']'', 1886, ], ] | |||

| File:Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas 031.jpg|'']'', 1886, ], Paris, France | |||

| File:Edgar Degas (1834-1917) - 'The Bath- Woman Supporting her Back', pastel on paper, c. 1887.jpg|''The Bath: Woman Sponging Her Back'', c. 1887, pastel on paper, ] | |||

| File:Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas 045.jpg|''After the Bath, Woman Drying her Nape'', pastel on paper, 1898, ], Paris | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| === Sculptures === | |||

| <gallery class="center" widths="150px" heights="150px"> | |||

| File:Degas 3x.jpg|'']''<br />Cast ] in 1922 from a mixed-media sculpture modeled<br />c. 1879–1880<br />]<br />Partly tinted, with cotton skirt and satin hair ribbon, on a wooden base<br />]<br />New York City | |||

| File:GUGG Dancer Moving Forward, Arms Raised.jpg|''Dancer Moving Forward, Arms Raised''<br />c. 1882–1895<br />Cast ] 1919–1926<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />New York City | |||

| File:SpanishDance c1884-DegasPC20080120-8849A.jpg|''The Spanish Dance''<br />c. 1885<br />Cast ] in 1921<br />]<br />46.3 × 14.3 cm<br />]<br />] | |||

| File:GUGG Seated Woman, Wiping Her Left Side.jpg|''Seated Woman, Wiping Her Left Side''<br />c. 1896–1911<br />Cast ] 1919–1926<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />New York City | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| ===Notes=== | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ===Citations=== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ===Sources=== | |||

| *Benedek, Nelly S. "Chronology of the Artist's Life." Degas. 2004. 21 May 2004 <http://www.metmuseum.org/explore/Degas/html/indexl.html>. | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| *Tinterow, Gary. ''Degas''. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and National Gallery of Canada, 1988. | |||

| * ] (1991). '']''. Chicago / London: University of Chicago Press. {{ISBN|0-226-02695-7}} | |||

| *Benedek, Nelly S. "Degas's Artistic Style." Degas. 2004. 21 March 2004 <http://www.metmuseum.org/explore/Degas/html/index1.html>. | |||

| * |

* ]; ] (1966). ''The Viking Book of Aphorisms''. New York: Viking Press | ||

| * Bade, Patrick; Degas, Edgar (1992). ''Degas''. London: Studio Editions. {{ISBN|1-85170-845-6}} | |||

| *Cannady, John. ''The Lives of Painters Volume 3''. New York: W.W. Norton and Company Inc., 1969. | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Barter |first=Judith A. |title=Mary Cassatt, modern woman |year=1998 |publisher=Art Institute of Chicago in association with H.N. Abrams |isbn=978-0-8109-4089-5 |edition=1st |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/marycassattmoder0000cass }} | |||

| *Dorra, Henri. ''Art in Perspective'' New York: Harcourt Brace Jocanovich, Inc.:208 | |||

| * Baumann, Felix Andreas; Boggs, Jean Sutherland; Degas, Edgar; and Karabelnik, Marianne (1994). ''Degas Portraits''. London: Merrell Holberton. {{ISBN|1-85894-014-1}} | |||

| *"Edgar Degas, 1834-1917." ''The Book of Art Volume III''. New York: Grolier Incorporated, 1976:4. | |||

| * {{cite web |last=Benedek |first=Nelly S. |title=Chronology of the Artist's Life |url=http://www.metmuseum.org/explore/Degas/html/indexl.html |website=Metropolitan Museum of Art |date=2004 |access-date=6 May 2006 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060502022331/http://www.metmuseum.org/explore/degas/html/indexl.html |archive-date=2 May 2006 }} | |||

| *Hartt, Frederick. "Degas" ''Art Volume 2''. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1976: 365. | |||

| * {{cite web |last=Benedek |first=Nelly S. |title=Degas's Artistic Style |url=http://www.metmuseum.org/explore/Degas/html/index1.html |date=2004 |website=Metropolitan Museum of Art |access-date=6 May 2006 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061112095611/http://www.metmuseum.org/explore/Degas/html/index1.html |archive-date=12 November 2006 }} | |||

