| Revision as of 15:41, 20 February 2024 editLohithf (talk | contribs)1 edit I added on to the smellTags: Reverted Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 23:52, 21 February 2024 edit undoWeirdNAnnoyed (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,457 edits Reverted 1 edit by Lohithf (talk): Reverting material added 20 Feb 2024: It is written in a non-encyclopedic style (possibly by an LLM) and is unsourcedTags: Twinkle UndoNext edit → | ||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

| ==Odour== | ==Odour== | ||

| ⚫ | Thioacetone has an intensely foul odour. Like many low molecular weight ], the smell is potent and can be detected even when highly diluted.<ref name="Derek Lowe">{{Cite web | url = https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/things-i-won-t-work-thioacetone | title = Things I Won't Work With: Thioacetone | author = Derek Lowe | author-link = Derek Lowe (chemist) | date = June 11, 2009 | work = In The Pipeline}}</ref> In 1889, an attempt to distill the chemical in the German city of ] was followed by cases of vomiting, nausea, and unconsciousness in an area with a radius of {{convert|0.75|km|mi}} around the laboratory due to the smell.<ref>{{cite journal| title = Ueber Thioderivate der Ketone |author1=E. Baumann |author2=E. Fromm |name-list-style=amp | year=1889|journal=Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft |volume=22 |issue=2 |pages=2592–2599 |doi=10.1002/cber.188902202151|url=https://zenodo.org/record/1425557 }}</ref> In an 1890 report, British chemists at the Whitehall Soap Works in ] noted that dilution seemed to make the smell worse and described the smell as "fearful".<ref>{{cite book|title=Chemical News and Journal of Industrial Science|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MSDOAAAAMAAJ&pg=RA3-PA6|year=1890|publisher=Chemical news office.|pages=219}}</ref> | ||

| == Thioacetone: From Infamous Stench to Unfolding Promise == | |||

| '''A Notorious Overture: The Great Freiberg Stink of 1889''' | |||

| Imagine cobblestone streets filled with panicked residents, handkerchiefs pressed tightly to their noses. This unsettling scene wasn't a scene from a gothic novel, but the chilling reality of the "Great Freiberg Stink" that engulfed the German town in 1889. The culprit? Thioacetone, a molecule accidentally synthesized by chemists Emil Fromm and Ernst Baumann, forever etching its pungent mark on olfactory history. | |||

| '''Beyond the Stench: Unraveling the Odor with a Molecular Waltz''' | |||

| Dismissing thioacetone as merely a stinky villain would be a gross understatement. The secret behind its infamous odor lies in a subtle molecular twist. Unlike its well-behaved cousin acetone with a C=O double bond, thioacetone boasts a C=S double bond. This seemingly minor switch, paired with lone pair electrons on the sulfur atom, creates a powerful dipole moment – the key player in this olfactory drama. | |||

| Think of odor molecules as tiny dancers waltzing with our olfactory receptors in the nose. The stronger the dipole moment, the more intense the waltz, resulting in distinct smells. In thioacetone's case, the powerful dipole leads to a vigorous jig, overwhelming our receptors and triggering the unpleasant sensation we know as its foul odor. | |||

| '''Demystifying the Dance: Unveiling the OR2T3 Receptor''' | |||

| But the story doesn't end there. Thanks to research by Perfetti et al. (2004), we know the specific receptor responsible for detecting this stinky jig: OR2T3. This opens doors to fascinating possibilities: | |||

| * '''Odor Counteroffensive:''' Could we design molecules that compete with thioacetone for the OR2T3 receptor, essentially masking its stench with a more "pleasant" waltz? Imagine neutralizing unpleasant industrial smells or creating personalized air fresheners! | |||

| * '''Super-Sleuth Sensors:''' Harnessing the specific interaction between thioacetone and OR2T3 could lead to incredibly sensitive sensors capable of detecting minute traces of the molecule, invaluable for environmental monitoring, industrial safety, or even food quality control. | |||

| '''From Scourge to Muse: Unveiling the Hidden Talents of Thioacetone''' | |||

| Ignoring the odor for a moment, thioacetone's unique structure holds the key to various potential applications: | |||

| * '''Polymer Powerhouse:''' Imagine incorporating thioacetone derivatives into polymers to boost their electrical conductivity, as demonstrated by Li et al. (2019) in Polymer Chemistry. This could lead to advancements in electronics and battery technology, paving the way for lighter, faster charging devices and more efficient energy storage! | |||

