| Revision as of 19:42, 10 January 2007 editVanished user azby388723i8jfjh32 (talk | contribs)8,427 edits →Origins of the name← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:43, 10 January 2007 edit undoVanished user azby388723i8jfjh32 (talk | contribs)8,427 edits →Origins of the nameNext edit → | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

| Local tradition says that the Paulins Kill was named for a girl named Pauline, the daughter of a ] soldier. During the ], Hessian soldiers captured at the ] and other skirmishes within New Jersey were held as ] in the ] area. Several of these Hessians are alleged to have deserted the British and taken up residence in Stillwater because of the village's predominantly German emigrant population. The assumption is that the name Paulins Kill was derived from "Pauline's Kill."<ref>''Northwestern New Jersey--A History of Somerset, Morris, Hunterdon, Warren, and Sussex Counties'', Vol. 1. (A. Van Doren Honeyman, ed. in chief, Lewis Historical Publishing Co., New York, 1927), 499; Snell, James P. (1881) ''History of Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey, With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers''. (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1881), 379.</ref> However, the fact that the name Paulins Kill is present on maps and surveys dating from the 1740s and 1750s—two and three decades before the Revolution—negates the veracity of this tradition.<ref>Labelled "Tockhockonetkunk or Pawlings Kill" on an untitled map of Jonathan Hampton (1758) in the collection of the New Jersey Historical Society, Newark, New Jersey; also ''Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey''. . Archives of the State of New Jersey, 1st–2nd series. 47 volumes. (Newark, New Jersey, 1880–1949, passim.</ref> Further, some local traditions state that the girl's name was Pauline Snover, however extant genealogical records do not indicate that any person existed by that name at that time. | Local tradition says that the Paulins Kill was named for a girl named Pauline, the daughter of a ] soldier. During the ], Hessian soldiers captured at the ] and other skirmishes within New Jersey were held as ] in the ] area. Several of these Hessians are alleged to have deserted the British and taken up residence in Stillwater because of the village's predominantly German emigrant population. The assumption is that the name Paulins Kill was derived from "Pauline's Kill."<ref>''Northwestern New Jersey--A History of Somerset, Morris, Hunterdon, Warren, and Sussex Counties'', Vol. 1. (A. Van Doren Honeyman, ed. in chief, Lewis Historical Publishing Co., New York, 1927), 499; Snell, James P. (1881) ''History of Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey, With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers''. (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1881), 379.</ref> However, the fact that the name Paulins Kill is present on maps and surveys dating from the 1740s and 1750s—two and three decades before the Revolution—negates the veracity of this tradition.<ref>Labelled "Tockhockonetkunk or Pawlings Kill" on an untitled map of Jonathan Hampton (1758) in the collection of the New Jersey Historical Society, Newark, New Jersey; also ''Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey''. . Archives of the State of New Jersey, 1st–2nd series. 47 volumes. (Newark, New Jersey, 1880–1949, passim.</ref> Further, some local traditions state that the girl's name was Pauline Snover, however extant genealogical records do not indicate that any person existed by that name at that time. | ||

| Two other possibilities for the naming of the Paulins Kill are more likely. First, that the wife of one of the area's first ]s, Johan Peter Bernhardt (died 1748), was named Maria Paulina and that she had died prior to the first settlement at Stillwater in 1742. However, very few records are extant detailing Bernhardt's family. The second and most likely etymological origin is that the Native American name given to the mountain on the valley's western flank, ''Pahaqualong'' (also spelled ''Pahaqualin'', ''Pohoqualin'' and ''Pahaquarra'') may have been corrupted and anglicized to a spelling such as "Paulins" by early white settlers or surveyors. Pahaqualong is roughly translated as “end of two mountains with stream between”, from a combination of the words ''pe’uck'' meaning “water hole,” ''qua'' meaning “boundary,” and the suffix ''-onk'' meaning “place.”<ref>Thieme, Christopher D., ''On Crossroads and Signposts: An Etymology of Place Names in Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey''. (New York: Newcastle Press, 2007 - ''release forthcoming'') advance copies prior to release (scheduled November 2006) available, contact ; Decker, Amelia Stickney, ''That Ancient Trail'' (Trenton, New Jersey: Privately printed, 1942), 151; Anthony and Brinton, op. cit.</ref> This translation is thought to refer either to the valley of the Paulins Kill itself, or to the ]. | Two other possibilities for the naming of the Paulins Kill are more likely. First, that the wife of one of the area's first ]s, Johan Peter Bernhardt (died 1748), was named Maria Paulina and that she had died prior to the first settlement at Stillwater in 1742. However, very few records are extant detailing Bernhardt's family. The second and most likely etymological origin is that the Native American name given to the mountain on the valley's western flank, ''Pahaqualong'' (also spelled ''Pahaqualin'', ''Pohoqualin'' and ''Pahaquarra'') may have been corrupted and anglicized to a spelling such as "Paulins" by early white settlers or surveyors. Pahaqualong is roughly translated as “end of two mountains with stream between”, from a combination of the words ''pe’uck'' meaning “water hole,” ''qua'' meaning “boundary,” and the suffix ''-onk'' meaning “place.”<ref>Thieme, Christopher D., ''On Crossroads and Signposts: An Etymology of Place Names in Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey''. (New York: Newcastle Press, 2007 - ''release forthcoming'') advance copies prior to release (scheduled November 2006) available, contact ; Decker, Amelia Stickney, ''That Ancient Trail'' (Trenton, New Jersey: Privately printed, 1942), 151; Anthony and Brinton, op. cit.</ref> This translation is thought to refer either to the valley of the Paulins Kill itself, or to the ]. Local tradition does place an Indian village named ''Pahaquarra'' near the mouth of the Paulinskill which is immediately south of the Delaware Water Gap. Likewise, ] in ] derives its name from this origin.<ref>Snell, op cit., 23; Thieme, op. cit.</ref> | ||

