This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Itz.mas10 (talk | contribs) at 11:00, 7 October 2024 (→Type J: components of the wire). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 11:00, 7 October 2024 by Itz.mas10 (talk | contribs) (→Type J: components of the wire)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Electrical device for measuring temperature via two dissimilar metals connected at two points

| Thermoelectric effect |

|---|

|

Principles

|

| Applications |

A thermocouple, also known as a "thermoelectrical thermometer", is an electrical device consisting of two dissimilar electrical conductors forming an electrical junction. A thermocouple produces a temperature-dependent voltage as a result of the Seebeck effect, and this voltage can be interpreted to measure temperature. Thermocouples are widely used as temperature sensors.

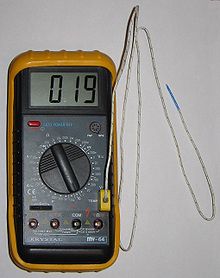

Commercial thermocouples are inexpensive, interchangeable, are supplied with standard connectors, and can measure a wide range of temperatures. In contrast to most other methods of temperature measurement, thermocouples are self-powered and require no external form of excitation. The main limitation with thermocouples is accuracy; system errors of less than one degree Celsius (°C) can be difficult to achieve.

Thermocouples are widely used in science and industry. Applications include temperature measurement for kilns, gas turbine exhaust, diesel engines, and other industrial processes. Thermocouples are also used in homes, offices and businesses as the temperature sensors in thermostats, and also as flame sensors in safety devices for gas-powered appliances.

Principle of operation

In 1821, the German physicist Thomas Johann Seebeck discovered that a magnetic needle held near a circuit made up of two dissimilar metals got deflected when one of the dissimilar metal junctions was heated. At the time, Seebeck referred to this consequence as thermo-magnetism. The magnetic field he observed was later shown to be due to thermo-electric current. In practical use, the voltage generated at a single junction of two different types of wire is what is of interest as this can be used to measure temperature at very high and low temperatures. The magnitude of the voltage depends on the types of wire being used. Generally, the voltage is in the microvolt range and care must be taken to obtain a usable measurement. Although very little current flows, power can be generated by a single thermocouple junction. Power generation using multiple thermocouples, as in a thermopile, is common.

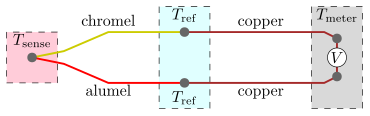

The standard configuration of a thermocouple is shown in the figure. The dissimilar conductors contact at the measuring (aka hot) junction and at the reference (aka cold) junction. The thermocouple is connected to the electrical system at its reference junction. The figure shows the measuring junction on the left, the reference junction in the middle and represents the rest of the electrical system as a voltage meter on the right.

The temperature Tsense is obtained via a characteristic function E(T) for the type of thermocouple which requires inputs: measured voltage V and reference junction temperature Tref. The solution to the equation E(Tsense) = V + E(Tref) yields Tsense. Sometimes these details are hidden inside a device that packages the reference junction block (with Tref thermometer), voltmeter, and equation solver.

Seebeck effect

Main article: Seebeck effectThe Seebeck effect refers to the development of an electromotive force across two points of an electrically conducting material when there is a temperature difference between those two points. Under open-circuit conditions where there is no internal current flow, the gradient of voltage () is directly proportional to the gradient in temperature ():

where is a temperature-dependent material property known as the Seebeck coefficient.

The standard measurement configuration shown in the figure shows four temperature regions and thus four voltage contributions:

- Change from to , in the lower copper wire.

- Change from to , in the alumel wire.

- Change from to , in the chromel wire.

- Change from to , in the upper copper wire.

The first and fourth contributions cancel out exactly, because these regions involve the same temperature change and an identical material. As a result, does not influence the measured voltage. The second and third contributions do not cancel, as they involve different materials.

The measured voltage turns out to be

where and are the Seebeck coefficients of the conductors attached to the positive and negative terminals of the voltmeter, respectively (chromel and alumel in the figure).

Characteristic function

The thermocouple's behaviour is captured by a characteristic function , which needs only to be consulted at two arguments:

In terms of the Seebeck coefficients, the characteristic function is defined by

The constant of integration in this indefinite integral has no significance, but is conventionally chosen such that .

Thermocouple manufacturers and metrology standards organizations such as NIST provide tables of the function that have been measured and interpolated over a range of temperatures, for particular thermocouple types (see External links section for access to these tables).

Reference junction

To obtain the desired measurement of , it is not sufficient to just measure . The temperature at the reference junctions must also be known. Two strategies are often used here:

- "Ice bath": The reference junction block is maintained at a known temperature as it is immersed in a semi-frozen bath of distilled water at atmospheric pressure. The precise temperature of the melting point phase transition acts as a natural thermostat, fixing to 0 °C.