| *"Impressionism." ''Praeger Encyclopedia of Art Volume 3''. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1967: 952. | |||

| * Bowness, Alan. ed. (1965) "Edgar Degas", in ''The Book of Art Volume 7''. New York: Grolier Incorporated :41. | |||

| *J. Paul Getty Trust "Walter Richard Sickert." 2003. 11 May 2004 <http://www.getty.edu/art/collections/bio/a3670-1.html>. | |||

| * Brettell, Richard R.; McCullagh, Suzanne Folds (1984). ''Degas in The Art Institute of Chicago''. New York: The Art Institute of Chicago and Harry N. Abrams, Inc. {{ISBN|0-86559-058-3}} | |||

| *Mannering, Douglas. ''The Life and Works of Degas''. Great Britain: Parragon Book Service Limited, 1994. | |||

| * Brown, Marilyn (1994). ''Degas and the Business of Art: a Cotton Office in New Orleans''. Pennsylvania State University Press. {{ISBN|0-271-00944-6}} | |||

| *Peugeot, Catherine, Sellier, Marie. ''A Trip to the Orsay Museum''. Paris: ADAGP, 2001: 39. | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Bullard |first=John E. |title=Mary Cassatt: Oils and Pastels |url={{Google books |uILqAAAAMAAJ |title=Mary Cassatt: Oils and Pastels |page=239 |plainurl=yes}} |publisher=] |year=1972 |isbn=0-8230-0569-0 |lccn=70-190524 |ref={{harvid|Bullard}} }} | |||

| * Canaday, John (1969). ''The Lives of the Painters Volume 3''. New York: W. W. Norton and Company Inc. | |||

| * Clay, Jean (1973). ''Impressionism''. Secaucus, NJ: Chartwell. {{ISBN|0-399-11039-9}} | |||

| * Dorra, Henri. ''Art in Perspective'' New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.:208 | |||

| * Dumas, Ann (1988). ''Degas's ''Mlle. Fiocre'' in Context''. Brooklyn: The Brooklyn Museum. {{ISBN|0-87273-116-2}} | |||

| * Dunlop, Ian (1979). ''Degas''. New York: ]. {{OCLC|5583005}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Duranty |first=Louis Edmund |title=La Nouvelle peinture: À propos du groupe d'artistes qui expose dans les galeries Durand-Ruel, 1876 |url=https://archive.org/details/lanouvellepeint00firgoog |publisher=Echoppe |location=Paris |orig-year=1876 |year=1990 |isbn=978-2-905657-37-4 |lccn=21010788 |language=fr |ref={{harvid|Duranty|1876}} }} | |||

| * "Edgar Degas, 1834–1917", in ''The Book of Art Volume III'' (1976). New York: Grolier Incorporated:4. | |||

| * Gordon, Robert; Forge, Andrew (1988). ''Degas''. New York: Harry N. Abrams. {{ISBN|0-8109-1142-6}} | |||

| * Growe, Bernd; Edgar Degas (1992). ''Edgar Degas, 1834–1917''. Cologne: Benedikt Taschen. {{ISBN|3-8228-0560-2}} | |||

| * Guillaud, Jaqueline; Guillaud, Maurice (editors) (1985). ''Degas: Form and Space''. New York: Rizzoli. {{ISBN|0-8478-5407-8}} | |||

| * Hartt, Frederick (1976). "Degas" ''Art Volume 2''. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc.: 365. | |||

| * "Impressionism." ''Praeger Encyclopedia of Art Volume 3'' (1967). New York: Praeger Publishers: 952. | |||

| * . | |||

| * Kendall, Richard (1996). ''Degas: Beyond Impressionism''. London: National Gallery Publications in association with the Art Institute of Chicago. {{ISBN|1-85709-130-2}} | |||

| * Kendall, Richard; Degas, Edgar; Druick, Douglas W.; Beale, Arthur (1998). ''Degas and The Little Dancer''. New Haven, CT: ]. {{ISBN|0-300-07497-2}} | |||

| * Krämer, Felix (May 2007). "'Mon tableau de genre': Degas's 'Le Viol' and Gavarni's 'Lorette'". ''The Burlington Magazine'' '''149''' (1250). | |||

