| Revision as of 16:20, 26 January 2015 editKrobison13 (talk | contribs)398 edits →July 1789–1792: The French Revolution: Cleaned up paragraph on Saint Cloud stay -- removed redundancy, fixed grammar & run-ons← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:21, 26 January 2015 edit undoKrobison13 (talk | contribs)398 edits →July 1789–1792: The French Revolution: small punctuation/grammar fixes on Fete paragraphNext edit → | ||

| Line 190: | Line 190: | ||

| The summer of 1790 brought to Marie Antoinette and her family a limited amount of relief, as they were allowed to spend it in the castle of Saint Cloud, which belonged to the Queen. While her situation as a prisoner did not change, she had much greater personal freedom than in Paris, since she was free from the radical elements who surrounded her and followed all her movements in the capital. During this time, she met Mirabeau in secret, an event which could not have happened in Paris. | The summer of 1790 brought to Marie Antoinette and her family a limited amount of relief, as they were allowed to spend it in the castle of Saint Cloud, which belonged to the Queen. While her situation as a prisoner did not change, she had much greater personal freedom than in Paris, since she was free from the radical elements who surrounded her and followed all her movements in the capital. During this time, she met Mirabeau in secret, an event which could not have happened in Paris. | ||

| The only time the royal couple returned to Paris in that period was in 14 July 1790 for the official celebration of the Fall of the Bastille, "The Fete de la Federation". The Abbe Talleyrand said a commemorative Mass in Paris |

The only time the royal couple returned to Paris in that period was in 14 July 1790 for the official celebration of the Fall of the Bastille, "The Fete de la Federation". The Abbe Talleyrand said a commemorative Mass in Paris and at least 300,000 persons participated from all over France including 18,000 National Guards. At the event, the King was greeted with numerous cries of "Long Live The King ", especially when he took the oath to protect the Nation and to apply the laws voted by the Constitutional Assembly. There were even some cheers to the Queen, particularly when she presented her son to the Public. Mirabeau advised Marie Antoinette to leave Paris and to travel inside France to profit from the commemoration of the 14 of July, but the Queen was already thinking of leaving France and turning for Foreign Powers to help her crush the Revolution.<ref>{{Harvnb|2001|Fraser|pp=314-316}}</ref> | ||

Revision as of 16:21, 26 January 2015

For other uses, see Marie Antoinette (disambiguation).Queen consort of France and Navarre

| Marie Antoinette of Austria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Maria Antoinette, Queen of France and Navarre, by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, ca. 1779. Maria Antoinette, Queen of France and Navarre, by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, ca. 1779. | |||||

| Queen consort of France and Navarre | |||||

| Tenure | 10 May 1774 – 21 September 1792 | ||||

| Born | (1755-11-02)2 November 1755 Hofburg Palace, Vienna, Austria | ||||

| Died | 16 October 1793 (aged 37) Place de la Révolution, Paris, France | ||||

| Burial | 21 January 1815 Saint Denis Basilica, France | ||||

| Spouse | Louis XVI of France | ||||

| Issue | Marie Thérèse, Duchess of Angoulême Louis Joseph, Dauphin of France Louis XVII of France Princess Marie Sophie | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Habsburg-Lorraine | ||||

| Father | Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor | ||||

| Mother | Maria Theresa | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Marie Antoinette (/məˈriː æntwəˈnɛt/ or /æntwɑːˈnɛt/; French: [maʁi ɑ̃twanɛt]; baptised Maria Antonia Josepha (or Josephina) Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793), born an Archduchess of Austria, was Dauphine of France from 1770 to 1774 and Queen of France and Navarre from 1774 to 1792. She was the fifteenth and penultimate child of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa and Emperor Francis I.

In April 1770, upon her marriage to Louis-Auguste, Dauphin of France, she became Dauphine of France. She assumed the title Queen of France and of Navarre when her husband ascended the throne as Louis XVI upon the death of his grandfather Louis XV in May 1774. After seven years of marriage, she gave birth to a daughter, Marie-Thérèse Charlotte, the first of her four children.

Initially charmed by her personality and beauty, the French people eventually came to dislike her, accusing "L'Autrichienne" (which literally means the Austrian (woman), but also suggests the French word "chienne", meaning bitch) of being profligate, promiscuous, and of harbouring sympathies for France's enemies, particularly Austria, her country of origin. The Diamond Necklace incident damaged her reputation further, although she was completely innocent in this affair. She later became known as Madame Déficit because France's financial crisis was blamed on her lavish spending.

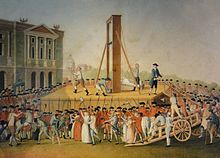

The royal family's flight to Varennes had disastrous effects on French popular opinion: Louis XVI was deposed and the monarchy abolished on 21 September 1792; the royal family was subsequently imprisoned at the Temple Prison. Nine months after her husband's execution, Marie Antoinette was herself tried, convicted by the Revolutionary Tribunal of treason to the principles of the revolution, and executed by guillotine on 16 October 1793.

Long after her death, Marie Antoinette is often considered to be a part of popular culture and a major historical figure, being the subject of several books, films and other forms of media. Some academics and scholars have deemed her frivolous and superficial, and have attributed the start of the French Revolution to her in addition to the beginning of the war of 1792 which ended with the Congress of Vienna ; however, others have claimed that she was treated unjustly and that views of her should be more sympathetic.

Early life

Maria Antoinette was born on November 2, 1755 in Vienna. She was the youngest daughter of Empress Maria Theresa, ruler of the Habsburg dominions, and Emperor Francis I. The next day, she was baptised . Described at her birth as "a small, but completely healthy archduchess", she was also known at the Austrian court as Madame Antoine.

The relaxed ambience of court life in the Hofburg, was compounded by the private life which was developed by the Habsburgs even before Maria Antonia was born.

Maria Antonia had a relatively simple childhood. She was never lonely. This was particularly evident in her relationship with her older sister, Maria Carolina.

Antonia's education was poor, her handwriting, for instance, was sprawling and careless in form. The emphasis in Marie Antoinette's education was on manners, dance, music and appearance. Around ten years old, she still had trouble reading, as well as writing. Conversations with her were stilted. Mme de Brandeis, made responsible by the empress for the princess' lack of education was fired and replaced by the much more severe, Mme de Lerchenfeld. She drew often.

Antonia learned to play the harp, taught by Gluck. During the family's musical evenings, she would sing. She also excelled at dancing. She had an "exquisite" poise and a famously graceful deportment; She also loved dolls as a young girl. Numerous dolls arrived at the Hofburg as soon as Marie Antoinette turned 13.By many accounts, her childhood was somewhat complex.

Her "private" life was more relaxed than other European princesses'. She also developed a mistrust of intelligent older women as a result of her mother's close relationship with the Archduchess Maria Christina, Duchess of Teschen, Marie Antoinette's older sister.

Marriage to Louis: 1770–1793

The events leading to her eventual betrothal to the Dauphin of France began in 1765, when her father, Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor, died of a stroke in August, leaving Maria Theresa to co-rule with her eldest son and heir, the Emperor Joseph II. Without the Seven Years' War to "unite" the two countries briefly, the marriage of Maria Antonia and the Dauphin Louis-Auguste might not have occurred.

In 1767, a smallpox outbreak hit the family. Maria Antonia had already survived the disease as a young child. The princess's smile was "very beautiful and straight". After painstaking work between the governments of France and Austria, the dowry was set at 200,000 crowns. Finally, Maria Antonia was married by proxy on 19 April (at age 14) in the Church of the Augustine Friars, Vienna.

Marie Antoinette was officially handed over to her French relations on 7 May 1770. Chief among them was comtesse de Noailles, who had been appointed the Dauphine's Mistress of the Household by Louis XV and who controlled Marie Antoinette daily life at least until 1774 . She met the King, the Dauphin Louis-Auguste, and the royal aunts. Before reaching Versailles, she also met her future brothers-in-law, Louis Stanislas Xavier, comte de Provence; and Charles Philippe, comte d'Artois. Later, she met the rest of the family, including her husband's youngest sister, Madame Élisabeth.

