| Revision as of 02:03, 19 April 2022 edit174.212.111.201 (talk)No edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:06, 19 April 2022 edit undo174.212.111.201 (talk)No edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app editNext edit → | ||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

| The ] was designed by ] and ] and built in 1847–48 by the ], of locally-quarried random ] ], except for three brick interior longitudinal ] walls and the concrete base of the piers. This may have been the first structural use of concrete in American bridge construction.{{Cn|date=January 2021}} | The ] was designed by ] and ] and built in 1847–48 by the ], of locally-quarried random ] ], except for three brick interior longitudinal ] walls and the concrete base of the piers. This may have been the first structural use of concrete in American bridge construction.{{Cn|date=January 2021}} | ||

| It was built to solve an engineering problem posed by the wide valley of Starrucca Creek. The railroad considered building an ], but abandoned the idea as impractical. The Erie Railroad was well-financed by British investors |

It was built to solve an engineering problem posed by the wide valley of Starrucca Creek. The railroad considered building an ], but abandoned the idea as impractical. The Erie Railroad was well-financed by British investors but, even with money available, most American contractors at the time were incapable of the task. Julius W. Adams, the superintending engineer of construction in the area, hired James P. Kirkwood, a civil engineer who had worked on the ]. Accounts differ as to whether Kirkwood worked on the bridge himself, or whether Adams was responsible for the plans with Kirkwood working as a subordinate. The lead stonemason, Thomas Heavey, an Irish immigrant from County Offaly, had worked on other projects for Kirkwood, primarily in New England. It took 800 workers, each paid about $1 per day, equal to ${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|1|1848|r=2}}}} today, to complete the bridge in a year. The ] for the bridge required more than half a million feet of cored and hewn timbers.{{Cn|date=January 2021}} | ||

| The original single ] track was replaced by two ] tracks in 1886. The roadbed deck under the tracks was reinforced with a layer of concrete in 1958.<ref name=HAERsurvey/> | The original single ] track was replaced by two ] tracks in 1886. The roadbed deck under the tracks was reinforced with a layer of concrete in 1958.<ref name=HAERsurvey/> | ||

| The bridge has been in continual use for more than a century and a half. In 2005, the ] leased the portion of the line from ] to ] |

The bridge has been in continual use for more than a century and a half. In 2005, the ] leased the portion of the line from ] to ] to the ], which operates it under the name ]. The only railroad currently using it is DO's ].{{Cn|date=April, 2022}} | ||

| The viaduct was designated as a ] by the ] in 1973 and was listed on the ] in 1975.<ref>{{cite book |last=Treese |first=Lorett |year=2003 |title=Railroads of Pennsylvania: Fragments of the Past in the Keystone Landscape |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lMK3DAAAQBAJ&pg=PA173 |location=Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania |publisher=Stackpole Books |page=173 |isbn=9780811743570 |accessdate=25 September 2021}}</ref> | The viaduct was designated as a ] by the ] in 1973 and was listed on the ] in 1975.<ref>{{cite book |last=Treese |first=Lorett |year=2003 |title=Railroads of Pennsylvania: Fragments of the Past in the Keystone Landscape |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lMK3DAAAQBAJ&pg=PA173 |location=Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania |publisher=Stackpole Books |page=173 |isbn=9780811743570 |accessdate=25 September 2021}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 02:06, 19 April 2022

Bridge in Lanesboro, Pennsylvania| Starrucca Viaduct | |

|---|---|

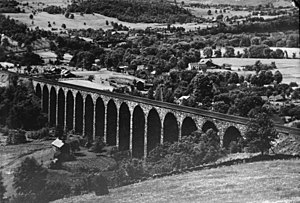

A 1920 picture of the Starrucca Viaduct. A 1920 picture of the Starrucca Viaduct. | |

| Coordinates | 41°57′47″N 75°35′00″W / 41.963159°N 75.583283°W / 41.963159; -75.583283 |

| Carries | Two tracks of the New York, Susquehanna and Western Railway |

| Crosses | Starrucca Creek |

| Locale | Lanesboro, Pennsylvania |

| Maintained by | New York, Susquehanna and Western Railway |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Stone arch bridge |

| Total length | 1,040 feet (320 m) |

| Width | Two tracks |

| Longest span | Seventeen spans of 50 feet (15 m) |

| Clearance below | 100 feet (30 m) |

| History | |

| Opened | 1848 |

| Location | |

Starrucca Viaduct is a stone arch bridge that spans Starrucca Creek near Lanesboro, Pennsylvania, in the United States. Completed in 1848 at a cost of $320,000 (equal to $11,268,923 today), it was at the time the world's largest stone railway viaduct and was thought to be the most expensive railway bridge as well. Still in use, the viaduct is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is designated as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.

