| Revision as of 10:17, 12 December 2017 editKolbertBot (talk | contribs)Bots1,166,042 editsm Bot: HTTP→HTTPS (v478)← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:47, 13 February 2018 edit undoAgricolae (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers31,009 edits begin cleanupTag: use of predatory open access journalNext edit → | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| '''Citrus taxonomy''' refers to the ] of the ], ], ], and ] within the ] '']'', subgenus ], and related genera, found in cultivation and in the wild. | '''Citrus taxonomy''' refers to the ] of the ], ], ], and ] within the ] '']'', subgenus ], and related genera, found in cultivation and in the wild. | ||

| Citrus taxonomy is complex.<ref name=Moore>{{cite journal |pmid=11525837 |title=Oranges and lemons: clues to the taxonomy of ''Citrus'' from molecular markers |author=G. A. Moore | volume=17 |date=Sep 2001 |journal=Trends |

Citrus taxonomy is complex.<ref name=Moore>{{cite journal |pmid=11525837 |title=Oranges and lemons: clues to the taxonomy of ''Citrus'' from molecular markers |author=G. A. Moore | volume=17 |date=Sep 2001 |journal=Trends in Genetics |pages=536–40 |doi=10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02442-8}}</ref> Cultivated citrus are derived from various citrus species found in the wild. Some are only selections of the original wild types, while others are ] between two or more ancestors. Citrus plants hybridize easily between species with completely different morphologies, and similar-looking citrus fruits may have quite different ancestries.<ref>{{cite journal|url=http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v32/n7/full/nbt.2954.html | title=A genealogy of the citrus family | last1=Velasco | first1=Riccardo | last2=Licciardello | first2=Concetta |journal=Nature Biotechnology | year=2014 | volume=32 | pages=640-642 }}</ref><ref name=Wu/> Conversely, different-looking varieties may be nearly genetically identical, and differ only by a ].<ref>{{cite journal| url=http://hortsci.ashspublications.org/content/40/7/1963.full.pdf+html | title=The Search for the Authentic Citron (''Citrus medicus'' L.): Historic and Genetic Analysis | last1=Nicolosi | first1=Elisabetta | last2=La Malfi | first2=Stefano | last3=El-Otmani | first3=Mohamed | last4=Neghi | first4=Moshe | last5=Goldschmidt | first5=Eliezer E | journal=HortSciece | volume = 40 | pages=1963-1968 | year=2005}}</ref> | ||

| </ref><ref name=Wu/> Conversely, different-looking varieties may be nearly genetically identical, and differ only by a ].<ref>http://hortsci.ashspublications.org/content/40/7/1963.full.pdf+html</ref> | |||

| Detailed genomic analysis of wild and domesticated citrus cultivars has suggested that the progenitor of modern citrus species expanded out of the Himalayan foothills in a rapid radiation that has produced at least 10 wild species in South and East Asia and Australia. Most commercial cultivars are the product of hybridization among these wild species, with most coming from crosses involving ]s, ]s and ]s.<ref name="Talon">{{cite journal|title=Genomics of the origin and evolution of ''Citrus'' | last1=Wu | first1=Guohong Albert | last2=Terol | first2=Javier | last3=Ibanez | first3=Victoria | last4=López-García | first4=Antonio | last5=Pérez-Román | first5=Estela | last6=Borredá | first6=Carles | last7=Domingo | first7=Concha | last8=Tadeo | first8=Francisco R | last9=Carbonell-Caballero | first9=Jose | last10=Alonso | first10=Roberto | last11=Curk | first11=Franck | last12=Du | first12=Dongliang | last13=Ollitrault | first13=Patrick | last14=Roose | first14=Mikeal L. Roose | last15=Dopazo | first15=Joaquin | last16=Gmitter Jr | first16=Frederick G. | last17=Rokhsar | first17=Daniel | last18=Talon | first18=Manuel | journal=Nature | year = 2018 | doi=10.1038/nature25447}}</ref> Many different phylogenies for the non-hybrid citrus have been proposed,<ref name="AGLthesis"/> and the phylogeny based on their nuclear genome does not match that derived from their mitochondrial DNA, probably a consequence of the rapid initial divergence.<ref name="Talon"/> Taxonomic terminology is not yet settled. | |||

| ⚫ | Most hybrids express different ancestral traits when planted from seeds (]s) and can continue a ] lineage only through ]. Others do reproduce ] via ] seeds in a process called ].<ref name=Wu>{{cite journal |url=http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v32/n7/full/nbt.2906.html |title=Sequencing of diverse mandarin, |

||

| ⚫ | Most hybrids express different ancestral traits when planted from seeds (]s) and can continue a ] lineage only through ]. Others do reproduce ] via ] seeds in a process called ].<ref name=Wu>{{cite journal |url=http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v32/n7/full/nbt.2906.html |title=Sequencing of diverse mandarin, pomelo and orange genomes reveals complex history of admixture during citrus domestication |journal=Nature |author=G Albert Wu|display-authors=etal |volume=32 |doi=10.1038/nbt.2906 |pages=656–662 |pmid=24908277 |pmc=4113729}}</ref> Some differ only in disease resistance.<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://journal.ashspublications.org/content/135/4/341.full |title=The Origin of Cultivated Citrus as Inferred from Internal Transcribed Spacer and Chloroplast DNA Sequence and Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism Fingerprints|last1=Li | first1=Xiaomeng | last2=Xie | first2=Rangjin | last3=Lu | first3=Zhenhua | last4=Zhou | first4=Zhiqin | journal=Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science | volume=135 | pages=341-350| year=2010 }}</ref> Clear genetic lineages are very important for breeding improved cultivars.<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.oalib.com/paper/285554#.VV320_lViko|title=Genetic Diversity Assessment of Acid Lime (''Citrus aurantifolia'' Swingle) Landraces in Nepal, Using SSR Markers j| last1=Shrestha | first1=Ram Lal | last2=Dhakal | first2=Durga Datta | last3=Gautum |first3=Durga Mani | last4=Paudyal | first4=Krishna Prasad | last5=Shrestha | first5=Sangita | journal= American Journal of Plant Sciences | volume = 3 | pages = 1674-1681 | year=2012 |doi=10.4236/ajps.2012.312204}}</ref> | ||