The ceremonial wedding of the Dauphin and Dauphine took place on 16 May 1770, in the Palace of Versailles, after which was the ritual bedding. It was assumed by custom that consummation of the marriage would take place on the wedding night. However, this did not occur, and the lack of consummation plagued the reputation of both Louis-Auguste and Marie Antoinette for seven years to come.

The initial reaction to the marriage between Marie Antoinette and Louis-Auguste was mixed. On the one hand, the Dauphine herself was popular among the people. Her first official appearance in Paris on 8 June 1773 at the Tuileries was considered by many royal watchers a resounding success. People were easily charmed by her personality and beauty. She had fair skin, straw-blond hair, blue eyes and with her high heels and majestic tall figure, she was a head taller than her court acquaintances, including her family.

However, the match was unpopular among the elder members of the Court. They accused her of trying to sway the king to Austria's thrall, destroying long-standing traditions and of laughing at the influence of older women at the royal court. Many other courtiers, such as the comtesse du Barry, had tenuous relationships with the Dauphine.

Her relationship with the comtesse du Barry was one which was important to rectify, at least on the surface, because Madame du Barry was the mistress of Louis XV, and thus had considerable political influence over the king. In fact, she had been instrumental ousting from power the duc de Choiseul, who had helped orchestrate the Franco-Austrian alliance as well as Marie Antoinette's own marriage. After months of continued pressure from her mother and the Austrian minister, the comte de Mercy-Argenteau, Marie Antoinette grudgingly agreed to speak to Mme du Barry on New Year's Day 1772 in order to stop any French protest on the partition of Poland. Although the limit of their conversation was Marie Antoinette's banal comment to the royal mistress that, "there are a lot of people at Versailles today", Mme du Barry was satisfied by her victory with the result that she controlled Marie Antoinette daily life until 1774 and the crisis, for the most part, dissipated. Later, Marie Antoinette became more polite to the comtesse because she needed her approval before doing anything important, pleasing Louis XV, but also particularly her mother.

From the beginning, the Dauphine had to contend with constant letters from her mother, who was receiving secret reports on her daughter's behavior from Mercy d'Argenteau . Marie Antoinette would write home in the early days saying that she missed her dear home.

Marie Antoinette began to spend more on gambling with cards and horse-betting as well as trips to the city and new clothing, shoes, pomade and rouge.

Marie Antoinette also began to form deep friendships with various ladies in her retinue. Most noted were the sensitive and "pure" widow, the princesse de Lamballe, whom she appointed as Superintendent of her Household, and the fun-loving, down-to-earth Yolande de Polastron, duchesse de Polignac, who eventually formed the cornerstone of the Queen's inner circle of friends (Société Particulière de la Reine). The closeness of the Dauphine's friendship with these ladies, influenced by various popular publications which promoted such friendships, later caused accusations of lesbianism to be lodged against these women. Others taken into her confidence at this time included her husband's brother, the comte d'Artois; their youngest sister, Madame Élisabeth; her sister-in-law, the comtesse de Provence; and Christoph Willibald Gluck, her former music teacher, whom she took under her patronage upon his arrival in France.

On 27 April 1774, Louis XV fell ill with smallpox. On 4 May, the King died at the age of 64. Louis-Auguste was crowned King Louis XVI of France on 11 June 1775 at the cathedral of Rheims. Marie Antoinette was not crowned alongside him, merely accompanying him during the coronation ceremony.

Queenship: 1774–1792

1774–1778: Early years

At the outset the new Queen had limited political influence with her husband. Louis blocked many of her candidates, including Choiseul, from taking important positions, aided and abetted by his two most important ministers, Chief Minister Maurepas and Foreign Minister Vergennes. In spite of that the Queen played a decisive role in the disgrace and exile of the most powerful of Louis XV ministers, the Duke of Aiguillon.

On 6 August 1775, Marie Antoinette's situation became more precarious when her sister-in-law the comtesse d'Artois gave birth to a son, the duc d'Angoulême.

Personal attacks caused the Queen to plunge further into the costly diversions of buying her dresses from Rose Bertin and gambling, simply to enjoy herself. For formal occasions, she adopted a hair style, the pouf, created shortly before by her hairdresser, Léonard Autié. On one famed occasion, she played for three days straight with players from Paris, straight up until her 21st birthday. She also began to attract various male admirers whom she accepted into her inner circles, including the baron de Besenval, the duc de Coigny, and Count Valentin Esterházy.

She was given free rein to renovate the Petit Trianon, a gift to her by Louis XVI on 15 August 1774; The Petit Trianon became associated with Marie Antoinette's perceived extravagance. With the "English garden" Marie Antoinette and her court adopted the English dress of indienne, of percale or muslin. The tradition of costume at the court at Versailles was broken after more than ten years. Rumors circulated that she plastered the walls with gold and diamonds. Her lady-in-waiting Jeanne-Louise-Henriette Campan replied on such rumors that Marie Antoinette visited the workshops of the village in a simple dress of white percale with a gauze scarf and a straw hat.

"...the innovativeness of Marie Antoinette's country retreat would attract her subjects’ fierce disapproval, even as it aimed to bolster her autonomy and enhance her prestige..."

Repayment of the debt incurred by France during the Seven Years' War remained a difficult problem, further exacerbated by Vergennes and Marie Antoinette prodding Louis XVI to involve France in Great Britain's war with its North American colonies. Amidst preparations for sending aid to the American rebels and in the atmosphere of the first wave of libelles, Holy Roman Emperor Joseph came to call on his sister and brother-in-law on 18 April 1777. During the subsequent six-week visit to Versailles, Joseph investigated why the royal marriage had not been consummated. He soon realized that no obstacle to the couple's conjugal relations existed, save the Queen's lack of interest and the King's unwillingness to exert himself in that arena, due to a mistaken belief that relations weakened the male partner. In a letter to his brother Leopold, Joseph graphically described them as "a couple of complete blunderers." Due to Joseph's intervention, the marriage was finally consummated in August 1777. Eight months later, in April, it was suspected that the Queen was finally pregnant with her first child, which was confirmed on 16 May 1778.

1778–1781: Motherhood

In the middle of her pregnancy, two events occurred which had a profound impact on the Queen's later life. First, there was the return of the handsome Swede, Count Axel von Fersen—to Versailles for two years. Secondly, the King's wealthy but spiteful cousin, the duc de Chartres, was disgraced by his questionable conduct during the Battle of Ouessant against the British. In addition, Marie Antoinette's brother, the Emperor Joseph, began making claims on the throne of Bavaria based upon his second marriage to the princess Maria Josepha of Bavaria. Marie Antoinette pleaded with her husband for the French to help intercede on behalf of Austria . The Peace of Teschen, signed on 13 May 1779, ended the brief conflict with the Queen imposing French mediation on the demand of her mother and Austria gaining a territory of 100,000 persons, a strong retreat from the early French position who was hostile towards Austria.

Marie Antoinette's daughter, Marie-Thérèse Charlotte was finally born at Versailles, after a particularly difficult labour, on 19 December 1778. The King himself—rather unusually—let in some air by tearing off the tapes that sealed the windows. As a result of this harrowing experience, the Queen and the King banned most courtiers from entering her bedchamber for subsequent labours.

The baby's paternity was contested in the libelles, but not by the King himself, who was close to his daughter.

The birth of a daughter meant that pressure to have a male heir continued, and Marie Antoinette wrote about her worrisome health, which might have contributed to a miscarriage in July 1779.

Meanwhile, the Queen began to institute changes in the customs practised at court, with the approval of the King. Some changes, such as the abolition of segregated dining spaces, had already been instituted for some time and had been met with disapproval from the older generation. More importantly was the abandonment of heavy make-up and the popular wide-hooped panniers for a more simple feminine look, typified first by the rustic robe à la polonaise and later by the 'gaulle,' a simple muslin dress that she wore in a 1783 Vigée-Le Brun portrait. She also began to participate in amateur plays and musicals, starting in 1780, in a theatre built for her and other courtiers who wished to indulge in the delights of acting and singing.