| Local tradition does place an Indian village named ''Pahaquarra'' near the mouth of the Paulinskill. ] in ] derives its name from this origin.<ref>Snell, op cit., 23; Thieme, op. cit.</ref> | |||

| A village named ''Paulina'' located a short distance east of ] on ], is said to have been named "from the stream upon which it is located." William Armstrong, a local settler, built the first grist mill there along the river in 1768, and the village took root.<ref>Snell, op. cit., 688.</ref> | A village named ''Paulina'' located a short distance east of ] on ], is said to have been named "from the stream upon which it is located." William Armstrong, a local settler, built the first grist mill there along the river in 1768, and the village took root.<ref>Snell, op. cit., 688.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 19:43, 10 January 2007

River| Paulins Kill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Mouth | Delaware River |

| Length | 28.60 miles (46.03 km) |

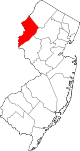

The Paulins Kill (also known as Paulinskill or Paulinskill River) is a 28.6 mile (46 km) long tributary of the Delaware River in northwestern New Jersey in the United States. It is New Jersey's third largest contributor (behind the Musconetcong River and Maurice River) to the Delaware River in terms of long-term median flow—flowing at a rate of 76 cubic feet of water per second (2.15 m³/s). The Paulins Kill drains an area of 176.85 square miles (458 km²) across portions of two counties (Sussex and Warren) consisting of eleven municipalities. The Paulins Kill, which flows southwest from its source near Newton, New Jersey, is located at the border of the Appalachians and New York-New Jersey Highlands physiographic provinces.

The Paulins Kill was a conduit for the emigration of Palatine Germans who settled in northwestern New Jersey and northeastern Pennsylvania during the colonial period and the American Revolution. Remnants of their settlement are still found in local architecture and cemeteries. The results of these settlements were chiefly agricultural, as evinced by surviving farms and mills, and the area remains largely rural to this day.

Flowing through rural sections of Sussex and Warren counties, the Paulins Kill and its surrounding valley are regarded as an excellent venue for fly fishing, hiking, other forms of recreation and observation of a multitude of species of birds and other wildlife.

Geography and geology

Course

The Paulins Kill, itself a tributary of the Delaware River, is fed by several mountain streams—many of which are unnamed. However, several larger named streams contribute their waters to the Paulinskill at various points along its 28.6-mile (46 km) length. The river emanates from two branches that merge near the hamlet of Augusta, in Frankford Township, New Jersey.

The main, or eastern, branch of the Paulins Kill begins immediately north and west of Newton, New Jersey in the marshes that straddle both Newton and the northern reaches of Fredon Township. Moore's Brook is one of several small mountain streams, some beginning at small ponds, that enter the Paulins Kill near its source. The river flows northward into Lafayette Township before curving west where it meets with the combined waters of the Culver Brook (also known as the Western branch of the Paulins Kill) and the Dry Brook near the hamlet of Augusta in Frankford Township. The Culver Brook begins at Culver's Lake, in the western portion of Frankford Township and flows east through Branchville before the two branches merge.

The Paulins Kill then flows southwest for the rest of its journey, through Hampton and Stillwater Townships in Sussex County. The Trout Brook, which rises on Kittatinny Mountain, flows into the Paulins Kill near Middleville in Stillwater Township. Swartswood Lake feeds the Trout Brook through Keen's Mill Brook. The Paulins Kill continues its course southwest, entering Warren County, where it initially forms the border between Frelinghuysen and Hardwick Townships. It enters Blairstown immediately after, where it is joined by Blair Creek named (as is the town) for John Insley Blair (1802–1899), as well as Jacksonburg Creek, Dilts Creek and Walnut Creek. Yard's Creek, which rises at the Yard's Creek reservoir in Blairstown, enters the Paulins Kill near the hamlet of Hainesburg in Knowlton Township. Finally, in Warren County its waters enter the Delaware River just south of the Delaware Water Gap at the hamlet of Columbia in Knowlton Township.

A dam was built in the 1920s across the Paulins Kill in Stillwater Township, to create Paulinskill Lake, a narrow, 3-mile (4.8 km) long body of water that stretches back into Hampton Township to the north. It was constructed in response to the 1914 establishment of Swartswood State Park, to provide seasonal (summer) housing and recreation for vacationers from the New York metropolitan area. At present, it is a year-round residential community managed by a homeowners association.

Today, several dams and mill races remain from the grist, saw, oil and fulling mills built along the river's banks during the 18th and 19th century, and continue to alter the course and flow of the river.