| Clear genetic lineages are very important for breeding improved cultivars.<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.oalib.com/paper/285554#.VV320_lViko|title=Genetic Diversity Assessment of Acid Lime (''Citrus aurantifolia'' Swingle) Landraces in Nepal, Using SSR Markers - Open Access Library|work=oalib.com}}</ref> Only ], and both are hybrids (]s and ]). Many different phylogenies for the non-hybrid citrus have been proposed,<ref name="AGLthesis"/><ref name="dx.doi.org">{{cite journal |title=Assessing genetic diversity and population structure in a citrus germplasm collection utilizing simple sequence repeat markers (SSRs) |doi=10.1007/s00122-006-0255-9 | volume=112 | journal=Theoretical and Applied Genetics |pages=1519–1531 |pmid=16699791 |vauthors=Barkley NA, Roose ML, Krueger RR, Federici CT }}</ref><ref name="dx.doi.org"/> and taxonomic terminology is not yet settled. | |||

| ==Genetic history== | ==Genetic history== | ||

| All of the wild 'pure' citrus species trace to a common ancestor that lived in the Himalayan foothills, where a late-] citrus fossil, ''Citrus linczangensis'', has been found. At that time, a lessening of the ]s and resultant drier climate in the region allowed the citrus ancestor to expand across south and east Asia in a rapid genetic radiation. After the plant crossed the ] a second radiation took place in the early ] (about 4 million years ago) to give rise to the Australian species. Using ] in order to distinguish pure species cultivars from hybrids, a recent genetic analysis by Wu, ''et al.'' revealed that most modern cultivars are actually hybrids, with the study identifying just ten species of citrus among those studied, seven in Asia and three in Australia. These are the pumello (''Citrus maxima''), the 'pure' mandarins (''C. reticulata'' - most mandarin cultivars were hybrids of this species with pumello), the Mangshan mandarin (''C. mangshanensis''), citrons (''C. medica''), ] (''C. micrantha''), the ] (''C. ichangensis''), and the oval (Nagami) ] (''Fortunella margarita''). In Australia, there were the ] (''C. glauca''), ] (''C. australis'') and the ] (''C. australasica''). Many other cultivars previously identified as species were found to be hybrids,<ref="Talon"/> though not all cultivars were evaluated. | |||

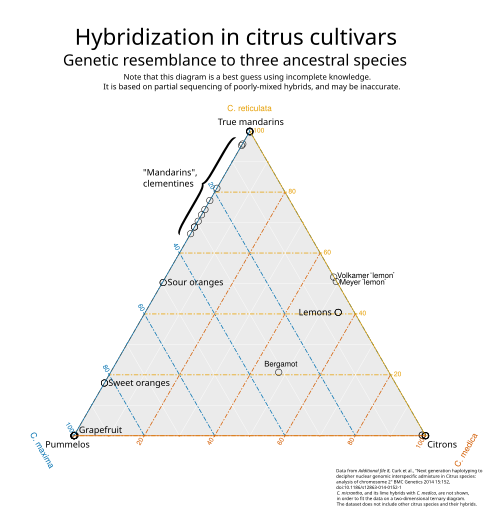

| ] of hybrids of the three major ancestral species.]] | ] of hybrids of the three major ancestral species.]] | ||

| ]'', top right (]). Three-dimensional projection of a ] of ] diversity. | |||

| '']'' (top right) is a ]. | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| - | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| Hybrids are expected to plot between their parents. | |||

| ML: ]; A: ']'; V: ]; M: ]; L: Regular and 'Sweet' ]; B: ]; H: Haploid clementine; C: ]; S: ]; O: ]; G: ].]] | |||

| Interbreeding seems possible between all citrus plants, and between citrus plants and some plants which may or may not be categorized as citrus. The ability of ] to self-pollinate and to reproduce sexually also helps create new varieties. The three predominant ancestral citrus taxa are ] (''C. medica''), ] (''C. maxima''), and ] (''C. reticulata'').<ref name="Talon"/> These taxa interbreed freely, despite being quite genetically distinct, having arisen through ], with citrons evolving in northern ], pomelos in the ], and mandarins in ], ], and ].<ref name="Curk">{{cite journal|url=http://www.dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12863-014-0152-1 | title=Next generation haplotyping to decipher nuclear genomic interspecific admixture in Citrus species: analysis of chromosome 2 | journal=BMC Genetics | volume=15 | page=152 | year=2014 | last1=Curk | first1=Franck | last2=Ancillo | first2=Gema Ancillo | last3=Garcia-Lor | first3=Andres | last4=Luro | first4=François | last5=Perrier | first5=Xavier | last6=Jacquemoud-Collet | first6=Jean-Pierre | last7=Navarro | first7=Luis | last8=Ollitrault | first8=Patrick }}</ref> The hybrids of these taxa include familiar citrus fruits like ], ], ]s, ], and some ]s.<ref name=Moore/><ref></ref><ref> and more</ref> Citrons have also been hybridized with other citrus taxa, for example, crossed with micranta to produce the ].<ref name="Talon"/> In many cases, these crops are propagated ], and lose their characteristic traits if bred. However, some of these hybrids have interbred with one another and with the original taxa, making the citrus family tree a complicated network. | |||

| Interbreeding seems possible between all citrus plants, and between citrus plants and some plants which may or may not be categorized as citrus. The ability of ] to self-pollinate and to reproduce sexually also helps create new varieties. | |||