In 1780, two candidates who had been supported by Marie Antoinette for positions, the marquis de Castries, and the comte de Ségur, were appointed Minister of the Navy and Minister of War, respectively. It was the support of the Queen that enabled them to secure their positions. After the resignation of Jacques Necker in 1781, Marie Antoinette became the only political reference of the two ministers and she would support their attempts to prevent the middle classes from reaching high positions in the Army and Navy, thus causing one of the main reasons for the outbreak of the French Revolution. Finally, the Queen played in 1783 a decisive role in the nomination of Charles Alexandre de Calonne, a close friend of the Polignacs, as Financial Minister and baron de Breteuil as the Minister of Royal Household making him perhaps the strongest and most conservative minister of the reign. The result of these two nominations was that Marie Antoinette's influence became paramount in government

Later that year, Empress Maria Theresa began to fall ill and died on 29 November 1780, in Vienna, at the age of 63. Marie Antoinette was worried that the death of her mother would jeopardise the Franco-Austrian alliance (as well as, ultimately, herself), but Emperor Joseph reassured her through his own letters that he had no intention of breaking the alliance.

Three months after the empress' death, it was rumoured that Marie Antoinette was pregnant again, which was confirmed in March 1781. Another royal visit from Joseph II in July, partially to reaffirm the Franco-Austrian alliance and also to see his sister again, was tainted with rumours that Marie Antoinette was siphoning treasury money to him.

On 22 October 1781, the Queen gave birth to Louis Joseph Xavier François, who bore the title Dauphin of France. He would, according to courtiers, try to frame sentences to put in the phrase "my son the Dauphin" in the weeks to come.

1782–1785: Declining popularity

Despite the general celebration over the birth of the Dauphin, Marie Antoinette's political influence, such as it was, did benefit Austria. During the so-called Kettle War, in which her brother Joseph attempted to open the Scheldt River for naval passage; Marie Antoinette succeeded in obliging Vergennes to pay a huge financial compensation to Austria. Finally, the Queen was able to have her brother's support against England and she neutralized French hostility to his alliance with Russia.

When accused of being a "dupe" by her brother for her political inaction, Marie Antoinette responded that sometimes she had little power. She claimed she had to pretend to the ministers that she was in the full confidence of the King in order to get the information she wanted. The Queen however was not telling her brother the whole truth because she was beginning to protect her children's interests by balancing her position between Austria and France; the truth was that slowly but surely Marie Antoinette political influence was beginning to be paramount in the state.

Her temperament was more suited to personally directing the education of her children. In particular, after the royal governess at the time of the Dauphin's birth, the princesse de Guéméné, went bankrupt and was forced to resign, there was a controversy over who should replace her. Marie Antoinette appointed her favourite, the duchesse de Polignac, to the position. This decision met with disapproval from the court, as the duchess was considered to be of too "immodest" a birth to occupy such an exalted position.. On the other hand, the Queen trusted Mme de Polignac completely and gave her millions of livres every year .

In June 1783, Marie Antoinette was pregnant again. Later that month, Count Axel von Fersen returned from America, in order to secure a military appointment, and he was accepted into her private society. Marie Antoinette suffered a miscarriage on the night of 1–2 November 1783, prompting more fears for her health.

Trying to calm her mind, during Fersen's first visit, and later after his return on 7 June 1784, the queen occupied herself with the creation of the Hameau de la reine, a model hamlet in the garden of the Petit Trianon. Started in 1783 and finished in 1787, the Queen's hamlet, built to the designs of her favoured architect, Richard Mique, was complete with farmhouse, dairy, and mill. Its creation, however, unexpectedly caused another uproar when the price of the Hameau was criticized by her critics.

In addition to the creation of the Hameau, Marie Antoinette had other notable interests and activities. She became an avid reader of historical novels, and her scientific interest was piqued enough to become a witness to the launching of hot air balloons. She was fascinated by Rousseau's "back to nature" philosophy about which she had books in her library. Briefly, she even sought out important British personages such as the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, and the British ambassador to France, the Duke of Dorset. She was able to write in broken English to her friend, the Duchess of Devonshire.

Despite the many things which Marie Antoinette did in her spare time, her primary concern became the health of the Dauphin, which was beginning to fail. By the time Fersen returned to Versailles in 1784, it was widely thought that the sickly Dauphin would not live to be an adult. During this time, Beaumarchais' play The Marriage of Figaro premiered in Paris. After initially having been banned by the king due to its negative portrayal of the nobility, the play was ironically finally allowed to be publicly performed because of its overwhelming popularity at court, where secret readings of it had been given.

In August 1784, the queen reported that she was pregnant again. With the future enlargement of her family in mind, she bought the Château de Saint-Cloud, a place she had always loved, from the duc d'Orléans, the father of the previously disgraced duc de Chartres. This was a hugely unpopular acquisition, particularly with some factions of the nobility who already disliked her, but also with a growing percentage of the population who felt shocked that a French queen might own her own residence, independent of the king. Despite having the baron de Breteuil working on her behalf, the purchase did not help improve the public's image of the queen as frivolous. The château's expensive price, almost 6 million livres, plus the substantial extra cost of redecorating it, ensured that there was much less money going towards repaying France's substantial debt.

On 27 March 1785, Marie Antoinette gave birth to a second son, Louis Charles, who was created the duc de Normandie. Louis Charles was visibly stronger than the sickly Dauphin, and the new baby was affectionately nicknamed by the Queen, chou d'amour. The fact that this delivery occurred exactly nine months following Fersen's visit did not escape the attention of many, and though there is much doubt and historical speculation about the parentage of this child, public opinion towards her decreased noticeably. It is the belief of most of Marie-Antoinette's biographers and the young prince's that he was the biological son of Louis XVI and not Axel von Fersen, even among those biographers who believe the Queen was in love with Fersen. Courtiers at Versailles noted in their diaries at the time that the date of the child's conception in fact corresponded perfectly with a period when the King and Queen had spent a lot of time together, but these details were ignored amid attacks on the Queen's character. These suspicions of illegitimacy, along with the continued publication of the libelles, a never-ending cavalcade of court intrigues, the actions of Joseph II in the Kettle War, and her purchase of Saint-Cloud combined to turn popular opinion sharply against the Queen, and the image of a licentious, spendthrift, empty-headed foreign Queen was quickly taking root in the French psyche.

1786-1789: Prelude to revolution

A second daughter, Sophie Hélène Béatrice de France, was born on 9 July 1786, but died on 19 June 1787.

Continuing deterioration of the financial situation in France, despite cutbacks to the royal retinue, ultimately forced the King and his current Minister of Finance, Calonne, to call the Assembly of Notables, after a hiatus of 160 years. The assembly was held to try to pass some of the reforms needed to alleviate the financial situation which the Parlements refused to cooperate. The first meeting of the assembly took place on 22 February 1787, at which Marie Antoinette was not present. Later, her absence resulted in her being accused of trying to undermine the purpose of the assembly.

However, the Assembly was a failure, as it did not pass any reforms and instead fell into a pattern of defying the King. The King on the urging of the Queen dismissed Calonne on 8 April 1787; Vergennes died on 13 February.

During this time, the Queen began to abandon her more carefree activities to become more involved in politics than ever before, and mostly with the interests of Austria and her children. This was for a variety of reasons. First, her children were Enfants de France, and thus their future as leaders of France needed to be assured. Second, by concentrating on her children, the Queen sought to improve the dissolute image she had acquired from the "Diamond Necklace Affair", in which she had been accused of participating in a crime to defraud the crown jewelers of the cost of a very expensive diamond necklace. Third, the king had begun to withdraw from a decision-making role in government due to the onset of an acute case of depression. The symptoms of this depression were passed off as drunkenness by the libelles. As a result, Marie Antoinette finally emerged as a politically viable entity. In her new capacity as a politician with a very high degree of power, the queen tried to help the situation brewing between the assembly and the king.

This change in her political role signalled the beginning of the end of the influence of the duchesse de Polignac, as Marie Antoinette began to dislike the duchesse's huge expenditures and their impact on the finances of the Crown. The duchesse left for England in May, leaving her children behind in Versailles. Also in May, Étienne Charles de Loménie de Brienne, the archbishop of Toulouse and one of the Queen's political allies, was appointed by the King on Marie Antoinette urging and orders to replace Calonne first as the Finance Minister and then as Prime Minister. He began instituting more cutbacks at court and to restore the absolute power of the King and Queen who were weakened by parliaments .

