| Revision as of 01:47, 15 April 2013 edit36.74.212.164 (talk) →Animals← Previous edit | Revision as of 02:26, 15 April 2013 edit undo36.74.212.164 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

| **The largest porpoise is the ] (''Phocoenoides dalli''), at up to 220 kg (490 lb) and 2.3 m (7.6 ft) in length.<ref name= Stewart/> | **The largest porpoise is the ] (''Phocoenoides dalli''), at up to 220 kg (490 lb) and 2.3 m (7.6 ft) in length.<ref name= Stewart/> | ||

| **The largest ] is the ] (''Berardius bairdii'') at up to 14 tonnes and 13 m (43 ft) long.<ref>. Harmlesslion.com</ref> | **The largest ] is the ] (''Berardius bairdii'') at up to 14 tonnes and 13 m (43 ft) long.<ref>. Harmlesslion.com</ref> | ||

| **The largest ] is are ] (''Delphinapterus leucas'') Adult male belugas can range from {{convert|3.5|to|5.5|m|ft|abbr=on}}, while the females measure {{convert|3|to|4.1|m|ft|abbr=on}}. | |||

| **The largest river dolphin are ] ''(Inia geoffrensis'') from Amazon basin {{convert|1.53|to|2.4|m|ft|abbr=on}}, depending on subspecies. Females are typically larger than males. The largest female Amazon river dolphins can range up to {{convert|2.5|m|ft|abbr=on}} | |||

| **The largest extinct whale is '']'' {{convert|18|m|ft}} in length.<ref name="bbc">{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/seamonsters/factfiles/basilosaurus.shtml|title=Sea Monsters - Fact File: Basilosaurus|date=c.2003|accessdate=2010-08-22|publisher=BBC - Science & Nature}}</ref> | |||

| ] is about as large as a ].]] | ] is about as large as a ].]] | ||

| *'''Bats''' (]) | *'''Bats''' (]) | ||

Revision as of 02:26, 15 April 2013

See also: Largest prehistoric animals| This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. Consider splitting content into sub-articles, condensing it, or adding subheadings. Please discuss this issue on the article's talk page. (December 2011) |

| It has been suggested that this article be split into multiple articles. (discuss) (December 2012) |

The largest organisms found on Earth can be determined according to various aspects of organism size, such as: mass, volume, area, length, height, or even genome size. Some organisms group together to form a superorganism, but such are not classed as single large organisms. The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest structure composed of living entities, stretching 2,000 km, but contains many organisms of many species. The organism sizes listed are frequently considered "outsized" and are not in the normal size range for the respective species.

Plants

Conifers (Pinopsida)

- The conifer division of plants include the tallest organism, and the largest single-stemmed plants by wood volume, wood mass, and main stem circumference. The largest by wood volume and mass is the giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum), native to Sierra Nevada and California; it grows to an average height of 70–85 m (230–280 ft) and 5–7 m (16–23 ft) in diameter. Specimens have been recorded up to 94.9 m (307 ft) in height and (not the same individual) 8.98 m (29 ft) in diameter; the largest individual still standing is the General Sherman tree, with a volume of 1,489 m (52,600 ft). The largest specimen on record was the Lindsey Creek tree, a coast redwood with a minimum trunk volume of over 2,500 m (88,000 cu ft) and a mass of over 3,300 tons. It fell over during a storm in 1905. Although not so large in volume, the closely related coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) of the Pacific coast in North America is taller, reaching a maximum height of 115.55 m (379.1 ft) – the Hyperion Tree, which ranks it as the world's tallest known living tree and organism (not including its roots under ground). The conifers also include the largest tree by circumference in the world, the Montezuma Cypress (Taxodium mucronatum). The thickest recorded tree, found in Mexico, is called Árbol del Tule, with a circumference of 57.9 m (190 ft) at its base and a diameter of 14.5 m (48 ft) at 1.5 m (5 ft) above ground level; its height is over 39.4 m (129 ft). These trees dwarf any other non-communal organism, as even the largest blue whales are likely to weigh one-sixteenth as much as a large giant sequoia or coast redwood. See record trees for other tree records.

Flowering plants (angiosperms)

- This is the most diverse and numerous division of plants, with upwards of 400,000 species.

- Clonal colonies

- For two dimensional area, the largest known clonal flowering plant, and indeed largest plant and organism, is a grove of male Aspen in Utah, nicknamed Pando (Populus tremuloides). The grove is connected by a single root system, and each stem above the ground is genetically identical. It is estimated to weigh approximately 6,000,000 kg, and covers 0.43 km² (106 acres).

- Another form of flowering plant that rivals Pando as the largest organism on earth in breadth, if not mass, is the giant marine plant, Posidonia oceanica, discovered in the Mediterranean near the Balearic Islands, Spain. Its length is about 8 km (5 mi). Although this plant has not been proven to be a single connected organism, all the samples do have the same DNA. It may also be the oldest living organism in the world, with an estimated age of 100,000 years.

- "Individual" plants

- By a stricter definition of individuality, and using contending measures of size, Ficus benghalensis, the giant banyan trees of India are the largest trees in the world. In these trees, a network of interconnected stems and branches has grown entirely by vegetative, "branching" propagation. One individual, Thimmamma Marrimanu, in Andhra Pradesh, covers 19,107 square metres, making it the largest single tree by two-dimensional canopy coverage area. This tree is also the world's largest known tree by a related measure, perimeter length, with a distance of 846 metres required to walk around the edge of the canopy. Thimmama Marrimanu is likely also the world's largest tree by three dimensional canopy volume.

- The tallest flowering plant is thought to be Eucalyptus regnans, which can reach heights of 99.6 m (327 ft).

- Other records among flowering plants include, the title of largest flower, which belongs to the species Rafflesia arnoldii. One of these flowers can reach a diameter of 1 m (3.3 ft) and weigh up to 11 kg (24 lb). The largest unbranched inflorescence, resembling (but not qualifying as) a giant flower, belongs to the titan arum (Amorphophallus titanum), reaching almost 3 m (10 ft) in height. The absolute largest inflorescence, at up to 8 m (26.5 ft) long, is borne by the talipot palm (Corypha umbraculifera) of India.

Cycads (Cycadophyta)

- The largest species of cycad is Hope's Cycad (Lepidozamia hopei), endemic to the Australian state of Queensland. The largest examples of this species have been over 15 m (49 ft) tall and have had a circumference of 1.5 m (4.9 ft).

Pteridophyta

- Horsetails (Equisetopsida)

- The largest of horsetail is the species Equisetum myriochaetum, of central Mexico. The biggest specimen known was 8 m (26.4 ft) tall and had a diameter of 2.5 cm (1 in).

- Ferns (Pteridopsida)

- The largest species of fern is probably Cyathea brownii of Norfolk Island, which may be 20 m (66 ft) or more in height.

Liverworts (Marchantiophyta)

- The largest species of liverwort is a New Zealand species, Schistochila appendiculata. The top size of this species is 1.1 m (3.6 ft) long, a diameter of 2.5 cm (1 in) and a stem length of 10 cm (4 in).

Mosses (Bryophyta)

- The world's tallest moss is Dawsonia superba, of New Zealand. This species can be 50 cm (20 in) tall.

Animals

A member of the order Cetacea, the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is believed to be the largest animal ever to have lived. The maximum recorded weight was 190 tonnes for a specimen measuring 30 m (98 ft), while longer ones, up to 33.4 m (110 ft), have been recorded but not weighed.

The African bush elephant (Loxodonta africana), of the order Proboscidea, is the largest living land animal. A native of various open habitats in sub-Saharan Africa, this elephant is born commonly weighing about 100 kg (220 lb). The largest elephant ever recorded was shot in Angola in 1974. It was a male measuring 10.7 m (35 ft) from trunk to tail and 4.2 m (13.7 ft) lying on its side in a projected line from the highest point of the shoulder to the base of the forefoot, indicating a standing shoulder height of 4.0 m (13 ft).

- Table of heaviest living animals

The following is a list of the heaviest living animals, which are all cetaceans. These whales also qualify as the largest living mammals. Since no scale can accommodate the body of a large whale, most whales have been weighed by parts.

| Rank | Animal | Average mass |

Maximum mass |

Average total length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Blue whale | 110 | 190 | 25.5 (84) |

| 2 | North Pacific right whale | 60 | 120 | 15.5 (51) |

| 3 | Southern right whale | 58 | 110 | 15.25 (50) |

| 4 | Fin whale | 57 | 120 | 19.5 (64.3) |

| 5 | North Atlantic right whale | 55 | 100 | 15 (49) |

| 6 | Bowhead whale | 54.5 | 120 | 15 (49) |

| 7 | Sperm whale | 31.25 | 57 | 13.25 (43.5) |

| 8 | Humpback whale | 29 | 48 | 13.5 (44) |

| 9 | Sei whale | 22.5 | 45 | 14.8 (49) |

| 10 | Gray whale | 19.5 | 45 | 13.5 (44) |

- Table of heaviest terrestrial animals

The following is a list of the heaviest wild land animals, which are all mammals. The African elephant is now listed as two species, the African bush elephant and the African forest elephant, as they are generally considered to be two separate species now.

| Rank | Animal | Average mass |

Maximum mass |

Average total length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | African bush elephant | 4.9 | 12.7 | 6 (18): Height* |

| 2 | Asian elephant | 4.15 | 8.0 | 6.8 (22) |

| 3 | African forest elephant | 2.8 | 6.0 | 6.2 (20) |

| 4 | White rhinoceros | 2.1 | 4.5 | 4.4 (14.5) |

| 5 | Indian rhinoceros | 1.9 | 4.0 | 4.2 (13.9) |

| 6 | Hippopotamus | 1.8 | 4.5 | 4 (13.2) |

| 7 | Javan rhinoceros | 1.715 | 2.3 | 3.8 (12.5) |

| 8 | Black rhinoceros | 1.1 | 2.9 | 4 (13.2) |

| 9 | Giraffe | 1.0 | 2 | 5.15 (16.9) |

| 10 | Gaur | 0.95 | 1.5 | 3.8 (12.5) |

Vertebrates

Mammals (Mammalia)

- Tenrecs and allies (Afrosoricida)

- The largest of these insectivorous mammals is the giant otter shrew (Potamogale velox), native to Central Africa. This species can weigh up to 1 kg (2.2 lb) and measure 0.64 m (2.1 ft) in total length.