| ⚫ | The ] and ] do not naturally interbreed with core taxa due to different flowering times,<ref>{{cite journal |title=New universal mitochondrial PCR markers reveal new information on maternal citrus phylogeny |doi=10.1007/s11295-010-0314-x | volume=7 | journal=Tree Genetics |pages=49–61 | last1 = Froelicher | first1 = Yann}}</ref> but hybrids (such as the ] and ]) exist. ]s and '']'' are native to ] and ], so they did not naturally interbreed with the four core taxa; but they have been crossbred with ] and ]s by modern breeders. Humans have deliberately bred new citrus fruits by propagating wild-found seedlings (e.g. ]), creating or selecting mutations of hybrids, (e.g. ]), and crossing different varieties (e.g. 'Australian Sunrise', a ] and ] cross). | ||

| The four core ancestral citrus taxa are ] (''C. medica''), ] (''C. maxima''), ] (''C. reticulata''), and ] (''C. micrantha'').<ref name="biomedcentral.com">{{cite journal |url=http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2156/15/152|title=BMC Genetics - Full text - Next generation haplotyping to decipher nuclear genomic interspecific admixture in Citrus species: analysis of chromosome 2|work=biomedcentral.com}}</ref> | |||

| These taxa all interbreed freely, despite being quite genetically distinct. They probably arose through ], with citrons evolving in northern ], pummelos in the ], and mandarines in ], ], and ].<ref name="biomedcentral.com"/> | |||

| The hybrids of these four taxa include familiar citrus fruits like ], ], ]s, ], and some ]s.<ref name=Moore/><ref></ref><ref> and more</ref> In many cases, these crops are propagated ], and lose their characteristic traits if bred. However, some of these hybrids have interbred with one another and with the original taxa, making the citrus family tree a complicated network. | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| Humans have deliberately bred new citrus fruits by propagating wild-found seedlings (e.g. ]), creating or selecting mutations of hybrids, (e.g. ]), and crossing different varieties (e.g. 'Australian Sunrise', a ] and ] cross). | |||

| Genetic analysis is starting to make sense of this complex phylogeny.<ref name="AGLthesis">{{cite thesis |title=Organización de la diversidad genética de los cítricos |year=2013| author=Andrés García Lor| url=https://riunet.upv.es/bitstream/handle/10251/31518/Versión3.Tesis%20Andrés%20García-Lor.pdf |pages=79 }}{{Es icon}}</ref> ] (] and ]). Partial sequences of other cultivars may give contradictory results, as some citrus hybrids are not at all well-mixed. Many different phylogenies for the non-hybrid citrus have been proposed,<ref name="AGLthesis"/><ref name="dx.doi.org"/><ref name="dx.doi.org"/> and taxonomic terminology is not yet settled. | |||

| ==Citrus naming systems== | ==Citrus naming systems== | ||

| {{See also|Botanical name}} | {{See also|Botanical name}} | ||

| ⚫ | There are two main complete systems of citrus taxonomy, those of ] and ]; however, many citrus types were identified and named by individual taxonomists. The basis of the "Tanaka system" is to provide a separate species name for each cultivar, regardless of whether it is pure or a ] of two or more species or varieties. Tanaka is therefore considered to have been a taxonomic "]".<ref name ="splitter">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tk7DaWYvuPAC&pg=PA30&dq=%22Ty%C3%B4zabur%C3%B4+Tanaka%22&lr=&ei=5avHS6arEIXcygSZq9WrCA&cd=35#v=onepage&q=%22Ty%C3%B4zabur%C3%B4%20Tanaka%22&f=false|page=30|title=Growing Citrus: The Essential Gardener's Guide|first=Martin|last=Page |publisher=Timber Press|year= 2008 |isbn=978-0-88192-906-5}}</ref> The "Swingle system" works differently, in that it first divides the ] '']'' into ], secondly divides it further into ], and lastly divides it again into cultivars or hybrids. The Swingle system is generally followed today with much modification; however, there are still huge differences in nomenclature between countries and even individual scientists.<ref>Iqrar A. Khan, '''' p. 49.</ref><ref></ref> Both systems predate the genomic analysis of Wu, ''et al.''<ref=name "Talon" /> | ||

| Because citrus taxonomy is still understudied{{citation needed|date=January 2016}}, there are many systems of classification that very often contradict each other. There are two main complete systems, that of ] and that of ]; however, many citrus types were identified and named by individual taxonomists. | |||

| ⚫ | The basis of the "Tanaka system" is to provide a separate species name for each cultivar, regardless of whether it is pure or a ] of two or more species or varieties. Tanaka is therefore considered to have been a taxonomic "]".<ref name ="splitter">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tk7DaWYvuPAC&pg=PA30&dq=%22Ty%C3%B4zabur%C3%B4+Tanaka%22&lr=&ei=5avHS6arEIXcygSZq9WrCA&cd=35#v=onepage&q=%22Ty%C3%B4zabur%C3%B4%20Tanaka%22&f=false|page=30|title=Growing Citrus: The Essential Gardener's Guide|first=Martin|last=Page |publisher=Timber Press|year= 2008 |isbn=978-0-88192-906-5}}</ref> | ||

| The "Swingle system" works differently, in that it first divides the ] '']'' into ], secondly divides it further into ], and lastly divides it again into cultivars or hybrids. The Swingle system is generally followed today with much modification; however, there are still huge differences in nomenclature between countries and even individual scientists.<ref>Iqrar A. Khan, '''' p. 49.</ref><ref></ref> | |||

| ==Common name confusions== | ==Common name confusions== | ||

| {{see also|Folk taxonomy}} | {{see also|Folk taxonomy}} | ||

| Most commercial varieties are descended from one or more of ], ], and ]. | Most commercial varieties are descended from one or more of ], ], and ]. The same ]s may be given to different ] or mutations. Fruit with similar ancestry may be quite different in name and traits (e.g. grapefruit, common oranges, and ]s, all pomelo-mandarin hybrids). Note that many traditional citrus groups, such as true sweet oranges and lemons, seem to be ]s, mutant descendants of a single hybrid ancestor.<ref name="Curk" /><ref name="Talon" /> | ||

| The same ]s may be given to different ] or mutations. Fruit with similar ancestry may be quite different in name and traits (e.g. grapefruit, common oranges, and ]s, all pommelo-mandarin hybrids). | |||

| Note that many traditional citrus groups, such as true sweet oranges and lemons, seem to be ]s, mutant descendants of a single hybrid ancestor.<ref name="biomedcentral.com" /> | |||

| ===Ancestral species=== | ===Ancestral species=== | ||

| ====Mandarins==== | ====Mandarins==== | ||

| ''']s''' (tangerines, satsumas) are one of the basic species. Even pure-bred ones are genetically diverse |

