| Revision as of 16:38, 3 January 2020 editWjm20996 (talk | contribs)57 editsm →Acoustics: Added the graphs that I have made to describe the weighting functions.← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:52, 5 January 2020 edit undo36.75.64.218 (talk)No edit summaryTags: references removed Mobile edit Mobile web editNext edit → | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="text-align:right; border:none;" | 80 | | style="text-align:right; border:none;" | 80 | ||

| | style="text- |

| style="text-al:right; bordright:0" | {{gaps|100|000|000}} || style="border:none;" |:right; border:none;ight:0" | {{gaps|10|000}} || style="border:none;" | | ||

| | style="text-align:right; border:none; padding-right:0" | {{gaps|10|000}} || style="border:none;" | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="text-align:right; border:none;" | |

| style="text-align:right; border:none;" | -right:0" | {{gaps|10|000|000}| | ||

| | style="text-align:right; border:none; |

| style="text-align:right; border:none; dght:0" | {{gaps|3|16| style="border:none;" | | ||

| | style="text-align:right; border:none; padding-right:0" | {{gaps|3|162}} || style="border:none;" | | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="text-align:right; border:none;" | 60 | | style="text-align:right; border:none;" | 60 | ||

| Line 113: | Line 111: | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | style="text-align:right; border:none;" | −100 | | style="text-align:right; border:none;" | −100 | ||

| | style="text-align:right; border: |

| style="text-align:right; border:noneright:0" | 0 || style="border; eft:0;" | {{0|000|000|1}} | ||

| | style=" |

| style="align:right;0" | 0 || style="border:none; padding-left:0;" | {{gaps|00|01}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | colspan="5" style="text-align:left; |

| colspan="5" style="text-align:left; backff;" | An examscale showing powe ratios ', ame ratios {{sqand 1ub>& | ||

| |} | |||

| The '''decibel''' (symbol: '''dB''') is a ] of measurement used to express the ratio of one value of a ] to another, on a ], the logarithmic quantity being called the power level or field level, respectively. It can be used to express a change in value (e.g., +1 dB or −1 dB) or an absolute value. In the latter case, it expresses the ratio of a value to a fixed reference value; when used in this way, a suffix that indicates the reference value is often appended to the decibel symbol. For example, if the reference value is 1 ], then the suffix is "]" (e.g., "20 dBV"), and if the reference value is one ], then the suffix is "]" (e.g., "20 dBm").<ref name="clqgmk"/> | |||

| The '''decibbol] oeasunt used to express the rof on quantir field quantity]] to another, on a ], the logarithquantity being called the prespectively. Itn be used to express a chae in value (e.g., + &r an absolute value. In tlatter case, it of a value to a fixed reference value; when used in this way, a suffix that indicates the reference value is often appended to the. For example, if then the suffix and menscales are used when expressing a ratio in decibels, he nature of the quantitiewer and fiehen expressiatio, the number of decibels is ten times its [[Common logarithm|logaref>{{cite book |tiE Standard 100: a dictionary of IEEE standards |page=, a change in ''power'' by a factor of 10 corresponds to en ) quantities, a change in ''amplitude'' by a factor of 10 corresponds hange in level. The decibel scales differ by a factor of two so that thd field levels change by the same number of ibels tear loads. | |||

| The definition of the decibel is based on the |

The definition of the decibel is based on the measuremt of power in ] of the early 20th century in the ] in the United States. One decibel is one tenth (i-]]) of one '''named r, the bel is seldom used. Today, the decibel iused for a wide variety of measurements in science and ], most prominently in ], ], a electronics, the ]s of amplifiers, ]] of signals, and ]s are often expressed in decibels. | ||

| In |

In tal S of Quantities]], the decis defined as a unit of mequantities of(logarithmic quantity)|level]] or level difference, which are defined as the ] of the ratio of power- or field-type cite web |title=o/=[ OOrgan fo | ||

| =={{anchor|MSC|TU|bel}}History== | =={{anchor|MSC|TU|bel}}History== | ||

Revision as of 06:52, 5 January 2020

This article is about the logarithmic unit. For other uses, see Decibel (disambiguation).