Brienne, though, was not able to improve the financial situation. Since he was the queen's ally and creature, this failure adversely affected her political position. The continued poor financial climate of the country resulted in the 25 May dissolution of the Assembly of Notables because of its inability to get things done. This lack of solutions was fairly blamed on the Queen. The financial problems resulted from a combination of several factors. There had been too many expensive wars, a too-large royal family headed by the Queen whose large frivolous expenditures far exceeded the resources of the state, and an unwillingness on the part of many of the aristocrats and Marie Antoinette who were in charge to help defray the costs of the government out of their own pockets with higher taxes. Marie Antoinette earned the nickname of "Madame Déficit" in the summer of 1787 as a result of the public perception that she had singlehandedly ruined the national finances. While sole fault for the financial crisis did not lie with the queen, Marie Antoinette was the biggest obstacle to any major reform effort. She played a decisive role in the disgrace, exile and partial imprisonment of the Reformer Ministers of Finance, Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, Baron de Laune and Necker. She spent a lot of money on her favorites and on herself, more than any other person in France. Finally the expense of the court was much higher than the official estimate of 7% of the state budget, if the secret expenses of the Queen were taken into account. The Queen attempted to fight back with propaganda portraying her as a caring mother, most notably the premier at Royal Académie Salon de Paris in August 1787 of a portrait of her and her children by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. This attack strategy was eventually dropped, however, because of the death of the Queen's youngest child, Sophie. Around the same time, Jeanne de Lamotte-Valois escaped from prison in France and fled to London, where she published more damaging lies concerning her supposed "affair" with the queen.

The political situation in 1787 began to worsen when on Marie Antoinette urging the Parlement was exiled, and culminated on 11 November, when the king tried to use a lit de justice to force through legislation. He was unexpectedly challenged by his formerly disgraced cousin, the duc de Chartres, who had inherited the title of duc d'Orléans at the death of his father in 1785. The new duc d'Orléans publicly protested the King's actions, and was subsequently exiled. The May Edicts issued on 8 May 1788 were also opposed by the public. Finally, on 8 July and 8 August, the King announced his intention to bring back the Estates General, the traditional elected legislature of the country which had not been convened since 1614.

Marie Antoinette was not directly involved with the exile of the Parlement, the May Edicts or with the announcement regarding the Estates General, but she did participate in the King Council, the first Queen to do this in the last hundred years, and she was taking the major decisions behind the scene and in Council . Her primary concern in late 1787 and 1788 was the improved health of the Dauphin, who suffered from tuberculosis, which had twisted and curved his spinal column severely. He was brought to the château at Meudon in the hope that its country air would help the young boy recover, but instead the Dauphin's condition continued to deteriorate.

The Queen was instrumental in the recall of Jacques Necker as Finance Minister on 26 August, a popular move, even though she herself was worried that the recall would again go against her if Necker was unsuccessful in reforming the country's finances.

Her prediction began to come true when bread prices started to rise due to the severe 1788–1789 winter. The Dauphin's condition worsened even more, riots broke out in Paris in April, and on 26 March, Louis XVI himself almost died from a fall off a roof.

"Come, Léonard, dress my hair, I must go like an actress, exhibit myself to a public that may hiss me", the Queen quipped to her hairdresser, who was one of her "ministers of fashion", as she prepared for the Mass celebrating the return of the Estates General on 4 May 1789. She knew that her rival, the duc d'Orléans, who had given money and bread to the people during the winter, would be popularly acclaimed by the crowd much to her detriment. The Estates General convened the next day. During the month of May, the Estates General began to fracture between the democratic Third Estate (consisting of the bourgeoisie and radical nobility), and the royalist nobility of the Second Estate, while the King's brothers began to become more hardline.

Despite these developments, the queen was strongly focused on her son, the dying Dauphin. Attended by his mother, the seven-year old boy succumbed to tuberculosis at Meudon on 4 June, leaving the title of Dauphin to his younger brother, Louis Charles. His death, which would have normally been nationally mourned, was virtually ignored by the French people, who were instead preparing for the next meeting of the Estates General and hoping for a resolution to the bread crisis. As the Third Estate declared itself a National Assembly and took the Tennis Court Oath, and as others listened to rumors that the Queen wished to bathe in their blood, Marie Antoinette went into mourning for her eldest son. Marie Antoinette's role was decisive in urging the King to remain firm and to not concede to popular demands for reforms. In addition, the Queen was ready to use force to crush the revolution.

July 1789–1792: The French Revolution

The situation began to escalate violently in June as the National Assembly began to demand more rights, and Louis XVI began to push back with efforts to suppress the Third Estate. However, the King's ineffectiveness and the Queen's unpopularity undermined the monarchy as an institution, and so these attempts failed. Then, on 11 July, on Marie Antoinette's urging and orders, Necker was dismissed to be replaced by Breteuil, the Queen's choice to crush the Revolution with mercenary Germanic troops. Paris was besieged by riots at the news, which culminated in the storming of the Bastille on 14 July.

In the days and weeks that followed, many of the most conservative, reactionary royalists, including the comte d'Artois and the duchesse de Polignac, fled France for fear of assassination. Marie Antoinette, whose life was the most in danger, stayed behind in order to help the king promote stability, even as his power was gradually being taken away by the National Constituent Assembly, which was now ruling Paris and conscripting men to serve in the Garde Nationale.

By the end of August, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (La Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen), drafted by La Fayette, was adopted, which officially began a constitutional monarchy in France. Despite this, the king was still required to perform certain court ceremonies, even as the situation in Paris worsened due to a bread shortage in September. On 5 October, a mob from Paris descended upon Versailles and forced the royal family, along with the comte de Provence, his wife and Madame Elisabeth, to move to Paris under the watchful eye of the Garde Nationale. The king and queen were installed in the Tuileries Palace under strong surveillance. During this house arrest, Marie Antoinette conveyed to her friends that she did not intend to involve herself any further in French politics, as everything, whether or not she was involved, would inevitably be attributed to her anyway and she feared the repercussions of further involvement.

Despite the situation, Marie Antoinette was still required to perform charitable functions and to attend certain religious ceremonies, which she did. Most of her time, however, was dedicated to her children. Marie Antoinette in spite of her status as an effective state prisoner, played a very important political role in the period extending between 1789 and 1791. That role was not public because there was a political and public rejection of the Queen who tried to crush the revolution in July 1789. During this period, Marie Antoinete had a complex set of relationships with several key leaders of the early period of the French Revolution. One of the most important politicians of that period was Necker the prime minister who was in charge of financial policy, the Queen hated Necker in spite that she played a decisive role in his return to power. Marie Antoinette blamed Necker for the role he played in supporting the Revolution and she was very happy when he was obliged to resign in 1790.

Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette the leader of the National Guard (and military leader in the American Revolution) hated the Queen and served as her jailer and even considered sending her to a convent. However, he was persuaded by the mayor of Paris, Jean Sylvain Bailly, to try to work with her. La Fayette's relation with the King was acceptable and being a liberal aristocrat he did not want the destruction of the monarchy but instead the installation of a liberal system of government. At times La Fayette worked in the Queen's favor. La Fayette sent the Duke of Orleans, who was accused by the Queen of fomenting trouble, into exile for a period of time. La Fayette even boasted, as the Queen's jailer, that he allowed Marie Antoinette to see Axel de Fersen, albeit under strong surveillance. The Queen who did not have any direct political power during that period because the King's powers were suspended until the constitution was adopted. Marie Antoinette strongly resented her status as an effective prisoner who needed the approval of her guards for any physical or public activity.

A significant achievement for Marie Antoinette in that period was the establishment of an alliance with Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau, the most important lawmaker in the assembly. Like La Fayette, Mirabeau was a liberal aristocrat. While Mirabeau was elected on the lower class list, he was not fundamentally against the monarchy and dreamed of reconciling the monarchy with the revolution. Mirabeau wanted also to be a minister and he was not immune to corruption. On the advice of Count Mercy, Marie Antoinette opened secret negotiations with Mirabeau and they agreed to meet in secret in the castle of Saint Cloud in the summer of 1790. At the meeting Mirabeau was much impressed by the Queen declaring she was the only man in her husband court, a deal was reached turning Mirabeau into one of her political allies. Marie Antoinette also accepted to pay Mirabeau 6000 livres per month and many millions if he succeeded in his mission to restore the King's authority.

