| Revision as of 23:27, 30 January 2009 view sourceCosmos416 (talk | contribs)1,323 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:32, 30 January 2009 view source Cosmos416 (talk | contribs)1,323 editsmNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 214: | Line 214: | ||

| The ] reports that typical retail prices in Europe for cannabis varies from 2€ to 14€ per gram, with a majority of European countries reporting prices in the range 4–10€.<ref>{{cite book |author=European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction |title=Annual report: the state of the drugs problem in Europe |year=2008 |publisher=Office for Official Publications of the European Communities |location=Luxembourg |isbn=978-92-9168-324-6 |url=http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_64227_EN_EMCDDA_AR08_en.pdf |format=PDF|page=38 }}</ref> The ] claims in its 2008 World Drug Report that typical US retail prices are 15 dollars per gram (approximately $430 per ]).<ref>{{cite book |author=United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime |title=World drug report |year=2008 |publisher=United Nations Publications |location= |isbn=978-92-1-148229-4 |url=http://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2008/WDR_2008_eng_web.pdf |format=PDF|page=264 }}</ref> | The ] reports that typical retail prices in Europe for cannabis varies from 2€ to 14€ per gram, with a majority of European countries reporting prices in the range 4–10€.<ref>{{cite book |author=European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction |title=Annual report: the state of the drugs problem in Europe |year=2008 |publisher=Office for Official Publications of the European Communities |location=Luxembourg |isbn=978-92-9168-324-6 |url=http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_64227_EN_EMCDDA_AR08_en.pdf |format=PDF|page=38 }}</ref> The ] claims in its 2008 World Drug Report that typical US retail prices are 15 dollars per gram (approximately $430 per ]).<ref>{{cite book |author=United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime |title=World drug report |year=2008 |publisher=United Nations Publications |location= |isbn=978-92-1-148229-4 |url=http://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2008/WDR_2008_eng_web.pdf |format=PDF|page=264 }}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | ==Demographics== | ||

| ⚫ | {{further|], ]}} | ||

| ⚫ | {{Expand-section|date=November 2008}} | ||

| ⚫ | {{clear}} | ||

| == Medical use == | == Medical use == | ||

| Line 243: | Line 238: | ||

| Another potential use for medical marijuana is movement disorders. Marijuana is frequently reported to reduce the muscle spasms associated with ]; this has been acknowledged by the ], but it noted that these abundant anecdotal reports are not well-supported by clinical data. Evidence from animal studies suggests that there is a possible role for cannabinoids in the treatment of certain types of epileptic seizures.<ref>{{cite book | author=Randall, Blanchard| title=Medical use of marijuana policy and regulatory issues| publisher=Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress| year=1992| id=OCLC 29975643}}</ref> A synthetic version of the major active compound in cannabis, THC, is available in capsule form as the prescription drug dronabinol (Marinol) in many countries. The prescription drug Sativex, an extract of cannabis administered as a ] spray, has been approved in Canada for the treatment of multiple sclerosis.<ref name="SativexC">{{cite web|author=Koch, W.|date=2005-06-23|url=http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2005-06-23-pot-spray_x.htm|title=Spray alternative to pot on the market in Canada|publisher=USA Today|accessdate=2007-02-27}}</ref> | Another potential use for medical marijuana is movement disorders. Marijuana is frequently reported to reduce the muscle spasms associated with ]; this has been acknowledged by the ], but it noted that these abundant anecdotal reports are not well-supported by clinical data. Evidence from animal studies suggests that there is a possible role for cannabinoids in the treatment of certain types of epileptic seizures.<ref>{{cite book | author=Randall, Blanchard| title=Medical use of marijuana policy and regulatory issues| publisher=Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress| year=1992| id=OCLC 29975643}}</ref> A synthetic version of the major active compound in cannabis, THC, is available in capsule form as the prescription drug dronabinol (Marinol) in many countries. The prescription drug Sativex, an extract of cannabis administered as a ] spray, has been approved in Canada for the treatment of multiple sclerosis.<ref name="SativexC">{{cite web|author=Koch, W.|date=2005-06-23|url=http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2005-06-23-pot-spray_x.htm|title=Spray alternative to pot on the market in Canada|publisher=USA Today|accessdate=2007-02-27}}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | ==Demographics== | ||

| ⚫ | {{further|], ]}} | ||

| ⚫ | {{Expand-section|date=November 2008}} | ||

| ⚫ | {{clear}} | ||

| == New breeding and cultivation techniques == | == New breeding and cultivation techniques == | ||

Revision as of 23:32, 30 January 2009

Template:Move and semi protected

| Cannabis | |

|---|---|

| |

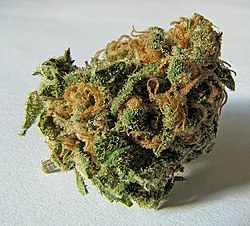

| A dried flowered bud of the Cannabis sativa plant. Note the visible trichomes (commonly referred to as crystals, or sometimes hairs), which carry a large portion of the drug content. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Cannabaceae |

| Genus: | Cannabis |

| Species: | C. sativa |

| Binomial name | |

| Cannabis sativa Linnaeus | |

| Subspecies | |

|

C. sativa L. subsp. sativa | |

Cannabis, also known as marijuana or marihuana, or ganja (from Hindi/Sanskrit: गांजा gānjā, hemp), is a psychoactive drug extracted from the plant Cannabis sativa, or more often, Cannabis sativa subsp. indica. The herbal form of the drug consists of dried mature flowers and subtending leaves of pistillate (female) plants. The resinous form, known as hashish, consists primarily of glandular trichomes collected from the same plant material. The major biologically active chemical compound in cannabis is Δ-tetrahydrocannabinol (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol), commonly referred to as THC.