| * Mannering, Douglas (1994). ''The Life and Works of Degas''. Great Britain: Parragon Book Service Limited. | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Mathews |first=Nancy Mowll |author-link=Nancy Mowll Mathews |title=Mary Cassatt: A Life |publisher=] |location=New York |year=1994 |isbn=978-0-394-58497-3 |ref={{harvid|Mathews}}}} | |||

| * Muehlig, Linda D. (1979). ''Degas and the Dance, 5–27 April May 1979.'' Northampton, MA: Smith College Museum of Art. | |||

| * Peugeot, Catherine, Sellier, Marie (2001). ''A Trip to the Orsay Museum''. Paris: ADAGP: 39. | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Pollock |first=Griselda |author-link=Griselda Pollock |title=Mary Cassatt: Painter of Modern Women |url={{Google books |kRGoQgAACAAJ |title=Mary Cassatt, modern woman |plainurl=yes}} |publisher=] |location=London |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-500-20317-0 |lccn=98-60039 }} | |||

| * ] (1976). . : Metropolitan Museum of Art. {{ISBN|0-87099-146-9}} | |||

| * Roskill, Mark W. (1983). "Edgar Degas" in ''Collier's Encyclopedia''. | |||

| *{{cite book |first=George T. M. |last=Shackelford |chapter=Pas de Deux: Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/marycassattmoder0000cass/page/109 |editor-first=Judith A. |editor-last=Barter |title=Mary Cassatt, modern woman / organized by Judith A. Barter; with contributions by Erica E. Hirshler ... . |publisher=] |location=New York |year=1998 |pages= |isbn=0-8109-4089-2 |lccn=98007306 |ref={{harvid|Shackelford}} }} | |||

| * Shackelford, George T. M., Xavier Rey, Lucian Freud, Martin Gayford, and Anne Roquebert (2011). ''Degas and the Nude''. Boston: MFA Publications. {{ISBN|978-0-87846-773-0}} | |||

| * Thomson, Richard (1988). ''Degas: The Nudes''. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. {{ISBN|0-500-23509-0}} | |||

| * Tinterow, Gary (1988). ''Degas''. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and National Gallery of Canada. | |||

| * Turner, Jane (2000). ''From Monet to Cézanne: Late 19th-century French Artists''. Grove Art. New York: St Martin's Press. {{ISBN|0-312-22971-2}} | |||

| * Werner, Alfred (1969). ''Degas Pastels''. New York: Watson-Guptill. {{ISBN|0-8230-1276-X}} | |||

| * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120819112037/http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Degas-bronzes-controversy-leads-to-scholars-boycott/26580 |date=19 August 2012 }} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| <br style="clear:left;" /> | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Capriati |first=Elio |title=I Segreti di Degas |publisher=Mjm Editore |location=Milan |date=2009 |isbn=978-88-95682-68-6}} | |||

| * Dumas, Ann, et al. (1997).{{MMoAobject|67210|The Private Collection of Edgar Degas}}. New York: Distributed by H.N. Abrams. | |||

| * Naomi Lubrich: ''Ceci n’est pas un chapeau: What is Art and what is Fashion in Degas's Millinery Series?'', Fashion Theory, 2022, Manuscript ID: 2113602 | |||

| * ] and Thomson, Richard (2005). ''Degas, Sickert, and Toulouse-Lautrec: London and Paris, 1870-1910''. London: Tate Publishing. | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Valery |first=Paul |title=Degas, Manet, ] |publisher=] |date=1989}} | |||

| * ''The Painter of Modern Life: Memories of Degas by ] and ], with an introduction by ]''. London: Pallas Athene, 2011. {{ISBN|978-1-84368-080-2}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons}} | |||

| {{Wikiquote}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{EB1911 poster|Degas, Hilaire Germain Edgard|Edgar Degas}} | |||

| * | |||

| *{{Art UK bio}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * At ], Washington, D.C. 18 February — 14 May 2006. | |||

| * | |||

| * | * | ||

| * | * | ||

| * ULAN Full Record Display for Edgar Degas. Getty Vocabulary Program, Getty Research Institute. Los Angeles. | |||

| * | |||

| * | * | ||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * , fully digitized text from The Metropolitan Museum of Art libraries | |||

| * at ], from 28 March to 23 July 2023. | |||

| * at The ], from 24 September 2023 – 7 January 2024. | |||

| * {{FrenchSculptureCensus}} | |||

| * The ongoing documentation of paintings and works on paper by Edgar Degas | |||

| {{Degas|state=expanded}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Impressionists}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Authority control (arts)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Degas, Edgar}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:43, 17 December 2024

