This is an old revision of this page, as edited by SmackBot (talk | contribs) at 21:34, 6 February 2009 (Date maintenance tags and general fixes). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:34, 6 February 2009 by SmackBot (talk | contribs) (Date maintenance tags and general fixes)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Country (disambiguation).

Country (/ˈkən-trē/ or /ˈkʌntriː/) may refer to the territory of a state, or sometimes to a smaller, or former, political division of a geographical region. In another meaning of the word, the country (or countryside) is also a term used to refer to rural areas. Usually, but not always, a country coincides with a sovereign territory and is associated with a state, nation and government.

In common usage, the term country is used in the sense of both nations and states, with definitions varying. In some cases it is used to refer both to states and to other political entities, while in some occasions it refers only to states It is not uncommon for general information or statistical publications to adopt the wider definition for purposes such as illustration and comparison.

Some entities which constitute cohesive geographical entities, and may be former states, but which are not presently sovereign states (such as England, Scotland and Wales), are commonly regarded and referred to as countries. Another example is the Basque Country, which has a number of possible meanings, but none coinciding with the borders of a state. Here it is the distinctiveness of the Basque nation which has preserved the use of the word; other former states such as Bavaria (now part of Germany) and Piedmont (now part of Italy) would not normally be referred to as "countries" in contemporary English. The degree of autonomy of such non-state countries varies widely. Some are possessions of states, as several states have overseas dependencies (such as the British Virgin Islands, Netherlands Antilles, and American Samoa), with territory and citizenry distinct from their own. Such dependent territories are sometimes listed together with independent states on lists of countries.

Etymology and development of the word

Country has developed from the Latin contra, meaning "against", used in the sense of "that which lies against, or opposite to, the view", i.e. the landscape spread out to the view. From this came the Late Latin term contrata, which became the modern Italian contrada. The term appears in Middle English from the 13th century, already in several different senses.

In English the word has increasingly become associated with political divisions, so that one sense, associated with the indefinite article - "a country" - is now a synonym for state, in the sense of sovereign territory, for example in the phrase "country of origin". But several other senses of the word remain, including "country" as the opposite of "town", a term for rural areas in general, as in country music. This is used with a generalized definite article - "the country". Areas much smaller than a political state may be called by names such as the West Country in England, the Black Country (a heavily industrialized part of England), "Constable Country" (a part of East Anglia painted by John Constable, the "big country" (used in various contexts of the American West), "coal country" (used of parts of the US and elsewhere) and many other terms.

The equivalent terms in French and other Romance languages (pays and variants) and the Germanic languages (land and variants) have not carried the process of being identified with political sovereign states as far as the English "country", and in many European countries the words are used for sub-divisions of the national territory, as in the German Länder, as well as a less formal term for a sovereign state. France has very many "pays" that are officially recognised at some level, and are either natural regions, like the Pays de Bray, or reflect old political or economic unities, like the Pays de la Loire. At the same time the United States and Brazil are also "pays" in everyday French speech.

Although a version of "country", as cuntrée, existed in Old French, it has not survived into the modern language, whereas the modern Italian contrada is a word with its meaning varying locally, but usually meaning a ward or similar small division of a town, or a village or hamlet in the countryside.

Political History of the World and of the development of sovereign states and governments

Ancient

Main article: Ancient history

In ancient history, civilizations did not have definite boundaries as states have today, and their borders could be more accurately described as frontiers. Early dynastic Sumer, and early dynastic Egypt were the first civilizations to define their borders.

The first states of sorts were those of early dynastic Sumer and early dynastic Egypt, which arose from the Uruk period and Predynastic Egypt respectively at approximately 3000BC. Early dynastic Egypt was based around the Nile River in the north-east of Africa, the kingdom's boundaries being based around the Nile and stretching to areas where oases existed. Early dynastic Sumer was located in southern Mesopotamia with its borders extending from the Persian Gulf to parts of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.

By 2500 BCE the Indian civilization, located in the Indus Valley had formed. The civilization's boundaries extended 600KM inland from the Arabian Sea.

336 BCE saw the rise of Alexander the Great, who forged an empire from various vassal states stretching from modern Greece to the Indian subcontinent, bringing Medeterrainian nations into contact with those of central and southern Asia, much as the Persian Empire had before him. The boundaries of this empire extended hundreds of kilometers.

