| Revision as of 00:54, 24 March 2018 editSandyGeorgia (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, Mass message senders, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors278,969 edits →Essential features: =← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:57, 24 March 2018 edit undoDoc James (talk | contribs)Administrators312,277 edits restored videoNext edit → | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

| <!-- Epidemiology and prognosis --> | <!-- Epidemiology and prognosis --> | ||

| DLB is the third most common cause of dementia after Alzheimer's disease and ].<ref name=NIH2016Bas/> It typically begins after the age of 50.<ref name=NIH2016Bas/> About 0.1% of those over 65 are affected.<ref name=Dick2011>{{cite book|author=Dickson D, Weller RO |title=Neurodegeneration: The Molecular Pathology of Dementia and Movement Disorders|date=2011|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=9781444341232|page=|edition=2nd }}</ref> Men appear to be more commonly affected than women.<ref name=Walker2015/> In the late part of the disease, people may depend entirely on others for their care.<ref name=NIH2016Bas>{{cite web|title=What is Lewy Body Dementia?|url=https://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/lewy-body-dementia/basics-lewy-body-dementia|website=NIA|accessdate=22 March 2018|date=17 May 2017|}}</ref> Life expectancy following diagnosis is about eight years.<ref name=NIH2015/> The abnormal deposits that cause the disease were discovered in 1912 by ].<ref name=Kosaka2014>{{cite journal |vauthors=Kosaka K |title=Lewy body disease and dementia with Lewy bodies |journal=Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B, Phys. Biol. Sci. |volume=90 |issue=8 |pages=301–6 |date=2014 |pmid=25311140 |pmc=4275567 |type=Historical Review}}</ref> | DLB is the third most common cause of dementia after Alzheimer's disease and ].<ref name=NIH2016Bas/> It typically begins after the age of 50.<ref name=NIH2016Bas/> About 0.1% of those over 65 are affected.<ref name=Dick2011>{{cite book|author=Dickson D, Weller RO |title=Neurodegeneration: The Molecular Pathology of Dementia and Movement Disorders|date=2011|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=9781444341232|page=|edition=2nd }}</ref> Men appear to be more commonly affected than women.<ref name=Walker2015/> In the late part of the disease, people may depend entirely on others for their care.<ref name=NIH2016Bas>{{cite web|title=What is Lewy Body Dementia?|url=https://www.nia.nih.gov/alzheimers/publication/lewy-body-dementia/basics-lewy-body-dementia|website=NIA|accessdate=22 March 2018|date=17 May 2017|}}</ref> Life expectancy following diagnosis is about eight years.<ref name=NIH2015/> The abnormal deposits that cause the disease were discovered in 1912 by ].<ref name=Kosaka2014>{{cite journal |vauthors=Kosaka K |title=Lewy body disease and dementia with Lewy bodies |journal=Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B, Phys. Biol. Sci. |volume=90 |issue=8 |pages=301–6 |date=2014 |pmid=25311140 |pmc=4275567 |type=Historical Review}}</ref> | ||

| ] | |||

| {{TOC limit|3}} | {{TOC limit|3}} | ||

| ==Classification== | ==Classification== | ||

| Dementia with Lewy bodies is a progressive ] ];<ref name=Weil2017/> together with ], it is one of the ]s.<ref name=Gomperts2016/> Along with ], ], and other more rare conditions, they make up the ]—neurodegerative diseases that are due to an abnormal accumulation of ] protein in the brain.<ref name=Goedert2017>{{cite journal |vauthors=Goedert M, Jakes R, Spillantini MG |title=The Synucleinopathies: Twenty Years On |journal=J Parkinsons Dis |volume=7 |issue=s1 |pages=S53–S71 |date=2017 |pmid=28282814 |pmc=5345650 |doi=10.3233/JPD-179005 |type=Review}}</ref> | Dementia with Lewy bodies is a progressive ] ];<ref name=Weil2017/> together with ], it is one of the ]s.<ref name=Gomperts2016/> Along with ], ], and other more rare conditions, they make up the ]—neurodegerative diseases that are due to an abnormal accumulation of ] protein in the brain.<ref name=Goedert2017>{{cite journal |vauthors=Goedert M, Jakes R, Spillantini MG |title=The Synucleinopathies: Twenty Years On |journal=J Parkinsons Dis |volume=7 |issue=s1 |pages=S53–S71 |date=2017 |pmid=28282814 |pmc=5345650 |doi=10.3233/JPD-179005 |type=Review}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 00:57, 24 March 2018