French Impressionist artist (1834–1917) "Degas" redirects here. For other uses, see Degas (disambiguation).

| Edgar Degas | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait (Degas Saluant), 1863 Self-portrait (Degas Saluant), 1863 | |

| Born | Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas (1834-07-19)19 July 1834 Paris, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 27 September 1917(1917-09-27) (aged 83) Paris, France |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture, drawing |

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | Impressionism |

| Signature | |

| |

Edgar Degas (UK: /ˈdeɪɡɑː/, US: /deɪˈɡɑː, dəˈɡɑː/; born Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas, French: [ilɛːʁ ʒɛʁmɛ̃ ɛdɡaʁ də ɡa]; 19 July 1834 – 27 September 1917) was a French Impressionist artist famous for his pastel drawings and oil paintings.

Degas also produced bronze sculptures, prints, and drawings. Degas is especially identified with the subject of dance; more than half of his works depict dancers. Although Degas is regarded as one of the founders of Impressionism, he rejected the term, preferring to be called a realist, and did not paint outdoors as many Impressionists did.

Degas was a superb draftsman, and particularly masterly in depicting movement, as can be seen in his rendition of dancers and bathing female nudes. In addition to ballet dancers and bathing women, Degas painted racehorses and racing jockeys, as well as portraits. His portraits are notable for their psychological complexity and their portrayal of human isolation.

At the beginning of his career, Degas wanted to be a history painter, a calling for which he was well prepared by his rigorous academic training and close study of classical Western art. In his early thirties he changed course, and by bringing the traditional methods of a history painter to bear on contemporary subject matter, he became a classical painter of modern life.

Early life

Degas was born in Paris, France, into a moderately wealthy family. He was the oldest of five children of Célestine Musson De Gas, a Creole from New Orleans, Louisiana, and Augustin De Gas, a banker. His maternal grandfather Germain Musson was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, of French descent, and had settled in New Orleans in 1810.

Degas (he adopted this less grandiose spelling of his family name when he became an adult) began his schooling at age eleven, enrolling in the Lycée Louis-le-Grand. His mother died when he was thirteen, and the main influences on him for the remainder of his youth were his father and several unmarried uncles. Degas began to paint early in life. By the time he graduated from the Lycée with a baccalauréat in literature in 1853, at age 18, he had turned a room in his home into an artist's studio. Upon graduating, he registered as a copyist in the Louvre Museum, but his father expected him to go to law school. Degas duly enrolled at the Faculty of Law of the University of Paris in November 1853 but applied little effort to his studies.

In 1855, he met Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whom he revered and whose advice he never forgot: "Draw lines, young man, and still more lines, both from life and from memory, and you will become a good artist." In April of that year Degas was admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts. He studied drawing there with Louis Lamothe, under whose guidance he flourished, following the style of Ingres.

In July 1856, Degas traveled to Italy, where he would remain for the next three years. In 1858, while staying with his aunt's family in Naples, he made the first studies for his early masterpiece The Bellelli Family. He also drew and painted numerous copies of works by Michelangelo, Raphael, Titian, and other Renaissance artists, but—contrary to conventional practice—he usually selected from an altarpiece a detail that had caught his attention: a secondary figure, or a head which he treated as a portrait.

Artistic career

Upon his return to France in 1859, Degas moved into a Paris studio large enough to permit him to begin painting The Bellelli Family—an imposing canvas he intended for exhibition in the Salon, although it remained unfinished until 1867. He also began work on several history paintings: Alexander and Bucephalus and The Daughter of Jephthah in 1859–60; Sémiramis Building Babylon in 1860; and Young Spartans Exercising around 1860. In 1861, Degas visited his childhood friend Paul Valpinçon in Ménil-Hubert-en-Exmes, and made the earliest of his many studies of horses. He exhibited at the Salon for the first time in 1865, when the jury accepted his painting Scene of War in the Middle Ages, which attracted little attention.