''']s''' (tangerines, satsumas) are one of the basic species. Even pure-bred ones are genetically diverse, and many varieties commercially called mandarins are ].<ref name=Wu/><ref></ref>. Wu, ''et al.'', divided mandarins into three classes based on their degree of hybridization. In addition to the genetically-pure mandarins, a second group have arisen as a result of hybridization with pomelos, while a third arose from the crossing of this hybrid with sweet oranges, themselves the product of the back-crossing of hybrid mandarins with pomelos.<ref name="Talon" /> Some are commercial mandarins are hybrids with lemons. | ||

| ====Citrons==== | ====Citrons==== | ||

| ], ] and ], have distinctly different appearances.]] | ], ] and ], have distinctly different appearances.]] | ||

| ]s.]] | ]s.]] | ||

| ⚫ | Many varieties of true (non-hybrid) ] have distinctly different forms. The citron is usually ] by ], and this results in the lowest levels of heterozygosity among the citrus species.<ref name="Talon /> This also means that it will generally be a male parent of any citrus hybrid, rather than a female one. Many ] were proven to be non-hybrids despite their morphological differences;<ref></ref><ref> {{webarchive|url=https://archive.is/20130128201230/http://springerlink.metapress.com/content/nr727lh13q1875pl/fulltext.html |date=2013-01-28 }}</ref><ref></ref><ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080921214001/http://grande.nal.usda.gov/ibids/index.php?mode2=detail&origin=ibids_references&therow=796030 |date=September 21, 2008 }}</ref><ref></ref><ref>.</ref> however, the ] is probably of hybrid origin. | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| In ], ''etrog'' indicates any ] of ], whether or not it is appropriate for Sukkot use. But when etrog is used as an ] term of art, it applies only to those varieties and specimens used as one of the ] in the festival. The various ] use different varieties, according to their traditions or the decisions of their respective ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.citrusvariety.ucr.edu/citrus/ethrog.html|title=ethrog|publisher=University of California, Riverside}}</ref> The ], however, has no relation to the true ] and belongs to the ]. | |||

| ⚫ | Some ] are used in ]s, and some more common varieties are used as the ] in the Jewish harvest festival of ]. There is also a specific variety of citron called ]. The ] has no relation to the true ] and belongs to the ]. | ||

| ⚫ | Many |

||

| ====Kumquats==== | ====Kumquats==== | ||

| Line 70: | Line 44: | ||

| ====Australian and New Guinean species==== | ====Australian and New Guinean species==== | ||

| ] are genetically separate, |

] are genetically separate. Wu, ''et al.'', found that several of the finger lime cultivars they evaluated were actually hybrids with round lime.<ref name="Talon" /> ] are hybrids with mandarins, lemons, and/or sweet oranges. | ||

| ====Trifoliate orange==== | ====Trifoliate orange==== | ||

Revision as of 19:47, 13 February 2018

| This article needs attention from an expert in Biology, Genetics or Plants. The specific problem is: article needs correction, updating, and expansion. WikiProject Biology, WikiProject Genetics or WikiProject Plants may be able to help recruit an expert. (April 2015) |

The botanical classification of the species, hybrids, varieties and cultivars belonging to the genus Citrus is called "citrus taxonomy".

Citrus taxonomy refers to the botanical classification of the species, varieties, cultivars, and graft hybrids within the genus Citrus, subgenus Papeda, and related genera, found in cultivation and in the wild.

Citrus taxonomy is complex. Cultivated citrus are derived from various citrus species found in the wild. Some are only selections of the original wild types, while others are hybrids between two or more ancestors. Citrus plants hybridize easily between species with completely different morphologies, and similar-looking citrus fruits may have quite different ancestries. Conversely, different-looking varieties may be nearly genetically identical, and differ only by a bud mutation.

Detailed genomic analysis of wild and domesticated citrus cultivars has suggested that the progenitor of modern citrus species expanded out of the Himalayan foothills in a rapid radiation that has produced at least 10 wild species in South and East Asia and Australia. Most commercial cultivars are the product of hybridization among these wild species, with most coming from crosses involving citrons, mandarins and pumellos. Many different phylogenies for the non-hybrid citrus have been proposed, and the phylogeny based on their nuclear genome does not match that derived from their mitochondrial DNA, probably a consequence of the rapid initial divergence. Taxonomic terminology is not yet settled.

Most hybrids express different ancestral traits when planted from seeds (F2 hybrids) and can continue a stable lineage only through vegetative propagation. Others do reproduce true to type via nucellar seeds in a process called apomixis. Some differ only in disease resistance. Clear genetic lineages are very important for breeding improved cultivars.

Genetic history

All of the wild 'pure' citrus species trace to a common ancestor that lived in the Himalayan foothills, where a late-Miocene citrus fossil, Citrus linczangensis, has been found. At that time, a lessening of the monsoons and resultant drier climate in the region allowed the citrus ancestor to expand across south and east Asia in a rapid genetic radiation. After the plant crossed the Wallace line a second radiation took place in the early Pliocene (about 4 million years ago) to give rise to the Australian species. Using heterozygosity in order to distinguish pure species cultivars from hybrids, a recent genetic analysis by Wu, et al. revealed that most modern cultivars are actually hybrids, with the study identifying just ten species of citrus among those studied, seven in Asia and three in Australia. These are the pumello (Citrus maxima), the 'pure' mandarins (C. reticulata - most mandarin cultivars were hybrids of this species with pumello), the Mangshan mandarin (C. mangshanensis), citrons (C. medica), micranthas (C. micrantha), the Ichang papeda (C. ichangensis), and the oval (Nagami) kumquot (Fortunella margarita). In Australia, there were the desert lime (C. glauca), round lime (C. australis) and the finger lime (C. australasica). Many other cultivars previously identified as species were found to be hybrids,<ref="Talon"/> though not all cultivars were evaluated.