The summer of 1790 brought to Marie Antoinette and her family a limited amount of relief, as they were allowed to spend it in the castle of Saint Cloud, which belonged to the Queen. While her situation as a prisoner did not change, she had much greater personal freedom than in Paris, since she was free from the radical elements who surrounded her and followed all her movements in the capital. During this time, she met Mirabeau in secret, an event which could not have happened in Paris.

The only time the royal couple returned to Paris in that period was in 14 July 1790 for the official celebration of the Fall of the Bastille, "The Fete de la Federation". The Abbe Talleyrand said a commemorative Mass in Paris and at least 300,000 persons participated from all over France including 18,000 National Guards. At the event, the King was greeted with numerous cries of "Long Live The King ", especially when he took the oath to protect the Nation and to apply the laws voted by the Constitutional Assembly. There were even some cheers to the Queen, particularly when she presented her son to the Public. Mirabeau advised Marie Antoinette to leave Paris and to travel inside France to profit from the commemoration of the 14 of July, but the Queen was already thinking of leaving France and turning for Foreign Powers to help her crush the Revolution.

Mirabeau sincerely wanted to reconcile the Queen with the people but the Queen was still attempting to restore as much of the King's authority as possible and to liberate herself from her captivity. Marie Antoinette was happy to see Mirabeau restoring much of the King's powers in the assembly, such as the King's authority over foreign policy was restored. The right to propose the declaration of war was also given to the King. Over the objections of La Fayette and his allies, the King was given a suspensive veto allowing him to veto any laws for a period of four years. With time Mirabeau would support the Queen even more, going as far to agree with her escape plans but perhaps not to the extent of demanding the help of foreign powers. However, this leverage with the Assembly ended with the death of Mirabeau in April 1791, though many moderate leaders of the French Revolution tried to contact the Queen and to establish some kind of cooperation with her.

Just before Mirabeau's death, the Pope condemned the civil constitution of the clergy in March 1791, which reduced the number of bishops from 132 to 93, imposed the election of bishops and monks by the French people and finally reduced the Pope's authority over the Church. Marie Antoinette was raised in the Catholic Faith and while she was not pious as her husband, religion played a decisive role in her life specially after her pregnancies. The Queen's political ideas and her belief in the absolute power of monarchs were based on the simple assumption that Queens and Kings were the representatives of God on earth and that their subjects should obey them in an absolute way. When the people in Paris felt that the Queen was against the new religious laws, Marie Antoinette was publicly insulted and she was not allowed to leave Paris. This incident fortified the Queen's determination to leave Paris.

Despite her attempts to remain out of the public eye, she was falsely accused in the libelles of conducting an affair with the commander of the Garde Nationale, the marquis de La Fayette, who in reality she loathed for his liberal tendencies and his role in the royal family's forced departure from Versailles. This was not the only accusation Marie Antoinette faced from such "libelles." In such pamphlets as "Le Godmiché Royal" (translated, "The Royal Dildo"), it was suggested that she routinely engaged in deviant sexual acts of various sorts, most famously with the English Baroness 'Lady Sophie Farrell' of Bournemouth, a renowned lesbian of the time. From acting as a tribade (in her case, in the lesbian sense), to sleeping with her son, Marie Antoinette was constantly an object of rumor and false accusations of committing sexual acts with partners other than the king. Later, allegations of this sort (from incest to orgiastic excesses) were used to justify her execution. Ultimately, none of the charges of sexual depravity has any credible evidentiary support; Marie Antoinette was simply an easy target for rumor and criticism.

Marie Antoinette at that period of time had in general very good relations with her husband, who was passing by a depression phase and who was letting her take all the major political and personnel decisions affecting their lives. Marie Antoinette's priority in the spring of 1791 was to escape her captivity but with her family; she refused to be separated from her children and especially from her husband. Even Fersen could not convince her to leave without the King; the Queen wanted the King to come with her both because she loved the King, the father of her children and because she was aware that without the King she would lose all her political powers. Marie Antoinette asked and ordered Fersen and Breteuil (who represented her in the courts of Europe) to prepare an escape plan while she continued her negotiations with some moderate leaders of the French Revolution.

During this time, there were many plots designed to help members of the royal family escape. The queen rejected several because she would not leave without the king. Other opportunities to rescue the family were ultimately frittered away by the indecisive king. Once the king finally did commit to a plan, his indecision played an important role in its poor execution and ultimate failure. In an elaborate attempt to escape from Paris to the royalist stronghold of Montmédy planned by Count Axel von Fersen and the baron de Breteuil, some members of the royal family were to pose as the servants of a wealthy Russian baroness. Initially, the Queen rejected the plan because it required her to leave with only her son, as she wished the rest of the royal family to accompany her. The King wasted time deciding upon which members of the family should be included in the venture, what the departure date should be, and the exact path of the route to be used. After many delays, the escape ultimately occurred on 21 June 1791 but the entire family was captured twenty-four hours later at Varennes and taken back to Paris within a week. The escape attempt destroyed much of the remaining support of the populace for the King

When the Queen was captured with her family, the assembly sent three representatives to escort the royal family back to Paris. Marie Antoinette was humiliated by the people as never before, she was beaten and pushed by the crowds, people spat on her and her hands were put forcefully behind her back under the excuse of escorting her. Antoine Barnave, the representative of the moderate party in the constitutional assembly, protected the Queen from the crowds at the peril of his own life. Even Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve, the representative of the Girondin radical republican party of Madame Roland, took pity on the royal family. Marie Antoinette was brought safely to Paris, in addition, thanks to Barnave, she was not brought to trial and publicly exonerated of any crimes in relation with her attempt of escape.

Using her connection with the moderate leader Barnave, Marie Antoinette played a leading but indirect role in the establishment of the French Constitution of 1791. In its details, the constitution of 1791 was a compromise between the ideas of the Old Regime and the ideals of the French Revolution. It was not directed against the King but certainly against the old nobility. This constitution called for the establishment of a constitutional monarchy where the King was given important but not full powers. The King was given substantial powers according to the articles of the Constitution. Executive power was under the control of the King, who was also the head the army, in charge of foreign policy and chose ministers. While the king could not declare war, the new Legislative Assembly, which replaced the previous Constituent Assembly on 1 October, could only go to war if requested to do so by the King. The King was also considered to have immunity for actions he might take as a monarch, but this did not extend to other members of his family. An English visitor in the Tuileries gardens would witness two soldiers observing and guarding the queen keeping their hats in her presence while singing disgusting songs, on the grounds that there was no mention of her in the Constitution. Finally, the king was given the right to veto any law for four years. The King, who was considered the head of state, was given a budget of 25 millions livres every year in order to allow him to pay the functions of his court.

As her letters show, the Queen was incompletely sincere in this cooperation with the moderate leaders of the French Revolution, which ultimately ended any chance to establish a moderate government in France., as it led to a further decline in the popularity of both the King and Queen. The view that the unpopular Queen was controlling king further degraded their standing with the people. The Jacobin Party successfully exploited the failed escape to advance its radical agenda. Its members called for the end to any type of monarchy in France.

The constitution called for a moderate system of government. Barnave, who believed in the sincerity of the Queen, took great political risks in the hope of producing a stable social and political structure. Barnave established a system of voting that was based on the middle class vote. In addition, the civil constitution of the clergy, which greatly displeased Marie Antoinette because it created a national church outside the influence of the Papacy, was not considered a constitutional act. Barnave was able to secure a moderate majority who was ready to work with the Queen in spite of her unpopularity. This situation lasted a few months until the spring of 1792.