Medical condition| Dementia with Lewy bodies | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Diffuse Lewy body disease, cortical Lewy body disease, senile dementia of Lewy type |

| |

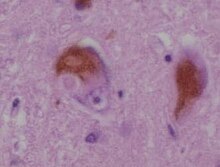

| A microscopic image of Lewy bodies | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Dementia, abnormal behavior during REM sleep, fluctuations in alertness, visual hallucinations, slowness of movement |

| Usual onset | After the age of 50 |

| Duration | Long term |

| Causes | Unknown |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after ruling out other conditions |

| Differential diagnosis | Parkinson's disease dementia, Alzheimer's disease |

| Medication | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil |

| Frequency | 0.1% (>65 years old) |

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a type of dementia that worsens over time, along with changes in behavior, cognition, and movement. Symptoms may include fluctuations in alertness, abnormal behavior during REM sleep, visual hallucinations, slowness of movement, trouble walking, and rigidity. Movements and abnormal behaviors during sleep are a core feature of DLB, called REM sleep behavior disorder. Mood changes such as depression are also common. DLB is classified as a neurodegenerative disorder. Together with Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD), it is one of two dementias referred to as the Lewy body dementias (LBD).

The cause is unknown. Typically, no family history of the disease exists among those affected. The underlying mechanism involves the buildup of Lewy bodies, clumps of alpha-synuclein protein in neurons. A diagnosis may be suspected based on symptoms, with blood tests and medical imaging done to rule out other possible causes. The differential diagnosis includes Parkinson's disease dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

At present there is no cure. Treatments are supportive and attempt to relieve some of the symptoms associated with the disease. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, may provide some benefit, and melatonin can be used for sleep symptoms. Antipsychotics, even for hallucinations, should generally be avoided due to potentially fatal risks and sensitivity for people with DLB to these medications.

DLB is the third most common cause of dementia after Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. It typically begins after the age of 50. About 0.1% of those over 65 are affected. Men appear to be more commonly affected than women. In the late part of the disease, people may depend entirely on others for their care. Life expectancy following diagnosis is about eight years. The abnormal deposits that cause the disease were discovered in 1912 by Frederic Lewy.

Classification

Dementia with Lewy bodies is a progressive neurogenerative dementia; together with Parkinson's disease dementia, it is one of the Lewy body dementias. Along with Parkinson's disease, multiple system atrophy, and other more rare conditions, they make up the synucleinopathies—neurodegerative diseases that are due to an abnormal accumulation of alpha-synuclein protein in the brain.

After Alzheimer's disease, LBD is the next most common dementia.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of DLB can be divided into essential, core and supportive features.

Essential features

Dementia is present, but does not always appear early on with DLB. It is more likely to appear as the condition progresses, typically after age 55. In contrast to Alzheimer's disease (AD), in which episodic memory loss related to encoding of memories is typically the earliest symptom, patients with LBD have better verbal memory, memory is affected later in the progression of the disease, and memory problems are related to retrieval of memories rather than encoding of new memories. Those with DLB experience impaired attention, executive function, and visuospatial function, that present as driving difficulty, such as becoming lost, misjudging distances, or as impaired job performance, difficulty multitasking, or inability to follow conversations. Difficulties with visuospatial processing show up earlier and are more pronounced in DLB than AD. Dementia is diagnosed when the "progressive cognitive decline of sufficient magnitude to interfere with normal social or occupational functions, or with usual daily activities".

Core features

While the specific symptoms in a person with DLB may vary, core features designated by the 2017 DLB Consortium are:

- fluctuating cognition, alertness or attention;

- REM sleep behavior disorder;

- "spontaneous cardinal features of parkinsonism"; and

- repeated visual hallucinations.