- Even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla)

- The largest species in terms of weight is the hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius), native to the rivers of sub-Saharan Africa. This beast can reach a size of 4,500 kg (10,000 lb), 4.8 m (16 ft) long and 1.66 m (5.5 ft) tall. Prehistoric hippos such as H. gorgops and H. antiquus rivaled or exceeded the modern species as the largest members of the family and order to ever exist.

- The longest-bodied species, and tallest of all living land animals, is the Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), measuring up to 5.8 m (19.3 ft) tall to the top of the head, and despite being relatively slender, reaching a top weight of 2,000 kg (4,400 lb).

- The largest extant representative of the bovids, a diverse and well-known family, is the Asian forest-dwelling Gaur (Bos gaurus), in which bulls can weigh up to 1,500 kg (3,300 lb), 4.5 m (15 ft) in total length and stand 2.2 m (7.2 ft) at the shoulder. The extinct Giant Bison (Bison latifrons) may be the largest bovid in the fossil record, with an estimated shoulder up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft) and a weight over 2,000 kg (4,400 lb). Domestic cattle (Bos primigenius taurus) are usually smaller, although obese steers have been reported to weigh up to 2,140 kg (4,700 lb). the largest antelopes and gazelles is Giant Eland (Taurotragus derbianus) from Africa They are typically between 220 and 290 cm (7.2 and 9.5 ft) in head-and-body length and stand approximately 130 to 180 cm (4.3 to 5.9 ft) at the shoulder. Giant elands exhibit sexual dimorphism, as males are larger than females. The males weigh 400 to 1,000 kg (880 to 2,200 lb) and females weigh 300 to 600 kg (660 to 1,320 lb). The tail is long, having a dark tuft of hair, and averages 90 cm (35 in) in length. The life expectancy of giant elands is up to 25 years in the wild, and about 20 years in captivity.

- The largest species in the pig family is generally the giant forest hog (Hylochoerus meinertzhageni), a native of the African rainforests, at up to 275 kg (610 lb), 2.55 m (8.4 ft) in length and 1.1 m (3.6 ft) high at the shoulder. Although wild boars (Sus scrofa) have reportedly reached 320 kg (710 lb) historically, especially the Manchurian subspecies (Sus scrofa ussuricus) and obese domestic pigs (S. s. domesticus) which have been weighed at 1,157 kg (2,550 lb). The largest wild suid to ever exist was Kubanochoerus gigas, having measured up to 550 kg (1,200 lb) and stood more than 1.3 m (4.3 ft) tall at the shoulder.

- The largest living cervid is the moose (Alces alces), particularly the Alaskan subspecies, verified at up to 820 kg (1,800 lb), a total length of 3.5 m (11 ft) and a shoulder height of 2.4 m (7.9 ft). The extinct Irish Elk (Megaloceros giganteus) and the stag-moose (Cervalces scotti) were of similar or of slightly larger size than the Alaskan Moose. However, the Irish Elk could have antlers spanning up to 4.3 m (14 ft) across, about twice the maximum span for a Moose's antlers.

- The largest members of the camel family are either the bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus), which is still wild in the steppe of central Asia, or the similarly sized dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius), which no longer exists as a purely wild species but is widespread in the Middle East as a domestic animal, with a large introduced feral population in Australia. Both camels can weigh up to 1,000 kg (2,200 lb), 4 m (13 ft) in total length, 2.5 m (8.2 ft) tall at the shoulder and a height of 3.45 m (11.3 ft) at the hump. Several giant camels are known from fossils, the previous record holders, Gigantocamelus and Titanotylopus from North America, both possibly reached 2,485.6 kg (5,500 lb) and a shoulder height of over 3.4 m (11 ft). A newly discovered, unnamed fossil species commonly called the Syrian camel may have been even larger, at an estimated shoulder height of 3.6 or even 4 m (12–13 ft).

- Carnivorans (Carnivora)

- The largest carnivoran as well as the largest pinniped is the southern elephant seal (Mirounga leonina), attaining sizes up to 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) in weight and 6.9 m (22.5 ft) in length.

- The largest living land carnivore, on average, is the polar bear (Ursus maritimus), however, at maximum sizes it is matched by the Kodiak bear(Ursus arctos middendorffi), a brown bear subspecies. Both reaching shoulder heights over 1.6 m (5.2 ft) and total lengths as much as 3.1 m (10 ft). The heaviest wild polar and brown bear weights recorded were, respectively, 1,002 kg (2,209 lb) and 750 kg (1,653 lb). The Largest panda Giant Panda (Aliuropoda melanouca) of China The giant panda has a black-and-white coat. Adults measure around 1.2 to 1.8 m (4 to 6 ft) long, including a tail of about 13 cm (5.1 in), and 60 to 90 cm (2.0 to 3.0 ft) tall at the shoulder. Males can weigh up to 160 kg (350 lb). Females (generally 10–20% smaller than males) can weigh as little as 75 kg (165 lb), but can also weigh up to 125 kg (276 lb). Average adult weight is 100 to 115 kg (220 to 254 lb). The largest bear, and the largest known mammalian land carnivore of all time, was Arctotherium angustidens. The largest specimen yet found is estimated to weight up to 1,600 kg (3,500 lb) and stood up to 3.4 m (11 ft 2 in) tall on the hind-limbs.

- The largest living members of the Felidae family and the largest tiger subspecies are the Siberian tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) and the Bengal tiger (P. t. tigris) reaching up 3.5 m (11 ft) in total length and standing up to 1.21 m (4.0 ft) at the shoulder. with reports of males up to 384 kg (847 lb) and 389 kg (858 lb) respectively, males average around 230 kg (500 lb) and normally reach as much as 310 kg (675 lb). The largest members of the Felidae family were the extinct American lion (Panthera leo atrox), averaging 256 kg (564 lb) and the saber-toothed cat Smilodon populator of which the largest males might have exceeded 400 kg (882 lb), matched by captive ligers (hybrids between lions and tigers) which can grow up to non-obese weights over 410 kg (904 lb) is although wild cat (Felis silvestris). the largest specimens are although its weight is similar to the average housecat, as males of the species weigh an average of 5 kg (11 lb) and females 3.5 kg (7.7 lb), with strong seasonal weight fluctuations of up to 2.5 kg. The wildcat's thick fur, size and non-tapered tail are its distinguishing traits; it normally would not be mistaken for the domestic cat, although in practice, it is less clear whether the two are frequently correctly distinguished, as one study showed an error rate of 39%. Predominantly nocturnal, the wildcat is active in the daytime in the absence of human disturbance. Domestic cats are similar in size to the other members of the genus Felis, typically weighing between 4–5 kg (8.8–11.0 lb). However, some breeds, such as the Maine Coon, can occasionally exceed 11 kg (25 lb). Conversely, very small cats (less than 1.8 kg (4.0 lb)) have been reported

- The largest living member of Canidae is the gray wolf (Canis lupus). The largest specimens from the Mackenzie Valley Wolf (C. l. occidentalis) or the Eurasian Wolf (C. l. lupus) weigh up to 80–86 kg (180–190 lb) and measure up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft) in total length and 0.9 m (3.0 ft) tall at the shoulder. Eurasian wolves from the Russian area have even been reported to weigh as much as 90–96 kg (200–210 lb), though these figures require verification. Domestic dogs can occasionally grow heavier, up to 155.6 kg (343 lb). The largest known canid is an extinct member of subfamilly Borophaginae, Epicyon haydeni. The largest known specimen of this species weighed an estimated 170 kg (370 lb).

- The largest and most diverse family of carnivores, the mustelids, reaches their maximum size (by mass) in the sea otter (Enhydra lutris) of the North Pacific coasts, at up to 54 kg (120 lb), and (by length) the giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) of the Amazonian rainforests, at up to 2.4 m (7.9 ft) in total. The largest mustelid to ever exist was likely the odd cat-like Ekorus from Africa, about the size of a leopard and filling a similar ecological niche before big cats came to the continent. Another contender for largest of this family is the wolverine-like Megalictis, which according to older estimates could have reached the size af a black bear. Newer estimates, however, significantly downgrade its size, although, at a maximum weight more than twice that of a wolverine, it is larger than most (if not all) living mustelids.

- The largest species in the Herpestidae (mongoose) family is the African White-tailed Mongoose (Ichneumia albicauda), at up to 6 kg (13 lb) and 1.18 m (3.9 ft) long.

- The largest species in the viverrid family is the Asian binturong (Arctictis binturong), at up to 27 kg (60 lb) and 1.85 m (6.1 ft) long, about half of which is tail. The largest viverrid known to have existed is Viverra leakeyi, which was around the size of a wolf or small leopard at 41 kg (90 lb).

- The largest modern species in the hyena family is the Spotted Hyena (Crocuta crocuta) of sub-Saharan Africa, at up to a maximum weight of 86–90 kg (190–200 lb). Spotted hyenas can range up to 2.13 m (7.0 ft) in total length and 93 cm (37 in) tall at the shoulder. The largest fossil hyena is the lion-sized Pachycrocuta, estimated at 200 kg (440 lb).