During this time, Queen was a prisoner guarded night and day by many soldiers who never left her for a moment, even in her bedroom. Many of these jailers were radicals who openly disrespected her, smoking in her face, denying her any privacy and maximally restricting her movements. Marie Antoinette was never allowed to visit her palace of Saint Cloud and was required to seek her guards' permission to see her children or husband, who sometimes refused her request. If permission was granted to leave her rooms, she was escorted by soldiers who surrounded her from all sides and who were present in all her meetings. This was despite the fact that she and her husband were still legally ruling sovereigns. Despite the many difficulties imposed by their situation, the health of Marie Antoinette was acceptable in early 1792. It was true that all pictures and sketches of the period showed Marie Antoinette as a grossly overweight woman with a double chin. However, over the course of her strict captivity, poor spirits and restrictions on her social life, the health of Marie Antoinette began to deteriorate rapidly. The hair of the Queen turned at least partially white and she began to lose a lot of blood. Despite this, she remained a big corpulent beauty with a double chin and great charm, but she developed problems in at least one of her legs, which necessitated assistance when walking and further reduced her activities.

In February 1792 Ferson was able to see the Queen a final time in spite of the strong measures of restriction around the prisoner Queen. Beyond doubt Fersen bribed some of the guards, but was not able to pass more than a short period of time in the palace where the Queen was effectively imprisoned. Marie Antoinette would acknowledge that the security measures were so strong that it was impossible to escape with barred windows in her rooms and an escort of soldiers following her days and nights dictating her every move.

Barnave advised the Queen to recall the Austrian ambassador Count Mercy, who played such a huge part in her life, in addition to the Princess de Lamballe. Count Mercy, who was appointed in a high position in the Austrian Empire, refused to return for a variety of reasons. This saddened the Queen greatly, leaving the impression that she was left to her demise, especially that Mercy was a paternal figure for her sent by her mother to take care of her since her coming to France. She was more lucky with the Princess de Lamballe, who returned and filled a great void in the affective and social life of the captive Queen. As for her social life, it was difficult for the Queen who was effectively a prisoner guarded night and day to have an effective social life; wherever Marie Antoinette went there was a soldier before her and one after her, it was only in the night that she was partially free, but she was obliged to keep the door of her bedroom open so that she can be seen by her guards, who did not always respect her.

Marie Antoinette hoped that the armies sent by the rulers of Europe would be able to crush the Revolution even at the cost was the blood of her own people. The Queen particularly counted on the support of her Austrian family. After her brother Joseph died in 1790. Léopold was ready to support Marie Antoinette but only to a limited degree. Her nephew Francis, who succeeded his father Leopold in 1792, was a very conservative ruler who was ready to support Marie Antoinette because he hated and feared the French Revolution. When the Queen asked him to declare war on France, he accepted out of monarchical solidarity and because he wanted to establish Austrian influence over Western Europe. To be fair to Marie Antoinette, she was not the only person who wanted war, as many radical leaders of the French Revolution also wanted war for their own reasons. The Jacobin party himself was slip into two factions, the radicals under the leadership of Robespierre did not want to participate in the war fearing a union of the Monarchies against them. The Moderate Jacobins or Girondins as they were called under the leadership of Madame Roland and Brissot were for the war because they wanted to spread the ideals of the French Revolution all over Europe and they also believed that a war would unite the French People against their internal and external enemies. While the role of Madame Roland was the most important as de facto-leader of the Girondins, Brissot who was the leader of the foreign comity in the National Assembly played a key role in the drafting of the war resolution. Yet according to the simple facts and description of events the most important actor remained the Queen because according to the constitution only the King could propose to the Assembly to declare war. The facts speak for themselves, not only did the Queen pushed Austria to declare War as we know from her letters, she also pushed her husband to propose the declaration of war to the National Assembly.--

However, as the result of Leopold's aggressive tendencies, and those of his son Francis II on the Queen's behalf, who succeeded him in March, it was that France declared war on Austria on 20 April 1792. This caused the queen to be viewed as an enemy, even though she was personally against Austrian claims on French lands. That summer, the situation was compounded by multiple defeats of French armies by the Austrians, in part because Marie Antoinette betrayed her country's military secrets to the foreign powers. In addition, the King on the orders of the Queen vetoed several measures that would have restricted his power even further. During this time, due to his political activities, Louis received the nickname "Monsieur Veto"—and the name "Madame Veto" was likewise subsequently bequeathed on Marie Antoinette. These names were then prominently featured in different contexts, including La Carmagnole.

Up until the deposition of the royal family in August 1792 and his own fall from grace, Barnave remained the most important advisor and supporter of the Queen inside France. Marie Antoinette was ready to work with Barnave as long as he was ready to follow her orders, which Barnave did to a large extent and over a long period of time. Goaded by the queen, Barnave convinced La Fayette to use force against the radical elements of the French Revolution, and as a result ten of thousands of political opponents of Marie Antoinette were either killed, exiled or sent to prisons. Rather than to cooperate with La Fayette, Marie Antoinette refused to be helped by him and played a decisive role in defeating him in his aims to become the mayor of Paris in October 1791. Barnave and the moderates were around 260 lawmakers in the new Legislative Assembly, the radicals were around 136 and the rest (around 350) were in the middle. At first the majority was with Barnave, but the Queen's policy led to the radicalization of the assembly and the moderates lost control of the legislative process. The moderate government collapsed in April 1792 and a radical ministry headed by the Girondins was formed. Worse than that the assembly passed a series of laws concerning the Church, the aristocracy and the formation of new national guard units which were vetoed by the King on the orders of the Queen.

The laws were not very radical by themselves except perhaps in relation to the Church, pragmatism should have led the Queen to accept the new laws even on a temporary basis in order to conciliate the fury of the people. Instead Marie Antoinette continued her plots with the foreign powers by pushing them to issue the Declaration of Pillnitz in August 1791, which threatened invasion of France. This led in turn to a French declaration of war in April 1792 and the Campaigns of 1792 in the French Revolutionary War and the popular revolution of August 1792 which ended the monarchy.

On 20 June, "a mob of terrifying aspect" broke into the Tuileries and made the king wear the bonnet rouge (red Phrygian cap) to show his loyalty to France.

The vulnerability of the king was exposed on 10 August when an armed mob, on the verge of forcing its way into the Tuileries Palace, forced the king and the royal family to seek refuge at the Legislative Assembly. An hour and a half later, the palace was invaded by the mob who massacred the Swiss Guards. On 13 August, the royal family was imprisoned in the tower of the Temple in the Marais under conditions considerably harsher than their previous confinement in the Tuileries.

A week later, many of the royal family's attendants, among them the princesse de Lamballe, were taken in for interrogation by the Paris Commune. Transferred to the La Force prison, the princesse de Lamballe was a victim of the September Massacres, killed on 3 September. Her head was affixed on a pike and marched through the city. Although Marie Antoinette did not see the head of her friend as it was paraded outside her prison window, she fainted upon learning about the gruesome end that had befallen her faithful companion.

On 21 September, the fall of the monarchy was officially declared, and the National Convention became the legal authority of France. The royal family was re-styled as the non-royal "Capets". Preparations for the trial of the king in a court of law began.

Charged with undermining the First French Republic, Louis was separated from his family and tried in December. He was found guilty by the Convention, led by the Jacobins who rejected the idea of keeping him as a hostage. A month later he was condemned to execution by guillotine.

1793: "Widow Capet", trial, and execution

Louis was executed on 21 January 1793. The Queen, now called the "Widow Capet", plunged into deep mourning and refused to eat or do any exercise. There is no documentation of her proclaiming her son as Louis XVII; however, the comte de Provence, in exile, recognised his nephew as the new king of France and took the title of Regent. Marie-Antoinette's health rapidly deteriorated in the following months, due to tuberculosis and possibly uterine cancer and frequent hemorrhages.

Despite her condition, the debate as to her fate was the central question of the National Convention after Louis' death. While some continually advocated her death, others proposed exchanging her for French prisoners of war or for a ransom from the Holy Roman Emperor. Thomas Paine advocated exile to America. Starting in April, however, a Committee of Public Safety was formed, and men such as Jacques Hébert were beginning to call for Antoinette's trial; by the end of May, the Girondins had been chased out of power and arrested. Other calls were made to "retrain" the Dauphin, to make him more pliant to revolutionary ideas. To carry this out, the eight-year-old Louis Charles was separated from Antoinette on 3 July and given to the care of a cobbler. On 1 August, she herself was taken out of the Tower and entered into the Conciergerie as Prisoner No. 280. Despite various attempts to get her out, such as the Carnation Plot in September, Marie Antoinette refused when the plots for her escape were brought to her attention. While in the Conciergerie, she was attended by her last servant, Rosalie Lamorlière.