- Reference junction sensor (known as "cold junction compensation"): The reference junction block is allowed to vary in temperature, but the temperature is measured at this block using a separate temperature sensor. This secondary measurement is used to compensate for temperature variation at the junction block. The thermocouple junction is often exposed to extreme environments, while the reference junction is often mounted near the instrument's location. Semiconductor thermometer devices are often used in modern thermocouple instruments.

In both cases the value is calculated, then the function is searched for a matching value. The argument where this match occurs is the value of :

- .

Practical concerns

Thermocouples ideally should be very simple measurement devices, with each type being characterized by a precise curve, independent of any other details. In reality, thermocouples are affected by issues such as alloy manufacturing uncertainties, aging effects, and circuit design mistakes/misunderstandings.

Circuit construction

A common error in thermocouple construction is related to cold junction compensation. If an error is made on the estimation of , an error will appear in the temperature measurement. For the simplest measurements, thermocouple wires are connected to copper far away from the hot or cold point whose temperature is measured; this reference junction is then assumed to be at room temperature, but that temperature can vary. Because of the nonlinearity in the thermocouple voltage curve, the errors in and are generally unequal values. Some thermocouples, such as Type B, have a relatively flat voltage curve near room temperature, meaning that a large uncertainty in a room-temperature translates to only a small error in .

Junctions should be made in a reliable manner, but there are many possible approaches to accomplish this. For low temperatures, junctions can be brazed or soldered; however, it may be difficult to find a suitable flux and this may not be suitable at the sensing junction due to the solder's low melting point. Reference and extension junctions are therefore usually made with screw terminal blocks. For high temperatures, the most common approach is the spot weld or crimp using a durable material.

One common myth regarding thermocouples is that junctions must be made cleanly without involving a third metal, to avoid unwanted added EMFs. This may result from another common misunderstanding that the voltage is generated at the junction. In fact, the junctions should in principle have uniform internal temperature; therefore, no voltage is generated at the junction. The voltage is generated in the thermal gradient, along the wire.

A thermocouple produces small signals, often microvolts in magnitude. Precise measurements of this signal require an amplifier with low input offset voltage and with care taken to avoid thermal EMFs from self-heating within the voltmeter itself. If the thermocouple wire has a high resistance for some reason (poor contact at junctions, or very thin wires used for fast thermal response), the measuring instrument should have high input impedance to prevent an offset in the measured voltage. A useful feature in thermocouple instrumentation will simultaneously measure resistance and detect faulty connections in the wiring or at thermocouple junctions.

Metallurgical grades

While a thermocouple wire type is often described by its chemical composition, the actual aim is to produce a pair of wires that follow a standardized curve.

Impurities affect each batch of metal differently, producing variable Seebeck coefficients. To match the standard behaviour, thermocouple wire manufacturers will deliberately mix in additional impurities to "dope" the alloy, compensating for uncontrolled variations in source material. As a result, there are standard and specialized grades of thermocouple wire, depending on the level of precision demanded in the thermocouple behaviour. Precision grades may only be available in matched pairs, where one wire is modified to compensate for deficiencies in the other wire.

A special case of thermocouple wire is known as "extension grade", designed to carry the thermoelectric circuit over a longer distance. Extension wires follow the stated curve but for various reasons they are not designed to be used in extreme environments and so they cannot be used at the sensing junction in some applications. For example, an extension wire may be in a different form, such as highly flexible with stranded construction and plastic insulation, or be part of a multi-wire cable for carrying many thermocouple circuits. With expensive noble metal thermocouples, the extension wires may even be made of a completely different, cheaper material that mimics the standard type over a reduced temperature range.

Aging

Thermocouples are often used at high temperatures and in reactive furnace atmospheres. In this case, the practical lifetime is limited by thermocouple aging. The thermoelectric coefficients of the wires in a thermocouple that is used to measure very high temperatures may change with time, and the measurement voltage accordingly drops. The simple relationship between the temperature difference of the junctions and the measurement voltage is only correct if each wire is homogeneous (uniform in composition). As thermocouples age in a process, their conductors can lose homogeneity due to chemical and metallurgical changes caused by extreme or prolonged exposure to high temperatures. If the aged section of the thermocouple circuit is exposed to a temperature gradient, the measured voltage will differ, resulting in error.

Aged thermocouples are only partly modified; for example, being unaffected in the parts outside the furnace. For this reason, aged thermocouples cannot be taken out of their installed location and recalibrated in a bath or test furnace to determine error. This also explains why error can sometimes be observed when an aged thermocouple is pulled partly out of a furnace—as the sensor is pulled back, aged sections may see exposure to increased temperature gradients from hot to cold as the aged section now passes through the cooler refractory area, contributing significant error to the measurement. Likewise, an aged thermocouple that is pushed deeper into the furnace might sometimes provide a more accurate reading if being pushed further into the furnace causes the temperature gradient to occur only in a fresh section.