- The largest living procyonid is the Common Raccoon (Procyon lotor) of North American, having a body length of 40 to 70 cm (16 to 28 in) and a body weight of 3.5 to 9 kg (8 to 20 lb). The extinct Chapalmalania of South America was the largest known member of this family, about 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) in body length.

- The largest skunk is generally concidered the striped skunk, which can weigh up to 6.35 kg (14 lb) and reaches lenghts of up to 70 cm (2.3 ft). The American hog-nosed skunk (Conepatus leuconotus) is longer reaching lengths of up to 82.5 cm (2.7 ft), but is less heavy, only up to 10 lb (4.5 kg).

- Whales (Cetacea)

- The largest whale and animal is the previously mentioned blue whale, a baleen whale (Mysticeti). Its closest competitors are also baleen whales, the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus), which can reach a size of 27 m (89 ft) in length and weight of 109 tonnes, and the bowhead (Balaena mysticetus) and North Pacific right whale (Eubalaena japonica), both measured up to 21.2 m (70 ft) and estimated at that length to weigh about 133 tonnes.

- The largest toothed whale (Odontoceti) is the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), bulls of which usually range up to 18.2 m (60 ft) long and a mass of 50 tonnes. Whaling records and skeletal remains have indicated that, in the past, sperm whales could have grown to 26 m (85 ft) long.

- The orca or killer whale (Orcinus orca) is the largest species of the oceanic dolphin family. The largest Orca ever recorded was a male off the coast of Japan, measuring 9.7 m (32 ft) long and weighed 10 tonnes.

- The largest porpoise is the Dall's Porpoise (Phocoenoides dalli), at up to 220 kg (490 lb) and 2.3 m (7.6 ft) in length.

- The largest beaked whale is the Baird's beaked whale (Berardius bairdii) at up to 14 tonnes and 13 m (43 ft) long.

- The largest beluga and narwhals is are Beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) Adult male belugas can range from 3.5 to 5.5 m (11 to 18 ft), while the females measure 3 to 4.1 m (9.8 to 13.5 ft).

- The largest river dolphin are Amazon river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis) from Amazon basin 1.53 to 2.4 m (5.0 to 7.9 ft), depending on subspecies. Females are typically larger than males. The largest female Amazon river dolphins can range up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft)

- The largest extinct whale is Basilosaurus 18 metres (59 ft) in length.

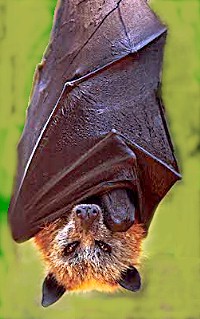

- Bats (Chiroptera)

- The largest bat species is the Giant golden-crowned flying fox (Acerodon jubatus), an endangered fruit bat from the rainforests of the Philippines that is part of the megabat family. The maximum size of this species is 1.5 kg (3.3 lb), 55 cm (22 in) a length, and a wingspan that may be almost 1.8 m (5.9 ft). The Large Flying Fox (Pteropus vampyrus) is smaller in body mass and length, but it has been known to exceed the Golden-crowned species in wingspan. Specimens have been verified to 1.83 m (6.0 ft) and possibly up to 2 m (6.6 ft) in wingspan.

- The neotropical Spectral Bat (Vampyrum spectrum), at up to 95 g (3.4 oz), 14 cm (5.5 in) long and about 0.9 m (3.0 ft) in wingspan, is believed to be the largest carnivorous bat, belonging to the microbat suborder.

- Armadillos (Cingulata)

- The extant giant of this group is the giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus), native to tropical South America. The top size for this species is 54 kg (120 lb), 0.55 m (1.8 ft) high at the shoulder and 1.6 m (5.2 ft) in length, although captive specimens can weigh up to 80 kg (176 lb).

- Much larger prehistoric examples are known, especially Glyptodon of the Americas, which probably averaged around 2 tonnes and could reach 4 m (13 ft) in total length and 1.53 m (5.0 ft) high at the top of the shelled back.

- Colugos (Dermoptera)

- Of the two colugo species in the order Dermoptera of gliding arboreal mammals in southeast Asia, the largest and most common is the Sunda Flying Lemur (Cynocephalus varigatus). The maximum size is 2 kg (4.4 lb) and 73 cm (29 in) in length.

- Hedgehogs and gymnures (Erinaceomorpha)

- The largest of this order and family of prickly-skinned, small mammals is the Greater Moonrat (Echinosorex gymnura), native to the rainforests of the Malaysian Peninsula as well as Sumatra and Borneo. The maximum size of this species is over 2 kg (4.4 lb) and 60 cm (24 in). The moonrat is a member of the same family as hedgehogs, which are typically much smaller than the Moonrat. Even larger was the giant gymnure Deinogalerix from Miocene Europe. It was estimated to grow larger then a house cat.

- Hyraxes (Hyracoidea)

- The largest species of hyrax seems to be the Cape Hyrax (Procavia capensis), at up to 5.4 kg (12 lb) and 73 cm (29 in) long. Prehistorically, the hyraxes were, for a time, the primary terrestrial herbivores in Africa, and some forms grew as large as horses.

- Rabbits, hares, and pikas (Lagomorpha)

- The largest extant wild species may be the European hare (Lepus europaeus), native to western and central Eurasia. This lagomorph can range up to 7 kg (15 lb) in weight and 0.85 m (2.8 ft) in total length. However, the Alaskan hare (Lepus othus) has almost the same exact body-proportions and weighs slightly more, averaging 4.8 kg (11 lb) and reaching a maximum mass of 7.2 kg (16 lb). Also, an occasional Arctic hare (L. arcticus) can also weigh as much as 7 kg (15 lb) but is typically smaller overall than the European and Alaskan species. The largest domestic rabbit breed is the Flemish Giant, which can attain a maximum known weight of 12.7 kg (28 lb). The largest lagomorph ever was Nuralagus rex, native to Minorca, which could have possibly grown up to 23 kg (51 lb).

- Elephant shrews (Macroscelidea)

- The elephant shrews are named for their combination of long, trunk-like snouts and long legs combined with a general shrew-like body form, but these animals are in fact not closely related to any other extant order (including tree shrews) and are a unique group behaviorly and in appearance. The largest species is the recently discovered Grey-faced Sengi (Rhynchocyon udzungwensis), known only from the Udzungwa Mountains of Tanzania and Kenya. This elephant shrew can range up to 0.75 kg (1.7 lb) and a length of 0.6 m (2.0 ft).

- Marsupials (Marsupialia)

- The opossums are is largest opossums Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana) from North America Virginia opossums can vary considerably in size, with larger specimens found to the north of the opossum's range and smaller specimens in the tropics. They measure 13–37 inches (35–94 cm) long from their snout to the base of the tail, with the tail adding another 8.5–19 inches (21.6–47 cm). Weight for males ranges from 1.7 to 14 pounds (0.8–6.4 kg) and for females from 11 ounces to 8.2 pounds (0.3–3.7 kg). They are one of the world's most variably sized mammals, since a large male from northern North America weighs about 20 times as much as a small

- The red kangaroo (Macropus rufus) of Australia is the largest living marsupial, and the largest member of the kangaroo family. These lanky mammals has been verified to 91 kg (200 lb) and 2.18 m (7.1 ft) when standing completely upright. Unconfirmed specimens have been reported up to 150 kg (330 lb). Prehistoric kangaroos reached even larger sizes. Procoptodon goliah was one of the largest known kangaroo that ever existed, standing approximately 2 m (6.6 ft) and weighing about 230 kg (510 lb). Some species from the genus Sthenurus were similar in size as well.

- The Northern hairy-nosed wombat (Lasiorhinus kreffti) is the largest vombatiform alive today with a head and body length up to 102 cm (40 inches) and a weight of up to 40 kg (88 lb). Prehistorically, this suborder contained many huge marsupials, including the largest to ever exist: Diprotodon. This rhino-sized herbivore would have reached more than 3.3 m (11 ft) in length and stood 1.83 m (6 ft) at shoulder and was estimated to weigh up to 3,000 kg (6,600 lb).

- The Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii), endemic to Tasmania, is the largest living marsupial carnivore. These stocky mammals can range up to 14 kg (31 lb) and 1.1 m (3.6 ft) in total length. The recently extinct thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), a close relative of the devil, grew larger and was the largest member of the group to survive into modern times. The largest measured specimen was 290 cm (9.5 ft) from nose to tail.

- The largest ever carnivorous marsupials to exist would have been the Australian marsupial lion (Thylacoleo) and the South American saber-toothed marsupial (Thylacosmilus) both ranging from 1.5 m (5.0 ft) to 1.8 m (6.0 ft) long and weighing between 100 and 160 kg (220–350 lbs). Interestingly, both were not closely related to the true marsupial carnivores of today. Rather, the marsupial lion was most closely related to the herbivorous koalas, while Thylacosmilus was a member of the order Sparassodonta, a group which may not have even been true marsupials.

- Monotreme mammals (Monotremata)

- The largest extant monotreme (egg-bearing mammal) is the western long-beaked echidna (Zaglossus bruijni) weighing up to 16.5 kg (36.4 lb) and measuring 1 m (3.3 ft) long. The largest monotreme ever was the extinct echidna species Zaglossus hacketti, known only from a few bones found in Western Australia. It was the size of a sheep, weighing probably up to 100 kg (220 lb).