She was finally tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal on 14 October. Unlike the King, who had been given time to prepare a defence, the queen was given less than one day. Among the things she was accused of, many originating as rumors in the libelles, were orchestrating orgies in Versailles, sending millions of livres of treasury money to Austria, plotting to kill the Duke of Orléans, incest with her son, declaring her son to be the new king of France, and orchestrating the massacre of the Swiss Guards in 1792.

The most infamous charge was that she sexually abused her son. In this she was accused by Louis Charles, who had been coached by Hébert and his guardian. After being reminded that she had not answered the charge of incest, Marie Antoinette protested emotionally to the accusation, and the women present in the courtroom, including market women who had stormed the palace for her entrails in 1789, even began to support her. She had been composed throughout the trial until this accusation was made, to which she finally answered, "If I have not replied, it is because Nature itself refuses to respond to such a charge laid against a mother."

The outcome of the trial had been decided in advance by the Committee of Public Safety around the time the Carnation Plot was uncovered, and after two days of proceedings, in the early morning of 16 October, she was declared guilty of treason. Back in her cell she composed a letter to her sister-in-law Madame Élisabeth, affirming her clear conscience, her Catholic faith and her feelings for her children. The letter did not reach Élisabeth.

On the same day Marie Antoinette was forced to undress before her guards and clad in a plain white dress. Her hair was cut off, her hands were bound tightly behind her back and leashed with a rope, she was driven through Paris in an open cart. She maintained her composure, forcing even the respect of her enemies. For her final confession she was given a priest recognized not by Rome but by the local constitutional church in France. Her last picture, by the painter Jacques-Louis David, depicts a bound woman who (according to biographer Antonia Fraser) has lost much of her beauty but maintains an air of dignity. Marie Antoinette had sufficient determination to die (in her view) as a martyred Queen. At 12:15 p.m. 16 October 1793, two and a half weeks before her thirty-eighth birthday, Marie Antoinette was beheaded at the Place de la Révolution (present-day Place de la Concorde). Her last words were "Pardon me sir, I meant not to do it", to Henri Sanson the executioner, whose foot she had accidentally stepped on after climbing the scaffold. Her body was thrown into an unmarked grave in the Madeleine cemetery, rue d'Anjou (which was closed the following year).

Her sister-in-law Élisabeth was executed in 1794 and her son died in prison in 1795. Her daughter returned to Austria in a prisoner exchange, married and died childless in 1851.

Both Marie Antoinette's body and that of Louis XVI were exhumed on 18 January 1815, during the Bourbon Restoration, when the comte de Provence had become King Louis XVIII. Christian burial of the royal remains took place three days later, on 21 January, in the necropolis of French Kings at the Basilica of St Denis.

In popular culture

Main article: Marie Antoinette in popular cultureThe phrase "Let them eat cake" is often attributed to Marie Antoinette, but there is no evidence she ever uttered it, and it is now generally regarded as a "journalistic cliché". It may have been a rumor started by angry French peasants as a form of libel. This phrase originally appeared in Book VI of the first part (finished in 1767, published in 1782) of Rousseau's putative autobiographical work, Les Confessions.

Enfin je me rappelai le pis-aller d’une grande princesse à qui l’on disait que les paysans n’avaient pas de pain, et qui répondit : Qu’ils mangent de la brioche.

Finally I recalled the stopgap solution of a great princess who was told that the peasants had no bread, and who responded: "Let them eat brioche."

Apart from the fact that Rousseau ascribes these words to an unknown princess—vaguely referred to as a "great princess", there is some level of thought that he invented it altogether, seeing as Confessions was, on the whole, a rather inaccurate autobiography.

In America, expressions of gratitude to France for its help in the American Revolution included the naming of the city of Marietta, Ohio, founded in 1788. The Ohio Company of Associates chose the name Marietta after an affectionate nickname for Marie Antoinette.

Marie Antoinette is referenced in the lyrics of the song "Killer Queen" by the rock band Queen.

Titles from birth to death

- 2 November 1755 – 19 April 1770: Her Royal Highness Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria

- 19 April 1770 – 10 May 1774: Her Royal Highness The Dauphine of France

- 10 May 1774 – 1 October 1791: Her Most Christian Majesty The Queen of France and Navarre

- 1 October 1791 – 21 September 1792: Her Most Christian Majesty The Queen of the French

- 21 September 1792 – 21 January 1793: Madame Capet

- 21 January 1793 – 16 October 1793: La Veuve ("the widow") Capet

Ancestry

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Lever 2006, p. 1

- C. f. "it is both impolitic and immoral for palaces to belong to a Queen of France" (part of a speech by a councilor in the Parlement de Paris, early 1785, after Louis XVI bought St Cloud chateau for the personal use of Marie Antoinette), quoted in Castelot 1957, p. 233

- C.f. the following quote: "she (Marie Antoinette) thus obtained promises from Louis XVI which were in contradiction with the Council's (of Louis XVI's ministers) decisions", quoted in Castelot 1957, p. 186

- "Marie Antoinette Biography". Chevroncars.com. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Jefferson, Thomas. Autobiography of Thomas Jefferson. Courier Dover Publications. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

I have ever believed that had there been no queen, there would have been no revolution.

- "A Reputation in Shreds - Marie Antoinette Online". Marie-antoinette.org. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- "Marie Antoinette". Antonia Fraser. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Konigsberg, Eric (22 October 2006). "Marie Antoinette, Citoyenne". NYTimes.com. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Fraser 2002, p. 5

- Fraser 2001, p. 3

- ^ Cronin 1989, p. 45

- Lever 2006, p. 7

- Lever 2006, p. 10

- France Loisirs, Michel de Decker, 2005, p.16

- Fraser 2002, pp. 32–33

- France Loisirs, Michel de Decker, 2005, p.17

- Cronin 1989, p. 46

- ^ Weber 2007

- Fraser 2001, pp. 166–170

- Fraser 2001, p. 22

- ^ Cronin 1974, p. 46 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Fraser 2001, p. 23

- Fraser 2001, p. 25

- Fraser 2001, pp. 42–50

- Fraser 2001, pp. 51–53

- Fraser 2001, pp. 58–62

- Fraser 2001, pp. 64–69

- Fraser 2001, pp. 70–71

- Cronin 1974, pp. 49–50 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Fraser 2001, p. 157

- Fraser 2001, p. 47

- Fraser 2001, pp. 94, 130–31

- Cronin 1974, pp. 61–63 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Cronin 1974, p. 61 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Lever 2006

- Fraser 2001, pp. 87–90, 97–99

- Fraser 2001, pp. 80–81

- Fraser 2001, p. 141

- Fraser 2001, pp. 129–131

- Fraser 2001, pp. 131–132; Bonnet 1981

- Fraser 2001, pp. 111–113

- Fraser 2001, pp. 113–116

- Fraser 2001, pp. 132–137

- Fraser 2001, pp. 136–137

- Fraser 2001, pp. 124–127

- Fraser 2001, pp. 137–139

- Fraser 2001, pp. 140–145

- Cronin 1974, p. 215 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Fashion, the mirror of history, page 190, Michael Batterberry, Ariane Ruskin Batterberry, Greenwich House, 1977. ISBN 978-0-517-38881-5

- 20,000 years of fashion: the history of costume and personal adornment, page 350, François Boucher, Yvonne Deslandres, H.N. Abrams, 1987. ISBN 978-0-8109-1693-7

- Fraser 2001, pp. 150–151

- A History of the Gardens of Versailles, page 218, Michel Baridon, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8122-4078-8

- Weber 132

- Fraser 2001, p. 152

- Cronin 1974, pp. 158–159 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Cronin 1974, p. 159 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Fraser 2001, pp. 160–162

- Cronin 1974, pp. 162–164 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Fraser 2001, pp. 164–168

- Cronin 1974, p. 161 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Hibbert 2002, p. 23

- Fraser 2001, pp. 166–170

- Fraser 2001, p. 169

- Fraser 2001, p. 172

- Cronin 1974, pp. 127–128 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Fraser 2001, pp. 174–179

- Fraser 2001, pp. 183–186

- Fraser, 2001 & pp218-220 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp218-220 (help)

- Fraser 2001, pp. 184–187

- Fraser 2001, pp. 187–188

- Fraser 2001, p. 191

- Cronin 1974, p. 190 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Fraser, pp.232-6

- Fraser 2001, pp. 195–198

- Fraser, p. 234-6

- Fraser, p.235-6

- Fraser 2001, pp. 197–198, 199–205

- Cronin 1974, p. 193 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Fraser 2001, pp. 198–201

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 202

- Lever 2006, p. 158

- Fraser, pp. 245-7.

