| Revision as of 20:08, 26 November 2006 editBeit Or (talk | contribs)6,093 edits remove tendentious addition← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 07:29, 18 December 2024 edit undo172.117.245.97 (talk) →Terminology: Added referenceTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Jewish community of Iran}} | |||

| {{npov}}{{Jew}} | |||

| {{redirect|Jews of Iran|the 2005 Dutch documentary|Jews of Iran (film)}} | |||

| ] in ]]] | |||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | |||

| | group = Iranian Jews | |||

| | native_name = {{lang|ps|یهودیان ایرانی}}<br/>{{Script/Hebrew|יהודי איראן}} | |||

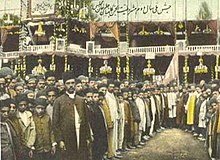

| | image = Zionist Federation in Iran.jpg | |||

| | caption = Gathering of the Zionist Federation in Iran, 1920 | |||

| | population = '''300,000'''–'''350,000''' (est.) | |||

| | region1 = {{flag|Israel}} | |||

| | pop1 = 200,000<ref name="foxnews.com" />–250,000<ref name="autogenerated2" /> | |||

| | region2 = {{flag|United States}} | |||

| | pop2 = 60,000–80,000<ref name="foxnews.com" /> | |||

| | region3 = {{flag|Iran}} | |||

| | pop3 = 9,826<ref name="worldpopulationreview.com">{{Cite web|url=https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/jewish-population-by-country|title=Jewish Population by Country 2023|website=worldpopulationreview.com}}</ref> | |||

| | region4 = {{flag|Canada}} | |||

| | pop4 = 1,000 | |||

| | region5 = {{flag|Australia}} | |||

| | pop5 = ~740{{NoteTag|] shows that 3% of them are Jewish.}} | |||

| | rels = ] ] | |||

| | langs = ] (], ], ], ]), ], ] | |||

| | related = ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Jews and Judaism sidebar|ethnicities}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2021}} | |||

| {{Use Oxford spelling|date=October 2023}} | |||

| '''Iranian Jews'''<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/jews-of-iran-a-modern-history|title=Jews of Iran: A Modern History|website=myjewishlearning.com}}</ref> ({{langx|fa|یهودیان ایرانی|translit=Yahudiyān-e Irāni}}; {{langx|he|יהודי איראן|translit=Yehudei Iran}}) constitute one of the oldest communities of the ]. Dating back to the ], they originate from the ] who relocated to ] during the time of the ]. Books of the ] (i.e., ], ], ], ], and ]) bring together an extensive narrative shedding light on contemporary Jewish life experiences in ]; there has been a continuous ] since at least the time of ], who led ] army's conquest of the ] and subsequently freed the ] from the ]. | |||

| '''Persian Jews''', '''Iranian Jews''', or the ''''''Jews of Persia'''''' are ] historically affiliated with the ] or the modern country of ]. | |||

| After 1979, Jewish emigration from Iran increased dramatically in light of the country's ]. Today, the vast majority of Iranian Jews reside in ] and the ]. The ] is mostly concentrated in the cities of ], ], ], ], and ]. In the United States, there are sizable Iranian Jewish communities in ] (]), ], and in ]. Smaller Iranian Jewish communities also exist in ] and in ]. According to the 2016 Iranian census, the remaining Jewish population of Iran stood at 9,826 people;<ref name="Iranian National Census 2016">{{cite web|url=https://www.amar.org.ir/Portals/0/census/1395/results/ch_nsonvm_95.pdf|publisher=Iranian Statistics Agency|title=Iranian Census Report 2016}}</ref> independent third-party estimates have placed the figure at around 8,500.<ref name="worldpopulationreview.com"/> | |||

| ] is one of the oldest religions practiced in Iran and dates back to the late biblical times. The biblical books of ], ], ], ], ], and ] contain references to the life and experiences of Jews in Persia. | |||

| ==Terminology== | |||

| Today, the largest groups of Persian Jews are found in ] (75,000 in 1993)<ref>{{Harvard reference|Surname=Yegar|Given=M|Authorlink=|Year=1993|Title=Jews of Iran|Journal=The Scribe|Volume=|Issue=58|Pages=2|URL=http://www.dangoor.com/TheScribe58.pdf}}. In recent years, Persian Jews have been well-assimilated into the Israeli population, so that more accurate data is hard to obtain.</ref> and the ] (45,000; especially in the ] area and ]). By various estimates, between 11,000 and 40,000 (most sources say 25,000) Jews remain in Iran, mostly in ], ] (3,000), and ]. ] reported ] is home to ten Jewish families, six of them related by marriage, however some estimate the number is much higher. Historically, Jews maintained a presence in many more Iranian cities. | |||

| Today, the term '''''Iranian Jews''''' is mostly used in reference to Jews who are from the country of ]. In various scholarly and historical texts, the term is used in reference to Jews who speak various ]. Iranian immigrants in Israel (nearly all of whom are Jewish) are referred to as ''Parsim''. In Iran, Persian Jews and Jewish people in general are both described with four common terms: ''Kalīmī'' ({{langx|fa|کلیمی}}), which is considered the most proper term; ''Yahūdī'' ({{lang|fa|یهودی}}), which is less formal but correct; ''Yīsrael'' ({{lang|he|{{Script/Hebrew|ישראל}}}}) the term by which Jewish people refer to themselves, a reference to being the ].<ref>{{cite web|url= https://jewishstudies.washington.edu/who-are-jews-jewish-history-origins-antisemitism/#:~:text=The%20Persian%20Emperor%20Cyrus%2C%20the%20only%20non%2DJew,to%20return%20to%20the%20province%20of%20Judea.&text=They%20tend%20to%20still%20refer%20to%20themselves%20as%20Bnei%20Yisrael%20(the%20descendants%20of%20Israel). |title=Who Are Jews |publisher=University of Washington |access-date=2024-12-17}}</ref> The term ''Johūd'' ({{lang|fa|جهود}}) was also used. It has very negative connotations and considered by many Jews as offensive.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://forward.com/articles/544/persian-gates/ |title=Persian Gates |publisher=Forward.com |date=2006-07-28 |access-date=2013-03-09}}</ref> | |||

| There are also smaller communities in Western Europe, Australia, and Canada. A number of groups of Persian Jews have split off since ancient times, to the extent that they are now recognized as separate communities, such as the ] and ]s. In addition, there are several thousand in Iran who are, or who are the direct descendants of, Jews who have converted to ]; some voluntarily, some by force, some due to social pressure, and some in hopes of improving prospects for themselves and their families. Such Jews, or ], have existed in the region for centuries. Many marry only those like themselves, many have assimilated, many are secular, and many are practicing Muslims who keep (sometimes unknowingly) certain Jewish traditions. Few have fully returned to their Jewish roots, and such 'hidden' Jews in the Iranian diaspora have largely assimilated. | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|History of Jews in Iran}} | ||

| The beginnings of Jewish history in Iran date back to late biblical times. The biblical books of ], ], ], ], ], and ] contain references to the life and experiences of Jews in Persia. In the book of Ezra, the Persian kings are credited with permitting and enabling the Jews to to return to ] and rebuilt their Temple; its reconstruction was affected "according to the decree of ], and ], and ] king of Persia" (Ezra 6:14). This great event in Jewish history took place in the late sixth century B.C.E., by which time there was a well-established and influential Jewish community in Persia. | |||

| Jews had been residing in ] since around 727 BC, having arrived in the region as slaves after being captured by the ]n and ]n kings. According to one Jewish legend, the first Jew to enter Persia was ], grand daughter of the ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Gorder|first=Christian |title=Christianity in Persia and the Status of Non-Muslims in Iran |year=2010|publisher=Lexington Books|page=8}}</ref> The biblical books of ], ], ], ], ], and ] contain references to the life and experiences of Jews in Persia and accounts of their relations with the ]. In the book of Ezra, the Persian kings are credited with permitting and enabling the Jews to return to ] and rebuild their Temple; its reconstruction was effected "according to the decree of ], and ], and ] king of Persia" (Ezra 6:14). This great event in Jewish history took place in the late sixth-century BC, by which time there was a well-established and influential Jewish community in Persia. | |||

| Jews who migrated to ancient Persia mostly lived in their own communities. The Persian Jewish communities include the ancient (and until the mid-] still extant) communities not only of Iran, but of parts of what is now ], ], northwestern ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| Jews in ancient Persia mostly lived in their own communities. Iranian Jews lived in the ancient (and until the mid-20th century still extant) communities not only of Iran, but also the ], ], ], ], and ] communities.<ref>Kevin Alan Brook. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006 {{ISBN|1442203021}} p. 233</ref><ref name=foa>{{cite web|url=http://www.friends-of-armenia.org/institutional/history-of-armenian-jews/44-jewish-community-of-armenia|title=Բեն Օլանդերի հատուկ ներկայացումը Նյու Յորքում նվիրված Ռաուլ Վալլենբերգին,Երեքշաբթի 9 Նոյեմբերի 2010 թ.|website=Friends-of-armenia.org|access-date=30 December 2017|archive-date=28 July 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170728082558/http://www.friends-of-armenia.org/institutional/history-of-armenian-jews/44-jewish-community-of-armenia|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>James Stuart Olson, Lee Brigance Pappas, Nicholas Charles Pappas. ''An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires''. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994 {{ISBN|0313274975}} p. 305</ref><ref>Begley, Sharon. (7 August 2012) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151229175118/http://in.reuters.com/article/us-science-genetics-jews-idINBRE8751EI20120806 |date=29 December 2015 }}. In.reuters.com. Retrieved 2013-04-16.</ref> | |||