Types

Certain combinations of alloys have become popular as industry standards. Selection of the combination is driven by cost, availability, convenience, melting point, chemical properties, stability, and output. Different types are best suited for different applications. They are usually selected on the basis of the temperature range and sensitivity needed. Thermocouples with low sensitivities (B, R, and S types) have correspondingly lower resolutions. Other selection criteria include the chemical inertness of the thermocouple material and whether it is magnetic or not. Standard thermocouple types are listed below with the positive electrode (assuming ) first, followed by the negative electrode.

Nickel-alloy thermocouples

Type E

Type E (chromel–constantan) has a high output (68 μV/°C), which makes it well suited to cryogenic use. Additionally, it is non-magnetic. Wide range is −270 °C to +740 °C and narrow range is −110 °C to +140 °C.

Type J

Type J (iron–constantan) has a more restricted range (−40 °C to +1200 °C) than type K but higher sensitivity of about 50 μV/°C. The Curie point of the iron (770 °C) causes a smooth change in the characteristic, which determines the upper-temperature limit. Note, the European/German Type L is a variant of the type J, with a different specification for the EMF output (reference DIN 43712:1985-01).

The positive wire is made of hard iron, while the negative wire consists of softer copper-nickel.

Type K

Type K (chromel–alumel) is the most common general-purpose thermocouple with a sensitivity of approximately 41 μV/°C. It is inexpensive, and a wide variety of probes are available in its −200 °C to +1350 °C (−330 °F to +2460 °F) range. Type K was specified at a time when metallurgy was less advanced than it is today, and consequently characteristics may vary considerably between samples. One of the constituent metals, nickel, is magnetic; a characteristic of thermocouples made with magnetic material is that they undergo a deviation in output when the material reaches its Curie point, which occurs for type K thermocouples at around 185 °C.

They operate very well in oxidizing atmospheres. If, however, a mostly reducing atmosphere (such as hydrogen with a small amount of oxygen) comes into contact with the wires, the chromium in the chromel alloy oxidizes. This reduces the emf output, and the thermocouple reads low. This phenomenon is known as green rot, due to the color of the affected alloy. Although not always distinctively green, the chromel wire will develop a mottled silvery skin and become magnetic. An easy way to check for this problem is to see whether the two wires are magnetic (normally, chromel is non-magnetic).

Hydrogen in the atmosphere is the usual cause of green rot. At high temperatures, it can diffuse through solid metals or an intact metal thermowell. Even a sheath of magnesium oxide insulating the thermocouple will not keep the hydrogen out.

Green rot does not occur in atmospheres sufficiently rich in oxygen, or oxygen-free. A sealed thermowell can be filled with inert gas, or an oxygen scavenger (e.g. a sacrificial titanium wire) can be added. Alternatively, additional oxygen can be introduced into the thermowell. Another option is using a different thermocouple type for the low-oxygen atmospheres where green rot can occur; a type N thermocouple is a suitable alternative.

Type M

Type M (82%Ni/18%Mo–99.2%Ni/0.8%Co, by weight) are used in vacuum furnaces for the same reasons as with type C (described below). Upper temperature is limited to 1400 °C. It is less commonly used than other types.

Type N

Type N (Nicrosil–Nisil) thermocouples are suitable for use between −270 °C and +1300 °C, owing to its stability and oxidation resistance. Sensitivity is about 39 μV/°C at 900 °C, slightly lower compared to type K.

Designed at the Defence Science and Technology Organisation (DSTO) of Australia, by Noel A. Burley, type-N thermocouples overcome the three principal characteristic types and causes of thermoelectric instability in the standard base-metal thermoelement materials:

- A gradual and generally cumulative drift in thermal EMF on long exposure at elevated temperatures. This is observed in all base-metal thermoelement materials and is mainly due to compositional changes caused by oxidation, carburization, or neutron irradiation that can produce transmutation in nuclear reactor environments. In the case of type-K thermocouples, manganese and aluminium atoms from the KN (negative) wire migrate to the KP (positive) wire, resulting in a down-scale drift due to chemical contamination. This effect is cumulative and irreversible.

- A short-term cyclic change in thermal EMF on heating in the temperature range about 250–650 °C, which occurs in thermocouples of types K, J, T, and E. This kind of EMF instability is associated with structural changes such as magnetic short-range order in the metallurgical composition.

- A time-independent perturbation in thermal EMF in specific temperature ranges. This is due to composition-dependent magnetic transformations that perturb the thermal EMFs in type-K thermocouples in the range about 25–225 °C, and in type J above 730 °C.

The Nicrosil and Nisil thermocouple alloys show greatly enhanced thermoelectric stability relative to the other standard base-metal thermocouple alloys because their compositions substantially reduce the thermoelectric instabilities described above. This is achieved primarily by increasing component solute concentrations (chromium and silicon) in a base of nickel above those required to cause a transition from internal to external modes of oxidation, and by selecting solutes (silicon and magnesium) that preferentially oxidize to form a diffusion-barrier, and hence oxidation-inhibiting films.

Type N thermocouples are suitable alternative to type K for low-oxygen conditions where type K is prone to green rot. They are suitable for use in vacuum, inert atmospheres, oxidizing atmospheres, or dry reducing atmospheres. They do not tolerate the presence of sulfur.