Humans have been consuming cannabis since prehistory, although in the 20th century there was a rise in its use for recreational, religious or spiritual, and medicinal purposes. It is estimated that about four percent of the world's adult population (162 million) use cannabis annually and 0.6 percent (22.5 million) daily. The possession, use, or sale of psychoactive cannabis products became illegal in most parts of the world in the early 20th century. Since then, some countries have intensified the enforcement of cannabis prohibition while others have reduced the priority of enforcement.

Forms

Marijuana

- Marijuana or ganja: the flowering tops of female plants, from less than 1% THC to 22% THC; the wide range is probably one of the reasons for the conflicting results from different studies.

Psychoactive potency by cannabis plant part is approximately as follows (descending order):

- Trichomes

- Female flowering buds

- Male flowering buds

- New shoots

- Leaves from flower buds

- Leaves in ascending order of size

- Stems of leaves (petioles) in ascending order of size

- Stems in ascending order of size

- Roots and seeds

Hashish

- Hashish (pressed keif) or charas: a concentrated resin composed of heated glandular trichomes that have been physically extracted, usually by rubbing, sifting, or with ice.

Kief

Main article: Kief- Kief:

(1) The sticky resin saturated bits of plant before pressed into hashish.

(2) Moroccan hashish produced in the Rif mountains;

(3) sifted cannabis trichomes consisting of only the glandular "heads" (often incorrectly referred to as "crystals" or "pollen");

(4) the crystal (trichomes) left at the bottom of a grinder after grinding marijuana, then smoked.

Hash oil

Main article: Honey oilFor example, an ethanol extract of cannabis that has had the ethanol evaporated from it, to leave hash oil.

Resin

When marijuana is smoked because of THC's adhesive properties resin builds up inside the paraphernalia. It has tar-like properties and still contains THC as well as other cannibinoids. Resin still has all the psychoactive properties of marijuana but is harsher and less healthy on the lungs. Marijuana users typically only smoke resin as a last resort when they have run out of marijuana flowers.

Methods of consumption

Cannabis is consumed in many different ways, most of which either involve inhaling smoke from ignited plant or administering orally.

Various devices exist for smoking. The most common are implements such as bongs, chillums, bowls, joints and blunts. Local methods differ by the preparation of the cannabis plant before use, the parts of the cannabis plant which are used, and the treatment of the smoke before inhalation.

Vaporizer heats herbal cannabis to 365–410 °F (185–210 °C), which causes the active ingredients to evaporate into a gas without burning the plant material (the boiling point of THC is 392 °F (200°C) at 0.02 mmHg pressure, and somewhat higher at standard atmospheric pressure), A lower proportion of toxic chemicals are released than by smoking, although this may vary depending on the design of the vaporizer and the temperature at which it is set.

As an alternative to smoking, cannabis may be consumed orally. However, the cannabis or its extract must be sufficiently heated or dehydrated to cause decarboxylation of its most abundant cannabinoid, tetrahydrocannabinolic acid, into psychoactive THC.

Cannabis material can be leached in high-proof spirits (often grain alcohol) to create a “Green Dragon”. This process is often employed to make use of low-potency stems and leaves.

Cannabis can also be consumed as a cannabis tea. THC is lipophilic and only slightly water soluble (with a solubility of 2.8 mg per liter), so tea is made by first dissolving the active components in a fat such as milk, cream, butter, which is mixed with hot water to make a tea.

Effects

Main article: Effects of cannabis

Cannabis has psychoactive and physiological effects when consumed. The minimum amount of THC required to have a perceptible psychoactive effect is about 10 micrograms per kilogram of body weight. The most common short-term physical and neurological effects include increased heart rate, lowered blood pressure, impairment of psychomotor coordination, concentration, and short-term memory. Long-term effects are less clear.

Classification

Main article: Effects of cannabis § Psychoactive effectsWhile many drugs clearly fall into the category of either stimulant, depressant, hallucinogen, or antipsychotic, cannabis, containing both THC and CBD, exhibits a mix of all properties, leaning towards hallucinogen properties due to THC being the primary constituent.

Health issues

Smoking of cannabis is the most harmful method of consumption, since the combination of inhalation of smoke from organic materials such as tobacco, wood, gasoline and cannabis can cause various health problems. However, recent studies have shown that using a vaporizer for cannabis consumption appears to eliminate almost all of the health problems and objections related to cannabis use.

A 2007 study by the Canadian government found cannabis smoke contained more toxic substances than tobacco smoke. The study determined that marijuana smoke contained 20 times more ammonia, and five times more hydrogen cyanide and nitrogen oxides than tobacco smoke. In spite of this, recent studies have been unable to demonstrate a direct link between lung cancer and frequent direct inhalation of marijuana smoke. While many researchers have failed to find a correlation, some researchers still conclude that marijuana smoke poses a higher risk of lung cancer than tobacco. Some studies have even shown that the non-psychoactive ingredient CBD found in marijuana may be useful in treating breast cancer.