| Some of the communities have been isolated from other Jewish communities, to the extent that their classification as "Persian Jews" is a matter of ] or ] convenience rather than actual historical relationship with one another. During the peak of the Persian Empire, Jews are thought to have comprised as much as 20% of the population. | |||

| Some of the communities have been isolated from other Jewish communities to the extent that their classification as "Persian Jews" is a matter of ] or ] convenience rather than actual historical relationship with one another. Scholars believe that during the peak of the Persian Empire, Jews may have comprised as much as 20% of the population.<ref>. Dangoor.com. Retrieved 2011-05-29.</ref> | |||

| According to ]: "''The Jews trace their heritage in Iran to the ] of the 6th century BC and, like the Armenians, have retained their ethnic, linguistic, and religious identity.''" But ]'s country study on Iran states that "''Over the centuries the Jews of Iran became physically, culturally, and linguistically indistinguishable from the non-Jewish population. The overwhelming majority of Jews speak Persian as their mother language, and a tiny minority, Kurdish.''" | |||

| According to '']'': "The Jews trace their heritage in Iran to the ] of the 6th century BC and, like the ], have retained their ethnic, linguistic, and religious identity."<ref>. Britannica.com. Retrieved 2011-05-29.</ref> But the ]'s country study on Iran states that "Over the centuries the Jews of Iran became physically, culturally, and linguistically indistinguishable from the non-Jewish population. The overwhelming majority of Jews speak Persian as their mother language, and a tiny minority, ]."<ref>. Country-data.com. Retrieved 2011-05-29.</ref> | |||

| ===Cyrus the Great and Jews=== | |||

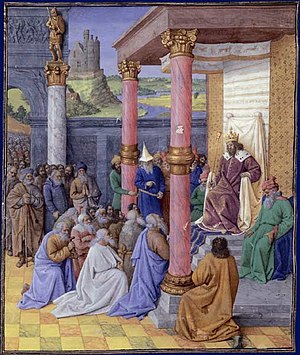

| ] allowing Hebrew pilgrims to return to and rebuild Jerusalem]] | |||

| === Achaemenid period (550–330 BC) === | |||

| Three times during the 6th century BCE, the ]s (Hebrews) of the ancient ] were exiled to ] by ]. These three separate occasions are mentioned in ] (52:28-30). The first exile was in the time of ] in ], when the ] was partially despoiled and a ]. After eleven years (in the reign of ]) a fresh rising of the Judaeans occurred; the city was razed to the ground, and a further deportation ensued. Finally, five years later, Jeremiah records a third captivity. After the overthrow of Babylonia by the ], ] gave the Jews permission to return to their native land (]), and more than forty thousand are said to have availed themselves of the privilege, (See ]; ]; ] and ]s). Cyrus also allowed them to practice their religion freely (See ]) unlike the previous Assyrian and Babylonian rulers. | |||

| === |

====Under Cyrus the Great==== | ||

| ] allowing Hebrew pilgrims to return to the ] and rebuild Jerusalem, painting by ] circa 1470]] | |||

| {{main|Second Temple}} | |||

| Cyrus had ordered rebuilding the ] in the same place as of the first, however he died before it was completed. ], after a short lived rule of ] came in to power of the Persian empire and ordered the completion of the temple. This was done under the stimulus of the earnest counsels and admonitions of the prophets ] and ]. It was ready for consecration in the spring of 515 BCE, more than twenty years after the return from captivity. | |||

| According to the biblical account ] was "God's anointed", having freed the Jews from Babylonian rule. After the conquest of ] by the Persian ], Cyrus granted all the Jews citizenship. Though he allowed the Jews to return to Israel (around 537 BC), many chose to remain in Persia. Thus, the events of the ] are set entirely in Iran. Various biblical accounts say that over forty thousand Jews did return (See ], ], ], and ]s).<ref name="Gorder 2010 17">{{cite book|last=Gorder|first=Christian|title=Christianity in Persia and the Status of Non-Muslims in Iran|year=2010|publisher=Lexington Books|page=17}}</ref> | |||

| ===Haman and Jews=== | |||

| According to the ], in the ], ] was an ] noble and ] of the ] under Persian King ], generally identified by Biblical scholars as possibly being ] in ]. Haman and his wife Zeresh instigated a plot to kill all the Jews of ancient ]. The plot was foiled by Queen ]; and as a result, Haman and his ten sons were hanged. The events of the Book of Esther are celebrated as the holiday of ]. | |||

| The historical nature of the "Cyrus decree" has been challenged. Professor Lester L Grabbe argues that there was no decree, but that there was a policy that allowed exiles to return to their homelands and rebuild their temples. He also argues that the archaeology suggests that the return was a "trickle", taking place over perhaps decades, resulting in a maximum population of perhaps 30,000.<ref>{{cite book|last=Grabbe|first=Lester L.|title=A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period: Yehud: A History of the Persian Province of Judah |year=2004|publisher=T & T Clark|isbn=978-0-567-08998-4|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-MnE5T_0RbMC&q=gave+the+Jews+permission+to+return+to+Yehud+province+and+to+rebuild+the+Temple&pg=PA355|page=355}}</ref> ] called the authenticity of the decree "dubious", citing Grabbe. Arguing against the authenticity of Ezra 1.1–4 is J. Briend, in a paper given at the Institut Catholique de Paris on 15 December 1993, who denies that it resembles the form of an official document but reflects rather the biblical prophetic idiom."<ref>{{cite book|title=Words Remembered, Texts Renewed: Essays in Honour of John F.A. Sawyer|year=1995|publisher=Continuum International Publishing Group|isbn=978-1-85075-542-5|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WQttyS7HRrIC&q=authenticity+decree+cyrus&pg=PA219|first=Philip R.|last=Davies|editor=John D Davies|page=219}}</ref> | |||

| ===Parthian period=== | |||

| Jewish sources contain no mention of the ] influence; the very name "Parthia" does not occur. The ]n prince Sanatroces, of the royal house of the Arsacides, is mentioned in the "Small Chronicle" as one of the successors (diadochoi) of ]. Among other Asiatic princes, the Roman rescript in favor of the Jews reached ] as well (I Macc. xv. 22); it is not, however, specified which Arsaces. Not long after this, the Partho-Babylonian country was trodden by the army of a Jewish prince; the ] king, ] Sidetes, marched, in company with Hyrcanus I., against the Parthians; and when the allied armies defeated the Parthians (]) at the River Zab (Lycus), the king ordered a halt of two days on account of the ] and ]. In ] the Jewish puppet-king, ] II., fell into the hands of the Parthians, who, according to their custom, cut off his ears in order to render him unfit for rulership. The Jews of Babylonia, it seems, had the intention of founding a high-priesthood for the exiled ], which they would have made quite independent of the ]. But the reverse was to come about: the Judeans received a Babylonian, Ananel by name, as their high priest which indicates the importance enjoyed by the Jews of Babylonia. Still in religious matters the ], as indeed the whole diaspora, were in many regards dependent upon the Land of Israel. They went on pilgrimages to ] for the festivals. | |||

| Mary Joan Winn Leith believes that the decree in Ezra might be authentic and, along with the ], that Cyrus, like earlier rulers, was through these decrees trying to gain support from those who might be strategically important, particularly those close to Egypt which Cyrus wished to conquer. She also wrote that "appeals to Marduk in the cylinder and to Yahweh in the biblical decree demonstrate the Persian tendency to co-opt local religious and political traditions in the interest of imperial control."<ref name="MaryJ1">{{cite book | |||

| The ] was an enduring empire that was based on a loosely configured system of vassal kings. Certainly this lack of a rigidly centralized rule over the empire had its draw backs, such as the rise of a Jewish robber-state in Nehardea (see ]). Yet, the tolerance of the ] dynasty was as legendry as the first Persian dynasty, the ]. There is even an account that indicates the conversion of a small number of Parthian ] ] of ] to ]. These instances and others show not only the tolerance of Parthian kings, but is also a testament to the extent at which the Parthians saw themselves as the heir to the preceding empire of ]. So protective were the Parthians of the minority over whom they ruled, that an old ] saying indicates, ''“When you see a Parthian charger tied up to a tomb-stone in the Land of Israel, the hour of the Messiah will be near”''. The ] ] wanted to fight in common cause with their ] brethren against ]; but it was not until the ] waged war under ] against ] that they made their hatred felt; so, that it was in a great measure owing to the revolt of the Babylonian Jews that the Romans did not become masters of Babylonia too. ] speaks of the large number of Jews resident in that country, a population which was no doubt considerably swelled by new immigrants after the destruction of Jerusalem. Accustomed in Jerusalem from early times to look to the east for help, and aware, as the Roman procurator Petronius was, that the Jews of Babylon could render effectual assistance, ] became with the fall of Jerusalem the very bulwark of Judaism. The collapse of the ] no doubt added to the number of Jewish refugees in Babylon. | |||

