| Revision as of 04:03, 11 December 2023 view sourcePadFoot2008 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users9,665 edits Moved map of narrower definition to definitions section and fixed state banners and added union territories.Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit Disambiguation links added← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:04, 11 December 2023 view source PadFoot2008 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users9,665 edits Undid revision 1180895189 by ActivelyDisinterested (talk) Its not. There is no history of South India here.Tags: Undo harv-error Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit Disambiguation links addedNext edit → | ||

| Line 166: | Line 166: | ||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| === Ancient Era === | |||

| ⚫ | {{Main |

||

| ], composed in story-telling fashion {{circa|400 BC|300 BC}}<ref name="Lowe2017-epic">{{Cite book |last=Lowe |first=John J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nSgmDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA58 |title=Transitive Nouns and Adjectives: Evidence from Early Indo-Aryan |publisher=] |year=2017 |isbn=978-0-19-879357-1 |page=58 |quote=The term 'Epic Sanskrit' refers to the language of the two great Sanskrit epics, the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyaṇa. ... It is likely, therefore, that the epic-like elements found in Vedic sources and the two epics that we have are not directly related, but that both drew on the same source, an oral tradition of storytelling that existed before, throughout, and after the Vedic period.}}</ref>|right]] | |||

| By 55,000 years ago, the first modern humans, or '']'', had arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa, where they had earlier evolved.<ref name="PetragliaAllchin">{{harvnb|Petraglia|Allchin|2007|p=}}, "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by modern humans originating in Africa. ... Coalescence dates for most non-European populations average to between 73–55 ka."</ref><ref name="Dyson2018p1">{{harvnb|Dyson|2018|p=}}, "Modern human beings—''Homo sapiens''—originated in Africa. Then, intermittently, sometime between 60,000 and 80,000 years ago, tiny groups of them began to enter the north-west of the Indian subcontinent. It seems likely that initially they came by way of the coast. ... it is virtually certain that there were ''Homo sapiens'' in the subcontinent 55,000 years ago, even though the earliest fossils that have been found of them date to only about 30,000 years before the present."</ref><ref name="Fisher2018p23">{{harvnb|Fisher|2018|p=}}, "Scholars estimate that the first successful expansion of the ''Homo sapiens'' range beyond Africa and across the Arabian Peninsula occurred from as early as 80,000 years ago to as late as 40,000 years ago, although there may have been prior unsuccessful emigrations. Some of their descendants extended the human range ever further in each generation, spreading into each habitable land they encountered. One human channel was along the warm and productive coastal lands of the Persian Gulf and northern Indian Ocean. Eventually, various bands entered India between 75,000 years ago and 35,000 years ago."</ref> The earliest known modern human remains in South Asia date to about 30,000 years ago.<ref name="PetragliaAllchin" /> After 6500 BC, evidence for domestication of food crops and animals, construction of permanent structures, and storage of agricultural surplus appeared in ] and other sites in ].{{sfn|Coningham|Young|2015|pp = 104–105}} These gradually developed into the ],{{sfn|Kulke|Rothermund|2004|pp = 21–23}}{{sfn|Coningham|Young|2015|pp = 104–105}} the first urban culture in South Asia,{{sfn|Singh|2009|p = 181}} which flourished during 2500–1900 BC north-western Indian subcontinent.{{sfn|Possehl|2003|p = 2}} Centred around cities such as ], ], ], and ], and relying on varied forms of subsistence, the civilisation engaged robustly in crafts production and wide-ranging trade.{{sfn|Singh|2009|p = 181}} | |||

| === Vedic Era === | |||

| Between 2000 BC and 1500 BC, several waves of Indo-Aryan migrations from Central Asia occurred and these migrants settled in the Indo-Gangetic Plain. The ], the oldest scriptures associated with ],{{sfn|Singh|2009|pp = 186–187}} were composed during this period,{{sfn|Witzel|2003|pp = 68–69}} and historians have analysed these to posit a ] in the ] and the upper ].{{sfn|Singh|2009|p = 255}} During the period {{BCE|2000–500}}, many regions of the subcontinent transitioned from the ] cultures to the ] ones.{{sfn|Singh|2009|p = 255}} The ], which created a hierarchy of priests (]), warriors ], and commoners and peasants (] and ]), and but which excluded indigenous peoples by labelling their occupations impure, arose during this period (later referred to as ] or outcasts).{{Sfn|Kulke|Rothermund|2004|pp=41–43}} On the ], archaeological evidence from this period suggests the existence of a chiefdom stage of political organisation.{{Sfn|Singh|2009|p=255}} | |||

| In the late Vedic period, around the 6th century BCE, the small states and chiefdoms of the Ganges Plain and the north-western regions had consolidated into 16 major oligarchies and monarchies that were known as the '']''.{{sfn|Singh|2009|pp = 260–265}}{{sfn|Kulke|Rothermund|2004|pp = 53–54}} The emerging urbanisation gave rise to non-Vedic religious movements, two of which became independent religions. ] came into prominence during the life of its exemplar, ].{{sfn|Singh|2009|pp = 312–313}} ], based on the teachings of ], attracted followers from all social classes excepting the middle class; chronicling the life of the Buddha was central to the beginnings of recorded history in India.{{sfn|Kulke|Rothermund|2004|pp = 54–56}}{{sfn|Stein|1998|p = 21}}{{sfn|Stein|1998|pp = 67–68}} In an age of increasing urban wealth, both religions held up ] as an ideal,{{sfn|Singh|2009|p = 300}} and both established long-lasting monastic traditions. Politically, by the 3rd century BCE, the ] had annexed or reduced other states and evolved into the ] under the ].{{sfn|Singh|2009|p = 319}} The Magadhan Mauryan emperors are known as much for their empire-building and determined management of public life as for ]'s renunciation of militarism and far-flung advocacy of the Buddhist '']''.{{sfn|Singh|2009|p = 367}}{{sfn|Kulke|Rothermund|2004|p = 63}} | |||

| In North India, by the 4th and 5th centuries, the ] of Magadha had created a complex system of administration and taxation in the greater Ganges Plain; this system became a model for later Indian kingdoms.{{sfn|Kulke|Rothermund|2004|pp = 89–91}}{{sfn|Singh|2009|p = 545}} Under the Guptas, a renewed Hinduism based on devotion, rather than the management of ritual, began to assert itself.{{sfn|Stein|1998|pp = 98–99}} This renewal was reflected in a flowering of ] and ], which found patrons among an urban elite.{{sfn|Singh|2009|p = 545}} ] flowered as well, and ], ], ], and ] made significant advances.{{sfn|Singh|2009|p = 545}} | |||

| === Medieval Era === | |||

| {{multiple image|perrow=2|total_width=320 | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | image_style = border:none; | |||

| | title = | |||

| | image1 = Gopuram Corner View of Thanjavur Brihadeeswara Temple..JPG | |||

| | caption1 = ], ], completed in {{CE|1010}} | |||

| | image2 = Qutb minar ruins.jpg | |||

| | caption2 = The ], {{convert|73|m|ft|0|abbr=on}} tall, completed by the ], ] | |||

| }} | |||

| The Indian early medieval age, from 600 to 1200 AD, is defined by regional kingdoms and cultural diversity.{{sfn|Stein|1998|p = 132}} When ] of ], who ruled much of the Indo-Gangetic Plain from {{CE|606 to 647}}, attempted to expand southwards, he was defeated by the ] ruler of the Deccan.{{sfn|Stein|1998|pp = 119–120}} When his successor attempted to expand eastwards, he was defeated by the ] king of ].{{sfn|Stein|1998|pp = 119–120}} No ruler of this period was able to create an empire and consistently control lands much beyond their core region.{{sfn|Stein|1998|p = 132}} During this time, pastoral peoples, whose land had been cleared to make way for the growing agricultural economy, were accommodated within caste society, as were new non-traditional ruling classes.{{sfn|Stein|1998|pp = 121–122}} The caste system consequently began to show regional differences.{{sfn|Stein|1998|pp = 121–122}} | |||