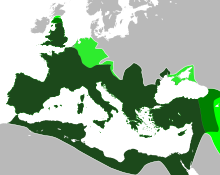

The Roman Empire (509 BCE-476 CE) was the first western civilization known to accurately define their borders, although these borders could be more accurately described as frontiers; instead of the Empire defining its borders with precision, the borders were allowed to trail off and were, in many cases, part of territory indirectly ruled by others.

Roman and Greek ideals of nationhood can be seen to have strongly influenced Western views on the subject, with the basis of many governmental systems being on authority or ideas borrowed from Rome or the Greek city-states. Notably, the European states of the Dark ages and Middle ages gained their authority from the Roman Catholic religion, and modern democracies are based in part on the example of Ancient Athens.

Middle ages

Main article: Middle ages

China entered the Sui Dynasty, this saw a change in government and an expansion in its borders as the many separate bureaucracies unified under one banner. This evolved into the the Tang Dynasty when Li Yuan took control of China in 626. By now, the Chinese borders had expanded from eastern China, up north into the Tang Empire. The Tang Empire fell apart in 907 and split into ten regional kingdoms and five dynasties with vague borders. 53 years after the separation of the Tang Empire, China entered the Song Dynasty under the rule of Chao K'uang, although the borders of this country expanded, they were never as large as those of the Tang dynasty and were constantly being redefined due to attacks from the neighboring Tartar people known is the Khitan tribes.

In Western Europe, briefly mostly united into a single state under Charlemagne around 800CE, a few countries, including England, Scotland, Iceland and Norway, had already effectively become nation states by 1,000CE, with a kingdom (Commonwealth in Iceland's case) largely co-terminus with a people mostly sharing a language and culture.

Over most of the continent, the peoples were emerging around ethnic, linguistic and geographical groups, but this was not reflected in political entities. In particular, France, Italy and Germany, though recognised by other nations as countries where the French, Italians and Germans lived, did not exist as states largely matching the countries for centuries, and struggles to form them, and define their borders, as states were a major cause of wars in Europe until the 20th century. In the course of this process, some countries, such as Poland under the Partitions and France in the High Middle Ages, almost ceased to exist as states for periods. The Low Countries, in the Middle Ages as distinct a country as France, became permanently divided, today into Belgium and the Netherlands. Spain was formed as a nation state by the dynastic union of small Christian kingdoms, augmented by the final campaigns of the Reconquista against Al-Andaluz, the vanished country of Islamic Iberia.

In 1299 CE, the Aztec empire arose in lower Mexico, this empire lasted over 500 years and at their prime, held over 5,000 square kilometers of land.

200 years after the Aztec and Toltec empires began, northern and central Asia saw the rise of the Mongol empire. By the late 13th century, the Empire extended across Europe and Asia, briefly creating a state capable of ruling and administrating immensely diverse cultures. In 1299, the Ottomans entered the scene, these Turkish nomads took control of Asia Minor along with much of central Europe over a period of 370 years, providing what may be considered a long-lasting Islamic counterweight to Christendom.

Exploiting opportunities left open by the Mongolian advance and recession as well as the spread of Islam. Russia took control of their homeland around 1613, after many years being dominated by the Tartars. After gaining independence, The Russian princes began to expand their borders under the leadership of many tsars. Notably, Catherine the Great seized the vast western part of Ukraine from the Poles, expanding Russia's size massively. Throughout the following centuries, Russia expanded rapidly, coming close to its modern size.

Early modern era

Main article: Early modern era

In 1700, Charles II of Spain died, naming Phillip of Anjou, Louis XIV's grandson, his heir. Charles' decision was not well met by the British, who believed that Louis would use the opportunity to ally France and Spain and attempt to take over Europe. Britain formed the Grand Alliance with Holland, Austria and a majority of the German states and declared war against Spain in 1702. The War of the Spanish Succession lasted 11 years, and ended when the Treaty of Utrecht has signed in 1714.

Less then 50 years later, in 1740, war broke out again, sparked by the invasion of Silesia, part of Austria, by King Frederick II of Prussia. Britain, the Netherlands and Hungary supported Maria Theresa. Over the next eight years, these and other states participated in the War of the Austrian Succession, until a treaty was signed, allowing Prussia to keep Silesia. The Seven Years' War began when Theresa dissolved her alliance with Britain and allied with France and Russia. In 1763, Britain won the war, claiming Canada and land east of the Mississippi. Prussia also kept Silesia.