| | last = Winn Leith | |||

| | first = Mary Joan | |||

| | editor = Michael David Coogan | |||

| | title = The Oxford History of the Biblical World | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=zFhvECwNQD0C&q=The+Oxford+History+of+the+Biblical+World | |||

| | format = ] | |||

| | access-date =14 December 2012 | |||

| | orig-year = 1998 | |||

| | year = 2001 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | location = ]; ] | |||

| | isbn = 0-19-513937-2 | |||

| | oclc = 44650958 | |||

| | page = 285 | |||

| | chapter = Israel among the Nations: The Persian Period | |||

| | chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=zFhvECwNQD0C&q=The+Oxford+History+of+the+Biblical+World | |||

| | lccn = 98016042 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| By some accounts, the tomb of the prophet ] is located in ]. The ] was eventually (re)built in ], with assistance from the Persians, and the Israelites assumed an important position in the ] trade with ].<ref name="Gorder 2010 17"/> | |||

| In the continuous struggles between the ] and the Romans, the ] had every reason to hate the Romans, the destroyers of their sanctuary, and to side with the Parthians: their protectors. Possibly it was recognition of services thus rendered by the Jews of Babylonia, and by the Davidic house especially, that induced the Parthian kings to elevate the princes of the Exile, who till then had been little more than mere collectors of revenue, to the dignity of real princes, called '']''. Thus, then, the numerous ] subjects were provided with a central authority which assured an undisturbed development of their own internal affairs. | |||

| === |

====Under Darius the Great==== | ||

| {{Main|Second Temple}} | |||

| By the early Third Century, ] influences were on the rise again. In the winter of 226 CE, ] overthrew the last Parthian king (]), destroyed the rule of the Arsacids, and founded the illustrious dynasty of the ]. While ] influence had been felt amongst the religiously tolerant ]ns,<ref> (see esp para's 3 and 5</ref><ref> (see esp para. 2)</ref><ref> (see esp para. 20)</ref> the Sassanids intensified the Persian side of life, favored the ] language, and restored the old ] religion of ] which became the official ].<ref></ref> This resulted in the suppression of other religions.<ref> (see esp para. 5)</ref> A priestly Zoroastrian inscription from the time of King Bahram II (276–293 CE) contains a list of religions (including Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism etc.) that Sassanid rule claimed to have "smashed".<ref> (see esp para. 23)</ref> | |||

| Cyrus ordered rebuilding the ] in the same place as the first; however, he died before it was completed. ] came to power in the Persian Empire and ordered the completion of the temple. According to the Bible, the prophets ] and ] urged this work. The temple was ready for consecration in the spring of 515 BC, more than twenty years after the ]. | |||

| ====Under Ahasuerus (Bible)==== | |||

| ] (''Shvor Malka'', which is the Aramaic form of the name) was friendly to the Jews. His friendship with ] gained many advantages for the ] community. ]'s mother was Jewish, and this gave the Jewish community relative freedom of religion and many advantages. He was also friend of a ] ] in the ] named ], Raba's friendship with Shapur II enabled him to secure a relaxation of the oppressive laws enacted against the ] in the ]. In addition, Raba sometimes referred to his top student Abaye with the term Shvur Malka meaning "Shaput King" because of his bright and quick intellect. | |||

| According to the ], in the ], ] was an ] noble and ] of the ] under Persian King ], generally identified as ] (son of Darius the Great) in the 6th century BC.<ref>{{cite book|last=Johnson|first=Sara Raup|title=Historical Fictions and Hellenistic Jewish Identity: Third Maccabees in Its Cultural Context|year=2005|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-23307-2|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mfiJ6foYhMAC&q=ahasuerus+xerxes&pg=PA17|pages=16–17}}</ref> According to the story, Haman and his wife Zeresh instigated a plot to kill all the Jews of ancient ]. The plot was foiled by Queen ], the Jewish Queen of ]. As a result, Ahasuerus ordered the hanging of Haman and his ten sons. The events of the Book of Esther are celebrated as the holiday of ]. | |||

| === |

=== Parthian period (247 BC – 224 AD) === | ||

| {{unsourced section|date=January 2023}} | |||

| After the ], Jews, along with Christians and Zoroastrians, were assigned the status of ]s, inferior subjects of the Islamic empire. Dhimmis were allowed to practice their religion, but were forced to pay taxes (], a ], and initially also ], a land tax) in favor of the ] ] conquerors. Dhimmis were also required to submit to a number of social and legal disabilities; they were prohibited from bearing arms, riding horses, testifying in courts in cases involving a Muslim, and frequently required to wear clothings, clearly distinguishing them from Muslims. Although some of these restrictions were sometimes relaxed, the overall condition of inequality remained in force until the ].<ref name="littman1">Littman (1979), pp. 2–3</ref> | |||

| Jewish sources contain no mention of the ]n influence; "Parthia" does not appear in the texts.{{citation needed|date=March 2022}} The ]n prince Sanatroces, of the royal house of the Arsacides, is mentioned in the "Small Chronicle" as one of the successors ''(diadochoi)'' of ]. Among other Asiatic princes, the Roman rescript in favor of the Jews reached ] as well (I Macc. xv. 22); it is not, however, specified which Arsaces. Not long after this, the Partho-Babylonian country was trodden by the army of a Jewish prince; the ] king, ] Sidetes, marched, in company with Hyrcanus I, against the Parthians; and when the allied armies defeated the Parthians (129 BC) at the ] (Lycus), the king ordered a halt of two days on account of the ] and ]. In 40 BC the Jewish puppet-king, ], fell into the hands of the Parthians, who, according to their custom, cut off his ears in order to render him unfit for rulership. The Jews of Babylonia, it seems, had the intention of founding a high-priesthood for the exiled Hyrcanus, which they would have made quite independent of the ]. But the reverse was to come about: the Judeans received a Babylonian, Ananel by name, as their high priest, which indicates the importance enjoyed by the Jews of Babylonia. | |||

| The ] was based on a loosely configured system of vassal kings. The lack of rigidly centralized rule over the empire had drawbacks, for instance, allowing the rise of a Jewish robber-state in Nehardea (see ]). Yet, the tolerance of the ] dynasty was as legendary as that of the first Persian dynasty, the ]. One account suggests the conversion of a small number of Parthian ]s of ] to ]. These instances and others show not only the tolerance of Parthian kings, but are also a testament to the extent at which the Parthians saw themselves as the heir to the preceding empire of ]. So protective were the Parthians of the minority over whom they ruled, that an old ] saying tells, "When you see a Parthian charger tied up to a tomb-stone in the Land of Israel, the hour of the Messiah will be near". | |||

| The ]ian ] wanted to fight in common cause with their ]n brethren against ]; but it was not until the ] waged war under ] against ] that they made their hatred felt; so, the revolt of the Babylonian Jews helped prevent Rome from becoming master there. ] speaks of the numerous Jews resident in that country, a population that was likely increased by immigrants after the destruction of Jerusalem. In Jerusalem from early times, Jews had looked to the east for help. With the fall of Jerusalem, ] became a kind of bulwark of Judaism. The collapse of the ] likely also added to Jewish refugees in Babylon. | |||

| In the struggles between the ] and the Romans, the ] had reason to side with the Parthians, their protectors. Parthian kings elevated the princes of the Exile to a kind of nobility, called '']''. Until then they had used the Jews as collectors of revenue. The Parthians may have given them recognition for services, especially by the Davidic house. Establishment of the Resh Galuta provided a central authority over the numerous ] subjects, who proceeded to develop their own internal affairs. | |||

| ===Sasanian period (226–634 AD)=== | |||

| {{main|Exilarch}} | |||

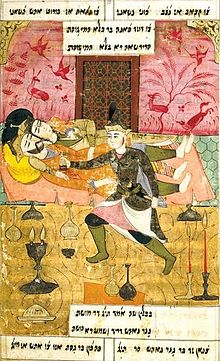

| ] version of ]'s "Khosrow va Shirin"]] | |||

| By the early third century, ] influences were on the rise again. In the winter of 226 AD, ] overthrew the last Parthian king (]), destroyed the rule of the Arsacids, and founded the dynasty of the ]. While ] influence had been felt amongst the religiously tolerant ]ns,<ref>http://depts.washington.edu/uwch/silkroad/exhibit/parthians/essay.html (see esp para's 3 and 5) {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050205080800/http://depts.washington.edu/uwch/silkroad/exhibit/parthians/essay.html |date=5 February 2005}}</ref><ref>http://www.loyno.edu/~seduffy/parthians.html (see esp para. 2) {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060515174235/http://www.loyno.edu/~seduffy/parthians.html |date=15 May 2006}}</ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110709075542/http://parents.berkeley.edu/madar-pedar/jewshistory.html |date=2011-07-09}} (see esp para. 20)</ref> the Sassanids intensified the Persian side of life, favored the ] language, and restored the old ] religion of ] which became the official ].<ref>, Parthia.com</ref> This resulted in the suppression of other religions.<ref>https://www.utexas.edu/cola/depts/lrc/eieol/armol-4.html (see esp para. 5) {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051122202212/https://www.utexas.edu/cola/depts/lrc/eieol/armol-4.html |date=22 November 2005}}</ref> A priestly Zoroastrian inscription from the time of King Bahram II (276–293 AD) contains a list of religions (including Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism etc.) that Sassanid rule claimed to have "smashed". "The false doctrines of Ahriman and of the idols suffered great blows and lost credibility. The Jews (''Yahud''), ] (''Shaman''), ] (''Brahman''), ] (''Nasara''), ] (''Kristiyan''), ] (''Makdag'') and Manichaeans ('']'') were smashed in the empire, their idols destroyed, and the habitations of the idols annihilated and turned into abodes and seats of the gods".<ref>Translation of the inscription of Bahram II, cited after {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110709075542/http://parents.berkeley.edu/madar-pedar/jewshistory.html |date=2011-07-09}}. | |||