| In the 6th and 7th centuries, the first ] were created in the Tamil language.{{sfn|Stein|1998|p = 123}} They were imitated all over India and led to both the resurgence of Hinduism and the development of all ].{{sfn|Stein|1998|p = 123}} Indian royalty, big and small, and the temples they patronised drew citizens in great numbers to the capital cities, which became economic hubs as well.{{sfn|Stein|1998|p = 124}} Temple towns of various sizes began to appear everywhere as India underwent another urbanisation.{{sfn|Stein|1998|p = 124}} By the 8th and 9th centuries, the effects were felt in South-East Asia, as South Indian culture and political systems were exported to lands that became part of modern-day ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].{{sfn|Stein|1998|pp = 127–128}} Indian merchants, scholars, and sometimes armies were involved in this transmission; South-East Asians took the initiative as well, with many sojourning in Indian seminaries and translating Buddhist and Hindu texts into their languages.{{sfn|Stein|1998|pp = 127–128}} | |||

| After the 10th century, Muslim Central Asian nomadic clans, using ] cavalry and raising vast armies united by ethnicity and religion, repeatedly overran South Asia's north-western plains. A general ] declared his independence and established the ] in 1206.{{sfn|Ludden|2002|p = 68}} The sultanate was to control much of North India and to make many forays into South India. Although at first disruptive for the Indian elites, the sultanate largely left its vast non-Muslim subject population to its own laws and customs.{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|p = 47}}{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 6}} By repeatedly repulsing ] in the 13th century, the sultanate saved India from the devastation visited on West and Central Asia, setting the scene for centuries of ] of fleeing soldiers, learned men, mystics, traders, artists, and artisans from that region into the subcontinent, thereby creating a syncretic Indo-Islamic culture in the north.{{sfn|Ludden|2002|p = 67}}{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|pp = 50–51}} The sultanate's raiding and weakening of the regional kingdoms of South India paved the way for the indigenous ].{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|p = 53}} | |||

| === Early modern era === | |||

| In the early 16th century, northern India, then under mainly Muslim rulers,{{sfn|Robb|2001|p = 80}} fell again to the superior mobility and firepower of a new generation of Central Asian warriors.{{sfn|Stein|1998|p = 164}} A Turco-Mongol emir, ] "Babur", after defeating the Delhi Sultanate, upgraded himself from ] and proclaimed himself as the ]. His successors were called ] or Moguls by European historians owing to the dynasty's Mongol origins. They did not stamp out the local societies it came to rule. Instead, it balanced and pacified them through new administrative practices{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|p = 115}}{{sfn|Robb|2001|pp = 90–91}} and diverse and inclusive ruling elites,{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 17}} leading to more systematic, centralised, and uniform rule.{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|p = 152}} Eschewing tribal bonds and Islamic identity, especially under ], the Mughals united their far-flung realms through loyalty, expressed through a Persianised culture, to an emperor who had near-divine status.{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 17}} The State's economic policies, deriving most revenues from agriculture{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|p = 158}} and mandating that taxes be paid in the well-regulated silver currency,{{sfn|Stein|1998|p = 169}} caused peasants and artisans to enter larger markets.{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|p = 152}} The relative peace maintained by the empire during much of the 17th century was a factor in India's economic expansion,{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|p = 152}} resulting in greater patronage of ], literary forms, textiles, and ].{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|p = 186}} Newly coherent social groups in northern and western India, such as the ], the ]s, and the ], gained military and governing ambitions during Mughal rule, which, through collaboration or adversity, gave them both recognition and military experience.{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|pp = 23–24}} Expanding commerce during Mughal rule gave rise to new Indian commercial and political elites along the coasts of southern and eastern India.{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|pp = 23–24}} As the empire disintegrated, many among these elites were able to seek and control their own affairs.{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|p = 256}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | perrow = 2/1 | |||

| | total_width = 360 | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | image_style = border:none; | |||

| | image1 = Agra Fort DistantTaj.JPG | |||

| | caption1 = A distant view of the ] from the ] | |||

| | image2 = India 1835 2 Mohurs.jpg | |||

| | caption2 = A two ] Company gold coin, issued in 1835, the ] inscribed "], King" | |||

| }} | |||

| By the early 18th century, with the lines between commercial and political dominance being increasingly blurred, a number of European trading companies, including the English ], had established coastal outposts.{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|p = 286}}{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|pp = 44–49}} The East India Company's control of the seas, greater resources, and more advanced military training and technology led it to increasingly assert its military strength and caused it to become attractive to a portion of the Indian elite; these factors were crucial in allowing the company to gain powerful influence over the ] in 1757 and sideline the other European companies.{{sfn|Robb|2001|pp = 98–100}}{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|p = 286}}{{sfn|Ludden|2002|pp = 128–132}}{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|pp = 51–55}} Its further access to the riches of Bengal and the subsequent increased strength and size of its army enabled it to annex or subdue most of India by the 1820s.{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|pp = 68–71}} India was then no longer exporting manufactured goods as it long had, but was instead supplying ] with raw materials. By this time, with its economic power severely curtailed by the ] and having effectively been made an arm of British administration, the East India Company began more consciously to enter non-economic arenas, including education, social reform, and culture.{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2008|p = 289}} | |||

| In 1833, the three presidencies of ], ] and ] were unified into a unitary state, headed by the ] and the creation of the ]. | |||

| === Modern India === | |||

| ⚫ | {{Main|History of the Republic of India}} | ||

| Historians consider India's modern age to have begun sometime between 1848 and 1885. The appointment in 1848 of ] as ] set the stage for changes essential to a modern state. These included the consolidation and demarcation of sovereignty, the surveillance of the population, and the education of citizens. Technological changes—among them, railways, canals, and the telegraph—were introduced not long after their introduction in ].{{sfn|Robb|2001|pp = 151–152}}{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|pp = 94–99}}{{sfn|Brown|1994|p = 83}}{{sfn|Peers|2006|p = 50}} However, disaffection with the company also grew during this time and set off the ]. Fed by diverse resentments and perceptions, including invasive British-style social reforms, harsh land taxes, and summary treatment of some rich landowners and princes, the rebellion rocked many regions of northern and central India and shook the foundations of Company rule.{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|pp = 100–103}}{{sfn|Brown|1994|pp = 85–86}} Although the rebellion was suppressed by 1858, it led to the dissolution of the East India Company and the ] by the ]. Proclaiming a ] and a gradual but limited British-style parliamentary system, the new rulers also protected princes and landed gentry as a feudal safeguard against future unrest.{{sfn|Stein|1998|p = 239}}{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|pp = 103–108}} In 1861, a supreme legislature for India was estabilished — the ]. Further reforms also created a unified bank — the ], a police force — the ] and a unified army — the ]. In 1876, the Crown-ruled India and the numerous Indian states under the Crown's suzerainty formed a loose political union called the ], and ] was crowned the ] in 1877. In the decades following, public life gradually emerged all over India, leading eventually to the founding of the ] in 1885.{{sfn|Robb|2001|p = 183}}{{sfn|Sarkar|1983|pp = 1–4}}{{sfn|Copland|2001|pp = ix–x}}{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 123}} | |||

| The rush of technology and the commercialisation of agriculture in the second half of the 19th century was marked by economic setbacks, and many small farmers became dependent on the whims of far-away markets.{{sfn|Stein|1998|p = 260}} There was an increase in the number of large-scale ],{{sfn|Stein|2010|p=245|ps=: An expansion of state functions in British and in princely India occurred as a result of the terrible famines of the later nineteenth century, ... A reluctant regime decided that state resources had to be deployed and that anti-famine measures were best managed through technical experts.}} and, despite the risks of infrastructure development borne by Indian taxpayers, little industrial employment was generated for Indians.{{sfn|Stein|1998|p = 258}} There were also salutary effects: commercial cropping, especially in the newly canalled Punjab, led to increased food production for internal consumption.{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 126}} The railway network provided critical famine relief,{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 97}} notably reduced the cost of moving goods,{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 97}} and helped nascent Indian-owned industry.{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 126}} | |||

| {{multiple image|perrow=2|total_width=360 | |||

| |image_style = border:none; | |||

| |align = left | |||

| | image1 = British Indian Empire 1909 Imperial Gazetteer of India.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = Political Divisions of the Indian Empire in 1909 | |||