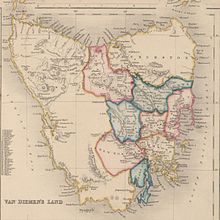

Interest in the geography of the Southern Hemisphere began to increase in the 18th century, in 1642, Dutch navigator Abel Tasman was commissioned to explore Southern Hemisphere, during his voyages, Tasman discovered the island of Van Diemen's Land, which was later named Tasmania, the Australian coast and New Zealand in 1644. Captain James Cook was commissioned in 1768 to observe a solar eclipse in Tahiti and sailed into Stingray Harbor on Australia's east coast in 1770, claiming the land for the British Crown. Settlements in Australia began in 1788 when Britain began to utilize the country for the deportation of convicts, with the first free settles arriving in 1793. Likewise New Zealand became a home for hunters seeking whales and seals in the 1790s with later non-commercial settlements by the Scottish in the 1820s and 30s.

In Northern America, revolution was beginning when in 1770, British troops opened fire on a mob pelting them with stones, an event later known as the Boston Massacre. British authorities were unable to determine if this event was a local one, or signs of something bigger until, in 1775, Rebel forces confirmed their intentions by attacker British troops on Bunker Hill. Shortly after, Massachusetts Second Continental Congress representative John Adams and his cousin Samuel Adams were part of a group calling for an American Declaration of Independence. The Congress ended without committing to a Declaration, but prepared for conflict by naming George Washington as the Continental Army Commander. War broke out and lasted until 1783, when Britain signed the Treaty of Paris and recognized America's independence. In 1788, the states ratified the United States Constitution, going from a confederation to a union and in 1789, elected George Washington as the first President of the United States.

By the late 1780s, France was falling into debt, with higher taxes introduced and famines ensuring. As a measure of last resort, King Louis XVI called together the Estates-General in 1788 and reluctantly agreed to turn the Third Estate (which made up all of the non-noble and non-clergy French) it into a National Assembly. This assembly grew very popular in the public eye and on July 14, 1789, following evidence that the King planned to disband the Assembly, an angry mob stormed the Bastille, taking gun powder and lead shot. Stories of the success of this raid spread all over the country, this sparked multiple uprisings in which the lower-classes robbed granaries and manor houses. In August of the same year, members of the National Assembly wrote the revolutionary document Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen which proclaimed freedom of speech, press and religion. By 1792, other European states were attempting to quell the revolution. In the same year Austrian and German armies attempted to march on Paris, but the French repelled them. Building on fears of Europeon invasion, a radical group known as the Jacobins abolished the monarchy and executed King Louis for treason in 1793. In response to this radical uprising, Britain Span and the Netherlands join in the fight with the Jacobins until the Reign of Terror was brought to an end in 1794 with the execution of a Jacobin leader, Maximilien Robespierre. A new constitution was adopted in 1795 with some calm returning, although the country was still at war. In 1799, a group of politicians lead by Napoleon Bonaparte unseated leaders of the Directory.

See also

References

- "country". Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2008 ed.). Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- "Acts Interpretation Act 1901 - Sect 22: Meaning of certain words". Australasian Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- "The Kwet Koe v Minister for Immigration & Ethnic Affairs & Ors [1997] FCA 912 (8 September 1997)". Australasian Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- "U.S. Department of State Foreign Affairs Manual Volume 2—General" (PDF). United States Department of State. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- Rosenberg, Matt. "Geography: Country, State, and Nation". Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- "The World Factbook - Rank Order - Exports". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- "Index of Economic Freedom". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- "Index of Economic Freedom - Top 10 Countries". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- "Asia-Pacific (Region A) Economic Information" (PDF). The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- "Subjective well-being in 97 countries" (PDF). University of Michigan. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- John Simpson, Edmund Weiner (ed.). "country". Oxford English Dictionary (1971 compact ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198611862.

- OED, Country

- ^ John Simpson, Edmund Weiner (ed.). Oxford English Dictionary (1971 compact ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198611862.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Daniel, Glyn (2003) . The First Civilizations: The Archaeology of their Origins (HTML). New York: Phoenix Press. xiii. ISBN 1842125001.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - Daniel, Glyn (2003) . The First Civilizations: The Archaeology of their Origins (HTML). New York: Phoenix Press. pp. 9–11. ISBN 1842125001.