Interbreeding seems possible between all citrus plants, and between citrus plants and some plants which may or may not be categorized as citrus. The ability of citrus hybrids to self-pollinate and to reproduce sexually also helps create new varieties. The three predominant ancestral citrus taxa are citron (C. medica), pomelo (C. maxima), and mandarin (C. reticulata). These taxa interbreed freely, despite being quite genetically distinct, having arisen through allopatric speciation, with citrons evolving in northern Indochina, pomelos in the Malay Archipelago, and mandarins in Vietnam, southern China, and Japan. The hybrids of these taxa include familiar citrus fruits like oranges, grapefruit, lemons, limes, and some tangerines. Citrons have also been hybridized with other citrus taxa, for example, crossed with micranta to produce the Key lime. In many cases, these crops are propagated asexually, and lose their characteristic traits if bred. However, some of these hybrids have interbred with one another and with the original taxa, making the citrus family tree a complicated network.

The trifoliate orange and kumquats do not naturally interbreed with core taxa due to different flowering times, but hybrids (such as the citrange and calamondin) exist. Australian limes and Clymenia are native to Australia and Papua New Guinea, so they did not naturally interbreed with the four core taxa; but they have been crossbred with mandarins and calamondins by modern breeders. Humans have deliberately bred new citrus fruits by propagating wild-found seedlings (e.g. clementines), creating or selecting mutations of hybrids, (e.g. Meyer lemon), and crossing different varieties (e.g. 'Australian Sunrise', a finger lime and calamondin cross).

Citrus naming systems

See also: Botanical nameThere are two main complete systems of citrus taxonomy, those of Tanaka and Swingle; however, many citrus types were identified and named by individual taxonomists. The basis of the "Tanaka system" is to provide a separate species name for each cultivar, regardless of whether it is pure or a hybrid of two or more species or varieties. Tanaka is therefore considered to have been a taxonomic "splitter". The "Swingle system" works differently, in that it first divides the genus Citrus into species, secondly divides it further into varieties, and lastly divides it again into cultivars or hybrids. The Swingle system is generally followed today with much modification; however, there are still huge differences in nomenclature between countries and even individual scientists. Both systems predate the genomic analysis of Wu, et al.<ref=name "Talon" />

Common name confusions

See also: Folk taxonomyMost commercial varieties are descended from one or more of citrons, mandarins, and pomelos. The same common names may be given to different citrus hybrids or mutations. Fruit with similar ancestry may be quite different in name and traits (e.g. grapefruit, common oranges, and ponkans, all pomelo-mandarin hybrids). Note that many traditional citrus groups, such as true sweet oranges and lemons, seem to be bud sports, mutant descendants of a single hybrid ancestor.

Ancestral species

Mandarins

Mandarin oranges (tangerines, satsumas) are one of the basic species. Even pure-bred ones are genetically diverse, and many varieties commercially called mandarins are actually hybrids.. Wu, et al., divided mandarins into three classes based on their degree of hybridization. In addition to the genetically-pure mandarins, a second group have arisen as a result of hybridization with pomelos, while a third arose from the crossing of this hybrid with sweet oranges, themselves the product of the back-crossing of hybrid mandarins with pomelos. Some are commercial mandarins are hybrids with lemons.

Citrons

Many varieties of true (non-hybrid) Citron have distinctly different forms. The citron is usually fertilized by self-pollination, and this results in the lowest levels of heterozygosity among the citrus species. This also means that it will generally be a male parent of any citrus hybrid, rather than a female one. Many citron varieties were proven to be non-hybrids despite their morphological differences; however, the florentine citron is probably of hybrid origin.

Some fingered citron varieties are used in buddhist offerings, and some more common varieties are used as the etrog in the Jewish harvest festival of Sukkot. There is also a specific variety of citron called etrog. The Mountain citron has no relation to the true citron and belongs to the citrus subg. Papeda.

Kumquats

Kumquats are a separate species, with few hybrids, none of which is commonly called "kumquat".

Australian and New Guinean species

Australian and New Guinean citrus species are genetically separate. Wu, et al., found that several of the finger lime cultivars they evaluated were actually hybrids with round lime. Some commercial varieties are hybrids with mandarins, lemons, and/or sweet oranges.

Trifoliate orange

The trifoliate orange is a cold hardy plant distinguishable by its leaves with three leaflets. It is the only member of the Poncirus genus (disputed), but is close enough to the Citrus genus to be used as a rootstock. The Indian wild orange is, according to some research, one of the ancestors of today's cultivated citrus fruits. The bergamot orange is likely to be a hybrid of Citrus limetta and Citrus aurantium.

Hybrids

Citrus hybrids include many varieties and species that have been selected by plant breeders, usually for the useful characteristics of the fruit. Some citrus hybrids occurred naturally, and others have been deliberately created, either by cross pollination and selection among the progeny, or (rarely, and only recently) as somatic hybrids. The aim of plant breeding of hybrids is to use two or more different citrus varieties or species, in order to get intermediate traits, or the most desirable traits of the parents. In some cases, particularly with the natural hybrids, hybrid speciation has occurred, so the new plants are considered a different species from any of their parents. Citrus hybrid names are usually marked with a multiplication sign after the word "Citrus", for example Citrus × aurantifolia.

Labelling of hybrids

Citrus fruit taxonomy is still poorly understood, and even modern hybrids of known parentage are sold under general names that give little information about their ancestry, or technically incorrect information.

This can be a problem for those who can eat only some citrus varieties. Drug interactions with chemicals found in some citrus, including grapefruit and Seville oranges, make the ancestry of citrus fruit of interest; many commonly sold citrus varieties are grapefruit hybrids or pummello-descended grapefruit relatives. One medical review has advised patients on medication to avoid all citrus juice, although some citrus fruits contain no furanocoumarins.