| dB | Power ratio | Amplitude ratio | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 10000000000 | 100000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 90 | 1000000000 | 31623 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 80 | 100000000 | :right; border:none;ight:0" | 10000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| -right:0" | {{gaps|10|000|000}| | {{gaps|3|16| style="border:none;" | | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 60 | 1000000 | 1000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 50 | 100000 | 316 | .2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | 10000 | 100 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30 | 1000 | 31 | .62 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | 100 | 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | 10 | 3 | .162 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | 3 | .981 ≈ 4 | 1 | .995 ≈ 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 1 | .995 ≈ 2 | 1 | .413 ≈ √2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | .259 | 1 | .122 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −1 | 0 | .794 | 0 | .891 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −3 | 0 | .501 ≈ 1⁄2 | 0 | .708 ≈ √1⁄2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −6 | 0 | .251 ≈ 1⁄4 | 0 | .501 ≈ 1⁄2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −10 | 0 | .1 | 0 | .3162 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −20 | 0 | .01 | 0 | .1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −30 | 0 | .001 | 0 | .03162 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −40 | 0 | .0001 | 0 | .01 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −50 | 0 | .00001 | 0 | .003162 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −60 | 0 | .000001 | 0 | .001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −70 | 0 | .0000001 | 0 | .0003162 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −80 | 0 | .00000001 | 0 | .0001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −90 | 0 | .000000001 | 0 | .00003162 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| −100 | 0 | 000 | 0 | 0001 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| An examscale showing powe ratios ', ame ratios {{sqand 1ub>&

The definition of the decibel is based on the measuremt of power in telephony of the early 20th century in the Bell System in the United States. One decibel is one tenth (i-]]) of one named r, the bel is seldom used. Today, the decibel iused for a wide variety of measurements in science and engineering, most prominently in acoustics, electronics, a electronics, the Gain (electronics)ins of amplifiers, ]] of signals, and signalnoise ratios are often expressed in decibels. In tal S of Quantities]], the decis defined as a unit of mequantities of(logarithmic quantity)|level]] or level difference, which are defined as the logarithm of the ratio of power- or field-type cite web |title=o/=[ OOrgan fo HistoryThe decibel originates from methods used to quantify signal loss in telegraph and telephone circuits. The unit for loss was originally Miles of Standard Cable (MSC). 1 MSC corresponded to the loss of power over a 1 mile (approximately 1.6 km) length of standard telephone cable at a frequency of 5000 radians per second (795.8 Hz), and matched closely the smallest attenuation detectable to the average listener. The standard telephone cable implied was "a cable having uniformly distributed resistance of 88 Ohms per loop-mile and uniformly distributed shunt capacitance of 0.054 microfarads per mile" (approximately corresponding to 19 gauge wire). In 1924, Bell Telephone Laboratories received favorable response to a new unit definition among members of the International Advisory Committee on Long Distance Telephony in Europe and replaced the MSC with the Transmission Unit (TU). 1 TU was defined such that the number of TUs was ten times the base-10 logarithm of the ratio of measured power to a reference power. The definition was conveniently chosen such that 1 TU approximated 1 MSC; specifically, 1 MSC was 1.056 TU. In 1928, the Bell system renamed the TU into the decibel, being one tenth of a newly defined unit for the base-10 logarithm of the power ratio. It was named the bel, in honor of the telecommunications pioneer Alexander Graham Bell. The bel is seldom used, as the decibel was the proposed working unit. The naming and early definition of the decibel is described in the NBS Standard's Yearbook of 1931:

In 1954, J. W. Horton argued that the use of the decibel as a unit for quantities other than transmission loss led to confusion, and suggested the name 'logit' for "standard magnitudes which combine by addition". In April 2003, the International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM) considered a recommendation for the inclusion of the decibel in the International System of Units (SI), but decided against the proposal. However, the decibel is recognized by other international bodies such as the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) and International Organization for Standardization (ISO). The IEC permits the use of the decibel with field quantities as well as power and this recommendation is followed by many national standards bodies, such as NIST, which justifies the use of the decibel for voltage ratios. The term field quantity is deprecated by ISO 80000-1, which favors root-power. In spite of their widespread use, suffixes (such as in dBA or dBV) are not recognized by the IEC or ISO. DefinitionISO 80000-3 describes definitions for quantities and units of space and time. The decibel for use in acoustics is defined in ISO 80000-8. The major difference from the article below is that for acoustics the decibel has no absolute value. The ISO Standard 80000-3:2006 defines the following quantities. The decibel (dB) is one-tenth of a bel: 1 dB = 0.1 B. The bel (B) is 1⁄2 ln(10) nepers: 1 B = 1⁄2 ln(10) Np. The neper is the change in the level of a field quantity when the field quantity changes by a factor of e, that is 1 Np = ln(e) = 1, thereby relating all of the units as nondimensional natural log of field-quantity ratios, 1 dB = 0.11513… Np = 0.11513…. Finally, the level of a quantity is the logarithm of the ratio of the value of that quantity to a reference value of the same kind of quantity. Therefore, the bel represents the logarithm of a ratio between two power quantities of 10:1, or the logarithm of a ratio between two field quantities of √10:1. Two signals whose levels differ by one decibel have a power ratio of 10, which is approximately 1.25893, and an amplitude (field quantity) ratio of 10 (1.12202). The bel is rarely used either without a prefix or with SI unit prefixes other than deci; it is preferred, for example, to use hundredths of a decibel rather than millibels. Thus, five one-thousandths of a bel would normally be written '0.05 dB', and not '5 mB'. The method of expressing a ratio as a level in decibels depends on whether the measured property is a power quantity or a root-power quantity; see Field, power, and root-power quantities for details. Power quantitiesWhen referring to measurements of power quantities, a ratio can be expressed as a level in decibels by evaluating ten times the base-10 logarithm of the ratio of the measured quantity to reference value. Thus, the ratio of P (measured power) to P0 (reference power) is represented by LP, that ratio expressed in decibels, which is calculated using the formula: The base-10 logarithm of the ratio of the two power quantities is the number of bels. The number of decibels is ten times the number of bels (equivalently, a decibel is one-tenth of a bel). P and P0 must measure the same type of quantity, and have the same units before calculating the ratio. If P = P0 in the above equation, then LP = 0. If P is greater than P0 then LP is positive; if P is less than P0 then LP is negative. Rearranging the above equation gives the following formula for P in terms of P0 and LP: Field quantities and root-power quantitiesMain article: Field, power, and root-power quantitiesWhen referring to measurements of field quantities, it is usual to consider the ratio of the squares of F (measured field) and F0 (reference field). This is because in most applications power is proportional to the square of field, and historically their definitions were formulated to give the same value for relative ratios in such typical cases. Thus, the following definition is used: The formula may be rearranged to give Similarly, in electrical circuits, dissipated power is typically proportional to the square of voltage or current when the impedance is constant. Taking voltage as an example, this leads to the equation for power gain level LG: where Vout is the root-mean-square (rms) output voltage, Vin is the rms input voltage. A similar formula holds for current. The term root-power quantity is introduced by ISO Standard 80000-1:2009 as a substitute of field quantity. The term field quantity is deprecated by that standard. Relationship between power level and field levelAlthough power and field quantities are different quantities, their respective levels are historically measured in the same units, typically decibels. A factor of 2 is introduced to make changes in the respective levels match under restricted conditions such as when the medium is linear and the same waveform is under consideration with changes in amplitude, or the medium impedance is linear and independent of both frequency and time. This relies on the relationship holding. In a nonlinear system, this relationship does not hold by the definition of linearity. However, even in a linear system in which the power quantity is the product of two linearly related quantities (e.g. voltage and current), if the impedance is frequency- or time-dependent, this relationship does not hold in general, for example if the energy spectrum of the waveform changes. For differences in level, the required relationship is relaxed from that above to one of proportionality (i.e., the reference quantities P0 and F0 need not be related), or equivalently, must hold to allow the power level difference to be equal to the field level difference from power P1 and V1 to P2 and V2. An example might be an amplifier with unity voltage gain independent of load and frequency driving a load with a frequency-dependent impedance: the relative voltage gain of the amplifier is always 0 dB, but the power gain depends on the changing spectral composition of the waveform being amplified. Frequency-dependent impedances may be analyzed by considering the quantities power spectral density and the associated field quantities via the Fourier transform, which allows elimination of the frequency dependence in the analysis by analyzing the system at each frequency independently. ConversionsSince logarithm differences measured in these units are used to represent power ratios and field ratios, the values of the ratios represented by each unit are also included in the table.

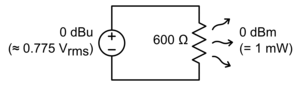

ExamplesThe unit dBW is often used to denote a ratio for which the reference is 1 W, and similarly dBm for a 1 mW reference point.