- Daniels, Patrica S (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History (HTML). National Geographic Society. p. 56. ISBN 0792250923.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - de Blois, Lukas (1997). An Introduction to the Ancient World. New York, US: Routledge. p. 131. ISBN 0415127734.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "A World Defined By Boundaries". Intertext. Syracuse University. 2001. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- Kaplan, David H (2002). "The 'Civilisational' Roots of European National Boundaries". Boundaries and Place: European Borderlands in Geographical Context (HTML). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 19. ISBN 0847698831.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Benn, Charles D. (2004). China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty (HTML). Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0195176650. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- Daniels, Patrica S (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History (HTML). National Geographic Society. pp. 118–21. ISBN 0792250923.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Benn, Charles D. (2004). China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty (HTML). Oxford University Press. pp. ix. ISBN 0195176650. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- Herrmann, Albert (1970). Historical and Commercial Atlas of China (HTML). Ch'eng-wen Publishing House. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- Hucker, Charles O. (1995). China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture (HTML). Stanford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0804723532. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ^ Daniels, Patrica S (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History (HTML). National Geographic Society. pp. 134–5. ISBN 0792250923.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Tsouras, Peter (2005). Montezuma: Warlord of the Aztecs (HTML). Brassey's. pp. xv. ISBN 1574888226.

- Berdan, Frances F. (1996). Aztec Imperial Strategies. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 0884022110.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Barlow, R.H. (1949). Extent of the Empire of the Culhua Mexica. Berkeley and Los Angeles Univ. of California.

- Køppen, Adolph Ludvig (1854). The World in the Middle Ages: An Historical Geography, with Accounts of the Origin and Development, the Institutions and Literature, the Manners and Customs of Three Nations in Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa, from the Close of the Fourth to the Middle of the Fifteenth Century. D. Appleton and company. p. 210. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Jacob, Samuel (1854). History of the Ottoman Empire: Including a Survey of the Greek Empire and the Crusades. R. Griffin. p. 456. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- Thomson, Gladys Scott (20008). Catherine the Great and the Expansion of Russia. Read Books. ISBN 1443728950. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Frey, Marsha (1995). The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0313278849. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Dupuy, Richard Ernes (1970). The Encyclopedia of Military History: From 3500 B.C. to the Present. Harper & Row. p. 630. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Rosner, Lisa (2000). A Short History of Europe, 1600-1815: Search for a Reasonable World (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 292. ISBN 0765603284. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Marston, Daniel (2001). The Seven Years' War (illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1841761915. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- Daniels, Patrica S (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History (HTML). National Geographic Society. p. 214. ISBN 0792250923.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Porter, Malcolm (2007). Australia and the Pacific (illustrated and revised 2007 ed.). Cherrytree Books. p. 20. ISBN 1842344609. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Kitson, Arthur (2004). The Life of Captain James Cook. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 84–5. ISBN 1419169475. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- King, Jonathan (1984). The First Settlement: The Convict Village that Founded Australia 1788-90. Macmillan. ISBN 0333380800.

- Currer-Briggs, Noel (1982). Worldwide Family History (illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 180. ISBN 0710009348.

- Daniels, Patrica S (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History (HTML). National Geographic Society. p. 216. ISBN 0792250923.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lancaster, Bruce (2001). illustrated (ed.). The American Revolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 74. ISBN 0618127399. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Daniels, Patrica S (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History (HTML). National Geographic Society. p. 218-21. ISBN 0792250923.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lancaster, Bruce (2001). illustrated (ed.). The American Revolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 96–9. ISBN 0618127399. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Jedson, Lee (2006). The Treaty of Paris, 1783: A Primary Source Examination of the Treaty That Recognized American Independence (illustrated ed.). The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 37. ISBN 1404204415. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- Bloom, Sol (2001). The Story of the Constitution (2nd illustrated ed.). Christian Liberty Press. p. 84. ISBN 1930367562. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Daniels, Patrica S (2003). Toni Eugene (ed.). Almanac of World History (HTML). National Geographic Society. p. 222-25. ISBN 0792250923.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ S. Viault, Birdsall (1990). "The French Revolution". Schaum's Outline of Modern European History (revised ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 180–91. ISBN 0070674531. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

External links

- The CIA World Factbook

- Country Portals from the United States Department of State, including Background Notes

- Country Profiles from BBC News

- Country Studies from the United States Library of Congress

- Foreign Information by Country and Country & Territory Guides from GovPubs at UCB Libraries

- PopulationData.net

- United Nations statistics division

- Average Latitude & Longitude of Countries