- Odd-toed Ungulates (Perissodactyla)

- The largest extant species is the white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum). The largest size this species can attain is 4,500 kg (10,000 lb), 4.7 m (15 ft) in total length, and 2 m (6.6 ft) tall at the shoulder. It is slightly larger than the Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), which can range up to a weight of 4,000 kg (8,800 lb). The extinct Elasmotherium sibricum was the largest rhino to ever exist. It stood approximately 2 m (7 ft) tall at the shoulder, up to 5 m (17 ft) long (excluding horn), and weighed from 3,000 to 5,000 kg (6,600 to 11,000 lb).

- The largest extant wild equids are the Grevy's zebra (Equus grevyi), at up to 450 kg (990 lb), a shoulder height of 1.6 m (5.2 ft) and total length of 3.8 m (12 ft). Until it was domesticated into extinction the wild horse (E. ferus) was the largest equid. Domestic horses can reach a maximum weight of 1,524 kg (3,360 lb) and shoulder height of 2.2 m (7.2 ft), probably far greater than the sizes attained by the wild horse. The largest prehistoric horse was Equus giganteus of North America. It was estimated to grow around the same size as the aforementioned domestic horse.

- The largest of the tapirs is the Malayan tapir (Tapirus indicus), the only member of the family outside of South America. Maximum size is about 2.5 m (8 ft) in length, 1.8 m (3.5 ft) tall at the shoulder, and up to 540 kg (1,200 lb) in weight.

- The largest land mammal ever was Paraceratherium or Indricotherium (formerly known as the Baluchitherium), a member of this order. The largest known species (Paraceratherium orgosensis) is believed to have stood up to 5.5 m (18 ft) tall, measured over 9 m (30 ft) long and may have weighed up to 20 tonnes.

- Pangolins (Pholidota)

- The largest species of scaly anteater is the giant pangolin (Manis gigantea), at up to 1.7 m (5.8 ft) and at least 40 kg (88 lb).

- Anteaters and sloths (Pilosa)

- The largest species is easily the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla). A large adult can weigh as much as 65 kg (143 lb), be over 0.6 m (2.0 ft) tall at the shoulder and measure 2.4 m (8 ft) in overall length.

- The largest living sloths are the Linnaeus's (Choloepus didactylus) and Hoffmann's two-toed sloths (C. hoffmanni), which both can range up to 10 kg (22 lb) and 0.86 m (2.8 ft) long.

- The sloths attained much larger sizes prehistorically, the largest of which were Megatherium which, at an estimated average weight of 4.5 tonnes and standing height of 5.1 m (17 ft), was about the same size as the African bush elephant.

- Primates (Primates)

- The gorillas (Gorilla gorilla & G. beringei) are the most massive living primates. The largest race is the eastern lowland gorilla (G. b. graueri), with males average 140–200 kg (310–440 lb), 1 m (3.3 ft) tall at the shoulder while on all fours and 1.65–1.75 m (5.4–5.7 ft) tall when standing. The tallest wild gorilla (from the Mountain gorilla race, G. b. beringei) stood 1.94 m (6.6 ft) and the heaviest wild one massed 266 kg (590 lb), although heavier weights have been observed in captivity. The great ape Gigantopithecus, which lived in Asia between 1 million and 300,000 years ago, is the largest primate known to have existed. It was estimated to stand 3 m (10 ft) tall and to weigh up to 550 kg (1200 lb).

- The largest of the Old World monkeys is the Mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx) with large males being up to 50 kg (110 lb), 90 cm (3 ft) long and 50 cm (20 in) at the shoulders. The prehistoric baboon Dinopithecus grew even larger than modern Mandrills, weighing as much as a grown man.

- The largest New World monkey is the Southern Muriqui (Brachyteles arachnoides), up to 15 kg (33 lb) and 1.6 m (5.2 ft) in total length.

- The largest lemur is the Indri (Indri indri) which can weigh up to 12 kg (26 lb) and 90 cm (3 ft) in total length, though one fossil lemur, Archaeoindris, was gorilla-sized at 200 kg (440 lb).

- Humans can attain weights of up to 636 kg (1400 lb) as well as heights of up to 2.72 m (8.9 ft), however, these are cases of morbid obesity, tumor, gigantism or other medical malady, though even when not afflicted with gigantism, humans are the tallest living primates.

- Elephants, mammoths, and mastodons (Proboscidea)

- The African bush elephant, with an average weight of around 5 tonnes, is the largest extant member of the order Proboscidea. Extinct species did not generally dwarf it but some could grow somewhat larger, including the Steppe mammoth (M. trogontherii) of Asia and Elephas recki of Africa, each of these species possibly exceeding a shoulder height of 4.6 m (15 ft) and 12 tonnes in weight.

- Deinotherium giganteum rivaled those proboscideans in size, and was the largest member of its family (Deinotheriidae).

- Rodents (Rodentia)

- The largest living rodent is the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris), native to most of the tropical and temperate parts of South America east of the Andes, always near water. Full-grown capybaras can reach 1.5 m (4.9 ft) long and 0.9 m (3.0 ft) tall at the shoulder and a maximum weight of 105.4 kg (232 lb).

- The second largest living rodent is the North American beaver (Castor canadensis), which favors water perhaps even more than its larger cousin. Outsized male beaver specimens have been recorded up to 50 kg (110 lb), which is about twice the normal weight for a beaver, and 1.7 m (5.6 ft) in total length. The Eurasian beaver (C. fiber) is close to the same average size, but is known to top out around a mass of 31.7 kg (70 lb). The largest of this family is the extinct Giant Beaver of North America. It grew over 8 ft (2.4 m) in length and weighed roughly 60 to 100 kg (130 to 220 lb), also making it one of the largest rodents to ever exist.

- The largest species in the squirrel family is the hoary marmot (Marmota caligata) of the Pacific Northwest, at up to 13.5 kg (30 lb) and 0.8 m (2.6 ft) long.

- The largest porcupines is are Cape Porcupine (Hystrix africaeaustralis)of Central Africa 63 to 81 centimetres (25 to 32 inches) long from the head to the base of the tail, with the tail adding a further 11–20 centimetres (4.3–7.9 inches). They weigh from 10 to 24 kilograms (22 to 53 pounds), with exceptionally large specimens weighing up to 30 kg (66 lb); males and females are not significantly different in size.

- The largest Muroid is the Gambian Pouched Rat of Africa. It grows up to 1 m (3.3 ft) in total length and can weight up to 4 kg (9 lb).

- The largest known rodent ever is Josephoartigasia monesi, an extinct species known only from fossils found in Uruguay. It was approximately 3 m (10 ft) long and 1.5 m (4.9 ft) tall, and is estimated to have weighed 1.5–2.5 tonnes. Prior to the description of J. monesi, the largest known rodent species were from the genus Phoberomys, of which two species have been discovered. An almost complete skeleton of the slightly smaller Late Miocene species, Phoberomys pattersoni, was discovered in Venezuela in 2000; it was approximately 3 m (10 ft) long, with an additional 1.5 m (5 ft) tail, and probably weighed around 700 kg (1,540 lb).

- Tree shrews (Scandentia)

- The largest of the tree shrews seems to be the common treeshrew (Tupaia glis), at up to 187 g (6.6 oz) and 40 cm (17 in).

- Dugongs and manatees (Sirenia)

- The largest living species in the order Sirenia of dugongs and manatees is the West Indian Manatee (Trichechus manatus). The largest manatees are found in the Florida subspecies. The maximum recorded size of this species was 1,655 kg (3,650 lb) and a total length of 4.6 m (15 ft).

- The extinct Steller's Sea Cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) was the largest member to ever exist, growing up to at least 7.9 m (26 ft) long and weighing up to 11 tonnes. It was a member of the dugong family.

- Shrews and moles (Soricomorpha)

- The largest species of this order is the Hispaniolan Solenodon, males of which can weigh up to 1 kg (35.3 oz) and reach lengths of 32 cm (12.6 in).

- The largest species of shrew, typically among the smallest-bodied of mammals, is the Asian house shrew (Suncus murinus), weighing up to 100 g (3.5 oz) and reach lengths of up to 16 cm (6.3 in).

- The largest mole is the amphibious Russian desman (Desmana moschata), with a total length of up to 43 cm (1.4 ft) and an upper weight of 520 g (1.1 lb).

- Aardvark (Tubulidentata)

- The only species in this order is the unique Aardvark (Orycteropus afer) of sub-Saharan Africa. Aardvarks are typically up to 1.3 m (4.3 ft) in length with an average weight of up to 65 kg (140 lb) and a shoulder height up to 0.65 m (2.1 ft). However, individuals as large as 2.2 m (7.2 ft) and as heavy as 100 kg (220 lb) are recorded.

- Other mammals

- An ancient relative of ungulates, Andrewsarchus, may have been the largest carnivorous land mammal ever, despite almost all living species being herbivorous. Known only from a 0.83 m (2.7 ft) skull found in Mongolia, about twice the length of a brown bear skull, this great beast has been estimated to range as high in size as 2 m (6.6 ft) at the shoulder and 4.5 m (15 ft) in length. Weight estimates range anywhere from 454 to 1,816 kg (1,000 to 4,000 lb) based on the unknown proportion of the skull's size relative to the body size.

Stem-mammals (Synapsida)

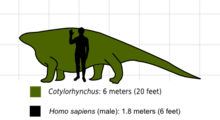

The Permian era Cotylorhynchus, from what is now the southern United States, probably was the largest of all synapsids (most of which went extinct 250 million years ago), at 6 m (20 ft) and 2 tonnes. The largest carnivorous synapsid was Anteosaurus from what is now South Africa during Middle Permian era. Anteosaurus was 5–6 m (16–20 ft) long, and weighed about 500–600 kg (1,100–1,300 lb).