| |image2=Nehru gandhi.jpg | |||

| |caption2=] sharing a light moment with ], Mumbai, 6 July 1946 | |||

| }} | |||

| After World War I, in which approximately ] in the ],{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 163}} a new period began. It was marked by the enactment of the ] as the Government of India Act 1919 but also ], by more strident Indian calls for self-rule, and by the beginnings of a ] movement of non-co-operation, of which ] would become the leader and enduring symbol.{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 167}} During the 1930s, slow legislative reform was enacted; the Indian National Congress won victories in the resulting elections.{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|pp = 195–197}} The next decade was beset with crises: ], the Congress's final push for non-co-operation, and an upsurge of ]. All were capped by the advent of independence in 1947, but tempered by the ] into two states: India and Pakistan.{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 203}} | |||

| Vital to India's self-image as an independent nation was its constitution, completed in 1950, which put in place a secular and democratic republic.{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 231}} Per the ], India retained its membership of the ], becoming the first republic within it.<ref>{{Cite web |title=London Declaration, 1949 |url=https://thecommonwealth.org/london-declaration-1949 |access-date=11 October 2022 |website=Commonwealth |language=en}}</ref> Economic liberalisation, which ] and the collaboration with Soviet Union for technical know-how,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Role of Soviet Union in India's industrialisation: a comparative assessment with the West |url=http://ijrar.com/upload_issue/ijrar_issue_20544196.pdf |website=ijrar.com}}</ref> has created a large urban middle class, transformed India into ],<ref>{{Citation |title=Briefing Rooms: India |url=https://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/India/ |work=] |year=2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110520002800/https://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/India/ |url-status=dead |publisher=] |archive-date=20 May 2011}}</ref> and increased its geopolitical clout. Yet, India is also shaped by seemingly unyielding poverty, both rural and urban;{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006 |pp=265–266}} by ] and ];{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|pp = 266–270}} by ];{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 253}} and by ] and ].{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 274}} It has unresolved territorial disputes with ]{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|pp = 247–248}} and with ].{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|pp = 247–248}} India's sustained democratic freedoms are unique among the world's newer nations; however, in spite of its recent economic successes, freedom from want for its disadvantaged population remains a goal yet to be achieved.{{sfn|Metcalf|Metcalf|2006|p = 304}} | |||

| ==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

Revision as of 04:04, 11 December 2023

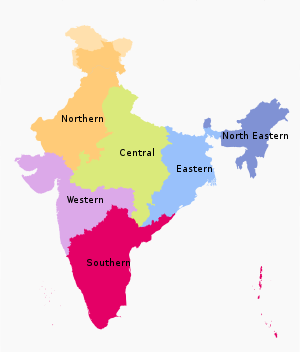

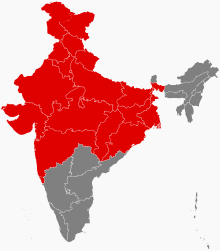

"Northwest India" redirects here. For the historical region, see Northwest India (pre-1947).Group of Northern Indian states Further information: Administrative divisions of India, Zonal Councils of India, and Cultural Zones of IndiaPlace in India

| North India Northern India / The North | |

|---|---|

From Top, left to right: Kinnaur Kailash, Victoria Memorial, India Gate, Golden Temple, Thar Desert, Indian elephants at the Jim Corbett National Park, Gateway of India, Taj Mahal. From Top, left to right: Kinnaur Kailash, Victoria Memorial, India Gate, Golden Temple, Thar Desert, Indian elephants at the Jim Corbett National Park, Gateway of India, Taj Mahal. | |

Extent of North India in its broader sense Extent of North India in its broader sense | |

| Country | |

| States |

Union Territories: |

| Most populous cities (2011) | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,389,300 km (922,500 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 912,030,836 |

| • Density | 380/km (990/sq mi) |

| Demonyms | North Indian See all demonyms |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+05:30) |

| Common languages | |

| Official languages | |

North India, also called Northern India or simply the North, in a broader geographic context, typically refers to the northern part of India or, historically, of the Indian subcontinent, occupying 72.6% of India's total land area and 75% of India's population, and where speakers of Indo-Aryan Languages form a prominent majority population. The region has a varied geography ranging from the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Himalayas, to the Thar Desert, the Central Highlands and the north-western part of the Deccan plateau. Multiple rivers flow through this region including the Ganges, the Yamuna, the Indus and the Narmada rivers. In a more specific and sometimes administrative sense, North India can also be used to denote a smaller region within this broader expanse, stretching from the Ganga-Yamuna Doab to the Thar Desert.

North India extends across the majority of India, covering the states of Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Punjab and Haryana, Rajasthan, UP, MP, Chhattisgarh, Goa, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Bihar, Jharkhand, and West Bengal. In its narrower sense, the term has different implications. The Ministry of Home Affairs in its Northern Zonal Council Administrative division included the states of Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab and Rajasthan and Union Territories of Chandigarh, Delhi, Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh. The Ministry of Culture in its North Culture Zone includes the state of Uttarakhand but excludes Delhi whereas the Geological Survey of India includes Uttar Pradesh and Delhi but excludes Rajasthan and Chandigarh.

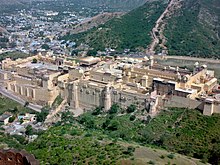

North India saw the development of the Indo-Aryan languages, and the North Indian culture and cuisine after the decline of the Indus valley civilization. The Aryan Migration Theory suggests that there was a slow migration of Indo-Iranian peoples through the northwest into this region between 2000 and 1500 BC, leading to the development of the Indo-Aryan languages from Proto-Indo-Iranian and some vocal synthesis with the Dravidian languages. North India was the historical centre of the ancient Vedic culture, the Mahajanapadas, the Magadha Empire, Mauryan Empire, Gupta Empire, Pala Empire, Gurjara-Pratihara Empire, the medieval Delhi Sultanate and the modern Mughal India and the Indian Empire, among many others. It has a diverse culture, and includes the Hindu pilgrimage centres of Char Dham, Haridwar, Varanasi, Ayodhya, Mathura, Prayagraj, Vaishno Devi and Pushkar, the Buddhist pilgrimage centres of Sarnath and Kushinagar, the Sikh Golden Temple as well as world heritage sites such as the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, Khajuraho temples, Hill Forts of Rajasthan, Jantar Mantar (Jaipur), Qutb Minar, Red Fort, Agra Fort, Fatehpur Sikri and the Taj Mahal. North India's culture developed as a result of interaction between these Hindu and Muslim religious traditions.

The Northern Zonal Council, which overlaps significantly with the region of North India, has the third-largest gross domestic product of all zonal councils in India. The languages that are official in one or more of the states and union territories located in North India are English, Hindi, Urdu, Dogri, Punjabi, Bengali, Kashmiri, Maithili, Marathi, Konkani and Odia.

Definitions

Different authorities and sources define North India differently.

Government of India definitions

The Northern Zonal Council is one of the advisory councils, created in 1956 by the States Reorganisation Act to foster interstate co-operation under the Ministry of Home Affairs, which included the states of Chandigarh, Delhi, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh, Punjab and Rajasthan.

The Ministry of Culture established the North Culture Zone in Patiala, Punjab on 23 March 1985. It differs from the North Zonal Council in its inclusion of Uttarakhand and the omission of Delhi.

In contrast, the Geological Survey of India (part of the Ministry of Mines) included Uttar Pradesh and Delhi in its Northern Region, but excluded Rajasthan and Chandigarh, with a regional headquarters in Lucknow.

Wider definition

Indian press definition

The Hindu newspaper puts Bihar, Delhi and Uttar Pradesh related articles on its North pages. Articles in the Indian press have included the states of Bihar, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, and West Bengal in North India as well.

Latitude-based definition

The Tropic of Cancer, which divides the temperate zone from the tropical zone in the Northern Hemisphere, runs through India, and could theoretically be regarded as a geographical dividing line in the country. Indian states that are entirely above the Tropic of Cancer are Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar and most of North East Indian states. However that definition would also include major parts of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand and West Bengal and minor regions of Chhattisgarh and Gujarat.