Core features are based on "their diagnostic specificity and the volume of good-quality evidence available".

Fluctuating cognition, alertness or attention

In AD, it is unclear if executive function is impacted early in the course of the disease; but in DLB, "marked attentional and executive function disturbance is central" and "attentional disturbance may serve as the basis of fluctuating cognition that is characteristic". Individuals with DLB may be easily distracted, and have a hard time focusing on tasks, or appear to be "delirium-like", "zoning out", or in states of altered consciousness. They may also exhibit disorganized speech, daytime sleepiness or drowsiness or napping, and changing ability to organize their thoughts during the day. Attention, thinking and alertness fluctuates throughout the day, and is often present early in the course of the disease.

REM sleep behavior disorder

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (23 March 2018) |

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) may appear decades before any other symptoms, and often is a symptom first recognized by the patient's caretaker. RBD includes vivid dreaming, with persistent dreams, purposeful or violent movements, and falling out of bed.

Parkinsonism

Parkinsonian features may include shuffling gait, reduced arm-swing during walking, blank expression (reduced range of facial expression), stiffness of movements, ratchet-like cogwheeling movements, low speech volume, sialorrhea, and difficulty swallowing.

Visual hallucinations

Up to 80% of people with DLB have visual hallucinations. They commonly involve perception of people or animals that are not there, and may reflect Lewy bodies or AD pathology in the temporal lobe. These hallucinations are not necessarily disturbing, and in some cases, the person with DLB may have insight into the hallucinations and even be amused by them, or be conscious they are not real. People with DLB also may have problems with vision and misinterpretation of what they see, for example, mistaking a pile of socks for snakes or a clothes closet for the bathroom.

Supportive features

According to the DLB Consortium, supporting features of DLB, "although carrying less diagnostic weight ... often ... as signposts to or evidence for a DLB diagnosis". They are:

- marked sensitivity to antipsychotics;

- marked dysautonomia (autonomic dysfunction);

- non-visual hallucinations;

- hypersomnia;

- hyposmia (reduced ability to smell)

- false beliefs and delusions organized around a common theme;

- "postural instability", loss of consciousness and frequent falls

- "apathy, anxiety and depression".

Antipsychotic sensitivity

One of the most critical supportive clinical features of the disease is hypersensitivity to neuroleptic and antiemetic medications that affect dopaminergic and cholinergic systems. In the worst cases, a patient treated with these medications could become catatonic, lose cognitive function, or develop life-threatening muscle rigidity. Some commonly used medications that should be used with great caution, if at all, for people with DLB, are chlorpromazine, haloperidol, or thioridazine.

Dysautonomia

Also, DLB patients often experience problems with orthostatic hypotension, including repeated falls, fainting, and transient loss of consciousness. Sleep-disordered breathing, a problem in multiple system atrophy, also may be a problem.

Benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, surgical anesthetics, some antidepressants, and over-the-counter (OTC) cold remedies may cause acute confusion, delusions, and hallucinations. Delusions may include reduplicative paramnesia and other elaborate misperceptions or misinterpretations.

Cause

The exact cause is not known, but DLB may have a genetic component; the DLB risk is heightened with inheritance of the ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E (APOE).

In DLB, loss of cholinergic (acetylcholine-producing) neurons is thought to account for degeneration of cognitive function (similar to Alzheimer's), while the death of dopaminergic (dopamine-producing) neurons appears to be responsible for degeneration of motor control (similar to Parkinson's) – in some ways, therefore, DLB resembles both disorders.

Pathophysiology

Pathologically, DLB is characterized by the development of abnormal collections of (alpha-synuclein) protein within the cytoplasm of neurons (known as Lewy bodies). These intracellular collections of protein have similar structural features to "classical" Lewy bodies, seen subcortically in Parkinson's disease. Additionally, those affected by DLB experience a loss of dopamine-producing neurons (in the substantia nigra) in a manner similar to that seen in Parkinson's disease.