Citrus allergies can also be specific to only some fruit or some parts of some fruit.

Major citrus hybrids

The most known citrus hybrids that are sometimes treated as a species by themselves, especially in folk taxonomy, are:

- Grapefruit: Grapefruits are more akin to the pommelo ancestor.

- Lemon and Lime: Most lemons are from one common ancestor, and diverged by mutation. The ancestor was a hybrid with citron, pummelo and mandarin ancestry; citrons contribute the largest share of the genome.

- Orange: Not all the fruits that are called by the name "orange" share much genetic affiliation. The common sweet orange and sour orange genetics are like those of the grapefruit, a cross between a pommelo and a mandarin orange. They are all intermediate between the two ancestors in size, flavor and shape. The above-mentioned oranges have the orange color of the mandarin orange in their outer peels and segments, and are easier to peel than the grapefruits.

Sweet lemons and sweet limes

Sweet lemons, sweet limes, and rough lemons are hybrids similar to non-sweet lemons and limes, but with less citron parentage.

Sweet lemons and sweet limes are less acid than regular lemons and limes. The name is applied to:

- The lumia from the Mediterranean basin, probably Italy, is a big dry citron-like citrus that is pear shaped and not necessarily sweet.

- The Persian sweet lime, also known as the limetta, is small and round like a common lime, with sweet juice.

- The Palestinian sweet lime – Citrus × latifolia – from India is mainly used as a rootstock.

Sweet limes and lemons are not sharply separated:

The sweet lime, Citrus limettioides Tan. (syn. C. lumia Risso et Poit.), is often confused with the sweet lemon, C. limetta Tan., (q.v. under LEMON) which, in certain areas, is referred to as "sweet lime". In some of the literature, it is impossible to tell which fruit is under discussion.

The same plant may also be known by different names:

The Indian sweet lime is the mitha nimbu (numerous modifications and other local names) of India, the limûn helou or succari of Egypt, and the Palestine sweet lime (to distinguish it from the Millsweet and Tunisian limettas, commonly called sweet limes).

Other minor citrus hybrids (partial list)

- Shikwasa, Hirami lemon – Citrus × depressa

- Kaffir lime – Citrus × hystrix

- Rangpur lime – Citrus × limonia

- Sudachi – Citrus sudachi

- Yuzu – Citrus ichangensis × reticulata

- Ponderosa – Citrus limon × medica

- Rhobs al-arsa – Citrus limon

- Florentine citron – Citrus limonimedica

- Oroblanco, oro blanco (white gold) or sweetie and Melogold – (Citrus grandis Osbeck × Citrus Paradisi Macf.)

- Pixie mandarin – a cross between King tangor and Dancy mandarin with possible unknown pollen donor

- Ugli fruit – Citrus reticulata × Citrus paradisi

- Lemonade fruit – a cross between navel orange and lemon

Chimera

Graft-chimaeras, also called graft hybrids, can occur in Citrus. The cells are not somatically fused but rather mix the tissues from scion and rootstock after grafting, a popular example the Bizzaria orange. In formal usage, these are marked with a plus sign "+" instead with an "x".

Intergenetic hybrids

Citrofortunella

Citrofortunella according to the Swingle system, is a hybrid genus, containing intergeneric hybrids between members of the genus Citrus and the closely related Fortunella. It is named after its two parent genera. Such hybrids often combine the cold hardiness of the Fortunella, such as the Kumquat, with some edibility properties of the citrus species. Citrofortunellas, which are all hybrids, are marked with the multiplication sign before the word "Citrofortunella", for example × Citrofortunella microcarpa or × Citrofortunella mitis which refer to the same plant.

Carl Peter Thunberg originally classified the kumquats as Citrus japonica in his 1784 book, Flora Japonica. In 1915, Walter T. Swingle reclassified them in a segregate genus, Fortunella, named in honor of Robert Fortune. Seven species of Fortunella have generally been recognized—F. japonica, F. margarita, F. crassifolia, F. hindsii, F. obovata and F. polyandra, as well as the recently described F. bawangica. Since the kumquat is a cold hardy species, there are many hybrids between common citrus members and the kumquat (most popularly the calamondin that occurred naturally). Those hybrids are not citrus hybrids, according to Swingle, but reside in a separate hybrid genus which he called × Citrofortunella.

Subsequent study of the many commercial lineages revealed such complexity that the genera could not be separated. Consequently, in accordance with the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, the correct genus name reverted to Citrus. The Flora of China returns the kumquat to Citrus and combines the species into the single species as Citrus japonica, and today the Fortunella and Citrofortunella are nothing else but regular citrus.

These plants are hardier and more compact than most citrus plants, often referred to as cold hardy citrus. They produce small acidic fruit and make good ornamental plants. Citrofortunella hybrids include:

- Calamondin – (tangerine crossed with kumquat)

- Citrangequat – (citrange crossed with kumquat)

- Limequat – (Citrofortunella floridana) – (Key lime crossed with kumquat)

- Orangequat – Citrofortunella nippon – (satsuma mandarin crossed with kumquat)

- Procimequat – (Citrofortunella floridana) – (limequat crossed with kumquat)

- Sunquat – Citrus limon × japonica – (lemon crossed with kumquat)

- Yuzuquat – Citrus ichangensis × reticulata – (yuzu crossed with kumquat)

Citrocirus

See also: Citrus taxonomy § Poncirus & CitrocitrusCitrocirus also according to the Swingle system, is a hybrid genus, containing hybrids between members of the genus Citrus and the closely related Poncirus, which includes the trifoliate orange, a cold hardy plant that is commonly used as a citrus rootstock. Citrocirus commonly refers to the citranges which are hybrids between the trifoliate and sweet oranges. However a molecular investigation suggested that Fortunella, Citrofortunella, Poncirus and Citrocirus should all be equivocally included in the genus Citrus.