Valley and watershed

The valley and watershed of the Paulins Kill is bordered on the west by the Kittatinny Ridge of the Appalachians. Kittatinny Mountain, which is a segment of the Blue Ridge chain of the Appalachians, has been known historically as Schawangunk Mountain (as it is known north of the New York-New Jersey border), or Pahaqualong Mountain. Beginning at the western boundary of the Paulins Kill valley and extending westward to the Delaware River (and beyond that to the Allegheny Mountains), is the Ridge and Valley physiographic province, one of four physiographic provinces of New Jersey. This area was largely formed through the fold-and-thrust action 300 million years ago during the Alleghenian orogeny. The valley floor and its eastern boundary largely constitute the northwesternmost reaches of the New York-New Jersey Highlands region—a geological formation composed primarily of pre-Cambrian igneous and metamorphic rock—within New Jersey. Elevations within the Highlands region separate the Paulins Kill watershed from the watersheds of the Pequest River and Musconetcong River located a few miles to the east.

The Paulins Kill and its watershed share the Mamakating valley with Papakating Creek, which flows northward to the Wallkill River and is a part of the Hudson River watershed. Historically, this valley was often called "Mamakating", from the Lenape for "valley of the divided waters"—however, this name has fallen into disuse in the latter half of the 20th century. At their closest, the Papakating Creek and Paulins Kill flow within one mile of each other, in Frankford Township in Sussex County.

History

Origins of the name

The United States Geological Survey Board of Geographic Names decided that the official spelling of the name would be Paulins Kill in 1898. Other spellings (Pawlins Kill or Paulinskill) have remained in common use. The use of Paulinskill River, however—while often used—is redundant as Kill is a geographic designation for a small stream or creek, derived from Dutch.

Local tradition says that the Paulins Kill was named for a girl named Pauline, the daughter of a Hessian soldier. During the American Revolution, Hessian soldiers captured at the Battle of Trenton and other skirmishes within New Jersey were held as prisoners of war in the Stillwater, New Jersey area. Several of these Hessians are alleged to have deserted the British and taken up residence in Stillwater because of the village's predominantly German emigrant population. The assumption is that the name Paulins Kill was derived from "Pauline's Kill." However, the fact that the name Paulins Kill is present on maps and surveys dating from the 1740s and 1750s—two and three decades before the Revolution—negates the veracity of this tradition. Further, some local traditions state that the girl's name was Pauline Snover, however extant genealogical records do not indicate that any person existed by that name at that time.

Two other possibilities for the naming of the Paulins Kill are more likely. First, that the wife of one of the area's first settlers, Johan Peter Bernhardt (died 1748), was named Maria Paulina and that she had died prior to the first settlement at Stillwater in 1742. However, very few records are extant detailing Bernhardt's family. The second and most likely etymological origin is that the Native American name given to the mountain on the valley's western flank, Pahaqualong (also spelled Pahaqualin, Pohoqualin and Pahaquarra) may have been corrupted and anglicized to a spelling such as "Paulins" by early white settlers or surveyors. Pahaqualong is roughly translated as “end of two mountains with stream between”, from a combination of the words pe’uck meaning “water hole,” qua meaning “boundary,” and the suffix -onk meaning “place.” This translation is thought to refer either to the valley of the Paulins Kill itself, or to the Delaware Water Gap. Local tradition does place an Indian village named Pahaquarra near the mouth of the Paulinskill which is immediately south of the Delaware Water Gap. Likewise, Pahaquarry Township in Warren County derives its name from this origin.

A village named Paulina located a short distance east of Blairstown, New Jersey on Route 94, is said to have been named "from the stream upon which it is located." William Armstrong, a local settler, built the first grist mill there along the river in 1768, and the village took root.

The Paulins Kill was originally known as the Tockhockonetcong by the local Native Americans who were likely Munsee, a tribe or phratry of the Lenni Lenape. The name Tockhockonetcong (or Tockhockonetcunk) roughly translates to "stream that comes from Tok-Hok-Nok"—Tok-hok-nok being an Indian village believed to been within the boundaries of present-day Newton, New Jersey, near which the eastern (main) branch of the Paulins Kill begins, and the Lenape roots hannek meaning "stream" and the suffix -ong denoting "place."

Early settlement

The first human settlement along the Paulins Kill was by early Native Americans circa 8,000–10,000 BC at the close of the last ice age (known as the Wisconsin glaciation). At the time of the first settlement by emigrating Europeans in this region, it was populated by the Munsee tribe of the Lenni Lenape (or Delaware) Indians. Artifacts (often of stone, clay or bone) of the Native American culture are often found in nearby farm fields and at the site of their ancient villages.

Typically, early European settlement along the Paulins Kill was by Palatine Germans who had emigrated to the New World via the port of Philadelphia from 1720 to 1800. Many had treked north through the valley of the Delaware and settled along the Musconetcong, Pequest and Paulins Kill valleys in New Jersey and along the Lehigh River valley in Pennsylvania. Areas along the Paulins Kill generally were not settled until the 1740s and 1750s. Often villages established and settled by German emigrants remained culturally German well into the Nineteenth Century, with German Lutheran and Reformed churches (often as "Union" churches) established shortly after the first settlements (as was the case in Knowlton and in Stillwater). However, by the early Nineteenth Century, many descendants of these German settlers removed to newly-opened lands in the West (i.e. Ohio, the Northwest Territory, the Southern Tier of New York) and those that remained had assimilated into English-speaking culture, and the German Reformed or Lutheran Churches often became Presbyterian. The German cultural impact of this community can still be seen in local architecture—most notably in barns and in stone houses—and in cemeteries containing intricately-carved gravestones often bearing archaic German text and funerary symbols. English, Scottish, Welsh settlers located in the Paulins Kill valley throughout the latter-half of the eighteenth century, often travelling north from Philadelphia, or west from Long Island, Newark, and Elizabethtown (now Elizabeth).