| The interpretation of the listed terms is based on J. Wiesehöfer, ''Das antike Persien'' (1993), p. 266. | |||

| The translation of ''mandak'' (''mktky'') "baptists" is tentative, and has also been suggested to refer to the ], see | |||

| Kurt Rudolph, ''Gnosis und Spätantike Religionsgeschichte: Gesammelte Aufsätze'' (2020), . | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ] (or ''Shvor Malka'', which is the ] form of the name) was friendly to the Jews. His friendship with ] gained many advantages for the ] community. ]'s mother ] was half-Jewish, and this gave the Jewish community relative freedom of religion and many advantages. He was also friend of a ]ian ] in the ] named ], Raba's friendship with Shapur II enabled him to secure a relaxation of the oppressive laws enacted against the ] in the ]. In addition, Raba sometimes referred to his top student Abaye with the term Shvur Malka meaning "Shapur King" because of his bright and quick intellect. | |||

| ===Arab conquest and early Islamic period (634–1255)=== | |||

| With the ], the government assigned Jews, along with Christians and Zoroastrians, to the status of '']s'', non-Muslim subjects of the Islamic empire. Dhimmis were allowed to practice their religion, but were required to pay jizya to cover the cost of financial welfare, security and other benefits that Muslims were entitled to | |||

| ('']'', a ], and initially also '']'', a land tax) in place of the '']'', which the Muslim population was required to pay. Like other Dhimmis, Jews were exempt from military draft. Viewed as "People of the Book", they had some status as fellow monotheists, though they were treated differently depending on the ruler at the time. On the one hand, Jews were granted significant economic and religious freedom when compared to their co-religionists in European nations during these centuries. Many served as doctors, scholars, and craftsman, and gained positions of influence in society. On the other hand, like other non-Muslims, they were treated as somewhat inferior. | |||

| ===Mongol rule (1256–1318)=== | ===Mongol rule (1256–1318)=== | ||

| In 1255, Mongols led by ] invaded parts of Persia, and in 1258 they ] putting an end to the ] caliphate.<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061231051250/http://www.sfusd.k12.ca.us/schwww/sch618/Ibn_Battuta/Battuta's_Trip_Three.html |date=31 December 2006}}</ref> In Persia and surrounding areas, the Mongols established a division of the ] known as the ], building a capital city in ]. The Ilkhanate Mongol rulers abolished the inequality of dhimmis, and all religions were deemed equal. It was shortly after this time when one of the Ilkhanate rulers, ] Khan, preferred Jews for the administrative positions and appointed Sa'd al-Daula, a Jew, as his ]. The appointment, however, provoked resentment from the ], and after Arghun's death in 1291, al-Daula was murdered and Persian Jews in Tabriz suffered a period of violent persecutions from the Muslim populace instigated by the clergy. The ] historian ] wrote that the violence committed against the Jews during that period "neither tongue can utter, nor the pen write down".<ref name="littman2">Littman (1979), p. 3</ref> | |||

| ] version of ]'s "Khosrow va Shirin".]] | |||

| ]'s conversion to Islam in 1295 heralded for Persian Jews in Tabriz a pronounced turn for the worse, as they were once again relegated to the status of dhimmis (Covenant of Omar). ], Ghazan Khan's successor, destroyed many synagogues and decreed that Jews had to wear a distinctive mark on their heads; Christians endured similar persecutions. Under pressure, many Jews converted to Islam. The most famous such convert was ], a physician of Hamadani origin who was also a historian and statesman; and who adopted Islam in order to advance his career in Öljeitü's court in Tabriz. However, in 1318 he was executed on charges of poisoning Öljeitü and his severed head was carried around the streets of ], chanting, "This is the head of the Jew who abused the name of God; may God's curse be upon him!" About 100 years later, ] destroyed Rashid al-Din's tomb, and his remains were reburied at the Jewish cemetery. | |||

| In 1255, Mongols led by ] began a charge on Persia, and in 1257 they captured ] putting an end to the ] caliphate. In Persia and surrounding areas, the Mongols established a division of the ] known as ]. Because in Ilkhanate all religions were considered equal, Mongol rulers abolished the inequality of dhimmis. One of the Ilkhanate rulers, ] Khan, even preferred Jews and Christians for the administrative positions and appointed Sa'd al-Daula, a Jew, as his ]. The appointed, however, provoked resentment from the ], and after Arghun's death in 1291, al-Daula was murdered and Persian Jews suffered a period of violent persecutions from the Muslim populace instigated by the clergy. The contemporary Christian historian ] wrote that the violence committed against the Jews during that period "neither tongue can utter, nor the pen write down".<ref name="littman2">Littman (1979), p. 3</ref> | |||

| In 1383, ] started the military conquest of Persia. He captured ], Khorasan and all eastern Persia to 1385 and ] almost all inhabitants of ] and other Iranian cities. When revolts broke out in Persia, he ruthlessly suppressed them, massacring the populations of whole cities. When Timur plundered Persia its artists and artisans were deported to embellish Timur's capital ]. Skilled Persian Jews were imported to develop the empire's textile industry.<ref name=r1>Joanna Sloame . Jewish Virtual Library</ref>{{bsn|date=May 2022}} | |||

| ]'s conversion to Islam in 1295 heralded for Persian Jews a pronounced turn for the worse, as they were once again relegated to the status of dhimmis. ], Ghazan Khan's successor, destroyed many synagogues and decreed that Jews had to wear a distinctive mark on their heads; Christians endured similar persecutions. Under pressure, some Jews converted to Islam. The most famous such convert was ], a physician, historian and statesman, who adopted Islam in order to advance his career at Öljeitü's court. However, in 1318 he was executed on fake charges of poisoning Öljeitü and for several days crowds had been carrying his head around his native city of ], chanting "This is the head of the Jew who abused the name of God; may God's curse be upon him!" About 100 years later, ] destroyed Rashid al-Din's tomb, and his remains were reburied at the Jewish cemetery. Rashid al-Din's case illustrates a pattern that differentiated the treatment of Jewish converts in Persia from their treatment in other Muslim lands, except North Africa. In most Muslim countries, converts were welcomed and easily assimilated into the Muslim population. In Persia, however, Jewish converts were usually stigmatized on the account of their Jewish ancestry for many generations.<ref name="littman2" /><ref>Lewis (1984), pp. 100–101</ref> | |||

| ===Safavid |

=== Safavid dynasty (1501–1736) === | ||

| ] Jews in 1918]] | |||

| ==== Conversion of Iran from Sunni Islam to Shia Islam ==== | |||

| Further deterioration in the treatment of Persian Jews occurred during the reign of the Safavids who proclaimed ] the state religion. Shi'ism assigns great importance to the issues of ritual purity ― ], and non-Muslims, including Jews, are deemed to be ritually unclean ― ] ― so that physical contact with them would require Shi'as to undertake ritual purification before doing regular prayers. Thus, Persian rulers, and to an even larger extent, the populace, sought to limit physical contact between Muslims and Jews. Jews were not allowed to attend public baths with Muslims or even to go outside in rain or snow, ostensibly because some impurity could be washed from them upon a Muslim.<ref>Lewis (1984), pp. 33–34</ref> | |||

| {{Main articles|Safavid conversion of Iran to Shia Islam}} | |||

| ] (1794–1925) period.]] | |||

| ] Jews in 1918]] | |||

| The reign of Shah ] (1588–1629) was initially benign; Jews prospered throughout Persia and were even encouraged to settle in ], which was made a new capital. However, toward the end of his rule, the treatment of Jews became harsher; upon advice from a Jewish convert and Shi'a clergy, the shah forced Jews to wear a distinctive badge on clothing and headgear. In 1656, all Jews were expelled from Isfahan because of the common belief of their impurity and forced to convert to Islam. However, as it became known that the converts continued to practice ] in secret and because the treasury suffered from the loss of ''jizya'' collected from the Jews, in 1661 they were allowed to revert to Judaism, but were still required to wear a distinctive patch upon their clothings.<ref name="littman2" /> | |||

| During the reign of the ] (1502–1794), they proclaimed ] the state religion. This led to a deterioration in their treatment of Persian Jews. Safavids Shi'ism assigns importance to the issues of ritual purity – '']''. Non-Muslims, including Jews, are deemed to be ritually unclean – '']''. Any physical contact would require Shi'as to undertake ritual purification before doing regular prayers. Thus, Persian rulers, and the general populace, sought to limit physical contact between Muslims and Jews. Jews were excluded from public baths used by Muslims. They were forbidden to go outside during rain or snow, as an "impurity" could be washed from them upon a Muslim.<ref>Lewis (1984), pp. 33–34</ref> | |||