| * '''Chemical Chameleon:''' Thioacetone serves as a versatile starting material for numerous industrial chemicals and pharmaceuticals. Pandey et al. (2018) highlight its role in producing thiolated compounds used in lubricants, agrochemicals, and even life-saving drugs. Imagine developing more efficient lubricants, protecting crops from pests, or creating new medicines! | |||

| '''Sniffing Out the Future: Exploring Thioacetone's Untapped Potential''' | |||

| Thioacetone's journey is far from over. Future research, fueled by advancements in various fields, holds exciting possibilities: | |||

| * '''Tailoring the Beast:''' Overcoming its inherent instability and manipulating its structure could lead to entirely new materials with unique electrical, mechanical, or other desirable properties. Imagine materials that are lighter, stronger, or have self-healing abilities! | |||

| * '''Odor Ninja:''' Imagine targeting specific unpleasant odors by understanding the interaction between molecules like thioacetone and olfactory receptors. This could revolutionize air quality and personal comfort, creating personalized odor solutions that truly mask unwanted smells. | |||

| * '''The Ultimate Sniffer:''' Highly sensitive and specific odor detection with thioacetone-based sensors could have wide-ranging applications. Imagine ensuring food safety by detecting minute traces of spoilage, or monitoring environmental pollutants in real-time, safeguarding our planet and our health. | |||

| '''The Final Score: A Pungent Molecule with a Harmonious Future''' | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| In 1967, ] researchers repeated the experiment of cracking trithioacetone at a laboratory south of ], UK. They reported their experience as follows: | In 1967, ] researchers repeated the experiment of cracking trithioacetone at a laboratory south of ], UK. They reported their experience as follows: | ||

Revision as of 23:52, 21 February 2024

Chemical compound

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name Propane-2-thione | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name Thiopropan-2-one | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

| CAS Number | |||

| 3D model (JSmol) | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| PubChem CID | |||

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |||

InChI

| |||

SMILES

| |||

| Properties | |||

| Chemical formula | C3H6S | ||

| Molar mass | 74.14 g·mol | ||

| Appearance | Orange to brown liquid | ||

| Odor | Putrid and intensely foul | ||

| Melting point | −55°C(218.15k/-67°F) | ||

| Boiling point | 70°C(343.15k/158°F) | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

| Main hazards | Odor, skin irritant | ||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C , 100 kPa). Infobox references | |||

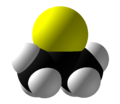

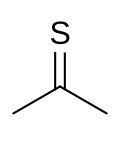

Thioacetone is an organosulfur compound belonging to the -thione group called thioketones with a chemical formula (CH3)2CS. It is an unstable orange or brown substance that can be isolated only at low temperatures. Above −20 °C (−4 °F), thioacetone readily converts to a polymer and a trimer, trithioacetone. It has an extremely potent, unpleasant odor, and is considered one of the worst-smelling chemicals known to humanity.

Thioacetone was first obtained in 1889 by Baumann and Fromm, as a minor impurity in their synthesis of trithioacetone.

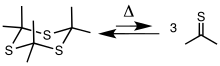

Preparation

Thioacetone is usually obtained by cracking the cyclic trimer trithioacetone, 3. The trimer is prepared by pyrolysis of allyl isopropyl sulfide or by treating acetone with hydrogen sulfide in the presence of a Lewis acid. The trimer cracks at 500–600 °C (932–1,112 °F) to give the thione.

Polymerization

Unlike its oxygen analogue acetone, which does not polymerise easily, thioacetone spontaneously polymerizes even at very low temperatures, pure or dissolved in ether or ethylene oxide, yielding a white solid that is a varying mixture of a linear polymer ···–

n–··· and the cyclic trimer trithioacetone. Infrared absorption of this product occurs mainly at 2950, 2900, 1440, 1150, 1360, and 1375 cm due to the geminal methyl pairs, and at 1085 and 643 cm due to the C–S bond. The 1H NMR spectra shows a single peak at x = 8.1.

The mean molecular weight of the polymer varies from 2000 to 14000 depending on the preparation method, temperature, and presence of the thioenol tautomer. The polymer melts in the range of about 70 °C to 125 °C. Polymerization is promoted by free radicals and light.

The cyclic trimer of thioacetone (trithioacetone) is a white or colorless compound with a melting point of 24 °C (75 °F), near room temperature. It also has a disagreeable odor.