(31.62 V / 1 V) ≈ 1 kW / 1 W, illustrating the consequence from the definitions above that LG has the same value, 30 dB, regardless of whether it is obtained from powers or from amplitudes, provided that in the specific system being considered power ratios are equal to amplitude ratios squared.

A change in power ratio by a factor of 10 corresponds to a change in level of 10 dB. A change in power ratio by a factor of 2 or 1⁄2 is approximately a change of 3 dB. More precisely, the change is ±3.0103 dB, but this is almost universally rounded to "3 dB" in technical writing. This implies an increase in voltage by a factor of √2 ≈ 1.4142. Likewise, a doubling or halving of the voltage, and quadrupling or quartering of the power, is commonly described as "6 dB" rather than ±6.0206 dB. Should it be necessary to make the distinction, the number of decibels is written with additional significant figures. 3.000 dB is a power ratio of 10, or 1.9953, about 0.24% different from exactly 2, and a voltage ratio of 1.4125, 0.12% different from exactly √2. Similarly, an increase of 6.000 dB is the power ratio is 10 ≈ 3.9811, about 0.5% different from 4. PropertiesThe decibel is useful for representing large ratios and for simplifying representation of multiplied effects such as attenuation from multiple sources along a signal chain. Its application in systems with additive effects is less intuitive. Reporting large ratiosThe logarithmic scale nature of the decibel means that a very large range of ratios can be represented by a convenient number, in a manner similar to scientific notation. This allows one to clearly visualize huge changes of some quantity. See Bode plot and Semi-log plot. For example, 120 dB SPL may be clearer than "a trillion times more intense than the threshold of hearing". Representation of multiplication operationsLevel values in decibels can be added instead of multiplying the underlying power values, which means that the overall gain of a multi-component system, such as a series of amplifier stages, can be calculated by summing the gains in decibels of the individual components, rather than multiply the amplification factors; that is, log(A × B × C) = log(A) + log(B) + log(C). Practically, this means that, armed only with the knowledge that 1 dB is a power gain of approximately 26%, 3 dB is approximately 2× power gain, and 10 dB is 10× power gain, it is possible to determine the power ratio of a system from the gain in dB with only simple addition and multiplication. For example:

However, according to its critics, the decibel creates confusion, obscures reasoning, is more related to the era of slide rules than to modern digital processing, and is cumbersome and difficult to interpret. Representation of addition operationsFurther information: Logarithmic additionAccording to Mitschke, "The advantage of using a logarithmic measure is that in a transmission chain, there are many elements concatenated, and each has its own gain or attenuation. To obtain the total, addition of decibel values is much more convenient than multiplication of the individual factors." However, for the same reason that humans excel at additive operation over multiplication, decibels are awkward in inherently additive operations: "if two machines each individually produce a sound pressure level of, say, 90 dB at a certain point, then when both are operating together we should expect the combined sound pressure level to increase to 93 dB, but certainly not to 180 dB!"; "suppose that the noise from a machine is measured (including the contribution of background noise) and found to be 87 dBA but when the machine is switched off the background noise alone is measured as 83 dBA. the machine noise may be obtained by 'subtracting' the 83 dBA background noise from the combined level of 87 dBA; i.e., 84.8 dBA."; "in order to find a representative value of the sound level in a room a number of measurements are taken at different positions within the room, and an average value is calculated. Compare the logarithmic and arithmetic averages of 70 dB and 90 dB: logarithmic average = 87 dB; arithmetic average = 80 dB." Addition on a logarithmic scale is called logarithmic addition, and can be defined by taking exponentials to convert to a linear scale, adding there, and then taking logarithms to return. For example, where operations on decibels are logarithmic addition/subtraction and logarithmic multiplication/division, while operations on the linear scale are the usual operations: Note that the logarithmic mean is obtained from the logarithmic sum by subtracting , since logarithmic division is linear subtraction. Quantities in decibels are not necessarily additive, thus being "of unacceptable form for use in dimensional analysis". UsesPerceptionThe human perception of the intensity of sound and light approximates the logarithm of intensity rather than a linear relationship (Weber–Fechner law), making the dB scale a useful measure. Acoustics The decibel is commonly used in acoustics as a unit of sound pressure level. The reference pressure for sound in air is set at the typical threshold of perception of an average human and there are common comparisons used to illustrate different levels of sound pressure. Sound pressure is a field quantity, therefore the field version of the unit definition is used: where prms is the root mean square of the measured sound pressure and pref is the standard reference sound pressure of 20 micropascals in air or 1 micropascal in water. Use of the decibel in underwater acoustics leads to confusion, in part because of this difference in reference value. The human ear has a large dynamic range in sound reception. The ratio of the sound intensity that causes permanent damage during short exposure to that of the quietest sound that the ear can hear is greater than or equal to 1 trillion (10). Such large measurement ranges are conveniently expressed in logarithmic scale: the base-10 logarithm of 10 is 12, which is expressed as a sound pressure level of 120 dB re 20 μPa. Since the human ear is not equally sensitive to all sound frequencies, noise levels at maximum human sensitivity, somewhere between 2 and 4 kHz, are factored more heavily into some measurements using frequency weighting. (See also Stevens' power law.) The main instrument used for measuring sound levels in the environment and in the workplace is the Sound Level Meter. Sound level meters consist of a combination of a microphone, preamplifier, a signal processor and a display. They can be classified as meeting two types according to international standards such as IEC 61672-2013. The response tolerances of the Class 1 or 2 sound level meters differ both in the allowable error in amplitude and the frequency range. For instance, a Class 1 meter will measure within 1.1 dB tolerance at 1 kHz, whereas a Class 2 meter will be with 1.4 dB SPL. At high frequencies, the Class 1 meter has upper and lower tolerance limits defined over the range 16 Hz to 16 kHz, but a Class 2 meter has more lax tolerances and a smaller frequency range 20 Hz to 8 kHz. Sound level meters will often incorporate weighting filters that approximate the response of the human auditory system. The A-weighting filter is commonly used to estimate the noise exposure of a person or a worker. The A-weighting filter reduces the contribution of low and high frequencies to approximate the equal loudness contour for a 40-dB tone at 1 kHz. The C-weighting filter approximates the equal loudness contour for a 100-dB tone at 1 kHz. The C-weighting curve has less of an effect on low and high frequencies. The Z-weighting curve applies no weighting to the measurement but according to the IEC 61672-2013 standard is defined as flat (0-dB weight) between 10 Hz and 20 kHz. Examples of these equal loudness contours are shown in  ElectronicsIn electronics, the decibel is often used to express power or amplitude ratios (as for gains) in preference to arithmetic ratios or percentages. One advantage is that the total decibel gain of a series of components (such as amplifiers and attenuators) can be calculated simply by summing the decibel gains of the individual components. Similarly, in telecommunications, decibels denote signal gain or loss from a transmitter to a receiver through some medium (free space, waveguide, coaxial cable, fiber optics, etc.) using a link budget. The decibel unit can also be combined with a reference level, often indicated via a suffix, to create an absolute unit of electric power. For example, it can be combined with "m" for "milliwatt" to produce the "dBm". A power level of 0 dBm corresponds to one milliwatt, and 1 dBm is one decibel greater (about 1.259 mW). In professional audio specifications, a popular unit is the dBu. This is relative to the root mean square voltage which delivers 1 mW (0 dBm) into a 600-ohm resistor, or √1 mW×600 Ω ≈ 0.775 VRMS. When used in a 600-ohm circuit (historically, the standard reference impedance in telephone circuits), dBu and dBm are identical. OpticsIn an optical link, if a known amount of optical power, in dBm (referenced to 1 mW), is launched into a fiber, and the losses, in dB (decibels), of each component (e.g., connectors, splices, and lengths of fiber) are known, the overall link loss may be quickly calculated by addition and subtraction of decibel quantities. In spectrometry and optics, the blocking unit used to measure optical density is equivalent to −1 B. Video and digital imagingIn connection with video and digital image sensors, decibels generally represent ratios of video voltages or digitized light intensities, using 20 log of the ratio, even when the represented intensity (optical power) is directly proportional to the voltage generated by the sensor, not to its square, as in a CCD imager where response voltage is linear in intensity. Thus, a camera signal-to-noise ratio or dynamic range quoted as 40 dB represents a ratio of 100:1 between optical signal intensity and optical-equivalent dark-noise intensity, not a 10,000:1 intensity (power) ratio as 40 dB might suggest. Sometimes the 20 log ratio definition is applied to electron counts or photon counts directly, which are proportional to sensor signal amplitude without the need to consider whether the voltage response to intensity is linear. However, as mentioned above, the 10 log intensity convention prevails more generally in physical optics, including fiber optics, so the terminology can become murky between the conventions of digital photographic technology and physics. Most commonly, quantities called "dynamic range" or "signal-to-noise" (of the camera) would be specified in 20 log dB, but in related contexts (e.g. attenuation, gain, intensifier SNR, or rejection ratio) the term should be interpreted cautiously, as confusion of the two units can result in very large misunderstandings of the value. Photographers typically use an alternative base-2 log unit, the stop, to describe light intensity ratios or dynamic range. Suffixes and reference valuesSuffixes are commonly attached to the basic dB unit in order to indicate the reference value by which the ratio is calculated. For example, dBm indicates power measurement relative to 1 milliwatt. In cases where the unit value of the reference is stated, the decibel value is known as "absolute". If the unit value of the reference is not explicitly stated, as in the dB gain of an amplifier, then the decibel value is considered relative. The SI does not permit attaching qualifiers to units, whether as suffix or prefix, other than standard SI prefixes. Therefore, even though the decibel is accepted for use alongside SI units, the practice of attaching a suffix to the basic dB unit, forming compound units such as dBm, dBu, dBA, etc., is not. The proper way, according to the IEC 60027-3, is either as Lx (re xref) or as Lx/xref, where x is the quantity symbol and xref is the value of the reference quantity, e.g., LE (re 1 μV/m) = LE/(1 μV/m) for the electric field strength E relative to 1 μV/m reference value. Outside of documents adhering to SI units, the practice is very common as illustrated by the following examples. There is no general rule, with various discipline-specific practices. Sometimes the suffix is a unit symbol ("W","K","m"), sometimes it is a transliteration of a unit symbol ("uV" instead of μV for microvolt), sometimes it is an acronym for the unit's name ("sm" for square meter, "m" for milliwatt), other times it is a mnemonic for the type of quantity being calculated ("i" for antenna gain with respect to an isotropic antenna, "λ" for anything normalized by the EM wavelength), or otherwise a general attribute or identifier about the nature of the quantity ("A" for A-weighted sound pressure level). The suffix is often connected with a hyphen, as in "dB‑Hz", or with a space, as in "dB HL", or with no intervening character, as in "dBm", or enclosed in parentheses, as in "dB(sm)". VoltageSince the decibel is defined with respect to power, not amplitude, conversions of voltage ratios to decibels must square the amplitude, or use the factor of 20 instead of 10, as discussed above.