The area around present-day Stillwater was first settled by the family of Casper Shafer (1712–1784), a Palatine German who had emigrated to Philadelphia a few years earlier. Shafer, with his father-in-law, Johan Peter Bernhardt (?–1748), and his brother-in-law Johann Georg Windemuth (or John George Wintermute) (1711–1782), settled at Stillwater in 1742. Both Shafer and Windemuth were married to Bernhardt's daughters. Shafer, who operated a grist mill at Stillwater starting in 1746, transported flour, fruit, and other products by flatboat down the Paulins Kill and the Delaware River to the market in Philadelphia. Most of the New Jersey shoreline and cities such as Elizabethtown and Newark were practically unknown to the German settlers along the Paulins Kill who learned of the existence of these cities only through trade with the local Lenni Lenape. Part of this was because of the incredible hardship of an overland journey east to these cities resulting from a lack of roads.

The first road connecting Elizabethtown, and Morristown with settlements along the Delaware River, was the Military Road built by Jonathan Hampton (1711–1777) in 1755–1756. This road, which crosses the Paulins Kill at present-day Baleville, in Hampton Township, was built to supply fortifications built in the Delaware valley at this time to protect New Jersey during the French and Indian War. Very few passable, large roads were built in this section of New Jersey, then largely a sparsely-populated wilderness, before the creation of turnpike companies in the early decades of the Nineteenth Century. During much of the mid-eighteenth century, trade in the northwestern reaches of New Jersey was conducted through Philadelphia by way of the Delaware River.

About the year 1760, Mark Thomson (1739–1803) settled in Hardwick Township (now Frelinghuysen Township) and erected a gristmill and sawmill on the Paulins Kill. The settlement that arose was later named Marksboro in his honour. Thomson, who removed to Changewater in Hunterdon County, became an officer in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, and served two terms in the House of Representatives.

Commercial and industrial impact

From the standpoint of conservation, the Paulins Kill has benefited from having remained chiefly a pastoral river in a largely undeveloped area of New Jersey. No significant industry had developed since the 1740s to cause irreversible damage to the flow of the river or to heavily pollute its waters. During this time, the river was dammed to provide power to the only industries established in these small rural towns: grist, saw, oil, and fulling mills. Many of the dams that once powered the mills, and the electrical power plant at Branchville established in 1903, have been breached, or no longer impede the flow of the river.

Columbia, a hamlet near the mouth of the Paulins Kill in Knowlton Township, was known for a large glass manufacturing factory. Near Columbia, the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad also constructed the Paulinskill Viaduct (known also as the Hainesburg Viaduct), a bridge crossing the Paulins Kill along the Lackawanna Cut-Off rail corridor. Begun in 1908, this bridge was deemed an engineering marvel for its use of reinforced concrete. Spanning 1,100 feet (335 m) across the Paulins Kill Valley, the Viaduct rises 115 feet (35 m) above the valley floor, and opened for rail traffic in 1911. It was the largest such viaduct in the world until 1915, when the Lackawanna Railroad opened the Tunkhannock Viaduct in Nicholson, Pennsylvania spanning over twice the Paulinskill Viaduct's length. Currently abandoned, several plans are underway by New Jersey Transit to open the route as a passenger line to Scranton, Pennsylvania. This site is commonly visited by adventure-seeking individuals. Today Interstate 80 crosses the Paulins Kill near Columbia.

However, despite its rural character, the Paulins Kill is still impacted by pollution, chiefly through nearby residential developments and farm run-off (agricultural pesticides and fertilizers), known as "non-point pollution." Several farms are located along the banks of the Paulins Kill, raising crops including such grain-producing grasses as alfalfa, wheat, corn, hay (and historically barley, buckwheat and rye). Fruit trees in orchards produce cherries, apple, plum, peach and pear, while native wild grape vines, and Blackberry bushes are also found in the valley.

The New Jersey Public Interest Research Group (NJPIRG) has ranked the Paulins Kill as the seventh in a collection of rivers and creeks in a Top 30 listing of New Jersey waterways to Save Also, New Jersey's Department of Environmental Protection often brings civil actions against local firms that deliberately pollute in the Paulins Kill watershed, most recently levying a $121,500 fine against a Sussex County shopping mall owner who discharged pollutants from a sewage treatment facility into the main branch near Newton, New Jersey between 1996 and 1998.

Recent development, prompted by an enlarging New York City Metropolitan area, has lead to development issues which could threaten the Paulins Kill's future. A public sewer and water project in Branchville, New Jersey was halted in the 2000 out of concern for a population of Dwarf wedgemussels (Alasmidonta heterodon), an endangered species. This project was reauthorized in 2002. The Paulins Kill is also home to a wide variety of amphibians, including the Spotted Salamander, Red Spotted Newt, American Toad, Fowlers Toad, American Bull Frog and others.

Today

The Paulins Kill continues to maintain its rural character through both local concern and government policy. It is an excellent area for birdwatching, canoeing, hiking, hunting and fishing, and is considered to be one of the best trout streams in New Jersey. As in the past, the Paulins Kill Valley remains rural, and the landscape is dotted with many horse and dairy farms along its entire length.