Type T

Type T (copper–constantan) thermocouples are suited for measurements in the −200 to 350 °C range. Often used as a differential measurement, since only copper wire touches the probes. Since both conductors are non-magnetic, there is no Curie point and thus no abrupt change in characteristics. Type-T thermocouples have a sensitivity of about 43 μV/°C. Note that copper has a much higher thermal conductivity than the alloys generally used in thermocouple constructions, and so it is necessary to exercise extra care with thermally anchoring type-T thermocouples. A similar composition is found in the obsolete Type U in the German specification DIN 43712:1985-01.

Platinum/rhodium-alloy thermocouples

Types B, R, and S thermocouples use platinum or a platinum/rhodium alloy for each conductor. These are among the most stable thermocouples, but have lower sensitivity than other types, approximately 10 μV/°C. Type B, R, and S thermocouples are usually used only for high-temperature measurements due to their high cost and low sensitivity. For type R and S thermocouples, HTX platinum wire can be used in place of the pure platinum leg to strengthen the thermocouple and prevent failures from grain growth that can occur in high temperature and harsh conditions.

Type B

Type B (70%Pt/30%Rh–94%Pt/6%Rh, by weight) thermocouples are suited for use at up to 1800 °C. Type-B thermocouples produce the same output at 0 °C and 42 °C, limiting their use below about 50 °C. The emf function has a minimum around 21 °C (for 21.020262 °C emf=-2.584972 μV), meaning that cold-junction compensation is easily performed, since the compensation voltage is essentially a constant for a reference at typical room temperatures.

Type R

Type R (87%Pt/13%Rh–Pt, by weight) thermocouples are used 0 to 1600 °C. Type R Thermocouples are quite stable and capable of long operating life when used in clean, favorable conditions. When used above 1100 °C ( 2000 °F), these thermocouples must be protected from exposure to metallic and non-metallic vapors. Type R is not suitable for direct insertion into metallic protecting tubes. Long term high temperature exposure causes grain growth which can lead to mechanical failure and a negative calibration drift caused by Rhodium diffusion to pure platinum leg as well as from Rhodium volatilization. This type has the same uses as type S, but is not interchangeable with it.

Type S

Type S (90%Pt/10%Rh–Pt, by weight) thermocouples, similar to type R, are used up to 1600 °C. Before the introduction of the International Temperature Scale of 1990 (ITS-90), precision type-S thermocouples were used as the practical standard thermometers for the range of 630 °C to 1064 °C, based on an interpolation between the freezing points of antimony, silver, and gold. Starting with ITS-90, platinum resistance thermometers have taken over this range as standard thermometers.

Tungsten/rhenium-alloy thermocouples

These thermocouples are well-suited for measuring extremely high temperatures. Typical uses are hydrogen and inert atmospheres, as well as vacuum furnaces. They are not used in oxidizing environments at high temperatures because of embrittlement. A typical range is 0 to 2315 °C, which can be extended to 2760 °C in inert atmosphere and to 3000 °C for brief measurements.

Pure tungsten at high temperatures undergoes recrystallization and becomes brittle. Therefore, types C and D are preferred over type G in some applications.

In presence of water vapor at high temperature, tungsten reacts to form tungsten(VI) oxide, which volatilizes away, and hydrogen. Hydrogen then reacts with tungsten oxide, after which water is formed again. Such a "water cycle" can lead to erosion of the thermocouple and eventual failure. In high temperature vacuum applications, it is therefore desirable to avoid the presence of traces of water.

An alternative to tungsten/rhenium is tungsten/molybdenum, but the voltage–temperature response is weaker and has minimum at around 1000 K.

The thermocouple temperature is limited also by other materials used. For example beryllium oxide, a popular material for high temperature applications, tends to gain conductivity with temperature; a particular configuration of sensor had the insulation resistance dropping from a megaohm at 1000 K to 200 ohms at 2200 K. At high temperatures, the materials undergo chemical reaction. At 2700 K beryllium oxide slightly reacts with tungsten, tungsten-rhenium alloy, and tantalum; at 2600 K molybdenum reacts with BeO, tungsten does not react. BeO begins melting at about 2820 K, magnesium oxide at about 3020 K.

Type C

(95%W/5%Re–74%W/26%Re, by weight) maximum temperature will be measured by type-c thermocouple is 2329 °C.

Type D

(97%W/3%Re–75%W/25%Re, by weight)

Type G

(W–74%W/26%Re, by weight)

Others

Chromel–gold/iron-alloy thermocouples

In these thermocouples (chromel–gold/iron alloy), the negative wire is gold with a small fraction (0.03–0.15 atom percent) of iron. The impure gold wire gives the thermocouple a high sensitivity at low temperatures (compared to other thermocouples at that temperature), whereas the chromel wire maintains the sensitivity near room temperature. It can be used for cryogenic applications (1.2–300 K and even up to 600 K). Both the sensitivity and the temperature range depend on the iron concentration. The sensitivity is typically around 15 μV/K at low temperatures, and the lowest usable temperature varies between 1.2 and 4.2 K.