| Under ] Muslim ] (1736–1747), who abolished Shi'a Islam as state religion, Jews experienced a period of relative tolerance when they were allowed to settle in the Shi'ite holy city of ]. Yet, the advent of a Shi'a ] dynasty in 1794 brought back the earlier persecutions. In the middle of the 19th century, ] wrote about the life of Persian Jews: "…they are obliged to live in a separate part of town…; for they are considered as unclean creatures… Under the pretext of their being unclean, they are treated with the greatest severity and should they enter a street, inhabited by Mussulmans, they are pelted by the boys and mobs with stones and dirt… For the same reason, they are prohibited to go out when it rains; for it is said the rain would wash dirt off them, which would sully the feet of the Mussulmans… If a Jew is recognized as such in the streets, he is subjected to the greatest insults. The passers-by spit in his face, and sometimes beat him… unmercifully… If a Jew enters a shop for anything, he is forbidden to inspect the goods… Should his hand incautiously touch the goods, he must take them at any price the seller chooses to ask for them... Sometimes the Persians intrude into the dwellings of the Jews and take possession of whatever please them. Should the owner make the least opposition in defense of his property, he incurs the danger of atoning for it with his life... If... a Jew shows himself in the street during the three days of the Katel (Muharram)…, he is sure to be murdered."<ref>Lewis (1984), pp. 181–183</ref> | |||

| ]. Seen here is a Jewish gathering celebrating the second anniversary of the Constitutional Revolution in Tehran.]] | |||

| The reign of Shah ] (1588–1629) was initially benign; Jews prospered throughout Persia and were encouraged to settle in Isfahan, which was made a new capital. Toward the end of his rule, treatment of Jews became more harsh. Shi'a clergy (including a Jewish convert) persuaded the shah to require Jews to wear a distinctive badge on clothing and headgear. In 1656, Shah ] ordered the expulsion from Isfahan of all Jews because of the common belief of their "impurity". They were forced to convert to Islam. The treasury suffered from the loss of ''jizya'' collected from the Jews. There were rumors that the converts continued to practice ] in secret. For whatever reason, the government in 1661 allowed Jews to take up their old religion, but still required them to wear a distinctive patch upon their clothing.<ref name="littman2" /> | |||

| ] described the regional differences in the situation of the Persian Jews in 19th century: "In Isfahan, where they are said to be 3,700 and where they occupy a relatively better status than elsewhere in Persia, they are not permitted to wear ''kolah'' or Persian headdress, to have shops in the bazaar, to build the walls of their houses as high as a Moslem neighbour's, or to ride in the street. In Teheran and ] they are also to be found in large numbers and enjoying a fair position. In Shiraz they are very badly off. In Bushire they are prosperous and free from persecution."<ref>Lewis (1984), p. 167</ref> | |||

| === Afsharid dynasty (1736–1796) === | |||

| Another European traveller reported a degrading ritual to which Jews were subjected for public amusement: | |||

| ] (1736–1747) allowed Jews to settle in the Shi'ite holy city of ]. As many Jews were traders, they were able to prosper due to the connection of Mashhad to other cities along the Silk Road, most notably in Central Asia. In 1839, in an event known as ], many members of the Jewish community were forced to convert to Islam or left Mashhad, to Herat in Afghanistan or cities such as Bukhara in today's Uzbekistan. They became known as "Jadid al-Islams" (new Muslims) and appeared to superficially accept the new religion, but continued to practice many Jewish traditions, i.e. as ]. Except a few individuals, the community permanently left Mashhad in 1946, either to Tehran, but also to Bombay and Palestine. Most of them still live as a tightly knit community in Israel today.<ref name="JadidAlIslam">{{cite web | url=http://www.fis-iran.org/en/irannameh/volxix/mashhad-jewish-community | title=The "Jadid al-Islams" of Mashhad | work=Foundation for Iranian Studies | access-date=2012-11-13 | last=Pirnazar | first=Jaleh | location=Bethesda, MD | archive-date=11 September 2019 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190911223620/https://www.fis-iran.org/en/irannameh/volxix/mashhad-jewish-community | url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>At every public festival — even at the royal salaam , before the King’s face — the Jews are collected, and a number of them are flung into the hauz or tank, that King and mob may be amused by seeing them crawl out half-drowned and covered with mud. The same kindly ceremony is witnessed whenever a provincial governor holds high festival: there are fireworks and Jews.<ref>Willis (2002), p. 230</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Bābāʾī ben Nūrīʾel, a ḥāḵām (rabbi) from Isfahan translated the Pentateuch and the Psalms of David from Hebrew into Persian at the behest of Nāder Shah. Three other rabbis helped him in the translation, which was begun in Rabīʿ II 1153/May 1740, and completed in Jomādā I 1154/June 1741. At the same time, eight Muslim mullahs and three European and five Armenian priests translated the Koran and the Gospels. The commission was supervised by Mīrzā Moḥammad Mahdī Khan Monšī, the court historiographer and author of the Tārīḵ-ejahāngošā-ye nāderī. Finished translations were presented to Nāder Shah in Qazvīn in June, 1741, who, however, was not impressed. There had been previous translations of the Jewish holy books into Persian, but Bābāʾī's translation is notable for the accuracy of the Persian equivalents of Hebrew words, which has made it the subject of study by linguists. Bābāʾī's introduction to the translation of the Psalms of David is unique, and sheds a certain amount of light on the teaching methods of Iranian Jewish schools in eighteenth-century Iran. He is not known to have written anything else.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/babai-ben-nuriel|title=BĀBĀʾĪ BEN NŪRĪʾEL – Encyclopaedia Iranica|website=Iranicaonline.org|access-date=30 December 2017}}</ref> | |||

| In the 19th century there were many instances of forced conversions and massacres, usually inspired by the Shi'a clergy. A representative of the '']'', a Jewish humanitarian and educational organization, wrote from ] in 1894: "…every time that a priest wishes to emerge from obscurity and win a reputation for piety, he preaches war against the Jews".<ref>Littman (1979), p. 10</ref> In 1830, the Jews of ] were massacred; the same year saw a forcible conversion of the Jews of ]. In 1839, many Jews were massacred in Mashhad and survivors were forcibly converted. However, European travellers later reported that the Jews of Tabriz and Shiraz continued to practice Judaism in secret despite a fear of further persecutions. Jews of ] were forcibly converted in 1866; when they were allowed to revert to Judaism thanks to an intervention by the ] and ] ambassadors, a mob killed 18 Jews of Barforush, burning two of them alive.<ref>Littman (1979), p. 4.</ref><ref>Lewis (1984), p. 168.</ref> In 1910, the Jews of Shiraz ]. Muslim dwellers of the city plundered the whole Jewish quarter, the first to start looting were the soldiers sent by the local governor to defend the Jews against the enraged mob. Twelve Jews, who tried to defend their property, were killed, and many others were injured.<ref>Littman (1979), pp. 12–14</ref> Representatives of the ''Alliance Israélite Universelle'' recorded other numerous instances of persecution and debasement of Persian Jews.<ref>Lewis (1984), p. 183.</ref> | |||

| === Qajar dynasty (1789–1925) === | |||

| Driven by persecutions, thousands of Persian Jews emigrated to ] in the late 19th – early 20th century.<ref name="littman3">Littman (1979), p. 5.</ref> | |||

| The advent of the ] in 1794 brought back the earlier persecutions. | |||

| ] in Tehran.]] | |||

| ] described 19th-century regional differences in the situation of the Persian Jews: "In Isfahan, where they are said to be 3,700 and where they occupy a relatively better status than elsewhere in Persia, they are not permitted to wear ''kolah'' or Persian headdress, to have shops in the bazaar, to build the walls of their houses as high as a Moslem neighbour's, or to ride in the street. In Teheran and ] they are also to be found in large numbers and enjoying a fair position. In Shiraz they are very badly off. In Bushire they are prosperous and free from persecution."<ref>Lewis (1984), p. 167</ref> | |||

| In the 19th century, the colonial powers from Europe began noting numerous forced conversions and massacres, usually generated by Shi'a clergy. Two major blood-libel conspiracies had taken place during this period, one in Shiraz and the other in Tabriz. A document recorded after the incident states that the Jews faced two options, conversion to Islam or death. Amidst the chaos, Jews had converted, but most refused to convert to Islam – described within the document was a boy of age 16 named Yahyia who refused to convert to Islam and was subsequently killed. The same year saw a forcible conversion of the Jews of ] over a similar incident. The ] of 1839 was mentioned above. European travellers reported that the Jews of ] and ] continued to practice Judaism in secret despite a fear of further persecutions. Famous Iranian-Jewish teachers such as Mullah Daoud Chadi continued to teach and preach Judaism, inspiring Jews throughout the nation. Jews of ], Mazandaran were forcibly converted in 1866. When the French and British ambassadors intervened to allow them to practice their traditional religion, a mob killed 18 Jews.<ref>Littman (1979), p. 4.</ref><ref>Lewis (1984), p. 168.</ref> | |||