A loss of acetylcholine-producing neurons (in the basal nucleus of Meynert and elsewhere) similar to that seen in Alzheimer's disease also is known to occur in those with DLB. Cerebral atrophy also occurs as the cerebral cortex degenerates. Autopsy series have revealed the pathology of DLB is often concomitant with the pathology of Alzheimer's disease. That is, when Lewy body inclusions are found in the cortex, they often co-occur with Alzheimer's disease pathology found primarily in the hippocampus, including senile plaques (deposited beta-amyloid protein), and granulovacuolar degeneration (grainy deposits within and a clear zone around hippocampal neurons). Neurofibrillary tangles (abnormally phosphorylated tau protein) are less common in DLB, although they are known to occur, and astrocyte abnormalities are also known to occur.

Diagnosis

Dementia with Lewy bodies is often misdiagnosed or confused in its early stages with Alzheimer's disease; in research settings, autopsy may reveal previously undiagnosed Lewy bodies in as many as half of Alzheimer's patients. Despite the difficulty in diagnosis, a prompt diagnosis is important because of the serious risks of sensitivity to certain neuroleptic (antipsychotic) medications and the need to inform both the person with DLB and the person's caregivers about potentially irreversible side effects of those medications.

Dementia sufficient to interfere with social or occupational functioning is required for a DLB diagnosis. Dementia is diagnosed based on patient history, physical exam, and assessment of neurological function, and by ruling out conditions that may cause similar symptoms—conditions like depression, abnormal thyroid function, or vitamin deficiencies.

In 2017, the Fourth Consensus Report of the DLB Consortium established diagnostic criteria for probable and possible DLB, in recognition of advances in detection and improvements from the earlier (2005) version. The 2017 criteria are based on core and supportive clinical features, and diagnostic biomarkers. The core clinical features (described in the Signs and symptoms section) are: fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, REM sleep behavior disorder, and signs of parkinsonism.

The diagnostic biomarkers are:

Indicative

- PET or SPECT showing reduced dopamine uptake in the basal ganglia,

- Abnormal iodine-MIBG myocardial scintigraphy,

- REM sleep without atonia evidenced on polysomnography, and

Supportive from PET, SPECT, CT, MRI or EEG brain studies showing:

- preserved medial temporal lobe,

- low dopamine transporter uptake,

- reduced occipital activity, or

- prominent slow-wave activity.

Probable DLB can be diagnosed when dementia and at least two core features are present, or one core feature with at least one indicative biomarker is present. Possible DLB can be diagnosed when dementia and only one core feature is present or if no core features are present, there is at least one indicative biomarker.

Dementia with Lewy bodies is distinguished from Parkinson's disease dementia (PDD) by the time frame in which dementia symptoms appear relative to Parkinson symptoms. PDD would be the diagnosis when dementia "occurs in the context of well-established Parkinson disease"; that is, typically (in a research setting) the onset of dementia is more than a year after the onset of Parkinsonian symptoms. DLB is diagnosed when cognitive symptoms begin before or at the same time as parkinsonism.

DLB is listed in the DSM-5 as "Major or Mild Neurocognitive Disorder with Lewy Bodies." The differences between the two sets of criteria are:

- the DSM does not include low dopamine transporter uptake as a supportive feature, and

- there is unclear diagnostic weight assigned to biomarkers in the DSM.

In terms of cognitive testing, individuals may have problems with figure copying as a result of visuospatial impairment, with clock-drawing due to executive function impairment, and difficulty with serial sevens as a result of impaired attention.

Management

No cure for dementia with Lewy bodies is known. Treatment may offer symptomatic benefit, but remains palliative in nature. Management of DLB can be difficult because of the need to balance cognitive function, neuropsychiatric features and impairments related to the motor system. Treatment modalities are divided into pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical.

Medications

Pharmaceutical management, as with Parkinson's disease, involves striking a balance between treating the motor, emotive, and cognitive symptoms. Motor symptoms appear to respond somewhat to the medications used to treat Parkinson's disease (e.g. levodopa), while cognitive issues may improve with medications for Alzheimer's disease such as donepezil. Medications for both Parkinson's disease and ADHD increase levels of the chemical dopamine in the brain, so increase the risk of hallucinations with those classes of pharmaceuticals.