Anecdotal usage

In Mumbai, the term "North Indian" is sometimes used to describe migrants from eastern Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, often using the term bhaiya (which literally means 'elder brother') along with it in a derogatory sense, however these very people are not considered North Indian by the inhabitants of Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Haryana and Rajasthan. In Punjab, they are often referred to as Purabias, meaning Easterners. The Government of Bihar official site places the state in the eastern part of India. Within Uttar Pradesh itself, "the cultural divide between the east and the west is considerable, with the purabiyas (easterners) often being clubbed with Biharis in the perception of the westerners."

History

Ancient Era

By 55,000 years ago, the first modern humans, or Homo sapiens, had arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa, where they had earlier evolved. The earliest known modern human remains in South Asia date to about 30,000 years ago. After 6500 BC, evidence for domestication of food crops and animals, construction of permanent structures, and storage of agricultural surplus appeared in Mehrgarh and other sites in Balochistan, Pakistan. These gradually developed into the Indus Valley Civilisation, the first urban culture in South Asia, which flourished during 2500–1900 BC north-western Indian subcontinent. Centred around cities such as Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, Dholavira, and Kalibangan, and relying on varied forms of subsistence, the civilisation engaged robustly in crafts production and wide-ranging trade.

Vedic Era

Between 2000 BC and 1500 BC, several waves of Indo-Aryan migrations from Central Asia occurred and these migrants settled in the Indo-Gangetic Plain. The Vedas, the oldest scriptures associated with Hinduism, were composed during this period, and historians have analysed these to posit a Vedic culture in the Punjab region and the upper Gangetic Plain. During the period 2000–500 BCE, many regions of the subcontinent transitioned from the Chalcolithic cultures to the Iron Age ones. The caste system, which created a hierarchy of priests (Brahmins), warriors Kshatriyas, and commoners and peasants (Vaishyas and Shudras), and but which excluded indigenous peoples by labelling their occupations impure, arose during this period (later referred to as Dalits or outcasts). On the Deccan Plateau, archaeological evidence from this period suggests the existence of a chiefdom stage of political organisation.

In the late Vedic period, around the 6th century BCE, the small states and chiefdoms of the Ganges Plain and the north-western regions had consolidated into 16 major oligarchies and monarchies that were known as the mahajanapadas. The emerging urbanisation gave rise to non-Vedic religious movements, two of which became independent religions. Jainism came into prominence during the life of its exemplar, Mahavira. Buddhism, based on the teachings of Gautama Buddha, attracted followers from all social classes excepting the middle class; chronicling the life of the Buddha was central to the beginnings of recorded history in India. In an age of increasing urban wealth, both religions held up renunciation as an ideal, and both established long-lasting monastic traditions. Politically, by the 3rd century BCE, the Kingdom of Magadha had annexed or reduced other states and evolved into the Magadha Empire under the House of Maurya. The Magadhan Mauryan emperors are known as much for their empire-building and determined management of public life as for Ashoka's renunciation of militarism and far-flung advocacy of the Buddhist dhamma.

In North India, by the 4th and 5th centuries, the House of Gupta of Magadha had created a complex system of administration and taxation in the greater Ganges Plain; this system became a model for later Indian kingdoms. Under the Guptas, a renewed Hinduism based on devotion, rather than the management of ritual, began to assert itself. This renewal was reflected in a flowering of sculpture and architecture, which found patrons among an urban elite. Classical Sanskrit literature flowered as well, and Indian science, astronomy, medicine, and mathematics made significant advances.

Medieval Era

Brihadeshwara temple, Thanjavur, completed in 1010 CE

Brihadeshwara temple, Thanjavur, completed in 1010 CE The Qutub Minar, 73 m (240 ft) tall, completed by the Sultan of Delhi, Iltutmish

The Qutub Minar, 73 m (240 ft) tall, completed by the Sultan of Delhi, Iltutmish

The Indian early medieval age, from 600 to 1200 AD, is defined by regional kingdoms and cultural diversity. When Harsha of Kannauj, who ruled much of the Indo-Gangetic Plain from 606 to 647 CE, attempted to expand southwards, he was defeated by the Chalukya ruler of the Deccan. When his successor attempted to expand eastwards, he was defeated by the Pala king of Bengal. No ruler of this period was able to create an empire and consistently control lands much beyond their core region. During this time, pastoral peoples, whose land had been cleared to make way for the growing agricultural economy, were accommodated within caste society, as were new non-traditional ruling classes. The caste system consequently began to show regional differences.

In the 6th and 7th centuries, the first devotional hymns were created in the Tamil language. They were imitated all over India and led to both the resurgence of Hinduism and the development of all modern languages of the subcontinent. Indian royalty, big and small, and the temples they patronised drew citizens in great numbers to the capital cities, which became economic hubs as well. Temple towns of various sizes began to appear everywhere as India underwent another urbanisation. By the 8th and 9th centuries, the effects were felt in South-East Asia, as South Indian culture and political systems were exported to lands that became part of modern-day Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Brunei, Cambodia, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Indian merchants, scholars, and sometimes armies were involved in this transmission; South-East Asians took the initiative as well, with many sojourning in Indian seminaries and translating Buddhist and Hindu texts into their languages.

After the 10th century, Muslim Central Asian nomadic clans, using swift-horse cavalry and raising vast armies united by ethnicity and religion, repeatedly overran South Asia's north-western plains. A general Qutub-ud-din Aibak declared his independence and established the Sultanate of Delhi in 1206. The sultanate was to control much of North India and to make many forays into South India. Although at first disruptive for the Indian elites, the sultanate largely left its vast non-Muslim subject population to its own laws and customs. By repeatedly repulsing Mongol raiders in the 13th century, the sultanate saved India from the devastation visited on West and Central Asia, setting the scene for centuries of migration of fleeing soldiers, learned men, mystics, traders, artists, and artisans from that region into the subcontinent, thereby creating a syncretic Indo-Islamic culture in the north. The sultanate's raiding and weakening of the regional kingdoms of South India paved the way for the indigenous Vijayanagara Empire.

Early modern era

In the early 16th century, northern India, then under mainly Muslim rulers, fell again to the superior mobility and firepower of a new generation of Central Asian warriors. A Turco-Mongol emir, Zahir-ud-din Mohammad "Babur", after defeating the Delhi Sultanate, upgraded himself from Emir and proclaimed himself as the Padishah of Hindustan. His successors were called Mughals or Moguls by European historians owing to the dynasty's Mongol origins. They did not stamp out the local societies it came to rule. Instead, it balanced and pacified them through new administrative practices and diverse and inclusive ruling elites, leading to more systematic, centralised, and uniform rule. Eschewing tribal bonds and Islamic identity, especially under Akbar, the Mughals united their far-flung realms through loyalty, expressed through a Persianised culture, to an emperor who had near-divine status. The State's economic policies, deriving most revenues from agriculture and mandating that taxes be paid in the well-regulated silver currency, caused peasants and artisans to enter larger markets. The relative peace maintained by the empire during much of the 17th century was a factor in India's economic expansion, resulting in greater patronage of painting, literary forms, textiles, and architecture. Newly coherent social groups in northern and western India, such as the Marathas, the Rajputs, and the Sikhs, gained military and governing ambitions during Mughal rule, which, through collaboration or adversity, gave them both recognition and military experience. Expanding commerce during Mughal rule gave rise to new Indian commercial and political elites along the coasts of southern and eastern India. As the empire disintegrated, many among these elites were able to seek and control their own affairs.

A distant view of the Taj Mahal from the Agra Fort

A distant view of the Taj Mahal from the Agra Fort A two mohur Company gold coin, issued in 1835, the obverse inscribed "William IV, King"

A two mohur Company gold coin, issued in 1835, the obverse inscribed "William IV, King"

By the early 18th century, with the lines between commercial and political dominance being increasingly blurred, a number of European trading companies, including the English East India Company, had established coastal outposts. The East India Company's control of the seas, greater resources, and more advanced military training and technology led it to increasingly assert its military strength and caused it to become attractive to a portion of the Indian elite; these factors were crucial in allowing the company to gain powerful influence over the Bengal province in 1757 and sideline the other European companies. Its further access to the riches of Bengal and the subsequent increased strength and size of its army enabled it to annex or subdue most of India by the 1820s. India was then no longer exporting manufactured goods as it long had, but was instead supplying Britain with raw materials. By this time, with its economic power severely curtailed by the British Parliament and having effectively been made an arm of British administration, the East India Company began more consciously to enter non-economic arenas, including education, social reform, and culture.