- The largest pelycosaur was the pre-mentioned Cotylorhynchus, and the largest predatory pelycosaurus was Dimetrodon grandis from what is now North America, with a length of 3.1 m (10 ft) and weight of 250 kg (550 lb).

- Moschops was the largest therapsid, with a weight of 700 to 1,000 kg (1,500 to 2,200 lb), and a length of about 5 m (16 ft). The largest carnivorous therapsid was the aforementioned Anteosaurus.

Reptiles (Reptilia)

The largest living non-avian reptile, a representative of the order Crocodilia, is the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) of Southern Asia and Australia, with adult males being typically 3.9–5.5 m (13–18 ft) long. The largest confirmed saltwater crocodile on record was 6.3 m (20.7 ft) long, and weighed over 1,360 kg (3,000 lbs). Unconfirmed reports of much larger crocodiles exist, but examinations of incomplete remains have never suggested a length greater than 7 m (23 ft). Also, a living specimen estimated at 7 m (23 ft) and 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) has been accepted by the Guinness Book of World Records. A specimen caught alive in the Philippines in 2011 (now enclosed at a zoo) was found to have measured 6.2 m (20.3 ft) in length.

- Table of heaviest living reptiles

The following is a list of the heaviest living reptile species, which is dominated by the crocodilians. Unlike the upper weights of mammals, birds or fish, mass in reptiles is frequently poorly documented and many are subject to conjecture and estimation.

| Rank | Animal | Average mass |

Maximum mass |

Average total length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saltwater crocodile | 454 (1,000) | 2,000 (4,400) | 3.85 (12.6) |

| 2 | Nile crocodile | 382 (840) | 1,089 (2,400) | 3.7 (12) |

| 3 | Leatherback sea turtle | 364 (800) | 932 (2,050) | 2 (6.6) |

| 4 | Black caiman | 300 (660) | 1,310 (2,900) | 3.6 (12) |

| 5 | Orinoco crocodile | 290 (640) | 900 (2,000) | 3.6 (12) |

| 6 | American crocodile | 277 (610) | 1,000 (2,200) | 3.5 (11) |

| 7 | American alligator | 260 (570) | 1,000 (2,200) | 3.1 (10) |

| 8 | Aldabra giant tortoise | 205 (450) | 360 (790) | 1.4 (4.6) |

| 9 | Gharial | 200 (440) | 977 (2,150) | 3.8 (12) |

| 10 | Galapagos tortoise | 175 (390) | 400 (880) | 1.5 (4.9) |

- Crocodilians (Crocodylia)

- The previously discussed Saltwater Crocodile is the largest living member of this order, and of the crocodile family. The Nile crocodile, verified up to 6.45 m (21.2 ft) and a weight of 1,089 kg (2,400 lb), is the second largest crocodile, and very similar in size to the saltwater crocodile. The largest living specimen of a nile crocodile is purported to be a man-eater from Burundi named Gustave; he is believed to be more than 6.1 m (20 ft) long. The extinct Crocodylus thorbjarnarsoni was the largest true crocodile to exist, growing up to 7.5–8 m (25–27 ft) in length.

- The slender-snouted gharial, which has been measured up to 7 m (23 ft), is the largest member of its family and one of the largest crocodilians. Despite its length, specimens rarely exceed 450 kg (1000 lb) in weight. The largest member of this family to ever exist was the extinct Rhamphosuchus from Miocene Asia. It was one of the largest crocodilians to exist, attaining a length up to possibly 18 m (60 ft) long, though was more typically 11 m (36.3 ft). Based on its fossils, the latter species was less massive and heavy than the other giant crocodilians, weighing an estimated 3 tonnes.

- The largest member of the family Alligatoridae is either the Black Caiman or American Alligator which have been confirmed to grow up to 4.5 m (15 ft) in length and weigh up to 450 kg (1000 lb), not as large as the preceding crocodilians but still impressive. Unverified reports suggest lengths of up to 6 m (20 ft) for the black caiman and 5.8 m (19 ft) for the American alligator. The largest member of this family was the caiman-like Purussaurus, from northern South America during the Miocene era. It grew up to 12 m (40 ft) long and could weigh at least 8 tonnes, making it one of the largest crocodilians ever.

- Other contenders for the largest crocodilian ever include the late Cretaceous era Deinosuchus of what is now North America, at up to 12 m (40 ft) and 9 tonnes. Sarcosuchus imperator of the early Cretaceous was found in the Sahara desert and could also measure up to 12 m (40 ft) and weigh an estimated 13.6 tonnes.

- Lizards and snakes (Squamata)

- The most massive living member of this highly diverse reptilian order is the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus) of the neotropical riverways. The maximum verified size is 7.5 m (25 ft) and 250 kg (550 lb), although rumors of larger anacondas persist. The reticulated python (Python reticulatus) of Southeast Asia is longer but more slender, and has been reported to measure as much as 9.7 m (32 ft) in length and to weigh up to 158 kg (350 lb). The fossil of the largest snake ever, the extinct boa Titanoboa were found in coalmines in Colombia. This snake was estimated to reached a length of 12 to 15 m (40 to 50 ft), weighed about 1,135 kg (2,500 lb), and measured about 1 m (3 ft) in diameter at the thickest part of the body.

- Among the colubrids, the most diverse snake family, the longest specimens are reported in Chinese Ratsnake (Ptyas korros), at up to 4.75 m (15.6 ft).

- The longest venomous snake is the South Asian king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), with lengths (recorded in captivity) of up to 5.7 m (19 ft) and a weight of up to 12.7 kg (28 lb). It is also the largest elapid.

- The Gaboon viper, a very bulky species with a maximum length of around 2 m (6.6 ft),is typically the heaviest non-constrictor snake and the biggest member of the viper family, with unverified specimens reported to as much as 20 kg (44 lb). While not quite as heavy, another member of the viper family is longer still, the South American Bushmaster (Lachesis muta), with a maximum length of 3.65 m (12.0 ft).

- The largest of the monitor lizards (and the largest extent lizard in general) is the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis), endemic to the island of its name, at a maximum size of 3.13 m (10.2 ft) long and 166 kg (366 lb). The prehistoric Australian Megalania (Varanus priscus), which may have existed up to 40,000 years ago, is the largest terrestrial lizard known to exist, but the lack of a complete skeleton has resulted in a wide range of size estimates. Molnar's 2004 assessment resulted in an average weight of 320 kg (710 lb) and length of 4.5 m (15 ft), and a maximum of 1,940 kg (4,300 lb) at 7 m (23 ft) in length, which is toward the high end of the early estimates.

- The largest extent gecko is the Giant Gecko (Rhacodactylus leachianus) of New Caledonia, which can grow to 14 inches in length. It was surpassed in size by the extinct Kawekaweau (Hoplodactylus delcourti) of New Zealand, which grew to a length of 23 inches.

- By far the largest-ever members of this order were the giant mosasaurs (including Hainosaurus, Mosasaurus, and Tylosaurus), which grew to around 17 m (56 ft) and were projected to weigh up to 20 tonnes.

- Plesiosaurs (Plesiosauria); now extinct

- The largest known plesiosaur was Mauisaurus haasti, from the late Cretaceous oceans around what is now New Zealand. It is estimated to have grown to around 20 m (66 ft) in length and to have weighed 30 tonnes.

- Ichthyosaurs (Ichthyosauria); now extinct

- The largest of these marine reptiles (extinct for 90 million years) was the species Shastasaurus sikanniensis, at approximately 21 m (69 ft) long and 68 tonnes. This massive animal, from the Norian era in what is now British Columbia, is considered the largest marine reptile so far found in the fossil record.

- Tuataras (Sphenodontia)

- The larger of the two extant species of the New Zealand native tuataras is the Brothers Island tuatara (Sphenodon guntheri). The maximum size is 1.4 kg (3.1 lb) and 76 cm (30 in).

- Turtles (Testudines)

- The largest living turtle is the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), reaching a maximum total length of 3 m (10 ft) and a weight of 932 kg (2,050 lb).

- The largest extant freshwater turtle is possibly the North American alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii), which has an unverified maximum reported weight of 183 kg (400 lb), although this is challenged by several rare, giant softshell turtle from Asia (Rafetus and Pelochelys) unverified to 200 kg (440 lb) and nearly 2 m (6.6 ft) in total length.

- The Galápagos tortoise (Chelonoidis nigra) and the Aldabra giant tortoise (Aldabrachelys gigantea) are considered the largest truly terrestrial reptiles alive today. While the Aldabra tortoise averages larger at 205 kg (450 lb), the more variable-sized Galapagos tortoise can reach a greater maximum size of 400 kg (880 lb) and 1.85 m (6.1 ft) in total length. A much larger tortoise survived until about 2000 years ago, the Australasian Meiolania at about 2.6 m (8.5 ft) long and a weight of over 1 tonne. The tortoise Colossochelys atlas, of the Pleistocene era from what is now Pakistan and India, was even larger, at nearly 3.1 m (10 ft) and 2 tonnes.

- There are many extinct turtles that vie for the title of the largest ever. The largest seems to be the freshwater turtle Stupendemys, with an estimated total carapace length of more than 3.3 m (11 ft) and weight of up to 1,814–2,268 kg (4,000–5,000 lb). A close contender is Archelon ischyros, a sea turtle, which reached a length of 4.84 m (15.9 ft) across the flippers and a weight of over 2,200 kg (4,850 lb).

- Pterosaurs (Pterosauria); now extinct

- A dinosaur-era reptile (although not actually a dinosaur) is believed to have been the largest flying animal that ever existed: the pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus northropi, from North America during the late Cretaceous. This species is believed to have weighed up to 250 kg (550 lb), measured 7.9 m (26 ft) in total length (including a neck length of over 3 m (10 ft)) and measured up to 11 m (36 ft) across the wings. Another possible contender for the largest pterosaur is Hatzegopteryx, which is also estimated to have had an 11 m (36 ft) wingspan.