According to the Swingle system, the trifoliate orange, a cold hardy plant that is commonly used as a citrus rootstock, is not included in the genus Citrus, but in a related genus, Poncirus. Therefore, the citrange, which is a hybrid between the trifoliate and the sweet orange, is placed into a hybrid genus called Citrocirus (not a valid botanical name). However, molecular investigation suggests Poncirus should be equivocally included in the genus Citrus.

- Citrange – Citrus sinensis × Poncirus trifoliata – three cultivars: 'Troyer', 'Rusk' and 'Carrizo'.

- Citrumelo – Citrus paradisi × Poncirus trifoliata

Citrus relatives

Another issue of controversy is whether the citrus-related genera are to be included in the genus or not.

Papeda

Swingle coined the Citrus subg. Papeda to separate its members from the more edible citrus. Papedas also differ from regular citrus in that its stamens grow separately, not united at the base.

Reclassification of Microcitrus and Eremocitrus

The edible Australian limes are starting to be domesticated and commercially grown. Recent molecular research suggests that although Swingle placed them in the separate genera Microcitrus and Eremocitrus, they should also be included in the genus Citrus.

| Australian limes |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Triphasia and Clymenia

Two additional genera, Triphasia and Clymenia, are likewise very closely related to the Citrus genus and bear hesperidium fruits, but they are not usually considered part of it. At least one, Clymenia, will hybridize with kumquats and some limes.

Wild lime

The wild lime—native to southern Florida and Texas in the United States, Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and South America as far south as Paraguay—does not belong in the Citrus genus. It is part of another genus in the Rutaceae family, Zanthoxylum (which also includes Sichuan pepper), and was classified as Zanthoxylum fagara by Charles Sprague Sargent.

International taxonomy

The International Association for Plant Taxonomy was founded in 1950 to resolve the taxonomic problem of all the plants. They hold meetings every five years to review the updated information and try to reach consensus. The current president is David Mabberley.

See also

References

- ^ G. A. Moore (Sep 2001). "Oranges and lemons: clues to the taxonomy of Citrus from molecular markers". Trends in Genetics. 17: 536–40. doi:10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02442-8. PMID 11525837.

- Velasco, Riccardo; Licciardello, Concetta (2014). "A genealogy of the citrus family". Nature Biotechnology. 32: 640–642.

- ^ G Albert Wu; et al. "Sequencing of diverse mandarin, pomelo and orange genomes reveals complex history of admixture during citrus domestication". Nature. 32: 656–662. doi:10.1038/nbt.2906. PMC 4113729. PMID 24908277.

- Nicolosi, Elisabetta; La Malfi, Stefano; El-Otmani, Mohamed; Neghi, Moshe; Goldschmidt, Eliezer E (2005). "The Search for the Authentic Citron (Citrus medicus L.): Historic and Genetic Analysis". HortSciece. 40: 1963–1968.

- ^ Wu, Guohong Albert; Terol, Javier; Ibanez, Victoria; López-García, Antonio; Pérez-Román, Estela; Borredá, Carles; Domingo, Concha; Tadeo, Francisco R; Carbonell-Caballero, Jose; Alonso, Roberto; Curk, Franck; Du, Dongliang; Ollitrault, Patrick; Roose, Mikeal L. Roose; Dopazo, Joaquin; Gmitter Jr, Frederick G.; Rokhsar, Daniel; Talon, Manuel (2018). "Genomics of the origin and evolution of Citrus". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature25447.

- Cite error: The named reference

AGLthesiswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Li, Xiaomeng; Xie, Rangjin; Lu, Zhenhua; Zhou, Zhiqin (2010). "The Origin of Cultivated Citrus as Inferred from Internal Transcribed Spacer and Chloroplast DNA Sequence and Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism Fingerprints". Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 135: 341–350.

- Shrestha, Ram Lal; Dhakal, Durga Datta; Gautum, Durga Mani; Paudyal, Krishna Prasad; Shrestha, Sangita (2012). "Genetic Diversity Assessment of Acid Lime (Citrus aurantifolia Swingle) Landraces in Nepal, Using SSR Markers j". American Journal of Plant Sciences. 3: 1674–1681. doi:10.4236/ajps.2012.312204.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Curk, Franck; Ancillo, Gema Ancillo; Garcia-Lor, Andres; Luro, François; Perrier, Xavier; Jacquemoud-Collet, Jean-Pierre; Navarro, Luis; Ollitrault, Patrick (2014). "Next generation haplotyping to decipher nuclear genomic interspecific admixture in Citrus species: analysis of chromosome 2". BMC Genetics. 15: 152.

- Phylogenetic Relationships of Citrus and Its Relatives Based on matK Gene Sequences

- Citrus limon (L.) Burm. f. (pro. sp.) — Classifications: Lemon and more

- Froelicher, Yann. "New universal mitochondrial PCR markers reveal new information on maternal citrus phylogeny". Tree Genetics. 7: 49–61. doi:10.1007/s11295-010-0314-x.

- Page, Martin (2008). Growing Citrus: The Essential Gardener's Guide. Timber Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-88192-906-5.

- Iqrar A. Khan, Citrus Genetics, Breeding and Biotechnology p. 49.

- Classification of Citrus

- Genetic similarity of citrus fresh fruit market cultivars

- Citrus phylogeny and genetic origin of important species as investigated by molecular markers. 2000

- Assessing genetic diversity and population structure in a Citrus germplasm collection utilizing simple sequence repeat markers (SSRs) by: Noelle A. Barkley, Mikeal L. Roose, Robert R. Krueger and Claire T. Federici Archived 2013-01-28 at archive.today

- Phylogenetic relationships in the "true citrus fruit trees" revealed by PCR-RFLP analysis of cpDNA. 2004

- "The Search for the Authentic Citron: Historic and Genetic Analysis"; HortScience 40(7):1963–1968. 2005 Archived September 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Chromosome Numbers in the Subfamily Aurantioideae with Special Reference to the Genus Citrus; C. A. Krug. Botanical Gazette, Vol. 104, No. 4 (Jun., 1943), pp. 602–611

- The relationships among lemons, limes and citron: a chromosomal comparison. by R. Carvalhoa, W.S. Soares Filhob, A.C. Brasileiro-Vidala, M. Guerraa.