Cannabis use has been assessed by several studies to be correlated with the development of anxiety, psychosis and depression, however, no causal mechanism has been proven, and the meaning of the correlation and its direction is a subject of debate that has not been resolved in the scientific community. Some studies assess that the causality is more likely to involve a path from cannabis use to psychotic symptoms rather than a path from psychotic symptoms to cannabis use, while others assess the opposite direction of the causality, or hold cannabis to only form parts of a "causal constellation", while not inflicting mental health problems that would not have occurred in the absence of the cannabis use.

Studies have also shown links between heavy long-term use (over five joints daily over several years) and incidence of heart attacks, strokes, as well as abnormalities in the amygdala and hippocampus regions of the brain.

Gateway drug theory

Further information: ]Some claim that trying marijuana increases the probability that users will eventually use harder drugs. This hypothesis has been one of the central pillars of cannabis drug policy in the United States, though the validity and implications of these hypotheses are highly debated. Studies have shown that tobacco smoking is a better predictor of concurrent illicit hard drug use than smoking cannabis.

A 2005 comprehensive review of the literature on the cannabis gateway hypothesis found that pre-existing traits may predispose users to addiction in general, the availability of multiple drugs in a given setting confounds predictive patterns in their usage, and drug sub-cultures are more influential than cannabis itself. The study called for further research on "social context, individual characteristics, and drug effects" to discover the actual relationships between cannabis and the use of other drugs.

The main variant of the gateway hypothesis is that people, upon trying cannabis for the first time and not finding it dangerous, are then tempted to try other, harder drugs. In such a scenario, a new user of cannabis who feels there is a difference between anti-drug information and their own experiences will apply this distrust to public information of other, more powerful drugs. Some studies state that while there is little absolute proof for this gateway theory, young cannabis users should still be considered as a risk group for intervention programs. Other findings indicate that hard drug users are likely to be "poly-drug" users, and that interventions must address the use of multiple drugs instead of a single hard drug.

Another gateway hypothesis is that while cannabis is not as harmful or addictive as any other drugs, a gateway effect may be detected as a result of the "common factors" involved with using any illegal drug. Because of its illegal status, cannabis users are more likely to be in situations which allow them to become acquainted with people who use and sell other illegal drugs. By this argument, some studies have shown that alcohol and tobacco may also be regarded as gateway drugs. At least one source has suggested that the practice of mixing tobacco with cannabis can be a gateway to nicotine dependence.

History

Evidence of the inhalation of cannabis smoke can be found as far back as the 3rd millennium BC as indicated by charred cannabis seeds found in a ritual brazier at an ancient burial site in present day Romania. The most famous users of cannabis were the ancient Hindus of India and Nepal. The herb was called ganjika in Sanskrit (गांजा/গাঁজা ganja in modern Indic languages). The ancient drug soma, mentioned in the Vedas as a sacred intoxicating hallucinogen, was sometimes associated with cannabis.

Cannabis was also known to the ancient Assyrians, who discovered its psychoactive properties through the Aryans. Using it in some religious ceremonies, they called it qunubu (meaning "way to produce smoke"), a probable origin of the modern word 'Cannabis'. Cannabis was also introduced by the Aryans to the Scythians and Thracians/Dacians, whose shamans (the kapnobatai—“those who walk on smoke/clouds”) burned cannabis flowers to induce a state of trance. Members of the cult of Dionysus, believed to have originated in Thrace (Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey), are also thought to have inhaled cannabis smoke. In 2003, a leather basket filled with cannabis leaf fragments and seeds was found next to a 2,500- to 2,800-year-old mummified shaman in the northwestern Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China.

Cannabis has an ancient history of ritual use and is found in pharmacological cults around the world. Hemp seeds discovered by archaeologists at Pazyryk suggest early ceremonial practices like eating by the Scythians occurred during the 5th to 2nd century BCE, confirming previous historical reports by Herodotus. Some users have claimed that cannabis was used as a religious sacrament by ancient Jews and early Christians due to the similarity between the Hebrew word qannabbos (cannabis) and the Hebrew phrase qené bósem (aromatic cane). It was used by Muslims in various Sufi orders as early as the Mamluk period, for example by the Qalandars.

Today, recreational use in the Western world drives a sizable demand for the drug. Cannabis is the largest cash crop in the United States, generating an estimated $36 billion market.

The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction reports that typical retail prices in Europe for cannabis varies from 2€ to 14€ per gram, with a majority of European countries reporting prices in the range 4–10€. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime claims in its 2008 World Drug Report that typical US retail prices are 15 dollars per gram (approximately $430 per ounce).

Medical use

Main article: Medical cannabisA synthetic form of one chemical in marijuana, Δ-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), is used as a treatment for a wide range of medical conditions.

In the United States, the FDA has approved marijuana as a treatment for cancer and the symptoms of HIV and influenza. However, comparable authorities in Western Europe, including the Netherlands, have not approved smoked marijuana for any condition or disease. The current view of the United States Food and Drug Administration is that the consumption of isolated compounds (such as cannabinoids) is more effective than smoking or ingesting parts of the plant.