Treatment of the movement and cognitive portions of the disease may worsen hallucinations and psychosis, while treatment of hallucinations and psychosis with antipsychotics may worsen parkinsonian or ADHD symptoms in DLB, such as tremor or rigidity and lack of concentration or impulse control. There is strong evidence for the use of cholinesterase inhibitors as treatment for cognitive problems and donepezil (Aricept), rivastigmine (Exelon), and galantamine (Reminyl) may be recommended as a means to help with these problems and to slow or prevent the decline of cognitive function. DLB may be more responsive to donepezil than Alzheimer's disease. Memantine also may be useful. Levocarb may help with movement problems, but in some cases, as with dopamine agonists, may tend to aggravate psychosis in people with DLB. Clonazepam may help with rapid eye movement behavior disorder; table salt or antihypotensive medications may help with fainting and other problems associated with orthostatic hypotension. Botulinum toxin injections in the parotid glands may help with sialorrhea.

To improve daytime alertness, there is mixed evidence for stimulants such as methylphenidate and dextromethamphetamine; they can increase the risk of psychosis, although worsening of neuropsychiatric symptoms is not common. Modafinil and armodafinil are not always covered by insurance, but may be effective for daytime sleepiness. Extreme caution in the use of antipsychotic medication in people with DLB because of their sensitivity to these agents. When these medications must be used, atypical antipsychotics are preferred to typical antipsychotics; a very low dose should be tried initially and increased slowly, and patients should be carefully monitored for adverse reactions to the medications.

Due to hypersensitivity to neuroleptics, preventing DLB patients from taking these medications is important. People with DLB are at risk for neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a life-threatening illness, because of their sensitivity to these medications, especially the older typical antipsychotics, such as haloperidol. Other medications, including medications for urinary incontinence and the antihistamine medication diphenhydramine (Benadryl), also may worsen confusion.

REM sleep behavior disorder may be treated with melatonin or clonazepam.

Non-pharmaceutical and caregiving strategies

Because of the neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with DLB, the caregiver burden is higher than in Alzheimer's. DLB gradually renders people incapable of tending to their own needs, so caregiving is important and must be managed carefully over the course of the disease. Caring for people with DLB involves adapting the home environment, schedule, activities, and communications to accommodate declining cognitive skills and parkinsonian symptoms.

People with DLB may swing dramatically between good days, with high alertness and few cognitive or movement problems, and bad days, and the level of care they require thus may vary widely and unpredictably. Sharp changes in behavior may be due to the day-to-day variability of DLB, but they also may be triggered by changes in the schedule or home environment, or by physical problems, such as constipation, dehydration, bladder infection, injuries from falls, and other problems they may not be able to convey to caregivers. Potential physical problems always should be taken into consideration when an individual with DLB becomes agitated.

Visual hallucinations associated with DLB create a particular burden on caregivers. As hallucinations and delusions are not necessarily dangerous or troubling to the person with DLB, caregivers not disabusing patients of them may be best. Often, the best approach is benign neglect—acknowledging, but not encouraging or agreeing. Trying to talk the DLB patient out of his delusion may be frustrating to caregivers and discouraging to patients, sometimes provoking anger or dejection. When misperceptions, hallucinations, and the behaviors stemming from these become troublesome, caregivers should try to identify and eliminate environmental triggers, and perhaps, offer cues or "therapeutic white lies" to steer patients out of trouble. Physicians may prescribe low doses of atypical antipsychotics, such as quetiapine, for psychosis and agitation in DLB. A small clinical trial found that about half of DLB patients treated with low doses of quetiapine experienced a significant reduction in these symptoms. Unfortunately, several participants in the study had to discontinue treatment because of side effects, such as excessive daytime sleepiness or orthostatic hypotension.

Changes in the schedule or environment, delusions, hallucinations, misperceptions, and sleep problems also may trigger behavior changes. It can help people with DLB to encourage exercise, simplify the visual environment, stick to a routine, and avoid asking too much (or too little) of them. Speaking slowly and sticking to essential information improves communication. The potential for visual misperception and hallucinations, in addition to the risk of abrupt and dramatic swings in cognition and motor impairment, should put families on alert to the dangers of driving with DLB.