Fishing

The Paulins Kill is a popular fishing destination for various species of trout—mostly Rainbow Trout, Brown Trout and Brook Trout—many of which are stocked each year during fishing season by New Jersey's Division of Fish & Wildlife, while others are found wild. The river owes its fly fishing reputation largely to the prolific populations of various species of the mayfly and caddisfly. Historically, the Paulins Kill was known to be populated with American Shad, but with the construction of mill dams across the river in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the population of Shad were unable to spawn in the river. Shad can still be found in the Delaware River.

Protected areas

The Paulins Kill valley contains many protected areas. Swartswood State Park, established in 1914 as the first and oldest state park in New Jersey, is on 2,272 acres (919 ha) just north of the Paulins Kill Lake in Sussex County. Along Kittatinny Ridge in the northern part of the watershed are parts of Worthington State Forest (west), Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area (central), and Stokes State Forests (east). In addition to these state forests, the Paulins Kill valley is host to a variety of common coniferous and deciduous trees, which have been harvested for lumber in the past, including: White and Black Oak, Buttonwood, Eastern Red Cedar, Eastern Hemlock, American Chestnut, Black Walnut, Tamarack Larch, Spruce, and Pine. Trees that add to the beauty of the fall foliage include Maple, Birch, Hickory, Elm, and Crab Apple.

New Jersey's Green Acres program has targeted the Paulins Kill and its surrounding valley as an excellent natural resources for open space and farmland preservation and recreational opportunities. The state, working together with agricultural development boards in Sussex and Warren Counties, and with the Ridge and Valley Conservancy, a local nonprofit land trust, share land acquisition costs to enter tracts of real estate into the program. Since 1983, several farms across New Jersey have sold development rights to the county programs. Sussex County has permanently preserved 12,242.39 acres (4,954.32 ha) of woodland and farmland. Likewise, Warren County has preserved 100 farm properties, comprising over 12,200 acres (4,937 ha).

In addition, four Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs) are in the Paulins Kill valley: Bear Swamp WMA, Trout Brook WMA, White Lake WMA, and Columbia Lake WMA. Together they comprise 6,564 acres (2656 ha) of protected lands, mostly acquired through "Green Acres" funds. Hunting and trapping are permitted in season in many of these protected areas. Common game animals include White-tailed Deer, Eastern Coyote, Red Fox, Gray Fox, Opossum, Eastern Cottontail Rabbit, Raccoon, Gray and Red Squirrel, Beaver, Muskrat, andWoodchuck or Groundhog. Common game birds include Ring-necked Pheasant, Eastern Wild Turkey, American Crow, and Canada Goose.

The Paulins Kill watershed is home to a variety of other animals. Other mammals include Eastern Chipmunk, Porcupine, Black Bear, Striped Skunk, River Otter, and Bobcat. Common northeastern American reptiles found there include snakes such as the American Copperhead, Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake, Northern Water Snake, Common Garter Snake and Milk Snake, and turtles, including the Eastern Box Turtle, and Snapping Turtle.

Hiking

The Paulinskill Valley Trail —a network of trails along abandoned railroad beds of the New York, Susquehanna and Western Railroad—have been transformed and maintained for hiking, horseback riding, and other recreational uses, stretches for 27 miles (44 km) from Sparta Junction in Sussex County to Columbia in Warren County, roughly following the entire length of the river. After the New York, Susquehanna and Western decommissioned the route in 1962, the right-of-way along this corridor was purchased by the City of Newark the following year. Newark hoped to use the bed for a water pipeline connecting to the proposed dam and reservoir project on the Delaware River. However, this project—controversial from the start because of environmental concerns and the federal government's abuse of eminent domain—was cancelled during the 1970s. Newark sold their claim to the corridor in 1992 to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection for $600,000, and the Paulinskill Valley Trail was created. The Appalachian Trail follows the top of Kittatiny Ridge at the northern edge of the valley.

Birdwatching

Birdwatchers have sighted a variety of common and endangered species of birds that inhabit the Paulins Kill valley. More common species include: American Robin, Barn Swallow, Field Sparrow, Blue Jay, Black-capped Chickadee, Northern Cardinal, Red-winged Blackbird and the American Goldfinch. Also sighted are several species of Woodpecker, including Red-headed, Red-bellied, and Downy, and the endangered Pileated Woodpecker, as well as the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker. Often sighted are water fowl such as the Mute Swan, the Wood Duck, and the Mallard, wading birds such as the Killdeer, and predators such as the Red-tailed Hawk. More rare birds sighted in the Paulins Kill valley include: Purple martin, Scarlet Tanager, Indigo Bunting, Baltimore Oriole, Purple Finch, and a variety of owls, notably the Barn, Eastern Screech, Great Horned, Snowy, Barred, and Northern Saw-whet Owl.

In art, literature and popular culture

- Essayist, poet and children's author Aline Murray Kilmer (1886–1941), the widow of poet Joyce Kilmer (1886–1918) resided in Stillwater, New Jersey for the last thirteen years of her life. Located along the Paulins Kill, her home, "Whitehall," was built in 1785 by Abraham Shafer (1754–1820), son of Casper Shafer. The setting of her children's book, A Buttonwood Summer (1929), was inspired by Stillwater and the Paulins Kill Valley.