Construction

The viaduct was designed by Julius W. Adams and James P. Kirkwood and built in 1847–48 by the New York and Erie Railroad, of locally-quarried random ashlar bluestone, except for three brick interior longitudinal spandrel walls and the concrete base of the piers. This may have been the first structural use of concrete in American bridge construction.

It was built to solve an engineering problem posed by the wide valley of Starrucca Creek. The railroad considered building an embankment, but abandoned the idea as impractical. The Erie Railroad was well-financed by British investors but, even with money available, most American contractors at the time were incapable of the task. Julius W. Adams, the superintending engineer of construction in the area, hired James P. Kirkwood, a civil engineer who had worked on the Long Island Rail Road. Accounts differ as to whether Kirkwood worked on the bridge himself, or whether Adams was responsible for the plans with Kirkwood working as a subordinate. The lead stonemason, Thomas Heavey, an Irish immigrant from County Offaly, had worked on other projects for Kirkwood, primarily in New England. It took 800 workers, each paid about $1 per day, equal to $35.22 today, to complete the bridge in a year. The falsework for the bridge required more than half a million feet of cored and hewn timbers.

The original single broad gauge track was replaced by two standard gauge tracks in 1886. The roadbed deck under the tracks was reinforced with a layer of concrete in 1958.

The bridge has been in continual use for more than a century and a half. In 2005, the Norfolk Southern Railway leased the portion of the line from Port Jervis to Binghamton, New York to the Delaware Otsego Corporation, which operates it under the name Central New York Railway. The only railroad currently using it is DO's New York, Susquehanna and Western Railway.

The viaduct was designated as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers in 1973 and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975.

-

Starruca Viaduct, Pennsylvania, 1865, by Jasper Francis Cropsey

Starruca Viaduct, Pennsylvania, 1865, by Jasper Francis Cropsey

-

October 2009

October 2009

-

October 2014

October 2014

See also

- List of bridges documented by the Historic American Engineering Record in Pennsylvania

- List of Erie Railroad structures documented by the Historic American Engineering Record

- List of Pennsylvania state historical markers in Susquehanna County

References

- "HAER survey drawings (sheet 1 of 3)". "HAER survey drawings (sheet 2 of 3)". "HAER survey drawings (sheet 3 of 3)". US Library of Congress. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- Treese, Lorett (2003). Railroads of Pennsylvania: Fragments of the Past in the Keystone Landscape. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. p. 173. ISBN 9780811743570. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. PA-6, "Erie Railway, Delaware Division, Bridge 189.46"

- Starrucca Viaduct at Structurae. Retrieved 2006-06-16.

- Plowden, David (2002). Bridges: The Spans of North America. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780393050561.

- American Society of Civil Engineers, Reston, VA. "Starrucca Viaduct." Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks. Accessed 2022-01-26.

- "Erie has Largest Stone Bridge" (PDF). Erie Railroad Magazine: 11. August 1939. Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- Brown, Jeff L. (January 2014). "Rock Solid: Stone Arch Bridges of the 1840s". Civil Engineering. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers: 44–47. ISSN 0885-7024.

External links

- Bridges to the Future at Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania's website

- Starrucca Viaduct at ASCE Civil Engineering Landmarks

- Starrucca Viaduct at Bridges & Tunnels

- Solid as a Rock: The Starrucca Viaduct at Literary & Cultural Heritage Map of PA

- Articles with unsourced statements from April, 2022

- Bridges completed in 1848

- Railroad bridges on the National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania

- Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks

- Railroad bridges in Pennsylvania

- Viaducts in the United States

- Bridges in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania

- Historic American Engineering Record in Pennsylvania

- Erie Railroad bridges

- National Register of Historic Places in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania

- Stone arch bridges in the United States