Odour

Thioacetone has an intensely foul odour. Like many low molecular weight organosulfur compounds, the smell is potent and can be detected even when highly diluted. In 1889, an attempt to distill the chemical in the German city of Freiburg was followed by cases of vomiting, nausea, and unconsciousness in an area with a radius of 0.75 kilometres (0.47 mi) around the laboratory due to the smell. In an 1890 report, British chemists at the Whitehall Soap Works in Leeds noted that dilution seemed to make the smell worse and described the smell as "fearful". In 1967, Esso researchers repeated the experiment of cracking trithioacetone at a laboratory south of Oxford, UK. They reported their experience as follows:

Recently we found ourselves with an odour problem beyond our worst expectations. During early experiments, a stopper jumped from a bottle of residues, and, although replaced at once, resulted in an immediate complaint of nausea and sickness from colleagues working in a building two hundred yards [180 m] away. Two of our chemists who had done no more than investigate the cracking of minute amounts of trithioacetone found themselves the object of hostile stares in a restaurant and suffered the humiliation of having a waitress spray the area around them with a deodorant. The odours defied the expected effects of dilution since workers in the laboratory did not find the odours intolerable ... and genuinely denied responsibility since they were working in closed systems. To convince them otherwise, they were dispersed with other observers around the laboratory, at distances up to a quarter of a mile [0.40 km], and one drop of either acetone gem-dithiol or the mother liquors from crude trithioacetone crystallisations were placed on a watch glass in a fume cupboard. The odour was detected downwind in seconds.

Thioacetone is sometimes considered a dangerous chemical due to its extremely foul odor and its supposed ability to render people unconscious, induce vomiting, and be detected over long distances. As of 2023, at least two YouTube scientists (Nigel of "NileRed" and Zach of "LabCoatz") have published videos showing themselves smelling freshly-prepared thioacetone, both up-close and from a distance. In both cases, the individuals did not experience previously described side effects (nausea, vomiting, or unconsciousness). The cameraman filming NileRed’s video, however, was unable to tolerate the smell. LabCoatz later went on to test the selenium analog of thioacetone, as well as n-butyl isocyanide, and found both to smell far worse.

See also

- Thiobenzophenone, a thioketone that can be isolated as a solid

- Bromoacetone

- Chloroacetone

- Fluoroacetone

- Iodoacetone

References

- International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2014). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. The Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 739. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ William H. Sharkey (1979): "Polymerization through the carbon-sulfur double bond". Polymerization, series Advances in Polymer Science, volume 17, pages 73–103. doi:10.1007/3-540-07111-3_2

- ^ V.C.E. Burnop; K.G. Latham (1967). "Polythioacetone Polymer". Polymer. 8: 589–607. doi:10.1016/0032-3861(67)90069-9.

- ^ R.D. Lipscomb; W.H. Sharkey (1970). "Characterization and polymerization of thioacetone". Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 8 (8): 2187–2196. Bibcode:1970JPoSA...8.2187L. doi:10.1002/pol.1970.150080826.

- ^ Derek Lowe (June 11, 2009). "Things I Won't Work With: Thioacetone". In The Pipeline.

- Bailey, William J.; Chu, Hilda (1965). "Synthesis of polythioacetone". ACS Polymer Preprints. 6: 145–155.

- Bohme, Horst; Pfeifer, Hans; Schneider, Erich (1942). "Dimeric thioketones". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 75B (7): 900–909. doi:10.1002/cber.19420750722. Note: This early report mistakes the trimer for the monomer

- Kroto, H.W.; Landsberg, B.M.; Suffolk, R.J.; Vodden, A. (1974). "The photoelectron and microwave spectra of the unstable species thioacetaldehyde, CH3CHS, and thioacetone, (CH3)2CS". Chemical Physics Letters. 29 (2): 265–269. Bibcode:1974CPL....29..265K. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(74)85029-3. ISSN 0009-2614.

- E. Baumann & E. Fromm (1889). "Ueber Thioderivate der Ketone". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 22 (2): 2592–2599. doi:10.1002/cber.188902202151.

- Chemical News and Journal of Industrial Science. Chemical news office. 1890. p. 219.

- "Making the stinkiest chemical known to man". YouTube.

- "Making Thioacetone: The Worst Smelling Substance on Earth…and SMELLING IT | First-Ever Complete Demo". YouTube.

- "Smelling Isocyanides: The REAL Stinkiest Chemicals On Earth (WAY Worse Than Thioacetone)". YouTube.

External links

- Thioacetone, NIST

- Trithioacetone, Aldrich