- Cronin 1974, pp. 204–205 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Fraser 2001, p. 208

- Cronin 1974, pp. 133–134 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCronin1974 (help)

- Fraser 2001, pp. 214–215

- Fraser 2001, pp. 216–220

- Fraser 2001, pp. 224–225

- Lever 2006, p. 189

- Stefan Zweig and Antonia Fraser, who believe Fersen and the Queen were romantically involved with one another, argue that there is no evidence whatsoever to suggest that Louis XVI was not the child's father - see Stefan Zweig, Marie Antoinette: The portrait of an average woman (New York, 1933), pp. 143, 244-7, and Fraser, pp. 267-9. This is also the view taken in biographies like Ian Dunlop, Marie-Antoinette: A Portrait (London, 1993), Évelyne Lever, Marie-Antoinette : la dernière reine (Paris, 2000), Simone Bertière, Marie-Antoinette: l'insoumise (Paris, 2003), and Jonathan Beckman, How to ruin a Queen: Marie Antoinette, the Stolen Diamonds and the Scandal that shook the French throne (London, 2014), all of which argue that the Queen was not romantically or sexually involved with von Fersen. Beckman argues that 'there was speculation that he had an affair with the Queen. To keep such a liaison hidden for years would have required a talent for logistics and discretion well beyond Marie Antoinette.' Munro Price, The Fall of the French Monarchy: Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette and the baron de Breteuil (London, 2002) argues that it is impossible to know one way or the other how the Queen and von Fersen felt about one another, but that if they ever did consummate their union, it took place after the birth of all four of her children and quite possibly only in the final few weeks of her freedom. The prince's biographer, Deborah Cadbury, in The Lost King of France: The tragic story of Marie-Antoinette's Favourite Son (London, 2003), pp. 22-4 also argues strongly that Louis XVI was the younger son's biological father.

- Cadbury, p. 23

- Fraser 2001, p. 226

- Fraser 2001, pp. 246–248

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 248–250

- Fraser 2001, pp. 248–252

- Fraser 2001, pp. 250–260

- Fraser harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser (help)

- Fraser 2001, pp. 254–255

- Fraser, 2001 & pp254-260 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp254-260 (help)

- Facos, p. 12.

- Schama, p. 221.

- Fraser 2001, pp. 255–258

- Fraser, 2001 & pp 257-258 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp_257-258 (help)

- Fraser 2001, pp. 258–259

- Fraser 2001, pp. 260–261

- Fraser 2001, pp. 263–265

- Fraser 2001, pp. 270–273

- Fraser 2001, pp. 274–278

- Fraser, 2001 & pp279-282 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp279-282 (help)

- Fraser, 2001 & pp280-285 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp280-285 (help)

- Fraser 2001, pp. 282–284

- Fraser 2001, pp. 284–289

- Fraser 2001, p. 289

- Fraser 2001, pp. 298–304

- Fraser 2001, p. 304

- Fraser 2001, pp. 304–308

- Fraser 2001, p. 315

- Fraser, 2001 & pp310-314 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp310-314 (help)

- 2001 & Fraser, pp. 314–316 harvnb error: no target: CITEREF2001Fraser (help)

- Fraser, 2001 & pp315-319 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp315-319 (help)

- Fraser, 2001 & pp321-323 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp321-323 (help)

- Fraser 2001, p. 319

- "Project MUSE — Early American Literature — Charles Brockden Brown's Ormond and Lesbian Possibility in the Early Republic" (PDF). Muse.jhu.edu. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- Bonnie Zimmerman (2000). Lesbian histories and cultures: an encyclopedia (Volume 1). Taylor & Francis. pp. 776–777. ISBN 9780815319207. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- Dena Goodman (2003). Marie-Antoinette: writings on the body of a queen. Psychology Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 9780415933957. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Fraser, 2001 & pp321-325 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp321-325 (help)

- Fraser 2001, pp. 325–348

- Fraser 2001, pp. 355–356

- Fraser 2001, pp. 353–354

- Fraser 2001, pp. 350–352

- Fraser, 2001 & pp357-358 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp357-358 (help)

- Fraser, 2001 & pp358-365 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp358-365 (help)

- Fraser 2001, pp. 360–363

- Fraser 2001, p. 364-365

- 2001 & pp365-368 harvnb error: no target: CITEREF2001pp365-368 (help)

- Fraser 2001, pp. 365–368

- Fraser 2001, pp. 350, 360–371

- Fraser, 2001 & pp371-373 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp371-373 (help)

- Fraser 2001, p. 368

- Fraser 2001, pp. 373–379

- Fraser 2001, pp. 382–386

- Fraser 2001, p. 389

- Fraser 2001, p. 392

- Fraser 2001, pp. 395–398

- Fraser 2001, p. 399

- Fraser 2001, pp. 404–405, 408

- Fraser 2001, pp. 398, 408

- Fraser 2001, pp. 411–412

- Fraser 2001, pp. 412–414

- Fraser 2001, pp. 414–415

- Fraser 2001, p. 418

- Fraser 2001, pp. 429–435

- Fraser 2001, pp. 424–425, 436

- "Last Letter of Marie-Antoinette", Tea at Trianon, 26 May 2007

- Fraser, 2001 & p256 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001p256 (help)

- Fraser, 2001 & pp 436-440 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFFraser2001pp_436-440 (help)

- Fraser 2001, p. 440

- The Times 23 October 1793, The Times.

- Richard Covington (November 2006), "Marie Antoinette", Smithsonian magazine

- Fraser 2001, pp. 411, 447

- Fraser 2001, pp. xviii, 160; Lever 2006, pp. 63–5; Lanser 2003, pp. 273–290

- Johnson 1990, p. 17

- Sturtevant, pp. 14, 72.

Bibliography

- Bonnet, Marie-Jo (1981). Un choix sans équivoque: recherches historiques sur les relations amoureuses entre les femmes, XVIe-XXe siècle (in French). Paris: Denoël. OCLC 163483785.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Castelot, André (1957). Queen of France: a biography of Marie Antoinette. trans. Denise Folliot. New York: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 301479745.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cronin, Vincent (1989). Louis and Antoinette. London: The Harvill Press. ISBN 978-0-00-272021-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dams, Bernd H.; Zega, Andrew (1995). La folie de bâtir: pavillons d'agrément et folies sous l'Ancien Régime. trans. Alexia Walker. Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-201858-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Facos, Michelle (2011). An Introduction to Nineteenth-Century Art. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-84071-5. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- Fraser, Antonia (2001). Marie Antoinette (1st ed.). New York: N.A. Talese/Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-48948-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fraser, Antonia (2002). Marie Antoinette: The Journey (2nd ed.). Garden City: Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0-385-48949-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hermann, Eleanor (2006). Sex With The Queen. Harper/Morrow. ISBN 0-06-084673-9.

- Hibbert, Christopher (2002). The Days of the French Revolution. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-688-16978-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Johnson, Paul (1990). Intellectuals. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-091657-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lanser, Susan S. (2003). "Eating Cake: The (Ab)uses of Marie-Antoinette". In Goodman, Dena (ed.). Marie-Antoinette: Writings on the Body of a Queen. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-93395-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lever, Évelyne (2006). Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France. London: Portrait. ISBN 978-0-7499-5084-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schama, Simon (1989). Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York: Vintage. ISBN 0-679-72610-1.

- Seulliet, Philippe (July 2008). "Swan Song: Music Pavillion of the Last Queen of France". World Of Interiors (7).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sturtevant, Lynne (2011). A Guide to Historic Marietta, Ohio. The History Press. ISBN 978-1-60949-276-2. Retrieved 1 September 2011.