Type P (noble-metal alloy) or "Platinel II"

Type P (55%Pd/31%Pt/14%Au–65%Au/35%Pd, by weight) thermocouples give a thermoelectric voltage that mimics the type K over the range 500 °C to 1400 °C, however they are constructed purely of noble metals and so shows enhanced corrosion resistance. This combination is also known as Platinel II.

Platinum/molybdenum-alloy thermocouples

Thermocouples of platinum/molybdenum-alloy (95%Pt/5%Mo–99.9%Pt/0.1%Mo, by weight) are sometimes used in nuclear reactors, since they show a low drift from nuclear transmutation induced by neutron irradiation, compared to the platinum/rhodium-alloy types.

Iridium/rhodium alloy thermocouples

The use of two wires of iridium/rhodium alloys can provide a thermocouple that can be used up to about 2000 °C in inert atmospheres.

Pure noble-metal thermocouples Au–Pt, Pt–Pd

Thermocouples made from two different, high-purity noble metals can show high accuracy even when uncalibrated, as well as low levels of drift. Two combinations in use are gold–platinum and platinum–palladium. Their main limitations are the low melting points of the metals involved (1064 °C for gold and 1555 °C for palladium). These thermocouples tend to be more accurate than type S, and due to their economy and simplicity are even regarded as competitive alternatives to the platinum resistance thermometers that are normally used as standard thermometers.

HTIR-TC (High Temperature Irradiation Resistant) thermocouples

HTIR-TC offers a breakthrough in measuring high-temperature processes. Its characteristics are: durable and reliable at high temperatures, up to at least 1700 °C; resistant to irradiation; moderately priced; available in a variety of configurations - adaptable to each application; easily installed. Originally developed for use in nuclear test reactors, HTIR-TC may enhance the safety of operations in future reactors. This thermocouple was developed by researchers at the Idaho National Laboratory (INL).

Comparison of types

The table below describes properties of several different thermocouple types. Within the tolerance columns, T represents the temperature of the hot junction, in degrees Celsius. For example, a thermocouple with a tolerance of ±0.0025×T would have a tolerance of ±2.5 °C at 1000 °C. Each cell in the Color Code columns depicts the end of a thermocouple cable, showing the jacket color and the color of the individual leads. The background color represents the color of the connector body.

Thermocouple insulation

Wires insulation

The wires that make up the thermocouple must be insulated from each other everywhere, except at the sensing junction. Any additional electrical contact between the wires, or contact of a wire to other conductive objects, can modify the voltage and give a false reading of temperature.

Plastics are suitable insulators for low temperatures parts of a thermocouple, whereas ceramic insulation can be used up to around 1000 °C. Other concerns (abrasion and chemical resistance) also affect the suitability of materials.

When wire insulation disintegrates, it can result in an unintended electrical contact at a different location from the desired sensing point. If such a damaged thermocouple is used in the closed loop control of a thermostat or other temperature controller, this can lead to a runaway overheating event and possibly severe damage, as the false temperature reading will typically be lower than the sensing junction temperature. Failed insulation will also typically outgas, which can lead to process contamination. For parts of thermocouples used at very high temperatures or in contamination-sensitive applications, the only suitable insulation may be vacuum or inert gas; the mechanical rigidity of the thermocouple wires is used to keep them separated.

Table of insulation materials

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Type of Insulation | Max. continuous temperature | Max. single reading | Abrasion resistance | Moisture resistance | Chemical resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mica–glass tape | 649 °C/1200 °F | 705 °C/1300 °F | Good | Fair | Good |

| TFE tape, TFE–glass tape | 649 °C/1200 °F | 705 °C/1300 °F | Good | Fair | Good |

| Vitreous-silica braid | 871 °C/1600 °F | 1093 °C/2000 °F | Fair | Poor | Poor |

| Double glass braid | 482 °C/900 °F | 538 °C/1000 °F | Good | Good | Good |

| Enamel–glass braid | 482 °C /900 °F | 538 °C/1000 °F | Fair | Good | Good |

| Double glass wrap | 482 °C/900 °F | 427 °C/800 °F | Fair | Good | Good |

| Non-impregnated glass braid | 482 °C/900 °F | 427 °C/800 °F | Poor | Poor | Fair |

| Skive TFE tape, TFE–glass braid | 482 °C/900 °F | 538 °C/1000 °F | Good | Excellent | Excellent |

| Double cotton braid | 88 °C/190 °F | 120 °C/248 °F | Good | Good | Poor |

| "S" glass with binder | 704 °C/1300 °F | 871 °C/1600 °F | Fair | Fair | Good |

| Nextel ceramic fiber | 1204 °C/2200 °F | 1427 °C/2600 °F | Fair | Fair | Fair |

| Polyvinyl/nylon | 105 °C/221 °F | 120 °C/248 °F | Excellent | Excellent | Good |