Russo and Grotenhermen report:

- Cannabis is established to help with

- Nausea and vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss.

- Cannabis is well-confirmed in treating

- spasticity, painful conditions, especially neurogenic pain, movement disorders, asthma, glaucoma.

Many other conditions are also indicate cannabis for relief or treatment, but are less confirmed.

Clinical trials conducted by the American Marijuana Policy Project, a pro-cannabis organization, have shown the efficacy of cannabis as a treatment for cancer and AIDS patients, who often suffer from clinical depression, and from nausea and resulting weight loss due to chemotherapy and other aggressive treatments.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). A synthetic version of the cannabinoid THC named dronabinol has been shown to relieve symptoms of anorexia and reduce agitation in elderly Alzheimer's patients. Dronabinol has been approved for use with anorexia in patients with HIV/AIDS and chemotherapy-related nausea. This drug, while demonstrating the effectiveness of cannabis at combating several disorders, is more expensive and less available than "pot" and has not been shown to be effective or safe.

Glaucoma, a condition of increased pressure within the eyeball causing gradual loss of sight, can be treated with medical marijuana to decrease this intraocular pressure. There has been debate for 25 years on the subject. Some data exist, showing a reduction of IOP in glaucoma patients who smoke marijuana, but the effects are short-lived, and the frequency of doses needed to sustain a decreased IOP can cause systemic toxicity. There is also some concern over its use since it can also decrease blood flow to the optic nerve. Marijuana lowers IOP by acting on a cannabinoid receptor on the ciliary body called the CB receptor. Although marijuana is not a good therapeutic choice for glaucoma patients, it may lead researchers to more effective, safer treatments. A promising study shows that agents targeted to ocular CB receptors can reduce IOP in glaucoma patients who have failed other therapies.

Medical marijuana is also used for analgesia, or pain relief. It is also reported to be beneficial for treating certain neurological illnesses such as epilepsy, and bipolar disorder. Case reports have found that cannabis can relieve tics in people with obsessive compulsive disorder and Tourette syndrome. Patients treated with tetrahydrocannabinol, the main psychoactive chemical found in cannabis, reported a significant decrease in both motor and vocal tics, some of 50% or more. Some decrease in obsessive-compulsive behavior was also found. A recent study has also concluded that cannabinoids found in cannabis might have the ability to prevent Alzheimer's disease. THC has been shown to reduce arterial blockages.

Another potential use for medical marijuana is movement disorders. Marijuana is frequently reported to reduce the muscle spasms associated with multiple sclerosis; this has been acknowledged by the Institute of Medicine, but it noted that these abundant anecdotal reports are not well-supported by clinical data. Evidence from animal studies suggests that there is a possible role for cannabinoids in the treatment of certain types of epileptic seizures. A synthetic version of the major active compound in cannabis, THC, is available in capsule form as the prescription drug dronabinol (Marinol) in many countries. The prescription drug Sativex, an extract of cannabis administered as a sublingual spray, has been approved in Canada for the treatment of multiple sclerosis.

Demographics

Further information: ]| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . (November 2008) |

New breeding and cultivation techniques

It is often claimed by growers and breeders of herbal cannabis that advances in breeding and cultivation techniques have increased the potency of cannabis since the late 1960s and early '70s, when Δ-tetrahydrocannabinol was discovered and understood. However, potent seedless marijuana such as "Thai sticks" were already available at that time. In fact, the sinsemilla technique of producing high-potency marijuana has been practiced in India for centuries. Sinsemilla (Spanish for "without seed") is the dried, seedless inflorescences of female cannabis plants. Because THC production drops off once pollination occurs, the male plants (which produce little THC themselves) are eliminated before they shed pollen to prevent pollination. Advanced cultivation techniques such as hydroponics, cloning, high-intensity artificial lighting, and the sea of green method are frequently employed as a response (in part) to prohibition enforcement efforts that make outdoor cultivation more risky. These intensive horticultural techniques have led to fewer seeds being present in cannabis and a general increase in potency over the past 20 years. The average levels of THC in marijuana sold in United States rose from 3.5% in 1988 to 7% in 2003 and 8.5% in 2006.

"Skunk" cannabis is a potent strain of cannabis, grown through selective breeding and usually hydroponics, that is a cross-breed of Cannabis sativa and C. indica. Skunk cannabis potency ranges usually from 6% to 15% and rarely as high as 20%. The average THC level in coffeehouses in the Netherlands is about 18–19%.

The average THC content of Skunk #1 is 8.2%; it is a 4-way combination of the cannabis strains Afghani indica, Mexican Gold, Colombian Gold, and Thai: 75% sativa, 25% indica. This was done via extensive breeding by cultivators in California in the 1970s using the traditional outdoor cropping methods used for centuries.

In proposed revisions to cannabis rescheduling in the UK, the government is considering rescheduling cannabis back from C to B. One of the reasons is the high-potency marijuana.