Dinosaurs (Dinosauria)

Main article: Dinosaur size- See also: Largest prehistoric animals

- Now extinct, except for theropod descendants, the Aves.

- Sauropods (Sauropoda)

- The largest dinosaurs, and the largest animals to ever live on land, were the plant-eating, long-necked Sauropoda. The tallest and heaviest sauropod known from a complete skeleton is an especimen of an immature Giraffatitan discovered in Tanzania between 1907 and 1912, now mounted in the Humboldt Museum of Berlin. It is 12 m (40 ft) tall and weighed 23–37 tonnes. The longest is a 25 m (82 ft) long specimen of Diplodocus discovered in Wyoming, and mounted in Pittsburgh's Carnegie Natural History Museum in 1907.

- There were larger sauropods, but they are known from only a few bones. The current record-holders had all been discovered before 1971, and include Argentinosaurus, which may have weighed 73 tonnes; Supersaurus which might have reached 35 m (112 ft) in length and Sauroposeidon which might have been 18 m (60 ft) tall. Two other such sauropods include Bruhathkayosaurus and Amphicoelias fragillimus. Both are known only from fragments. Bruhathkayosaurus was between 40–44 m (130–145 ft) in length and weighed 175–220 tons. A. fragillimus was approximately 58 m long and weighed 122.4 metric tons.

- Theropods (Theropoda)

- The largest theropod is arguably Spinosaurus of the mid-Cretaceous, the largest terrestrial predator known to exist (Although recent evidence suggests that spinosaurs spent a lot of time in the water filling a niche similar to modern day crocodiles and polar bears). Size estimates range from 12.6 to 18 m (41 to 59 ft) long and 7 to 21 tonnes for the largest individual found. The lack of agreement lies in the lack of a complete skeleton, the unknown proportion of the head to the body and the unknown function of the massive sail.

- The largest theropod known from a complete skeleton is the Tyrannosaurus specimen nicknamed "Sue", discovered in South Dakota in 1990 and now mounted in the Field Museum of Chicago. It was 12.3 m (40 ft) long, and weighted 6.8 to 9.1 tonnes depending of the methods used.

- Armored Dinosaurs (Thyreophora)

- The largest thyreophorans were Ankylosaurus and Stegosaurus, from the Late Cretaceous and Late Jurassic periods (respectively) of what is now North America, both measuring up to 9 m (30 ft) in length and estimated to weigh up to 6 tonnes.

- Ornithopods (Ornithopoda)

- The largest ornithopods, were the hadrosaurids Shantungosaurus, a late Cretaceous dinosaur found in the Shandong Peninsula of China, and Magnapaulia from the late Cretaceous of North America. Both species are known from fragmentary remains but are estimated to have reached over 15 m (50 ft) in length and were likely the heaviest non-sauropod dinosaurs, estimated at over 23 tonnes.

- Ceratopsians (Ceratopsia)

- The largest ceratopsians were Triceratops and its ancestor Eotriceratops from the late Cretaceous of North America. Both estimated to have reached about 9 m (30 ft) in length and weighed 12 tonnes.

Birds (Aves)

The largest living bird, a member of the Struthioniformes, is the ostrich (Struthio camelus), from the plains of Africa and Arabia. A large male ostrich can reach a height of 2.8 m (9.2 ft) and weigh over 156 kg (345 lb). A mass of 200 kg (440 lb) has been cited for the ostrich but no wild ostriches of this massive weight have been verified. Eggs laid by the Ostrich can weigh 1.4 kg (3 lb) and are the largest eggs in the world today.

The largest bird in the fossil record may be the extinct elephant birds (Aepyornis) of Madagascar, which were related to the ostrich. They exceeded 3 m (10 ft) in height and 500 kg (1,120 lb). The last of the elephant birds became extinct about 300 years ago. Of almost exactly the same upper proportions as the largest elephant birds was Dromornis stirtoni of Australia, part of a 26,000-year-old group called mihirungs of the family Dromornithidae. The largest carnivorous bird was Brontornis, an extinct flightless bird from South America which reached a weight of 350 to 400 kg (770 to 880 lb) and a height of about 2.8 m (9 ft 2 in). The tallest bird ever however was the Giant Moa (Dinornis maximus), part of the moa family of New Zealand that went extinct about 200 years ago. This moa stood up to 3.7 m (12 ft) tall, but weighed about half as much as a large elephant bird or mihirung due to its comparatively slender frame.

The largest bird ever capable of flight was Argentavis magnificens, a now extinct member of the Teratornithidae group found in Argentine fossil beds, with a wingspan up to 8.3 m (28 ft), a length of up to 3.5 m (11 ft), a height on the ground of up to 2 m (6.6 ft) and a body weight of at least 80 kg (176 lb).

- Table of heaviest living birds

The following is a list of the heaviest living bird species. These species are almost all flightless, which allows for these particular birds to have denser bones and heavier bodies. Flightless birds comprise less than 2% of all living bird species. One flying species, the corpulent Dalmatian pelican, ranks on the list.

| Rank | Animal | Average mass |

Maximum mass |

Average total length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ostrich | 104 (230) | 156.8 (346) | 210 (6.9) |

| 2 | Southern Cassowary | 45 (99) | 85 (190) | 155 (5.1) |

| 3 | Northern Cassowary | 44 (97) | 75 (170) | 149 (4.9) |

| 4 | Emu | 33 (73) | 70 (150) | 153 (5) |

| 5 | Emperor Penguin | 31.5 (69) | 46 (100) | 114 (3.7) |

| 6 | Greater Rhea | 23 (51) | 40 (88) | 134 (4.4) |

| 7 | Dwarf Cassowary | 19.7 (43) | 34 (75) | 105 (3.4) |

| 8 | Lesser Rhea | 19.6 (43) | 28.6 (63) | 96 (3.2) |

| 9 | King Penguin | 13.6 (30) | 20 (44) | 92 (3) |

| 10 | Dalmatian Pelican | 11.5 (25) | 15 (33) | 170 (5.6) |

- Birds of prey (Accipitriformes)

- The largest extant species is the Eurasian Black Vulture (Aegypius monachus), attaining a maximum size of 14 kg (31 lb), 1.2 m (3.9 ft) long and 3.1 m (10 ft) across the wings. Other vultures can be nearly as large, with the Himalayan Vulture (Gyps himalayensis) reaching lengths up to 1.5 m (4.9 ft) thanks in part to its long neck.

- The largest living eagle (the larger varieties of active-hunting raptors) is a source of contention, with the Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi), at up to 1.12 m (3.7 ft), being the longest. The Steller's Sea Eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus) of Asia's North Pacific, at unconfirmed weights of up to 12.7 kg (28 lb) and an average weight of 6.7 kg (15 lb), is regarded as the heaviest eagle. The Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja) of the neotropical forests is the often cited as the

- largest eagle, as well, and captive females have weighed up to 12.3 kg (27 lb). The longest-winged eagle ever was an Australian Wedge-tailed Eagle (Aquila audax) at 2.83 m (9.3 ft), though this species is not as large as the previous species. The Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) is barely smaller winged, with the Himalayan subspecies recorded to 2.77 m (9.1 ft). The Harpy and Philippine Eagles, due to having to navigate in deep forest, are relatively short-winged, and do not exceed 2 m (6.6 ft) or 2.2 m (7.2 ft), respectively, in wingspan. The now extinct Haast's Eagle (Harpagornis moorei), which existed alongside early aboriginal people in New Zealand, was easily the largest eagle known and perhaps the largest raptor ever. Adult female Haast's were estimated to average up to 1.4 m (4.6 ft) long, a 15 kg (33 lb) body weight and a relatively short 3 m (10 ft) wingspan.

- Waterfowl (Anseriformes)

- The largest species in general is the Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus buccinator) of Northern North America, which can reach an overall length of 1.82 m (6 ft), a wingspan of 3.1 m (10 ft) and a weight of 17.3 kg (38 lb). However, as is commonly the case in more widespread and physically variable birds occasionally outsizing their larger-on-average cousins, the heaviest waterfowl ever recorded was a cob Mute Swan (Cygnus olor) from Poland, which weighed 23 kg (50 lb) and was allegedly too heavy to take flight.

- The members of the previously mentioned Dromornithidae are now classified as members of this order, making them the largest "waterfowl" that ever lived.

- Swifts and allies (Apodiformes)

- The largest species are the White-naped Swift (Streptoprocne semicollaris), endemic to southern Mexico, and the Purple Needletail (Hirundapus celebensis), of the Philippine islands. Both reach similar large sizes, at up to 225 g (8 oz), more than 0.6 m (2.0 ft) across the wings and 25 cm (10 in) in length.

- The hummingbirds are also traditionally included in this order, the largest species of which is easily the Giant Hummingbird (Patagona gigas) of the Andes Mountains. "Giant" is a relative term among the hummingbirds, the smallest-bodied variety of birds, and this species weighs up to 24 g (0.85 oz) at a length of 23 cm (9.1 in).

- The longest hummingbird species, indeed the longest in the order, is the adult male Black-tailed Trainbearer (Lesbia victoriae), which can measure up to 25.5 cm (10.0 in), but a majority of this length is due to the extreme tail streamers. Another size champion among hummingbirds is the Sword-billed Hummingbird, a fairly large species in which about half of its 21 cm (8.3 in) length is from its bill (easily the largest bill-to-body-size ratio of any bird).