| In the middle of the 19th century, ] wrote about the life of Persian Jews, describing conditions and beliefs that went back to the 16th century: | |||

| {{blockquote|They are obliged to live in a separate part of town…; for they are considered as unclean creatures… Under the pretext of their being unclean, they are treated with the greatest severity and should they enter a street, inhabited by Mussulmans, they are pelted by the boys and mobs with stones and dirt… For the same reason, they are prohibited to go out when it rains; for it is said the rain would wash dirt off them, which would sully the feet of the Mussulmans… If a Jew is recognized as such in the streets, he is subjected to the greatest insults. The passers-by spit in his face, and sometimes beat him… unmercifully… If a Jew enters a shop for anything, he is forbidden to inspect the goods… Should his hand incautiously touch the goods, he must take them at any price the seller chooses to ask for them... Sometimes the Persians intrude into the dwellings of the Jews and take possession of whatever please them. Should the owner make the least opposition in defense of his property, he incurs the danger of atoning for it with his life... If... a Jew shows himself in the street during the three days of the ''Katel'' (Muharram)…, he is sure to be murdered.<ref>Lewis (1984), pp. 181–83</ref>}} | |||

| A group of Persian Jewish refugees escaping persecution back home in ], Qajar Persia, were granted rights to settle in the ] around the year 1839. Most of the Jewish families settled in ] (specifically in the Babu Mohallah neighbourhood) and ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Tahir |first=Saif |date=3 March 2016 |title=The lost Jewish history of Rawalpindi, Pakistan |url=http://blogs.timesofisrael.com/the-lost-jewish-history-of-rawalpindi-pakistan/ |access-date=2023-02-27 |website=blogs.timesofisrael.com |language=en-US |quote=The history of Jews in Rawalpindi dates back to 1839 when many Jewish families from Mashhad fled to save themselves from the persecutions and settled in various parts of subcontinent including Peshawar and Rawalpindi.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Considine |first=Craig |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/993691884 |title=Islam, race, and pluralism in the Pakistani diaspora |date=2017 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-315-46276-9 |location=Milton |oclc=993691884}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Khan |first=Naveed Aman |date=2018-05-12 |title=Pakistani Jews and PTI |url=https://dailytimes.com.pk/239196/pakistani-jews-and-pti/ |access-date=2023-02-27 |website=Daily Times |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Rawalpindi – Rawalpindi Development Authority |url=https://rda.gop.pk/rawalpindi/ |access-date=2023-02-27 |website=Rawalpindi Development Authority (rda.gop.pk) |quote=Jews first arrived in Rawalpindi’s Babu Mohallah neighbourhood from Mashhad, Persia in 1839, in order to flee from anti-Jewish laws instituted by the Qajar dynasty.}}</ref> | |||

| In 1868, Jews were the most significant minority in Tehran, numbering 1,578 people.<ref name="Sohrabi">{{cite journal |last1=Sohrabi |first1=Narciss M. |title=The politics of in/visibility: The Jews of urban Tehran |journal=Studies in Religion |date=2023 |volume=53 |page=4 |doi=10.1177/00084298231152642|s2cid=257370493 }}</ref> By 1884 this figure had risen to 5,571.<ref name="Sohrabi"/> | |||

| In 1892, an ] archival record indicates that a group of 200 Iranian Jews who tried to migrate to the Land of Israel were returned to Iran.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fishman |first=Louis A. |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctv2f4v64p |title=Jews and Palestinians in the Late Ottoman Era, 1908-1914: Claiming the Homeland |date=2020 |publisher=Edinburgh University Press |isbn=978-1-4744-5399-8 |volume=1 |pages=47 |jstor=10.3366/j.ctv2f4v64p }}</ref> | |||

| In 1894, a representative of the '']'', a Jewish humanitarian and educational organization, wrote from ]: "...every time that a priest wishes to emerge from obscurity and win a reputation for piety, he preaches war against the Jews".<ref>Littman (1979), p. 10</ref> | |||

| In 1901, the riot of Shaykh Ibrahim was sparked against the Jews of Tehran. An imam began preaching on the importance of eliminating alcohol for the sake of Islamic purity, leading to an assault against Jews for refusing to give up the wine they drank for Sabbath.<ref>Levy, Habib. "Part 1/ Part 11." Comprehensive History of The Jews of Iran The Outset of the Diaspora, edited by Hooshang Ebrami, translated by George W. Maschke, Mazda Publishers, 1999.</ref> | |||

| In 1910, there were rumors that the Jews of Shiraz ]. Muslims plundered the whole Jewish quarter. The first to start looting were soldiers sent by the local governor to defend the Jews against the enraged mob. Twelve Jews who tried to defend their property were killed, and many others were injured.<ref>Littman (1979), pp. 12–14</ref> Representatives of the ''Alliance Israélite Universelle'' recorded numerous instances of persecution and debasement of Iranian Jews.<ref>Lewis (1984), p. 183.</ref> In the late 19th to early 20th century, thousands of Iranian Jews immigrated to the territory of present-day ] within the Ottoman Empire to escape such persecution.<ref name="littman3">Littman (1979), p. 5.</ref> | |||

| ===Pahlavi dynasty (1925–1979)=== | ===Pahlavi dynasty (1925–1979)=== | ||

| ] | |||

| The ] implemented modernizing reforms, which greatly improved the life of Jews. The influence of the Shi'a clergy was weakened, and the restrictions on Jews and other religious minorities were abolished.<ref name="sanasarian2">Sanasarian (2000), p. 46</ref> Reza Shah prohibited mass conversion of Jews and eliminated the Shi'ite concept of uncleanness of non-Muslims. Modern Hebrew was incorporated into the curriculum of Jewish schools and Jewish newspapers were published. Jews were also allowed to hold government jobs. However, Jewish schools were closed in 1920s. In addition, ] sympathized with ], making the Jewish community fearful of possible persecutions, and the public sentiment at the time was definitely anti-Jewish,<ref name="sanasarian2"/>. | |||

| The ] implemented modernizing reforms, which greatly improved the life of Jews. The influence of the Shi'a clergy was weakened, and the restrictions on Jews and other religious minorities were abolished.<ref name="sanasarian2">Sanasarian (2000), p. 46</ref> According to Charles Recknagel and Azam Gorgin of ], during the reign of Reza Shah "the political and social conditions of the Jews changed fundamentally." ] prohibited mass conversion of Jews and eliminated the concept of uncleanness of non-Muslims. He allowed incorporation of modern Hebrew into the curriculum of Jewish schools and publication of Jewish newspapers. Jews were also allowed to hold government jobs.<ref>, ParsTimes. 3 July 2000</ref> | |||

| By 1932, Tehran's Jewish population had risen to 6,568.<ref name="Sohrabi"/> During ], ] declared itself neutral, but was ]. During the Allied occupation, many Polish and Jewish refugees that escaped ] settled within Iran (see ]).<ref>{{Cite web |title=Polish Refugees in Iran during World War II |url=https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/polish-refugees-in-iran-during-world-war-ii |access-date=2023-08-20 |website=encyclopedia.ushmm.org |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Dekel |first=Mikhal |date=2019-10-19 |title=When Iran Welcomed Jewish Refugees |url=https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/10/19/when-iran-welcomed-jewish-refugees/ |access-date=2023-08-20 |website=Foreign Policy |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Iran During World War II and the Holocaust |url=https://www.ushmm.org/antisemitism/holocaust-denial-and-distortion/holocaust-denial-antisemitism-iran/iran-during-world-war-ii-and-the-holocaust |access-date=2023-08-20 |website=www.ushmm.org |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| According to Charles Recknagel and Azam Gorgin of ], during the reign of Reza Shah "the political and social conditions of the Jews changed fundamentally. Reza Shah prohibited mass conversion of Jews and eliminated the Shiite concept of uncleanness of non-Muslims. Modern Hebrew was incorporated into the curriculum of Jewish schools and Jewish newspapers were published. Jews were also allowed to hold government jobs. | |||

| At the time of the establishment of the state of ] in 1948, there were approximately 140,000–150,000 Jews living in ], the historical center of Iranian Jewry. Over 95% have since migrated abroad.<ref name="mio-org-il"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170515222115/http://www.mio.org.il/en/node/289 |date=2017-05-15}}, The Council of Immigrant Associations in Israel (Pop-up info when clicking on Iran)</ref> | |||

| A spike in anti-Jewish sentiment occurred after the establishment of the ] in 1948 and continued until 1953 due to the weakening of the central government and strengthening of the clergy in the course of political struggles between the shah and prime minister ]. Eliz Sanasarian estimates that in 1948–1953, about one-third of Iranian Jews, most of them poor, emigrated to Israel.<ref name="sanasarian1">Sanasarian (2000), p. 47</ref> David Littman puts the total figure of emigrants to Israel in 1948-1978 at 70,000.<ref name="littman3" /> | |||