Prognosis

Mueller (2017) reports that individuals with DLB "might have a less favourable prognosis, with accelerated cognitive decline, shorter lifespan, and increased admission to residential care" relative to individuals with Alzheimer's.

Epidemiology

An estimated 10 to 15% of diagnosed dementias are Lewy body type, but estimates range as high as 24%. Dementia with Lewy bodies tends to be under-recognized. Dementia with Lewy bodies is slightly more prevalent in men than women. DLB increases in prevalence with age; the mean age at presentation is 75 years, although it is not uncommon for DLB to be diagnosed before the age of 65.

Dementia with Lewy bodies affects about one million individuals in the United States.

History

Frederic Lewy (1885–1950) was the first to discover the abnormal protein deposits ("Lewy body inclusions") in the early 1900s. Dementia with Lewy bodies was first described by Japanese psychiatrist and neuropathologist Kenji Kosaka in 1976. DLB became easier to diagnose in the 1980s after the discovery of alpha-synuclein staining first highlighted Lewy bodies in the cortex of post mortem brains of dementia patients.

DLB was included in the DSM-IV-TR (published in 2000) under "Dementia Due to Other General Medical Conditions."

Notable cases

- American actor and comedian Robin Williams died by suicide on August 11, 2014. Upon autopsy, he was found to have diffuse DLB. Williams had been diagnosed with Parkinson's disease prior to his death; he also had depression, anxiety, and increasing paranoia (all symptoms of DLB).

- The actress Estelle Getty, best known for her role in the television series The Golden Girls, suffered from DLB in her later years.

- Artist Donald Featherstone, creator of the plastic pink flamingo, died from the disease in 2015.

- Socialite, heiress and actress Dina Merrill died from DLB in 2017.

- Previously diagnosed with Parkinson's diseaseAmerican radio and television disc jockey and host Casey Kasem died from the disease in 2014.

- Canadian singer Pierre Lalonde died from Parkinson's disease in 2016; he was found to have suffered from DLB.

- Canadian ice hockey player Stan Mikita was diagnosed with DLB in January 2015.

- Jerry Sloan, American former professional basketball player and coach, announcing in 2016 that he has Parkinson's disease and DLB.

- Otis Chandler, former publisher of The Los Angeles Times, died from the disease in 2006.

- British author Mervyn Peake was diagnosed posthumously in a 2003 study published in JAMA Neurologyas having died (in 1968) from DLB.

References

- ^ McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. (July 2017). "Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium". Neurology (Review). 89 (1): 88–100. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058. PMC 5496518. PMID 28592453.

- ^ "What is Lewy Body Dementia?". NIA. 17 May 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "NINDS Dementia With Lewy Bodies Information Page". NINDS. 25 May 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "Diagnosing Lewy Body Dementia". NIA. 17 May 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Dickson D, Weller RO (2011). Neurodegeneration: The Molecular Pathology of Dementia and Movement Disorders (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 224. ISBN 9781444341232.

- ^ St Louis EK, Boeve BF (November 2017). "REM Sleep Behavior Disorder: Diagnosis, Clinical Implications, and Future Directions". Mayo Clin. Proc. (Review). 92 (11): 1723–1736. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.09.007. PMID 29101940.

- "Common Symptoms". NIA. 29 July 2016. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gomperts SN (April 2016). "Lewy Body Dementias: Dementia With Lewy Bodies and Parkinson Disease Dementia". Continuum (Minneap Minn) (Review). 22 (2 Dementia): 435–63. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000309. PMC 5390937. PMID 27042903.

- Pezzoli S, Cagnin A, Bandmann O, Venneri A (July 2017). "Structural and Functional Neuroimaging of Visual Hallucinations in Lewy Body Disease: A Systematic Literature Review". Brain Sci (Review). 7 (7). doi:10.3390/brainsci7070084. PMC 5532597. PMID 28714891.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Boot BP (2015). "Comprehensive treatment of dementia with Lewy bodies". Alzheimers Res Ther (Review). 7 (1): 45. doi:10.1186/s13195-015-0128-z. PMC 4448151. PMID 26029267.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Walker Z, Possin KL, Boeve BF, Aarsland D (October 2015). "Lewy body dementias". Lancet (Review). 386 (10004): 1683–97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00462-6. PMC 5792067. PMID 26595642.