- Nightjars and allies (Caprimulgiformes)

- The largest species of this order of nocturnal, mysterious birds is the neotropical Great Potoo (Nycitbius grandis), the maximum size of which is about 680 g (1.5 lb) and 60 cm (2 ft). Heavier specimens have been recorded in the bulky Australian Tawny Frogmouth (Podargus strigoides) species, especially juvenile birds, which can weigh up to 1.4 kg (3.1 lb). Other species nearly as large as the potoo are the Papuan Frogmouth (Podargus papuensis) of New Guinea and the neotropic, cave-dwelling Oilbird (Steatornis caripensis), both at up to 48 cm (19 in).

- The largest species in the true nightjar family, the Great Eared-nightjar (Eurostopodus macrotis) of East Asia, is rather smaller at up to 150 grams (5.3 oz) and 41 cm (16 in). The wingspan in the Great Potoo and the Oilbird can be more than 1 m (3.3 ft), the largest of the order.

- Shorebirds (Charadriiformes)

- The largest species in this diverse order is the Great Black-backed Gull (Larus marinus) of the North Atlantic, attaining a size of as much as 0.79 m (2.6 ft), a wingspan of 1.7 m (5.6 ft) and weighing up to 2.3 kg (5.1 lb). The Glaucous Gull (L. hyperboreus) is, on average, somewhat smaller than the Black-back but has been weighed at as much as 2.7 kg (5.9 lb).

- Among the most prominent family of "small waders", the sandpipers reach their maximum size in the Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariensis) at up to 0.66 m (2.2 ft) and 1.1 m (3.6 ft) across the wings, although the more widespread Eurasian Curlew (N. arquata) can weigh up to 1.36 kg (3.0 lb).

- Less variable in size, the plovers largest species is the Australasian Masked Lapwing (Vanellus miles) at up to 0.4 m (1.3 ft) long, a 0.85 m (2.8 ft) wingspan and a weight of 400 g (14 oz). The terns, previously considered members of the gull family, are usually slender and dainty-looking in comparison but the largest species, the widely distributed Caspian Tern (Hydroprogne caspia), is quite large and heavily built. Caspians can range up to 782 g (1.72 lb), a 1.4 m (4.6 ft) wingspan and 0.6 m (2.0 ft) in length. The alcids

- largest extant member is the sub-Arctic Thick-billed Murre (Uria lomvia), which can range up to 1.48 kg (3.3 lb), a length of 0.48 m (1.6 ft) and a small wingspan of 0.76 m (2.5 ft). However, until its extinction at mankind's hands, the flightless Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) of the North Atlantic, was both the largest alcid and the largest member of the order. Great auks could range up to 6.8 kg (15 lb) and 0.9 m (3.0 ft) tall.

- Herons and allies (Ciconiiformes)

- The new world vultures are still generally considered a member of this order, although the inclusion is dubious at best. If they are included, the largest species in the order, if measured in regard to body weight and wingspan, is the Andean Condor (Vultur gryphus) of western South America. The great bird can reach a wingspan of 3.2 m (10.7 ft) and a weight of 15 kg (33 lb).

- The longest-bodied and tallest species in the order is probably the slender, towering Saddle-billed Stork of Africa (Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis), which often exceeds 1.5 m (5 ft) tall and has a wingspan of up to 2.7 m (8.9 ft). Reaching a similar or slightly shorter height but more heavily built among the storks are the neotropical Jabiru (Jabiru mycteria), the Asian Greater Adjutant (Leptoptilos dubius) and the African Marabou Stork (L. crumeniferus), all of which are believed to weigh up to 8 to 9 kg (18 to 20 lb). The latter two species, the Great Adjutant & the Marabou, at least nearly equals the Andean condor in maximum wingspan. All three are believed to exceptionally reach or exceed 3.16 m (10.5 ft) and are regarded as having the largest wingspan of any landbirds (that is species who live over land as opposed to tied to the sea or wetlands). Standing up to 1.53 m (5.0 ft), with a wingspan of up to 2.3 m (7.5 ft) and a weight up to 5 kg (11 lb) is the African Goliath Heron (Ardea goliath), the largest of the diverse and well-known herons and egrets. The White-bellied Heron (A. insignis) is generally smaller, but gigantic, unverified juveniles have been reported to 8.5 kg (18.8 lb) and 1.58 m (5.2 ft). Many of the largest flying birds in the fossil record may have been members of the Ciconiiformes. This may include the

- The largest ibises either bird are Giant Ibis (Thaumatibis gigantea) the largest of the world's ibises. Adults are reportedly 102–106 cm (40–42 in) long, with an upright standing height of up to 100 cm (39 in) and are estimated to weigh about 4.2 kg (9.3 lbs). Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 52.3–57 cm (20.6–22.4 in), the tail is 30 cm (12 in), the tarsus is 11 cm (4.3 in) and the culmen is 20.8–23.4 cm (8.2–9.2 in). The adults have overall dark grayish-brown plumage with a naked, greyish head and upper neck. There are dark bands across the back of the head and shoulder area and the pale silvery-grey wing tips also have black crossbars. The beak is yellowish-brown, the legs are orange, and the eyes are dark red. Juveniles have short black feathers on the back of the head down to the neck, shorter bills and brown eyes. having this Crested Ibis (Nipponia nippon) of Japan is a large (up to 78.5 cm long), white-plumaged ibis of pine forests. Its head is partially bare, showing red skin, and it has a dense crest of white plumes on the nape. This species is the only member of the genus Nipponia.

- largest flying bird ever, Argentavis magnificens, which is part of a group, the teratorns, that are considered an ally of the New World vultures.

- Mousebirds (Coliiformes)

- The mousebirds of Africa are remarkably uniform, but the largest species is seemingly the Speckled Mousebird (Colius striatus), at 2 oz (60 g) and over 14 in (35 cm).

- Pigeons (Columbiformes)

- The largest species of the pigeon/dove complex is the Victoria Crowned Pigeon (Goura victoria) of Northern New Guinea, although the other crowned pigeons approach similar sizes. Some exceptionally large Victoria Crowneds have reached 3.7 kg (8.2 lb) and 85 cm (34 in). The largest arboreal pigeon is the Marquesan Imperial-pigeon (Ducula galeata), which is up to about 0.8 m (2.6 ft) across the wings and can weigh 1 kg (2.2 lb). 3 flightless birds found on islands off of East Africa are the The largest extinct pigeons and doves Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratoritus) of North America The average weight of these pigeons was 340–400 g (12–14 oz) and, per John James Audubon's account, length was 42 cm (16.5 in) in males and 38 cm (15 in) in females.

- largest pigeons known to have existed: the Dodo (Raphus cucullatus), which was physically somewhat like an outsized pigeon, the Rodrigues solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria), a brown, long-necked birds that were superficially ratite-like. All three species may have exceeded 1 m (3.3 ft) in height. All were carelessly hunted it into extinction by humans and introduced animals. The Dodo is the most frequently crowned as the largest ever pigeon, as it could have weighed as much as 28 kg (62 lb), although recent estimates have indicated that an average wild Dodo would have weighed around 10.2 kg (22.5 lb), scarcely larger than a male turkey. If Dodos were this light, the Rodrigues solitaire may have been larger. Some estimates claim tha solitaire was merely swan-sized but others estimate weights of up to 27.8 kg (61.2 lb).

- Kingfishers and allies (Coraciiformes)

- The largest species is the Southern Ground Hornbill (Bucorvus leadbeateri), reaching sizes of as much as 6.2 kg (14 lb) and 1.3 m (4.3 ft) in length. Several arboreal, Asian hornbills can grow very large as well, with the Great Hornbill (Buceros bicornis) weighing to 4 kg (8.8 lb) and the Helmeted Hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) measuring as much as 1.7 m (5.6 ft) in total length. The larger hornbills have a wingspan of up to 1.83 m (6.0 ft).

- The largest kingfisher overall is the Giant Kingfisher (Megaceryle maxima), at up to 48 cm (19 in) long and 425 g (15.0 oz), with a large crest and finely spotted white on black upperparts. However, the common Australian species, the Laughing Kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae), may be heavier still, since individuals exceeding 450 g (1.0 lb) are not uncommon. A kookaburra wingspan can range up to 0.9 m (3.0 ft).

- Cuckoos and allies (Cuculiformes)

- The largest species of this order is the Great Blue Turaco (Corythaeola cristata), a cousin of the better-known cuckoos. This species, which can weigh over 1.25 kg (2.8 lb) and measure over 0.74 m (2.4 ft) in length, is rather larger than other turacos.

- The largest of the cuckoos is the Australasian Channel-billed Cuckoo (Scythrops novaehollandiae), which can range up to a weight of 0.93 kg (2.1 lb), a 1 m (3.3 ft) wingspan and a length of 0.66 m (2.2 ft).

- Falcons (Falconiformes)

- Many authorities now support the split of falcons from the Accipitriformes, despite similar adaptations, due to the genetic evidence showing they are not closely related. The largest species of falcon is the Gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus). Large females of this species can range up to 2.1 kg (4.6 lb), span 1.6 m (5.2 ft) across the wings and measure 0.66 m (2.2 ft) long. the largest extinct Titanohierax was a giant hawk about 8 kilograms that lived in the Antilles, where it was among the top predator.

- Gamebirds (Galliformes)

- The heaviest member of this diverse order is the North American Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). The largest specimen ever recorded was shot in 2002, and weighed 16.85 kg (37.1 lb) and 1.44 m (4.7 ft) in total length. The heaviest domesticated turkey on record, a very obese bird, weighed 37 kg (81 lb).