| The violence and disruption in Arab life associated with the founding of Israel and its victory in the ] drove increased anti-Jewish sentiment in Iran. This continued until 1953, in part because of the weakening of the central government and strengthening of clergy in the political struggles between the shah and prime minister ]. From 1948 to 1953, about one-third of Iranian Jews, most of them poor, immigrated to Israel.<ref name="sanasarian1">Sanasarian (2000), p. 47</ref> ] puts the total figure of Iranian Jews who immigrated to Israel between 1948 and 1978 at 70,000.<ref name="littman3" /> | |||

| The reign of shah ] after the deposition of Mossadegh in 1953, was the most prosperous era for the Jews of Iran. In 1970s, only 10 percent of Iranian Jews were classified as impoverished; 80 percent were middle class and 10 percent wealthy. Although Jews accounted for only a small percentage of Iran's population, in 1979 two of the 18 members of the Iranian Academy of Sciences, 80 of the 4,000 university lecturers, and 600 of the 10,000 physicians in Iran were Jews.<ref name="sanasarian1" /> | |||

| After the deposition of Mossadegh in 1953, the reign of shah ] was the most prosperous era for the Jews of Iran. By the 1970s, only 1% of Iranian Jews were classified as lower class; 80% were middle class and 10% wealthy. Although Jews accounted for only a fraction of a percent of Iran's population, in 1979 two of the 18 members of the Iranian Academy of Sciences, 80 of the 4,000 university lecturers, and 600 of the 10,000 physicians in Iran were Jews.<ref name="sanasarian1" /> | |||

| Prior to the Islamic Revolution in 1979, there were 80,000 Jews in Iran, concentrated in Teheran (60,000), Shiraz (8,000), Kermanshah (4,000), Isfahan (3,000), the cities of ], as well as Kashan, Tabriz, and Hamedan. | |||

| Prior to the ] in 1979, there were 100,000 Jews in Iran, mostly concentrated in ] (60,000), ] (18,000), ] (4,000), and ] (3,000). Jews were also located in other various cities throughout Iran, including ] (800), ] (400), ] (60), ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://thegraduatesocietyla.org/images/author-padia-others.pdf|title=An Annotated Bibliography : Amnon Netzer|website=Thegraduatesocietyla.org|access-date=30 December 2017|archive-date=12 August 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170812101544/http://thegraduatesocietyla.org/images/author-padia-others.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| ===Islamic republic (after 1979)=== | |||

| ===Islamic Republic (1979–present)=== | |||

| At the time of the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, there were approximately 140,000–150,000 Jews living in ], the historical center of Persian Jewry. Over 85% have since migrated to either Israel or the ]. At the time of the 1979 ], 80,000 still remained in Iran. From then on, Jewish emigration from Iran dramatically increased, as about 20,000 Jews left within several months after the Islamic Revolution.<ref name="littman3" /> On ], ], Habib Elghanian, the honorary leader of the Jewish community, was arrested on charges of "corruption", "contacts with Israel and ]", "friendship with the enemies of God", "warring with God and his emissaries", and "economic imperialism". He was tried by an Islamic revolutionary tribunal, sentenced to death, and executed on May 8.<ref name="littman3" /><ref>Sanasarian (2000), p. 112</ref> In mid- and late 1980s, the Jewish population of Iran was estimated at 20,000–30,000. The reports put the figure at around 35,000 in mid-1990s<ref>Sanasarian (2000), p. 48</ref> and at less than 40,000 nowadays, with around 25,000 residing in Tehran. However, Iran's Jewish community still remains the largest in the Middle East outside of Israel. | |||

| At the time of the 1979 ], 80,000–100,000 Jews were living in Iran. From then on, Jewish emigration from Iran dramatically increased, as about 20,000 Jews left within several months of the revolution alone.<ref name="littman3" /> The majority of Iran's Jewish population, some 60,000 Jews, emigrated in the aftermath of the revolution, of whom 35,000 went to the United States, 20,000 to Israel, and 5,000 to Europe (mainly to the United Kingdom, France, Denmark, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland).<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Iran.html|title=Iran Virtual Jewish History Tour|website=Jewishvirtuallibrary.org|access-date=30 December 2017}}</ref>{{bsn|date=May 2022}} | |||

| Some sources put the Iranian Jewish population in the mid and late 1980s as between 50,000 and 60,000.<ref>Sanasarian (2000), p. 48</ref> An estimate based on the 1986 census put the figure considerably higher for the same time, around 55,000.<ref>. Mongabay.com. Retrieved 2011-05-09.</ref> From the mid-1990s to the present there has been more uniformity in the figures, with most government sources since then estimating roughly 25,000 Jews remaining in Iran.<ref name="news.bbc.co.uk" /><ref name="haaretz.com" /><ref name="Ynet" /><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://csmonitor.com/cgi-bin/durableRedirect.pl?/durable/1998/02/03/intl/intl.3.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050830235806/http://csmonitor.com/cgi-bin/durableRedirect.pl?%2Fdurable%2F1998%2F02%2F03%2Fintl%2Fintl.3.html|url-status=dead|title=Jews in Iran Describe a Life of Freedom Despite Anti-Israel Actions by Tehran|csmonitor.com|website=]|archive-date=30 August 2005}}</ref> These less recent official figures are considered bloated, and the Jewish community may not amount to more than 10,000.<ref name="Hakakian" /> A ] put the figure at about 8,756.<ref name=census/> | |||

| In 2006, a false story in the '']'' of Canada claimed that the Iranian parliament was considering ] for Jews in Iran. The story was confirmed by the associate dean of the ]. ] sent out an "e-mail blast" to reporters on the story, which became a major press event in the United States.<ref></ref> The false story turned out to originate with Iranian journalist ] from the ] speakers bureau. | |||

| ] ] met with the Jewish community upon his return from exile in Paris, when heads of the community, disturbed by the execution of one of their most distinguished representatives, the industrialist ], arranged to meet him in Qom. At one point he said: | |||

| ==Current status in Iran== | |||

| Iran's Jewish community is officially recognized as a religious minority group by the government, and as with ], they are allocated one seat in the ]. ] has been the Jewish MP since ], and was re-elected again in ]. In 2000, former Jewish MP ] estimate there were still 30–35,000 Jews in Iran, other sources put the figure as low as 20–25,000.<ref>, ], ] 2000, cited from ] Library Online. The '']'' estimated the number of Jews in Iran at 25,000 in 1996.</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>In the holy Quran, Moses, salutations upon him and all his kin, has been mentioned more than any other prophet. Prophet Moses was a mere shepherd when he stood up to the might of pharaoh and destroyed him. Moses, the Speaker-to-Allah, represented pharaoh's slaves, the downtrodden, the mostazafeen of his time.</blockquote> | |||

| Iranian Jews have their own newspaper (called "Ofogh-e-Bina") with Jewish scholars performing Judaic research at ]'s "Central Library of Jewish Association".<ref name = "PersianRabbi"></ref> The "Dr. Sapir Jewish Hospital" is ]'s largest charity hospital of any religious minority community in the country;<ref name = "PersianRabbi" /> however, most of its patients and staff are Muslim.<ref name="Harrison">Harrison, Francis (], ]). ''''. ]. URL accessed on ], ].</ref> | |||

| At the end of the discussion Khomeini declared, "We recognize our Jews as separate from those godless, bloodsucking Zionists"<ref name="Hakakian">Roya Hakakian, '']'', 30 December 2014.</ref> and issued a '']'' decreeing that the Jews were to be protected.<ref>], , Yale University Press, 2007. p. 8.</ref> | |||

| Habib Elghanian was arrested and sentenced to death by an Islamic revolutionary tribunal shortly after the Islamic revolution for charges including corruption, contacts with Israel and Zionism, and "friendship with the enemies of God", and was executed by a firing squad. He was the first Jew and businessman to be executed by the Islamic government. His execution caused fear among the Jewish community and caused many to flee Iran.<ref name=shahrzade>{{cite news|last=Elghanayan|first=Shahrzad|title=How Iran killed its future|url=https://www.latimes.com/opinion/la-xpm-2012-jun-27-la-oe-elghanayan-iran-entrepreneuers-not-nukes-20120627-story.html|access-date=13 February 2013|newspaper=Los Angeles Times|date=27 June 2012}}</ref> | |||

| ===Discrimination=== | |||

| Like other religious minorities in Iran, Jews suffer from officially sanctioned discrimination, particularly in the areas of employment, education, and housing. They may not occupy senior positions in the government or the military and are prevented from serving in the judiciary and security services and from becoming public school heads.<ref name="dosreport2004">{{cite web|author=] |title=International Religious Freedom Report 2004: Iran|url= http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2004/35497.htm|accessdate=2006-05-14}}</ref> | |||

| Soli Shahvar, professor of Iranian Studies at the ] describes the process of dispossession : "There were two waves of confiscation of homes, farmlands and factories of Jews in Iran. In the first wave, the authorities seized the properties of a small group of Jews who were accused of helping Zionism financially. In the second wave, authorities confiscated the properties of Jews who had to leave the country after the Revolution. They left everything in fear for their lives and the Islamic Republic confiscated their properties using their absence as an excuse".<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://iranwire.com/en/features/7960|title=They Killed My Husband and Took My Home: Religious Minorities in Iran|website=IranWire | خانه}}</ref> | |||