In 1833, the three presidencies of Bengal, Bombay and Madras were unified into a unitary state, headed by the Governor-General of India and the creation of the Government of India.

Modern India

Main article: History of the Republic of IndiaHistorians consider India's modern age to have begun sometime between 1848 and 1885. The appointment in 1848 of Lord Dalhousie as Governor General of India set the stage for changes essential to a modern state. These included the consolidation and demarcation of sovereignty, the surveillance of the population, and the education of citizens. Technological changes—among them, railways, canals, and the telegraph—were introduced not long after their introduction in Europe. However, disaffection with the company also grew during this time and set off the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Fed by diverse resentments and perceptions, including invasive British-style social reforms, harsh land taxes, and summary treatment of some rich landowners and princes, the rebellion rocked many regions of northern and central India and shook the foundations of Company rule. Although the rebellion was suppressed by 1858, it led to the dissolution of the East India Company and the direct administration of India by the British Crown. Proclaiming a unitary state and a gradual but limited British-style parliamentary system, the new rulers also protected princes and landed gentry as a feudal safeguard against future unrest. In 1861, a supreme legislature for India was estabilished — the Imperial Legislative Council of India. Further reforms also created a unified bank — the Imperial Bank of India, a police force — the Indian Imperial Police and a unified army — the Imperial Indian Army. In 1876, the Crown-ruled India and the numerous Indian states under the Crown's suzerainty formed a loose political union called the Indian Empire, and Queen Victoria of England was crowned the Empress of India in 1877. In the decades following, public life gradually emerged all over India, leading eventually to the founding of the Indian National Congress in 1885.

The rush of technology and the commercialisation of agriculture in the second half of the 19th century was marked by economic setbacks, and many small farmers became dependent on the whims of far-away markets. There was an increase in the number of large-scale famines, and, despite the risks of infrastructure development borne by Indian taxpayers, little industrial employment was generated for Indians. There were also salutary effects: commercial cropping, especially in the newly canalled Punjab, led to increased food production for internal consumption. The railway network provided critical famine relief, notably reduced the cost of moving goods, and helped nascent Indian-owned industry.

Political Divisions of the Indian Empire in 1909

Political Divisions of the Indian Empire in 1909 Jawaharlal Nehru sharing a light moment with Mahatma Gandhi, Mumbai, 6 July 1946

Jawaharlal Nehru sharing a light moment with Mahatma Gandhi, Mumbai, 6 July 1946

After World War I, in which approximately one million Indians served in the Indian Army, a new period began. It was marked by the enactment of the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms as the Government of India Act 1919 but also repressive legislation, by more strident Indian calls for self-rule, and by the beginnings of a nonviolent movement of non-co-operation, of which Mahatma Gandhi would become the leader and enduring symbol. During the 1930s, slow legislative reform was enacted; the Indian National Congress won victories in the resulting elections. The next decade was beset with crises: Indian participation in World War II, the Congress's final push for non-co-operation, and an upsurge of Muslim nationalism. All were capped by the advent of independence in 1947, but tempered by the partition of India into two states: India and Pakistan.

Vital to India's self-image as an independent nation was its constitution, completed in 1950, which put in place a secular and democratic republic. Per the London Declaration, India retained its membership of the Commonwealth, becoming the first republic within it. Economic liberalisation, which began in the 1980s and the collaboration with Soviet Union for technical know-how, has created a large urban middle class, transformed India into one of the world's fastest-growing economies, and increased its geopolitical clout. Yet, India is also shaped by seemingly unyielding poverty, both rural and urban; by religious and caste-related violence; by Maoist-inspired Naxalite insurgencies; and by separatism in Jammu and Kashmir and in Northeast India. It has unresolved territorial disputes with China and with Pakistan. India's sustained democratic freedoms are unique among the world's newer nations; however, in spite of its recent economic successes, freedom from want for its disadvantaged population remains a goal yet to be achieved.

Geography

North India lies mainly on continental India, north of peninsular India. Towards its north are the Himalayas which define the boundary between the Indian subcontinent and the Tibetan plateau. To its west is the Thar desert, shared between North India and Pakistan and the Aravalli Range, beyond which lies the state of Gujarat. The Vindhya mountains are, in some interpretations, taken to be the southern boundary of North India.

The predominant geographical features of North India are:

- the Indo-Gangetic plain, which spans the states and union territories of Chandigarh, Delhi, Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal and Jharkhand.

- the Himalayas and sub-Himalayan belt, which lie in the states of Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir and West Bengal;

- the Thar desert, which lies mainly in the state of Rajasthan.

The states of Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Jammu and Kashmir also have a large forest coverage.

General climate

North India lies mainly in the north temperate zone of the Earth. Though cool or cold winters, hot summers and moderate monsoons are the general pattern. North India is one of the most climatically diverse regions on Earth. During summer, the temperature often rises above 35 °C across much of the Indo-Gangetic plain, reaching as high as 50 °C in the Thar desert, Rajasthan and up to 49 in Delhi. During winter, the lowest temperature on the plains dips to below 5 °C, and below the freezing point in some states. Heavy to moderate snowfall occurs in Himachal Pradesh, Ladakh, J&K and Uttarakhand. Much of North India is notorious for heavy fog during winters.

Extreme temperatures among inhabited regions have ranged from −45 °C (−49 °F) in Dras, Ladakh to 50.6 °C (123 °F) in Alwar, Rajasthan. Dras is claimed to be the second-coldest inhabited place on the planet (after Siberia), with a recorded low of −60 °C.

Precipitation

The region receives heavy rain in plains and light snow on Himalayas precipitation through two primary weather patterns: the Indian Monsoon and the Western Disturbances. The Monsoon carries moisture northwards from the Indian Ocean, occurs in late summer and is important to the Kharif or autumn harvest. Western Disturbances, on the other hand, are an extratropical weather phenomenon that carry moisture eastwards from the Mediterranean Sea, the Caspian Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. They primarily occur during the winter season and are critically important for the Rabi or spring harvest, which includes the main staple over much of North India, wheat. The states of Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand receive some snowfall in winter months.

Traditional seasons

Northern Indian tradition recognises six distinct seasons in the region: summer (grishma or garmi(jyesth- ashadh), May–June), rainy (varsha (shravan-bhadra), July–August), cool (sharad (ashivan-kartik), September–October, sometimes thought of as 'early autumn'), autumn (hemant(margh-paush), November–December, also called patjhar, lit. leaf-fall), winter (shishir or sardi(magh-phagun),January–February) and spring (vasant(chaitra-baishakh), March–April). The literature, poetry and folklore of the region uses references to these six seasons quite extensively and has done so since ancient times when Sanskrit was prevalent. In the mountainous areas, sometimes the winter is further divided into "big winter" (e.g. Kashmiri chillai kalaan) and "little winter" (chillai khurd).

Demographics

The people of North India mostly belong to the Indo-Aryan ethno linguistic branch, and include various social groups such as Brahmins, Kayasthas, Rajputs, Banias, Jats, Rors, Gurjars, Kolis, Yadavs, Khatris and Kambojs. Other minority ethno-linguistic communities such as Dravidian, Tibeto-Burman and Austroasiatic exist throughout the region.

Religion

Hinduism is the dominant religion in North India. Other religions practiced by various ethnic communities include Islam, Sikhism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Baháʼí, Christianity, and Buddhism. Hindus constitutes more than 80 percent of the North India's population. National capital of India (New Delhi) is overwhelming Hindu-majority with Hindus constituting nearly 90% of the capital city's population. The states of Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh are overwhelmingly Hindu-majority. Uttar Pradesh is also majority Hindu, but it boasts a large Muslim minority as well. The union territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh have a slight Muslim plurality. The state of Punjab has a Sikh majority of 60% and is the homeland of Sikh religion.