- The longest species, if measured from the tip of the bill to the end of the long tail coverts, is the male Green Peafowl (Pavo muticus) of Southeast Asia, at up to 3 m (10 ft) long. This is the longest overall length for any flying bird, although about two-thirds of the length is comprised by the tail coverts, and this species (to 5 kg (11 lb)) weighs less than its cousin, the Indian Peafowl (P. cristatus), at up to 6 kg (13 lb). Although, wingspan is relatively small in most galliformes, both larger peafowl species can span as much as 1.6 m (5.2 ft) across the wings.

- The largest member of the grouse family is the Eurasian Western Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus), at up to 6.7 kg (15 lb) and 1 m (3 ft). A prehistoric, flightless family, sometimes called (incorrectly) "giant megapodes" (Sylviornis) of New Caledonia were the most massive galliformes ever, having reached 1.7 m (5.6 ft) long and weighed up to about 40 kg (88 lb).

- Loons (Gaviiformes)

- The largest species on average is the Yellow-billed Loon (Gavia adamsii) of the Arctic, at up to 1 m (3.3 ft) and 7 kg (15.4 lb). However, one exceptionally large North American Common Loon (Gavia immer), weighed 8 kg (17.6 lb), heavier than any recorded Yellow-billed Loon. Wingspan in these largest loons can reach 1.52 m (5.0 ft).

- Cranes and allies (Gruiformes)

- The males of the Eurasian Great Bustard (Otis tarda) and the African Kori Bustard (Ardeotis kori) are the heaviest birds capable of flight, averaging up to 16 kg (35 lb) and weighing 2 to 3 times as much as their female counterparts. It is not resolved if one of these species is larger than the other, but both can reach a weight of at least 21 kg (46 lb) and measure up to 1.53 m (5.0 ft) long. Some Kori bustards have been reported from 23 kg (51 lb) to even 40 kg (88 lb), but all such reports are unverified or dubious.

- The tallest flying bird on earth, also represented in the Gruiformes, is the Sarus Crane (Grus antigone) of Southern Asia and Australia, which can reach a height of 2 m (6.6 ft). Heavier cranes are reported in other species, the Red-crowned Crane (Grus japonensis) and the Siberian Crane (G. leucogeranus), both from Northeast Asia and both at up to 15 kg (33 lb), as opposed to a top weight of 12.8 kg (28 lb) in the Sarus. Wingspan in both the largest cranes and the largest bustards can range up to 2.5–3 m (8.2–10 ft).

- The most species-rich family in this order, the rails, reaches their largest size in the bulky Takahē (Porphyrio hochstetteri) of New Zealand, an endangered species that can weigh up to 4.2 kg (9.3 lb) and measure 0.65 m (2.1 ft) long. The afforement-mentioned "terror bird", Brontornis burmeisteri, has traditionally been classified as a member of this order, although this may not be an accurate classification.

- Songbirds (Passeriformes)

- The passerine or songbird order comprises more than half of all bird species, and are known for their generally small size, their strong voices and their frequent perching. Corvids are the largest of passerines, particularly the large races of the Common Raven (Corvus corax) and the Northeast African Thick-billed Raven (C. crassirostris). Large ravens can weigh 2 kg (4.4 lb), attain a 1.5 m (5.0 ft) wingspan and measure 0.8 m (2.6 ft) long.

- The closest non-corvid contender to largest size is the Australian Superb Lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae), which can reach a length of 1 m (3.3 ft), much of it comprised by their spectacular tail, and a weight of 1 kg (2.2 lb).

- The largest species in the most species-rich passerine family, Tyrannidae or tyrant-flycatchers, is the Great Shrike-Tyrant of the South Andes (Agriornis lividus), at 99.2 g (3.5 oz) and 31 cm (12 in), although the Fork-tailed Flycatcher (Tyrannus savana), to 41 cm (16 in), is longer thanks to its extreme tail.

- The namesake of the previous family, the Old World flycatchers, reaches its maximum size in the Green Cochoa of Southeast Asia (Cochoa viridis), if it is indeed a proper member of the family, at up to 122 g (4.3 oz) and a length of 29 cm (11 in). Closely related to the Old World flycatchers and internationally well-known, the thrush family's

- largest representative is the Blue Whistling-thrush of India and Southeast Asia (Myophonus caeruleus), at up to 230 g (8.1 oz) and 36 cm (14 in).

- The largest bird family in Eurasia is the Old World warblers. As previously classified these warblers could get fairly large, up to 57 g (2.0 oz) and 28 cm (11 in) in the Striated Grassbird of Southeast Asia (Megalurus palustris). The Old World warblers have been split into several families, however, which leaves the Barred Warbler of central Eurasia (Sylvia nisoria), up to 36 g (1.3 oz) and 17 cm (6.7 in), as the largest "true warbler".

- Not to be confused with the previous family, the largest of the well-known New World warblers is the aberrant Yellow-breasted Chat (Icteria virens), which can exceptionally measure up to 22 cm (8.7 in) and weigh 53 g (1.9 oz).

- Another large family is the bulbuls, the largest of which is the south Asian Straw-headed Bulbul (Pycnonotus zeylanicus), to 94 g (3.3 oz) and 29 cm (11 in). The diverse, large family of babblers can reach 35 cm (14 in) and 170 g (6.0 oz) in the south Asian Greater Necklaced Laughingthrush (Garrulax pectoralis).

- The familiar domesticated species, the Java Sparrow (Padda oryzivora), is (in the wild) the largest estrild, at up to 28.3 g (1 oz) and 17 cm (6.7 in). **The largest honeyeater, perhaps the most diverse Australasian bird family, is the Crow Honeyeater (Gymnomyza aubryana), at up to 290 g (10 oz) and 30 cm (12 in). The largest of the "true finches" is the Collared Grosbeak (Mycerobas affinis) of central and south Asia at up to 23 cm (9.1 in) and 80 g (2.8 oz).

- Among the largest bird families, the emberizids, reaches its largest size in the Abert's Towhee (Pipilo aberti) of Southwest United States and north Mexico at up to 23 cm (9.1 in) and 80 g (2.8 oz).

- Closely related to the previous family is the tanagers, which can range up to 140 g (4.9 oz) in the Andean-forest-dwelling White-capped Tanager (Sericossypha albocristata). Another species-rich neotropical family is the ovenbirds, **the largest of which, the Great Rufous Woodcreeper (Xiphocolaptes major) of the Amazonian rainforests, can weigh up to 162 g (5.7 oz) and 35 cm (14 in). The specialized antbird family can range up to 156 g (5.5 oz) and 35.5 cm (14 in) in the Giant Antshrike (Batara cinerea). Among the most variably sized passerine families is the icterids.

- The largest icterid is the Amazonian Oropendola (Psarocolius bifasciatus), in which males can range up to 52 cm (1.7 ft) and 550 g (1.2 lb). The latter species competes with the similarly sized Amazonian Umbrellabird (Cephalopterus ornatus) as the largest passerine in South America.

- Cormorants and allies (Pelecaniformes)

- The pelicans rank amongst the largest flying birds. The largest species of pelican is the Eurasian Dalmatian Pelican (Pelecanus crispus), which attains a length of 1.83 m (6.0 ft) and a body weight of 15 kg (33 lb). The Great White Pelican (P. onocrotalus) of Europe and Africa is nearly as large. The Australian Pelican (P. conspicillatus) is slightly smaller but has the largest bill of any bird, at as much as 49 cm (19 in) long. A large pelican can attain a wingspan of 3.6 m (11.8 ft), second only to the great albatrosses among all living birds.

- The largest of the cormorants is the Flightless Cormorant of the Galapagos Islands (Phalacrocorax harrisi), at up to 5 kg (11 lb) and 1 m (3.3 ft), although large races in the Great Cormorant (P. carbo) can weigh up to 5.3 kg (12 lb). The Spectacled Cormorant of the North Pacific (P. perspicillatus), which went extinct around 1850, was larger still, averaging around 6.4 kg (14 lb) and 1.15 m (3.8 ft).

- The widely distributed Magnificent Frigatebird is of note for having an extremely large wingspan, up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft), for its relatively light body, at up to only 1.9 kg (4.2 lb).

- A family of birds, Pelagornithidae or pseudotooth birds, included several species that were behind only Argentavis magnificens in size among all flying birds. Characterized by the tooth-like protrusions along their bills, this unique family has been variously allied with the Pelecaniformes, the tubenoses, the large waders and even the waterfowl. Their true linkage to extant birds remains in question, though pelecaniformes are the group most regularly considered related. Some of the largest pseudotooth birds have included, Osteodontornis of the late Miocene from the North Pacific, Gigantornis eaglesomei, from the Eocene era in what is now Nigeria and Dasornis, from Eocene era Europe. A new, unnamed species has been discovered which may outsize even these giants. Superficially albatross-like, each of these pseudotooth species may have attained lengths of 2.1 m (7 ft) long and wingspans of at least 6 m (20 ft). Body mass in these slender birds was probably only up to around 29 kg (64 lb).

- Flamingos (Phoenicopteriformes)

- The largest flamingo is the Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus ruber) of Eurasia and Africa. One of the tallest flying birds in existence when standing upright (exceeded only by the tallest cranes), this species typically weighs 3.5 kg (7.7 lb) and stands up to 1.53 m (5.0 ft) tall. However, at maximum size, a male can weigh up to 4.55 kg (10.0 lb) and stand as high as 1.87 m (6.1 ft). Wingspan is relatively small in flamingos, but can range up to 1.65 m (5.4 ft).

- Woodpeckers and allies (Piciformes)

- The largest species of this diverse order is the Toco Toucan (Ramphastos toco) of the neotropic forest. Large specimens of this toucan can weigh to 870 g (1.9 lb) and 0.65 m (2.1 ft), at which size the magnificent beak alone could measure about 20 cm (7.9 in).