- ^ Kosaka K (2014). "Lewy body disease and dementia with Lewy bodies". Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B, Phys. Biol. Sci. (Historical Review). 90 (8): 301–6. PMC 4275567. PMID 25311140.

- ^ Weil RS, Lashley TL, Bras J, Schrag AE, Schott JM (2017). "Current concepts and controversies in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease dementia and Dementia with Lewy Bodies". F1000Res (Review). 6: 1604. doi:10.12688/f1000research.11725.1. PMC 5580419. PMID 28928962.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Goedert M, Jakes R, Spillantini MG (2017). "The Synucleinopathies: Twenty Years On". J Parkinsons Dis (Review). 7 (s1): S53 – S71. doi:10.3233/JPD-179005. PMC 5345650. PMID 28282814.

- ^ Karantzoulis S, Galvin JE (November 2011). "Distinguishing Alzheimer's disease from other major forms of dementia". Expert Rev Neurother (Review). 11 (11): 1579–91. doi:10.1586/ern.11.155. PMC 3225285. PMID 22014137.

- St Louis EK, Boeve AR, Boeve BF (May 2017). "REM Sleep Behavior Disorder in Parkinson's Disease and Other Synucleinopathies". Mov. Disord. (Review). 32 (5): 645–658. doi:10.1002/mds.27018. PMID 28513079.

- Presti, MF; Schmeichel, AM; Low, PA; Parisi, JE; Benarroch, EE (February 2014). "Degeneration of brainstem respiratory neurons in dementia with Lewy bodies". Sleep. 37 (2): 373–78. doi:10.5665/sleep.3418. PMC 3900631. PMID 24501436.

- Marla Gearing; Michael Lynn, MS; Suzanne S. Mirra, MD (February 1999), "Neurofibrillary Pathology in Alzheimer Disease With Lewy Bodies", Archives of Neurology, 56 (2): 203–8, doi:10.1001/archneur.56.2.203, PMID 10025425, archived from the original on 2010-03-28

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Fujishiro H, Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, Smith GE, Graff-Radford NR, Uitti RJ, Wszolek ZK, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Parisi JE, Dickson DW (July 2008), "Validation of the neuropathologic criteria of the third consortium for dementia with Lewy bodies for prospectively diagnosed cases.", J Neuropathol Exp Neurol., 67 (7): 649–56, doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e31817d7a1d, PMC 2745052, PMID 18596548

- Tousi B (October 2017). "Diagnosis and Management of Cognitive and Behavioral Changes in Dementia With Lewy Bodies". Curr Treat Options Neurol (Review). 19 (11): 42. doi:10.1007/s11940-017-0478-x. PMID 28990131.

- "Diagnosing Dementia". NIA. 16 May 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Gomberts2016was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Carey RJ, Pinheiro-Carrera M, Dai H, Tomaz C, Huston JP (2014-05-14). "L-DOPA and psychosis:". Biological Psychiatry. 38 (10). NIH.gov: 669–76. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(94)00378-5. PMID 8555378.

- "Secondary parkinsonism". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. NIH.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-05-25. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Ellul, J (2006). "The effects of commonly prescribed drugs in patients with Alzheimer's disease on the rate of deterioration". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 78 (3): 233–239. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2006.104034.

- Velayudhan L, Ffytche D, Ballard C, Aarsland D (September 2017). "New Therapeutic Strategies for Lewy Body Dementias". Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep (Review). 17 (9): 68. doi:10.1007/s11910-017-0778-2. PMID 28741230.