A Dutch double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study examining male volunteers aged 18–45 years with a self-reported history of regular cannabis use concluded that smoking of cannabis with high THC levels (marijuana with 9–23% THC), as currently sold in coffee shops in the Netherlands, may lead to higher THC blood-serum concentrations. This is reflected by an increase of the occurrence of impaired psychomotor skills, particularly among younger or inexperienced cannabis smokers, who do not adapt their smoking-style to the higher THC content. High THC concentrations in cannabis was associated with a dose-related increase of physical effects (such as increase of heart rate, and decrease of blood pressure) and psychomotor effects (such as reacting more slowly, being less concentrated, making more mistakes during performance testing, having less motor control, and experiencing drowsiness). It was also observed during the study that the effects from a single joint at times lasted for more than eight hours. Reaction times remained impaired five hours after smoking, when the THC serum concentrations were significantly reduced, but still present. The researchers suggested that THC may accululate in blood-serum when cannabis is smoked several times per day.

Another study showed that consumption of 15 mg of Δ-THC resulted in no learning whatsoever occurring over a three-trial selective reminding task after two hours. In several tasks, Δ-THC increased both speed and error rates, reflecting “riskier” speed–accuracy trade-offs.

Various strains of Marijuana

There are hundreds of named strains of Cannabis, but their origins (particularly the drug varieties) are often shrouded in mystery. The names of many legendary strains, such as Panama Red and Purple Haze, are ubiquitous in the pop-culture, but the origins of some of these infamous strains, such as G-13, are acknowledged to be urban legends, and some people even doubt their existance.

Strains of Cannabis:

- Acapulco gold

- BC Bud

- Cinderella 99

- Chocolate Thai

- Panama Red

- G-13

- Kush

- Northern Lights

- Purple Haze

- Quebec Gold

- White Widow

The names of some strains have become embedded in the mass culture. For example, Chocolate Thai, which was popular in the early 1990s due to its supposed high potency,was adopted as the stage name of a jazz performer whose album The Real McCoy was released in 2006. It should be noted, however, that because there is no state control over the production or sale of Cannabis, many "strains" may in fact be just marketing brands adopted by drug dealers to increase sales.

Legal status

Main article: Legality of cannabis See also: Drug prohibition and Drug liberalization

Since the beginning of the 20th century, most countries have enacted laws against the cultivation, possession, or transfer of cannabis for recreational use. These laws have impacted adversely on the cannabis plant's cultivation for non-recreational purposes, but there are many regions where, under certain circumstances, handling of cannabis is legal or licensed. Many jurisdictions have lessened the penalties for possession of small quantities of cannabis, so that it is punished by confiscation or a fine, rather than imprisonment, focusing more on those who traffic the drug on the black market.

In some areas where cannabis use has been historically tolerated, some new restrictions have been put in place, such as the closing of coffee shops near the borders of the Netherlands, closing of coffes shops near secondary schools in the Netherlands and crackdowns on "Pusher Street" in Christiania, Copenhagen in 2004.

Some jurisdictions use free voluntary treatment programs and/or mandatory treatment programs for frequent known users. Simple possession can carry long prison terms in some countries, particularly in East Asia, where the sale of cannabis may lead to a sentence of life in prison or even execution.

Religious use

Main article: Spiritual use of cannabisIn India and Nepal, cannabis has been used by some of the wandering Hindu spiritual sadhus for centuries, and in modern times the Rastafari movement has embraced it as a sacrament. Elders of the modern religious movement known as the Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church consider cannabis to be the Eucharist, claiming it as an oral tradition from Ethiopia dating back to the time of Christ, even though the movement was founded in the United States in 1975 and has no ties to either Ethiopia or the Coptic Church. Like the Rastafari, some modern Gnostic Christian sects have asserted that cannabis is the Tree of Life. Other organized religions founded in the 20th century that treat cannabis as a sacrament are the THC Ministry, the Way of Infinite Harmony, Cantheism, the Cannabis Assembly and the Church of Cognizance.

Truth serum

Cannabis was used as a truth serum by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a US government intelligence agency formed during World War II. In the early 1940s, it was the most effective truth drug developed at the OSS labs at St. Elizabeths Hospital; it caused a subject "to be loquacious and free in his impartation of information."

In May 1943, Major George Hunter White, head of OSS counter-intelligence operations in the US, arranged a meeting with Augusto Del Gracio, an enforcer for gangster Lucky Luciano. Del Gracio was given cigarettes spiked with THC concentrate from cannabis, and subsequently talked openly about Luciano's heroin operation. On a second occasion the dosage was increased such that Del Gracio passed out for two hours.

Adulterants

Adulterants in cannabis are less common than in other drugs of abuse. Chalk (in the Netherlands) and glass particles (in the UK) have been used at times to make marijuana appear to be higher quality. Increasing the weight of hashish products in Germany with lead caused lead intoxication in at least 29 cannabis users. In the Netherlands two chemical analogs of Sildenafil (Viagra) were found in adulterated marihuana.

Occasionally, claims have been made that a 'hard drug' (such as heroin or cocaine) is added to cannabis, possibly in order to get the users addicted to a drug that is less addictive. However, this is considered a myth as the 'hard drugs' usually cost more gram-for-gram than 'soft drugs' so the dealer would lose money on such an operation.