- See below Citrus taxonomy#Poncirus, Microcitrus & Eremocitrus

- "Genetic Transformation of Poncirus trifoliata (Trifoliate Orange)". springer.com.

- Malik, S. K., R. Chaudhury, O. P. Dhariwal and R. K. Kalia. (2006). Collection and characterization of Citrus indica Tanaka and C. macroptera Montr.: wild endangered species of northeastern India.

- "RFLP Analysis of the Origin of Citrus Bergamia, Citrus Jambhiri, and Citrus Limonia". actahort.org.

- Larry K. Jackson and Stephen H. Futch. "Robinson Tangerine". ufl.edu.

- Commernet, 2011. "20-13.0061. Sunburst Tangerines; Classification and Standards, 20-13. Market Classification, Maturity Standards And Processing Or Packing Restrictions For Hybrids, D20. Departmental, 20. Department of Citrus, Florida Administrative Code". State of Florida. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Saito, M; Hirata-Koizumi, M; Matsumoto, M; Urano, T; Hasegawa, R (2005). "Undesirable effects of citrus juice on the pharmacokinetics of drugs: focus on recent studies". Drug Safety. 28 (8): 677–94. doi:10.2165/00002018-200528080-00003. PMID 16048354.

- Bailey, David G. (2010). "Fruit juice inhibition of uptake transport: a new type of food-drug interaction". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 70 (5): 645–55. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03722.x. PMC 2997304. PMID 21039758.

- http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/tangelo.html

- ^ Widmer, Wilbur (2006). "One Tangerine/Grapefruit Hybrid (Tangelo) Contains Trace Amounts of Furanocoumarins at a Level Too Low To Be Associated with Grapefruit/Drug Interactions". Journal of Food Science. 70 (6): c419–22. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb11440.x.

- Bourrier, T; Pereira, C (2013). "Allergy to citrus juice". Clinical and Translational Allergy. 3 (Suppl 3): P153. doi:10.1186/2045-7022-3-S3-P153. PMC 3723546.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Cardullo, AC; Ruszkowski, AM; DeLeo, VA (1989). "Allergic contact dermatitis resulting from sensitivity to citrus peel, geraniol, and citral". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 21 (2 Pt 2): 395–7. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(89)80043-x. PMID 2526827.

- Boonpiyathad, S (2013). "Chronic angioedema caused by navel orange but not citrus allergy: case report". Clinical and Translational Allergy. 3 (Suppl 3): P159. doi:10.1186/2045-7022-3-S3-P159. PMC 3723846.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Corazza-Nunes, M.J. "Assessment of genetic variability in grapefruits (Citrus paradisi Macf.) and pummelos (C. maxima (Burm.) Merr.) using RAPD and SSR markers". Euphytica. 126: 169–176. doi:10.1023/A:1016332030738.

- ^ Lemons: Diversity and Relationships with Selected Citrus Genotypes as Measured with Nuclear Genome Markers

- The draft genome of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis)

- See respective pages for sources.

- https://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/sweet_lime.html Purdue University

- Please note that this author also confused the lumia and the Palestinian sweet lime. Those two are quite distinguishable, and definitely not the same, whereas the Palestinian sweet lime and the limetta can possibly be similar or even identical. See following citation of The Citrus Industry (book) and adjacent photos.

- The Citrus Industry Volume I Palestine at Citrus Variety Collection Website

- Volume I Archived 2012-02-05 at the Wayback Machine See heading: Indian (Palestine)

- "EasyBloom :: Calamondin - x Citrofortunella mitis :: Detailed Plant Information". easybloom.com.

- Gardens World Archived 2014-12-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Mabberley (Blumea 49: 481–498. 2004) Citrus (Rutaceae): A Review of Recent Advances in Etymology, Systematics and Medical Applications

- Zhang Dianxiang, Thomas G. Hartley, David J. Mabberley, Rutaceae in Flora of China 11: 51-97 (2008)

- Jorma Koskinen; Sylvain Jousse. "Citrus Pages / Kumquats". free.fr.

- Nicolosi et al. (2000)

- de Araújo et al. (2003)

- ^ Nicolosi et al. (2000), de Araújo et al. (2003)

- A classification for edible Citrus (Rutaceae) by David Mabberley

- Jorma Koskinen; Sylvain Jousse. "Citrus Pages / Native Australian varieties". free.fr.

- "Zanthoxylum fagara". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2009-11-27.

- Citrus Pages - a comprehensive article on citrus taxonomy

Books

External links

- USDA Citrus Genome Database

- USDA Classification

- Genetic Diversity in Citrus

- A classification for edible Citrus (Rutaceae)

- Citrus Pages A comprehensive article on citrus taxonomy

- Burkill I. H. (1931). "An enumeration of the species of Paramignya, Atalantia and Citrus, found in Malaya". Gard. Bull. Straits Settlem. 5: 212–220.

- Mabberley, D. J. (1998). "Australian Citreae with notes on other Aurantioideae (Rutaceae)". Telopea 7 (4): 333–344. Available online (pdf).

- Fruits of warm climates

- Fortunella crassifolia Swingle - Fruits and Seeds Flavon's Wild herb and Alpine plants

- International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (Tokyo Code)

- GRIN database for Species of Citrus

Molecular classification

- DNA Analysis as a Tool for Citrus reticulata Adulteration Detection and Variety Identification in Commercial Orange Juices

- DNA Amplified Fingerprinting, A Useful Tool for Determination of Genetic Origin and Diversity Analysis in Citrus

| Speciation | |

|---|---|

| Basic concepts | |

| Geographic modes | |

| Isolating factors | |

| Hybrid concepts | |

| Speciation in taxa | |

| Breeds and cultivars | |

|---|---|

| Methods | |

| Animal breeds | |

| Plant cultivars | |

| Selection methods and genetics | |

| Other | |