Languages

Further information: Languages of India

Linguistically, North India is dominated by Indo-Aryan languages. It is in this region, or its proximity, that Sanskrit and the various Prakrits are thought to have evolved. The most widely spoken language in this region is Hindi. It has official status in the states of Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh as well as in the union territory of Delhi. Punjabi has predominance in the state of Punjab where it is the official language. It also has significant presence in the nearby regions. Urdu enjoys official status in Delhi, Jammu and Kashmir and Uttar Pradesh. Further north in Jammu and Kashmir, major languages are Dogri and Kashmiri. Languages like Bengali, Bhili and Nepali are also spoken in notable numbers throughout the region. A large part of North India is taken up by the so-called Hindi Belt, which here subsumes most of the Rajasthani languages, dialects of Western Hindi, Awadhi, Bhojpuri, Garhwali and Kumaoni.

Several Sino-Tibetan languages are spoken in the Himalayan region like Kinnauri, Ladakhi, Balti, and Lahuli–Spiti languages. Austro-Asiatic languages like Korwa/Kodaku is also spoken in some parts of this region.

Culture

The composite culture of North India is known as Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, a result of the amicable interaction of Hindus and Muslims there.

Dance

See also: List of Indian folk dancesDance of North India too has diverse folk and classical forms. Among the well-known folk dances are the bhangra of the Punjab, Ghoomar of Rajasthan, Nati of Himachal Pradesh and rouf and bhand pather of Kashmir. Main dance forms, many with narrative forms and mythological elements, have been accorded classical dance status by India's National Academy of Music, Dance, and Drama such as Kathak.

Clothing

Further information: Punjabi clothing, Jammu dress, and PhiranEach state of North India has its own regional forms of clothing:

- Uttar Pradesh: Chikan Suit, Pathani Salwar, Kurta Paijama, Sari .

- Jammu: Kurta/Dogri suthan and kurta/churidar pajama and kurta.

- Kashmir: Phiran and poots.

- Himachal Pradesh: Shalwar kameez, Kurta, Churidar, Dhoti, Himachali cap and angarkha.

- Punjab/Haryana: Salwar (Punjabi) Suit, Patiala salwar, Punjabi Tamba and Kurta, Sikh Dastar, Phulkari, Punjabi Ghagra

- Uttarakhand: Rangwali Phichora

Flora and fauna

North Indian vegetation is predominantly Tropical evergreen and Montane . Of the evergreen trees sal, teak, Mahogany, sheesham (Indian rosewood) and poplar are some which are important commercially. The Western Himalayan region abounds in chir, pine, deodar (Himalayan cedar), blue pine, spruce, various firs, birch and junipers. The birch, especially, has historical significance in Indian culture due to the extensive use of birch paper (Template:Lang-sa) as parchment for many ancient Indian texts. The Eastern Himalayan region consists of oaks, laurels, maples, rhododendrons, alder, birch and dwarf willows. Reflecting the diverse climatic zones and terrain contained in the region, the floral variety is extensive and ranges from Alpine to Cloud forests, coniferous to evergreen, and thick tropical rainforests to cool temperate woods.

There are around 500 varieties of mammals, 2000 species of birds, 30,000 types of insects and a wide variety of fish, amphibians and reptiles in the region. Animal species in North India include elephant, bengal tiger, indian leopard, snow leopard, sambar (Asiatic stag), chital (spotted deer), hangul (red deer), hog deer, chinkara (Indian gazelle), blackbuck, nilgai (blue bull antelope), porcupine, wild boar, Indian fox, Tibetan sand fox, rhesus monkey, langur, jungle cat, striped hyena, golden jackal, black bear, Himalayan brown bear, sloth bear, and the endangered caracal.

Reptiles are represented by a large number of snake and lizard species, as well as the ghariyal and crocodiles. Venomous snakes found in the region include king cobra and krait. Various scorpion, spider and insect species include the commercially useful honeybees, silkworms and lac insects. The strikingly coloured bir bahuti is also found in this region.

The region has a wide variety of birds, including peafowl, parrots, and thousands of immigrant birds, such as the Siberian crane. Other birds include pheasants, geese, ducks, mynahs, parakeets, pigeons, cranes (including the celebrated sarus crane), and hornbills. great pied hornbill, Pallas's fishing eagle, grey-headed fishing eagle, red-thighed falconet are found in the Himalayan areas. Other birds found here are tawny fish owl, scale-bellied woodpecker, red-breasted parakeet, Himalayan swiftlet, stork-billed kingfisher and Himalayan or white-tailed rubythroat.

Wildlife parks and reserves

Important national parks and tiger reserves of North India include:

Corbett National Park: It was established in 1936 as Hailey National Park along the banks of the Ramganga River. It is India's first National Park, and was designated a Project Tiger Reserve in 1973. Situated in Nainital district of Uttarakhand, the park acts as a protected area for the critically endangered Bengal tiger of India. Cradled in the foothills of the Himalayas, it comprises a total area of 500 km out of which 350 km is core reserve. This park is known not only for its rich and varied wildlife but also for its scenic beauty.

Nanda Devi National Park and Valley of Flowers National Park: Located in West Himalaya, in the state of Uttarakhand, these two national parks constitute a biosphere reserve that is in the UNESCO World Network of Biosphere Reserves since 2004. The Valley of Flowers is known for its meadows of endemic alpine flowers and the variety of flora, this richly diverse area is also home to rare and endangered animals.

Dachigam National Park: Dachigam is a higher altitude national reserve in the state of Jammu and Kashmir that ranges from 5,500 to 14,000 feet above sea level. It is home to the hangul (a red deer species, also called the Kashmir stag).

Great Himalayan National Park: This park is located in Himachal Pradesh and ranges in altitude from 5,000 to 17,500 feet. Wildlife resident here includes the snow leopard, the Himalayan brown bear and the musk deer.

Desert National Park: Located in Rajasthan, this national reserve features extensive sand dunes and dry salt lakes. Wildlife unique to the region includes the desert fox and the great Indian bustard.

Kanha National Park: The sal and bamboo forests, grassy meadows and ravines of Kanha were the setting for Rudyard Kipling's collection of stories, "The Jungle Book". The Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh came into being in 1955 and forms the core of the Kanha Tiger Reserve, created in 1974 under Project Tiger.

Vikramshila Gangetic Dolphin Sanctuary: Located in the state of Bihar, it is the only protected zone for the endangered Ganges and Indus river dolphin.

Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary: It is one of the finest bird parks in the world, it is a reserve that offers protection to faunal species as well. Nesting indigenous water birds as well as migratory water birds and waterside birds, this sanctuary is also inhabited by sambar, chital, nilgai and boar.

Dudhwa National Park: It covers an area of 500 km along the Indo-Nepal border in Lakhimpur Kheri District of Uttar Pradesh, is best known for the barasingha or swamp deer. The grasslands and woodlands of this park, consist mainly of sal forests. The barasingha is found in the southwest and southeast regions of the park. Among the big cats, tigers abound at Dudhwa. There are also a few leopards. The other animals found in large numbers, are the Indian rhinoceros, elephant, jungle cats, leopard cats, fishing cats, jackals, civets, sloth bears, sambar, otters, crocodiles and chital.

Ranthambhore National Park: It spans an area of 400 km with an estimated head count of thirty two tigers is perhaps India's finest example of Project Tiger, a conservation effort started by the government in an attempt to save the dwindling number of tigers in India. Situated near the small town of Sawai Madhopur it boasts of variety of plant and animal species of North India.

Kalesar National Park: Kalesar is a sal forest in the Shivalik Hills of eastern Haryana state. Primarily known for birds, it also contains a small number of tigers and panthers.

Places of interest

Nature

The Indian Himalayas, the Thar desert and the Indo-Gangetic plain dominate the natural scenery of North India. The region encompasses several of the most highly regarded hill destinations of India such as Srinagar, Shimla, Manali, Nainital, Mussoorie, Kausani and Mount Abu. Several spots in the states of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh provide panoramic views of the snow-clad Himalayan range. The Himalayan region also provides ample opportunity for adventure sports such as mountaineering, trekking, river rafting and skiing. Camel or jeep safaris of the Thar desert are also popular in the state of Rajasthan. North India includes several national parks such as the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, Jim Corbett National Park, Keoladeo National Park and Ranthambore National Park.