| Polyvinyl | 105 °C/221 °F | 105 °C/221 °F | Good | Excellent | Good |

| Nylon | 150 °C/302 °F | 130 °C/266 °F | Excellent | Good | Good |

| PVC | 105 °C/221 °F | 105 °C/221 °F | Good | Excellent | Good |

| FEP | 204 °C/400 °F | 260 °C/500 °F | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent |

| Wrapped and fused TFE | 260 °C/500 °F | 316 °C/600 °F | Good | Excellent | Excellent |

| Kapton | 316 °C/600 °F | 427 °C/800 °F | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent |

| Tefzel | 150 °C/302 °F | 200 °C/392 °F | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent |

| PFA | 260 °C/500 °F | 290 °C/550 °F | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent |

| T300* | 300 °C | – | Good | Excellent | Excellent |

Temperature ratings for insulations may vary based on what the overall thermocouple construction cable consists of.

Note: T300 is a new high-temperature material that was recently approved by UL for 300 °C operating temperatures.

Applications

Thermocouples are suitable for measuring over a large temperature range, from −270 up to 3000 °C (for a short time, in inert atmosphere). Applications include temperature measurement for kilns, gas turbine exhaust, diesel engines, other industrial processes and fog machines. They are less suitable for applications where smaller temperature differences need to be measured with high accuracy, for example the range 0–100 °C with 0.1 °C accuracy. For such applications thermistors, silicon bandgap temperature sensors and resistance thermometers are more suitable.

Steel industry

Type B, S, R and K thermocouples are used extensively in the steel and iron industries to monitor temperatures and chemistry throughout the steel making process. Disposable, immersible, type S thermocouples are regularly used in the electric arc furnace process to accurately measure the temperature of steel before tapping. The cooling curve of a small steel sample can be analyzed and used to estimate the carbon content of molten steel.

Gas appliance safety

Many gas-fed heating appliances such as ovens and water heaters make use of a pilot flame to ignite the main gas burner when required. If the pilot flame goes out, unburned gas may be released, which is an explosion risk and a health hazard. To prevent this, some appliances use a thermocouple in a fail-safe circuit to sense when the pilot light is burning. The tip of the thermocouple is placed in the pilot flame, generating a voltage which operates the supply valve which feeds gas to the pilot. So long as the pilot flame remains lit, the thermocouple remains hot, and the pilot gas valve is held open. If the pilot light goes out, the thermocouple temperature falls, causing the voltage across the thermocouple to drop and the valve to close.

Where the probe may be easily placed above the flame, a rectifying sensor may often be used instead. With part ceramic construction, they may also be known as flame rods, flame sensors or flame detection electrodes.

Some combined main burner and pilot gas valves (mainly by Honeywell) reduce the power demand to within the range of a single universal thermocouple heated by a pilot (25 mV open circuit falling by half with the coil connected to a 10–12 mV, 0.2–0.25 A source, typically) by sizing the coil to be able to hold the valve open against a light spring, but only after the initial turning-on force is provided by the user pressing and holding a knob to compress the spring during lighting of the pilot. These systems are identifiable by the "press and hold for x minutes" in the pilot lighting instructions. (The holding current requirement of such a valve is much less than a bigger solenoid designed for pulling the valve in from a closed position would require.) Special test sets are made to confirm the valve let-go and holding currents, because an ordinary milliammeter cannot be used as it introduces more resistance than the gas valve coil. Apart from testing the open circuit voltage of the thermocouple, and the near short-circuit DC continuity through the thermocouple gas valve coil, the easiest non-specialist test is substitution of a known good gas valve.

Some systems, known as millivolt control systems, extend the thermocouple concept to both open and close the main gas valve as well. Not only does the voltage created by the pilot thermocouple activate the pilot gas valve, it is also routed through a thermostat to power the main gas valve as well. Here, a larger voltage is needed than in a pilot flame safety system described above, and a thermopile is used rather than a single thermocouple. Such a system requires no external source of electricity for its operation and thus can operate during a power failure, provided that all the other related system components allow for this. This excludes common forced air furnaces because external electrical power is required to operate the blower motor, but this feature is especially useful for un-powered convection heaters. A similar gas shut-off safety mechanism using a thermocouple is sometimes employed to ensure that the main burner ignites within a certain time period, shutting off the main burner gas supply valve should that not happen.

Out of concern about energy wasted by the standing pilot flame, designers of many newer appliances have switched to an electronically controlled pilot-less ignition, also called intermittent ignition. With no standing pilot flame, there is no risk of gas buildup should the flame go out, so these appliances do not need thermocouple-based pilot safety switches. As these designs lose the benefit of operation without a continuous source of electricity, standing pilots are still used in some appliances. The exception is later model instantaneous (aka "tankless") water heaters that use the flow of water to generate the current required to ignite the gas burner; these designs also use a thermocouple as a safety cut-off device in the event the gas fails to ignite, or if the flame is extinguished.