Although he exhibited annually in the Salon during the next five years, he submitted no more history paintings, and his Scene from the Steeplechase: The Fallen Jockey (Salon of 1866) signaled his growing commitment to contemporary subject matter. The change in his art was influenced primarily by the example of Édouard Manet, whom Degas had met in 1864 (while both were copying the same Diego Velázquez portrait in the Louvre, according to a story that may be apocryphal).

Upon the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Degas enlisted in the National Guard, where his partaking in the defense of Paris left him little time for painting. During rifle training his eyesight was found to be defective, and for the rest of his life his eye problems were a constant worry to him.

After the war, Degas began in 1872 an extended stay in New Orleans, where his brother René and a number of other relatives lived. Staying at the home of his Creole uncle, Michel Musson, on Esplanade Avenue, Degas produced a number of works, many depicting family members. One of Degas's New Orleans works, A Cotton Office in New Orleans, garnered favorable attention back in France, and was his only work purchased by a museum (the Pau) during his lifetime.

Degas returned to Paris in 1873 and his father died the following year, whereupon Degas learned that his brother René had amassed enormous business debts. To preserve his family's reputation, Degas sold his house and an art collection he had inherited, and used the money to pay off his brother's debts. Dependent for the first time in his life on sales of his artwork for income, he produced much of his greatest work during the decade beginning in 1874. Disenchanted by now with the Salon, he instead joined a group of young artists who were organizing an independent exhibiting society. The group soon became known as the Impressionists.

Between 1874 and 1886, they mounted eight art shows, known as the Impressionist Exhibitions. Degas took a leading role in organizing the exhibitions, and showed his work in all but one of them, despite his persistent conflicts with others in the group. He had little in common with Monet and the other landscape painters in the group, whom he mocked for painting outdoors. Conservative in his social attitudes, he abhorred the scandal created by the exhibitions, as well as the publicity and advertising that his colleagues sought. He also deeply disliked being associated with the term "Impressionist", which the press had coined and popularized, and insisted on including non-Impressionist artists such as Jean-Louis Forain and Jean-François Raffaëlli in the group's exhibitions. The resulting rancor within the group contributed to its disbanding in 1886.

As his financial situation improved through sales of his own work, he was able to indulge his passion for collecting works by artists he admired: old masters such as El Greco and such contemporaries as Manet, Cassatt, Pissarro, Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Édouard Brandon. Three artists he idolized, Ingres, Delacroix, and Daumier, were especially well represented in his collection.

In the late 1880s, Degas also developed a passion for photography. He photographed many of his friends, often by lamplight, as in his double portrait of Renoir and Mallarmé. Other photographs, depicting dancers and nudes, were used for reference in some of Degas's drawings, and paintings.

As the years passed, Degas became isolated, due in part to his belief that a painter could have no personal life. The Dreyfus Affair controversy brought his anti-Semitic leanings to the fore and he broke with all his Jewish friends. His argumentative nature was deplored by Renoir, who said of him: "What a creature he was, that Degas! All his friends had to leave him; I was one of the last to go, but even I couldn't stay till the end."

After 1890, Degas's eyesight, which had long troubled him, deteriorated further. Although he is known to have been working in pastel as late as the end of 1907, and is believed to have continued making sculptures as late as 1910, he apparently ceased working in 1912, when the impending demolition of his longtime residence on the rue Victor Massé forced him to move to quarters on the Boulevard de Clichy. He never married, and spent the last years of his life, nearly blind, restlessly wandering the streets of Paris before dying in September 1917.

Artistic style

Degas is often identified as an Impressionist, an understandable but insufficient description. Impressionism originated in the 1860s and 1870s and grew, in part, from the realism of painters such as Courbet and Corot. The Impressionists painted the realities of the world around them using bright, "dazzling" colors, concentrating primarily on the effects of light, and hoping to infuse their scenes with immediacy. They wanted to express their visual experience in that exact moment.

Technically, Degas differs from the Impressionists in that he continually belittled their practice of painting en plein air.