Pilgrimage

North India encompasses several of the holiest pilgrimage centres of Hinduism (Varanasi, Haridwar, Allahabad, Char Dham, Vaishno Devi, Rishikesh, Ayodhya, Mathura/Vrindavan, Pushkar, Prayag and seven of the twelve Jyotirlinga sites), the most sacred destinations of Buddhism (Bodh Gaya, Sarnath and Kushinagar), the most regarded pilgrimage centres of Sikhism (Amritsar and Hemkund) and some of the highly regarded destinations in Sufi Islam (Ajmer and Delhi). The largest Hindu temple, Akshardham Temple, the largest Buddhist temple in India, Mahabodhi, the largest mosque in India, Jama Masjid, and the largest Sikh shrine, Golden Temple, are all in this region.

Historical

North India includes some highly regarded historical, architectural and archaeological treasures of India. The Taj Mahal, an immense mausoleum of white marble in Agra, is one of the universally admired buildings of world heritage. Besides Agra, Fatehpur Sikri and Delhi also carry some great exhibits from the Mughal architecture. In Punjab, Patiala is known for being the city of royalty while Amritsar is a city known for its Sikh architecture and the Golden Temple. Lucknow has the famous Awadhi Nawab culture while Kanpur reflects excellent British architecture with monuments like All Souls Cathedral, King Edward Memorial, Police Quarters, Cawnpore Woollen Mills, Cutchery Cemetery etc. Khajuraho temples constitute another famous world heritage site. The state of Rajasthan is known for exquisite palaces and forts of the Rajput clans. Historical sites and architecture from the ancient and medieval Hindu and Buddhist periods of Indian history, such as Jageshwar, Deogarh and Sanchi, as well as sites from the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilisation, such as Manda and Alamgirpur, can be found scattered throughout northern India. Varanasi, on the banks of the River Ganga, is considered one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world and the second oldest in India after Nalanda. Bhimbetka is an archaeological site of the Paleolithic era, exhibiting the earliest traces of human life on the Indian subcontinent.

Universities

North India has several universities, including

- Agra University

- Alakh Prakash Goyal University

- All India Institute of Medical Sciences

- Allahabad University

- Aligarh Muslim University

- Ashoka University

- Avadh University

- Baba Farid University of Health Sciences

- Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University

- Bahra University

- Banaras Hindu University

- Bhagat Phool Singh Mahila Vishwavidyalaya

- Birla Institute of Technology and Science

- Central University of Punjab

- Central University of Rajasthan

- Chandigarh University

- CT University

- DAV University

- Deenbandhu Chhotu Ram University of Science and Technology

- Deen Dayal Upadhyay Gorakhpur University

- Delhi University

- Delhi Technological University

- Desh Bhagat University

- Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam Technical University

- Dr. B.R. Ambedkar National Law University

- Gautam Buddha University

- GNA University

- Govind Ballabh Pant University of Agriculture & Technology

- Gurukul Kangri University

- Guru Jambheshwar University of Science & Technology

- Guru Nanak Dev University

- Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University

- Haryana Agricultural University

- Himachal Pradesh University

- Himachal Pradesh National Law University

- Jai Narain Vyas University

- Jawaharlal Nehru University

- Jiwaji University

- Kanpur University

- Kumaon University

- Kurukshetra University

- Lovely Professional University

- Maharaja Ganga Singh University

- Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology

- National Law University, Sonipat

- O. P. Jindal Global University

- Panjab University

- Punjabi University

- Punjab Agricultural University

- Punjab Technical University

- South Asian University

- Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology

- SRM University, Haryana

- Sri Guru Granth Sahib World University

- Thapar University

- University of Jammu

- University of Kashmir

- University of Kota

- University of Lucknow

- University of Rajasthan

- Uttarakhand Technical University

- Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University

- World University of Design

The Indian Institute of Technology, National Institute of Technology and Indian Institute of Management have campuses in several cities of North India such as Delhi, Allahabad, Amritsar, Jammu, Kanpur, Jalandhar, Roorkee, Ropar, Rohtak, Varanasi, Lucknow and Kashipur and National Institute of Fashion Technology have campuses in several cities of North India such as Delhi, Kangra district, Raebareli and Srinagar. One of the first great universities in recorded history, the Nalanda University, is in the state of Bihar. There has been plans for revival of this ancient university, including an effort by a multinational consortium led by Singapore, China, India and Japan.

Economy

Further information: Economy of IndiaThe economy of North India is predominantly agrarian, but is changing fast with rapid economic growth that has ranged above 8% annually. Several parts of North India have prospered as a consequence of the Green Revolution, including Punjab, Haryana and Western Uttar Pradesh, and have experienced both economic and social development. The eastern areas of East Uttar Pradesh, however, have lagged and the resulting disparity has contributed to a demand for separate statehood in West Uttar Pradesh (the Harit Pradesh movement).

In 2004, the state with the highest GDP per capita in North India was Punjab followed by Haryana. Chandigarh has the highest per-capita State Domestic Product (SDP) of any Indian union territory. The National Capital Region of Delhi has emerged as an economic power house with rapid industrial growth along with adjoining areas of Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Rajasthan.

According to a 2009–10 report, a large number of unskilled and skilled workers have moved to southern India and other nations because of the unavailability of jobs locally. The technology boom that occurred in the past three decades in southern India has helped many Indians from the northern region to find jobs and live prosperous lives in southern cities. An analysis by Multidimensional Poverty Index creators reveals that acute poverty prevails in eight Indian states including the northern states of Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh.

Cuisine

Popular dishes

The best-known North-Indian food items are:

See also

- Northern South Asia

- India

- Northeast India

- East India

- South India

- Western India

- Central India

- Administrative divisions of India

Notes

References

- ^ "Genesis | ISCS". Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ "North Zone Cultural Centre". culturenorthindia.com. Ministry of Culture, Government of India. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Northern Region – Geological Survey of India". Geological Survey of India, MOI, Government of India. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ "The Hindu (NOIDA Edition)". Dropbox. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ "Marriages last the longest in north India, Maharashtra; least in northeast". The Times of India. 18 January 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "Can North India overtake 'arrogant' South in growth?". Firstpost. 30 April 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "North Indians in Coimbatore". The Hindu. 27 July 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "Hot spell continues in North". The Hindu. 22 May 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "Earthquake jolts North India". Bhaskar. 12 May 2015. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ The Hindu (26 January 2016). "-Intense cold in North eight die in Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal". The Hindu. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Ali, Amin (25 December 2019). "'Jharkhand is a North Indian state and for BJP to get decimated there is a statement in itself'". The Times of India Blog. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "The States Reorganisation Act, 1956 (Act No.37 of 1956)" (PDF). interstatecouncil.nic.in. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ Dhulipala, Venkat (2000). The Politics of Secularism: Medieval Indian Historiography and the Sufis. University of Wisconsin–Madison. p. 27.

The composite culture of northern India , known as the Ganga Jamuni tehzeeb was a product of the interaction between Hindu society and Islam.

- ^ "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 50th report (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- Ram Nath Dubey, "Economic Geography of India", Kitab Mahal, 1961. ... The Tropic of Cancer divides India roughly into two equal parts: the Warm Temperate and Tropical ...

- "A clash of cultures". NDTV. 25 February 2008. Archived from the original on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

... no one in North India, and here I am talking of the states of Punjab, Himachal, Uttarakhand, Haryana and Rajasthan, considers people from eastern UP and Bihar as North Indians!!!

- "Politicians to blame for low turnout". The Tribune, Chandigarh. 11 December 2001. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- "Government of Bihar". Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- "Unorganised Workers of Delhi and the Seven Day Strike of 1988". Indrani Mazumdar, Archives of Indian Labour. Archived from the original on 1 April 2004. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- Susheela Raghavan, "Handbook of Spices, Seasonings, and Flavorings", CRC Press, 2007, ISBN 0-8493-2842-X. ... Maharashtra, in North India, has kala masala in many versions ...

- Lowe, John J. (2017). Transitive Nouns and Adjectives: Evidence from Early Indo-Aryan. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-879357-1.

The term 'Epic Sanskrit' refers to the language of the two great Sanskrit epics, the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyaṇa. ... It is likely, therefore, that the epic-like elements found in Vedic sources and the two epics that we have are not directly related, but that both drew on the same source, an oral tradition of storytelling that existed before, throughout, and after the Vedic period.