Thermopile radiation sensors

Thermopiles are used for measuring the intensity of incident radiation, typically visible or infrared light, which heats the hot junctions, while the cold junctions are on a heat sink. It is possible to measure radiative intensities of only a few μW/cm with commercially available thermopile sensors. For example, some laser power meters are based on such sensors; these are specifically known as thermopile laser sensor.

The principle of operation of a thermopile sensor is distinct from that of a bolometer, as the latter relies on a change in resistance.

Manufacturing

Thermocouples can generally be used in the testing of prototype electrical and mechanical apparatus. For example, switchgear under test for its current carrying capacity may have thermocouples installed and monitored during a heat run test, to confirm that the temperature rise at rated current does not exceed designed limits.

Power production

Main article: Thermoelectric generatorA thermocouple can produce current to drive some processes directly, without the need for extra circuitry and power sources. For example, the power from a thermocouple can activate a valve when a temperature difference arises. The electrical energy generated by a thermocouple is converted from the heat which must be supplied to the hot side to maintain the electric potential. A continuous transfer of heat is necessary because the current flowing through the thermocouple tends to cause the hot side to cool down and the cold side to heat up (the Peltier effect).

Thermocouples can be connected in series to form a thermopile, where all the hot junctions are exposed to a higher temperature and all the cold junctions to a lower temperature. The output is the sum of the voltages across the individual junctions, giving larger voltage and power output. In a radioisotope thermoelectric generator, the radioactive decay of transuranic elements as a heat source has been used to power spacecraft on missions too far from the Sun to use solar power.

Thermopiles heated by kerosene lamps were used to run batteryless radio receivers in isolated areas. There are commercially produced lanterns that use the heat from a candle to run several light-emitting diodes, and thermoelectrically powered fans to improve air circulation and heat distribution in wood stoves.

Process plants

Chemical production and petroleum refineries will usually employ computers for logging and for limit testing the many temperatures associated with a process, typically numbering in the hundreds. For such cases, a number of thermocouple leads will be brought to a common reference block (a large block of copper) containing the second thermocouple of each circuit. The temperature of the block is in turn measured by a thermistor. Simple computations are used to determine the temperature at each measured location.

Thermocouple as vacuum gauge

See also: Pressure measurement § Thermal conductivityA thermocouple can be used as a vacuum gauge over the range of approximately 0.001 to 1 torr absolute pressure. In this pressure range, the mean free path of the gas is comparable to the dimensions of the vacuum chamber, and the flow regime is neither purely viscous nor purely molecular. In this configuration, the thermocouple junction is attached to the centre of a short heating wire, which is usually energised by a constant current of about 5 mA, and the heat is removed at a rate related to the thermal conductivity of the gas.

The temperature detected at the thermocouple junction depends on the thermal conductivity of the surrounding gas, which depends on the pressure of the gas. The potential difference measured by a thermocouple is proportional to the square of pressure over the low- to medium-vacuum range. At higher (viscous flow) and lower (molecular flow) pressures, the thermal conductivity of air or any other gas is essentially independent of pressure. The thermocouple was first used as a vacuum gauge by Voege in 1906. The mathematical model for the thermocouple as a vacuum gauge is quite complicated, as explained in detail by Van Atta, but can be simplified to:

where P is the gas pressure, B is a constant that depends on the thermocouple temperature, the gas composition and the vacuum-chamber geometry, V0 is the thermocouple voltage at zero pressure (absolute), and V is the voltage indicated by the thermocouple.

The alternative is the Pirani gauge, which operates in a similar way, over approximately the same pressure range, but is only a 2-terminal device, sensing the change in resistance with temperature of a thin electrically heated wire, rather than using a thermocouple.

See also

- Heat flux sensor

- Bolometer

- Giuseppe Domenico Botto

- Thermistor

- Thermoelectric power

- List of sensors

- International Temperature Scale of 1990

- Bimetal (mechanical)

References

- "Thermocouple temperature sensors". Temperatures.com. Archived from the original on 2008-02-16. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ Ramsden, Ed (September 1, 2000). "Temperature measurement". Sensors. Archived from the original on 2010-03-22. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- "Technical Notes: Thermocouple Accuracy". IEC 584-2(1982)+A1(1989). Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- "How to Prevent Temperature Measurement Errors When Installing Thermocouple Sensors and Transmitters" (PDF). acromag.com. Acromag. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ Wang, T. P. (1990) "Thermocouple Materials" Archived 2014-08-19 at the Wayback Machine in ASM Handbook, Vol. 2. ISBN 978-0-87170-378-1

- Pyromation, Inc. "Thermocouple theory" (2009).

- Rowe, Martin (2013). "Thermocouples: Simple but misunderstood", EDN Network.

- Kerlin, T.W. & Johnson, M.P. (2012). Practical Thermocouple Thermometry (2nd Ed.). Research Triangle Park: ISA. pp. 110–112. ISBN 978-1-937560-27-0.

- Buschow, K. H. J. Encyclopedia of materials: science and technology, Elsevier, 2001 ISBN 0-08-043152-6, p. 5021, table 1.