- The 1980 slasher film Friday the 13th was filmed at Camp NoBeBosCo north of Blairstown, New Jersey in Hardwick Township. The camp's Sand Pond, which stood in for the movie's "Crystal Lake," feeds the Jacksonburg Creek, a tributary of the Paulins Kill.

- Artist and Queens College professor Louis Finkelstein (1923–2000) created a painting entitled Trees at Paulinskill (c.1991–97) that was among his later pastel works and critically compared to works by French artist and Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne (1839–1906).

See also

- Geography of New Jersey

- History of New Jersey

- Kittatinny Valley State Park

- List of New Jersey rivers

- New Jersey

- Paulinskill Viaduct

- Swartswood State Park

Resources and external links

Notes and citations

- HCDN: Streamflow Data Set, 1874 - 1988 by J.R. Slack, Alan M. Lumb, and Jurate Maciunas Landwehr in USGS Water-Resources Investigations Report 93-4076, accessed 24 August 2006.

- HCDN: Streamflow Data Set, 1874 - 1988 by J.R. Slack, Alan M. Lumb, and Jurate Maciunas Landwehr in USGS Water-Resources Investigations Report 93-4076, accessed 24 August 2006.

- USGS National Water Information System: Web Interface - Real-Time Data for New Jersey: Streamflow no further authorship information given, accessed 24 August 2006.

- Watershed Reference Map from Flood Insurance Claims in the Delaware River Basin: Comparative Analysis of Flood Insurance Claims in the Delaware River Basin, September 2004 and April 2005 Floods, no further authoriship information given, accessed 24 August 2006.

- USGS National Water Information System: Web Interface - Real-Time Data for New Jersey: Streamflow no further authorship information given, accessed 30 October 2006.

- USGS Geographic Names Information System Feature Detail Report, no further authorship information given, accessed 16 December 2006.

- USGS Geographic Names Information System Feature Detail Report, no further authorship information given, accessed 16 December 2006.

- "Stillwater" by Jane Dobosh at Skylands Magazine website, accessed 29 October 2006.

- United States Geological Survey topographical map, "Newton East" and "Newton West"

- Appalachian Mountains GO 568 Structural Geology at Emporia State University by James S. Aber, accessed 16 September 2006.

- Significant Habitats and Habitat Complexes of the New York Bight Watershed: New York-New Jersey Highlands, Complex #25 from U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, no further authorship information given, accessed 16 December 2006.

- Hagstrom Morris/Sussex/Warren counties atlas (Maspeth, New York: Hagstrom Map Company, Inc. 2004); United States Geological Survey topographical map, "Newton East" and "Newton West"

- Thieme, op. cit.

- Hagstrom Morris/Sussex/Warren counties atlas (Maspeth, New York: Hagstrom Map Company, Inc. 2004).

- USGS Geographic Names Information System Feature Detail Report, no further authorship information given, accessed 24 August 2006.

- Northwestern New Jersey--A History of Somerset, Morris, Hunterdon, Warren, and Sussex Counties, Vol. 1. (A. Van Doren Honeyman, ed. in chief, Lewis Historical Publishing Co., New York, 1927), 499; Snell, James P. (1881) History of Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey, With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1881), 379.

- Labelled "Tockhockonetkunk or Pawlings Kill" on an untitled map of Jonathan Hampton (1758) in the collection of the New Jersey Historical Society, Newark, New Jersey; also Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey. . Archives of the State of New Jersey, 1st–2nd series. 47 volumes. (Newark, New Jersey, 1880–1949, passim.

- Thieme, Christopher D., On Crossroads and Signposts: An Etymology of Place Names in Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey. (New York: Newcastle Press, 2007 - release forthcoming) advance copies prior to release (scheduled November 2006) available, contact ; Decker, Amelia Stickney, That Ancient Trail (Trenton, New Jersey: Privately printed, 1942), 151; Anthony and Brinton, op. cit.

- Snell, op cit., 23; Thieme, op. cit.

- Snell, op. cit., 688.

- Snell, op. cit., 23.

- Thieme, op. cit.; Anthony, A. S., Rev. and Brinton, Daniel G. Lenape-English Dictionary. (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1883).

- Schrabisch, Max. Indian habitations in Sussex County, New Jersey Geological Survey of New Jersey, Bulletin No. 13. (Union Hill, New Jersey: Dispatch Printing Company, 1915); and Archaeology of Warren and Hunterdon counties Geological Survey of New Jersey, Bulletin No. 18. (Trenton, N.J., MacCrellish and Quigley co., state printers, 1917).

- Chambers, Theodore Frelinghuysen. The early Germans of New Jersey: Their History, Churches, and Genealogies. (Dover, New Jersey, Dover Printing Company, 1895), passim.

- Schaeffer, Capser, M.D. and Johnson, William M. Memoirs and Reminiscences: Together with Sketches of the Early History of Sussex County, New Jersey. (Hackensack, New Jersey: Privately Printed, 1907). 42–43, 46–47; Chambers, op. cit., passim.

- Viet, Richard F. "John Solomon Teetzel and the Anglo-German Gravestone Carving Tradition of 18th century Northwestern New Jersey" in Markers XVII (Richard E. Meyer, ed.), Journal of the Association for Gravestone Studies, XVII: 124-161 (2000).