- ^ Petraglia & Allchin 2007, p. 10 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPetragliaAllchin2007 (help), "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by modern humans originating in Africa. ... Coalescence dates for most non-European populations average to between 73–55 ka."

- Dyson 2018, p. 1 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDyson2018 (help), "Modern human beings—Homo sapiens—originated in Africa. Then, intermittently, sometime between 60,000 and 80,000 years ago, tiny groups of them began to enter the north-west of the Indian subcontinent. It seems likely that initially they came by way of the coast. ... it is virtually certain that there were Homo sapiens in the subcontinent 55,000 years ago, even though the earliest fossils that have been found of them date to only about 30,000 years before the present."

- Fisher 2018, p. 23 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFisher2018 (help), "Scholars estimate that the first successful expansion of the Homo sapiens range beyond Africa and across the Arabian Peninsula occurred from as early as 80,000 years ago to as late as 40,000 years ago, although there may have been prior unsuccessful emigrations. Some of their descendants extended the human range ever further in each generation, spreading into each habitable land they encountered. One human channel was along the warm and productive coastal lands of the Persian Gulf and northern Indian Ocean. Eventually, various bands entered India between 75,000 years ago and 35,000 years ago."

- ^ Coningham & Young 2015, pp. 104–105. sfn error: no target: CITEREFConinghamYoung2015 (help)

- Kulke & Rothermund 2004, pp. 21–23. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKulkeRothermund2004 (help)

- ^ Singh 2009, p. 181. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSingh2009 (help)

- Possehl 2003, p. 2. sfn error: no target: CITEREFPossehl2003 (help)

- Singh 2009, pp. 186–187. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSingh2009 (help)

- Witzel 2003, pp. 68–69. sfn error: no target: CITEREFWitzel2003 (help)

- ^ Singh 2009, p. 255. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSingh2009 (help)

- Kulke & Rothermund 2004, pp. 41–43. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKulkeRothermund2004 (help)

- Singh 2009, pp. 260–265. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSingh2009 (help)

- Kulke & Rothermund 2004, pp. 53–54. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKulkeRothermund2004 (help)

- Singh 2009, pp. 312–313. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSingh2009 (help)

- Kulke & Rothermund 2004, pp. 54–56. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKulkeRothermund2004 (help)

- Stein 1998, p. 21. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- Stein 1998, pp. 67–68. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- Singh 2009, p. 300. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSingh2009 (help)

- Singh 2009, p. 319. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSingh2009 (help)

- Singh 2009, p. 367. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSingh2009 (help)

- Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 63. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKulkeRothermund2004 (help)

- Kulke & Rothermund 2004, pp. 89–91. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKulkeRothermund2004 (help)

- ^ Singh 2009, p. 545. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSingh2009 (help)

- Stein 1998, pp. 98–99. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- ^ Stein 1998, p. 132. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- ^ Stein 1998, pp. 119–120. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- ^ Stein 1998, pp. 121–122. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- ^ Stein 1998, p. 123. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- ^ Stein 1998, p. 124. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- ^ Stein 1998, pp. 127–128. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- Ludden 2002, p. 68. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLudden2002 (help)

- Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 47. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAsherTalbot2008 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 6. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Ludden 2002, p. 67. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLudden2002 (help)

- Asher & Talbot 2008, pp. 50–51. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAsherTalbot2008 (help)

- Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 53. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAsherTalbot2008 (help)

- Robb 2001, p. 80. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRobb2001 (help)

- Stein 1998, p. 164. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 115. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAsherTalbot2008 (help)

- Robb 2001, pp. 90–91. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRobb2001 (help)

- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 17. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- ^ Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 152. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAsherTalbot2008 (help)

- Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 158. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAsherTalbot2008 (help)

- Stein 1998, p. 169. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 186. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAsherTalbot2008 (help)

- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 23–24. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 256. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAsherTalbot2008 (help)

- ^ Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 286. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAsherTalbot2008 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 44–49. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Robb 2001, pp. 98–100. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRobb2001 (help)

- Ludden 2002, pp. 128–132. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLudden2002 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 51–55. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 68–71. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 289. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAsherTalbot2008 (help)

- Robb 2001, pp. 151–152. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRobb2001 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 94–99. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Brown 1994, p. 83. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBrown1994 (help)

- Peers 2006, p. 50. sfn error: no target: CITEREFPeers2006 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 100–103. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Brown 1994, pp. 85–86. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBrown1994 (help)

- Stein 1998, p. 239. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 103–108. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Robb 2001, p. 183. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRobb2001 (help)

- Sarkar 1983, pp. 1–4. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSarkar1983 (help)

- Copland 2001, pp. ix–x. sfn error: no target: CITEREFCopland2001 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 123. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Stein 1998, p. 260. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- Stein 2010, p. 245: An expansion of state functions in British and in princely India occurred as a result of the terrible famines of the later nineteenth century, ... A reluctant regime decided that state resources had to be deployed and that anti-famine measures were best managed through technical experts. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein2010 (help)

- Stein 1998, p. 258. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStein1998 (help)

- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 126. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 97. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 163. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 167. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 195–197. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 203. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 231. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- "London Declaration, 1949". Commonwealth. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- "Role of Soviet Union in India's industrialisation: a comparative assessment with the West" (PDF). ijrar.com.

- "Briefing Rooms: India", Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, 2009, archived from the original on 20 May 2011

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 265–266. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 266–270. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 253. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 274. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 247–248. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 304. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMetcalfMetcalf2006 (help)

- "Forest Survey of India – State of Forest Report 2003". Ministry of Environment & Forests, Government of India. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- Peel, M. C. and Finlayson, B. L. and McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification". Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (direct: Final Revised Paper) - Yash Pal Singh (2006), Social Science Textbook for Class IX Geography, VK Publications, ISBN 978-81-89611-15-6,

... The Tropic of Cancer divides India into almost two equal parts. It makes the southern half of India in the Tropical Zone and the northern half in the Temperate zone ...

- "Dras, India Travel Weather Averages". Weatherbase.

- Sarina Singh, "India: Lonely Planet Guide", Lonely Planet, 2003, ISBN 1-74059-421-5.

- H. N. Kaul (1 January 1998), Rediscovery of Ladakh, Indus Publishing, 1998, ISBN 9788173870866,

... With its altitude of 10000 ft. above the sea, Dras is considered to be the second coldest inhabited place in the world after Siberia where mercury sinks as low as -40 °C during winter, though it has also recorded a low of −60 °C ...

- Galen A. Rowell, Ed Reading (June 1980), Many people come, looking, looking, Mountaineers, 1980, ISBN 9780916890865,

... the bleak village of Dras, reportedly the second coldest place in Asia with recorded temperatures of −80 °F (−62 °C) ...

- Vidya Sagar Katiyar, "Indian Monsoon and Its Frontiers", Inter-India Publications, 1990, ISBN 81-210-0245-1.

- Ajit Prasad Jain and Shiba Prasad Chatterjee, "Report of the Irrigation Commission, 1972", Ministry of Irrigation and Power, Government of India, 1972.

- "Western disturbances herald winter in Northern India". The Hindu Business Line. 17 November 2005. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- ^ Bin Wang, "The Asian Monsoon", Springer, 2006, ISBN 3-540-40610-7.

- R.K. Datta (Meteorological Office, Dum Dum) and M.G. Gupta (Meteorological Office, Delhi), "Synoptic study of the formation and movements of Western Depressions", Indian Journal of Meteorology & Geophysics, India Meteorological Department, 1968.

- A.P. Dimri, "Models to improve winter minimum surface temperature forecasts, Delhi, India", Meteorological Applications, 11, pp 129–139, Royal Meteorological Society, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Geography, Yash Pal Singh, pp. 420, FK Publications, ISBN 9788189611859, ... The sequence of the six traditional seasons is correct only for northern and central parts of India ...

- The Life of a Text: Performing the Rāmcaritmānas of Tulsidas, Philip Lutgendorf, pp. 22, University of California Press, 1991, ISBN 9780520066908, ... likening the major episodes of the narrative to various features of the river and its banks, and to the appearance of the river in each of the six seasons of the North Indian year ...