See also

- 1937 Marihuana Tax Act

- Cannabis political parties

- Cannabis use disorders

- Emerald Triangle

- Fitz Hugh Ludlow ("The Hasheesh Eater")

- Global Marijuana March

- Head shop

- International Opium Convention

- Intravenous Marijuana Syndrome

- Legality of cannabis by country

- Medical Marijuana Dispensary

- List of cannabis strains

- Marc Emery

- Marijuana (etymology)

- Marijuana Policy Project

- National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws

- Nederwiet

- Proposition 215

- Hemp

- Hemp oil

- THC

References

- Compact Oxford Dictionary definition

- derived from the Spanish, also spelled "mariguana", which is of unknown origin (Spanish Word Histories and Mysteries. p. 142.)

- The Oxford English Dictionary. Any of various preparations of different parts of the cannabis-plant which are smoked, chewed, sniffed or drunk for their intoxicating or hallucinogenic properties and were formerly used medicinally; bhang (marijuana), ganja, and charas (hashish) are different forms of these preparations." It is also notes that "cannabis" was elliptical reference (i.e. slang) for Cannabis sativa.

- Matthew J. Atha - Independent Drug Monitoring Unit. "Types of Cannabis Available in the UK". Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ Rudgley, Richard (1998). Lost Civilisations of the Stone Age. ISBN 0-6848-5580-1.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2006), "Cannabis: Why we should care" (PDF), World Drug Report, 1, ISBN 9-2114-8214-3, retrieved 2006-10-10 p.14

- "Marijuana- Definitions from Dictionary.com". dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- "Marijuana Potency". 64.233.167.104. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- "Hashish - Definitions from Dictionary.com". dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- Zijlma, Anouk. "Smoking hashish in Morocco". About.com. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- "Pipe Residue Information". Retrieved 2004-08-25.

- "Air Temperature Table" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-09-22.. Volcano Operating Manual. Storz & Bickel, Tuttlingen, Germany.

- 1989. The Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck & Co., Rahway, New Jersey

- "Does marijuana have to be heated to become psychoactive?"

- "ChemIDplus Lite". chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2008-08-08.

- http://www.marijuanalibrary.org/brain2.txt

- McKim, William A (2002). Drugs and Behavior: An Introduction to Behavioral Pharmacology (5th Edition). Prentice Hall. p. 400. ISBN 0-13-048118-1.

- "Information on Drugs of Abuse". Commonly Abused Drug Chart.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Stafford, Peter (1992). Psychedelics Encyclopedia. ISBN 0914171518. Cite error: The named reference "Stafford" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

-

"Harm Reduction Journal". harmreductionjournal.com. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

{{cite web}}: Text "Decreased respiratory symptoms in cannabis users who vaporize" ignored (help); Text "Full text" ignored (help) - "Vaporizers for Medical Marijuana". www.aids.org. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- "The Haworth Press Online Catalog: Article Abstract". www.haworthpress.com. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- Abrams DI, Vizoso HP, Shade SB, Jay C, Kelly ME, Benowitz NL (2007). "Vaporization as a smokeless cannabis delivery system: a pilot study". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 82 (5): 572–8. doi:10.1038/sj.clpt.6100200. PMID 17429350.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Evaluation of a vaporizing device (Volcano®) for the pulmonary administration of tetrahydrocannabinol". cat.inist.fr. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse" (PDF). Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Cannabis smoke 'has more toxins'". BBC. 2007-12-19.

- "Study Finds No Link Between Marijuana Use And Lung Cancer". Science Daily. 2006-05-26.

- "Study Finds No Cancer-Marijuana Connection". Washington Post. .

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Cannabis bigger cancer risk than cigarettes: study". Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- "Marijuana compound may stop spread of breast". Fox News. 2007-11-19.

- Henquet C, Krabbendam L, Spauwen J; et al. (2005). "Prospective cohort study of cannabis use, predisposition for psychosis, and psychotic symptoms in young people". BMJ. 330 (7481): 11. doi:10.1136/bmj.38267.664086.63. PMC 539839. PMID 15574485.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Lynskey M, Hall W (2002). "Cannabis use and mental health in young people: cohort study". BMJ. 325 (7374): 1195–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1195. PMC 135489. PMID 12446533.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM (2005). "Tests of causal linkages between cannabis use and psychotic symptoms". Addiction. 100 (3): 354–66. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01001.x. PMID 15733249.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hall, Wayne; Degenhardt, Lousia; Teesson, Maree. "Cannabis use and psychotic disorders: an update". Office of Public Policy and Ethics, Institute for Molecular Bioscience University of Queensland Australia, and National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre University of New South Wales Australia published in Drug and Alcohol Review (December 2004). Vol 23 Issue 4. Pg 433-443

- Arseneault, Louise; Cannon, Mary; Wiitton, John; Murray, Robin M. "Causal association between cannabis and psychosis:Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence". Institute of Psychiatry published in British Journal of Psychiatry (2004). #184, Pg. 110-117

- "Heavy pot smoking could raise risk of heart attack, stroke". CBC.

- "Long-term marijuana use linked to brain abnormalities". CBC.