- Neef D, Walling AD (2006). "Dementia with Lewy Bodies: an Emerging Disease". American Family Physician (Review). 73 (7): 1223–29. PMID 16623209. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Aarsland, D; Ballard, C; Walker, Z; Bostrom, F; Alves, G; Kossakowski, K; Leroi, I; Pozo-Rodriguez, F; et al. (2009), "Memantine in patients with Parkinson's disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial", Lancet Neurology, 8 (7): 613–8, doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70146-2, PMID 19520613

- ^ Boot BP, McDade EM, McGinnis SM, Boeve BF (December 2013). "Treatment of dementia with lewy bodies". Curr Treat Options Neurol (Review). 15 (6): 738–64. doi:10.1007/s11940-013-0261-6. PMC 3913181. PMID 24222315.

- ^ Mueller C, Ballard C, Corbett A, Aarsland D (May 2017). "The prognosis of dementia with Lewy bodies". Lancet Neurol (Review). 16 (5): 390–398. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30074-1. PMID 28342649.

- Ferman, Tanis J.; Lewy Body Dementia Association (2007), Behavioral Challenges in Dementia with Lewy Bodies, from 'The Many Faces of Lewy Body Dementia' series at Coral Springs Medical Center, FL, archived from the original on 2017-02-13

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Cheng ST (August 2017). "Dementia Caregiver Burden: a Research Update and Critical Analysis". Curr Psychiatry Rep (Review). 19 (9): 64. doi:10.1007/s11920-017-0818-2. PMC 5550537. PMID 28795386.

- Weintraub, Daniel; Hurtig, Howard I. (2007), "Presentation and Management of Psychosis in Parkinson's Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies", American Journal of Psychiatry, 164 (10): 1491–1498, doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040715, PMC 2137166, PMID 17898337

- Crystal, Howard A. (2008), "Dementia with Lewy Bodies", E-Medicine from WebMD, archived from the original on 2009-02-06

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "First drug for Dementia with Lewy bodies approved". AsianScientist. 23 September 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Kosaka K, Oyanagi S, Matsushita M, Hori A (1976). "Presenile dementia with Alzheimer-, Pick- and Lewy-body changes". Acta Neuropathol. 36 (3): 221–233. doi:10.1007/bf00685366. PMID 188300.

- "Robin Williams' widow blames Lewy body dementia - CNN.com". CNN. Archived from the original on 2015-11-04. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Susan Schneider Williams (2016-09-27). "The terrorist inside my husband's brain - neurology.org". Neurology. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000003162. Archived from the original on 2016-10-01. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - McKeith, Ian. "Robin Williams had dementia with Lewy Bodies -- so, what is it and why has it been eclipsed by Alzheimer's?". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-11-01.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Carlson, Michael (July 24, 2008). "Obituary: Estelle Getty". theguardian.com. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - "Don Featherstone Obituary - Miami, FL | the Miami Herald". Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-05-23. Retrieved 2017-05-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Kasem, Julie; Kasem, Kerri; Martin, Troy (2014-05-13). "Interview with Julie and Kerri Kasem". CNN Tonight (Interview). Interviewed by Bill Weir. CNN.

{{cite interview}}: Unknown parameter|subjectlink2=ignored (|subject-link2=suggested) (help) Comments about disease aired around 9:41 pm EDT; comments about purpose at the end of the interview. - "Pierre Lalonde est décédé à l'âge de 75 ans". Le Journal de Montréal. Retrieved 2016-06-22.

- "Pierre Lalonde souffrait aussi de la démence à corps de Lewy". Le Journal de Montréal. Retrieved 2016-06-22.

- Kuc, Chris (15 June 2015). "For Stan Mikita, all the Blackhawks memories are gone". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ESPN.com news services (April 6, 2016). "Hall of Fame coach Jerry Sloan battling Parkinson's disease, Lewy body dementia". espn.go.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Shaw, David; Mitchell Landsberg (February 27, 2006). "L.A. Icon Otis Chandler Dies at 78". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 26, 2007. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Demetrios J. Sahlas (2003). "Dementia With Lewy Bodies and the Neurobehavioral Decline of Mervyn Peake". Arch. Neurol. 60 (6): 889–92. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.6.889. PMID 12810496.

External links

- Video of updated diagnostic criteria from the Lewy Body Dementia Association, with Ian McKeith.

| Classification | D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Diseases of the nervous system, primarily CNS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammation |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brain/ encephalopathy |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Both/either |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||