| The anti‑Israel policies of the Iranian government, along with a perception among radical Muslims that all Jewish citizens support Zionism and the State of Israel, create a hostile atmosphere for the Jewish community. In 2004, many Iranian newspapers celebrated the one-hundredth anniversary of the publishing of the anti-Semitic forgery ].<ref name="dosreport2004"/> Jews often are the target of degrading caricatures in the Iranian press.<ref name="Murphy">{{cite news | author=Murphy, Brian | title=Iran's Jews caught again in no man's land | publisher=] | url=http://seattlepi.nwsource.com/national/1107AP_Irans_Jews.html|date=] | accessdate=2006-07-31}}</ref> Jewish leaders reportedly are reluctant to draw attention to official mistreatment of their community due to fear of government reprisal.<ref name="dosreport2004"/> | |||

| During the ], which lasted from 1980 to 1988, Iranian Jews were conscripted into the ], and 13 were killed in the war.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.timesofisrael.com/revolutionary-guards-honor-jewish-soldiers-at-religious-memorial-in-iran/|title=Revolutionary Guards honor Jewish soldiers at religious memorial in Iran|website=Times of Israel}}</ref> | |||

| However in a rather unprecedented move, the sole Jewish member in the Iranian parliament, ], strongly condemned exhibition of cartoons about the Holocaust which recently took palace in Tehran and he has also written a letter to Iran’s president questioning his denial of Holocaust calling it "a very big insult to Jews all around the world". | |||

| In the Islamic republic, Jews have become more religious. Families who had been secular in the 1970s started adhering to '']'' dietary laws and more strictly observed rules against driving on the '']''. They stopped going to restaurants, cafes and cinemas and the ] became the focal point of their social lives.<ref name=sephardicstudies>. Sephardicstudies.org. Retrieved 2011-05-29.</ref> | |||

| The legal system also discriminates against religious minorities who receive lower awards than Muslims in injury and death lawsuits and incur heavier punishments. In 2002, the law was passed that made the amount of "blood money" (''diyeh'') paid by a perpetrator for killing or wounding a Christian, Jew, or Zoroastrian man the same as it would be for killing or wounding a Muslim.<ref name="dosreport2004"/> | |||

| Haroun Yashyaei, a film producer and former chairman of the Central Jewish Community in Iran said, "] didn't mix up our community with ] and ] – he saw us as Iranians."<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.csmonitor.com/durable/1998/02/03/intl/intl.3.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061205024553/http://www.csmonitor.com/durable/1998/02/03/intl/intl.3.html|url-status=dead|title="Jews in Iran Describe a Life of Freedom Despite Anti-Israel Actions by Tehran"|website=]|archive-date=5 December 2006}}</ref> | |||

| ] visits a Tehran Jewish center.]] | |||

| In June 2007, though there were reports that wealthy expatriate Jews established a fund to offer incentives to Iranian Jews to immigrate to Israel, few took them up on the offer. The Society of Iranian Jews dismissed this act as "immature political enticements" and said that their national identity was not for sale.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.theguardian.com/iran/story/0,,2125155,00.html|work=The Guardian|location=London|title=Iran's Jews reject cash offer to move to Israel|first=Robert|last=Tait |date=12 July 2007|access-date=22 May 2010}}</ref> | |||

| With some exceptions, there is little restriction of or interference with the Jewish religious practice; however, education of Jewish children has become more difficult in recent years. The Iranian government reportedly allows Hebrew instruction, recognizing that it is necessary for Jewish religious practice. However, it strongly discourages the distribution of Hebrew texts, in practice making it difficult to teach the language. Moreover, the Iranian government has required that several Jewish schools remain open on Saturdays, the Jewish Sabbath, in conformity with the schedule of other schools in the school system. Since working or attending school on the Sabbath violates Jewish law, this requirement has made it impossible for observant Jews both to attend school and adhere to a fundamental tenet of their religion.<ref name="dosreport2004"/> | |||

| Jews in the Islamic Republic of Iran are formally to be treated equally and free to practice their religion. There is even a seat in the Iranian parliament reserved for the representative of the Iranian Jews. However, de facto discrimination is common.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.sephardicstudies.org/iran.html |title=Life of Jews Living in Iran |publisher=The Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture (FASSAC) |access-date=24 December 2014 |last=Demick |first=Barbara}}</ref> | |||

| Jewish citizens are permitted to obtain passports and to travel outside the country, but they often are denied the multiple-exit permits normally issued to other citizens. With the exception of certain business travelers, the authorities require Jewish persons to obtain clearance and pay additional fees before each trip abroad. The Iranian government is concerned about the emigration of Jewish citizens and permission generally is not granted for all members of a Jewish family to travel outside the country at the same time.<ref name="dosreport2004"/> | |||

| ==Current status== | |||

| In 2000, 10 of 13 Jews arrested in 1999 were convicted on charges of illegal contact with Israel, conspiracy to form an illegal organization, and recruiting agents. Along with 2 Muslim defendants, the 10 Jews received prison sentences ranging from 4 to 13 years. An appeals court subsequently overturned the convictions for forming an illegal organization and recruiting agents, but it upheld the convictions for illegal contacts with Israel with reduced sentences. One of the 10 was released in February 2001 and another in January 2002, both upon completion of their prison terms. Three additional prisoners were released before the end of their sentences in October 2002. In April 2003, it was announced that the last five were to be released. It is not clear if the eight who were released before the completion of their sentences were fully pardoned or were released provisionally.<ref name="dosreport2004"/> Even though anti-Semitic acts are rare in Iran, the trial led to the rising of tensions against the Jewish community.<ref name="Murphy"/> During and shortly after the trial, Jewish businesses in Tehran and Shiraz were targets of vandalism and boycotts, and Jewish persons reportedly have suffered personal harassment and intimidation.<ref name="dosreport2004"/> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Iran's Jewish community is officially recognized as a religious minority group by the government, and, like the ] and ], they are allocated one seat in the ]. ] is the current Jewish member of the parliament, replacing ] in the 2008 election. In 2000, former Jewish MP ] estimated that at that time there were still 60,000–85,000 Jews in Iran; most other sources put the figure at 25,000.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071012164605/http://uga.edu/bahai/News/021600.html |date=2007-10-12}}, ], 16 February 2000, cited from ] Library Online</ref> In 2011 the Jewish population numbered 8,756.<ref>2011 General Census Selected Results (PDF), Statistical Center of Iran, 2012, p. 26, ISBN 978-964-365-827-4</ref> In 2016 Jewish population numbered 9,826.<ref name="Iranian National Census 2016" /> In 2019 the Jewish Population numbered 8,300<ref name="worldpopulationreview.com"/> and they constitute 0.01% of Iranian population, a number confirmed by ], a leading Jewish demographer.<ref>{{cite book |doi=10.1007/978-3-319-70663-4_7 |chapter=World Jewish Population, 2017 |title=American Jewish Year Book 2017 |volume=117 |pages=297–377 |year=2018 |last1=Dellapergola |first1=Sergio |isbn=978-3-319-70662-7}}</ref> | |||

| Iranian Jews have their own newspaper (called "Ofogh-e-Bina") with Jewish scholars performing Judaic research at ]'s "Central Library of Jewish Association".<ref name="PersianRabbi"> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060519144638/http://www.persianrabbi.com/content/view/74/2/ |date=2006-05-19}}. Persian Rabbi. Retrieved 2011-05-29.</ref> The ] is ]'s largest charity hospital of any religious minority community in the country;<ref name = "PersianRabbi"/> however, most of its patients and staff are Muslim.<ref name="Harrison">Harrison, Francis (22 September 2006). ''''. ]. Retrieved 28 October 2006.</ref> | |||

| ===Contacts with Jews outside Iran=== | |||

| Jews in Iran are not allowed to communicate with Jewish groups outside of Iran unless the group is opposed to the existence of ], such as ].{{fact}} Rabbis from Neturei Karta frequently visit Iran. | |||

| ] ] was the spiritual leader for the Jewish community of Iran from 1994 to 2007, when he was succeeded by Mashallah Golestani-Nejad.<ref> Kosher Delight</ref> In August 2000, Cohen met with Iranian President ] for the first time.<ref> BBC</ref> In 2003, Cohen and Motamed met with Khatami at ], which was the first time a President of Iran had visited a synagogue since the ].<ref name="iranjewish.com"> Iran Jewish</ref> ] is the chairman of the Jewish Committee of Tehran and leader of Iran's Jewish community.<ref name="iranjewish.com"/><ref> Kashrut Authorities in Iran and Around the World</ref> On 26 January 2007, Yashayaei's letter to President ] concerning his Holocaust denial comments brought about worldwide media attention.<ref> Radio Free Europe</ref><ref> Daily Times</ref><ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081018191614/http://www.monthlyreview.org/mrzine/aam030507.html |date=2008-10-18}} Monthly Review</ref><ref>{{Citation |title=Iran President on Holocaust Denial | date=23 September 2009 |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ITy8nGZmQ_g |access-date=2023-08-20 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Traveling to Israel is forbidden for all the citizens of Iran, mentioned very clearly on the last page of the passport, however according to ] in recent years, Iranian government has allowed the Jewish Iranians to visit their family members in Israel and that the government has also allowed those Iranians living in Israel to return to Iran for visit. | |||