- "RAND study casts doubt on claims that marijuana acts as "gateway" to the use of cocaine and heroin". RAND Corporation. 2002-12-02. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ Torabi MR, Bailey WJ, Majd-Jabbari M (1993). "Cigarette smoking as a predictor of alcohol and other drug use by children and adolescents: evidence of the "gateway drug effect"". The Journal of school health. 63 (7): 302–6. PMID 8246462.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Is cannabis a gateway drug? Testing hypotheses about the relationship between cannabis use and the use of other illicit drugs - UQ eSpace". espace.library.uq.edu.au. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- Saitz, Richard (2003-02-18). "Is marijuana a gateway drug?". Journal Watch. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- Degenhardt, Louisa; et al. (2007). "Who are the new amphetamine users? A 10-year prospective study of young Australians". Retrieved 2007-09-22.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Morral AR, McCaffrey DF, Paddock SM (2002). "Reassessing the marijuana gateway effect". Addiction. 97 (12): 1493–504. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00280.x. PMID 12472629.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Marijuana Policy Project- FAQ". Retrieved 2006-12-24.

- Australian Government Department of Health: National Cannabis Strategy Consultation Paper, page 4. "Cannabis has been described as a 'Trojan Horse' for nicotine addiction, given the usual method of mixing cannabis with tobacco when preparing marijuana for administration."

- Matthews, A.; Matthews, L. (2007), Learning Chinese Characters, p. 336

- Leary, Thimothy (1990). Tarcher/Putnam (ed.). Flashbacks. ISBN 0-8747-7870-0.

- Miller, Ga (1911), "Encyclopædia Britannica", Science (New York, N.Y.), 34 (883) (11th ed.): 761–762, doi:10.1126/science.34.883.761, PMID 17759460, retrieved 2006-06-15

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Rudgley, Richard (1998). Little, Brown and Company (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Substances. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- Franck, Mel (1997). Marijuana Grower's Guide. Red Eye Press. ISBN 0-9293-4903-2. p.3

- Rubin, Vera D. (1976). Cannabis and Culture. Campus Verlag. ISBN 3-5933-7442-0. p.305

- Cunliffe, Barry W. (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-1928-5441-0. p.405

- "Lab work to identify 2,800-year-old mummy of shaman". People's Daily Online. 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- Hong-En Jiang; et al. (2006). "A new insight into Cannabis sativa (Cannabaceae) utilization from 2500-year-old Yanghai tombs, Xinjiang, China". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 108 (3): 414–422. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2006.05.034. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Walton, Robert P. (1938). Marijuana, America's New Drug Problem. J. B. Lippincott. p.6

- "Cannabis linked to Biblical healing". Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- Ibn Taymiyya. Le haschich et l'extase. ISBN 2-8416-1174-4.

- "Marijuana Called Top U.S. Cash Crop". 2008 ABCNews Internet Ventures. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2008). Annual report: the state of the drugs problem in Europe (PDF). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. p. 38. ISBN 978-92-9168-324-6.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2008). World drug report (PDF). United Nations Publications. p. 264. ISBN 978-92-1-148229-4.

- Meyer, Robert J. "Testimony before the Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy, and Human Resources, Committee on Government Reform". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2007-09-15.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|title=at position 22 (help) - "Review of Therapeutic Effects". Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- "Cannabis lifts Alzheimer appetite". BBC. Retrieved 2007-09-15.

- Greenberg, Gary (2005-11-01). "Respectable Reefer". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- Merritt JC, Crawford WJ, Alexander PC, Anduze AL, Gelbart SS (1980). "Effect of marihuana on intraocular and blood pressure in glaucoma". Ophthalmology. 87 (3): 222–8. PMID 7053160.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Goldberg J, Flowerdew G, Smith E, Brody JA, Tso MO (1988). "Factors associated with age-related macular degeneration. An analysis of data from the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey". Am. J. Epidemiol. 128 (4): 700–10. PMID 3421236.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Porcella A, Maxia C, Gessa GL, Pani L. (2001). "The synthetic cannabinoid WIN55212-2 decreases the intraocular pressure in human glaucoma resistant to conventional therapies". Eur J Neurosci. 13 (13): 409–12. doi:10.1046/j.0953-816X.2000.01401.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Review of Therapeutic Effects". Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ K.R. Muller, U. Schneider, H. Kolbe, H.M. Emrich (1999). "Treatment of Tourette's Syndrome With Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol". American Journal of Psychiatry. 156 (3). Retrieved 2007-09-15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - K.R. Muller, U. Schneider, A. Koblenz, M. Jöbges, H. Kolbe, T. Daldrup, H.M. Emrich (2002). "Treatment of Tourette's Syndrome with Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC): A Randomized Crossover Trial". Pharmacopsychiatry. 35 (2): 57. doi:10.1055/s-2002-25028. Retrieved 2007-09-15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - R. Sandyk, G. Awerbuch (1988). "Marijuana and Tourette's Syndrome". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 8 (6): 444. doi:10.1097/00004714-198812000-00021. Retrieved 2007-09-15.

- Ramíirez, B. G., C. Blázquez, T. Gómez del Pulgar, M. Guzmán, and M. L. de Ceballos (2005). "Prevention of Alzheimer's disease pathology by cannabinoids: neuroprotection mediated by blockade of microglial activation". Journal of Neuroscience. 25 (8^): 1904–1913. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4540-04.2005. PMID 15728830. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Steffens S, Veillard NR, Arnaud C; et al. (2005). "Low dose oral cannabinoid therapy reduces progression of atherosclerosis in mice". Nature. 434 (7034): 782–6. doi:10.1038/nature03389. PMID 15815632.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Randall, Blanchard (1992). Medical use of marijuana policy and regulatory issues. Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress. OCLC 29975643.