- Schaeffer, Capser, M.D. and Johnson, William M. Memoirs and Reminiscences: Together with Sketches of the Early History of Sussex County, New Jersey. (Hackensack, New Jersey: Privately Printed, 1907). passim.; Snell, op. cit., passim.; Armstrong, William C. Pioneer Families of Northwestern New Jersey (Lambertville, New Jersey: Hunterdon House, 1979), passim; Stickney, Charles E. Old Sussex County families of the Minisink Region from articles in the Wantage Recorder (compiled by Virginia Alleman Brown) (Washington, N.J. : Genealogical Researchers, 1988), passim.

- Wintermute, Jacob Perry. Wintermute Family History. (Columbus, Ohio: Champlin Press, 1900); Wintermute, Leonard. Windemuth Family Heritage. (Baltimore, Maryland: Gateway Press, 1996).

- Schaeffer and Johnson. op. cit., 33.; Snell, op. cit., passim.

- Military Trail at Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area website, no further authorship information given, accessed 29 October 2006.

- Schaeffer and Johnson, loc. cit.

- Snell, op. cit., passim.

- Snell, op. cit., passim.

- Branchville, New Jersey - History, no further authoriship information given, accessed 29 October 2006.

- Cunningham, John T. Railroad Wonder: The Lackawanna Cut-Off (Newark, New Jersey: Newark Sunday News, 1961). NO ISBN

- Richman, Steven M. The Bridges Of New Jersey: Portraits Of Garden State Crossings (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2005). ISBN 0-8135-3510-7

- "Touring the Lackawanna Cut-Off" by Don Barnicle and Paula Williams in Skylands Magazine, accessed 29 October 2006.

- History and Heritage of Civil Engineering: "Tunkhannock Viaduct" at the American Society of Civil Engineers website (ASCE.org), accessed 29 October 2006.

- Lackawanna Cutoff Project, New Jersey Transit, (www.NJTransit.com), no further authorship information given, (April 2005), accessed 29 October 2006.

- Weird New Jersey Magazine, 2001 Weekly Story Archives, by "Myke L.", no further authorship information given, accessed 29 October 2006.

- Schaeffer and Johnson, loc. cit.

- Defend New Jersey Waters Releases List Of Top 30 Waterways To Save (Press Release), 21 November 2001 at the NJPIRG website, no further authorship information given, accessed 29 October 2006.

- NJ DEP Attains Settlement Over Water Pollution Violations affecting Paulinskill River (Press Release) at NJDEP website, no further authorship information given, accessed 29 October 2006.

- "Branchville Sewer Plant May Still Be Built" by Jamie Goldenbaum in New Jersey Herald (16 April 2002), transcribed at http://www.srk.hk/i/news/activist/part1/branchville-sewer-plant-may-built.asp?command=viewArticleBasic&articleId=4620, accessed 29 October 2006.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Division of Fish and Wildlife: Amphibians of New Jersey, no further authorship information given, accessed 20 December 2006.

- "Trout Fishing in New Jersey - The Good 'Ole Days are Now!" by Jim Sciascia at New Jersey Division of Fish & Wildlife website, accessed 29 October 2006.

- Music to a Hare's Ears by Henry Bell in Skylands Magazine, accessed 29 October 2006.

- Cummings, Warren D. Sussex County: A History (Newton, New Jersey: Newton Rotary Club, 1964). transcribed http://archiver.rootsweb.com/th/read/NJSUSSEX/2002-09/1032918263, accessed 26 October 2006.

- Fishing for Shad on the Delaware at Delaware River Recreation, no further authorship information given, accessed 29 October 2006.

- Swartswood State Park, official website, no further authorship information given, accessed 20 December 2006

- Worthington State Forest, official website, no further authorship information given, accessed 20 December 2006

- National Park Service: Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, official website, no further authorship information given, accessed 20 December 2006

- Stokes State Forest, official website, no further authorship information given, accessed 20 December 2006

- Schaeffer and Johnson, op. cit., 45 ff.

- State Acquisitions Current Projects, Green Acres Program, NJ Department of Environmental Protection no further authorship information given, accessed 24 August 2006.

- Preserved Farmland in Sussex County (NJ), spreadsheet from the County of Sussex (New Jersey) no further authorship information given, accessed 30 October 2006.

- Preserved Farms in Warren County Hit 100 (2004 Press Release) Warren County (NJ), no further authorship information given, accessed 30 October 2006.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Wildlife Management Areas, no further authorship information given, accessed 20 December 2006.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Division of Fish and Wildlife: Small Game Hunting in New Jersey, no further authorship information given, accessed 20 December 2006.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Division of Fish and Wildlife: Mammals of New Jersey, no further authorship information given, accessed 20 December 2006.

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Division of Fish and Wildlife: Reptiles of New Jersey, no further authorship information given, accessed 20 December 2006.

- Paulinskill Valley Trail at Rails-to-Trail Conservancy, no further authorship information given, accessed 24 August 2006.

- Worthington State Forest, official website, no further authorship information given, accessed December 20 2006

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Division of Fish and Wildlife: Birds of New Jersey, no further authorship information given, accessed 20 December 2006.

- Letter from Kenton Kilmer to Aline Kilmer (addressed to c/o Bob Holliday), 18 November 1929. quoted in Hillis, John. Joyce Kilmer: A Bio-Bibliography. Master of Science (Library Science) Thesis. Catholic University of America. (Washington, DC: 1962). NO ISBN.