- ^ "Standard [WITHDRAWN] DIN 43710:1985-12".

- Trento, Chin (Sep 4, 2024). "Positive or Negative? A Beginner's Guide to Thermocouple Wire Identification". Stanford Advanced Materials. Retrieved Oct 7, 2024.

- Manual on the Use of Thermocouples in Temperature Measurement (4th Ed.). ASTM. 1993. pp. 48–51. ISBN 978-0-8031-1466-1. Archived from the original on 2013-08-14. Retrieved 2012-09-04.

- "Helping thermocouples do the job... - Transcat". www.transcat.com.

- "Green Rot in Type K Thermocouples, and What to Do About It". WIKA blog. 2018-05-29. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- Burley, Noel A. Nicrosil/Nisil Type N Thermocouples Archived 2006-10-15 at the Wayback Machine. www.omega.com.

- Type N Thermocouple Versus Type K Thermocouple in A Brick Manufacturing Facility. jms-se.com.

- "Thermocouple sensor and thermocouple types - WIKA USA". www.wika.us. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- "Thermocouple Theory". Capgo. Archived from the original on 14 December 2004. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- "Supplementary Information for the ITS-90". International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Archived from the original on 2012-09-10. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ OMEGA Engineering Inc. "Tungsten-Rhenium Thermocouples Calibration Equivalents".

- ^ Pollock, Daniel D. (1991). Thermocouples: Theory and Properties. CRC Press. pp. 249–. ISBN 978-0-8493-4243-1.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Design of Thermocouple Probes for Measurement of Rocket Exhaust Plume Temperatures" (PDF).

- Other Types of Thermocouples. maniadsanat.com.

- ^ Thermoelectricity: Theory, Thermometry, Tool, Issue 852 by Daniel D. Pollock.

- 5629 Gold Platinum Thermocouple Archived 2014-01-05 at the Wayback Machine. fluke.com.

- BIPM – "Techniques for Approximating the ITS-90" Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine Chapter 9: Platinum Thermocouples.

- "CORE-Materials • High Temperature Irradiation Resistant Thermocouple (HTIR-TC)". Archived from the original on 2017-06-27. Retrieved 2019-05-29.

- "high-temperature irradiation-resistant thermocouples: Topics by Science.gov". www.science.gov. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- IEC 60584-3:2007

- Flammable Vapor Ignition Resistant Water Heaters: Service Manual (238-44943-00D) (PDF). Bradford White. pp. 11–16. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- "New Scientist". New Scientist Careers Guide: The Employer Contacts Book for Scientists. Reed Business Information: 67–. 10 January 1974. ISSN 0262-4079. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- Hablanian, M. H. (1997) High-Vacuum Technology: A Practical Guide, Second Ed., Marcel Dekker Inc., pp. 19–22, 45–47 & 438–443, ISBN 0-8247-9834-1.

- Voege, W. (1906) Physik Zeit., 7: 498.

- Van Atta, C. M. (1965) Vacuum Science and Engineering, McGraw-Hill Book Co. pp. 78–90.

External links

- Thermocouple Operating Principle – University Of Cambridge

- Thermocouple Drift – University Of Cambridge

- Two Ways to Measure Temperature Using Thermocouples

Thermocouple data tables:

- Text tables: NIST ITS-90 Thermocouple Database (B, E, J, K, N, R, S, T)

- PDF tables: J K T E N R S B

- Python package thermocouples_reference containing characteristic curves of many thermocouple types.

- R package Temperature Measurement with Thermocouples, RTD and IC Sensors.

- Data table: Thermocouple wire sizes

can be used to calculate temperature

can be used to calculate temperature  , provided that temperature

, provided that temperature  is known.

is known. ) is directly proportional to the gradient in temperature (

) is directly proportional to the gradient in temperature ( ):

):

is a temperature-dependent

is a temperature-dependent  to

to

and

and  are the

are the  , which needs only to be consulted at two arguments:

, which needs only to be consulted at two arguments:

.

.

is calculated, then the function

is calculated, then the function  .

. , an error will appear in the temperature measurement. For the simplest measurements, thermocouple wires are connected to copper far away from the hot or cold point whose temperature is measured; this reference junction is then assumed to be at room temperature, but that temperature can vary. Because of the nonlinearity in the thermocouple voltage curve, the errors in

, an error will appear in the temperature measurement. For the simplest measurements, thermocouple wires are connected to copper far away from the hot or cold point whose temperature is measured; this reference junction is then assumed to be at room temperature, but that temperature can vary. Because of the nonlinearity in the thermocouple voltage curve, the errors in  are generally unequal values. Some thermocouples, such as Type B, have a relatively flat voltage curve near room temperature, meaning that a large uncertainty in a room-temperature

are generally unequal values. Some thermocouples, such as Type B, have a relatively flat voltage curve near room temperature, meaning that a large uncertainty in a room-temperature  ) first, followed by the negative electrode.

) first, followed by the negative electrode.