AcousticsProbably the most common usage of "decibels" in reference to sound level is dB SPL, sound pressure level referenced to the nominal threshold of human hearing: The measures of pressure (a field quantity) use the factor of 20, and the measures of power (e.g. dB SIL and dB SWL) use the factor of 10.

Audio electronicsSee also dBV and dBu above.

Radar

Radio power, energy, and field strength

Antenna measurements

Other measurements

List of suffixes in alphabetical orderUnpunctuated suffixes

Suffixes preceded by a space

Suffixes within parentheses

Other suffixes

Related units

FractionsAttenuation constants, in fields such as optical fiber communication and radio propagation path loss, are often expressed as a fraction or ratio to distance of transmission. dB/m represents decibel per meter, dB/mi represents decibel per mile, for example. These quantities are to be manipulated obeying the rules of dimensional analysis, e.g., a 100-meter run with a 3.5 dB/km fiber yields a loss of 0.35 dB = 3.5 dB/km × 0.1 km. See also

References

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

, since logarithmic division is linear subtraction.

, since logarithmic division is linear subtraction.

. An

. An  Originally dBv, it was changed to dBu to avoid confusion with dBV. The "v" comes from "volt", while "u" comes from the volume unit used in the

Originally dBv, it was changed to dBu to avoid confusion with dBV. The "v" comes from "volt", while "u" comes from the volume unit used in the  . In

. In  ,

, , for a rectangular signal with the maximum amplitude

, for a rectangular signal with the maximum amplitude  . The level of a tone with a digital amplitude (peak value) of

. The level of a tone with a digital amplitude (peak value) of  .

. .

.