- Friday the 13th Filming Locations, no further authorship information given, accessed 16 December 2006.

- Gael Mooney on Finkelstein, accessed 21 December 2006.

- "Louis Finkelstein: The Late Pastels in the Context of His Artistic Thinking" at Lori Bookstein Fine Art, accessed 21 December 2006.

Books and printed materials

- Armstrong, William C. Pioneer Families of Northwestern New Jersey (Lambertville, New Jersey: Hunterdon House, 1979). NO ISBN (Privately printed).

- Cawley, James S. and Cawley, Margaret. Exploring the Little Rivers of New Jersey (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1942, 1961, 1971, 1993). ISBN 0-8135-0684-0

- Chambers, Theodore Frelinghuysen. The early Germans of New Jersey: Their History, Churches, and Genealogies (Dover, New Jersey, Dover Printing Company, 1895). NO ISBN (Pre-1964)

- Cummings, Warren D. Sussex County: A History (Newton, New Jersey: Newton Rotary Club, 1964). NO ISBN (Privately printed).

- Cunningham, John T. Railroad Wonder: The Lackawanna Cut-Off (Newark, New Jersey: Newark Sunday News, 1961). NO ISBN (Pre-1964).

- Documents Relating to the Colonial, Revolutionary and Post-Revolutionary History of the State of New Jersey . Archives of the State of New Jersey, 1st-2nd series. 47 volumes. (Newark, New Jersey: 1880-1949). NO ISBN (pre-1964)

- Gleason, June Benore. Historical Paulinskill Valley, New Jersey: Blairstown's neighbors. (Blairstown, New Jersey: Blairstown Press, 1949). NO ISBN (Pre0-1964)

- Honeyman, A. Van Doren (ed.). Northwestern New Jersey--A History of Somerset, Morris, Hunterdon, Warren, and Sussex Counties Volume 1. (Lewis Historical Publishing Co., New York, 1927). NO ISBN (pre-1964)

- Richman, Steven M. The Bridges Of New Jersey: Portraits Of Garden State Crossings. (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2005). ISBN 0-8135-3510-7

- Schaeffer, Casper M.D. (and Johnson, William M.). Memoirs and Reminiscences: Together with Sketches of the Early History of Sussex County, New Jersey. (Hackensack, New Jersey: Privately Printed, 1907). NO ISBN (Pre-1964)

- Schrabisch, Max. Indian habitations in Sussex County, New Jersey Geological Survey of New Jersey, Bulletin No. 13. (Union Hill, New Jersey: Dispatch Printing Company, 1915). NO ISBN (Pre-1964)

- Schrabisch, Max. Archaeology of Warren and Hunterdon counties Geological Survey of New Jersey, Bulletin No. 18. (Trenton, N.J., MacCrellish and Quigley co., state printers, 1917). NO ISBN (Pre-1964)

- Snell, James P. History of Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey, With Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1881). NO ISBN (Pre-1964)

- Stickney, Charles E. Old Sussex County families of the Minisink Region from articles in the Wantage Recorder (compiled by Virginia Alleman Brown) (Washington, N.J. : Genealogical Researchers, 1988). NO ISBN (Privately printed).

- Thieme, Christopher D., On Crossroads and Signposts: An Etymology of Place Names in Sussex and Warren Counties, New Jersey. (New York: Newcastle Press, 2006). ISBN Pending

- Viet, Richard F. "John Solomon Teetzel and the Anglo-German Gravestone Carving Tradition of 18th century Northwestern New Jersey" in Markers XVII (Richard E. Meyer, ed.), Journal of the Association for Gravestone Studies, XVII: 124-161 (2000).

- Wintermute, Jacob Perry. Wintermute Family History. (Columbus, Ohio: Champlin Press, 1900). NO ISBN. (Pre-1964)

- Wintermute, Leonard. Windemuth Family Heritage. (Baltimore, Maryland: Gateway Press, 1996). NO ISBN (Privately printed).

Maps and atlases

- Map of Jonathan Hampton (1758) in the collection of the New Jersey Historical Society, Newark, New Jersey.

- Hopkins, Griffith Morgan. Map of Sussex County, New Jersey. (1860)

- Beers, Frederick W. County Atlas of Warren, New Jersey: From actual surveys by and under the direction of F. W. Beers (New York: F.W. Beers & Co. 1874). .

- Hagstrom Morris/Sussex/Warren counties atlas (Maspeth, New York: Hagstrom Map Company, Inc. 2004).

- United States Geological Survey topographical map "Newton East" and "Newton West" (New Jersey).

External links

- Ridge and Valley Conservancy

- Paulinskill Valley Trail Committee

- Map of The Paulinskill

- U.S. Geological Survey: NJ stream flow-gauging stations

| Municipalities and communities of Sussex County, New Jersey, United States | ||

|---|---|---|

| County seat: Newton | ||

| Boroughs |  | |

| Town | ||

| Townships | ||

| CDPs | ||

| Other communities | ||

| Footnotes | ‡This populated place also has portions in an adjacent county or counties | |

| Municipalities and communities of Warren County, New Jersey, United States | ||

|---|---|---|

| County seat: Belvidere | ||

| Boroughs |  | |

| Towns | ||

| Townships | ||

| CDPs |

| |

| Other unincorporated communities | ||