- Koch, W. (2005-06-23). "Spray alternative to pot on the market in Canada". USA Today. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- "Marijuana sold in U.S. stronger than ever". MSNBC. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- "World Drug Report 2006". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 2008-02-25. Ch. 2.3

- BBC: Cannabis laws to be strengthened.May 2008 20:55 UK

- Tj. T. Mensinga; et al., A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study on the pharmacokinetics and effects of cannabis (PDF), RIVM, retrieved 2007-09-21

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Curran H.V.; et al. (2002). "Cognitive and subjective dose-response effects". NCBI. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Doorenbos, Norman J., Patricia S. Fetterman, Maynard W. Quimby, and Carlton Turner. 1971. Cultivation, extraction, and analysis of Cannabis sativa L. Annals New York Academy of Sciences 191: 3-14.

- Hirsch, Robert (1997). "Clinicians' self-assessment questions and answers in substance abuse treatment". Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 14 (1). Journal of Substance Abuse: 95–98. doi:10.1016/S0740-5472(97)00050-0.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Strains of Yesteryear" by DJ Short

- Answers.com album list

- Many Dutch coffee shops close as liberal policies change, Exaptica, 27/11/2007

- EMCDDA Cannabis reader: Global issues and local experiences, Perspectives on cannabis controversies, treatment and regulation in Europe, 2008, p.157]

- 43 Amsterdam coffee shops to close door, Radio Netherlands,Friday 21 November 2008

- Joseph Owens. Dread, The Rastafarians of Jamaica. ISBN 0-4359-8650-3.

- The Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church. "Marijuana and the Bible". Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- "Zion Light Ministry". Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- Chris Bennett, Lynn & Osburn, Judy Osburn (1938). Green Gold: the Tree of LifeMarijuana in Magic & Religion. Access Unlimited. p. 418. ISBN 0-9629-8722-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "The Hawai'i Cannabis Ministry". Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- "Cantheism". Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- "Cannabis Assembly". Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ Alexander Cockburn (1998). Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs and the Press. Verso. pp. 117–118. ISBN 1859841392.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Electronenmicroscopisch onderzoek van vervuilde wietmonsters" (PDF).

- "Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety - Contamination of herbal or 'skunk-type' cannabis with glass beads" (PDF).

- "Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety - Update on seizures of cannabis contaminated with glass particles" (PDF).

- Busse F, Omidi L, Timper K; et al. (2008). "Lead poisoning due to adulterated marijuana". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (15): 1641–2. doi:10.1056/NEJMc0707784. PMID 18403778.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Venhuis BJ, de Kaste D (2008). "Sildenafil analogs used for adulterating marihuana". Forensic Sci. Int. 182 (1–3): e23–4. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.09.002. PMID 18945564.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Louise Arsenault, Mary Cannon, Richie Poulton, Robin Murray, Avshalom Caspi, and Terrie E. Moffitt (2002). "Cannabis use in adolescence and risk for adult psychosis: longtudinal prospective study" (PDF). British Medical Journal. 325: 1212–1213. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1212. PMID 12446537.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Avshalom Caspi, Terrie E. Moffitt, Mary Cannon, Joseph McClay, Robin Murray, HonaLee Harrington, Alan Taylor, Louise Arsenault, Ben Williams, Antony Braithwaite, Richie Poulton, and Ian W. Craig (2005). "Moderation of the effect of adult-onset cannabis use on adult psychosis by a functional polymorphism in the Catchol-O-Methyltransferase gene: Longitudinal evidence of a gene X environment interaction" (PDF). Biol Psychiatry. 25: 1117–1127.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Henderson, Mark (2005-04-12). "One in four at risk of cannabis psychosis". The Times.

- Bruce Mirken and Neel Makwana (Aston Birmingham): "Psychosis, Hype And Baloney". AlterNet. 2005-03-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - James Huff and Po Chan (2000). "Antitumor Effects of THC". Environmental Health Perspectives. 108 (10): Correspondence. PMID 11097557.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Booth, Martin (2005). Cannabis: A History. ISBN 0-312-32220-8.

- Long term impact of Cannabis use of 16 year olds "Long-term impact of the Gatehouse Project on Cannabis use of 16-year-olds in Australia. (Research Papers)". journal of school health. 2004-01-01.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

External links

- Marijuana in Jamaica

- Report of the National Ganja Commission to the Jamaican Prime Minister

- Marijuana Policy Project

- National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws

- Wiktionary appendix of cannabis slang

- Various slang terms for cannabis

- Comprehensive Cannabis Faqs and Marijuana information

- Extensive list of notable cannabis users

- Debunking Myths about Marijuana Since 2002

- Research paper on the effects of marijuana

- The Report of the Canadian Government Commission of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs - 1972 - DRCNet Online Library of Drug Policy

- Marihuana Medical Access Regulations in Canada

- Pot Shrinks Tumors; Government Knew in '74

- University of Maryland, CECAR: Marijuana

- [http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/drugfact/marijuana/index.html

- Studies showing how Weed causes Paranoia and Psychosis

www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/drugfact/marijuana]

| Cannabis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | |||||||||

| Usage |

| ||||||||

| Variants | |||||||||

| Effects |

| ||||||||

| Culture | |||||||||

| Organizations |

| ||||||||

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Politics |

| ||||||||

| Related | |||||||||